Abstract

CD1d-dependent NKT-cells represent a heterogeneous family of effector T-cells including CD4+CD8− and CD4−CD8− subsets, that respond to glycolipid antigens with rapid and potent cytokine production. NKT-cell development is regulated by a unique combination of factors, however very little is known about factors that control the development of NKT subsets. Here, we analyze a novel mouse strain (helpless) with a mis-sense mutation in the BTB-POZ domain of Zbtb7b and demonstrate that this mutation has dramatic, intrinsic effects on development of NKT-cell subsets. Although NKT-cell numbers are similar in Zbtb7b mutant mice, these cells are hyperproliferative and most lack CD4 and instead express CD8. Moreover, the majority of Zbtb7b mutant NKT-cells in the thymus are RORγt+ and a high frequency produce IL-17 while very few produce IFN-γ or other cytokines, sharply contrasting the profile of normal NKT-cells. Mice heterozygous for the helpless mutation also have reduced numbers of CD4+ NKT-cells and increased production of IL-17 without an increase in CD8+ cells, suggesting that Zbtb7b acts at multiple stages of NKT-cell development. These results reveal Zbtb7b as a critical factor genetically pre-determining the balance of effector subsets within the NKT-cell population.

Introduction

The factors that regulate formation of distinct subsets of effector T-cells are not well understood. While these responses are clearly influenced by the nature and route of exposure of an encountered antigen, genetic wiring also influences the kinds of effector T-cell responses. Understanding these genetic factors is important to explain individual variability in physiological or pathological immune reactions to common antigens.

NKT-cells are CD1d-restricted, glycolipid antigen-reactive T-cells that represent a unique population of effector T-cells in mice and humans. These cells express a heavily biased T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire, comprised of an invariant TCR- alpha chain (Vα14Jα18 in mice, Vα24Jα18 in humans) paired with a limited array of TCR-beta chains (Vβ8.2, Vβ7 or Vβ2 in mice, Vβ11 in humans) (1, 2). NKT-cells can influence a broad spectrum of diseases, ranging from suppression of autoimmune diseases like type 1 diabetes, to promotion of immunity to cancer and infection (3). This paradoxical ability to promote or suppress immune responses is associated with the profound ability of NKT-cells to produce a spectrum of cytokines within hours of stimulation. At the population level, NKT-cells produce seemingly antagonistic cytokines including IFNγ, IL4, IL10, IL13 and IL17, although NKT-cells can be divided into functionally distinct subsets that are capable of preferentially producing only some of these cytokines (4-7) which may partly explains the diverse functional outcomes associated with NKT-cells.

Human NKT-cells vary widely in frequency between individuals, yet are stable within individuals (8, 9). Human NKT-cells include CD4+, CD4−CD8− (double negative (DN)) and CD8+ subsets, and each of these exhibit distinct cytokine profiles, which again suggests that they have distinct functions in vivo. The ratio of CD4/CD8 defined subsets of NKT-cells also varies widely between individuals (10). Given this variability, combined with their powerful immunoregulatory potential, it is very important to decipher the factors that regulate NKT-celldevelopment and homeostasis, including factors that determine the balance of functionally distinct NKT-cell subsets.

Many molecules, including cell surface receptors, signal transduction and transcription factors, have been identified that selectively regulate NKT-cell numbers independently from conventional T-cells (11). For example, the SLAM/SAP/fyn signalling pathway is selectively important for NKT-cell development while dispensible for T-cell development in the thymus (11). However, little is known about what regulates the differentiation of NKT-cell subsets. One study, an investigation of NKT-cell development in GATA-3 KO mice, provided data showing that CD4+ NKT-cells were preferentially inhibited in the absence of this factor (12). What factors regulate the appropriate expression of the CD4 or CD8 co-receptors in MHC class II or I restricted thymocytes has itself been a long-standing issue. In 2005 two papers showed that the transcription factor Zbtb7b (previously called Th-POK and cKrox) plays a key role in maintaining CD4 expression in MHC class II restricted thymocytes (13, 14). Zbtb7b promotes CD4 expression indirectly by preventing Runx1- and Runx3-mediated downregulation of CD4 in conventional TCRαβ T-cells (15). It has been shown subsequently that CD4 expression by NKT-cells is also dependent on Zbtb7b (16, 17). Furthermore, in the absence of Zbtb7b, NKT-cell cytokine production was impaired, which led to the suggestion that Zbtb7b is required for full NKT-cell maturation and activation (16).

In this study we describe a novel mouse strain, termed ‘helpless’, carrying a point mutation in Zbtb7b creating a single amino acid substitution in the BTB-POZ domain. Using this mouse model, we show that Zbtb7b plays an essential, cell intrinsic, and dose-dependent role in establishing the balance of different NKT-cell subsets, including maintenance of CD4, inhibition of CD8 expression and development of the RORγt+ IL-17+ population of NKT-cells. Zbtb7b thereby establishes a genetically predetermined profile of CD1d-restricted NKT-cells.

Material and Methods

Mice

The Zbtb7bhpls/hpls strain derived from a C57BL/6 male treated 3 times intraperitoneally with 100 mg/kg N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea at weekly intervals. Mice were maintained on a pure C57BL/6 background or on a mixed CBAxC57BL/6 background. All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at the Australian Phenomics Facility. All experimental procedures were approved by the ANU Animal Ethics and Experimentation Committee.

Sequencing and genotyping

All exons and splice sites of Zbtb7b were amplified and Primers for sequencing were designed using Australian Phenomics Facility (APF) software to amplify all exons and splice sites for Zbtb7b. The amplification and dual sequence run were performed at the Brisbane node of the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF). Sequence analysis was conducted at the Australian Phenomics Facility using Lasergene software (DNAStar). A T to G substitution of bp 480 was identified in exon 2 (ensmuse000001765423) of Zbtb7b, resulting in a CTG (Leu) to a CGG (Arg) amino acid change. Mice were genotyped using an Amplifluor assay (Chemicon). All primer sequences are available on request.

Flow Cytometry

Cell suspensions from thymus and spleen were prepared by passing the cells through a cell strainer (BD) or stainless steel sieve, followed by lysis of red blood cells for spleen and liver samples. Liver lymphocytes were isolated by centrifugation over a percoll gradient. Cell suspensions were labelled with fluorochrome-coupled antibodies according to standard protocols and run on a LSR II or Canto flow cytometer (BD) followed by analysis with FlowJo (Treestar). α-GalCer-loaded CD1d-tetramers were produced in house, using a mouse CD1d baculovirus construct originally provided by Prof. Mitchell Kronenberg, as previously described (18). For some experiments α-GalCer (PBS57)-loaded CD1d tetramers provided by the NIH Tetramer facility were used.

In vitro stimulation and cytokine analysis

For the intracellular cytokine staining assay, cells were stimulated with 50ng/mL phorbol ester and 500ng/mL ionomycin for 2.5-3.5 hours at 37°C in the presence of monensin in RPMI culture media supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FCS, glutamine (GIBCO), 10mM sodium pyruvate (GIBCO), 10mM HEPES (GIBCO), 10mM MEM non essential amino acids (GIBCO) and 5.5μM 2-ME. Stimulated cells were then washed, stained for surface markers and stained intracellularly using FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IL-17A (Biolegend) or isotype-matched control antibodies (BD Pharmingen), RORγt-PE or APC (eBioscience) using the eBioscience fixation/permeabilisation kit.

For cytometric bead array, thymocytes were pooled from several mice per group and enriched by either staining with anti-CD24 (J11D) followed by depletion using rabbit complement (C-SIX Diagnostics) in the presence of DNase (Roche Diagnostics) or by staining cells with phycoerythrin (PE) -conjugated CD1d-αGalCer tetramer and subsequent incubation with anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Labeled cells were then enriched by passing them through a magnetic column and were further stained for flow cytometric purification. This second method was also used to enrich splenic dendritic cells (based on CD11c expression). Enriched cells were sorted using a FACSAria (BD) in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology flow cytometry facility, University of Melbourne, to obtain highly purified populations. Sorted NKT cells were stimulated placing in 96 well plates coated anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, or soluble CD1d loaded withα–GalCer or by co-culture with sorted splenic dendritic cells loaded with α–GalCer. After 24 hours the supernatant was collected and the concentration of cytokines secreted into the medium determined by cytometric bead array (BD-Pharmingen).

Cell sorting, RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative PCR

Single cell suspensions from thymocytes were prepared and stained as for flow cytometric analysis. Samples were sorted on a BD FACSAria sorter at the Flow Cytometry facility in JCSMR, ANU. Total RNA was extracted using RNA Trizol reagent (Molecular Research Centre Inc), and reverse transcribed using oligo(dT) primers and 50 U Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) as detailed in the manufacturer’s guidelines. SYBR Green RealTime PCR reactions were performed in 96 well plates (PerkinElmer, MA, USA) with an ABI PRISM 7900 Real-Time System (Perkin Elmer/PE Biosystems) at the Biomolecular Resource Facility (JCSMR, ANU). To correlate the threshold (Ct) values from the cDNA amplification plots to fold differences between samples, the ΔΔCt method was applied using the housekeeping gene GAPDH.

Generation of BM chimeras

B6.SJL CD45.1 mice were irradiated with 10 Gy and injected with 2 × 106 bone marrow cells consisting of a 50:50 mix of WT B6.SJL CD45.1+ and either WT or mutant C57BL/6 (CD45.2+) cells. They were allowed to reconstitute for 8 weeks before analysis.

Results

Identification of the Zbtb7b mutant strain helpless (hpls)

In a genome-wide screen for N-ethyl-N-nitrosurea-induced point mutations affecting the development of the immune system (19), we identified a strain that was deficient in CD4+ T-cells in peripheral blood and spleen. Further analysis revealed a block in CD4 development at the CD4+ CD8dim stage in the thymus (Figure 1A). This phenotype is identical to the phenotype described for the HelperDeficient (HD) strain caused by an amino acid substitution in the DNA-binding zinc finger domain of the transcription factor Zbtb7b, previously called Th-POK or cKrox (13, 20) or knockout mice with a Zbtb7b null allele (21). Because of these similarities, we sequenced Zbtb7b and identified a mutation changing a conserved Leucine to Arginine in the BTB-POZ domain (Figure 1B). BTB-POZ domains mediate homodimerization and heterodimerization, association with nuclear co-repressors, and ubiquitination (22). Deletion of the BTB-POZ domain from a Zbtb7b transgene inactivated its ability to deviate MHC class I-restricted T-cells into the CD4 lineage (14). The leucine that is mutated in helpless mice is buried within the homologous PZLF BTB-POZ domain (Supplementary Figure 1 and 23). The Zbtb7bL102R disrupts CD4 cell differentiation as completely as the null mutation but whether this reflects mis-folding of the BTB domain or destabilization of the Zbtb7b protein as a whole, or loss of particular protein-protein interactions is unclear. Genotyping of affected and unaffected progeny from numerous helpless carriers confirmed that the failure of CD4 cell differentiation was inherited in complete concordance with the Zbtb7b mutation in a recessive fashion. As noted previously for the HD strain (24), homozygous affected mice on the parental C57BL/6 background were born at around half the expected frequency and affected mice showed poor breeding efficiency. This was rescued by keeping the mice on a mixed C57BL/6 × CBA background, where homozygotes were obtained at Mendelian ratios. The embryonic lethality on the C57BL/6 background may indicate essential functions for Zbtb7b in other processes such as collagen gene regulation (25).

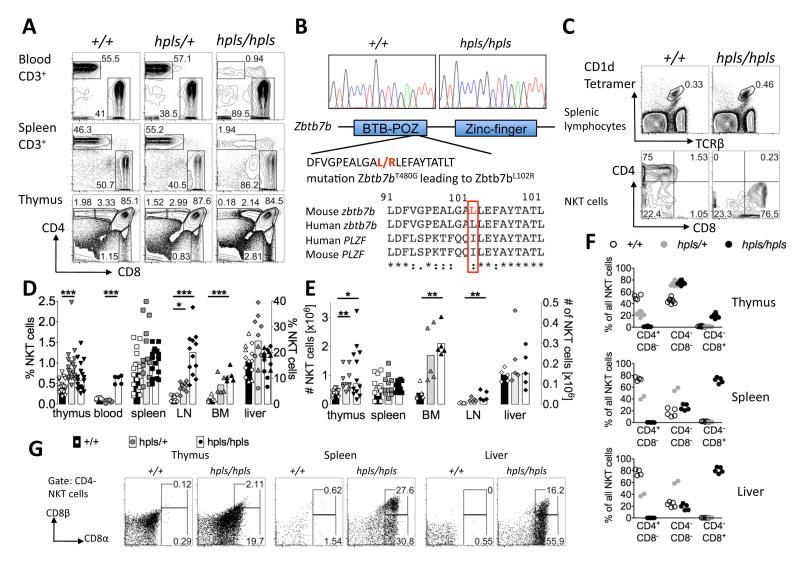

Fig 1. CD8+ NKT-cells predominate in a Zbtb7b mutant mouse strain.

A: Homozygotes for the helpless mutation (hpls/hpls) have reduced percentage of CD4+ T-cells in the peripheral blood and spleen and a block in thymic T-cell development at the CD4+ CD8dim stage. B: T480G mutation in Zbtb7b exon 1, altering codon 102 from leucine to arginine within the BTB-POZ domain. The bottom panel shows an alignment of parts of the BTB-POZ domains from the indicated proteins, with the mutated residue highlighted in red. C: Flow cytometric analysis of spleen cells stained with α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers and antibodies to TCR, CD4, and CD8. Numbers in the upper panel show percentage of spleen cells within the gate, and lower panels show the percentage of these gated NKT-cells that are CD4+, CD8+ or negative for both. D: Percentage of NKT-cells in thymus, blood, spleen, lymph node, bone marrow (left axis) and liver (right axis) of Zbtb7bhpls/hpls, Zbtb7bhpls/+ and Zbtb7b+/+ mice. Each datapoint represents a different mouse and the bars represent the mean. The data for the percentages and absolute cell numbers of NKT-cells in thymus, spleen and liver are pooled from at 2 (liver and bone marrow) or more different experiments with some animals for the liver data on a mixed CBAxC57BL/6 background. Mixed background mice are depicted with hexagons, pure B6 mice are depicted with triangles. E: Absolute cell number of NKT-cells in thymus, spleen, bone marrow (left axis) and lymph node (LN) and liver (right axis) of Zbtb7bhpls/hpls, Zbtb7bhpls/+ and Zbtb7b+/+ mice. Each datapoint represents a different mouse and the bars represent the mean. The percentage of CD4 and CD8-defined NKT-cellsubsets within thymus, spleen and liver. Each datapoint represents a different mouse. F: Expression of CD8α and CD8β chains on CD4-negative NKT-cells from wild-type and mutant mice in thymus, spleen and liver. Except for liver data for hpls/+ mice all flow cytometric data representative of at least 3 different experiments with at least 2 animals per genotype and experiment. Statistics were calculated using the Kruskal-Wallis test with * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.005 and *** = p < 0.0005.

It was previously reported that CD4 expression by NKT-cells is disrupted in ThPOK deficient mice (16, 17), so we first investigated whether the Zbtb7b point mutation in hpls/hpls micehad a similar impact on these cells. Normally, around 70% of spleen NKT-cells express CD4 and none are CD8+. In the helpless strain, this was completely reversed with approximately 70-80% of NKT-cells in the spleen expressing CD8 and none were CD4+ (Figure 1C).

Examination of NKT-cells in different tissues revealed that the percentage in thymus, spleen and liver was comparable between wt and hpls/hpls mice, whereas the percentages and absolute cell numbers of these cells in blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes were clearly higher (Fig 1D and E). Interestingly, Zbtb7b heterozygous mice also showed an increased percentage of NKT-cells in thymus, lymph node and bone marrow, but not in spleen and liver (Fig 1D). The CD8+ NKT-cell phenotype was detectable in thymus of hpls/hpls mice (approximately 20% CD8+) but far more pronounced in the spleen andliver where approximately 80% were CD8+ (Fig 1F). Further analysis of the CD8+ NKT-cells in thymus, spleen and liver showed that they included some cells that were CD8α+β− and some that were CD8α+β+ (Fig 1G). Furthermore, heterozygous hpls/+ mice exhibited an intermediate phenotype, where CD4+ NKT-cells were reduced, yet there was no sign of CD8 upregulation, in both thymus and periphery, thus hpls/+ mice were highly enriched for CD4−CD8− NKT-cells (Figure 1F). This contrasts with the development of conventional CD4+ T-cells that is seemingly unaffected in heterozygous mice (Figure 1A) strongly suggesting that the effect on NKT surface marker expression is not due to a dominant-negative effect of the hlps mutation.

NKT-cell development is abnormal in Zbtb7b mutant mice

The developmental events giving rise to the unusual CD8+ NKT-cell phenotype in Zbtb7b mutant mice have not been determined, however, the accumulation of these cells in peripheral tissues at much higher levels than thymus suggested this occurs as a late event in NKT-cell development. Therefore, we more carefully examined NKT-cells in the thymus to determine the origins of this defect. Analysis of Zbtb7b mRNA expression by real time PCR revealed that both immature NK1.1− and mature NK1.1+ NKT-cells expressed Zbtb7b (data not shown). Zbtb7b expression levels were similar to CD4+CD8dim thymocytes, lower than total CD4+ SP thymocytes, but clearly above DP and CD8 SP thymocytes that have expression at or just above background (13). Because NKT-cell numbers in the thymus of Zbtb7b mutant mice were comparable to those in wt mice, this suggested there was no major problem with the selection and expansion of these cells as a total population. NKT-cell development can be divided into three developmentally distinct stages: Stage 1 (CD44loNK1.1−); Stage 2 (CD44+NK1.1−); Stage 3 (CD44+NK1.1+) (26, 27) and these stages can be further divided into CD4+ and CD4−, a split that occurs at approximately stage 2 (4). While hpls/hpls NKT-cells were mostly mature, as defined by their NK1.1+CD44hi phenotype, they expressed slightly lower levels of NK1.1 (Figure 2A). While CD8+ NKT-cells were detected inthe hpls/hpls thymus, the high intensity CD8 expression observed with hpls/hpls peripheral NKT-cells (Figure 1C) was not reflected in the thymus where they were mostly CD8 low. This suggested that the emergence of CD8+ NKT-cells begins in the thymus but is not fully manifested until these cells are in the periphery. Examination of increasingly mature NKT-cell subsets revealed that low CD8 expression was detectable from the earliest CD44loNK1.1− stage, but the percentage of CD8+ cells increased as the NKT-cells matured through CD44+NK1.1− and CD44+NK1.1+ stages (Figure 2A and 2B).

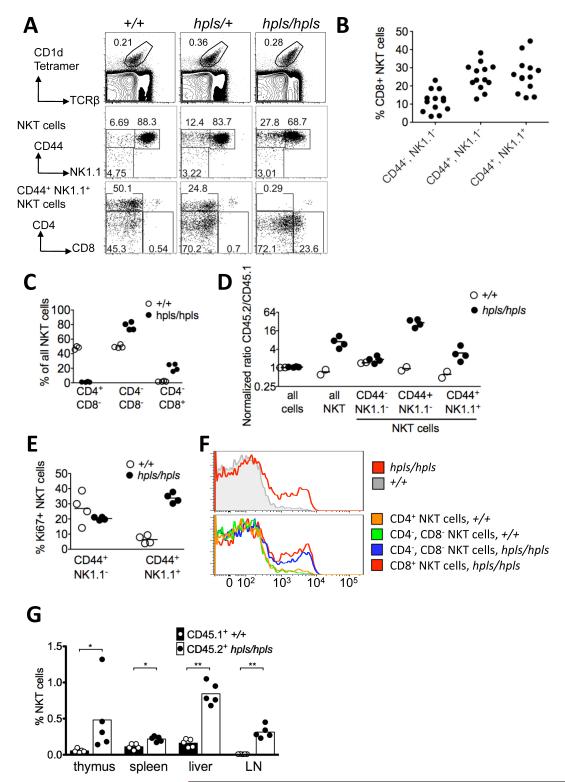

Figure 2. Divergent NKT-cell development in the thymus of Zbtb7b mutant mice.

A: Thymic NKT-cells, gated on α-GalCer-CD1d tetramer+ and TCRβ+ cells, showing subsets resolved by CD44 and NK1.1 expression. The bottom panels are further gated on CD44+ NK1.1+ mature NKT-cells, showing CD4 and CD8 expression. B: The percentage of CD8+ NKT-cells within each stage of hpls/hpls NKT-cell maturation in the thymus, as shown in A (second row). Each symbol represents an individual mouse, data is from at four independent experiments with 2-4 mice per group. C: Mixed bone marrow chimera results showing relative percentage of CD4/CD8 defined NKT-cell subsets in thymus. Each symbol represents a different recipient mouse in a single experiment. Equal mixtures of CD45.1 marked +/+ bone marrow and either CD45.2 hpls/hpls bone marrow (filled circles) or CD45.2 +/+ bone marrow (open circles) were used to reconstitute irradiated CD45.1 recipients. After hemopoietic reconstitution, thymocytes of individual animals were analysed by flow cytometry to identify NKT-cells subsets from either wt or hpls bone marrow origin. D: Relative contribution of hpls/hpls and wild-type cells to the stages of NKT-cell maturation in mixed bone marrow chimeras, generated as described in C and the ratio of CD45.2+ cells to CD45.1+ cells within each subset calculated. To account for small inter-individual differences in overall hemopoietic reconstitution, the CD45.2:CD45.1 cell ratios in NKT-cell subsets of each animal were normalized by dividing by the ratio in DP thymocytes in the same mouse. E: Percentage of NKT-cells staining for the cell cycle marker Ki67 in individual mixed bone marrow chimeras, gated on CD45.2+ hpls/hpls cells (filled circles) or CD45.1+ wild-type cells in the same thymus (open circles). F: Flow cytometric histograms of Ki67 staining in all thymic NKT-cells (top panel) or in the indicated NKT-cell subsets (bottom), showing concatenated data for hpls/hpls and wild-type cells in the thymus from all 4 mice shown in Figure E. G: Percentage of NKT cells in the indicated organs in mixed bone marrow chimeras analysed separately for CD45.1+ +/+ and CD45.2+ hpls/hpls cells. Statistics were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test, with * = p < 0.05 and ** = p < 0.005.

To determine whether the defects in NKT-cell development in hpls/hpls mice were cell intrinsic, we performed mixed bone marrow chimera experiments in order to compare wt and hpls/hpls NKT-cells developing in the same environment. These results demonstrated that the CD4−CD8+ phenotype was indeed cell intrinsic (Figure 2C) and also indicated that hpls/hpls NKT-cells had a competitive developmental advantage as can be seen by a higher ratio of these cells as a total population (Figure 2D). Analysis of the maturational stages revealed that this bias was not detected at stage 1 of NKT development (CD44−NK1.1−) but was first apparent at stage 2 (CD44+NK1.1−) and maintained at stage 3 (CD44+NK1.1+) of NKT-cell development (Figure 2D). This bias toward hpls/hpls NKT-cells with maturation appeared to be at least partly due to hyperproliferation of stage 3 cells, as indicated by high frequency staining with Ki67 compared to the resting state of the corresponding WT-cells in the same thymus (Figure 2E). The highest level of Ki67 staining was associated with the CD8+ NKT-cell fraction (Fig 2F). Thus, these data demonstrate that Zbtb7b plays an intrinsic role in the regulation of NKT-cell development that seems to be first manifest after positive selection in the thymus as these cells begin to mature (stage 2). Analysis of NKT cells in the peripheral tissues of mixed bone marrow chimeras showed that the hpls/hpls NKT cells had a cell-intrinsic competitive advantage in all analysed organs including thymus, spleen, liver, and LN (Figure 2G).

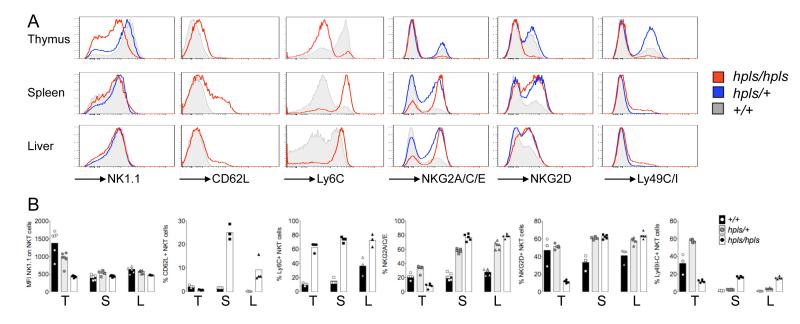

Other cell surface markers including CD62-L and NK cell receptors Ly6C, NKG2A/C/E, Ly49C/I and NKG2D were also differently expressed by the NKT-cells in hpls/hpls mice (Figure 3). The lower levels of NK1.1 observed on thymic hpls/hpls NKT-cells was not observed on hpls/hpls NKT-cells from spleen or liver. Similarly, hpls/hpls NKT-cells also had lower levels of Ly6C and the NKG2 receptors in the thymus, but higher levels in spleen and liver compared to wildtype NKT-cells. Mutant NKT-cells also tended toward higher expression of CD62-L, especially in spleen, possibly explaining the increased percentage of NKT-cells observed in LN of hpls/hpls mutant mice.

Figure 3. Altered expression of surface markers on NKT-cells of Zbtb7bhpls/hpls mice.

A: Expression of the indicated surface markers and inhibitory and activating NK receptors on NKT-cells in the thymus, spleen and liver was measured by flow cytometry. Histograms show concatenated samples from all mice shown in panel B.

B: Each dot represents an individual mouse, the bar graph shows the mean of all samples. T, S and L denotes Thymus, spleen and liver respectively.

Zbtb7b mutant NKT-cells preferentially develop into an IL-17 producing subset

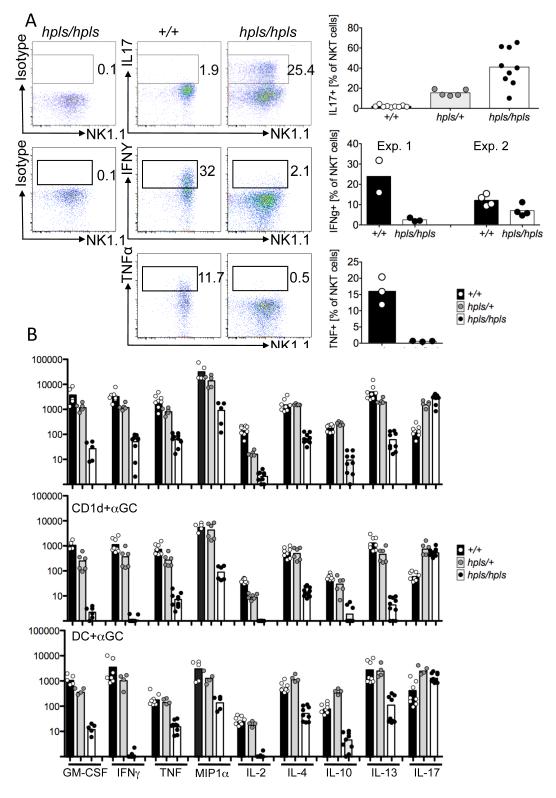

A recent study (16) suggested that NKT-cells from Zbtb7b deficient mice were functionally impaired with much lower cytokine production compared to their WT counterparts, which was surprising given their otherwise mature phenotype. Our findings were consistent with this for the cytokines previously tested (IFNγ, IL-4), Analysis of cytokine production by these cells, using intracellular cytokine staining following in vitro stimulation, revealed that very few mutant NKT-cells produced IFNγ or TNF whereas a high proportion of NKT-cells produced IL-17, which was the opposite of wt NKT-cells (Figure 4A). Given that hpls/hpls NKT-cells clearly were functional and capable of cytokine production, we used cytometric bead array to more comprehensively test cytokine production by these cells. Purified NKT-cells were stimulated in three different ways: plate-bound CD3 and CD28; plate-bound CD1d loaded with αGalCer; or spleen-derived dendritic cells loaded with αGalCer, and supernatants harvested after 24 hours. This revealed that cytokine production by hpls/hpls NKT-cells, with the exception of IL-17, was drastically reduced, to the extent that many cytokines were near or below the detection limit (Figure 4B). In some experiments, we also compared DN and CD8+ NKT-cells from hlps/hpls mice and observed similar cytokine production regardless of the expression of CD8 (data not shown) suggesting that Zbtb7b acts at multiple levels on NKT-cell development. This suggests that Zbtb7b is important in regulating the developmental balance of IL-17-producing NKT-cells, which have recently been identified as a distinct subset of NKT-cells (known as NKT-17 cells), that make lower amounts of other cytokines and have unique functions in vivo (4, 7).

Figure 4. Altered cytokine production by thymic Zbtb7b mutant NKT-cells.

A Thymocytes from Zbtb7b mutant and wild-type mice were activated for 2.5h with PMA and Ionomycin and stained for surface markers followed by intracellular staining with antibodies to IL17, IFNγ and TNF or with isotype control antibodies. All plots are gated on NKT-cells (TCRβ+, αGalCer-CD1d-tetramer+). Gates for cytokine-producing cells were set on isotype control stains, and the numbers show the percentage of NKT-cells within these gates. Data for IL17 is from 3 different experiments on a pure C57BL/6 background. Data for IFNγ production is from two independent experiments, with mice used in experiment 1 from a pure C57BL/6 background, while mice for experiment 2 were on a mixed CBAxC57BL/6 background. B Sorted thymic NKT-cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, plate-bound CD1d and αGalCer or sorted splenic dendritic cells and αGalCer. After 24 hours the supernatant was assayed for the concentration of the indicated cytokines, determined by a cytometric bead array. Concentrations are in pg/ml, represented on a logarithmic scale. Values below 1pg/ml were given a baseline value of 1. The results are derived from four to ten separate cultures collected over two to three independent experiments. Bars depict mean of all samples collected.

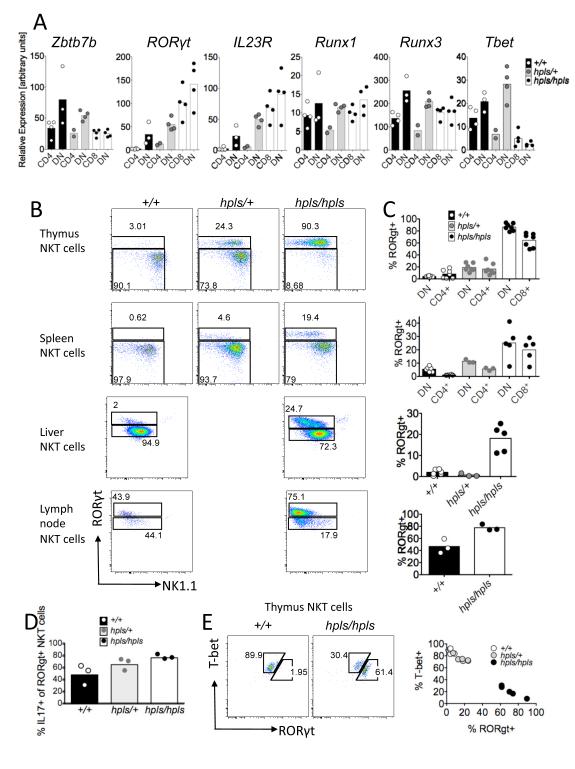

IL-17-producing hlps/hlps NKT-cells are RORγt+

The production of IL-17 is usually dependent on the transcription factor RORγt (28) and previous studies showed that IL-17 producing NKT-cells express RORγt and the receptor for IL-23 (4, 7, 29). To test whether hpls/hpls NKT-cells over-express either of these molecules, we performed real-time PCR for IL-23R and RORγt and found both to be increased in hpls/hpls NKT-cells (Figure 5A). The hpls/+ heterozygous mice showed a small increase in expression compared to the WT NKT-cells. We also tested for the transcription factors Runx1 and Runx3 that have been shown to play an important role in the regulation of CD4 and CD8 co-receptor expression in conventional T-cells (30) and the transcription factor Tbet which is essential for progression from the NK1.1− to the NK1.1+ stage of NKT development (31). No clear difference was observed for Runx1 and Runx3 expression, but expression of Tbet was approximately 3-fold reduced in the hpls/hpls mutant NKT-cells. RT-PCR is unable to distinguish between an increased frequency of positive cells and increased expression per cell. To directly test for this, and simultaneously determine if the increased expression of IL-17 in Zbtb7b mutant NKT-cells coincides with RORγt expression, NKT-cells from +/+, hpls/+ and hpls/hpls mice were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin and intracellular staining used to assess RORγt and IL-17 expression by flow cytometry. This revealed that approximately 80% of the mutant NKT-cells in the thymus were positive for RORγt and approximately 2/3 of those produced IL-17 (Figure 5B, C and D). For spleen-derived NKT-cells, the percentage of RORγt+ NKT-cells was 20% in the hpls/hpls animals and again, approximatelytwo-thirds of these produced IL17. In contrast, wt NKT-cells were only 3-8 % RORγt+ whereas heterozygous mice showed an intermediate phenotype with around 20% of NKT-cells in thymus expressing RORγt (Figure 5C and D). Analysis of NKT cells in the thymus and liver of mixed bone marrow chimeras showed that the increased expression of RORgt and production of IL17 in hpls/hpls NKT cells was cell intrinsic (Supp Figure 3). Interestingly, the RORγt+ NKT-cells had a lower expression of NK1.1 than RORγt− NKT-cells (Figure 5B). Since this is similar to IL-17 producing NKT cells (NKT-17 cells) in wild-type mice (4, 7), this most likely does not reflect a specific effect of the mutant Zbtb7b protein on NK1.1 expression, but rather the predominance of an NK1.1low IL-17 producing NKT subset with a specific phenotype. This interpretation is also supported by the mutually exclusive expression of the transcription factors Tbet and RORγt as observed by dual labelling of NKT-cells (Figure 5E) and the expression of IL-23R by hlps/hlps NKT cells (Figure 5A), which is also a marker of NKT-17 cells in WT mice (7, 29). To further explore this possibility we examined hlps/hlps NKT cells for CD103 and CCR6 expression because high expression of these markers is associated with NKT-17 cells in LN (32). Indeed, we found that RORγt+ LN NKT subset from both WT and hpls/hlps mice were CD103hi and CCR6hi, whereas the RORγt− NKT subsets were heterogeneous for these markers (Supp fig 2). This is consistent with the previous study where IL-17 was only produced by a subset of CD103hi, CCR6hi and RORγthi LN NKT cells (32).

Figure 5. RORγt expression in Zbtb7b mutant NKT-cells.

A: Expression of Zbtb7b, RORγt, IL23R, Runx1, Runx3 and Tbet mRNA in sorted thymic NKT-cells from Zbtb7b mutant, heterozygous and wild-type mice was measured by RT-PCR. B and C: Thymocytes and splenocytes from Zbtb7b mutant and wild-type mice were activated for 3 hours in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Pharmingen) with PMA and Ionomycin and stained for surface markers followed by intracellular staining with antibodies recognising IL-17 and the transcription factor RORγt. All plots are gated on NKT-cells (TCRβ+ or CD3+, PBS57-CD1d-tetramer+). B shows representative FACS plots, C shows the percentages of RORγt+ NKT-cells in thymus, spleen, liver and lymph node. Data are representative of two (thymus, liver and spleen) or one (lymph node) experiments with 2-5 mice (C57BL/6 background) per group. Data for heterozygous mice for spleen and liver are from a single experiment. D shows the percentage of IL-17+ cells out of all RORγt+ NKT-cells in the thymus. E shows the relative expression of RORγt+ and T-Bet in individual NKT-cells.

Taken together, the findings in this study strongly suggest that NKT cell lineage decisions, and specifically the ratio of NKT-17 cells to other NKT cells, is intrinsically regulated by the transcription factor Zbtb7b.

Discussion

While several factors have been identified that control NKT-cell numbers (33), there is little understanding of what controls the development of distinct subsets of NKT-cells. Herein, we demonstrate that although Zbtb7b is not required for the development of normal numbers of NKT-cells, it plays a critical role in genetically predetermining their differentiation into different subsets defined by patterns of cell surface markers and cytokine production.

It has been appreciated, almost since their discovery, that NKT-cells in mice and humans can be divided into subsets based upon CD4 and CD8 expression. Furthermore, there are clear differences in cytokine production by CD4+ and CD4− subsets of human NKT-cells, where CD4+ cells produced both Th1 and Th2 type cytokines, while CD4− NKT-cells produced predominantly Th1 type cytokines (5, 6). Moreover, human CD8+ NKT-cells may also be functionally distinct from CD4+ and DN NKT-cells (34). Thus, the cell surface phenotype of NKT-cells appears to correlate with important functional diversity. While it is also clear that mouse NKT cells include diverse subsets defined by cell surface markers including CD4, there are some important distinctions with human NKT cells. There is no clear difference in cytokine production between mature mouse CD4+ and CD4− NKT-cells, both can make Th1 and Th2 type cytokines (4). Also, mouse NKT-cells do not normally include a population of CD8+ cells. However, mouse NKT-cells can be subdivided into functionally distinct subsets based on the expression of NK1.1 and NK1.1- mouse NKT-cells produce a distinct array of cytokines compared to NK1.1+ NKT-cells, including higher IL-4 and lower IFNγ (4). Of particular interest, a subset of CD4−NK1.1− mouse NKT-cells predominantly produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 but not other cytokines (4, 7). This subset is thought to represent a distinct lineage of NKT-cells, whose development depends on the transcription factor RORγt (4, 7, 35). The production of IL-17, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, imbues this subset of NKT-cells with markedly different functional potential. IL-17-producing NKT-cells have been associated with induction of airway neutrophilia (7), ozone induced airway hyper-reactivity (36), and collagen-induced arthritis (a model for rheumatoid arthritis) in mice (37). It is also likely, given the unique functions of IL-17 in autoimmunity and anti-microbial immunity (38), that IL-17-producing NKT-cells will have different functions from non-IL-17-producing NKT-cells in other disease settings.

In contrast to normal wt mice, Zbtb7b mutant mice lack CD4+ NKT-cells and instead harbour a population of CD8+ NKT-cells (16, 17). Furthermore, antigenic stimulation of these cells revealed a major defect in IL-4 and IFN-γ production, which led to the suggestion that these cells were functionally hypo-responsive to TCR stimulation (16). However, IL-17 was not tested in that study, and our findings present a very different interpretation for the role of Zbtb7b in NKT-cell development, showing that although these cells are deficient in IFNγ and IL-4 as published (16), they are clearly capable of producing high levels of IL-17. Moreover, IL-17 producing Zbtb7b mutant NKT have lower levels of NK1.1, they express high levels of RORγt and IL23R, which also closely aligns them with IL-17+ NKT-cells in wt mice. Furthermore, both CD8− and CD8+ NKT-cells in Zbtb7b mutant mice produced IL-17, indicating that the CD8 phenotype is not directly related to the altered cytokine profile and may reflect multiple developmental checkpoints that are controlled by Zbtb7b. Our data suggest that the NKT-17 lineage may be a default-pathway for NKT-cell development and that Zbtb7b is a key transcription factor that drives the development of other phenotypically and functionally distinct NKT-cell subsets. In support of this, Tbet, a transcription factor that is known to be critical for maturation of IFN-γ producing NK1.1hi NKT-cells (31) was present at much reduced levels in Zbtb7b mutant NKT-cells. At present it is unclear if Zbtb7b regulates the balance of development of these NKT-cell subsets by directly binding to the Rorc gene to influence expression of RORγt, or if Zbtb7b somehow affects signalling through Stat3, another transcription factor required for the development of IL-17 producing T cells (39). Further studies including Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays are required to differentiate between these possibilities but given the dramatic functional difference between NKT-17 cells and other NKT-cells, identification of Zbtb7b as a major switch factor represents an important step towards being able to control NKT-cell function.

The developmental and functional basis for CD4 and CD8 coreceptor expression by NKT-cells has been a long-standing puzzle in the field. Because NKT-cell TCRs are CD1d restricted, there is no obvious role for CD4 or CD8 in binding to MHC class II or MHC class I respectively, nor is it clear how or why these molecules are modulated during NKT-cell development. Our data using ‘helpless’ Zbtb7b mutant mice sheds new light on this problem, demonstrating that Zbtb7b is critical for development and/or maintenance of CD4+ NKT-cells, but it also inhibits the emergence of CD8+ NKT-cells. This seems to be regulated at multiple levels in a dose-dependent manner, because hpls/+ mice have diminished CD4+ NKT-cells but do not have increased CD8+ NKT-cells. The altered ratio of CD4+ and CD8+ NKT-cells may be at least partly related to proliferative differences in the thymus, where mutant NKT-cells that are DN and CD8+ proliferate at a higher rate than wt CD4+ or DN NKT-cellsand our analysis of mixed bone marrow chimeras shows that this effect is cell intrinsic. However, proliferation is unlikely tofully explain the differences because CD8+ NKT-cells are simply non-existent in the periphery of normal wt mice. Importantly, our study demonstrates that CD8 is gradually acquired by Zbtb7b mutant NKT-cells, rather than a failure to down-regulate this surface marker following NKT-cell selection from DP precursors in the thymus. This is further supported by the fact that many of these cells are CD8α+CD8β− in contrast to DP thymocytes that express both CD8α and CD8β. An early study demonstrated that forced (transgenic) expression of CD8 by all T-cells resulted in depletion of NKT-cells (40), which suggested that mouse NKT-cells that express CD8 are deleted in the thymus, perhaps due to enhanced signalling via CD8 resulting in negative selection. However, a more recent publication showed that thymocytes from homozygous CD8 transgenic mice have a shorter lifespan which impacts on their ability to undergo distal TCR Vα-Jα gene rearrangements (16). This makes secondary TCR rearrangements, required to incorporate distal TCR-Jα genes such as Jα18 into the TCR-α chain (41-44), less likely. This study also demonstrated that CD8 does not detectably bind to CD1d (16). Thus, the conclusion most consistent with our data is that Zbtb7b is normally activated at a very early stage in NKT-cell development and in the absence of this transcription factor, CD8 expression is re-acquired during NKT-cell maturation. This is an intriguing considerationin light of the existence of human CD8+ NKT-cells. In future, it will be important to determine whether human CD8+ NKT-cells have lower amounts of Zbtb7b and express RORγt.

The regulation of CD4 expression by conventional αβ T-cells involves binding of Runx1 and 3 to the Cd4 silencer at the different stages during their development to suppress the expression of CD4 at the DN stage of thymic development or in CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells (45). Furthermore, the expression of Zbtb7b in CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells is silenced by Runx proteins (46) and Runx1 has also been shown to enhance the expression of CD8 by cytotoxic T-cells (41). But consistent with previous reports showing an essential role for Runx1 in the development of NKT-cells (41), we observed a comparable expression for both Runx1 and 3 in Zbtb7b mutant and wild-type NKT-cells.

There are some similarities between our findings and those previously reported in GATA-3 deficient mice (12), primarily being a lack of CD4+ NKT-cells and reduced IFNγ production by NKT-cells following TCR ligation. GATA-3 is known to bind the Zbtb7b locus and is thought to promote Zbtb7b expression in NKT-cells (17). However, GATA-3 deficient mice lack stage 2 (CD44hi NK1.1low) NKT-cells in the thymus (12), and exhibit a deficiency in peripheral NKT-cells, which clearly distinguishes this defect from that observed in Zbtb7b mutant NKT-cells. Furthermore, NK1.1 was not lower in GATA-3 deficient NKT-cells, they were able to produce IFNγ, and they do not express CD8 (17). Thus, there appears to be at least two factors (GATA-3 and Zbtb7b) that are important for controlling CD4 expression by NKT-cells, and that they work in a non-redundant manner.

The precise mechanisms by which Zbtb7b regulates the development of NKT-cell subsets and how the Leu102Arg mutation affects the function of the protein remain to be determined. It is presently unclear if the L102R mutation is a null allele or has a dominant-negative effect, but since the number of RORγt+, IL17 producing cells is intermediate in the heterozygous mice (Figure 4A and 5B), this appears to support the concept that the mutation is having a null effect. This also fits well with the fact that the Leu102Arg mutation is in the dimerization domain (Supplementary Figure 1) and very likely interferes with the dimerization of Zbtb7b required for transcriptional activation and this likely results in a null allele in the homozygous state. Furthermore, based on our observations from hpls/+ and hpls/hpls mice, the data suggest that full expression of this protein is required to maintain normal numbers of CD4+ NKT-cells, because these are diminished (but not absent) in the heterozygous mice. In contrast, heterozygous mice showed no apparent defect in the percentage or number of conventional CD4+ T-cells in the periphery. It was only in the homozygous mutant mice that we found an absence of CD4+ NKT-cells and an abundance of CD8+ NKT-cells, suggesting that partial expression of Zbtb7b is still sufficient to prevent CD8+ NKT-cells. Whether this simply represents a dose effect acting at the same point in development, or independent effects at different stages in development, is less clear. However, the fact that CD8+ NKT-cells were far more abundant in spleen and liver compared to thymus supports the second scenario, where an absence of functional Zbtb7b allows a delayed increase in CD8+ NKT-cells, which does not occur in the presence of suboptimal Zbtb7b expression. Given the large variability in the population size of pre-existing NKT-cells especially in humans, variability in this process may contribute to individual variability in the types of immune responses made to common antigens. Future functional studies comparing wildtype and hlps/hlps NKT cells, using adoptive transfer into NKT cell deficient mice (containing normal numbers of conventional CD4 T cells) are required to study the influence of hlps mutation on NKT cells in disease models such as infection, cancer and autoimmunity.

In summary, we have determined that Zbtb7b is a critical factor controlling the development of NKT-cell subsets defined by cell surface CD4 and CD8 expression, where CD4 expression is tightly regulated by Zbtb7b such that even partial reduction of this factor diminishes CD4+ NKT-cells, while the emergence of CD8+ NKT-cells only occurs in the absence of Zbtb7b. Zbtb7b also determines the functional potential of NKT-cells, such that in its absence, a RORγt+ IL-23R+ IL-17+ (NKT-17) phenotype predominates. This study demonstrates that the Zbtb7b transcription factor has a profound impact on the development and functional potential of NKT-cells. Further studies into the Zbtb7b mediated molecular pathways that culminate in the altered phenotypes are required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Owen Siggs and Lina Tze for suggesting Zbtb7b as a candidate gene and Belinda Whittle and the Genotyping team of the Australian Phenomics Facility for genotyping, Ken Field (University of Melbourne) and Natalie Saunders (St. Vincent’s Institute) for assistance with flow cytometric cell sorting, and acknowledge the support of the NIH Tetramer facility for providing us with PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer for some of the experiments.

2. This work was funded by research grants from the Wellcome Trust, NIH (NIH-NIAID-DAIT-07-35), NHMRC, the CASS Foundation and the Ramaciotti Foundation. AE was supported by a DFG Research Fellowship (EN 790/1-1) and NHMRC Project grant (APP1009190) and Career Development Fellowship (APP1035858), DIG is supported by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (1020770) and CGG is supported by an NHMRC Australia fellowship (585490) and CCG was supported by an ARC Federation Fellowship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Authorship contribution and conflict of Interest statement: AE, CCG and DIG planned the experiments and wrote the paper. AE, SS, CT, APU, TJ, HB, JAA, SF, ME, CMR and KK performed experiments.

None of the authors has any financial, personal or professional conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1379–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what’s in a name? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coquet JM, Chakravarti S, Kyparissoudis K, McNab FW, Pitt LA, McKenzie BS, Berzins SP, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Diverse cytokine production by NKT cell subsets and identification of an IL-17-producing CD4-NK1.1- NKT cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11287–11292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801631105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gumperz JE, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells revealed by CD1d tetramer staining. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195:625–636. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee PT, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Distinct functional lineages of human V(alpha)24 natural killer T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195:637–641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michel M-L, Keller AC, Paget C, Fujio M, Trottein F, Savage PB, Wong C-H, Schneider E, Dy M, Leite-de-Moraes MC. Identification of an IL-17-producing NK1.1(neg) iNKT cell population involved in airway neutrophilia. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:995–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee PT, Putnam A, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Gottlieb PA, Bendelac A. Testing the NKT cell hypothesis of human IDDM pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:793–800. doi: 10.1172/JCI15832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Vliet HJ, von Blomberg BM, Nishi N, Reijm M, Voskuyl AE, van Bodegraven AA, Polman CH, Rustemeyer T, Lips P, van den Eertwegh AJ, Giaccone G, Scheper RJ, Pinedo HM. Circulating V(alpha24+) Vbeta11+ NKT cell numbers are decreased in a wide variety of diseases that are characterized by autoreactive tissue damage. Clin Immunol. 2001;100:144–148. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berzins SP, Cochrane AD, Pellicci DG, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Limited correlation between human thymus and blood NKT cell content revealed by an ontogeny study of paired tissue samples. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1399–1407. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godfrey DI, Stankovic S, Baxter AG. Raising the NKT cell family. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:197–206. doi: 10.1038/ni.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim PJ, Pai S-Y, Brigl M, Besra GS, Gumperz J, Ho I-C. GATA-3 regulates the development and function of invariant NKT cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:6650–6659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, He X, Dave VP, Zhang Y, Hua X, Nicolas E, Xu W, Roe BA, Kappes DJ. The zinc finger transcription factor Th-POK regulates CD4 versus CD8 T-cell lineage commitment. Nature. 2005;433:826–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun G, Liu X, Mercado P, Jenkinson SR, Kypriotou M, Feigenbaum L, Galéra P, Bosselut R. The zinc finger protein cKrox directs CD4 lineage differentiation during intrathymic T cell positive selection. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:373–381. doi: 10.1038/ni1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wildt KF, Sun G, Grueter B, Fischer M, Zamisch M, Ehlers M, Bosselut R. The transcription factor Zbtb7b promotes CD4 expression by antagonizing Runx-mediated activation of the CD4 silencer. J Immunol. 2007;179:4405–4414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel I, Hammond K, Sullivan BA, He X, Taniuchi I, Kappes D, Kronenberg M. Co-receptor choice by V alpha14i NKT cells is driven by Th-POK expression rather than avoidance of CD8-mediated negative selection. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1015–1029. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Carr T, Xiong Y, Wildt KF, Zhu J, Feigenbaum L, Bendelac A, Bosselut R. The sequential activity of Gata3 and Thpok is required for the differentiation of CD1d-restricted CD4+ NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2385–2390. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda JL, Naidenko OV, Gapin L, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Wang CR, Koezuka Y, Kronenberg M. Tracking the response of natural killer T cells to a glycolipid antigen using CD1d tetramers. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:741–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelms KA, Goodnow CC. Genome-wide ENU mutagenesis to reveal immune regulators. Immunity. 2001;15:409–418. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dave VP, Allman D, Keefe R, Hardy RR, Kappes DJ. HD mice: a novel mouse mutant with a specific defect in the generation of CD4(+) T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8187–8192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egawa T, Littman DR. ThPOK acts late in specification of the helper T cell lineage and suppresses Runx-mediated commitment to the cytotoxic T cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1131–1139. doi: 10.1038/ni.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bilic I, Ellmeier W. The role of BTB domain-containing zinc finger proteins in T cell development and function. Immunol Lett. 2007;108:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Peng H, Schultz DC, Lopez-Guisa JM, Rauscher FJ, Marmorstein R. Structure-function studies of the BTB/POZ transcriptional repression domain from the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger oncoprotein. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5275–5282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kappes DJ, He X, He X. Role of the transcription factor ThPOK in CD4:CD8 lineage commitment. Immunol Rev. 2006;209:237–252. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galéra P, Park RW, Ducy P, Mattéi MG, Karsenty G. c-Krox binds to several sites in the promoter of both mouse type I collagen genes. Structure/function study and developmental expression analysis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21331–21339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benlagha K, Kyin T, Beavis A, Teyton L, Bendelac A. A thymic precursor to the NK T cell lineage. Science. 2002;296:553–555. doi: 10.1126/science.1069017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellicci DG, Hammond KJL, Uldrich AP, Baxter AG, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. A natural killer T (NKT) cell developmental pathway iInvolving a thymus-dependent NK1.1(−)CD4(+) CD1d-dependent precursor stage. J Exp Med. 2002;195:835–844. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rachitskaya AV, Hansen AM, Horai R, Li Z, Villasmil R, Luger D, Nussenblatt RB, Caspi RR. Cutting edge: NKT cells constitutively express IL-23 receptor and RORgammat and rapidly produce IL-17 upon receptor ligation in an IL-6-independent fashion. J Immunol. 2008;180:5167–5171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins A, Littman DR, Taniuchi I. RUNX proteins in transcription factor networks that regulate T-cell lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:106–115. doi: 10.1038/nri2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Townsend MJ, Weinmann AS, Matsuda JL, Salomon R, Farnham PJ, Biron CA, Gapin L, Glimcher LH. T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity. 2004;20:477–494. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doisne J-M, Becourt C, Amniai L, Duarte N, Le Luduec J-B, Eberl G, Benlagha K. Skin and peripheral lymph node invariant NKT cells are mainly retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor (gamma)t+ and respond preferentially under inflammatory conditions. J Immunol. 2009;183:2142–2149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Control points in NKT-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nri2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi T, Chiba S, Nieda M, Azuma T, Ishihara S, Shibata Y, Juji T, Hirai H. Cutting edge: analysis of human V alpha 24+CD8+ NK T cells activated by alpha-galactosylceramide-pulsed monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:3140–3144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee K-A, Kang M-H, Lee Y-S, Kim Y-J, Kim D-H, Ko H-J, Kang C-Y. A distinct subset of natural killer T cells produces IL-17, contributing to airway infiltration of neutrophils but not to airway hyperreactivity. Cell Immunol. 2008;251:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pichavant M, Goya S, Meyer EH, Johnston RA, Kim HY, Matangkasombut P, Zhu M, Iwakura Y, Savage PB, DeKruyff RH, Shore SA, Umetsu DT. Ozone exposure in a mouse model induces airway hyperreactivity that requires the presence of natural killer T cells and IL-17. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:385–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshiga Y, Goto D, Segawa S, Ohnishi Y, Matsumoto I, Ito S, Tsutsumi A, Taniguchi M, Sumida T. Invariant NKT cells produce IL-17 through IL-23-dependent and -independent pathways with potential modulation of Th17 response in collagen-induced arthritis. Int J Mol Med. 2008;22:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang XO, Panopoulos AD, Nurieva R, Chang SH, Wang D, Watowich SS, Dong C. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9358–9363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bendelac A, Killeen N, Littman DR, Schwartz RH. A subset of CD4+ thymocytes selected by MHC class I molecules. Science. 1994;263:1774–1778. doi: 10.1126/science.7907820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egawa T, Eberl G, Taniuchi I, Benlagha K, Geissmann F, Hennighausen L, Bendelac A, Littman DR. Genetic evidence supporting selection of the Valpha14i NKT cell lineage from double-positive thymocyte precursors. Immunity. 2005;22:705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hager E, Hawwari A, Matsuda JL, Krangel MS, Gapin L. Multiple constraints at the level of TCRalpha rearrangement impact Valpha14i NKT cell development. J Immunol. 2007;179:2228–2234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Cruz LM, Knell J, Fujimoto JK, Goldrath AW. An essential role for the transcription factor HEB in thymocyte survival, Tcra rearrangement and the development of natural killer T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:240–249. doi: 10.1038/ni.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan AC, Berzins SP, Godfrey DI. Developing NKT cells need their (E) protein. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taniuchi I, Osato M, Egawa T, Sunshine MJ, Bae SC, Komori T, Ito Y, Littman DR. Differential requirements for Runx proteins in CD4 repression and epigenetic silencing during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 2002;111:621–633. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Setoguchi R, Tachibana M, Naoe Y, Muroi S, Akiyama K, Tezuka C, Okuda T, Taniuchi I. Repression of the transcription factor ThPOK by Runx complexes in cytotoxic T cell development. Science. 2008;319:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1151844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.