Abstract

Many plants accumulate high levels of free proline (Pro) in response to osmotic stress. This imino acid is widely believed to function as a protector or stabilizer of enzymes or membrane structures that are sensitive to dehydration or ionically induced damage. The present study provides evidence that the synthesis of Pro may have an additional effect. We found that intermediates in Pro biosynthesis and catabolism such as glutamine and Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid (P5C) can increase the expression of several osmotically regulated genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.), including salT and dhn4. One millimolar P5C or its analog, 3,4-dehydroproline, produced a greater effect on gene expression than 1 mm l-Pro or 75 mm NaCl. These chemicals did not induce hsp70, S-adenosylmethionine synthetase, or another osmotically induced gene, Em, to any significant extent. Unlike NaCl, gene induction by P5C did not depend on the normal levels of either de novo protein synthesis or respiration, and did not raise abscisic acid levels significantly. P5C- and 3,4-dehydroproline-treated plants consumed less O2, had reduced NADPH levels, had increased NADH levels, and accumulated many osmolytes associated with osmotically stressed rice. These experiments indicate that osmotically induced increases in the concentrations of one or more intermediates in Pro metabolism could be influencing some of the characteristic responses to osmotic stress.

During periods of drought or NaCl stress plants increase their pools of free Pro far in excess of the demands of protein synthesis. They do this by inducing Pro biosynthetic enzymes while repressing further synthesis of catabolic enzymes (Delauney and Verma, 1993; Kiyosue et al., 1996; Verbruggen et al., 1996). Although it has been suggested that this increase in free Pro levels is a symptom that results from imbalances in other metabolic pathways (Bhaskaran et al., 1985; Pérez-Alfocea and Larher, 1995), there is considerable evidence that high levels of Pro can be beneficial to stressed plants. For example, exogenously applied Pro was able to reduce the inhibitory effects of excess NaCl or insufficient water on the growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.) (Kavi Kishor, 1989; Krishnamurthy, 1991). Additionally, a genetic modification that increased the basal level of Pro in tobacco reduced the plant's sensitivity to NaCl (Kavi Kishor et al., 1995). This protection can be explained in at least two ways. On one hand, Pro may interact with enzymes to preserve protein structure and activity within the cell. In vitro studies have shown that high concentrations of Pro reduce enzyme denaturation attributable to heat, freeze-thaw cycles, and high NaCl (Pollard and Wyn Jones, 1979; Rajendrakumar et al., 1994). Alternatively, Pro may protect proteins and membranes from damage by inactivating hydroxyl radicals or other highly reactive chemical species that accumulate when stress inhibits electron-transfer processes (Smirnoff and Cumbes, 1989; Saradhi et al., 1995).

These two models of action presume that free Pro functions solely as a solute to shield macromolecules from physical and chemical factors. However, in some organisms other than plants, Pro and its precursor, P5C, have a number of additional effects on physiological processes and gene expression. Pro stimulates calcium uptake in neuronal cells of the mammalian central nervous system (Henzi et al., 1992). P5C selectively inhibits the initiation of translation of mammalian RNAs (Mick et al., 1988) and selectively enhances the accumulation of P1450 mRNA in mice (Nemoto and Sakurai, 1991). Pro also serves as a key source of energy in insect flight muscles (Bursell and Slack, 1976). More generally, Pro oxidation to P5C, and P5C reduction back into Pro, provides cells with a means to generate NADH and NADP+ from surplus amino acids (Fig. 1) (Phang, 1985). Because an increase in the ratio of NADP+ to NADPH can accelerate the catabolism of Glc through the pentose phosphate shunt (Yeh and Phang, 1988), changing the relative rates of Pro synthesis and breakdown can be used to alter the production of substrates for unrelated pathways such as purine biosynthesis.

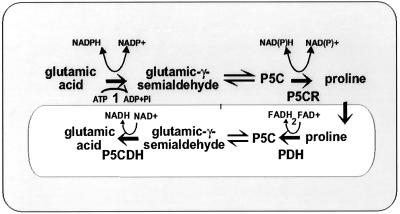

Figure 1.

Stylized outline of Pro metabolism in the cytosol (larger rectangle) and the mitochondria (smaller rectangle). Step 1 is carried out by the multifunctional enzyme P5C synthase. The remaining steps are carried out by P5C reductase (P5CR), Pro dehydrogenase (PDH), and P5C dehydrogenase (P5CDH).

It has been established that many of the genes associated with carbon use are regulated by both growth hormones and changes in levels of particular pathway intermediates or end products (Thomas and Rodriguez, 1994). This dual control provides plants with a means of modulating the impact of the hormone on the expression of a biochemical pathway according to the availability of other metabolites in the cell. We recently found evidence that a superficially similar set of dual controls affects the expression of a rice gene called salT (Garcia et al., 1997). We found that the level of expression of this gene is a particularly sensitive indicator of abiotic stress. It is inducible by NaCl, drought, and ABA (Claes et al., 1990), often under conditions that do not induce any other gene tested. However, it is also inducible by Pro (Garcia et al., 1997), although it plays no apparent role in Pro metabolism. The fact that exogenous application of ABA and Pro are equally effective inducers of gene expression may be an indication that they may be co-regulators of metabolism during osmotic adjustment. In this paper we provide evidence that precursors to Pro, or their analogs, affect respiration, solute accumulation, and the expression of salT and the dehydrin dhn4 (Close et al., 1989), and therefore might serve as modulators of some of the biochemical changes accompanying NaCl stress in rice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Rice (Oryza sativa L. var Cypress) seeds were sown on vermiculite and grown in an environmentally controlled growth chamber at 25°C and 70% RH with a 16-h photoperiod. Seedlings were watered three times a week and supplied with nutrient solution (Yoshida et al., 1976), including 100 μg L−1 silica once a week. Three-week-old seedlings were transferred to 1-L bottles and grown hydroponically in nutrient solution that was changed every 10 to 14 d. All experiments were conducted on 6-week-old seedlings at the three-leaf stage.

Treatment of Plants for Biochemical Analyses

All chemicals tested were obtained from Sigma. All imino acid stock solutions were prepared in distilled water. SHAM and Anti A stocks were prepared in 80% ethanol. Seedlings were treated by replacing the nutrient solution in the bottles with fresh solution containing the appropriate chemicals at the desired concentrations, as indicated below. Sheath, blade, or root material was harvested after 24 h of treatment, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C.

RNA Preparation and Northern-Blot Analyses

Total RNA was prepared according to Hepburn et al. (1983) with the following modifications. Typically, 1 g of sheath material was homogenized in 2 mL of extraction buffer containing 100 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.4), 4 m urea, 6% p-aminosalicylic acid, 2% triisopropylnaphthalene sulfonic acid, 1% (w/v) SDS, 2 mm EDTA, and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, then extracted twice with phenol:chloroform (1:1, v/v) and once with chloroform. RNA was precipitated with 4 m lithium chloride, and the pellet was washed and dried as described (Hepburn et al., 1983). For northern-blot analyses, 12 μg of total RNA was electrophoresed on 1.2% formaldehyde-agarose gels and blotted onto nylon membranes (Hybond-N, Amersham) following standard procedures (Maniatis et al., 1982). Blots were hybridized with appropriate 32P-labeled cDNA probes prepared using the Radprime DNA-labeling kit (GIBCO-BRL) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Hybridizations were carried out in 6× SSPE, 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.5% (w/v) SDS, and 50 μg mL−1 heparin at 65°C for 16 h. The filters were washed with 1× SSPE and 0.1% (w/v) SDS at 65°C and autoradiographed. Probes consisted of the rice genes salT (Claes et al., 1990), sam (S-adenosylmethionine synthase; Van Breusegem et al., 1994b), and rab16 (Mundy and Chua, 1988), a rice hsp70 (Sasaki et al., 1994) that is homologous to the major maize heat-shock 70 protein, the wheat gene Em (Litts et al., 1987), and the barley genes dhn4 and dhn5 (Close et al., 1989, 1995).

O2-Uptake Studies

Sheath material from each seedling was cut into small pieces that measured about 3 mm and weighed between 65 and 95 mg, suspended in 2 mL of distilled water in a cuvette fitted with an O2 electrode (Hansatech, Norfolk, UK), and stirred continuously. The O2 concentration in the solution was measured at 25°C and recorded by an Omnitracer recorder (Houston Instruments, Austin, TX). The O2 concentration in air-saturated water was assumed to be 240 μm. All values presented are the means from three independent experiments. Each experimental value in turn is the mean from five measurements, each from an independent seedling of the same treatment.

Measurement of NADH and NADPH Levels

Extraction of reduced pyridine nucleotides was done according to the method of Klingenberg (1974). One gram of quick-frozen and powdered sheath material was suspended with continuous stirring in 10 mL of 0.5 m alcoholic KOH, precooled at −17°C in an ice-NaCl bath. The extracts were incubated in a 90°C water bath for 5 min and cooled rapidly on ice. After 5 min, the pH of the extracts was adjusted to 7.8 by slowly adding 4 mL of triethanolamine HCl-phosphate mixture with cooling and stirring. After incubation at room temperature for 10 min, the flocculated, denatured proteins were removed by centrifugation at 28,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The clear supernatants were used for the assay.

Pyridine nucleotide assays were performed according to the method of Peine et al. (1985). NADH and NADPH were assayed by an enzymatic-cycling technique, including an enzyme reaction and the coupled nonenzymatic dichlorophenol indophenol reduction via phenazine methosulfate. The reaction mixture contained 60 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.6), 4 mm EDTA, 1 m ethanol or 30 mm Glc-6-P, 7 mm phenazine methosulfate, and 1 mm dichlorophenol indophenol. Alcohol dehydrogenase (80 units) was used for NADH determination and Glc-6-P dehydrogenase (5 units) was used to determine NADPH. The stoichiometric dichlorophenol indophenol reduction was monitored at 625 nm using a spectrophotometer (model DU-50, Beckman). The change in absorbance (A625) in a reaction mixture containing 100 μL of the extract for a period of 5 min was recorded, and the rate of reduction of absorbance (A625 min−1) was calculated. A standard curve was prepared by determining the A625 min−1 obtained with four different amounts of NADH or NADPH from 0 to 100 nm. The rate of reduction was directly proportional to the amount of NADH or NADPH added. Each experiment was repeated two to three times, as indicated.

ABA Measurements

Six-week-old rice plants were treated for 24 h, as indicated. At the end of this period, sheaths were harvested and immediately frozen in liquid N2. ABA was extracted according to the method described by Walker-Simmons (1987) with slight modifications. Typically, about 200 mg of frozen sheath material was ground to a fine powder using a precooled mortar and pestle. This was extracted with 20 mL of methanol containing 100 mg L−1 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methyl phenol (Aldrich) and 0.5 g L−1 citric acid monohydrate. Extracts were stirred in the dark at 4°C for 20 h and then centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min. The supernatants were purified by passage through Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (Waters) and dried. Samples were then resuspended in 0.1 mL of methanol and 0.9 mL of distilled water. Before assaying, samples were centrifuged briefly to remove insoluble material.

ABA levels were determined according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Idetek, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA). The absorbance of the immunochemical assay was read at 405 nm using an EIA reader (model EL308, Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Measured values were compared with a standard curve made from 1 mm (±)-cis,trans-ABA (Sigma) dissolved in methanol and diluted from 5.0 to 50 pmol mL−1 in 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, with 150 mm NaCl and 1.0 mm MgCl2. Each experiment was replicated twice and the results were averaged.

GC-Flame Ionization Detector Analyses of Sugars, Polyols, and Acids

Plant material was ground to a fine powder in liquid N2, and then extracted and derivatized according to a procedure modified from the work of Sweeley et al. (1963). The trimethylsilyl derivatives of sugars, polyols, and acids were assayed, quantitated, and verified as described by Garcia et al. (1997).

RESULTS

Pro Metabolites Are More Potent Than Pro as Inducers of Gene Expression

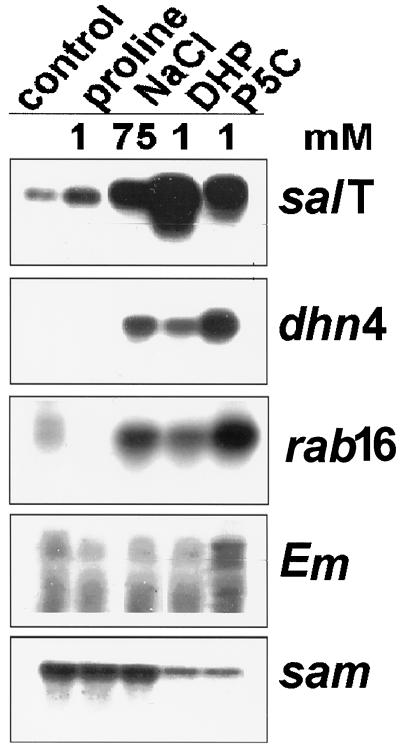

Garcia et al. (1997) have shown that 10 to 50 mm Pro inhibits rice growth and induces salT as effectively as 171 mm NaCl. Because endogenously made Pro is not distributed uniformly either within cells or between them (Pahlich et al., 1983; Vartanian et al., 1992), exogenously provided Pro may similarly be partitioned unequally. A simplistic explanation that is consistent with our observations (Garcia et al., 1997) is that an unequal accumulation of exogenous Pro in rice temporarily produces an osmotic stress. An alternative and more direct explanation is that Pro serves either as an inducer or as the precursor for an inducer of some of the genes needed to counter osmotic stress. To help distinguish between these explanations, we first sought to establish the chemical specificity of this effect. To do this, we tested several Pro analogs and pathway precursors listed in Table I. The results of northern-blot analysis of RNA from rice plants treated with some of these substances are shown in Figure 2. salT is barely detected in carefully cultured rice plants (Claes et al., 1990; Garcia et al., 1997), but in this particular experiment growth conditions inadvertently led to some salT messenger accumulation in control plants. This stress was not so severe as to induce dhn4, another osmotically regulated gene (Close et al., 1989), but did sensitize the plants so that transcription increased in response to 1 mm Pro, whereas normally, much higher Pro levels are needed (Garcia et al., 1997). However, neither this treatment nor 75 mm NaCl was as effective as treatments with two oxidized derivatives of Pro: P5C and its analog, DHP.

Table I.

Summary of relevant biological properties of Pro analogs on Pro metabolism

| Molecule | Pro Transport Inhibitora,b,c | Inhibitor of Pro Dehydrogenaseb | Incorporated into Proteind,e | Stimulates Oxygen Uptake in Vitrof | Effect on salT mRNA Accumulationg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro | − | − | + | + | + |

| P5C | unk. | + | − | unk. | ++ |

| d-Pro | ± | unk. | ± | − | − |

| DHP | + | + | ± | + | ++ |

| Thiaproline | unk. | + | − | ± | ± |

Of these compounds, only Pro and P5C are natural to all cells. −, Little to no effect; ±, weakly effective; +, effective; ++, very effective; and unk, unknown (not tested).

Freemeau et al., 1992.

Figure 2.

Effect of NaCl, Pro, P5C, and DHP on gene expression. Six-week-old rice plants were grown hydroponically for 24 h in medium supplemented with the indicated concentration of each chemical. At the end of the treatment, RNA was prepared from the sheaths and 12 μg was separated on 1.2% formaldehyde-agarose gels. The gel was then processed for northern-blot analysis using standard methods and probed with radioactive fragments of each gene indicated.

A time-course experiment was done to determine whether rice responded more quickly to one of these imino acids. Plant sheaths were assayed for salT expression 3, 8, and 24 h after treatment with 1 mm l-Pro, P5C, and DHP. Little or no salT expression was seen before 24 h (data not shown). At that time, there was approximately 2-fold more salT RNA in DHP-treated plants than in plants treated with P5C. There was no response to Pro in this experiment.

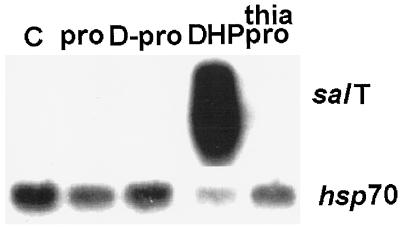

To verify that the effect of Pro derivatives on osmotically responsive gene expression was specific, filters were rehybridized with a third osmotically regulated gene, Em (Litts et al., 1987), and one basic metabolic gene, sam (Van Breusegem et al., 1994b). Each of the three osmotically regulated genes responded differently to the treatments. Whereas the accumulation of Em mRNA was not affected by the treatments used, mRNA levels for salT and dhn4 were markedly, albeit differentially, affected by P5C and DHP. P5C and DHP also induced another dehydrin gene, rab16 (Mundy and Chua, 1988), but only marginally affected a cold-induced dehydrin, dhn5 (Close et al., 1995; data not shown). These treatments actually reduced sam expression somewhat, indicating that they had not increased either transcription, RNA processing, or messenger stability indiscriminately. Further studies using plants that were not already expressing salT showed that two other Pro analogs, d-Pro and thiaproline, were no better than Pro as inducers of salT (Fig. 3), Em, dhn4, and dhn5 (data not shown). In this case, we also assayed for the expression of hsp70 (Sasaki et al., 1994), which can be induced by severe osmotic stress (Borkird et al., 1991), but found that its expression was not coordinated with salT.

Figure 3.

Effect of several Pro analogs on gene expression. Plants were treated with 1 mm of each chemical and analyzed as described in the legend to Figure 2. C, Control, untreated.

Respiration Rate Affects Gene Induction by NaCl and Glu, but Not P5C

We next investigated whether salT mRNA levels could be elevated by making the precursors to P5C more available. P5C is synthesized from Glu and NADPH (Fig. 1). Figure 4 shows that 1 mm Glu did enhance the expression of salT, but less effectively than the same amount of DHP. It is interesting that supplying plants with both Glu and enough Anti A to block O2 consumption by approximately 20% (data not shown) induced genes better than either could alone (Fig. 4). The same effect was found when plants were treated with NaCl. Figure 4 shows that Anti A treatment had no effect on its own. Nevertheless, it enhanced the induction of salT by NaCl when the two treatments were combined. Based on these changes in messenger level, it appears that plants are either more sensitive to NaCl and Glu, or alternatively, better able to synthesize or accumulate the NaCl-induced signal, when NADH levels are increased or NADPH levels are reduced (see Table II).

Figure 4.

Glu and NaCl are more effective inducers when respiration is inhibited. Plants were treated with 1 mm Glu or DHP, 75 mm NaCl, or 20 μm Anti A for 24 h, and then analyzed as described in the legend to Figure 2.

Table II.

Respiratory activity of sheath segments from plants grown for 24 h with metabolic inhibitors, DHP, or P5C

| Treatment | O2 | Control | NADPH | NADH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol min−1 g−1 fresh wt | % | mmol g−1 fresh wt | ||

| Control | 65 ± 1.0 | 100 | 50 ± 0.5 | 8 ± 1.3 |

| 1 mm P5C | 37 ± 1.7 | 57 | 32 ± 2.5 | 41 ± 3.3 |

| 1 mm DHP | 38 ± 0.5 | 58 | 35 ± 0.0 | 42 ± 2.0 |

| 20 μm Anti A + 2 mm SHAM | 34 ± 0.8 | 52 | 40 ± 0.0 | 53 ± 2.2 |

| 20 μm Anti A + 1 mm DHP | 34 ± 1.9 | 52 | 30 ± 5.0 | 41 ± 2.9 |

Each value is the average ± se of two NADPH or three O2 and NADH experiments.

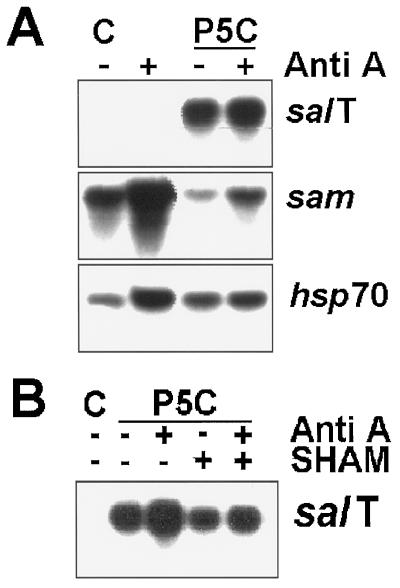

A priori the entry of amino acids into plants might be physiologically coupled to an influx of ions. In this event these inorganic molecules might be the true inducers of salT and dhn4. If so, inhibiting respiration with Anti A should have the same effect on DHP- and P5C-induced gene expression as on NaCl-induced gene expression. Instead, neither Anti A nor Anti A with SHAM affected P5C-induced gene expression (Fig. 5, A and B). In fact, Anti A actually reduced the response to DHP-treatment slightly (Fig. 4). This latter result will be examined further in the presentation of Figure 7. As in earlier experiments, sam messenger levels decreased during those treatments that induced salT (Figs. 2 and 4).

Figure 5.

P5C induction does not depend on respiration. Plants were treated with or without 1 mm P5C, and with (+) or without (−) 20 μm Anti A (A) or 20 μm Anti A and 2 mm SHAM (B), for 24 h, and then analyzed as described in the legend to Figure 2. C, Control, untreated.

Figure 7.

Gene induction by DHP depends on respiration. Six-week-old rice plants were treated for 24 h with 1 mm DHP or P5C, 20 μm Anti A, and 2 mm SHAM as indicated. RNA was prepared from the sheaths, processed for northern-blot analysis, and probed with salT, sam, and hsp70. C, Control, untreated.

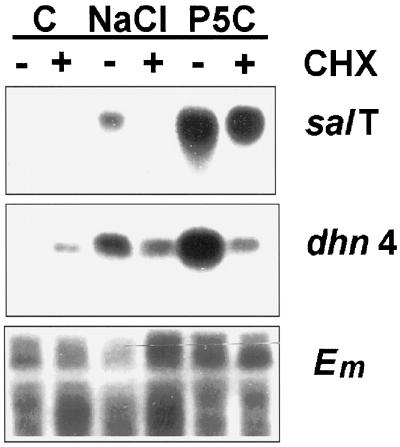

Gene Induction by P5C Does Not Depend on Protein Synthesis

We also compared the effect of CHX on induction by NaCl and by P5C. The expression of salT was not induced by NaCl if protein synthesis was inhibited by CHX (Fig. 6). If imino acid treatment induced gene expression like inorganic ions, then we expected that the effect of P5C would similarly be blocked by CHX. Instead, CHX had no effect on P5C-inducible expression of salT, or on the levels of Em. Unexpectedly, CHX did induce expression of dhn4 in the absence of other stimuli. It also reduced the response of this gene to both NaCl and P5C. It is possible that a single, rapidly turning-over protein is both repressing dhn4 in healthy sheaths and necessary to help positive regulatory factors bind their targets in stressed sheaths, but further work on this model is beyond the scope of the current study.

Figure 6.

P5C induction does not depend on protein synthesis. Plants were treated with or without 1 mm P5C or 75 mm NaCl, and with (+) or without (−) 20 μm CHX for 24 h, and then analyzed as described in the legend to Figure 2. C, Control, untreated.

DHP Needs to Be Oxidized to Act as an Inducer of salT

During the course of our studies using metabolic inhibitors, we found that P5C (as well as DHP) reduced O2 consumption by more than 40% (Table II). It was possible that exogenously provided P5C and DHP were inhibiting O2-consuming processes such as peroxidases or some chloroplastic and glyoxysomal enzymes. However, there was no additional decrease in O2 consumption when Anti A was used with DHP (Table II), and further studies showed that P5C and DHP treatments increased NADH levels as much as DHP and Anti A did together (Table II).

The NADPH levels may have decreased because Pro synthesis from exogenous imino acids proceeded faster than NADPH regeneration. The excess Pro produced by this treatment may have then been imported into the mitochondrion and oxidized back to P5C to produce the observed increase in NADH (see Fig. 1). This cycle of reduction and oxidation might explain the one major difference between the effect of P5C and DHP on gene expression. SHAM and Anti A had no effect on salT induction by P5C (Fig. 5). By contrast, Figures 4 and 7 show that treatment with Anti A reduced the effectiveness of DHP as an inducer. Furthermore, combining Anti A with SHAM further reduced the effectiveness of DHP (Fig. 7). Based on these results, we propose that DHP is not highly active until it is reduced to Pro and then reoxidized into P5C. Thus, when respiration levels were reduced by treatment with inhibitors, P5C production declined.

We have noticed that most treatments inhibiting respiration (P5C, DHP, Anti A, Anti A plus SHAM) elevated hsp70 mRNA levels slightly. However, this effect was minor compared with the effect of P5C or DHP on salT and with the effect of other factors such as ethanol, high-NaCl concentrations, and darkness on hsp70 (Borkird et al., 1991; Van Breusegem et al., 1994a). None of the treatments used here induced sam mRNA levels significantly.

Could P5C Be Inducing ABA?

It has been shown that ABA reduces tissue respiration in stress-free conditions (Gude et al., 1988; Tetteroo et al., 1995). Consequently, one explanation for the results in Table II is that P5C, DHP, or Glu is disturbing the plants in some way so that ABA accumulates until it induces the changes in gene expression and respiration that we have noted. To test for accumulation of this hormone, we measured ABA levels in the sheaths of plants that had been grown with NaCl, P5C, and DHP. The results are shown in Table III.

Table III.

P5C does not induce a significant accumulation of ABA

| Treatment | ABA |

|---|---|

| pmol g−1 fresh wt | |

| No treatment | 82 ± 7.5 |

| 20 μm ABA | 875 ± 125 |

| 75 mm NaCl | 255 ± 5.0 |

| 1 mm Pro | 119 ± 41 |

| 1 mm P5C | 76 ± 24 |

| 1 mm DHP | 87 ± 9.0 |

| 20 μm CHX | 88 ± 27 |

| 75 mm NaCl + 20 μm CHX | 146 ± 50 |

| 1 mm P5C + 20 μm CHX | 92 ± 14 |

Six-week-old rice plants were grown hydroponically for 24 h with each of the indicated chemicals. At that time, the sheaths were harvested, frozen, and extracted according to established procedures (Walker-Simmons, 1987). ABA was then measured immunologically. Each value represents the average of two independent treatments ± se.

ABA levels in sheaths increased approximately 10-fold if they were grown with 20 μm ABA, the amount of hormone needed to induce salT to a high level (Claes et al., 1990). NaCl stress, which is clearly a weaker inducer during this period of time, increased ABA levels 4-fold over basal measurements. No significant ABA accumulation was detected with Pro, P5C, or DHP, or with NaCl and CHX combined. The effect of the imino acids on salT induction therefore appears to be ABA independent.

NaCl, P5C, and DHP Treatments Alter Steady-State Levels of Many Organic Solutes

Rice accumulates a variety of small, hydrophilic molecules during osmotic stress (Garcia et al., 1997). A few of these solutes are believed to be made especially to reestablish the osmotic potential needed to bring water into the plant (Binzel et al., 1987) or to protect the structural integrity of some components of the cell (Crowe et al., 1984). If Pro metabolic products are influencing the response of the plant to NaCl stress, then externally provided P5C and DHP might change the steady-state levels of these osmotically regulated solutes.

Because NaCl-induced changes in gene expression, cell appearance, and solute accumulation differ in different parts of the plant (Garcia et al., 1997), we analyzed solute pools in two different organs: the uppermost blades and the roots (Table IV). The levels of many solutes in the roots proved to be below the levels of detection of our assay. By contrast, blades contained a variety of sugars, organic acids, and inositol. Treating plants with NaCl effected major changes in the concentrations of many of these compounds, not just the sugars and polyols commonly viewed as osmoprotectants. For instance, Glc and Fru levels increased 3- to 4-fold in the blades, whereas malic acid and inositol levels doubled. Strikingly, the pool sizes of both Suc and mannitol, which are known to be effective osmoprotectants (Crowe et al., 1984), increased in blades but not in roots.

Table IV.

Solute pools (mg g−1 fresh wt) in blades and roots of rice plants after 24-h treatments with NaCl, P5C, and DHP

| Treatment | Succinate | Malate | Citrate | Salicylate | Mannitol | Inositol | Glc | Fru | Suc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blades | |||||||||

| Control | nd | 46 | 29 | 24 | nd | 19 | 49 | 43 | 1080 |

| 75 mm NaCl | 32 | 82 | 32 | nd | 6.0 | 35 | 200 | 160 | 2670 |

| 1 mm P5C | 13 | 50 | nd | 140 | nd | 17 | 33 | 35 | 740 |

| 1 mm DHP | 68 | 210 | 95 | 270 | 12 | nd | 340 | 290 | 4400 |

| Roots | |||||||||

| Control | nd | 6.0 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 64 |

| 75 mm NaCl | 12 | 9.0 | nd | 13 | nd | nd | 10 | 6.0 | 54 |

| 1 mm P5C | nd | 74 | nd | 11 | nd | nd | 62 | 47 | 1310 |

| 1 mm DHP | nd | 10 | nd | 11 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 20 |

nd, Not detected.

We next compared the solute pools in NaCl-grown rice with the pools of plants treated with 1 mm P5C or DHP for the same period of time. Despite the differences in both the concentration and the chemistry of the three inducers, they produced qualitatively similar effects. In the most general terms, the effects of NaCl and P5C were similar in roots, whereas NaCl and DHP treatments produced similar effects in the blades (Table IV). In each of these cases, though, the imino acid produced more dramatic effects than NaCl on the free solutes assayed. For example, NaCl and P5C induced the accumulation of each of the sugars and several organic acids in roots. By contrast, DHP induced the accumulation of malic and salicylic acids, but had no effect on succinic acid or the sugar pools.

A complementary effect was seen in the blades, but here DHP proved as effective as NaCl, whereas P5C did not. For example, both NaCl and DHP markedly increased the amounts of monosaccharides and Suc, whereas P5C treatment had very little effect. In fact, P5C did not affect the levels of any of the substances assayed in this organ by more than 30%, except for salicylic acid. Whereas we cannot say at this time whether the changes in the organic acids and sugars are caused by changes in gene expression or are instead simply consequences of the inhibition of respiration, it is apparent that some of the metabolic correlates of NaCl stress can be mimicked by treatment with P5C and its analog, DHP.

DISCUSSION

Plants must change dozens of physiological processes and biochemical pathways to minimize the damaging effects that osmotic stress has on cell structure and enzyme activity. One part of this process of osmotic adjustment includes the synthesis of proteases, chaperones, and hydrophilic proteins called dehydrins (Mundy and Chua, 1988; Guerrero et al., 1990; Borkird et al., 1991). Another part of the adaptive process includes production and accumulation of comparatively low-molecular-weight osmoprotectants that help to preserve structural integrity and osmotic potential within different compartments of the cell (Bartels et al., 1991; Vernon and Bohnert, 1992).

The key regulatory molecule that coordinates these defenses is the hormone ABA (LaRosa et al., 1987). However, ABA is not the sole regulator of all of these genes. Several examples have been found of genes that are either induced by NaCl stress but not by ABA (Thomas et al., 1992), or are dependent on both NaCl and ABA for maximal expression (Bostock and Quatrano, 1992). In fact, even the accumulation of Pro itself may be only coincident with the increase of intracellular ABA rather than induced by it (Stewart and Voetberg, 1987; Thomas et al., 1992).

Gene Expression Can Be Affected by the Availability of Precursors for P5C Synthesis

We do not know which types of signal molecules mediate ABA-independent gene regulation; however, the results presented here indicate that one such signal might be derived from the Pro biosynthetic and catabolic pathways. We have found that dhn4 and salT can be induced not only by NaCl, but also by treating rice plants with exogenous P5C, or with either of two P5C precursors, Glu and Pro. In addition, the transcriptional response to NaCl and Glu is enhanced in plants treated with Anti A. This effect demands further study before it can be interpreted. We found that antimycin treatment reduced the levels of NADPH and elevated those of NADH. It is possible that the rice P5C synthetase was able to use some of this NADH to accelerate Glu reduction. Alternatively, NADP+ levels may have risen sufficiently to inhibit P5C reductase (Szoke et al., 1992) so that P5C could accumulate.

If P5C is used as a signal during osmotic stress, then it should produce the same effects as NaCl. In general, P5C did induce effects similar to those of NaCl in the sheath. We found that both molecules depressed O2 consumption and enhanced NADH accumulation and gene expression in similar ways. However, differences between these two treatments were seen when assays were performed on blade ends and on roots. In particular, P5C affected solute accumulation in roots, yet had little effect on solute pools in the upper blade. It is known that NaCl is transported well into rice blades (Garcia et al., 1997), but P5C might be catabolized during its passage upward so that too little reaches the blades to affect the physiology.

DHP acted much like P5C, with one significant difference: it affected solute accumulation in blades, yet had little effect on solute accumulation in roots. It is known that other biological systems such as bacteria (Wood, 1981), embryonic cartilage cells (Rosenbloom and Prockop, 1970), and isolated maize mitochondria (Elthon and Stewart, 1984) can catabolize DHP in some way. It is possible that similar reactions are being carried out in rice, allowing some DHP to be converted into either P5C or another inducer. The amount of DHP catabolized in roots may not be sufficient to affect solute levels, but as it reaches the upper parts of the plant, enough could be catabolized to affect gene expression and solute accumulation. If DHP was converted into Pro and subsequently into P5C, then the two imino acids should be equally effective. Instead, Pro was a weak inducer in comparison with DHP. This could be evidence that DHP is not catabolized into Pro, or, alternatively, that DHP is transported upward by means of a P5C transporter like those in mammals that discriminate against Pro (Mixson and Phang, 1991).

Could the Effects of P5C Be Artifacts of Poisoning?

The effects on gene expression that we have monitored have been produced using toxic or potentially toxic chemicals (Table I). P5C is provided as a 2,4 dinitrophenylhyd-razine salt to stabilize it. This contaminant might inhibit some enzymes in the cells, including those needed for respiration. If so, its target was different from known inhibitors such as Anti A, SHAM, and CHX, which did not induce salT. Moreover, Glu proved more effective at inducing salT than two toxic imino acids, d-Pro and thiaproline. DHP is also a growth-inhibiting analog that can be incorporated into proteins and thereby change gene expression through the misfolding of newly made transcription factors. If this was its primary mode of action in our studies, then inhibiting its reduction into Pro should have increased its effect on salT expression. However, Anti A and SHAM actually reduced the effect of DHP on the accumulation of salT mRNA.

Does Induction of Dehydrins and salT by Imino Acids Have Biological Significance?

The results summarized here are consistent with the hypothesis that P5C, glutamic-γ-semialdehyde, or a molecule derived from them is able to regulate the expression of some rice genes. However, we have not established how significant this effect is during osmotic stress. Further studies are also necessary to determine why rice is responding to a common metabolite within the Pro biosynthetic pathway rather than to a more stress-specific metabolite. One trivial explanation is that the genes chosen to monitor plant responses, dehydrins and salT, are specifically produced so that they can play an unidentified role in Pro metabolism. Alternatively, the synthesis of these gene products may be coordinated with the accumulation of Pro because they are used in complementary ways to preserve cell structures during stress. Finally, it may be advantageous to control these genes by both ABA and P5C so that their products can accumulate before the concentration of either inducer has reached its maximum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs. David Oliver and Robert Behal for advice and guidance through the intricacies of biochemistry, and Drs. Zhixiang Chen and Bruce Miller for careful reading of an earlier version of this paper. We thank the following people for providing genes: Dr. Ralph Quatrano for the clone of Em, Dr. Tim Close for the clones of several barley dehydrin genes, including dhn4, and Dr. Henry Nguyen for the clone of rab16.

Abbreviations:

- Anti A

antimycin A

- CHX

cycloheximide

- DHP

3,4-dehydroproline

- P5C

Δ1- pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid

- SHAM

salicylhydroxamic acid

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by a Seed Grant from the University of Idaho, a grant from the State Board of Education of Idaho to A.C., and a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (no. 95-37304-2323) to A.W. Sylvester and A.C.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bartels D, Engelhardt R, Roncarati R, Schneider K, Rotter M, Salamini F. An ABA and GA modulated gene expressed in the barley embryo encodes an aldose reductase related protein. EMBO J. 1991;10:1037–1043. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran S, Smith RH, Newton RJ. Physiological changes in cultured sorghum cells in response to induced water stress. Plant Physiol. 1985;79:266–269. doi: 10.1104/pp.79.1.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binzel ML, Hasegawa PM, Rhodes D, Handa S, Handa AK, Bressan RA. Solute accumulation in tobacco cells adapted to NaCl. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:1408–1415. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.4.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkird C, Claes B, Caplan A, Simoens C, Van Montagu M. Differential expression of water-stress associated genes in tissues of rice plants. J Plant Physiol. 1991;138:591–595. [Google Scholar]

- Bostock RM, Quatrano RS. Regulation of Em gene expression in rice. Interaction between osmotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:1356–1363. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.4.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursell E, Slack E. Oxidation of proline by sarcosomes of the tsetse fly, Glossina morsitans. Insect Biochem. 1976;6:159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Claes B, Dekeyser R, Villarroel R, Van den Bulcke M, Bauw G, Van Montagu M, Caplan A. Characterization of a rice gene showing organ-specific expression in response to salt stress and drought. Plant Cell. 1990;2:19–27. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close TJ, Kortt AA, Chandler PM. A cDNA-based comparison of dehydration-induced proteins (dehydrins) in barley and corn. Plant Mol Biol. 1989;13:95–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00027338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close TJ, Meyer NC, Radik J. Nucleotide sequence of a gene encoding a 58.6-kilodalton barley dehydrin that lacks a serine tract. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:289–290. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JB, Varner JE (1983) Selective inhibition of proline hydroxylation by 3,4-dehydroproline. Plant Physiol 73: 324–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crowe LM, Mouradian R, Crowe JH, Jackson SA, Womersley C. Effects of carbohydrates on membrane stability at low water activities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;769:141–150. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delauney AJ, Verma DPS. Proline biosynthesis and osmoregulation in plants. Plant J. 1993;4:215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dila DK, Maloy SR. Proline transport in Salmonella typhimurium: putP permease mutants with altered substrate specificity. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:590–594. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.590-594.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elthon TE, Stewart CR. Effects of the proline analog l-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid on proline metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1984;74:213–218. doi: 10.1104/pp.74.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Caron MG, Blakely RD. Molecular cloning and expression of a high affinity L-proline transporter expressed in putative glutamatergic pathways of rat brain. Neuron. 1992;8:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90206-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A-B, de Almeida Engler J, Iyer S, Gerats T, Van Montagu M, Caplan AB (1997) Effects of osmoprotectants upon NaCl stress in rice. Plant Physiol 115: 159–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gude H, Beekman A, Van't Padje PHB, Van der Plas LHW. The effects of abscisic acid on growth and respiratory characteristics of potato tuber tissue discs. Plant Growth Regul. 1988;7:101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero FD, Jones JT, Mullet JE. Turgor-responsive gene transcription and RNA levels increase rapidly when pea shoots are wilted: sequence and expression of three inducible genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15:11–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00017720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henzi V, Reichling DB, Helm SW, MacDermott AB. L-Proline activates glutamate and glycine receptors in cultured rat dorsal horn neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:793–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn AG, Clarke LE, Pearson L, White J. The role of cytosine methylation in the control of nopaline synthase gene expression in a plant tumor. J Mol Appl Genet. 1983;2:315–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavi Kishor PB. Salt stress in cultured rice cells: effects of proline and abscisic acid. Plant Cell Environ. 1989;12:629–633. [Google Scholar]

- Kavi Kishor PB, Hong Z, Miao G-H, Hu C-AA, Verma DPS. Overexpression of Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid synthetase increases proline production and confers osmotolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1387–1394. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerwar SS, Marcel RJM, Stewart RA. Studies on the effect of L-3,4-dehydroproline on collagen synthesis by chick embryo polysomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976;172:685–688. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyosue T, Yoshida Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. A nuclear gene encoding mitochondrial proline dehydrogenase, an enzyme involved in proline metabolism, is upregulated by proline but downregulated by dehydration in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1323–1335. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.8.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg M (1974) Nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotides (NAD, NADH, NADP, NADPH): spectrophotometric and fluorometric methods. In HU Bergmeyer, ed, Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, Ed 2. Academic Press, New York, pp 2045–2059

- Krishnamurthy R. Amelioration of salinity effect in salt tolerant rice (Oryza sativa L.) by foliar application of putrescine. Plant Cell Physiol. 1991;32:699–703. [Google Scholar]

- LaRosa PC, Hasegawa PM, Rhodes D, Clithero JM, Watad A-EA, Bressan RA. Abscisic acid stimulated osmotic adjustment and its involvement in adaptation of tobacco cells to NaCl. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:174–181. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.1.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litts JC, Colwell GW, Chakerian RL, Quatrano RS. The nucleotide sequence of a cDNA clone encoding the wheat Em protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3607–3618. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.8.3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mick SJ, Thach RE, Hagedorn CH. Selective inhibition of proteins synthesized from different mRNA species in reticulocyte lysates containing L-pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;150:296–303. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90519-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mixson AJ, Phang JM. Structural analogues of pyrroline 5-carboxylic acid specifically inhibit its uptake into cells. J Membr Biol. 1991;121:269–277. doi: 10.1007/BF01951560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy J, Chua N-H. Abscisic acid and water stress induce the expression of a novel rice gene. EMBO J. 1988;7:2279–2286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto N, Sakurai J. Proline is required for transcriptional control of the aromatic hydrocarbon-inducible P1450 gene in C57BL/6 mouse monolayer-cultured hepatocytes. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1991;82:901–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1991.tb01919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahlich E, Kerres R, Jäger H-J. Influence of water stress on the vacuole/extravacuole distribution of proline in protoplasts of Nicotiana rustica. Plant Physiol. 1983;72:590–591. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.2.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peine G, Hoffman P, Seifert G, Schilling G. Pyridine nucleotide pattern and reduction charge in wheat seedlings with special regard to different photosynthetic conditions. Biochem Physiol Pflanzen. 1985;180:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Alfocea F, Larher F. Effects of phlorizin and p-chloromercuribenzene-sulfonic acid on sucrose and proline accumulation in detached tomato leaves submitted to NaCl and osmotic stresses. J Plant Physiol. 1995;145:367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Phang JM. The regulatory functions of proline and pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1985;25:91–132. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152825-6.50008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard A, Wyn Jones RG. Enzyme activities in concentrated solutions of glycinebetaine and other solutes. Planta. 1979;144:291–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00388772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendrakumar CSV, Reddy BVD, Reddy AR. Proline-protein interactions: protection of structural and functional integrity of M4 lactate dehydrogenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:957–963. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom J, Prockop DJ. Incorporation of 3,4-dehydroproline into protocollagen and collagen. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:3361–3368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saradhi PP, Arora S, Prasad KVSK. Proline accumulates in plants exposed to UV radiation and protects them against induced peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;290:1–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Song J, Koga-Ban Y, Matsui E, Fang F, Higo H, Nagasaki H, Hori M, Miya M, Murayama-Kayano E and others. Toward cataloging all rice genes: large-scale sequencing of randomly chosen rice cDNAs from a callus cDNA library. Plant J. 1994;6:615–624. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6040615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff N, Cumbes QJ. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of compatible solutes. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:1057–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CR, Voetberg G. Abscisic acid accumulation is not required for proline accumulation in wilted leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987;83:747–749. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.4.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeley CC, Bentley R, Makita M, Wells WW. Gas-liquid chromatography of trimethylsilyl derivatives of sugars and related substances. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:2497–2507. [Google Scholar]

- Szoke A, Miao G-H, Hong Z, Verma DPS. Subcellular location of Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid reductase in root/nodule and leaf of soybean. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:1642–1649. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetteroo FAA, Peters AHLJ, Hoekstra FA, Van der Plas LHW, Hagendoorn MJM. ABA reduces respiration and sugar metabolism in developing carrot (Daucus carota L.) embryoids. J Plant Physiol. 1995;145:477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BR, Rodriguez RL. Metabolite signals regulate gene expression and source/sink relations in cereal seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1235–1239. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, McElwain EF, Bohnert HJ. Convergent induction of osmotic stress responses. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:416–423. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.1.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Breusegem F, Dekeyser R, Garcia A-B, Claes B, Gielen J, Van Montagu M, Caplan AB. Heat-inducible rice hsp82 and hsp70 are not always co-regulated. Planta. 1994a;193:57–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00191607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Breusegem F, Dekeyser R, Gielen J, Van Montagu M, Caplan A. Characterization of a S-adenosylmethionine synthetase gene in rice. Plant Physiol. 1994b;105:1463–1464. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.4.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian N, Hervochon P, Marcotte L, Larher F. Proline accumulation during drought rhizogenesis in Brassica napus var. oleifera. J Plant Physiol. 1992;140:623–628. [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen N, Hua X-J, May M, Van Montagu M. Environmental and developmental signals modulate proline homeostasis: evidence for a negative transcriptional regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8787–8791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon DM, Bohnert HJ. Increased expression of a myo-inositol methyl transferase in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum is part of a stress response distinct from Crassulacean acid metabolism induction. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:1695–1698. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Simmons K. ABA levels and sensitivity in developing wheat embryos of sprouting resistant and susceptible cultivars. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:61–66. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JM. Genetics of L-proline utilization in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:895–901. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.3.895-901.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh GC, Phang JM. Stimulation of phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate and purine nucleotide production by pyrroline-5-carboxylate in human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:13083–13089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Forno DA, Cock JH Gomez KA (1976) Laboratory Manual for Physiological Studies of Rice, Ed 3. International Rice Research Institute, Los Baños, The Philippines