Abstract

Introduction:

Magnesium is an essential element that has numerous biological functions in the cardiovascular system. Hence, three hundred patients with known cardiovascular disease above the age of 25 years were studied to evaluate association between dietary and serum magnesium with cardiovascular risk factors.

Materials and Methods:

Patients were divided into three groups according to serum magnesium levels; ≤1.6 (Group 1), >1.6-2.6 (Group 2) and: >2.6 mg/dl (Group 3), and into two groups according to dietary magnesium intake; ≤350 mg/day (Group 1) and >350 mg/day (Group 2), respectively.

Results:

Mean age of patients was 60.97 ± 12.5 years. Total cholesterol, triglycerides, VLDL, and LDL were significantly higher and HDL cholesterol significantly lower in group 1 when compared with group 2 and group 3. Diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were negatively correlated with serum magnesium levels; which were maintained even after adjustment with age, sex, and anthropometric parameters in multiple regression analysis. Similar observations were observed in dietary magnesium intake except LDL and total cholesterol. Dietary magnesium was positively correlated with serum magnesium.

Conclusions:

Hypomagnesaemia and low dietary intake of magnesium are strongly related to cardiovascular risk factors among known subjects with coronary artery disease. Hence, magnesium supplementation may help in reducing cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, dietary magnesium, dyslipidemia, serum magnesium

INTRODUCTION

Magnesium is an essential element that has numerous biological functions in the cardiovascular system. At the subcellular level, magnesium regulates contractile proteins, modulates transmembrane transport of calcium, sodium and potassium; controls metabolic regulation of energy-dependent cytoplasmic and mitochondrial pathways; regulates oxidative-phosphorylation processes, and affects DNA and protein synthesis. Small changes in extracellular magnesium.[1,2] By serving as a cofactor in the sodium--potassium ATPase pump, magnesium deficiency can lead to increased intracellular sodium and calcium concentrations, which can lead to enhance reactivity of arteries to vasoconstrictor agents, attenuate responses to vasodilators, promote vasoconstriction and increase peripheral resistance, leading to increased blood pressure. Magnesium is also important for the activity of the extracellular enzymes lecithin--cholesterol acyl transferase, and lipoprotein lipase.[3] Serum magnesium has been linked to atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, hypertension and cardiac failure[4] but was not an independent risk factor for mortality in heart patients.[5]

Many studies have demonstrated correlation between magnesium and risk factors but most of them were animal studies.[6–10] Among the human studies done, very few are done on subjects with cardiovascular disease in relation with risk factors, which suggested that low magnesium may contribute to atherosclerosis, HTN, DM.[11–13] Relation between dietary intake and cardiovascular disease are particularly unclear due to variety of confounding dietary factors.[11] Hence, this study was undertaken to evaluate association of serum and dietary magnesium with traditional cardiovascular risk factors among subjects with established coronary artery disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Three hundred patients with known coronary disease above the age of 25 years were included in this study. Patients, who were admitted in cardiology department for evaluation of chest pain and found angiography positive, were selected in the study consecutively. Exclusion criteria were presence of chronic kidney disease; hepatic dysfunction; known endocrinal or rheumatological diseases or chronic infections. All cases were interviewed using a questionnaire, which included data on smoking, physical activity. Height, weight, waist, hip circumference were measured. BMI and WHR was calculated. Data on clinical history of HTN, DM and medications (antihypertensive and oral hypoglycemic agents) was also acquired.

Nutrition assessment was done once at the time of recruitment; based on previous two days 24 hour dietary recall. Mean of recall of two days was taken. Diet was assessed using a computer based comprehensive diet assessment known as Diet soft software, verson: 1.1.7 [developed by Invincible IDeAS (www.invincibleideas.com) based on book Nutritive value of Indian Foods by C. Gopalan, B.V. Rama Sastri, and S.C. Balasubrsmanian, National Institute of Nutrition, Indian council of Medical Research, Hyderabad, India].[14] Questionnaires and diet assessments were administered via interview by trained staff. Portion size estimation was undertaken using volume measures, circular measures, numbers, and linear measures. Mean of recall of two days was taken. To help participants estimate portion sizes, interviewers provided commonly used serving plates, bowls, utensils, cups and spoons. If measurements could not be given we recorded in three sizes: small, medium or large and any unusual intake was noted on the recall. For each nutrient, we used a standardized unit of measurement and reported values per 100 g of edible portion of food product. There was no significant change in the dietary pattern of these participants and no change in lifestyle also.

Fasting blood samples were collected after 14 h fasting. Total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL, LDL, and VLDL cholesterol were measured by using CHOD PAP, LIP/ GK, enzymatic clearance method, respectively, and LDL and VLDL were calculated by Friedewald's formula. Interassay 3.84% and intraprecision was 2% respectively for all parameters. Magnesium measured by Xylidyl blue method, which has no interference due to calcium.[15]

Patients were divided into three groups according to serum magnesium levels; group-1: ≤ 1.6 mg/dl (n = 176, 58.6%), group 2: > 1.6-2.6 mg/dl (n = 102, 34%), and group 3: > 2.6 mg/dl (n = 26, 8.6%) and into two groups according to Recommended Dietary allowance of magnesium; group-1 with dietary intake of magnesium ≤ 350 mg/day (n = 186, 62%) and group 2 (n = 114, 38%) with dietary intake of magnesium levels > 350 mg/day.

The study was approved by Institutional ethics committee of Deenanath Mangeshkar Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Definitions

Dyslipidemia was defined as triglyceride level ≥ 150 mg/ dl and HDL Cholesterol level < 40 mg/dl (NCEP ATP III). Conventional risk factors were defined as follows: BMI <25 normal, ≥25 overweight/obese, DM (by history and American Diabetes Association; 2011), HTN (systolic and diastolic blood pressures above 140 and 90 mmHg, respectively).

Statistical method

Statistical analysis was carried out using EPI INFO 3.5.3 (CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA). Data were presented as mean ± SD or number (%) unless specified. All parametric data were analysed by Student's t-test. If Barlett's chi-square test for equality of population variances was < 0.05 then Kruskal--Wallis test was applied. All nonparametric data were analysed by chi-square test. Pearson's correlation and multiple regression analysis were used to assess the strength of relationship between serum magnesium and cardiovascular risk factors. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

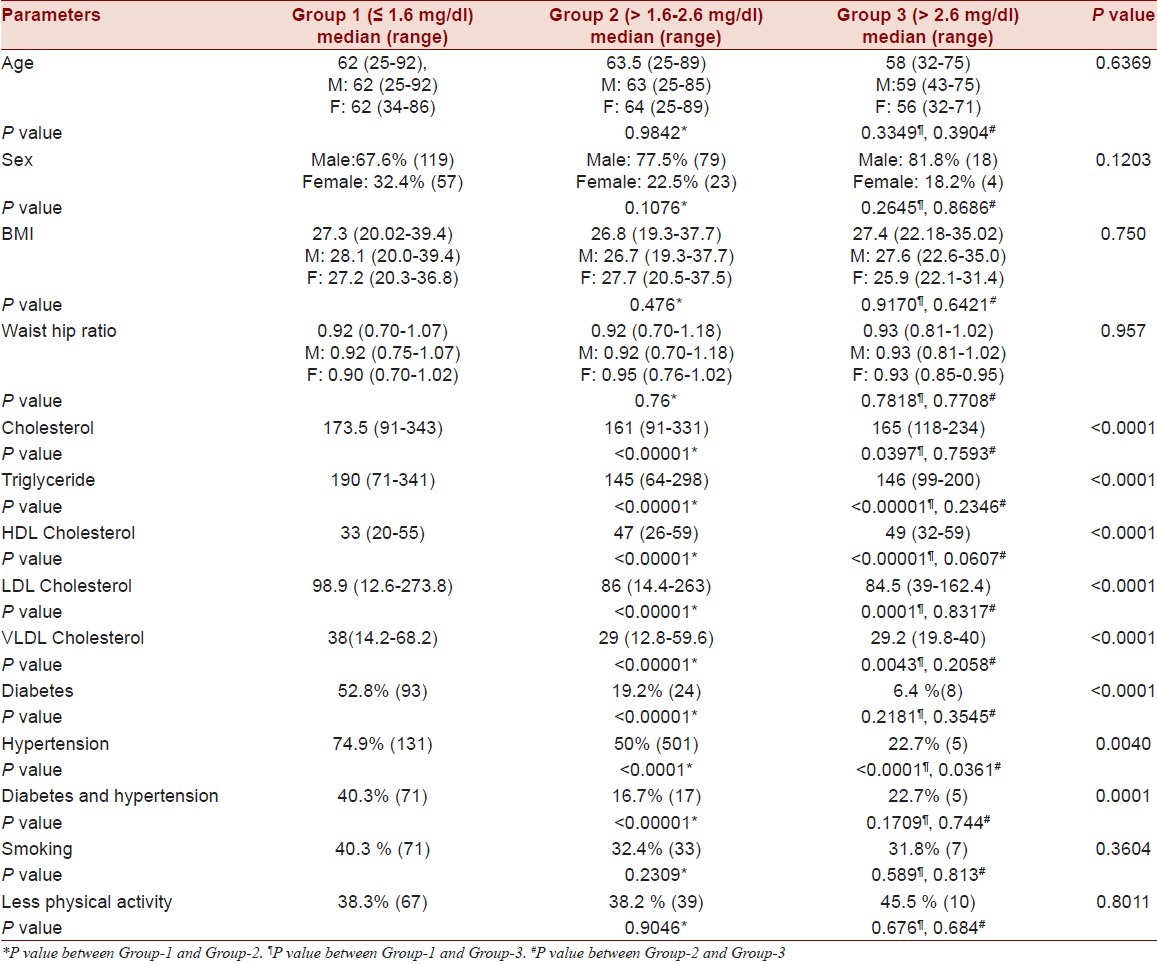

Three hundred patients with known cardiovascular disease (M: 216; F: 84, age: 25-92) were studied. A comparison of cardiovascular risk factors according to serum magnesium levels are given in Table 1. Mean age of patients was 60.9 ± 12.4 years. There was no age difference between males and females (M: 60.95 ± 12.3; F: 61.03 ± 12.9; P = 0.10).

Table 1.

Cardiovascular risk factor in groups according to serum magnesium levels

Serum magnesium

Anthropometric parameters were comparable in all three groups. There was no correlation between body mass index and waist hip ratio with serum magnesium level [Table 1]. Serum magnesium levels were independent of smoking and physical activity.

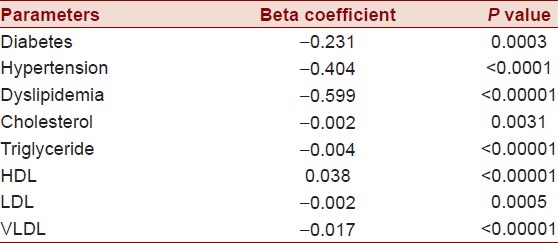

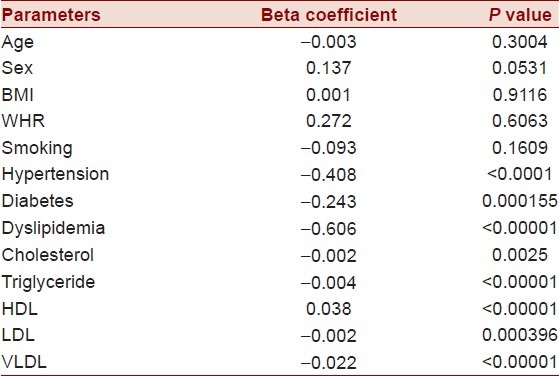

Total cholesterol, triglycerides, VLDL and LDL cholesterol were significantly higher and HDL cholesterol significantly lower in group 1 when compared with group 2 and group 3. There was no significant difference between group-2 and group-3. This significant association was maintained even after adjustment with age, sex, waist hip ratio and BMI [Tables 1–3].

Table 3.

Correlation of serum magnesium with cardiovascular risk factors after adjustment with age, sex, BMI and WHR in multiple regression analysis

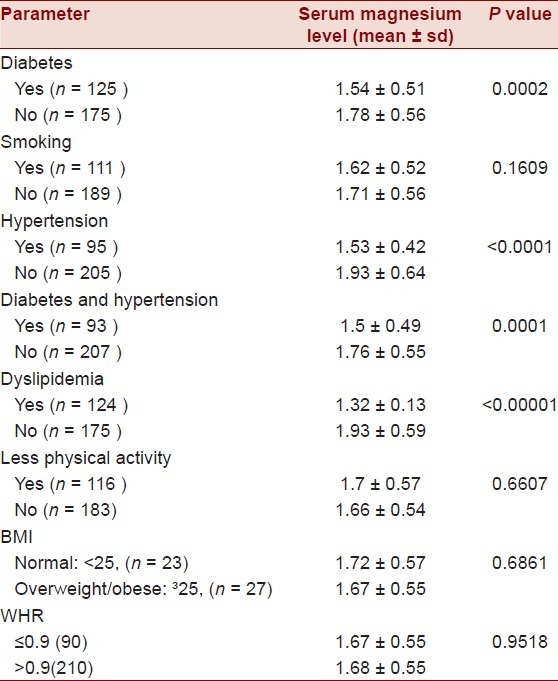

Number of subjects with DM; and DM with HTN were significantly higher in group-1 compared to group-2. DM in these three groups was 52.8%, 19.2%, 6.4% in group 1, 2, and 3 respectively. However, subjects with HTN, DM, and DM with HTN had significantly lower serum magnesium levels than without these risk factors [Table 4]. DM and HTN were negatively correlated with serum magnesium levels; which were maintained even after adjustment with age, sex, BMI and waist hip ratio in multiple regression analysis [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 4.

Comparative serum magnesium in relation to cardiovascular risk factors

Table 2.

Correlation of serum magnesium with cardiovascular risk factors (univariate analysis)

Dietary magnesium

Dietary magnesium was positively correlated with serum magnesium (beta coefficient: 53.46, P:< 0.0001) and this was maintained even after adjustment with age and sex in multiple regression analysis.

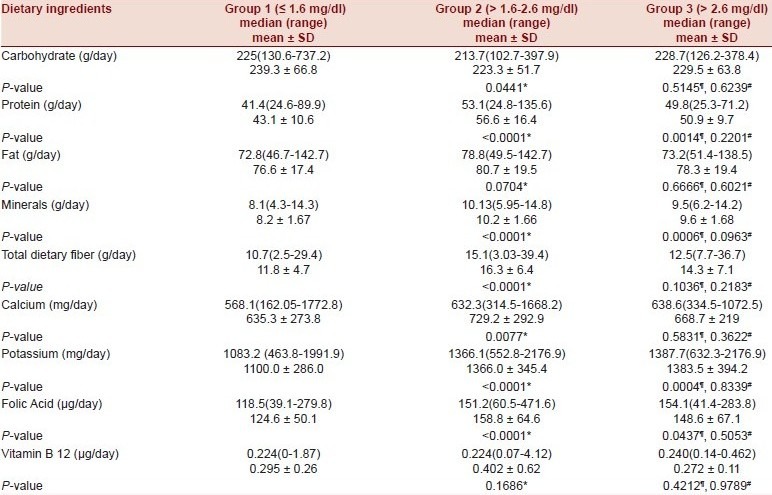

Intake of dietary calcium, potassium, total dietary fiber, proteins, sodium and folic acid increased with increased intake of dietary magnesium (P < 0.0001, P < 0.05). Significance remained after adjustment for age and sex. However, there was no correlation between dietary fat, carbohydrate, vitamin B12, saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids intake with dietary magnesium level (Data not given).

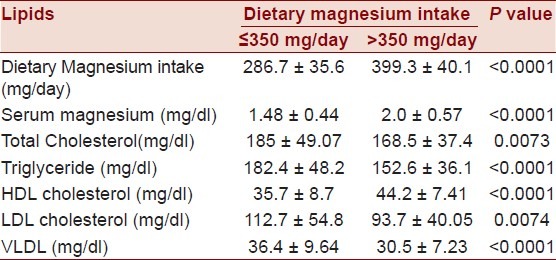

Total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL and VLDL were significantly higher and HDL cholesterol significantly lower in the dietary magnesium group1 when compared with group2 [Table 5]. There was no change in significance after adjustment with age and sex.

Table 5.

Lipid levels according to dietary magnesium groups

When dietary magnesium was correlated with risk factors, subjects with HTN, DM and DM with HTN had significantly lower dietary magnesium levels than without these risk factors (diabetic; Yes = 314.8 ± 58.6 mg/day, No = 339.9 ± 69.4, P = 0.001; DM and HTN; Yes = 306.7 ± 56.04 mg/day, No = 339.7 ± 68.04 mg/day, P < 0.0001). Patients with dyslipidemia had significantly low dietary magnesium levels as compared to patients without dyslipidemia (Dyslipidemia; Yes = 293.8 ± 53.3 mg/day, No = 354.6 ± 62.9 mg/day, P < 0.0001). DM and DM with HTN and dyslipidemia were negatively correlated with dietary magnesium levels in univariate analysis and even after adjustment with age, sex and dietary variables (sodium, potassium, carbohydrate, energy, dietary fiber, protein intake, vitamin B12 and folic acid) in multiple regression analysis [Tables 6 and 7]. However, no correlation was found between other smoking, HTN, physical activity and dietary magnesium levels. Patients in group-1 also had decreased intake of protein, dietary fibers, calcium, potassium and folic acid compared to other groups [Supplementary Table 1].

Table 6.

Univariate analysis of dietary magnesium with risk factors

Table 7.

Correlation of dietary magnesium with risk factors after adjustment with age, sex, and dietary variables (sodium, potassium, carbohydrate, energy, total dietary fiber, protein intake, vitamin B12, folic acid)

Supplementary Table 1.

Dietary differences between groups according to magnesium levels

DISCUSSION

This is the first study conducted in angiographically proved cardiovascular patients analyzing role of serum and dietary magnesium from India. In present study more than half of patients (58.6%) were having low magnesium level and 62% were taking dietary magnesium below recommended dietary allowance (350 mg/day). Others have documented hypomagnesaemia 19%--53% in patients with cardiovascular disease and acute myocardial infarction.[16,17]

Few studies have shown that hypomagnesaemia plays an important role in modifying risk factors of cardiovascular disease like dyslipidemia, DM, and HTN.[11–13] In present study there are significantly higher numbers of subjects with DM, HTN and dyslipidemia in lowest group indicating hypomagnesaemia is common in these conditions. Similar correlation was observed in dietary magnesium. All these risk factors had lower serum magnesium level except in subjects with isolated HTN. Other studies have also reported no differences in serum magnesium levels in hypertensive patients.[18,19] Serum magnesium had significantly negative correlation cardiovascular risk factors which persisted after adjustment with age, sex, and anthropometric parameters in multiple regression analysis. None of the subjects were hypertensive in group-3, which suggest that serum magnesium level may be protective in development of HTN. Many epidemiological and clinical investigations that supported the hypothesis that increased magnesium intake contribute to prevention of HTN and cardiovascular disease.[20–23] However, in a six-year follow-up ARIC (atherosclerosis risk in communities) study, in which healthy individual were taken and followed up for incident HTN, there was no significant association between dietary magnesium intake and incident HTN in male and female.[24] Several studies have addressed the question of the relation between hypomagnesaemia and DM. Although studies in small groups of patients have yielded conflicting results,[25,26] overwhelming evidence from human and animal studies indicates that both plasma and tissue magnesium levels are reduced in DM.[25,27] In a study[26] mean plasma magnesium concentration of the diabetics was significantly lower than that of the control group. Hypomagnesemia was reported to be one of the strongest predictors of gain in LVM over the following 5 years in “Study of Health in Pomerania”.[28] In addition, experimental hypomagnesaemia inhibits prostacyclin receptor function, producing an imbalance between prostacyclin and thromboxane effects; such imbalance has been suggested to be of etiological importance for the development of diabetic vascular disease.[29,30]

In present study total cholesterol, triglycerides, VLDL, and LDL cholesterol were significantly higher and HDL cholesterol significantly lower in subjects with hypomagnesaemia. All lipid parameters had negative correlation with serum magnesium level except HDL; which was positively correlated with serum magnesium level. Similar observations have made by other studies[11,13] but an equal number of studies have failed to demonstrate this association.[12,31] Studies using patients with metabolic syndrome or DM have shown that individuals with low levels of magnesium have lower levels of HDL-cholesterol[32–34] but higher levels of triglycerides[33,34] and total cholesterol.[34] Other studies examining serum magnesium levels have shown a positive correlation with HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL Cholesterol and total cholesterol when general population was studied.[35] Among subjects with metabolic syndrome a potential relationship between low ionized magnesium[33,34,36] or total serum magnesium[32,34] and an atherogenic lipid profile, involving low serum HDL-cholesterol[16,17] and high total cholesterol,[34,36] and high triglycerides[32–34] have been reported, proposing a potential role for magnesium in the pathogenesis of CVD.[32,34] Similar association was found between dietary magnesium with total cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL, HDL and VLDL. Similar association has been reported between dietary magnesium and lipid levels. Total cholesterol tended to decrease with increasing magnesium intake across the ranges of magnesium[37] and was inversely related to HDL cholesterol.[11] Patients with hypomagnesaemia also had decreased intake of protein, dietary fibers, calcium, potassium and folic acid compared to other groups, which may also contribute to various risk factors.

Main limitation of the study was absence of long term follow-up. Further there were male predominance and less number of cases in group-3. As we have taken consecutive cases and CVD being male predominance disease this imbalance in sexes can be explained.

CONCLUSION

Half of cardiovascular disease patients have hypomagnesaemia. There is a strong correlation between serum and dietary magnesium. Serum and dietary magnesium are strongly related to cardiovascular risk factors such as dyslipidemia, DM, and HTN. There are few studies indicating improvement in atherogenic lipid profile with magnesium supplementation.[20] Hence, magnesium supplementation in our population may help in reducing cardiovascular disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Dhananjay Kelkar, Director, Deenanath Mangeshkar Hospital and Research Centre, Pune, for providing required facilities. We also thank Col M. K. Garg, Department of Endocrinology, Army Hospital (Research and Referral), Delhi Cantonment, for providing guidance in preparation of manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altura BM, Altura BT. Magnesium and cardiovascular biology: An important link between cardiovascular risk factors and atherogenesis. Cell Mol Biol Res. 1995;41:347–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasaki S, Oshima T, Matsuura H, Ozono R, Higashi Y, Sasaki N, et al. Abnormal magnesium status in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;98:175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosanoff A, Seelig MS. Comparison of mechanism and functional effects of magnesium and statin pharmaceuticals. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:501S–5S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyckner T, Westor PO. Potassium / magnesium depletion in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 1987;82:11–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eichhorn EJ, Tandon PK, DiBianco R, Timmis GC, Fenster PE, Shannon J, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of serum magnesium concentration in patients with severe chronic congestive heart failure: The PROMISE Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:634–40. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90095-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitale JJ, White PL, Nakamura M, Hegsted DM, Zancheck N, Hellerstein EE. Interrelationships between experimental hypercholesteremia, magnesium requirement, and experimental atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 1957;106:757–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.106.5.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellerstein EE, Vitale JJ, White PL, Hegested DM, Zamcheck N, Nakamura M. Influence of dietary magnesium on cardiac and renal lesions of young rats fed an atherogenic diet. J Exp Med. 1957;106:767–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.106.5.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura M, Torii S, Hiramatsu M, Hiranjo J, Sumiyoshi A, Tanaka K. Dietary effect of magnesium on cholesterol-induced atherosclerosis of rabbits. J Atheroscler Res. 1965;5:145–58. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1319(65)80057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito M, Toda T, Kummerow FA, Nishimori I. Effect of magnesium deficiency on ultrastructural changes in coronary arteries of swine. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1986;36:225–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1986.tb01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaya P, Kurup PA. Magnesium deficiency and metabolism of lipids in rats fed cholestorol-free and cholestorol-containing diet. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1987;24:92–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma J, Folsom AR, Melnick SL, Eckfeldt JH, Sharrett AR, Nabulsi AA, et al. Associations of serum and dietary magnesium with cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, insulin, and carotid arterial wall thickness: The ARIC study. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:927–40. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00200-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manthey J, Stoeppler M, Morgenstern W, Nussel E, Opherk D, Weintraut A, et al. Magnesium and trace metals: Risk factors for coronary heart disease? Associations between blood levels and angiographic findings. Circulation. 1981;64:722–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.4.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen HS, Aurup P, Goldstein K, Mc Nair P, Mortensen BB, Larsen OG, et al. Influence of magnesium substitution therapy on blood lipid composition in patients with ischemic heart disease. A double-blind, placebo controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1050–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopalan C, Sastri BV Rama, Balasubramanian SC. In: Nutritive value of Indian Foods. 3rd ed. Rao BS Narasinga, Deosthale YG, Pant KC., editors. Hyderabad, India: Publisher-National Institute of Nutrition, Indian council of Medical Research; 1989. pp. 1–156. Reprint-2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone MJ, Chowdrey PE, Miall P, Price CP. Validation of an enzymatic total magnesium determination based on activation of modified isocitrate dehydrogenase. Clin Chem. 1996;42:1474–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamopoulos C, Pitt B, Sui X, Love TE, Zannad F, Ahmed A. Low serum magnesium and cardiovascular mortality in chronic heart failure: A propensity-matched study. Int J Cardiol. 2009;136:270–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottlieb SS, Baruch L, Kukin ML, Bernstein JL, Fisher ML, Packer M. Prognostic importance of the serum magnesium in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16:827–31. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cappuccio FP, Markandu ND, Beynon GW, Shore AC, Sampson B, MacGregor GA. Lack of effect of oral magnesium on high blood pressure: A double blind study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:235–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6490.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrara LA, Iannuzzi R, Castaldo A, Iannuzzi A, Dello Russo A, Mancini M. Long-term magnesium supplementation in essential hypertension. Cardiology. 1992;81:25–33. doi: 10.1159/000175772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joffres MR, Reed DM, Yano K. Relationship of magnesium intake and other dietary factors to blood pressure: The Honolulu heart study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:469–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.2.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whelton PK, Klag MJ. Magnesium and blood pressure: Review of the epidemiologic and clinical trial experience. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:26G–30G. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Leer EM, Seidell JC, Kromhout D. Dietary calcium, potassium, magnesium and blood pressure in the Netherlands. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:1117–23. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.6.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simons-Morton DG, Hunsberger SA, Van Horn L, Barton BA, Robson AM, McMahon RP, et al. Nutrient intake and blood pressure in the Dietary Intervention Study in Children. Hypertension. 1997;29:930–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.4.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peacock JM, Folsom AR, Arnett DK, Eckfeldt JH, Szklo M. Relationship of serum and Dietary Magnesium to Incident Hypertension: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:159–65. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider LE, Schedl H P. Effects of alloxan diabetes on magnesium metabolism in the rat. Proc Sot Exp Biol Med. 1974;147:494–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-147-38373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walti MK, Zimmermann MB, Spinas GA, Hurrell RF. Low plasma magnesium in type 2 diabetes. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:289–92. doi: 10.4414/smw.2003.10170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yajnik CS, Smith RF, Hockaday TD, Ward NI. Fasting plasma magnesium concentration and glucose disposal in diabetes. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288:1032–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6423.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reffelmann T, Dörr M, Ittermann T, Schwahn C, Völzke H, Ruppert J, et al. Low serum magnesium concentrations predict increase in left ventricular mass over 5 years independently of common cardiovascular risk factors. Atherosclerosis. 2010;213:563–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerrard JM, Stuart MJ, Rao GH, Staffes MW, Mauer SM, Brown DM, et al. Alternations in balance of prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis in diabetic rats. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;95:950–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison HE, Reece AH, Johnson M. Decreased prostacyclin in experimental diabetes. Life Sci. 1978;23:351–5. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasri H, Baradaran HR. Lipids in association with serum magnesium in diabetes mellitus patients. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2008;109:302–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guerrero-Romero F, Rodríguez-Morán M. Hypomagnesemia is linked to low serum HDL-cholesterol irrespective of serum glucose values. J Diabetes Complications. 2000;14:272–6. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(00)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corica F, Corsonello A, Ientile R, Cacinotta D, Di Benedetto A, Perticone F, et al. Serum ionized magnesium levels in relation to metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetic patients. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:210–5. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerrero-Romero F, Rodríguez-Morán M. Low serum magnesium levels and metabolic syndrome. Acta Diabetol. 2002;39:209–13. doi: 10.1007/s005920200036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randell EW, Mathews M, Gadag V, Zhang H, Sun G. Relationship between serum magnesium values, lipids and anthropometric risk factors. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haenni A, Ohrvall M, Lithell H. Atherogenic lipid fractions are related to ionized magnesium status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:202–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abbott RD, Ando F, Masaki KH, Tung KH, Rodriquez BL, Petrovitch H, et al. Dietary magnesium intake and the future risk of coronary heart disease (the honolulu heart program) Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:665–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00819-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]