Abstract

Dextromethorphan is widely used in over-the-counter cough and cold medications. Its efficacy and safety for infants and young children remains to be clarified. The present study was designed to use the zebrafish as a model to investigate the potential toxicity of dextromethorphan during the embryonic and larval development. Three sets of zebrafish embryos/larvae were exposed to dextromethorphan at 24 hours post fertilization (hpf), 48 hpf, and 72 hpf, respectively, during the embryonic/larval development. Compared with the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets, the embryos/larvae in the 24 hpf exposure set showed much higher mortality rates which increased in a dose-dependent manner. Bradycardia and reduced blood flow were observed for the embryos/larvae treated with increasing concentrations of dextromethorphan. Morphological effects of dextromethorphan exposure, including yolk sac and cardiac edema, craniofacial malformation, lordosis, non-inflated swim bladder, and missing gill, were also more frequent and severe among zebrafish embryos/larvae exposed to dextromethorphan at 24 hpf. Whether the more frequent and severe developmental toxicity of dextromethorphan observed among the embryos/larvae in the 24 hpf exposure set, as compared with the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets, is due to the developmental expression of the Phase I and Phase II enzymes involved in the metabolism of dextromethorphan remains to be clarified. A reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis, nevertheless, revealed developmental stage-dependent expression of mRNAs encoding SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3, two enzymes previously shown to be capable of sulfating dextrorphan, an active metabolite of dextromethorphan.

Keywords: Dextromethorphan, developmental toxicity, cytosolic sulfotransferase, SULT, zebrafish

Introduction

Cough and cold medications are available in various formulas containing ingredients such as antihistamine (e.g., chlorpheniramine), decongestant (e.g., phenylephrine), cough suppressant (e.g., dextromethorphan), and antipyretic (e.g., acetaminophen), which are used singly or in combination. The efficacy and safety of pediatric cough and cold medications has been an issue of controversy in recent years. In 2007, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) opened an investigation on nonprescription cough and cold products (Dart et al., 2009). Later that year, a panel of FDA advisors concluded that nonprescription cold remedies may not be safe for young children (Dart et al., 2009). Indeed, multiple studies pointing to over-the-counter cold medications as the cause of infant deaths have been reported (CDC, 2007; Marinetti et al., 2005; Rimsza and Newberry, 2008). It is therefore important to verify the safety and delineate the proper use (with regard to dosing and infant/child age) of not only the currently available pediatric cough/cold drugs but also those in development.

Dextromethorphan is a widely used ingredient in cough and cold medications. At the currently recommended doses of 10 to 30 mg orally three to six times daily, dextromethorphan has been an effective antitussive agent for adults (Bem and Peck, 1992). For adults, adverse effects with recommended antitussive doses are rare. At excessively high doses, however, a number of side effects on the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., nausea and vomiting), the nervous system (e.g., drowsiness, dizziness, and blurred vision), as well as the cardiovascular system (e.g., changes in heart rate, blood pressure and body temperature) have been reported (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1997; Chyka et al., 2007; Woo, 2008; Dickerson et al., 2008). For infants and young children, the efficacy and safety of dextromethorphan remains to be clarified and this issue has received considerable publicity in recent years due to a number of dextromethorphan-related infant deaths (Marinetti et al., 2005; CDC, 2007; Wingert et al., 2007; Rimsza and Newberry, 2008). To gain insight into this latter issue, a useful animal model capable of reflecting the detrimental effects of the overdosing of dextromethorphan on developing infants/children is needed.

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has in recent years emerged as a popular vertebrate model in different areas of research (Alestrom et al., 2006; Beis and Stainier, 2006; Ingham, 2009). Compared with alternative mouse, rat, and other animal models, the zebrafish offers several important advantages including the small size, short generation time, availability of relatively large number of eggs laid at weekly intervals, rapid embryonic development (with all major organs formed within 2-4 days), and the transparency of the zebrafish embryo (Wixon, 2000). Despite the fact that there are morphological and physiological differences between the zebrafish and humans, the responses to chemicals that can cause endocrine disruption, reproductive toxicity, behavioral defects, teratogenesis, carcinogenesis, cardiotoxicity, ototoxicity, liver toxicity, etc., have been shown to be largely conserved (Brion, et al., 2004; Levin, et al., 2003; Murakami, et al., 2003; Parng, et al., 2002; Spitsbergen, et al., 2000; Veldman and Lin, 2008). An increasing number of studies have demonstrated that zebrafish embryos/larvae may serve as a convenient platform for pharmacological assessment and screening for potential adverse effects of drugs, particularly with regard to their effects during the developmental process (Busquet et al., 2008; David and Pancharatna, 2009; Gurvich et al., 2005; Hillegass et al., 2008; Menegola et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 1996).

We report in this communication a systematic study of the developmental toxicity of dextromethorphan in developing zebrafish embryos/larvae. Zebrafish embryos/larvae were exposed to different concentrations of dextromethorphan at different developmental stages in order to clarify any differences in sensitivity to the adverse effects of this drug during development. Mortality and hatching rates as well as morphological and functional changes in the developing zebrafish embryos/larvae attributed to the exposure to dextromethorphan were observed and analyzed. The expression of two enzymes, SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3, capable of sulfating dextrorphan, an active metabolite of dextromethorphan, was examined by RT-PCR.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Dextromethorphan and dextrorphan were products of Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Takara Ex Taq DNA polymerase was purchased from Fisher Scientific. Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by MWG Biotech. GeneRuler 100bp DNA Ladder Plus was from Fermentas Life Sciences. RNAqueous®-Micro Kit was a product of Applied Biosystems. All other chemicals were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Chicago, IL), and were of the analytical grade or the highest grades commercially available.

Preparation of Fertilized Zebrafish Eggs

Adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) were obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center at the University of Oregon (Eugene, OR; P40 RR012546 from NIH-NCRR). The fish were kept in fish tanks containing buffered water (pH 7.2) at 28°C, and were fed daily live brine shrimp naupli and Tetramin dried flake food (Tetra, Blacksburg, VA). The day:night cycle was maintained at 14 hours:10 hours, and spawning and fertilization was stimulated by the onset of first light. Marbles were used to cover the bottom of the spawning tank to protect newly laid eggs and facilitate their retrieval for study. Fertilized zebrafish embryos were collected from the bottom of the tank by siphoning with a disposable pipette. The eggs were placed in Petri dishes and washed thoroughly with buffered egg water (RO water containing 60 mg sea salt (Instant Ocean, Mentor, OH) per liter of water). Groups of 10 fertilized eggs were then placed in individual wells of 6-well plates and used in the following experiments. It should be noted that the fertilized zebrafish eggs used in these experiments were intact and not dechorionated.

Treatment of Zebrafish Eggs/Embryos/larvae with Dextromethorphan

For treatment with dextromethorphan, three sets of freshly prepared fertilized eggs were used. Each set included seven groups of 10 eggs placed in individual wells of 6-well plates. The dextromethorphan treatment for the three sets of fertilized eggs began at 24, 48, and 72 hours post fertilization (hpf), respectively. For the 24 hpf exposure set, eggs in individual wells were exposed to, respectively, 0.1 μM, 1 μM, 10 μM, 25 μM, 100 μM, 1 mM, and 2 mM of dextromethorphan at 24 hpf when the eggs had developed normally through blastula, gastrula and segmentation stages. For the 48 hpf and 72 hpf exposure sets, the eggs in individual wells were exposed to above-mentioned concentrations of dextromethorphan at 48 and 72 hpf, when the eggs had developed normally through the pharyngula stage and hatching period, respectively. An untreated control group of 10 fertilized eggs was examined in parallel. Observations for any adverse developmental effects due to treatment with dextromethorphan were made at 24, 30, 48 hpf and daily thereafter until 168 hpf. Mortality, hatching rates and morphological deformities of embryos/larvae were recorded and photographed. The heart rates in beats per min of larvae were recorded. Test drug solutions were renewed daily. Dead embryos/larvae were removed immediately once observed. The above-mentioned experiments were performed in triplicate.

Observation of Phenotypic Changes of Developing Zebrafish Embryos/larvae

An inverted microscope (ZEISS Axiovert 25 CFL) fitted with a Sony DSC-S75 digital/video camera was used to examine the developmental landmarks of control and dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish embryos/larvae. For embryos/larvae in the 24 hpf exposure set, observations started at 24 hpf (pharyngula period) and continued at 30, 48 hpf and then daily thereafter until 168 hpf. For the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets, observations started at 48 hpf and 72 hpf, respectively, and then daily thereafter until 168 hpf. Control and dextromethorphan-treated embryos/larvae were observed for spontaneous movements, presence of a heartbeat, head and tail differentiation, heart rate, occurrence of edema, gross malformations of the circulatory, muscular, and nervous systems, hatching rate, expression of pigmentation, blood flow, body orientation, swimming performance, and feeding success. Photographs were taken at each time point when observation was made.

Statistical Analysis

Data for embryonic mortality and heart rates are presented as mean ± S.D. based on results from three independent experiments. Student's t-test was employed for comparing heart rates of the dextromethorphan-treated embryos/larvae at each exposure concentration and control embryos/larvae at corresponding developmental stages, and significance level was kept at p <0.05.

Analysis of the Developmental Expression of SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3 in Untreated or Dextromethorphan-treated Zebrafish Eggs/Embryos/larvae

RT-PCR was employed to investigate the developmental expression of SULT3 ST1 and ST3. Total RNAs from groups of 10 untreated or dextromethorphan (50 μM)-treated zebrafish eggs/embryos/larvae at 24, 48, 72, 120, or 168 hpf were isolated using the RNAqueous-Micro Kit (Ambion), based on manufacturer's instructions. Aliquots containing 1 μg each of the total RNA preparations were used for the synthesis of the first-strand cDNA using the First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (GE Healthcare). One microliter aliquots of the 15 μl first-strand cDNA solutions prepared were used as templates for the subsequent PCR amplification. PCRs were carried out in 25 μl reaction mixtures using EX Taq DNA polymerase, in conjunction with gene-specific sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers (see Table 1). Amplification conditions were 2 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 35 s at 56°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The final reaction mixtures were applied onto a 0.9% agarose gel, separated by electrophoresis, visualized by ethidium bromide staining, and recorded using a UVP DigiDoc-It Imaging System. As a control, PCR amplification of the sequence encoding zebrafish β-actin was concomitantly performed using the above-mentioned first-strand cDNAs as templates, in conjunction with gene-specific sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) designed based on reported zebrafish β-actin nucleotide sequence (GenBank Accession No. AF057040).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for the RT-PCR analysis of the developmental expression of SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3 in dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish eggs/embryos/larvae.

| Target sequence | Sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers used | |

|---|---|---|

| SULT3 ST1 | Sense: | 5′-CGCGGATCCATGGAACGTGTTAACAATTATTTGTCTAAA-3′ |

| Antisense: | 5′-CGCGGATCCCTACTTCTGGTTTGTTTTGGTGTCTAAATC-3′ | |

| SULT3 ST3 | Sense: | 5′-CGCGGATCCATGATTAGTGACAAACTGTTGAAGTAC-3′ |

| Antisense: | 5′-CGCGGATCCTCAGCTACGCAGTTCTGTGATGTCCCA-3′ | |

| β-Actin | Sense: | 5′-ATGGATGAGGAAATCGCTGCCCTGGTC-3′ |

| Antisense: | 5′-TTAGAAGCACTTCCTGTGAACGATGGA-3′ |

The sense and antisense oligonucleotide primer sets listed were verified by BLAST Search to be specific for the zebrafish SULT3 ST1, SULT3 ST3, or β-actin nucleotide sequence.

Results

Three sets of zebrafish embryos/larvae were exposed to dextromethorphan at distinct time points (24 hpf, 48 hpf, and 72 hpf) during the embryonic/larval development. Thereafter, observations for morphological and functional changes attributed to the dextromethorphan exposure were made at designated time points until 168 hpf. It is to be noted that the changes described below for embryos/larvae in each of the three (24, 48, and 72 hpf) sets refer to those observed at the particular stages during the embryonic/larval development, irrespective of the time when dextromethorphan exposure started.

Mortality Rate and Hatching Success

Embryonic mortality rate was 0% among embryos/larvae in the control group. In the 24 hpf exposure set, the embryos/larvae exposed to 1 mM and 2 mM of dextromethorphan showed mortality rates of 46.7% and 96.7% at 96 hpf. The embryos/larvae exposed to the same concentrations of dextromethorphan in the 48 hpf sets showed 0% and 6.7% mortality rates at the same developmental stage (96 hpf), and similar rates were found for the embryos/larvae in the 72 hpf sets. All embryos treated with 1 or 2 mM dextromethorphan in the 24 hpf exposure set died at 120 hpf. Surprisingly, the mortality rates for 2 mM dextromethorphan-treated larvae in the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets also increased to 100% at 120 hpf, although most of them were still alive at 96 hpf. For the larvae in 1 mM dextromethorphan-exposed groups in these two latter set, the mortality rate remained 0% at 120 hpf, but increased to 100% at 144 hpf. In the 0.1 mM dextromethorphan-treated group of the 24 hpf exposure set, there were no dead embryos/larvae until 96 hpf, and at 144 hpf the mortality rate reached 33%, while in the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets, the mortality rate remained 0% at 144 hpf time point. At 168 hpf, the mortality rates increased to 63.3%, 60% and 53.3%, respectively, for the 0.1 mM dextromethorphan-treated group of the 24, 48 and 72 hpf exposure set. Groups exposed to 0.1 μM, 1 μM, 10 μM, and 25 μM of dextromethorphan in all three sets survived until 168 hpf. The hatching rates among surviving embryos exposed to different concentrations of dextromethorphan in each of the three sets showed no significant differences.

Gross Morphological and Behavioral Effects

Developmental toxicity was not observed until 48 hpf for the 24 hpf exposure set, when the hatched embryos had completed most of their morphogenesis. For the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets, the toxicity manifested 24 hours after the dextromethorphan treatment started. The hallmark signs of dextromethorphan developmental toxicity in zebrafish larvae were missing/reduced upper jaw, bradycardia, and edema in cardiac sac, lordosis, non-inflated swim bladder, missing gill, and malformed forehead. The incidence of developmental malformations was much higher for the 24 hpf exposure set than for the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets. For the zebrafish larvae exposed to the lowest concentration (0.1 μM) of dextromethorphan, malformations were detected in the 24 hpf exposure set, but not in the 48 or 72 hpf exposure set. The onset times for the aforementioned malformations/abnormalities are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Endpoints of dextromethorphan developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos/larvae.

| End Point (Structure/Function) | Toxicity Response | Time of Onset (hpf) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hpf Set | 48 hpf Set | 72 hpf Set | |||

| Osmoregulation | Pericardial sac | Edema | 72 | 96 | 96 |

| Yolk sac | Edema | 72 | 96 | 96 | |

| Heart | Cardiac rhythm | Disrupted | 48 | 72 | 96 |

| Heart rate | Reduced | 48 | 72 | 96 | |

| Cartilage | Lower jaw | Reduced in size | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Upper jaw | Reduced in size | ||||

| Swim bladder | Inflation | Blocked | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Tail | Shape | Bent | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| Whole Embryo/larva | Survival rate | Decreased | 24 | 96 | 96 |

| Growth | Reduced | 48 | 96 | 96 | |

| Behavior | Movement | Stationary | 72 | 96 | 96 |

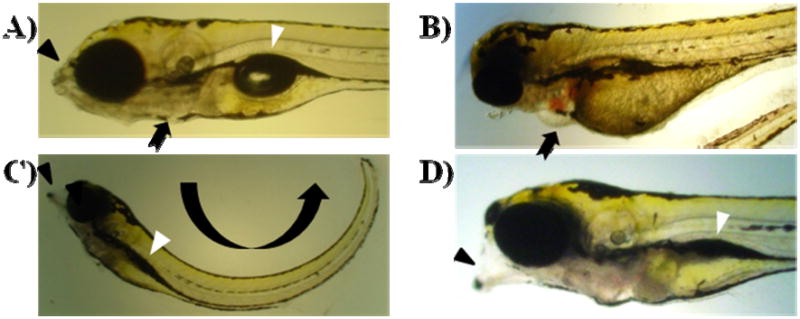

Yolk Sac and Cardiac Edema

The incidence of yolk sac or cardiac edema was 0% among embryos/larvae in the control group at any of the time points examined (Figure 1A). In the 24 hpf exposure set, all embryos/larvae treated with 1 and 2 mM of dextromethorphan started developing edema in the cardiac sac and yolk sac at 72 hpf, which became more extensive at 96 hpf (Figure 1B). Embryos/larvae treated with the same concentrations of dextromethorphan in the other two (48 and 72 hpf) sets started developing edema at 96 hpf (24 hours later than embryos/larvae in the 24 hpf exposure set). For embryos/larvae exposed to lower concentrations of dextromethorphan in all three sets, the incidences of yolk sac and cardiac edema were low.

Figure 1.

Effects of exposure to dextromethorphan on developing zebrafish larvae. A) Untreated control larva at 168 hpf. B) 2 mM dextromethorphan-exposed larva in the 24 hpf exposure set. At the 96 hpf time point, the larva exhibited edema in the cardiac sac (as indicated by an arrow). C) 25 μM dextromethorphan-exposed larva in the 24 hpf exposure set. At 168 hpf, the larva exhibited lordosis (curving body trunk; indicated by a curved arrow), malformed mouth/jaw (indicated by a black arrowhead) and non-inflated swim bladder (indicated by a white arrowhead). D) 0.1 μM dextromethorphan-exposed larva in the 24 hpf exposure set. At 168 hpf, similar morphological abnormalities as those found in C) were observed. In contrast, these morphological abnormalities were not manifested by 0.1 μM dextromethorphan-exposed larvae in the 48 hpf and 72 hpf exposure sets at the same time point (168 hpf).

Craniofacial Malformation

Reduced mouth and jaw malformation was initially observed in dextromethorphan-exposed zebrafish larvae at 120 hpf in all three sets. These larvae had reduced upper jaw which might have prevented them from swallowing food. Craniofacial abnormalities were not detected for zebrafish larvae in the control group. The incidence of craniofacial abnormalities was prominent among zebrafish larvae exposed to 1 μM, 25 μM, and 0.1 mM dextromethorphan at 168 hpf for all three sets. Approximately 33.3%, 93.3% and 100% of the larvae exposed to, respectively, 1 μM, 25 μM, and 0.1 mM dextromethorphan were found to exhibit shorter, malformed, or undeveloped jaws and lordosis (Figure 1C). For the 0.1 μM dextromethorphan-treated group of the 24 hpf exposure set, 23.3% of the developed larvae showed craniofacial malformation at 168 hpf (Figure 1D), which, however, was not found for larvae in the 0.1 μM dextromethorphan-treated group in the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets (figures not shown).

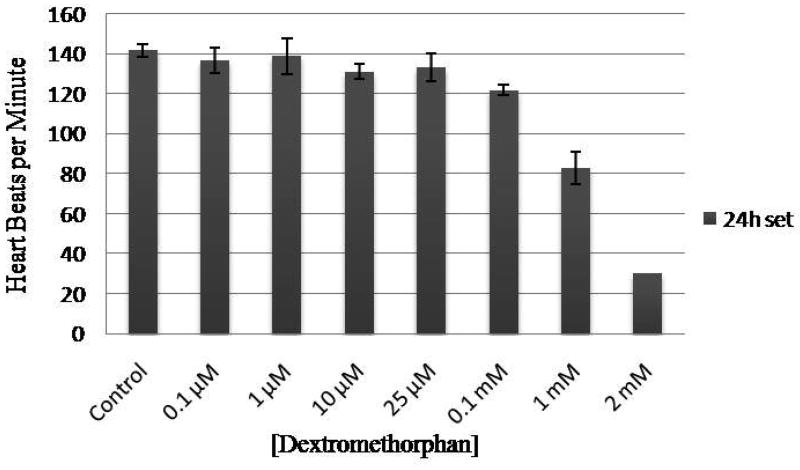

Blood Flow and Heart Rate

Dextromethorphan exerted developmental toxicity on the cardiovascular system of the zebrafish larvae by causing reduced blood flow and bradycardia. Heart rates of the dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish larvae decreased with increasing concentrations of dextromethorphan. In the 24 hpf exposure set, the heart rate, at 96 hpf, showed a significance decrease for zebrafish larvae treated with 10 μM dextromethorphan, and was proportionately slower for zebrafish larvae treated with increasing concentrations of dextromethorphan (Figure 2). Similar phenomenon was observed for larvae in the 48 and 72 hpf exposure sets (data not shown). Blood flow of the larvae in these two latter sets appeared almost stopped by 144 hpf, although the heart was still beating.

Figure 2.

Heart rates of zebrafish larvae exposed to different concentrations of dextromethorphan. The data shown were obtained at 96 hpf from the larvae in the 24 hpf exposure set. Heart rate was measured in beats per minute.

Feeding and Behavior

Feeding was observed for larvae in the control group at 96 hpf, whereas all dextromethorphan-treated larvae with malformed mouths/jaws were unable to feed properly at this time due to malformed mouths/jaws. Lack of feeding might have contributed to their death. All larvae in the control group developed an inflated swim bladder at 120 hpf, whereas 50%, 33.3%, and 33.3%, respectively, of the larvae in 0.1 μM dextromethorphan-treated group in the three sets showed no or poorly inflated swim bladder. Only 6.7%, 16.7%, and 16.7% of the larvae treated with 1 μM dextromethorphan in the three sets developed inflated swim bladders. None of the zebrafish larvae in the three sets treated with dextromethorphan higher than 1 μM concentration developed an inflated swim bladder. Possibly due to the lack of inflated swim bladder and the bent tail, the larvae tended to lie still on their sides instead of swim actively. Larvae in the control group were alert to tapping on the bottom of the culture plate and showed avoidance behavior instantly, while the dextromethorphan-treated ones showed slow or no responses.

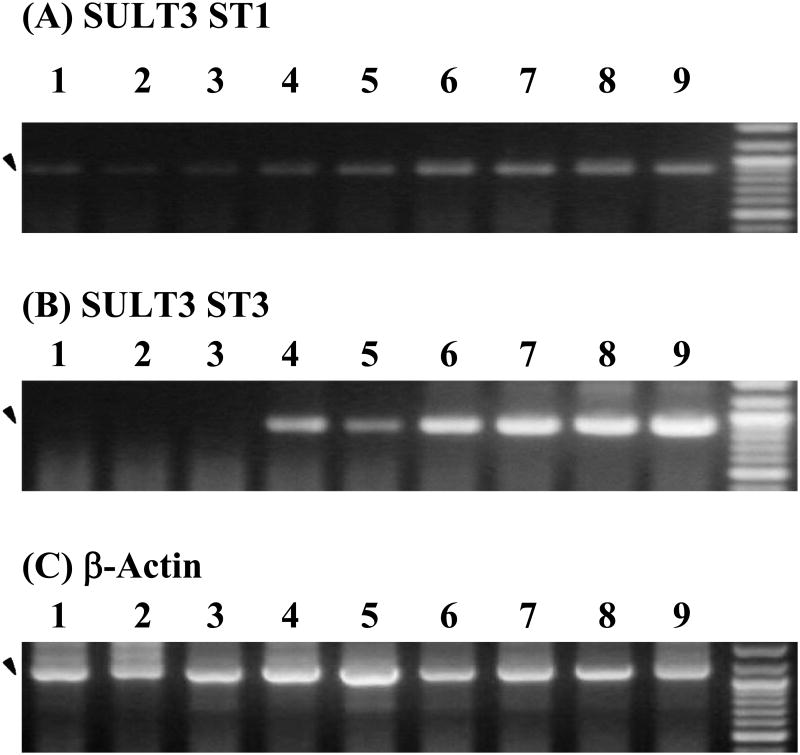

Developmental Expression of SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3 in Zebrafish Eggs/Embryos/larvae Treated with Dextromethorphan

The expression of mRNAs encoding SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3, two zebrafish SULT enzymes previously shown to be capable of sulfating a dextromethorphan metabolite, dextrorphan, was examined using RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 3A, a low but significant level of the coding mRNA of SULT3 ST1 was detected in the control 24 hpf embryo, which remained low at 48 hpf (the hatching period) and increased to a higher level from 72 hpf through 168 hpf. For SULT3 ST3, no coding mRNA was detected until 72 hpf, which then increased to a high level through 168 hpf (Figure 3B). For both SULT3 ST1 and ST3, no significant differences in the level of expression were observed between untreated embryos/larvae and embryos/larvae treated with 50 μM dextromethorphan. In contrast to the developmental stage-dependent expression of SULT3 ST1 and ST3, mRNA encoding β-actin, a housekeeping protein, was found to be consistently expressed at all developmental stages examined and irrespective of the exposure to dextromethorphan (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Developmental expression of the zebrafish SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3 in untreated and dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish embryos/larvae. RT-PCR was employed to analyze the expression of mRNAs encoding (A) SULT3 ST1, (B) SULT3 ST3, and (C) β-actin, respectively, in untreated and 50 μM dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish embryos/larvae. Final PCR mixtures were subjected to 0.9% agarose electrophoresis. Samples analyzed correspond to 24 hpf untreated zebrafish embryos (lane 1), 48 hpf untreated and dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish embryos (lanes 2 and 3), 72 hpf untreated and dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish larvae (lanes 4 and 5), 120 hpf untreated and dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish larvae (lanes 6 and 7), and 168 hpf untreated and dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish larvae (lanes 8 and 9). The PCR products corresponding to the zebrafish SULT3 ST1, SULT3 ST3, or β-actin, as visualized by ethidium bromide staining, are marked by arrowheads. DNA size markers co-electrophoresed are shown on the right for each of the three panels. The two bright bands are those of the 1,000 bp and 500 bp DNA markers.

Discussion

The zebrafish is gaining popularity as a valuable model organism for biomedical research (Alestrom et al., 2006; Beis et al., 2006; Ingham, 2009; Wixon, 2000). A particularly attractive feature of the zebrafish for pharmacological/toxicological investigations is its potential use in a high-throughput manner for screening the effects of drugs that may reflect those found in humans. For example, an earlier study showed that, of the 23 tested drugs that are known to cause QT prolongation in humans, 22 of them consistently result in bradycardia and AV block in the zebrafish (Milan et al., 2003).

The present study was designed to test the developmental toxicity of dextromethorphan, a commonly used cough suppressant, on developing zebrafish embryos/larvae. Due to insufficient information concerning the mechanisms of drug uptake by zebrafish embryo/larva and that the chorion surrounding the zebrafish embryo may pose as a permeability barrier, a wide range of concentrations, spanning 0.1 μM - 2 mM, of dextromethorphan was tested. It is to be noted that previous studies analyzing blood concentration of dextromethorphan in infants suspected to have died from dextromethorphan overdosing ranged from 390 μg/L (CDC, 2007) to 40 mg/L (Wingert et al., 2007), which are equivalent to 1.4 μM to 147 μM. The concentration range of dextromethorphan tested in the present study therefore appeared to encompass these latter concentrations. Results from the present study indicated that the dextromethorphan toxicity manifested at different stages during zebrafish embryonic/larval development in a dose-dependent manner, affecting/altering growth and survival, blood flow, heart rate, formation of mouth/jaw and swim bladder, and behavior. Significantly, in the 24 hpf exposure set, the heart rate, at 96 hpf, showed a significance decrease for zebrafish larvae treated with 10 μM dextromethorphan, and was proportionately slower for zebrafish larvae treated with higher concentrations of dextromethorphan. The bradycardia and the resulting reduced rate of blood flow were likely a main cause of the eventual death of some of the dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish larvae. The malformation of mouth/jaw, which prevented the larvae from normal feeding, might have also contributed to the death of those larvae. Previous studies indicated that the reduced blood flow to the head area may contribute to the craniofacial malformations in zebrafish larvae that had developed beyond 96 hpf (Teraoka et al., 2002). It is therefore possible that the malformation of mouth/jaw, and perhaps other morphological/structural abnormalities as well, of dextromethorphan-treated zebrafish larvae may be a secondary effect due to bradycardia and the resulting reduced blood flow. Whether and how the cardiotoxicity and other adverse effects of dextromethorphan observed in developing zebrafish larvae may have relevance to dextromethorphan-administered infants or young children (Boland et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2009; Chyka et al., 2007; Dart et al., 2009), however, remains to be clarified.

An intriguing finding is that embryos/larvae exposed to dextromethorphan at 24 hpf showed more frequent and severe morphological and functional abnormalities than embryos/larvae exposed to dextromethorphan at 48 or 72 hpf. While it remains to be verified whether developmental growth tissue complexity may hinder the exposure levels and contribute to decreased sensitivity of the older larvae, one possibility, nevertheless, may lie in the differential constituents of the drug-metabolizing or detoxifying enzymes that are expressed at different stages during the embryonic/larval development. Several drug-metabolizing enzymes have been reported to be involved in the metabolism and detoxification of dextromethorphan. Under normal circumstances, dextromethorphan undergoes a first-pass metabolism and becomes O-demethylated to dextrophan by CYP2D6 and N-demethylated to 3-methoxymorphinan by CYP3A4. Dextrophan and 3-methoxymorphinan can be secondarily N- or O-didemethylated to produce 3-hydroxymorphinan (Jacqz-Aigrain et al., 1993; Kerry et al., 1994; Van et al., 2009). These metabolites can be further subjected to Phase II sulfation or glucuronidation (Kupfer et al., 1986). Whether the developing fetus and neonate are equipped with the Phase I and Phase II enzymes involved in the metabolism and detoxification of dextromethorphan, however, remains unclear. Previous studies indicated that among the drug-metabolizing enzymes, the different cytochrome P450 isozymes of the Phase I oxidative stage may be expressed at different levels at various times during development, with some being expressed early on during embryogenesis and either decreasing or remaining constant later in gestation, while others are expressed only later in gestation or postnatally (Hakkola et al., 1998; Hines, 2007; Hines, 2008; Oesterheld, 1998). There is less information about the ontogeny of the Phase II enzymes (Barker et al., 1994; Darras et al., 1999; Duanmu et al., 2006; Hines, 2008; McCarver and Hines, 2002; Richard et al., 2001). In some human studies, sulfation by the SULTs appears to be more important in fetal development, both for the homeostasis of key endogenous compounds (Barker et al., 1994; Darras et al., 1999; Duanmu et al., 2006; Richard et al., 2001), as well as for detoxification of xenobiotics including drugs, especially since other conjugating enzyme systems, such as the uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucuronosyltransferases, are not expressed at significant levels until the neonatal period (Richard et al., 2001). It therefore appears to be an important issue whether the more frequent and severe morphological and functional abnormalities observed with the zebrafish embryos/larvae exposed to dextromethorphan at 24 hpf, compared with those exposed to dextromethorphan at 48 or 72 hpf, might have been due to the developmental stage-dependent expression of SULT(s) that are involved in the metabolism of dextromethorphan. In a separate study, we have demonstrated that two zebrafish SULTs (designated SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3) indeed were capable of catalyzing the sulfation of dextrorphan, a key metabolite of dextromethorphan (Liu et al., unpublished data). An RT-PCR analysis showed that the expression of the mRNA encoding SULT3 ST1, although at a relatively low level, started at 24 hpf, whereas the expression of the mRNA encoding SULT3 ST3 did not occur until 72 hpf. For both SULT3 ST1 and SULT3 ST3, the developmental expression appeared not significantly affected upon exposure to dextromethorphan. It will be important to clarify whether and how the developmental expression of these dextrorphan-sulfating SULTs may correlate with the sensitivity to the adverse effects of dextromethorphan during the development of zebrafish embryos/larvae.

In conclusion, we report in this communication a first study on the developmental toxicity of dextromethorphan using the zebrafish as a model. In addition to elevated mortality rates, the dextromethorphan-exposed zebrafish embryos/larvae were observed to exhibit bradycardia and reduced blood flow as well as a number of morphological abnormalities including yolk sac and cardiac edema, craniofacial malformation, lordosis, non-inflated swim bladder, poorly developed and missing gill arches. It remains to be clarified whether and how these adverse effects, particularly bradycardia and reduced blood flow, may correlate with those that may occur in developing human fetus/neonate/child upon exposure to or treatment with elevated levels of dextromethorphan.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant GM085756 and a startup fund from College of Pharmacy, The University of Toledo.

Abbreviations

- hpf

hours post fertilization

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- SULT

cytosolic sulfotransferase

References

- Alestrom P, Holter JL, Nourizadeh-Lillabadi R. Zebrafish in functional genomics and aquatic biomedicine. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Use of codeine- and dextromethorphan-containing cough remedies in children. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics. 1997;99:918–920. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.6.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker EV, Hume R, Hallas A, Coughtrie WH. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase in the developing human fetus: quantitative biochemical and immunological characterization of the hepatic, renal, and adrenal enzymes. Endocrinology. 1994;134:982–989. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.2.8299591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beis D, Stainier DY. In vivo cell biology: following the zebrafish trend. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem JL, Peck R. Dextromethorphan. An overview of safety issues. Drug Saf. 1992;7:190–199. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199207030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland DM, Rein J, Lew EO, Hearn WL. Fatal cold medication intoxication in an infant. J Anal Toxicol. 2003;27:523–526. doi: 10.1093/jat/27.7.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busquet F, Nagel R, von Landenberg F, Mueller SO, Huebler N, Broschard TH. Development of a new screening assay to identify proteratogenic substances using zebrafish danio rerio embryo combined with an exogenous mammalian metabolic activation system (mDarT) Toxicol Sci. 2008;104:177–188. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007. Infant deaths associated with cough and cold medications--two states. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 2005;56:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, Sachs HC, Lee CE. Unexpected infant deaths associated with use of cough and cold medications. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e358–359. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyka PA, Erdman AR, Manoguerra AS, Christianson G, Booze LL, Nelson LS, Woolf AD, Cobaugh DJ, Caravati EM, Scharman EJ, et al. Dextromethorphan poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45:662–677. doi: 10.1080/15563650701606443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darras VM, Hume R, Visser TJ. Regulation of thyroid hormone metabolism during fetal development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;151:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart RC, Paul IM, Bond GR, Winston DC, Manoguerra AS, Palmer RB, Kauffman RE, Banner W, Green JL, Rumack BH. Pediatric fatalities associated with over the counter (nonprescription) cough and cold medications. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A, Pancharatna K. Effects of acetaminophen (paracetamol) in the embryonic development of zebrafish, Danio rerio. J Appl Toxicol. 2009;29:597–602. doi: 10.1002/jat.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson DL, Schaepper MA, Peterson MD, Ashworth MD. Coricidin HBP abuse: patient characteristics and psychiatric manifestations as recorded in an inpatient psychiatric unit. J Addict Dis. 2008;27:25–32. doi: 10.1300/J069v27n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duanmu Z, Weckle A, Koukouritaki SB, Hines RN, Falany JL, Falany CN, Kocarek TA, Runge-Morris M. Developmental expression of aryl, estrogen, and hydroxysteroid sulfotransferases in pre- and postnatal human liver. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1310–1317. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurvich N, Berman MG, Wittner BS, Gentleman RC, Klein PS, Green JB. Association of valproate-induced teratogenesis with histone deacetylase inhibition in vivo. FASEB J. 2005;19:1166–1168. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3425fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkola J, Tanaka E, Pelkonen O. Developmental expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes in human liver. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;82:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1998.tb01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillegass JM, Villano CM, Cooper KR, White LA. Glucocorticoids alter craniofacial development and increase expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio) Toxicol Sci. 2008;102:413–424. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines RN. Ontogeny of human hepatic cytochromes P450. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2007;21:169–175. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines RN. The ontogeny of drug metabolism enzymes and implications for adverse drug events. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118:250–267. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham PW. The power of the zebrafish for disease analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R107–112. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacqz-Aigrain E, Funck-Brentano C, Cresteil T. CYP2D6- and CYP3A-dependent metabolism of dextromethorphan in humans. Pharmacogenetics. 1993;3:197–204. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer A, Schmid B, Pfaff G. Pharmacogenetics of dextromethorphan O-demethylation in man. Xenobiotica. 1986;16:421–433. doi: 10.3109/00498258609050249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerry NL, Somogyi AA, Bochner F, Mikus G. The role of CYP2D6 in primary and secondary oxidative metabolism of dextromethorphan: in vitro studies using human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;38:243–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04348.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinetti L, Lehman L, Casto B, Harshbarger K, Kubiczek P, Davis J. Over-the-counter cold medications-postmortem findings in infants and the relationship to cause of death. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29:738–743. doi: 10.1093/jat/29.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarver DG, Hines RN. The ontogeny of human drug-metabolizing enzymes: phase II conjugation enzymes and regulatory mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:361–366. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menegola E, Di Renzo F, Broccia ML, Giavini E. Inhibition of histone deacetylase as a new mechanism of teratogenesis. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2006;78:345–353. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan DJ, Peterson TA, Ruskin JN, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Drugs that induce repolarization abnormalities cause bradycardia in zebrafish. Circulation. 2003;107:1355–1358. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061912.88753.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterheld JR. A review of developmental aspects of cytochrome P450. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1998;8:161–174. doi: 10.1089/cap.1998.8.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard K, Hume R, Kaptein E, Stanley EL, Visser TJ, Coughtrie MW. Sulfation of thyroid hormone and dopamine during human development: ontogeny of phenol sulfotransferases and arylsulfatase in liver, lung, and brain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2734–2742. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimsza ME, Newberry S. Unexpected infant deaths associated with use of cough and cold medications. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e318–322. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teraoka H, Dong W, Ogawa S, Tsukiyama S, Okuhara Y, Niiyama M, Ueno N, Peterson RE, Hiraga T. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin toxicity in the zebrafish embryo: altered regional blood flow and impaired lower jaw development. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:192–199. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van LM, Sarda S, Hargreaves JA, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Metabolism of dextrorphan by CYP2D6 in different recombinantly expressed systems and its implications for the in vitro assessment of dextromethorphan metabolism. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:763–771. doi: 10.1002/jps.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingert WE, Mundy LA, Collins GL, Chmara ES. Possible role of pseudoephedrine and other over-the-counter cold medications in the deaths of very young children. J Forensic Sci. 2007;52:487–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wixon J. Featured organism: Danio rerio, the zebrafish. Yeast. 2000;17:225–231. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000930)17:3<225::AID-YEA34>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo T. Pharmacology of cough and cold medicines. J Pediatr Health Care. 2008;22:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Balmer JE, Lovlie A, Fromm SH, Blomhoff R. Specific teratogenic effects of different retinoic acid isomers and analogs in the developing anterior central nervous system of zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1996;206:73–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199605)206:1<73::AID-AJA7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]