Purification, crystallization, preliminary X-ray diffraction and molecular-replacement studies have been carried out on Clarias magur haemoglobin.

Keywords: fish haemoglobin, Clarias magur

Abstract

Haemoglobin is an interesting physiologically significant protein composed of specific functional prosthetic haem and globin moieties. In recent decades, there has been substantial interest in attempting to understand the structural basis and functional diversity of fish haemoglobins (Hbs). Towards this end, purification, crystallization, preliminary X-ray diffraction and molecular-replacement studies have been carried out on Clarias magur Hb. Crystals were grown by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method using PEG 2000 and NaCl as precipitants. The crystals belonged to the primitive monoclinic system P2, with unit-cell parameters a = 98.35, b = 56.63, c = 112.88 Å, β = 100.22°; a complete data set was collected to a resolution of 2.4 Å. The Matthews coefficient of 2.42 Å3 Da−1 for the crystal indicated the presence of two α2β2 tetramers in the asymmetric unit.

1. Introduction

The strategies adopted by animals to regulate the supply of oxygen for their biological demands may be broadly classified into two types: one involving the anatomy of the respiratory system and the other involving the physiology, including the structural characteristics, of the oxygen-transport protein, i.e. haemoglobin (Hb). The Hb molecule has two α and two β subunits, each of which contains a ferrous haem group to which oxygen binds reversibly. A characteristic structural feature of Hbs is the presence of seven or eight helices, called the ‘globin fold’, in each subunit. At the quaternary level, Hb, according to the allosteric theory proposed by Monod and coworkers, adopts two stable structures: the T (tensed or unliganded) and the R (relaxed or liganded) states (Monod et al., 1965 ▶). In addition to the T and R states, another liganded conformation, the R2 state, has been proposed by Silva et al. (1992 ▶). RR2 and R3 conformations have been proposed by Mueser et al. (2000 ▶). The major allosteric effectors that bind to fish Hb are GTP and ATP, although some species use 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG) and inositol pentaphosphate (IPP) (Val, 2000 ▶); these preferentially bind to T-state Hb and facilitate the uploading of oxygen from red blood cells (RBC) to tissues. In fish, hypoxia decreases the ATP/GTP content and increases the blood oxygen affinity (Wood & Johansen, 1973 ▶); where both ATP and GTP are present, GTP acts as the primary modulator. The amino acids that are principally responsible for the Bohr effect and other heterotrophic interactions in human Hb are known from structural and functional studies of native and modified Hb. However, the Bohr effect varies considerably between species within classes. For example, the diverse group of teleost fish have multiple Hb components in their RBC, some of which have a high Bohr effect (anodic) and some of which have a low or no Bohr effect (cathodic). Another unique feature in teleost fish is the Root effect, which is an extreme pH sensitivity where the Hb not only shows a strong decrease in oxygen affinity at low pH but also loses its cooperativity (Brittain, 1987 ▶). Some fish (e.g. carp, tench and plaice) show no elevation of blood Hb despite exposure to much more severe hypoxia than that encountered by mammals or birds, whereas others (e.g. trout, yellowtail and eel) do show elevated Hb (Weber & Jensen, 1988 ▶). Previously, we have carried out physicochemical and biochemical studies on catfish (Clarias magur) collagen in various environments using hydrodynamic and thermodynamic studies and geometric computations (Rose et al., 1988 ▶; Rose & Mandal, 1996 ▶). Moreover, C. magur (Day, 1981 ▶) has some unusual cavities in the throat and the gill chamber regions that are covered by flat tissue (epithelium) which is richly supplied with blood and connected to diminutive blood capillaries. Intake of oxygen and release of carbon dioxide takes place in these cavities, in addition to the normal gill respiration, which is considerably reduced in these forms. The acquisition of such accessory respiratory organs enables these fish to survive out of water for up to 24 h. Thus, catfish Hb was investigated with a view to understanding its oxygen affinity as well as the survival mechanism.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Isolation and purification

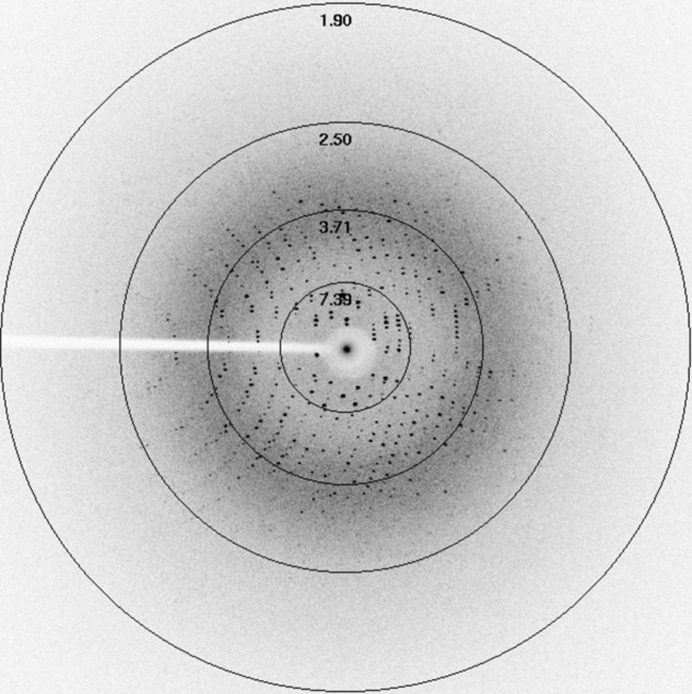

A 35 cm long healthy fish was caught from its enclosure. A 10 ml syringe containing 0.01% EDTA was used to collect blood and was transported immediately, maintaining the temperature below 277 K using an ice pack. The blood sample was centrifuged in a cooling centrifuge for 10 min at 717g, the pellets were washed with 0.9% NaCl twice and haemolysed with an equal volume of deionized distilled (Milli-Q) water (Millipore). To remove cell debris and other organelles, 0.2 ml CCl4 was added and the mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 1120g. A small portion of the pellet was used to check for protein content (Bradford, 1976 ▶) and to check the purity (Fig. 1 ▶; Laemmli, 1970 ▶). This was followed by gel filtration on Sephadex G-50 equilibrated with 50 mM Tris pH 7.5. The isolated protein was extensively dialyzed against distilled water for 24 h to remove trace salts and was used for crystallization.

Figure 1.

12% native PAGE gel stained with Coomassie Blue: lane 1, catfish haemolysate Hb; lane 2, molecular-mass markers (Sigma; labelled in kDa).

2.2. Crystallization and X-ray data collection

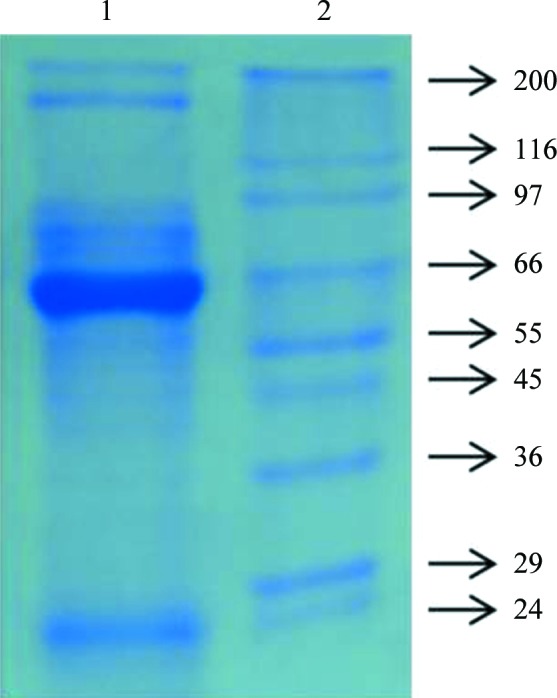

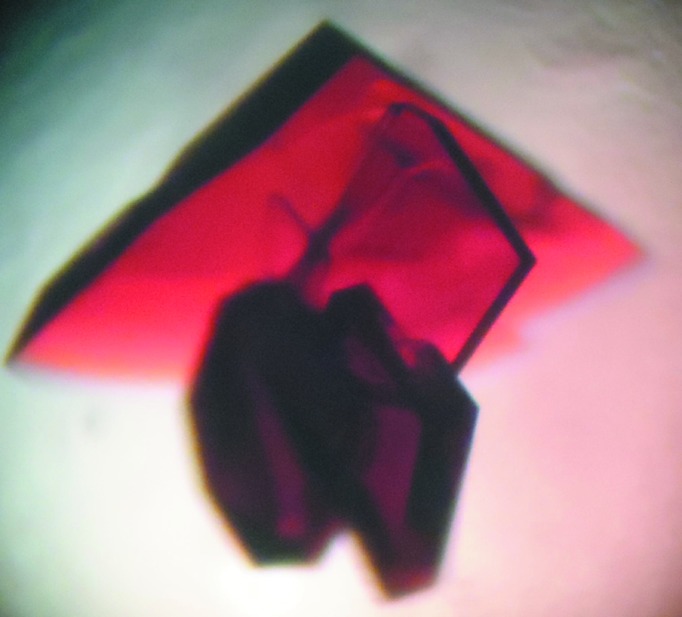

Crystals were grown by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method using 6 µl droplets consisting of equal volumes of 20 mg ml−1 protein solution and reservoir solution consisting of 42%(w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 2000, 0.1 M NaCl. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction grew within 3 d at 291 K (Fig. 2 ▶). The Hb crystals were mounted in a quartz capillary for X-ray diffraction on an in-house diffractometer equipped with a CCD detector. A total of 120 frames were collected at 291 K using a crystal-to-detector distance of 100 mm, an oscillation angle of 1° and an exposure time of 360 s per image; the crystal diffracted to a maximum resolution of 2.4 Å (Fig. 3 ▶). Intensity measurements were processed and analyzed using iMOSFLM (Battye et al., 2011 ▶). The data-collection and processing statistics are summarized in Table 1 ▶.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional single crystals of catfish Hb.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction pattern of catfish Hb. Resolution rings are labelled in Å.

Table 1. X-ray data-collection and processing statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| X-ray source | Cu Kα |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 |

| No. of crystals used | 1 |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 100 |

| Resolution (Å) | 29.61–2.46 |

| R merge † (%) | 8.8 (35) |

| Space group | P2 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 98.35, b = 56.63, c = 112.88, β = 100.22 |

| Asymmetric unit contents | α2β2 tetramer |

| Completeness (%) | 94.3 (97.7) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 5.5 (2.1) |

| Multiplicity | 2.5 (2.3) |

| No. of observations | 103016 |

| No. of unique reflections | 42020 |

| V M (Å3 Da−1) | 2.42 |

| Solvent content (%) | 49.14 |

R

merge =

, where I

i(hkl) is the ith measured intensity of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity.

, where I

i(hkl) is the ith measured intensity of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity.

2.3. Molecular replacement

Initial attempts were made to identify the molecular packing based on its symmetry axis by the molecular-replacement method using the program AMoRe (Navaza, 1994 ▶) implemented in CCP4 (Winn et al., 2011 ▶). The atomic coordinates of fish haemoglobin (PDB entry 1gcv; Naoi et al., 2001 ▶) from the Protein Data Bank (Berman et al., 2000 ▶) were used as a search model; the non-H atoms of the haem were removed from the model to avoid model bias. A common feature of haemoglobins is the presence of a haem with a T-state or an R-state conformation. Rotation and translation searches were calculated using reflections in the resolution range 15–3.0 Å and an integration radius of 25 Å. Furthermore, several models that were subsequently computed using data in the same resolution range yielded similar correlation coefficients (CCs) and R factors. The best model was selected based on the CC and the R factor for further refinement.

3. Results and discussion

Catfish haemoglobin was purified by centrifugation and size-exclusion chromatography followed by extensive dialysis in water for 24 h and was used for crystallization. Diffraction-quality crystals were grown using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method from a reservoir solution containing 42%(w/v) PEG 2000 and sodium chloride as precipitants. Ward and coworkers did not find any major differences between the structures of deoxy haemoglobin A obtained using high-salt and low-salt crystallization conditions (Ward et al., 1975 ▶). The majority of the observed reflections were indexed in the primitive monoclinic space group P2, with unit-cell parameters a = 98.35, b = 56.63, c = 112.88 Å, β = 100.22°. A Matthews coefficient (V M) of 2.42 Å3 Da−1 (Matthews, 1968 ▶) and a solvent content of 49.14% were obtained assuming the presence of an α2β2 tetramer in the asymmetric unit. A complete data set was collected to a resolution of 2.46 Å. A total of 103 016 measured reflections were merged into 42 020 unique reflections with an R merge of 8.8%. The mean I/σ(I) and overall completeness of the merged data set were 5.5% and 94.3%, respectively. Initial refinement was carried out in REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▶) implemented in the CCP4 suite; a randomly selected 5% of the total reflections were used for cross-validation (Brünger, 1992 ▶). Several rounds of refinement resulted in R and R free values of 0.32 and 0.39, respectively. 2mF o − F c electron density was observed between the distal histidine and the Fe haem of all subunits, suggesting liganded (oxy or aquomet) haemoglobin. However, the complete amino-acid sequence of catfish Hb has yet to be determined, so mutating the corresponding amino acids based on the electron-density map is not presently possible. Model building and final refinement of catfish Hb will be carried out after the complete amino-acid sequence has been determined.

Acknowledgments

SMJ is grateful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) for a research fellowship under the Nanobiotechnology Including Health, Disease and Medicinal Programme.

References

- Battye, T. G. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. W. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M. M. (1976). Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brittain, T. (1987). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B, 86, 473–481. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brünger, A. T. (1992). Nature (London), 355, 472–474. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Day, F. (1981). The Fishes of India, Vol. I, p. 484. New Delhi: Today & Tomorrow’s Book Agency.

- Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Nature (London), 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Monod, J., Wyman, J. & Changeux, J.-P. (1965). J. Mol. Biol. 12, 88–118. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mueser, T. C., Rogers, P. H. & Arnone, A. (2000). Biochemistry, 39, 15353–15364. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Naoi, Y., Chong, K. T., Yoshimatsu, K., Miyazaki, G., Tame, J. R. H., Park, S.-Y., Adachi, S. & Morimoto, H. (2001). J. Mol. Biol. 307, 259–270. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Navaza, J. (1994). Acta Cryst. A50, 157–163.

- Rose, C., Kumar, M. & Mandal, A. B. (1988). Biochem. J. 249, 127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rose, C. & Mandal, A. B. (1996). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 18, 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Silva, M. M., Rogers, P. H. & Arnone, A. (1992). J. Biol. Chem. 267, 17248–17256. [PubMed]

- Val, A. L. (2000). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A, 125, 417–435. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ward, K. B., Wishner, B. C., Lattman, E. E. & Love, W. E. (1975). J. Mol. Biol. 98, 161–177. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weber, R. E. & Jensen, F. B. (1988). Annu. Rev. Physiol. 50, 161–179. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

- Wood, S. C. & Johansen, K. (1973). Neth. J. Sea Res. 7, 328–338.