Abstract

Given current constraints on universal treatment campaigns, recent advances in public health prevention initiatives have revitalized efforts to stem the tide of HIV transmission. Yet, despite a growing imperative for prevention—supported by the promise of behavioral, structural and biomedical approaches to lower the incidence of HIV—human rights frameworks remain limited in addressing collective prevention policy through global health governance. Assessing the evolution of rights-based approaches to global HIV/AIDS policy, this review finds that human rights have shifted from collective public health to individual treatment access. While the advent of the HIV/AIDS pandemic gave meaning to rights in framing global health policy, the application of rights in treatment access litigation came at the expense of public health prevention efforts. Where the human rights framework remains limited to individual rights enforced against a state duty bearer, such rights have faced constrained application in framing population-level policy to realize the public good of HIV prevention. Concluding that human rights frameworks must be developed to reflect the complementarity of individual treatment and collective prevention, this article conceptualizes collective rights to public health, structuring collective combination prevention to alleviate limitations on individual rights frameworks and frame rights-based global HIV/AIDS policy to assure research expansion, prevention access and health system integration.

Introduction

Throughout the evolution of HIV/AIDS policy, institutions of global health governance have looked to human rights in framing behavioral prevention and medical treatment initiatives. While leveraging rights-based policy to protect against coercive prevention measures and to hold governments accountable for pharmaceutical treatment access, individual human rights remain limited in guiding global efforts to promote population-level prevention policy. Given a rising imperative for HIV prevention—supported by the promise of behavioral, structural and biomedical approaches to lower the incidence of HIV and employ treatment as prevention—it is necessary to reframe the rights-based mantra of ‘treatment for all’ to include the collective rights of HIV-negative populations. Challenging the conventions of the discipline, this review contests the prevailing rights-based narrative in global HIV/AIDS policy, guiding a rights-based public health approach to ‘testing, treatment, and prevention for all’.

At the intersection of public health ethics and human rights law, this article analyzes the limited effects of individual human rights claims in supporting population-level HIV prevention efforts and conceptualizes a collective rights-based response to address public health prevention through global health policy. Bridging theory and policy, this interdisciplinary analysis provides a framework for research and practice across public health ethics and global health policy, advancing collective human rights frameworks to realize population-level HIV prevention initiatives. This article begins by reviewing the evolution of global health policy efforts to address the HIV/AIDS pandemic, chronicling a global response that originated from an emphasis on individual behavioral prevention, shifted to focus on individual access to treatment and has recently sought to combine individual access to treatment with population-level prevention. From this public health background, the authors examine the role of human rights in the HIV/AIDS response—with attention paid to the relative emphasis on treatment and prevention—employing archival research within the United Nations (UN) and World Health Organization (WHO) and legal analysis of global health governance to investigate three critical stages in the evolution of human rights law in global HIV/AIDS policy, (i) the birth of the health and human rights movement, (ii) the creation of international legal standards and (iii) the rise of national litigation to assure treatment access. The authors find that while the development of human rights originated from a normative focus on underlying determinants of HIV transmission, these efforts have been reframed through a litigation-driven effort to realize individual access to treatment. Where the human rights framework remains normatively limited to those individual rights enforced against a state duty bearer, such rights have faced constrained application in framing population-level prevention policy. With prevention necessitating collective rights, rights reflective of the public good of combination prevention, this analysis examines the effect of collective rights norms for the public’s health, concluding that such rights would support global health policy efforts to slow the spread of HIV through commitments for expanded research, access to prevention technologies and further integration of HIV prevention, treatment and care in health systems.

The Prevention Imperative

This section traces the evolution of HIV/AIDS policy in global health governance, encompassing the institutions that exercise predominant authority over global determinants of health (Szlezák et al., 2010). In examining this governance, the authors demonstrate how global HIV/AIDS policy has transitioned from a narrow focus on individual behavioral prevention against transmission, to an advocacy focus on individual access to biomedical treatment, and now, recognizing the limits of this individual treatment agenda, to an expanded focus on a combination of behavioral, structural and biomedical prevention at the population level. This prevention imperative calls into question the adequacy of the individual human rights paradigm to realize the highest attainable standard of health.

Building from the first reported cases of HIV, prevention held primacy in early efforts to develop global HIV/AIDS policy. With no medical response available in the period before clinical advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART), early responses to the growing pandemic were confined to behavioral prevention in the belief that testing, education and counseling—combined with initiatives to combat discrimination and provide condoms and clean needles—would drive self-interested behavioral change (Bertozzi et al., 2009). Although individual prevention initiatives predominated from the mid-1980s to early 1990s, resources for prevention faded as the public wearied, combination ARTs emerged and HIV was rebranded a chronic, manageable disease (Merson et al., 2008). As a result, global HIV policy shifted from prevention to treatment, driven by advocacy to respond to the dying individual regardless of the broader public health impact (Benatar et al., 2009). Beginning with the 1987 approval of zidovudine (AZT), scientific advancements gave lifesaving hope for universal HIV treatment; however, this hope was tempered by its restricted treatment efficacy and prohibitive cost, limitations extended through the 1996 introduction of combination therapy or HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) as the standard of care for people living with HIV. With the costs of treatment rendering therapies financially inaccessible for 90% of the HIV-positive world (WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, 2001), HIV remained a largely fatal diagnosis as infection rates climbed in developing countries, with Sub-Saharan Africa bearing the largest share of the global burden (UNAIDS, 2010a).

As the costs of treatment fell and antiretroviral options expanded, new institutions of global health governance emerged to ensure access to treatment and preservation of life – evolving through the 1997 launch of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); the 2000 adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and various declarations on HIV treatment; the 2001 UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS, creating the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; the 2003 support for the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in the United States and the 2003 start of the 3 by 5 Initiative through UNAIDS and WHO. Moved by the scale of the pandemic, developed nations came together in 2005 to endorse a foreign assistance commitment to attain universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support by the year 2010, a target subsequently endorsed by the UN General Assembly (UK Department for International Development and the G8 Presidency, 2005). Yet, while this goal of universal access has mobilized unprecedented resources for global health, such targets for access are increasingly out of reach, and, in the current economic climate, there are growing concerns that cutbacks in support may lead to a reversal of treatment gains (Moszynski, 2010; UNAIDS, 2011).

In the face of expanding global efforts to assure treatment, HIV prevalence has continued to grow in the last 15 years, with new HIV infections outpacing ART initiation and straining already over-burdened treatment distribution programs; for every two people initiating treatment, an estimated five new HIV infections occur (UN General Assembly, 2010). With an estimated 2.5 million people newly infected with HIV in 2011, bringing the total number of people living with HIV/AIDS to 34.2 million (UNAIDS, 2012), recent declines in HIV incidence have not been widely shared, with increasing infection rates among high-risk and marginalized populations, including commercial sex workers, men who have sex with men and injection drug users (Beyrer et al., 2012). Although more than 8 million people were receiving HIV treatment in low- and middle-income countries by the end of 2010 (rising from 6.6 million in 2010 and 5.255 million in 2009), only an estimated 54% of those in need currently have access, leaving at least 6.8 million who require treatment but are not receiving it (UNAIDS, 2012). Given that ‘medical and ethical considerations endow each patient currently on treatment with a life-long “entitlement” to receive at least his or her current treatment regimen’, many now consider HIV treatment efforts ‘unsustainable’ (Bongaarts and Over, 2010: 1359). With current standards focusing on longer treatment regimens, guaranteeing HAART and regular monitoring to ensure the continued efficacy of treatment, this standard of care (even with a steady reduction in drug costs) is often not available for those in resource-limited settings.

As global HIV/AIDS funding has declined, in parallel with decreases in other forms of development assistance, increases in cumulative lifetime HIV treatment costs have driven a widening gap between rising investment targets and shrinking financial commitments for HIV prevention, treatment and care (UNAIDS, 2009; UN General Assembly, 2010). Following a meteoric rise, HIV-specific funding has stagnated at 2008 levels, falling far short of estimates of US$22–24 billion in annual contributions necessary to achieve universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support by 2015 (Kates et al., 2012). These decreases in economic assistance are jeopardizing the global community’s ability to treat every HIV-positive person in the world and to meet commitments for a lifetime of treatment. As additional people begin first-line treatment—and are forced by drug resistance to progress to more expensive second- and third-line therapies—the growing costs of therapy, care and support will put treatment out of reach for an increasing share of the HIV-positive world (Boyd, 2010). Given current budgetary constraints, donors may soon reach an untenable retrogression at the intersection of global health and human rights, where they could be pressed to take away lifesaving treatment from those already on it. Faced with HIV incidence rising faster than treatment can begin, this inability to ‘treat our way out’ of the HIV pandemic has forced a return to prevention initiatives.

With an intensifying imperative for a shift in global health governance for HIV/AIDS, a number of initiatives have been developed in the last decade to investigate the promise of HIV prevention – that is, to reduce individual HIV transmission and societal HIV incidence (Auerbach et al., 2011; Padian et al., 2011). Operating at both the individual and population level, prevention engages with policy—as described below and delineated in Table 1—through a combination of behavioral, structural and biomedical approaches, including:

Behavioral approaches, involving an ‘attempt to motivate behavioral change within individuals and social units by use of a range of educational, motivational, peer-group, skills-building approaches and community normative approaches’ (Coates et al., 2008: 670), with encouraging developments in understanding the roles that multiple concurrent sexual partnerships play in spreading HIV (Mah and Halperin, 2010);

Structural approaches, involving an ‘aim to change the social, economic, political or environmental factors that determine HIV risk and vulnerability in specified contexts’ (Gupta et al., 2008: 766), with attention to law reforms and cash transfers (Baird et al., 2010) and

Biomedical approaches, involving individual ‘technological’ interventions that do not rely solely on behavior change to prevent HIV transmission (Padian et al., 2008: 586), with research showing groundbreaking advancement in the development of vaccines (Rerks-Ngarm et al., 2009), curative initiatives (Margolis, 2011), pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (Karim et al., 2010; Baeten et al., 2012), vaginal microbicides (Microbicide Trials Network, 2011), treatment as prevention (Cohen et al., 2011; HIV Prevention Trials Network, 2011) and voluntary adult male circumcision (Mills et al., 2008).

These prevention opportunities, particularly when comprehensively implemented as ‘combination prevention’, offer a potentially more cost-effective and sustainable pre-emptive HIV ‘response’ than routinizing testing and scaling-up treatment, the current norm in HIV programming.

Table 1.

Approaches to prevention interventions

| Behavioral approaches |

|

| Structural approaches |

|

| Biomedical approaches |

|

MSM, men who have sex with men; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

Under this newly revitalized prevention agenda, international organizations and national foreign assistance programs have incorporated prevention under global policies for ‘universal access’, drafting country-level prevention targets to complement those for treatment and care (Girard et al., 2010). At the forefront of global HIV/AIDS policy, UNAIDS and WHO strategies have set out to ‘revolutionize’ HIV prevention, calling for innovation and multisectoral efforts to scale-up prevention initiatives (UNAIDS, 2010b; WHO, 2010a). Heralding these initiatives ‘Treatment 2.0’, UNAIDS and WHO have sought this new approach to integrate prevention with treatment – to streamline the treatment process to ‘achieve and sustain universal access’ as well as to ‘maximize the preventive benefits of antiretroviral therapy’ (WHO and UNAIDS, 2011). In establishing the preventive benefits of therapy, global policy attention has turned to the effectiveness of scaling-up individual HIV treatment as a form of public health prevention, using this ‘test and treat’ model as a means to reduce HIV infectivity and limit the onward transmission of HIV (Cohen and Gay, 2010; Powers et al., 2011). Demonstrating the importance of this ‘test and treat’ model, recent studies have found that:

seropositive individuals on ART have viral loads six times lower than comparable individuals (Kilby et al., 2008),

the risk of transmission between serodiscordant couples is reduced 5-fold if the seropositive partner is on ART (Anglemyr et al., 2011) and

earlier initiation of ART can reduce HIV transmission by 96% in heterosexual serodiscordant couples (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2011).

Compounded by the recent biomedical successes of clinical prevention trials for male circumcision, vaginal microbicides and oral PrEP, policymakers are examining the relative prioritization of treatment and prevention in global HIV/AIDS policy (Baeten et al., 2010; Karim et al., 2010; University of Washington International Clinical Research Center, 2011). Despite this prevention agenda, HIV prevention continues to account for only 22% of all HIV/AIDS spending in low- and middle-income countries, with prevention strategies inadequately targeted to local contexts of HIV transmission (UNAIDS, 2010c). Under circumstances in which public health realities have led to a shift in global health governance, it becomes necessary to recalibrate human rights to reflect this growing imperative for targeted HIV prevention paradigms, re-conceptualizing human rights norms to consider public health frameworks for global HIV prevention policy.

Human Rights to Treatment over Prevention

Despite the evolution of a health and human rights movement in response to the HIV pandemic and the application of human rights in developing early HIV/AIDS policy, human rights obligations are rarely applied to frame current global HIV prevention efforts. Where HIV prevention policy is implemented, such public health interventions are framed on the basis of economic efficiency and political feasibility rather than under the aegis of human rights (Holmes et al., 2012). Where human rights fulfillment is considered, the right to health is applied overwhelmingly to individual treatment (Gruskin et al., 2007b). This section describes how rights-based global health governance developed normatively to create collective obligations for prevention but came to be implemented programmatically through an individual right to treatment.

Jonathan Mann and the Birth of the Health and Human Rights Movement

Reversing a history of neglect for human rights in international health debates, the advent of the HIV/AIDS pandemic would operationalize human rights for public health, as scholars and advocates looked explicitly to human rights in framing the global health response. As governments responded reflexively to this emergent threat through traditional public health policies—including compulsory testing, named reporting, travel restrictions and isolation or quarantine—human rights were seen as a reaction to intrusive public health infringements on individual liberty and a bond for stigma-induced cohesion among HIV-positive activists (Curran et al., 1987; Kirby, 1988; Bayer, 1991). In this period of heightened fear and emerging advocacy, Jonathan Mann’s tenure at WHO marked a turning point in the application of individual human rights to public health policy – viewing discrimination as counterproductive to public health goals, abandoning coercive tools of public health and applying human rights to focus on the individual risk behaviors leading to HIV transmission (Fee and Parry, 2008). Mann’s vocal leadership of WHO’s Global Programme on AIDS, launched in 1987, shaped formative efforts to create a rights-based framework for global health governance (Gruskin et al., 2007b). In the absence of medical treatment or biomedical prevention, global HIV/AIDS policy developed in opposition to both the historical biomedical framing of international health rights and the contemporaneous individualistic framing of neoliberal health policy (Wolff, 2012). Employing behavioral science to craft HIV prevention campaigns, WHO’s first Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of AIDS emphasized rights-based access to information, education and services as a means to support health autonomy and personal responsibility among vulnerable individuals (WHO, 1987), an approach subsequently followed in WHO public health guidelines and UN human rights reports (Centre for Human Rights, 1991). Drawn explicitly from this human rights framework, national risk reduction policies came to stress the need for interventions to respect and protect human rights as a means to achieve the individual behavior change that was thought to be necessary to reduce HIV transmission (WHO, 1988; Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, 1990; Mann and Tarantola, 1998). Although such rights-based discourses declined precipitously in global health governance following Mann’s contentious 1990 exit from WHO, Mann continued to develop this health and human rights movement in advocating for change in the global HIV response (Garrett, 1994).

Looking beyond individual behavior, Mann sought to advance the continuing promise of human rights in addressing underlying population-level determinants of health – viewing rights realization as supportive of ‘a broader, societal approach to the complex problem of human wellbeing’ (Mann, 1996: 924–925). With recognition of these underlying determinants of HIV, Mann cautioned that the disease would inevitably descend the social gradient, calling for rights-based consideration of socioeconomic, racial and gender disparities in abetting the spread of HIV (Mann, 1992). Through social scientific examination of the collective determinants of vulnerability to HIV infection—challenging the paradigm of complete individual control over health behaviors, a central premise of the individual rights framework—the health and human rights movement could shift from its early focus on the conflicts between public health goals and individual human rights (Scheper-Hughes, 1994; Gruskin et al., 1996). Out of this recognition of an ‘inextricable linkage’ between public health and human rights, Mann proposed a tripartite framework to describe the effects of (i) human rights violations on health, (ii) public health policies on human rights violations and (iii) human rights protection on public health promotion (Mann et al., 1999). Given this focus on population-level determinants of HIV vulnerability, Mann argued that ‘since society is an essential part of the problem, a societal-level analysis and action will be required’ (Mann, 1999: 222), calling for a rights-based agenda that would frame policies for the distribution of costly medical treatments while maintaining a commitment to prevention efforts focused on education, access to health services and a supportive social environment (Mann, 1997a,b). As advocates adopted this rights-based agenda as a means to frame public policy reforms, these discourses would take root in civil society—driven by transnational networks of public health and social justice advocates—and, despite Mann’s untimely death, would take hold of an emerging rights-based movement for global HIV/AIDS policy (Behrman, 2004).

International Legal Standards and Public Health Prevention

Negotiating conflicting agendas at the intersection of public health and human rights—torn between individual medical treatment for the present and collective disease prevention for the future—global health governance looked to human rights in developing global HIV/AIDS policy. Integrating human rights norms in HIV/AIDS partnerships, agendas and strategies, human rights would play an influential role in framing governmental, intergovernmental and non-governmental responses to the pandemic, including:

Governmental—the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) gave programmatic direction to rights-based HIV policy, framing national policies to assure dignity of HIV-positive individuals (Freedman, 1995).

Intergovernmental—the 1996 creation of UNAIDS, drawing on the 1994 Paris Declaration on Greater Involvement of People Living with HIV and AIDS, extended efforts to focus on the participation of affected communities in rights-based policy development and implementation (UNAIDS, 2000).

Non-governmental—the 1996 launch of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) encouraged rights-based scientific research through public-private partnerships for HIV prevention (Fauci, 2009).

Supported by human rights institutions through a series of AIDS-related resolutions in the UN Commission on Human Rights (1995), the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights sought in 1996 to advance International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights to elaborate the human rights implicated by both vulnerability to HIV and access to treatment (Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS, 1998).

Reflecting such rights-based developments in HIV policy, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights took up these evolving issues at the intersection of global health and human rights in 2000 in drafting its 14th General Comment on economic, social and cultural rights. Charged with drafting official interpretations of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Committee interpreted the ICESCR’s human right to ‘disease prevention, treatment and control’ to extend ‘not only to timely and appropriate health care but also to the underlying determinants of health’ (UN CESCR, 2000). In implementing this right through the tools of public health, General Comment 14 included specific state obligations for ‘the establishment of prevention and education programmes for behaviour-related health concerns such as sexually transmitted diseases, in particular HIV/AIDS…’ (UN CESCR, 2000). While acknowledging core obligations for the ‘provision of essential drugs’, the Committee explicitly cautioned that:

investments should not disproportionately favour expensive curative health services which are often accessible only to a small, privileged fraction of the population, rather than primary and preventive health care benefiting a far larger part of the population (UN CESCR, 2000).

Looking past individual behaviors and medical therapies, the Committee sought to realize a comprehensive ‘right to the enjoyment of a variety of facilities, goods, services and conditions’ through state obligations for underlying population-level determinants of health, assessed on the basis of their availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality (UN CESCR, 2000). With this analysis of underlying determinants of health moving beyond individual rights, recognizing state obligations to assist ‘communities’, ‘groups’ and ‘populations’, General Comment 14 notes that ‘States parties are bound by both the collective and individual dimensions of [the right to health]. Collective rights are critical in the field of health; modern public health policy relies heavily on prevention and promotion which are approaches directed primarily to groups’ (UN CESCR, 2000). In accordance with the interpretations of other human rights treaty bodies, the Committee’s application of human rights to the HIV/AIDS pandemic sought to de-emphasize individual treatment while recognizing the influence of public health prevention in addressing the interconnected population-level determinants of HIV transmission (UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, 1999; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2003). Extended by the 2001 UN General Assembly Special Session on AIDS, concretized in the 2002 revision of the International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights, and elaborated following the 2002 appointment of the first UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health, this rights-based approach to health was seen to be crucial in guiding and assessing HIV prevention, treatment, care and support for all (UN General Assembly, 2001; UN Commission on Human Rights, 2001; Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2002; Hunt, 2003).

However, as these comprehensive recommendations for underlying determinants of health required sweeping health systems reforms (expansive changes beyond the reach of many developing countries), HIV advocacy shifted from universal population-level prevention policy to feasible individual medical treatment through antiretroviral drugs (Berkman, 2001; London, 2002). Even as experts warned that this access to treatment agenda came at the expense of public health prevention programs, human rights litigation advanced popular efforts to realize individual access to treatment, providing an impactful means to hold states accountable for HIV/AIDS policy (De Cock et al., 2002; Gostin, 2004).

National Litigation and an Individual Right to Treatment

The normative evolution of human rights has catalyzed a burgeoning enforcement movement in global HIV/AIDS policy, empowering individuals to raise human rights claims in national courts. With global health policies emphasizing the importance of the law, legal recourse and public accountability, litigation has sought to rectify ‘policy gaps’ and ‘implementation gaps’ in national HIV/AIDS programs (Tarantola, 2000; Yamin, 2003). However, with this litigation often driven by HIV-positive activists, pressing to deliver medications as an immediate matter of life and death, this enforcement agenda has focused on treatment to the exclusion of prevention, neglecting long-term systemic challenges to address short-term medical imperatives and consequently distorting the rights-based response to HIV (Meier and Yamin, 2011).

Driving this litigation movement, the South African Supreme Court heard an early rights-based challenge for access to medicines in the seminal 2002 case Minister of Health v. Treatment Action Campaign (2002). Brought pursuant to South Africa’s constitutional codification of the human rights to life and health—providing positive obligations for the provision of health care—this legal challenge sought to overturn the national government’s unwillingness to expand its programs for the distribution of Nevirapine in reducing the vertical transmission of HIV from mother to child during childbirth. With this civil society-driven litigation led by the Treatment Action Campaign, a South African NGO focused on treatment for the HIV-positive, these advocates successfully held the South African government responsible for pharmaceutical access (Heywood, 2003).

Despite the origins of this rights-based litigation in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission, these rights-based cases would shift toward claims for access to individual treatment at the expense of policies for prevention systems (Hogerzeil, 2006; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2006). The Treatment Action Campaign’s successful claim for pharmaceutical prevention set a precedent for a wide range of claims for HIV treatment—developing under a ‘duty to rescue’ in ethical analysis and expanding across NGOs through legal advocacy (Pogge, 2007)—with these claims challenging the monopolistic practices of the international patent regime and seeking distributive justice through human rights litigation (Heywood, 2009). Recognizing the resource limitations of developing states, which were already seeking international assistance to meet domestic demands for treatment, this treatment access movement soon broadened to implicate international obligations on all manner of powerful states, organizations and corporations with the ability to support or impede access to ART in the developing world (Petchesky, 2003; Forman, 2007). In the wake of this paradigm shift, reconceptualizing pharmaceutical knowledge as a global public good, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights returned to these issues in 2006 in General Comment 17, re-interpreting the right to health to find that states ‘have a duty to prevent unreasonably high costs for access to essential medicines’ (UN CESCR, 2006). When the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health commented shortly thereafter, he found a ‘human right to medicines’ to form an ‘indispensible part’ of the right to health, holding that ‘states have to do all they reasonably can to make sure that existing medicines are available in sufficient quantities in their jurisdictions’ (Hunt, 2006).

Although scholars and advocates in the health and human rights movement have talked passionately about a human right of access to essential medicines, this debate on medicines has largely proved the limit of legal advocacy (Marks, 2009). Such a rights-based focus on access to health services has reduced the unit of analysis to the individual, advancing an individual right at the expense of collective health promotion and disease prevention programs through public health systems (Waitzkin, 2001). Although public health has come to appreciate underlying determinants of health, international human rights law has not kept pace with this societal understanding of health, advancing individual medical solutions to harms requiring collective societal change (Chapman, 2002). Operating without regard for national resource limitations and at the expense of universal public health measures, human rights litigation to realize the highest attainable standard of health for each individual has been criticized for resulting in programs that: promote selective medical care over primary health care, distort health policy in ways that take resources away from other public health threats, undermine national health equity through privileging legal judgments and entrench power rather than empowering the vulnerable (Easterly, 2009; Ferraz, 2009; Bernier, 2010). Where courts have been faced with challenges to public health systems—whether in water and sanitation systems, environmental health standards or HIV prevention programs—individual rights have proven largely impotent to affect change (Danchin, 2010; Westra, 2010). Despite theoretical efforts to address public goods under individual rights, holding that ‘individual human rights are characteristically exercised, and can only be enjoyed, through collective action’ (Donnelly, 2003: 25), such theoretical reasoning has not been translated into rights-based health policy (Tobin, 2012). With health rights creating at best ‘imperfect obligations’ (Sen, 2004), individual human rights cannot address societal determinants of HIV transmission. Notwithstanding the rights-based rhetoric that ‘universal access’ includes prevention as well as treatment, rights-based claims for access remain primarily focused on treatment, neglecting the rights-based accountability necessary for programmatic implementation of global HIV prevention policy (Gruskin and Tarantola, 2008; Novogrodsky, 2009). While AIDS is no longer considered exceptional, this human rights focus on treatment—to the detriment of prevention—is a public health anomaly that has distorted rights-based HIV/AIDS policy.

A Human Rights Basis for Prevention

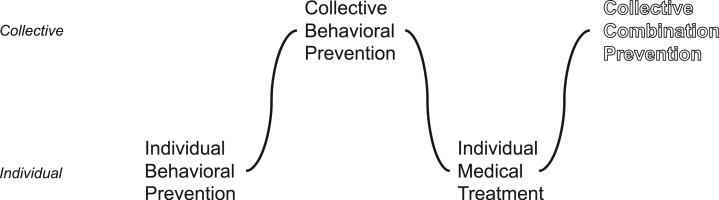

Where the health and human rights movement has been constrained in moving beyond access to treatment, this analysis finds that such limitations stem from an inability of human rights to speak with the collective voice through which HIV prevention must be heard. Enforced as an individual right against a state duty-bearer, these inherently limited, atomized rights have proven incomplete in creating accountability for public health prevention in global HIV/AIDS policy, impeding efforts to frame prevention interventions under human rights obligations (Lieberman, 1999; Chapman, 2002). With human rights in the global HIV/AIDS response developing from individual behavioral prevention to individual medical treatment, it becomes necessary for this unsteady evolution—as depicted in Figure 1—to encompass collective combination prevention.

Figure 1.

The evolution of human rights: shifting between individual and collective HIV policy.

Where scholars have contributed ethical arguments in positing moral commitments to shift global priorities from treatment to prevention (Brock and Wikler, 2009), there is a need to translate these ethical frameworks into legal obligations, building a human rights foundation for scaling-up prevention while maintaining the political commitments attendant to treatment (Barr et al., 2011). To bridge the growing disconnect between individual rights litigation and public health imperatives, human rights norms must incorporate collective rights to public health – rights of societies that can account for obligations to realize underlying, population-level determinants of HIV prevention through national health systems.

Collective rights operate in ways similar to individual rights; however, rather than seeking the empowerment of the individual, collective rights act at a societal level to assure the public goods that cannot be fulfilled through the absolutist mechanisms of individual entitlements. Where individual human rights examine ‘a separate isolated individual who, as such and apart from any social context, is bearer of rights’ (VanderWal, 1990), this vision of human rights, rooted in autonomy, has proven incapable of addressing public goods (Ruger, 2006; Parmet, 2009). As seen in the case of indigenous rights, wherein identity and culture cannot exist at an individual level, collective rights are seen as necessary to protect group entitlements and minority cultures (Freeman, 2011). Because these rights inhere in the collective, rather than with each individual member of the collective, they apply more readily to situations in which there is a group interest (or solidarity) in the substance of the right, with the realization of right determined at the population level (Newman, 2004). Thus, collective rights frameworks operate at a population level to address underlying determinants and assure public goods that can only be enjoyed in common with similarly situated individuals.

Although human rights were conceived following the Second World War as individual rights—with an individual rights-bearer left to make claims against a national duty-bearer (and thereby provide external restraint against a presumably tyrannical sovereign)—the rise of developing states and development debates has forced a re-examination of this individualistic conception of human rights (Otto, 1995; Donnelly, 2003). With collective rights originally advanced by the League of Nations but abandoned by the UN (as the elevation of group identity was thought to have supported the ethnic tensions that culminated in the Second World War), such collective rights were initially avoided in the development of the post-War human rights system (Van Dyke, 1982). However, with states maintaining a collective right to self-determination, this basis for “solidarity” rights would take root as developing nations became free from their colonial past, joined the UN and forced a re-examination of the individualistic conception of rights (Felice, 1996). Advancing collective rights anew in response to the economic development limitations of individual human rights frameworks, with developing states viewing traditional human rights frameworks as an extension of colonial domination, environmental health issues were quickly recognized as a group right (as a healthy environment can only be enjoyed with others) and were taken up as part of the movement for global justice through a New International Economic Order (Cornwall and Nyamu-Musembi, 2004). Drawing on this political basis in international relations, scholars and advocates have since put forward arguments for collective rights to, inter alia, development, environmental protection, humanitarian assistance, peace and common heritage (Marks, 2006).

As applied to public health, wherein public goods underlie health at a societal level, it has long been recognized in public health ethics that ‘public health and safety are not simply the aggregate of each private individual’s interest in health and safety . . . Public health and safety are community or group interests’ (Beauchamp, 1985: 29). More than the aggregate of each individual’s right, population-level prevention is a societal interest—a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts—requiring collective rights to hold duty bearers responsible to populations for the provision of public goods and necessitating positive action to provide societal access to behavioral, structural and biomedical prevention programs (Meier, 2007). With prevention serving as a public good, as disease prevention leads to ‘herd immunity’ and impacts entire societies, collective rights and their corollary implementation mechanisms become necessary to assure the policies required to provide for the tools and shared benefits of public health (Leonard, 2008). Linking ethical norms with international law, collective rights claims have shown themselves effective in responding to the health harms of a globalizing world, shifting the balance of power in international relations and creating widely recognized, if not completely realized, entitlements within the international community (Vandenhole, 2009). Such emerging rights provide a conceptual framework to develop global HIV prevention policy for the public’s health.

In framing rights-based tradeoffs in the relative support of treatment and prevention in global HIV/AIDS policy, collective rights can prove a means to negotiate competing ethical frameworks for individual capability, health equity and public health utility:

At an individual level, collective rights can address health capability through prevention interventions, empowering individuals vulnerable to infection—particularly high-risk and marginalized populations, including the young, women, men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users and commercial sex workers—to control their own health without relying on their partners to remove the threat of HIV (Gupta et al., 2008; Ruger, 2010).

Moving from individual agency to population-level agency, collective rights can assure equity, reducing unjust health disparities across groups by focusing not simply on the number of individuals on treatment but on the demographic distribution of prevention (and treatment as prevention) across populations, elevating distributive justice under a collective unit of analysis (London, 2007).

At a societal level, collective rights can maximize public health utility, with prevention serving as a public good – protecting all of society by: blunting the chain of HIV infection; reducing burdens of mortality and morbidity through increased herd immunity, decreased drug resistance and improved treatment efficacy; and bolstering productivity among the healthy population in caring for a smaller infected population (Labonte and Schrecker, 2007).

Where individual rights are incapable of securing the public good of disease prevention, incapable of addressing the rights of those who are not infected and are not yet suffering, the collective enjoyment of public health can be seen as a pre-condition for the individual human right to health, enabling disease prevention that can only be achieved at a population level. With public health prevention addressing collective determinants of health outside the control of the individual, recognizing the embeddedness of individuals within their societies, collective rights can support population-level health benefits for the common good.

Thus, collective rights to public health can uphold moral commitments, support ethical norms and provide legal frameworks for asserting HIV prevention as a state obligation, with international and non-state obligations arising where the state is unable or unwilling to assert its authority to control the spread of HIV (Skogly, 2006). Implemented through the political support for collective rights among developing states and buttressed by the normative legitimacy of human rights in global health governance, such an approach could be codified in international law and incorporated into political advocacy for HIV prevention, framing institutional reforms, budgetary commitments and accountability mechanisms in national policy, international organizations and public–private partnerships. Operating at both domestic and global levels, such collective rights would empower states to seek or provide international assistance and cooperation for HIV prevention in accordance with their respective abilities, meeting global public health goals through national health systems and monitoring national-level epidemiologic indicators through human rights treaty bodies. As with other rights-based movements, the interplay between legal developments and social justice advocacy would create mutually reinforcing accountability mechanisms in securing the progressive realization of collective rights for HIV prevention (Yamin and Gloppen, 2011).

Such a collective lens would best support the rights-based approach advocated by those who have proposed early treatment as a means to the public health benefits of prevention:

Expanded HIV testing and immediate treatment would offer opportunity for highest quality positive prevention, a holistic approach that protects the physical, sexual, and reproductive health of individuals with HIV, and maximally reduces onward transmission. Provided coercion is avoided and confidentiality and dignity maintained, individual health and societal safety should benefit through reduced HIV transmission, which would enhance human rights overall (De Cock et al., 2009).

Although concerns have been voiced that such a ‘test and treat’ model would pose the risk of individual human rights violations (Rennie and Behets, 2006), particularly as routinized HIV testing has become the consensus recommendation of global health policymakers (Jurgens et al., 2009; Amon, 2010), the preponderance of policy debate has surrounded the prospect of collective benefits from public health prevention, contemplating the programmatic feasibility of early treatment to lower HIV infectivity and thereby reduce the societal incidence of HIV (Bayer and Edington, 2009; Zachariah et al., 2011).

Yet, despite the collective advantages of the ‘test and treat’ approach, this model leaves out the rights of those who are not HIV-positive, denying them the capability to prevent their own infection and thus stem the tide of the HIV pandemic. If collective rights are to frame a means to testing, treatment and prevention for all, global health governance must assure that societies can come together to produce the public good of prevention and reduce the incidence of HIV toward zero – normalizing ‘opt-out’ HIV testing, reducing stigma and increasing health system utilization through both treatment (for those who are positive) and prevention (for those who are negative).

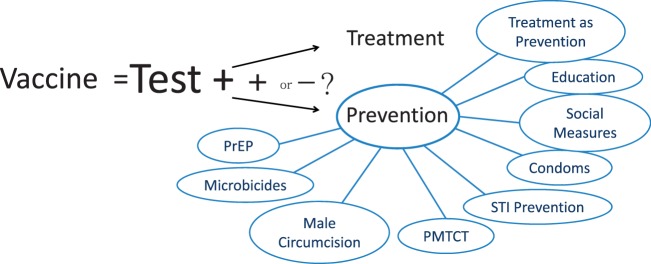

In operationalizing collective rights to public health for the progressive reduction of HIV transmission, the most obvious approach would be to develop a vaccine and distribute it to all those who are HIV-negative. Such a vaccine would promote equitable societal-level protection against disease while placing few continuing demands on national health systems (Andre et al., 2008). Similar to the eradication of smallpox, a universal vaccination campaign, supporting the public good of disease eradication, would be uniquely conducive to a collective rights-based approach to prevention. However, in a world without the immediate prospect of a vaccine (Johnston and Fauci, 2008), the most realistic operationalization of collective rights would be—as diagrammed in Figure 2—the expansion of HIV testing as a universal gateway to the holistic combination of individual treatment and collective combination prevention.

Figure 2.

The rights-based equivalency of universal vaccination to universal treatment and collective combination prevention.

Implemented comprehensively, viewing treatment as both beneficial to the individual and preventative for the collective, such an approach would be the rights-based equivalent of vaccination – with each prevention intervention only partially effective but together serving as a more perfect societal barrier against a rise in HIV incidence (Hankins and de Zalduondo, 2010). Providing rights-based frameworks by which combination prevention interventions are appropriate to the epidemiology, social context and resources of the nation (Auerbach et al., 2011), collective rights can facilitate accountability to assure that prevention interventions are available, accessible, acceptable and of sufficient quality. To assure such country-specific scale-up of HIV testing, treatment and prevention, the implementation of collective rights through global prevention policy will become crucially important as research advances, technologies are distributed and national health systems expand for HIV prevention.

A Rights-Based Approach to Global Prevention Policy

With HIV prevention both a public health and a human rights imperative, human rights law must frame global health governance to integrate prevention policy as central to the universal access agenda. A collective rights-based approach can address deficiencies in global health policy for HIV prevention, facilitating the public’s health through a rights-based approach to: supporting HIV prevention research, financing and allocating effective HIV prevention technologies and incorporating HIV prevention in primary health care systems.

Expanded Research

Until a cure is found, prevention research will remain necessary to develop the behavioral, structural and biomedical interventions essential to reducing the incidence of HIV. With scientifically-grounded optimism that such prevention research will soon yield success—driven by a recent spate of encouraging results from large-scale clinical trials—an expansion of research will be critical to assuring international assistance and cooperation for rights-based approaches to HIV prevention (UNAIDS, 2011). However, HIV prevention trials have presented novel governance challenges to the evolution of international ethical standards, stymieing the progression of clinical studies necessary to sustain research on HIV transmission (Haire et al., 2012). In carrying out this research, by necessity among vulnerable high-risk populations in the developing world, it is necessary that host countries build capacity to approve and facilitate HIV prevention research with the support of affected communities (Milford et al., 2006). To understand the synergistic benefits of treatment and prevention, establishing a new standard of care for those taking part in HIV prevention trials, investments are necessary to develop ‘multiple intervention studies’ on combination HIV prevention – collectively examining behavioral, structural and biomedical (vaccine and non-vaccine) prevention at a societal level (Auerbach et al., 2011).

With prevention research currently on the rise, collective rights can assure that such research not look simply at individual clinical trials in isolation, but extend the beneficial results of previous clinical research by examining multiple intervention results at a societal level. While biomedical prevention has theoretical allure, given recent proof-of-concept results—for PrEP, microbicides and treatment as prevention—additional randomized controlled trials will be necessary to establish societal-level and context-specific efficacy, feasibility and cost-effectiveness (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2009). In facilitating these trials through collective rights, institutional partnerships between developed and developing country actors can prove instrumental in developing the sustainable public health benefits of international clinical research, overcoming regulatory challenges to research approval in developing countries and informing the ethical norms of HIV prevention research (Mills et al., 2006; Lagakos and Gable, 2008). For example, with individual rights frameworks considering only the risks and benefits to the research subject, rights-based regulations disadvantage HIV prevention research where placebo-controlled trials are necessary to understand combination prevention at a societal level (Rennie and Sugarman, 2010). Through the development of ethical standards of informed consent for those who are HIV-negative, collective rights would allow for research approval processes that consider the societal benefits of research (London et al., 2012). Assuring that such research benefits the intended communities, research populations can employ collective rights to assert an international obligation to allow active community participation in designing prevention research relevant to the lives of research subjects. With local consultations among all stakeholders (to understand, approach and navigate the ethical standards of the communities in which placebo-controlled studies are undertaken), the considerations of affected communities can translate international ethical standards to reflect local realities (UNAIDS, 2011). To guarantee such rights-based prevention research, global health governance must overcome these challenges to HIV prevention through frameworks that facilitate research review, establish a context-specific standard of care for affected communities and build research capacity through country coordination mechanisms for combination prevention research and community prevention access.

Prevention Access

To guarantee access to the benefits of this research, international commitments will be necessary for the distribution of successful prevention interventions. As with other global health interventions, research developments are not always accompanied by ‘clear governance arrangements to ensure that they are affordable or available to people who need them’ (Moon, 2009). This is particularly acute in HIV prevention research, where, even in the example of the test and treat model, no rights-based frameworks have been developed to govern how developed states, international organizations and industries will commit to providing access to prospective prevention interventions (Gostin and Kim, 2011). Where current international commitments have focused on treatment to the detriment of prevention (Piot et al., 2008; Brock and Wikler, 2009), future financing mechanisms will be necessary to support the distribution of HIV prevention (Hecht et al., 2010; Meyer-Rath and Over, 2012). While a collective rights-based approach will necessarily involve funding tradeoffs, bearing the immeasurable cost of individual lives lost for the societal benefit of public health prevention, such tradeoffs will be essential to assuring the conditions underlying HIV protection for all.

If developed through the international obligations inherent in collective rights, global public-private partnerships could more efficiently incentivize innovation and dissemination of HIV prevention. Operating at the intersection of rights to public health prevention and rights to ‘enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications’, these intersectional collective rights obligations can galvanize international commitments and empower political movements to prioritize prevention access over intellectual property (Forman, 2008). With individual health-related rights unable to support entitlements for those who are not unhealthy, collective rights could better frame the population-level needs of societies and the international obligations on developed nations. Implemented programmatically through advanced market commitments and health impact funds, such product development partnerships can overcome uncertain commercial returns that limit private investment in HIV prevention while employing non-exclusive royalty contracts to ensure that innovations are accessible in those developing nations that bear the burdens of intervention development (Koff, 2010). Through such rights-based mechanisms, breakthroughs in behavioral, biomedical and structural prevention can be distributed under the mantle of collective rights, with these rights framing the rollout of HIV prevention interventions through national health systems.

Health Systems

The implementation of such prevention distribution will require the revitalization of sustainable national primary health care systems. Long programmatized in isolation from systems for sexual and reproductive health, HIV policy implementation is inhibited by an absence of systemic infrastructures for the targeting, selection and delivery of prevention interventions (Bertozzi et al., 2008). With the weakening of health systems and workforce resources limiting HIV testing and treatment (Schneider et al., 2006), health system strengthening will be necessary to undertake interdependent interventions for universal testing, treatment and prevention – further integrating these services to sustain funding for all (Rasschaert et al., 2011). Additionally, given that combination prevention will require regular testing of HIV status, sexual education to address HIV risk factors and administration of biomedical prevention through health care services—interventions that remain inadequate in many developing nations—the distribution of prevention interventions must account for the scaling-up of health systems to assure universal access and the structural reforms to facilitate underlying determinants of HIV prevention (Veenstra and Whiteside, 2009; Global Commission on HIV and the Law, 2012).

As human rights are employed to frame the development of health systems, a collective right to HIV prevention would take the AIDS response ‘out of isolation’, integrating new and existing technologies for HIV treatment and prevention within the context of structural reforms for the public’s health (Sidibé and Buse, 2009). Despite recent acknowledgement that health system strengthening and horizontal integration are necessary for an effective response to AIDS, this health systems agenda has been unable to ground itself in a human rights foundation or to raise the international obligations necessary to prevent and reverse the harms of health system retrenchment through international assistance and cooperation (Backman et al., 2008). With global HIV/AIDS policies and funding resulting in parallel agendas for HIV and larger issues of sexual and reproductive health under individual rights frameworks, a collective right to prevention can support the integration of vertical HIV prevention efforts in horizontal sexual and reproductive health systems, viewing health systems as a public good to be realized at a societal level (Anomaly, 2011). Examining societal public health indicators rather than individual disease-specific interventions (Salomon et al., 2007), the ‘implementation science of HIV prevention’ will be key to this integration of HIV prevention efforts into broader health systems (Piot et al., 2008). Despite the complexity of horizontal health initiatives, governance structures and funding mechanisms in developing nation contexts, global health planners and programmers must achieve optimal programmatic functioning when bringing programs to scale, particularly in countries with weak and fragmented health systems and workforces. Similar to the scale-up of systems for HIV treatment under the individual right to health (Gruskin et al., 2007a), a collective rights-based approach can frame obligations for the development of systems to deliver HIV prevention interventions, focusing on underlying societal determinants of health and assessing population-level epidemiologic result over medical service provision.

Conclusions

With human rights bearing a central role in the global HIV/AIDS response, collective rights can reframe the obligations of global health governance, projecting a vision of greater justice by addressing the public’s health through HIV prevention. Where global health governance has begun to debate the disproportionate funding targeted at individual HIV treatment—shifting from a treatment agenda elevated by rights-based advocates to a more pragmatic distribution between treatment and prevention—human rights practitioners have an opportunity to apply rights-based frameworks in this evolution of global HIV/AIDS policy. By engaging collective rights to public health, human rights can continue to protect populations vulnerable to HIV infection and structure holistic HIV/AIDS policy to ensure testing, treatment and prevention for all.

Funding

This research was supported by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program P30 AI50410.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Professors Ronald Bayer, Lawrence Gostin, Ashley Fox, Stuart Rennie and Myron Cohen for their insightful comments on previous drafts of this article; to the University of North Carolina’s Center for AIDS Research for supporting this research on global HIV/AIDS policy; and to Columbia University’s Center for the History and Ethics of Public Health for providing the space and support to develop this article.

References

- Amon J. HIV Treatment as Prevention—Human Rights Issues. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13(Suppl. 4):O15. [Google Scholar]

- Andre F E, Booy R, Bock H L, Clemens J. Vaccination Greatly Reduces Disease, Disability, Death and Inequity Worldwide. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86:140–146. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.040089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglemyr A, Rutherford G, Baggaley R, Egger M, Siegfried N. Antiretroviral Therapy for Prevention of HIV Transmission in HIV-Discordant Couples. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009153.pub2. Issue 8. Art. No.: CD009153, available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009153.pub2/pdf [accessed 12 November 2012] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anomaly J. Public Health and Public Goods. Public Health Ethics. 2011;4:251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach J D, Parkhurst J O, Cáceres C F. Addressing Social Drivers of HIV/AIDS for the Long-Term Response: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. Global Public Health. 2011;6:S293–S309. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.594451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman G, Hunt P, Khosla R, Jaramillo-Strouss C, Fikre B M, Rumble C, Pevalin D, Páez D A, Pineda M A, Frisancho A, Tarco D, Motlagh M, Farcasanu D, Vladescu C. Health Systems and the Right to Health: An Assessment of 194 Countries. Lancet. 2008;372:2047–2085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61781-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten J M, Donnell D, Kapiga S H, Ronald A, John-Stewart G, Inambao M, Manongi R, Vwalika B, Celum C, Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team. Male Circumcision and Risk of Male-to-Female HIV-1 Transmission: A Multinational Prospective Study in African HIV-1 Serodiscordant Couples. AIDS. 2010;24:737–744. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833616e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten J, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo N, Campbell J, Wangisi J, Tappero J W, Bukusi E A, Cohen C R, Katabira E, Ronald A, Tumwesigye E, Were E, Fife K H, Kiarie J, Farquhar C, John-Stewart G, Kakia A, Odoyo J, Mucunguzi A, Nakku-Joloba E, Twesigye R, Ngure K, Apaka C, Tamooh H, Gabona F, Mujugira A, Panteleeff D, Thomas K K, Kidoguchi L, Krows M, Revall J, Morrison S, Haugen H, Emmanuel-Ogier M, Ondrejcek L, Coombs R W, Frenkel L, Hendrix C, Bumpus N N, Bangsberg D, Haberer J E, Stevens W S, Lingappa J R, Celum C, Partners PrEP Study Team. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird S, Chirwa E, McIntosh C, Özler B. The Short-Term Impacts of a Schooling Conditional Cash Transfer Program on the Sexual Behavior of Young Women. Health Economics. 2010;19:55–68. doi: 10.1002/hec.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr D, Amon J J, Clayton M. Articulating a Rights-Based Approach to HIV Treatment and Prevention Interventions. Current HIV Research. 2011;9:396–404. doi: 10.2174/157016211798038588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer R. Public Health Policy and the AIDS Epidemic. An End to HIV Exceptionalism? New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324:1500–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105233242111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer R, Edington C. HIV Testing, Human Rights, and Global AIDS Policy: Exceptionalism and its Discontents. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2009;34:301–323. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2009-002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp D. Community: The Neglected Tradition of Public Health. Hastings Center Report. 1985;15:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman G. The Invisible People: How the U.S. Has Slept through the Global AIDS Pandemic, the Greatest Humanitarian Catastrophe of Our Time. New York: The Free Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Benatar S R, Gill S, Bakker I. Making Progress in Global Health: The Need for New Paradigms. International Affairs. 2009;85:347–371. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman A. Confronting Global AIDS: Prevention and Treatment. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1348–1349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier L. International Socio-Economic Human Rights: The Key to Global Health Improvement. International Journal of Human Rights. 2010;14:246–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi S M, Laga M, Bautista-Arredondo S, Coutinho A. Making HIV Prevention Programmes Work. Lancet. 2008;372:831–844. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi S M, Martz T E, Piot P. The Evolving HIV/AIDS Response and the Urgent Tasks Ahead. Health Affairs. 2009;28:1578–1590. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Baral S D, van Griensven F, Goodreau S M, Chariyalertask S, Wirtz A L, Brookmeyer R. Global Epidemiology of HIV Infection in Men Who Have Sex With Men. Lancet. 2012;380:367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J, Over M. Global HIV/AIDS Policy in Transition. Science. 2010;328:1359–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.1191804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M A. Current and Future Management of Treatment Failure in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Current Opinion in HIV & AIDS. 2010;5:83–89. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328333b8c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock D W, Wikler D. Ethical Challenges in Long-Term Funding for HIV/AIDS. Health Affairs. 2009;28:1666–1676. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Human Rights. Report of an International Consultation on AIDS and Human Rights, Geneva, 26–28, 1989. New York: United Nations Organization; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman A. Core Obligations Related to the Right To Health. In: Chapman A, Russell S, editors. Core Obligations: Building a Framework for Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Oxford: Intersentia; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Coates T J, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural Strategies to Reduce HIV Transmission: How to Make Them Work Better. Lancet. 2008;372:669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M S, Chen Y Q, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour M C, Kumarasamy N, Hakim J G, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto J H, Godbole S V, Mehendale S, Chariyalertsak S, Santos B R, Mayer K H, Hoffman I F, Eshleman S H, Piwowar-Manning E, Wang L, Makhema J, Mills L A, de Bruyn G, Sanne I, Eron J, Gallant J, Havlir D, Swindells S, Ribaudo H, Elharrar V, Burns D, Taha T E, Nielsen-Saines K, Celentano D, Essex M, Fleming T R, HPTN 052 Study Team Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M S, Gay C L. Treatment to Prevent Transmission of HIV-1. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;50(Suppl. 3):S85–S95. doi: 10.1086/651478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall A, Nyamu-Musembi C. Putting the “Rights-Based Approach” to Development into Perspective. Third World Quarterly. 2004;25:1415–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Curran W J, Clark M E, Gostin L. AIDS: Legal and Policy Implications of the Application of Traditional Disease Control Measures. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 1987;15:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1987.tb01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danchin P. A Human Right to Water? The South African Constitutional Court’s decision in the Mazibuko Case. European Journal of International Law. 2010 available from: http://www.ejiltalk.org/a-human-right-to-water-the-south-african-constitutional-court%E2%80%99s-decision-in-the-mazibuko-case/ [last accessed 26 November 2012] [Google Scholar]

- De Cock K M, Gilks C F, Lo Y, Guerma T. Can Antiretroviral Therapy Eliminate HIV Transmission? Lancet. 2009;373:7–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61732-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cock K M, Mbori-Ngacha D, Marum E. Shadow on the Continent: Public Health and HIV/AIDS in Africa in the 21st Century. Lancet. 2002;360:67–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly J. Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2003. pp. 1–2600. [Google Scholar]

- Easterly W. Financial Times. 2009. Human Rights are the Wrong Basis for Healthcare. 12 October, available from: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/89bbbda2-b763-11de-9812-00144feab49a.html#axzz2C2UtmAUh [last accessed 12 November 2012] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci A. A Living History of AIDS Vaccine Research. IAVI Report. 2009;13:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fee E, Parry M. Jonathan Mann, HIV/AIDS, and Human Rights. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2008;29:54–71. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felice W F. Taking Suffering Seriously: The Importance Of Collective Human Rights. New York: SUNY Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz O L M. The Right to Health in the Courts of Brazil: Worsening Health Inequities? Health and Human Rights. 2009;11:33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman L P. Reflections on Emerging Frameworks of Health and Human Rights. Health and Human Rights. 1995;1:314–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. Human Rights: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forman L. Trade Rules, Intellectual Property, and the Right to Health. Ethics and International Affairs. 2007;21:337–357. [Google Scholar]

- Forman L. Rights’ and Wrongs: What Utility for the Right to Health in Reforming Trade Rules on Medicines? Health and Human Rights: An International Journal. 2008;10:37–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett L. The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Girard F, Ford N, Montaner J, Cahn P, Katabira E. Universal Access in the Fight Against HIV/AIDS. Science. 2010;329:147–149. doi: 10.1126/science.1193294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Commission on HIV and the Law. Risks, Rights & Health. New York: UNDP; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L O. The AIDS Pandemic: Complacency, Injustice and Unfulfilled Expectations. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L O, Kim S C. Ethical Allocation of Preexposure HIV Prophylaxis. JAMA. 2011;305:191–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin S, Ferguson L, Bogecho D O. Beyond the Numbers: Using Rights-Based Perspectives to Enhance Antiretroviral Treatment Scale-up. AIDS. 2007a;21:S13–S19. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298098.71861.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin S, Hendriks A, Tomasevski K. In AIDS in the World II. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. Human Rights and Responses to HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin S, Mills E J, Tarantola D. History, principles, and practice of health and human rights. Lancet. 2007b;370:449–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin S, Tarantola D. Universal Access to HIV Prevention, Treatment and Care: Assessing the Inclusion of Human Rights in International and National Strategic Plans. AIDS. 2008;22:S123–S132. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327444.51408.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta G R, Parkhurst J O, Ogden J A, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural Approaches to HIV Prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haire B, Kaldor J, Fordens C F C. How Good is “Good Enough”? The Case for Varying Standards of Evidence According to Need for New Interventions in HIV Prevention. American Journal of Bioethics. 2012;12:21–30. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2012.671887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankins C S, de Zalduondo B O. Combination Prevention: A Deeper Understanding of Effective HIV Prevention. AIDS. 2010;24:S70–S80. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000390709.04255.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht R, Stover J, Bollinger L, Muhib F, Case K, de Ferranti D. Financing of HIV/AIDS Programme Scale-up in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries, 2009—31. Lancet. 2010;376:1254–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61255-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heywood M. Current Developments Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission in South Africa: Background, Strategies and Outcomes of the Treatment Action Campaign Case Against the Minister of Health. South African Journal on Human Rights. 2003;19:278–315. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood M. South Africa's Treatment Action Campaign: Combining Law and Social Mobilization to Realize the Right to Health. Journal of Human Rights Practice. 2009;1:14–36. [Google Scholar]

- HIV Prevention Trials Network. HPTN 052: A Randomized Trial to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Antiretroviral Therapy Plus HIV Primary Care Versus HIV Primary Care Alone to Prevent the Sexual Transmission of HIV-1 in Serodiscordant Couples. 2011. available from: http://www.hptn.org/research_studies/hptn052.asp [accessed 12 November 2012] [Google Scholar]

- Hogerzeil H V. Essential Medicines and Human Rights: What Can They Learn From Each Other? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006;84:1–5. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.031153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Blandford J, Sangrujee N, Stewart S, DuBois A, Smith T R, Martin J C, Gavaghan A, Ryan C A, Goosby E P. PEPFAR’S Past and Future Efforts to Cut Costs, Improve Efficiency, and Increase the Impact of Global HIV Programs. Health Affairs. 2012;31:1553–1560. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P. Report on Right to Health Indicators; Good Practices for the Right to Health; HIV/AIDS and the Right to Health; Neglected Diseases, Leprosy and the Right to Health; an Optional Protocol to ICESCR. New York: United Nations; 2003. A/58/427, 10 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P. Promotion and Protection of Human Rights: Human Rights Questions, Including Alternative Approaches for Improving the Effective Enjoyment of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. New York: United Nations; 2006. UN Document A/61/338. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M I, Fauci A S. An HIV Vaccine–Challenges and Prospects. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:888–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Courting Rights: Case Studies in Litigating the Human Rights of People Living with HIV. Geneva: Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network and the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens R, Cohen J, Tarantola D, Heywood M, Carr R. Universal Voluntary HIV Testing and Immediate Antiretroviral Therapy. Lancet. 2009;373:1079. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim Q A, Karim S S, Frohlich J A, Grobler A C, Baxter C, Mansoor L E, Kharsany A B M, Sibeko S, Mlisana K P, Omar Z, Gengiah T N, Maarschalk S, Arulappan N, Mlotshwa M, Moris L, Taylor D. CAPRISA 004 Trial Group. Effectiveness and Safety of Tenofovir Gel, and Antiretroviral Microbicide, for the Prevention of HIV Infection in Women. Science. 2010;329:1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates J, Wexler A, Lief E, Gobet B. Financing the Response to AIDS in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: International Assistance From Donor Governments in 2011. 2012. July 2012 Report, Kaiser Family Foundation and UNAIDS, available from: http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7347-08.pdf [accessed 12 November 2012] [Google Scholar]

- Kilby J, Lee H, Hazelwood J, Bansal A, Bucy R, Saag M, Shaw G M, Acosta E P, Johnson V A, Perelson A S, Goepfert P A, UAB Acute Infection, Early Disease Research Program (AIEDRP) Group Treatment Response in Acute/Early Infection Versus Advanced AIDS: Equivalent First and Second Phases of HIV RNA Decline. AIDS. 2008;22:957–962. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282fbd1da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby M. The New AIDS Virus—Ineffective and Unjust Laws. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1988;1:305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koff W C. Accelerating HIV Vaccine Development. Nature. 2010;464:161–162. doi: 10.1038/464161a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labonte R, Schrecker T. Globalization and Social Determinants of Health: Promoting Health Equity in Global Governance. Globalization and Health. 2007;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagakos S W, Gable A. Methodological Challenges in Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials. Washington: Institute of Medicine; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard E W. The Public’s Right to health: When Patient Rights Threaten the Commons. Washington University Law Review. 2008;86:1335–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman S. International Health Financing and the Response to AIDS. Journal of Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;52:S38. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bcab5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London L. Human Rights and Public Health: Dichotomies or Synergies in Developing Countries? Examining the Case of HIV in South Africa. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. 2002;30:677–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London L. “Issues of Equity are Also Issues of Rights”: Lessons from Experiences in Southern Africa. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London L, Kagee A, Moodley K, Swartz L. Ethics, Human Rights and HIV Vaccine Trials in Low-Income Settings. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2012;38:286–293. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah T L, Halperin D T. Concurrent Sexual Partnerships and the HIV Epidemics in Africa: Evidence to Move Forward. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:17–24. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann J M. AIDS: the second decade: a global perspective. Journal of Infectious Disease. 1992;165:245–250. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]