Abstract

Cucumber (Cucumis sativa) leaves infiltrated with Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae cells produced a mobile signal for systemic acquired resistance between 3 and 6 h after inoculation. The production of a mobile signal by inoculated leaves was followed by a transient increase in phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity in the petioles of inoculated leaves and in stems above inoculated leaves; with peaks in activity at 9 and 12 h, respectively, after inoculation. In contrast, PAL activity in inoculated leaves continued to rise slowly for at least 18 h. No increases in PAL activity were detected in healthy leaves of inoculated plants. Two benzoic acid derivatives, salicylic acid (SA) and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4HBA), began to accumulate in phloem fluids at about the time PAL activity began to increase, reaching maximum concentrations 15 h after inoculation. The accumulation of SA and 4HBA in phloem fluids was unaffected by the removal of all leaves 6 h after inoculation, and seedlings excised from roots prior to inoculation still accumulated high levels of SA and 4HBA. These results suggest that SA and 4HBA are synthesized de novo in stems and petioles in response to a mobile signal from the inoculated leaf.

Pathogen-induced necrosis on the leaves of many plant species, including cucumber (Cucumis sativa), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), and Arabidopsis, results in the production of a phloem mobile signal that triggers systemic resistance to subsequent pathogen attack (Kuc, 1982; Ryals et al., 1994). The development of SAR depends on the rate at which the inducing pathogen causes necrosis on the inoculated leaf. In cucumber, for example, an incompatible bacterial pathogen that causes a rapid HR induces systemic resistance within 2 d. A compatible pathogen that causes a slow, spreading necrosis requires 1 week or more to induce systemic resistance (Smith et al., 1991). Pathogen-induced necrosis on the inoculated leaf is accompanied by the accumulation of SA at the site of inoculation, in phloem fluids, and in healthy, uninoculated leaves (Malamy et al., 1990; Metraux et al., 1990; Enyedi et al., 1992; Summermatter et al., 1995). In tobacco and Arabidopsis, SA accumulation is in turn correlated with the expression of a set of genes called SAR genes, a subset of which encode the PR proteins (Ward et al., 1991; Uknes et al., 1992). In cucumber SAR is correlated with the systemic accumulation of extracellular peroxidase, β-1,3 glucanase, and chitinase (Hammerschmidt et al., 1982; Boller and Metraux, 1988; Ji and Kuc, 1995). Chitinase is a particularly useful marker for SAR in cucumber, since levels of the enzyme in control leaves are extremely low (Metraux et al., 1988).

The accumulation of SA is a requirement for SAR, as demonstrated by the inability of tobacco plants transformed with a bacterial gene encoding salicylate hydroxylase (nahG) to express SAR (Gaffney et al., 1993). However, SA does not appear to be the only mobile signal transported from the inoculated leaf, since NahG rootstocks, which do not accumulate SA, were still able to transmit a signal for SAR to wild-type scions (Vernooj et al., 1994). In addition, cucumber plants inoculated on one leaf with the HR-causing pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae accumulated high levels of SA in phloem exudates even when the inoculated leaf remained on the plant for only 6 h (Rasmussen et al., 1991). Maximal levels of SA were measured 18 h after inoculation in this system, so the majority of systemically accumulating SA was not synthesized by the inoculated leaf. In contrast to cucumber inoculated with HR-causing bacteria, 60 to 70% of systemically accumulating SA in tobacco mosaic virus-inoculated tobacco was found to originate from the inoculated leaf (Shulaev et al., 1995). In addition, removal of the inoculated tobacco leaf prior to SA accumulation prevented SAR. It remains to be determined whether the difference in the pattern of SA accumulation in the two systems results from a mechanistic difference in SAR between the two plant species or if it is due to the different rates of necrosis induced by incompatible bacteria (24 h) versus virus (3 d).

The nature of the mobile signal that originates in the inoculated leaf and leads to SA accumulation and SAR is unknown. The discovery that SAR occurs in Arabidopsis has resulted in a major effort to identify mutants in the SAR pathway (Uknes et al., 1992; Cameron et al., 1994; Cao et al., 1994; Dietrich et al., 1994). Although the advantages of Arabidopsis as a genetic tool are well documented, the cucumber system offers several advantages for the biochemical study of SAR. First and most importantly, the mobile signal for SAR is produced by cucumber leaves within 6 h after inoculation with incompatible bacteria, providing a narrow time frame within which to look for an active compound (Rasmussen et al., 1991; Smith et al., 1991). Second, the large leaves of cucumber are easy to saturate with inoculum and produce correspondingly large amounts of mobile signal. Third, cucumber stems exude relatively large amounts of phloem fluid when cut, allowing direct analysis of phloem-localized compounds. In the present work we have taken advantage of the rapid SAR response induced by an incompatible bacterial pathogen to study the biochemical changes that occur during the initiation of SAR in cucumber.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Culture and Inoculation

Cucumber (Cucumis sativa cv Wisconsin SMR 58) seedlings were grown in a growth chamber at 28°C with 14 h of light (270 μmol s−1 m−2) and 10 h of dark. Seedlings used for SA and 4HBA accumulation and PAL activity time-course experiments were left under continuous light during the experiment. Young plants, approximately 3 weeks old and with two fully expanded leaves, were inoculated on the second leaf with Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae as described previously (Rasmussen et al., 1991). Control plants were infiltrated with water. In some experiments, inoculated and uninoculated leaves were excised with a razor blade at various times after inoculation. Greenhouse-grown plants were used for the large-scale collection of phloem fluids.

Chitinase Assay

A sandwich ELISA assay utilizing monoclonal and polyclonal antisera generated against cucumber chitinase was used to estimate chitinase levels in leaf homogenates (Ciba-Geigy, Research Triangle Park, NC). Purified cucumber chitinase was used as a standard. The timing of primary signal production by inoculated leaves was determined by removing inoculated leaves at various times after inoculation as described previously (Rasmussen et al., 1991). Chitinase accumulation was measured in the third leaf after 5 d. Two 1-cm-diameter leaf discs were removed from the third leaves of four plants and stored in liquid N2 prior to assay. The limit of detection of chitinase in leaf extracts was approximately 150 ng/g fresh weight.

Collection of Phloem and Xylem Exudates

Time-Course Experiments

Petioles of inoculated leaves were excised 1.0 cm from the stem at various times after inoculation. For each sample, 12.5 μL of phloem fluid was collected from the excised petiole of each of four plants using a micropipettor. Collected phloem exudate was dispensed immediately into 500 μL of ice-cold methanol in a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube. Two samples, representing a total of eight plants, were collected for each treatment and analyzed separately by HPLC. Methanol extracts were vortexed and the precipitate was removed by centrifugation in a microfuge at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and the pellet re-extracted with an additional 200 μL of methanol. The methanol fractions were combined and the methanol was removed by evaporation at 40°C under a vacuum. The remaining aqueous sample was adjusted to a volume of 50 μL with distilled water and used for HPLC analysis. The efficiency of the extraction of SA and 4HBA was determined by adding known amounts of the compounds to control phloem fluid prior to extraction.

For the collection of xylem exudates, inoculated or control plants were cut with a razor blade at the stem base. Residual phloem exudate was blotted from the cut stump for 2 min, after which time the root pressure exudate continued to accumulate on the cut surface. Two-hundred microliters of root pressure exudate was collected from each of four plants and then added individually to Eppendorf tubes containing 1 mL of ice-cold methanol. Samples were processed as described for phloem samples except that the aqueous sample remaining after vacuum evaporation of methanol was lyophilized. Lyophilized samples representing root pressure exudate from four plants were combined in 50 μL of water prior to HPLC analysis.

Leaf and Root Excision Experiments

To determine the tissue source of systemically accumulating SA and 4HBA, leaves and cotyledons of seedlings that had been inoculated on one leaf were excised from plants 6 h after inoculation. All leaves, including the apical bud, were excised with a razor blade through the petiole at the base of the leaf. Phloem exudates were collected from stems immediately above petioles of inoculated leaves 20 h after inoculation (14 h after excision of leaves and cotyledons). In a separate experiment, seedlings were submerged in water and excised from roots at the stem base. Excised seedlings were floated on water for 2 d prior to inoculation. Although cucumber seedlings wilt severely upon excision from roots, approximately 70% of the seedlings survive the procedure if floated on water for at least 24 h. After 2 d seedlings were removed from water and placed with cut stem bases in large test tubes filled with distilled water. Leaves of excised seedlings were inoculated as described above and phloem exudate was collected from stems 20 h after inoculation.

HPLC Analysis

Fifty microliters of aqueous phloem fluid extract was injected onto a 5-μm C-18 column (Econosphere, Alltech, Deerfield, IL; 4.6 mm × 25 cm) fitted with a guard column. The column was equilibrated in water containing 0.075% trifluoroacetic acid with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Five minutes after injection of the sample, a linear gradient of 0 to 70% acetonitrile was applied to the column over 20 min. UV-absorbing compounds eluting from the column were monitored at 230 and 254 nm with a diode array detector (model 1040A, Hewlett-Packard).

The unidentified compound eluting from the gradient at 17.3 min was collected, dried, resuspended in 50 μL of distilled water, and purified isocratically on the same column using 15% acetonitrile in 0.075% trifluoroacetic acid and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The compound eluted at 6.8 min under these conditions. The isocratically eluted compound was dried and used for MS and proton NMR analysis. SA, which eluted at 21.8 min on the gradient system, was identified by its characteristic UV absorption spectrum, its co-elution with standard SA, and its visible fluorescence upon exposure to UV (302 nm) light. Quantitation was determined using a linear range of calibration standards consisting of 0 to 1.3 μg/50 μL of SA and 0 to 0.6 μg/50 μL of 4HBA. The limits of detection for SA and 4HBA were 24 ng/50 μL and 70 ng/50 μL, respectively.

NMR and MS Analysis

MS analysis was performed on a spectrometer (model VG7070E, Micromass, Manchester, UK) with an ionization potential of 30 eV and a resolution of 2000. Proton NMR spectra were taken in methanol-d4 at 300 MHz using a spectrometer (model QE-300, General Electric).

PAL Activity

PAL activity was determined spectrophotometrically as described by Edwards and Kessmann (1992) in inoculated leaves, petioles of inoculated leaves, stem segments above inoculated leaves, and leaves directly above inoculated leaves. For each sample, 1-cm-diameter leaf discs or 1-cm-long stem or petiole segments were collected from each of four plants and stored in liquid N2 prior to assay. Petiole segments were collected from the end of the petiole closest to the stem. Stem segments were collected 2 cm above the junctions of the petioles of inoculated leaves and stems. In one experiment, inoculated leaves were excised from petioles 6 h after inoculation. The excision was made at the base of the leaf so as to leave the entire petiole intact. Petiole segments were collected at 6 and 9 h after inoculation as described above. Tissue for assay was first ground to a fine powder in liquid N2 prior to the addition of extraction buffer. Homogenates were centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge and the resulting supernatant was used for PAL activity and protein determination. Protein levels were measured using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad) with BSA as standard (Bradford, 1976). Two samples were collected in each experiment and the experiments were repeated at least twice. se was calculated for measurements within each experiment.

RESULTS

Chitinase Assay

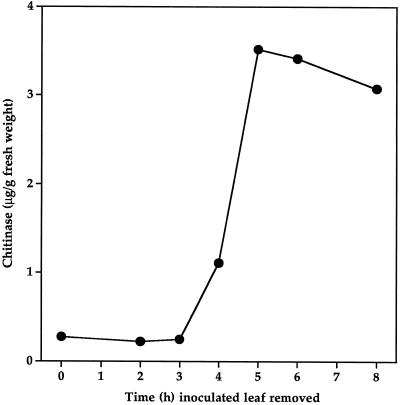

Signal production, as measured by systemic increases in chitinase after removal of inoculated leaves, began between 3 to 4 h after inoculation (Fig. 1). Plants inoculated at 50 sites on the first leaf were fully induced by 5 h. This correlates well with the previous observations of Smith et al. (1991) and Rasmussen et al. (1991) for the systemic increase of peroxidase activity.

Figure 1.

Signal production by inoculated leaves. Cucumber seedlings were infiltrated on the second leaf with P. syringae cells at 50 sites per leaf. The inoculated leaves were removed from plants at various times and systemic chitinase accumulation was measured in the third leaf 5 d after inoculation. se values were smaller than the size of the symbols.

HPLC, MS, and NMR Analysis

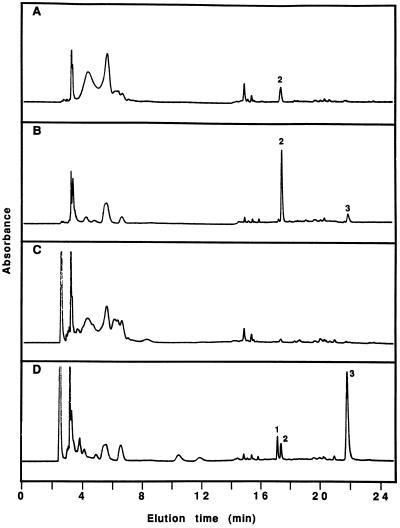

In addition to SA, a compound eluting at 17.3 min in the gradient system with an absorbance maximum at 260 nm increased significantly with time after inoculation (Fig. 2, A and B). Unlike SA, however, this compound was also present at low levels in control phloem fluids. The compound was purified from phloem fluids collected 18 h after inoculation and subjected to NMR and MS analyses. Observation of proton NMR doublets at 6.79 and 7.85 ppm (J = 8.5 Hz) indicated a disubstituted benzene ring with one electronegative (oxygen) moiety and one electron-donating (carbonyl) moiety in the para orientation. The compound was further identified as 4HBA by MS analysis.

Figure 2.

HPLC profile of phloem exudates. Phloem fluids were collected 18 h after infiltration of leaves with water (A and C) or with P. syringae (B and D). Eluting peaks were monitored for UV A254 (A and B) and A230 (C and D). The peaks were identified as SA glucoside (1), 4HBA (2), and SA (3).

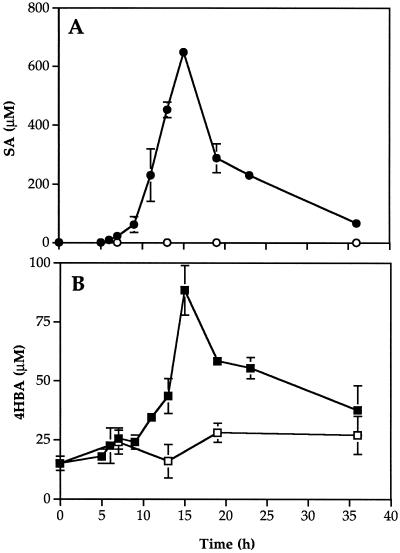

A standard sample of 4HBA and the compound isolated from phloem fluids shared identical HPLC retention times and UV spectra. SA was first detected in phloem fluids 6 h after inoculation (Fig. 3A). The levels of both SA and 4HBA increased with time until 15 h after inoculation, with a maximum rate of increase between 9 and 15 h (Fig. 3, A and B). The levels of both compounds had declined by 36 h, although free SA was still detected. In addition to 4HBA and SA, a new compound with A230 eluted from the column at 17.1 min in the gradient system (Fig. 2). This peak first appeared in phloem exudates collected 18 h after inoculation and increased with time as levels of free SA decreased (data not shown). The UV absorbance spectrum of the new compound was similar to that of SA and treatment of the isolated compound with β-glucosidase (Enyedi et al., 1992) released free SA (data not shown). Therefore, at least some of the free SA accumulating in phloem fluids was conjugated in the vascular system.

Figure 3.

Time course of SA and 4HBA accumulation in cucumber phloem exudates. The levels of SA (○, •) and 4HBA (□, ▪) in petiole phloem exudates from control (open symbols) or inoculated (closed symbols) plants were monitored for 36 h after infiltrating one leaf with water or with P. syringae cells. ses are indicated.

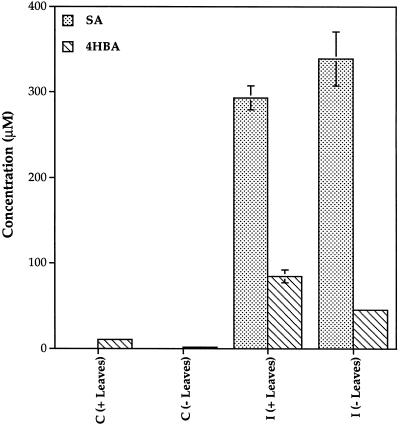

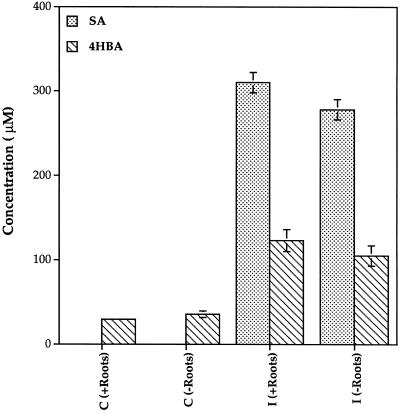

SA and 4HBA accumulating in phloem exudates did not originate from synthesis of the compounds in leaves or roots. Both SA and 4HBA accumulated to high levels in phloem fluid even when all of the leaves and both cotyledons were excised from plants 6 h after inoculation (Fig. 4). Seedlings excised from the roots also accumulated SA and 4HBA in phloem exudates to the same levels as seedlings that remained intact (Fig. 5). The efficiency of extraction of SA and 4HBA from phloem exudates was 87%, and the data are corrected for this value. Very few UV-absorbing peaks were observed in root pressure exudate samples and no differences were detected between control and inoculated plants at any time (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Accumulation of SA and 4HBA in phloem exudates after excision of leaves. Levels of SA and 4HBA in stem phloem exudate were determined 20 h after infiltration of one leaf on each plant with water (C) or P. syringae cells (I). Plants were either left intact (+Leaves), or had all leaves excised 6 h after inoculation (−Leaves). ses are indicated.

Figure 5.

Effect of excision of seedlings from roots on the accumulation of SA and 4HBA. Seedlings were either left intact (+Roots) or were excised from roots at the stem base and placed in water 2 d prior to inoculation (−Roots). Levels of SA and 4HBA in stem phloem exudate were determined 20 h after infiltration of one leaf on each plant with water (C) or with P. syringae (I). ses are indicated.

PAL Activity

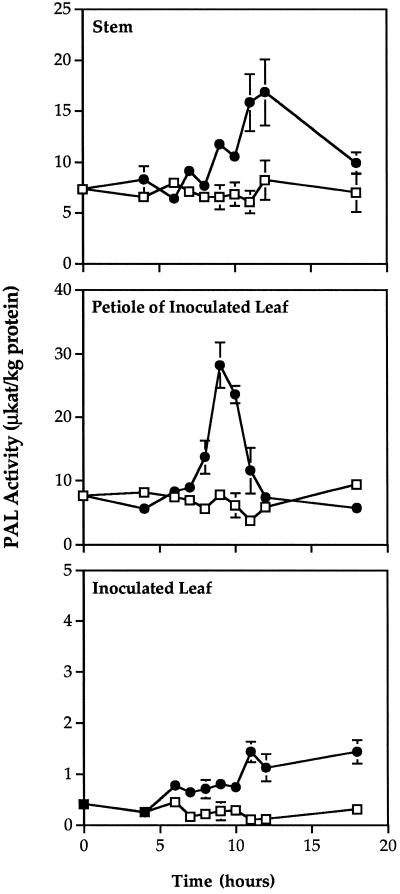

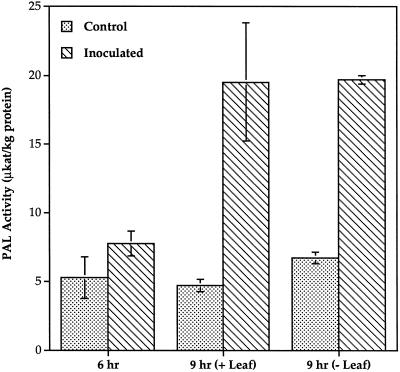

PAL activity began to increase by 6 h after inoculation in inoculated leaves and by 7 h after inoculation in the petioles of inoculated leaves and stems (Fig. 6). The increase in activity was transient in the petiole and stem, and activity returned to control levels by 12 and 18 h after inoculation, respectively. The peak in PAL activity occurred 9 h after inoculation in petioles and 12 h after inoculation in stems. In contrast, PAL activity in the inoculated leaf continued to increase for at least 18 h after inoculation. The increase in petiole PAL activity was unaffected by excision of the inoculated leaf 6 h after inoculation (Fig. 7). No differences in PAL activity were detected between control and inoculated plants in the leaf directly above the inoculated leaf (data not shown). In addition, no PAL activity was detected in phloem fluid exudates at any time after inoculation (data not shown). The constitutive activity of PAL in petioles and stems was at least 20-fold higher than that in leaves.

Figure 6.

Time course of PAL activity in different tissues during SAR. PAL activity was measured in leaves infiltrated with P. syringae (•) or water (□) (Inoculated Leaf); in 1-cm-long petiole segments of inoculated leaves (Petiole of Inoculated Leaf); or in 1-cm-long stem segments immediately above inoculated leaves (Stem) at various times after inoculation. ses are indicated.

Figure 7.

Effect of leaf excision on petiole PAL activity. Seedlings inoculated with P. syringae or water were either left intact (+Leaf) or the inoculated leaves were excised at the leaf base 6 h after inoculation (−Leaf). PAL activity was measured in 1-cm segments taken from the base of the petiole adjacent to the stem at 6 and 9 h after inoculation. ses are indicated.

DISCUSSION

In the classic interpretation of SAR, a mobile signal produced by the inoculated leaf travels through the vascular tissue to uninoculated leaves, where it induces PR gene expression and some level of SA synthesis. In this work we provide evidence that the vascular tissue itself may have an integral role in the perception and relay of the mobile signal. The accumulation of SA and 4HBA in phloem exudates of cucumber inoculated with P. syringae was preceded by a transient increase in PAL activity in stems and petioles of inoculated plants. The accumulation of both SA and 4HBA in phloem exudates peaked 15 h after inoculation and was unaffected by the removal of all leaves from plants 6 h after inoculation. Similarly, the increase in PAL activity in the petiole of the inoculated leaf was unaffected by the removal of the leaf 6 h after inoculation. Finally, seedlings excised from roots prior to inoculation still accumulated high levels of SA and 4HBA in phloem exudates.

Taken together, these data suggest that systemically accumulating SA and 4HBA were synthesized in stems and petioles, most likely in the vascular tissue, in response to a mobile signal from the inoculated leaf. Vascular synthesis of these compounds would explain the previous observation that cucumber leaves infiltrated with cells of P. syringae need to remain on the plant for only 6 h to induce SAR and systemic accumulation of peroxidase and SA (Smith et al., 1991; Rasmussen et al., 1991). In the present work we measured the accumulation of chitinase in uninfected leaves of induced cucumber as an additional marker for the production of a mobile signal for SAR. Our results are in agreement with previous studies, and demonstrate that export of a mobile signal from the inoculated leaf occurs rapidly between 3 and 5 h after inoculation. We first detected SA in phloem fluids of induced plants at 6 h after inoculation, which was slightly earlier than that reported by Rasmussen et al. (1991). This difference is most likely due to the increased sensitivity of HPLC analysis used in this work compared with the TLC assay used in the previous work.

Several reports suggest that PAL is a key regulatory enzyme in the synthesis of SA and establishment of SAR. Mauch-Mani and Slusarenko (1996) showed that in Arabidopsis, PAL activity was essential for accumulation of SA and expression of the HR. Recently, it was also reported that tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants epigenetically suppressed in PAL activity were unable to express SAR (Pallas et al., 1996). We observed that the constitutive activity of PAL in stems and petioles was approximately 20-fold higher than in leaves. Several studies of PAL-promoter activity in transgenic plants demonstrated activity in vascular tissues, where PAL is thought to provide the precursors for lignin deposition in the xylem (Bevan et al., 1989; Liang et al., 1989; Ohl et al., 1990). In addition, detailed analyses of the promoters of PAL2 from bean and PAL1 from Arabidopsis have begun to identify regions of the promoters specifically responsive to environmental and developmental signals (Liang et al., 1989; Ohl et al., 1990; Leyva et al., 1992). Although no PAL genes have been cloned from cucumber, their regulation is likely to be as complex as in other species.

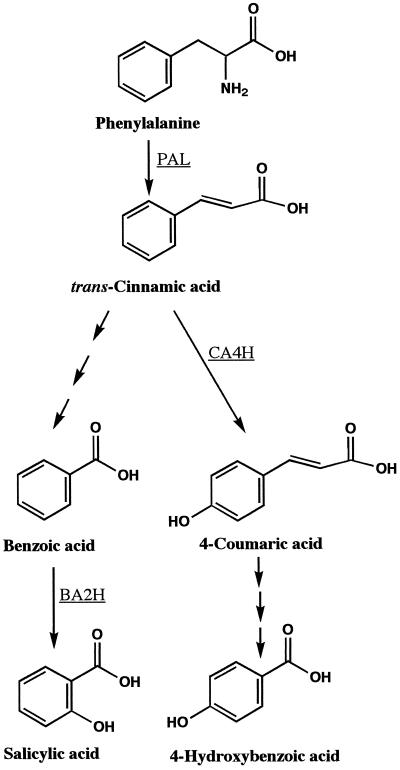

In addition to SA, a second phenylpropanoid compound, 4HBA, accumulated in phloem fluids of inoculated cucumber with the same kinetics as SA. Trace levels of 4HBA have previously been detected in phloem fluids from cucumber inoculated with Colletotrichum lagenarium (Metraux et al., 1990). Unlike SA, however, infiltration of 4HBA into leaves did not induce local resistance to C. lagenarium. Similarly, we found that infiltration of up to 5 mm 4HBA into leaves did not induce the accumulation of SA in phloem exudates or local accumulation of chitinase (data not shown). Meuwly et al. (1995) studied the incorporation of 14C-labeled Phe in inoculated and uninfected leaves of cucumber during SAR. They did not report enhanced synthesis of 4HBA in induced cucumber, but this may have been because of their addition of excess cold 4-coumaric acid, a likely precursor to 4HBA (Schnitzler et al., 1992; Fig. 8), to the reaction to drive incorporation into SA. Treatment of carrot cells with elicitor resulted in a transient increase in PAL activity, followed by an increase in 4HBA covalently bound to cell walls (Schnitzler and Seitz, 1989; Bach et al., 1993). Although 4HBA may enhance cell wall impermeability in response to pathogens, this has not been conclusively demonstrated. It is possible that enhanced levels of the compound in phloem exudate during SAR in cucumber is a nonspecific consequence of PAL stimulation (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed pathways of SA and 4HBA biosynthesis. Enzymatic steps for which the enzymes have been identified include PAL, CA4H (cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase), and BA2H (benzoic acid 2-hydroxylase).

The pattern of induced PAL activity in petioles and stems suggests that these tissues are responding to a mobile signal originating from the inoculated leaf. The increase in PAL activity may be due to increased expression of the gene for the enzyme and/or an increase in the rate of depletion of its product, trans-cinnamic acid. Cinnamic acid is a potent inhibitor of PAL activity, acting both to accelerate the depletion of the enzyme and to inhibit de novo enzyme production (Shields et al., 1982). One possibility is that the initial signal from the inoculated leaf leads to the activation of an enzyme or group of enzymes downstream from PAL that convert cinnamic acid to SA. For example, the enzyme benzoic acid 2-hydroxylase has been characterized in tobacco as a pathogen-induced monooxygenase that converts benzoic acid to SA (Leon et al., 1993; Fig. 8). Synthesis of SA in cucumber has also been suggested to proceed via a benzoic acid intermediate (Meuwly et al., 1995; Molders et al., 1996). The activities of benzoic acid 2-hydroxylase and the enzymes responsible for side-chain shortening of trans-cinnamic acid to benzoic acid have not been reported in cucumber. The results of the work presented here indicate that petioles of P. syringae-inoculated leaves and stems above inoculated leaves are likely tissues in which to find these enzyme activities in cucumber.

A variation of the classic model of signal transmission is suggested by the unexpected observation of Mauch-Mani and Slusarenko (1996) that the PAL promoter in Arabidopsis was suppressed by specific inhibition of PAL activity in pathogen-treated tissue. This indicates that a product of the phenylpropanoid pathway is involved in feedback stimulation of the PAL gene. If similar feedback regulation occurs in the cucumber/P. syringae system, PAL expression may be amplified in vascular tissue by a product of the phenylpropanoid pathway. For example, SA has been reported to potentiate the expression of PAL and other defense-related genes, allowing higher levels of expression in response to elicitors (Mur et al., 1996; Shirasu et al., 1997).

SA has also been shown to induce binding of a tobacco nuclear protein to a sequence conserved among stress-induced proteins, including PAL (Goldsborough et al., 1993), and to induce transcription from the as-1 element of the cauliflower mosaic virus via binding of a tobacco cellular factor, SARP (Jupin and Chua, 1996). Although it is unlikely that low levels of SA present in the phloem at 6 h after inoculation are sufficient to induce the SAR response, it is conceivable that SA may enhance its own vascular synthesis in response to the mobile signal by direct effects on the relevant genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway. The fact that SA has never been demonstrated to induce its own synthesis necessitates the involvement of an additional signal molecule to initiate the branch in the phenylpropanoid pathway leading to SA biosynthesis.

In summary, we have shown that the first measurable effect of the mobile signal for SAR in cucumber inoculated with P. syringae is the transient stimulation of PAL activity in the petiole of the inoculated leaf and in the stem above the inoculated leaf. The transient increase in PAL activity precedes a transient increase in SA and 4HBA in phloem fluids, and suggests that the two compounds are produced de novo in stems and petioles, perhaps in vascular tissues. If PAL gene expression is regulated by the mobile signal, a detailed analysis of PAL message accumulation in different tissues during SAR should provide insight into the movement of signal from the inoculated leaf. Furthermore, future efforts to identify the mobile signal for SAR in this system should focus on products of the HR that are able to modulate PAL activity and initiate the synthesis of SA in petioles and stems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sandy Stewart for supplying us with the cucumber chitinase ELISA assay and Ray Hammerschmidt for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations:

- 4HBA

4-hydroxybenzoic acid

- HR

hypersensitive response

- PAL

Phe ammonia-lyase

- SA

salicylic acid

- SAR

systemic acquired resistance

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from Ciba-Geigy.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bach M, Schnitzler JP, Seitz HU. Elicitor-induced changes in Ca2+ influx, K+ efflux, and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid synthesis in protoplasts of Daucus carota L. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:407–412. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan M, Shufflebottom D, Edwards K, Jefferson R, Schuch W. Tissue- and cell-specific activity of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase promoter in transgenic plants. EMBO J. 1989;8:1899–1906. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller T, Metraux JP. Extracellular localization of chitinase in cucumber. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1988;33:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principles of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron R, Dixon R, Lamb C. Biologically induced systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1994;5:715–725. [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Bowling S, Gordon A, Dong XN. Characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant that is nonresponsive to inducers of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1845–1857. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.11.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich R, Delaney T, Uknes S, Ward E, Ryals J, Dangl J. Arabidopsis mutants simulating disease response. Cell. 1994;77:565–577. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R, Kessmann H. Isoflavanoid phytoalexins and their biosynthetic enzymes. In: Gurr S, McPherson M, Bowles D, editors. Molecular Plant Pathology: A Practical Approach, Vol 2. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi A, Yalpani N, Silverman P, Raskin I. Localization, conjugation, and function of salicylic acid in tobacco during the hypersensitive reaction to tobacco mosaic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2480–2484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney T, Friedrich L, Vernooj B, Negrotto D, Nye G, Uknes S, Ward E, Kessmann H, Ryals J. Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science. 1993;261:754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5122.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsbrough A, Albrecht H, Stratford R. Salicylic acid-inducible binding of a tobacco nuclear protein to a 10 bp sequence which is highly conserved amongst stress-inducible genes. Plant J. 1993;3:563–571. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.03040563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt R, Nuckles EM, Kuc J. Association of enhanced peroxidase activity with induced systemic resistance of cucumber to Colletotrichum lagenarium. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1982;20:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Kuc J. Purification and characterization of an acidic β-1,3-glucanase from cucumber and its relationship to systemic disease resistance induced by Colletotrichum lagenarium and tobacco necrosis virus. MPMI. 1995;8:899–905. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupin I, Chua N-H. Activation of the CaMV as-1 cis-element by salicylic acid: differential DNA-binding of a factor related to TGA 1a. EMBO J. 1996;15:5679–5689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuc J. Induced immunity to plant disease. Bioscience. 1982;32:854–860. [Google Scholar]

- Leon J, Yalpani N, Raskin I, Lawton M. Induction of benzoic acid 2-hydroxylase in virus-inoculated tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:323–328. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.2.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyva A, Liang X, Pintor-Toro J, Dixon R, Lamb C. cis-Element combinations determine phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene tissue-specific expression patterns. Plant Cell. 1992;4:263–271. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Dron M, Schmid J, Dixon R, Lamb C. Developmental and environmental regulation of a phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-β-glucuronidase gene fusion in transgenic tobacco plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9284–9288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy J, Carr J, Kessig D, Raskin I. Salicylic acid: a likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science. 1990;250:1002–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4983.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauch-Mani B, Slusarenko A. Production of salicylic acid precursors is a major function of phenylalanine ammonia lyase in the resistance of Arabidopsis to Peronospora parasitica. Plant Cell. 1996;8:203–212. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metraux JP, Signer H, Ryals J, Ward E, Wyss-Benz M, Gaudin J, Raschdorf K, Schmid E, Blum W, Inverardi B. Increase in salicylic acid at the onset of systemic acquired resistance in cucumber. Science. 1990;250:1004–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4983.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metraux JP, Streit L, Staub T (1988) A pathogenesis-related protein in cucumber is a chitinase. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 33: 1–9

- Meuwly P, Molders W, Buchala A, Metraux JA. Local and systemic biosynthesis of salicylic acid in infected cucumber plants. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:1107–1114. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.3.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molders W, Buchala A, Metraux JP. Transport of salicylic acid in tobacco necrosis virus-infected cucumber plants. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:787–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.2.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mur L, Naylor G, Warner S, Sugars J, White R, Draper J. Salicylic acid potentiates defence gene expression in tissue exhibiting acquired resistance to pathogen attack. Plant J. 1996;9:559–571. [Google Scholar]

- Ohl S, Hedrick S, Chory J, Lamb C. Functional properties of a phenylalanine ammonia-lyase promoter from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1990;2:837–848. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.9.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallas J, Paiva N, Lamb C, Dixon R. Tobacco plants epigenetically suppressed in phenylalanine ammonia-lyase expression do not develop systemic acquired resistance in response to infection by tobacco mosaic virus. Plant J. 1996;10:281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen J, Hammerschmidt R, Zook M. Systemic induction of salicylic acid accumulation in cucumber after inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae pv syringae. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1342–1347. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryals J, Uknes S, Ward E. Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1109–1112. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler J-P, Madlung J, Rose A, Seitz H. Biosynthesis of ρ-hydroxybenzoic acid in elicitor-treated carrot cell cultures. Planta. 1992;188:594–600. doi: 10.1007/BF00197054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler J-P, Seitz H. Rapid responses of cultured carrot cells and protoplasts to an elicitor from the cell wall of Pythium aphanidermatum (Edson) Fitzp Z Naturforsch. 1989;44c:1020–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Shields S, Wingate V, Lamb C. Dual control of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase production and removal by its product cinnamic acid. Eur J Biochem. 1982;123:389–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb19781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasu K, Nakajima H, Krishnamachari R, Dixon R, Lamb C. Salicylic acid potentiates an agonist-dependent gain control that amplifies pathogen signals in the activation of defense mechanisms. Plant Cell. 1997;9:261–270. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.2.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulaev V, Leon J, Raskin R. Is salicylic acid a translocated signal of systemic acquired resistance in tobacco? Plant Cell. 1995;4:1691–1701. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.10.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Hammerschmidt R, Fulbright D. Rapid induction of systemic resistance in cucumber by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1991;38:223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Summermatter K, Sticher L, Metraux JP. Systemic responses in Arabidopsis thaliana infected and challenged with Pseudomonas syringae pv syringae. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1379–1385. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uknes S, Mauch-Mani B, Moyer M, Potter S, Williams S, Dincher S, Chandler D, Slusarenko A, Ward E, Ryals J. Acquired resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1992;4:645–656. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.6.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooj B, Friedrich L, Morse A, Reist R, Kolditz-Jawhar R, Ward E, Kessmann H, Ryals J. Salicylic acid is not the translocated signal responsible for inducing systemic acquired resistance but is required in signal transduction. Plant Cell. 1994;6:959–965. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.7.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E, Uknes S, Williams S, Dincher S, Wiederhold D, Alexander D, Ahl-Goy P, Metraux JP, Ryals J. Coordinate gene activity in response to agents that induce systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell. 1991;3:1085–1094. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.10.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]