Abstract

Purpose

The Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up (COG-LTFU) Guidelines use consensus-based recommendations for exposure-driven, risk-based screening for early detection of long-term complications in childhood cancer survivors. However, the yield from these recommendations is not known.

Methods

Survivors underwent COG-LTFU Guideline–directed screening. Yield was classified as negligible/negative (< 1%), intermediate (≥ 1% to < 10%), or high (≥ 10%). For long-term complications with high yield, logistic regression was used to identify subgroups more likely to screen positive.

Results

Over the course of 1,188 clinic visits, 370 childhood cancer survivors (53% male; 47% Hispanic; 69% leukemia/lymphoma survivors; median age at diagnosis, 11.1 years [range, 0.3 to 21.9 years]; time from diagnosis, 10.5 years [range, 5 to 55.8 years]) underwent 4,992 screening tests. High-yield tests included thyroid function (hypothyroidism, 10.1%), audiometry (hearing loss, 22.6%), dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans (low bone mineral density [BMD], 23.2%), serum ferritin (iron overload, 24.0%), and pulmonary function testing/chest x-ray (pulmonary dysfunction, 84.1%). Regression analysis failed to identify subgroups more likely to result in high screening yield, with the exception of low BMD (2.5-fold increased risk for males [P = .04]; 3.3-fold increased risk for nonobese survivors [P = .01]). Screening tests with negligible/negative (< 1%) yield included complete blood counts (therapy-related leukemia), dipstick urinalysis for proteinuria and serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine (glomerular defects), microscopic urinalysis for hematuria (hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder cancer), ECG (anthracycline-related conduction disorder), and hepatitis B and HIV serology.

Conclusion

Screening tests with a high yield are appropriate for risk groups targeted for screening by the COG-LTFU Guidelines. Elimination of screening tests with negligible/negative yield should be given consideration.

INTRODUCTION

One third of childhood cancer survivors report severe or life-threatening complications 30 years after diagnosis.1 Clear relationships exist between specific therapeutic exposures and long-term complications2–5; surveillance for and early detection of these complications in high-risk populations can potentially reduce morbidity, given availability of appropriate interventions.6

In 2002, the Institute of Medicine called for guidelines to direct long-term follow-up care of childhood cancer survivors.7 The Children's Oncology Group (COG) responded by developing the COG Long-Term Follow-Up (COG-LTFU) Guidelines, using the known association between therapeutic exposures and long-term complications to create risk groups that would need screening; although the definition of at-risk populations was evidence based, the modality and intensity of screening were consensus based (Table 1).8 The COG-LTFU Guidelines have been in use since 2003. However, the yield from these consensus-based screening recommendations is not known. It is also not known whether there are certain subgroups of survivors who could benefit from lower or higher intensities of screening.

Table 1.

COG Long-Term Follow-Up Screening Recommendations and Definitions of Positive Screening Tests

| Therapeutic Exposure | Potential Late Effect | COG-Recommended Screening | Positive Screening Test Definition Used for This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkylators, topoisomerase II inhibitors, autologous HCT | t-MDS/AML | CBC yearly × 10 years after exposure | Abnormal CBC (WBC < 4,000/μL, hemoglobin < 10 gm/dL, platelet count < 150,000/μL, or blasts present on differential) and pathology report confirming diagnosis of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome or AML |

| Cisplatin, carboplatin, ifosfamide, methotrexate, radiation to kidney (any dose) | Renal insufficiency | BUN/creatinine: baseline | Calculated GFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 according to Schwartz et al9 formula (for patients age ≤ 18 years) or Cockroft-Gault formula10 (for patients age > 18 years) |

| UA for protein: yearly | Proteinuria ≥ 2+11 | ||

| Cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, pelvic irradiation (any dose) | Hemorrhagic cystitis | UA for microscopic hematuria: yearly | > 5 RBCs/high power field12 |

| Bladder cancer | UA for microscopic hematuria: yearly | > 5 RBCs/high power field and pathology report confirming diagnosis of bladder cancer12 | |

| Antimetabolites, abdominal irradiation ≥ 30 Gy | Hepatic toxicity | LFTs (ALT, AST, bilirubin): baseline | ALT ≥ 2× ULN or AST ≥ 2× ULN or total bilirubin > 1.5 mg/dL (ULN: ALT, 56 U/L; AST, 46 U/L)13 |

| Cisplatin, carboplatin, ifosfamide | Renal tubular injury | Potassium/magnesium/phosphorous: baseline | ≥ 2 of following: serum potassium < 3.5 mmol/L, serum magnesium < 1.6 mg/dL, and serum phosphorus < 2.6 mg/dL14 |

| Neck irradiation (any dose) | Hypothyroidism | TSH, free T4: yearly | TSH > 4.5 mIU/L15 |

| Cisplatin, myeloablative carboplatin, ear irradiation ≥ 30 Gy | Hearing loss | Audiometry: baseline (and every 5 years for irradiation; yearly if age < 10 years) | Chang et al16 grade 1 to 4 hearing loss in better ear |

| Anthracyclines | Cardiac conduction disorder (prolonged QT interval) | ECG: baseline and as clinically indicated | Corrected QT interval: males: > 450 msec; females: > 470 msec |

| Anthracyclines | Cardiac left ventricular systolic dysfunction | Echocardiogram: periodically (every 1 to 5 years) as indicated based on anthracycline dose and age at treatment | Ejection fraction < 55% or fractional shortening < 28% |

| Bleomycin, busulfan, nitrosoureas, chest irradiation (any dose), allogeneic HCT with cGVHD | Pulmonary fibrosis | Chest x-ray: baseline | Radiology report indicates scarring of pulmonary parenchyma and/or pleura per chest x-ray report17 |

| Pulmonary dysfunction (restrictive, obstructive, and/or diffusion defect) | PFTs: baseline | ≥ 1 of following: obstructive defect (FEV1 < 80% predicted), restrictive defect (TLC < 80% predicted), diffusion defect (DLCO < 80% predicted)17 | |

| Methotrexate, corticosteroids, HCT | Low bone mineral density | DEXA scan | Patients age < 20 years: Z score > 2 SD below mean; patients age ≥ 20 years: T score > 1 SD below mean18 (screening limited to patients age ≥ 18 years; 65 patients age < 18 years not tested) |

| HCT | Iron overload | Serum ferritin: baseline | Serum ferritin > 500 ng/mL19 |

| Blood products before 1972 | Chronic hepatitis B infection | Hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody: baseline | Positive hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody |

| Blood products before 1993 | Chronic hepatitis C infection | Hepatitis C antibody and PCR: baseline | Positive hepatitis C antibody with confirmatory PCR |

| Blood products between 1977 and 1985 | HIV infection | HIV serology: baseline | Positive HIV 1 and 2 antibody screen (ELISA) confirmed by Western blot |

| Alkylators, pelvic irradiation (any dose) | Gonadal dysfunction (females): premature menopause | FSH: baseline at age 13 years and as clinically indicated | FSH ≥ 13 mIU/mL20 |

| Alkylators, pelvic irradiation ≥ 20 Gy | Gonadal dysfunction (males): Leydig cell dysfunction | Serum testosterone: baseline at age 14 years and as clinically indicated | Serum testosterone < lower limit of normal based on Tanner stage: 1, < 11; 2, < 18; 3, < 100; 4, < 200; and 5/adult, < 275 ng/mL21 |

| Chest/thorax irradiation ≥ 20 Gy | Breast cancer | Mammogram: yearly | Abnormal mammogram (BI-RADS category 3 to 5) and pathology report confirming diagnosis of breast cancer22 |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BI-RADS, Breast Imaging Data Reporting System; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; cGVHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; COG, Children's Oncology Group; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; DLCO, diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; LFT, liver function test; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PFT, pulmonary function test; SD, standard deviation; T4, thyroxine; TLC, total lung capacity; t-MDS/AML, therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; UA, urinalysis; ULN, upper limit of normal.

In this study, we aimed to determine the yield of the COG-LTFU Guidelines in identifying key long-term complications in a cohort of childhood cancer survivors who underwent guideline-directed screening during routine follow-up care. Specifically, we aimed to identify populations of survivors with high, intermediate, or low yield and to use the information obtained to refine the COG-LTFU Guidelines.

METHODS

Study Participants

Participants were childhood cancer survivors enrolled in the institutional review board–approved City of Hope LTFU Clinic for Childhood Cancer Survivors (LTFU Clinic) aimed at providing comprehensive long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors. Eligibility for inclusion in the current analysis was as follows: diagnosis of pediatric cancer at age ≤ 21 years, treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy and/or hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), ≥ 5 years from diagnosis, remission for ≥ 2 years after completion of cancer therapy, and participation in the LTFU Clinic. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant or his or her legal representative.

Procedures

Risk-based screening.

Medical records were reviewed to determine each participant's therapeutic exposures, including cumulative doses of chemotherapy, radiation doses/fields, surgical procedures, and HCT-related details. A computerized algorithm was used to generate a list of screening tests, tailored to each patient's specific therapeutic exposures, sex, age, and time since exposure; the list of recommendations was reviewed and confirmed by a clinician to assure precise adherence to COG-LTFU Guidelines. Participants underwent screening evaluations in the LTFU Clinic and were invited to return annually for follow-up.

Identification of long-term complications.

Results of all screening tests were defined a priori (Table 1) and classified as positive, negative, or indeterminate by two study team members (W.L., O.T.). Participants were excluded from the analysis for the targeted complication if they had been diagnosed with the targeted complication before their first screening visit (the outcome was excluded from the screening yield analysis but included in the prevalence report), if the positive screening test was inevaluable (eg, hematuria in urine specimen obtained from menstruating female survivor), or if the positive screening result was because of an unrelated condition (eg, thrombocytopenia related to immune thrombocytopenic purpura). Medication records were reviewed to clarify false-negative screening (eg, normal thyroid-stimulating hormone in patient receiving thyroid replacement therapy for previously diagnosed hypothyroidism). Indeterminate test results that could not be classified after a second level of review were referred to the senior researcher (S.B.) for final arbitration.

Statistical Analyses

Screening yield.

Screening yield was defined as the ratio of the number of positive screening tests in evaluable at-risk previously undiagnosed patients to the total number of evaluable screening tests completed. Screening yield was classified as negligible/negative (< 1%), intermediate (≥ 1% to < 10%), or high (≥ 10%) based on the prevalence of the targeted late effects reported in the literature (detailed rationale for the classification is provided in the Appendix, online only). Clinical and demographic characteristics (sex, race, diagnosis, age at diagnosis, age at testing, time since diagnosis, therapeutic exposures that triggered screening) were summarized for the screened population for each complication. For long-term complications with high yield, logistic regression techniques were used to identify subgroups (defined by relevant demographic and clinical characteristics) most likely to screen positive. The following variables were examined for their association with yield: primary cancer diagnosis, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, age at participation, sex, race/ethnicity, and HCT (none, autologous, allogeneic with or without chronic graft-versus-host disease) for all analyses; in addition, the following variables were examined for specific outcomes: platinum chemotherapy and radiation field involving the ear (ototoxicity); body mass index (pulmonary dysfunction, low bone mineral density [BMD]); bleomycin, lomustine, carmustine, busulfan, and chest irradiation/total-body irradiation (pulmonary dysfunction); prednisone, dexamethasone, methotrexate, and gonadal dysfunction (low BMD); and number of relapses (iron overload). The final multivariate regression models always included primary diagnosis, time since diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, and age at diagnosis or study participation; additional variables that were significant at P < .2 in the univariate analysis were also retained in the final models.

Prevalence.

Prevalence was defined as the ratio of at-risk survivors newly identified with the targeted complication by screening, plus the number of at-risk survivors diagnosed with the complication before their first screening visit (but after receiving cancer therapy), to the total number of at-risk survivors.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

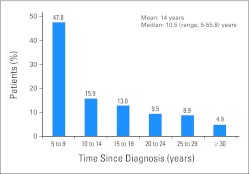

Between October 1, 2003, and October 31, 2010, 370 childhood cancer survivors underwent COG-LTFU Guideline–directed evaluations; of these, 59 underwent one evaluation, 89 underwent two evaluations, and 222 underwent more than two annual evaluations. Median age at diagnosis was 11.1 years (range, 0.3 to 21.9 years); median follow-up was 10.5 years (range, 5 to 55.8 years); median age at first evaluation was 23.9 years (range, 5.3 to 57.2 years). Fifty-three percent of participants were male; 47% were Hispanic; 69% had a primary diagnosis of leukemia or lymphoma. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 2 and detailed by time from diagnosis (in 5-year increments) in Appendix Table A1 and Appendix Figure A1 (online only).

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort size | 370 | |

| Age, years | ||

| Diagnosis | ||

| Median | 11.1 | |

| Range | 0.3-21.9 | |

| Study participation | ||

| Median | 23.9 | |

| Range | 5.3-57.2 | |

| Time from diagnosis to study entry, years | ||

| Median | 10.5 | |

| Range | 5-55.8 | |

| Male sex | 195 | 52.7 |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 30 | 8.1 |

| Black | 12 | 3.2 |

| Hispanic | 174 | 47.0 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 141 | 38.1 |

| Other | 13 | 3.5 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 124 | 33.5 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 29 | 7.8 |

| CNS tumor | 17 | 4.6 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 58 | 15.7 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 39 | 10.5 |

| Germ cell tumor | 15 | 4.1 |

| Wilms tumor | 15 | 4.1 |

| Bone and soft tissue sarcoma | 46 | 12.4 |

| Other | 27 | 7.3 |

| Any chemotherapy | 351 | 94.9 |

| Any radiation | 206 | 55.7 |

| HCT | 96 | 25.9 |

Abbreviation: HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Screening Yield

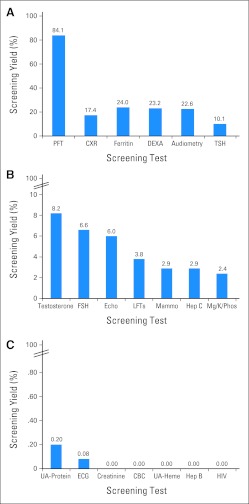

A total of 5,062 screening recommendations were generated by the computerized algorithms for the 370 participants over the course of 1,188 annual evaluations in the LTFU Clinic. All survivors in the cohort underwent at least one screening test. Of the 5,062 recommended tests, 4,992 (98.6%) were completed, and 4,954 (99.2%) of the 4,992 completed tests were evaluable (Appendix Table A2, online only). Eight of the evaluable tests (0.16%) were deemed indeterminate during the initial two levels of review and were referred to the senior researcher, who provided final arbitration. Screening yield is shown in Figures 1A to 1C and in Appendix Table A3 (online only). Clinical characteristics of the at-risk populations and corresponding screening results are summarized in Appendix Table A4 (online only).

Fig 1.

Screening yield (A) ≥ 10%, (B) ≥ 1% to < 10%, and (C) < 1%. CBC, complete blood count; CXR, chest x-ray; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; Echo, echocardiogram; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone (females only); Heme, microscopic hematuria; Hep B, hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody; Hep C, hepatitis C antibody and confirmatory polymerase chain reaction; LFTs, liver function tests; Mammo, mammogram; Mg/K/Phos, magnesium/potassium/phosphorous; PFT, pulmonary function test; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; UA, urinalysis.

High yield.

Screening per COG-LTFU Guidelines resulted in high yield (≥ 10%) for the following complications: hypothyroidism (10.1%), hearing loss (22.6%), low BMD (23.2%), iron overload (24%), and pulmonary dysfunction (84.1%).

Intermediate yield.

Screening resulted in intermediate yield (1% to < 10%) for the following complications: renal tubular dysfunction (2.4%), chronic hepatitis C infection (HCV; 2.9%), breast cancer (2.9%), hepatic dysfunction (3.8%), left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction (6.0%), premature menopause (6.6%), and Leydig cell dysfunction (8.2%).

Negligible/negative yield.

Screening resulted in negligible/negative yield (< 1%) for the following: renal glomerular dysfunction (0.2% by urinalysis; 0% by serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine), anthracycline-related cardiac conduction disorder (0.08%), therapy-related myelodysplasia/acute myeloid leukemia [t-MDS/AML] (0%), hemorrhagic cystitis (0%), bladder cancer (0%), chronic hepatitis B infection (0%), and HIV (0%).

Populations With the Highest Probability for High Yield From Screening

Multivariable logistic regression analyses performed for complications with high yield failed to identify subgroups more likely to result in high screening yield, with the exception of low BMD (2.5-fold increased risk for male compared with female survivors [27.2% v 18.4%; P = .04]; 3.3-fold increased risk for nonobese compared with obese survivors [29.2% v 10.5%; P = .01].

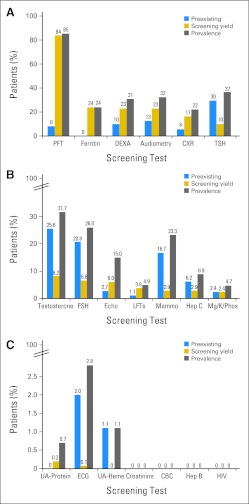

Prevalence

Pre-existing conditions diagnosed in > 5% of at-risk participants before initiation of screening included chronic HCV infection (6.2%), pulmonary dysfunction (8.2%), low BMD (10%), hearing loss (12.7%), breast cancer (16.7%), gonadal dysfunction (female, 20.8%; male, 25.6%), and hypothyroidism (29.6%). Conditions with high (> 10%) overall prevalence (pre-existing conditions plus conditions newly identified by screening) in at-risk patients included LV systolic dysfunction (15.0%), breast cancer (23.3%), iron overload (24.0%), gonadal dysfunction (female, 26.0%; male, 31.7%), low BMD (30.8%), hearing loss (32.4%), hypothyroidism (36.7%), and pulmonary dysfunction (85.4%). Prevalence of long-term complications is summarized in Figures 2A to 2C and Appendix Table A3 (online only).

Fig 2.

Pre-existing conditions, screening yield, and overall prevalence for (A) high-yield (≥ 10%), (B) intermediate-yield (≥ 1% to < 10%), and (C) negligible/negative-yield (< 1%) screening tests. CBC, complete blood count; CXR, chest x-ray; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; Echo, echocardiogram; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone (females only); Heme, microscopic hematuria; Hep B, hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody; Hep C, hepatitis C antibody and confirmatory polymerase chain reaction; LFTs, liver function tests; Mammo, mammogram; Mg/K/Phos, magnesium/potassium/phosphorous; PFT, pulmonary function test; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; UA, urinalysis.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study that reports the yield of nearly 5,000 screening tests following meticulous application of COG-LTFU screening guidelines in a cohort of childhood cancer survivors. Using this approach, we were able to identify screening tests with high and low yield in the context of the prevalence of these conditions in the at-risk populations, with implications for guideline refinement. Conditions with a high prevalence included LV systolic dysfunction (15%), iron overload (24%), low BMD (31%), hearing loss (32%), hypothyroidism (37%), and pulmonary dysfunction (85%); these findings are consistent with previous reports (pulmonary toxicity [13% to 87%],4,23–28 iron overload [40% to 93%],29–31 low BMD [21% to 65%],32–34 hearing loss [25% to 83%],35–39 and hypothyroidism [21% to 57%]40–45). However, in our study, we differentiated screening yield from pre-existing conditions, with both contributing to the overall prevalence.

Screening according to the COG-LTFU Guidelines resulted in high yield for several conditions, likely a reflection of the generally asymptomatic nature of these conditions in the early stage and the fairly long latency after exposure to specific therapeutic agents. Thus, although pulmonary dysfunction had already been diagnosed in 8% of the patients before screening in this clinic, it was newly identified in 84% of at-risk patients screened, demonstrating the necessity to screen those at risk so that appropriate preventive/interventional measures can be instituted to decelerate the progression and, in some, reverse the process. Similarly, low BMD had been previously diagnosed in 10% of the at-risk population, but screening resulted in identification of low BMD in 23% of the remaining patients at risk. Hypothyroidism generally has a short latency after irradiation, but cancer survivors remain at risk for many years. In the current study, 30% of at-risk patients had already been diagnosed with hypothyroidism at the time of study entry, and screening resulted in a diagnosis of hypothyroidism in 10% of the remaining at-risk patients. Iron overload is generally an asymptomatic condition until organ (eg, cardiac, liver) dysfunction occurs as a result of high iron burden over a prolonged period of time. It is therefore not surprising that no patients were identified with iron overload before study entry, and screening resulted in identification of 24% with iron overload. Hearing loss, generally related to platinum agents with or without radiation, typically has a short latency, but it can be diagnosed several years after therapeutic exposure, because platinum-related hearing loss initially affects the higher frequencies, and patients/families may not identify the hearing loss unless it affects day-to-day activities. In our study, 13% of the patients were diagnosed with hearing loss before study entry; screening resulted in 23% of the remaining at-risk patients being newly identified with hearing loss. Although standard therapeutic interventions are readily available and likely to benefit survivors with some of these high-yield conditions (eg, thyroid replacement therapy for hypothyroidism,46 auditory amplification for hearing loss,47 calcium supplementation and bone loading for low BMD48), interventions for asymptomatic patients with other conditions (eg, iron overload,29 pulmonary dysfunction49) are currently under investigation. In particular, for the 84% of survivors who received potentially pulmonary toxic therapy and were identified with previously unrecognized subclinical pulmonary dysfunction on screening evaluation, the implications of these findings are as yet unknown. However, because pulmonary function declines with age, these findings may portend future symptomatic pulmonary dysfunction as this population ages50 and thus may have implications for the need to develop interventions to preserve or enhance pulmonary function in this vulnerable population.

Screening determinations used in this study were based on therapeutic exposures already identified by the COG-LTFU Guidelines as placing patients at risk for the targeted complications. The generally negative findings for subgroups with a higher likelihood to screen positive lend support to the appropriateness of risk groups targeted for screening by the COG Guidelines. The only exceptions were the identification of male sex and lack of obesity to be associated with an increased probability of low BMD; these findings are consistent with previously reported observations.51–56

The intermediate yield for renal tubular dysfunction (2%), chronic HCV infection (3%), breast cancer (3%), hepatic dysfunction (4%), LV systolic dysfunction (6%), premature menopause (7%), and Leydig cell dysfunction (8%) is probably a reflection of the low overall incidence of some complications (eg, hepatic dysfunction); the long latency of others (eg, breast cancer, LV systolic dysfunction; the yield will likely increase as follow-up matures); the short latency associated with some conditions (eg, gonadal dysfunction), such that the conditions were diagnosed before study entry; or the combination of short latency and self-resolving course (eg, renal tubular dysfunction), such that by the time the patients entered this study, the condition was no longer present. These scenarios are confirmed by the wide range of the overall prevalence of the intermediate-yield conditions (renal tubular injury, 5%; Leydig cell dysfunction, 32%).

The prevalence of renal tubular and LV systolic dysfunction in our cohort is comparable to that reported by others. In contrast, the higher prevalence of breast cancer (23%) in our cohort, compared with other studies (6% to 12%),57 may be the result of inclusion of patients in the previous studies regardless of age or therapeutic exposure, whereas patients included in our study were targeted for screening based on therapeutic exposures (chest irradiation dose ≥ 20 Gy), current age (≥ 25 years), and time from therapy (≥ 8 years after irradiation).

The low prevalence of hepatotoxicity (5%) in our study is similar to that reported by others.58,59 The risk for acquisition of transfusion-related HCV infection in the United States extended through 1992,60 and reports of seroprevalence have ranged from 2% to 53%.61–64 The prevalence of chronic HCV infection (9%) seen in our study is comparable to that reported by St Jude Children's Research Hospital.64 Given the potential morbidity associated with this complication and the availability of effective treatments, continuation of this screening may be prudent.65

The prevalence of Leydig cell dysfunction in childhood cancer survivors has ranged from 2% to 23%,66–69 lower than the prevalence identified in our study (32%). This may reflect the higher proportion of at-risk patients with a history of HCT (52%) in our cohort, a large proportion of whom received testicular irradiation (48%), and the fact that our cohort included only those at risk for the complication because of gonadotoxic therapeutic exposure.

All seven conditions with negligible yield also had a low prevalence (anthracycline-related cardiac conduction disorder, 2.8%; hemorrhagic cystitis, 1.1%; glomerular dysfunction, 0.7% by urinalysis and 0% by serum BUN/creatinine; t-MDS/AML, 0%; bladder cancer, 0%; chronic hepatitis B, 0%; HIV, 0%). Our findings are similar to the extremely low prevalence of t-MDS/AML70 and bladder cancer71 reported by others. Glomerular injury after ifosfamide and platinum-based chemotherapy,72,73 improves over time.74,75 No reports of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis in cohorts of childhood cancer survivors were identified in the literature. Recent studies have found a low prevalence of prolonged QT interval after anthracycline exposure.76 Finally, complete blood counts obtained during the first 10 years after exposure and annual lifelong urinalyses accounted for the vast majority of the screening tests that resulted in negligible/negative yield.

The study needs to be considered within the context of certain limitations. The study population was limited to survivors who participated in the LTFU Clinic. Bias could potentially result from clinical and sociodemographic differences between those who did and did not attend the LTFU Clinic and differences in lifestyle exposures (ie, high-risk health behaviors). However, the yield of complications for a given screening test is driven by therapeutic exposures, thus minimizing the impact of any participation bias. Additionally, the sample was drawn from participants who entered the study at varying lengths of time from cancer diagnoses. Because latency varies by long-term complication, it is possible that not all complications had become detectable at screening, and conversely, it is possible that some complications with shorter latency that were already diagnosed before entry into the LTFU Clinic (deemed pre-existing conditions) would have been detected by screening had the affected participants presented for their initial screening at an earlier time point. Interpretation of our data in the context of both prevalence and screening yield addresses the varying length of follow-up.

In this uniformly screened cohort of childhood cancer survivors using the COG-LTFU Guidelines, we found that screening yield was high for pulmonary dysfunction, hypothyroidism, iron overload, hearing loss, and low BMD. Screening tests with negligible/negative yield included complete blood counts (therapy-related leukemia), dipstick urinalysis for proteinuria and serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine (glomerular defects), microscopic urinalysis for hematuria (hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder cancer), and ECG (anthracycline-related conduction disorder). Elimination of these screening tests should be given consideration. Although the period of elevated risk for acquisition of transfusion-related hepatitis B and HIV infections in the United States ended with initiation of screening of blood products for hepatitis B (1972)77 and HIV (1985),78 the serious implications of undetected occult HIV and hepatitis B virus infection, and the availability of effective therapy for these conditions, suggest that screening may be prudent, despite low yield.79,80

Information related to the yield of the screening tests recommended by the COG-LTFU Guidelines has several practical implications. This information is useful for primary care providers, because they carry an increasing burden of caring for childhood cancer survivors at risk for complex health conditions. The high yield of certain screening tests demonstrates the need for referral to subspecialists for appropriate interventions and hence a need for increased awareness of these complications by the specialists. Finally, the incidence of treatment-related complications will likely increase with time from diagnosis, making it imperative to continue follow-up of our childhood cancer survivors, using standardized recommendations, such as those offered by the COG-LTFU Guidelines. However, given the fact that the recommendations in the COG-LTFU Guidelines are consensus based, this study serves as an example of how application of the COG-LTFU Guidelines in a clinical setting can be used to refine them. The results of this study support the need for additional research to contribute to ongoing refinement of the recommendations for screening frequencies and modalities within the COG-LTFU Guidelines.

Appendix

Rationale for Screening Yield Classification

The rationale for classifying screening yield as negligible/negative (< 1%), intermediate (≥ 1% to < 10%), or high (≥ 10%) was based on an exhaustive review of the literature to determine the prevalence of long-term complications observed in the previous studies performed in childhood cancer survivors. When reviewing this literature, we took into consideration the population under study, the sample size used, the method of assessing long-term complications (ie, self-report v clinical evaluation v medical record review) and the definition used to describe a positive outcome. This review revealed that long-term complications fell into three groups with respect to their prevalence: high, intermediate, and low, as follows:

High prevalence:

hypothyroidism (21% to 57%), pulmonary dysfunction (13% to 87%), hearing loss (25% to 83%), low bone mineral density (21% to 65%), and iron overload (40% to 93%).

Intermediate prevalence:

breast cancer (6% to 12%), hepatotoxicity (8% to 45%), hepatitis C infection (2% to 53%), renal tubular injury (5%), and gonadal dysfunction (2% to 23%).

Low prevalence:

glomerular dysfunction (0.6% to 13%), therapy-related myelodysplasia/acute myeloid leukemia (0.2% to 1.7%), and bladder cancer (0.04%).

In our study, patients entered the City of Hope Long-Term Follow-Up (LTFU) Clinic for Childhood Cancer Survivors at ≥ 2 years after completion of therapy. Because latency varies by type of long-term complication, it is possible that not all complications that would potentially occur in this population had become clinically detectable at the time of screening; conversely, it is possible that some complications with shorter latency were already diagnosed before the entry of the patient into the LTFU Clinic (deemed pre-existing conditions) and would not be included in the yield (thus possibly reducing the yield in the study). On the other hand, screening determinations used in this study were driven by therapeutic exposures identified by the Children's Oncology Group LTFU Guidelines as placing patients at risk for the targeted complications; this targeted approach of screening only those at risk would result in a higher yield than the prevalence reported in the literature (where all patients are usually included, irrespective of their therapeutic exposures). Taking these issues into consideration, as well as the fact that the lowest end of the range of prevalence for the high-prevalence disorders was 13% (pulmonary dysfunction), we conservatively opted to consider all tests with a yield ≥ 10% as belonging to the high-yield category. The low-yield category was defined as those with a negligible yield (< 1%)—with the goal of identifying screening tests that could potentially be eliminated. The intermediate-yield category was reserved for all screening tests with a yield between 1% and 10%.

Table A1.

Cohort Characteristics by Time From Diagnosis to Study Entry

| Characteristic | Years Since Diagnosis |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 to 9 |

10 to 14 |

15 to 19 |

20 to 24 |

25 to 29 |

≥ 30 |

|||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Total patients | 177 | 47.8 | 59 | 15.9 | 48 | 13.0 | 35 | 9.5 | 33 | 8.9 | 18 | 4.9 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Median | 11.1 | 7.8 | 15.7 | 12.3 | 11.3 | 7.4 | ||||||

| Range | 0.3-21.9 | 0.3-21.7 | 0.5-21.8 | 1.4-21.4 | 0.3-21.6 | 1.3-21.8 | ||||||

| Study participation | ||||||||||||

| Median | 17.2 | 21.2 | 32.3 | 32.8 | 38.9 | 43.3 | ||||||

| Range | 5.3-30.7 | 11.6-35.8 | 17.5-39.1 | 22.3-46.3 | 27.6-50.4 | 34.0-57.2 | ||||||

| Male sex | 100 | 56.5 | 31 | 52.5 | 29 | 60.4 | 16 | 45.7 | 11 | 33.3 | 8 | 44.4 |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 15 | 8.5 | 8 | 13.6 | 4 | 8.3 | 3 | 8.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Black | 8 | 4.5 | 1 | 1.7 | 2 | 4.2 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hispanic | 92 | 52.0 | 33 | 55.9 | 23 | 47.9 | 13 | 37.1 | 9 | 27.3 | 4 | 22.2 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 55 | 31.1 | 14 | 23.7 | 18 | 37.5 | 18 | 51.4 | 22 | 66.7 | 14 | 77.8 |

| Other | 7 | 4.0 | 3 | 5.1 | 1 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Leukemia/heme | 81 | 45.8 | 24 | 40.7 | 25 | 52.1 | 15 | 42.9 | 15 | 45.5 | 5 | 27.8 |

| Lymphoma | 37 | 20.9 | 18 | 30.5 | 10 | 20.8 | 13 | 37.1 | 12 | 36.4 | 7 | 38.9 |

| Solid tumors | 59 | 33.3 | 17 | 28.8 | 13 | 27.1 | 7 | 20.0 | 6 | 18.2 | 6 | 33.3 |

| Any chemotherapy | 173 | 97.7 | 56 | 94.9 | 47 | 97.9 | 32 | 91.4 | 29 | 87.9 | 14 | 77.8 |

| Any radiation | 79 | 44.6 | 28 | 47.5 | 27 | 56.3 | 24 | 68.6 | 31 | 93.9 | 17 | 94.4 |

| HCT | 47 | 26.6 | 14 | 23.7 | 15 | 31.3 | 7 | 20.0 | 12 | 36.4 | 1 | 5.6 |

Abbreviation: HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; heme, other hematologic disorders.

Table A2.

Screening Tests Recommended, Completed, and Evaluable

| Test Type | Tests Recommended, No. | Tests Completed |

Tests Evaluable*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Complete blood count | 566 | 563 | 99.5 | 563 | 100.0 |

| Blood urea nitrogen/creatinine | 305 | 301 | 98.7 | 301 | 100.0 |

| Urinalysis for proteinuria | 935 | 933 | 99.8 | 933 | 100.0 |

| Urinalysis for hematuria | 875 | 873 | 99.8 | 845 | 96.8 |

| Liver function tests | 264 | 263 | 99.6 | 263 | 100.0 |

| Potassium, phosphorus, magnesium | 83 | 83 | 100.0 | 83 | 100.0 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (baseline) | 124 | 119 | 96.0 | 119 | 100.0 |

| Audiogram | 71 | 66 | 93.0 | 62 | 93.9 |

| DEXA scan | 196 | 190 | 96.9 | 190 | 100.0 |

| Ferritin | 96 | 96 | 100.0 | 96 | 100.0 |

| Pulmonary function testing | 146 | 145 | 99.3 | 145 | 100.0 |

| Chest x-ray | 150 | 149 | 99.3 | 149 | 100.0 |

| ECG | 253 | 248 | 98.0 | 248 | 100.0 |

| Echocardiogram | 542 | 539 | 99.4 | 533 | 98.9 |

| Hepatitis B screening | 30 | 29 | 96.7 | 29 | 100.0 |

| Hepatitis C screening | 141 | 137 | 97.2 | 137 | 100.0 |

| HIV screening | 78 | 68 | 87.2 | 68 | 100.0 |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone (females) | 73 | 61 | 83.6 | 61 | 100.0 |

| Testosterone (males) | 65 | 61 | 93.8 | 61 | 100.0 |

| Mammogram | 69 | 68 | 98.6 | 68 | 100.0 |

| Total | 5,062 | 4,992 | 98.6 | 4,954 | 99.2 |

Abbreviation: DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Of the tests that were completed.

Table A3.

Screening Yield and Prevalence of Long-Term Complications by At-Risk Cohort

| Screening Test | Targeted LTC | Therapeutic Exposures Driving Screening and Cumulative Exposures for At-Risk Screened Patients |

Patients at Risk,No. | LTC Present Before Screening |

Evaluable Screenings Completed,No. | Screening Yield |

Prevalence of LTC in At-Risk Patients |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Complete blood count | t-MDS/AML | Cyclophosphamide 3,600 mg/m2 | 100-30,400 mg/m2 | 187 | 0 | 0.0 | 563 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Busulfan 436 mg/m2 | 120-480 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Daunorubicin 100 mg/m2 | 56-500 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Etoposide 2,120 mg/m2 | 360-7,920 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Idarubicin 38 mg/m2 | 35-108 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Cisplatin 375 mg/m2 | 90-1,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Ifosfamide 48,300 mg/m2 | 5,000-117,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Doxorubicin 150 mg/m2 | 45-500 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carboplatin 2,400 mg/m2 | 175-6,825 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Melphalan 150 mg/m2 | 140-210 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Teniposide 825 mg/m2 | 660-990 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Temozolomide 5,000 mg/m2 | 5,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Thiotepa 900 mg/m2 | 600-900 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Dacarbazine 4,500 mg/m2 | 1500-5,175 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Procarbazine 4,200 mg/m2 | 1,600-8,400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carmustine 450 mg/m2 | 450 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Lomustine 600 mg/m2 | 225-880 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Mechlorethamine 42.5 mg/m2 | 6-192 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Chorambucil 1,320 mg/m2 | 1,320 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Mitoxantrone 36 mg/m2 | 36 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| HCT (n = 56; autologous, 55.4%; allogeneic, 44.6%) | |||||||||||

| BUN/creatinine | Renal insufficiency | Cisplatin 360 mg/m2 | 90-1,000 mg/m2 | 301 | 0 | 0.0 | 301 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Ifosfamide 49,500 mg/m2 | 5,000-117,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carboplatin 1,702 mg/m2 | 120-6,825 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| High-dose methotrexate 7,970 mg/m2 | 1,000-257,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Low-dose methotrexate 1,270 mg/m2 | 20-13,400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Abdominal radiation 13.2 Gy | 4.5-76 Gy | ||||||||||

| TBI 13.2 Gy | 7.5-13.5 Gy | ||||||||||

| Urinalysis | |||||||||||

| Proteinuria | Renal insufficiency | Cisplatin 360 mg/m2 | 90-1,000 mg/m2 | 303 | 0 | 0.0 | 933 | 2 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.7 |

| Ifosfamide 49,500 mg/m2 | 5,000-117,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carboplatin 1,704 mg/m2 | 120-6,825 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| High-dose methotrexate 7,970 mg/m2 | 1,000-257,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Low-dose methotrexate 1,270 mg/m2 | 20-13,400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Abdominal radiation 13.2 Gy | 4.5-76 Gy | ||||||||||

| TBI 13.2 Gy | 7.5-13.5 Gy | ||||||||||

| Microscopic hematuria | Hemorrhagic cystitis | Cyclophosphamide 3,850 mg/m2 | 100-30,400 mg/m2 | 267 | 3 | 1.1 | 845 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.1 |

| Ifosfamide 49,867 mg/m2 | 5,000-117,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Pelvic radiation 13.2 Gy | 6-119.1 Gy | ||||||||||

| Bladder cancer | Cyclophosphamide 3,850 mg/m2 | 100-30,400 mg/m2 | 267 | 0 | 0.0 | 845 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Ifosfamide 49,867 mg/m2 | 5,000-117,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Pelvic radiation 13.2 Gy | 6-119.1 Gy | ||||||||||

| Liver function tests (ALT, AST, bilirubin) | Hepatic toxicity | High-dose methotrexate 7,970 mg/m2 | 1,000-257,000 mg/m2 | 266 | 3 | 1.1 | 263 | 10 | 3.8 | 13 | 4.9 |

| Low-dose methotrexate 1,295 mg/m2 | 20-13,400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| 6-mercaptopurine 40,300 mg/m2 | 250-92,400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| 6-thioguanine 1,580 mg/m2 | 520-48,730 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| High-dose cytarabine 11,400 mg/m2 | 1,750-53,130 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Low-dose cytarabine 1,200 mg/m2 | 75-18,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Abdominal radiation 38 Gy | 30-76 Gy | ||||||||||

| HCT (n = 93; 44.1% autologous; 55.9% allogeneic; 44.2% with cGVHD) | |||||||||||

| Serum potassium, magnesium, phosphorus | Renal tubular injury | Cisplatin 367.5 mg/m2 | 90-1,000 mg/m2 | 85 | 2 | 2.4 | 83 | 2 | 2.4 | 4 | 4.7 |

| Carboplatin 1,702 mg/m2 | 120-6,825 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Ifosfamide 49,867 mg/m2 | 9,000-117,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| TSH (baseline) | Hypothyroidism | Neck radiation, 24 Gy | 8-81.4 Gy | 169 | 50 | 29.6 | 119 | 12 | 10.1 | 62 | 36.7 |

| TBI, 13.2 Gy | 7.5-13.2 Gy | ||||||||||

| Audiometry | Hearing loss | Cisplatin 300 mg/m2 | 90-1,000 mg/m2 | 71 | 9 | 12.7 | 62 | 14 | 22.6 | 23 | 32.4 |

| Carboplatin (myeloablative dosing) 1,646 mg/m2 | 1,098-2,400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Cranial radiation ≥ 30 Gy: 53.4 Gy | 30-81.4 Gy | ||||||||||

| DEXA scan | Low bone mineral density* | High-dose methotrexate 10,070 mg/m2 | 1,000-257,000 mg/m2 | 211 | 21 | 10.0 | 190 | 44 | 23.2 | 65 | 30.8 |

| Low-dose methotrexate 1,170 mg/m2 | 20-13,400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Prednisone 3,960 mg/m2 | 93-20,644 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Dexamethasone 220 mg/m2 | 10-2,100 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| HCT (n = 70; 41% autologous, 59% allogeneic; 41% of allogeneic with cGVHD) | |||||||||||

| Ferritin | Iron overload | HCT (n = 96; 57% allogeneic, 43% autologous; 44% of allogeneic with cGVHD) | 96 | 0 | 0.0 | 96 | 23 | 24.0 | 23 | 24.0 | |

| Pulmonary function testing | Pulmonary dysfunction (restrictive, obstructive, and/or diffusion defect) | Bleomycin 60 mg/m2 | 16-270 mg/m2 | 158 | 13 | 8.2 | 145 | 122 | 84.1 | 135 | 85.4 |

| Busulfan 436 mg/m2 | 115-1,920 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carmustine 450 mg/m2 | 450-987 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Lomustine 600 mg/m2 | 225-880 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Thorax radiation 37 Gy | 1.2-70 Gy | ||||||||||

| TBI 13.2 Gy | 7.5-13.5 Gy | ||||||||||

| Allogeneic HCT with cGVHD (n = 21); pulmonary surgery (n = 10; lobectomy [n = 3]; metastasectomy [n = 1]; and/or wedge resection [n = 6]) | |||||||||||

| Chest x-ray | Pulmonary fibrosis | Bleomycin 60 mg/m2 | 16-270 mg/m2 | 158 | 9 | 5.7 | 149 | 26 | 17.4 | 35 | 22.2 |

| Busulfan 436 mg/m2 | 115-1,920 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carmustine 450 mg/m2 | 450-987 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Lomustine 600 mg/m2 | 225-880 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Thorax radiation 38 Gy | 1.2-70 Gy | ||||||||||

| TBI 13.2 Gy | 7.5-13.5 Gy | ||||||||||

| Allogeneic HCT with cGVHD (n = 22); pulmonary surgery (n = 11; lobectomy [n = 4], metastasectomy [n = 1], and/or wedge resection [n = 6]) | |||||||||||

| ECG | Cardiac conduction disorder (prolonged QT interval) | Daunorubicin 100 mg/m2 | 25-500 mg/m2 | 253 | 5 | 2.0 | 248 | 2 | 0.08 | 7 | 2.8 |

| Doxorubicin 150 mg/m2 | 25-500 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Epirubicin 300 mg/m2 | 250-600 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Idarubicin 36 mg/m2 | 35-108 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Mitoxantrone 63 mg/m2 | 36-135 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Echocardiogram | Cardiac left ventricular systolic dysfunction | Daunorubicin 100 mg/m2 | 25-500 mg/m2 | 260 | 8 | 3.1 | 533 | 32 | 6.0 | 39 | 15.0 |

| Doxorubicin 150 mg/m2 | 25-500 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Epirubicin 300 mg/m2 | 250-600 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Idarubicin 36 mg/m2 | 35-108 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Mitoxantrone 63 mg/m2 | 36-135 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody | Chronic hepatitis B infection | Cancer diagnosis before 1972 or diagnosed outside United States | 29 | 0 | 0.0 | 29 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hepatitis C antibody and PCR | Chronic hepatitis C infection | Cancer diagnosis before 1993 or diagnosed outside United States | 146 | 9 | 6.2 | 137 | 4 | 2.9 | 13 | 8.9 | |

| HIV serology (HIV 1 and 2 antibodies) | HIV infection | Cancer diagnosis between 1977 and 1985 or diagnosed outside United States | 68 | 0 | 0.0 | 68 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone | Gonadal dysfunction (female): premature menopause | Cyclophosphamide 4,000 mg/m2 | 600-27,000 mg/m2 | 77 | 16 | 20.8 | 61 | 4 | 6.6 | 20 | 26.0 |

| Cisplatin 350 mg/m2 | 100-600 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Ifosfamide 63,000 mg/m2 | 45,000-117,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carboplatin 2,860 mg/m2 | 120-5,600 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Dacarbazine 4,219 mg/m2 | 937-7,500 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Procarbazine 3,600 mg/m2 | 600-4,900 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carmustine 450 mg/m2 | 450 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Lomustine 600 mg/m2 | 225-600 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Mechlorethamine 34 mg/m2 | 6-36 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Pelvic radiation 25.5 Gy | 7.5-119.1 Gy | ||||||||||

| Cranial radiation ≥ 40 Gy: 54 Gy | 45-59.4 Gy | ||||||||||

| Serum testosterone | Gonadal dysfunction (male): Leydig cell dysfunction | Cyclophosphamide 4,600 mg/m2 | 195-29,900 mg/m2 | 82 | 21 | 25.6 | 61 | 5 | 8.2 | 26 | 31.7 |

| Busulfan 120 mg/m2 | 120 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Cisplatin 450 mg/m2 | 180-1,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Ifosfamide 24,000 mg/m2 | 9,000-115,200 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carboplatin 3,840 mg/m2 | 1,600-6,080 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Temozolomide 5,000 mg/m2 | 5,000 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Thiotepa 900 mg/m2 | 900 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Dacarbazine 1,875 mg/m2 | 1,500-2,250 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Procarbazine 3,500 mg/m2 | 1,600-8,400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Carmustine 987 mg/m2 | 987 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Lomustine 880 mg/m2 | 880 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Mechlorethamine 36 mg/m2 | 36 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Pelvic radiation ≥ 20 Gy: 62 Gy | 21-70 Gy | ||||||||||

| Cranial radiation ≥ 40 Gy: 47.4 Gy | 45-79.4 Gy | ||||||||||

| Mammogram | Breast cancer | Chest/thorax radiation ≥ 20 Gy: 40 Gy | 20-50.5 Gy | 30 | 5 | 16.7 | 68 | 2 | 2.9 | 7 | 23.3 |

Abbreviations: BUN, blood urea nitrogen; cGVHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; LTC, long-term complication; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TBI, total body irradiation; t-MDS/AML, therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Includes only patients age ≥ 18 years with the therapeutic exposures listed.

Table A4.

Cohort Characteristics by Screening Test and Summary of Screening Test Results

| Targeted Long-Term Complication | Associated Screening Tests | Cohort Characteristics by Screening Test | Summary of Screening Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-MDS/AML | CBC | n = 187; 59% male; 54% Hispanic; median age at testing, 18.3 years (range, 5-54 years); median age at diagnosis, 11.3 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 6.2 years (range, 5-35.8 years) | Median WBC, 6,500/μL (range, 2300-14,300/μL); hemoglobin (male), 14.3 gm/dL (range, 10.1-17.7 gm/dL); hemoglobin (female), 12.9 gm/dL (range, 9.1-15.6 gm/dL); platelets, 256,000/μL (range, 60,000-588,000/μL; 41 patients (7.3%) were identified by screening as having abnormal CBC; 29 had abnormal WBC (< 4,000/μL); two had abnormal hemoglobin (< 10 gm/dL); 20 had abnormal platelet count (< 150,000/μL); some patients had more than one abnormality; no patient had blasts present on WBC differential or pathology report confirming diagnosis of t-MDS/AML |

| Renal insufficiency | BUN/creatinine | n = 301; 54% male; 51% Hispanic; median age at testing, 23 years (range, 5-57 years); median age at diagnosis, 11.1 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 10 years (range, 5-55.8 years) | Median cohort GFR, 137.94 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (range, 67.79-483.21 mL/min per 1.73 m2) overall; 138.57 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (range, 71.75-483.21 mL/min per 1.73 m2) according to Schwartz formula (age ≤ 18 years); 137.59 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (range, 67.79-389.94 mL/min per 1.73 m2) according to Cockroft-Gault formula (age >18 years); no patients in cohort identified by screening as having a GFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 |

| Urinalysis (proteinuria) | n = 303; 54% male; 50% Hispanic; median age at testing, 23 years (range, 5-57 years); median age at diagnosis, 11.3 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 10 years (range, 5-55.8 years) | Two of 303 patients in cohort tested positive for proteinuria ≥ 2+ on one screening test each; both were subsequently diagnosed clinically with renal insufficiency | |

| Hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder cancer | Urinalysis (microscopic hematuria) | n = 267; 57% male; 48% Hispanic; median age at testing, 22.1 years (range, 5.3-57.2 years); median age at diagnosis, 11.3 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 9.5 years (range, 5-55.8 years) | 31 urinalyses in 12 patients were abnormal by screening (> 5 RBC/HPF) and required further workup; none of these patients were subsequently diagnosed with hemorrhagic cystitis or bladder cancer |

| Hepatic toxicity | Liver function tests (ALT, AST, bilirubin) | n = 263; 55% male; 44% Hispanic; median age at testing, 28.3 years (range, 8-58 years); median age at diagnosis, 10.2 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 10.4 years (range, 5-37.8 years) | Median AST for cohort, 31 U/L (range, 15-246 U/L); median ALT, 22 U/L (range, 2.9-220 U/L); median total bilirubin, 0.4 mg/dL (range, 0.1-2.1 mg/dL); total of 10 patients in cohort had at least one abnormal liver function test: one had AST ≥ 2× ULN; one had ALT ≥ 2× ULN; five had both ALT and AST ≥ 2× ULN; three patients had bilirubin > 1.5 mg/dL; seven of 10 were diagnosed with abnormality involving liver (including alcohol and drug abuse, elevated ferritin, GVHD involving liver, hepatitis C, transaminitis); two with abnormal bilirubin were not identified with hepatic abnormalities on further workup (conjugated bilirubin 0.0 mg/dL in both); one with abnormal bilirubin did not undergo further workup |

| Renal tubular injury | Serum potassium, magnesium, phosphorus | n = 83; 55% male; 53% Hispanic; median age at testing, 22 years (range, 5-45 years); median age at diagnosis, 14.5 years (range, 0.3-21.7 years); median time since diagnosis, 7.9 years (range, 5-27.9 years) | Patients considered to have developed renal tubular injury if they had ≥ two of following abnormalities on screening: serum potassium < 3.5 mmol/L, serum magnesium < 1.6 mg/dL, and/or serum phosphorus < 2.6 mg/dL; two patients were determined to have renal tubular injury by screening: one had abnormal potassium, magnesium, and phosphorus; one had abnormal magnesium and potassium and normal phosphorus |

| Hypothyroidism | TSH | n = 119; 50% male; 42% Hispanic; median age at testing, 27 years (range, 7-54 years); median age at diagnosis, 14.7 years (range, 0.5-21.8 years); median time since diagnosis, 12.4 years (range, 5-37.8 years) | Median baseline TSH in cohort, 2.07 mIU/L (range, 0.61 to 32 mIU/L); 12 patients were identified to have abnormal TSH on baseline screening (TSH > 4.5 mIU/L); median TSH for these patients, 6.47 mIU/L (range, 4.74-32 mIU/L) |

| Cardiac conduction disorder (prolonged QT interval) | ECG | n = 248; 53.2% male; 46.8% Hispanic; median age at testing, 21 years (range, 5-53 years); median age at diagnosis, 11.4 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 9.0 years (range, 5-35.8 years) | Median QTc interval in cohort, 392 msec (range, 270-530 msec); males: median, 390 msec (range, 270-530 msec); females: median, 400 msec (range, 270-490 msec); two patients (0.08%) were identified with prolonged QTc interval by screening, defined as: males, > 450 msec; females, > 470 msec |

| Cardiac left ventricular systolic dysfunction | Echocardiogram | n = 252; 52.8% male; 46.8% Hispanic; median age at testing, 21 years (range, 5-53 years); median age at diagnosis, 11.3 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 9.0 years (range, 5-36.5 years) | Median ejection fraction in cohort, 62% (range, 35%–80%); median fractional shortening in cohort, 33.9% (range, 20%–53.2%); 32 patients (6.0%) were identified with left ventricular systolic dysfunction by screening, defined as ejection fraction < 55% or fractional shortening < 28% |

| Hearing loss | Audiometry | n = 62; 56% male; 53% Hispanic; median age at testing, 26 years (range, 5-52 years); median age at diagnosis, 14.9 years (range, 0.3-21.8 years); median time since diagnosis, 9.0 years (range, 5-32.5 years) | 14 patients (22.6%) had hearing loss in better ear on screening according to Chang scale, as follows: grade 1A, 3; 1B, 3; 2A, 4; 2B, 3; 3, 1 |

| Low bone mineral density | DEXA scan | n = 190; 54% male; 43% Hispanic; median age at testing, 27 years (range, 18-50 years); median age at diagnosis, 13.8 years (range, 1.0-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 14.0 years (range, 5-37.8 years); 70 (36.8%) received HCT; of these, 29 (41.4%) were autologous and 41 (58.6%) were allogeneic; 17 of allogeneic HCT recipients (41.5%) had cGVHD | 44 patients (23.2%) screened had low bone mineral density, defined as Z score > −1 SD below mean (age < 20 years) or T score > −2 SD below mean (age ≥ 20 years); median T scores were: spine, 0 (range, −3.1 to 3.8); left hip, 0 (range, −3.1 to 2.5); right hip, 0 (range, −3.2 to 3.2); median Z scores were: spine, −0.1 (range, −2.9 to 3.7); left hip, 0 (range, −2.5 to 2.6); right hip, 0 (range, −3.6 to 3.0); screening limited to patients age ≥ 18 years (65 patients with relevant exposures but currently age < 18 years not screened) |

| Iron overload | Ferritin | n = 96; 59% male; 50% Hispanic; median age at testing, 27 years (range, 5-45 years); median age at diagnosis, 17.1 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 10.3 years (range, 5-30.3 years); 96 patients (100%) underwent HCT; 55 (57.3%) were allogeneic and 41 (42.7%) autologous; 24 of allogeneic HCT recipients (43.6%) had cGVHD | Ferritin abnormally elevated (> 500 ng/mL) in 23 of patients screened (24.0%) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | Chest x-ray | n = 149; 52% male; 44% Hispanic; median age at testing, 27 years (range, 9-54 years); median age at diagnosis, 17 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 12.6 years (range, 5-36.5 years) | 26 patients (17.4%) had pulmonary fibrosis by chest x-ray, defined as report by radiologist indicating scarring or fibrosis of lungs and/or pleura |

| Pulmonary dysfunction (restrictive, obstructive, and/or diffusion defect) | Pulmonary function testing | n = 145; 51% male; 45% Hispanic; median age at testing, 27 years (range, 9-54 years); median age at diagnosis, 17 years (range, 0.3-21.9 years); median time since diagnosis, 12.6 years (range, 5-36.5 years) | Total of 122 (84.1%) of 145 patients screened had at least one abnormality on PFT: 65 (44.8%) had obstructive defect (FEV1 < 80% predicted); 70 (48.3%) had restrictive defect (TLC < 80% predicted ); 98 (67.6%) had diffusion defect (DLCO < 80% predicted); 37 (25.5%) had all three defects; only 23 (15.9%) had normal PFT |

| Chronic hepatitis B infection | Hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody | n = 29; 52% male; 66% Hispanic; 89.7% diagnosed outside United States; median age at testing, 27 years (range, 5-57 years); median age at diagnosis, 11.5 years (range, 0.3-19.7 years); median time since diagnosis, 15.8 years (range 5.2-55.8 years) | No positive screening tests for hepatitis B in cohort |

| Chronic hepatitis C infection | Hepatitis C antibody | n = 137; 48% male; 40% Hispanic; 7.3% diagnosed outside United States; median age at testing, 32 years (range, 6-57 years); median age at diagnosis, 10.5 years (range, 0.3-21.8 years); median time since diagnosis, 20.6 years (range, 5.2-55.8 years) | Four (2.9%) of 137 at-risk patients screened positive for hepatitis C infection in cohort |

| HIV infection | HIV serology (HIV 1 and 2 antibodies) | n = 68; 44% male; 38.2% Hispanic; 17.7% diagnosed outside United States; median age at testing, 34 years (range, 6-50 years); median age at diagnosis, 10.9 years (range, 0.3-21.4 years) median time since diagnosis, 24.3 years (range, 5.2-30.4 years) | No positive screening tests for HIV in cohort |

| Gonadal dysfunction (female): premature menopause | FSH | n = 61; 100% female; 39.4% Hispanic; median age at testing, 21 years (range, 12-39 years); median age at diagnosis, 9.2 years (range, 0.5-20.5 years); median time since diagnosis, 12.6 years (range, 5-33.7 years) | Four (6.6%) of 61 patients had abnormal FSH detected by screening in cohort |

| Gonadal dysfunction (male): Leydig cell dysfunction | Serum testosterone | n = 61; 100% male; 48% Hispanic; median age at testing, 21 years (range, 14-40 years); median age at diagnosis, 12.8 years (range, 2.1-21.3 years); median time since diagnosis, 8.9 years (range, 5-33.8 years) | Five (8.2%) of 61 patients had abnormal testosterone detected by screening in cohort |

| Breast cancer | Mammogram | n = 25; 100% female; 32% Hispanic; median age at testing, 34 years (range, 25-50 years); median age at diagnosis, 17.3 years (range, 1.3-21.4 years); median time since diagnosis, 19.3 years (range, 5-33.7 years); total of 68 screenings completed over one to five visits: 25 completed baseline screening; 21 at second visit; 13 at third visit; six at fourth visit; three at fifth visit | Two (8.0%) of 25 patients had breast cancer detected as result of screening in cohort; one case detected at second screening, one at fifth screening; screening yield positive in two (2.9%) of 68 screening tests |

Abbreviations: BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; cGVHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; DLCO, diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; HPF, high-power field; PFT, pulmonary function test; QTc, corrected QT interval; SD, standard deviation; TLC, total lung capacity; t-MDS/AML, therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Fig A1.

Cohort characteristics by time since diagnosis to study entry (in 5-year increments).

Footnotes

Listen to the podcast by Dr Oeffinger at www.jco.org/podcasts

Supported in part by Grant No. P30 CA033572 from the National Institutes of Health; and by the Lincy, Bandai, Hearst, Graham Family, Rite Aid, Altschul, and Newman's Own Foundations; and by the Sam Bottleman Estate.

Presented in part at the European Symposium on Late Complications After Childhood Cancer, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, September 29-30, 2011.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Wendy Landier, Saro H. Armenian, Smita Bhatia

Financial support: Smita Bhatia

Administrative support: Smita Bhatia

Provision of study materials or patients: Smita Bhatia

Collection and assembly of data: Wendy Landier, Jin Lee, Ola Thomas, Liton Francisco, Claudia Herrera, Clare Kasper, Karla D. Wilson, Meghan Zomorodi, Smita Bhatia

Data analysis and interpretation: Wendy Landier, Saro H. Armenian, Jin Lee, Ola Thomas, F. Lennie Wong, Smita Bhatia

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armenian SH, Meadows AT, Bhatia S. Late effects of childhood cancer and its treatment. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. ed 6. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Raven; 2010. pp. 1431–1462. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landier W, Bhatia S. Cancer survivorship: A pediatric perspective. Oncologist. 2008;13:1181–1192. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2007;297:2705–2715. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diller L, Chow EJ, Gurney JG, et al. Chronic disease in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort: A review of published findings. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2339–2355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Screening. In: Mayrent SL, editor. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company; 1987. pp. 327–347. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewitt M, Weiner SL, Simone JV. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. Childhood Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: The Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children's Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4979–4990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz GJ, Furth SL. Glomerular filtration rate measurement and estimation in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:1839–1848. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierrat A, Gravier E, Saunders C, et al. Predicting GFR in children and adults: A comparison of the Cockcroft-Gault, Schwartz, and modification of diet in renal disease formulas. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1425–1436. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beetham R, Cattell WR. Proteinuria: Pathophysiology, significance and recommendations for measurement in clinical practice. Ann Clin Biochem. 1993;30:425–434. doi: 10.1177/000456329303000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kersun LS, Wimmer RS, Hoot AC, et al. Secondary malignant neoplasms of the bladder after cyclophosphamide treatment for childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42:289–291. doi: 10.1002/pbc.10451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIntosh S, Davidson DL, O'Brien RT, et al. Methotrexate hepatotoxicity in children with leukemia. J Pediatr. 1977;90:1019–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(77)80587-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bianchetti MG, Kanaka C, Ridolfi-Lüthy A, et al. Persisting renotubular sequelae after cisplatin in children and adolescents. Am J Nephrol. 1991;11:127–130. doi: 10.1159/000168288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aoki Y, Belin RM, Clickner R, et al. Serum TSH and total T4 in the United States population and their association with participant characteristics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999-2002) Thyroid. 2007;17:1211–1223. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang KW, Chinosornvatana N. Practical grading system for evaluating cisplatin ototoxicity in children. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1788–1795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.4228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreisman H, Wolkove N. Pulmonary toxicity of antineoplastic therapy. Semin Oncol. 1992;19:508–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaste SC. Bone-mineral density deficits from childhood cancer and its therapy: A review of at-risk patient cohorts and available imaging methods. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:373–378. doi: 10.1007/s00247-003-1132-1. quiz 443-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knovich MA, Storey JA, Coffman LG, et al. Ferritin for the clinician. Blood Rev. 2009;23:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bath LE, Wallace WH, Critchley HO. Late effects of the treatment of childhood cancer on the female reproductive system and the potential for fertility preservation. BJOG. 2002;109:107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.t01-1-01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sklar C. Reproductive physiology and treatment-related loss of sex hormone production. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:2–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199907)33:1<2::aid-mpo2>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75–89. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motosue MS, Zhu L, Srivastava K, et al. Pulmonary function after whole lung irradiation in pediatric patients with solid malignancies. Cancer. 2012;118:1450–1456. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inaba H, Yang J, Pan J, et al. Pulmonary dysfunction in survivors of childhood hematologic malignancies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2010;116:2020–2030. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasilewski-Masker K, Mertens AC, Patterson B, et al. Severity of health conditions identified in a pediatric cancer survivor program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:976–982. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulder RL, Thönissen NM, van der Pal HJ, et al. Pulmonary function impairment measured by pulmonary function tests in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Thorax. 2011;66:1065–1071. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiner DJ, Maity A, Carlson CA, et al. Pulmonary function abnormalities in children treated with whole lung irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:222–227. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan E, Sklar C, Wilmott R, et al. Pulmonary function in children treated for rhabdomyosarcoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27:79–84. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199608)27:2<79::AID-MPO3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chotsampancharoen T, Gan K, Kasow KA, et al. Iron overload in survivors of childhood leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:348–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kornreich L, Horev G, Yaniv I, et al. Iron overload following bone marrow transplantation in children: MR findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:869–872. doi: 10.1007/s002470050259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKay PJ, Murphy JA, Cameron S, et al. Iron overload and liver dysfunction after allogeneic or autologous bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaste SC, Shidler TJ, Tong X, et al. Bone mineral density and osteonecrosis in survivors of childhood allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:435–441. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaste SC, Ahn H, Liu T, et al. Bone mineral density deficits in pediatric patients treated for sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1032–1038. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holzer G, Krepler P, Koschat MA, et al. Bone mineral density in long-term survivors of highly malignant osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:231–237. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b2.13257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis MJ, DuBois SG, Fligor B, et al. Ototoxicity in children treated for osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:387–391. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schell MJ, McHaney VA, Green AA, et al. Hearing loss in children and young adults receiving cisplatin with or without prior cranial irradiation. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:754–760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macdonald MR, Harrison RV, Wake M, et al. Ototoxicity of carboplatin: Comparing animal and clinical models at the Hospital for Sick Children. J Otolaryngol. 1994;23:151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Womer RB, Silber JH. Predicting cisplatin ototoxicity in children: The influence of age and the cumulative dose. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2445–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kushner BH, Budnick A, Kramer K, et al. Ototoxicity from high-dose use of platinum compounds in patients with neuroblastoma. Cancer. 2006;107:417–422. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhatia S, Ramsay NK, Bantle JP, et al. Thyroid abnormalities after therapy for Hodgkin's disease in childhood. Oncologist. 1996;1:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker KS, Ness KK, Weisdorf D, et al. Late effects in survivors of acute leukemia treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation: A report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Leukemia. 2010;24:2039–2047. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonato C, Severino RF, Elnecave RH. Reduced thyroid volume and hypothyroidism in survivors of childhood cancer treated with radiotherapy. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2008;21:943–949. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2008.21.10.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steffens M, Beauloye V, Brichard B, et al. Endocrine and metabolic disorders in young adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:819–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailey HK, Kappy MS, Giller RH, et al. Time-course and risk factors of hypothyroidism following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in children conditioned with fractionated total body irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:405–409. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyoshi Y, Ohta H, Hashii Y, et al. Endocrinological analysis of 122 Japanese childhood cancer survivors in a single hospital. Endocr J. 2008;55:1055–1063. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nandagopal R, Laverdière C, Mulrooney D, et al. Endocrine late effects of childhood cancer therapy: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Horm Res. 2008;69:65–74. doi: 10.1159/000111809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grewal S, Merchant T, Reymond R, et al. Auditory late effects of childhood cancer therapy: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e938–e950. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wasilewski-Masker K, Kaste SC, Hudson MM, et al. Bone mineral density deficits in survivors of childhood cancer: Long-term follow-up guidelines and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e705–e713. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liles A, Blatt J, Morris D, et al. Monitoring pulmonary complications in long-term childhood cancer survivors: Guidelines for the primary care physician. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:531–539. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.7.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang TT, Hudson MM, Stokes DC, et al. Pulmonary outcomes in survivors of childhood cancer: A systematic review. Chest. 2011;140:881–901. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tillmann V, Darlington AS, Eiser C, et al. Male sex and low physical activity are associated with reduced spine bone mineral density in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1073–1080. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.6.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arikoski P, Komulainen J, Voutilainen R, et al. Reduced bone mineral density in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;20:234–240. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199805000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaste SC, Jones-Wallace D, Rose SR, et al. Bone mineral decrements in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Frequency of occurrence and risk factors for their development. Leukemia. 2001;15:728–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Müller HL, Schneider P, Bueb K, et al. Volumetric bone mineral density in patients with childhood craniopharyngioma. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2003;111:168–173. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benmiloud S, Steffens M, Beauloye V, et al. Long-term effects on bone mineral density of different therapeutic schemes for acute lymphoblastic leukemia or non-Hodgkin lymphoma during childhood. Horm Res Paediatr. 2010;74:241–250. doi: 10.1159/000313397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention Diagnosis and Therapy: Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–795. [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Bruin ML, Sparidans J, van't Veer MB, et al. Breast cancer risk in female survivors of Hodgkin's lymphoma: Lower risk after smaller radiation volumes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4239–4246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Floyd J, Mirza I, Sachs B, et al. Hepatotoxicity of chemotherapy. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:50–67. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castellino S, Muir A, Shah A, et al. Hepato-biliary late effects in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:663–669. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Locasciulli A, Testa M, Pontisso P, et al. Prevalence and natural history of hepatitis C infection in patients cured of childhood leukemia. Blood. 1997;90:4628–4633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aricò M, Maggiore G, Silini E, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1994;84:2919–2922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cesaro S, Petris MG, Rossetti F, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection after treatment for pediatric malignancy. Blood. 1997;90:1315–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Castellino S, Lensing S, Riely C, et al. The epidemiology of chronic hepatitis C infection in survivors of childhood cancer: An update of the St Jude Children's Research Hospital hepatitis C seropositive cohort. Blood. 2004;103:2460–2466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, et al. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:271–278. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerl A, Mühlbayer D, Hansmann G, et al. The impact of chemotherapy on Leydig cell function in long term survivors of germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2001;91:1297–1303. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010401)91:7<1297::aid-cncr1132>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greenfield DM, Walters SJ, Coleman RE, et al. Prevalence and consequences of androgen deficiency in young male cancer survivors in a controlled cross-sectional study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3476–3482. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romerius P, Ståhl O, Moëll C, et al. Hypogonadism risk in men treated for childhood cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4180–4186. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ridola V, Fawaz O, Aubier F, et al. Testicular function of survivors of childhood cancer: A comparative study between ifosfamide- and cyclophosphamide-based regimens. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:814–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhatia S, Yasui Y, Robison LL, et al. High risk of subsequent neoplasms continues with extended follow-up of childhood Hodgkin's disease: Report from the Late Effects Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4386–4394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bassal M, Mertens AC, Taylor L, et al. Risk of selected subsequent carcinomas in survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:476–483. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jones DP, Chesney RW. Renal toxicity of cancer chemotherapeutic agents in children: Ifosfamide and cisplatin. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1995;7:208–213. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199504000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Skinner R, Pearson AD, English MW, et al. Cisplatin dose rate as a risk factor for nephrotoxicity in children. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1677–1682. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]