Abstract

The influence of five monoamine candidate genes on depressive symptom trajectories in adolescence and young adulthood were examined in the Add Health genetic sample. Results indicated that, for all respondents, carriers of the DRD4 5-repeat allele were characterized by distinct depressive symptom trajectories across adolescence and early adulthood. Similarly, for males, individuals with the MAOA 3.5-repeat allele exhibited unique depressive symptom trajectories. Specifically, the trajectories of those with the DRD4 5-repeat allele were characterized by rising levels in the transition to adulthood, while their peers were experiencing a normative drop in depressive symptom frequency. Conversely, males with the MAOA 3.5-repeat allele were shown to experience increased distress in late adolescence. An empirical method for examining a wide array of allelic combinations was employed, and false discovery rate methods were used to control the risk of false positives due to multiple testing. Special attention was given to thoroughly interrogate the robustness of the putative genetic effects. These results demonstrate the value of combining dynamic developmental perspectives with statistical genetic methods to optimize the search for genetic influences on psychopathology across the life course.

There is a burgeoning consensus among scholars that depressive symptoms follow a normative, inverted U-shaped trajectory before and during the transition to adulthood—peaking in late adolescence and falling in young adulthood (e.g., Ge, Natsuaki, & Conger, 2006; Adkins, Wang, Dupre, van den Oord, & Elder, 2009). Further, research has also consistently shown significant between-individual variation around mean trajectories (Adkins, Wang, & Elder, 2008; Adkins et al., 2009). Explaining individual differences in adolescent and young adult depressive symptom trajectories has proven a difficult task, with well-specified models including exhaustive lists of social risk factors explaining only modest amounts of trajectory variance (Natsuaki, Biehl, & Ge, 2009; Adkins et al., 2009). This has led to growing interest in the role of genetics in explaining individual differences in the development of depressed affect, with experts increasingly drawing on the diathesis-stress perspective to empirically investigate gene × environment interaction (e.g., Caspi, McClay, Moffitt, Mill, Martin et al., 2002; Costello, Pine, Hammen, March, Plotsky et al., 2002).

This interest among behavioral scientists in the role of genetics in explaining developmental patterns of depressed affect is supported by several lines of inquiry within genetics. While it has long been known that depression is substantially heritable (Sullivan, Neale, & Kendler, 2000), recent research has indicated that genetic influences on affect may vary considerably across development. For instance, biometric genetics research has shown that the heritability of depression significantly varies across adolescence and young adulthood, suggesting that the influence of various genes may increase or decrease across this important developmental period (e.g., Bergen, Gardner, & Kendler 2006). Moreover, some research in this vein has indicated that distinct sets of genetic factors contribute to depressed affect at different points in development (Silberg, Pickles, Rutter, Hewitt, Simonoff et al., 1999; Scourfield, Rice, Thapar, Harold, Martin et al., 2003). Reiss and Neiderhiser (2000) have synthesized research in the area, presenting evidence of both quantitative and qualitative changes in genetic influence across development, while also arguing for the importance of environmental factors in moderating these changes. This perspective has proven prescient, receiving support from recent epigenetics research showing substantial gene expression changes across childhood and adolescence as developmental mechanisms “turn various genes off and on” (Whitelaw & Whitelaw 2006). Thus, beyond suggesting consistent gene effects across adolescence and young adulthood, contemporary genetics research has indicated that the influence of specific genetic loci may vary over the period.

Given this knowledge, it is perhaps surprising that virtually no research has considered gene × age interaction effects for candidate genes on depression trajectories across this developmentally dynamic life stage. The current study addresses this gap in the literature by investigating gene × age interaction on depressive symptom trajectories for five leading monoaminergic candidate genes, 5-HTTLPR, DRD4, MAOA, DRD2, and DAT1, using false discovery rate (FDR) methods to control for the risks of false discoveries due to multiple testing. Below we discuss major streams of thought motivating this inquiry, including literature on depressive symptom trajectories, conventional static approaches on genetic influences on depressed affect, and emergent perspectives on developmental dynamism in genetic influences.

Depressive symptom trajectories across adolescence and young adulthood

Though longitudinal analyses of nationally representative data across adolescence and young adulthood remain uncommon, there is mounting evidence of a normative, inverted U-shaped pattern of depressed affect across this life course period. This conclusion is supported by longitudinal research finding curvilinear trajectories in samples of individuals moving through adolescence and young adulthood, as well as by research in younger samples showing linear increase through middle adolescence and studies of young adult samples showing linear decrease or stability through the twenties. For instance, inverted U-shaped trajectories have been found across ages 12–26 in former, methodologically robust analyses of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) (Natsuaki et al., 2009; Adkins et al., 2009). Similarly, analyzing eleven waves of longitudinal data covering ages 12–23, Ge and colleagues (2006) found curvilinear trajectories of depressive symptoms, rising in early and middle adolescence and declining in late adolescence. Furthermore, Wight, Sepulveda, and Aneshensel (2004) examined depressive symptoms in three datasets (one adolescent sample and two adult samples) and found increasing levels in the adolescent sample, while the adult samples showed both lower initial levels and a steady decline over time. Consistent findings have been reported in several other analyses (e.g., Ge, Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994; Hankin, Abramson, Moffitt, Silva, McGee et al., 1998; Wade, Cairney, & Pevalin, 2002), collectively offering strong support for a normative curvilinear depressive symptom trajectory across this developmental period.

In addition to elucidating average trajectories of depressive symptoms in early life, research has also highlighted the longstanding issue of individual differences in the development of depression and depressive symptoms. For instance, recent trajectory analyses of Add Health using mixed effects modeling (Adkins et al., 2008; Natsuaki et al., 2009) and latent trajectory modeling (Adkins et al., 2009) have shown that both intercept and slope trajectory components vary significantly across individuals, showing the majority of variance in the depressive symptoms measure is comprised by individual differences in these trajectory components. And though some of this variation may eventually be explained by improved measurement and modeling of social influences, there is a growing recognition that, as posited by the diathesis-stress model, a substantial portion of it is likely due to genetic factors (Caspi et al., 2002; Costello et al., 2002).

Genetic factors in depression and depressive symptoms

Epidemiological research has offered strong evidence of the importance of genetics, with family studies indicating first-degree relatives of depressed probands to be 2.84 times more likely to experience major depression than controls, and twin studies indicating the heritability of unipolar depression to be 31–42% (Sullivan, Neale, & Kendler, 2000). But despite the longstanding body of biometric genetics research showing substantial genetic influence, advances in mapping the molecular underpinnings of the phenotype have been slow. And while no consensus has been reached regarding the primary molecular mechanisms underlying mood disorder susceptibility, a confluence of neurobiological, pharmacological and molecular genetic evidence has supported an important role for monoaminergic neurotransmission, particularly the serotonergic and dopaminergic systems. Among the many candidate gene variants influencing these systems, polymorphisms in: 5-HTTLPR, DRD4, MAOA, DAT1 and DRD2 are among the most promising.

Serotonin Transporter (5-HTTLPR, locus symbol SLC6A4)

Among neurotransmission systems the serotonergic system has received the most attention for its involvement in several processes including brain development and synaptic plasticity. Located at 17q11.2, the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) encodes a protein critically involved in the control of serotonin (5-HT) function. Allelic variation in the transcriptional region of 5-HTT, known as 5-HTTLPR, has been associated with personality traits including anxiety and aggressiveness (Anguelova, Benkelfat, & Turecki, 2003). Short (S) and long (L) 5-HTTLPR variants differentially influence transcription activity of the 5-HTT gene promoter and the consequent 5-HT uptake in lymphoblastoid cells. While results of main effects of 5-HTTLPR on depression have been mixed (Anguelova et al., 2003), Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig et al., (2003) have drawn together several lines of experimental genetic research to theorize that 5-HTTLPR may moderate the serotonergic response to stress. Investigating this hypothesis, Caspi and colleagues (2003) found individuals possessing the S allele of 5-HTTLPR to present more depression in response to stressful life events (SLEs) than individuals homozygous for the L allele. Since this study, several studies have attempted replication, yielding both positive (e.g., Wilhelm, Mitchell, Niven, & Wedgewood, 2006)) and null results (e.g., Gillespie, Whitfield, Williams, Heath, & Martin, 2005; Surtees, Wainwright, Willis-Owen, Luben, Day et al., 2006).

Dopamine D4 Receptor (DRD4)

The DRD4 gene maps 11p15.5 and contains a functional variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) polymorphism in its third exon (Van Tol, Wu, Guan, Ohara, Bunzow et al., 1992). The variant repeats two to 11 times, with two (D4.2), four (D4.4), and seven (D4.7) repeats being the most common alleles (Van Tol et al., 1992). DRD4 shows high levels of expression in frontal area of the brain and the nucleus acumbens—areas associated with affective behaviors (Emilien, Maloteaux, Geurts, Hoogenberg, & Cragg 1999; Oak, Oldenhof, & Van Tol 2000). In vitro studies have indicated that alleles with decreased affinity for dopamine (e.g., DRD4.7 and DRD4.2), transmit weaker intracellular signals in comparison with other DRD4 alleles, thus may promote depressed affect through suboptimal functionality (Asghari, Sanyal, Buchwaldt, Paterson, Jovanovic et al., 1995). While several lines of research have suggested DRD4 as a candidate gene for mood disorders, association results have been mixed. Significant associations have been reported for depressive disorders (e.g., Manki, Kanba, Muramatsu, Higuchi, Suzuki et al., 1996; Muglia, Petronis, Mundo, Lander, Cate et al., 2002), but other studies have failed to confirm these findings (e.g., Bocchetta, Piccardi, Palmas, Oi, & Del Zompo, 1999; Serretti, Cristina, Lilli, Cusin, Lattuada et al., 2002). It has been suggested that these failures to replicate may have been due to underpowered samples (Lohmueller, Pearce, Pike, Lander, & Hirschhorn, 2003), a view supported by a recent, comprehensive meta-analysis which found a strong significant association between the DRD4.2 allele and unipolar depression (Lopez, Pearce, Pike, Lander, & Hirschhorn, 2005).

Monoamine Oxidase A promoter (MAOA-uVNTR)

Located on the short arm of the X chromosome (Xp11.23) (Sabol, Hu, & Hamer, 1998), the MAOA gene is considered a likely depression candidate gene based on two lines of evidence. First, MAOA has a central role in controlling amine disposability at the synaptic cleft, preferentially metabolizes serotonin and norepinephrine (Bach, Lan, Johnson, Abell, Bembenek et al., 1988). Second, MAOA inhibitors have been found effective in the treatment of depression (Murphy, Mitchell, & Potter, 1994). While several different polymorphisms in the MAOA gene have been identified, only the VNTR polymorphism has been shown to affect the transcriptional activity of the MAOA gene promoter. This polymorphic region consists of a 30 bp repeated sequence present in 2, 3, 3.5, 4, or 5 copies. Alleles with 3.5 or 4 copies are transcribed 2 to 10 times more efficiently than those with 2, 3 or 5 copies of the repeat (Sabol et al., 1998). While this promoter VNTR has shown association with several affective disorders including recurrent major depression (Preisig, Bellivier, Fenton, Baud, Berney et al., 2000; Schulze, Muller, Krauss, Scherk, Ohlraun et al., 2000), other studies have reported null results (Furlong, Ho, Rubinsztein, Walsh, Paykel et al., 1999; Kunugi, Ishida, Kato, Tatsumi, Sakai et al., 1999).

Dopamine Transporter (DAT1, locus symbol: SLC6A3)

The dopamine transporter gene, DAT1, maps to chromosome 5p15.3 and has a functional VNTR with alleles ranging from 3–11 repeats (Vandenbergh, Persico, Hawkins, Griffin, Li et al., 1992). In the central nervous system, the dopamine transporter protein, DAT, mediates reuptake of dopamine from the synaptic cleft, and thus is largely responsible for the intensity and duration of dopaminergic neurotransmission (Storch, Ludolph, & Schwarz, 2004). Given the central role of the dopaminergic system in neurobiological theories of depression, DAT1 represents a plausible depression candidate, with several lines of evidence linking it to affect. For instance, pharmacological animal studies have demonstrated that drugs affecting DAT function (e.g., cocaine and amphetamine) enhance dopaminergic signaling, which induces hyperactivity and other changes in mood and behavior. The protein’s importance to normal behavior has been demonstrated in DAT knockout mice (Giros, Jaber, Jones, Wightman, & Caron, 1996). Due to the lack of the transporter protein, these animals have constantly elevated dopaminergic neurotransmission resulting in hyperactive behavior and negating the effects of psychostimulants. Results from main effect genetic association studies of DAT1 to affective disorders have yielded mixed results (Kelsoe, Sadovnick, Kristbjarnarson, Bergesch, Mroczkowski-Parker et al., 1996; Waldman, Robinson, & Feigon, 1997). However, DAT1 has recently been analyzed from a GxE perspective, with results indicating a significant interaction with maternal rejection on major depressive disorder (MDD) onset and suicidal ideation (Haeffel, Getchell, Koposov, Yrigollen, DeYound et al., 2008).

Dopamine D2 receptor (DRD21, rs1800497)

The TaqI A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs1800497 is located 10 kb downstream of DRD2, in a protein-coding region of the adjacent ANKK1 gene (Fossella, Green & Fan, 2006). This SNP was long thought to lie within DRD2 and is known to be relevant to dopaminergic function, predicting D2 receptor density (Noble and Cox 1997; Thompson, Thomas, Singleton, Piggott, Lloyd et al., 1997) and glucose metabolism in dopaminergic regions of the human brain (Noble, Gottschalk, Fallon, Ritchie, & Wu, 1997). The association of the SNP to D2 function is generally thought to stem from linkage disequilibrium with functional variants within DRD2 (Neville, Johnstone & Walton, 2004). Consequently, the polymorphism has been studied as a candidate for affective disorders, with studies generally focusing on the A1 minor allele as a risk variant, as functional studies of both humans and mice have shown individuals with the A1 allele to have lower density of dopamine D2 receptors throughout the brain (Noble and Cox 1997; Nobel et al., 1997). Empirical findings of direct affective influence have been mixed, however, with some studies finding significant associations (Li, Liu, Sham, Aitchison, Cai et al., 1999) and others not (e.g., Serretti, Macciardi, Cusin, Lattuada, Souery et al., 2000). Recent research has attempted to resolve this discrepancy using a GxE approach, finding a significant interaction between DRD2 and SLEs on depressive symptomatology (Elovainio, Jokela, Kivimaki, Pulkki-Raback, Lehtimaki et al., 2007).

Age moderation of genetic influence

The period of adolescence to young adulthood is among the most developmentally intensive periods in the life course. It is characterized by important biological changes, such as puberty, and also a dramatic shift in social environment as children’s parent-dominated social experience gives way to an expanding range of social options. Moreover, these changes have been linked to variation in the influence of genetic factors in ways that are potentially relevant to gene × age interaction in depressive symptom trajectories. For instance, there is ample evidence of extensive gene expression changes during adolescence, during which genes may be de/silenced (i.e., “turned on and off”) through developmentally and environmentally induced epigenetic changes (Whitelaw & Whitelaw 2006). And while puberty represents a particularly striking example of phenotypic change in response to developmental epigenetic change (Whitelaw & Whitelaw 2006), both mouse and human studies have demonstrated that these epigenetic changes continue across young adulthood and, indeed, throughout the life course (Barbot, Dupressoir, Lazar, & Heidmann, 2002; Fraga, Ballestar, Paz, Ropero, Setien et al., 2005). Although no research has yet focused on epigenetic regulation of monoamine genes in adolescence and young adulthood, given the extensive epigenetic changes characterizing the period, it is plausible that these genes may be differentially expressed, suggesting a potential molecular mechanism for gene × age interaction in depressive symptom trajectories during the transition to adulthood.

Biometric studies offer another source of evidence indicating changes in the influence of genetics on depression across adolescence and young adulthood. Analyzing twin, family, and adoptee data, biometric genetic studies decompose phenotype variance into aggregate genetic and environmental components without reference to molecular data. Many of these studies have examined depression at various points in early life (e.g., Eley & Stevenson, 1999; Silberg, Rutter, & Eaves, 2001), and some have modeled how aggregate genetic influence changes as a function of age (e.g., Nes, Roysamb, Reichborn-Kjennerud, Harris, & Tambs, 2007). The results of this body of research are well-summarized by a recent meta-analysis by Bergen, Gardner, and Kendler (2007), who analyzed 6 studies with sample ages ranging from 8–28, showing that the heritability of depression significantly increases from approximately 21% at age 8 to 42% at age 28.

Bergen and colleagues (2007) offer two broad, non-mutually exclusive potential explanations for the increasing role of genetics in depression as individuals move through adolescence and young adulthood. First, they suggest that as individuals age out of childhood, the role of parental social control recedes and individuals begin to self-select into environments, allowing them to more readily express their genetic proclivities. For instance, with parents no longer structuring their time, college students with depressive tendencies may fail to maintain social ties and drift towards isolation. The authors also offer the possibility that developmental epigenetic changes may “turn on” novel genes, providing additional sources of genetic variance. Further, the two mechanisms may interact, with novel environmental exposures triggering epigenetic changes. And while these possibilities can not be adjudicated between without longitudinal epigenetic data, they both provide convincing rationale for considering age variation in the effects of known depression candidate genes across adolescence and young adulthood.

Methods

Sample

Data were analyzed from three waves of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Add Health is a large nationally representative, longitudinal sample of adolescents and young adults. The National Quality Education Database was used as the baseline sample frame, from which 80 high schools were selected with an additional 52 feeder middle-schools. The overall response rate for the 134 participating schools was 79 percent. Of the over 90,000 students who completed in-school surveys during the 1994–1995 academic year, a sample of 20,745 adolescents in grades 7–12 were selected and have been interviewed 3 times in 1994–1995, 1995–1996, and 2001–2002. A questionnaire was also administered to a selected residential parent of each adolescent. Further details of Add Health’s sampling design, response rates, and data quality are well-documented (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design).

The current study analyzes the three waves of repeated measures data from the Add Health sibling subsample, for which DNA measures are available. The sibling sample is composed of groups of respondents residing in the same household, and includes individuals of various degrees of biological relatedness, ranging from monozygotic twins to unrelated individuals. Respondents were included in the analysis sample if they had nonmissing values on all variables on at least one assessment. The total analysis sample consisted of 5614 observations for 1909 individuals, with each individual contributing an average of 2.9 observations. Individuals were nested within 1129 households, with each household containing 1–4 individuals (1.7 on average).

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using a 9-item scale derived from the conventional 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977). The 20-item CES-D is composed of questions on a number of physical and psychological symptoms of depression, which cluster into four factors: somatic, depressed affect, positive affect, and interpersonal relations (Ensel 1996; Radloff 1977). The scale has been validated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in adult samples of Whites and Blacks (Blazer, Landerman, Hays, Simonsick, & Saunders, 1998).2 It has also been validated in samples of adolescents and young adults (Radloff 1991). Fortunately, a 19-item CES-D was collected in the first two waves of Add Health and a comparison with the subscale (9 items) indicated a high correlation (r = 0.91 and 0.92 in waves one and two, respectively). Individual items were coded on a four-point scale to indicate the frequency of symptoms occurring during the past week, ranging from never or rarely (0) to most or all of the time (3). The primary outcome used in this analysis is the simple average of the 9 items.

In addition to using a simple average of the 9 items available across all three survey waves, sensitivity analyses were conducted using: 1) a CFA factor score of the 9 items, 2) an average of the 3 depressed affect items collected in all waves, which have been shown to be measurement invariant across racial/ethnic and immigrant groups in Add Health (Perreira, Deeb-Sossa, Harris, & Bollen, 2005), and 3) a factor score of these 3 items. It has been shown previously that the use of factor scores for phenotypic measurement refinement can improve power to detect genetic effects (e.g., van den Oord, Kuo, Hartmann, Webb, Moller et al., 2008). Further, analyses of the current data indicate that allowing factor loadings to vary significantly improves model fit for both the 9 and 3 item measures. In addition to measurement invariance characteristics, the use of the 3 item subscale was also indicated by both notably higher factor loadings for these items relative to the other 6 indicators, as well as stronger theoretical correspondence of the items to the depression construct (see Perreira et al., 2005). Correlations were high between all 4 specifications of the depressive symptoms variable (r = 0.84–0.98). A constant was added to the factor scores setting their minimum values equal 0, in order to increase comparability of model parameters across depressive symptom specifications.

Parental socioeconomic status

Add Health allows respondents to report parental education levels for resident mother and father figures. These variables describe the highest level of education that the parent has completed, and range from “never went to school” to “professional training beyond a four year college or university”. Based on previous analyses, these items were coded as continuous variables (Adkins et al., 2008). For each respondent the mean was then taken of reported parental education levels, which improved the explanatory power of the variable relative to either parent’s level singly. Household income was ascertained from the parental questionnaire and includes all sources of income from the previous year (measured in thousands of dollars), and was logged. Correlation between parental education and logged household income was moderate (r = 0.43), indicating collinearity was not problematically high. SES indicators were mean-centered to aid in model interpretation.3

Stressful life events

An additive index was used to measure cumulative exposure to stressful life events. Presented in Appendix A, the SLE index used here is derived from one developed by Ge and colleagues (1994). Established criteria for the development of the SLE index were used in modifying and expanding the measure for the Add Health survey (Turner & Wheaton, 1995). For instance, only acute events of sudden onset and of limited duration that occurred within 12 months of the interview were included (Turner & Wheaton, 1995). Further, given previous research indicating that undesirable life events are more likely to adversely affect health (e.g., Compas, 1987), only negative life events were included in the index. To ensure a complete coverage of stressful events, approximately 50 items from various domains of life (e.g., family, romantic and peer conflicts, academic problems, exposure to violence, death of family and friends) were included. A major challenge of operationalizing SLEs is longitudinal validity—as adolescents make the transition into adulthood, some stressors become irrelevant (e.g., expulsion from school) and other stressors become relevant (e.g., divorce). Thus, to ensure stress was appropriately measured at different life stages, slightly different set of items is used in wave III to capture the different life experiences. An additive index was created from the selected items and is mean-centered in the current analysis.

Appendix A.

List of Items in Stressful Life Events Index

| Wave I, II, and III items |

|---|

| Death of a parent |

| Suicide attempt resulting in injury |

| Friend committed suicide |

| Relative committed suicide |

| Saw violence |

| Threatened by a knife or gun |

| Was shot |

| Was stabbed |

| Was jumped |

| Threatened someone with a knife or gun |

| Shot/stabbed someone |

| Was injured in a physical fight |

| Hurt someone in a physical fight |

| Unwanted pregnancy |

| Abortion, still birth, or miscarriage |

| Had a child adopted |

| Death of a child |

| Romantic relationship ended |

| Had sex for money |

| Contracted a STD |

| Skipped necessary medical care |

| Juvenile conviction |

| Adult conviction |

| Served time in jail

|

| Wave I and II items only |

| Was expelled from school |

| Suffered a serious injury |

| Father received welfare |

| Mother received welfare |

| Was raped |

| Ran away from home |

| Nonromantic sexual relationship ended |

| Suffered verbal abuse in a romantic relationship |

| Suffered physical abuse in a romantic relationship |

| Suffered verbal abuse in a nonromantic sexual relationship |

| Suffered physical abuse in a nonromantic sexual relationship

|

| Wave III items only |

| Evicted from residence, cutoff service |

| Entered full time active military duty |

| Discharged from the armed forces |

| Cohabitation dissolution |

| Received welfare |

| Involuntarily dropped from welfare |

| Marriage dissolution |

| Baby had major health problems at birth |

| Death of a romantic partner |

| Death of a spouse |

Social support

The social support index shown in Appendix B is a composite measure of perceived social support across waves I and II. It assesses how the respondents feel about their relationship with their closest social ties including family, teachers and parents. A CFA of the items indicated adequate fit (CFI = 0.971; RMSEA = 0.06) when including wave-specific factors and item-specific correlated errors between the two waves. A simple average of all the social support items was calculated and mean-centered in this analysis.

Appendix B.

Social Support Scale

| 1. | How much do you feel that adults care about you? |

| 2. | How much do you feel that your teachers care about you? |

| 3. | How much do you feel that your parents care about you? |

| 4. | How much do you feel that people in your family understand you? |

| 5. | How much do you feel that your family pays attention to you? |

Race/ethnicity

Add Health allows respondents to indicate as many race and ethnic categories as deemed applicable. Approximately 4% of the participants report a multiracial/ethnic identity. Following criteria developed by Add Health data administrators, we assign one racial identity for persons reporting multiple backgrounds.4 This method combines Add Health’s five dichotomous race variables and the Hispanic ethnicity variable as following: respondents identifying a single race are coded accordingly; respondents identifying as Hispanic were coded as such regardless of racial designation; those identifying as “black or African American” and any other race were designated as Black; those identifying as Asian and any race other than Black were coded as Asian, those identifying as Native American and any race other than Black or Asian were coded as Native American, and those identifying only as “other” were coded as such.5

Candidate genes

In Wave III in 2002, DNA samples were collected from a subset of the Add Health sample. Genomic DNA was isolated from buccal cells at the Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado (Smolen and Hewitt, www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/), using a modification of published methods (Freeman, Powell, Ball, Hill, Craig et al., 1997; Lench, Stanier, & Williamson, 1988; Meulenbelt, Droog, Trommelen, Boomsma, & Slagboom, 1995; Spitz, Mourtier, Reed, Busnel, Marchaland et al., 1996). The average yield of DNA was 5871 mg. All of the Wave III buccal DNA samples are of excellent quality and have been used to assess nearly 48,000 genotypes.

DAT1

The allelic distribution of the 40 base pair (bp) VNTR in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the gene has been determined in duplicate (two separate PCR amplifications and analyses, 5224 genotypes). The allelic distributions in bp and number of repeats (#R) were: 360 bp (7R), 0.29%; 400 bp (8R), 0.34%; 440 bp (9R), 21.67%; 480 bp (10R), 76.98%; and 520 bp (11R), 0.72%. DRD4: The 48 bp VNTR element in the third exon was determined in duplicate as above (5224 genotypes). The allelic distributions were: 379 bp (2R), 8.28%; 427 bp (3R), 3.06%; 475 bp (4R), 64.71%; 523 bp (5R), 1.45%; 571 bp (6R), 0.74%; 619 bp (7R), 20.63%; 667 bp (8R) 0.84%; 715 bp (9R), 0.08%; and 763 bp (10R), 0.19%. SLC6A4: The 44 bp addition/deletion in the 5′ regulatory region was determined in duplicate as above (5224 genotypes). The allelic distributions were: 484 bp (“short allele), 42.11%; and 528 bp (“long allele”), 57.89%. MAOA-uVNTR: The 30 bp VNTR in the promoter was determined in duplicate as above (5224 genotypes). The allelic distributions were: 291 bp (2R), 1.26% (males), 1.19% (females); 321 bp (3R), 40.21% (males), 36.29% (females); 336 bp (3.5R), 1.04% (males), 1.14% (females); 351 bp (4R), 56.31% (males), 60.14% (females); 381 bp (5R), 1.18% (males), 1.24% (females). DRD2 TaqIA: The polymorphic TaqI restriction endonuclease site was determined in duplicate as above (5224 genotypes). The allelic distributions were: 178 bp, 74.06%; 304 bp, 25.94%.

Analytical strategy

Add Health is typical among longitudinal datasets, in that it is organized by wave of assessment with variability in chronological age at each wave. However, given that developmental research has clearly demonstrated age to be a more meaningful time metric than wave for the study of depression trajectories (e.g., Ge et al., 1994; Hankin et al., 1998), the data have been restructured in this analysis to provide age-based measurements. Fortunately, the statistical method employed—linear mixed effects models—has been shown to effectively accommodate features of the restructured data, including unbalanced repeated measures, variable data schedules, and missing observations (Diggle & Kenward, 1994; Willett, Singer, & Martin, 1998).

Linear mixed effects models have long been established in the statistical literature for the analysis of clustered, non-independent data (Searle 1971; Searle, Casella, & McCulloch, 1992), and are known to be particularly advantageous for growth curve analyses of longitudinal data (Willett et al., 1998). The following equation describes a simplified version of the general mixed regression model used to investigate age variation in the effects of the candidate genes on depressive symptoms (DS):

where j, i, and t index the three levels of data: sibling cluster (i.e., household), individual, and assessment, respectively. Thus, the model allows random effects at both the sibling cluster and individual levels. Conditional on the random intercepts μj0 and υji0 at the sibling cluster and individual levels, the siblings and repeated assessments are assumed to be independent. The household level random effect captures much of the influence of population stratification on the results. This is because it accounts for intercept variation in depressive symptoms between households, with the assumption that the household cluster should be a decent proxy for identical by descent genetic similarity. Further control of population stratification is gained by the inclusion of self-identified race/ethnicity in all models.

The base model, without genetic effects, controls for race/ethnicity, gender, age, age2, social support, parental education, household income, and SLEs.6 This model is consistent with prevailing environmental theories of depression and has been empirically tested by the author in previously published analyses of Add Health (see Adkins et al., 2009; Adkins et al., 2008). For the primary set of analyses, in addition to the base model, each estimated model included a genetic variable and interaction terms between the genetic variable and both age and age2; thus examining variation in genetic effects across age by modeling genetic effects on each of the three trajectory components—intercept, linear age slope, and quadratic age slope. Sensitivity analyses repeat this procedure for each of the three alternate specifications of depressive symptoms. After identifying the most promising candidate genes, the robustness of these models are tested in an additional sensitivity analysis, by square root transforming the CES-D and rerunning the models to eliminate the possibility that results are driven by outliers.

For 5-HTTLPR, DRD4, DAT1 and DRD2, analyses were conducted on the full sample of both males and females. An alternative approach was used for MAOA, as its location on the X chromosome complicates direct comparisons between males and females. This is because males have a single allele at this locus (as they have only a single X chromosome), making their characterization straightforward, while females have two alleles, one of which may be silenced to some degree via X-inactivation (Jansson, McCarthy, Sullivan, Dickman, Andersson et al., 2005; Meyer-Lindenberg, Buckholtz, Kolachana, Hariri, Pezawas et al., 2006). Given this ambiguity, analyses of MAOA are stratified by gender, while the full sample is jointly analyzed for all other genes.

The case of MAOA in females is illustrative of a more pervasive issue—it is often unclear what the optimal specifications of allelic effects are. Examples of both additive effects, in which there is a dose-response relationship between number of the risk alleles and the phenotype, and dominance effects, where a single allele is sufficient to give the full phenotypic effect, abound in the psychiatric genetics literature. Moreover, in psychiatric genetics there are also documented instances in which heterozygosity at a given locus is associated with a greater or lesser phenotypic effect, compared to homozygotes of either allele (e.g., Chen, Rainnie, Greene, & Tonegawa, 1994; Guo, Roettger, & Shih, 2007). And though former human genetics research, animal studies, and functional analyses can be informative in selecting allelic effect specifications, this knowledge is incomplete at best, and expectations are frequently overturned. DRD4 is instructive in this regard—while functional studies have generally implicated the 7R allele (Asghari et al., 1995), a recent meta-analysis instead only showed significant association between the 2R allele and unipolar depression (Lopez et al., 2005). The case of MAOA and delinquency is similarly instructive as Caspi and colleagues (2002) have reported GxE between the MAOA 3R and maltreatment, while Guo and colleagues (Guo, Ou, Roettger, & Shih, 2008, Guo, Roettger, & Cai, 2008) have instead shown evidence of both main effects and GxE with the 2R allele, offering no support for a role of the 3R allele in delinquency.

In short, the field of molecular genetics is not yet far enough advanced to definitively dictate how genetic variables are best specified in statistical tests of association. That is to say, the frequency of unexpected associations combined with relatively weak theory of genetic mechanisms suggests that approaches relying strictly on precedent to specify allelic effects are vulnerable to missing true associations. This line of logic recommends an empirical approach to systematically screen various allelic effect specifications and gene × age configurations. Moreover, in practice researchers conducting candidate gene studies often tacitly employ such empirical, exploratory methods, but do not adjust significance criteria to account for multiple testing (Colhoun, McKeigue, & Smith, 2003). Indeed, the enormous problem of false discoveries in candidate gene research, with 19 out every 20 associations currently reported in the literature thought be false, is largely due to researchers conducting multiple tests, but only reporting significant findings (Colhoun et al., 2003; van den Oord, 2008). Given these facts, experts have argued that optimal methods for genetic discovery should cast a wide net, using exhaustive exploratory techniques, yet explicitly recognize the reduced confidence in any single association and adjust significance criteria accordingly (van den Oord, 2005, 2008). Research has indicated that controlling for the false discovery rate (FDR) is a superior method for achieving these aims in candidate gene studies with correlated tests, such as the current analysis (van den Oord, 2005; van den Oord & Sullivan, 2003).

False discovery rate

For each allele of the five monoamine genes investigated in this study, additive, dominance and heterogeneous allelic effects were tested, each in a separate mixed model. Thus, the primary analysis consisted of 69 models, one for each of the 69 allelic specifications tested (counting MAOA alleles separately for male and females).7 In each of the 69 models of the primary analysis, there were three coefficients of substantive interest, the direct genetic effect and the gene × age and gene × age2 interaction effects, resulting in 207 coefficients of interest from the primary analysis. Clearly, tests evaluating the statistical significance of these 207 coefficients are not independent. Different allelic specifications of the same polymorphism are correlated and thus, their test statistics also exhibit correlation. The same is true for the direct genetic, gene × age and gene × age2 effects for the same allelic specification—their tests of association are not independent and should not be treated as such. The ability to handle such correlated tests is a key benefit of the FDR approach employed here (Storey and Tibsharani 2003; Sabatti, Service, and Freimer, 2003; Fernando, Nettleton, Southey, Dekkers, Rothschild, et al., 2004). Unlike traditional procedures for adjusting for multiple testing, such as Bonferroni correction, the FDR approach yields powerful and valid inference even at relatively high levels of correlation (Sabatti, Service, and Freimer, 2003; van den Oord 2005).8

Standard p-values for the genetic, gene × age, and gene × age2 coefficients from each estimated mixed model were concatenated and FDRs were estimated from the p-value distributions. FDRs can be estimated in various ways and many standard statistical packages (e.g., R, SAS) have such estimation procedures implemented. The current study estimates a FDR for a chosen threshold p-value t. If the m p-values are denoted pi, i = 1…m, this can be done using the formula:

Thus, the FDR is estimated by dividing the estimated number of false discoveries (the number of tests times the probability t of rejecting a marker without effect) by the total number of significant markers (i.e. total number of p-values smaller than t) that includes the false and true positives. To avoid arbitrary choices, each of the observed p-values can be used as a threshold p-value t. The resulting FDR statistics are then called q-values. In the current analysis, associations with q < 0.1 are considered potentially interesting, indicating the 1 out of 10 reported findings would be expected to be a false discovery.9 This procedure was repeated for each of the three sensitivity outcomes, producing 828 coefficients of interest in total. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 11 (StataCorp LP; www.stata.com) and FDRs were calculated using R 2.10.0 (http://www.r-project.org/index.html).

Results

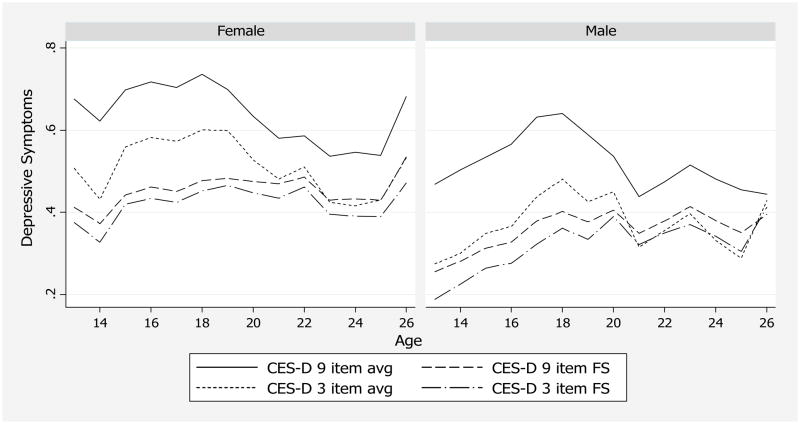

Figure 1 plots means for each of the four CES-D specifications examined, by age and gender. Notable patterns include elevated symptom counts in late adolescence for all CES-D specifications and both genders, with symptom counts peaking around age 18. Females exhibit substantially higher symptom levels than males across all ages for all outcomes. Lower symptom levels were observed for the 3 item and factor score CES-D specifications relative to the primary 9 item outcome, indicating that depressed affect symptoms occurred less frequently than symptoms of other dimensions. All outcomes exhibited roughly the same over-time pattern.

Figure 1.

Mean depressive symptom levels for 4 CES-D specifications, plotted by age and gender

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the environmental predictors at Wave I by gender. Several trends are evident. Demographically, the sample included slightly fewer males than females, and Add Health’s oversample of minorities was apparent with all non-White racial/ethnic groups representing higher proportions of the sample than the national population. Respondents were primarily of high school age in Wave I, and both genders generally reported comparable levels of perceived social support. Measures of SES indicated that respondent’s mean yearly household income was approximately $45,000–$50,000 and the mean parental educational attainment was approximately a high school degree. Finally, SLEs were more frequently reported by males (mean = 2.75) than females (mean = 1.85).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, environmental predictors

| Variable | Male (n = 922) | Female (n = 987) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

| White | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 |

| Black | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Asian | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 |

| American Indian | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0 | 1 |

| Other Race | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 16.12 | 1.65 | 12 | 21 | 16.01 | 1.66 | 12 | 20 |

| Social Support | 4.04 | 0.54 | 1.7 | 5 | 4.07 | 0.54 | 1.4 | 5 |

| Parental Education (mean) | 6.01 | 1.80 | 1 | 9 | 5.84 | 1.81 | 2 | 9 |

| Household income | 45.36 | 45.53 | 0 | 999 | 50.28 | 61.68 | 0 | 999 |

| SLEs | 2.75 | 2.87 | 0 | 20 | 1.85 | 2.15 | 0 | 17 |

Table 2 shows the number of significant gene, gene × age and gene × age2 effects at various q-value (i.e., multiple testing adjusted p-value) thresholds. Thus, the first row of Table 2 show that for the primary outcome, the 9 item CES-D average, 6 coefficients were significant at q < 0.1 out of 207 coefficients tested. All significant results from the primary results were for models examining DRD4 in the full sample. The sensitivity analyses of alternate CES-D specifications indicated that out approximately 621 parameters tested, 2 effects were significant at q < 0.1. This indicates that there were a small number of effects with p-values significantly lower than expected by chance given the number of tests, suggesting the presence of true effects.

Table 2.

Number of significant candidate gene effects on depressive symptom trajectories at various q-value thresholds

| Full Sample (no MAOA) | Males (MAOA) | Females (MAOA) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Outcome | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 |

| CES-D 9 item avg | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CES-D 9 item factor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CES-D 3 item avg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CES-D 3 item factor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 3 describes the strongest candidate gene effects on depressive symptom trajectories detected in the analysis (q < 0.1, hereafter referred to as “significant”). The first 6 and latter 2 rows describe significant findings for the primary and sensitivity outcomes, respectively. Findings from both sets of outcomes are sorted by p-values in ascending order. All significant findings involved either DRD4 5R allele in the full sample or MAOA 3.5R genotype among males.

Table 3.

Candidate gene effects on depressive symptom trajectories with q-values < 0.1

| CES-D Specification | Sample | Coefficient | b | se | z stat | p-value | q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 Item Avg | Full | DRD4 # 5R × Age | −0.118 | 0.039 | −3.042 | 0.002 | 0.067 |

| 9 Item Avg | Full | DRD4 no 5R × Age | 0.118 | 0.039 | 3.024 | 0.002 | 0.067 |

| 9 Item Avg | Full | DRD4 5R/other × Age | −0.117 | 0.039 | −2.991 | 0.003 | 0.067 |

| 9 Item Avg | Full | DRD4 # 5R × Age Sq | 0.007 | 0.003 | 2.982 | 0.003 | 0.067 |

| 9 Item Avg | Full | DRD4 no 5R × Age Sq | −0.007 | 0.003 | −2.975 | 0.003 | 0.067 |

| 9 Item Avg | Full | DRD4 5R/other × Age Sq | 0.007 | 0.003 | 2.956 | 0.003 | 0.067 |

|

| |||||||

| 3 Item Factor Score | Male | MAOA 3.5R × Age Sq | −0.016 | 0.006 | −2.789 | 0.005 | 0.069 |

| 3 Item Factor Score | Male | MAOA 3.5R × Age | 0.209 | 0.078 | 2.667 | 0.008 | 0.069 |

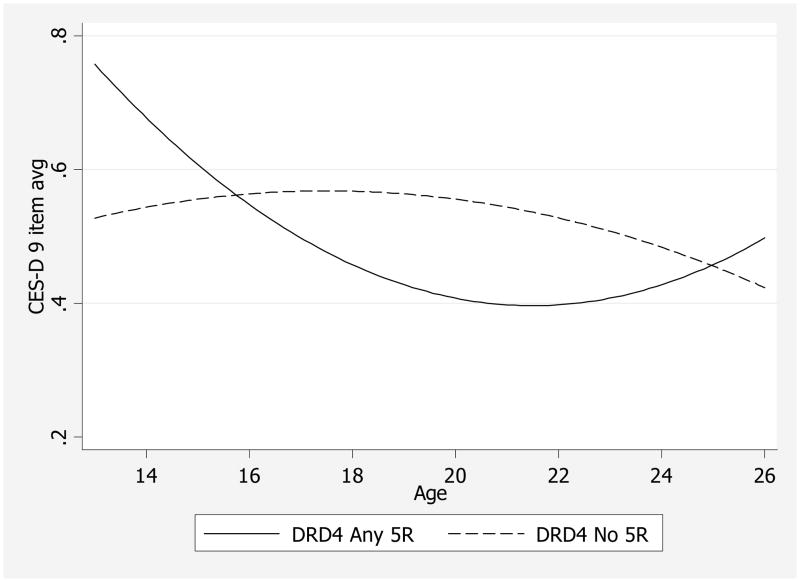

All significant findings in the full sample regard the DRD4 5R allele. Results indicate that individuals with the relatively uncommon 5R DRD4 allele (2.87%10 of the full sample, n = 161) experience unique trajectories of depressive symptoms across the period, characterized by U-shaped depressive symptom development, with relatively high levels as pre-teens at baseline, declining through adolescence, and rising in young adulthood. As illustrated in Figure 2, this trajectory is roughly opposite the normative, inverted U-shaped pattern commonly seen across the period. This was found for various specifications of the DRD4 5R allele for the primary outcome.11 Table 4 shows all estimates from the DRD4 no 5R allele model for each of the 4 outcome specifications. P-values were lowest for the primary 9 item average CES-D specifications (p = 0.002 and 0.003 for gene × ageand gene × age2 coefficients, respectively), but gene × age and gene × age2 interaction terms were also p < .01 for all 3 sensitivity CES-D specifications. Additional sensitivity analyses also supported the robustness of this finding. As shown in Appendix C, square root transformation of the CES-D to improve the normality of the distribution and reduce the influence of outliers substantially increased the significance of the parameters of interest (p < 0.001 for gene × ageand gene × age2 coefficients for all 4 CES-D specifications). Overall, these results suggest, with a high degree of confidence, that individuals with the DRD4 5R genotype exhibit a unique trajectory, characterized by relatively low depressive symptom levels in adolescence and relatively high levels in early adulthood.

Figure 2.

Depressive symptom age trajectory differences between DRD4 5R carriers and others

Table 4.

Parameter estimates of linear mixed models among full sample: Effects of DRD4 5R genotype on depressive symptom trajectories for 4 CES-D specifications

| 9 item avg | 9 item factor | 3 item avg | 3 item factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRD4 no 5R | −0.344* (0.012) | −0.260* (0.021) | −0.385* (0.035) | −0.300* (0.030) |

| DRD4 no 5R * Age | 0.118** (0.002) | 0.093** (0.004) | 0.145** (0.006) | 0.115** (0.004) |

| DRD4 no 5R * Age Sq | −0.007** (0.003) | −0.006** (0.005) | −0.009** (0.008) | −0.007** (0.005) |

| Female | 0.124*** (0.000) | 0.106*** (0.000) | 0.165*** (0.000) | 0.122*** (0.000) |

| Hispanic | 0.034 (0.174) | 0.022 (0.269) | 0.044 (0.154) | 0.025 (0.274) |

| Black | 0.066** (0.005) | 0.048** (0.007) | 0.053 (0.056) | 0.040 (0.057) |

| Asian | 0.156*** (0.000) | 0.084** (0.003) | 0.100* (0.021) | 0.069* (0.036) |

| American Indian | 0.028 (0.622) | 0.037 (0.404) | 0.077 (0.261) | 0.041 (0.424) |

| Other Race | −0.008 (0.934) | −0.021 (0.773) | −0.041 (0.726) | −0.036 (0.680) |

| Age | −0.095* (0.013) | −0.058 (0.066) | −0.097 (0.063) | −0.072 (0.065) |

| Age Squared | 0.005 (0.052) | 0.004 (0.065) | 0.005 (0.118) | 0.005 (0.062) |

| Social Support | −0.224*** (0.000) | −0.156*** (0.000) | −0.201*** (0.000) | −0.153*** (0.000) |

| Parental Education (mean) | −0.026*** (0.000) | −0.015*** (0.000) | −0.019** (0.003) | −0.014** (0.004) |

| Household income (logged thousands) | −0.006 (0.626) | −0.006 (0.527) | −0.010 (0.473) | −0.009 (0.396) |

| SLE | 0.035*** (0.000) | 0.029*** (0.000) | 0.042*** (0.000) | 0.031*** (0.000) |

| Intercept | 0.843*** (0.000) | 0.474*** (0.000) | 0.627*** (0.001) | 0.449** (0.001) |

|

| ||||

| Random intercept SD (Household level) | 0.164*** (0.000) | 0.120*** (0.000) | 0.181*** (0.000) | 0.138*** (0.000) |

| Random intercept SD (Individual level) | 0.181*** (0.000) | 0.139*** (0.000) | 0.201*** (0.000) | 0.151*** (0.000) |

| Residual SD | 0.345*** (0.000) | 0.288*** (0.000) | 0.476*** (0.000) | 0.359*** (0.000) |

|

| ||||

| N | 5605 | 5605 | 5605 | 5605 |

| Log restricted likelihood | −2868.454 | −1750.175 | −4450.946 | −2879.465 |

P-values in parentheses

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Appendix C.

Parameter estimates of linear mixed models among full sample: Effects of DRD4 5R on square root transformed depressive symptom trajectories

| 9 item avg | 9 item factor | 3 item avg | 3 item factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRD4 no 5R | −0.281** (0.004) | −0.270** (0.002) | −0.395** (0.008) | −0.315** (0.007) |

| DRD4 no 5R * Age | 0.096*** (0.001) | 0.093*** (0.000) | 0.142** (0.001) | 0.116*** (0.001) |

| DRD4 no 5R * Age Sq | −0.006*** (0.000) | −0.006*** (0.000) | −0.009** (0.001) | −0.007*** (0.001) |

| Female | 0.074*** (0.000) | 0.079*** (0.000) | 0.129*** (0.000) | 0.104*** (0.000) |

| Hispanic | 0.020 (0.264) | 0.015 (0.333) | 0.031 (0.224) | 0.018 (0.374) |

| Black | 0.046** (0.005) | 0.040** (0.005) | 0.037 (0.116) | 0.033 (0.071) |

| Asian | 0.116*** (0.000) | 0.078*** (0.000) | 0.099** (0.007) | 0.077** (0.007) |

| American Indian | 0.010 (0.801) | 0.022 (0.521) | 0.045 (0.434) | 0.031 (0.487) |

| Other Race | 0.004 (0.953) | −0.011 (0.856) | −0.043 (0.656) | −0.017 (0.818) |

| Age | −0.081** (0.003) | −0.064** (0.008) | −0.105* (0.013) | −0.077* (0.019) |

| Age Squared | 0.004* (0.015) | 0.004** (0.005) | 0.006* (0.033) | 0.006** (0.006) |

| Social Support | −0.162*** (0.000) | −0.132*** (0.000) | −0.166*** (0.000) | −0.133*** (0.000) |

| Parental Education (mean) | −0.021*** (0.000) | −0.014*** (0.000) | −0.016** (0.002) | −0.011** (0.007) |

| Household income (logged thousands) | −0.007 (0.442) | −0.008 (0.281) | −0.018 (0.151) | −0.016 (0.090) |

| SLE | 0.023*** (0.000) | 0.021*** (0.000) | 0.029*** (0.000) | 0.023*** (0.000) |

| Intercept | 0.932*** (0.000) | 0.680*** (0.000) | 0.722*** (0.000) | 0.560*** (0.000) |

|

| ||||

| Random intercept SD (Household level) | 0.120*** (0.000) | 0.100*** (0.000) | 0.163*** (0.000) | 0.123*** (0.000) |

| Random intercept SD (Individual level) | 0.131*** (0.000) | 0.112*** (0.000) | 0.164*** (0.000) | 0.132*** (0.000) |

| Residual SD | 0.243*** (0.000) | 0.215*** (0.000) | 0.387*** (0.000) | 0.300*** (0.000) |

|

| ||||

| N | 5605 | 5605 | 5605 | 5605 |

| Log restricted likelihood | −954.728 | −208.220 | −3337.665 | −1917.378 |

P-values in parentheses

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

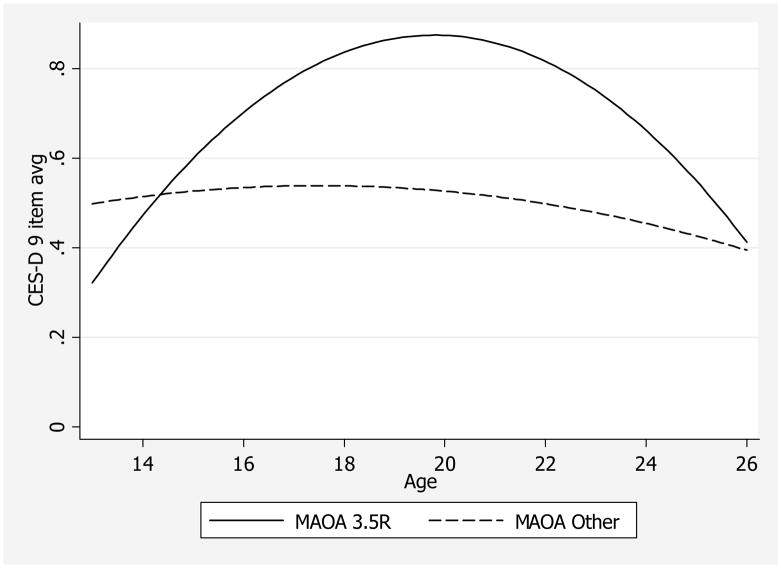

The final significant finding regards the uncommon MAOA 3.5R genotype among males (1.04% of the male sample, n = 28). This allele was found to significantly interact with age and age2 in both the 9 and 3 item CES-D factor score outcomes. As shown in Figure 3, compared to the normative pattern males with the 3.5R genotype, exhibited a similar, but markedly more curvilinear, inverted U-shaped trajectory. While only the 3 item factor score CES-D specifications satisfied the q < 0.1 threshold (p < 0.01 for 3 item factor score gene × age and gene × age2 coefficients), as shown in Table 5, gene × age and gene × age2 interaction terms were p < .05 for all CES-D specifications. These results were largely supported by additional sensitivity analyses showing significant results for square root transformed specifications of the CES-D (Appendix D).12 This finding suggests that males with the MAOA 3.5R genotype may experience a particularly distressful adolescence, before converging with their peers in early adulthood.

Figure 3.

Depressive symptom age trajectory differences between male carriers of the MAOA 3.5 genotype and other males

Table 5.

Parameter estimates of linear mixed models among male sample: Effects of MAOA 3.5R genotype on depressive symptom trajectories for 4 CES-D specifications

| 9 item avg | 9 item factor | 3 item avg | 3 item factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAOA 3.5R | −0.327 (0.135) | −0.319 (0.076) | −0.501 (0.094) | −0.485* (0.032) |

| MAOA 3.5R * Age | 0.165* (0.026) | 0.153* (0.013) | 0.228* (0.028) | 0.209** (0.008) |

| MAOA 3.5R * Age Sq | −0.014* (0.012) | −0.013** (0.006) | −0.019* (0.014) | −0.016** (0.005) |

| Hispanic | 0.049 (0.153) | 0.038 (0.150) | 0.066 (0.113) | 0.041 (0.185) |

| Black | 0.109*** (0.000) | 0.081*** (0.001) | 0.103** (0.006) | 0.080** (0.004) |

| Asian | 0.130** (0.004) | 0.079* (0.025) | 0.098 (0.075) | 0.074 (0.073) |

| American Indian | −0.053 (0.487) | −0.037 (0.542) | −0.022 (0.812) | −0.041 (0.562) |

| Other Race | 0.180 (0.145) | 0.122 (0.206) | 0.160 (0.288) | 0.105 (0.356) |

| Age | 0.022* (0.013) | 0.035*** (0.000) | 0.049*** (0.000) | 0.044*** (0.000) |

| Age Squared | −0.002*** (0.000) | −0.002*** (0.000) | −0.003*** (0.000) | −0.002*** (0.000) |

| Social Support | −0.170*** (0.000) | −0.115*** (0.000) | −0.144*** (0.000) | −0.110*** (0.000) |

| Parental Education (mean) | −0.021** (0.002) | −0.011* (0.045) | −0.012 (0.166) | −0.008 (0.180) |

| Household income (logged thousands) | −0.005 (0.757) | −0.001 (0.918) | −0.002 (0.932) | −0.001 (0.938) |

| SLE | 0.026*** (0.000) | 0.020*** (0.000) | 0.026*** (0.000) | 0.018*** (0.000) |

| Intercept | 0.471*** (0.000) | 0.191*** (0.000) | 0.201*** (0.000) | 0.115*** (0.001) |

| Random intercept SD (Household level) | 0.174*** (0.000) | 0.129*** (0.000) | 0.207*** (0.000) | 0.151*** (0.000) |

|

| ||||

| Random intercept SD (Individual level) | 0.168*** (0.000) | 0.126*** (0.000) | 0.169*** (0.000) | 0.134*** (0.000) |

| Residual SD | 0.302*** (0.000) | 0.252*** (0.000) | 0.428*** (0.000) | 0.322*** (0.000) |

| N | 2690 | 2690 | 2690 | 2690 |

| Log restricted likelihood | −1107.161 | −566.026 | −1907.771 | −1154.082 |

P-values in parentheses

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Appendix D.

Parameter estimates of linear mixed models among males: Effects of MAOA 3.5R on square root transformed depressive symptom trajectories

| 9 item avg | 9 item factor | 3 item avg | 3 item factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAOA 3.5R | −0.261 (0.110) | −0.212 (0.138) | −0.267 (0.301) | −0.270 (0.175) |

| MAOA 3.5R * Age | 0.136* (0.013) | 0.117* (0.015) | 0.164 (0.068) | 0.146* (0.033) |

| MAOA 3.5R * Age Sq | −0.012** (0.004) | −0.010** (0.005) | −0.016* (0.021) | −0.012* (0.016) |

| Hispanic | 0.033 (0.194) | 0.029 (0.190) | 0.056 (0.129) | 0.031 (0.273) |

| Black | 0.087*** (0.000) | 0.075*** (0.000) | 0.085** (0.010) | 0.072** (0.004) |

| Asian | 0.118*** (0.001) | 0.086** (0.003) | 0.113* (0.020) | 0.095* (0.011) |

| American Indian | −0.028 (0.631) | −0.018 (0.715) | −0.017 (0.832) | −0.024 (0.705) |

| Other Race | 0.138 (0.139) | 0.110 (0.168) | 0.149 (0.258) | 0.120 (0.240) |

| Age | 0.011 (0.110) | 0.029*** (0.000) | 0.040*** (0.000) | 0.045*** (0.000) |

| Age Squared | −0.001** (0.002) | −0.001*** (0.001) | −0.003*** (0.000) | −0.002** (0.005) |

| Social Support | −0.136*** (0.000) | −0.110*** (0.000) | −0.137*** (0.000) | −0.107*** (0.000) |

| Parental Education (mean) | −0.019*** (0.000) | −0.011* (0.016) | −0.011 (0.144) | −0.008 (0.162) |

| Household income (logged thousands) | −0.004 (0.726) | −0.003 (0.741) | −0.008 (0.632) | −0.010 (0.473) |

| SLE | 0.018*** (0.000) | 0.016*** (0.000) | 0.019*** (0.000) | 0.015*** (0.000) |

| Intercept | 0.633*** (0.000) | 0.383*** (0.000) | 0.278*** (0.000) | 0.192*** (0.000) |

|

| ||||

| Random intercept SD (Household level) | 0.130*** (0.000) | 0.110*** (0.000) | 0.200*** (0.000) | 0.145*** (0.000) |

| Random intercept SD (Individual level) | 0.133*** (0.000) | 0.109*** (0.000) | 0.129*** (0.000) | 0.116*** (0.000) |

| Residual SD | 0.223*** (0.000) | 0.197*** (0.000) | 0.369*** (0.000) | 0.283*** (0.000) |

|

| ||||

| N | 2690 | 2690 | 2690 | 2690 |

| Log restricted likelihood | −326.372 | 44.793 | −1523.281 | −825.471 |

P-values in parentheses

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Discussion

Leading developmental perspectives have long stressed the importance of accounting for temporality and life course variation in models of mental health. A primary insight of such perspectives is that the importance of various depressogenic factors fluctuates across developmental trajectories (Willett, Singer, & Martin, 1998; Elder, George, & Shanahan, 1996). The current study endeavors to wed this perspective to molecular genetic approaches to depressed affect. While psychiatric molecular genetics has made advances toward elucidating the link between genetic variation and depression, virtually all of this research has been atemporal. The weakness of this static perspective on the genetic determinants of depression is highlighted not only by developmental perspectives, but also by newer research within genetics showing that epigenetic mechanisms “turn genes off and on” in response to developmental and environmental cues (Whitelaw & Whitelaw, 2006). Using the Add Health genetic subsample, this study has addressed the issue of variation in genetic influences across adolescence and young adulthood through comprehensively testing the effects of five monoamine genes on depressive symptom trajectories, while employing FDR methods to control the risk of false discoveries.

The most promising associations detected were for interactions between the DRD4 dopamine receptor gene and age trajectory components in the full sample, and the MAOA VNTR promoter polymorphism and age trajectory components among males. Specifically, in the case of the DRD4 finding, individuals with the 5R allele were found to exhibit a roughly opposite trajectory compared to the normative inverted-U pattern. Thus, individuals with any 5R alleles were shown to have relatively low symptom levels through late adolescence, before experiencing increases in early adulthood. This pattern suggests that carriers of the DRD4 5R allele navigate their high school years with relative psychological ease compared to others, but begin to experience elevated distress as they transition into adult roles. Interpreting the molecular mechanism underpinning this finding is challenging, as very little is known about the 5R allele. Given its relatively low allele frequency (2.87% of the full sample), it has not been well-characterized in functional studies; thus, its gene expression profile is poorly understood.

However, one potential explanation of the DRD4 5R finding stems from association studies linking DRD4 to substance abuse. The DRD4 5R allele has shown evidence of association to abuse of various substances, including alcohol (e.g., Muramatsu, Higuchi, Muramaya, Matsushita, & Hayashida, 1996) and heroin (e.g., Li, Xu, Deng, Cai, Liu et al., 1997).13 And while these findings remain controversial (see Lusher, Chandler, & Ball, 2001), their potentially relevance to the current DRD4 finding becomes apparent when considering the life course context of substance abuse. Specifically, social control factors limiting access and abuse of substances, such as parental monitoring and legal obstacles, are relatively strong in adolescence. In the late teens and early twenties, after individuals leave their parents’ homes and can legally purchase alcohol, these social control mechanisms weaken and impediments to substance abuse are removed. Given that the upswing in depressive symptoms for DRD4 5R carriers observed here closely corresponds to the transition to adulthood, and that substance abuse and depression are highly correlated and frequently clinically comorbid (e.g., Grant & Harford, 1995), it seems plausible that loosening social control may be a key explanatory factor of the elevated distress levels observed among 5R carriers in young adulthood. However, as the direction of causality between substance abuse and depression is debated and likely reciprocal to some degree (e.g., Aneshensel & Huba, 1983), future research will be needed to replicate this finding and disentangle the putative web of causality between DRD4, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms. Moreover, given the dearth of knowledge into the 5R allele’s gene expression profile, basic molecular research will be necessary to validate the finding by characterizing the functionality of this uncommon variant.

The other notable substantive finding was an association between the MAOA 3.5R allele and depressive symptom trajectory components in the male sample. Specifically, males with the 3.5R genotype had more curvilinear symptom trajectories than the normative pattern, with higher peaks in late adolescence and sharper declines in early adulthood. Thus, males with the 3.5 genotype were shown to have a particular distressful time during high school and the subsequent transition to adulthood, but converge with their peers in early adulthood. This age variation in the influence of MAOA may explain inconsistencies in former MAOA-depression association results, which have shown both elevated depression levels among male carriers of the 3.5R and other long MAOA alleles (Du, Bakish, Ravindran, & Hrdina, 2004; Yu, Tsai, Hong, Chen, Chen et al., 2005), and also no significant association (Kunugi et al., 1999). Furthermore, the current results may shed light on results from a recent meta-analysis of six MAOA-depression association studies, which found a strong trend toward increased depression among carriers of the 3.5R and other long MAOA alleles falling just short of statistical significance (OR = 0.86; 95% CI: 0.74–1.01) (Lopez-Leon, Janssens, Ladd, Del-Favero, Claes, et al. 2008).14 Interestingly, this meta-analysis found strong evidence of heterogeneity in effect sizes across studies. Results of the current study offer a potential explanation for this heterogeneity, suggesting that age differences across samples may be driving effect differences.

In sum, this study has shown that individual variation in adolescent and young adult depressive symptom trajectories is partially explained by specific genetic variants. These findings advance developmental perspectives through both addressing perennial issues and raising new questions. Depressive affect has long been of particular interest to developmental psychopathologists due to its multifactorial etiology, encompassing psychological, social and biological factors (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998). In line with the tenants of this approach, we have explored the dynamic etiology of depressed affect by merging multiple levels of analysis and leveraging longitudinal trajectories to simultaneously examine the influence of specific genetic variants and environmental factors (Sroufe & Rutter, 1984; Zahn-Waxler, Klimes-Dougan & Slattery, 2000). The results inform long-standing issues of central importance in the developmental literature. For instance, as Rutter & Sroufe (2000) note, the increased frequency and intensity of depressed affect in adolescence is a primary feature of affective psychopathology and requires a developmental approach to elucidate its origin. Here we have shown that variation in monoaminergic genes strongly influences this pattern, predicting a particularly distressful adolescence for some (i.e., male MAOA 3.5R carriers), and relatively psychological ease in adolescence, followed by difficulty in young adulthood, for others (DRD4 5R carriers). Future developmental research would do well to continue examining the possibility that much of the adolescent elevation in depressed affect observed at the population level may be driven by genetically distinct subgroups.

This research also raises new questions germane to further developmental study. For instance, how do these polymorphisms exert affective influence? Given the temporal patterns observed, it is clear that some aspect of development moderates these genetic influences. It seems likely that fluctuations in gene expression levels, quite possibly epigenetically regulated, are involved (Reiss & Neiderhiser, 2000; Bergen, Gardner, and Kendler, 2007), but what drives these expression/epigenetic changes? Is this a predominately biological phenomenon, similar, and perhaps related, to puberty (see Eaves, Silberg, Foley, Bulik, Maes et al., 2003)? Or do social environmental changes associated with adolescence influence gene expression levels for risk variants? Applying a developmental approach to examining correlations and interactions of social risk and protective factors to the implicated variants could yield empirical answers to these questions. Furthermore, these are not issues of purely academic interest. As persuasively argued by Reiss and Neiderhiser (2000) the ability of social factors to buffer against genetic predispositions toward depressed affect has vital importance to intervention efforts. By more completely understanding the configurations of social and genetic factors contributing to depressed affect development, interventions can both identify genetic risk groups early on, and potentially modify environments to prevent psychopathological developmental cascades.

As is typical, this research is unlikely to be the final word on the topic. This investigation is limited by the number of waves of data, and therefore the trajectory length and age range, available. Additional waves of data, which are forthcoming, will allow an extension of our understanding of how depressive symptoms develop over a longer period of the life course. Future research could also benefit from increasing coverage of genetic variation. While candidate gene approaches are apt to remain important in GxE studies into the near future, there is a progressive movement in genetics toward more exploratory analyses examining genetic variation across the genome. These genome-wide association studies (GWAS) typically include over 500,000 genetic markers, and while still relatively uncommon in behavioral research, the rapidly decreasing cost of genotyping guarantees that such data will soon become available for longitudinal, behavioral surveys. This development will represent a paradigm shift in GxE studies, allowing analysis of social moderation of genetic influences on an unprecedented scale. However, it will also pose challenges to behavioral scientists as they join statistical geneticists in grappling with how to best analyze such massive datasets. While the FDR techniques employed here represent vanguard techniques for addressing the issues of multiple testing inherent to GWAS, this area will certainly remain an active research frontier into the foreseeable future.

Despite these limitations, the present study improves our understanding of depressive symptomatology in adolescence and young adulthood and advances a framework for future research in the area. Specifically, results show significant temporal variation in the effects of MAOA and DRD4 on depression. Beyond the substantive results, this study shows the value of combining temporally dynamic, developmental perspectives with comprehensive empirical statistical approaches to optimize the search for genetic influences across the life course. This can be seen from various aspects of the current study. First, without an exhaustive exploration of various allelic specifications beyond those conventionally assessed, highly significant associations for the 3.5R MAOA and 5R DRD4 alleles would not have been detected. Also, employing a developmental perspective to consider age variations in genetic enabled the detection of very strong nonlinear gene × age interactions that would have otherwise been missed. Finally, the use of FDR statistical methods allowed these comprehensive empirical explorations by controlling the risk of false discoveries—a major problem in genetic research (Colhoun et al., 2003), that behavioral scientists interested in incorporating genetic perspectives have yet to sufficiently address.

Footnotes

For continuity with former research, we retain the “DRD2” nomenclature for this polymorphism.

While Blazer and colleagues (1998) found racial measurement invariance across most items, see Perreira et al. (2005) for contrasting findings indicating widespread measurement invariance across racial groups for the CES-D.

When continuous measures are mean-centered, the intercept and age coefficients describe the mean trajectory in the sample. This is generally more substantively interesting than the age trajectory for (hypothetical) individuals with values equal to zero on all covariates, which is the interpretation when continuous predictors are left uncentered.

Former research comparing this coding approach with another in which only individuals identifying as one race/ethnic group were coded as such and all other individuals were coded as “multiracial” suggest that findings are generally robust across coding schemes (Adkins et al. 2009).

The effects of age and age2, as well as those of all other predictors, are modeled as fixed effects. This specification was chosen to facilitate model optimization.

Allelic combinations with very low frequencies (n < 0.5% of full sample; i.e., n < 28 observations) were not included in the analysis, as outliers were overly influential in these cases. This criterion eliminated 11 allelic combinations from the analysis.

This robustness of FDR to correlated tests has been demonstrated specifically in the context of candidate gene studies, with simulation studies showing desirable properties in scenarios very similar to the current analysis (i.e., multiple specifications of the same alleles) (van den Oord 2005).

This threshold may be considered conservative as many candidate gene (Saccone, Hinrichs, Saccone, Chase, Konvicka et al., 2007; Sullivan, Neale, van den Oord, Miles, Neale et al., 2004) and genome-wide association studies (e.g., McClay, Adkins, Aberg, Stroup, Perkins et al., 2009; van den Oord et al., 2008) consider markers passing a much less rigorous threshold (e.g., q < 0.5) “potentially interesting”.

The percentage given here (2.87%) refers to sample proportion having any 5R alleles on either chromosome, as opposed to the percentage given in the genetic measures summary (1.45%), which refers to the percentage of 5R among all variant on both chromosome.

Given that there were only 2 observations with the DRD4 5R/5R genotype, the no 5R, # 5R, and 5R/other specifications are very highly correlated.

With the exception of the gene × age coefficient, which became marginally nonsignificant (p = 0.068) in the 3 item square root transformed CES-D model.

In some cases coded together with other “long” alleles.

Reverse coded –i.e., MAOA 3.5 and 4 coded 0 and other MAOA alleles coded 1.

References

- Adkins DE, Wang V, Dupre ME, van den Oord EJCG, Elder GH. Structure and Stress: Trajectories of Depression across Adolescence and Young Adulthood. Social Forces. 2009;88:31–60. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins DE, Wang V, Elder GH. Stress processes and trajectories of depressive symptoms in early life: Gendered development. In: Turner HA, Schieman S, editors. Advances in Life Course Research: Stress processes across the life course. Elsevier JAI; 2008. pp. 107–134. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Huba GJ. Depression, Alcohol-Use, and Smoking over One Year - a 4-Wave Longitudinal Causal Model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92:134–150. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguelova M, Benkelfat C, Turecki G. A systematic review of association studies investigating genes coding for serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter: I. Affective disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8:574–591. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghari V, Sanyal S, Buchwaldt S, Paterson A, Jovanovic V, Van Tol HHM. Modulation of Intracellular Cyclic-Amp Levels by Different Human Dopamine D4 Receptor Variants. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1995;65:1157–1165. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach AWJ, Lan NC, Johnson DL, Abell CW, Bembenek ME, Kwan SW, Seeburg PH, Shih JC. Cdna Cloning of Human-Liver Monoamine Oxidase-a and Oxidase-B - Molecular-Basis of Differences in Enzymatic-Properties. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:4934–4938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbot W, Dupressoir A, Lazar V, Heidmann T. Epigenetic regulation of an IAP retrotransposon in the aging mouse: progressive demethylation and de-silencing of the element by its repetitive induction. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:2365–2373. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.11.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen SE, Gardner CO, Kendler KS. Age-related changes in heritability of behavioral phenotypes over adolescence and young adulthood: A meta-analysis. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:423–433. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Hays JC, Simonsick EM, Saunders WB. Symptoms of depression among community-dwelling elderly African-American and White older adults. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:1311–1320. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchetta A, Piccardi MP, Palmas MA, Oi A, Del Zompo M. Family-based association study between bipolar disorder and DRD2, DRD4, DAT, and SERT in Sardinia. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1999;88:522–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, Taylor A, Poulton R. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R. Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Rainnie DG, Greene RW, Tonegawa S. Abnormal Fear Response and Aggressive-Behavior in Mutant Mice Deficient for Alpha-Calcium-Calmodulin Kinase-Ii. Science. 1994;266:291–294. doi: 10.1126/science.7939668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):221–41. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colhoun HM, McKeigue PM, Smith GD. Problems of reporting genetic associations with complex outcomes. Lancet. 2003;361:865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE. Stress and Life Events During Childhood and Adolescence. Clinical Psychology Review. 1987;7:275–302. [Google Scholar]