Abstract

Isolated from the sponge Terpios hoshinota that causes coral black disease, nakiterpiosin was the first C-nor-D-homosteroid discovered from a marine source. We provide in this account an overview of the chemistry and biology of this natural product. We also include a short history of the synthesis of C-nor-D-homosteroids and the results of some unpublished biological studies of nakiterpiosin.

Keywords: natural products, steroids, total synthesis, Hedgehog signaling, tubulin

1 Introduction

The massive coral reef damage, often referred to as coral black disease, caused by the sponge Terpios hoshinota has significant impact on marine ecology.1 Large patches of T. hoshinota killing the covered corals were first found on Guam in 1973 and later on the Ryukyu Islands in the 1980s. Searching for toxins produced by T. hoshinota, Uemura and co-workers collected 30 kilograms of these <1 millimeter thick sponges in Okinawa and reported the isolation of 0.4 milligrams of nakiterpiosin (1) and 0.1 milligrams of nakiterpiosinone (2) in 2003 (Figure 1).2 Despite the limited quantities of these compounds, they correctly determined the gross structures of these complex natural products and assigned them to the family of C-nor-D-homosteroids. They also found that both compounds inhibited the growth of P388 mouse leukemia cells with an IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration) value of 15 nM.

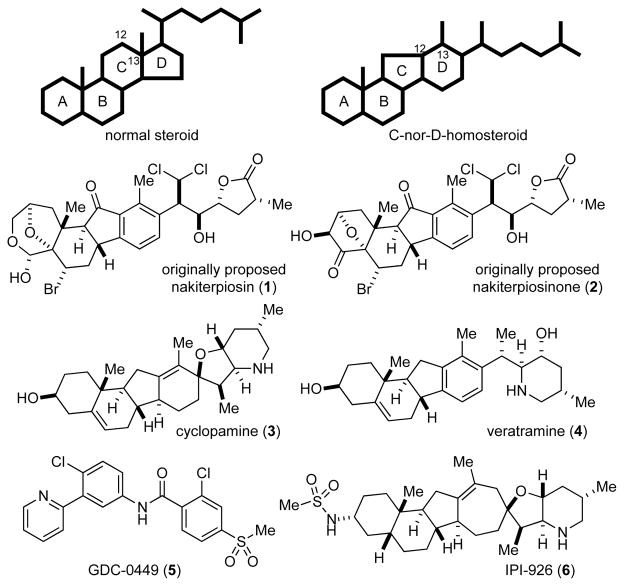

Figure 1.

The originally proposed structures of nakiterpiosin (1) and nakiterpiosinone (2), and the structures of cyclopamine (3), veratramine (4), GDC-0449 (5), and IPI-926 (6)

The C-nor-D-homosteroids are skeletally rearranged (C133C12) steroids with their C-ring contracted and D-ring expanded by one carbon. The best-known family members are cyclopamine (3) and veratramine (4) (Figure 1), which were discovered to be potent teratogens by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Poisonous Plant Research Laboratory in the 1950s during their 11-year investigations into an extraordinarily high incidence of cyclopia observed in a flock of sheep in Central Idaho.3 Binns and co-workers found that ewes grazing on corn lily (Veratrum californicum) on the 14th day of gestation would give birth to cyclopic lambs, while the ewes themselves were left unaffected. Furthermore, they found that cyclopamine (3) was responsible for the one-eyed face malformation whereas ingestion of veratramine (4) resulted in leg deformities.

After intensive structural and synthetic studies by chemists in the 1960s, not much attention was paid to these teratogenic steroidal alkaloids until genetic studies in the 1990s, when Beachy and Roelink and their co-workers found cyclopamine (3) to be the first known small molecule to inhibit Hedgehog (Hh) signaling.4 The initial observation of Hh gene function was made by Nüsslein-Volhard and Wieschaus and their co-workers in Drosophila in the 1970s.5 The name hedgehog was given because the Hh mutation in Drosophila resulted in spiky larvae. The first two discovered mammal homologues, desert hedgehog (Dhh) and Indian hedgehog (Ihh), were named for species of hedgehogs, while the third and most studied one, Sonic hedgehog (Shh), was named after the video game character Sonic the Hedgehog.

The cellular responses controlled by Hh proteins are essential for embryonic development and are frequently exploited in cancer cells to promote deviant cell growth. Smoothened (Smo) is a seven-pass transmembrane protein that functions as an essential effector molecule in the Hh signal transduction pathway. Beachy and co-workers demonstrated in 2002 that cyclopamine (3) binds directly to Smo,4c which was found to be mutated and constitutively active in 10% of basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma patients. Small molecules that suppress Hh signaling have been pursued as a new class of therapeutics for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.6 Erivedge (vismodegib or GDC-0449, 5), developed by Genentech (now Roche) and Curis, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration on January 30, 2012, for treating advanced basal cell carcinoma. The cyclopamine analogue saridegib (IPI-926, 6), developed by Infinity Pharmaceuticals, has entered phase 2 clinical testing (Figure 1).

2 Synthesis of C-nor-D-Homosteroids

The structure elucidation and the total synthesis of cyclopamine (3, also known as 11-deoxojervine) (see Figure 1), jervine (11-oxo-3), and veratramine (4) (see Figure 1) were the subjects of intense research in the 1960s. Masamune et al.7 and Johnson et al.8 reported in 1967 the first synthesis of 11-oxo-3 and 4, respectively. Masamune and co-workers had also shown previously that 3 could be obtained from 11-oxo-3 using a Wolff reduction.9 A formal synthesis of these steroidal alkaloids was later reported by Kutney et al. in 1975.10 Since the discovery of 3 as an Hh inhibitor, there has been increasing interest in developing new anticancer drugs based on its molecular scaffold.

A rapid and efficient isolation method for cyclopamine (3) was developed in 2008, giving 1.3 grams of 3 (55% of the available 3) from 1 kilogram of the dry root of corn lily.11 Infinity Pharmaceutical’s IPI-926 (6) was produced by modifying natural compound 3. A more practical synthesis of 3 was also reported by Giannis et al. in 2009.12

2.1 The Biomimetic Approaches

The biomimetic approach to the C-nor-D-homosteroid skeleton was first developed by members of a research group at Merck (Scheme 1).13 They activated the C-12 position of hecogenin as mesylate 7 or tosylhydrazone 10. While treating 7 with a base gave a mixture of rearranged products 8 and 9, thermolysis of 10 gave only 9 because of concurrent H-17 deprotonation during the C-13→C-12 migration. This method was later modified by Mitsuhashi and co-workers,14 members of a Schering-Plough research group,15 and Giannis and co-workers.12,16 In particular, Giannis and co-workers demonstrated that a combination of the Comins reagent and 4-(N,N-dimethyl-amino)pyridine effectively promoted the rearrangement of a series of steroid derivatives that failed to undergo rearrangement under other reported conditions.

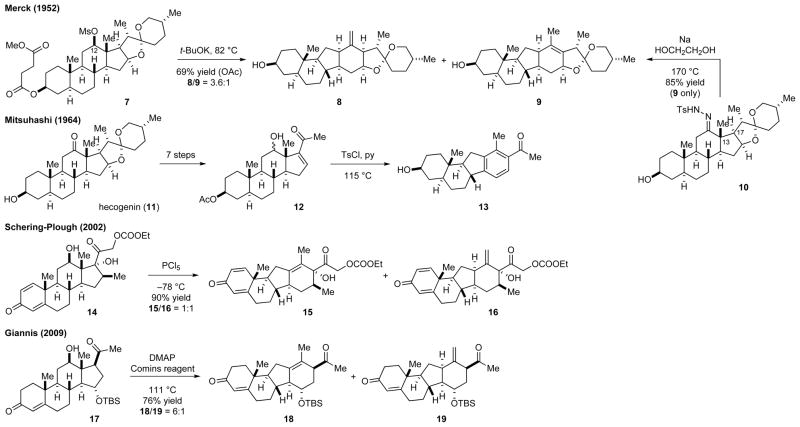

Scheme 1.

The biomimetic approaches for the synthesis of the C-nor-D-homosteroid skeleton

Ketone 13 served as the common intermediate for Masamune and Johnson in their asymmetric synthesis of 11-oxo-3 and 4. Masamune and co-workers first converted ketone 13 into a benzylic bromide and introduced the Ering of 3 using an enamine alkylation reaction.7 Johnson and co-workers introduced the side chain of veratramine (4) to ketone 13 through a Johnson–Corey–Chaykovsky epoxidation, an epoxide–aldehyde rearrangement, and a Strecker reaction.8a

2.2 The Ring-by-Ring Approaches

In addition to the semisynthesis, Johnson and co-workers also developed two linear approaches to construct the C-nor-D-homosteroid skeleton in the racemic form (Scheme 2). In their first approach,17 tetralone 20 served as the source of the C,D-rings, while the B- and A-rings were introduced sequentially by Robinson annulation, resulting in tetracyclic compound 22. The Δ11,12 olefin moiety was then introduced to provide intermediate 23. Ozonolysis of 23 followed by an aldol reaction of the resulting dialdehyde gave aldehyde 24. Subsequent deformylation and deoxygenation afforded the cyclopamine core skeleton. Kutney and co-workers used a similar ring-contraction strategy in their formal synthesis of 4.10a

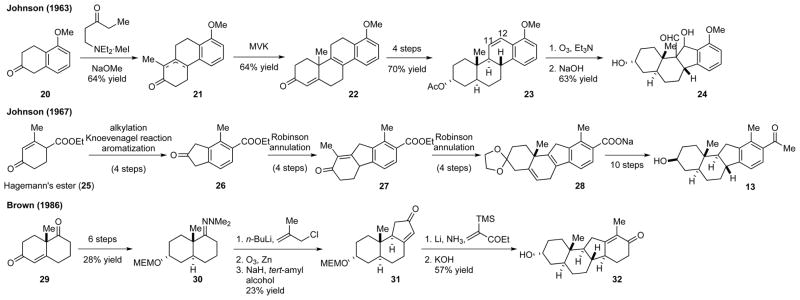

Scheme 2.

The ring-by-ring approaches for the synthesis of the C-nor-D-homosteroid skeleton

In Johnson and co-worker’s second approach,8b the Cring was introduced directly as the desired ring size. Starting from Hagemann’s ester (25), which served as the source of the D-ring, a Knoevenagel condensation was used to construct the C-ring. After decarboxylation and D-ring aromatization, the B- and A-rings were introduced stepwise by Robinson annulation to give 28 from 26. A series of reduction and aromatization reactions were then performed to deliver racemic compound 13.

In contrast to Johnson’s D- to A-ring approach, E. Brown and Lebreton devised an A- to D-ring method.18 Starting from the Wieland–Miescher ketone (29), a common source of the A,B-rings for the synthesis of steroids, the C-ring was introduced via a sequence of hydrazone allylation, ozonolysis, aldol condensation, and olefin isomerization to give tricyclic compound 31. The D-ring was assembled by a reductive alkylation of enone 31 followed by an aldol condensation.

2.3 Miscellaneous Approaches

During the synthesis of an indenone derivative, Hoornaert and co-workers found that aluminum trichloride catalyzed the dimerization of indenone 33 to form truxone 34 (Scheme 3).19 Attempts to induce the retro-dimerization of 34 by photolysis resulted in a decarbonylation through a Norrish type I cleavage to give intermediate 35. This compound underwent a photolytic, disrotatory retro-electrocyclization followed by a thermal, suprafacial 1,5-sigmatropic benzoyl shift to afford product 37 comprising a C-nor-D-homosteroid skeleton.

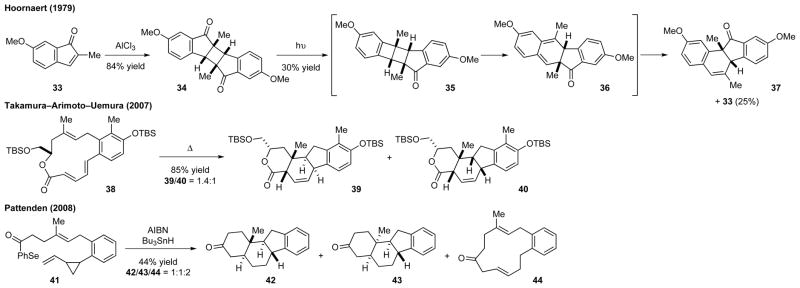

Scheme 3.

Miscellaneous approaches for the synthesis of the C-nor-D-homosteroid skeleton

Both the thermal and the Lewis acid promoted transannular Diels–Alder reactions are powerful tools for the synthesis of steroids and other natural products.20 A research team led by Takamura, Arimoto, and Uemura used this method to assemble the polycyclic skeleton of nakiterpiosin.21 Heating macrolide 38 at 160 °C gave 39 and 40 as a mixture of diastereomers in good yield.

Pattenden and co-workers reported a tandem cyclization approach for the synthesis of estrone in 2004. They later demonstrated that this strategy could also be used to generate the molecular skeleton of cyclopamine (3).22 The acyl radical generated from substrate 41 reacted with the vinylcyclopropyl moiety to form a macrocyclic radical, which underwent a double transannular cyclization and a hydrogen abstraction from tributyltin hydride to give tetracyclic compounds 42 and 43. The macrocycle 44, resembling Tamakura and co-workers’ intermediate 38, was also isolated.

3 Structural Revision of Nakiterpiosin

We started our work on the synthesis of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone in March 2007. At the onset of this project, we noticed that the C-20 and C-25 configurations of the originally proposed structures 1 and 2 were opposite to those of cyclopamine (3) and veratramine (4) (see Figure 1). In particular, the 20R configuration of 1 and 2 is less commonly seen in natural steroids. Their C-6 and C-20 configurations could not be easily rationalized based on biogenetic analysis.

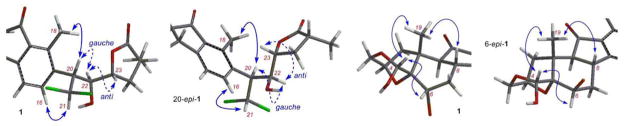

Uemura and co-workers assumed that the side chain of 1 and 2 adopted a zigzag conformation. They assigned the C-22 and C-23 configurations based on the observed 3J20,22 and 3J22,23 values and the C-20 configuration based on the observed nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) signals of H-18/H-20 and H-16/H-21.2 While a gauche H-20/H-22 and an anti H-22/H-23 relationship could be deduced, these data did not seem to provide enough support to the assignment of the C-20 and C-25 configurations. Indeed, we found that both the proposed (20R) and the opposite (20S) configured structures fitted these data well (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The configurational analysis of nakiterpiosin (1) (structures generated by AM1) (solid arrows: key NOE interactions; dashed arrows: J-based configurational analyses)

Similarly, the original assignment of the C-6 configuration is also debatable. The C-4 and C-6 configurations were assigned based on the observed H-19/H-4 and H-4/H6 NOE signals. It was proposed that the absence of the H-6/H-19 NOE signal was due to a twist-boat conformation of the C-ring according to the observed 3J6,7 values (Figure 2). However, we found that these NMR spectroscopic data could also be explained by a 6R configuration in a chair conformation. Our concern was further increased when we found that the H-6 and H-21 splitting patterns of our synthetic intermediates toward 1 were significantly different from those of the natural products. We therefore decided to study these stereochemical issues carefully by examining the NMR spectroscopic data of a series of diastereomeric synthetic fragments and concluded that the C-6, C-20, and C-25 configurations needed to be revised.

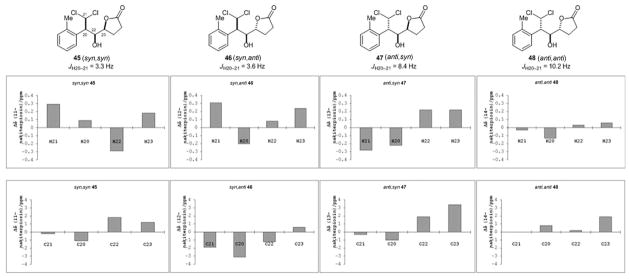

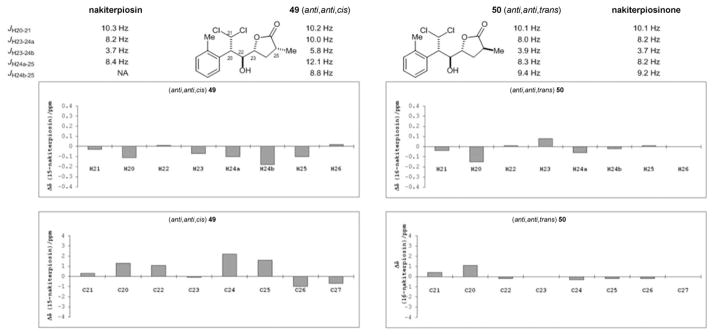

We first focused on the C-20/C-22/C-23 relative configuration and synthesized all four possible diastereomers, represented by compounds 45–48, to compare their NMR spectra with those of the natural products. We found that the 3JH,H coupling constants and 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic chemical shifts of 45 (syn,syn), 46 (syn,anti), and 47 (anti,syn) were considerably different from those of the natural products (Figure 3). In particular, the 3JH-20,H-21 values of 45 (syn,syn) and 46 (syn,anti) indicated a gauche, instead of an anti, H-20/H-21 conformation. Only 48 (anti,anti) exhibited similar 1H and 13C NMR spectra compared to those of the natural products. We therefore proposed the C-20 configuration of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone to be S.

Figure 3.

Probing the C-20/C-22/C-23 configurations of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone

We next probed the C-25 configuration by synthesizing two model substrates, compounds 49 and 50. We found that the coupling constants and the 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic chemical shifts of (25S)-50 (anti,anti,trans), but not (25R)-49 (anti,anti,cis), matched well with those of the natural products (Figure 4). In particular, the 3JH-23,H-24a, 3JH-23,H-24b, and 3JH-24a,H-25 values of 49 and those of the natural products were significantly different. We therefore concluded that the C-25 stereocenter of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone should be S-configured.

Figure 4.

Probing the C-25 configurations of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone

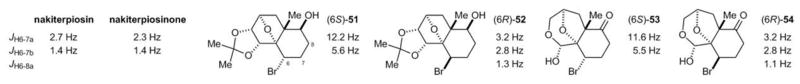

We subsequently studied the C-6 stereochemistry of the natural products and synthesized compounds 51–54. The 3JH-6,H-7 values of 51 and 53, which bear the proposed 6S configuration, were very different to those of the natural products (Figure 5). In contrast, the corresponding C-6 epimers 52 and 54 exhibited H-6 splitting patterns similar to those of the natural products. We therefore concluded that the C-6 stereocenter of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone should be R-configured.

Figure 5.

Probing the C-6 configurations of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone

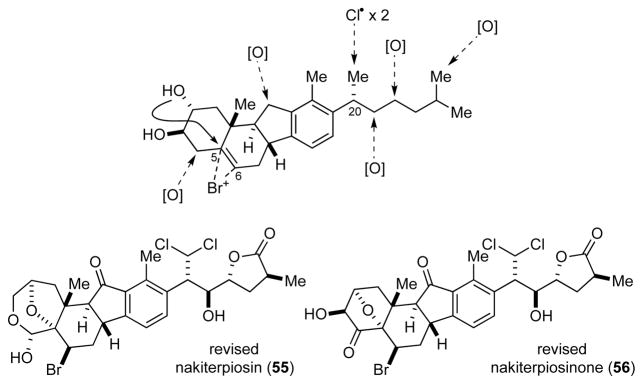

Based on these analyses, we revised the relative stereochemistry of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone to that represented in compounds 55 and 56 in June 2008 (Figure 6). The new C-20 and C-25 configurations are now consistent with those of cyclopamine (3) and veratramine (4). The C-6 and C-20 configurations can also be easily rationalized by enzymatic halogenation reactions.23 The C-21 chlorine atoms are likely introduced by non-heme iron oxygen- and α-ketoglutarate-dependent halogenase through radical chlorination. This reaction would result in retention of the C-20 configuration. The C-6 bromine atom is likely introduced by vanadium-dependent bromoperoxidase through bromoetherification, giving anti-C-5,C-6 bromohydrin. These enzymatic oxidation reactions also inspired us to initiate a new research program to study catalytic carbon–hydrogen bond functionalization.24

Figure 6.

Biogenetic analysis of nakiterpiosin and the revised structures of nakiterpiosin (55) and nakiterpiosinone (56)

4 Synthesis of Nakiterpiosin

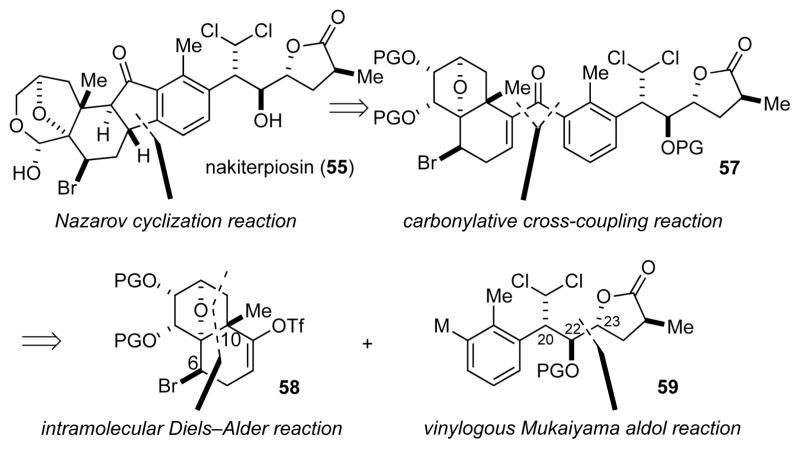

With the revised structures of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone in hand, we redirected our efforts to the synthesis of these compounds, i.e. 55 and 56, respectively. Our convergent strategy involved the construction of the central cyclopentanone ring using a carbonylative cross-coupling reaction25 and a Nazarov cyclization reaction26 at a late stage (Scheme 4). The coupling fragments 58 and 59 were prepared by an intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction27 and a vinylogous Mukaiyama aldol reaction,28 respectively. In retrospect, we were fortunate that this synthetic strategy allowed us to study the synthesis of the A,B-ring and the E-ring/side chain separately, thus confirming and solving the stereochemical issues of the natural products at an early stage of the project.

Scheme 4.

Retrosynthetic analysis of nakiterpiosin (55)

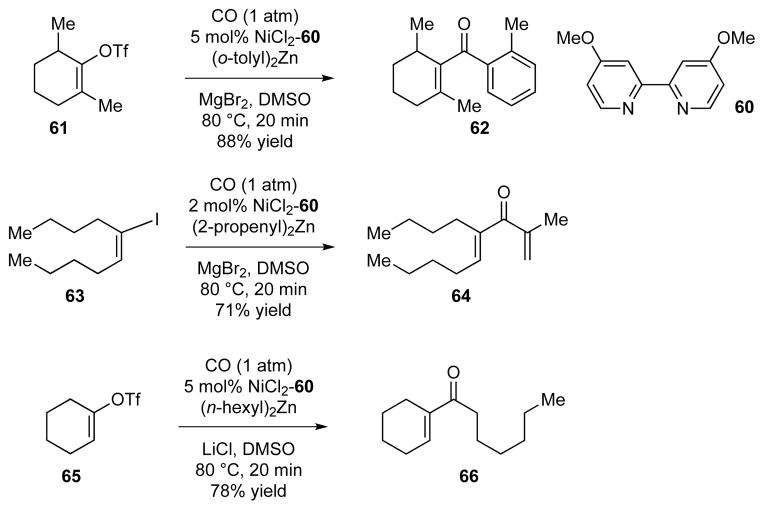

Despite recent advances in transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling chemistry, carbonylative cross-coupling reactions are still underdeveloped. We therefore devoted our efforts to creating a new catalyst system for the carbonylative Negishi coupling reaction. We found the complex system nickel(II) chloride–bipyridyl 60 to be an effective catalyst. Carbonylative vinyl–aryl, vinyl–vinyl, and vinyl–alkyl coupling could all be achieved in good yields (Scheme 5).29

Scheme 5.

Examples of the nickel-catalyzed carbonylative Negishi coupling reaction

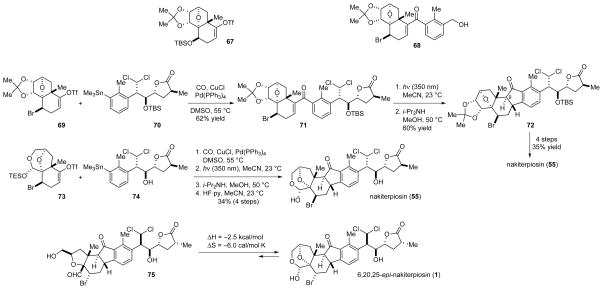

The steric hindrance, sensitive nature, and aromaticity of 57 made the implementation of the carbonylative coupling and the Nazarov cyclization reaction for the synthesis of target compound 55 challenging. We initially studied these reactions in model systems to identify suitable reaction conditions.

We quickly realized that triflate 67 (Scheme 6) is very sterically hindered, and the nickel-catalyzed carbonylative coupling of 67 with diphenylzinc gave almost no reaction. While palladium catalysts were found to be more effective for the carbonylation of 67, good yields of the corresponding carbonylative cross-coupling products were only obtained with tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0).

Scheme 6.

The convergent synthesis of the C-nor-D-homosteroid skeleton and the synthesis of nakiterpiosin (55)

We also found that the carbonylative coupling reaction needed to be carried out under neutral conditions, as the bromide was readily eliminated from 68 (Scheme 6) under weakly acidic or basic conditions. Unlike the Suzuki, Hiyama, Negishi, and Kumada coupling reactions, the Stille coupling reaction30 could be performed under neutral conditions and turned out to be an ideal solution for us. We noted that the addition of copper(I) iodide to facilitate transmetalation,31 the exclusion of lithium chloride for stabilizing the catalyst, and the use of polar dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solvent were all crucial to the successful carbonylative coupling of triflate 69 and stannane 70 to give ketone 71 (Scheme 6).

The Nazarov cyclization of vinyl aryl ketones involves a disruption of the aromaticity in the transition state and requires harsh conditions. Attempts to induce the Nazarov cyclization of ketone 68 (Scheme 6) under acidic conditions32 resulted only in decomposition, but irradiation of a solution of 68 in acetonitrile at 350 nm smoothly delivered the corresponding cyclization product.33 We finally achieved the synthesis of nakiterpiosin (55) for the first time on August 18, 2008, via the photolysis of 71 (Scheme 6).34 The spectroscopic data of 55 fully agreed with those of the natural samples. Professor Uemura also kindly provided us with a copy of the original NMR spectra of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone for direct comparison.

Later, we envisaged that all of the functional groups of nakiterpiosin (55) could tolerate the carbonylative Stille coupling and photo-Nazarov cyclization reactions, and we decided to construct the central cyclopentane ring by coupling the fully functionalized fragments 73 and 74 to improve the overall efficiency of the synthesis (Scheme 6).35 We also obtained a crystal structure of 55 and fully confirmed our assignment.

To further support our structural revision, we targeted the originally proposed structure of nakiterpiosin (1) and completed its synthesis on October 8, 2008. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 1 were significantly different from those of the natural product.35 In particular, compound 1 existed as an equilibrium mixture with hydroxymethyl-substituted aldehyde 75 (Scheme 6).

At this point, it seemed straightforward to complete the synthesis of nakiterpiosinone (56) from substrate 72. However, the establishment of the C-3 configuration was unexpectedly difficult; oxidative cleavage of the A-ring and skeletal rearrangement were frequently observed. We eventually redesigned the route for the A-ring functionalization and completed the synthesis of nakiterpiosinone (56) on September 24, 2009.35

5 Biology of Nakiterpiosin

The natural sample of nakiterpiosin obtained from sponges allowed Uemura and co-workers to identify a cytotoxic effect in P388 cells, but further biological investigations were not possible owing to a lack of sufficient quantities of the material. With the synthetic samples in hand, we initiated such functional studies in 2008.

Since nakiterpiosin (55) is structurally similar to the Hh inhibitor cyclopamine (3), we first tested its effects on the Hh signal transduction pathway using an NIH3T3 cell line based reporter and found that 55 effectively inhibited Hh signaling (half maximal effect concentration, EC50 = 0.6 μM).35 We further found that while the NIH3T3 cells were viable, they appeared to be stressed, as the expression of the controlling reporter was strongly upregulated in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, we found that 55 effectively suppressed Wnt signaling (EC50 = 0.3 μM). Based on these observations, we suspected that 55 did not directly target Smo and inhibited Hh signaling by an indirect mechanism.

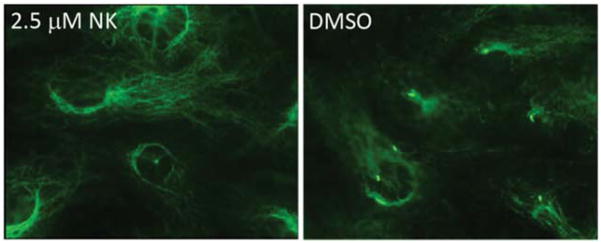

Next, we found that the NIH3T3 cells treated with nakiterpiosin (55) completely lost their primary cilia (Figure 7).35 The integrity of the Hh pathway is dependent on the presence of this microtubule-scaffolded cellular antenna. This result suggested that microtubules could be the target of 55.36

Figure 7.

NIH3T3 cells treated with 2.5 μM of nakiterpiosin (55, NK) and the DMSO control (stained by anti-Actubulin)

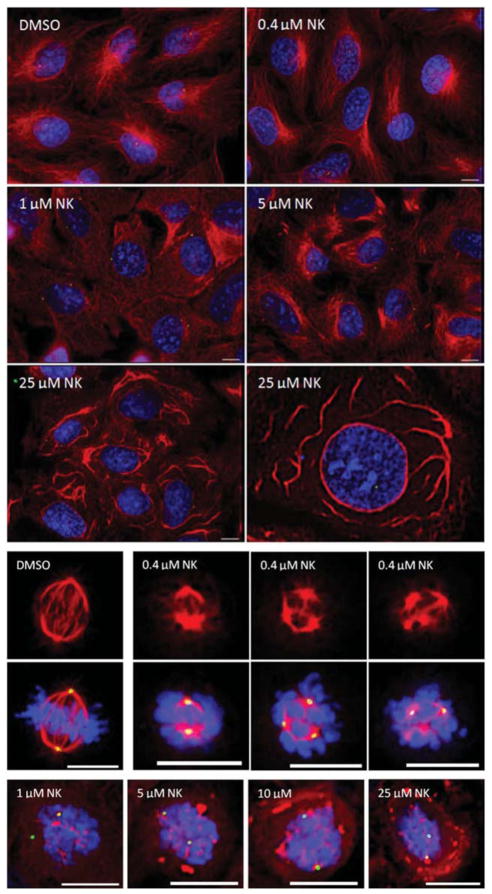

We therefore examined the effects of nakiterpiosin (55) on microtubules in HeLa cells (Figure 8). While 55 effectively inhibited the growth of HeLa cells, at the GI50 (half maximal growth inhibition) concentration (0.4 μM), the microtubule structures of cells in the interphase were not significantly affected, but multipolar spindles were formed in the mitotic cells. At high concentrations (>5 μM), microtubules consolidated in both interphasic and mitotic cells. It is likely that the multipolar spindles at the GI50 concentration are derived from impaired microtubule dynamics, since multipolar spindles were not observed in treatments with high concentrations of 55, in which microtubules formed aggregates and lost dynamics. We also tested if nakiterpiosin (55) targeted tubulin assembly directly and we found that the in vitro tubulin polymerization was not affected at 5 μM,35 although an induction of depolymerization at higher concentrations was later reported.37 We further found that 55 did not significantly change the level of acetylated tubulin at 2.5 μM. Consistently, it did not inhibit the in vitro activity of tubulin deacetylase HDAC6 at physiologically relevant concentrations (43% inhibition at 100 μM). However, it was reported that 55 induced tubulin acetylation at higher concentrations.37

Figure 8.

Interphasic (top) and mitotic (bottom) HeLa cells after treatment with nakiterpiosin (55) at different concentrations for 2 hours [DNA, microtubules, and centrosomes were stained by DAPI (blue), anti-α-tubulin (red), and pericentrin (green), respectively; scale bar, 5 μm]

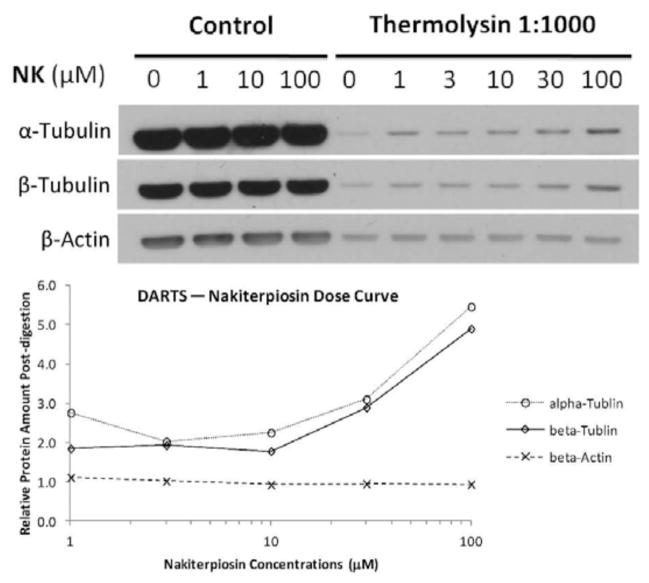

To further study the interactions between nakiterpiosin (55) and tubulins, we performed drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) experiments38 using lysates of Jurkat T-cells. We found that 55 protected both α- and β-tubulin from the 1:1000 thermolysin digestions at high concentrations in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting a weak interaction with tubulins (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Tubulin protection by nakiterpiosin (55) in drug affinity responsive target stability experiments

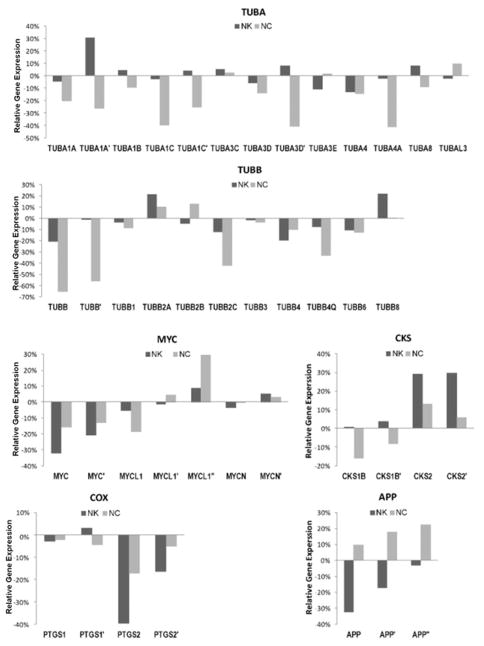

We performed genome-wide DNA microarrays and transcriptome analysis to profile the molecular response to 55 in the cells. A variant of human colon cancer cell line HT29 was selected for its susceptibility to anti-microtubule agents. Nocodazole, a microtubule depolymerizing agent, was used as the control. The cells were treated with the compounds at twofold quantities of the GI50 concentration (2 μM for 55 and 0.4 μM for nocodazole) for 4 hours before the total RNA were extracted for DNA microarray. We compared the relative gene expression profiles of cells upon drug treatment. Some of the top hits from the Ingenuity analysis are shown in Figure 10. Consistent with the low activity of 55 in our tubulin polymerization and DARTS experiments, effects on the expression of both α- and β-tubulin by 55 were generally weaker than the effects associated with nocodazole.

Figure 10.

Microarray analysis of nakiterpiosin (55) with nocodazole (NC) as the control [TUBA: α-tubulin; TUBB: β-tubulin; the relative gene expression upon drug treatment is calculated in comparison with DMSO (diluent) treatment]

We also observed significant differences in the expression level of various members of the Myc (myelocytomatosis viral oncogene) and Cks (CDC28 protein kinase regulatory subunit) gene families (Figure 10). In addition, nakiterpiosin (55) induced inhibition of the expression of COX-2 (cyclooxygenase-2, prostaglandin H synthase-2, or PTGS2), but not COX-1. While COX-2 is not expressed under normal conditions in most cells, its expression is elevated during inflammation. Traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit both COX-1 and -2. Selective COX-2 inhibitors are expected to have reduced gastric toxicity,39 although a recent study indicated that cardiovascular risk is a direct pharmacologic consequence of COX-2 inhibition.40 The expression of COX-2 is upregulated in many cancers.41 Thus, nakiterpiosin (55) may afford an alternative approach to disabling COX-2 activity in a cancerous context which bypasses the toxicity issues associated with NSAIDs.

Importantly, nakiterpiosin (55), but not nocodazole, also induced downregulation of APP (amyloid precursor protein). Amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides derived from APP by proteolytic cleavage are the main constituent of amyloid plaques found in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Mounting evidence supports that APP and Aβ contribute causally to the pathogenesis of AD. Overexpression of APP has been implicated in the early onset of AD in humans.42 Some cellular effects of 55 may be potentially beneficial in these disease settings.

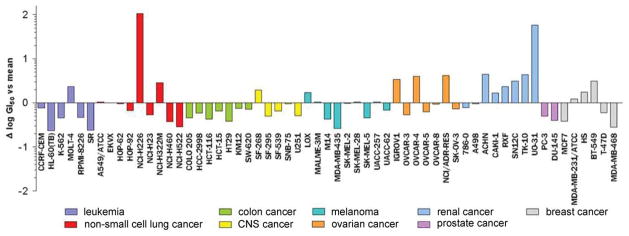

Finally, the growth inhibitory activity of nakiterpiosin (55) in the NCI-60 cell line panel was evaluated by the Developmental Therapeutics Program at the National Cancer Institute (NCI)/National Institutes of Health (NIH).43 The pattern of the differential activity of 55 (Figure 11) suggests it to be antimitotic with a tubulin-related mode of action. However, this pattern does not resemble those of known tubulin polymerizing and depolymerizing agents.

Figure 11.

The growth-inhibition pattern of NCI-60 cell lines by nakiterpiosin (55) (mean log GI50 = −6.32)

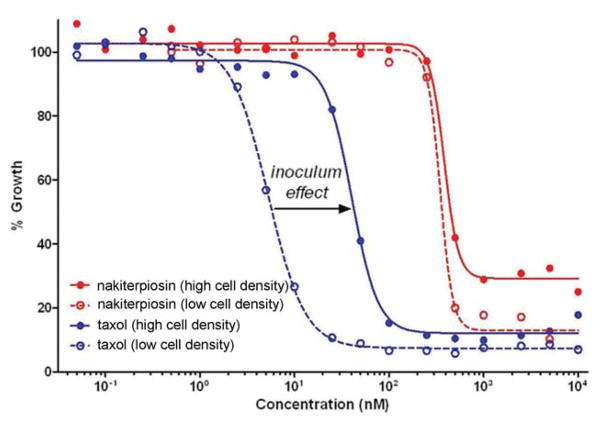

We also found that, unlike Taxol, nakiterpiosin (55) did not show an inoculum effect in the growth inhibition of HeLa cells.44 For example, its GI50 value was not sensitive to cell density (Figure 12). However, it did not suppress the growth of tumor cells in the confluent phase as completely as in the log phase. We have also tested the cytotoxicity of epi-nakiterpiosin (1) and fragments 45–54 on HeLa cells, but found them all nontoxic at up to 10 μM concentration.

Figure 12.

The effects of cell density on cytotoxicity

6 Conclusion

The 1950–1970s constitute a golden era for the chemistry of steroids. Despite the important biological functions of steroids, the synthetic community has turned its attention to other classes of natural products having higher structural diversity over the past decades. The discovery of cyclopamine (3) as a mysterious teratogen from plants has inspired the invention of many new synthetic methods and seeded the recent development of a new class of anticancer drugs (reminiscent of thalidomide!).

The recent isolation of rearranged steroids such as nakiterpiosin (55) and cortistatin45,46 has raised the attention of synthetic chemists again. The C-nor-D-homosteroid 55 bears a unique molecular skeleton and several unusual functional groups. It shows potential as a new anticancer drug, but the primary molecular target is still undefined. We hope that the synthetic and biological studies of this and other new classes of steroids will ignite a renaissance of steroid chemistry.

Acknowledgments

Financial support were provided by the NIH (Grants NIGMS R01-GM079554 to C. C., NCCAM R01 AT006889 to C. C. and J. H., NIGMS R01-GM076398 to L. L., and NCI P01 CA095471 to G. W.), the Welch Foundation (I-1596 to C. C. and I-1665 to L. L.), the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP100119 to L. L. and C. C.), UT Southwestern (C. C. as a Southwestern Medical Foundation Scholar in Biomedical Research and L. L as a Virginia Murchison Linthicum Scholar in Medical Research), and the National University of Singapore Academic Research Fund (Tier 1, R183000286112 to L.-W. D). We thank the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program (http://dtp.cancer.gov) for performing the human tumor cell line screen.

Biographies

Shuanhu Gao received his B.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Lanzhou University working in the laboratory of Professor Yong-Qiang Tu. Upon completion of his doctoral studies, he went to the USA and pursued postdoctoral research in the laboratory of Dr. J. R. Falck at the University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center. He later joined the laboratory of Dr. Chuo Chen to study natural product synthesis. He started his independent career as a professor in the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Green Chemistry and Chemical Process, Department of Chemistry, at East China Normal University in 2010. His current research interests are primarily focused on the synthesis of complex natural products.

Qiaoling Wang received her B.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Lanzhou University, working with professor Xuegong She and Xinfu Pan. Then she went to the USA and pursued postdoctoral research in the laboratory of Dr. Chuo Chen at the University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center. She later joined the State Key Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in 2011 as an associate professor, Her current research interests are primarily focused on the chemical synthesis of complex glyco-conjugates.

Gelin Wang received her B.S. degree and M. S. degree in microbiology from Wuhan University, where she also completed her Ph.D. in genetics in the laboratory of Dr. Ping Shen. She did her postdoctoral research in developmental biology with Dr. Jin Jiang, and later moved to the laboratory of Dr. Xiaodong Wang at the UT Southwestern Medical Center, where she focused on studying the mode-of-action of small molecules. Now she continues her research interest in Dr. Steven McKnight’s laboratory as an instructor in the Department of Biochemistry.

Brett Lomenick received his B.S. degree in molecular biology from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in 2007. While an undergraduate, he participated in the Pediatric Oncology Education Program at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and performed research on the genetics of kinetochore formation under Dr. Katsumi Kitagawa. He also performed research with Dr. Margaret Kovach at UTC studying microsatellite instability. Currently, Brett is a Ph.D. candidate in the laboratory of Dr. Jing Huang in the Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology at UCLA where he works on target identification and mechanism of action studies for several natural product compounds.

Jie Liu received her B.S. degree with a major in biomedical sciences from National University of Singapore. Upon graduation, she joined Dr. Deng Lih-Wen’s laboratory as a research assistant and later on embarked on a Ph.D. research program in the Department of Biochemistry at National University of Singapore. Her Ph.D. studies came to breakthrough with deciphering the molecular mechanism of Mixed Lineage Leukemia 5 in mitotic regulation. Currently, she works at Singapore Immunology Network and her research focuses on the host–pathogen interactions upon Mycobacterium infection.

Chih-Wei Fan received her B.S. degree in biochemistry from the Texas A&M University. She is currently pursuing her doctoral degree in cancer biology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Under the guidance of Dr. Lawrence Lum, she works on using a chemical biology approach to study the Hedgehog signal transduction pathway in cancer.

Lih-Wen Deng received her B.S. degree from National Taiwan University and her Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge, where she studied the binding interface between filamentous bacteriophage fd and the F-pilus of E. coli in Professor Richard Perham’s group. She then broadened her interest in protein–protein interactions to immunology, receiving postdoctoral training under the guidance of Professor Jack Strominger at Harvard University. She started her independent career as an assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry, National University of Singapore, in 2004. Her research is aimed at understanding the cellular and molecular mechanism of cancer and developing effective targeted therapies against the disease.

Jing Huang, born in Xiamen, China, received her B.S. degree in genetics from Fudan University. She completed her Ph.D. in biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of Southern California, working with the late Hal Weintraub and Larry Kedes. She then did postdoctoral research in chemistry and chemical biology at Harvard University as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute postdoctoral fellow with Stuart L. Schreiber. She joined the University of California, Los Angeles, in 2001 as an assistant professor and is currently an associate professor of molecular and medical pharmacology. Her laboratory’s research focuses on developing novel methods and identifying new molecules for aging and cancer studies.

Lawrence Lum received his B.A. degree with a major in biochemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, where he also performed research in the laboratory of Dr. Howard K. Schachman. He enrolled in an M.D.-Ph.D. joint degree program at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University in New York City, where he completed his Ph.D. in the laboratory of Dr. Carl P. Blobel at the Sloan-Kettering Institute. He elected not to complete his M.D. degree after attending a lecture from Dr. Philip A. Beachy, an expert in developmental biology and signal transduction, who would later become his postdoctoral research advisor. After five years at Johns Hopkins University Medical School in Dr. Beachy’s laboratory, he began his own research at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas in 2004 as an assistant professor in the Department of Cell Biology.

Chuo Chen was born in Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China (R.O.C.). He received his B.S. degree from National Taiwan University working in the laboratory of Professor Tien-Yau Luh. Following the completion of his doctoral studies at Harvard University under the direction of Professor Matthew D. Shair, he worked as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard in the laboratory of Professor Stuart L. Schreiber. He joined the faculty at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in 2004 as a Southwestern Medical Foundation Scholar in Biomedical Research, and is now an associate professor. His laboratory focuses on the synthesis of natural products and Hedgehog (Hh)/Wnt inhibitors.

References

- 1.(a) Bryan PG. Micronesica. 1973;9:237. [Google Scholar]; (b) Plucer-Rosario G. Coral Reefs. 1987;5:197. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rützler K, Smith KP. Sci Mar. 1993;57:381. [Google Scholar]; (d) Rützler K, Smith KP. Sci Mar. 1993;57:395. [Google Scholar]; (e) Liao MH, Tang SL, Hsu CM, Wen KC, Wu H, Chen WM, Wang JT, Meng PJ, Twan WH, Lu CK, Dai CF, Soong K, Chen CA. Zool Stud. 2007;46:520. [Google Scholar]; (f) Lin W-j. MS thesis. National Sun Yatsen University; Kaohsiung, Taiwan R.O.C: 2009. [Google Scholar]; (g) Tang SL, Hong MJ, Liao MH, Jane WN, Chiang PW, Chen CB, Chen CA. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Teruya T, Nakagawa S, Koyama T, Suenaga K, Kita M, Uemura D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:5171. [Google Scholar]; (b) Teruya T, Nakagawa S, Koyama T, Arimoto H, Kita M, Uemura D. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:6989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Binns W, James LF, Keeler RF, Balls LD. Cancer Res. 1968;28:2323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keeler RF. Lipids. 1978;13:708. doi: 10.1007/BF02533750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) James LF. J Nat Toxins. 1999;8:63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Cooper MK, Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA. Science (Washington, DC, US) 1998;280:1603. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Incardona JP, Gaffield W, Kapur RP, Roelink H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:3553. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen JK, Taipale J, Cooper MK, Beachy PA. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2743. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang Y, Zhou Z, Walsh CT, McMahon AP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812110106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Corcoran RB, Scott MP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813373106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Nüsslein-Volhard C. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:2176. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wieschaus E. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;36:2188. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Scalesa SJ, de Sauvage FJ. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:303. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Epstein EH. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:743. doi: 10.1038/nrc2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) van den Brink GR. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1343. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00054.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Romer J, Curran T. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hooper JE, Scott MP. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:306. doi: 10.1038/nrm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Borzillo GV, Lippa B. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:147. doi: 10.2174/1568026053507732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Dellovade T, Romer JT, Curran T, Rubin LL. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yauch RL, Gould SE, Scales SJ, Tang T, Tian H, Ahn CP, Marshall D, Fu L, Januario T, Kallop D, Nannini-Pepe M, Kotkow K, Marsters JC, Rubin LL, de Sauvage FJ. Nature (London) 2008;455:406. doi: 10.1038/nature07275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Masamune T, Takasugi M, Murai A, Kobayashi K. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:4521. [Google Scholar]; (b) Masamune T, Takasugi M, Murai A. Tetrahedron. 1971;27:3369. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4020(01)92644-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Johnson WS, deJongh HAP, Coverdale CE, Scott JW, Burckhardt U. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:4523. [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson WS, Cox JM, Graham DW, Whitlock HW., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:4524. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masamune T, Mori Y, Takasugi M, Murai A, Ohuchi S, Sato N, Katsui N. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1965;38:1374. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.38.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Kutney JP, By A, Cable J, Gladstone WAF, Inaba T, Leong SY, Roller P, Torupka EJ, Warnock WDC. Can J Chem. 1975;53:1775. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kutney JP, Cable J, Gladstone WAF, Hanssen HW, Nair GV, Torupka EJ, Warnock WDC. Can J Chem. 1975;53:1796. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oatis JE, Jr, Brunsfeld P, Rushing JW, Moeller PD, Bearden DW, Gallien TN, Cooper GIV. Chem Cent J. 2008;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannis A, Heretsch P, Sarli V, Stößel A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:7911. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Hirschmann R, Snoddy CS, Jr, Wendler NL. J Am Chem Soc. 1952;74:2693. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hiskey CF, Hirschmann R, Wendler NL. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:5135. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hirschmann R, Snoddy CS, Jr, Hiskey CF, Wendler NL. J Am Chem Soc. 1954;76:4013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Mitsuhashi H, Shibata K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1964;5:2281. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mitsuhashi H, Shimizu Y, Moriyama T, Masuda M, Kawahara N. Chem Pharm Bull. 1974;22:1046. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mitsuhashi H, Shimizu Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1961;2:777. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu X, Chan TM, Tann CH, Thiruvengadam TK. Steroids. 2002;67:549. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heretsch P, Rabe S, Giannis A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9968. doi: 10.1021/ja103152k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Johnson WS, Szmuszkovicz J, Rogier ER, Hadler HI, Wynberg H. J Am Chem Soc. 1956;78:6285. [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson WS, Rogier ER, Szmuszkovicz J, Hadler HI, Ackerman J, Bhattacharyya BK, Bloom BML, Stalmann R, Clement A, Bannister B, Wynberg H. J Am Chem Soc. 1956;78:6289. [Google Scholar]; (c) Franck RW, Johnson WS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1963;4:545. [Google Scholar]; (d) Johnson WS, Cohen N, Habicht ER, Jr, Hamon DPG, Rizzi GP, Faulkner DJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;9:2829. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Brown E, Lebreton J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:2595. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brown E, Lebreton J. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:5827. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceustermans RAE, Martens HJ, Hoornaert GJ. J Org Chem. 1979;44:1388. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Marsault E, Toró A, Nowak P, Deslongchamps P. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:4243. [Google Scholar]; (b) Porco JA, Jr, Schoenen FJ, Stout TJ, Clardy J, Schreiber SL. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7410. [Google Scholar]; (c) Roush WR, Koyama K, Curtin ML, Moriarty KJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7502. [Google Scholar]; (d) Vosburg DA, Vanderwal CD, Sorensen EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4552. doi: 10.1021/ja025885o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Evans DA, Starr J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1787. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1787::aid-anie1787>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Ito T, Ito M, Arimoto H, Takamura H, Uemura D. Tetrahedron. 2007;48:5465. [Google Scholar]; (b) Takamura H, Yamagami Y, Ito T, Ito M, Arimoto H, Kadota I, Uemura D. Heterocycles. 2009;77:351. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Pattenden G, Wiedenau P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3647. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pattenden G, Gonzalez MA, McCulloch S, Walter A, Woodhead SJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401925101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stoker DA. PhD thesis. University of Nottingham; U.K: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Vaillancourt FH, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Walsh CT. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3364. doi: 10.1021/cr050313i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Neumann CS, Fujimori DG, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 2008;15:99. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Butler A, Walker JV. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1937. [Google Scholar]; (d) Butler A, Sandy M. Nature (London) 2009;460:848. doi: 10.1038/nature08303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia JB, Cormier KW, Chen C. Chem Sci. 2012;3:2240. doi: 10.1039/C2SC20178J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Brennführer A, Neumann H, Beller M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4114. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Barnard CFJ. Organometallics. 2008;27:5402. [Google Scholar]; (c) Skoda-Földes R, Kollár L. Curr Org Chem. 2002;6:1097. [Google Scholar]; (d) Brunet JJ, Chauvin R. Chem Soc Rev. 1995;24:89. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Vaidya T, Eisenberg R, Frontier AJ. ChemCatChem. 2011;3:1531. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shimada N, Stewart C, Tius MA. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:5851. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakanishi W, West FG. Curr Opin Drug Discovery Dev. 2009;12:732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:6479. [Google Scholar]; (e) Habermas KL, Denmark SE, Jones TK. Org React. 1994;45:1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Takao K-i, Munakata R, Tadano K-i. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4779. doi: 10.1021/cr040632u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Roush WR. In: In Advances in Cycloaddition. Curran DP, editor. Vol. 2. Jai; Greenwich: 1990. pp. 91–146. [Google Scholar]; (c) Craig D. Chem Soc Rev. 1987;16:187. [Google Scholar]; (d) Taber DF. Intramolecular Diels-Alder and Alder Ene Reactions - Reactivity and Structure: Concepts in Organic Chemistry. Vol. 8. Springer; Berlin: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Brodmann T, Lorenz M, Schäckel R, Simsek S, Kalesse M. Synlett. 2009:174. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hosokawa S, Tatsuta K. Mini-Rev Org Chem. 2008;5:1. [Google Scholar]; (c) Denmark SE, Heemstra J, John R, Beutner GL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4682. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Casiraghi G, Zanardi F, Appendino G, Rassu G. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1929. doi: 10.1021/cr990247i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rassu G, Zanardi F, Battistinib L, Casiraghi G. Chem Soc Rev. 2000;29:109. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Chen C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:2916. [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Crisp GT, Scott WJ, Stille JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:7500. [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith AB, III, Cho YS, Ishiyama H. Org Lett. 2001;3:3971. doi: 10.1021/ol016888t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xiang AX, Watson DA, Ling T, Theodorakis EA. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6774. doi: 10.1021/jo981331l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Angle SR, Fevig JM, Knight SD, Marquis RW, Overman LE. J Am Chem Soc. 1993:3966. [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Han X, Stoltz BM, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7600. [Google Scholar]; (b) Farina V, Kapadia S, Krishnan B, Wang C, Liebeskind LS. J Org Chem. 1994;59:5905. [Google Scholar]; (c) Liebeskind LS, Fengl RW. J Org Chem. 1990;55:5359. [Google Scholar]; (d) Marino JP, Long JK. J Org Chem. 1988;110:7916. [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Marcus AP, Lee AS, Davis RL, Tantillo DJ, Sarpong R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6379. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) He W, Herrick IR, Atesin TA, Caruana PA, Kellenberger CA, Frontier AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1003. doi: 10.1021/ja077162g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liang G, Xu Y, Seiple IB, Trauner D. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11022. doi: 10.1021/ja062505g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Crandall JK, Haseltine RP. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:6251. [Google Scholar]; (b) Noyori R, Katô M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;9:5075. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith AB, III, Agosta WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:1961. [Google Scholar]; (d) Leitich J, Heise I, Werner S, Krürger C, Schaffner K. J Photochem Photobiol, A. 1991;57:127. [Google Scholar]; (e) Leitich J, Heise I, Rust J, Schaffner K. Eur J Org Chem. 2001:2719. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao S, Wang Q, Chen C. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1410. doi: 10.1021/ja808110d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao S, Huang QWLJ-S, Lum L, Chen C. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:371. doi: 10.1021/ja908626k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Boisvieux-Ulrich E, Lainé MC, Sandoz D. Biol Cell. 1989;67:67. doi: 10.1111/j.1768-322x.1989.tb03011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Piperno G, LeDizet M, Chang X-j. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:289. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.2.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rosenbaum JL, Carlson K. J Cell Biol. 1969;40:415. doi: 10.1083/jcb.40.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei JH, Seemann J. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3375. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) Lomenick B, Olsen RW, Huang J. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:34. doi: 10.1021/cb100294v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lomenick B, Jung G, Wohlschlegel JA, Huang J. Curr Protoc Chem Biol. 2011;3:163. doi: 10.1002/9780470559277.ch110180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lomenick B, Hao R, Jonai N, Chin RM, Aghajan M, Warburton S, Wang J, Wu RP, Gomez F, Loo JA, Wohlschlegel JA, Vondriska TM, Pelletier J, Herschman HR, Clardy J, Clarked CF, Huang J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910040106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurumbail R, Kiefer JR, Marnett LJ. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:752. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(01)00277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu Y, Ricciotti E, Scalia R, Tang SY, Grant G, Yu Z, Landesberg G, Crichton I, Wu W, Puré E, Funk CD, FitzGerald GA. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:132ra54. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menter DG, Schilsky RL, Dubois RN. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1384. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang Y, Mucke L. Cell (Cambridge, MA, USA) 2012;148:1204. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.(a) Shoemaker RH. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:813. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boyd MR, Paull KD. Drug Dev Res. 1995;34:91. [Google Scholar]; (c) Monks A, Scudiero D, Skehan P, Shoemaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, Hose C, Langley J, Cronise P, Vaigro-Wolff A, Gray-Goodrich M, Campbell H, Mayo J, Boyd M. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:757. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.(a) Takemura Y, Kobayashi H, Miyachi H, Hayashi K, Sekiguchi S, Ohnuma T. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1991;27:417. doi: 10.1007/BF00685154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi H, Takemura Y, Ohnuma T. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1992;31:6. doi: 10.1007/BF00695987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kobayashi H, Takemura Y, Holland JF, Ohnuma T. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1229. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00615-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kuh HJ, Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Au JLS. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.(a) Aoki S, Watanabe Y, Sanagawa M, Setiawan A, Kotoku N, Kobayashi M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3148. doi: 10.1021/ja057404h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shenvi RA, Guerrero CA, Shi J, Li CC, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7241. doi: 10.1021/ja8023466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shi J, Manolikakes G, Yeh CH, Guerrero CA, Shenvi RA, Shigehisa H, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8014. doi: 10.1021/ja202103e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nicolaou KC, Sun YP, Peng XS, Polet D, Chen DYK. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:7310. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Nicolaou KC, Peng XS, Sun YP, Polet D, Zou B, Lim CS, Chen DYK. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10587. doi: 10.1021/ja902939t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lee HM, Nieto-Oberhuber C, Shair MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16864. doi: 10.1021/ja8071918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Flyer AN, Si C, Myers AG. Nat Chem. 2010;2:886. doi: 10.1038/nchem.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yamashita S, Kitajima K, Iso K, Hirama M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:3277. [Google Scholar]; (i) Yamashita S, Iso K, Kitajima K, Himuro M, Hirama M. J Org Chem. 2011;76:2408. doi: 10.1021/jo2002616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Simmons EM, Hardin-Narayan AR, Guo X, Sarpong R. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4696. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Nilson MG, Funk RL. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12451. doi: 10.1021/ja206138d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Fang L, Chen Y, Huang J, Liu L, Quan J, Li C-c, Yang Z. J Org Chem. 2011;76:2479. doi: 10.1021/jo102202t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.(a) Craft DT, Gung BW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:5931. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.07.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dai M, Wang Z, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:6613. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Magnus P, Littich R. Org Lett. 2009;11:3938. doi: 10.1021/ol901537n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Frie JL, Jeffrey CS, Sorensen EJ. Org Lett. 2009;11:5394. doi: 10.1021/ol902168g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Baumgartner C, Ma S, Liu Q, Stoltz BM. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:2915. doi: 10.1039/c004275g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yu F, Li G, Gao P, Gong H, Liu Y, Wu Y, Cheng B, Zhai H. Org Lett. 2010;12:5135. doi: 10.1021/ol102058f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Liu LL, Chiu P. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3416. doi: 10.1039/c1cc00087j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kotoku N, Sumii Y, Kobayashi M. Org Lett. 2011;13:3514. doi: 10.1021/ol201327u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Czakó B, Kürti L, Mammoto A, Ingber DE, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9014. doi: 10.1021/ja902601e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]