Abstract

In the 1990s, Hendra virus and Nipah virus (NiV), two closely related and previously unrecognized paramyxoviruses that cause severe disease and death in humans and a variety of animals, were discovered in Australia and Malaysia, respectively. Outbreaks of disease have occurred nearly every year since NiV was first discovered, with case fatality ranging from 10 to 100%. In the African green monkey (AGM), NiV causes a severe lethal respiratory and/or neurological disease that essentially mirrors fatal human disease. Thus, the AGM represents a reliable disease model for vaccine and therapeutic efficacy testing. We show that vaccination of AGMs with a recombinant subunit vaccine based on the henipavirus attachment G glycoprotein affords complete protection against subsequent NiV infection with no evidence of clinical disease, virus replication, or pathology observed in any challenged subjects. Success of the recombinant subunit vaccine in nonhuman primates provides crucial data in supporting its further preclinical development for potential human use.

INTRODUCTION

Hendra virus (HeV) first appeared in Australia in 1994, with infection and fatal disease occurring in horses and humans. In total, two of three infected horse handlers and 15 horses succumbed to the fatal HeV disease (1). Nipah virus (NiV) appeared in peninsular Malaysia in 1998 in pigs and pig farmers. By mid-1999, more than 265 human cases of encephalitis, including 105 deaths, had been reported in Malaysia, and 11 cases of either encephalitis or respiratory illness with one fatality were reported in Singapore (1). Although HeV and NiV emerged independently, further characterization demonstrated that both viruses were paramyxoviruses that have similar biological, molecular, and serological properties that were distinct from those of all other paramyxoviruses, and consequently, they were grouped together as closely related viruses in the new Henipavirus genus (2). The known natural reservoir hosts of both HeV and NiV are pteropid fruit bats, commonly known as flying foxes, which do not exhibit clinical disease when infected (3). Numerous flying fox species have antibodies to HeV and NiV (4), and their vast geological range overlaps with all henipavirus outbreaks. Unlike all other paramyxoviruses, HeV and NiV have a broad species tropism, and in addition to infecting bats, they can infect and cause disease, often with very high fatality rates, in a wide range of species spanning six mammalian orders [reviewed in (5, 6)].

Fatal NiV outbreaks among people have occurred nearly annually [reviewed in (7, 8)] since 2001, and all outbreaks have occurred in Bangladesh or India, with the most recent appearance in January 2012 (9). Of significance, from 2001 to 2007, transmission of NiV from bats to humans occurred in the absence of an intermediate animal host, person-to-person transmission accounted for more than half of the identified NiV cases, and case fatality rates were typically >75% (8). In 2008 and 2009, there were three confirmed human HeV cases including two fatalities (10, 11); in 2010, two individuals had high-risk HeV exposure (12); and in 2011, an unprecedented 18 independent HeV outbreaks were reported in Australia (13, 14), which included numerous horse fatalities and cases of human exposure and the first evidence of HeV seroconversion in a farm dog (15). HeV spillovers into horses has since occurred on three occasions in 2012, first in early January outside the typical July-to-September period of most cases (16) and, most recently, in May with two simultaneous but geographically distant occurrences in Queensland resulting in additional equine mortalities and several low-risk human exposures (17).

Currently, there are no approved therapeutics or vaccines for HeV or NiV [reviewed in (7, 18)]. Traditionally, host antibody responses have been the immunological measure of vaccine efficacy, and historically, most neutralizing antibodies to enveloped viruses are directed against surface glycoproteins. In recent years, a recombinant soluble form of the HeV attachment (G) envelope glycoprotein (sGHeV) (19) has proven highly effective in protecting small animals from lethal NiV and HeV challenge when used as an immunogen (20, 21). These successful efficacy trials in concert with serological studies from naturally infected animals (22) have suggested that sGHeV is an ideal henipavirus vaccine immunogen. More recently, the development of nonhuman primate (NHP) models of NiV and HeV infection and disease were reported (23, 24). In these studies, infection of African green monkeys (AGMs) was uniformly lethal, and disease essentially mirrored the severe clinical symptoms and associated pathology seen in humans, with widespread systemic vasculitis and parenchymal lesions in multiple organ systems, in particular, lungs and brain, along with the development of clinical signs directly associated with damage of these organs. These AGM models currently represent the best animal models of human henipavirus–mediated disease (6), and evaluating vaccine candidates in them will likely be required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before the licensure of any vaccine for future human use. Recently, a highly efficacious human monoclonal antibody was found to protect NiV-infected ferrets and HeV-infected AGMs from lethal disease when administered after virus challenge (25, 26). In these studies, all animals treated after exposure recovered from infection and survived, representing the first post-exposure henipavirus therapeutic demonstrating in vivo efficacy. Clinical illness and transient viremia were noted in animals that received therapy 24 hours after exposure, and log increases in antibody titer were detected in all surviving animals, further indicating virus replication in protected animals. Here, we report the prophylactic efficacy of the sGHeV vaccine using the lethal NiV AGM challenge model. The data demonstrate that sGHeV vaccination elicits highly neutralizing antibody responses that prevent NiV infection and disease in AGMs. The immunogenicity of recombinant sGHeV, its ability to elicit cross-reactive neutralizing antibody titers, and its exceptional protective efficacy in NHPs demonstrate its prophylactic potential and provide crucial data in supporting potential licensure for future use in humans.

RESULTS

Vaccination and NiV challenge

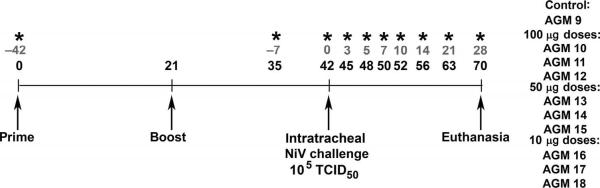

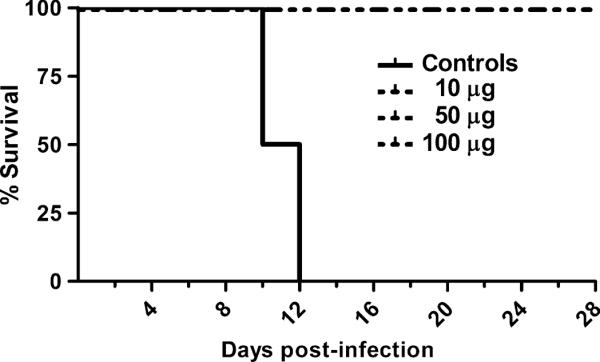

Previously, we have demonstrated that intratracheal inoculation of AGMs with 1 × 105 TCID50 (median tissue culture infectious dose) of NiV caused a uniformly lethal outcome (23, 24). Rapidly progressive clinical illness was noted in these studies. Clinical signs included severe depression, respiratory disease leading to acute respiratory distress, severe neurological disease, and severely reduced mobility, and time to reach approved humane endpoint criteria for euthanasia rangedfrom 7 to 12 days. Here, we sought to determine whether vaccination with sGHeV could prevent NiV infection and disease in AGMs. A timeline of the vaccination schedule, challenge, and biological specimen collection days is shown in Fig. 1. Doses of 10, 50, or 100 μg of sGHeV were mixed with alum and CpG moieties as described in Materials and Methods. Each vaccine formulation was administered intramuscularly to three subjects on day 0 (prime) and again on day 21 (boost), and one control subject (AGM 9) received an adjuvant-alone prime and boost on the same days. Vaccine formulations were delivered intramuscularly to mimic the most common human vaccine delivery route. Moreover, intramuscular injection was consistent with the delivery route used in previous sGHeV efficacy studies. On day 42, all subjects were inoculated intratracheally with 1 × 105 TCID50 NiV. The control subject (AGM 9), consistent with historical controls (23), showed loss of appetite, severe sustained behavioral changes (depression, decreased activity, and hunched posture), decreases in platelet number, and a gradual increase in respiratory rate at end-stage disease. Subsequently, AGM 9 developed acute respiratory distress and had to be euthanized according to the approved humane endpoints on day 10 after infection. In contrast, none of the vaccinated subjects had clinical disease and all survived until the end of the study. A Kaplan-Meier survival graph is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of sGHeV vaccination and NiV challenge schedule. Dates of sGHeV vaccination, NiV challenge, and euthanasia are indicated by arrows. Blood and swab specimens were collected on days −42, −7, 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28 after challenge as indicated (*). Gray text denotes challenge timeline; black text denotes vaccination timeline. AGM numbers for subjects in each vaccine dose group and one control subject are shown.

Fig. 2.

Survival curve of NiV-infected subjects. Data from control subjects (n = 2) and sGHeV-vaccinated subjects (n = 9) were used to generate the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Control included data from one additional historical control subject. Vaccinated subjects received 10, 50, or 100 μg of sGHeV administered subcutaneously twice. Average time to end-stage disease was 11 days in control subjects, whereas all vaccinated subjects survived until euthanasia at the end of the study.

NiV-mediated disease in the control subject

Gross pathological changes in the control subject were consistent with those found previously in NiV-infected AGMs (23). Splenomegaly and congestion of blood vessels on the surface of the brain were present, and all lung lobes were wet and heavy. NiV RNA and infectious virus were not recovered from AGM 9 blood samples, and there was no evidence of viremia. Serum immunoglobulin (Ig) levels were determined using previously published multiplexed microsphere assays (26), and AGM 9 had considerable levels of NiV G-specific IgM and detectable NiV G-specific IgG and IgA (fig. S1A). Conversely, NiV fusion (F) glycoprotein-specific IgM was not detected in the control subject at any time, which is similar to previous HeV and NiV challenge studies where animals that succumbed to lethal disease did not seroconvert to HeV (20, 21) or NiV F. Moreover, recently, it was demonstrated that in AGMs that survive infection, anti-HeV F antibodies did not appear until day 13 after challenge (26). Further analysis of tissue samples revealed an extensive NiV tissue tropism similar to the widespread NiV infection seen previously in AGMs (23). As demonstrated in fig. S1B, AGM 9 had NiV RNA in most tissues as indicated, and infectious virus was recovered from numerous tissues. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or stained by immunohistochemical techniques using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against recombinant NiV nucleoprotein as previously described (26). Noteworthy lesions included interstitial pneumonia, subacute encephalitis, and necrosis and hemorrhage of the splenic white pulp. Alveolar spaces were filled by edema fluid, fibrin, karyorrhectic and cellular debris, and alveolar macrophages. Multifocal encephalitis was characterized by the expansion of Virchow-Robins space by moderate numbers of lymphocytes and fewer neutrophils. Smaller numbers of these inflammatory cells extended into the adjacent parenchyma. Numerous neurons were swollen and vacuolated (degeneration) or were fragmented with karyolysis (necrosis). Multifocal germinal centers of follicles in splenic white pulp were effaced by hemorrhage and fibrin, as well as small numbers of neutrophils and cellular and karyorrhectic debris. These findings were consistent with necrosis and loss of the germinal centers in the spleen. Representative tissue sections from AGM 9 lung and brainstem are shown in fig. S1C. The extensive amounts of viral antigen in the brainstem highlight the extensive damage NiV causes in the central nervous system.

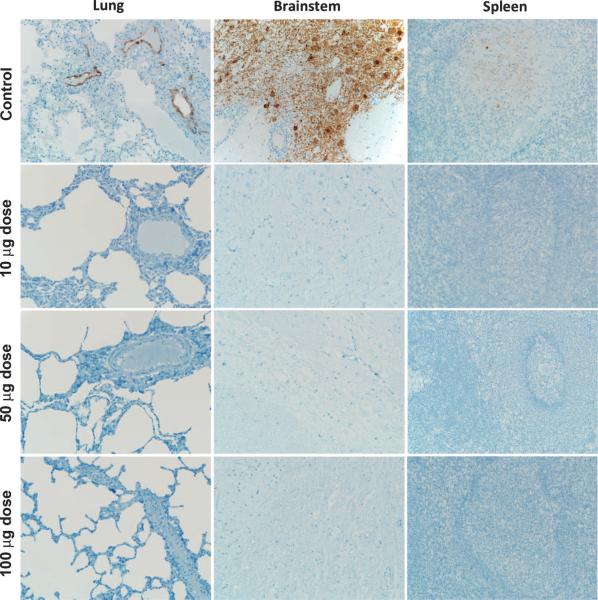

Protection of sGHeV-vaccinated subjects

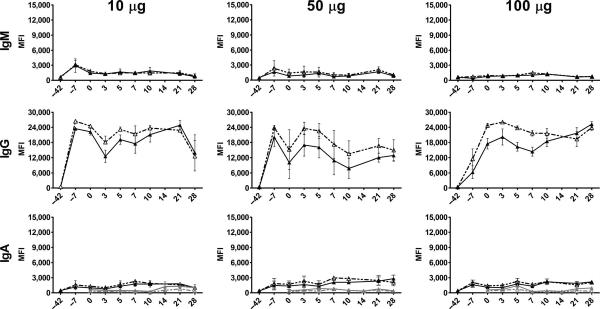

All biological specimens, including all blood samples collected after challenge and all tissues collected upon necropsy, were negative for NiV RNA and infectious virus was not isolated from any specimen. Upon closer examination of tissue sections from vaccinated subjects, tissue architecture appeared normal and NiV antigen was not detected in any tissue using immunohistochemical techniques. Representative examples of tissue sections from the control and vaccinated subjects are shown in Fig. 3. To further dissect the vaccine-elicited mechanisms of protection, we measured serum and mucosal sGNiV-and sGHeV- specific IgM, IgG, and IgA, as well as NiV and HeV serum neutralization titers in vaccinated animals. Ig levels were determined using the multiplexed microsphere assay (26), and serum neutralization assays were done as described previously (24). As demonstrated in Fig. 4, 7 days before challenge, subjects receiving the lowest sGHeV dose had detectable antigen-specific serum IgM and the highest level of sGHeV-specific serum IgG. Subjects given 50 μg of sGHeV also had detectable levels of serum IgM and their highest levels of serum IgG 7 days before challenge. High-vaccine dose subjects had no detectable serum IgM, and serum IgG levels were considerably lower on day −7 compared to those of the other two groups. By the day of NiV challenge, serum IgG levels in the high-dose subjects had increased and all vaccinated subjects had similar IgG levels. Serum IgM levels did not change in any subject after NiV challenge. Serum IgG levels decreased in the medium-dose subjects the day of NiV challenge, and IgG levels decreased in low-dose subjects just after NiV challenge. IgG levels increased in both of these groups by days 3 and 5 after infection but never surpassed the IgG levels present 7 days before challenge, and in both groups, titer decreased considerably by day 28 after infection.

Fig. 3.

Absence of NiV antigen in sGHeV-vaccinated subjects. Lung, brainstem, and spleen tissue sections were stained with an N protein-specific polyclonal rabbit antibody, and images were obtained at an original magnification of 20×.

Fig. 4.

NiV- and HeV-specific Ig in vaccinated subjects. Serum and nasal swabs were collected from vaccinated subjects, and IgG, IgA, and IgM responses were evaluated using sGHeV and sGNiV multiplexed microsphere assays. Sera or swabs from subjects in the same vaccine dose group (n = 3) were assayed individually, and the mean of microsphere MFIs was calculated, which is shown on the y axis. Error bars represent the SEM. Serum sG-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA are shown in black (sGHeV and sGNiV), and mucosal sG-specific IgA is shown in gray (sGHeV and sGNiV).

Conversely, serum IgG levels in the high-dose group remained high and were at their highest at day 28 after infection. Antigen-specific serum IgA was detectable in all subjects after vaccination; however, the levels were very low and pre- and post-challenge levels did not appear to be meaningfully different (Fig. 4). A minimal increase in mucosal antigen-specific IgA was detected in nasal swabs from low-dose subjects on day 14 after infection; however, the levels were so low that these mucosal antibodies likely played no role in preventing the spread of NiV after challenge. Results from serum neutralization tests (SNTs) are shown in Table 1. For most vaccinated subjects, HeV-specific serum neutralization titer remained the same compared to pre-challenge neutralization titers and decreased by day 28 after infection. Slight increases in HeV-specific neutralization titers were observed in two subjects that had the lowest pre-challenge HeV-specific neutralization titer. Similarly, NiV-specific serum neutralization titer did not increase by day 7 after infection compared to pre-challenge NiV-specific neutralization titers, except in subjects that had the lowest titer before challenge, and increases were only slight. By day 14 after infection, one low-dose and one high-dose subject had a log increase in NiV-specific neutralization titer, and one medium-dose subject had a log increase in NiV-specific neutralization titer by day 21 after infection. For the remaining vaccinated animals, changes in NiV-specific neutralization titers were either inconsistent (titer would increase and then decrease) or not substantial (titer increased by three- to fourfold but not more than a log). Previous post-exposure efficacy trials of a henipavirus G–specific human monoclonal antibody in NiV-infected ferrets and HeV-infected AGMs have demonstrated that in addition to therapeutic antibody levels, a robust primary immune response to the other viral surface glycoprotein (F) correlated with the recovery from NiV- or HeV-mediated infection and disease (25, 26). Conversely, sGHeV-vaccinated ferrets subsequently challenged with HeV do not mount a robust primary immune response after HeV challenge, and anti-F antibodies are almost undetectable (20, 21). To further assess the primary immune response after NiV challenge in vaccinated AGMs, we assayed plasma samples from NiV-infected AGMs for the presence of NiV F–specific IgM. As demonstrated in fig. S2, minimal levels of serum anti-NiV F IgM were detected in the low- and medium-dose subjects on days 10 and 21 after infection, respectively, and these low median fluorescence intensity (MFI) values suggest a very weak primary antibody response after NiV challenge. Serum anti–NiV F IgM was not detected in the high-dose subjects, suggesting that these animals had little to no stimulation of the immune system, suggesting an absence of circulating virus after challenge.

Table 1.

HeV and NiV serum neutralization titers in vaccinated AGMs. Reciprocal serum dilution at which 50% of virus was neutralized.

| Day* |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sGHeV doses (μg) | AGM | −42 | −7 | 7 | 14 | 28 | −42 | −7 | 7 | 14 | 28 |

|

|

|

||||||||||

| HeV | NiV | ||||||||||

| 0† | 9 | <20 | <20 | 24 | ‡ | ‡ | <20 | <20 | <20 | ‡ | ‡ |

| 10 | 16 | <20 | >2560 | >2560 | >2560 | 1074 | <20 | 379 | 226 | >2560 | 2147 |

| 17 | <20 | >2560 | >2560 | 905 | 537 | <20 | 134 | 134 | 537 | 453 | |

| 18 | <20 | >2560 | >2560 | 453 | 537 | <20 | 189 | 134 | 189 | 453 | |

| 50 | 13 | <20 | >2560 | >2560 | >2560 | 757 | <20 | 379 | 189 | 189 | 453 |

| 14 | <20 | 1514 | >2560 | >2560 | 537 | <20 | 28 | 47 | 226 | 134 | |

| 15 | <20 | 2147 | 757 | >2560 | 905 | <20 | 67 | 95 | 757 | 1074 | |

| 100 | 10 | <20 | >2560 | 2147 | 1810 | 453 | <20 | 67 | 113 | 268 | 453 |

| 11 | <20 | >2560 | >2560 | >2560 | 1514 | <20 | 134 | 189 | 905 | 1514 | |

| 12 | <20 | >2560 | >2560 | >2560 | 757 | <20 | 189 | 226 | >2560 | 1514 | |

Day after NiV challenge.

Received adjuvant alone.

Not sampled; shading indicates increase in serum neutralization titer.

Although, collectively, the anti-NiV antibody data suggest that the host's immune systems responded to NiV challenge, the low levels or absence of NiV F–specific IgM and the minimal changes in IgG and neutralizing titer suggest that the primary immune response after NiV challenge was not robust in vaccinated animals. Instead, the spread of NiV in vivo was most likely controlled in all subjects by the presence of NiV-specific neutralizing antibodies that were elicited by sGHeV vaccination before NiV challenge. Although all vaccinated subjects were protected from NiV infection and disease, the high dose of sGHeV (100 μg) appeared to generate the most sustained IgG response, increased NiV SNT titer on day 14 after infection in all animals, which increased further by day 28, and the weakest primary immune response after challenge suggesting the lowest levels of circulating virus after challenge. Together, these data suggest that vaccination with the high-dose sGHeV formulation affords near-sterilizing immunity to the host. In the low- and medium-dose sGHeV vaccinations, although protection from infection and disease was impressive, IgG appeared to wane by day 28 after challenge, and weak IgM responses to NiV F suggest that undetectable amounts of virus were circulating in the host.

Complete protection of sGHeV-vaccinated AGMs from NiV infection and disease represents a major milestone toward licensure of an NiV vaccine for potential human use. Demonstrating complete protection in an NHP model of NiV-mediated disease that closely parallels human disease provides key efficacy data in a relevant species, which is a critical component of any vaccine licensure and a definite requirement of the FDA.

DISCUSSION

Outbreaks of both HeV and NiV have been occurring on an annual basis in Australia and Bangladesh, respectively, over the past several years, and for both viruses, the dynamics of disease, emergence and transmission, appear to be changing. Review of HeV and NiV human cases has demonstrated that both viruses cause severe respiratory and/or severe neurological disease, and long-term neurological sequelae or relapsing encephalitis has been documented in HeV- and NiV-infected individuals (11, 27, 28). In Bangladesh, direct transmission of NiV from flying foxes to humans appears to account for most outbreaks and person-to-person transmission of NiV has been well documented with high case fatality [reviewed in (8, 29)]. For HeV, human infection and exposures have also increased; an extraordinary number of independent spillover events occurred between bats and horses in 2011, and recently, the first case of HeV sero-conversion in an Australian farm dog was documented (14, 15). These alarming findings are having major impacts and have led to changes in practices in both Bangladesh and Australia. In Bangladesh, individuals have been encouraged to stop drinking fresh date palm sap, an ancient tradition (30, 31), and in Australia, veterinarians are ceasing equine medicine to avoid HeV exposure (32).

Developing effective countermeasures for high-hazard pathogens such as HeV and NiV is a complex process. Because traditional clinical trials are not possible, the efficacy of potential countermeasures must be evaluated in multiple animal models where disease closely parallels human disease and the pathogenic processes are well understood. Additionally, the mechanism of protection must be elucidated during efficacy trials. To date, the efficacy of sGHeV has been evaluated in two animal models of HeV-mediated disease, ferret (21) and equine (33), and two animal models of NiV-mediated disease, feline (20)and an NHP (presented here). In these studies, all vaccinated animals developed high levels of antigen-specific and cross-reactive NiV-specific serum IgG and neutralizing antibodies before challenge and all animals were protected from HeV or NiV disease. Moreover, there was no evidence of clinical disease or infectious virus in any vaccinated animal across all these efficacy trials. Various henipavirus strains, including NiV-Malaysia, HeV-1994, and HeV-Redlands, were used in these efficacy trials, and studies to evaluate protection against NiV-Bangladesh still need to be completed; however, given the sequence homology between NiV-Malaysia and NiV-Bangladesh and the demonstrated cross-reactive protective immunity elicited by sGHeV, we would expect sGHeV-vaccinated subjects to be protected from NiV-Bangladesh challenge. Although efficacy trials have not yet been completed in HeV-infected NHPs, sGHeV will most likely afford complete protection against homologous HeV challenge as it has been able to do in both cats and horses. Due to the recent escalation and geographic spread of recurrent HeV outbreaks in Australia, the use of the sGHeV immunogen described here as a veterinary vaccine is now in commercial development for use in horses in Australia with an anticipated target date for availability sometime in 2013 (17, 34). The immunogenicity and exceptional efficacy of sGHeV in protecting NHPs against NiV-mediated disease represents a major vaccine milestone toward licensure of a human vaccine, providing strong justification for further development of sGHeV as a recombinant subunit vaccine against NiV and HeV for potential human use, and a single subunit vaccine against both viruses would be ideal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Statistics

Conducting animal studies, in particular NHP studies, in biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) severely restricts the number of animal subjects, the volume of biological samples that can be obtained, and the ability to repeat assays independently, thus limiting statistical analysis. Consequently, data are presented as the means or medians calculated from replicate samples, not replicate assays, and error bars represent the SD across replicates.

Viruses

NiV-Malaysia (GenBank no. AF212302) was provided by the Special Pathogens Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA). NiV was propagated and titered on Vero cells as described for HeV in (24). All infectious virus work was performed in the BSL-4 of the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML; Hamilton, MT), according to the Standard Operating Protocols (SOPs) approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Vaccine formulation

Three vaccine formulations of sGHeV were used (10, 50, or 100 μg). Production and purification of sGHeV were done as previously described (21). Each vaccine formulation also contained Allhydrogel (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corporation) and CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) 2006 (InvivoGen) with a fully phosphorothioate backbone. Vaccine doses containing a fixed amount of ODN 2006, varying amounts of sGHeV, and aluminum ion (at a weight ratio of 1:25) were formulated as follows: 100-μg dose: 100 μg of sGHeV, 2.5 mg of aluminum ion, and 150 μg of ODN 2006; 50-μg dose: 50 μg of sGHeV, 1.25 mg of aluminum ion, and 150 μg of ODN 2006; and 10-μg dose: 10 μg of sGHeV, 250 μg of aluminum ion, and 150 μg of ODN 2006. For all doses, Allhydrogel and sGHeV were mixed first before ODN 2006 was added. Each vaccine dose was adjusted to 1 ml with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and mixtures were incubated on a rotating wheel at room temperature for at least 2 to 3 hours before injection. Each subject received the same dose of 1 ml for prime and boost, and all vaccine doses were given via intramuscular injection.

Animals

Ten young adult AGMs (Chlorocebus aethiops), weighing 4 to 6 kg (Three Springs Scientific Inc.) were caged individually. Subjects were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of ketamine (10 to 15 mg/kg) and vaccinated with sGHeV by intramuscular injection on day −42 (prime) and day −21 (boost). Vaccine formulations are described below. Three subjects received two doses of 10 μg (AGM 16, AGM 17, and AGM 18), three subjects received two doses of 50 μg (AGM 13, AGM 14, and AGM 15), three animals received two doses of 100 μg (AGM 10, AGM 11, and AGM 12), and one subject (AGM 9) received adjuvant alone. On day 0, subjects were anesthetized and inoculated intratracheally with 1 × 105 TCID50 of NiV in 4 ml of Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) (Sigma-Aldrich). Subjects were anesthetized for clinical examinations including temperature, respiration rate, chest radiographs, blood draw, and swabs of nasal, oral, and rectal mucosa on days 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28 after infection, and clinical examinations were performed as previously described (35). The control subject (AGM 9) had to be euthanized according to the approved humane endpoints on day 10 after infection. All other subjects survived until the end of the study and were euthanized on day 28 after infection. Upon necropsy, various tissues were collected for virology and histopathology. Tissues sampled include conjunctiva, tonsil, oro/nasopharynx, nasal mucosa, trachea, right bronchus, left bronchus, right lung upper lobe, right lung middle lobe, right lung lower lobe, left lung upper lobe, left lung middle lobe, left lung lower lobe, bronchial lymph node (LN), heart, liver, spleen, kidney, adrenal gland, pancreas, jejunum, colon transversum, brain (frontal), brain (cerebellum), brainstem, cervical spinal cord, pituitary gland, mandibular LN, salivary LN, inguinal LN, axillary LN, mesenteric LN, urinary bladder, testes or ovaries, and femoral bone marrow. Vaccination was done under BSL-2 containment. NiV challenge experiments were conducted under BSL-4 containment, and approval for all experiments was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the RML. All animal work was performed by a certified staff in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved facility at RML.

Specimen processing

Blood was collected in EDTA, sodium citrate, or serum Vacutainers (Beckton Dickinson). Immediately after sampling, 140 μl of blood was added to 560 μl of AVL viral lysis buffer (Qiagen Inc.) for RNA extraction. Serum was frozen for chemical and serological assays. For tissues, about 100 mg was stored in 1 ml of RNAlater (Qiagen Inc.) for a minimum of 24 hours to stabilize RNA, and about 100 mg was stored for virus isolation. For tissues stored in RNAlater, RNAlater was completely removed and tissues were homogenized in 600 μl of RLT buffer in a 2-ml cryovial with Qiagen tissue lyser and stainless steel beads. An aliquot representing about 30 mg was added to a fresh RLT buffer (final volume of 600 μl) (Qiagen Inc.) for RNA extraction. All blood samples in AVL viral lysis buffer and tissue samples in RLT buffer were removed from the BSL-4 laboratory with approved SOPs. RNA was isolated from blood and swabs with the QIAamp Viral RNA Kit (Qiagen Inc.) and from tissues with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions supplied with each kit.

Sera and mucosa antigen-specific antibody assays

Sera or mucosal swabs were inactivated by γ irradiation (50 μGy; 1 Gy = 100 rads). The sG-specific Ig levels were determined with previously published multiplexed microsphere assays (26). Antibodies to the fusion (F) glycoprotein were measured in NiV-infected subjects simultaneously by including a recombinant soluble NiV F (sFNiV) glycoprotein-coupled microsphere in the assay. Coupling of sF to microsphere 43 (Luminex Corporation) was done as described previously (26). Sera were diluted 1:1000 for IgG assays and 1:100 for IgA and IgM assays; swabs were assayed neat, and biotinylated goat anti-monkey IgG, IgA, and IgM (Fitzgerald Industries International) were diluted 1:500. As-says were performed on a Luminex 200 IS machine equipped with Bio-Plex Manager Software (v. 5.0) (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.). MFI and the SD of fluorescence intensity across 100 beads were determined for each sample. The mean MFI was calculated for subjects in the same vaccine dose group and results were plotted as the means ± SEM.

NiV and HeV SNTs

Neutralization titers were determined by microneutralization assay. Briefly, sera were heat-inactivated at 56°C for 1 hour, serially diluted twofold, and incubated with 100 TCID50 of NiV or HeV for 1 hour at 37°C. Virus and antibodies were then added to a 96-well plate with 2 × 104 Vero E6 per well in four wells per antibody dilution. Wells were checked for cytopathic effect (CPE) 3 days after infection, and the 50% neutralization titer was determined as the serum dilution at which at least 50% of wells showed no CPE.

NiV TaqMan polymerase chain reaction

NiV nucleocapsid (n) gene-specific primers, an NiV n gene-specific probe (25), and Qiagen QuantiFast Probe real-time RT-PCR (real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) kits were used according to the manufacturer's protocols. RNA from specimens was assayed once (n = 1) in triplicate with a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time System. All reactions contained 2 μl of RNA; master mixes were set up according to the manufacturer's protocols, and each reaction was done in a total volume of 25 μl. For blood, 2 μl of RNA represented 4.7 μl of whole blood, and for tissues, 2 μl of RNA represented 1.2 mg of tissue. To account for plate-to-plate variation and to quantify NiV RNA in biological samples, a standard curve of NiV RNA, isolated from the original NiV inoculum, was run on each TaqMan plate. Inoculum-purified RNA was diluted such that 2 μl represented 1.8, 188, or 1880 TCID50 NiV of the original inoculum. NiV RNA standards were assayed in triplicate, and the average Ct was set to a relative n gene expression value of 1, 10, and 100, respectively. Sample Ct values were analyzed against known Ct values generated from the standard curve of NiV RNA, and a relative NiV n gene expression value was extrapolated from the standard curve for each sample replicate. Ct value analysis was done with Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time Software, and data are shown as the mean relative NiV n gene expression level ± SD.

NiV isolation

Vero cells were seeded in 24-well plates in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 mg/ml). Tissues were weighed and homogenized (1:10 weight/volume in PBS) in a 2-ml cryovial for 8 min with Qiagen tissue lyser and stainless steel beads. Homogenates were clarified by centrifugation and diluted 1:10 with DMEM containing 1% FCS, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 mg/ml; DMEM-1). Duplicate wells were inoculated with 200 μl of a 1% tissue homogenate and incubated at 37°C. One well was incubated for 30 min and one well was incubated overnight; both were washed once with PBS and cultured in 1 ml of DMEM-1. Cultures were examined for the presence or absence of syncytia/CPE for 5 days. Negative samples were passaged twice onto new cells before being deemed negative.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Necropsy was performed on all subjects. Tissue samples of all major organs were collected for histopathologic and immunohistochemical examination and were immersion-fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 7 days in BSL-4. Subsequently, formalin was changed; specimens were removed from BSL-4 under approved SOPs, were processed in BSL-2 by conventional methods, and embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm. Tissues for immunohistochemistry were stained on the Discovery XT automated stainer (Ventana Medical Systems Inc.) with an anti-Nipah nucleoprotein antibody (1:5000) and the DAB Map Detection Kit (Ventana Medical Systems Inc.). Nonimmune rabbit IgG was used as a negative staining control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Rocky Mountain Veterinary Branch for animal care and veterinary support. We also thank J. A. Koster from Boston University for his help with molecular assays.

Funding: These studies were supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID, NIH, and in part by the Department of Health and Human Services, NIH, grants AI082121 and AI057159 to T.W.G.; AI054715 and AI077995 to C.C.B.; and the Intramural Biodefense Program of the NIAID.

Footnotes

Author contributions: K.N.B., B.R., H.F., C.C.B., and T.W.G. designed the studies. B.R., H.F., T.W.G., F.F., D.B., and J.B.G. contributed to performance of experiments and data collection and analysis. B.R., H.F., and T.W.G. performed gross pathological analysis. B.R., K.N.B., and A.C.H. performed serological and nucleic acid analysis experiments and data collection. Y.-R.F. and Y.-P.C. produced, purified, and quality controlled the sG and sF glycoproteins and provided critical reagents. D.S. performed histological analysis, and J.B.G., R. L., and D.B. facilitated the conduct of the in vivo animal studies. K.N.B., C.C.B., B.R., H.F., and T.W.G. wrote and edited the manuscript. C.C.B. prepared the final versions of the manuscript, figures, and supplementary materials.

Competing interests: C.C.B., H.F., F.F., D.B., and D.S. are U.S. federal employees. K.N.B. and C.C.B. are coinventors on a pending U.S. patent and Australian patent 2005327194, pertaining to soluble forms of Hendra and Nipah G glycoproteins; assignees are the United States of America as represented by the Department of Health and Human Services (Washington, DC) and the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine Inc. (Bethesda, MD). All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/4/146/146ra107/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Eaton BT, Broder CC, Middleton D, Wang L-F. Hendra and Nipah viruses: Different and dangerous. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton BT, Mackenzie JS, Wang L-F. Henipaviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 1587–1600. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpin K, Hyatt AD, Fogarty R, Middleton D, Bingham J, Epstein JH, Rahman SA, Hughes T, Smith C, Field HE, Daszak P, Henipavirus Ecology Research Group Pteropid bats are confirmed as the reservoir hosts of henipaviruses: A comprehensive experimental study of virus transmission. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011;85:946–951. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field HE, Mackenzie JS, Daszak P. Henipaviruses: Emerging paramyxoviruses associated with fruit bats. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;315:133–159. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong KT, Ong KC. Pathology of acute henipavirus infection in humans and animals. Patholog. Res. Int. 2011;2011:567248. doi: 10.4061/2011/567248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, Broder CC. Animal challenge models of Henipavirus infection and pathogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/82_2012_208. 10.1007/82_2012_208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broder CC. Henipavirus outbreaks to antivirals: The current status of potential therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luby SP, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Ahmed BN, Banu S, Khan SU, Homaira N, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Comer JA, Kenah E, Ksiazek TG, Rahman M. Recurrent zoonotic transmission of Nipah virus into humans, Bangladesh, 2001–2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1229–1235. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nipah encephalitis, human—Bangladesh: Jipurhat. ProMED-mail (International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2012 Jan 25; archive no. 20120125.1022056); http://www.promedmail.org.

- 10.Hendra virus, human, equine—Australia: Queensland. ProMED-mail (International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2009 Aug 20; archive no. 20090821.2963); http://www. promedmail.org.

- 11.Playford EG, McCall B, Smith G, Slinko V, Allen G, Smith I, Moore F, Taylor C, Kung YH, Field H. Human Hendra virus encephalitis associated with equine outbreak, Australia, 2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:219–223. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.090552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendra virus, equine—Australia (03): Queensland, human exposure. ProMED-mail (International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2010 May 22; archive no. 20100522.1699); http://www.promedmail.org.

- 13.Hendra virus, equine—Australia (07): Queensland, New South Wales, human exposure. ProMED-mail (International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2011 Jul 6; archive no. 20110706.2045); http://www.promedmail.org.

- 14.Hendra virus, equine—Australia (27): Queensland. ProMED-mail (International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2011 Oct 12; archive no. 20111012.3057); http://www.promedmail.org.

- 15.Hendra virus, equine—Australia (19): Queensland, canine. ProMED-mail (International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2011 Jul 28; archive no. 20110728.2267); http://www.promedmail.org.

- 16.Hendra virus, equine—Australia: Queensland. ProMED-mail (International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2012 Jan 6; archive no. 20120106.1001359); http://www.promedmail.org.

- 17.Hendra virus, equine—Australia (04): Queensland, vaccine research. ProMED-mail (International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2012 Jun 1; archive no. 20120601.1152600); http://www.promedmail.org.

- 18.Bossart KN, Bingham J, Middleton D. Targeted strategies for Henipavirus therapeutics. Open Virol. J. 2007;1:14–25. doi: 10.2174/1874357900701010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bossart KN, Crameri G, Dimitrov AS, Mungall BA, Feng Y-R, Patch JR, Choudhary A, Wang L-F, Eaton BT, Broder CC. Receptor binding, fusion inhibition, and induction of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies by a soluble G glycoprotein of Hendra virus. J. Virol. 2005;79:6690–6702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6690-6702.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McEachern JA, Bingham J, Crameri G, Green DJ, Hancock TJ, Middleton D, Feng Y-R, Broder CC, Wang L-F, Bossart KN. A recombinant subunit vaccine formulation protects against lethal Nipah virus challenge in cats. Vaccine. 2008;26:3842–3852. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pallister J, Middleton D, Wang L-F, Klein R, Haining J, Robinson R, Yamada M, White J, Payne J, Feng Y-R, Chan Y-P, Broder CC. A recombinant Hendra virus G glycoprotein-based subunit vaccine protects ferrets from lethal Hendra virus challenge. Vaccine. 2011;29:5623–5630. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bossart KN, McEachern JA, Hickey AC, Choudhry V, Dimitrov DS, Eaton BT, Wang L-F. Neutralization assays for differential henipavirus serology using Bio-Plex Protein Array Systems. J. Virol. Methods. 2007;142:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geisbert TW, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Hickey AC, Smith MA, Chan Y-P, Wang L-F, Mattapallil JJ, Geisbert JB, Bossart KN, Broder CC. Development of an acute and highly pathogenic nonhuman primate model of Nipah virus infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockx B, Bossart KN, Feldmann F, Geisbert JB, Hickey AC, Brining D, Callison J, Safronetz D, Marzi A, Kercher L, Long D, Broder CC, Feldmann H, Geisbert TW. A novel model of lethal Hendra virus infection in African green monkeys and the effectiveness of ribavirin treatment. J. Virol. 2010;84:9831–9839. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01163-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bossart KN, Zhu Z, Middleton D, Klippel J, Crameri G, Bingham J, McEachern JA, Green D, Hancock TJ, Chan Y-P, Hickey AC, Dimitrov DS, Wang L-F, Broder CC. A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against lethal disease in a new ferret model of acute Nipah virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000642. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bossart KN, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, Zhu Z, Feldmann F, Geisbert JB, Yan L, Feng Y-R, Brining D, Scott D, Wang Y, Dimitrov AS, Callison J, Chan Y-P, Hickey AC, Dimitrov DS, Broder CC, Rockx B. A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects African green monkeys from Hendra virus challenge. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:105ra103. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong KT, Shieh W-J, Kumar S, Norain K, Abdullah W, Guarner J, Goldsmith CS, Chua KB, Lam SK, Tan CT, Goh KJ, Chong HT, Jusoh R, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Zaki SR, Nipah Virus Pathology Working Group Nipah virus infection: Pathology and pathogenesis of an emerging paramyxoviral zoonosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;161:2153–2167. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64493-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong KT, Robertson T, Ong BB, Chong JW, Yaiw KC, Wang LF, Ansford AJ, Tannenberg A. Human Hendra virus infection causes acute and relapsing encephalitis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2009;35:296–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2008.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luby SP, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Blum LS, Husain MM, Gurley E, Khan R, Ahmed BN, Rahman S, Nahar N, Kenah E, Comer JA, Ksiazek TG. Foodborne transmission of Nipah virus, Bangladesh. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:1888–1894. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nahar N, Sultana R, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ, Luby SP. Date palm sap collection: Exploring opportunities to prevent Nipah transmission. Ecohealth. 2010;7:196–203. doi: 10.1007/s10393-010-0320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone R. Epidemiology. Breaking the chain in Bangladesh. Science. 2011;331:1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6021.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendez DH, Judd J, Speare R. Unexpected result of Hendra virus outbreaks for veterinarians, Queensland, Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:83–85. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.111006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balzer M. Hendra vaccine success announced. Aust. Vet. J. 2011;89:N2–N3. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.news_v89_i7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broder CC, Geisbert TW, Xu K, Nikolov DB, Wang LF, Middleton D, Pallister J, Bossart KN. Immunization strategies against henipaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/82_2012_213. 10.1007/82_2012_213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brining DL, Mattoon JS, Kercher L, LaCasse RA, Safronetz D, Feldmann H, Parnell MJ. Thoracic radiography as a refinement methodology for the study of H1N1 influenza in cynomologus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) Comp. Med. 2010;60:389–395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.