Abstract

A 77 year-old female was found with FAB M4Eo acute myeloid leukemia. Although CBFB-MYH11 mRNA was detected in RT-PCR, the conventional cytogenetic analysis failed to reveal inv(16). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and the sequence analysis revealed a fusion between the exon 5 of CBFB and the exon 8 of MYH11, resulting in a minor variant fusion product previously reported as type D. In order to detect the cryptic inv(16) type D, both FISH and RT-PCR are required, and furthermore, the primers for the sequence analysis needs to be selected for the proper diagnosis.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, inversion 16, CBFB-MYH11, RT-PCR, fluorescence in situ hybridization

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with the inv(16) karyotype is commonly referred to as a member of the core binding factor (CBF) AMLs, and it is associated with a favorable prognosis, showing longer periods of complete remission and higher overall survival rates [1]. However, this rearrangement is not always detectable with the standard cytogenetic analysis, and such cryptic inversion is often revealed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) [2], which is also a very powerful method of monitoring minimal residual disease [3]. Furthermore, most of the reported cases of AML with inv(16) are of one subtype called type A, and there have been very few reported cases of other types [4]. Here, we report a case with acute myelomonocytic leukemia with inv(16) type D, for which both RT-PCR and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were required to detect the fusion transcript.

Case report

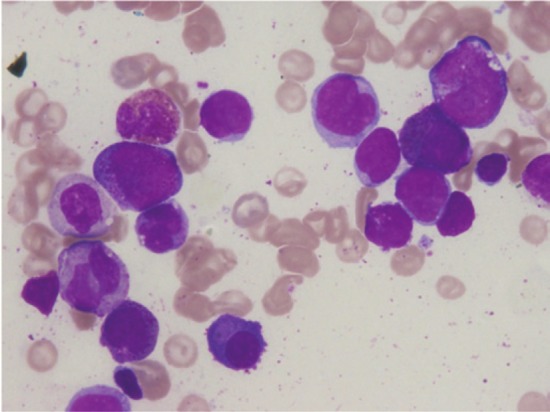

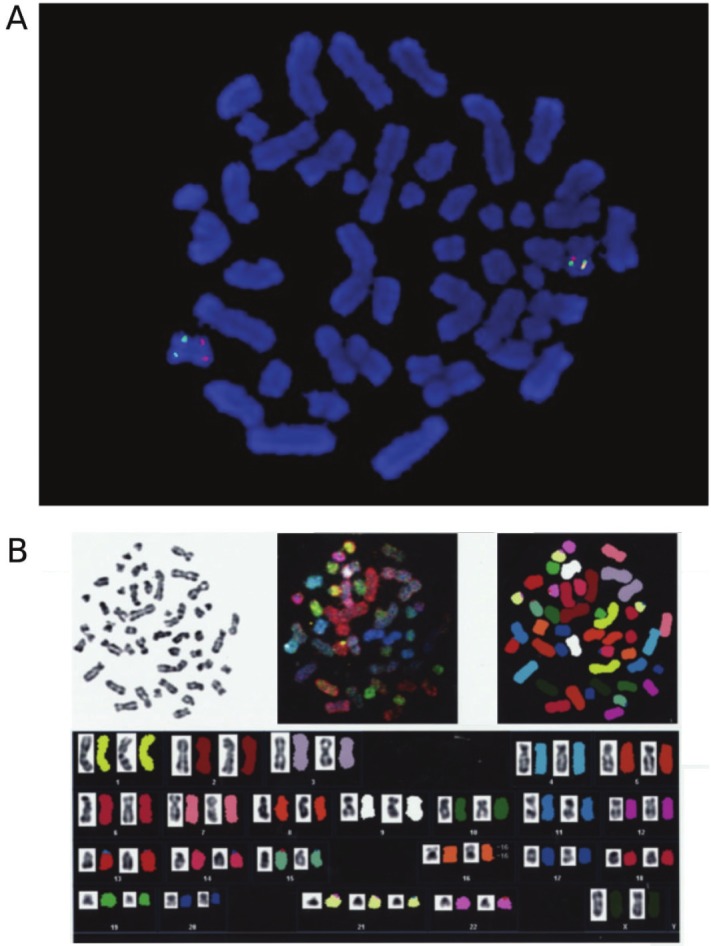

A 77 year-old female was found with pancytopenia at the hospital that she had visited regularly for follow-up of her effort angina pectoris, and was referred to our institution for further study. Laboratory studies of her peripheral blood tests revealed leukocyte count 1.0 × 103/μL with blasts 6.0%, segmented neutrophils 14.0%, eosinophils 0.5%, monocytes 11.0%, lymphocytes 68.0%; a hemoglobin level of 6.9g/dl; and a platelet count of 9.5 × 104/L. Bone marrow aspiration demonstrated normocellular marrow (11.9 × 104/L) with 24.8% of blasts which were morphologically monocytic, myeloperoxidase positive and α-naphthyl butyrate positive, and 25.6% of eosinophils (Figure 1). Immunophenotypical analysis demonstrated that bone marrow cells were positive for CD13, CD33, CD34, CD117 (c-kit) and HLA-DR. Conventional cytogenetic analysis of bone marrow revealed a 47, XX, +21 karyotype. As CBFB-MYH11 mRNA was observed by RT-PCR, FISH was performed, which revealed a fusion signal of CBFB and MYH11, suggesting a cryptic intrachromosomal inversion of the chromosome 16 (Figure 2A), as follows: 46, XX, inv(16) (p13.1q22). ish inv(16)(p13.1)(3’CBFβ+)(q22) (5’CBFβ+), (7 cells); 47, XX, inv(16)(p13.1q22). ish inv(16)(p13.1)(3’CBFβ+)(q22)(5’CBFβ+), +21 (13 cells).

Figure 1.

The Wright-Giemsa stain of the bone marrow aspiration (× 1,000). The morphologically monocytic blasts are found with increased eosinophils.

Figure 2.

A. Representative FISH image of the leukaemic cells. Red and green signals represent CBFB and MYH11, respectively. B. SKY(spectral karyotyping)–FISH analysis. Inversion of the chromosome 16 and trisomy 21 are detected.

A spectral karyotyping (SKY) - FISH confirmed that the translocation involved only the chromosome 16 (Figure 2B). The sequence of the PCR product obtained by using primers C1, M1, M2 [5] and C3 (primer 3 in [6]) revealed that the fusion gene was type D (CBFB exon 5-MYH11 exon 8) [7], whose sequence was identical to that of GenBank accession number AF249897. Thus she was diagnosed as acute myeloid leukemia with CBFB-MYH11 in WHO classification, and M4Eo in FAB classification.

She was treated with the induction therapy of idarubicin (IDR; 12 mg/m2, day 1-2) and cytarabine (Ara-C; 100 mg/m2, day 1-5), and hematological complete remission was confirmed by bone marrow aspiration. She underwent three cycles of consolidation therapy by the same courses of IDR and Ara-C, and her hematological complete remission was still maintained for 19 months.

Discussion

The cytogenetic abnormality of inv(16), as well as t(16; 16), is well known to be associated with acute myeloid leukemia with abnormal eosinophils and favorable prognosis [1]. However, the prognoses of patients depending on types of inv(16) have hardly been discussed separately.

In the articles that discuss the prognoses of different types of inv(16), most of the reported cases are of type A, and there have been only a few reported cases with other types [4,8]. One reported case with type D, after achieving complete remission, relapsed in twelve months, and it is suggested that the variant abnormalities of inv(16) other than type A may not be associated with favorable prognosis [9]. The other example of type D also relapsed in 31 months [10].

In the case that we presented above, reduced doses of IDR + Ara-C (2+5) were administered due to the age of the patient. While CBFB-MYH11 has been positive throughout our clinical observation, hematological complete remission has been maintained for 19 months.

FISH was required to detect inv(16) in the current case, and the sequence analysis was required to detect type D. The conventional type A breakpoint/fusion sites are typically detected with either C1-M1 or C1-M2 primers [8], whereas in the case that we presented above, the C3 primer, which is located closer to the 3’ breakpoint in the CBFB gene and can detect the larger fusion gene more efficiently, was used to detect inv(16) type D. Thus, primers for the sequence analysis need to be selected accordingly to detect the type D inversion properly. Furthermore, an analysis by FISH is also required to confirm the cryptic CBFB-MYH11 fusions that may often have complex translocations [9], as well as the fusions that RT-PCR may fail to detect [8].

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Le Beau MM, Larson RA, Bitter MA, Vardiman JW, Golomb HM, Rowley JD. Association of an inversion of chromosome 16 with abnormal marrow eosinophils in acute myelomonocytic leukemia. A unique cytogenetic-clinicopathological association. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:630–636. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198309153091103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krauter J, Peter W, Pascheberg U, Heinze B, Bergmann L, Hoelzer D, Lübbert M, Schlimok G, Arnold R, Kirchner H, Port M, Ganser A, Heil G. Detection of karyotypic aberrations in acute myeloblastic leukaemia: a prospective comparison between PCR/FISH and standard cytogenetics in 140 patients with de novo AML. Br J Haematol. 1998;103:72–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Reijden BA, Simons A, Luiten E, van der Poel SC, Hogenbirk PE, Tönnissen E, Valk PJ, Löwenberg B, De Greef GE, Breuning MH, Jansen JH. Minimal residual disease quantification in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia and inv(16)/CBFB-MYH11 gene fusion. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:411–418. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stulberg J, Kamel-Reid S, Chun K, Tokunaga J, Wells RA. Molecular analysis of a new variant of the CBF beta-MYH11 gene fusion. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:2021–2026. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000015989-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shurtleff SA, Meyers S, Hiebert SW, Raimondi SC, Head DR, Willman CL, Wolman S, Slovak ML, Carroll AJ, Behm F, et al. Heterogeneity in CBF beta/MYH11 fusion messages encoded by the inv(16)(p13q22) and the t(16; 16)(p13; q22) in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1995;85:3695–3703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claxton DF, Liu P, Hsu HB, Marlton P, Hester J, Collins F, Deisseroth AB, Rowley JD, Siciliano MJ. Detection of fusion transcripts generated by the inversion 16 chromosome in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1994;83:1750–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu P, Tarlé SA, Hajra A, Claxton DF, Marlton P, Freedman M, Siciliano MJ, Collins FS. Fusion between transcription factor CBF beta/PEBP2 beta and a myosin heavy chain in acute myeloid leukemia. Science. 1993;261:1041–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.8351518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viswanatha DS, Chen I, Liu PP, Slovak ML, Rankin C, Head DR, Willman CL. Characterization and use of an antibody detecting the CBF-beta-SMMHC fusion protein in inv(16)/t(16; 16)-associated acute myeloid leukemias. Blood. 1998;91:1882–1890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Climent JA, Comes AM, Vizcarra E, Reshmi S, Benet I, Marugan I, Tormo M, Terol MJ, Solano C, Arbona C, Prosper F, Barragan E, Bolufer P, Rowley JD, García-Conde J. Variant three-way translocation of inversion 16 in AML-M4Eo confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;110:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(98)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hébert J, Cayuela JM, Daniel MT, Berger R, Sigaux F. Detection of minimal residual disease in acute myelomonocytic leukemia with abnormal marrow eosinophils by nested polymerase chain reaction with allele specific amplification. Blood. 1994;84:2291–2296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]