Abstract

When exposed to their congregations’ negative views of homosexuality, Christian men who have sex with men frequently struggle to reconcile their religious and sexual identities, possibly contributing to negative emotional states and behaviors associated with HIV/STI infection. To examine the influence of religiousity on internalized homonegativity and outness among Christian men who have sex with men, we used survey data from 1,165 men who answered questions about their religious beliefs and sexual behavior. We stratified participants based on religious affiliation groupings: Catholic, Mainline Protestant, and Evangelical Protestant. After using confirmatory factor analysis to verify that the selected measures of religiosity were equivalent between groups, we used structural equation modeling to examine the relationship between religiosity, internalized homonegativity, and outness. Among Catholics and Mainline Protestants, religiosity was not associated with internalized homonegativy or outness. However, among Evangelical Protestants—a group more likely to ascribe to religious fundamentalism—increased religiosity was associated with increased internalized homonegativity, which contributed to decreased outness. Our findings suggest that mental health providers and sexuality educators should be more concerned about the influence of religiosity on internalized homonegativity and outness when clients have a history of affiliation with Evangelical Protestant faiths more so than Catholic or Mainline Protestant faiths.

Keywords: religion, male homosexuality, sexual orientation, psychosexual behavior, homophobia

Introduction

It has been suggested that the religious and the sexual should not be viewed in opposition to each other; rather, Christian individuals should seek to understand what their faith says about living as sexual beings while simultaneously seeking to understand how sexual experiences can inform faith (Nelson, 1978). However, for many Christian men who have sex with men (MSM), religious and sexual identity integration is illusive (Dahl & Galliher, 2009; Kubicek et al., 2009; Ream & Savin-Williams, 2005), which can have implications for both mental and behavioral health. The aim of this study is to examine the association between religiosity and selected mental health outcomes that have been identified as potential risk factors for HIV/STI infection.

A discussion of the influence of religion on the health of MSM cannot occur without first acknowledging that for many Christians, homosexuality is incompatible with their belief system. Over time, Christian views towards homosexuality have become more accepting (Peterson & Donnenwerth, 1998). Still, several studies have found religiosity to be the strongest predictor of Christians’ negative attitudes toward gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons (Bauermeister, Morales, Seda, & Gonzalez-Rivera, 2007; Herek, 2002; Wilkinson & Roys, 2005). The extent to which these negative attitudes exist depends on religious fundamentalism (Herek, 1994; Higgins, 2002, 2004, 2006), and are manifested more in certain religious affiliation groups. Of the 78.4% of U.S. adults who identify as Christian, 23.9% can be classified as Catholic and 51.3% as Protestant (18.1% as Mainline Protestants, 26.3% as Evangelical Protestants, and 6.9% as historically Black churches); the remainder of Christians can be classified as Mormon (1.7%), Jehovah’s Witness (0.7%), Orthodox (0.6%), or another Christian faith tradition (0.3%) (Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2008). The Pew Forum found that when Christians are treated as one group, 50% say homosexuality is a way of life that should be accepted and 40% say it should be discouraged. However, the response pattern is more varied when stratified by religious affiliation. While the majority of Catholics and Mainline Protestants find homosexuality acceptable, the majority of Evangelical Protestants do not. Specifically, 58% of Catholics say homosexuality is acceptable and 30% say it should be discouraged, 56% of Mainline Protestants say it is acceptable and 34% say it should be discouraged, and 26% of Evangelical Protestants say it is acceptable and 64% say it should be discouraged. Other studies of Evangelical Protestants support Pew’s results, finding religious fundamentalism to be the largest predictor of negative attitudes towards homosexual persons (Finlay & Walther, 2003; Hinrichs & Rosenberg, 2002; Rosik, Griffith, & Cruz, 2007; Rowatt et al., 2006).

Exposed to their congregations’ views of homosexuality, Christian MSM frequently struggle to reconcile their religious and sexual identities, possibly contributing to negative emotional states and behaviors associated with HIV/STI infection. MSM affiliated with a religious organization not accepting of homosexuality frequently experience higher levels of internalized homonegativity (Harris, Cook, & Kashubeck-West, 2008; Higgins, 2002; Ream & Savin-Williams, 2005; Roseborough, 2006; Ross, Rosser, & Neumaier, 2008; Rosser, 1992; Szymanski, Kashubeck-West, & Meyer, 2008), defined as the “internalization of societal antihomosexual attitudes” that are integrated into self-perceptions (Meyer & Dean, 1998, p. 163). Higher levels of internalized homonegativity have been associated with drug use and unsafe sexual activity, making it a potential target of HIV prevention (Kubicek, McDavitt, Carpineto, Weiss, Iverson, & Kipke, 2009; Ross, Rosser, Bauer, Bockting, Robinson, Rugg, et al., 2001; Rostosky, Danner, & Riggle, 2007). Higher levels of internalized homonegativity also have been associated with decreased outness (Rosser, Bockting, Ross, Miner, & Coleman, 2008), which is defined as “the process of openly acknowledging one’s same-sex attractions” (Rhoads, 1994, p. 7). MSM who are less out because they have high levels of internalized homonegativity are more likely to engage in sexual risk Ross, et al., 2008; Ross, et al., 2001). While a meta-analysis of the influence of internalized homonegativity on risk suggested that the strength of the association between the two decreases as one ages (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2009), the intervening period of time is of concern to mental health providers, sexuality educators, and researchers attempting to improve the emotional and sexual health of MSM. The literature suggests that exposure to religious teachings that condemn homosexuality could contribute to increased internalized homonegativity and decreased outness. The literature also suggests that the influence of religiosity on internalized homonegativity should also influence outness. The purpose of this study was to integrate literatures on religious affiliation (Catholic, Mainline Protestant, and Evangelical Protestant), religiosity, internalized homonegativity, and outness among MSM. We hypothesized that MSM affiliated with Evangelical Protestant faiths would experience higher levels of internalized homonegativity and be less out to family and friends than Catholic or Mainline Protestant MSM.

Methods

Study Design

Internet-using MSM (N=2,716) completed an online survey about their sexual behavior with partners met in online or offline environments and several potential determinants of sexual behavior. Participants were recruited during three months in 2005 through banner advertisements placed on two websites frequented by US MSM. Eligibility criteria included being male, 18 years of age or older, a resident of the US, and acknowledging having had sex with another man at least once during one’s lifetime. Men of ethnic/racial minority background were deliberately over-sampled to provide approximately equivalent groups of Asian, Latino, Black, and White men. For this analysis, we were only interested in a subsample of Christian MSM (N=1,165).

Study procedures are described in greater detail elsewhere (Rosser, Gurak, Horvath, Oakes, Konstan, & Danilenko, 2009; Rosser, Oakes, Horvath, Konstan, Danilenko, & Peterson, 2009). Briefly, by clicking on a study banner advertisement, prospective participants were directed to the study website. After completing a screening and consent process, participants answered 170 survey questions. A refuse to answer option was provided for each question. The mean survey completion time was 45 minutes. Participants were initially compensated $10, which in the third month was raised to $20 in order to speed recruitment. This study was conducted under the oversight of the institutional review board of the researchers’ home institution.

Measures

Current religious affiliation

One question asked participants to identify their current primary religious affiliation. Christian response options included Catholic; Lutheran, Presbyterian, or other Protestant (Mainline Protestant); and Evangelical/Born again Christian (Evangelical Protestant).

Religiosity

The religiosity measure assessed current religiosity and consisted of four 5-point Likert-type items taken from the National Survey of American Life (Jackson, et al., 2004) and the National Survey of Black Americans (Jackson & Tucker, 1997): “How religious are you?” (not religious at all – very religious), “How important is religion in your life today?” (not at all important – very important), “How spiritual would you say you are?” (not at all spiritual – very spiritual), and “How often do you pray?” (never – very often) (α=0.88).

Internalized homonegativity

We measured internalized homonegativity using Smolenski, Diamond, Ross, and Rosser’s (2010) Revised Reactions to Homosexuality Scale. Responses to the seven 7-point Likert-type questions ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree and included three constructs: personal comfort with being gay (two items), public identification as gay (three items), and social comfort with gay men (two items). The Cronbach alpha for the entire scale was 0.74.

Outness

Participants were asked to respond to one 5-point Likert-type item: “I would say that I am open (out) as a gay, bisexual, or a man attracted to other men.” Responses ranged from not at all open (out) to open (out) to all or almost all people I know.

Demographic measures

Certain demographic variables were identified a priori as possible confounders that should be included as covariates in all regression models. Measures of age, education, and race/ethnicity were asked as in the 2000 US Census (US Census Bureau, 2008). Participants were also asked if they were HIV positive (yes, no, do not know).

Data Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis

We developed a training and validation split-half of the Catholic participants for calibration of the four-item measure of religiosity. After examining the model fit in each group, we tested for configural measurement invariance (equivalence of factor model structure) and metric measurement invariance (equivalence of factor loadings; Meredith, 1993; Meredith & Teresi, 2006; Wu, Li, & Zumbo, 2007) of religiosity between the two split halves to validate any modifications to the measure in the training split half. Fit was assessed using the likelihood ratio test, the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990). A value of 0.95 or above on the CFI and TLI, and a value of 0.08 or below on the RMSEA (90% confidence interval, the standard for RMSEA estimation; Loehlin, 2004) were considered indicators of good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We accounted for potential non-normality of the multivariate distribution indicated by the four items by using the robust maximum likelihood estimator (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007). The final religiosity measure was subjected to a second multi-group analysis between the three religious affiliation groups to examine comparability of measurement using the aforementioned steps and criteria.

Structural equation modeling

Within religious affiliation group, we tested a structural equation model based on an a priori hypothesis that religiosity had a direct effect on outness and an indirect effect mediated by internalized homonegativity (Figure 1). Models were adjusted for age, education, race/ethnicity, and HIV status based on the possibility that they could confound the associations of interest. The final model involved multi-group estimation of the path model with equality constraints placed on the scale measures to simultaneously compare the path coefficients between religious affiliation groups.

Figure 1.

A hypothesized model that religiosity has both a direct and an indirect relationship with outness.

Results

Demographic differences between participants when grouped according to religious affiliation were significant. A greater proportion of Latinos were Catholics, Whites were Mainline Protestants, and Blacks were Evangelical Protestants. Catholics and Mainline Protestants were of similar age and education, and they had similar levels or religiosity and internalized homonegativity. Compared to Catholics and Mainline Protestants, Evangelical Protestants were younger and less educated, and they had higher levels of religiosity and internalized homonegativity. Mainline Protestants were more likely to be out than either Catholics or Evangelical Protestants.

The religiosity construct performed similarly across groups (Table 2). Within the training group of Catholic participants, the measurement model had better fit when we allowed for covariance between the item asking about the importance of religion in a participant’s life and the item asking how religious a participant was. We replicated the measurement model within the validation group and verified it was metric invariant across religious affiliation groups.

Table 2.

Tests of measurement invariance between groups.

| Model | X2 | df | p | SCF | ΔX2 | p | CFI | TLI | AIC | SABIC | RMSEA [90% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religiosity | |||||||||||

| Raised Religious Identity Between Catholics, Protestants, and Other (n=1036): | |||||||||||

| Configural invariance | 0.999 | 3 | 0.801 | 1.280 | -- | -- | 1.000 | 1.004 | 26343.943 | 26445.300 | 0.000 [0.000, 0.038] |

| Metric invariance | 10.252 | 9 | 0.331 | 1.073 | 9.544 | 0.145 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 26341.665 | 26427.429 | 0.013 [0.000, 0.043] |

| Constraining the latent | 11.012 | 11 | 0.442 | 1.000 | 1.132 | 0.568 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 26337.679 | 26418.245 | 0.001 [0.000, 0.037] |

| Constraining the latent /> & covariance |

11.359 | 13 | 0.581 | 1.045 | 0.268 | 0.874 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 26334.531 | 26409.900 | 0.000 [0.000, 0.031] |

| Current Religious Identity Between Catholics, Protestants, and Other (n=1636):: | |||||||||||

| Configural invariance | 2.383 | 3 | 0.497 | 1.085 | -- | -- | 1.000 | 1.002 | 17288.792 | 17375.496 | 0.000 [0.000, 0.066] |

| Metric invariance | 13.372 | 9 | 0.147 | 1.063 | 10.446 | 0.107 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 17288.422 | 17361.787 | 0.030 [0.000, 0.061] |

| Constraining the latent | 17.119 | 11 | 0.104 | 1.015 | 4.690 | 0.096 | 0.997 | 0.995 | 17287.588 | 17356.507 | 0.032 [0.00. 0.060] |

| Constraining the latent /> & covariance |

39.528 | 13 | 0.000 | 1.074 | 16.024 | 0.000 | 0.986 | 0.980 | 17308.669 | 17373.142 | 0.061 [0.040, 0.083] |

| Internalized Homonegativity | |||||||||||

| Raised Religious Identity Between Catholics, Protestants, and Other (n=1030): | |||||||||||

| Configural | 53.532 | 33 | 0.013 | 1.159 | -- | -- | 0.992 | 0.984 | 67484.811 | 67671.811 | 0.028 [0.013, 0.041] |

| Metric 1st Order | 65.186 | 41 | 0.010 | 1.165 | 9.795 | 0.280 | 0.990 | 0.985 | 67482.766 | 67648.989 | 0.027 [0.014, 0.039] |

| Metric 2nd Order | 71.864 | 45 | 0.007 | 1.161 | 5.962 | 0.202 | 0.989 | 0.985 | 67482.256 | 67638.090 | 0.027 [0.015, 0.039] |

| Current Religious Identity Between Catholics, Protestants, and Other (n=1634): | |||||||||||

| Configural | 60.061 | 33 | 0.003 | 1.148 | -- | -- | 0.985 | 0.971 | 46461.827 | 46621.808 | 0.039 [0.023, 0.054] |

| Metric 1st Order | 70.383 | 41 | 0.003 | 1.159 | 8.570 | 0.380 | 0.984 | 0.975 | 46458.461 | 46600.666 | 0.036 [0.021, 0.050] |

| Metric 2nd Order | 75.378 | 45 | 0.003 | 1.156 | 4.439 | 0.350 | 0.983 | 0.976 | 46456.034 | 46589.352 | 0.035 [0.021, 0.049] |

NOTE: SCF=Scaling Correction Factor, CFI=Comparative Fit Index, TLI=Tucker-Lewis Index, AIC=Akaike Information Criterion, SABIC=Sample Size Adjusted Bayes Information Criteria, RMSEA=Root Mean Square Error of Approximation. R1: How important is religion in your life? R2: How religious are you? R3: How often do you pray? R4: How spiritual are you?

An examination of within-group correlations indicated that the influence of religiosity on internalized homonegativity and outness differed by religious affiliation. Bivariate correlations between religiosity and the variables of interest produced moderately significant correlations among Evangelical Protestants. Specifically, increased religiosity was correlated with increased internalized homonegativity and decreased outness (Table 2).

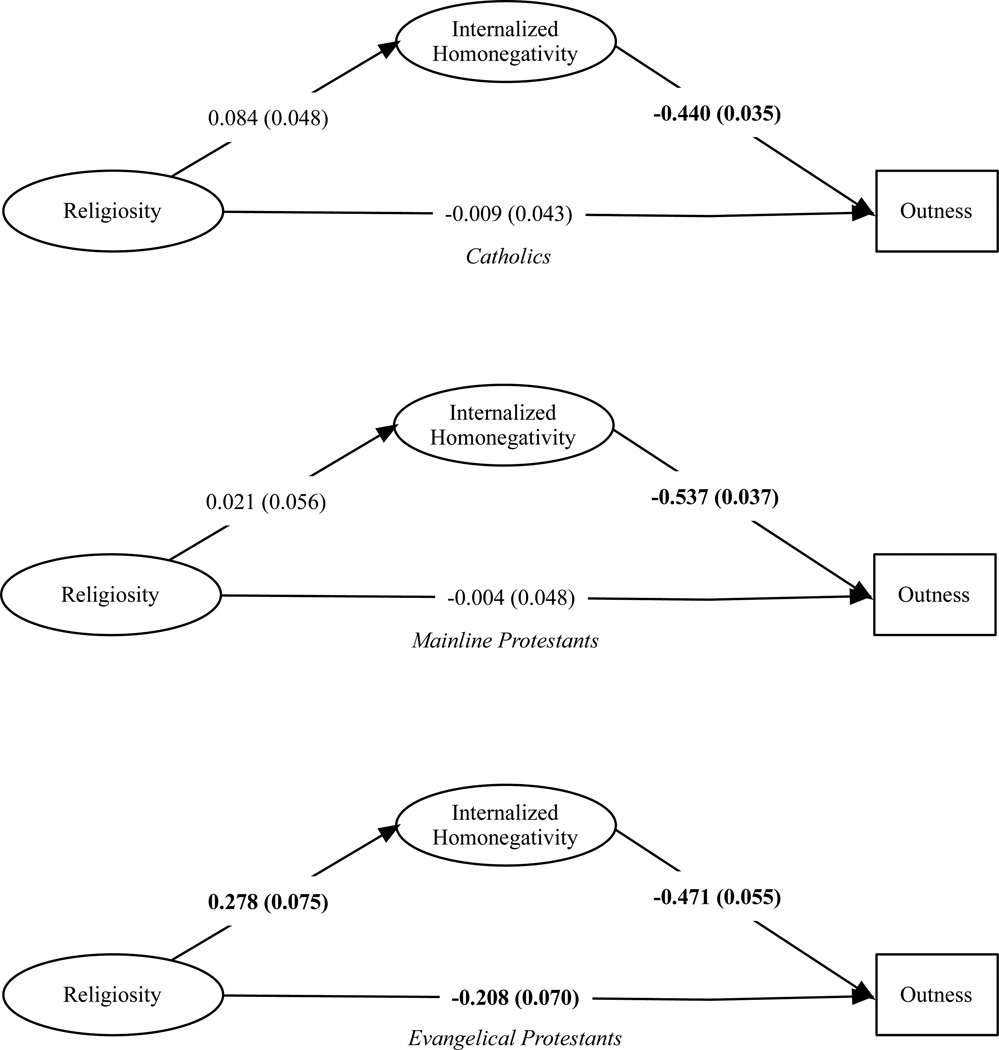

Figure 2 includes illustrations of structural equation models of the variables of interest with covariate adjustment for each religious affiliation group. Each illustration includes the standardized path coefficients with their corresponding standard errors (statistically significant values at p<0.05 are bolded). Among Catholics and Mainline Protestants, religiosity was not significantly associated with internalized homonegativity or outness. Though both groups showed evidence of decreased outness as internalized homonegativity increased, the reason for this association cannot be attributed to religiosity. However, among Evangelical Protestants, increased religiosity was associated with increased internalized homonegativity and decreased outness.

Figure 2.

Structural equation models with standardized path coefficients and standard errors. All models were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, years of education, and HIV status. Statistically significant values are bolded (p<0.05).

Discussion

While participants in all three religious affiliation groups were less likely to be out when experiencing higher internalized homonegativity, religiosity was associated with these outcomes among Evangelical Protestants only. The association among Evangelical Protestants supports previous research suggesting MSM accepting of fundamentalist religious beliefs that condemn homosexuality experience more internalized homonegativity (Higgins, 2002, 2004, 2006). Our findings suggest that mental health providers and sexuality educators should be more concerned about the influence of fundamentalist religious beliefs on internalized homonegativity and outness when their clients have a history of affiliation with Evangelical Protestant faiths more so than Catholic or Mainline Protestant faiths.

A challenge for mental health providers and sexuality educators is to develop interventions that provide religious MSM with a means to integrate their religious and sexual identities without having to abandon either. Religiosity when not punitive can be a source of emotional support and potentially encourage health-promoting behaviors (Koenig, 1998; Koenig, Mccullough, & Larson, 2001). When assisting men with the reconciliation of their religious and sexual identities, we recommend that providers and educators direct therapeutic and educational efforts towards reducing internalized homonegativity. For example, a cognitive-behavioral approach to internalized homonegativity reduction could encourage men to separate negative thoughts and feelings about same-sex attraction from the negative behaviors that result from lack of identity integration. Men could then be encouraged to challenge thoughts that lead to shame and related risk behaviors. In addition, providers and educators can connect men with religious and spiritual LGBT organizations that will model acceptance of one’s attraction to men and offer social support within a faith context.

There are at least four limitations to this study. First, because we relied on cross-sectional data to test our hypothesized model, causality cannot be assumed. To establish causality, we need prospective studies of religiosity in a sample of MSM. Second, while the literature suggests MSM affiliated with a religious organization not accepting of homosexuality have higher levels of internalized homonegativity (Harris, et al., 2008; Ream & Savin-Williams, 2005; Roseborough, 2006; Ross, et al., 2008; Szymanski, et al., 2008), we did not specifically ask participants about their religion of origin and current religious organizations’ teachings on homosexuality. Also, our measure of religious affiliation did not allow us to assess differences between evangelicals who do or do not identify as Protestant. Future researchers should collect these data when undertaking an analysis of the associations between religiosity and health outcomes in MSM. Third, since data were collected from MSM frequenting two gay-oriented websites in the US, it is likely that Christian MSM who frequent these websites are more out than Christian men who do not frequent these websites or live in countries where identifying as an out gay man is either less acceptable or incompatible with their cultural understanding of sexual identity. In addition, our findings might not generalize to countries with lower levels of religiosity than in the US, where Christian morality is more likely to present in the political and legal landscape. Lastly, because data came from an Internet-based sample, results are not generalizable to all MSM.

The results of this study contribute to a critical domain of research that could benefit mental health providers and sexuality educators. Because we know little about how religiosity affects the health of MSM, future researchers should delineate the influence of religiosity on internalized homonegativity and outness from the influence of beliefs attributed to family of origin, racial/ethnic community norms, and other sociocultural variables. With a clearer understanding of the mechanisms underlying observed observations, mental health providers and sexuality educators will be better able to develop intervention programs that increase religious MSM’s understanding and acceptance of their homosexuality.

Table 1.

Participant demographics(N=2612)

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 941 (36.1) |

| 25–29 | 663 (25.4) |

| 30–39 | 693 (26.6) |

| 40+ | 312 (12.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Asian | 486 (18.6) |

| Black | 427 (16.4) |

| Latino | 655 (25.1) |

| Other | 334 (12.8) |

| White | 710 (27.2) |

| Education | |

| < 12 years | 81 (3.1) |

| 12–15 years | 1043 (40.0) |

| 16 years | 802 (30.7) |

| 17+ years | 685 (26.2) |

| HIV-Positive | |

| Yes | 115 (4.4) |

| No | 2484 (95.6) |

| Raised Religious Affiliation | |

| Catholic/Orthodox Christian | 1032 (39.6) |

| Protestant | 1031 (39.5) |

| Atheist/Agnostic | 217 (8.3) |

| Spiritual | 8 (0.3) |

| Other | 320 (12.3) |

| Current Religious Affiliation | |

| Catholic/Orthodox Christian | 537 (20.6) |

| Protestant | 643 (24.6) |

| Atheist/Agnostic | 846 (32.4) |

| Spiritual | 130 (5.0) |

| Other | 456 (17.4) |

| Outness | |

| Not at all open (out) | 213 (8.2) |

| Open (out) to a few people they know | 472 (18.1) |

| Open (out) to about half the people they know | 284 (10.9) |

| Open (out) to most people they know | 656 (25.2) |

| Open (out) to all or almost all people they know | 981 (37.6) |

| Substance Use during sex last 3 mo. | |

| Yes | 897 (34.4) |

| No | 1714 (65.7) |

Note: Missing values were less than 1%. Persons identifying as atheist, agnostic, or spiritual were excluded from analyses.

Table 3.

Unstandardized (b) and Standardized (β) Bivariate Regression Coefficients and Univariate Distributions for Raised and Current Religiosity Groups

| IH | Outness | Subsex | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b [95% CI] | β | b [95% CI] | β | b [95% CI] | β | ||||||

| Raised Religiosity Between Catholics/Orthodox Christians, Protestants, and Other (n=1036): | |||||||||||

| Religiosity | 0.11 [0.07, 0.15] | 0.12 | −0.19 [−0.24, −0.14] | −0.15 | 0.10 [0.03, 0.18] | 0.06 | |||||

| IH | -- | -- | −0.63 [−0.68, −0.59] | −0.49 | 0.03 [−0.05, 0.11] | 0.02 | |||||

| Outness | -- | -- | −0.19 [−0.25, −0.12] | −0.14 | |||||||

| Subsex | -- | -- | |||||||||

| Current Religiosity Between Catholics/Orthodox Christians, Protestants, and Other (n=1636): | |||||||||||

| Religiosity | 0.09 [0.04, 0.15] | 0.08 | −0.12 [−0.19, −0.05] | −0.08 | 0.09 [−0.02, 0.20] | 0.05 | |||||

| IH | -- | -- | −0.66 [−0.71, −0.60] | −0.50 | 0.02 [−0.08, 0.12] | 0.01 | |||||

| Outness | -- | -- | −0.16 [−0.24, −0.09] | −0.12 | |||||||

| Subsex | -- | -- | |||||||||

| Univariate Distribution | Religiosity />M (SD) |

IH />M (SD) |

Outness />M (SD) |

Subsex />n (%) |

|||||||

| Raised Religiosity | 2.88 (1.11) | 3.22 (1.05) | 3.65 (1.36) | 827 (34.72) | |||||||

| Current Religiosity | 3.28 (0.97) | 3.32 (1.07) | 3.48 (1.40) | 536 (32.76) | |||||||

NOTE: IH=Internalized homonegativity and Subsex = substance use during sex. Bolded indicates significance at p<0.05. Because substance use during sex is dichotomous, the number and proportion endorsing the behavior and reported.

Table 4.

Structural Equation Model Trimming.

| Model | Log Likelihood | Free parameters | SCF | ΔLR X2 | Δdf | p | AIC | SABIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raised Religiosity (n=2367): | ||||||||

| Full model freely estimating the structural model | −54373.274 | 72 | 1.066 | --- | --- | --- | 108890.548 | 109077.669 |

| Full model constraining the structural model | −54379.050 | 60 | 1.092 | 12.342 | 12 | 0.419 | 108878.101 | 109034.035 |

| Removing the path between IH & Subsex | −54376.047 | 59 | 1.093 | 5.814 | 1 | 0.016 | 108870.095 | 109023.430 |

| Adjusted reduced constrained model | −53923.429 | 87 | 1.069 | 888.856 | 28 | 0.000 | 108020.857 | 108246.376 |

| Current Religiosity (n=1602): | ||||||||

| Full model freely estimating the structural model | −36446.463 | 72 | 1.056 | --- | --- | --- | 73036.925 | 73195.484 |

| Full model constraining the structural model | −36448.823 | 60 | 1.075 | 4.912 | 12 | 0.961 | 73017.646 | 73149.778 |

| Removing the path between IH & Subsex | −36448.494 | 59 | 1.075 | 0.612 | 1 | 0.434 | 73014.989 | 73144.919 |

| Removing the path between Religion & Subsex | −36448.974 | 58 | 1.078 | 0.306 | 2 | 0.858 | 73013.949 | 73141.677 |

| Removing the path between Religion & Outness | −36449.592 | 57 | 1.078 | 1.511 | 3 | 0.680 | 73013.183 | 73138.709 |

| Adjusted reduced constrained model (n=1591) | −36122.788 | 85 | 1.059 | 640.590 | 28 | 0.000 | 72415.576 | 72602.178 |

Note: IH=internalized homonegativity, Subsex=substance use during sex, and Rel=religiosity. Model adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, and HIV status.

Acknowledgments

The Men’s INTernet Sex (MINTS-II) study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health Center for Mental Health Research on AIDS, grant number 5 R01 MH063688-05. All research was carried out with the approval of the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, study number 0405S59661.

References

- Bauermeister JA, Morales M, Seda G, Gonzalez-Rivera M. Sexual prejudice among Puerto Rican young adults. Journal of Homosexuality. 2007;53(4):135–161. doi: 10.1080/00918360802103399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl AL, Galliher RV. LGBQQ Young Adult Experiences of Religious and Sexual Identity Integration. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2009;3(2):92–112. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B, Walther CS. The relation of religious affiliation, service attendance, and other factors to homophobic attitudes among university students. Review of Religious Research. 2003;44(4):370–393. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JI, Cook SW, Kashubeck-West S. Religious attitudes, internalized homophobia, and identity in gay and lesbian adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2008;12(3):205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Assessing heterosexuals' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. In: Greene B, Herek GM, editors. Lesbian and Gay Psychology: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Heterosexuals attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(4):264–274. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ. Gay Men from Heterosexual Marriages. Journal of Homosexuality. 2002;42(4):15–34. doi: 10.1300/J082v42n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ. Differences between previously married and never married 'gay' men: family background, childhood experiences and current attitudes. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;48(1):19–41. doi: 10.1300/J082v48n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ. Same-sex attraction in heterosexually partnered men: Reasons, rationales and reflections. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2006;21(2):217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs DW, Rosenberg PJ. Attitudes toward gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons among heterosexual liberal arts college students. Journal of Homosexuality. 2002;43(1):61–84. doi: 10.1300/J082v43n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, et al. The national survey of American life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Tucker MB. Three-generation National Survey of Black American Families, 1979–1981: Questionnaires. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, editor. Handbook of religion and mental health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Mccullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, McDavitt B, Carpineto J, Weiss G, Iverson EF, Kipke MD. "God Made Me Gay for a Reason": Young Men Who Have Sex with Men's Resiliency in Resolving Internalized Homophobia from Religious Sources. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2009;24(5):601–633. doi: 10.1177/0743558409341078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent Variable Models. 4 ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W. Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika. 1993;58(4):525–543. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W, Teresi JA. An essay on measurement and factorial invariance. Medical Care. 2006;44(11) Suppl. 3:S69–S77. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245438.73837.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Dean L. Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. In: Herek GM, editor. Stigma and Sexual Orientation: Understanding Prejudice Against Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998. pp. 160–186. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 5th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JB. Embodiment: an approach to sexuality and Christian theology. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Publishing House; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Moderators of the relationship between internalized homophobia and risky sexual behavior in men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson LR, Donnenwerth GV. Religion and declining support for traditional beliefs about gender roles and homosexual rights. Sociology of Religion. 1998;59(4):353–371. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. U.S. religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ream GL, Savin-Williams RC. Reconciling Christianity and positive non-heterosexual identity in adolescence, with implications for psychological well-being. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues In Education. 2005;2(3):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads RA. Coming out in college: The struggle for a queer identity. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Roseborough D. Coming out stories framed as faith narratives, or stories of spiritual growth. Pastoral Psychology. 2006;55:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rosik CH, Griffith LK, Cruz Z. Homophobia and conservative religion: toward a more nuanced understanding. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(1):10–19. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rosser BR, Neumaier ER. The relationship of internalized homonegativity to unsafe sexual behavior in HIV-seropositive men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2008;20(6):547–557. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.6.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rosser BRS, Bauer GR, Bockting WO, Robinson BE, Rugg DL, et al. Drug use, unsafe sexual behavior, and internalized homonegativity in men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5(1):97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS. Gay Catholics down under: The journeys in sexuality and spirituality of gay men in Australia and New Zealand. Westport, Conn.: Praeger; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Bockting WO, Ross MW, Miner MH, Coleman E. The relationship between homosexuality, internalized homo-negativity, and mental health in men who have sex with men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2008;55(2):185–203. doi: 10.1080/00918360802129394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Gurak L, Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, Konstan J, Danilenko GP. The challenges of ensuring participant consent in internet-based sex studies: A case study of the Men's INTernet Sex (MINTS-I and II) Studies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2009;14:602–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Oakes JM, Horvath KJ, Konstan JA, Danilenko GP, Peterson JL. HIV sexual risk behavior by men who use the internet to seek sex with men: Results of the Men's INTernet Sex Study-II (MINTS-II) AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:488–498. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9524-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Danner F, Riggle ED. Is religiosity a protective factor against substance use in young adulthood? Only if you're straight! The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(5):440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowatt WC, Tsang J-A, Kelly J, LaMartina B, McCullers M, McKinley A. Associations between religious personality dimensions and implicit homosexual prejudice. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45(3):397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Smolenski DJ, Diamond PM, Ross MW, Rosser BRS. Revision, criterion calidity, and multigroup assessment of the reactions to homosexuality scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2010;92(6):568–576. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.513300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25(2):173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Kashubeck-West S, Meyer J. Internalized heterosexism: measurement, psychosocial correlates, and research directions. Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36(4):525–574. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;1:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. Census 2000. 2008 Apr 24; 2008. Retrieved January 12, 2009, from http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html.

- Wilkinson WW, Roys AC. The components of sexual orientation, religiosity, and heterosexuals' impressions of gay men and lesbians. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2005;145(1):65–83. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.145.1.65-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu AD, Li Z, Zumbo BD. Decoding the meaning of factorial invariance and updating the practice of multi-group confirmatory factor analysis: A demonstration with TIMSS data. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation. 2007;12(3):1–26. [Google Scholar]