Abstract

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) and phorbol-12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) stimulate phospholipase D (PLD) activity and phosphatidylcholine (PC) hydrolysis in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells [1]. The current studies were designed to determine whether ethanolamine-containing phospholipids, and specifically phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), could also be substrates. In cells labeled with 14C-ethanolamine PTH and PDBu treatment decreased 14C-phosphatidylethanolamine. In cells co-labeled with 3H-choline and 14C-ethanolamine, PTH and PDBu treatment increased both 3H-choline and 14C-ethanolamine release from the cells. Choline and ethanolamine phospholipid hydrolysis was increased within 5 min, and responses were sustained for at least 60 min. Maximal effects were obtained with 10 nM PTH and 50 nM PDBu. Dominant negative PLD1 and PLD2 constructs inhibited the effects of PTH on the phospholipid hydrolysis. The results suggest that both PC and PE are substrates for phospholipase D in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells and could therefore be sources of phospholipid hydrolysis products for downstream signaling in osteoblasts.

Keywords: Phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, phospholipase D, parathyroid hormone, osteoblast, UMR-106

INTRODUCTION

Phospholipase D (PLD) is activated by a number of extracellular signaling factors including growth factors, neurotransmitters, and hormones [2,3]. PLD-mediated phospholipid hydrolysis modulates membrane composition and produces second messenger molecules [4]. It plays a key role in cellular signaling processes leading to cytoskeletal organization, vesicle trafficking, cell proliferation and differentiation. Previously, we demonstrated that PTH stimulates PC breakdown and PLD activity, as assessed by transphosphatidylation, in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells [1]. We have also shown that calcium, MAPK, small G proteins and Gα12/Gα13 heterotrimeric G proteins are involved in regulation of the PTH-stimulated PLD activity [5,6]. In the latter studies, transphosphatidylation of ethanol, a process directly mediated by PLD, was used as an indicator of PLD activity. Comparisons between results of experiments in which either PC hydrolysis or transphosphatidylation were assayed revealed that the PTH- or PDBu-stimulated effects, as measured by transphosphatidylation, were greater than those from PC hydrolysis. These data suggested that additional phospholipid species might be involved in the actions of PTH and PDBu. Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) is another major phospholipid component of biological membranes. Kiss and Anderson [7] have shown that phorbol ester stimulates PE hydrolysis in leukemic HL-60, NIH 3T3, and BHK-21 cells. Nakamura et al [8] determined that PC and PE are both substrates for PLD activity in bovine kidney. However, in other studies, PLDs 1 and 2 showed little [9] or no [10] activity on PE. An N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine-hydrolyzing phospholipase D has also been identified in mammalian cells [11,12]. To address the question of whether ethanolamine-containing phospholipids, and specifically PE, could be hydrolyzed in addition to PC in response to PTH or PDBu in UMR-106 cells, we determined the effects of PTH and PDBu on hydrolysis of PE as well as hydrolysis of PC in dual labeled UMR-106 cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

UMR-106 osteoblastic cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). PTH was from Bachem (Torrance, CA). PDBu was from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Loius, MO). [Methyl-3H]-choline chloride was from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL), and [2-14C] ethan-1-ol-2-amine hydrochloride was from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Dominant negative phospholipase D constructs were generated as previously described [13].

Cells

UMR-106 osteoblastic cells were cultured to confluence in DMEM with 15% heat-inactivated horse serum and 100 U/ml K-penicillin G at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment. Cells from passages 16 to 18 were used. For experiments, cells were then seeded at 500,000 cells per well in sterile 6-well plates and allowed to attach for 24 hr.

Phosphatidylcholine or Phosphatidylethanolamine Hydrolysis

To assess PC or PE hydrolysis, UMR-106 cells were incubated for 48 h with [methyl-3H]-choline chloride (0.25 μCi/ml) and [2-14C] ethanolamine hydrochloride (0.1 μCi/ml). Radioactivity in PC and PE reached a plateau by this time point. After the labeling, cells were washed with DMEM, and incubated in 2 ml serum-free DMEM containing 20 mM HEPES buffer and 0.1% BSA in the absence or presence of PTH, or PDBu. Following incubation at the indicated times and concentrations, media were quickly removed, and radioactivity in the media determined by dual channel scintillation spectrometry.

To determine the specificity of the incorporation of the choline and ethanolamine labels, 3H and 14C were determined in both the choline and ethanolamine released into the medium. A 20μl aliquot of the medium was spotted on a TLC plate. Choline and ethanolamine were separated using 0.5% NaCl/CH3OH/NH4OH (50:50:5) and visualized by exposing the plate to iodine. The plates were autoradiographed for two weeks at −80°C. The choline (Rf = 0.14) and ethanolamine (Rf = 0.5) bands were scraped and counted by liquid scintillation.

To determine whether PE was affected by the treatments, cells were labeled with 14C-ethanolamine, treated with PTH or PDBu for 60 minutes, scraped into ice-cold methanol and lipids extracted. The organic phase was dried under N2, re-equilibrated in 100 μl CHCl3/CH3OH (9:1), and 50 μl spotted on a TLC plate. PE (Rf = 0.54) was separated using CHCl3/CH3OH/NH4OH (65:25:5) as the running solvent. Samples were spiked with a PE standard (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). The PE standard was visualized with iodine and radioactivity in the band determined.

Transfection

0.5 μg each of pcDNA3 (parental vector), dn PLD1 or dn PLD2 were pre-complexed with Lipofectamine Plus® reagent (Life Technologies) in OPTI-MEM in the absence of antibiotics and serum. Cells were incubated with the constructs for 3 hr at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, after which 1 ml of OPTI-MEM medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin was added to each of the culture dishes. Medium was changed after 6 h, and incubation continued until 48 h.

Transphosphatidylation

Cells were labeled with [14C] palmitic acid (0.25 μCi/ml) for the final 24 h of the incubation with the constructs described above. Cells were washed and then treated with PTH for 30 minutes in DMEM containing 20 mM HEPES, 0.1% BSA, 1% absolute ethanol. To terminate the reaction, media were quickly removed, and 1 ml ice-cold methanol was added to cells. Cells were scraped into chloroform, and lipids extracted using the method of Folch [14]. The extract containing lipids was dried under nitrogen, lipids were re-equilibrated in 100μl CHCl3/CH3OH (9:1), of which 50μl was spotted on a TLC plate, and a 10μl aliquot was used to determine total lipid radioactivity. Phosphatidylethanol (Rf = 0.57) was separated from the total lipid fraction by thin layer chromatography using CHCl3/CH3OH/CH3COOH (70:10:2) as the running solvent. A 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanol standard was run concurrently. Lipids were visualized by exposure to iodine vapor. For autoradiography, TLC plates were incubated at −70°C for 72 h. The phosphatidylethanol bands were scraped and radioactivity determined by liquid scintillation counting. The 14C radioactivity recovered in phosphatidylethanol at the end of the treatments was expressed as the percentage of total 14C lipid radioactivity.

Statistics

The graphs display data from single experiments. For each experiment, unless otherwise indicated in the figure legend, each single treatment was repeated in 3 separate wells, and the means ± SE of the responses to the treatments were calculated. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey post-test [15].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

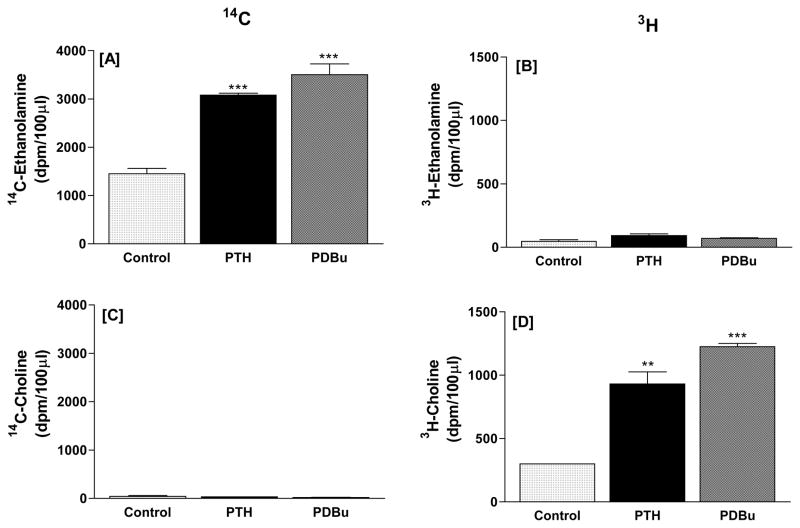

To determine whether both PC and ethanolamine-containing phospholipids were serving as substrates for PLD activity stimulated by the agonists, UMR-106 cells were dual-labeled with [methyl-3H]-choline chloride and [2-14C] ethanolamine hydrochloride and phospholipid hydrolysis assessed as described in Methods. In a experiment designed to test this (Figure 1), media from the incubations were chromatographed to determine whether any of the 3H-choline label appeared in the ethanolamine and conversely, whether any of the 14C-ethanolamine label appeared in the choline. Treating the cells with PTH (10 nM) or PDBu (500 nM) increased medium 14C-ethanolamine (Figure 1A) and 3H-choline (Figure 1D). The labeling was selective, in that there was no significant 3H label in the ethanolamine fraction (Figure 1B) and no significant 14C label in the choline fraction (Figure 1C). For subsequent experiments, media were not fractionated and 14C and 3H used as indicators of ethanolamine-containing phospholipids and PC hydrolysis, respectively.

Figure 1.

PTH (10 nM) and PDBu (500 nM) stimulate the production of labeled ethanolamine (A) and choline (D) from 14C-ethanolamine-labeled (A, B) and 3H-choline-labeled (C, D) phospholipids in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells. Incubation time was 60 minutes. Results are mean and SE of triplicate determinations for each treatment. **p<0.01, ***0.001 vs. respective controls.

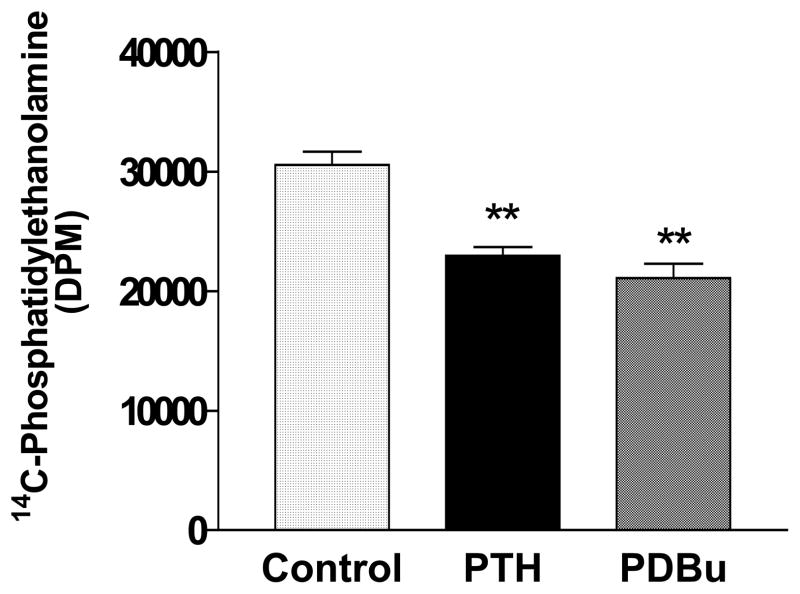

To determine whether PE was hydrolyzed is response to treatment with PTH (10 nM) or PDBu (500nM), 14C-ethanolamine - labeled lipids were separated by thin layer chromatography as described in Methods. Sixty minute treatment with either agonist resulted in a significant decrease in radioactive PE (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PTH (10 nM) and PDBu (500 nM) decrease 14C-phosphatidylethanolamine in UMR-106 cells. Incubation time was 60 minutes. Results are the mean and SE of triplicate determinations for each treatment. **p<0.01 vs. respective controls.

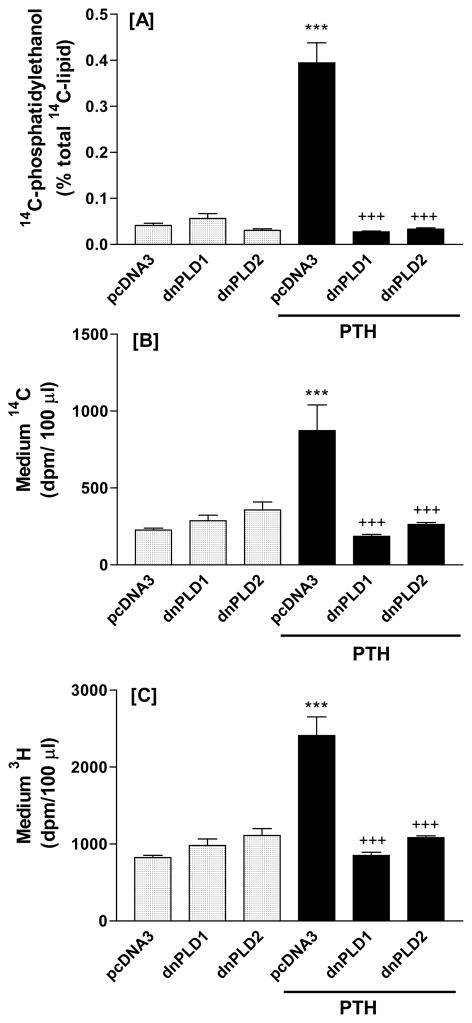

To confirm that the effects on lipid hydrolysis were mediated through PLD, cells were transfected with catalytically inactive constructs of PLD1 or PLD2 that have been used successfully as putative dominant negatives previously [16–18]. Both PLD1 and PLD2 constructs were used, since both isoforms are present in the UMR-106 cells [5]. pcDNA3 served as a control for transfection. Effects of PTH were then determined. Initial experiments were carried out to confirm that the constructs inhibited PTH-stimulated transphosphatidylation. Data from a representative experiment are shown (Figure 3A). The constructs inhibited PTH stimulated hydrolysis of ethanolamine-containing phospholipids (Figure 3B) and phosphatidylcholine (Figure 3C), indicating that the effects on phospholipid hydrolysis were mediated through PLD.

Figure 3.

Dominant negative phospholipase D1 and D2 constructs inhibit PTH-stimulated transphosphatidylation (A) and hydrolysis of ethanolamine-containing phospholipids (B) and phosphatidylcholine (C) in UMR-106 cells. Incubation time was 30 minutes. Results in figure A are the mean and SE of duplicate measurements for each treatment. Results in figures B and C are the mean and SE of triplicate determinations for each treatment. ***p<0.001 vs. pcDNA3; +++p<0.001 vs. PTH.

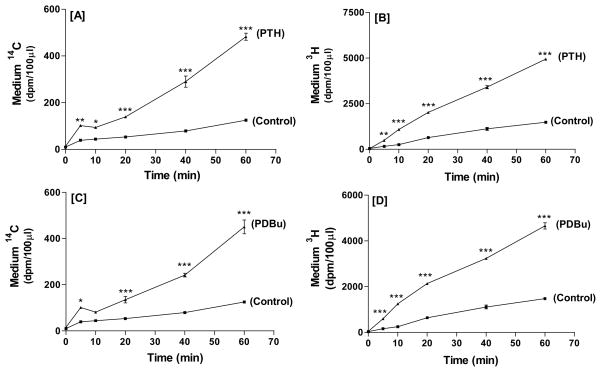

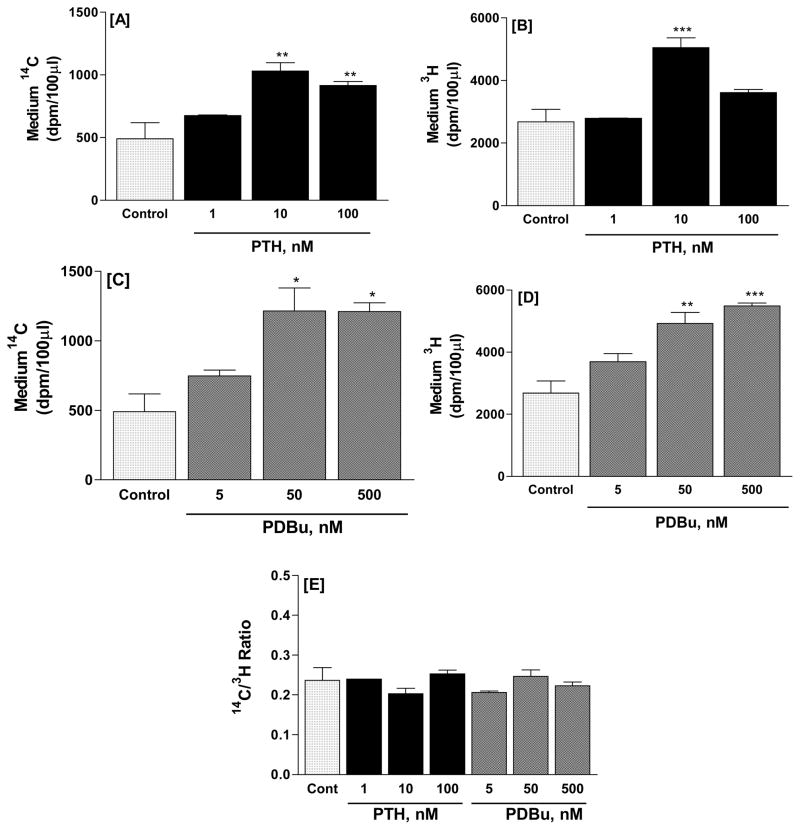

In time course experiments, 10 nM PTH (Figure 4A, B) and 500nM PDBu (Figure 4C, D) elicited significant increases in 14C and 3H radioactivity at time points as early as 5 min. Responses increased progressively and were sustained for up to 60 min. In dose response experiments at the 30-minute time point (Figure 5), effects of PTH on 14C release were maximal at 10 nM, and remained elevated at 100 nM (Figure 5A). PTH (1–100 nM) elicited a biphasic effect on 3H release, with significant effects at 10, but not 100 nM (Figure 5B). PDBu (5–500nM) (Figure 5C, D) elicited dose-dependent increases, with significant stimulation of phospholipid hydrolysis obtained with 50nM PDBu and no further increase with 500 nM. These dose-related effects of PTH and PDBu were replicated in other experiments. The ratios of 14C to 3H were not significantly different in control and treated groups (Figure 5E) indicating that the treatments did not affect the relative rates of 3H-choline and 14C-ethanolamine release.

Figure 4.

Time course of 10 nM PTH- (A, B) or 500 nM PDBu- (C, D) stimulated release of radioactive hydrolysis products from UMR-106 cells dual labeled with 14C-ethanolamine and 3H-choline. Results are mean and SE of triplicate determinations for each treatment. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. respective controls.

Figure 5.

Dose response of PTH (A, B) or PDBu (C, D) effects on the release of radioactive hydrolysis products from UMR-106 cells dual labeled with 14C-ethanolamine and 3H-choline. Incubation time was 30 min. Results are mean and SE of triplicate determinations for each treatment. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. respective controls. The ratio of 14C to 3H radioactivity, which was unaffected by the stimulators, is presented in Fig. 5E.

In view of the emerging role of PLD in signal transduction, it is important to identify the phospholipid pools that can serve as substrates. A number of investigators have reported the hydrolysis of PC by PLD [19]. Although this pathway is well established, it is now clear that in some cells, PE is also a potential source of signaling molecules in cells stimulated with phorbol esters and agonists [20]. Activation of PLD in NIH3T3 fibroblasts by phorbol ester [21], ATP or GTP [22], hormones [23] and oxidative stimuli [24] had been shown to correlate with hydrolysis of PE. The present results, in particular the observation that dominant negative alleles of PLD1 and PLD2 block agonist-stimulated PE hydrolysis, suggest that PE is a direct target for hydrolysis by PLD in response to PTH in UMR-106 cells. PLD1 had been shown previously to hydrolyze PE in vitro with limited efficiency in comparison to PC [9]; this is the first study, however, that links PLD1 and PLD2 action in vivo with PE hydrolysis. PE and PC are differently distributed within the plasma membrane, with PE being more predominant in the inner leaflet [25]. This differential distribution could result in distinct functions being mediated by PC and PE hydrolysis.

In summary, PTH and PDBu stimulated PLD-dependent generation of 3H-choline and 14C-ethanolamine in UMR-106 cells. Effects on phospholipid hydrolysis were time- and dose-dependent. The findings are likely to be relevant to PTH effects in osteoblastic cells. Phospholipid hydrolysis generates the signaling molecules phosphatidic acid and diacylglycerol, and our previous studies have shown that both of these are increased in response to PTH [26]. The current results suggest that PE, in addition to PC, may serve as a phospholipid source of these mediators of downstream signaling in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant from NIH/NIAMS (AR11262) to PHS.

Abbreviations used

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- PDBu

phorbol-12,13-dibutyrate

- PLD

phospholipase D

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

References

- 1.Singh AT, Kunnel JG, Strieleman PJ, Stern PH. Parathyroid hormone (PTH)-(1-34), [Nle(8,18), Tyr34]PTH-(3-34) amide, PTH-(1-31) amide, and PTH-related peptide-(1-34) stimulate phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells: comparison with effects of phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate. Endocrinology. 1999;140:131–137. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.1.6456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Exton JH. New developments in phospholipase D. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15579–15582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDermott M, Wakelam MJ, Morris AJ. Phospholipase D. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:225–253. doi: 10.1139/o03-079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cockcroft S. Signalling roles of mammalian phospholipase D1 and D2. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1674–1687. doi: 10.1007/PL00000805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh AT, Bhattacharyya RS, Radeff JM, Stern PH. Regulation of parathyroid hormone-stimulated phospholipase D in UMR-106 cells by calcium, MAP kinase, and small G proteins. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1453–1460. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh AT, Gilchrist A, Voyno-Yasenetskaya T, Radeff-Huang JM, Stern PH. G alpha12/G alpha13 subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins mediate parathyroid hormone activation of phospholipase D in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2171–2175. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiss Z, Anderson WB. Phorbol ester stimulates the hydrolysis of phosphatidyethanolamine in leukemic HL-60, NIH 3T3, and baby hamster kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1483–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura S, Kiyohara Y, Jinnai H, Hitomi T, Ogino C, Yoshida K, Nishizuka Y. Mammalian phospholipase D: phosphatidylethanolamine as an essential component. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:4300–4304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettitt TR, McDermott M, Saqib KM, Shimwell N, Wakelam MJ. Phospholipase D1b and D2a generate structurally identical phosphatidic acid species in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 2001;360:707–715. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond SM, Altshuller YM, Sung TC, Rudge SA, Rose K, Engebrecht J, Morris AJ, Frohman MA. Human ADP-ribosylation factor-activated phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase D defines a new and highly conserved gene family. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29640–29643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okamoto Y, Morishita J, Tsuboi K, Tonai T, Ueda N. Molecular characterization of a phospholipase D generating anandamide and its congeners. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5298–5305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamoto Y, Morishita J, Wang J, Schmid PC, Krebsbach RJ, Schmid HH, Ueda N. Mammalian cells stably overexpressing N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine-hydrolysing phospholipase D exhibit significantly decreased levels of N-acylphosphatidylethanolamines. Biochem J. 2005;389:241–247. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung TC, Roper RL, Zhang Y, Rudge SA, Temel R, Hammond SM, Morris AJ, Moss B, Engebrecht J, Frohman MA. Mutagenesis of phospholipase D defines a superfamily including a trans-Golgi viral protein required for poxvirus pathogenicity. EMBO J. 1997;16:4519–4530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folch L, Lees M, Stanley GHS. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tukey JW. Comparing individual means in the analysis of variance. Biometrics. 1949;5:99–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitale N, Caumont AS, Chasserot-Golaz S, Du G, Wu S, Sciorra VA, Morris AJ, Frohman MA, Bader MF. Phospholipase D1: a key factor for the exocytotic machinery in neuroendocrine cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:2424–2434. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang P, Altshuller YM, Hou JC, Pessin JE, Frohman MA. Insulin-stimulated plasma membrane fusion of Glut4 glucose transporter-containing vesicles is regulated by phospholipase D1. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2614–2623. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du G, Huang P, Liang BT, Frohman MA. Phospholipase D2 localizes to the plasma membrane and regulates angiotensin II receptor endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1024–1030. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billah MM, Anthes JC. The regulation and cellular functions of phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis. Biochem J. 1990;269:281–291. doi: 10.1042/bj2690281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hii CST, Edwards YS, Murray AW. Phorbol ester-stimulated hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine by phospholipase D in HeLa cells. Evidence that the basal turnover of phosphoglycerides does not involve phospholipase D. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20238–20243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiss Z, Rapp UR, Pettit GR, Anderson WB. Phorbol ester and bryostatin differentially regulate the hydrolysis of phosphatidylethanolamine in Ha-ras- and raf-oncogene-transformed NIH 3T3 cells. Biochem J. 1991;276:505–509. doi: 10.1042/bj2760505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiss Z, Anderson WB. ATP stimulates the hydrolysis of phosphatidylethanolamine in NIH 3T3 cells. Potentiating effects of guanosine triphosphates and sphingosine. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7345–7350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiss Z. Differential effects of platelet-derived growth factor, serum and bombesin on phospholipase D-mediated hydrolysis of phosphatidylethanolamine in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1992;285:229–233. doi: 10.1042/bj2850229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Natarajan V, Taher MM, Roehm B, Parinandi NL, Schmid HH, Kiss Z, Garcia JG. Activation of endothelial cell phospholipase D by hydrogen peroxide and fatty acid hydroperoxide. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:930–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verkleij AJ, Post JA. Membrane phospholipid asymmetry and signal transduction. J Membr Biol. 2000;178:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s002320010009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radeff JM, Singh AT, Stern PH. Role of protein kinase A, phospholipase C and phospholipase D in parathyroid hormone receptor regulation of protein kinase Calpha and interleukin-6 in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells. Cell Signal. 2004;16:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]