Abstract

Hypoxaemia elicits adrenergic suppression of fetal glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia. We postulate that this effect is mediated by catecholamines, exclusively, from fetal adrenal chromaffin cells. To investigate this hypothesis, square-wave hyperglycaemic clamp studies were performed under normoxaemic (26 ± 0.9 mmHg) and hypoxaemic (14 ± 0.3 mmHg) steady-state conditions in near-term fetal sheep that had undergone either surgical sham or bilateral adrenal demedullation (AD), values mentioned are ± SEM. Under normoxaemic conditions plasma noradrenaline concentrations were lower in AD fetuses than in sham-operated fetuses (457 ± 122 versus 1073 ± 103 pg ml−1, P < 0.05). Plasma insulin concentrations were not different at euglycaemia between shams (0.46 ± 0.07 ng ml−1) and AD fetuses (0.44 ± 0.04 ng ml−1) and increased (P < 0.05) with hyperglycaemia in both groups although to a lesser extent in AD fetuses (0.94 ± 0.19 ng ml−1) compared to shams (1.31 ± 0.15 ng ml−1; P < 0.05). Hypoxaemia increased plasma adrenaline (26-fold) and noradrenaline (5-fold) in shams but elicited no change in AD fetuses. Under hypoxaemic conditions, euglycaemic plasma insulin concentrations were reduced (P < 0.05) in both sham and AD fetuses to 0.30 ± 0.05 ng ml−1 and 0.27 ± 0.01 ng ml−1 respectively, and the insulin response to hyperglycaemia was abolished in shams but not affected in AD fetuses (0.33 ± 0.06 versus 0.73 ± 0.02 ng ml−1, P < 0.05). Hypoxaemia also induced hyperlactacaemia and hypocarbia to a greater extent in shams than in AD fetuses, indicating that catecholamines potentiate reductions in oxidative metabolism independently of insulin. These findings demonstrate that the fetal adrenal chromaffin cells are the source for acute hypoxaemia-induced elevations in fetal plasma catecholamines and suppression of glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia, but other factors reduce plasma insulin at euglycaemia.

Key points

Hypoxaemia was previously shown to lower fetal plasma insulin at euglycaemia and hyperglycaemia. Lowering insulin redistributes nutrients and spares glucose and oxygen.

Hypoxaemia also stimulates adrenal medullary secretion of adrenaline and noradrenaline, but the impact of adrenal catecholamines versus local noradrenaline secretion by sympathetic neurons has not been evaluated on insulin concentrations.

To determine the impact of adrenal medullary catecholamines on plasma insulin, we surgically demedullated the adrenal glands in fetal sheep and challenged them with acute hypoxaemia.

We found that fetal adrenal chromaffin cells were the source for hypoxia-induced increases in plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline.

Adrenal medullary catecholamines were essential for suppression of glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia but not for reduced basal insulin concentrations. They also contributed to fetal hyperlactacaemia and hypocarbia independently of their effects on insulin.

This study demonstrates that fetal hypoxaemia reduces basal and glucose-stimulated insulin concentrations, but by different mechanisms. Glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia is reduced by elevated plasma catecholamines secreted from the adrenal medulla, which helps to spare glucose and oxygen resources.

Introduction

Fetal hypoxaemia suppresses insulin secretion as a mechanism to conserve glucose and oxygen for essential functions. Studies using adrenergic antagonists have shown that the adrenergic system is a key mediator of hypoxaemic suppression of pancreatic β-cells (Sperling et al. 1980; Jackson et al. 1993, 2000; Leos et al. 2010). Chromaffin cells in the fetal adrenal gland are sensitive to blood oxygen concentrations and release noradrenaline and, to a lesser extent, adrenaline during fetal hypoxaemia (Cheung, 1990; Cohen et al. 1991; Adams et al. 1996). Previous studies suggest that sympathetic neurons such as the splanchnic nerve also contribute to elevations in plasma noradrenaline concentrations (Jones et al. 1987; Simonetta et al. 1996). Furthermore, direct sympathetic innervation of the pancreas by the splanchnic nerve was shown to produce an inhibitory tone on pancreatic β-cells under normal oxygen and glycaemic conditions (Lang et al. 1993), but whether the splanchnic nerve influences glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia or hypoxaemia-induced suppression of insulin has not been determined. We postulate that catecholamine secretion from adrenal chromaffin cells is the major intermediary for hypoxaemia-induced suppression of fetal insulin concentrations, as the sympathetic nervous system is not fully developed in the fetus (Pappano, 1977; Booth et al. 2011). To test this hypothesis, we surgically demedullated the adrenal glands of near-term fetal sheep and examined glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia responsiveness under normoxaemic and hypoxaemic steady-state conditions.

Methods

Ethical approval

Animal care and use was conducted with approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Arizona Agricultural Research Complex, Tucson, AZ, USA, which is accredited by the National Institutes of Health, the US Department of Agriculture, and the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Animals

Columbia–Rambouillet crossbred ewes (62 ± 3 kg) carrying singleton pregnancies were purchased from Nebeker Ranch (Lanscaster, CA, USA), values mentioned are ± SEM. Ewes had free access to water and were fed alfalfa pellets with a dry matter content of 19.5% crude protein, 32.6% acid detergent fibre, 42.6% neutral detergent fibre, 1.23 Mcal kg−1 net energy for maintenance, and 0.66 Mcal kg−1 net energy for reproductive processes (Dairy One Forage Testing Laboratory, Ithaca, NY, USA). Food intake was recorded daily. Ewes were fasted for 24 h prior to surgery.

Surgical preparation

At 120 ± 1.2 days of gestational age (dGA), indwelling polyvinyl catheters were surgically placed in the fetus as previously described (Limesand & Hay, 2003; Limesand et al. 2007), values mentioned are ± SEM. Fetal catheters for blood sampling were placed in the abdominal aorta by way of the hindlimb pedal arteries, and infusion catheters were placed in the femoral veins by way of the saphenous veins. All catheters were tunnelled subcutaneously to the ewe's flank, exteriorized through the skin, and housed in a plastic mesh pouch sutured to the skin.

Bilateral adrenal demedullation (n= 7) or sham-operative procedures (n= 6) were performed on the fetus. The adrenal glands were accessed by retroperitoneal incisions. To produce adrenal-demedullated (AD) fetuses, a straight electrode was used to cauterize the inner medullary tissue. In sham fetuses, the adrenal glands were accessed but not cauterized.

Catheters were placed in the trachea of each ewe as previously described (Gleed et al. 1986; Imamura et al. 2004). An incision was made through the skin eight rings below the larynx and a small fistula was made through the trachea. The leading end of the catheter was threaded through the fistula and the catheter was anchored to surrounding tissue, tunnelled subcutaneously to the back of the neck, and exteriorized. At surgery, ewes were administered procaine penicillin (600,000 U, i.m.; Vedco, St Joseph, MO, USA), and analgesic (phenylbutazone, 0.01 mg kg−1, i.v.; Vedco) was administered postoperatively for 72 h. Ewes were given a minimum of 4 days for recovery before in vivo studies were performed.

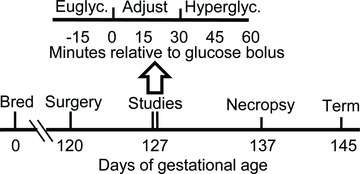

Study design

Two square-wave hyperglycaemic clamp studies were performed on each fetus at 127 ± 0.7 dGA (Fig. 1). The first was conducted under normal (resting) oxygen conditions. After a 4–12 h recovery period, a second hyperglycaemic clamp was performed after inducing steady-state fetal hypoxaemia by bleeding nitrogen gas through the maternal trachea catheter (∼6 l min−1). Fetal blood samples were taken every 2 min and the study began when fetal blood oxygen partial pressure was steadily between 11 and 14 mmHg for two consecutive samples, usually within 10 min of starting the nitrogen flow. Ewes were killed and fetal necropsy was performed at 137 ± 0.3 dGA. At necropsy, fetal adrenals were collected and fixed for histology.

Figure 1. Timeline of experimental procedures relative to gestational age.

The lower line illustrates the gestational ages at which fetal surgeries, in vivo physiological studies, and necropsies were performed. The upper line illustrates the timeline for in vivo square-wave hyperglycaemic clamp studies in minutes relative to the administration of glucose. Each study consisted of 3 sampling periods: euglycaemic steady-state period, glycaemic adjustment period, and hyperglycaemic steady-state period.

Square-wave hyperglycaemic clamps

Hyperglycaemic clamps were conducted as previously described (Green et al. 2012), with minor modifications. Four baseline samples were collected at 5 min intervals to determine plasma hormone concentrations and haematological parameters at euglycaemia. An intravenous glucose bolus (110 mg kg−1 estimated fetal weight) was then administered and a continuous glucose infusion was initiated. Infusion rates were adjusted to obtain steady-state fetal plasma glucose concentrations of ∼2.5 mm (Green et al. 2011), and four blood samples were collected in 5 min intervals beginning ≥30 min after glucose administration.

Whole blood was collected in EDTA-lined and heparin-lined syringes as previously described (Leos et al. 2010). Blood obtained with EDTA-lined syringes was centrifuged (13,000 g; 2 min; 4°C) and plasma was used to determine glucose, lactate and hormone concentrations. Blood obtained with heparin-lined syringes was used to determine blood gas and oximetry.

Biochemical analysis

Blood oxygen partial pressure, saturation and content, carbon dioxide partial pressure, pH, and hematocrit were measured in whole blood with an ABL 720 (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Values were corrected to 39.1°C, the average core body temperature of sheep. Plasma glucose and lactate concentrations were measured with a YSI model 2700 Select Biochemistry Analyser (Yellow Springs Instr., Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Plasma insulin concentrations were determined from duplicate 50 μl aliquots with a commercial ELISA kit (Ovine Insulin; ALPCO Diagnostics, Windham, NH, USA), and intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variance were less than 10%. Plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline concentrations were determined by ELISA (2-CAT; Rocky Mountain Diagnostics, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) from plasma samples containing 0.5 mm EDTA and 0.33 mm reduced glutathione, and intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variance were less than 15%. Limits of detection reported by the manufacturer are 5 and 25 pg ml−1 for adrenaline and noradrenaline, respectively.

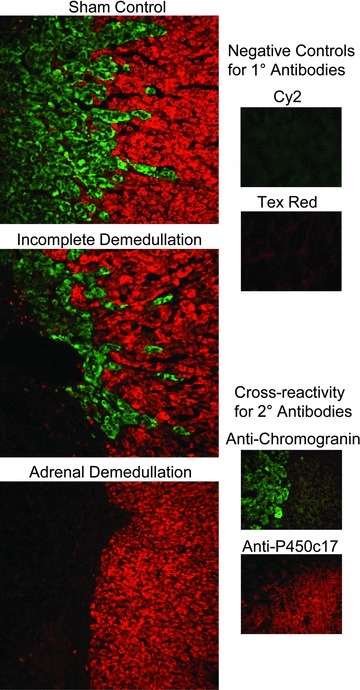

Adrenal gland immunofluorescence staining

Fetal adrenal glands were collected at necropsy and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h. Specimens were equilibrated in 30% sucrose and a 50:50 mixture of 30% sucrose and OTC Compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA, USA) for 24 h each, embedded in OTC, and stored at −80°C. Tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 10 μm as previously described (Limesand et al. 2005; Cole et al. 2009). Chromaffin cells were stained with mouse anti-chromogranin A (1:250; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) and immunocomplexes were detected with affinity-purified secondary antiserum conjugated to Cy2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). Zonas fasciculata and reticularis were stained with antiserum raised against bovine P450c17 (1:500, rabbit polyclonal; a gift from A. J. Conley, University of California, Davis; Peterson et al. 2001) and detected with affinity-purified secondary antiserum conjugated to Texas Red (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Fluorescence images were visualized on a Leica DM5500 microscope system and digitally captured with a Spot Pursuit 4 Megapixel CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI, USA).

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. Fetus was the experimental unit for all data analyses, which were performed on six shams and five AD fetuses (2 of the original 7 AD fetuses were omitted as described below). For insulin, insulin-to-glucose ratios, plasma lactate, blood pH and blood CO2, individual data analyses were performed for the euglycaemic period, the hyperglycaemic period, and the difference between hyperglycaemic and euglycaemic periods. For plasma lactate concentrations and blood pH, linear contrasts were also analysed across studies. Comparisons were made by ANOVA using the GLM procedure of SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data determined to be non-parametric by Levene's tests were reanalysed according to rank sums (plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline concentrations). Best-fit equations for lactate and pH were determined with the REG procedure of SAS, and rates of change (slopes) were compared by ANOVA (GLM).

Results

Confirmation of adrenal demedullation

Adrenal glands from all sham-operated fetuses stained positive for chromaffin cells, which were demarcated with antiserum against chromogranin A (Fig. 2). Small regions of chromaffin cells were present in adrenal glands of two AD fetuses and their physiological responses to hypoxaemia, measured by plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline concentrations, were consistent with incomplete adrenal demedullation. Therefore, these fetuses were excluded from the AD group. Glucocorticoid-producing cells (P450c17-positive) in the adrenal cortex were identified in all sham fetuses and were distinct from chromaffin cells. Adrenal cortex tissue was observed in only two AD fetuses. However, the physiological data presented below were indistinguishable between AD fetuses with and without P450c17-positive tissue.

Figure 2. Immunofluorescent staining for fetal adrenal cortical and chromaffin cells.

Adrenal glands were collected from adrenal-demedullated and sham-operated fetuses. Immunofluorescent staining was performed to identify chromaffin cells (Cy2; green fluorescence) with mouse anti-human chromogranin A and glucocorticoid-producing steroidogenic cells (Texas Red) with rabbit anti-bovine P450c17. Representative photomicrographs shown are from a sham-operated fetus, an incomplete adrenal-demedullated fetus, and a complete adrenal-demedullated fetus with an intact adrenal cortex. Antiserum controls shown are sham-operated adrenal glands immunostained without primary antibody (negatives) or stained with either primary antibody and both conjugated secondary antibodies (non-cross reacting secondary antibodies).

Fetal hypoxaemic and hyperglycaemic steady-state conditions

Adrenal demedullation had no effect on steady-state plasma glucose concentrations or blood oxygen partial pressures (Table 1). In all fetuses, hypoxaemic clamps reduced (P < 0.01) fetal blood oxygen partial pressures from 26 ± 0.9 mmHg at normoxaemia to 14 ± 0.3 mmHg. Oxygen saturation declined (P < 0.01) from 51 ± 1.8% to 17 ± 1.0% and blood oxygen content declined (P < 0.01) from 3.3 ± 0.1 mm to 1.2 ± 0.1 mm. Administration of glucose to the fetus produced hyperglycaemia; steady-state plasma glucose concentrations increased (P < 0.01) from 1.1 ± 0.4 mm at euglycaemia to 2.5 ± 0.9 mm.

Table 1.

Fetal plasma glucose and blood gas

| Normoxaemia | Hypoxaemia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euglycaemia | Hyperglycaemia | Euglycaemia | Hyperglycaemia | |||||

| Parameter | Sham | AD | Sham | AD | Sham | AD | Sham | AD |

| Plasma glucose (mm) | 1.1 ± 0.1a | 1.2 ± 0.1a | 2.6 ± 0.1b | 2.4 ± 0.1b | 1.1 ± 0.1a | 1.1 ± 0.1a | 2.8 ± 0.2b | 2.6 ± 0.2b |

| O2 partial pressure (mmHg) | 27 ± 2a | 23 ± 2a | 27 ± 2a | 23 ± 2a | 13 ± 1b | 13 ± 1b | 14 ± 1b | 13 ± 1b |

| O2 content (mm) | 3.5 ± 0.2a | 3.3 ± 0.2a | 3.1 ± 0.2a | 3.0 ± 0.2a | 1.1 ± 0.1b | 1.2 ± 0.1b | 1.0 ± 0.1b | 1.1 ± 0.1b |

| O2 saturation (%) | 52 ± 3a | 54 ± 3a | 49 ± 4a | 50 ± 3a | 16 ± 1b | 17 ± 1b | 14 ± 2b | 17 ± 2b |

| CO2 partial pressure (mmHg) | 49 ± 1a | 50 ± 2a | 50 ± 1a | 51 ± 2a | 42 ± 1b | 45 ± 1c | 38 ± 1d | 44 ± 2c |

Data are means ± SEM. Sham, intact (surgical sham-operated) fetuses. AD, adrenal-demedullated fetuses. a,b,c,dMeans within each row with different superscripts differ (P≤ 0.05).

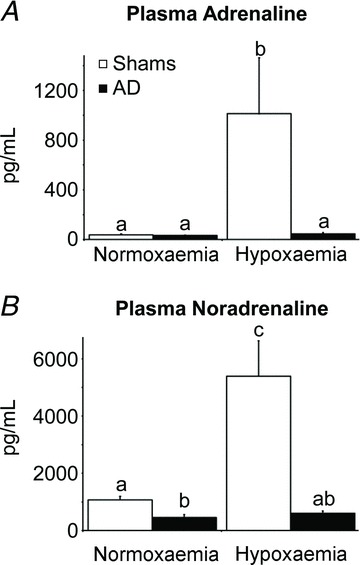

Plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline concentrations

During normoxaemia, plasma noradrenaline concentrations were lower (P= 0.01) in AD fetuses than in shams, but plasma adrenaline concentrations were very low and did not differ between shams and AD fetuses (Fig. 3). When sham fetuses were made hypoxaemic, plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline concentrations increased (P < 0.01) compared to concentrations under normoxaemic conditions, but when AD fetuses were made hypoxaemic, adrenaline and noradrenaline were not different compared to normoxaemic conditions. Plasma noradrenaline concentrations for the two incomplete AD fetuses were 538 and 476 pg ml−1 at normoxaemia and increased to 1368 and 791 pg ml−1, respectively, during hypoxaemia.

Figure 3. Fetal plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline concentrations.

Plasma adrenaline (A) and noradrenaline (B) concentrations during steady-state normoxaemia and hypoxaemia are shown for adrenal-demedullated (filled bars) and sham-operated (open bars) fetal sheep. Glycaemic conditions during the in vivo study did not influence plasma adrenaline or noradrenaline concentrations, and therefore concentrations were averaged across euglycaemic and hyperglycaemic periods for each oxygen condition. Means with differing superscripts differ (P≤ 0.05).

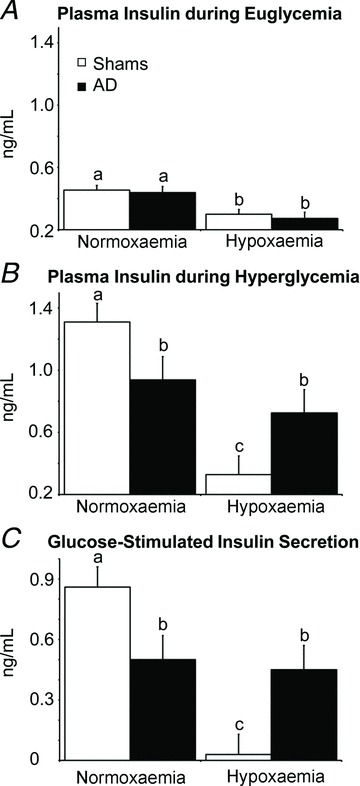

Plasma insulin concentrations

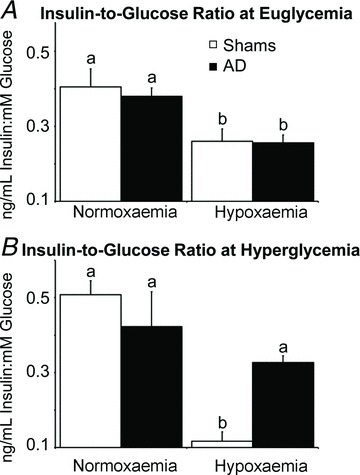

Under normoxaemic conditions, plasma insulin concentrations (Fig. 4) and plasma insulin-to-glucose ratios (Fig. 5) were not different between shams and AD fetuses at euglycaemia. When fetuses were made hyperglycaemic under normoxaemic conditions, plasma insulin concentrations increased (P < 0.01) in shams and AD fetuses, but maximal plasma insulin concentrations were greater (P≤ 0.04) in shams than AD fetuses. Hypoxaemia reduced (P < 0.01) plasma insulin and insulin-to-glucose ratios in shams and AD fetuses during euglycaemia. In shams, hypoxaemia also prevented the rise in plasma insulin in response to hyperglycaemia. In AD fetuses, however, plasma insulin increased (P < 0.01) in response to hyperglycaemia during hypoxaemia and reached concentrations similar to those reached under normoxaemic conditions. Glucose-stimulated insulin responsiveness, calculated as the difference in plasma insulin between hyperglycaemic and euglycaemic periods, was less (P= 0.05) in AD fetuses than in shams under normoxaemic conditions, but was maintained in AD fetuses and absent in shams under hypoxaemic conditions (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Fetal plasma insulin concentrations and β-cell responsiveness.

A and B, plasma insulin concentrations at euglycaemia (A) and hyperglycaemia (B) were measured during steady-state normoxaemia and hypoxaemia in adrenal-demedullated (filled bars) and sham-operated (open bars) fetal sheep. C, glucose-stimulate insulin secretion responsiveness, calculated as the difference in plasma insulin concentration between euglycaemic and hyperglycaemic steady-state periods within each oxygen condition. In each graph, means with differing superscripts differ (P≤ 0.05).

Figure 5. Ratio of fetal plasma insulin-to-glucose concentrations.

Plasma insulin-to-glucose ratios at euglycaemia (A) and hyperglycaemia (B) were determined during steady-state normoxaemia and hypoxaemia in adrenal-demedullated (filled bars) and sham-operated (open bars) fetal sheep. In each graph, means with differing superscripts differ (P≤ 0.05).

Plasma lactate concentrations, blood pH and blood CO2 partial pressure

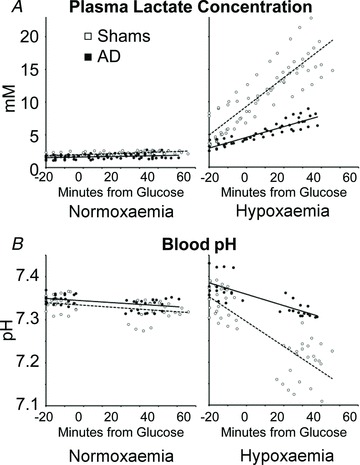

Under normoxaemic conditions, plasma lactate concentrations, blood pH and blood CO2 partial pressures were not different between euglycaemic and hyperglycaemic periods in shams or AD fetuses. In both groups, hypoxaemia increased (P < 0.05) plasma lactate in a linear fashion (Fig. 6) across the entire study, and the rates of accumulation (slope) were greater (P < 0.01) in shams than AD fetuses (Table 2). The rising lactate concentrations corresponded with a linear reduction (P < 0.01) in blood pH that was also at a greater rate (P= 0.01) in shams than in AD fetuses. Hypoxaemic conditions reduced (P≤ 0.01) blood CO2 partial pressures to a greater extent in shams than in AD fetuses at all periods (Table 1).

Figure 6. Fetal plasma lactate concentrations and blood pH.

Plasma lactate concentrations (A) during steady-state normoxaemia and hypoxaemia were determined in all blood samples collected from adrenal-demedullated (filled circles) and sham-operated (open circles) fetal sheep. Blood pH values (B) were determined only in samples collected during euglycaemic (−20 to 0 min) and hyperglycaemic (30–60 min) steady-state periods. During normoxaemia, the slopes for changes in lactate and pH were not different from zero. During hypoxaemia, best-fit prediction equations for plasma lactate were y= 0.2167x+ 7.97 (R2= 0.8) in shams and y= 0.847x+ 4.28 (R2= 0.9) in adrenal-demedullated fetuses, where y is lactate and x is time. Best-fit regression lines for pH were y=−0.0028x+ 7.313 (R2= 0.6) for shams and y=−0.0013x+ 7.364 (R2= 0.6) for adrenal-demedullated fetuses, where y is pH and x is time.

Table 2.

Rates of change in fetal lactacaemia and acidosis during acute hypoxaemia

| Euglycaemia | Hyperglycaemia | Entire Study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Sham | AD | Sham | AD | Sham | AD |

| Lactacaemia (mm min−1) | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.03* | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.03* | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.03* |

| Acidosis (pH min−1) | −0.0024 ± 0.0003 | −0.0007 ± 0.0003* | −0.0032 ± 0.0005 | −0.0014 ± 0.0006* | −0.0032 ± 0.0004 | −0.0013 ± 0.0005* |

Data are means ± SEM. Sham, intact (surgical sham-operated) fetuses. AD, adrenal-demedullated fetuses.

Mean for AD fetuses differed from mean for shams (P≤ 0.05).

Discussion

Hypoxaemia elevated plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline in intact but not adrenal-demedullated fetal sheep, which supports our hypothesis that adrenal chromaffin cells and not extra-adrenal tissues are responsible for hypoxaemia-induced hypercatecholaminaemia. Adrenal catecholamines were essential for inhibition of glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia but were not required for lowering plasma insulin during euglycaemia. Hypoxaemia caused a greater degree of hyperlactacaemia and hypocarbia in intact fetuses than in adrenal-demedullated fetuses with equivalent plasma insulin concentrations, which indicates that adrenal catecholamines have a direct impact on metabolism. Together, these findings show that circulating catecholamines from adrenal chromaffin cells regulate glucose metabolism by direct actions on non-islet tissues and by inhibiting glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia.

The fetal adrenal medulla increases plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline concentrations during hypoxaemia. In previous studies, adrenalectomy and adrenal demedullation by formalin injection abolished the hypoxaemia-induced rise in plasma adrenaline and reduced the noradrenaline response to one-tenth the magnitude observed in intact fetuses (Jones et al. 1987; Simonetta et al. 1996). The small noradrenaline response that occurred in adrenalectomized/demedullated fetuses was attributed by those authors to compensatory actions of extra-medullary chromaffin tissues, which were found to be larger in adrenal-demedullated fetuses. In the present study, adrenal demedullation by cautery completely abolished hypoxaemia-induced secretion of adrenaline and noradrenaline, and thus no extra-medullary sources contributed to hypercatecholaminaemia. Although we did not evaluate the size of extra-medullary chromaffin tissues, lower resting plasma noradrenaline in AD fetuses compared to shams demonstrates that non-medullary sources did not functionally compensate for adrenal demedullation. Furthermore, we challenged two AD fetuses with hypoxaemia at 134 dGA (2 weeks after surgery) and found no increase in plasma noradrenaline, identical to our observations at 127 dGA. Our histological evaluation also allowed us to identify two fetuses with small regions of unablated chromaffin cells (incomplete adrenal demedullation). These fetuses responded to hypoxaemia with small increases in plasma noradrenaline that were similar in magnitude (7–19% of intact fetuses) to the responses attributed to extra-medullary tissues in the previous studies (Jones et al. 1987; Simonetta et al. 1996). Histological verification of adrenal medullary ablation was not reported in the previous studies, and therefore it is likely that the observed noradrenaline responses were due to incomplete demedullation rather than extra-medullary sources.

Adrenaline and noradrenaline secreted by adrenal chromaffin cells prevented glucose from elevating plasma insulin concentrations during hypoxaemia. In AD fetuses, hyperglycaemic conditions increased plasma insulin even when fetuses were hypoxaemic, but in intact fetuses, hypoxaemia eliminated glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia. Therefore, ablation of the adrenal chromaffin cells rescued β-cell responsiveness to glucose from hypoxaemic suppression. Conversely, glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia was ∼30% lower in AD fetuses compared to shams under normoxaemic conditions. Previous findings in fetal sheep have shown that pancreatic islets express both α- and β-adrenergic receptor subtypes (Leos et al. 2010) and that blocking β-adrenergic activity reduces pancreatic responsiveness to glucose (Jackson et al. 2000). We speculate that lower resting plasma noradrenaline concentrations in our AD fetuses also reduced β-adrenergic potentiation of glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia by influencing other insulinotropic hormones, such as glucagon (Kawai et al. 1995).

Adrenal catecholamines were not responsible for the hypoxaemia-induced reduction of plasma insulin during euglycaemia. Hypoxaemia decreased euglycaemic plasma insulin concentrations ∼33% in both shams and AD fetuses, despite increasing plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline in shams only. Others have shown that α-adrenergic antagonists recover plasma insulin concentrations in hypoxaemic fetal sheep (Jackson et al. 1993; Jackson et al. 2000), but their findings did not distinguish between noradrenaline secreted from adrenal chromaffin cells or from sympathetic nerves. From our data, we can conclude that under euglycaemic conditions hypoxaemia lowers insulin concentrations independently of elevated plasma catecholamines, via direct sympathetic innervation or other unknown factors.

Plasma lactate accumulation, acidosis, and reduced blood CO2 partial pressure observed in the hypoxaemic fetus were greater in the presence of elevated plasma noradrenaline and adrenaline concentrations. The hypoxaemic fetus redistributes resources in order to preserve glucose and oxygen for essential organs such as the brain and heart (Boyle et al. 1992; Gardner et al. 2004). We previously postulated that fetuses compromised by placental insufficiency (chronic hypoxaemia) spare glucose and oxygen by reducing skeletal muscle glucose oxidative metabolism in favour of anaerobic glycolysis (Yates et al. 2011). In an earlier study, hypoxaemia increased lactate output from fetal hindlimb skeletal muscle, but the associated increase in plasma lactate plateaued within 4 h because of the onset of utilization by other organs (Boyle et al. 1990, 1992). Additionally, conditions associated with placental insufficiency have been shown to initiate gluconeogenesis in sheep fetuses (Limesand et al. 2007), and therefore lactate may be utilized as a substrate for hepatic glucose production. In the present study, the duration of hypoxaemia was acute and showed only a rise in plasma lactate concentrations. Nevertheless, these findings support our previous hypothesis for a shift to anaerobic glucose metabolism and also demonstrate that adrenal catecholamines contribute to fetal glucose and oxygen sparing in the hypoxaemic fetus. Moreover, we present evidence that catecholamines elicited metabolic effects independently of insulin. When fetuses were challenged with hypoxaemia under euglycaemic conditions, hyperlactacaemia and hypocarbia were worse in intact sham fetuses (hypercatecholaminemic) than in AD fetuses despite equivalent insulin, glucose and oxygen levels. From this finding, we postulate that catecholamines potentiate reductions in oxidative metabolism via direct effects on peripheral tissues that are distinct from their suppression of insulin concentrations.

It is noteworthy that the absence of glucocorticoid-producing cells in three of the five adrenal-demedullated fetuses did not impact our findings. Plasma cortisol is elevated in intact sheep fetuses compared to adrenalectomized fetuses in the final few days before birth, but does not differ between the two before 140 days of gestational age (Li et al. 2002; Fowden & Forhead, 2011). We did not measure cortisol in the present study, but these previous studies indicate that no differences would be found between shams and AD fetuses at this gestational age.

The results of this study demonstrate that fetal adrenal chromaffin cells are the source for elevated plasma catecholamines during acute fetal hypoxaemia. Furthermore, adrenal catecholamines and not catecholamines from other sources were responsible for inhibiting glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia. During euglycaemia, however, hypoxaemia reduced plasma insulin concentrations by factors other than adrenal catecholamines. Under normoxaemic conditions, glucose-stimulated hyperinsulinaemia was greater in fetuses with adrenal chromaffin cells, which indicates that these cells may have a beneficial effect on pancreatic β-cell maturation or responsiveness to glucose. Moreover, our observations indicate that elevated catecholamines increase hyperlactacaemia and hypocarbia independent of insulin. To our knowledge, this is the first study to confirm that the adrenal medulla is exclusively responsible for the elevated plasma catecholamine concentrations that inhibit pancreatic β-cell responsiveness to hyperglycaemia during a fetal hypoxaemic challenge, or to show evidence of an insulin-independent effect of fetal adrenal catecholamines on metabolic indices.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. This work was supported by Award No. R01 DK084842 (S.W.L., Principal Investigator) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. D.T.Y. and A.R.M. were supported by T32 HL7249. A.S.G. was supported by F32 DK088514. We thank Mandie M. Dunham for technical assistance. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- AD

adrenal-demedullated

- dGA

days of gestational age

Author contributions

The experiments were performed at The University of Arizona Agricultural Research Complex. D.T.Y. and S.W.L. designed the experiments and prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to data collection and interpretation and to critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Adams MB, Simonetta G, McMillen IC. The non-neurogenic catecholamine response of the fetal adrenal to hypoxia is dependent on activation of voltage sensitive Ca2+ channels. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;94:182–189. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth LC, Bennet L, Guild S-J, Barrett CJ, May CN, Gunn AJ, Malpas SC. Maturation-related changes in the pattern of renal sympathetic nerve activity from fetal life to adulthood. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:85–93. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.055236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle DW, Hirst K, Zerbe GO, Meschia G, Wilkening RB. Fetal hind limb oxygen consumption and blood flow during acute graded hypoxia. Pediatr Res. 1990;28:94–100. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199008000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle DW, Meschia G, Wilkening RB. Metabolic adaptation of fetal hindlimb to severe, nonlethal hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1992;263:R1130–R1135. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.5.R1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CY. Fetal adrenal medulla catecholamine response to hypoxia-direct and neural components. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1990;258:R1340–1346. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.6.R1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen WR, Piasecki GJ, Cohn HE, Susa JB, Jackson BT. Sympathoadrenal responses during hypoglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hypoxemia in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1991;261:E95–102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.1.E95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole L, Anderson M, Antin PB, Limesand SW. One process for pancreatic β-cell coalescence into islets involves an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Endocrinol. 2009;203:19–31. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden AL, Forhead AJ. Adrenal glands are essential for activation of glucogenesis during undernutrition in fetal sheep near term. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E94–E102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00205.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DS, Jamall E, Fletcher AJW, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. Adrenocortical responsiveness is blunted in twin relative to singleton ovine fetuses. J Physiol. 2004;557:1021–1032. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleed RD, Poore ER, Figueroa JP, Nathanielsz PW. Modification of maternal and fetal oxygenation with the use of tracheal gas infusion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:429–435. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90846-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AS, Chen X, Macko AR, Anderson MJ, Kelly AC, Hart NJ, Lynch RM, Limesand SW. Chronic pulsatile hyperglycemia reduces insulin secretion and increases accumulation of reactive oxygen species in fetal sheep islets. J Endocrinol. 2012;212:327–342. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AS, Macko AR, Rozance PJ, Yates DT, Chen X, Hay WW, Limesand SW. Characterization of glucose-insulin responsiveness and impact of fetal number and gender on insulin response in the sheep fetus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E817–823. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00572.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura T, Umezaki H, Kaushal KM, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia alters endocrine and physiologic responses to umbilical cord occlusion in the ovine fetus. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson BT, Cohn HE, Morrison SH, Baker RM, Piasecki GJ. Hypoxia-induced sympathetic inhibition of the fetal plasma insulin response to hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 1993;42:1621–1625. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson BT, Piasecki GJ, Cohn HE, Cohen WR. Control of fetal insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R2179–R2188. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CT, Roebuck MM, Walker DW, Lagercrantz H, Johnston BM. Cardiovascular, metabolic and endocrine effects of chemical sympathectomy and of adrenal demedullation in fetal sheep. J Dev Physiol. 1987;9:347–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Yokota C, Ohashi S, Watanabe Y, Yamashita K. Evidence that glucagon stimulates insulin secretion through its own receptor in rats. Diabetologia. 1995;38:274–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00400630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang U, Jensen A, Künzel W. Autonomic modulation of insulin levels in foetal sheep. Clin Auton Res. 1993;3:331–338. doi: 10.1007/BF01827335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leos RA, Anderson MJ, Chen X, Pugmire J, Anderson KA, Limesand SW. Chronic exposure to elevated norepinephrine suppresses insulin secretion in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E770–778. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00494.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Forhead AJ, Dauncey MJ, Gilmour RS, Fowden AL. Control of growth hormone receptor and insulin-like growth factor-I expression by cortisol in ovine fetal skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2002;541:581–589. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.016402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Hay WW., Jr Adaptation of ovine fetal pancreatic insulin secretion to chronic hypoglycaemia and euglycaemic correction. J Physiol. 2003;547:95–105. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Jensen J, Hutton J, Hay WW., Jr Diminished β-cell replication contributes to reduced β-cell mass in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1297–R1305. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00494.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Smith D, Hay WW., Jr Increased insulin sensitivity and maintenance of glucose utilization rates in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1716–1725. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00459.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappano AJ. Ontogenetic development of autonomic neuroeffector transmission and transmitter reactivity in embryonic and fetal hearts. Pharmacol Rev. 1977;29:3–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JK, Moran F, Conley AJ, Bird IM. Zonal expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in sheep and rhesus adrenal cortex. Endocrinology. 2001;142:5351–5363. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetta G, Young IR, McMillen IC. Plasma catecholamine and met-enkephalin-Arg6-Phe7 responses to hypoxaemia after adrenalectomy in the fetal sheep. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1996;60:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(96)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling MA, Christensen RA, Ganguli S, Anand R. Adrenergic modulation of pancreatic hormone secretion in utero: studies in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 1980;14:203–208. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198003000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates DT, Green AS, Limesand SW. Catecholamines mediate multiple fetal adaptations during placental insufficiency that contribute to intrauterine growth restriction: Lessons from hyperthermic sheep. J Pregnancy. 2011;2011:740408. doi: 10.1155/2011/740408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]