Abstract

Background

High-deductible health plans (HDHPs) are an increasingly common strategy to contain health care costs. Individuals with chronic conditions are at particular risk for increased out-of-pocket costs in HDHPs and resulting cost-related underuse of essential health care.

Objective

To evaluate whether families with chronic conditions in HDHPs have higher rates of delayed or forgone care due to cost, compared with those in traditional health insurance plans.

Design

This mail and phone survey used multiple logistic regression to compare family-level rates of reporting delayed/forgone care in HDHPs vs. traditional plans.

Participants

We selected families with children that had at least one member with a chronic condition. Families had employer-sponsored insurance in a Massachusetts health plan and >12 months of enrollment in an HDHP or a traditional plan.

Main Measures

The primary outcome was report of any delayed or forgone care due to cost (acute care, emergency department visits, chronic care, checkups, or tests) for adults or children during the prior 12 months.

Results

Respondents included 208 families in HDHPs and 370 in traditional plans. Membership in an HDHP and lower income were each independently associated with higher probability of delayed/forgone care due to cost. For adult family members, the predicted probability of delayed/forgone care due to cost was higher in HDHPs than in traditional plans [40.0% vs 15.1% among families with incomes <400% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and 16.0% vs 4.8% among those with incomes ≥400% FPL]. Similar associations were observed for children.

Conclusions

Among families with chronic conditions, reporting of delayed/forgone care due to cost is higher for both adults and children in HDHPs than in traditional plans. Families with lower incomes are also at higher risk for delayed/forgone care.

KEY WORDS: health insurance, deductible, cost sharing, utilization, health policy

INTRODUCTION

As health care costs have escalated in recent years, families have faced increased levels of cost-sharing in commercial health insurance plans.1 High-deductible health plans (HDHPs), which have annual deductibles that are often more than $2,000 per family, are an increasingly common approach. These plans are viewed as a strategy to contain costs and provide affordable coverage, and they are likely to be offered in the Health Insurance Exchanges proposed as part of national health care reform.2

Concerns exist that the increased cost-sharing in HDHPs will lead to underuse of needed health care services, particularly by patients with chronic conditions.3,4 Surveys of adult HDHP enrollees have documented greater likelihood of reporting unmet health care needs due to cost compared to those in traditional plans,5 particularly for those with chronic conditions and lower incomes.6 Scant information is available on how HDHPs influence health care use for families, particularly those that include adults or children with chronic conditions. Increased out-of-pocket costs of a chronically ill family member could strain family budgets7 and lead to cost-related underuse of needed health care. Our objective was to evaluate whether HDHPs are associated with higher rates of delayed or forgone care due to cost (DFCC) for adults and children in families with chronic conditions, compared with traditional plans.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of families with chronic conditions in HDHPs and traditional plans. The study population included families with insurance through Massachusetts employers from Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, a large non-profit New England health plan. We included families with at least one child ≤18 years old that had been continuously enrolled for at least the prior 12 months. We selected all eligible HDHP families and a random sample of twice as many traditional plan families. To identify families likely to have chronic conditions, we first used claims data to identify family members with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) code for a chronic condition.8 We then used survey questions described below to verify that families had an adult with a chronic condition or a child with a special health care need.

Health Plan Structure

The HDHPs in this study had family deductibles of $1,000 to $6,000 per year. Services subject to the deductible included emergency department (ED) visits, diagnostic tests, hospitalizations, and physical therapy. In most plans, office visits were exempt from the deductible and subject to a $20 co-payment; prescription drugs were also subject to co-payments. Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs) (employer-funded tax-exempt accounts used for health care expenses) were available in the majority of HDHPs but infrequently offered by employers. In the minority of HDHPs that were eligible for Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) (similar accounts in HDHPs with family deductibles > $2,200 that could be funded by employers or employees), non-preventive office visits and prescription drugs were also subject to the deductible. In all HDHPs, preventive services were covered at no cost.

The traditional plans in our study were those without a deductible. These plans had co-payments for office visits (mean co-payment = $16), prescription drugs, and ED visits; full coverage for preventive care and diagnostic tests; and limited cost-sharing for hospitalizations.

Data Collection

We surveyed parents from eligible families by phone or mail between April and December 2008. To verify families with chronic conditions and special health care needs, we used the Children with Special Health Care Needs Screener for children,9 and asked whether any adults in the family had a “health condition that has lasted or is expected to last a year or longer, may limit what one can do, and may require ongoing care, such as diabetes, high cholesterol, or asthma.”10 In addition to the measures of DFCC described below, the survey asked about demographics; whether families had had a choice of plans;11 and whether they had an account to pay for health care expenses such as an HSA, HRA, Flexible Savings Account, or Medical Savings Account.

We obtained computerized data from Harvard Pilgrim on family demographics and enrollment history, and whether the family’s plan was obtained through an Association (a broker or trade organization that negotiates contracts with health insurers for employers with <10 employees). The study was approved by the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all survey participants.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome variable was report of DFCC for adult or child family members in the prior 12 months. Subjects were asked whether they or a family member (1) was sick with an acute illness (defined as “when the symptoms do not last for a long period of time, like the flu or an injury”) and delayed going to the doctor’s office or did not go at all; (2) had considered going to the ED but delayed going or did not go at all; (3) delayed going to the doctor or did not go at all for a chronic condition (as defined above); (4) delayed going to get a checkup or did not go at all; or (5) delayed going to get a test or procedure or did not go at all. Subjects answering affirmatively were asked whether the delayed or forgone care was due partly or entirely to cost, and whether the family member was a child or an adult. The denominator for these measures was all study families.

Analyses

All analyses were done at the family level and included only families who reported having a child with a special health care need or an adult with a chronic condition. Chi-square and t-tests were used for bivariate analyses.

We used separate multivariate logistic regression models to determine the odds of reporting any DFCC for adults and for children in HDHPs relative to those in traditional plans. Models included covariates associated with the outcome in bivariate analyses at p < 0.20, as well as the following covariates included a priori: number of adults and children in the family, whether an adult had a chronic condition, and whether a child had a special health care need. We used these models to calculate predicted probabilities of any DFCC for adults and for children by setting covariates to their mean or modal values, and then calculating predicted probabilities with study group set to HDHP or traditional plan, and income set to <400% or ≥400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

We conducted sensitivity analyses using propensity scores to address selection effects that may be present if families chose HDHPs for reasons that may be associated with health care utilization, such as low income, an employer-funded account, or having few anticipated health care needs. The propensity score represents the probability that a subject will be in the treatment group based on baseline characteristics, offering the advantage of incorporating multiple covariates into a single measure.12 We first calculated each family’s propensity to enroll in an HDHP using a logistic regression model that included the number of adults and children; subscriber age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity; mean age of children; income; presence of an adult with a chronic condition or a child with a special health care need; having a choice of plans; and whether the plan had an account, drug coverage, or was obtained through an Association. We then used the propensity score in two ways: as the single covariate in a model to predict DFCC, or as the weighting estimator in an inverse-probability-of-treatment-weighted multivariate model.13

RESULTS

We selected all of the 640 eligible HDHP families and 1,280 of the 5,921 eligible traditional plan families. Of these 1,920 families whom we attempted to contact, 126 were found to be ineligible and were excluded. We completed surveys with 820 families for a response rate of 46%. Non-respondent families were not significantly different from respondent families in terms of family size, subscriber and child age, presence of chronic conditions based on ICD-9 codes, or ED and hospital use in the prior year, but were significantly more likely to be in traditional plans and to have male subscribers. After excluding families who did not have an adult with a chronic condition or a child with a special health care need, the final study sample included 208 families in HDHPs and 370 in traditional plans.

HDHP and traditional plan families were similar in most characteristics (Table 1). HDHP families had subscribers who were slightly older and more likely to be male, and had older children. They were more likely to have enrolled through an Association and less likely to have an account for health care expenses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Families in High-Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs) Compared to Traditional Plans

| HDHP* (n = 208) | Traditional plan (n = 370) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number of adults in the family | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.25 |

| Mean number of children in the family | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.16 |

| Mean subscriber age (years) | 46.5 | 43.4 | < 0.001 |

| Mean age of children in the family (years) | 10.7 | 9.8 | 0.02 |

| Male subscriber | 76% | 65% | 0.01 |

| Income | |||

| <200% FPL† | 9% | 9% | 0.16 |

| 200–299% FPL | 20% | 14% | |

| 300–399% FPL | 21% | 18% | |

| ≥400% FPL | 50% | 59% | |

| White, non-Hispanic parent | 93% | 88% | 0.07 |

| Parent without college degree | 31% | 32% | 0.83 |

| Child with special health care need | 65% | 65% | 0.95 |

| Adult with chronic condition | 72% | 72% | 0.97 |

| No choice of plans | 25% | 20% | 0.11 |

| Mean number of months enrolled | 41.8 | 42.9 | 0.48 |

| Coverage through an Association | 66% | 42% | < 0.001 |

| Has account for health care expenses | 22% | 33% | 0.006 |

*HDHP = High-deductible health plan

†FPL = Federal poverty level

Bivariate Analyses

In bivariate analyses, families in HDHPs were significantly more likely than traditional plan families to report DFCC for adult members for acute visits, chronic care visits, checkups, and tests, although not for ED visits (Table 2). Overall, HDHP families were significantly more likely than traditional plan families to report any DFCC for adults.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Comparison of Reporting Delayed/Forgone Care due to Cost for Different Types of Services among Adults and Children Enrolled in High-Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs) Versus Traditional Plans

| Families reporting delayed/forgone care due to cost | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For an adult | For a child | |||||

| HDHP* (n = 205) | Traditional Plan (n = 365) | p value | HDHP (n = 202) | Traditional Plan (n = 363) | p value | |

| Acute visits | 8.2% | 3.8% | 0.025 | 1.9% | 0.5% | 0.116 |

| ED† visits | 5.3% | 3.5% | 0.303 | 4.4% | 1.6% | 0.049 |

| Chronic care visits | 9.3% | 2.7% | 0.001 | 1.5% | 0.3% | 0.100 |

| Checkups | 9.3% | 3.3% | 0.002 | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.677 |

| Tests | 13.2% | 1.4% | <0.001 | 1.0% | 0.8% | 0.843 |

| Any of the above | 26.3% | 9.9% | <0.001 | 8.4% | 3.3% | 0.008 |

*HDHP = High-deductible health plan

†ED = Emergency department

Families in HDHPs were significantly more likely than those in traditional plans to report delayed or forgone ED visits due to cost for children (Table 2). We found no significant differences between HDHP and traditional plan families for DFCC for children for other types of services (acute care, chronic care, checkup visits, or tests). However, when examined in aggregate, HDHP families were significantly more likely than traditional plan families to report any DFCC for a child.

Multivariate Analyses

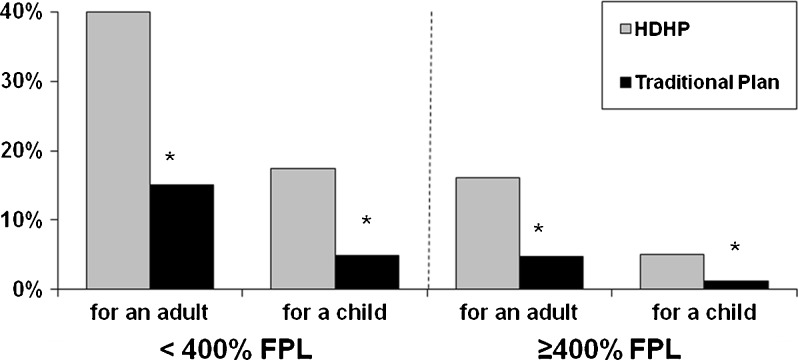

Families in HDHPs had greater odds of reporting DFCC for an adult compared to families in traditional plans (Table 3). Having an income <400% FPL and a subscriber without a college degree were significantly associated with greater odds of DFCC. Based on this model, among families with incomes <400% FPL, the predicted probability of DFCC for an adult was 40.0% in families with HDHPs but only 15.1% for families with traditional plans (Fig. 1). Among families with incomes ≥400% FPL, the predicted probability of any DFCC for an adult was 16.0% in HDHPs and 4.8% in traditional plans.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Reporting any Delayed or Forgone Care due to Cost in the Family in the Prior 12 Months

| For an adult OR (95% CI) (n = 434) | For a child OR (95% CI) (n = 431) | |

|---|---|---|

| HDHP* (vs traditional plan) | 3.79 (2.08–6.90) | 4.40 (1.67–11.61) |

| Mean number of adults in the family | 1.50 (0.89–2.51) | 0.41 (0.13–1.31) |

| Mean number of children in the family | 1.06 (0.74–1.52) | 1.74 (1.01–2.99) |

| Mean age of children in the family (years) | 0.94 (0.87–1.01) | 0.97 (0.86–1.08) |

| Income <400% FPL† | 3.54 (1.82–6.86) | 4.17 (1.27–13.71) |

| Parent without college degree | 2.06 (1.11–3.84) | 1.51 (0.57–3.96) |

| Child with special health care need | 1.77 (0.91–3.45) | 2.12 (0.66–6.75) |

| Adult with chronic condition | 1.99 (0.94–4.21) | 1.11 (0.40–3.11) |

| Coverage through an Association | 1.27 (0.66–2.47) | 1.04 (0.38–2.87) |

| Has account for health care expenses | 1.37 (0.63–3.00) | 0.68 (0.17–2.79) |

| Mean number of months enrolled | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) |

Statistically significant (p < 0.05) findings are in bold

*HDHP = High-deductible health plan

†FPL = Federal poverty level

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of reporting any delayed/forgone care due to cost among adults and children enrolled in high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) versus traditional plans. *p < 0.05.

We also found that the odds of DFCC for children were greater in HDHP families than in traditional plan families (Table 3). Having an income <400% FPL and having more children in the family were also significantly associated with greater odds of DFCC for a child. Based on this model, among families with incomes <400% FPL, the predicted probability of reporting any DFCC for a child was 17.4% for HDHP families and 4.9% for traditional plan families (Fig. 1). Among families with incomes ≥400% FPL, the predicted probability of any DFCC for a child was 5.1% for HDHP families compared to 1.2% for traditional plan families.

Sensitivity analyses produced similar results. The odds of DFCC for adults were greater in HDHP families compared to traditional plan families when we used propensity score adjustment (OR 3.33, 95% CI 1.94–5.73) and propensity score weighting (OR 3.87, 95% CI 2.02–7.38). This was also the case for DFCC for children (propensity score adjusted OR 3.42, 95% CI 1.39–8.45, and propensity score weighted OR 5.05, 95% CI 1.63–15.67). As another sensitivity test, we restricted analyses to families without a choice of plans. While sample sizes were small, the trends supported an association between HDHP enrollment and DFCC for adults (OR 2.71, 95% CI 0.42–17.52) and children (OR 19.31, 95% CI 0.82–452.14).

To examine intrafamilial effects of HDHPs, we examined DFCC among families in which only an adult had a chronic condition, and found that HDHP enrollment was associated with increased odds of DFCC for children (OR 18.02, 95% CI 1.20–270.29) but not for adults (OR 1.95, 95% CI 0.65–5.84). Conversely, among families in which only a child had a chronic condition, HDHP enrollment was associated with increased odds of DFCC for adults (OR 12.69, 95% CI 2.19–73.44) but not children (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.17–3.54).

We did not find significant differences in DFCC among HDHP families with higher ($3,000–$6,000) vs. lower ($1,000–$2,200) family deductibles. We also did not find significant effect modification between income and HDHP enrollment or deductible amount. Smaller sample sizes may have given these analyses limited power, however.

DISCUSSION

This study is one of the first to focus on families with chronic conditions in HDHPs. Because many people with chronic conditions require continuing care, these individuals and their families may face substantial out-of-pocket health care costs and be at particular risk for DFCC. We observed that the odds of reporting DFCC were three to four times greater for adults and children in HDHP families compared to traditional plan families. Although the prevalence of DFCC was lower overall for children relative to adults, both children and adults in HDHPs had significantly higher probability of DFCC compared to those in traditional plans. Our findings suggest an increased risk for DFCC in HDHPs for healthy children and adults in families with a chronically ill member, but not for the members with chronic conditions, raising the question of whether families facing out-of-pocket cost pressures in HDHPs are prioritizing the care of chronically ill members over healthier members and making optimizing choices within the family.

The probability of DFCC was highest for lower-income children and adults in HDHPs. Our findings are consistent with studies showing that increased cost-sharing affects higher as well as lower-income enrollees.14 Other studies have found that utilization differences between HDHP and traditional plan enrollees were greater among those with lower incomes.15

The clinical significance of these findings depends upon whether adults and children are delaying/forgoing care that is essential or non-essential. Our study was not able to assess this issue. Write-in responses to questions about which services were delayed or forgone suggested a wide range of clinical significance, from a sleep study or allergy test to an “MRI for melanoma.” Other studies suggest that patients reduce their use of both essential and non-essential services when faced with increased cost-sharing.15,16

Preserving use of necessary services within HDHPs remains a concern, particularly for high-risk populations such as those with chronic conditions and low incomes. Providers may not be aware when patients face substantial deductible costs for services they recommend, or that patients are delaying or forgoing these services in response.17,18 Heightened awareness and discussion about out-of-pockets faced by patients and their families in HDHPs might allow providers to dissuade patients from forgoing essential services and to help find lower-cost alternatives.

Policy Implications

Our findings have important policy implications as HDHPs become an increasingly prevalent strategy to provide affordable coverage.19 Health Insurance Exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will likely include HDHPs. In Massachusetts, HDHPs have had the greatest uptake among unsubsidized Exchange plan offerings.20 Enrollment in HDHPs is likely to increase when the ACA’s proposed individual coverage mandate is enacted in 2014, as families seek low-cost coverage options.

Our findings suggest that lower-income families in HDHPs have increased rates of cost-related delayed and forgone care. The Massachusetts Health Insurance Exchange excludes plans with high deductibles from its subsidized offerings for individuals with incomes <300% FPL. The ACA does not have such a restriction, but the risk of cost-related underuse of care for lower-income families may be mitigated by income-based cost-sharing subsidies in Exchanges. The intrafamilial effects of cost-sharing suggested by our study highlight the need to account for family-level costs when developing affordability thresholds, deductible limits, and out-of-pocket maximums. Policy makers will need to consider spillover effects on utilization and costs within families when designing coverage and cost-sharing policies for adult, pediatric, preventive, and chronic disease services.

Policies that selectively remove cost-sharing for high-value services may be a way to preserve use of important services in HDHPs.21–24 The ACA prohibits insurance plans from requiring cost-sharing for recommended preventive services.25 However, HDHP enrollees may underuse these services in HDHPs despite exemption from the deductible,26 in part because of difficulty understanding which services are and are not exempt from cost-sharing.27 HDHP enrollees might benefit from development of more sophisticated tools to encourage the use of high-value services, especially those exempt from the deductible.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Because health plan enrollment is not random, selection effects may be present. If families with limited financial resources are more likely to enroll in HDHPs because of lower premiums, they may at greater risk for DFCC. Our study’s ability to control for a range of socioeconomic, employer, and plan characteristics and our propensity score sensitivity analyses provide reassurance that our findings account for important observed confounders. However, because families’ enrollment in HDHPs may be affected by other unmeasured factors, the relationships observed between HDHP enrollment and DFCC should be interpreted as associations rather than causal relationships.

Our findings should also be interpreted in light of policies in place in Massachusetts at the time of the study, including an individual insurance mandate, which may limit current generalizability to other states but will make our study more broadly informative as similar policies become enacted as part of national health reform. Because only 11% of families in our study were in HSA-eligible HDHPs, our findings may not generalize to families with these types of HDHPs, which subject all but preventive services to the deductible and may have greater potential for inducing cost-related changes in utilization. However, the presence of an employer-funded account could reduce the likelihood of cost-related reductions in utilization.5 Our study was not able to distinguish between account types or whether an account was funded by an employer or employee.

Our survey’s response rate was comparable to that of recent surveys on similar topics,28,29 and we found that non-responders were similar to responders. We are unable to answer the question of how these HDHP families would have fared if they were uninsured, which would likely place them at greater risk of DFCC.29,30

CONCLUSION

This study found that both adults and children are more likely to experience DFCC in families with chronic conditions in HDHPs compared to traditional plans. Having lower income also increases the risk of DFCC. As health care reform efforts move forward, policymakers, payers, clinicians, and families will need to balance preserving use of needed care in HDHPs while containing costs.

Contributors

The authors thank Christopher Forrest, Bruce Landon, and Carol Cosenza for guidance in the design of the survey instrument; Christopher Forrest and Linda Dunbar for making the Chronic Condition Checklist available and assisting with its use; Irina Miroshnik for help with data collection and interpretation; and the team of research assistants for their help in conducting the survey.

Funding

This study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Changes in Health Care Financing and Organization (HCFO) Initiative. Additional support for the survey was provided by the Center for Child Health Care Studies, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School. Dr Galbraith’s effort was supported in part by a K23 Mentored Career Development Award from NICHD (HD052742). Drs. Soumerai and Ross-Degnan are investigators in the HMO Research Network Center for Education and Research in Therapeutics and are supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no. U18HS010391). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Prior Presentations

An abstract based on this research was presented at the 2010 Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting in Vancouver, British Columbia, and at the 2010 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Boston, MA, as a poster.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Galbraith has received support for a separate research project from the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation through a Faculty Grant.

References

- 1.Claxton G, DiJulio B, Whitmore H, et al. Job-based health insurance: costs climb at a moderate pace. Health Aff. 2009;28(6):w1002–1012. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation. Summary of New Health Reform Law. 2010; http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/8061.pdf. Accessed Dec 13, 2011.

- 3.Lee TH, Zapert K. Do high-deductible health plans threaten quality of care? N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1202–1204. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Child Health Financing High-deductible health plans and the new risks of consumer-driven health insurance products. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):622–626. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen R. Impact of Type of Insurance Plan on Access and Utilization of Health Care Services for Adults Aged 18–64 Years With Private Health Insurance: United States, 2007–2008: NCHS Data Brief No. 28;2010. [PubMed]

- 6.Fronstin P, Collins SR. Findings from the 2007 EBRI/Commonwealth Fund Consumerism in Health Survey. 2008. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/usr_doc/Fronstin_consumerism_survey_2007_issue_brief_FINAL.pdf?section=4039. Accessed Dec 13, 2011.

- 7.Galbraith AA, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Rosenthal MB, Gay C, Lieu TA. Nearly half of families in high-deductible health plans whose members have chronic conditions face substantial financial burden. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):322–331. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunbar L. Alternative Methods of Identifying Children with Special Health Care Needs: Implications for Medicaid Programs: University of Maryland; 2005.

- 9.Bethell C, Read D, Stein R, Blumberg S, Wells N, Newacheck P. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr. 2002:38-48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Anderson GF. Physician, public, and policymaker perspectives on chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(4):437–442. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gawande AA, Blendon R, Brodie M, Benson JM, Levitt L, Hugick L. Does dissatisfaction with health plans stem from having no choices? Health Aff (Millwood) 1998;17(5):184–194. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.5.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braitman LE, Rosenbaum PR. Rare outcomes, common treatments: analytic strategies using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:693–695. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurth T, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, et al. Results of multivariable logistic regression, propensity matching, propensity adjustment, and propensity-based weighting under conditions of nonuniform effect. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(3):262–270. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherkin DC, Grothaus L, Wagner EH. Is magnitude of co-payment effect related to income? Using census data for health services research. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90064-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hibbard JH, Greene J, Tusler M. Does enrollment in a CDHP stimulate cost-effective utilization? Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(4):437–449. doi: 10.1177/1077558708316686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Free for All? Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander G, Casalino L, Meltzer D. Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA. 2003;290(7):953–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieu T, Solomon J, Sabin J, Kullgren J, Hinrichsen V, Galbraith A. Consumer awareness and strategies among families with high-deductible health plans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Claxton G, DiJulio B, Whitmore H, et al. Health benefits in 2010: premiums rise modestly, workers pay more toward coverage. Health Aff. 2010;29(10):1942–1950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonough JE, Rosman B, Butt M, Tucker L, Howe LK. Massachusetts health reform implementation: major progress and future challenges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(4):w285–297. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.w285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fendrick AM, Chernew ME. Value-based insurance design: a "clinically sensitive, fiscally responsible" approach to mitigate the adverse clinical effects of high-deductible consumer-directed health plans. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):890–891. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galbraith A, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai S, et al. Use of well-child visits in high-deductible health plans. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(11):833–840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe JW, Brown-Stevenson T, Downey RL, Newhouse JP. The effect of consumer-directed health plans on the use of preventive and chronic illness services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(1):113–120. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wharam JF, Galbraith AA, Kleinman KP, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Landon BE. Cancer screening before and after switching to a high-deductible health plan. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(9):647–655. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-9-200805060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Recommended Preventive Services. 2010; http://www.healthcare.gov/center/regulations/prevention/recommendations.html. Accessed Dec 13, 2011.

- 26.Beeuwkes Buntin M, Haviland AM, McDevitt R, Sood N. Healthcare spending and preventive care in high-deductible and consumer-directed health plans. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(3):222–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed M, Fung V, Price M, et al. High-deductible health insurance plans: efforts to sharpen a blunt instrument. Health Aff. 2009;28(4):1145–1154. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham PJ, Miller C, Cassil A. Living on the Edge: Health Care Expenses Strain Family Budgets. Research Brief No. 10: Center for Studying Health Systems Change; December 2008. [PubMed]

- 29.Schoen C, Collins SR, Kriss JL, Doty MM. How many are underinsured? Trends among US adults, 2003 and 2007. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(4):w298–309. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.w298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu HT, Cohen G. Financial and Health Burdens of Chronic Conditions Grow. Tracking Report No. 24. 2009. http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/1049/1049.pdf. Accessed Dec 13, 2011. [PubMed]