Abstract

Introduction:

Somatostatin analogs (SSAs) are used as part of standard treatment for advanced neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). The mechanisms behind the antiproliferative action of SSAs remain largely unknown, but a connection with the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway has been suggested. Our purpose was to evaluate the activation status of the AKT/mTOR pathway in advanced metastatic NETs and identify biomarkers of response to SSA therapy.

Patients and methods:

Expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), phosphorylated (p)-AKT(Ser473), and p-S6(Ser240/244) was evaluated using immunohistochemistry in archival paraffin samples from 23 patients. Expression levels were correlated with clinicopathological parameters and progression-free survival under treatment with SSAs.

Results:

A positive association between p-AKT and p-S6 expression was identified (P = 0.01) and higher expression of both markers was observed in pancreatic NETs. AKT/mTOR activation was observed without the loss of PTEN expression. Tumors showing AKT/mTOR signaling activation progressed faster when treated with SSAs: higher expression of p-AKT or p-S6 predicted a median progression-free survival of 1 month vs 26.5 months for lower expression (P = 0.02).

Conclusion:

Constitutive activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway was associated with shorter time-to-progression in patients undergoing treatment with SSAs. Larger case series are needed to validate whether p-AKT(Ser473) and p-S6(Ser240/244) can be used as prognostic markers of response to therapy with SSAs.

Keywords: mTOR pathway, neuroendocrine tumor, somatostatin analogs

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) comprise a diverse group of rare malignancies, the incidence and prevalence of which have increased over recent decades, according to a recent analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database in the United States.1 Although most NETs present indolent progression, a significant number of patients are diagnosed presenting with unresectable or metastatic disease. These patients usually have a poor prognosis since limited systemic treatment options are available for this subgroup.

More than 80% of NETs express somatostatin receptors, and management of NETs has shown major improvement with the use of somatostatin analogs (SSAs), either alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents.2 SSAs, such as octreotide and lanreotide, are generally well-tolerated and are very efficient in alleviating hormone-related symptoms associated with functional tumors. Less well understood is the effect of SSAs in disease stabilization and remission.3–6

The mechanism(s) by which SSA treatment can be effective in controlling tumor growth are complex and poorly understood. The antiproliferative action of SSAs is mediated through interaction with specific cell surface somatostatin receptors (SSTR1–5) and recent data have highlighted the activation of downstream signaling pathways, particularly those involving mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), and protein kinase B (AKT), that ultimately mediate cell growth arrest and apoptosis.5–7 In this regard, an anti-proliferative action of octreotide in pancreatic and pituitary tumor cells mediated by altered PI3K signaling and AKT phosphorylation has been reported.8,9 More recently, octreotide was shown to exhibit significant antiproliferative effects on a rodent-derived insulinoma cell line by inhibiting phosphorylation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and ribosomal S6 kinase 1, key components of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, while the phosphorylation of AKT was unaffected.10 These results suggest that interplay exists between the mechanisms regulating the antiproliferative effects of SSAs and the AKT/mTOR pathway, which plays a central role in regulating protein synthesis, cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis.11

mTOR has recently emerged as an important target for cancer therapy. Particularly, in NETs, the relevance of the AKT/mTOR pathway became evident, with promising antitumor activity observed with the use of the mTOR inhibitors in combination with SSAs in phase II trials involving patients with NETs.12,13 The benefit of using everolimus, a rapamycin analog, in patients with advanced pancreatic NETs has been confirmed in the phase III RADIANT-3 trial, which showed that everolimus substantially prolonged disease-free survival compared with placebo across all patient subgroups, including those receiving prior and/or on-study SSA treatment.14,15

High expression rates of phosphorylated mTOR have been demonstrated in poorly differentiated NETs,16 and higher activity of the mTOR pathway was observed in foregut gastroenteropancreatic NETs showing a higher proliferative capacity.17 However, the correlation between mTOR expression and activity with the outcome of patients undergoing treatment with SSAs has not been investigated.

In this study, we evaluated activity of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in advanced metastatic NETs and identify tissue-based predictive biomarkers of response to therapy with SSAs.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

This clinical study was single-center, retrospective, and included samples obtained from a cohort of 23 patients with metastatic NET followed at the Department of Medical Oncology, Hospital de Santa Maria (HSM), Lisbon. Inclusion criteria were histological diagnosis of NET, stage IV disease according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer, more than 18 years old, and clinical history of treatment with the SSAs octreotide or lanreotide with available data on medical records regarding progression-free survival (PFS) after starting treatment with SSAs. We examined formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded samples of primary tumors or metastasis available in the Pathology Archive of HSM. The following clinicopathological parameters were recorded for each patient: age, sex, time of diagnosis, localization of primary tumor, site of metastasis, Ki-67 proliferation index, carcinoid syndrome at time of diagnosis, and positivity/negativity for somatostatin receptors upon octreoscan scintigraphy. PFS was defined as the time to progression after the beginning of treatment with SSAs.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of HSM in December 2009. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. All specimens were handled and made anonymous according to ethical and legal standards.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Briefly, 2.5-micron formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections, placed on positively charged slides, were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated using graded alcohol, and transferred to phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS). Microwave antigen retrieval was performed using a Tris-based buffer solution, pH 9.0 (S2367; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at 900 W for 30 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the slides in 1.5% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 minutes at room temperature. After rinsing, slides were incubated with primary antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature. The following antibodies were used: anti-phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (Ser240/244) rabbit polyclonal antibody (#2215; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; 1:80 dilution), anti-phospo-AKT (Ser473) rabbit monoclonal antibody (736E11, #3787; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:20 dilution), and anti- phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 28H6; Novocastra, Newcastle, UK; 1:30 dilution).

Visualization was achieved using the Dako REAL™ EnVision™ Detection System, peroxidase/DAB+, rabbit/mouse (K5007; Dako) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were then counterstained using Harris’s hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with Entellan® (Merck & Co, Whitehouse Station, NJ).

As a positive control for p-AKT (Ser473) and p-S6 (Ser240/244) immunostaining, a breast tumor sample was used since the mTOR pathway is frequently activated in breast cancer.18 As a negative control, primary antibodies were omitted.

Quantification and statistical analysis

For immunohistochemistry quantification, a semi-quantitative scoring index was established, which combined the intensity of staining (weak [1], moderate [2], and strong [3]) and the percentage of stained cells (0% [0]; 1%–25% [1]; 25%–50% [2]; 50%–75% [3]; 75%–100% [4]). The final score was assigned according to four categories: absent (0), weak (1–4), moderate (6–8) and strong (9–12), and was then dichotomized between low p-AKT or p-S6 expression (negative or weak staining) and high p-AKT or p-S6 expression (moderate or strong staining).

Statistical analysis was done with the software SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and GraphPad Prism 5.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA). Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between subjects expressing high or low p-AKT and p-S6 was made using the Fisher’s exact test and Chi-squared test when appropriate. Age was compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. PFS rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and difference in survival curves were analyzed using the log-rank test. Significance was defined by a P-value of less than 0.05.

Results

Clinical and pathological variable analysis

Twenty-three patients with advanced metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, 9 male and 14 female, ranging in age from 46 to 82 years (median age, 63 years), and enrolled from January 2000 to June 2010, were included in this study. Primary tumors were localized to the pancreas (7), small bowel (5), stomach (2), colon (2), lung (1), suprarenal (1), and bladder (1). The median duration of treatment with SSAs was 18 months (range 1–78 months). Twenty-two patients were treated with octreotide and one was treated with lanreotide.

The clinicopathological data of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and pathological data of patients included in this study

| n (23) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| Median (range) | 63 (46–82) | – |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 14 | 61% |

| Male | 9 | 39% |

| Tumor location | ||

| Pancreas | 7 | 30% |

| Small bowel | 5 | 22% |

| Stomach | 2 | 9% |

| Colon | 2 | 9% |

| Lung | 1 | 4% |

| Suprarenal | 1 | 4% |

| Bladder | 1 | 4% |

| Unknown | 4 | 17% |

| Type of sample | ||

| Primary tumor excision | 9 | 39% |

| Biopsy from metastasis | 14 | 61% |

| Site of metastasis | ||

| Liver | 15 | 65% |

| Other | 8 | 35% |

| Proliferation indexa Ki-67 ≥ 5% | 13 | 57% |

| Positive octreoscan scintigraphy | 18 | 78% |

| Carcinoid syndrome | 5 | 22% |

| Therapeutics | ||

| Somatostatin analogs (SSAs) | 7 | 30% |

| SSAs + chemotherapy | 6 | 26% |

| SSAs + IFN | 4 | 17% |

| SSAs + chemotherapy + IFN | 6 | 26% |

Note:

Proliferation index was measured by Ki-67 immunohistochemistry according to standard protocols in the Department of Pathology, HSM, Hospital de Santa Maria.

p-AKT, p-S6, and PTEN expression in NETs

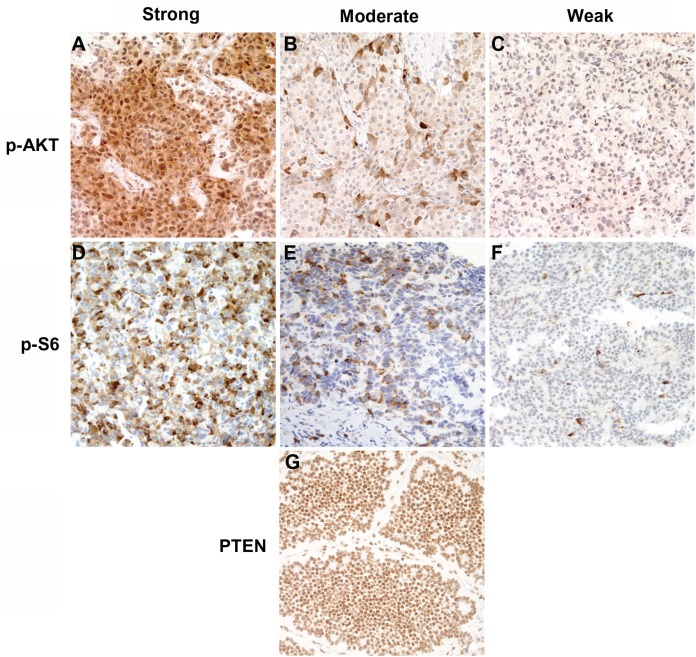

The expression and localization of p-AKT(Ser743), p-S6(Ser240/244), and PTEN in the 23 NET cases were examined using immunohistochemical analysis. p-AKT(Ser743) staining was observed in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments in 14 samples (61%). Staining was strong in 3 cases (13%), moderate in 4 (17%), and weak in 7 (30%) (Figure 1A–C). A total of 7 cases (30%) were shown to highly express p-AKT. p-S6(Ser240/244) staining was observed in the cytoplasmic compartment in 18 NET cases (78%). Four (17%), three (13%), and 11 (48%) cases showed strong, moderate, and weak staining, respectively (Figure 1D and E). A total of 30% of tumor samples showed high p-S6 expression. Expression of PTEN and nuclear staining was observed in all samples analyzed (Figure 1F). Twenty-two (96%) and one (4%) cases showed strong and moderate staining, respectively. Immunohistochemical analysis samples without primary antibodies showed no staining.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of phosphorylated AKT, p-AKT(Ser473) phosphorylated S6, p-S6(Ser240/244), and PTEN in neuroendocrine tumor samples using epitope-specific antibodies. (A–C) Representative images of p-AKT immunohistochemistry with anti-p-AKT(Ser473) antibody showing strong (A), moderate (B), and weak (C) staining. (D–F) Representative images of p-S6 immunohistochemistry with anti-p-S6(Ser240/244) antibody showing strong (D), moderate (E), and weak (F) staining. (G) PTEN immunohistochemistry with anti-PTEN showing strong staining.

Note: Original magnification: ×200.

Abbreviation: PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog.

Association of p-AKT and p-S6 expression with clinicopathological characteristics of NETs

Table 2 summarizes the association of p-AKT and p-S6 immunostaining with the clinicopathological parameters of the NETs examined. A significant positive association was observed between p-AKT and p-S6 expression. Five tumors with high p-AKT expression (71%) also showed high p-S6 expression (P = 0.01) (Table 2). p-AKT and p-S6 expression showed a positive association with primary tumor location; significantly higher expression of p-AKT and p-S6 was observed in pancreatic NETs versus tumors of non-pancreatic origin (P = 0.01 and P = 0.02, respectively). No other clinicopathological parameter showed significant correlation with p-AKT and/or p-S6 expression.

Table 2.

Correlation between p-AKT(Ser473) and p-S6(Ser240/244) expression and clinicopathological parameters

| Parameter | n | High p-AKTa (n) | P | High p-S6a (n) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor location | |||||

| Pancreas | 7 | 71% (5) | 0.012b | 71% (5) | 0.018b |

| Small bowel/stomach/colon | 9 | 22% (2) | 11% (1) | ||

| Other | 7 | 0% | 14% (1) | ||

| Liver metastasis | |||||

| Yes | 17 | 29% (5) | NSb | 24% (4) | NSb |

| No | 6 | 33% (2) | 50% (3) | ||

| Proliferation index | |||||

| Ki-67 < 5% | 10 | 20% (2) | NSb | 20% (2) | NSb |

| Ki-67 ≥ 5% | 13 | 38% (5) | 38% (5) | ||

| Carcinoid syndrome | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 40% (2) | NSb | 40% (2) | NSb |

| No | 18 | 28% (5) | 28% (5) | ||

| Therapeutics | |||||

| Somatostatin analogs (SSAs) | 7 | 14% (1) | NSb | 14% (1) | NSb |

| SSAs + chemotherapy/IFN | 16 | 38% (6) | 38% (6) | ||

| p-AKT expression | |||||

| Low expression | 16 | – | 13% (2) | 0.011b | |

| High expression | 7 | – | 71% (5) | ||

| p-S6 expression | |||||

| Low expression | 16 | 13% (2) | 0.011b | – | |

| High expression | 7 | 71% (5) | – | ||

| PTEN expression | |||||

| Low expression | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| High expression | 23 | 30% (7) | 30% (7) |

Notes:

High p-AKT and p-S6 expression correspond to moderate/strong staining score;

Fisher’s exact test was used for hypothesis-testing of the relationship between categorical variables and p-AKT or p-S6 expression.

Abbreviation: NS, nonsignificant.

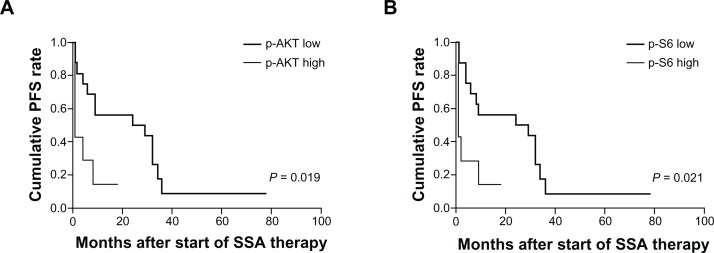

Correlation of p-AKT and p-S6 expression with PFS under SSA therapy

At the end of the follow-up period (June 2010), disease progression was observed in 19 of the 23 patients under SSA treatment (83%); the median PFS was 9 months (range 1–36).

However, when the dichotomized high/low expression groups were considered, patients highly expressing p-AKT(Ser743) and p-S6(Ser240/244) showed a significantly shorter PFS than those with low expression (log-rank test, P = 0.02 for both markers) (Figure 2A and B). Higher staining of p-AKT or p-S6 predicted a median PFS of 1 month versus 26.5 months for lower expression.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier progression-free survival curves for patients undergoing treatment with SSAs according to p-AKT (A) and p-S6 (B) expression scores.

Notes: Low p-AKT and p-S6 corresponds to absent/weak staining score; high p-AKT and p-S6 corresponds to moderate/strong staining score. P-values were calculated using a log-rank test.

Abbreviation: SSAs, somatostatin analogs.

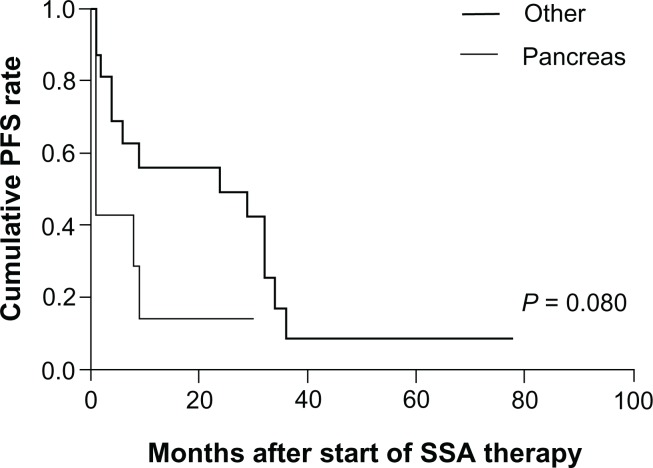

Considering the positive association observed between high p-AKT and p-S6 expression and pancreatic NETs, PFS curves were generated according to whether the primary tumor was located in the pancreas versus a different location (Figure 3). Although this variable also appeared to be associated with the outcome of SSA treatment, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (log-rank test, P = 0.08). Furthermore, in the subgroup of pancreatic NETs, median PFS was 1 month vs 19.5 months for higher and lower p-AKT expression, respectively (P = 0.023).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier PFS curves for patients undergoing treatment with SSAs according to primary tumor localization.

Note:P-value was calculated using a log-rank test.

Abbreviations: PFS, progression-free survival; SSA, somatostatin analog.

In this study, we found no correlation between Ki-67 proliferative index and PFS using a Ki-67 cut-off of 5% (log-rank test, P = 0.69).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we sought to evaluate the baseline activation status of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in advanced metastatic NETs and identify factors predictive of response to therapy with SSAs.

Immunohistochemical analysis of p-AKT(Ser473), p-S6(Ser240/244), and PTEN expression was assessed in a cohort of 23 tumor samples, including NETs from seven different anatomical sites of origin. Phosphorylation of AKT at Ser473 has been widely studied as a marker of AKT signaling pathway activity, while the phosphorylation targets of mTOR, such as S6 ribosomal protein phosphorylation at the Ser240/244 site, are preferred endpoints for assessing mTOR activity.19 Our results show that most tumors exhibited p-AKT and p-S6 expression (14/23 and 18/23, respectively) as a result of AKT/mTOR pathway activation. Higher expression of either p-AKT or p-S6 was observed in pancreatic NETs and a significant positive association between p-AKT and p-S6 expression was identified. Additionally, we found evidence of AKT/mTOR signaling activation without PTEN loss, an observation that has been also reported by Meric-Bernstam et al based on immunohistochemical analysis of 25 NET samples.20 Although previous studies have reported a frequency of PTEN loss between 10% and 29% in pancreatic NETs,21,22 all 23 tumor samples evaluated in this study showed moderate/strong PTEN staining. Loss of PTEN is one of the main causes of AKT/mTOR pathway activation; however, there are other known mechanisms responsible for activating this signaling pathway, such as PTEN mutations, AKT amplification, and mutations of the p110 and p85 subunits of PI3K.23 The investigation of the mechanism(s) involved in activating the AKT/mTOR pathway in these patients will be examined in future studies.

Although the activity of the AKT/mTOR pathway and its prognostic relevance have been evaluated for many different cancer types (eg, renal cell carcinoma,24 sarcoma,25 breast cancer,18,26 hepatocellular carcinoma27), only a few prior studies have examined AKT/mTOR activity in NETs. Expression of phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR) was analyzed in a series of 20 gastropancreatic NETs, and a higher expression rate of p-mTOR was observed in poorly differentiated tumors.16 In a large study examining expression of mTOR pathway components in lung NETs, the authors reported overexpression of p-4EBP1 in high-grade tumors, whereas p-mTOR and p-S6K were highly expressed in low-grade tumors.28 In another study, expression of phosphorylated mTOR, 4EBP1, and ribosomal protein S6 was evaluated together with the expression of somatostatin receptors, extracellular regulated kinase, and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Hierarchical clustering analysis of immunohistochemical data led to the classification of NETs into 3 distinctive subgroups with potential biological significance.29 These three studies were mainly descriptive and the association between expression levels of the proteins investigated with clinicopathological variables and outcomes was not addressed.

Recently, Kasajima et al reported the expression of mTOR as well as the phosphorylation of its downstream targets, 4EBP1, p70S6K, and eIF4E, in a cohort of 99 human gastroenteropancreatic NETs. The authors reported positive mTOR expression in 61% of tumors and higher mTOR expression levels when distant metastases were present. They also reported higher p-S6K expression associated with shortened disease-specific survival in patients with stage IV mid-gut tumors.17

We identified AKT/mTOR signaling activation, particularly p-AKT and p-S6 levels, to be prognostic markers of disease-free survival in advanced metastatic NETs under treatment with SSAs. We showed that tumors with higher p-AKT(Ser743) or p-S6(Ser240/244) expression levels progressed faster in patients undergoing treatment with SSAs; higher staining of p-AKT or p-S6 predicted a median PFS of 1 month versus 26.5 months for lower expression. In the past year, the molecular mechanisms of mTOR inhibitors in patients with progressive advanced pancreatic NETs12–14 have begun to be elucidated. A gene expression profile study conducted in a large panel of sporadic pancreatic NETs revealed that TSC2 and PTEN, two key inhibitors of the AKT/mTOR pathway, were downregulated in most of the primary tumors. The authors further reported a significant association between low TSC2 and PTEN expression and an increased rate of cell proliferation and shortened progression-free and overall survival.30 Recently, Jiao et al used an exome sequencing strategy to identify recurrent somatic mutations in pancreatic NETs and found that 14% of tumor samples analyzed contained mutations in mTOR pathway genes, including TSC2, PTEN, and PI3K.31 Our results correlate with these findings, supporting the role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in NETs progression, and further support the hypothesis that expression and activity patterns of AKT/mTOR in NETs can be used to predict response to therapy.

The tumor proliferative index assessed using Ki-67 immunohistochemistry has been considered a standard marker for therapeutic decisions in NETs. Based on the results of a prospective phase IV trial designed to assess the efficacy of octreotide in advanced nonfunctioning pancreatic NET, it was suggested that a Ki-67 index ≥ 5% and/or the presence of weight loss could justify more aggressive therapy without waiting for radiologically proven progression of disease.32 In this study, no clear association was observed between Ki-67 proliferation index and response to octreotide or lanreotide therapy when a cut-off value of 5% was considered, likely because of the low number of patients examined. In our study, the decision to prescribe SSAs was not supported by the Ki-67 index alone, but was also based on the presence of hormonal syndrome. Furthermore, a significant proportion of patients received other treatments (such as chemotherapy) in addition to SSAs during the time course of the disease.

Conclusion

Our data strongly suggest that constitutive activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway in NETs is associated with a shorter time to progression in patients undergoing treatment with SSAs. We showed that high expression of either p-AKT(Ser473) or p-S6(Ser240/244) predicts shorter PFS in a series of advanced metastatic NETs. Due to the small size and heterogeneity of the series analyzed, this study was only hypothesis-generating and must be expanded to a larger cohort. Further studies of additional case series will allow validation of p-AKT(Ser473) and p-S6(Ser240/244) as prognostic markers of response to therapy with SSAs, and an investigation of the clinical applicability of these markers will aid in the selection of patients who will most likely benefit from SSAs and mTOR inhibitors in combination.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patients who contributed to this study. This work was partially supported by a grant provided by Novartis Oncology in Portugal and from the association for research and development of the school of medicine in Lisbon. The funders had no part in data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, or writing the paper.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Öberg KE. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 7):vii72–vii80. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksson B, Oberg K. Summing up 15 years of somatostatin analog therapy in neuroendocrine tumors: future outlook. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(Suppl 2):S31–S38. doi: 10.1093/annonc/10.suppl_2.s31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreno A, Akcakanat A, Munsell MF, Soni A, Yao JC, Meric-Bernstam F. Antitumor activity of rapamycin and octreotide as single agents or in combination in neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15(1):257–266. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Shimon I, Korbonits M, Grossman AB. Somatostatin analogs in the control of neuroendocrine tumours: efficacy and mechanisms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15(3):701–720. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rinke A, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: a report from the PROMID Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4656–4663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pyronnet S, Bousquet C, Najib S, Azar R, Laklai H, Susini C. Antitumor effects of somatostatin. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286(1–2):230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charland S, Boucher MJ, Houde M, Rivard N. Somatostatin inhibits Akt phosphorylation and cell cycle entry, but not p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation in normal and tumoral pancreatic acinar cells. Endocrinology. 2001;142(1):121–128. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theodoropoulou M, Zhang J, Laupheimer S, et al. Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, mediates its antiproliferative action in pituitary tumor cells by altering phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling and inducing Zac1 expression. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1576–1582. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Franchi G, Teng M, et al. Octreotide and the mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) block proliferation and interact with the Akt-mTOR-p70S6K pathway in a neuro-endocrine tumour cell Line. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87(3):168–181. doi: 10.1159/000111501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dancey JE. Therapeutic targets: MTOR and related pathways. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5(9):1065–1073. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.9.3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao JC, Phan AT, Chang DZ, et al. Efficacy of RAD001 (everolimus) and octreotide LAR in advanced low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4311–4318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao JC, Lombard-Bohas C, Baudin E, et al. Daily oral everolimus activity in patients with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors after failure of cytotoxic chemotherapy: a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):69–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):514–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah MH, Lombard-Bohas C, Ito T, et al. Everolimus in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNET): Impact of somatostatin analog use on progression-free survival in the RADIANT-3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(Suppl) Abstr 4010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shida T, Kishimoto T, Furuya M, et al. Expression of an activated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65(5):889–893. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasajima A, Pavel M, Darb-Esfahani S, et al. mTOR expression and activity patterns in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18(1):181–192. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akcakanat A, Sahin A, Shaye AN, Velasco MA, Meric-Bernstam F. Comparison of Akt/mTOR signaling in primary breast tumors and matched distant metastases. Cancer. 2008;112(11):2352–2358. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cloughesy TF, Yoshimoto K, Nghiemphu P, et al. Antitumor activity of rapamycin in a Phase I trial for patients with recurrent PTEN-deficient glioblastoma. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meric-Bernstam F, Rashid A, Crosby K, et al. Biomarker analysis for the phase II study of RAD001 (everolimus) and depot octreotide (Sandostatin LAR) in advanced low grade neuroendocrine carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(16):2461–2473. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung DC, Brown SB, Graeme-Cook F, et al. Localization of putative tumor suppressor loci by genome-wide allelotyping in human pancreatic endocrine tumors. Cancer Res. 1998;58(16):3706–3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perren A, Komminoth P, Saremaslani P, et al. Mutation and expression analyses reveal differential subcellular compartmentalization of PTEN in endocrine pancreatic tumors compared to normal islet cells. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(4):1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64624-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(8):627–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pantuck AJ, Seligson DB, Klatte T, et al. Prognostic relevance of the mTOR pathway in renal cell carcinoma: implications for molecular patient selection for targeted therapy. Cancer. 2007;109(11):2257–2267. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwenofu OH, Lackman RD, Staddon AP, Goodwin DG, Haupt HM, Brooks JS. Phospho-S6 ribosomal protein: a potential new predictive sarcoma marker for targeted mTOR therapy. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(3):231–237. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aleskandarany MA, Rakha EA, Ahmed MA, Powe DG, Ellis IO, Green AR. Clinicopathologic and molecular significance of phospho-Akt expression in early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127(2):407–416. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou L, Huang Y, Li J, Wang Z. The mTOR pathway is associated with the poor prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2010;27(2):255–261. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Righi L, Volante M, Rapa I, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling activation patterns in neuroendocrine tumors of the lung. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(4):977–987. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iida S, Miki Y, Ono K, et al. Novel classification based on immunohistochemistry combined with hierarchical clustering analysis in nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumor patients. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(10):2278–2285. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Missiaglia E, Dalai I, Barbi S, et al. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: expression profiling evidences a role for AKT-mTOR pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):245–255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science. 2011;331(6021):1199–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.1200609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butturini G, Bettini R, Missiaglia E, et al. Predictive factors of efficacy of the somatostatin analog octreotide as first line therapy for advanced pancreatic endocrine carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(4):1213–1221. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]