Abstract

Atopic dermatitis now affects one in five children, and may progress to asthma and hay fever. In the absence of effective treatments that influence disease progression, prevention is a highly desirable goal. The evidence for most existing disease prevention strategies, such as avoidance of allergens and dietary interventions, has been unconvincing and inconsistent. Fresh approaches to prevention include trying to induce tolerance to allergens in early life, and enhancing the defective skin barrier to reduce skin inflammation, sensitisation and subsequent allergic disease. Early and aggressive treatment of atopic dermatitis represents another possible secondary prevention strategy that could interrupt the development of autoimmunity, which may account for atopic dermatitis persistence. Large scale and long term randomized controlled trials are needed to demonstrate that these ideas result in clinical benefit.

Introduction

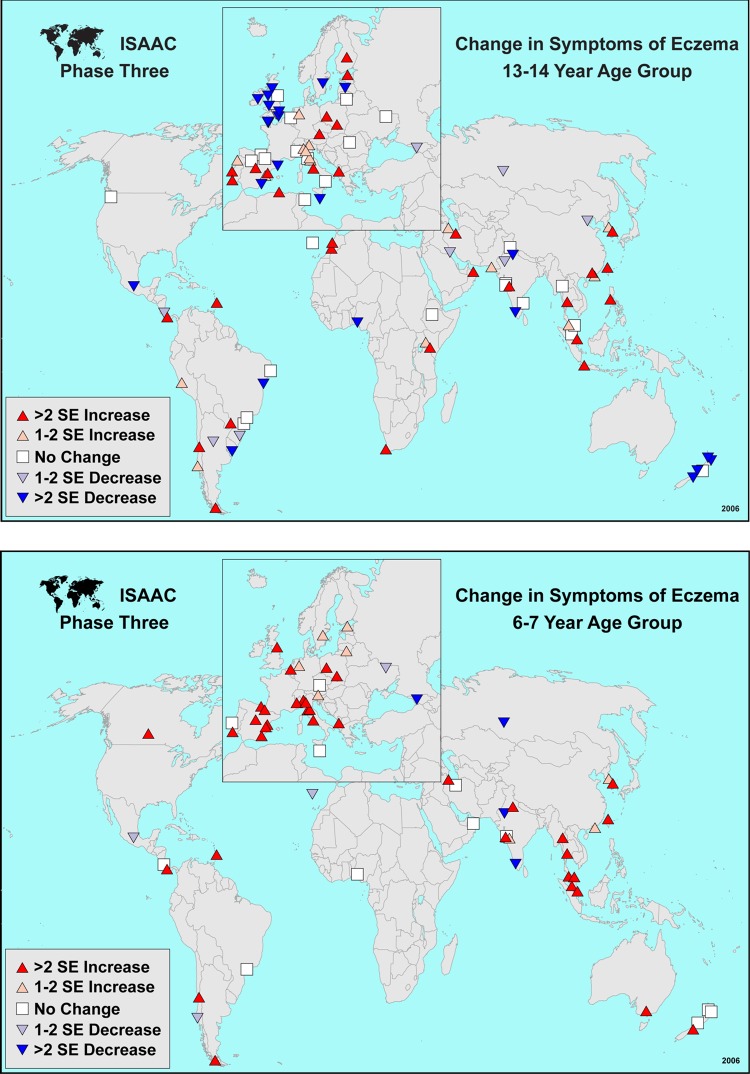

Atopic dermatitis, also known as atopic eczema or just “eczema” [1], is a very common skin condition characterized by skin inflammation and itching that typically starts in early life [2,3]. Atopic dermatitis is associated with dry skin and a tendency towards asthma and hay fever [4,5] and now affects around 20% of children in developed and developing countries [6,7]. Data from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) suggests that atopic dermatitis is increasing (Figure 1), especially in younger children [8]. Genetic factors that determine skin barrier integrity and skin inflammation seem to be important [9,10], but so too is the environment, given the rapid rise in prevalence, and the observation that atopic dermatitis seems to be more common in wealthier, smaller and more educated families [11]. Lack of stimulation of the immune system by microbes at an early age because our children are “too clean” (the hygiene hypothesis) or failure of a balanced gut flora to mature may also be important [12,13]. Whilst some people with atopic dermatitis are clearly allergic to foods and house dust mites, recent studies suggest that the role of allergy in atopic dermatitis might have been overemphasized [14,15]. Current treatments, although quite effective [16], are still geared towards treatment of symptoms and visible signs rather than fundamentally altering the course of disease.

Figure 1a and 1b. World maps from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood.

World maps depicting flexural eczema symptoms in the last year showing changes in the prevalence of eczema symptoms for 13-14 year olds and 6-7 year olds in consecutive prevalence surveys conducted 5-10 years apart. Whilst some levelling off or even a decrease in eczema symptoms are noted in some developed countries in the 13-14 year old group, the trend is for eczema to be increasing throughout the world for the 6-7 year old groups.

In the absence of disease-modifying treatment, attention needs to focus on disease prevention, especially as this might also prevent progression to asthma and hay fever (the “atopic march”). Yet an overview of seven systematic reviews, which included 39 trials on 11,897 participants, concluded that none of the previously tested interventions could be shown to conclusively prevent atopic dermatitis [17]. The possibility that atopic dermatitis may be prevented in a subgroup of infants at high risk of disease by exclusive breastfeeding or the introduction of prebiotics (nutrients that encourage beneficial gut bacteria) was based on limited evidence with potential flaws, [17] although more recent evidence for some probiotics (beneficial live gut bacteria) during and after pregnancy show some promise [18]. Instead of continuing to examine strategies that have been tried for disease prevention over the last 40 years, fresh approaches for disease prevention, stimulated by recent advances in our understanding of atopic dermatitis, are needed.

Recent advances

Be more tolerant

Although there is little doubt that some individuals with atopic dermatitis are truly allergic to substances such as house dust mite protein, longitudinal studies reveal allergen sensitization is probably a consequence, not a cause, of atopic dermatitis [19]. This idea is bolstered by findings that genetic syndromes defined by a loss of immune tolerance have eczema as a feature [20]. Consequently, instead of trying to rid the environment of allergens, maybe a better approach would be to try and induce tolerance by exposure to allergens or endotoxins at an early stage of immune development [13]. Peanut allergy might serve as a good model in this regard. In Israel for example, where peanut consumption is much higher than the UK, peanut allergy seems to be much less common [21], an observation that has stimulated a research group to test the hypothesis that introduction of peanuts into the diet in early life can reduce peanut allergy [22].

Gut parasites are another potentially interesting area to explore given that our immune system lived with them for millions of years before their relatively recent eradication. It is possible that this eradication of gut parasites has contributed to the increase in allergic disease due to insufficient immune stimulation of the right sort [23,24], and that the reintroduction of extracts from gut parasites in early life might tip the abnormally tilted atopic dermatitis immune response back into one of allergen tolerance [25].

Turning everything inside-out

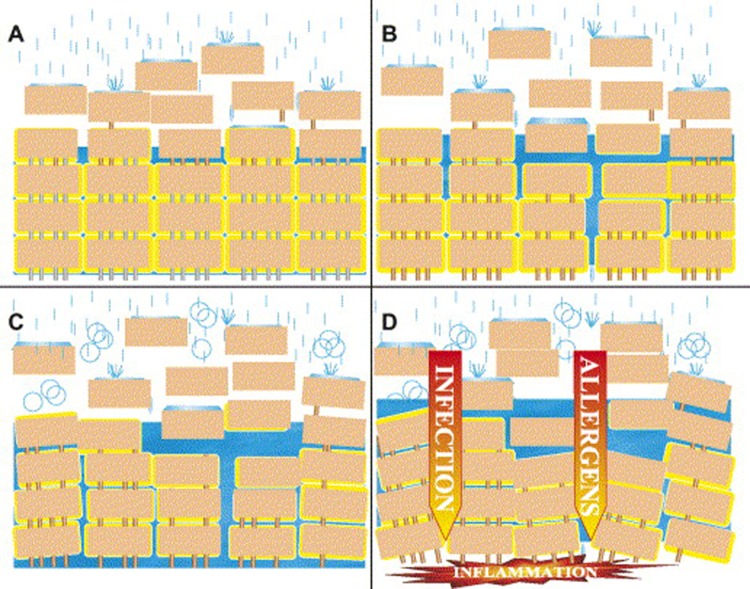

Research into the causes of atopic dermatitis has been dominated over the last 40 years by a preoccupation with allergy and the immune responses of the skin, gut, lungs and blood. Yet one of the hallmarks of atopic dermatitis is the presence of generally dry skin even in the absence of inflammation [26], an observation that stimulated researchers in Dundee to look at the genes that may be responsible for other dry skin conditions such as ichthyosis [10]. They found that mutations of genes that code for filaggrin – a key protein in the outer skin that maintains skin barrier function – are a strong predictor of atopic dermatitis, especially more severe, chronic atopic dermatitis and associated asthma [27,28]. So the world of atopic dermatitis research is turning its attention away from the inside of the body to the dry skin on the outside. We speculate that exposing children born with atopic dermatitis and defective skin barriers to frequent cleansing with alkaline soaps, bubble baths and shampoos leads to a breach of the skin barrier and low grade inflammation, which can then develop a life of its own through the process of autoimmunity [29,30], (figure 2). The defective skin barrier might also permit allergic sensitization to occur as allergens are introduced more easily to antigen presenting cells in the skin [31]. If this is true, then enhancing the skin barrier function in babies born to parents with allergic disease by limiting the assault of skin cleansers coupled with liberal use of emollients could prevent the development of atopic dermatitis and even the progression to asthma. Our Barrier Enhancement for Eczema Prevention (BEEP) pilot study has provided an encouraging signal, which our group now plans to test on a much larger scale [32]. It is likely that many new “designer” skin barrier repair products with various claims will emerge over the next 10 years [33,34]. Only large scale randomized controlled trials will definitely show whether they do any good, and whether they are any better than simple, cheaper emollients [35].

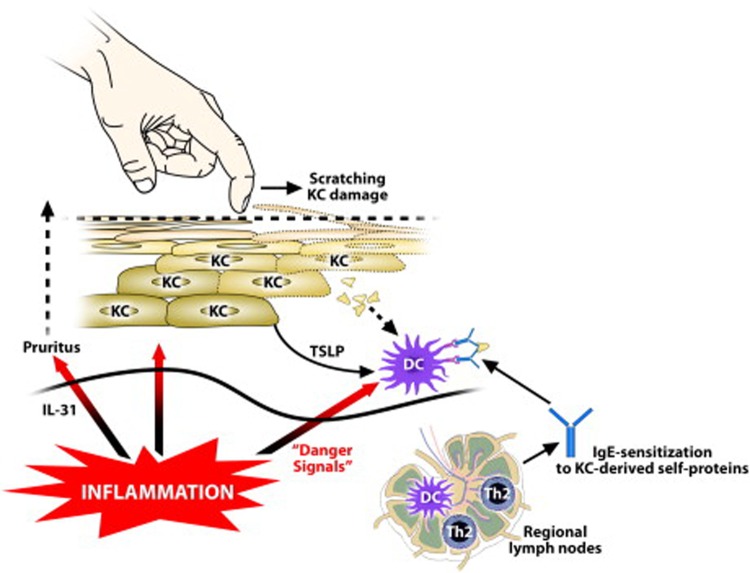

Figure 2. Mechanisms of IgE sensitization to epidermal self-proteins in patients with atopic dermatitis.

Inflammation induces pruritus through IL-31 production. Scratching results in cellular damage and release of membranous and intracellular compounds from keratinocytes (KC) and possibly other skin cells. The local dendritic cells (DC) subjected to thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) will induce a TH2 response and the generation of specific IgE directed against these self-proteins. IgE will bind to Fc ε RI on dendritic cells in the skin and thereby amplify the immune response and inflammatory reaction in the skin.

(Reproduced with permission from Tang TS, Bieber T, Williams HC. Does “autoreactivity” play a role in atopic dermatitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1209-1215)

Nip it in the bud

Even if atopic dermatitis cannot be prevented in the primary sense, it may still be possible to reduce disease severity through a strategy of early aggressive treatment when atopic dermatitis first appears. It is known that the constant scratching associated with atopic dermatitis may expose parts of skin to cells that can trigger an autoimmune response, which could result in a more widespread and persistent disease [30], (figure 3). So interrupting that chain of events by clamping down early on atopic dermatitis is an avenue worth exploring. Others have also suggested exploring disease modifying strategies in atopic dermatitis to break, stop or reverse atopic dermatitis and associated asthma, in a way that is heavily informed by biomarkers [36]. Other forms of secondary prevention such as “weekend” therapy (applying topical treatments for two consecutive days each week once the disease is under control) had been shown to have a large impact on reducing disease flares [37]. Whether the length and intensity of inducing the initial remission is important for long term control needs to be tested. The emergent theme seems to be one of not “chasing” atopic dermatitis but instead one of getting control then keeping control [38].

Figure 3. The brick wall analogy of the stratum corneum of the epidermal barrier.

In healthy skin the corneodesmosomes (iron rods) are intact throughout the stratum corneum. At the surface, the corneodesmosomes start to break down as part of the normal desquamation process, analogous to iron rods rusting (A). In an individual genetically predisposed to atopic dermatitis, premature breakdown of the corneodesmosomes leads to enhanced desquamation, analogous to having rusty iron rods all the way down through the brick wall (B). If the iron rods are already weakened, an environmental agent, such as soap, can corrode them much more easily. The brick wall starts falling apart (C) and allows the penetration of allergens (D).

(Reproduced with permission from Cork MJ, Robinson DA, Vasilopoulos Y, Ferguson A, Moustafa M, MacGowan A, Duff GW, Ward SJ, Tazi-Ahnini R. New perspectives on epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis: gene-environment interactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:3-21)

Future directions

Although atopic dermatitis prevention has not been a very fruitful area of research in the sense that the same interventions have been explored repeatedly and inconclusively [17], recent gene discoveries coupled with different ways of thinking about disease progression has produced new ideas for primary and secondary disease prevention [10,36]. The dry skin seen in atopic dermatitis, which has been recognized clinically yet largely ignored by science for many years [39], has undergone a sharp revival of interest with the discovery of mutations in the filaggrin gene. We predict this will result in studies that evaluate the potential protective effect of skin barrier enhancement in high-risk and even low-risk infants. Such intervention studies are not without their challenges. For example, defining a new case of atopic dermatitis as opposed to transient irritant eczema (which commonly occurs in infants) is tricky [40], as will be the problem of how to avoid contamination of a control group if word gets out that emollients from birth might prevent eczema. Selecting which emollient(s) have true barrier enhancement properties and those that are also acceptable for long term use for families whose babies do not appear to have a problem in the first place is also challenging, especially as, paradoxically, some emollients can impair rather than repair the skin barrier [41].

With regards to those studies that focus on inducing allergen tolerance at a young age, attention needs to be paid to the timing, amount and type of exposures to induce such tolerance and whether such tolerance leads to clinical benefit in terms of less atopic dermatitis and associated diseases. It is also unclear whether the conventional strategy of targeting a high risk population in atopic dermatitis prevention (children of parents who have atopic disease), is correct as such a policy could miss around 40% of potentially preventable cases if the same risk factors operate [42]. Perhaps it would be more cost-effective to adopt a whole population-based approach in countries with high levels of atopic dermatitis, although a much stronger evidence base would be required before such a public health approach could be entertained. Or perhaps the way forward is in the opposite direction, i.e. personalized medicine, so that prevention strategies for childhood disease are governed by genetic tests and biomarkers that determine disease risk. One thing is for certain, the whole field of atopic dermatitis prevention is exploding with new ideas. The biggest challenge will be to evaluate these ideas properly in large prospective randomized controlled trials.

Disclosures

Eric L Simpson has received a research grant from Galderma, who is the manufacturer of one of the emollients in the BEEP study. They had no involvement in the BEEP study.

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found at: http://f1000.com/prime/reports/m/4/24

References

- 1.Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF, Motala C, Ortega Martell JA, Platts-Mills TA, Ring J, Thien F, Van Cauwenberge P, Williams HC. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:832–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams HC. Atopic Dermatitis. N Eng J Med. 2005;352:2314–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Hulst AE, Klip H, Brand PL. Risk of developing asthma in young children with atopic eczema: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:565–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/1090231

- 4.Marenholz I, Bauerfeind A, Esparza-Gordillo J, Kerscher T, Granell R, Nickel R, Lau S, Henderson J, Lee YA. The eczema risk variant on chromosome 11q13 (rs7927894) in the population-based ALSPAC cohort: a novel susceptibility factor for asthma and hay fever. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2443–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spergel JM. From atopic dermatitis to asthma: the atopic march. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odhiambo J, Williams H, Clayton T, Robertson C, Asher MI, the ISAAC Phase Three Study group Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1251–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:67–73. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson B, Anderson HR, the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase One and Three Study groups Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? Journal Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;121:947–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cookson WO, Moffatt MF. The genetics of atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:383–7. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown SJ, McLean WH. One remarkable molecule: filaggrin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:751–62. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963731

- 11.Williams HC. Atopic eczema - why we should look to the environment. Br Med J. 1995;311:1241–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7015.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. Br Med J. 1989;299:1259–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flohr C, Yeo L. Atopic dermatitis and the hygiene hypothesis revisited. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2011;41:1–34. doi: 10.1159/000323290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963732

- 14.Flohr C, Johansson SGO, Wahlgren CF, Williams HC. How “atopic” is atopic dermatitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:150–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flohr C, Weiland SK, Weinmayr G, Björkstén B, Bråbäck L, Brunekreef B, Büchele G, Clausen M, Cookson WOC, von Mutius E, Strachan DP, Willams HC, the ISAAC Phase Two Study Group The role of atopic sensitization in flexural eczema: Findings from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase Two. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoare C, Li Wan Po A, Williams HC. Systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4(37):1–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foisy M, Boyle RJ, Chalmers JR, Simpson EL, Williams HC. The prevention of eczema in infants and children: an overview of Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews. Ev-Based Child Health. 2011;6:322–39. doi: 10.1002/ebch.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rautava S, Kainonen E, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Maternal probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and breast-feeding reduces the risk of eczema in the infant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris JM, Williams HC, White C, Moffat S, Mills P, Newman Taylor AJ, Cullinan P. Early allergen exposure and atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:698–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halabi-Tawil M, Ruemmele FM, Fraitag S, Rieux-Laucat F, Neven B, Brousse N, Prost Y de, Fischer A, Goulet O, Bodemer C. Cutaneous manifestations of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:645–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Toit G, Katz Y, Sasieni P, Mesher D, Maleki SJ, Fisher HR, Fox AT, Turcanu V, Amir T, Zadik-Mnuhin G, Cohen A, Livne I, Lack G. Early consumption of peanuts in infancy is associated with a low prevalence of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:984–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/1138943

- 22.Learning About Peanut Allergy – the LEAP study. [ http://www.leapstudy.co.uk/]

- 23.Mpairwe H, Webb EL, Muhangi L, Ndibazza J, Akishule D, Nampijja M, Ngom-wegi S, Tumusime J, Jones FM, Fitzsimmons C, Dunne DW, Muwanga M, Rodrigues LC, Elliott AM. Anthelminthic treatment during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of infantile eczema: randomised-controlled trial results. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:305–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963734

- 24.Flohr C, Tuyen LN, Quinnell RJ, Lewis S, Minh TT, Campbell J, Simmons C, Telford G, Brown A, Hien TT, Farrar J, Williams H, Pritchard DI, Britton J. Reduced helminth burden increases allergen skin sensitization but not clinical allergy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Vietnam. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:131–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erb KJ. Can helminths or helminth-derived products be used in humans to prevent or treat allergic diseases? Trends Immunol. 2009;30:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963735

- 26.Linde YW. Dry skin in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;177(Suppl Stockh):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baurecht H, Irvine AD, Novak N, Illig T, Bühler B, Ring J, Wagenpfeil S, Weidinger S. Toward a major risk factor for atopic eczema: meta-analysis of filaggrin polymorphism data. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1406–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963737

- 28.Rodríguez E, Baurecht H, Herberich E, Wagenpfeil S, Brown SJ, Cordell HJ, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Meta-analysis of filaggrin polymorphisms in eczema and asthma: robust risk factors in atopic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1361–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963738

- 29.Cork MJ, Robinson DA, Vasilopoulos Y, Ferguson A, Moustafa M, MacGowan A, Duff GW, Ward SJ, Tazi-Ahnini R. New perspectives on epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis: gene-environment interactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963739

- 30.Tang TS, Bieber T, Williams HC. Does “autoreactivity” play a role in atopic dermatitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cork MJ, Danby SG, Vasilopoulos Y, Hadgraft J, Lane ME, Moustafa M, Guy RH, Macgowan AL, Tazi-Ahnini R, Ward SJ. Epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1892–908. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963740

- 32.Centre of Evidence-Based Dermatology Barrier Enhancement Eczema Prevention (BEEP) Pilot Study. [ http://www.beepstudy.org/]

- 33.Elias PM, Wakefield JS. Therapeutic implications of a barrier-based pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011;41:282–95. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim BE, Leung DY. Epidermal barrier in atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012;4:12–16. doi: 10.4168/aair.2012.4.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller DW, Koch SB, Yentzer BA, Clark AR, O’Neill JR, Fountain J, Weber TM, Fleischer AB., Jr. An over-the-counter moisturizer is as clinically effective as, and more cost-effective than, prescription barrier creams in the treatment of children with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:531–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963741

- 36.Bieber T, Cork M, Reitamo S. Atopic dermatitis: a candidate for disease-modifying strategy. Allergy. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02845.x. Jun 4. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02845.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963742

- 37.Schmitt J, von Kobyletzki L, Svensson A, Apfelbacher C. Efficacy and tolerability of proactive treatment with topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors for atopic eczema: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:415–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963743

- 38.Williams HC. Preventing eczema flares with topical corticosteroids or tacrolimus: which is best? Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:231–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uehara M, Miyauchi H. The morphologic characteristics of dry skin in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1186–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1984.01650450068021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963745

- 40.Simpson E, Chalmers J, Keck L, Williams HC. How should an incident case of atopic dermatitis be defined? A systematic review of primary prevention studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danby SG, Al-Enezi T, Sultan A, Chittock J, Kennedy K, Cork MJ. The effect of aqueous cream BP on the skin barrier in volunteers with a previous history of atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:329–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://www.f1000.com/prime/717963746

- 42.Williams HC. Inflammatory Skin Diseases I: Atopic Dermatitis. In: Williams HC, Strachan DP, editors. The Challenge of Dermato-Epidemiology. Boca Raton: CRC Press Inc.: 1997. pp. 125–44. [Google Scholar]