Abstract

Maternal protective responses to temperamentally fearful toddlers have previously been found to relate to increased risk for children’s development of anxiety-spectrum problems. Not all protective behavior is “overprotective,” and not all mothers respond to toddlers’ fear with protection. Therefore, the current study aimed to identify conditions under which an association between fearful temperament and protective maternal behavior occurs. Participants included 117 toddlers and their mothers, who were observed in a variety of laboratory tasks. Mothers predicted their toddlers’ fear reactions in these tasks and reported the importance of parent-centered goals for their children’s shyness. Protective behavior displayed in low-threat, but not high-threat, contexts related to concurrently observed fearful temperament and to mother-reported shy/inhibited behavior one year later. The relation between fearful temperament and protective behavior in low-threat, but not high-threat, contexts was strengthened by maternal accuracy in anticipating children’s fear and maternal parent-centered goals for children’s shyness.

Keywords: temperament, parents/parenting, toddler

Increasingly, research has focused on understanding how protective parenting, particularly by mothers, with temperamentally fearful children exacerbates risk for childhood anxiety-spectrum problems (Dadds & Roth, 2001). Much remains unknown about this association. Although recent studies have examined the importance of the context of toddlers’ fearful behavior in predicting risk (Buss, 2011; Buss, Davidson, Kalin, & Goldsmith, 2004; Rubin, Hastings, Stewart, Henderson, & Chen, 1997), similar investigations of context-specific maternal protective behavior have not followed suit. In addition, general maternal cognitive variables such as personality and parenting beliefs have received attention as correlates of parenting behavior and children’s maladjustment (e.g., Chen et al., 1998; Coplan, Arbeau, & Armer, 2008; Hastings & Rubin, 1999). Less is known about how specific cognitive characteristics regarding children’s fearfulness strengthen the association between fearful temperament and maternal protective behavior, although recent literature supports the investigation of mothers’ accuracy and goals for children’s fearful/shy behavior (Coplan, Hastings, Lagacé-Séguin, & Moulton, 2002; Kiel & Buss, 2010). Therefore, we observed maternal protective behaviors in low- and high-threat contexts and examined their unique relations to children’s concurrent fearful temperament and later shy/inhibited behavior and to maternal accuracy and goals for shyness.

Protective Parenting Behavior

Protection from distress to novelty entails removing children from contact with threat, excessive comforting that limits independent coping, discouraging interaction with novelty, or impeding autonomy (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002).

Evidence supporting the role of protective behavior in relation to children’s fearful temperament and anxiety-spectrum outcomes has accumulated over recent years. Protection and similar behaviors (e.g., “oversolicitousness,” Rubin et al., 1997) concurrently relate to fearful temperament and predict anxiety and other internalizing difficulties across early childhood (Bayer, Sanson, & Hemphill, 2006; Edwards, Rapee, & Kennedy, 2010; McShane & Hastings, 2009; Rubin, Cheah, & Fox, 2001). Moreover, protective behavior has been found to play a moderate role in the stability between fearful temperament and early shyness, on the one hand, and anxious and internalizing behaviors, on the other (Coplan, et al., 2008; Kiel & Buss, 2010; Rubin et al., 2002).

Recent investigations have challenged the idea of unidirectional parent-to-child influence; fearful/inhibited children may actively elicit protection when distressed. Children’s fearful reactions and mothers’ protective behaviors may reinforce each other over time in an “anxious-coercive cycle” that results in later impairment (Dadds & Roth, 2001). Specifically, when children experience fear or anxiety, they make demands on their parents to alleviate their distress. Children may act with great persistence or intensity, and, understandably, parents want to reduce their children’s distress, making it likely that parents respond with protectiveness. The alleviation of distress reinforces not only children’s reliance on their parents for management of their emotions and environment, but also parents’ protective responses. Longitudinal studies support this theoretical framework, finding that maternal perceptions of toddlers’ shy/inhibited behavior predict protective responses (Hastings & Rubin, 1999; Rubin, Nelson, Hastings, & Asendorpf, 1999). However, few studies have examined the correlates and consequences of observed protective behavior that occurs in direct response to children’s solicitations.

Both toddlers’ requirement of some comfort and protection and the moderate size of effects found between protective behavior and children’s anxiety-spectrum outcomes make it likely that protective parenting only facilitates this cycle under specific conditions. One such condition that has received little attention is the context in which protection is shown. Kopp’s (1989) theory of the developmental course of emotion regulation posits that toddlers’ successful management of distress advances in situations that are novel yet not overwhelmingly threatening, especially when parents do not take charge of regulation. This theory suggests context effects for parenting, such that children develop independent coping and regulation when parents provide active assistance in regulating their arousal in high-stress situations but pull back during lower-stress situations, allowing children to practice regulation skills. In support of this, Rubin and colleagues (2001) found that maternal oversolicitousness predicted social reticence positively when displayed during a low-distress free play (when protective behavior was unnecessary) but negatively when displayed during a stressful challenge. Protective behaviors across various novelty contexts remain unexamined.

Protective responses in lower-threat novelty contexts (involving less universally threatening stimuli and wider availability of coping resources) may reinforce reliance on mothers for regulation of distress, increasing the likelihood of inadequate independent regulation and subsequent fearful, inhibited responses. If indicative of an anxious-coercive cycle, protection in lower-threat contexts would then also be expected to predict continued shyness and inhibition throughout toddlerhood. Protective behavior in high-threat novelty contexts (eliciting higher levels of distress across children), on the other hand, may not be particularly maladaptive. High-threat situations may induce too much arousal for children’s independent coping, so external regulation of their emotional reactivity by mothers helps children learn adaptive self-regulation (Kopp, 1989; Calkins & Hill, 2007).

If fearful children solicit protectiveness, and protectiveness predicts continued anxiety-related behavior, protective behavior would be expected to mediate the relation between earlier and later indices of inhibition. Previous work has demonstrated this mediated effect but was limited by its restrictions placed on mothers’ behaviors (Kiel & Buss, 2010). The current study utilized a new sample to corroborate and expand upon these findings by allowing mothers to behave naturally. Replicating the previously found mediated relation under less restricted conditions is an important next step in this line of inquiry. Further, if protective behavior serves as a mechanism of stability between fearful temperament and later anxiety-spectrum behaviors, conditions influencing this pattern are important to identify.

Potential Moderators between Fearful Temperament and Protective Parenting

Maternal accuracy

An increasing number of studies have addressed how maternal cognitive characteristics relate to parenting and children’s adjustment. Constructs such as insightfulness and empathic understanding involve mothers’ descriptions of toddlers’ internal states during previous interactions (Coyne, Low, Miller, Seifer, & Dickstein, 2007; Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, Dolev, Sher, & Etzion-Carasso, 2002). However, mothers’ accuracy in anticipating children’s impending distress may specifically prompt decisive responses to toddlers’ soliticitations.

Although maternal insightfulness and empathic understanding were related to increased maternal sensitivity (Coyne et al., 2007; Koren-Karie et al., 2002), which is generally related to resiliency trajectories, and mothers’ abilities to correctly predict children’s reactions to conflict related to positive outcomes (Hastings & Grusec, 1997), different patterns may emerge for temperamentally fearful children, especially when considering fear rather than other emotions. For fearful children, highly “sensitive” (perhaps protective) behaviors have been related to trajectories of continued fearfulness, anxiety, and dependence (Arcus, 2001; Mount, Crockenberg, Bárrig Jó, & Wagar, 2010), seemingly because fearful children require more encouragement of independence for optimal outcomes (Park, Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1997). Thus, although labeled as sensitive, these behaviors may not be sensitive in that they do not lead to positive outcomes. Furthermore, parents may think differently about shyness than other behaviors (Coplan et al., 2002; Hastings & Rubin, 1999; Mills & Rubin, 1990), so accurate anticipation of their children’s fearfulness might prompt attempts to alleviate it with protective behavior. Researchers allude to a relation between mothers’ expectations of fear and protection (e.g., Hastings & Rubin, 1999; Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009). Indeed, Rubin and Burgess (2001) stated that some mothers “are highly sensitized to their children’s social and emotional characteristics, and such sensitivity may provoke well-meaning overcontrol and overinvolvement” (p. 423), suggesting that toddlers’ fearful temperament most strongly relates to mothers’ protectiveness when mothers accurately anticipate toddlers’ fearful responses.

The few existing empirical studies on maternal accuracy (Kiel & Buss, 2006, 2010) provide support for the theoretical notions mentioned above. Specifically, when mothers more accurately predicted their toddlers’ fearfulness, a stronger concurrent relation existed between toddler fearful temperament and maternal protection (Kiel & Buss, 2010). Thus, fearful toddlers may more successfully elicit protection when mothers more correctly anticipate their toddlers’ distress to novelty.

Maternal parent-centered goals

Parent-centered goals are directive and controlling, focusing on resolving the situation by demanding the child behave appropriately, immediately (Coplan et al., 2002). Rubin and colleagues have theorized that parenting beliefs, a larger category of parenting cognitions including goals, may influence whether observing or anticipating fearful behavior translates into protectiveness (Rubin et al., 2009; Rubin & Mills, 1990). Specifically, wanting a “quick fix” for shyness (due to concern about their children’s distress or its consequences) might drive some parents to attempt to immediately alleviate the child’s distress, such as by acting protectively. Rubin and Mills (1990) found that mothers of anxious children were more likely than other mothers to place importance on parent-centered goals, but the moderating role of these goals on the relation between fearful temperament and protective parenting in the context of maternal accuracy remains unexamined. It seems logical, however, that mothers of more temperamentally fearful children who not only accurately predict their children’s fearfulness, but also highly value their children behaving properly (i.e., not fearfully) as quickly as possible would behave more protectively to alleviate or prevent distress. Thus, the relation between toddler fearful temperament and maternal protective behavior would depend on both maternal accuracy and parent-centered goals, leading to the hypothesis of a three-way interaction among fearful temperament, maternal accuracy, and maternal goals in relation to protective behavior.

The moderating roles of maternal accuracy and parent-centered goals may also depend on context. The demands of high-threat contexts may prompt mothers’ protective behavior no matter their toddlers’ temperamental characteristics or mothers’ accuracy and goals for that behavior. In low-threat contexts, anticipating fearfulness and having goals to reduce shyness might prompt protective behavior with temperamentally fearful toddlers more than situational demands.

The Current Study

Given the significance of the association between toddlers’ fearful temperament and mothers’ protective behavior in the development of risk for anxiety-spectrum outcomes, the current study aimed to elucidate the conditions under which this occurs. In general, we hypothesized that protective behavior displayed in low- and high-threat contexts would relate differentially to other study variables (Hypothesis 1). Specifically, we hypothesized that protective behavior observed in low-threat contexts, but not in a high-threat context, would relate to fearful temperament (Hypothesis 1a). To further validate the differential relevance of context-specific protective behaviors, we examined how they related to maternal-report of toddlers’ shy/inhibited behavior one year later, controlling for fearful temperament. We expected that protective behavior displayed in low-threat contexts would more strongly relate to later shy/inhibited behavior than protective behavior displayed in a high-threat context (Hypothesis 1b) as well as mediate the relation between fearful temperament and later shyness/inhibition (Hypothesis 1c).

We next hypothesized that maternal accuracy in anticipating toddlers’ distress to novelty and parent-centered goals would moderate (i.e., strengthen) the relation between fearful temperament and protective behavior shown in low-threat, but not high-threat, contexts (Hypothesis 2). In other words, we predicted the existence of a three-way interaction among fearful temperament, accuracy, and goals in relation to protective behavior in low-threat contexts. In probing this interaction, we hypothesized that maternal accuracy would be a stronger moderator (i.e., the two-way interaction between maternal accuracy and fearful temperament would increase in strength) as parent-centered goals increased (Hypothesis 2a), and that, at a high level of parent-centered goals, fearful temperament would most strongly relate to protective behavior in low-threat contexts at higher levels of accuracy (Hypothesis 2b). Allowing mothers to behave more naturally, measuring protective behavior in different contexts, and examining parent-centered goals extend the literature beyond the previous research examining the role of maternal accuracy in developmental outcomes of fearful temperament.

Method

Participants

Participants included 117 2-year-old toddlers (Mage = 24.78 months, SDage = 0.74 months; 54 female) and their mothers. We recruited participants primarily from local birth records by mail (n = 100) but also in person at meetings of the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program (n = 17), a federally funded program that provides resources and education to low-income women who are pregnant or who have young children, in an attempt to increase the socioeconomic diversity of the sample. Most children (n = 95, 81%) were European American, although children from other racial/ethnic backgrounds were represented: eight (7%) African American, nine (8%) Asian American, one (1%) American Indian, and two (2%) biracial where both parents were of minority backgrounds; parents of two (2%) children described themselves as “other” without further specification. Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured by the Hollingshead Four Factor Index (Hollingshead, 1975), which is a composite of weighted scaled scores of the occupation and educational attainment of both the mother and father, if available. Scores on the index can range from 8 to 66, with higher scores indicating higher SES. Families tended to be middle-class (scores between 20 and 54), although the range of SES was represented (M = 49.74, SD = 11.93, range = 17 – 66). Of the 117 participants, 76 mothers completed a follow-up packet of questionnaires around their children’s third birthdays. After the initial mailing, follow-up phone calls were made to attempt to contact non-responders. Most families lost to attrition either moved and did not provide forwarding information or agreed to participate but did not return the questionnaire packet after multiple reminder phone calls. Families were compensated for their participation and toddlers received a small gift.

Procedure

The current study involved a laboratory visit at age 2 and questionnaire completion at ages 2 and 3. Upon showing interest in participating, mothers were mailed a consent form and a packet of questionnaires, which they were asked to complete and bring to their laboratory visits.

Upon arriving to the laboratory, a primary female experimenter informed the mother that her child would participate in several activities (“episodes”). Episodes included a Risk Room in which the toddler engaged in both free-play and guided interaction with activities designed to elicit individual differences in risk-avoidance (tunnel, trampoline, balance beam, large black box with a face and open mouth, and a gorilla mask on a pedestal) and five standard episodes (e.g., Buss & Goldsmith, 2000) involving novel stimuli designed to elicit distress to novelty (conversation with a male stranger, observation of an unpredictable remote-controlled robot, interaction with a clown, interactive puppet-show, and approach by a large remote-controlled spider). Each episode lasted approximately 3 minutes. Mothers always remained with their children. For conversation with a male stranger and remote-controlled robot (“mother-uninvolved episodes”), mothers were instructed to remain as neutral as possible. For the clown, puppet show, and spider activities (“mother-involved episodes”), mothers were instructed to interact with their toddlers and the activity “however you typically would or however seems natural to you.” The experimenter explained each activity to the mother, including instructions about her involvement, and interviewed her about her predictions for her toddler’s emotional and behavioral reactions to the five novelty episodes from scripted questions (Table 1) at the beginning of the visit. The toddler and mother then participated in these episodes, which proceeded according to standardized scripts in a set order.

Table 1.

Maternal Predictions and Corresponding Toddler Behaviors

| Prediction (“Will your child…”) | Behavior |

|---|---|

| Conversation with a Male Stranger | |

| Smile at or greet the stranger? | Intensity of greeting |

| Approach the stranger? | Boldness |

| Cry or fuss? | Distress vocalizations |

| Want to be held by you? | Attempt to be held |

| Want to stay close to you? | Proximity to mother |

| Be upset during stranger interaction? | Distress after stranger’s questions |

| Answer the stranger’s questions? | Proportion of responses to questions |

| Be wary/fearful of the stranger? | Shyness |

| Robot | |

| Approach the robot? | Boldness |

| Want to stay close to you? | Proximity to mother |

| Want to be held by you? | Attempt to be held |

| Play with the robot? | Intensity of play |

| Be wary/fearful of the robot? | Shyness |

| Cry or fuss? | Distress vocalizations |

| Puppet Show | |

| Approach the puppets? | Boldness |

| Want to stay close to you? | Proximity to mother |

| Want to be held by you? | Attempt to be held |

| Play all the games with the puppets? | Number of games played |

| Talk with the puppets? | Number of vocalizations directed at puppets |

| Be wary/fearful of the puppets? | Shyness |

| Be willing to help the puppets? | Willingness to help puppets |

| Cry or fuss? | Distress vocalizations |

| Clown | |

| Approach the clown? | Boldness |

| Want to stay close to you? | Proximity to mother |

| Want to be held by you? | Attempt to be held |

| Play all the games with the clown? | Number of games played |

| Be wary/fearful of the clown? | Shyness |

| Talk to the clown? | Number of vocalizations directed at the clown |

| Cry or fuss? | Distress vocalizations |

| Spider | |

| Approach the spider? | Boldness |

| Want to stay close to you? | Proximity to mother |

| Want to be held by you? | Attempt to be held |

| Play with the spider? | Intensity of play |

| Be wary/fearful of the spider? | Shyness |

| Cry or fuss? | Distress vocalizations |

The visit was videotaped for later scoring of observational data. Coders, who were blind to study hypotheses, were required to achieve adequate inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] or κ = .80) with a master coder (the first author) before coding independently. Reliability checks on 20% of cases occurred throughout coding to prevent drift.

Approximately one year after the laboratory visit, mothers were contacted through the mail about participating in a follow-up assessment. Interested mothers were mailed a packet including a consent form, questionnaires, and a stamped, addressed envelope in which to return them.

Measures

Fearful temperament

Fearful temperament was a composite of behaviors observed in Risk Room. Behaviors included: latency to touch first toy, attempt to be held by mother, approach towards parent, tentativeness of play, and compliance to the experimenter. Latency to touch the first toy was measured as the number of seconds between the start of the episode (when the primary experimenter left the room) and the child’s first intentional contact with an activity. Attempt to be held, approach towards parent, and tentativeness of play were scored on a 0 (no display) to 3 (extreme display) scale in each 10-second epoch of the episode; a final score was computed as the average of scores across epochs. Compliance to experimenter was the count from 0 to 5 of the number of objects with which the child interacted as instructed by the experimenter. Reliability was found to be acceptable for all five behaviors (ICCs = .78 to .98).

Toddler global distress in mother-involved episodes

Trained coders also scored toddlers’ overall distress in Spider, Puppet Show, and Clown to determine the “threat” level of the episode. Global distress was scored on a 5-point scale (1 = no distress or fleeting display, 5 = display of distress that is extremely intense, lasts the entire episode, or causes the episode to be ended early). Inter-rater reliability was found to be adequate (ICC = .84).

Protective behavior

Consistent with previous studies of maternal protective behavior (Kiel & Buss, 2010; Rubin et al., 2002), the overall protective behavior variable comprised both comfort and protection, scored on a 0–3 scale each 10-second epoch of the mother-involved episodes (clown, puppet show, spider). Comforting behavior included physically affectionate behaviors: 0 = No physical comforting shown, 3 = Mother hugs or embraces child. Protective behaviors included acts of shielding the child from the stimulus: 0 = No protective behavior shown, 3 = High intensity or long behavior (e.g., turns child completely away from stimulus and holds child in position or stops episode). Note that although these behaviors, although controlling, are differentiated from “intrusive” behaviors, another subset of controlling behaviors, as in Kiel and Buss (2010): protective behaviors prevent the child from interacting with the stimulus, whereas intrusive behaviors push the child towards the stimulus. Reliability was computed on an epoch-by-epoch basis and found to be adequate for comforting (ICC = .92) and protective behavior (ICC = .91) across episodes.

Because it was more intrusive and more universally elicits intense fear reactions, the spider episode was considered to be the “high-threat” context. The clown and puppet show episodes required less proximity to the stimulus, are found to be pleasurable by many children, and less universally elicit high fear, so they are referred to as “low-threat” contexts (citation omitted for review; see Results for additional evidence of this designation). It should be noted that low-threat does not equate to non-threat, as these episodes still involve an element of novelty and encourage approach. A principal components analysis of protective and comforting behavior in the three episodes (6 variables) validated the separation of behaviors by context. Two components accounted for 64% of the variance: the first component comprised comforting and protective behaviors in the high-threat spider episode (loadings = .86, .87, respectively), and the second component contained comforting and protective behaviors in the low-threat clown and puppet show episodes (loadings = .70 to .73). No variable loaded on the opposite factor at > .30. Therefore, composites were formed within context. Comforting and protective behaviors displayed in the Spider episode were highly related (r[115] = .66, p < .01) and their mean is referred to as protective behavior in the high-threat context. Comforting behavior averaged across Clown and Puppet Show was related to protective behavior averaged across the two episodes (r[115] = .56, p < .001), so their mean comprised protective behavior in the low-threat context.

Maternal accuracy

Maternal accuracy was assessed as the statistical association between mothers’ predictions for their toddlers’ distress behaviors and toddlers’ observed distress behaviors in the five novelty episodes. Mothers made predictions of “Definitely yes,” “Probably yes,” “Probably no,” and “Definitely no” in response to interview questions, which were scored 0–3 according to the direction of distress. For example, for questions about fear or withdrawal (e.g., “Will your child become upset when the stranger talks to your child”), a response of “Definitely yes” would be scored as 3, “Probably yes” would be scored as 2, etc. For questions about pleasure and approach (e.g., “Will your child approach the puppets?”), responses of “Definitely yes” would be scored as 0, “Probably yes” would be scored as 1, etc. The 35 predictions were found to be internally consistent (α = .90).

Toddlers’ behaviors corresponding to these predictions were scored by trained coders, standardized, and given z-scores. General descriptions of behavior scoring follow, and Table 1 lists behaviors scored in each episode and with corresponding maternal predictions. For example, the maternal prediction of “Will your child approach the puppets?” in Puppet Show corresponded to the scoring of “Boldness” in that episode. For behaviors scored in more than one episode, the range of reliability estimates is provided.

A few behaviors were scored for the maximum intensity displayed in each 10-second epoch or each second of the episode. Reliability for these behaviors was computed on an epoch-by-epoch or second-by-second basis, respectively. “Distress vocalizations” (ICCs = .68 – .97) was scored on a 4-point scale (0 = no distress, 1 = whimpering or fussing, 2 = definite non-muted cry, 3 = full intensity cry/scream). “Attempt to be held” (ICCs = .78 – .98) was also scored on a 4-point scale (0 = no attempt, 1 = some contact seeking or no resistance to mother picking child up, 2 = gestural or verbal cue to mother to be picked up, 3 = multiple attempts to be picked up or physically climbs or tries to climb onto mother’s lap). Distress vocalizations and attempt to be held were each scored within 10-second epochs, and an average of the scores across the episode provided a final score. “Proximity to mother” (κs = .71 – .99) was scored each second of the episode as 0 = further than 2 feet from mother, 1 = within 2 feet of mother, 2 = touching mother, and an average of scores across the episode yielded the final score.

Other behaviors were scored once for the entire episode or once for each designated response time within the episode. “Boldness” (i.e., approaching, playing comfortably; ICCs = .83 – .96) and “Shyness” (withdrawal, freezing, refusal to interact; ICCs = .69 – .88) were scored on a 1 (none) to 5 (many long or intense displays) for the entire episode. “Distress after Stranger’s questions” (ICC = .95) was scored on the same scale following each of the stranger’s questions, and the average yielded a final score. In Conversation with a Male Stranger, “Intensity of greeting” (ICC = .93) was scored on a 0 (no greeting) to 3 (enthusiastic greeting) for the first 10 seconds following the stranger’s entrance, and “Proportion of responses” (ICC = .88) was scored as the proportion of the stranger’s questions to which the child offered a verbal or non-verbal (e.g., head-nod) response. In Robot and Spider, “Intensity of play” (ICCs = .85, .70) was scored on a 0 (none) to 3 (touches toy comfortably for 2 sec. or longer) scale. In Clown and Puppet Show, “Number of games played” (κ = .98, .86) was a count (0–3) of the number of activities in which the child engaged, and “Number of vocalizations to the clown/puppets” was a count of the number of vocalizations directed at the respective stimulus. “Willingness to help puppets” (ICC = .78) was scored on a 0 (no attempt to recover ball) to 3 (hands ball to puppets) scale to capture the maximum intensity of the child’s help during the catch game. Because toddler behaviors were scored on different scales, they were standardized and assigned Z-scores.

The multiple observations within the five episodes for mothers and toddlers were analyzed in a multilevel model to estimate the strength with which maternal predictions actually predicted toddler behavior composites. An explanation of this statistical procedure follows.

Maternal goals

Mothers completed the Child Behavior Vignettes (CBV; Hastings & Coplan, 1999; Hastings & Grusec, 1998; Hastings & Rubin, 1999), which asks mothers to read hypothetical vignettes and imagine their children displaying various behaviors. The current study focused on the Shyness vignette, which depicts the mother seeing her child watching other children play, looking nervous and refraining from joining. The current study focused on items asking mothers to rate the importance of parent-centered goals (2 items, α = .91: “I would want my child to behave properly, right away,” and, “I would want my child to understand that I expect him/her to behave properly”) which were scored on a 1 (not at all important) to 5 (very important) scale. Their mean yielded the final measures of parent-centered goals. Previous studies using this scale found it to have moderate internal consistency and to relate positively to other types of parenting indicative of wanting a “quick fix” (e.g., emotion-dismissing parenting, power assertion, and authoritarianism), and to negatively relate to parenting that would aid in children’s development of mastery over their emotional experiences (e.g., reasoning and responsiveness) (Coplan et al., 2002; Hastings & Grusec, 1998; Hastings & Rubin, 1999; Lagacé-Séguin & Coplan, 2005)

Age 3 shyness/inhibition

Mothers completed the Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment – Revised (ITSEA; Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2000), a 193-item questionnaire that asks parents to rate their children’s feelings and behaviors from the last month on a 0–2 scale (0 = not true or rarely true; 1 = somewhat or sometimes true; 2 = very true or often true). The current study used the Inhibition to Novelty scale (5 items, α = .75; e.g., “Is quiet or less active in new situations”). The ITSEA is a reliable and valid measure of early problem behaviors, relating to independent evaluators’ ratings of behavior problems (Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003).

Mothers also completed the Child Social Preference Scale (CSPS; Coplan, Prakash, O’Neil, & Armer, 2004), a parent-report measure of children’s shyness and social disinterest. Mothers indicated on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot) scale how typical particular behaviors were for their children. The current study uses the Shyness scale (7 items, α = .89; e.g., “My child ‘hovers’ near where other children are playing, without joining in”). The CSPS has previously been shown to be reliable and valid, relating to maternal report of temperament and observed peer interactions (Coplan et al., 2004).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Construction of the maternal accuracy variable

Maternal accuracy was examined as the statistical relation between maternal predictions and toddler behaviors in a multilevel model before moving to the primary multiple regression analyses. Data were structured within a three-level model to account for the nesting and non-independence of toddler behaviors and maternal predictions (Level 1) within episodes (Level 2) and within mother-toddler dyads (Level 3). In this model, each of the 35 individual predictions (the independent variable) predicted corresponding toddler behaviors (the dependent variable) for each of the 117 dyads (4095 total observations). The model revealed better fit with random components for the maternal prediction variable at both Levels 2 and 3 (χ2[2] = 29.0, p < .01), in addition to the fixed components, suggesting the existence of individual differences among mothers in the relation between predictions and toddler behaviors (i.e., maternal accuracy). Across the sample, maternal predictions significantly related to toddler behaviors (π = 0.08, t[3971] = 4.66, p < .001).

Consistent with previously published studies (citations omitted for review), this multilevel model was also used to calculate accuracy for each mother. Each dyad could be thought of as having their own regression equation with a slope representing the statistical relation between a mother’s predictions and her toddlers’ behaviors (i.e., the higher the value of the slope, the more accurate mothers were in their predictions). Slopes were estimated as Empirical Bayesian estimates, which use both the data from the dyad and the pattern of information across the sample, and comprise the variable of maternal accuracy used in subsequent analyses.

Episode threat

Paired samples t-tests using a Bonferroni correction (α = .02) compared toddlers’ global distress across the three episodes. Global distress was higher in the Spider episode (M = 2.48, SD = 1.28) than in both the Clown (M = 1.47, SD = 0.85; t[116] = 8.13, p < .001) and Puppet Show (M = 1.31, SD = 0.56; t[116] = 10.21, p < .001) episodes. Clown and Puppet Show evoked a similar level of distress (t[116] = 2.02, ns). Twenty-eight children had a high score (4 or 5) on global distress in the Spider episode, compared to six in the Clown episode and zero in the Puppet Show episode. These results, along with previous studies (citation omitted for review), support the designation of Spider as a “high-threat” context and Clown and Puppet Show as “low-threat” contexts.

Missing data

Sixteen mothers did not complete the CBV before the laboratory visit and did not return it in a stamped, addressed envelope provided at the end of the visit, even after multiple reminder calls. These mothers did not differ from mothers who completed the CBV in terms of toddler fearful temperament, protective behaviors, or maternal accuracy (ps > .10). The 41 participants who did not complete the follow-up packet did not differ from those who did in terms of those behaviors or maternal goals (ps > .10). A non-significant Little’s MCAR test (χ2[9] = 7.02, p = .64) suggested that missing data were not systematically related to patterns of other variables in the data set.

For a moderate amount of missing observations, multiple imputation is the suggested approach because listwise deletion results in substantially reduced power and biased parameter estimates (Jeličić, Phelps, & Lerner, 2009; Widaman, 2006). Even in the case of a pattern consistent with MCAR data, it is possible that not all variables related to the outcome (outside the scope of the current study) could be included in the analyses. Multiple imputation minimizes these problems because it retains the characteristics of entire data set and is therefore one of the recommended “modern” approaches for handling missing data in longitudinal research (Jeličić et al., 2009; Widaman, 2006). Therefore, missing values of goals and shy/inhibited behavior were imputed across 10 imputations. The algorithm used fearful temperament, protective behaviors, and existing values of goals, age 3 inhibition to novelty, and age 3 shyness for imputation. All remaining analyses use this imputed data (N = 117).

Data Reduction and Descriptive Statistics

Age 3 inhibition to novelty and shyness were related before (r[72] = .44, p < .001) and after (r[115] = .45, p < .001) imputation. A mean of these (standardized) variables yielded the final composite of age 3 shy/inhibited behavior.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate relations among variables are presented in Table 2. Noticeably, protective behavior was lower in the low-threat episodes than the high-threat episode (M = −0.32, t[116] = −8.29, p < .001, 95% CI [−0.39, −0.24]). Thus, in general, mothers adjusted their behavior according to the nature of the situation. Protective behavior appeared to be a more universal response in the high-threat context, but half of mothers displayed some protection in the low-threat episodes. Protective behaviors in high-threat and low-threat contexts were not related. Protective behavior in the low threat context demonstrated some skew, so it was subjected to a square root transformation. After this, it, and all other variables, reasonably adhered to a normal distribution (skew < 2.00). SES related to protective behavior in low-threat contexts but not to predictor variables, so it will be included as a covariate in analyses with this outcome.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Relations

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SES | 49.74 (11.93) | 17.00 – 66.00 | −.04 | .12 | .30** | .10 | .04 | .02 |

| 2. Fearful temperament | 0.00 (0.78) | −1.02 – 2.76 | -- | .54*** | .30** | .16† | .09 | .26* |

| 3. Accuracy | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.00 – 0.18 | -- | .55*** | .40*** | −.03 | .41*** | |

| 4. Protection in low threat | 0.05 (0.11) | 0.00 – 0.58 | -- | .12 | −.06 | .31** | ||

| 5. Protection in high threat | 0.37 (0.40) | 0.00 – 2.30 | -- | .00 | −.05 | |||

| 6. Parent-centered goals | 3.20 (1.18) | 1.00 – 5.00 | -- | −.02 | ||||

| 7. Age 3 shy/inhibited behavior | 0.00 (0.85) | −1.82 – 2.18 | -- |

Note. All statistics were computed after imputation of missing values (all df = 115). For protection in low threat contexts, descriptive statistics are presented for the raw variable and correlations were computed after square-root transformation. Fearful temperament and age 3 shy/inhibited behavior were composites of Z-scores.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

The association between fearful temperament and maternal accuracy might support an interpretation that the behavior of more temperamentally fearful toddlers is easier to predict, so accuracy merely reflects toddler temperament. However, these variables share only 30% of their variance, suggesting these are fairly unique constructs.

Hypothesis 1: Relation of Protective Behavior to Age 2 Fearful Temperament and Age 3 Shy/Inhibited Behavior is Context-Specific

As we predicted, protective behavior in low-threat contexts, but not protective behavior in the high-threat context, related to age 2 fearful temperament (Hypothesis 1a) and age 3 shy/inhibited behavior (Hypothesis 1b) (Table 2).

Before proceeding with further analyses, we wanted to provide evidence that protective behavior in low-threat contexts is worth concern. In line with Hypothesis 1c, we examined whether protective behavior in low-threat contexts predicted age 3 shy/inhibited behavior controlling for age 2 fearful temperament, and, further, whether it acted as a mediator of these variables (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). We included SES as a covariate in all steps. In a regression equation (R2 = .18, 95% CI [.06, .30], F[2,114] = 12.51, p < .001), fearful temperament related to protective behavior in low-threat contexts (β = .31, t[116] = 3.60, p < .001). Next, in the first step of a hierarchical regression model (R2 = .07, 95% CI [−.02, .16], F[2, 114] = 4.15, p < .05), age 2 fearful temperament predicted shy/inhibited behavior (β = .26, t[116] = 2.87, p < .01). Adding low-threat protective behavior to the model in the next step resulted in a significant change in the model (ΔR2 = .06, p < .01; R2 = .13, 95% CI[.02, .24], F[3, 113] = 5.50, p < .01). Protective behavior in low-threat contexts predicted age 3 shy/inhibited behavior above and beyond fearful temperament (β = .27, t[116] = 2.78, p < .01), and the individual effect of fearful temperament dropped to marginal significance (β = .18, t[116] = 1.91, p < .10). The indirect effect of the relation between age 2 fearful temperament and age 3 shy/inhibited behavior through protective behavior in low-threat contexts was found to be significant (indirect effect = .09, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [.02, .20]) using bias-corrected bootstrapping techniques (Preacher & Hayes, 2008), supporting Hypothesis 1c.

Thus, protective behavior displayed in low-threat, but not high-threat, contexts related to both age 2 fearful temperament and age 3 shy/inhibited behavior controlling for age 2 fearful temperament. It also mediated their relation. Given this importance of protective behavior in low-threat contexts, we next sought to examine the conditions under which fearful temperament relates to such behavior.

Hypothesis 2: Three-Way Interactions in Relation to Context-Specific Protective Behaviors

We next aimed to better understand how maternal accuracy and goals for shy behavior affect the strength of the relation between fearful temperament and protective behaviors in the two contexts. To determine support for Hypothesis 2, regression analyses for moderation were performed separately for high-threat and low-threat protective behaviors. Models were examined in a top-down fashion, such that the three-way interaction among fearful temperament, maternal accuracy, and maternal goals; all lower-order two-way interactions; and the main effects were entered into the model simultaneously. A significant interaction was probed by examining (1) simple slopes of the relation between fearful temperament and protective behavior at recentered values (−1 SD, mean, +1 SD) of maternal accuracy and maternal goals and (2) the region of significance of the interaction. Fearful temperament, maternal accuracy, and maternal goals were centered at their means prior to analyses, and SES was included as a covariate for the model examining protective behavior in low-threat contexts.

Protective behavior in low-threat contexts

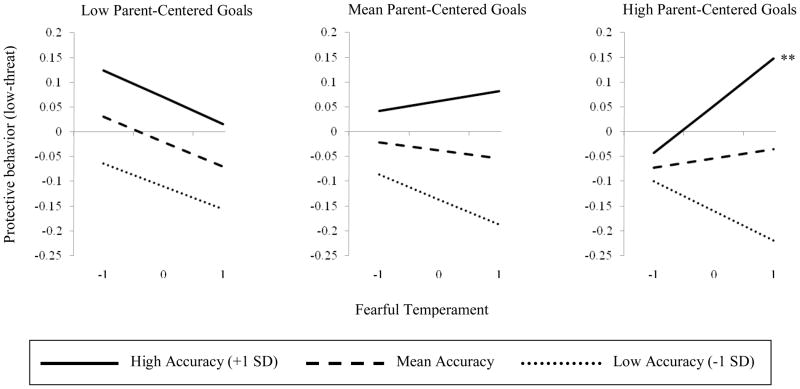

The initial model, (R2 = .44, 95% CI [.32, .56], F[8,108] = 10.51, p < .001), yielded a significant three-way interaction among fearful temperament, maternal accuracy, and parent-centered goals (β = 0.20, t[116] = 2.19, p < .05). Probing this interaction by recentering parent-centered goals revealed that the fearful temperament X maternal accuracy simple interaction did not relate to protective behavior at −1 SD parent-centered goals (β = −0.02, t[116] = −0.16, ns), but it displayed a significant association at mean (β = 0.18, t[116] = 2.00, p < .05) and +1 SD of parent-centered goals (β = 0.38, t[116] = 2.86, p < .01). In support of Hypothesis 2, as parent-centered goals increased, the fearful temperament X maternal accuracy simple interaction increased in strength. Simple slopes of fearful temperament at varying levels of maternal accuracy are presented at +1 SD of parent-centered goals in text, and all simple slopes can be seen in Figure 2. At +1 SD of parent-centered goals, the relation between fearful temperament and protective behavior was negative but non-significant at low accuracy (β = −0.25, t[116] = −1.29, ns), non-significant at mean accuracy (β = 0.08, t[116] = 0.65, ns), and significant and positive at high accuracy (β = 0.41, t[116] = 2.94, p < .01). The region of significance of this interaction revealed that, at +1 SD of maternal goals for shyness, the relation between fearful temperament and protective behavior in low-threat contexts shifted from non-significance to significance at accuracy = 0.103 (0.46 SD above the mean). Thus, in support of Hypothesis 2b, toddler fearful temperament most strongly related to protective behavior in low-threat contexts when mothers displayed both high accuracy and high parent-centered goals.

Figure 2.

Maternal accuracy moderated the relation between fearful temperament and protective behavior in low-threat contexts at high but not low or mean parent-centered goals. SES was included as a covariate. **p < .01.

Protective behavior in the high-threat context

In the initial model, (R2 = .18, 95% CI [.06, .30], F[7,109] = 3.49, p < .01), the fearful temperament X maternal accuracy X maternal goals interaction was not significant (β = −0.03, t[116] = −0.30, ns). After dropping this interaction and rerunning the model (R2 = .18, 95% CI [.06, .30], F[6,110] = 4.09, p < .01), none of the two-way interactions reached significance (all ts < 1.20, all ps > .20). After dropping these interactions and running a main effects model (R2 = .16, 95% CI [.04, .28], F[3,113] = 7.40, p < .001), only maternal accuracy reached significance (β = 0.43, t[116] = 3.97, p < .001). In support of Hypothesis 2, fearful temperament was not related to protective behavior in a high-threat context at any level of maternal accuracy or parent-centered goals for shyness. Although maternal accuracy related to protective behavior in this context, this did not depend on toddlers’ temperamental fearfulness.

Discussion

The current literature consistently cites a need for a more comprehensive understanding of the interactions between fearful children and their parents (e.g., Coplan et al., 2008; Rubin et al., 2009). To this end, the current study clarified the conditions under which toddler fearful temperament relates to maternal protective behavior. We differentiated protective behavior displayed in low- from high-threat contexts and examined maternal accuracy and goals as moderators.

Certainly, when mothers act protectively, they may be engaging in what they perceive as sensitive behavior. However, protective behavior in low-threat contexts may be more appropriately considered “overprotective” than in other contexts because the intensity and proximity of threat, determined by toddlers’ typical reactions, do not warrant parental intervention and could be opportunities for children to explore and gain mastery over the environment (Rubin et al., 2001). Consistent with previous studies demonstrating that low-threat contexts may identify children at risk for anxiety (Buss, 2011; Buss et al., 2004), they may similarly highlight maternal behavior linked to the development of shy/inhibited behavior. In fact, expanding on previous work (Kiel & Buss, 2010), we found protective behavior in low-threat contexts to mediate the relation between fearful temperament and later shyness/inhibition. Future studies should aim to replicate these relations with shyness/inhibition and risk for anxiety assessed through additional methods beyond maternal report.

When temperamentally fearful children successfully solicit protective behavior in transactional relations with their parents, developmental trajectories towards risk may be more likely to occur (Dadds & Roth, 2001). Previous research identified high maternal accuracy as a necessary condition for the relation between fearful temperament and maternal protective behavior (Kiel & Buss, 2010). The current study added further specificity, finding that maternal accuracy moderated the relation between fearful temperament and protective behavior in low-threat contexts when mothers endorsed higher parent-centered goals. The significance of this three-way interaction conforms to previous theory that when mothers anticipate their anxious children’s wariness and desire a “quick fix” for the situation (putatively, relieving the child’s distress so they behave “properly” for a low-threat situation), they are likely to enact protective, comforting behavior (Rubin et al., 2009).

The current study also contributed to the extant literature by demonstrating the context-specificity of this interaction. Maternal accuracy and goals did not moderate the relation between fearful temperament and protective behavior in a high-threat context. In this situation, mothers may rely less on their toddlers’ temperamental dispositions and their parenting goals, and more on the more universally fear-eliciting nature of this episode in determining their parenting. Although higher accuracy in predicting their toddlers’ fear related to mothers engaging in more protective behavior, this did not depend on toddlers’ fearful temperament, suggesting that protective reactions in this context had little to do with potential transactional relations between toddler fearfulness and maternal protective behavior.

Like the current study, the extant parenting literature has focused almost exclusively on mothers. Although unable to be addressed here, understanding these relations in the context of paternal parenting is also important. Previous research suggests that mothers and fathers differ in their perceptions of children’s emotions and responses to children’s anxious behavior (Bögels & Phares, 2008; Cassano, Perry-Parrish, & Zeman, 2007). Fathers’ protective parenting predicts children’s anxiety-spectrum outcomes uniquely from mothers’ protectiveness (Hastings, Sullivan, McShane, Coplan, Utendale, & Vyncke, 2008). Mother-father differences in accuracy of anticipating fear and the effect of accuracy and parenting goals on parenting of temperamentally remains unknown. The literature would benefit from future work examining differences between mother-child and father-child relations as involved in the outcomes of children’s fearful temperament.

The current study was unable to answer questions related to potentially important cultural influences on relations between toddler temperament and maternal characteristics and behavior. Maternal attitudes and behavior in response to children’s fearfulness, and maternal cognitions about parenting in general, differ between western and eastern cultures and across SES (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006; Chen et al., 1998, Rubin et al., 2006). Thus, culture, defined broadly, may impact the relations observed in the current study, and the precise nature of this influence is a needed area of future research.

A few measurement considerations are warranted. First, given that mothers were predicting the likelihood of their toddlers’ fearful distress reactions (probably versus definitely present or absent), we were unable to examine mothers’ expectations for the intensity of their toddlers’ reactions. Given that toddlers’ behaviors were often scored as intensity ratings, asking mothers to predict intensity may improve the measure of maternal accuracy. Future work could compare mothers’ predictions of intensity versus predictions of likelihood.

Questions remain about how maternal accuracy affects the relation between fearful temperament and maternal behavior. For example, it would be informative to assess whether mothers have different goals for their children’s behavior in low- versus high-threat contexts. It will also be important to understand other characteristics of mothers who demonstrate high accuracy and then respond protectively to more comprehensively conceptualize processes occurring between fearful children and their parents.

Finally, understanding how these results may impact parenting interventions is an important area for future research. Certainly, we would not suggest that mothers become less accurate in anticipating their children’s fear. Rather, the relation between accuracy and protective behavior could be targeted. Maternal accuracy could be used to anticipate opportunities to teach coping skills. Or, other maternal characteristics (i.e., goals for and broader beliefs about shyness and inhibition) might be targeted for change because they impact the likelihood of responding protectively when mothers are attuned to their children’s distress. Perhaps supporting mothers to formulate alternative goals for situations that evoke their children’s shyness would help them to respond to their children’s bids for support with behaviors that promote adaptive development (Rapee, Kennedy, Ingram, Edwards, & Sweeney, 2010).

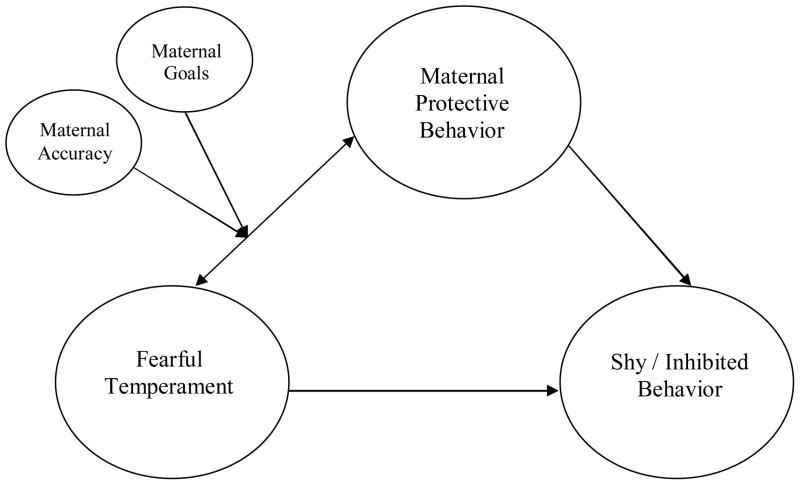

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of relations among variables.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth J. Kiel, Miami University

Kristin A. Buss, The Pennsylvania State University

References

- Arcus D. Inhibited and uninhibited children. In: Wachs TD, Kohnstamm GA, editors. Temperament in context. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Sanson AV, Hemphill SA. Parent influences on early childhood internalizing difficulties. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:542–559. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jaffee SR. The multiple determinants of parenting. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006. pp. 38–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S, Phares V. Fathers’ roles in the etiology, prevention, and treatment of child anxiety: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:539–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA. Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:804–819. doi: 10.1037/a0023227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH, Goldsmith HH. Context-specific freezing and associated physiological reactivity as a dysregulated fear response. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:583–594. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Psychology Department Technical Report. University of Wisconsin; Madison: 2000. Manual and normative data for the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery – Toddler Version. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Hill AL. Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation: Biological and environmental transactions in early development. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan M. Unpublished manual. University of Massachusetts Boston Department of Psychology; Boston, MA: Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2000. The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA) [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, Little TD. The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:495–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1025449031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, Zeman J. Influence of gender on parental socialization of children’s sadness regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:210–231. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Hastings PD, Rubin KH, Chen H, Cen G, Stewart SL. Child-rearing attitudes and behavioral inhibition in Chinese and Canadian toddlers: A cross-cultural study. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:677–686. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:3–21. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Arbeau KA, Armer M. Don’t fret, be supportive! Maternal characteristics linking child shyness to psychosocial and school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:359–371. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Hastings PD, Lagacé-Séguin DG, Moulton CE. Authoritative and authoritarian mothers’ parenting goals, attributions, and emotions across different childrearing contexts. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Prakash K, O’Neil K, Armer M. Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:244–258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne LW, Low CM, Miller AL, Seifer R, Dickstein S. Mothers’ empathic understanding of their toddlers: Associations with maternal depression and sensitivity. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:483–497. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Roth JH. Family processes in the development of anxiety problems. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 278–303. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SL, Rapee RM, Kennedy S. Prediction of anxiety symptoms in preschool aged children: Examination of maternal and paternal perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Coplan R. Conceptual and empirical links between children’s social spheres: Relating maternal beliefs and preschoolers’ behaviors with peers. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1999;86:43–59. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219998605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Grusec J. Parenting goals as organizers of responses to parent-child disagreement. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:465–479. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Rubin KH. Predicting mothers’ beliefs about preschool-aged children’s social behavior: Evidence for maternal attitudes moderating child effects. Child Development. 1999;70:722–741. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Sullivan C, McShane KE, Coplan RJ, Utendale WT, Vyncke JD. Parental socialization, vagal regulation, and preschoolers’ anxious difficulties: Direct mothers and moderated fathers. Child Development. 2008;79:45–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Unpublished manuscript. Department of Sociology, Yale University; New Haven, Connecticut: 1975. Four factor index of social status. [Google Scholar]

- Jeličić H, Phelps E, Lerner RM. Use of missing data methods in longitudinal studies: The persistence of bad practices in developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1195–1199. doi: 10.1037/a0015665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Maternal accuracy in predicting toddlers’ behaviors and associations with toddlers’ fearful temperament. Child Development. 2006;77:355–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Maternal accuracy and behavior in anticipating children’s responses to novelty: Relations to fearful temperament and implications for anxiety development. Social Development. 2010;19:304–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren-Karie N, Oppenheim D, Dolev S, Sher E, Etzion-Carasso A. Mothers’ insightfulness regarding their infants’ internal experience: Relations with maternal sensitivity and infant attachment. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:534–542. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Lagacé-Séguin DG, Coplan RJ. Maternal emotional styles and social adjustment: Assessment, correlates, outcomes, and goodness of fit in early childhood. Social Development. 2005;14:613–636. [Google Scholar]

- McShane KE, Hastings PD. The New Friends Vignettes: Measuring parental psychological control that confers risk for anxious adjustment in preschoolers. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:481–495. [Google Scholar]

- Mills RSL, Rubin KH. Parental beliefs about problematic social behaviors in early childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:138–151. [Google Scholar]

- Mount KS, Crockenberg SC, Bárrig Jó PS, Wagar J. Maternal and child correlates of anxiety in 2 ½-year-old children. Infant Behavior and Development. 2010;33:567–578. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Belsky J, Putman S, Crnic K. Infant emotionality, parenting, and 3-year inhibition: Exploring stability and lawful discontinuity in a male sample. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:218–227. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling methods for estimating and comparing indirect effects. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Kennedy SJ, Ingram M, Edwards SL, Sweeney L. Altering the trajectory of anxiety in at-risk young children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:1518–1525. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09111619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB. Social withdrawal and anxiety. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 407–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Hastings PD. Stability and social-behavioral consequences of toddlers’ inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Development. 2002;73:483–495. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Cheah CSL, Fox N. Emotion regulation, parenting and display of social reticence in preschoolers. Early Education and Development. 2001;12:97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hastings PD, Stewart SL, Henderson HA, Chen X. The consistency and concomitants of inhibition: Some of the children, all of the time. Child Development. 1997;68:467–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hemphill SA, Chen X, Hastings P, Sanson A, Coco AL, …Cui L. A cross-cultural study of behavioral inhibition in toddlers: East-West-North-South. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30:219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Mills RSL. Maternal beliefs about adaptive and maladaptive social behaviors in normal, aggressive, and withdrawn preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:419–435. doi: 10.1007/BF00917644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Nelson LJ, Hastings P, Asendorpf J. The transaction between parents’ perceptions of their children’s shyness and their parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1999;23:937–957. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71(3):42–64. [Google Scholar]