Abstract

The thin filament protein troponin T (TnT) is a regulator of sarcomere function. Whole heart energetics and contractile reserve are compromised in transgenic mice bearing missense mutations at R92 within the tropomyosin-binding domain of cTnT, despite being distal to the ATP hydrolysis domain of myosin. These mutations are associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (FHC). Here we test the hypothesis that genetically replacing murine αα-MyHC with murine ββ-MyHC in hearts bearing the R92Q cTnT mutation, a particularly lethal FHC-associated mutation, leads to sufficiently large perturbations in sarcomere function to rescue whole heart energetics and decrease the cost of contraction. By comparing R92Q cTnT and R92L cTnT mutant hearts, we also test whether any rescue is mutation-specific. We defined the energetic state of the isolated perfused heart using 31P-NMR spectroscopy while simultaneously measuring contractile performance at four work states. We found that the cost of increasing contraction in intact mouse hearts with R92Q cTnT depends on the type of myosin present in the thick filament. We also found that the salutary effect of this manoeuvre is mutation-specific, demonstrating the major regulatory role of cTnT on sarcomere function at the whole heart level.

Key points

Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (FHC)-associated missense mutations in the tail portion of cardiac troponin T (cTnT) lead to a phenotype characterized by an increased cost of cardiac contraction, contractile dysfunction and impaired energetics.

Arginine 92 (R92) in cTnT is a ‘hotspot’ with many FHC-associated missense mutations; each mutation leads to a clinically distinct cardiomyopathy. Both R92Q and R92L cTnT mutant mouse hearts exhibit the FHC phenotype.

Here we found that genetically remodelling the sarcomere by substituting αα-myosin heavy chain (αα-MyHC) with ββ-MyHC normalizes the increased cost of cardiac contraction, rescuing both contractile dysfunction and energetic abnormalities, in R92Q cTnT mutant hearts, while wild-type R92 and R92L cTnT mutant hearts were unaffected.

Our results demonstrate that the conformation of the tropomyosin-binding domain of cTnT induced by each unique amino acid substitution at R92 is a major determinant of sarcomere function.

Introduction

Muscle contraction occurs when the thick filament protein myosin interacts with specific domains of the thin filament protein actin, coupling the energy released from ATP hydrolysis (ΔG∼ATP) by myosin to force generation. Availability of the myosin-binding domains of actin for cross-bridge formation depends on the conformation of the thin filament regulatory proteins tropomyosin (TM) and troponin (Tn). Each of the subunits of troponin, TnT, TnC and TnI, plays a regulatory role in cross-bridge dynamics. Cross-bridge cycling depends on both Ca2+-dependent activation of TnC and Ca2+-independent conformational changes in TnT and TnI. The tail portion of TnT binds to TM where the two TM polypeptide chains overlap, changing the flexibility of the thin filament. This determines the affinity of the TnT–TM complex for actin, which in turn determines the availability of myosin-binding domains on actin for cross-bridge formation. Experiments using model systems have shown that changing the TnT–TM interaction by deleting the TnT tail domain alters actomyosin ATPase activity, in vitro motility of actin-TM filaments on myosin heads and cooperativity of myosin subfragment-1 binding to thin filaments (Maytum et al. 2002; Tobacman et al. 2002). Thus, in addition to playing the classical structural role in the thin filament, TnT also plays a crucial dynamic role in the regulation of the contractile cycle and ATP utilization by the sarcomere.

Missense mutations in the tail portion of cardiac TnT (cTnT) discovered by association with the cardiac disease familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (FHC) have been shown to lead to cardiac phenotypes characterized by contractile dysfunction with modest or no left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy but early sudden death (reviewed in Tardiff, 2011). Arginine 92 (R92) in cTnT is a ‘hotspot’ with many FHC-associated missense mutations; each mutation leads to a clinically distinct cardiomyopathy with a unique progression of disease, making treatment challenging. R92 is located in the elongated tail domain of cTnT adjacent to the critical site of overlap of TM monomers. Using molecular dynamics simulations, our group has found that substituting the FHC-associated amino acids tryptophan (W), leucine (L) or glutamine (Q) for R at residue 92 of cTnT alters the flexibility and dynamics of the cTnT domain that binds to TM (Guinto et al. 2007). Moreover, each mutation yields a unique average conformation. A recent molecular dynamics analysis of the thin filament protein complex shows how seemingly small changes in the conformation of one component, in this case TnC, propagates throughout the entire thin filament (Manning et al. 2011). The conformational changes induced by FHC-associated amino acid substitutions at R92 in cTnT produce distinct phenotypes. Murine hearts genetically manipulated to replace R92 cTnT with R92Q, R92W or R92L demonstrate contractile dysfunction, and the changes for R92Q and R92W hearts are more severe than for R92L hearts (Ertz-Berger et al. 2005; He et al. 2007; Guinto et al. 2009; Rice et al. 2010). Thus each mutation produces a unique peptide conformation and dynamics sufficient to alter thin filament flexibility and cross-bridge dynamics, which lead to mutation-specific phenotypes in murine cardiac fibres, cardiomyocytes and intact hearts.

Using these well-characterized transgenic mouse hearts, we have also found that these R92 cTnT mutations lead to an increased cost of contraction assessed as decreased free energy available from ATP hydrolysis, |ΔG∼ATP|, and diminished ability of the heart to increase contractile performance (Javadpour et al. 2003; He et al. 2007). This is the case despite the fact that R92 cTnT is physically distant from the ATP hydrolysis pocket in myosin. Importantly, we have also found that the increase in the cost of contraction is mutation-specific (He et al. 2007). Increases in the cost of contraction have also been observed in mouse hearts bearing the FHC-associated R403Q mutation in the actin-binding loop of myosin (Spindler et al. 1998), suggesting that a common consequence of the different malignant FHC-associated mutations in sarcomeric proteins is an increased cost of cardiac contraction. These findings would explain clinical observations that the phosphocreatine (PCr) to ATP ratio is lower in hearts of FHC patients with diverse sarcomeric mutations (Watkins et al. 1995a,b) and thereby provide a structural-energetic basis for their cardiac dysfunction. These observations also suggest that strategies designed to increase the efficiency of contraction would increase contractile performance of those hearts bearing FHC-associated mutations that affect the interaction of the actin-binding loop of myosin in the thick filament and actin in the thin filament.

We recently tested the novel hypothesis that genetically remodelling the sarcomere by substituting the endogeneous murine myosin heavy chain, αα-MyHC, with ββ-MyHC in mouse hearts bearing the FHC-associated mutations at R92 in cTnT would rescue abnormalities observed during baseline contractile performance (Rice et al. 2010). The rationale for this experiment was that, despite the fact that the myosin isozymes are highly homologous (93% amino acid identity; McNally et al. 1989), their physiological and biochemical properties differ markedly. In in vitro motility studies, for example, αα-MyHC has twice the actin-activated and Ca2+-stimulated ATPase activity and three times the actin filament sliding velocity whereas it produces only half of the average cross-bridge force as ββ-MyHC (Alpert et al. 2002). The actin- and Ca2+-activated ATPase activities of the different myosin isozymes determine the velocity of sarcomere contraction (Barany, 1967). Furthermore, recent thermodynamic analyses of the dynamics of the nucleotide-binding pocket of myosin provide a mechanistic basis explaining why slow myosins are more efficient at force generation (Purcell et al. 2011). Our experiments using R92Q cTnT mutant mouse hearts showed that genetically replacing αα-MyHC (95%αα–5%ββ) with ββ-MyHC (80%ββ–20%αα) rescued baseline systolic but not diastolic dysfunction (Rice et al. 2010). Neither wild-type R92 cTnT nor R92L cTnT mutant hearts, which demonstrated less contractile dysfunction, were affected.

Using R92Q and R92L cTnT mouse hearts, here we test whether increasing the efficiency of the sarcomere by substituting the slow murine ββ-MyHC for the fast murine αα-MyHC would rescue the dysfunctional R92Q and R92L cTnT energetic phenotypes and thereby alter the cost of increasing contraction. We chose these two mutations because they represent widely differing clinical phenotypes that are reproduced in transgenic mouse hearts. While both R92Q and R92L cTnT mouse hearts have impaired energetics, demonstrate diastolic contractile dysfunction even at low work states and have severely impaired contractile reserve, R92Q cTnT hearts also have impaired systolic contractile function even at low work states (Javadpour et al. 2000; He et al. 2007; Rice et al. 2010). Rescuing the R92Q cTnT mutant heart and improving contractile and energetic reserve would therefore pose the greater challenge. We chose to test this hypothesis under conditions that we have previously demonstrated come the closest to normalizing the cost of increasing contraction in R92 cTnT mutant mouse hearts, namely perfusion with the inotrope dobutamine (He et al. 2007). Imposing a high work state with this inotrope for αR92L hearts improved contractile performance and normalized the cost of increasing contraction compared to other methods of increasing work but did not rescue its abnormal energetic phenotype. Studying R92L cTnT hearts therefore tests whether remodelling the thick filament would rescue the energetic dysfunction caused by this mutant thin filament. We defined the energetic state of the isolated perfused mouse hearts using 31P-NMR spectroscopy while simultaneously measuring contractile performance at four work states. We found that the cost of increasing contraction in intact beating mouse hearts bearing the FHC-associated mutation R92Q cTnT depends on the type of myosin present in the thick filament, and that the salutary effect of this manoeuvre is mutation-specific. These results demonstrate the crucial role the conformation of the thin filament protein Troponin T plays in the regulation of cardiac contraction.

Methods

Ethical approval, generation and characteristics of the transgenic mice

C57BL/6 mice, 19–23 weeks old, bearing c-myc tagged murine cTnT with R92Q and R92L mutations were generated as described (all animals at F4 or above) (Tardiff et al. 1999; Ertz-Berger et al. 2005). The R92Q and R92L lines express 67% and 60% of total cTnT as the mutant form, respectively, and were driven by −2996 bp of a 5′ upstream sequence derived from the rat α-MyHC promoter. β-MyHC expression was increased in the cardiac ventricles of these animals genetically by crossing them with a transgenic line expressing 80%ββ-MyHC in the LV (Krenz et al. 2003). This line expressed the full-length β-MyHC mouse cDNA driven by the mouse α-MyHC promoter. All relevant genotypes were produced and were viable: wild-type cTnT/wild-type α-MyHC (αR92, n = 29), wild-type cTnT/β-MyHC (βR92, n = 26), R92 mutations/α-MyHC (αR92Q, n = 16 and αR92L, n = 11) and R92 mutations/β-MyHC (βR92Q, n = 16 and βR92L, n = 11). Cardiomyocytes rigidly control the stoichiometry of the contractile proteins within the sarcomere, and the total amounts of myosin and cTnT in the six types of hearts were the same (Rice et al. 2010). The genotype of each animal was identified via PCR.

The experimental protocols were approved by the Institute of Animal Studies at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Standing Committee on Animals of Harvard Medical Area, and followed the recommendations of current National Institutes of Health and American Physiological Society guidelines.

Isolated perfused heart preparation and measurement of contractile performance

Mice were heparinized (100 units, i.p.) 15 min before experiments and were humanely killed via cervical dislocation. Hearts were quickly isolated and perfused in the Langendorff mode as described (Saupe et al. 1998). Briefly, the chest was opened and the heart was excised, arrested in ice-cold buffer and connected via the aorta to the perfusion cannula. Retrograde perfusion was carried out at a constant coronary perfusion pressure of 75 mmHg at 37°C with phosphate-free Krebs–Henseleit (KH) buffer containing (in mm): NaCl 118, KCl 5.3, CaCl2 2.5, MgSO4 1.2, EDTA 0.5, NaHCO3 25, glucose 10 and pyruvate 0.5 equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2, yielding a pH of 7.4. Right ventricular drainage was accomplished by incision of the pulmonary artery. A thin polyethylene tube (PE-10) placed through the apex of the LV was used to drain the effluent from the Thebesian veins. A water-filled balloon, custom-made of polyvinylchloride film, connected to a pressure transducer (Statham P23Db, Gould Statham Inc., Medical Provision Department, Oxnard, CA, USA) was used for continuous recording of LV contractile performance. The balloon matched the size of the ventricular cavity and was inflated to set LV end-diastolic pressure (EDP) to ∼10 mmHg; the balloon volume was then held constant. Systolic and diastolic isovolumic contractile performance data were collected online at a sampling rate of 200 Hz using a commercially available data acquisition system (MacLab; ADInstruments Pty, Milford, MA, USA). Coronary flow rate was measured by collecting coronary sinus effluent through the suction tube.

31P-NMR spectroscopy and measurement of metabolite concentrations

Isolated perfused hearts were placed in a 10 mm glass NMR sample tube and inserted into a custom-made 1H/31P double-tuned probe situated in an 89 mm bore 9.4 T superconducting magnet. To improve homogeneity of the NMR-sensitive volume, the perfusate level was adjusted so that the heart was submerged in buffer. 31P-NMR spectra were obtained without proton decoupling by using a 60°C flip angle, 15 μs pulse width, 2.4 s recycle time, 6000 Hz sweep width and 2 K data points at 161.94 MHz on a GE-400 wide-bore Omega spectrometer (General Electric, Fremont, CA, USA). Spectra were collected during either 16 or 40 min periods and consisted of data averaged from 312 or 1040 free induction decays, respectively. Spectra were analysed using 20 Hz exponential multiplication and zero and first-order phase corrections.

The resonance areas corresponding to ATP, PCr and inorganic phosphate (Pi) were quantified using Bayesian Analysis software (G. L. Bretthorst, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA). Bayesian Analysis software uses a direct statistical analysis of the free induction decay amplitudes, which corresponds to the resonance areas. By comparing the amplitude under the peaks from fully relaxed (recycle time 15 s) and those of partially saturated (recycle time 2.4 s) spectra, the correction factors for saturation were calculated for ATP (1.0), PCr (1.2), and Pi (1.15).

To determine the cytosolic concentration of ATP, the absolute resonance amplitude corresponding to [γ-P]ATP in the 31P-NMR spectra during baseline perfusion was normalized by heart weight. Since the Lowry protein content (which minimizes detection of extracellular matrix protein and thereby approximates myocyte protein content) (Lowry et al. 1951) was indistinguishable among the six groups (not shown), we make the assumption that the ratio of intracellular volume to cardiac mass of 0.48 μl (mg wet weight)−1 was the same for all hearts. In this case, amplitude units (g wet weight)−1 is directly proportional to the absolute intracellular concentrations. The value of 10 mm for [ATP] for αR92 mouse myocardium was used to calibrate the mean [γ-P]ATP peak amplitude of the 31P-NMR spectra obtained during baseline perfusion period. Changes in ATP, PCr and Pi concentrations during the protocols were calculated by multiplying the ratio of their resonance peak amplitude to the mean amplitude of the [γ-P]ATP peaks of the initial baseline spectrum for wild-type hearts by 10 mm. Intracellular pH was determined by comparing the differences in the chemical shifts of Pi and PCr resonances in each spectrum to values from a standard curve; the chemical shift of Pi but not PCr varies with pH.

Cytosolic free [ADP] was calculated using the equilibrium expression for the creatine kinase reaction and values for ATP, PCr, creatine (Kammermeier, 1973), and H+ concentrations obtained by NMR spectroscopy and biochemical assay: [ADP] = ([ATP][free Cr])/([PCr][H+]Keq), where Keq is 1.66 × 109 m−1 for a [Mg2+] of 1.0 mm. Cytosolic free [AMP] was calculated using the equilibrium expression for the adenylate kinase reaction and values for ATP and ADP: [AMP] = [ADP]2/[ATP]Keq, where Keq is 1.05.

The free energy released by ATP hydrolysis (ΔG∼ATP) is used to drive the ATPase reactions in the cell. Although ΔG∼ATP is a negative value, the change in free energy due to ATP hydrolysis is a positive value. Here we describe changes in ΔG∼ATP in absolute values, denoted as |ΔG∼ATP|, and calculated as |ΔG∼ATP| (kJ mol−1) = |ΔG°+RTln([ADP][Pi]/[ATP])|, where ΔG° (−30.5 kJ mol−1) is the value of ΔG∼ATP under standard conditions of molarity, temperature, pH and [Mg2+], R is the gas constant (8.3 J mol−1 K−1), and T is the temperature in kelvins.

Protocols

For each protocol, experiments were performed using littermate mouse hearts from one of the following cohorts. Cohort 1 consisted of 14 αR92, 12 βR92, 11 αR92Q and 12 βR92Q hearts; cohort 2 consisted of 6 αR92, 10 βR92, 11 αR92L and 11 βR92L; cohort 3 consisted of 6 αR92, 4 βR92, 4 αR92Q and 4 βR92Q hearts; the results are presented as four-way matches. The total number of hearts studied was 105.

Two protocols were used. In the first protocol, hearts were perfused with KH buffer containing 2 mm free Ca2+ (total 2.5 mm); hearts were not paced. After a 30 min stabilization period, isovolumic contractile performance and 31P-NMR spectroscopy were measured simultaneously for 16 min. Hearts were then paced at 420 beats min−1 using monophasic square-wave pulses delivered from a stimulator (model S88; Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA) through salt-bridge pacing wires consisting of PE-90 tubing filled with 4 m KCl in 2% agarose. Parameters of isovolumic contractile performance and energy metabolites detected by 31P-NMR spectroscopy were measured simultaneously for 16 min. The pacing was then turned off and, after 16 min, hearts were perfused with KH buffer containing 300 mm dobutamine (final concentration). Based on preliminary experiments, this dose of dobutamine produced >90% of the maximum contractile response. After steady state was reached (<3 min), cardiac function and 31P-NMR spectroscopy were again measured simultaneously for another 16 min. This protocol was used for cohorts 1 and 2.

In the second protocol, hearts from cohort 3 were perfused with normal KH buffer, unpaced, and then subjected to KCl-arrest. Preliminary experiments showed that increasing the KCl concentration in the buffer to 20 mm was sufficient to arrest the mouse heart; higher concentrations injured the hearts. Isovolumic contractile performance (rate pressure product, RPP = 0 during KCl-arrest) and 31P-NMR spectroscopy (40 min at baseline and during arrest) were measured simultaneously throughout the protocol.

At the end of each experiment, hearts were removed from the perfusion apparatus, blotted and weighed. Atria and ventricular weights, body weights and tibia lengths were determined.

Statistical analyses

All results are expressed as means ± SEM. For each protocol, differences among groups were compared by one- or two-way factorial ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferoni tests as appropriate, and changes between baseline and high workload were compared by repeated-measures. Linear relationships between RPP and |ΔG∼ATP| were fitted using the least squares method. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA), and differences were declared statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Physical characteristics of the mice and their hearts are presented in Table 1. Briefly, body weights, heart weights and right ventricular weights were similar for the six groups; atrial weights were ∼2-fold higher in all transgenic mouse hearts while LV weights were ∼25% smaller for βR92Q and βR92L mice.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cTnT mutant mice

| Genotype | αR92 | βR92 | αR92Q | βR92Q | αR92L | βR92L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 29 | 26 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 11 |

| Sex | M:15, F:14 | M:13, F:13 | M:4, F:12 | M:5, F:11 | M:6; F:5 | M:4, F:7 |

| BW (g) | 24.6 ± 0.7 | 25.4 ± 0.8 | 25.4 ± 1.4 | 22.8 ± 0.9 | 25.4 ± 0.9 | 23.4 ± 0.7 |

| Atria mass (mg) | 7 ± 1 | 12 ± 2* | 13 ± 2* | 15 ± 2* | 13 ± 2* | 19 ± 3* |

| RV mass (mg) | 20 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | 20 ± 2 | 19 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 |

| LV mass (mg) | 78 ± 2 | 85 ± 3 | 76 ± 8 | 64 ± 3*†‡ | 70 ± 2 | 64 ± 2*†‡ |

| HW (mg) | 105 ± 3 | 118 ± 4 | 109 ± 10 | 98 ± 5 | 100 ± 4 | 99 ± 4 |

| HW/BW (mg g−1) | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.1 |

See text for definitions. Data are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs.αR92; †P < 0.05 vs.βR92; ‡P < 0.05 vs.αR92Q. Tibia length (17–18 mm) was the same for all groups, and LV weight normalized to tibia length showed the same statistical pattern as unnormalized LV mass (not shown).

For each protocol, we used littermate mouse hearts perfused in the Langendorff mode under identical conditions of perfusion pressure, temperature, buffer composition, pacing rate, initial end diastolic pressure and coronary flow rate, and the same stimuli to either increase or decrease workload. To increase workload abruptly and thereby assess contractile reserve, we used two stimuli: pacing to increase heart rate (HR) (from 360 to 420 beats min−1) without increasing developed pressure (DevP) and supplying the inotropic agent dobutamine, which increases both HR and DevP. To decrease workload, we increased the concentration of KCl in the buffer to 20 mm to arrest the mouse heart. By combining the non-invasive tool of 31P-NMR spectroscopy and the well-controlled isolated Langendorff-perfused mouse heart (Saupe et al. 1998), we made simultaneous measurements of systolic and diastolic isovolumic contractile performance and energetics at different levels of work for each heart. Indices of systolic contractile performance measured were left ventricle (LV) systolic pressure (LVSP), DevP (the difference between LVSP and EDP), the product of HR and DevP (RPP) and the rate of tension development (+dP/dt); indices of diastolic contractile performance measured were EDP and the rate of relaxation (−dP/dt). Indices of energetics determined were [ATP], [ADP], [AMP], [PCr], [Pi], pH and |ΔG∼ATP|. We used these results to make comparisons for three pairs of work states: (1) unpaced at baseline conditions and during perfusion with dobutamine, (2) paced during baseline conditions followed by perfusion (unpaced) with dobutamine and (3) unpaced at baseline followed by arrest. This approach allowed us to calculate the change in the free energy available from ATP hydrolysis caused by increasing or decreasing workload, and hence the energetic cost of tension development. It also allowed us to define indices of contractile performance and energetics at each workload for six unique genotypes.

Substituting ββ-MyHC for αα-MyHC in wild-type R92 cTnT mouse hearts has no effect on either contractile performance or energetics

For the R92Q cohort, contractile performance results are shown in Figs 1 and 2; representative 31P-NMR spectra are shown in Fig. 3 and average metabolite results are shown in Figs 4 and 5. For the R92L cohort, contractile performance data are shown in Fig. 6; results from the 31P-NMR measurements are shown in Fig. 7.

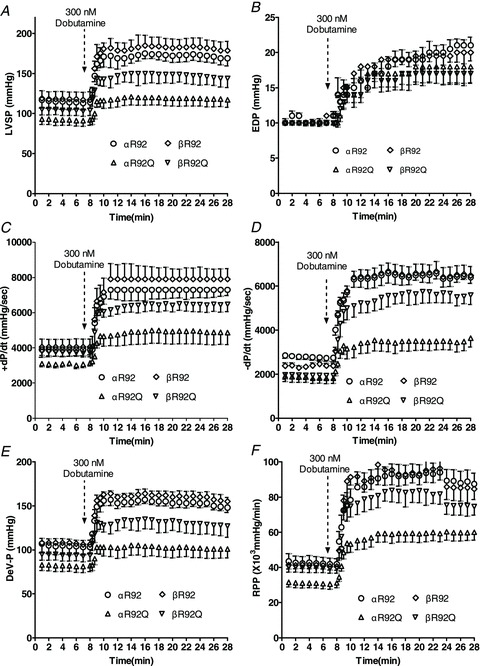

Figure 1. Indices of contractile performance averaged over 1 min intervals before, during (20 s intervals) and after supplying the inotrope dobutamine to a subset of isolated perfused αR92, βR92, αR92Q and βR92Q mouse hearts showing that substituting β-myosin heavy chain (MyHC) for α-MyHC substantially rescues the dysfunctional R92Q phenotype.

A, left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP); B, LV end diastolic pressure (EDP); C, rate of LV tension development; (+dP/dt); D, rate of LV relaxation (−dP/dt); E, LV developed pressure (DevP); F, rate pressure product (RPP). Average heart rate was 410 beats min−1 at baseline and 560 beats min−1 with dobutamine. Data shown are means ± SEM, n = 4–5 per group.

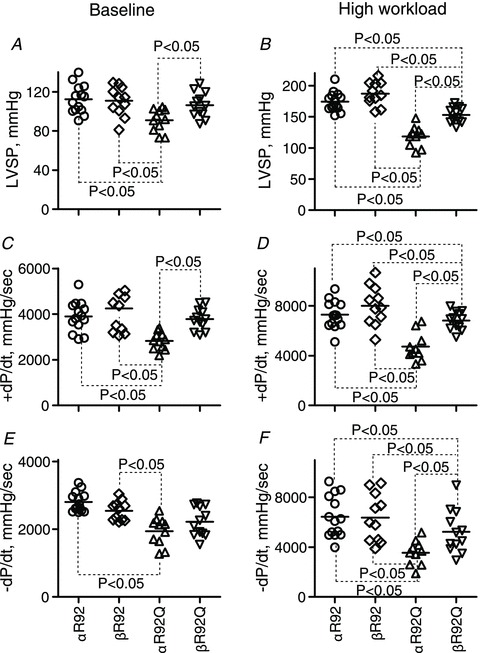

Figure 2. Select indices of contractile performance for isolated perfused αR92, βR92, αR92Q and βR92Q mouse hearts at baseline (paced, left) and high workload (right) in response to 300 nm dobutamine.

Increasing β-MyHC expression substantially reversed impaired contractile performance characteristics of intact hearts bearing the R92Q cTnT mutation. Data shown are individual values for n = 11–14 per group, and the horizontal lines are mean values. There were no sex differences in these parameters. A and B, left ventricular pressure, LVSP; C and D, the rate of LV tension development, +dP/dt; E and F, the rate of LV relaxation, −dP/dt.

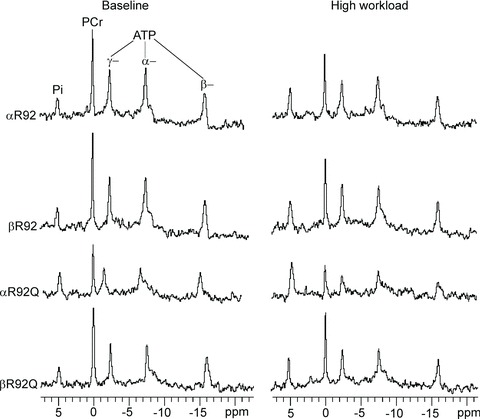

Figure 3. Representative 31P-NMR spectra from 5-month-old αR92, βR92, αR92Q and βR92Q mouse hearts, showing that increased β-MyHC expression rescued the energetic phenotype of αR92Q mouse hearts both at baseline (left) and high workload (right) in response to 300 nm dobutamine.

Resonance areas from left to right correspond to inorganic phosphate (Pi), phosphocreatine (PCr), and [γ-P]-, [α-P]- and [β-P]ATP. Resonance areas are scaled to the ATP resonance area at baseline for αR92 mouse hearts. See Methods for the parameters for data acquisition. Note the high Pi and the low PCr and ATP resonance areas for αR92Q hearts and the normal resonance areas for βR92Q.

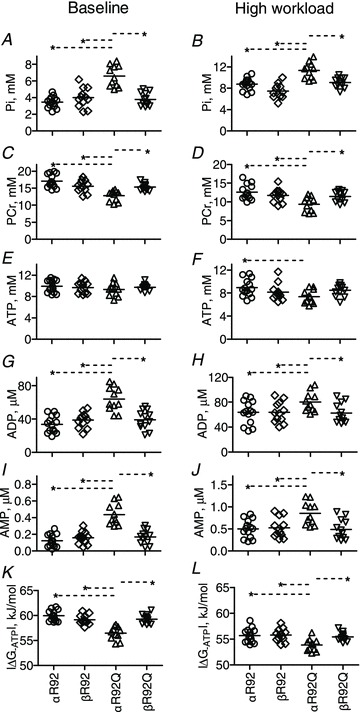

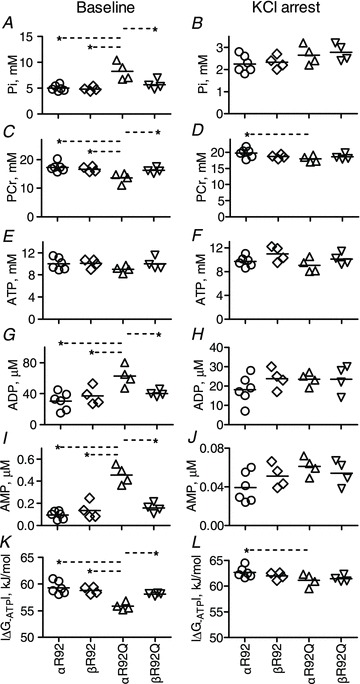

Figure 4. Select indices of whole heart energetics for αR92, βR92, αR92Q and βR92Q hearts at baseline (paced, left) and high workload (right) in response to 300 nm dobutamine; note the different scales for the y-axes for some parameters.

Increasing β-MyHC expression substantially reversed the impaired energetic phenotype of intact hearts bearing the R92Q cTnT mutation. Data shown are individual values for n = 11–14 per group, and the horizontal lines are mean values. There are no sex differences in these parameters. A and B, inorganic phosphate, Pi; C and D, phosphocreatine, PCr; E and F, ATP; G and H, ADP; I and J, AMP; K and L, free energy of ATP hydrolysis, |ΔG∼ATP|. *P < 0.05.

Figure 5. Select indices of whole heart energetics for αR92, βR92, αR92Q and βR92Q hearts at baseline (left) and during KCl-arrest (right).

Note the different scales for y-axes of most comparisons. Increasing β-MyHC expression substantially rescued the impaired energetic phenotype of intact hearts bearing the R92Q cTnT mutation. Data shown are individual values for n = 4–6 per group, and the horizontal lines are mean values. *P < 0.05. A and B, inorganic phosphate, Pi; C and D, phosphocreatine, PCr; E and F, ATP; G and H, ADP; I and J, AMP; K and L, free energy of ATP hydrolysis, |ΔG∼ATP|.

Figure 6. Select indices of contractile performance for isolated perfused αR92, βR92, αR92L and βR92L mouse hearts at baseline (left) and high workload (right) in response to 300 nm dobutamine.

Increasing β-MyHC expression had no effect on impaired contractile performance characteristics of intact hearts bearing the R92L cTnT mutation. Data shown are individual values for n = 6–11 per group, and the horizontal lines are mean values. A and B, left ventricular pressure, LVSP; C and D, the rate of LV tension development, +dP/dt; E and F, the rate of LV relaxation, −dP/dt.

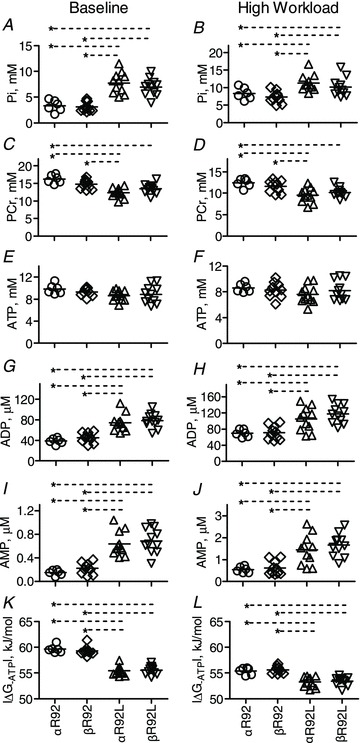

Figure 7. Select indices of whole heart energetics for αR92, βR92, αR92L and βR92L hearts at baseline (paced, left) and high workload in response to 300 nm dobutamine.

Note the different scales for the y-axes for most comparisons. Increasing β-MyHC expression failed to rescue the impaired energetic phenotype of intact hearts bearing the R92L cTnT mutation. Data shown are individual values for n = 6–11 per group, and the horizontal lines are mean values. *P < 0.05. A and B, Pi; C and D, PCr; E and F, ATP; G and H, ADP; I and J, AMP; K and L, free energy of ATP hydrolysis, |ΔG∼ATP|.

Previous studies by our group have found that switching the MyHC composition in wild-type C57BL/6 mouse hearts from 95/5%αα/ββ-MyHC to 20/80%αα/ββ-MyHC had no significant effect on baseline isovolumic contractile performance at either the whole heart or myocyte levels (Rice et al. 2010). Here we test whether replacing the endogenous fast murine MyHC with the slow murine MyHC in hearts with normal thin filament composition altered any energetic or contractile performance parameter at four work states: baseline without pacing, baseline with pacing, high work elicited by the inotrope dobutamine and during arrest. As each litter contained αR92 and βR92 cTnT mice, every litter yielded one or more of these comparisons. We describe in detail the expected values for indices of systolic and diastolic contraction and energy-metabolites at different work states for hearts with normal thick and thin filament proteins, αR92 hearts, and whether they differ from hearts with β-MyHC (βR92 hearts). These indices were then used to calculate two key parameters: RPP, the index of contractile performance that takes into account changes in HR, LVSP and EDP, and ΔG∼ATP, the free energy available from ATP hydrolysis. In subsequent sections describing the other genotypes studied, we follow this same approach.

Baseline indices of cardiac performance for both αR92 and βR92 hearts were typical of isolated perfused mouse hearts: LVSP was >100 mmHg, the ratio of +dP/dt to −dP/dt was >1 and RPP was ∼41 × 103 mmHg min−1 (Figs 1, 2 and 6). Increasing HR by 17% (from 360 to 420 beats min−1) did not change DevP. αR92 and βR92 hearts had equally robust responses to inotropic challenge with dobutamine, increasing HR to >520 beats min−1 and DevP from ∼100 to ∼180 mmHg; EDP and the rates of tension development and relaxation doubled (Figs 1, 2 and 6). RPP, the index of contractile performance that takes into account changes in HR, LVSP and EDP, increased from ∼41 × 103 to ∼85 × 103 mmHg min−1. The minute-to-minute values for the systolic parameters LVSP, +dP/dt, DevP and RPP and for the diastolic parameters EDP and −dP/dt observed before, during and after dobutamine infusion shown for a subset of these hearts in Fig. 1 are essentially superimposable. αR92 and βR92 hearts also arrested at the same perfusate [KCl].

At each work state, αR92 and βR92 hearts had comparable values for [PCr], [ATP], [Pi] and pH measured by 31P-NMR spectroscopy and for [ADP] and [AMP] calculated using the creatine kinase and adenylate kinase equilibrium expressions (Figs 3, 4 and 7). αR92 and βR92 hearts at baseline had the expected ratio for PCr/ATP of ∼1.7 and normal [ATP] (∼10 mm), [ADP] (∼0.040 mm), [AMP] (∼0.15 μm), [Pi] (∼4 mm) and pH (∼7.1). As expected for large and abrupt increases in RPP with dobutamine infusion, [PCr] fell by ∼4 mm, [ADP] and [Pi] increased nearly 2-fold, [AMP] increased nearly 4-fold, while [ATP] and pH did not change. With arrest, the opposite occurred: [PCr] increased by ∼2 mm; [ADP], [AMP] and [Pi] each decreased nearly 2-fold, while [ATP] and pH did not change.

Changes in these energetic parameters caused by altered isovolumic work can be expressed as a single parameter, the free energy of ATP hydrolysis, ΔG∼ATP; the variables used in this calculation are [ATP], [ADP] and [Pi]. ΔG∼ATP represents the amount of free energy available from ATP hydrolysis that can be used to support thermodynamically unfavourable ATPase reactions in the cell. For well-oxygenated isolated beating rodent hearts, |ΔG∼ATP| is typically ∼60 kJ mol−1 for baseline RPPs of 30–40 × 103 mmHg min−1 and ∼54–56 kJ mol−1 for high RPPs of 60–80 mmHg min−1, an operating range for the healthy perfused heart of only ∼6 kJ mol−1. |ΔG∼ATP| has not been reported for KCl-arrest in the mouse heart but would be expected to be >60 kJ mol−1. In accord with this, values for |ΔG∼ATP| and RPP for both αR92 and βR92 hearts were ∼55.5 kJ mol−1 at high work states (RPP ∼85 × 103 mmHg min−1), ∼60 kJ mol−1 for baseline performance (RPP ∼41 × 103 mmHg min−1) and ∼62 kJ mol−1 for arrest (Figs 4, 5 and 7).

In summary, whether comparisons were made for hearts that were paced or unpaced, working at high workloads or arrested, or were littermates of either R92Q or R92L mice, there were no differences between αR92 and βR92 hearts in any measured parameter of systolic or diastolic performance or energetics. Importantly, the absence of any consequences of the MyHC replacement in C57BL/6 wild-type hearts on indices of either isovolumic contractile performance or energetics at any work state means that changes caused by switching myosin isozymes in hearts with mutant R92 cTnT can be ascribed to differences in thick–thin filament interactions due to the mutation in the TM-binding domain of cTnT.

Substituting ββ-MyHC for αα-MyHC in R92Q cTnT mouse hearts improves both contractile performance and energetics

Indices of contractile performance for the R92Q cohort are shown in Figs 1 and 2; representative 31P-NMR spectra are shown in Fig. 3 and average metabolite results are shown in Figs 4 and 5.

Comparing R92 and αR92Q hearts

Indices of both systolic and diastolic contractile performance at baseline for αR92Q hearts differed from those for αR92 hearts (and also βR92 hearts). Compared to values for αR92 hearts, baseline LVSP (∼19%), DevP (∼20%) and RPP (∼27%) were all lower. Rates of tension development and relaxation were ∼28% lower. Hearts used for the arrest protocol were similarly dysfunctional. Challenging the hearts to increase work with dobutamine exacerbated both systolic and diastolic dysfunction. All parameters of systolic performance were 33–36% lower and the rate of relaxation was ∼45% lower than for αR92 hearts. The increase in RPP with the inotrope dobutamine (i.e. contractile reserve) for αR92 hearts was ∼43 × 103 mmHg min−1 whereas it was only 25 × 103 mmHg min−1 for αR92Q hearts.

Compared to αR92 hearts, αR92Q hearts at baseline had lower [PCr] (by ∼24%) and higher [Pi] (∼1.8-fold), [ADP] (∼1.9-fold) and [AMP] (∼3.8-fold); [ATP] and pH were the same. As a result of these changes in metabolite concentrations, |ΔG∼ATP| was 3.4 kJ mol−1 lower than for αR92 hearts. These large differences became even greater during inotropic challenge: [PCr] fell below 10 mm, and [Pi], [ADP] and [AMP] all remained higher than values for either αR92 or βR92 hearts. The low value for [PCr] in αR92Q hearts is not due to a decrease in total [creatine] (24, 23 and 23 mm for αR92, βR92 and αR92Q hearts, respectively). Instead, the decrease in [PCr] is due to increased ATP utilization in αR92Q hearts. The increase in ATP utilization during dobutamine challenge in αR92Q hearts was so great that [ATP] was not preserved and fell to 7.4 mm and |ΔG∼ATP| fell to 53.6 kJ mol−1, ∼2 kJ mol−1 lower than observed for either αR92 or βR92 hearts functioning at even higher RPPs during inotropic challenge.

The energetic profiles for αR92, βR92 and αR92Q hearts during arrest, when external work is absent and ATP is utilized primarily for cellular housekeeping functions, are similar; however, |ΔG∼ATP| for αR92Q hearts was 1.5 kJ mol−1 lower than for αR92 hearts. Even arresting αR92Q hearts did not completely normalize its energetic profile.

Substituting ββMyHC for ααMyHC in R92Q hearts

Substituting ββMyHC for ααMyHC in the presence of the R92Q mutation in cTnT partially rescued the defects in cardiac performance and energetics. At baseline, indices of systolic performance for βR92Q were indistinguishable from those of either αR92 or βR92 hearts; only the rate of relaxation was refractory to the switch in MyHC.

Compared to αR92Q hearts at high workloads, replacing MyHC in R92Q cTnT mutant hearts improved all indices of systolic performance by ∼40%; the rate of relaxation also improved by ∼40%. As shown in Figs 1 and 2, the rescue was not complete, however. Comparing αR92 and βR92Q hearts at high workloads, indices of systolic performance for βR92Q hearts were lower by 7–13%, the increase in RPP was 14% lower, and the rate of relaxation was ∼19% lower.

The rescue for energetics was essentially complete both at baseline and with dobutamine challenge (Figs 3, 4 and 5). Compared to αR92Q hearts, [PCr] was higher while [Pi], [ADP] and [AMP] were lower for βR92Q hearts. Values of |ΔG∼ATP|, 59 and 55 kJ mol−1 at baseline and with dobutamine, respectively, for βR92Q hearts were 2–3 kJ mol−1 higher than for αR92Q hearts, and were the same as for hearts containing normal cTnT.

Thus, substituting ββMyHC for ααMyHC in the thick filaments of sarcomeres of mouse hearts bearing the R92Q mutation in the TM binding domain of cTnT rescued energetic defects caused by the perturbations in thin filament structure and dynamics. Systolic performance was nearly normalized, but diastolic performance remained impaired.

Substituting ββMyHC for ααMyHC in R92L cTnT mouse hearts rescues neither contractile dysfunction nor energetic deficiency

Based on our previous work showing that changes in contractile performance and energetics caused by R92 cTnT mutations were mutation-specific (He et al. 2007), we then tested whether replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC in hearts with a different mutation at the R92 hotspot also corrected either contractile or energetic defects. Contractile performance data are shown in Fig. 6; results from the 31P-NMR measurements are given in Fig. 7.

Unlike the defects in systolic contractile performance observed for αR92Q hearts at baseline, indices of systolic performance of αR92L hearts at baseline were the same as for αR92 and βR92 hearts; only the rate of relaxation was lower (−22%). αR92L hearts demonstrated work-induced systolic dysfunction as well as exacerbated diastolic dysfunction. Compared to αR92 and βR92 hearts at high work, indices of systolic performance for αR92L hearts at high workloads were all ∼21% lower; the rate of tension development was ∼10% lower while the rate of relaxation was ∼21% lower.

Although systolic performance at baseline was normal for αR92L hearts, indices of energetics were abnormal. Compared to αR92 and βR92 hearts, [PCr] was lower (∼23%) while [Pi] (2.3-fold), [ADP] (1.9-fold) and [AMP] (4.3-fold) were all higher. [ATP] and pH (data not shown) were the same as for αR92 and βR92 hearts. |ΔG∼ATP| was 4 kJ mol−1 lower. Increasing work lowered [PCr] to less than 10 mm, [Pi] increased to 11 mm, [ADP] increased to over 0.1 mm and [AMP] was nearly 3 times higher than for αR92 and βR92 hearts. |ΔG∼ATP| fell another 2.2 kJ mol−1, to 53 kJ mol−1. This profile is similar to that observed for αR92Q hearts at high work states.

Thus, in sharp contrast to the results for R92Q hearts, substituting ββMyHC for ααMyHC had no effect on either energetics or contractile performance; all results for αR92L and βR92L hearts were indistinguishable. The rescue of the mutant R92 cTnT phenotypes by remodelling the thick filament by switching MyHC composition is mutation-specific.

Altering the cost of increasing contraction in R92 cTnT mutant mouse hearts by remodelling the thick filament

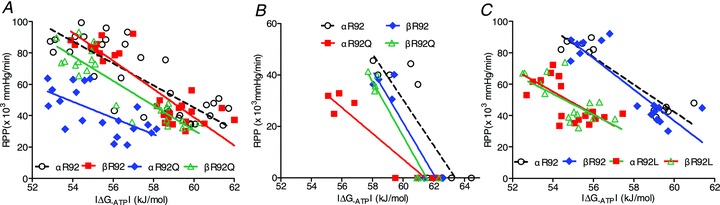

To determine the energetic cost of increasing contraction, we defined the relationships between the index of isovolumic contractile performance, RPP, and the change in the free energy available from ATP hydrolysis, |ΔG∼ATP|, for three pairs of work states: unpaced baseline conditions and high work, paced at baseline and high work, and unpaced at baseline and arrest. Figure 8 shows these relationships for the R92Q cohort comparing the fits using paced vs. unpaced baseline values; Fig. 9A and B shows linear fits for the R92Q cohorts using unpaced values at baseline and for the arrest experiment, respectively; Fig. 9C shows the results for the R92L cohort.

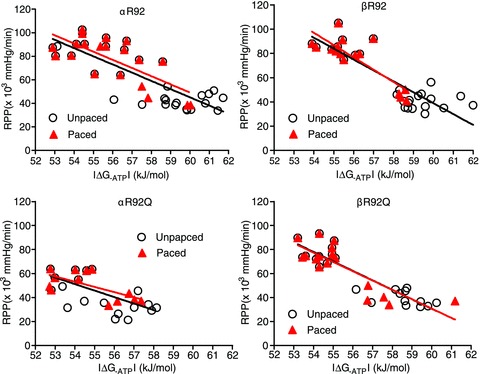

Figure 8. Relationships between RPP and |ΔG−ATP| for the each of the four genotypes in the R92Q cohort comparing linear fits using unpaced baseline data vs. paced baseline data with high workload in response to 300 nm dobutamine.

For each genotype, the linear fits are superimposable. These results show that the slope of the fits for αR92Q hearts is smaller than for the other three genotypes and that replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC in αR92Q hearts normalizes the RPP–ΔG∼ATP relationship.

Figure 9.

A, relationships between RPP and |ΔG∼ATP| for the R92Q cohort at baseline (unpaced) and high workload in response to 300 nm dobutamine. For αR92Q hearts, the energetic cost of increasing RPP is greater than for the other groups, and contractile reserve is lower. Replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC rescues this phenotype. B, relationships between RPP and |ΔG∼ATP| for the R92Q cohort at baseline (unpaced) and arrest, again showing the higher energetic cost of increasing RPP for αR92Q hearts and that replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC rescues this phenotype. C, relationships between RPP and |ΔG∼ATP| for the R92L cohort at baseline (unpaced) and high workload in response to 300 nm dobutamine. Although the slopes of the linear fits for αR92L and βR92L hearts are near normal, all data are shifted to the left and downward, showing contractile and energetic dysfunction. In contrast to the results for R92Q hearts, switching MyHC isoform did not alter the RPP–|ΔG∼ATP| relationship.

An increase in RPP in mouse hearts results in lower |ΔG∼ATP|, i.e. the energy available from ATP hydrolysis decreases as a result of increasing contractile performance. The four panels in Fig. 8 show that, for each genotype, the linear fits for RPP vs.|ΔG∼ATP| for the work state jump using either paced or unpaced baseline values are indistinguishable. The fits for αR92 and βR92 hearts (upper panels) are the same, showing that the type of MyHC in the thick filament does not change the cost of increasing contraction for C57BL/6 hearts with normal thin filament proteins. The relationships for αR92Q hearts (lower left panel) are clearly different from the other three genotypes: the slopes of these two fits are lower than for the other genotypes shown in the other panels.

Figure 9A compares all four genotypes. For αR92Q hearts, baseline RPP is lower and |ΔG∼ATP| is shifted to the left, i.e. even supporting low baseline conditions is more energy costly for αR92Q hearts. With the identical challenge to increase work, the increase in RPP (contractile reserve) for a similar change in |ΔG∼ATP| is substantially less for αR92Q hearts. For example, for a change in |ΔG∼ATP| from 58 to 54 kJ mol−1 for αR92 hearts, RPP (×103 mmHg min−1) increased from 66 to 98 while it increased only from 27 to 46 for αR92Q hearts. At a given RPP, the differences in |ΔG∼ATP| are remarkably large: for example, at a low RPP (×103 mmHg min−1) of 40, |ΔG∼ATP| is 61 kJ mol−1 for αR92 hearts and only 55 kJ mol−1 for αR92Q hearts. This difference of 6 kJ mol−1 is close to the maximum difference observed for perfused beating hearts with normal thick and thin filament proteins forced to increase work, and shows the high energetic cost for αR92Q hearts to maintain even low work states. Replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC in R92Q hearts shifts the curve upwards and to the right. Figure 9B shows the results for the arrest experiment. Again, the fit for αR92Q is unique and replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC shifts the relationship to the right, close to the relationships for the hearts with normal thin filament proteins. Thus, replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC normalizes the cost of increasing contraction in R92Q hearts and substantially rescues the defects in both energetics and contractile performance at all work states.

Figure 9C shows these relationships for the R92L cohort. As observed for the αR92Q cTnT mutation, the relationship for αR92L hearts is shifted to the left compared to hearts with normal thick and thin filament proteins, showing an increased energy cost to maintain even low levels of baseline contractile performance and lower contractile reserve for αR92L hearts. In sharp contrast to the results for hearts with the R92Q mutation, however, replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC rescued neither whole heart energetics nor contractile performance. Neither did it make it worse.

Table 2 shows the parameters for the linear fits of RPP and |ΔG∼ATP| by genotype and by protocol; the inverse of the slope represents the energetic cost of increasing contraction at the whole heart level (|ΔG∼ATP|/RPP in arbitrary units). For each condition, for αR92 and βR92 hearts, the cost of increasing contraction is ∼0.11. In contrast, for each comparison for αR92Q, the cost is twice as high, ∼0.21. Replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC in hearts bearing the R92Q mutation in cTnT corrected this defect. The pattern is different for the R92L cTnT mutation. The cost of increasing contraction for the R92L cTnT mutation was intermediate between the R92Q mutation and αR92 (or βR92), and replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC had no effect. Thus, remodelling the thick filament to contain the slow MyHC isozyme rescued the high cost of increasing contraction for hearts bearing the R92Q, but not R92L, cTnT mutation.

Table 2.

Linear regression parameters for the relationships between RPP and IΔG∼ATP I for six genotypes for three protocols: unpaced baseline conditions followed by 300 nM dobutamine, paced baseline conditions followed by 300 nm dobutamine, and unpaced baseline conditions followed by arrest with 20 mm KCl

| Unpaced/dobutamine | Paced/dobutamine | Low work/arrest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αR92 | Equation | Y = −8.2X + 541 | Y = −8.7X + 560 | Y = −9.0X + 573 |

| 1/slope | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | |

| βR92 | Equation | Y = −9.4X + 603 | Y = −10.9X + 683 | Y = −10.1X + 627 |

| 1/slope | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 | |

| αR92Q | Equation | Y = −4.7X + 300 | Y = −4.5X + 298 | Y = −5.0X + 308 |

| 1/slope | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.20 | |

| βR92Q | Equation | Y = −8.0X + 520 | Y = −7.4X + 474 | Y = −10.6X + 652 |

| 1/slope | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.09 | |

| αR92L | Equation 1/slope | ND | Y = −6.5X + 403,0.15 | ND |

| βR92L | Equation 1/slope | ND | Y = −7.3X + 449,0.14 | ND |

Discussion

FHC-associated single amino acid replacements at R92 of cTnT cause mutation-specific changes in peptide dynamics, which lead to contractile dysfunction and impaired energetics assessed at the whole heart level. Using transgenesis to remodel the thick filament of the sarcomere in R92Q and R92L cTnT mouse hearts, here we test whether increasing the efficiency of the sarcomere by substituting the slow murine ββ-MyHC for the fast endogenous murine αα-MyHC would rescue the dysfunctional R92Q and R92L cTnT contractile and energetic phenotypes. We found that remodelling the thick filament of R92Q cTnT-containing sarcomeres in this way substantially rescued both contractile and energetic phenotypes of the dysfunctional R92Q hearts. In contrast to the near complete rescue of R92Q cTnT hearts, replacing the MyHC isozyme had no effect on the R92L phenotype. These results demonstrate that remodelling the thick filament of the sarcomere can alter sarcomere dynamics caused by FHC-associated single amino-acid mutations in thin filament proteins, but they also demonstrate that the rescue is mutation-specific. These results demonstrate the major role the thin filament protein cTnT plays in determining whole heart contractile function and energetics.

Unique phenotypes caused by different FHC-associated R92 missense mutations in cTnT with MyHC replacement

Using molecular dynamic simulations to study the stability and conformation of the cTnT peptide containing residues 70–170, our group has found that the presence of FHC-associated R92 mutations alters the flexibility around a hinge formed by residues 104–108, decreasing helical stability of the peptides. R92 cTnT mutations also differed in terms of motion quantified as the radius of gyration, with little motion for the wild-type peptide and marked mutation-specific differences in oscillations for peptides containing R92 mutations (Guinto et al. 2007). The consequences of these changes in cTnT peptide dynamics on the structure and function of the thin filament, on the interaction between thick and thin filaments and, when summed, on contractile performance and energetics of the intact heart are both precise and unique, and, importantly, cannot be predicted. This is well illustrated by the whole heart results of the present study.

Using well-characterized transgenic mouse models, we have used their energetic and contractile phenotypes to define the cost of increasing contraction of intact beating hearts bearing either the R92L or the R92Q cTnT mutation with either fast or slow MyHC in the thick filament. We compared work states created by arrest, by pacing and by challenge to increase work by supplying the inotrope dobutamine. Replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC in C57BL/6 mouse hearts with normal thin filaments did not alter the cost of increasing contraction. This is not the case for hearts bearing either the R92Q or R92L cTnT mutations. The cost of increasing contraction for R92Q hearts with ααMyHC was twice as high as for hearts with normal thick and thin filaments; for R92L hearts, it was ∼35% higher. Replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC normalized the cost of contraction for hearts bearing the R92Q cTnT mutation whereas it had no effect on hearts with R92L cTnT mutation. The changes in whole heart energetics and contractile performance resulting from the interaction of mutant thin filaments and the different myosin isoforms in the thick filament shown in the present study demonstrate the far-reaching through-space consequences of R92 mutations in the TM-binding domain of cTnT on sarcomere dynamics. Importantly, these changes in sarcomere dynamics are not subtle, but sum to alter whole heart contractile performance and energetics.

Consequences of energetic dysfunction caused by different FHC-associated R92 missense mutations in cTnT

αR92Q cTnT mutant hearts demonstrate energetic dysfunction at all workloads ranging from arrest to RPPs approximating in vivo contractile performance of the mouse. This is shown by lower [PCr], higher [ADP] and [Pi] and consequently lower |ΔG∼ATP| than for R92 cTnT hearts. The observation that [ATP] is lower in αR92Q hearts (and tending to lower levels for αR92L hearts) abruptly challenged to increase work compared to hearts with normal thin filament proteins also shows that ATP utilization exceeds ATP synthesis. This is the case despite the high levels of AMP observed for cTnT mutant hearts, which would be expected to conserve [ATP] by stimulating ATP-synthesizing reactions and inhibiting ATP-utilization reactions. These deficits in [ATP] approach the lower limit of [ATP] observed in the failing myocardium due to non-genetic causes (Ingwall, 2011).

One predicted consequence of such large deficits in |ΔG∼ATP|, ∼6 kJ mol−1, for R92 mutant hearts would be to limit how high a workload can be achieved by these hearts. Another is that these hearts would demonstrate impaired relaxation. Here studying intact hearts containing 60% (R92L) and 67% (R92Q) mutant cTnT, we observed large deficits in tension development, the rates of tension development and relaxation and the ability to increase work upon acute challenge. This is especially the case for the R92Q cTnT mutation. Diastolic contractile dysfunction was observed even at low work states for αR92Q hearts, and both αR92Q and αR92L hearts demonstrated work-induced diastolic contractile dysfunction. Energetic deficits would also increase the risk of R92 cTnT mutant hearts for greater damage during an ischaemic episode; this has yet to be tested.

Another prediction is that Ca2+ homeostasis would be different in R92 cTnT mutant hearts. Values of the free energy available from ATP hydrolysis found here for the cTnT mutant hearts were close to the thermodynamic limit for the sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+-ATPase (Tian et al. 1998). It is interesting to note that in our previous work we have shown that R92Q and R92L cTnT mutations negatively affect Ca2+ homeostasis in cardiomyocytes, with improvements in Ca2+ kinetics caused by the MyHC replacement (Rice et al. 2010; Ingwall, 2011). These changes were highly complex, and as seen here, mutation-specific, both with respect to magnitude at baseline (αα) and in a general lack of improvement for the βR92L line. While no direct mechanism for how primary changes in myofilament structure and function lead to alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis has been identified, it is likely to represent a compensatory response to sensed change in the interaction between Ca2+ and the thin filament. As this relationship can be modulated by the presence of myosin, it is not entirely surprising that, much like the mutation-specific effects on energetics, the different MyHC isoforms would also exhibit a similar effect on Ca2+ homeostasis, as we observed in our previous report.

On sarcomere efficiency

Recently, Cooke and colleagues presented a new kinetic model of cross bridge cycling that relates the thermodynamics of the rate-limiting step of the opening of the ADP-binding pocket of myosin and the rate of ADP release from the pocket to two important physiological measures – speed of contraction and work (Purcell et al. 2011). The model explains why fast myosins are less efficient than slow myosins. The transgenic mouse hearts designed to contain either fast or slow cardiac myosins studied here have properties at the whole heart level that are consistent with this thermodynamic model. Using a different strain of mice from that studied here, FVB/N, we have observed greater efficiency of contraction for hearts containing 83%ββ-MyHC than for hearts with >95%αα-MyHC (Hoyer et al. 2007). For the C57BL/6 strain studied here, there was a trend toward greater efficiency of contraction for βR92 hearts (steeper slopes for the RPP-|ΔG∼ATP| relationship).

The results presented here extend the notion of sarcomere efficiency focused solely on myosin to include the role of the thin filament. Importantly, and not predictable, the results presented in the present study suggest that sarcomeres containing both slow MyHC in the thick filament and the R92Q cTnT mutation in the crucial TM-binding domain of the thin filament are more efficient at work generation than R92Q cTnT sarcomeres with αα-MyHC in the thick filament. A different result was obtained for R92L hearts. For R92L cTnT hearts, the cost of contraction neither improved nor worsened with MyHC substitution. These results strongly suggest that the conformation of the TM-binding domain of cTnT induced by each unique amino acid substitution at R92 is a major, not minor, determinant of sarcomere function.

The type of MyHC expressed and chamber mass

Recently Simpson and colleagues defined the size and distribution of αα- and ββ-MyHC expressing cells in C57BL/6J mouse hearts stressed by transverse aortic constriction (TAC) (Lopez et al. 2011). The population of cells that expressed ββ-MyHC increased from 3% in normal mouse hearts to ∼25% in TAC hearts. Unexpectedly, these cells were 22–35% smaller than cells expressing αα-MyHC. Only cells expressing predominately αα-MyHC hypertrophied in TAC hearts.

The genetic strategy used here to switch the type of MyHC expressed in normal and mutant cTnT mouse hearts allows us to extend these results and relate chamber mass and expression of MyHC isozymes in normal and cTnT mutant hearts of C57BL/6 mice. We observed that switching the MyHC distribution from >95%/5%αα/ββ-MyHC to 20/80%αα/ββ-MyHC in mouse hearts with normal thin filament proteins had no effect on either left ventricle (LV) or right ventricle (RV) chamber mass; only atrial mass increased (by ∼71%). Essentially identical results have been obtained for normal female FVB/N mice (Hoyer et al. 2007). For ventricular mass to be unaffected in hearts composed of a majority of small cells containing primarily ββMyHC, the remaining αα-MyHC-containing ventricular cells would have to be twice as large as normal. Alternatively, the number of αα-MyHC-containing cells would have to be halved. We suggest that neither of these scenarios is likely. See Supplemental material for more discussion.

The presence of mutant cTnTs in sarcomeres containing predominantly αα-MyHC also did not alter chamber sizes. In contrast, chamber mass for cTnT mutant hearts with ββ-MyHC was different. For both βR92Q and βR92L hearts, absolute LV mass (and also LV/tibial length values) was ∼25% smaller than for non-mutant cTnT hearts with predominantly ββ-MyHC; values for RV mass were not different while values for atrial mass were even higher than for βR92 hearts. Based on these observations, we suggest that expression of ββ-MyHC alone may not be sufficient to reduce either myocyte or chamber mass, but rather smaller LV size results from expression of slow myosin isozyme in concert with the expression (or lack thereof) of other proteins induced as a result of TAC in the case of Simpson's mice and to the presence of mutant R92 cTnT hearts studied here. As human ventricular myocardium contains predominately ββMyHC, these results may explain why hearts of patients with FHC-associated mutations are often not hypertrophied.

Conclusions and implications

We have previously shown that single amino acid replacements at R92 in cTnT altered peptide structure and dynamics in the thin filament in such a way that whole heart contractile performance, especially diastolic performance, and energetics are impaired. The cost of contraction is greater and likely to contribute to adverse clinical outcome. Moreover, the conformational changes induced in the thin filament and the characteristics of contractile and energetic dysfunction are mutation-specific. Remodelling the thick filament by replacing ααMyHC with ββMyHC produced near-complete rescue of both energetics and contractile performance in R92Q cTnT mutant hearts while R92L cTnT mutant hearts were unaffected. Thus the type of myosin in the thick filament compensated for the adverse conformational changes in thin filament caused by the R92Q cTnT mutation, and did not worsen or rescue the R92L cTnT phenotype. As ββMyHC is the dominant myosin isozyme in human myocardium, this may be one mechanism explaining how FHC patients with the R92 cTnT mutations survive.

Our observations that amino acid substitutions at the same cTnT residue are affected differently by the ββ-myosin heavy chain substitution in the intact heart have several implications. First, they serve to emphasize the unpredictability of the consequences of remodelling the sarcomere, both for thick and thin filaments. They also demonstrate that the mechanism of the energetic rescue of cTnT mutant hearts is highly precise and depends on the conformation of many protein domains in the sarcomere. Importantly, they show that mutating the TM-binding domain of cTnT can have a major impact on energetic and contractile phenotypes. We suggest that complex animal models such as developed for this study bearing mutations in other protein domains or using other protein isoform switches should be useful in defining sarcomere dynamics and function in intact muscles. Finally, these results suggest that any therapeutic intervention targeting FHC-associated mutant sarcomeres will require a high-resolution definition of the structure and function of mutation-specific sarcomeres and how they function in the intact heart.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- αR92

wild-type cTnT with αα-MyHC

- αR92L

R92L cTnT with ααMyHC

- αR92Q

R92Q cTnT with ααMyHC

- βR92

wild-type cTnT with ββMyHC

- βR92L

R92L cTnT with βMyHC

- βR92Q

R92Q cTnT with ββMyHC

- cTn

cardiac troponin

- ΔG∼ATP

free energy available from ATP hydrolysis

- DevP

developed pressure

- EDP

end diastolic pressure

- FHC

familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- HR

heart rate

- LV

left ventricle

- LVSP

LV systolic pressure

- MyHC

myosin heavy chain

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PCr

phosphocreatine

- Pi

inorganic phosphate

- RPP

rate pressure product

- TM

troposmyosin

- TnT

troponin T

- TnI

troponin I

- TnC

troponin C

Author contributions

All mice were generated, housed and genotyped at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA. All NMR experiments were performed at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA. J.C.T. and J.S.I. were involved in the conception and design of the studies and interpretation of the data. H.H., K.H. and H.T. were involved in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data. R.R. and J.J. designed and carried out the double transgenic strategy with help from J.C.T. J.S.I. was mainly responsible for drafting the article, with critical input from all other authors. All authors approved the final version.

Authors’ present addresses

H. He: Department of Anaesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC 29425, USA.

K. Hoyer: Gilead Palo Alto, Inc., Palo Alto, CA 94304, USA.

H. Tao: Lacrimal Apparatus Center, Department of Ophthalmology, Armed Police General Hospital, Beijing 100039, P.R. China.

J. C. Tardiff: Department of Internal Medicine, Sarver Heart Center and Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of Arizona, 1656 East Mabel St, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA.

Supplementary material

Supplementry material

References

- Alpert NR, Brosseau C, Federico A, Krenz M, Robbins J, Warshaw DM. Molecular mechanics of mouse cardiac myosin isoforms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1446–1454. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00274.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barany M. ATPase activity of myosin correlated with speed of muscle shortening. J Gen Physiol. 1967;50(Suppl):197–218. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.6.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertz-Berger BR, He H, Dowell C, Factor SM, Haim TE, Nunez S, Schwartz SD, Ingwall JS, Tardiff JC. Changes in the chemical and dynamic properties of cardiac troponin T cause discrete cardiomyopathies in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18219–18224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509181102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinto PJ,ManningEP, Schwartz SD, Tardiff JC. Computational characterization of mutations in cardiac troponin T known to cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Theor Comput Chem. 2007;6:413–419. doi: 10.1142/S0219633607003271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinto PJ, Haim TE, Dowell-Martino CC, Sibinga N, Tardiff JC. Temporal and mutation-specific alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis differentially determine the progression of cTnT-related cardiomyopathies in murine models. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H614–626. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01143.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Javadpour MM, Latif F, Tardiff JC, Ingwall JS. R-92L and R-92W mutations in cardiac troponin T lead to distinct energetic phenotypes in intact mouse hearts. Biophys J. 2007;93:1834–1844. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.107557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer K, Krenz M, Robbins J, Ingwall JS. Shifts in the myosin heavy chain isozymes in the mouse heart result in increased energy efficiency. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingwall J. Energetic basis for heart failure. In: Mann D, editor. Heart Failure: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease. 2nd edn. St Louis: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Javadpour MM, Tardiff JC, Ingwall JS. Mutation in the thin filament protein cTnT effects contractile function and energetics. Circulation. 2000;102:II98. [Google Scholar]

- Javadpour MM, Tardiff JC, Pinz I, Ingwall JS. Decreased energetics in murine hearts bearing the R92Q mutation in cardiac troponin T. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:768–775. doi: 10.1172/JCI15967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammermeier H. Microassay of free and total creatine from tissue extracts by combination of chromatography and fluorometric methods. Anal Biochem. 1973;56:341–345. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenz M, Sanbe A, Bouyer-Dalloz F, Gulick J, Klevitsky R, Hewett TE, Osinska HE, Lorenz JN, Brosseau C, Federico A, Alpert NR, Warshaw DM, Perryman MB, Helmke SM, Robbins J. Analysis of myosin heavy chain functionality in the heart. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17466–17474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JE, Myagmar BE, Swigart PM, Montgomery MD, Haynam S, Bigos M, Rodrigo MC, Simpson PC. β-Myosin heavy chain is induced by pressure overload in a minor subpopulation of smaller mouse cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2011;109:629–638. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosenbrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning EP, Tardiff JC, Schwartz SD. A model of calcium activation of the cardiac thin filament. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7405–7413. doi: 10.1021/bi200506k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maytum R, Geeves MA, Lehrer SS. A modulatory role for the troponin T tail domain in thin filament regulation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29774–29780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally EM, Buttrick PM, Leinwand LA. Ventricular myosin light chain 1 is developmentally regulated and does not change in hypertension. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2753–2767. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell TJ, Naber N, Franks-Skiba K, Dunn AR, Eldred CC, Berger CL, Malnasi-Csizmadia A, Spudich JA, Swank DM, Pate E, Cooke R. Nucleotide pocket thermodynamics measured by EPR reveal how energy partitioning relates myosin speed to efficiency. J Mol Biol. 2011;407:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice R, Guinto P, Dowell-Martino C, He H, Hoyer K, Krenz M, Robbins J, Ingwall JS, Tardiff JC. Cardiac myosin heavy chain isoform exchange alters the phenotype of cTnT-related cardiomyopathies in mouse hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:979–788. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saupe KW, Spindler M, Tian R, Ingwall JS. Impaired cardiac energetics in mice lacking muscle-specific isoenzymes of creatine kinase. Circ Res. 1998;82:898–907. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.8.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindler M, Saupe KW, Christe ME, Sweeney HL, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Ingwall JS. Diastolic dysfunction and altered energetics in the alphaMHC403/+ mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1775–1783. doi: 10.1172/JCI1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff JC. Thin filament mutations: developing an integrative approach to a complex disorder. Circ Res. 2011;108:765–782. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff JC, Hewett TE, Palmer BM, Olsson C, Factor SM, Moore RL, Robbins J, Leinwand LA. Cardiac troponin T mutations result in allele-specific phenotypes in a mouse model for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:469–481. doi: 10.1172/JCI6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian R, Halow JM, Meyer M, Dillmann WH, Figueredo VM, Ingwall JS, Camacho SA. Thermodynamic limitation for Ca2+ handling contributes to decreased contractile reserve in rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H2064–2071. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacman LS, Nihli M, Butters C, Heller M, Hatch V, Craig R, Lehman W, Homsher E. The troponin tail domain promotes a conformational state of the thin filament that suppresses myosin activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27636–27642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins H, McKenna WJ, Thierfelder L, Suk HJ, Anan R, O’Donoghue A, Spirito P, Matsumori A, Moravec CS, Seidman JG. Mutations in the genes for cardiac troponin T and alpha-tropomyosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1995a;332:1058–1064. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins H, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a genetic model of cardiac hypertrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1995b;4:1721–1727. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.