Abstract

Quantitative studies indicate that HIV incidence in Zimbabwe declined since the late 1990s, due in part to behavior change. This qualitative study, involving focus group discussions with 200 women and men, two dozen key informant interviews, and historical mapping of HIV prevention programs, found that exposure to relatives and close friends dying of AIDS, leading to increased perceived HIV risk, was the principal explanation for behavior change. Growing poverty, which reduced men’s ability to afford multiple partners, was also commonly cited as contributing to reductions in casual, commercial and extra-marital sex. HIV prevention programs and services were secondarily mentioned as having contributed but no specific activities were consistently indicated, although some popular culture influences appear pivotal. This qualitative study found that behavior change resulted primarily from increased interpersonal communication about HIV due to high personal exposure to AIDS mortality and a correct understanding of sexual HIV transmission, due to relatively high education levels and probably also to information provided by HIV programs.

Keywords: Zimbabwe, HIV decline, Behavior change, Qualitative research, Prevention programs, Program mapping

Introduction

Zimbabwe has experienced one of the most severe HIV epidemics globally [1] but, since the late 1990s, has also witnessed one of the most substantial and sustained declines in HIV prevalence [2, 3]. The country’s most recent national estimates, based on HIV sentinel surveillance data collected from pregnant women attending routine check-ups at antenatal clinics, indicate that HIV prevalence among adults aged 15–49 years peaked at around 29% in 1997 and then fell to about 16% in 2007 [3].

AIDS mortality reached very high levels by the late 1990s [2, 4] and certainly contributed to the stabilization of HIV prevalence at around this time. However, mathematical models fitted to the HIV sentinel surveillance data used to generate the national estimates of HIV prevalence suggest that the pattern of stabilization and decline observed in the data could only have occurred in the presence of substantial changes in risk behavior, most likely concentrated in the period 1999–2004 [5]. This finding, in turn, is consistent with findings from a comprehensive review of data from national and local behavioral surveys [2, 3]. In that review, there was compelling evidence for reductions in the proportions of men and women with commercial and other multiple sexual partnerships along with sustained high levels of condom use among those continuing to engage in casual or commercial partnerships. Data from successive Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) [6], Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs and Practices surveys conducted by Population Services International [7], and from successive rounds of the Manicaland General Population Cohort Survey [8] all showed consistent reductions in men and women reporting non-regular sexual partnerships, and other indications of partner reduction, occurring during the period 1998–2007 [3]. Condom use even in casual encounters appears to have been low in Zimbabwe up until the late 1980s, but reported use reached relatively high levels (e.g., 72% at last sex with a non-regular partner among males) by the time of the first nationally representative survey in 1999, and remained at similar levels through 2007 [3].

While there is now general agreement that HIV prevalence has fallen in Zimbabwe and that this was due, in part, to changes in sexual behavior, there remains uncertainty as to the factors that led to these changes in behavior. In this paper, we summarize data from a historical mapping of HIV–AIDS interventions as well as focus group discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews conducted to assess local perceptions concerning the forms and timing of changes in behavior that had occurred and the factors that were believed to be most important in bringing about these changes.

Methods

The combined approach of utilizing both FGDs/interviews and a historical mapping methodology was selected for this study in order to do justice to the complex variety of factors, including social, economic and cultural aspects and a range of program activities, which could potentially have influenced the observed risk reduction and behavioral changes.

Focus Group Discussions and Key Informant Interviews

In September–November of 2007, 16 FGDs were conducted with a total of 200 men and women. FGDs were conducted in five out of Zimbabwe’s ten national provinces: twelve in seven different urban and rural sites in the predominantly Shona speaking north and south-east of the country, and four in two different urban and rural sites in the Ndebele speaking south-west. Equal numbers of FGDs were conducted among men and women separately, using same-sex moderators. Participants aged 32–55 years were targeted so that most would have been aged between 16 and 40 years in the early 1990s and would remember practices and norms about sexual behaviors from the early 1990s onwards. Since it was known to potential participants that the study was about HIV–AIDS, particular attention was paid to avoiding over-representation of individuals personally affected by HIV or formally involved in the HIV response.

Once the sites were selected, researchers were introduced through local institutions and participants were recruited on-site according to the pre-established selection criteria. FGDs had an average of 11 participants (mostly between 7 and 12) per group. About half (52%) of the participants were male and 48% were female. The average age of participants was 42 years, and 56, 24 and 20% of participants were considered low, middle and high income, respectively. A quarter (26%) lived in urban areas (including Harare, Bulawayo and a district town), 20% lived in peri-urban areas (high-density suburbs of Harare and Bulawayo), and 54% lived in rural areas (including rural service centers and growth points, including one along the main highway to South Africa). Participants came from a wide range of occupations (informal vendors, self-employed entrepreneurs, senior bankers, businessmen, teachers, rural farmers and sex workers) and educational levels (none, primary, secondary and tertiary). When compared to data from the 2005/06 Zimbabwe DHS, the overall sample was found to be roughly representative of the Zimbabwean population.

The FGDs adhered to a consistent structure. For three discrete historical time periods, specific aspects of sexual behavior, the underlying factors related to such behaviors, and potentially related programmatic activities were explored. These time periods were for: (1) “around 1992” (the time of a large, still well-remembered drought), (2) “around 1999” (when a major, well-remembered constitutional referendum was held) and (3) “the present” (2007) (see Fig. 1). These time periods were chosen to permit systematic investigation of differences in behavior and related underlying factors which may have occurred both prior to and during the phase of the epidemic when HIV incidence would have peaked and begun to decline (the late 1990s/early 2000s period) [2, 3]. To improve recall for each time period, participants were asked to begin the discussion by describing specific key public events or personal experiences that had occurred at these particular times.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the Focus Group Discussions

The FGDs were recorded, transcribed and analyzed using a combination of methods. Due to the complexity of the issues and the variety of nuances, it was decided that the use of analysis software would not have added sufficient value. However, electronic searches were carried out using all the transcripts regarding key topics, to establish the frequency and context of statements [9]. For each FGD, the most commonly occurring statements and the most prevalent responses to the standard questions around which consensus was reached by the groups were summarized by the FGD facilitators and note-takers following each group, using a matrix conforming to the structure of Fig. 1. Findings were analyzed and disaggregated by sex and urban/rural setting.

In addition, between 2006 and 2009 two dozen in-depth, semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted with senior experts and managers in organizations involved in the HIV response, including from the Ministry of Health, the National AIDS Council, bilateral funding partners, the UN organizations, civil society and individual researchers, and other informants recruited through a “snowball” type of ethnographic methodology [8].

Historical Mapping of HIV and AIDS Programs

This component of the methodology comprised a comprehensive desk review including examination of 250 abstracts of HIV-related research and evaluations [10], 120 articles, various other publications and program review reports, a number of national HIV program reports, including a comprehensive review of behavior change programs [11], a large number of information, education and communication (IEC) materials, sexually transmitted infection (STI) control activities [12] and a review of condom programming. Data from national surveys, routine information systems, implementers’ program reports and inventories of AIDS service organizations and programs were analysed to establish trends in programmatic coverage in relation to the estimated period of the main reduction in HIV risk within Zimbabwe (1999–2004) [5].

Results

The results are presented in the following logical sequence: (1) forms and timing of changes in sexual behavior; (2) the perceived influence of underlying socio-economic or cultural factors on such behavioral changes; and (3) the potential impact of HIV prevention programs. In each case, the findings are compared for the three distinct time points covered in the focus group discussions. Finally, we present the findings from the historical mapping of HIV–AIDS programs.

Qualitative Research Findings

Forms and Timing of Behavior Change

All FGD participants characterized the pattern of sexual behavior in the period around 1992 as one of risky sexual practices, typically involving different forms of multiple sexual partnerships, including both longer-term concurrent relationships and, especially, the common occurrence of commercial and casual sex. Many statements indicated that, in the early 1990s, multiple partnerships were common among males and females, across different social groups, and in both urban and rural areas.

In those years, it was said “a fighting bull is seen by its bruises”. Men had many women. I can’t say how many per year, but they were many. More than five for one. (Men, rural site)

In the 1990s, there was a lot of enjoyment/fun. Men did not bring their wages to the family. Wives would have affairs too to try to get even and also in a bid to get money to look after their children. (Women, periurban area, Harare)

Descriptions of multiple partnerships were reinforced by detailed information provided in the FGDs about settings in which sexual relations were established, including work-places, social clubs, parties, schools, tertiary institutions, and places where traditional beer was brewed. In addition, commercial sex was common particularly at bars and beer halls in towns, suburbs, townships and growth points. Male participants generally estimated that, in the early 1990s, most urban men had at least two or three sexual partners per year and, in addition, many of them “caught” up to three or four sex workers a week, while most rural men were said to have had at least two sexual partners a year. A variety of practices were described, including various forms of transactional sex that included group practices such as male students pooling funds for sex workers. Condom use around 1992 was said to be low and inconsistent, even in casual relationships and contacts with sex workers.

Descriptions of sexual behaviors in the period around 1999 varied. Many statements described an increasing disengagement from such partnerships, by both sexes, in urban as well as rural areas.

A lot of people had died. People were beginning to reduce their numbers of partners. Friends were sanctioning each other. (Men, rural southern Zimbabwe)

There was a sense of panic because people were concerned by what was happening. Women could complain to their husbands to behave themselves, citing examples of sick men in the neighborhood. (Women, peri-urban area, Harare)

Also, for example, it was often stated in the FGDs and interviews that, whereas in earlier years it was commonplace for men gathering at locales such as beer halls to be surrounded by women/sex workers, by the end of the 1990s this norm had changed and it was now typical for men to gather strictly among themselves at such places, and generally to “ignore” any women that might be present. (Some people stated that it had even become considered “rude” for a man to be accompanied by a female in such instances.)

However, other statements indicated that multiple sexual partnerships were still common among some groups. These included “men with money” such as self-employed home industry entrepreneurs, gold panners, truck drivers, bus crew, cross-border traders, men in uniformed forces, and mobile workers. Condoms were said to be used frequently in sex with casual partners and sex workers, but not in longer-term relations.

As with the period around 1999, the most recent period (2007) was characterized as a time of further disengagement from multiple partnerships. Exceptions were men with greater incomes including those dealing in basic commodities or foreign currency, truck drivers, gold/diamond panners, cotton/tobacco farmers, cross-border traders, young sex workers and, in some cases, young people with “parents in the Diaspora.” Descriptions of multiple sexual partnerships were generally limited to long-term concurrent sexual partnerships (“small houses”) and to cross-generational sex, which some people were still said to be engaging in. There were diverging statements on “small house” relationships, with some participants suggesting that the phenomenon became common in the late 1990s, when men reduced contacts with sex workers and had less casual sex, while others asserted that only the name “small house” was new at that time. Some, but not all, participants suggested that there had been a reduction in “small houses” by 2007. The majority of statements about condom use around 2007 were similar to the observation for the previous period; i.e., that usage was high in casual and commercial relations but low within marriage and other longer-term partnerships.

I think HIV and AIDS cannot be denied so people accept condoms. In marriage there are problems (of resistance to condoms) (Women, rural southern Zimbabwe)

Overall, the analysis of the focus group transcripts suggests a clear trend towards a reduction in multiple sexual partnerships, particularly casual sex partners, and an increase in condom use with casual partners. In each case, these changes appear to have begun roughly around the 1999 period and were further reinforced by 2007. Although these trends were reported in all the FGDs (i.e., in both urban/rural settings and among men/women), partner reduction was reported most consistently in the discussions with men. The increase in condom use was reported most consistently in the female FGDs, particularly those with sex workers.

Influence of Underlying Socio-Economic and Socio-Cultural Factors

In this section, we summarize the data on why people engaged in the behaviors described and participants’ perceptions of how underlying changes in the socio-economic and cultural context contributed to changes in behavior during the specified time periods.

For the period around 1992, which had been described as a time when multiple partnerships were commonplace, these partnerships were often associated with particular socio-economic factors and cultural practices. For example, participants attributed high levels of concurrent sexual partnerships to spousal separation, with males having to seek employment in places such as farms, mines or civil service positions outside their home areas, while females stayed in their “rural homes.” In periods of hardship, such as droughts, food insecurity was mentioned as a factor pushing women into transactional sex (“selling sex for food”). Other statements attributed multiple partnerships to notions of masculinity. In particular, respondents mentioned that those men who had multiple sexual partners were seen as being “more manly,” and thus, for instance, many men considered it a “badge of manhood” to acquire an STI. Some other statements mentioned specific factors driving casual sex such as high alcohol consumption and men using herbs which were said to enhance libido (vhuka-vhuka). Participants also noted that the cultural practices of wife inheritance and wife replacement (chigaramapfiwa) were still common during this period.

For the period around 1999, respondents recalled both continued multiple sexual partnerships but also the beginnings of considerable risk reduction. The dominant theme in their statements to explain the underlying reasons for risk reduction around 1999 was the great and growing fear induced by the increased visibility of HIV-related illnesses and AIDS deaths among neighbors, relatives, friends and colleagues, which most participants said they had experienced personally. This was reinforced by a variety of vivid descriptions, such as frequent funerals occurring in the same neighborhood and recollections of “unusually high numbers of babies born ill” and dying within a year of birth, often followed by their parents. In contrast to the findings for the 1992 period, in several FGDs participants said that, by the end of the 1990s, it had become “shameful” to have an STI or to be seen with sex workers or sexual partners other than one’s spouse.

If one caught an STI, the clinics would encourage people to come together with their partners for treatment. This would discourage people from sleeping with too many women. (FGD with men, rural northern Zimbabwe)

These days when a man is said to have two or more wives, he is seen as uncivilized. (FGD with urban men, Harare)

In some of the FGDs, respondents stated that communities had begun to drop the cultural practices of wife inheritance and replacement wives, as they witnessed AIDS-related deaths occurring in families that followed such practices.

In addition, many respondents described two diverging economic trends. Specific groups were said to be economically empowered, which was felt to be a reason for “buying sex.” At the same time, steadily increasing poverty led men to disengage from paid sex, especially in rural and other poorer areas.

For the period around 2007, FGD respondents said that the personal experience of having friends or relatives affected by AIDS continued to be important for risk reduction. Even more consistently than for the period around 1999, respondents describing the situation in 2007 focused on the now very severe economic decline which, it was said, had made it increasingly difficult for men to visit bars, pay for sex and/or to maintain longer-term extramarital partners (“small houses”).

It’s no longer happening. People cannot afford to look after many women. (Men, peri-urban area, Harare)

Female sex workers confirmed this trend by noting the difficulty they faced in “catching men” except for those (relatively few) men who were “awash with cash,” such as “dealers” and gold and diamond panners. In summary, the stark increase in AIDS-related morbidity and mortality was the most consistently cited reason for reductions in multiple partnerships, and especially reductions in casual sex, which were reported as having begun during the late 1990s. Furthermore, study participants made many references to a partial shift in social norms towards reduced acceptability of casual sex and payment for sex, also commencing around the late 1990s. While the economic decline was frequently cited as a reason for women to engage in transactional sex, this was also mentioned consistently as a factor reducing the ability of men to attend bars and otherwise afford multiple partnerships.

Impact of HIV Prevention Programs

Study participants in both urban and rural areas recalled that few HIV/AIDS-related services were available during the early 1990s period, as illustrated by the following two responses, which confirmed that while condoms were available at local health centers and from community-based distributors, they were targeted mainly at married adults for use in family planning:

I remember family planning programs. There was nothing on AIDS. (FGD with men, peri-urban area)

…[The] government had some community health workers that moved around with condoms and on top of that they also moved with family planning pills for preventing pregnancies. (FGD with rural men, south-east Zimbabwe)

Treatment services for STIs were also available at local health centers. Some churches promoted abstinence and fidelity. A few of the FGD participants who had been in school at the time remembered the beginnings of the national HIV/AIDS Life Skills program. Some information about HIV/AIDS was provided by radio stations but, overall, coverage in the mass media appears to have been limited. Some statements suggest that the available programs and messages were not yet taken very seriously by the majority of the population.

We did not care, because if you had an STI you would rush to go and get treatment by way of injections and you would be cured. We did not think this disease [AIDS] would also be there … (FGD with rural men, south-east Zimbabwe)

At that time, HIV/AIDS was often viewed as an alien disease affecting people in other countries but not in Zimbabwe.

By the period around 1999, study participants remembered there being a marked increase in programmatic activity, led by the National AIDS Council and also involving churches and NGOs. Programs implemented HIV prevention and impact mitigation activities in the form of home-based care and support for orphans and vulnerable children. A number of new media programs were launched, while a (donor-sponsored) documentary Todii (“What shall we do?”), based on a very popular song released in 1999 by the famous performer Oliver Mtukudzi, addressed—in starkly blunt and moving terms—the grave risks and social consequences of HIV infection. Several key informant interviewees believed that this song, and the cultural influence generally of icons like Mtukudzi, played a pivotal role in ultimately inspiring increased awareness of AIDS and the need for behavior change to avoid infection. Mean-while, churches continued to promote abstinence and fidelity while health centers and NGOs also promoted and distributed condoms. Participants mentioned a broader range of activities than in the previous period, including services provided by hospitals and clinics as well as information provided by NGOs and church activities. Some mentioned that voluntary counseling and testing began to become available around this time. Distribution of condoms by community health workers and clinics was frequently mentioned by participants. Some felt that heightened awareness of HIV/AIDS resulting from concerted multimedia and community-based campaigns had helped change people’s behavior. As illustrated by the following statement, the effect of programs was frequently linked to the impact of increased mortality:

It was because of those programs that the government had started, the programs made men reduce their speed…and in reality, the death toll, people saw it for themselves…. If you see people handling corpses of dead relatives with gloves when they used to do it with their hands… (FGD with rural men, south-eastZimbabwe)

By the mid-2000s, a wide range of HIV prevention programs was said to be in place. These included behavior change messages transmitted to the general population through the print and electronic media; information, education and communication (IEC) materials, school programs targeting youth, peer education programs targeted at various groups, and widespread availability of condoms in shops. Through this combination of mass media and interpersonal communication activities, many male and female FGD participants reported that they had become well-informed about HIV/AIDS and more cautious about having unprotected sex. However, when asked which programs or messages had caused the biggest impact, few were able to link the reported behavior changes to specific programs or messages, as illustrated by the following responses:

I think seeing people become sick with and die from AIDS has been very powerful. (Another participant adds:) I think awareness has been effective. There is increased VCT uptake and condom use. (A third participant adds:) I think education has been effective. ZICHIRE (name of an organization working in growth points at that time) did a good job of it. Many people were tested for HIV as a result. (A fourth participant adds:) For me, training and awareness made me abstain before marriage and, in marriage, I am faithful to my husband. (FGD among women, growth point, south-east Zimbabwe)

Visiting the hospital … and seeing sick people there has been effective. I think that going to any cemetery to bury a relative and seeing how many burials are taking place concurrently and throughout the day: it instills fear/makes one think seriously. (FGD among low-income urban women)

Historical Mapping of HIV Prevention Programs

In the historical mapping exercise, we considered three aspects of HIV prevention activity: (1) leadership and policy; (2) information, awareness and behavior change programs; and (3) HIV prevention services. These findings are described in the following section.

Leadership and Policy

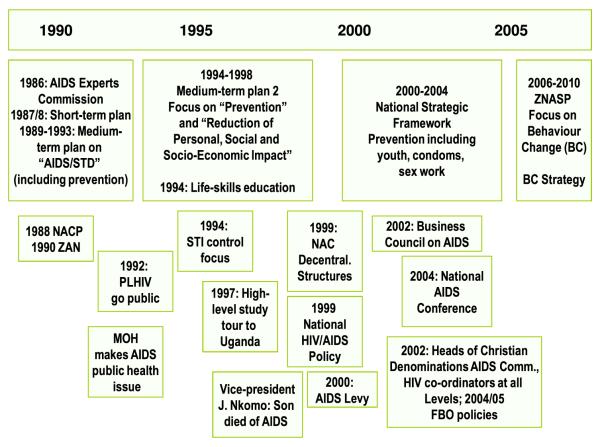

After the Ministry of Health established the AIDS Control Programme in 1986, a short-term (1987–1988) and two medium-term (1989–1993 and 1994–1998) plans were implemented (Fig. 2). While the initial focus was on health activities such as blood safety, infection control, surveillance and IEC, the 1st medium term plan (1989–1993) expanded these activities to include messages on the ABCs (Abstain, Be faithful, use Condoms) of HIV prevention. During the implementation of this first medium-term plan, the Minister of Health made HIV a major public health issue. After 1996, when a high level delegation of government ministers, provincial governors, traditional leaders and civil society representatives participated in a study tour to Uganda, more government ministers, Vice-President Nkomo and President Mugabe began to talk more openly about AIDS. The period of major risk reduction (1999–2004) [5] coincides with the development of a National HIV and AIDS Policy and the establishment of the National AIDS Council (NAC) in 1999, as well as the introduction of an AIDS levy and National AIDS Trust Fund in 2000. The National Strategic Framework of 2000–2004 designed HIV prevention around issues of youth involvement, condom promotion and sex work programming. The introduction of National AIDS Council structures at national, provincial, district, ward and village level allowed leadership at all levels to play a role in the national response.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of key events around policy and leadership in HIV programming. Source: Prepared based on findings from the research report on historical mapping of HIV programs

Yet, although policies and public debate have included “ABC” messages since the early 1990s, there are no clear indications that a shift in policy focus, or an increase in coverage of specific messages from leadership coincides in timing with specific behavioral changes, such as partner reduction, seen in survey data between 1999 and 2005/06 [2, 3]. The observed increases in leadership involvement, commitment to HIV and AIDS as a multi-sector issue, and comprehensiveness of policies may, however, have contributed to the considerable increase in interpersonal communication about HIV and AIDS during the late 1990s (see discussion below and Fig. 5).

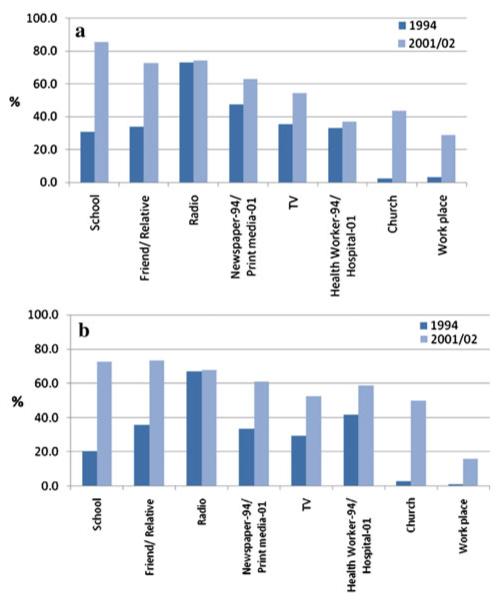

Fig. 5.

Percentage of men (graph a) and women (graph b) 15–29 years who ever received HIV/AIDS information from selected sources (DHS 1994, Young Adult Survey 2001/02)

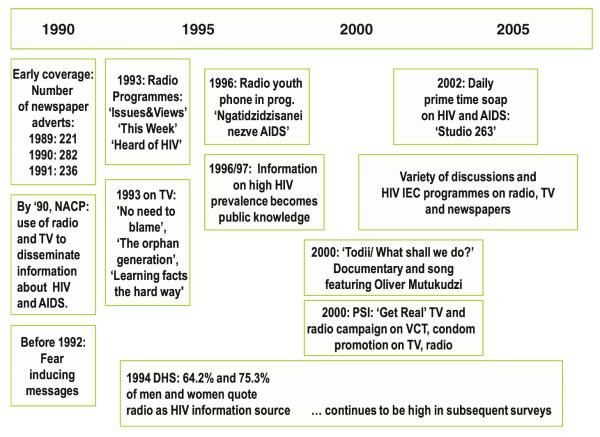

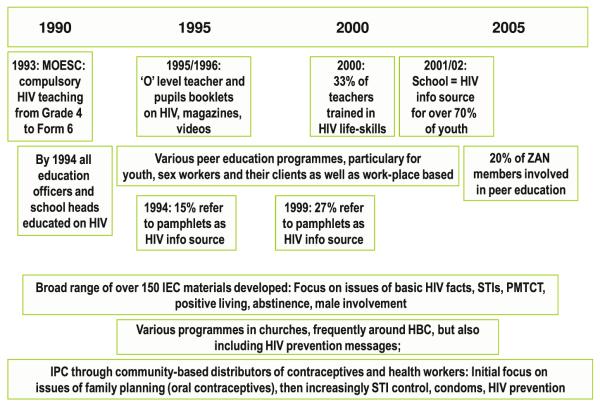

Information, Awareness and Behavior Change Programs

HIV prevention communication programs were implemented in Zimbabwe from the early 1990s onwards and comprised both mass media and interpersonal communications (Figs. 3,4). As early as in the 1994 DHS national survey [13], a majority of the sexually active population reported having received information through the mass media, with radio being the major source of information, followed by the print media and TV (Fig. 5). Service statistics show that, by 2000, 33% of teachers had been trained in life-skills education and the DHS survey in 2001 found that 73 and 85% of young women and men (15–29 years), respectively, had received HIV/AIDS information in school [14].

Fig. 3.

Timeline of key mass media programs on HIV and AIDS. Source: Prepared based on findings from the research report on historical mapping of HIV programs

Fig. 4.

Timeline of key interpersonal communication initiatives on HIV and AIDS. Source: Prepared based on findings from the research report on historical mapping of HIV programs

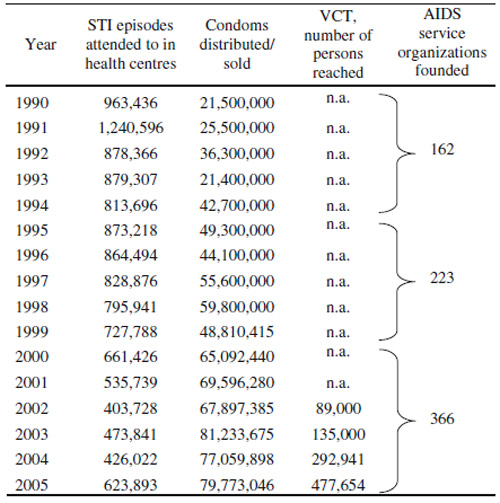

During the period of main risk reduction, new media programs (such as “Studio 263” and “Get Real TV”) were launched. The popular song by Oliver Mtukudzi, Todii (“What shall we do?”), and a related documentary aired in 2000 were widely heard and viewed. (Mtukudzi had earlier recorded another song about AIDS, “Stay with one woman.”) Between 2000 and 2005, 366 new AIDS Service Organizations were founded across Zimbabwe, nearly as many as in the entire prior decade (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Trends in HIV prevention service provision

Sources: STI treatment [12], condoms (presentation by Sunday Manyenya, UNFPA 2007), VCT (presentation by Karin Hatzold, Populations Services International, 2008), AIDS Service Organizations (data obtained from Zimbabwe AIDS Network)

NA not available

It proved impractical to aggregate historical coverage data on the multiplicity of community-based, work place, church and other interpersonal communication projects during the main years of risk reduction. However, a comparison of 1994 DHS and the 2001/02 Young Adult Survey data (Fig. 5) suggests that, while mass media coverage increased only moderately between the survey dates, survey respondents reported that their HIV information sources involving inter-personal communication (schools, relatives/friends, work places and churches) increased considerably between 1994 and 2001.

HIV Prevention Services

In this review, STI treatment, blood safety, condom programming, VCT, and PMTCT were considered relevant HIV prevention services.

STI treatment services have been widely available in Zimbabwe since the late 1980s and incorporate counseling provided to patients on sexual behavior. The peak of STI episodes treated occurred in 1991 with 1.24 million STI episodes seen in health facilities (see Table 1) [12, 15]. The available data on STI prevalence suggest a marked reduction in Chancroid—previously the most common source of genital ulcers—between 1989 and 1996, and a further, more modest reduction up to 2005 [12, 15]. Screening of blood donations for HIV infection and other health service safety procedures were introduced in Zimbabwe in the mid-1980s; no changes were made in these services subsequently that could plausibly have contributed to the reduction in HIV risk seen nationally after 1999.

Condom distribution and promotion activities increased considerably from the late 1980s (Table 1) and continued to rise throughout the period of risk reduction [11]. Consistently-defined indicators for condom use have only been used in national surveys since 1999. DHS data [3] and data from Manicaland [2, 3] do not show significant increases in condom use after 1999. The relatively high levels of condom use with non-regular partners reported in the 1999 DHS suggest that there must have been considerable increases in use during the 1990s. The increases in sales of socially marketed condoms since the late 1990s—while not reflected in increased use according to DHS and other survey data [2, 3]—may suggest higher levels of commitment to protective behavior (and, as was noted in several key informant interviews and FGDs, condoms were usually not promoted in the often highly “sexy” manner as occurred in some neighboring countries such as Botswana, but generally as a strictly “protective” public health intervention.) Data from eastern Zimbabwe suggest relatively high levels of consistency in condom use for casual sex [2, 3].

The exact coverage of programs targeted to sex workers could not be established because sex work is illegal and reliable estimates of the number of women practicing sex work nationally are not available. DHS data suggest that condom use for paid sex was already high in 1999 and declined slightly by 2005/06 [6], while the number of men paying for sex decreased over the same period [2, 3]. It is plausible that high condom use in sex work made a moderate contribution to the risk reduction, but, given that Zimbabwe’s adult HIV prevalence appears to have peaked at above 25% in the general population, it seems unlikely that condom use in the relatively small group of sex workers and their clients was a major contributor to risk reduction [2].

By 2005, 25.8% of women and 18.6% of men, aged 15–49 years, reported ever having been tested for HIV [6]. In 2006, an estimated 30.4% of pregnant HIV positive women received voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) through the prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) program (Ministry of Health and Child Welfare/Zimbabwe 2007). However, VCT and PMTCT services were not widely available until after 2002 so it seems unlikely that these services contributed to the reduction in HIV risk that is estimated to have mainly occurred between 1999 and 2004 [5].

Discussion

HIV prevalence declined in Zimbabwe by almost 50% from its peak in the late 1990s [3]. The timing and scale of this decline are unique in southern Africa, and previous research using mathematical modeling and survey data suggest that it resulted primarily from reductions in casual (including commercial) sexual relationships during the late 1990s and early 2000s period, following earlier increases in condom use within these types of partnerships [3]. The findings from the current study contribute to an understanding as to the likely causes of these changes in behavior by documenting the evolution of the programmatic response to HIV/AIDS, over the course of the epidemic, and by describing local people’s (from across a wide range of socio-economic, educational and professional backgrounds) own perceptions as to the timing and nature of behavioral changes that have occurred and the contributions of HIV prevention programs and underlying socio-economic and socio-cultural factors.

The focus group participants and key informants painted a picture of progressive changes in sexual behavior commencing in the late 1990s, which is consistent with that seen in the survey data. They suggested that the reduction in multiple sexual partnerships and related changes in social norms stemmed from a combination of rising awareness of the dangers of HIV infection, due to very high AIDS mortality—and probably also in response to some HIV education and prevention programs, which were also intensified around the late 1990s—as well as the rising poverty due to the economic collapse that began at roughly the same time (though only reached grave proportions somewhat later). However, some specific populations (e.g., male gold and diamond panners) continued to engage in risky behavior, and study participants did not consistently refer to specific programs or messages that may have persuaded them to alter their behavior.

One of the main limitations of this study is its reliance on participants’ recollection of events and circumstances that had occurred up to 15 years previously. However, the structured approach to the FGDs, whereby participants were first requested to discuss more general events that had occurred during both of the previous time periods to assist them in remembering the patterns of behavior that had been prevalent during those periods, appeared to work well and may have helped to reduce recall bias. Since data regarding the actual timing of the introduction of specific HIV interventions was available to the researchers, it was possible to assess the accuracy of participants’ perceptions of the timing of programs launched during specific periods. Although some participants erroneously backdated program activities to periods when interventions were not yet available (e.g., VCT in the early 1990s), these appeared to be exceptions, which suggests that participants were largely able to distinguish between the three time periods. Nonetheless, the perceptions regarding the role of the economic decline during the early 2000s remain difficult to interpret precisely, due to the overwhelming preoccupation with the economic crisis that existed at the time the FGDs were actually conducted (late 2007). A common problem with qualitative data is its uncertain generalizability. The current study included a relatively robust sample size and a rough comparison of the composition of the sample with socio-demographic characteristics from the national 2005/06 Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey suggests that our attempt to recruit a fairly representative cross section of Zimbabwe’s population was successful.

Where comparison of data from the current study with data from national surveys and other independent sources was possible (e.g., regarding overall trends in sexual behavior), a considerable degree of external consistency was observed. Furthermore, the information provided by the focus group participants concerning the patterns and determinants of behavior at different time periods is broadly in agreement with contemporaneous studies. For example, the earlier pattern of widespread multiple sexual partnerships (with condoms used mainly only for family planning purposes) was noted in several studies carried out at the time [16-20] and was attributed to widespread laborrelated spousal separation and other consequences of the intersection between traditional culture and colonialism [21-24]. Similarly, studies conducted around 1990 recorded limited knowledge about HIV and AIDS [25, 26]. By the mid-1990s, there was evidence of condom use within commercial and casual partnerships [27] and of the possible beginnings of reductions in risk behavior [28].

The content of HIV prevention messages show only a partial fit with the observed behavioral changes in each period. Churches, NGOs, youth projects and the education sector promoted abstinence and delayed sexual debut, but only modest changes in such behavior could be observed. While there is clear evidence for partner reduction [2, 3], a 2005 review of over 100 IEC materials and tools suggests that partner reduction or fidelity was not a central priority and was only included in the context of broader “ABC” campaigns (though there is evidence from many of the FGDs and key informant interviews that the “B” part of ABC was “heard” by many community members). Direct program impact is apparent in the area of condom programming, as the high levels of condom use with non-regular partners would not have been achieved without consistent condom supplies and demand creation in the areas of public sector distribution and social marketing.

The behavioral and normative changes described in this study should be viewed as encouragement to further promote such positive changes in Zimbabwe and else-where in the southern African region. However, the available evidence suggests that a variety of somewhat unique factors may have worked in combination to bring about the reduction in risk behavior and consequent HIV decline in Zimbabwe. These include the extremely high level of AIDS mortality since the mid to late 1990s, when treatment was still largely unavailable, and the drastic reductions in income levels. Many focus group participants remembered some program activities on HIV–AIDS, particularly since the late 1990s. Furthermore, there was reasonably good correspondence between these recollections and the timing of introduction of programs as revealed by the historical mapping process (e.g., the early schools programs and the introduction of the District AIDS Action Committees) and some participants reflected that the increased information received through the mass media and interpersonal communication sources, along with popular influences by cultural icons such as Oliver Mtukudzi, probably contributed to safer behaviors. How-ever, most participants were not able to pinpoint specific prevention programs that had been critical in triggering widespread changes in behavior.

A more detailed description and analysis of the nature and timing of the introduction and scale-up of different programs, along with a critical review of current data on the effectiveness of the different prevention approaches that were implemented, would shed further light on the potential contributions of these programs to behavior change and HIV decline in Zimbabwe. In addition, various factors which we were not able to investigate here, such as differences in the timing of the onset of other southern African epidemics and differences in culture, marriage patterns and educational levels, should also be considered in establishing the reasons for the apparently earlier and more rapid changes in behavior observed in Zimbabwe compared to neighboring countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants in focus groups discussions across Zimbabwe for their invaluable contributions. We are also grateful to the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare (MOHCW) and to the National AIDS Council (NAC) for convening meetings and—through District AIDS Coordinators—helping to organize focus groups. We thank the providers of various forms of data such as evaluations, reports and others documentation, in particular MOHCW AIDS/TB Unit, NAC, SAfAIDS, Hazel Chinake in the Swedish International Development Agency, Karin Hatzold, Noah Tarubere-kera and Kumbirai Chatora in PSI/Zimbabwe, Sunday Manyenya in UNFPA and others. We also thank Kevin Kelly, Leonard Maveneka, Barnet Nyathi, Denford Madhina, Fatima Mhuriro, Felix Tarwireyi and Charlie Davies for the ground work done during programmatic review processes conducted before this study. We also acknowledge the important contributions of participants in the national stakeholders’ meeting held in Harare in May 2008. When conceptualizing this study, we benefited from inputs from other members of the Steering Group for this research including Kwame Ampomah, Stacey Greby, Dan Rosen, Roeland Monasch, and Helen Jackson. We would like to thank UNFPA Zimbabwe for financial and logistical support, and we thank Godfrey Woelk, Jim Shelton and Ann Swidler for their valuable assistance and comments.

Contributor Information

Backson Muchini, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Clemens Benedikt, Zimbabwe Country Office, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Harare, Zimbabwe.

Simon Gregson, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College London, London, UK; Biomedical Research and Training Institute, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Exnevia Gomo, Department of Medicine, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Rekopantswe Mate, Department of Sociology, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Owen Mugurungi, AIDS/TB Unit, Ministry of Health and Child Welfare, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Tapuwa Magure, National AIDS Council, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Bruce Campbell, Zimbabwe Country Office, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Harare, Zimbabwe.

Karl Dehne, Zimbabwe Country Office, United Nations Program on AIDS (UNAIDS), Harare, Zimbabwe.

Daniel Halperin, Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS . Evidence for HIV decline in Zimbabwe: a comprehensive review of the epidemiological data. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregson S, et al. HIV decline due to reductions in risky sex in Zimbabwe? Evidence from a comprehensive epidemiological review. Int J Epidemiol. 2010 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq055. doi: 10.1093/ije. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith J, et al. Changing patterns of adult mortality as the HIV epidemic matures in Manicaland, eastern Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl):S81–6. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000299414.60022.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallett TB, et al. Is there evidence for behaviour change affecting the course of the HIV epidemic in Zimbabwe? A new mathematical modelling approach. Epidemics. 2009;1(2):108–17. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimbabwe Central Statistical Office . Zimbabwe demographic and health survey, 2005–2006. Zimbabwe Central Statistical Office and Macro International; Harare: 2007. p. 298. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Population Services International . Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices on HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe survey reports, 1997–2007. University of Zimbabwe; Harare: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregson S, et al. HIV decline associated with behaviour change in eastern Zimbabwe. Science. 2006;311:664–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1121054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard R. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.SAfAIDS and Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare . Annotated bibliography of research on STIs/HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe. SAfAIDS; Harare: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimbabwe National AIDS Council and UNFPA . Comprehensive review of behavioural change as a means of preventing sexual transmission of HIV. UNFPA; Harare: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyathi BB, Madhina D. Review of the Zimbabwe national sexually transmitted infections programme. Harare: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimbabwe Central Statistical Office . Zimbabwe demographic and health survey, 1994. Zimbabwe Central Statistical Office; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare et al. The Zimbabwe young adult survey 2001–2002. Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Harare, Zimbabwe: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decosas J, Padian NS. The profile and context of the epidemics of sexually transmitted infections including HIV in Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(Suppl 1):40–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson D, Msimanga S, Greenspan R. Knowledge about AIDS and self-reported sexual behaviour among adults in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 1988;34(5):95–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson D, Mutero C, Lavelle S. Sex worker-client sex behaviour and condom use in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 1989;1:269–80. doi: 10.1080/09540128908253032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piotrow PT, et al. Changing men’s attitudes and behaviour: the Zimbabwe male motivation project. Stud Fam Plann. 1992;23(6):365–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mbizvo MT, Adamchak DJ. Condom use and acceptance: a survey of male Zimbabweans. Cent Afr Med J. 1989;35(10):519–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassett MT, et al. Sexual behaviour and risk factors for HIV infection in a group of male factory workers who donated blood in Harare, Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:556–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassett MT, Mhloyi M. Women and AIDS in Zimbabwe: the making of an epidemic. Int J Health Serv. 1991;21(1):143–56. doi: 10.2190/N0NJ-FKXB-CT25-PA09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutambirwa J. Aspects of sexual behaviour in Zimbabwe. In: Dyson T, editor. Aspects of sexual behaviour in local cultures and the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases including HIV. Ordina; Liege: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potts DH, Mutambirwa CC. Rural-urban linkages in contemporary Harare: why migrants need their land. J South Afr Stud. 1990;16(4):177–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourdillon MFC. Where are the ancestors? Changing culture in Zimbabwe. University of Zimbabwe; Harare: 1993. p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson D, et al. Knowledge about AIDS among Zimbabwean teacher-trainees before and during the public health campaign. Cent Afr J Med. 1989;35(1):306–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson D, et al. A pilot study for an HIV prevention programme among commercial sex workers in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(5):609–18. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90097-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mbizvo MT, et al. Condom use and the risk of HIV infection: who is being protected? Cent Afr J Med. 1994;40(11):294–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregson S, et al. Is there evidence for behaviour change in response to AIDS in rural Zimbabwe? Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(3):321–30. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]