Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a subpopulation of tumor cells that possess self-renewal and tumor initiation capacity and the ability to give rise to the heterogenous lineages of malignant cells that comprise a tumor. CSCs possess multiple intrinsic mechanisms of resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs, novel tumor-targeted drugs, and radiation therapy, allowing them to survive standard cancer therapies and to initiate tumor recurrence and metastasis. Various molecular complexes and pathways that confer resistance and survival of CSCs, including expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) drug transporters, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog, Notch and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways, and acquisition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), have been identified recently. Salinomycin, a polyether ionophore antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces albus, has been shown to kill CSCs in different types of human cancers, most likely by interfering with ABC drug transporters, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and other CSC pathways. Promising results from preclinical trials in human xenograft mice and a few clinical pilote studies reveal that salinomycin is able to effectively eliminate CSCs and to induce partial clinical regression of heavily pretreated and therapy-resistant cancers. The ability of salinomycin to kill both CSCs and therapy-resistant cancer cells may define the compound as a novel and an effective anticancer drug.

1. Introduction

The demonstration of cancer stem cells (CSCs) in a variety of human malignant tumors, including cancers of the blood, breast, brain, bone, skin, liver, lung, bladder, ovary, prostate, colon, pancreas, and head and neck has led to the conceptual hypothesis that tumors, like physiologic proliferative tissues, can be hierarchically organized and propagated by limited numbers of stem cells [1–8]. According to a consensus definition, these CSCs are cells within a tumor that possess the capacity to self-renew and to give rise to the heterogeneous lineages of cancer cells that comprise the tumor [9]. CSCs can be defined experimentally by their ability to recapitulate the generation of a continuously growing tumor in serial xenotransplantation approaches [9]. It is not yet entirely clear whether such tumorigenic cells identified and isolated from hematopoietic and solid tumors by virtue of their expression of specific cell surface markers [5, 7] are the real “stem cells” of the tumor, but, although not readily testable, the CSC concept of carcinogenesis and tumor maintenance is fairly accepted to date [3–7]. Moreover, recent studies provide evidence for the existence and relevance of CSCs in clinical therapeutic situations [10–12].

CSCs possess numerous intrinsic mechanisms of resistance to conventional chemotherapeutic drugs, novel tumor-targeted drugs, and radiation therapy, including expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) drug transporters [13–17], activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [18–21], activation of the Hedgehog and Notch signaling pathways [20–24], expression and activation of the Akt/PKB and ATR/CHK1 survival pathways [25–27], aberrant PI3 K/Akt/mTOR-mediated signaling and loss of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) [28–30], amplified activity of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) [31–34], amplified checkpoint activation and efficient repair of DNA and oxidative damage [35–40], constitutive activation of NF-κB [41–43], expression of CD133/prominin-1 and general radioresistance [35, 36, 44–46], protection from apoptosis by autocrine production of interleukin-4 [47, 48], various mechanisms of apoptosis resistance and defective apoptotic signaling [45, 49, 50], metabolic alterations with a preference for hypoxia [51], protection by microenvironment and niche networks [28, 52, 53], radiation-induced conversion of cancer cells to CSCs [54], immune evasion [55–57], acquisition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [10, 24, 58, 59], low proliferative activity [60], and, ultimately, transient or long-termed quiescence, the latter also termed dormancy [61–63]. Many of these CSC-specific mechanisms as well as yet unknown mechanisms of immortality and resistance [5, 64–66] allow CSCs to survive current cancer therapies and to initiate reconstitution of the original tumor, long-term tumor recurrence, and metastasis [10–12, 67–72]. Therefore, a deeper understanding of CSC biology as well as the development, validation, and therapeutic use of novel compounds and drugs that effectively eradicate CSCs is urgently needed to improve clinical outcome in cancer.

2. The Challenge of Targeting CSCs and Their Progeny

According to the cancer stem cell concept of carcinogenesis [1, 3, 4, 7–9, 73], CSCs represent novel and translationally relevant targets for cancer therapy, and the identification, development, and therapeutic use of compounds and drugs that selectively target CSCs are a major challenge for future cancer treatment [5, 65, 74–76]. However, the goal for any CSC-directed therapy should be the eradication of all CSCs in a patient, and the efficacy of single agents targeting CSCs may be limited by several factors. CSCs represent a heterogenous population that may not be homogeneously sensitive to a given anti-CSC agent [8, 77–79], and, under the selection pressure of agents targeting CSCs, therapy-resistant CSC clones may emerge [80]. Therefore, the eradication of all CSCs will likely require targeting of more than one intrinsic pathway operating in CSCs to reduce the probability of escape mutants [74, 81–83]. Moreover, agents causing tumor regression in advanced stages of cancer likely reflect effects on the bulk tumor population but may have minimal effect on the CSC population. In contrast, a CSC-specific therapy would show modest effect on tumor growth of the bulk tumor population in advanced stages of cancer but may have substantial clinical benefit in early stages of cancer as well as in neoadjuvant and adjuvant clinical settings [75]. Ultimately, cure of cancer will require the eradication of all malignant cells within a patient's cancer: CSCs and their progeny.

Recent data obtained in vitro and in xenograft mice bearing human cancers indicate that CSC targeting agents are most effective in eradicating CSCs and their progeny when these agents are combined with conventional cytostatic drugs and/or novel tumor-targeted drugs [84–95]. Therefore it will be important and promising to combine in sophisticated clinical settings CSC targeting agents with novel tumor-targeted drugs and conventional cytotoxic drugs. Such combinations may act in concert to eradicate CSCs, more differentiated progenitors, and bulk tumor cells in cancer patients [87, 88, 96–101].

3. Compounds and Drugs That Target CSCs

Various compounds and drugs that selectively target CSCs have been discovered recently [65, 74, 76, 106]. These agents include microbial-derived and plant-derived biomolecules [107–111], small molecule inhibitors targeting key components of intrinsic signaling pathways of CSCs [30, 112–114], antibodies directed against CSC-specific cell surface molecules [115–117], and, surprisingly, some classical drugs, such as metformin [94, 118–120], tranilast [76, 121], and thioridazine [122] that have been used for decades for the treatment of metabolic, allergic, and psychotic diseases, respectively.

Although these compounds and drugs have been shown to effectively target signaling pathways and/or molecules selectively operating in CSCs, some of them are also capable of killing other types and subpopulations of cancer cells, which do not display CSC properties. In particular, the biomolecules salinomycin and parthenolide as well as the biguanide metformin have been demonstrated to induce apoptosis in various types of human cancer cells [108, 123, 124], suggesting that these compounds may contribute to the eradication of cancer more effectively than compounds targeting either CSCs or regular cancer cells. Moreover, the ionophore antibiotic salinomycin seems to have even extended capabilities of eliminating cancer (Table 1), because this compound has been demonstrated to effectively target regular cancer cells [16, 125–127], highly multidrug and apoptosis-resistant cancer cells [16, 85, 125], and CSCs [16, 84, 87, 88, 128–131].

Table 1.

Salinomycin's action against human CSCs, cancer cells and cancers.

| Target class | Target demonstrated | Effects and mechanisms | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast CSCs, breast cancer cells |

Human mammary epithelial cells, immortalized and transformed by retroviral expression of SV40 large T oncogene, hTERT and H-rasV12 (= HMLER cells), and subsequent knockdown of E-cadherin by short hairpin RNA interference (= HMLER-shEcad cells). HMLER-shEcad cells display properties of breast CSCs and had undergone EMT Human SUM159 breast cancer cells. |

HMLER-shEcad cells exhibit resistance to the chemotherapeutic drugs and cytotoxic agents paclitaxel, doxorubicin, actinomycin D, campthotecin, and staurosporine. HMLER-shEcad cells are effectively killed by salinomycin. Salinomycin, but not paclitaxel, inhibits tumorsphere formation of HMLER-shEcad cells. Salinomycin induces epithelial differentiation of HMLER cells. Salinomycin inhibits tumor-seeding ability of HMLER cells in xenograft mice. Salinomycin induces differentiation, regression, necrosis, and apoptosis of SUM159 tumors in xenograft mice. |

First demonstration that salinomycin targets human CSCs. | [128] |

|

| ||||

| Breast CSCs, breast cancer cells |

CD44+ CD24− ALDH1+ cells, and SOX2 and HER2 expressing cells, isolated from the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 MCF-7 tumors in xenograft mice. |

Inhibition of tumorsphere formation and cloning efficiency by salinomycin. Elimination of ALDH1+ and SOX2 expressing breast CSCs from tumorspheres by salinomycin. Tumor regression and depletion of breast CSCs in MCF-7 xenograft mice by salinomycin. |

Enhancement of the effects of salinomycin by doxorubicin, trastuzumab, or paclitaxel. | [85, 86, 88] |

|

| ||||

| AML SCs | Human promyeloblastic CD34+ CD38− KG-1a leukemia SCs (KG-1a AML SCs) expressing functional ABC transporters P-glycoprotein, ABCG2, and ABCC11. | KG-1a AML SCs exhibit resistance to apoptosis induction by cytosine arabinoside, doxorubicin, gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, topotecan, etoposide, or bortezomib that can be reversed by the ABC transporter inhibitor cyclosporine A. Salinomycin induces massive apoptosis in KG-1a AML SCs, independently of cyclosporine A. KG-1a AML SCs cannot be adapted to survive and to proliferate in the presence of apoptosis-inducing concentrations of salinomycin. KG-1a AML SCs can readily be adapted to survive and to proliferate in the presence of initially apoptosis-inducing concentrations of doxorubicin or bortezomib. |

First demonstration that salinomycin induces apoptosis and overcomes ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance in human CSCs. | [16] |

|

| ||||

| Lung CSCs |

Human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells expressing ALDH1, Oct-4, Nanog, and Sox2. | Salinomycin inhibits tumorsphere formation and expression of Oct-4, Nanog, and Sox2 of A549 lung adenocarcinoma cancer stem-like cells. | [130] |

|

|

| ||||

| Gastric CSCs | Human gastric cancer cells NCI-N87 and SNU-1, expressing high levels of ALDH1, Sox2, Nanog, and Nestin and displaying resistance to 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin. | Salinomycin inhibits tumorsphere formation, proliferation, and viability of NCI-N87 and SNU-1 gastric cancer stem-like cells. | [131] | |

|

| ||||

| Osteosarcoma CSCs | From different human osteosarcoma cell lines, osteosarcoma CSC were enriched by tumorsphere selection, chemotherapy selection, and Oct-4 and Sox2 expression. | Salinomycin inhibits tumorsphere formation, induces apoptosis in osteosarcoma CSCs, sensitizes them to conventional cytostatic drugs, and downregulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the cells. | [132] | |

|

| ||||

| Colorectal CSCs | In human colorectal HT29 and SW480 cells, subpopulations of CSCs expressing CD133 were isolated. | Salinomycin, but not oxaliplatin, inhibits the tumorsphere forming ability and the migratory and invasive capacity of the cells and reduces the proportion of CD133 CSCs in HT29 and SW480 cells. Salinomycin, but not oxaliplatin, induces expression of E-cadherin and downregulates expression of vimentin in HT29 cells. |

[129] | |

|

| ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma CSCs | Human SCC9 and OCTT2 squamous cell carcinoma cells sorted in low and high E-cadherin (Ecad) expressing cells. Low Ecad expressing cells exhibit drug resistance, mesenchymal phenotype, and properties of CSCs. | Salinomycin, but not cisplatin, inhibits proliferation of low Ecad expressing cells. Salinomycin, but not cisplatin, eliminates low Ecad and high vimentin expressing primary mesenchymal-like SCC human tumors in xenograft in mice. |

[133] | |

|

| ||||

| Pancreatic CSCs | From different human pancreatic cancer cell lines, pancreatic CSCs were separated by virtue of its expression of CD133 using flow cytometry. | Salinomycin inhibits the growth of CD133 expressing pancreatic CSCs in tumorsphere formation assays, while gemcitabine inhibits the growth of CD133-negative non-CSCs. Salinomycin combined with gemcitabine eliminates the engraftment of human pancreatic cancer in xenograft mice more effectively than the single agent. |

First demonstration that salinomycin eliminates human cancer (pancreatic cancer) in xenograft mice more effectively when combined with a conventional cytostatic drug (gemcitabine). | [87] |

|

| ||||

| Prostate CSCs, prostate cancer cells |

Prostate CSCs with ALDH-1 activity and CD44 expression were separated from human VCaP and LNCaP prostate cancer cells. | Salinomycin inhibits ALDH-1 activity and expression of CD44 in VCaP- and LNCaP-derived prostate CSCs. Salinomycin reduces the CSCs fraction in VCaP and LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Salinomycin induces generation of ROS and grothw inhibition in VCaP and LNCaP prostate cancer cells. | [134] |

|

|

| ||||

| Multidrug, radiation and apoptosis resistant cancer cells | Human Molt-4 and Jurkat T-cell leukemia cells, Jurkat T-cell leukemia cells overexpressing Bcl-2, primary therapy refractory CD4+ T-ALL cells from patients, Namalwa Burkitt lymphoma cells, multidrug- and radiation-resistant Namalwa Burkitt lymphoma cells overexpressing 26S proteasomes, multidrug-resistant MES-SA/Dx5 uterine sarcoma cells expressing P-glycoprotein. |

Salinomycin induces massive apoptosis in the multidrug-, radiation- and apoptosis-resistant human cancer cells. Salinomycin-induced apoptosis is independent of tumor suppressor protein p53, caspase activation, the CD95/CD95 ligand system, and the proteasome. Salinomycin fails to induce apoptosis in normal human peripheral CD4+ T lymphocytes. |

First demonstration that salinomycin induces apoptosis in human cancer cells and in multidrug-, radiation- and apoptosis-resistant cancer cells. | [125] |

|

| ||||

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells | Primary CLL cells obtained from 13 CLL patients. | Salinomycin induces apoptosis in human CLL cells. Salinomycin inhibits in CLL cells proximal Wnt signaling by reducing the levels of the Wnt coreceptor LRP6 and by downregulating the expression of the Wnt target genes LEF1, cyclin D1, and fibronectin. | First demonstration that salinomycin inhibits Wnt signaling in human cancer cells (CLL cells). | [126] |

|

| ||||

| Human metastatic breast cancer | Triple negative invasive ductal breast carcinoma cells from subcutaneous metastases obtained by biopsy from a 40-year-old patient with metastatic (bone and subcutaneous metastasis) breast cancer, treated systemically with salinomycin intravenously. | Systemic salinomycin treatment induces apoptosis in the cells of the metastases as evidenced in biopsies by molecular histopathology. Salinomycin treatment induces regression of metastases, partial clinical response, and decrease of the tumor markers Ca 15-3 and CEA in metastatic triple negative invasive ductal breast cancer. |

First demonstration that salinomycin induces breast cancer metastasis regression in humans and has clinical activity in human metastatic breast cancer. First demonstration that salinomycin can be safely administered intravenously in humans. Phase I/II clinical trial in triple negative breast cancer patients envisioned to start in 2013. |

[104] |

|

| ||||

| Human metastatic vulvar cancer | Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, 82-year-old patient with locally advanced and metastatic (pelvic lymphatic metastasis) vulvar cancer, treated systemically with salinomycin intravenously. | Systemic salinomycin treatment induces tumor regression, partial clinical response, and decrease of the tumor marker SCC in advanced vulvar cancer. | Increased clinical antitumor activity of salinomycin in combination with erlotinib. | [105] |

4. From Broiler to Bedside: A Brief History of Salinomycin

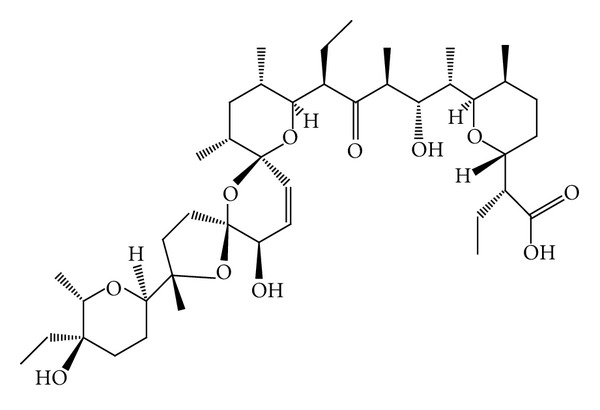

During the course of a screening program for new antibiotics in the early seventies, Miyazaki and colleagues from the research division of Kaken Chemicals Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan isolated a new biologically active substance from the culture broth of Streptomyces albus strain no. 80614 that was termed salinomycin [102]. The salinomycin-producing organism was detected in and isolated from a soil sample collected at Fuji City, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan, taxonomically classified as a member of the Streptomyces albus genus (ROSSI-DORIA) WAKSMAN and HENRICI and designated as the strain no. 80614 [102, 135]. The production of salinomycin was carried out by tank fermentation, filtration of the culture broth of Streptomyces albus strain no. 80614, purification by column chromatography on alumina/silica gel and subsequent elution. The eluate was then concentrated in vacuo, dried, and finally crystallized. By this isolation procedure, salinomycin was obtained in the form of colourless prism of the sodium salt [102]. Subsequently, it was demonstrated that salinomycin exhibits antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria including Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococcus flavus, Sarcina lutea, Mycobacterium spp., some filamentous fungi, Plasmodium falciparum, and Eimeria spp., protozoan parasites responsible for the poultry disease coccidiosis [102, 136, 137]. The chemical structure of salinomycin was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis, which revealed that salinomycin was a new member of the family of the monocarboxylic polyether antibiotics [103], (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural formula of salinomycin. The pentacyclic molecule with a unique tricyclic spiroketal ring system has a mass of 751 Da, a molecular formula of C42H70O11, a melting point of 113°C, and a UV absorption at 285 nm. Adapted from [102, 103], with permission from Elsevier B.V.

Because other polyether antibiotics, such as monensin and lasalocid, had previously been shown to exhibit effective antimicrobial activities against Eimeria spp., the anticoccidial estimation of salinomycin was carried out with chickens infected with Eimeria tenella oocysts. Salinomycin was effective in reducing the mortality of chickens from coccidiosis and in increasing average body weight of treated infected chickens [102]. Thus, a patent had been issued for the use of salinomycin to prevent coccidiosis in poultry [138], and, up to today, salinomycin is used in broiler batteries and other livestock as an anticoccidial drug and is also fed to ruminants and pigs to improve nutrient absorption and feed efficiency [136, 139–142].

In addition, salinomycin had early been shown to act in different biological membranes, including cytoplasmic and mitochondrial membranes, as a monovalent cation ionophore with strict selectivity for alkali ions and a strong preference for K+ [143], thereby promoting mitochondrial and cytoplasmic K+ efflux and inhibiting oxidative phosphorylation [144, 145]. Similar to the monocarboxylic polyether antibiotic monensin, which exhibits complex cardiovascular effects due to its transport of Na+ across biological membranes [146], salinomycin had been demonstrated by Pressman and colleagues as a positive ionotropic and chronotropic agent that increased cardiac output, left ventricular systolic pressure, heart rate, mean arterial pressure, coronary artery vasodilatation and blood flow, and plasma catecholamine concentration [147]. These results had been obtained in experiments with mongrel dogs that had received a single intravenous injection of 150 μg·kg−1 salinomycin [147]. The total synthesis of the salinomycin molecule was achieved in 1998 [148], and amide derivatives of salinomycin with activity against Gram-positive bacteria and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus have been synthesized very recently [149].

However, for several reasons, salinomycin has never been established as a drug for human diseases until now. In particular, several reports and studies published in the last three decades revealed a considerable toxicity of salinomycin in mammals, such as horses, pigs, cats, and alpacas after accidental oral or inhalative intake [150–154]. A case of an accidental inhalation and swallowing of about 1 mg·kg−1 salinomycin by a 35-year-old male human revealed severe acute and chronic salinomycin toxicity with acute nausea, photophobia, leg weakness, tachycardia and blood pressure elevation and a chronic (day 2 to day 35) creatine kinase elevation, myoglobinuria, limb weakness, muscle pain, and mild rhabdomyolysis [155]. Risk assessment data recently published by the European Food Safety Authority declare an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 5 μg·kg−1 salinomycin for humans, because daily intake of more than 500 μg·kg−1 salinomycin by dogs leads to neurotoxic effects, such as myelin loss and axonal degeneration [156].

In view of this considerable toxicity in mammals, salinomycin has only been used for more than 30 years as a coccidistat and growth promoter in livestock, but, in terms of human drug development salinomycin rested in dormancy. Until in 2009 a seminal study by Gupta and colleagues revealed that salinomycin selectively eliminates human breast CSCs in mice [128]. A follow-up publication demonstrated that salinomycin induces massive apoptosis in human cancer cells of different origin that display multiple mechanisms of drug and apoptosis resistance [125]. Based on these findings, salinomycin was therapeutically applicated “first-in-man” in 2010, in the context of a pilote clinical trial with a small cohort of patients with metastatic breast, ovarian, and head and neck cancers [104]. Intravenous administration of 200–250 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day for three weeks resulted in partial regression of tumor metastasis and showed only minor acute and long-term side effects, but no severe acute and long-term side effects observed with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs [104]. Consequently, a phase I/II clinical trial with VS-507 (a proprietary formulation of salinomycin produced by Verastem Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) in patients with triple negative breast cancer is envisioned to start in 2013. However, it is actually unclear whether salinomycin will be used routinely for the treatment of cancer patients in the very next years.

5. Salinomycin as a Drug for Targeting CSCs

It was a great surprise when Gupta and colleagues showed in 2009 that salinomycin selectively kills human breast CSCs [128]. In a sophisticated experimental approach, the authors used triple oncogenic transformed and immortalized human mammary epithelial cells (termed HMLER), in which knockdown of E-cadherin by RNA interference resulted in the generation of cells undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a latent embryonic program that can endow cancer cells with migratory, invasive, self-renewal and drug resistance capabilities [157–160]. These human breast cancer stem-like cells (termed HMLER-shEcad) that displayed characteristic properties of CSCs were capable of forming tumorspheres in suspension cultures (a standard clonogenic assay for the detection of self-renewal of CSC, [9]), showed high and low expression of CD44 and CD24, respectively, and exhibited resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs and cytotoxic agents, such as paclitaxel, doxorubicin, actinomycin D, campthotecin, and staurosporine [128]. In a high-throughput screening approach, about 16,000 compounds from chemical libraries, including biological molecules and natural extracts with known bioactivity, were tested for activity and toxicity against HMLER-shEcad cells and control cells that had not undergone EMT. From a pool of 32 promising candidates, only one compound markedly and selectively reduced the viability of breast cancer stem-like HMLER-shEcad cells: salinomycin. It was further demonstrated that salinomycin, in contrast to the anti-breast cancer drug paclitaxel, selectively reduces the proportion of CD44high/CD24low CSCs in cultures of mixed populations of HMLER-shEcad cells and control cells that had not undergone EMT. In addition, pretreatment of HMLER-shEcad cells with salinomycin resulted in inhibition of HMLER-shEcad-induced tumorsphere formation, which was not observed after pretreatment of the cells with paclitaxel [128]. Using comparative global gene expression profiling, it was shown that, in CD44high/CD24low HMLER cells, salinomycin, but not paclitaxel, was capable of changing gene expression signatures characteristic of breast CSCs or mammary epithelial progenitor cells isolated from human breast cancers. In particular, expression of genes that inversely correlates with metastasis-free survival, overall survival, and clinical outcome of breast cancer patients [161, 162] was downregulated by salinomycin. Expression of a set of genes that promote the expansion of mammary epithelial stem cells and the formation of tumorspheres [163] was also markedly downregulated by salinomycin but not by paclitaxel. In contrast, genes involved in mammary epithelial differentiation that encode membrane-associated and secreted proteins of the extracellular matrix were upregulated by salinomycin [128]. Finally, as a proof of principle, it was demonstrated that salinomycin inhibits the ability of breast CSCs to form tumors in mice. Pretreatment of HMLER cells for 7 days with salinomycin and subsequent serial limiting dilution and injection of the cells into NOD/SCID mice resulted in a >100-fold decrease in tumor-seeding ability, relative to pretreatment of the cells with paclitaxel. Finally, salinomycin treatment of NOD/SCID mice with human breast cancers (xenograft mice) resulted in a reduction of the tumor mass and metastasis, and explanted tumors showed a reduced number of breast CSCs as well as an increased epithelial differentiation [128].

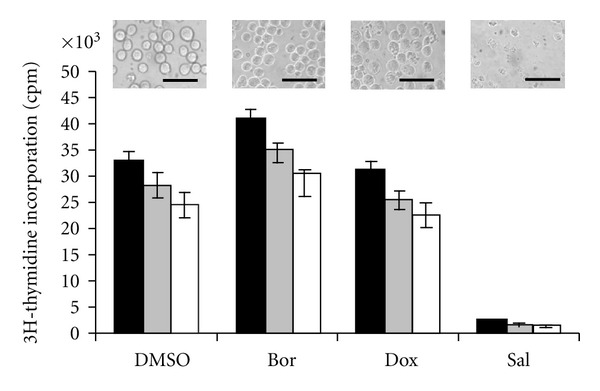

According to the primary finding that salinomycin induces massive apoptosis in human cancer cells that display different mechanisms of drug and apoptosis resistance [125], a subsequent study demonstrated that salinomycin is able to overcome ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance and apoptosis resistance in human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells (AML SCs) [16]. One of the most important mechanism of drug resistance in leukemia SCs and other CSCs is the expression of ABC transporters belonging to a highly conserved superfamily of transmembrane proteins capable of exporting a wide variety of macromolecules and structurally unrelated chemotherapeutic drugs from the cytosol, thereby conferring multidrug resistance, which is a major obstacle in the success of cancer chemotherapy [14, 17, 164, 165]. As demonstrated in the study, expression of functional ABC transporters, such as P-glycoprotein/MDR1, ABCG2/BCRP, and ABCC11/MRP8 in human KG-1a AML SCs confers resistance of the cells to various chemotherapeutic drugs, including cytosine arabinoside, doxorubicin, gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, topotecan, etoposide, and bortezomib, but not to salinomycin, which was capable of inducing massive apoptosis in KG-1a AML SCs [16]. Of note, salinomycin did not permit long-term adaptation and development of resistance of KG-1a AML SCs to apoptosis-inducing concentrations of salinomycin, whereas the cells could readily be adapted to survive and to proliferate in the presence of initially apoptosis-inducing concentrations of doxorubicin and bortezomib [16], (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Salinomycin does not permit long-term adaptation and development of resistance of KG-1a AML SCs to apoptosis-inducing concentrations of salinomycin (Sal, 10 μM), whereas the cells could be readily adapted to survive and to proliferate in the presence of initially apoptosis-inducing concentrations of doxorubicin (Dox, 0.5 μg/mL) and bortezomib (Bor, 12.5 nM). After 12 weeks of culturing in the presence of 12.5 nM Bor, 0.5 μg/mL Dox, 10 μM Sal, or DMSO 5% (v/v), proliferation of the cells was determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation for 24 h. White bars: KG-1a AML SCs; grey bars: KG-1a AML cells; black bars: KG-1 AML cells. Inserts show invert microscopic pictures (400x) of KG-1a AML SCs cultured for 12 weeks in the presence of the drugs noted below. Size bars are 50 μm. Adapted from [16], with permission from Elsevier B.V.

These findings strongly suggest that salinomycin is capable of targeting breast CSCs and AML SCs, and a series of recent studies show similar effects of salinomycin in other types of CSCs. In gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), the most common gastrointestinal sarcomas, a subpopulation of cells expressing CD44, CD34, and low Kit (activating stem cell factor receptor) have been identified as cells with self-renewal and tumorigenic capabilities [84]. These Kitlow CD44+ CD34+ CSCs are resistant to inhibition of proliferation by imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting oncogenic kit signaling that is commonly used in the treatment of metastatic GIST [84, 166]. By contrast, salinomycin nearly completely inhibited the proliferation of Kitlow CD44+ CD34+ CSCs without causing apoptosis, and salinomycin also promoted differentiation of the cells, as evidenced by the occurrence of multipolarity and a fibroblast-like morphology [84]. However, a combined treatment of the cells with imatinib and salinomycin caused a significantly greater inhibition of proliferation than salinomycin alone [84]. Thus, the study demonstrates that salinomycin is able to inhibit proliferation and to induce differentiation of GIST CSCs and also suggests that a combination of salinomycin and imatinib may provide therapeutic benefit in patients with GIST.

Similar results were obtained with CD44+ CD24− ALDH1+ breast CSCs isolated from the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. In CD44+ CD24− ALDH1+ MCF-7-derived breast CSCs, salinomycin was capable of markedly reducing the tumorsphere formation of the cells and the percentage of ALDH1+ expressing cells by nearly 50-fold [85]. Treatment of the cells with salinomycin as well as combined treatment with the cytostatic drug doxorubicin and salinomycin, but not treatment with doxorubicin alone, reduced the cloning efficiency by 10–30-fold and markedly increased apoptosis in CD44+ CD24− ALDH1+ breast CSCs [85]. Similar results were obtained recently with MCF-7-derived breast CSCs and HER2-expressing breast cancer cells that were more effectively killed by the combination of salinomycin and the anti-HER2 antibody trastuzumab than by salinomycin or trastuzumab alone [86], providing further evidence that salinomycin alone and particularly in combination with conventional anticancer drugs effectively targets CSCs.

Salinomycin has recently been shown to target CSCs in different types of human cancers, including gastric cancer [131], lung adenocarcinoma [130], osteosarcoma [132], colorectal cancer [129], squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [133], and prostate CSCs [134], suggesting that salinomycin may be effective in CSCs of many, if not all, types of human cancers, although it is currently not known whether all cancers contain subpopulations of CSCs.

In ALDH1+ gastric CSCs, which displayed resistance to the conventional chemotherapeutic drugs 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin, salinomycin effectively inhibited tumorsphere formation, proliferation, and viability of the cells [131]. Similar results were obtained in ALDH1+ CSCs derived form lung adenocarcinoma cells [130] and in osteosarcoma CSCs [132]. In colorectal cancer cells and in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cells, salinomycin, but not oxaliplatin or cisplatin, was able to significantly reduce the proportion of CSCs, as detected in tumorsphere assays [129, 133] and in human SCC xenograft mice [133].

As noted above, cure of cancer requires the eradication of all cell types within a cancer, namely, CSCs, more differentiated progenitors and the bulk tumor cell population that might be achieved by combining CSC targeting agents with conventional cytotoxic drugs [74, 75, 83]. This hypothesis received substantial support from recent studies showing that salinomycin in combination with a conventional cytotoxic drug eradicates human cancers in xenograft mice much more efficiently than the single agent [87, 88]. In particular, salinomycin inhibited the growth of CD133+ pancreatic CSCs in tumorsphere formation assays, while the cytotoxic drug gemcitabine, a nucleoside analog commonly used in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer, induced marked apoptosis in non-CSC 133-pancreatic cancer cells [87]. Consistently, salinomycin combined with gemcitabine eradicated human pancreatic cancer in xenograft mice much more efficiently than either salinomycin or gemcitabine alone [87]. Similar results were obtained in a study using CD44+ CD24− breast CSCs sorted from the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 [88]. Salinomycin more efficiently inhibited the proliferation of CD44+ CD24− breast CSCs than of the parental MCF-7 cells, and salinomycin was able to induce significant tumor regression and to reduce the number of CD44+ CD24− breast CSCs in tumors established by MCF-7 cells in xenograft mice [88]. Of note, salinomycin in combination with paclitaxel almost completely eradicated the MCF-7 tumors in xenograft mice [88].

There is growing evidence that salinomycin not only targets CSCs, but also kills more differentiated non-CSC tumor cells and, most importantly, cancer cells that display efficient mechanisms of resistance to cytotoxic drugs, radiation, and induction of apoptosis. Salinomycin has been shown to induce massive apoptosis in acute T-cell leukemia cells [125] and chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells [126] isolated from leukemia patients but failed to induce apoptosis in normal human T cells and peripheral blood lymphocytes isolated from healthy individuals [125, 126]. In different human cancer cells exhibiting resistance to cytotoxic drugs, radiation, and apoptosis, salinomycin has been demonstrated to induce significant apoptosis and to increase DNA damage [89, 125, 167]. As in the case of breast CSCs, pancreatic CSCs, and GIST CSCs [84–88], salinomycin is able to enhance in regular cancer cells the cytotoxic effects of conventional cancer drugs and novel tumor-targeted drugs, such as doxorubicin, gemcitabine, etoposide, paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinblastine, and trastuzumab [86, 87, 89, 90], envisioning a central role for salinomycin-based combination therapies in the future treatment of cancer [109].

6. Mechanisms of Salinomycin's Action against CSCs

Although the exact mechanisms underlying the elimination of CSCs by salinomycin remain poorly understood, recent work has contributed to an increased understanding of some mechanisms and modes of action of salinomycin in human CSCs and cancer cells.

6.1. Induction of Apoptosis and Cell Death

It has been shown that salinomycin induces apoptosis in CSCs of different origin [16, 85, 132], but the particular mechanisms of apoptosis induction by salinomycin in CSCs remain unclear and may differ among the cell type, as demonstrated for cancer cells of different origin [89, 90, 125, 127]. In particular, salinomycin-induced apoptosis in human KG-1a AML SCs and Molt-4 T-cell leukemia cells is caspase independent [16, 125], whereas salinomycin has been shown to activate the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis and the caspase-3-mediated cleavage of PARP in human PC-3 prostate cancer cells [127]. Salinomycin is able to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) in prostate cancer cells [127, 134]. Interestingly, salinomycin-mediated generation of ROS leads to apoptosis in PC-3 prostate cancer cells [127], whereas VCaP and LNCaP prostate cancer cells display growth inhibition but not apoptosis induction in response to salinomycin-induced ROS generation [134]. Salinomycin-induced apoptosis is not accompanied by cell cycle arrest in human Molt-4 leukemia cells [125] that is rather unusual, because, in many types of cancer cells, cell cycle arrest precedes apoptosis induced by different agents. Notably, to date there is only one report available showing that salinomycin induces rather nonapoptotic cell death than apoptotic cells death, as demonstrated by the loss of viability and weak cleavage of PARP in human Hs578T breast cancer cells exposed to salinomycin [90]. However, combination treatment of the cells with salinomycin and paclitaxel or salinomycin and docetaxel resulted in the induction of marked cleavage of PARP and induction of apoptosis that was not observed after treatment of the cells with either drug alone [90]. These data suggest that induction of apoptosis or nonapoptotic cell death by salinomycin in cancer cells seems to be dependent on the particular cell type investigated, and the detailed mechanisms of salinomycin-induced apoptosis and nonapoptotic cell death in cancer cells are far from being clear to date. Salinomycin has been shown to induce apoptosis in CSCs derived from human acute myeloid leukemia cells [16], breast cancer cells [85], and osteosarcoma cells [132]. Whether salinomycin is able to induce apoptosis or rather nonapoptotic cell death in CSCs derived from other types of human cancers is currently unknown.

6.2. Interference with ABC Transporters

It is evident that salinomycin is refractory to the action of ABC transporters since salinomycin is able to overcome ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance in AML SCs [16]. Salinomycin is a 751 kDa transmembrane K+ ionophore which is rapidly embedded in biological membranes such as the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial membrane [144]. ABC transporters also constitute transmembrane macromolecules that extrude a variety of substrates from the cytosol [14, 17, 164]. Therefore it is unlikely that salinomycin becomes a substrate of ABC transporters [16]. Moreover, salinomycin has been demonstrated to be a potent inhibitor of the ABC transporter P-glycoprotein/MDR1 in different cancer cells [167, 168].

6.3. Activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

Constitutive activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is essential for maintenance, clonogenicity and other specific characteristics of CSCs [18–21, 169, 170] and, most importantly, Wnt/β-catenin signaling confers resistance of CSCs to radiation [171, 172] and to anticancer drugs [18, 19]. Salinomycin, however, has been shown to inhibit in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells proximal Wnt signaling by reducing the levels of the Wnt coreceptor LRP6 and by downregulating the expression of the Wnt target genes LEF1, cyclin D1, and fibronectin, finally leading to apoptosis [126].

6.4. Inhibition of Oxidative Phosphorylation

Most cancer cells rely more on aerobic glycolysis than on oxidative phosphorylation (the Warburg effect) [173], but, for instance, malignant transformation of human mesenchymal stem cells is linked to an increase of oxidative phosphorylation [174]. Moreover, glioma CSCs have been shown to mainly rely on oxidative phosphorylation [175], suggesting that inhibition of metabolic pathways, such as oxidative phosphorylation, is a promising strategy to target CSCs. In this context, salinomycin is known to inhibit oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria [144] that may contribute to the elimination of CSCs by salinomycin.

6.5. Cytoplasmic and Mitochondrial K+ Efflux

Salinomycin is a K+ ionophore that interferes with transmembrane K+ potential and promotes the efflux of K+ from mitochondria and cytoplasm [143–145]. Expression of K+ channels has been documented in CD34+/CD38− AML SCs and in CD133+ neuroblastoma CSCs, but not in their nontumorigenic counterparts [176, 177], suggesting an important role of K+ channels in CSC maintenance. Moreover, a decrease in intracellular K+ concentration by pharmacological induction of K+ efflux is directly linked to the induction of apoptosis and cytotoxicity in cancer cells [178, 179], suggesting that mitochondrial and cytoplasmic K+ efflux induced by salinomycin leads to apoptosis in CSCs.

6.6. Differentiation of CSCs

Finally, salinomycin is able to promote differentiation of CSCs and to induce epithelial reprogramming of cells that had undergone EMT [84, 128]. This is in concert with the finding that salinomycin upregulates the expression of genes involved in mammary epithelial differentiation [128]. Thus, salinomycin might target and eliminate CSCs by multiple mechanisms of which only a few are currently known. Future research may uncover an increasing number of relevant mechanisms of targeting CSCs by salinomycin.

7. Selected Case Reports from Clinical Pilote Studies

7.1. Case 1

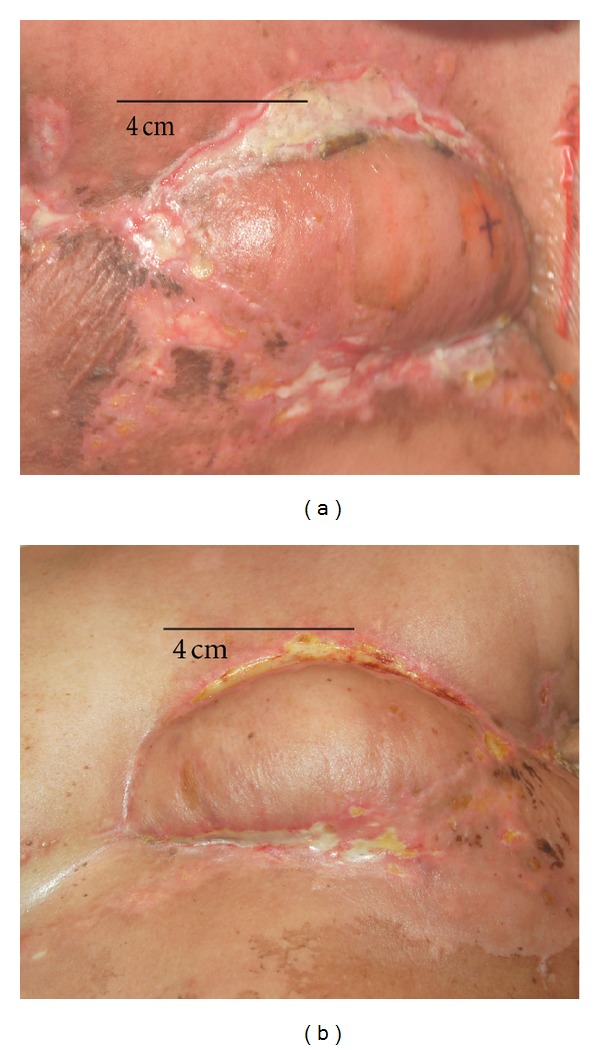

40-Year-Old Female Patient with Metastatic (Bone and Subcutaneous) Invasive Ductal Breast Cancer. Diagnosis, histopathology, and first staging were obtained after mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection 30 month before salinomycin treatment: invasive ductal breast carcinoma. TNM staging: pT1c, pN0, M0, G2. Estrogen receptor (ER): 40% expression, progesterone receptor (PR): 30% expression, HER2 score: 1+. After induction therapy with six cycles of polychemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamid and subsequent pituitary gonadotropin blockade with leuprorelin, the patient experienced vertebral bone metastasis and a subcutaneous multifocal thoracal tumor recidive (histopathology: ER, PR, and HER2 negative, “triple negative”), which was widely resected. The half thorax was subsequently irradiated with a cumulative dose of 50.4 Gy, and a latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap was used for breast reconstruction. Three month before salinomycin treatment, the patient displayed in the contralateral breast an invasive ductal triple negative breast carcinoma with axillary lymph node metastases that was treated with radiation (cumulative dose 50.4 Gy). Because of poor therapeutic response and exhausted therapeutic options, an experimental therapy with salinomycin was recommended. After informed consent, the patient received 12 intravenous administrations of 200 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day. As shown in Figure 3, systemic salinomycin therapy induced a marked regression of the subcutaneous thoracal metastases. A biopsy of the regressive subcutaneous thoracal metastases was obtained after 12 cycles of salinomycin therapy, and the specimen was investigated by molecular histopathology. As determined by TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) histopathology, ~85% of the cells had undergone apoptosis. Moreover, the serum levels of the tumormarkers Ca 15-3 (cut off <31 U/mL) and CEA (cut off <3.4 ng/mL) declined from 14.3 U/mL and 50.8 ng/mL before salinomycin therapy to 7.2 U/mL and 15.5 ng/mL after salinomycin therapy, respectively. Intravenous salinomycin therapy resulted in minor acute side effects, including tachycardia and mild tremor for 30–60 min. after administration but lacked severe and long-term side effects observed with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs, such as myelodepression, neutropenia, alopecia, nausea and vomiting, or gastrointestinal, thromboembolic, and neurological side effects. Similar results of salinomycin-induced partial tumor and metastasis regression were obtained in three other patients with metastatic breast cancer, one patient with metastatic ovarian cancer, and one patient with metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 3.

Breast cancer metastasis regression by salinomycin. Orthotopic subcutaneous metastases after mastectomy in a 40-year-old female patient (see Section 7.1. Case 1) with metastatic invasive ductal breast carcinoma, triple negative (estrogen receptor: negative, progesterone receptor: negative, HER2: negative). (a) before, (b) after 12 intravenous administrations of 200 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day. Adapted from [104].

7.2. Case 2

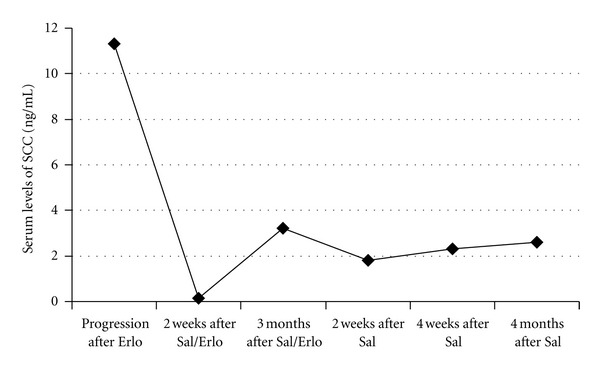

82-Year-Old Female Patient with Advanced and Metastatic (Pelvic Lymphatic Metastasis) Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva. Diagnosis, histopathology, and first staging were obtained after radical vulvectomy and bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection 18 month before salinomycin treatment: pT1b, pN2b, M0, G2. Subsequently, pelvic and inguinal irradiation with a cumulative dose of 59.4 Gy was performed. Ten month later, the patient experienced a local recidive, which was surgically removed, and histopathology revealed that the recurrent tumor was less differentiated (G3) than the initial tumor (G2). Four month later, the patient experienced again a local recidive which was treated with radiotherapy with a cumulative dose of 39 Gy. Because local tumor progression occurred after the radiotherapy, the patient was treated with 150 mg/day erlotinib (an orally epithelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor) for 30 days. The treatment with erlotinib resulted in a slow but significant disease progression as determined by clinical inspection of the local tumor and elevation of the serum levels of the tumor marker SCC. Because of poor therapeutic response and exhausted therapeutic options, an experimental therapy with salinomycin combined with erlotinib was recommended. After informed consent, the patient received 14 intravenous administrations of 200 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day combined with 150 mg erlotinib every day for 30 days. This simultaneous combination therapy resulted in significant tumor regression as determined by clinical inspection of the local tumor and decrease of SCC serum levels from 11.3 ng/mL before therapy to 0.13 ng/mL after therapy (cut off SCC: <1.9 ng/mL). Three month after administration of the combination therapy (salinomycin and erlotinib for 30 days), the patient displayed significant tumor progression as determined by clinical inspection and elevation of SCC serum levels to 3.2 ng/mL (Figure 4). The patient refused a further therapy containing erlotinib due to marked adverse effects of erlotinib (fatigue, nausea, anorexia, and inappetance) experienced during initial therapy with salinomycin combined with erlotinib. Therefore, the patient received 12 intravenous administrations of 250 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day, without addition of erlotinib. This monotherapy with salinomycin resulted in stable disease and no progression for 4 months, as determined by clinical inspection of the local tumor and no significant changes of SCC serum levels (Figure 4). As observed in case 1, intravenous therapy with 250 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day resulted in minor acute side effects, including tachycardia and mild tremor for 30–60 min. after administration but lacked severe and long-term side effects, such as myelodepression, neutropenia, alopecia, nausea and vomiting, or gastrointestinal, thromboembolic, and neurological side effects.

Figure 4.

Serum levels of the tumor marker SCC (squamous cell carcinoma antigen) determined in an 82-year-old female patient with advanced vulvar carcinoma (see Section 7.2. Case 2) at various time points: at tumor progression after 150 mg/day erlotinib for 30 days (progression after Erlo); at tumor regression 2 weeks after 14 intravenous administrations of 200 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day combined with 150 mg erlotinib every day for 30 days (2 weeks after Sal/Erlo); at tumor progression 3 months after 14 intravenous administrations of 200 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day combined with 150 mg erlotinib every day for 30 days (3 months after Sal/Erlo); at stable disease 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 4 months after 12 intravenous administrations of 250 μg·kg−1 salinomycin every second day, without addition of erlotinib (2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 4 months after Sal). Adapted from [105].

8. Conclusions

Work from the last few years highlights the possibility of selectively targeting CSCs, which are regarded as the major culprits in cancer. However, although the rather novel CSC concept of carcinogenesis is fairly accepted to date, more classical mechanisms and driving forces of carcinogenesis, including genome instability, epigenetic modifications, first oncogenic hit(s), clonal evolution, replicative immortality, invasion and metastasis, immune evasion, reprogramming of energy metabolism, and most probably, a complex interplay of all of these mechanisms must be considered as a basis for defining carcinogenesis and cancer in general [73, 80, 180–185]. Nevertheless, in line with the CSC concept of carcinogenesis [1, 3, 4, 7–9, 73], CSCs constitute adequately characterized cells and represent novel and translationally relevant targets for cancer therapy [5, 65, 74, 75].

Significant advances have been made recently in the discovery, development, and validation of novel compounds and drugs that target CSCs, and the future clinical use of these novel agents may represent a powerful strategy for eradicating CSCs in cancer patients, thereby preventing tumor recurrence and metastasis, and, hopefully, contributing to the cure of cancer. There is growing consensus that conventional cytotoxic drugs are unable to eradicate CSCs [5, 12, 64, 74], and, more disturbing, CSCs can be even selectively enriched by these drugs, as demonstrated in breast cancer patients receiving systemic chemotherapy comprising conventional cytotoxic drugs [10, 67, 68, 186]. Moreover, many novel tumor-targeted drugs, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies raised against tumor-specific cell surface proteins, also fail to eliminate CSCs [70, 95, 187–189], so that there is an urgent need for novel compounds and drugs that effectively target CSCs for the use in elaborated clinical settings and preferably in combination with conventional cytostatic drugs and novel tumor-targeted agents.

In this context, one promising candidate drug is the ionophor antibiotic salinomycin, which has recently been documented to effectively eliminate CSCs in different types of human cancers in vitro and in xenograft mice bearing human cancers [87, 88, 128, 133]. To date it is not entirely clear by which mechanisms salinomycin eliminates CSCs, but it is important to note that salinomycin, in combination with conventional cytotoxic drugs, is much more effective in eradicating human cancers in xenograft mice than the single agent alone [87, 88]. This is in accord with the postulation that efficient cancer therapy should target all cancer cell populations, including CSCs, more differentiated progenitors, and bulk tumor cells that might be achieved by combining CSC targeting agents with conventional cytotoxic drugs, novel tumor-targeted drugs, and radiation therapy [5, 74, 82].

Importantly, salinomycin is not only able to kill CSCs, but also regular tumor cells and highly indolent tumor cells displaying resistance to cytotoxic drugs, radiation, and induction of apoptosis [85, 125, 167], hence salinomycin can be regarded as a triple-edged sword against cancer. This is in line with results from a few clinical pilote studies revealing that salinomycin is able to induce partial clinical regression of heavily pretreated and therapy-resistant cancers, particularly in combination with novel tumor-targeted drugs [104, 105]. More work is required to define the exact mechanisms of salinomycin's action against CSCs, to estimate its long-term safety in humans, and finally, to exploit its probably huge therapeutic potential in combination with other drugs in all stages of human cancer.

References

- 1.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pardal R, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ. Applying the principles of stem-cell biology to cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3(12):895–902. doi: 10.1038/nrc1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward RJ, Dirks PB. Cancer stem cells: at the headwaters of tumor development. Annual Review of Pathology. 2007;2:175–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dick JE. Stem cell concepts renew cancer research. Blood. 2008;112(13):4793–4807. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-077941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank NY, Schatton T, Frank MH. The therapeutic promise of the cancer stem cell concept. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120(1):41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI41004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermann PC, Bhaskar S, Cioffi M, Heeschen C. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2010;20(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clevers H. The cancer stem cell: premises, promises and challenges. Nature Medicine. 2011;17(3):313–319. doi: 10.1038/nm.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magee JA, Piskounova E, Morrison SJ. Cancer stem cells: impact, heterogeneity, and uncertainty. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(3):283–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, et al. Cancer stem cells—perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Research. 2006;66(19):9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creighton CJ, Li X, Landis M, et al. Residual breast cancers after conventional therapy display mesenchymal as well as tumor-initiating features. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(33):13820–13825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905718106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tehranchi R, Woll PS, Anderson K, et al. Persistent malignant stem cells in del(5q) myelodysplasia in remission. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(11):1025–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber JM, Smith BD, Ngwang B, et al. A clinically relevant population of leukemic CD34+CD38-cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(15):3571–3577. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-364182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An Y, Ongkeko WM. ABCG2: the key to chemoresistance in cancer stem cells? Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism and Toxicology. 2009;5(12):1529–1542. doi: 10.1517/17425250903228834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean M. ABC transporters, drug resistance, and cancer stem cells. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2009;14(1):3–9. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calcagno AM, Salcido CD, Gillet JP, et al. Prolonged drug selection of breast cancer cells and enrichment of cancer stem cell characteristics. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(21):1637–1652. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuchs D, Daniel V, Sadeghi M, Opelz G, Naujokat C. Salinomycin overcomes ABC transporter-mediated multidrug and apoptosis resistance in human leukemia stem cell-like KG-1a cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010;394(4):1098–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moitra K, Lou H, Dean M. Multidrug efflux pumps and cancer stem cells: insights into multidrug resistance and therapeutic development. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2011;89(4):491–502. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng Y, Wang X, Wang Y, Ma D. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates cancer stem cells in lung cancer A549 cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010;392(3):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeung J, Esposito MT, Gandillet A, et al. β-catenin mediates the establishment and drug resistance of MLL leukemic stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(6):606–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takebe N, Harris PJ, Warren RQ, Ivy SP. Targeting cancer stem cells by inhibiting Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2011;8(2):97–106. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janikowa M, Skarda J. Differentiation pathways in carcinogenesis and in chemo- and radioresistance. Neoplasma. 2012;59(1):6–17. doi: 10.4149/neo_2012_002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao C, Chen A, Jamieson CH, et al. Hedgehog signalling is essential for maintenance of cancer stem cells in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2009;458(7239):776–779. doi: 10.1038/nature07737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobune M, Takimoto R, Murase K, et al. Drug resistance is dramatically restored by hedgehog inhibitors in CD34+ leukemic cells. Cancer Science. 2009;100(5):948–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Li Y, Kong D, et al. Acquisition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells is linked with activation of the notch signaling pathway. Cancer Research. 2009;69(6):2400–2407. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma S, Lee TK, Zheng BJ, Chan KW, Guan XY. CD133+ HCC cancer stem cells confer chemoresistance by preferential expression of the Akt/PKB survival pathway. Oncogene. 2008;27(12):1749–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. Regulation of mammary stem/progenitor cells by PTEN/Akt/β-catenin signaling. PLoS Biology. 2009;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000121.e1000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallmeier E, Hermann PC, Mueller MT, et al. Inhibition of ataxia telangiectasia- and Rad3-related function abrogates the in vitro and in vivo tumorigenicity of human colon cancer cells through depletion of the CD133+ tumor-initiating cell fraction. Stem Cells. 2011;29(3):418–429. doi: 10.1002/stem.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hambardzumyan D, Becher OJ, Rosenblum MK, Pandolfi PP, Manova-Todorova K, Holland EC. PI3K pathway regulates survival of cancer stem cells residing in the perivascular niche following radiation in medulloblastoma in vivo. Genes and Development. 2008;22(4):436–448. doi: 10.1101/gad.1627008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill R, Wu H. PTEN, stem cells, and cancer stem cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(18):11755–11759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800071200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martelli AM, Evangelisti C, Follo MY, et al. Targeting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling network in cancer stem cells. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;18(18):2715–2726. doi: 10.2174/092986711796011201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(5):555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dylla SJ, Beviglia L, Park IK, et al. Colorectal cancer stem cells are enriched in xenogeneic tumors following chemotherapy. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002428.e2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Awad O, Yustein JT, Shah P, et al. High ALDH activity identifies chemotherapy-resistant Ewing’s sarcoma stem cells that retain sensitivity to EWS-Fli1 inhibition. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013943.e13943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Iovino F, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1-positive cancer stem cells mediate metastasis and poor clinical outcome in inflammatory breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(1):45–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips TM, McBride WH, Pajonk F. The response of CD24-/low/CD44+ breast cancer-initiating cells to radiation. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98(24):1777–1785. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. 2009;458(7239):780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ropolo M, Daga A, Griffero F, et al. Comparative analysis of DNA repair in stem and nonstem glioma cell cultures. Molecular Cancer Research. 2009;7(3):383–392. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viale A, De Franco F, Orleth A, et al. Cell-cycle restriction limits DNA damage and maintains self-renewal of leukaemia stem cells. Nature. 2009;457(7225):51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature07618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pajonk F, Vlashi E, McBride WH. Radiation resistance of cancer stem cells: the 4 R’s of radiobiology revisited. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):639–648. doi: 10.1002/stem.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guzman ML, Swiderski CF, Howard DS, et al. Preferential induction of apoptosis for primary human leukemic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(25):16220–16225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252462599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou J, Zhang H, Gu P, Bai J, Margolick JB, Zhang Y. NF-κB pathway inhibitors preferentially inhibit breast cancer stem-like cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2008;111(3):419–427. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9798-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu M, Sakamaki T, Casimiro MC, et al. The canonical NF-κB pathway governs mammary tumorigenesis in transgenic mice and tumor stem cell expansion. Cancer Research. 2010;70(24):10464–10473. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumann M, Krause M, Hill R. Exploring the role of cancer stem cells in radioresistance. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2008;8(7):545–554. doi: 10.1038/nrc2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chiou SH, Kao CL, Chen YW, et al. Identification of CD133-positive radioresistant cells in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002090.e2090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piao LS, Hur W, Kim TK, et al. CD133(+) liver cancer stem cells modulate radioresistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Letters. 2012;315(2):129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Todaro M, Alea MP, Di Stefano AB, et al. Colon cancer stem cells dictate tumor growth and resist cell death by production of interleukin-4. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(4):389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Francipane MG, Alea MP, Lombardo Y, Todaro M, Medema JP, Stassi G. Crucial role of interleukin-4 in the survival of colon cancer stem cells. Cancer Research. 2008;68(11):4022–4025. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, et al. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Molecular Cancer. 2006;5:p. 67. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kruyt FAE, Schuringa JJ. Apoptosis and cancer stem cells: implications for apoptosis targeted therapy. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2010;80(4):423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou Y, Zhou Y, Shingu T, et al. Metabolic alterations in highly tumorigenic glioblastoma cells: preference for hypoxia and high dependency on glycolysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(37):32843–32853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, et al. A perivascular Niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(1):69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Korkaya H, Liu S, Wicha MS. Breast cancer stem cells, cytokine networks, and the tumor microenvironment. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(10):3804–3809. doi: 10.1172/JCI57099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lagadec C, Vlashi E, Della Donna L, et al. Survival and self-renewing capacity of breast cancer initiating cells during fractionated radiation treatment. Breast Cancer Research. 2010;12(1):p. R13. doi: 10.1186/bcr2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reim F, Dombrowski Y, Ritter C, et al. Immunoselection of breast and ovarian cancer cells with trastuzumab and natural killer cells: selective escape of CD44high/CD24low/HER2low breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Research. 2009;69(20):8058–8066. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schatton T, Schütte U, Frank NY, et al. Modulation of T-cell activation by malignant melanoma initiating cells. Cancer Research. 2010;70(2):697–708. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu A, Wei J, Kong LY, et al. Glioma cancer stem cells induce immunosuppressive macrophages/microglia. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12(11):1113–1125. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim MR, Choi HK, Cho KB, Kim HS, Kang KW. Involvement of Pin1 induction in epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. Cancer Science. 2009;100(10):1834–1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen X, Lingala S, Khoobyari S, Nolta J, Zern MA, Wu J. Epithelial mesenchymal transition and hedgehog signaling activation are associated with chemoresistance and invasion of hepatoma subpopulations. Journal of Hepatology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao MQ, Choi YP, Kang S, Youn JH, Cho NH. CD24+ cells from hierarchically organized ovarian cancer are enriched in cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(18):2672–2680. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Essers MAG, Trumpp A. Targeting leukemic stem cells by breaking their dormancy. Molecular Oncology. 2010;4(5):443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li L, Bhatia R. Stem cell quiescence. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(15):4936–4941. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sottocornola R, Lo Celso C. Dormancy in the stem cell niche. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2012;3(2):p. 10. doi: 10.1186/scrt101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maugeri-Saccà M, Vigneri P, De Maria R. Cancer stem cells and chemosensitivity. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(15):4942–4947. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu B, Morrison R, Schleicher SM, et al. Targeting the mechanisms of resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy with the cancer stem cell hypothesis. Journal of Oncology. 2011;2011:13 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/941876.941876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malik B, Nie D. Cancer stem cells and resistance to chemo and radio therapy. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2012;4:2142–2149. doi: 10.2741/531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, et al. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131(6):1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li X, Lewis MT, Huang J, et al. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(9):672–679. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chiu PPL, Jiang H, Dick JE. Leukemia-initiating cells in human T-lymphoblastic leukemia exhibit glucocorticoid resistance. Blood. 2010;116(24):5268–5279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-292300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Ejeh F, Smart CE, Morrison BJ, et al. Breast cancer stem cells: treatment resistance and therapeutic opportunities. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(5):650–658. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Velasco-Velázquez MA, Popov VM, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG. The role of breast cancer stem cells in metastasis and therapeutic implications. American Journal of Pathology. 2011;179(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ghiaur G, Gerber J, Jones RJ. Cancer stem cells and minimal residual disease. Stem Cells. 2012;30(1):89–93. doi: 10.1002/stem.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sell S. On the stem cell origin of cancer. American Journal of Pathology. 2010;176(6):2584–2594. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou BBS, Zhang H, Damelin M, Geles KG, Grindley JC, Dirks PB. Tumour-initiating cells: challenges and opportunities for anticancer drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2009;8(10):806–823. doi: 10.1038/nrd2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McDermott SP, Wicha MS. Targeting breast cancer stem cells. Molecular Oncology. 2010;4(5):404–419. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prud’homme GJ. Cancer stem cells and novel targets for antitumor strategies. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2012;18(19):2838–2849. doi: 10.2174/138161212800626120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nguyen NP, Almeida FS, Chi A, et al. Molecular biology of breast cancer stem cells: potential clinical applications. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2010;36(6):485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lorico A, Rappa G. Phenotypic heterogeneity of breast cancer stem cells. Journal of Oncology. 2011;2011:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/135039.135039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(6):717–728. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shackleton M, Quintana E, Fearon ER, Morrison SJ. Heterogeneity in cancer: cancer stem cells versus clonal evolution. Cell. 2009;138(5):822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mueller MT, Hermann PC, Witthauer J, et al. Combined targeted treatment to eliminate tumorigenic cancer stem cells in human pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):1102–1113. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Park CY, Tseng D, Weissman IL. Cancer stem cell-directed therapies: recent data from the laboratory and clinic. Molecular Therapy. 2009;17(2):219–230. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu S, Wicha MS. Targeting breast cancer stem cells. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(25):4006–4012. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bardsley MR, Horvth VJ, Asuzu DT, et al. Kitlow stem cells cause resistance to kit/platelet-derived growth factor α inhibitors in murine gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):942–952. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gong C, Yao H, Liu Q, et al. Markers of tumor-initiating cells predict chemoresistance in breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015630.e15630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oak PS, Kopp F, Thakur C, et al. Combinatorial treatment of mammospheres with trastuzumab and salinomycin efficiently targets HER2-positve cancer cells and cancer stem cells. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27595. International Journal of Cancer. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang GN, Liang Y, Zhou LJ, et al. Combination of salinomycin and gemcitabine eliminates pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Letters. 2011;313(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang Y, Zhang H, Wang X, Wang J, Zhang X, Zhang Q. The eradication of breast cancer and cancer stem cells using octreotide modified paclitaxel active targeting micelles and salinomycin passive targeting micelles. Biomaterials. 2012;33(2):679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim JH, Chae M, Kim WK, et al. Salinomycin sensitizes cancer cells to the effects of doxorubicin and etoposide treatment by increasing DNA damage and reducing p21 protein. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;162(3):773–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim JH, Yoo HI, Kang HS, Ro J, Yoon S. Salinomycin sensitizes antimitotic drugs-treated cancer cells by increasing apoptosis via the prevention of G2 arrest. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Commununications. 2012;418(1):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nautiyal J, Kanwar SS, Yu Y, Majumdar APN. Combination of dasatinib and curcumin eliminates chemo-resistant colon cancer cells. Journal of Molecular Signaling. 2011:p. 7. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rausch V, Liu L, Kallifatidis G, et al. Synergistic activity of sorafenib and sulforaphane abolishes pancreatic cancer stem cell characteristics. Cancer Research. 2010;70(12):5004–5013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kallifatidis G, Labsch S, Rausch V, et al. Sulforaphane increases drug-mediated cytotoxicity toward cancer stem-like cells of pancreas and prostate. Molecular Therapy. 2011;19(1):188–195. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Del Barco S, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA. The anti-diabetic drug metformin suppresses self-renewal and proliferation of trastuzumab-resistant tumor-initiating breast cancer stem cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2011;126(2):355–364. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0924-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cufi S, Corominas-Faja B, Vazquez-Martin A, et al. Metformin-induced preferential killing of breast cancer initiating CD44+CD24-/low cells is sufficient to overcome primary resistance to trastuzumab in HER2+ human breast cancer xenografts. Oncotarget. 2012;3(4):395–398. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Epelbaum R, Schaffer M, Vizel B, Badmaev V, Bar-Sela G. Curcumin and gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Nutrition and Cancer. 2010;62(8):1137–1141. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2010.513802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bayet-Robert M, Kwiatkowski F, Leheurteur M, et al. Phase I dose escalation trial of docetaxel plus curcumin in patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2010;9(1) doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.1.10392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Martin-Castillo B, Dorca J, Vazquez-Martin A, et al. Incorporating the antidiabetic drug metformin in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and trastuzumab: an ongoing clinical-translational research experience at the Catalan Institute of Oncology. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21(1):187–189. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kanai M, Yoshimura K, Asada M, et al. A phase I/II study of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy plus curcumin for patients with gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2011;68(1):157–164. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rocha GZ, Dias MM, Ropelle ER, et al. Metformin amplifies chemotherapy-induced AMPK activation and antitumoral growth. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(12):3993–4005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.MacKenzie MJ, Ernst S, Johnson C, Winquist E. A phase I study of temsirolimus and metformin in advanced solid tumours. Investigational New Drugs. 2010:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9570-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miyazaki Y, Shibuya M, Sugawara H. Salinomycin, a new polyether antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1974;27(11):814–821. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.27.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kinashi H, Otake N, Yonehara H. The structure of salinomycin, a new member of the polyether antibiotics. Tetrahedron Letters. 1973;49:4955–4958. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Steinhart R, Berghauser KH, Steinhart B, Martschoke C, Hojer L, Naujokat C. Breast cancer metastasis regression by salinomycin. Case Reports in Oncology. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Steinhart B, Steinhart A, Steinhart R, Muth K, Muth M, Naujokat C. Clinical activity of salinomycin in human advanced vulvar cancer. Case Reports in Oncology. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Winquist RJ, Boucher DM, Wood M, Furey BF. Targeting cancer stem cells for more effective therapies: taking out cancer’s locomotive engine. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2009;78(4):326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kawasaki BT, Hurt EM, Mistree T, Farrar WL. Targeting cancer stem cells with phytochemicals. Molecular Interventions. 2008;8(4):174–184. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Naujokat C, Fuchs D, Opelz G. Salinomycin in cancer: a new mission for an old agent. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2010;3(4):555–559. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]