Abstract

Dengue is a viral disease usually transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Dengue outbreaks in the Americas reported in medical literature and to the Pan American Health Organization are described. The outbreak history from 1600 to 2010 was categorized into four phases: Introduction of dengue in the Americas (1600–1946); Continental plan for the eradication of the Ae. aegypti (1947–1970) marked by a successful eradication of the mosquito in 18 continental countries by 1962; Ae. aegypti reinfestation (1971–1999) caused by the failure of the mosquito eradication program; Increased dispersion of Ae. aegypti and dengue virus circulation (2000–2010) characterized by a marked increase in the number of outbreaks. During 2010 > 1.7 million dengue cases were reported, with 50,235 severe cases and 1,185 deaths. A dramatic increase in the number of outbreaks has been reported in recent years. Urgent global action is needed to avoid further disease spread.

Introduction

Dengue is a disease caused by dengue virus serotypes 1 to 4 (DENV-1 to DENV-4) generally transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.1 Most dengue infections are asymptomatic; however, when symptomatic, the virus can cause mild dengue fever (DF), or more severe forms of the disease, including dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), or dengue shock syndrome (DSS).2–4

Dengue infections occur in more than 100 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, the Americas, the Middle East, and Africa, and cases of infection continue to rise worldwide.3–5 Approximately 50 million infections are estimated to occur each year.3 Dengue incidence rates are increasing mainly in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, and in the Americas, a dramatic increase of cases has been reported during the last decades.6,7

Dengue in the Americas has an endemo-epidemic pattern with outbreaks every 3 to 5 years. In this work, we summarize dengue outbreaks reported in the medical literature and to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Based on the epidemiological patterns of the disease, mainly determined by the reported circulation of the dengue viruses and the main vector (Aedes aegypti) we considered four time periods: Introduction of dengue in the Americas (1600–1946); Plan for the eradication of the Ae. aegypti (1947–1970); Aedes aegypti reinfestation (1971–2000); Increased dispersion of Ae. aegypti and dengue virus circulation (2001–2010).

Introduction of Dengue in the Americas (1600–1946)

The first suspected dengue-like epidemics were reported in 1635 in Martinique and Guadeloupe and in 1699 in Panama; however, it is difficult to attribute these outbreaks to dengue without a detailed clinical picture.8–11 Although the etiology of the first reported outbreaks is unknown, the description of the 1780 Philadelphia outbreak in the United States by Benjamin Rush is clearly the DF syndrome caused by dengue viruses.12 In the 19th century, dengue outbreaks were common in port cities of the Caribbean, North, Central, and South America and mostly related to commercial activities.13,14 In 1818, a dengue-like disease outbreak in Peru accounted for ∼50,000 cases.8,9 Between 1827 and 1828, an extended outbreak involving the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico was also reported. This outbreak started in the Virgin Islands and further extended to Cuba, Jamaica, Colombia, Venezuela, some port cities in the southern United States (New Orleans, Pensacola, Savannah, and Charleston), and Mexico.15–17 Although this outbreak was originally described as dengue, the clinical characteristics of the cases were classic chikungunya disease, strongly suggesting that its cause was chikungunya virus.18 The historical record suggests this outbreak was the sole introduction of chikungunya into the American Region as a consequence of the African slave trade.11 It was during the 1828 epidemic in Cuba that the disease was first called Dunga, later changed to dengue.19 Between 1845 and 1849 there is some evidence of dengue-like outbreaks in New Orleans,15 Cuba,20 and Brazil.8,9 An epidemic of dengue-like disease was reported after 1850 in different cities of the United States (New Orleans, Mobile, Charleston, Augusta, and Savannah) and Havana, Cuba.15,21–23 In 1851, evidence of dengue-like disease was also reported in Lima, Peru.8,9 In the following years, sporadic outbreaks were mentioned in the Gulf and Atlantic seaports in the United States, being the largest in 1873 in New Orleans, with 40,000 people affected,24 and followed by another large epidemic in several southern United States port cities between 1879 and 1880.25,26 By the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, a wider distribution of dengue-like disease was observed including countries as far north from the United States and as far south to Chile and Argentina. Between 1880 and 1912 outbreaks were reported in Curitiba, Brazil27; Iquique, Antofagasta, Tarapacá, Tacna, and Arica, Chile (1889)28,29; Texas (1885–86),30,31 (1897),32 and Florida (1898–99)33; Havana, Cuba (1897)34; Bahamas (1882)15; Bermuda (1882)35; and the Isthmus of Panama (1904 and 1912).36,37 During the following years epidemics were reported in the Virgin Islands38; Puerto Rico (1915)39,40; Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (1916)41; and Corrientes and Entre Rios, Argentina (1916).42 In 1918 an outbreak was reported in Galveston Texas,43 followed by another outbreak of larger proportions in 1922 with an estimated 30,000 cases of dengue-like disease.44,45 This outbreak further expanded throughout Texas15 and Louisiana, following the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad, the main transport link between the two states46; Florida and Georgia.15,47 During the same year an outbreak was reported in Niteroi Brazil.48 In 1934 an extended epidemic started in Miami affecting ∼10% of the population and then spread to the rest of Florida and to the south of Georgia.49,50 During 1941–1946, dengue continued to spread in the Region with outbreaks in Texas (1941)51; the Panama Canal Zone (1941–1942),52 where evidence of DENV-2 circulation from neutralization tests was subsequently identified53; Havana, Cuba (1944)54; Puerto Rico (1945)55; Caracas, Venezuela (1945–46)56; the Bermudas; the Bahamas; and Sonora, Mexico.9,15

The modern era of dengue research started in 1943–44 when dengue viruses were isolated for the first time57–59 and diagnostic laboratory tests were available thereafter. Although identification of the serotype could be done by retrospective detection of antibodies, description of most epidemics in this period was based on clinical and epidemiological features (i.e., dengue-like illness). Moreover, it has been observed that other viruses that cause dengue-like disease, such as yellow fever, Mayaro, or chikungunya viruses, may have been involved in these epidemics either instead of dengue or concomitantly with dengue.18,60

Continental Plan for the Eradication of the Ae. aegypti (1947–1970)

The first initiative to eliminate the Ae. aegypti was undertaken by William Gorgas in Havana Cuba in 1901.61 He was influenced by Carlos Finlay's theory on the role of the mosquito as a vector of yellow fever presented in Havana, Cuba in 188162 and later confirmed by Walter Reed and collaborators in 1900.63 Gorga's initiative was followed by similar programs undertaken in Sorocaba, Sao Paolo, Brazil in 1901, and by Oswaldo Cruz in Rio de Janeiro in 1903.64 The technique was based on the control of the mosquito by means of fumigation and the elimination of mosquito foci, by destroying abandoned containers. After an epidemic of yellow fever in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1928 and the discovery by Soper in Brazil of jungle yellow fever in 1932, it was thought that complete protection to urban populations depended on absolute eradication of the Ae. aegypti.64 The Rockefeller Foundation then established an intensive campaign against the vector in collaboration with the Government of Brazil, eliminating mosquitoes in vast areas of the country. Similar results were obtained in other countries such as Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru.64 In the 1940s the Pan American Health Conference began to highlight prevention and control measures against Ae. aegypti in Brazil.65 The advent of DDT, fostered the notion of mosquito eradication not only on a nationwide but on a continent-wide scale. This led to the approval by PAHO of the Continental Ae. aegypti eradication plan in 1947 to fight urban yellow fever.66 Since 1947, the Pan American Sanitary Bureau (PASB) intensely promoted campaigns in all affected countries, establishing cooperative support agreements providing personnel and material for program execution. The success of the PASB hemispheric campaign was demonstrated by 1962, when 18 continental countries and a number of Caribbean islands had achieved eradication.67

Possibly as a result of these efforts, only one single dengue virus appeared to remain in circulation by the middle of the 20th century.14 This virus, American genotype DENV-2, genotype V, was isolated for the first time from the blood of a patient with DF in Trinidad in 1953.68

Despite the Regional efforts to eradicate the vector, Ae. aegypti was not eradicated in Cuba, the United States, Venezuela, and several Caribbean countries. Two main epidemics occurred during this period, in countries that had not eradicated the vector. The first one in 1963–1964, starting in Jamaica69 (∼1,500 cases), spreading to Puerto Rico (27,000 cases),70 Lesser Antilles,71 and Venezuela (10,000 cases).72 The DENV-3, genotype V, a virus of Asian origin, was isolated during this outbreak.14 The second epidemic that occurred during 1968–1969 also began in Jamaica,73 spreading to Puerto Rico,74,75 Haiti,9 the Lesser Antilles,76 and Venezuela.77 The DENV-3 and DENV-2 were isolated in Jamaica, whereas only DENV-2 was isolated in Puerto Rico,74,75 the Lesser Antilles,76 and Venezuela.77

Unfortunately, decades of unprecedented human efforts to eradicate Ae. aegypti fell apart very rapidly. Between 1962 and 1972 only three additional countries or territories eliminated the vector despite PAHO's reiterated commitment to the eradication policy.67 The deterioration of the eradication program over time was due mainly to the lost of political importance in most of the countries that had achieved eradication. Moreover, the surveillance gradually declined such that small reinfestations could no longer be detected, and the program's centralized structure resulted in a slow response to reinfestations. In addition, the insufficient environmental sanitation in the rapidly growing urban centers and rapid expansion of international and domestic travel, favored the passive mosquito dispersion. Other factors contributing to the deterioration of the eradication program included: the development of mosquito resistance to DDT and other organochlorine insecticides; high material and wage costs; insufficient community participation or support from the health sector; and unwillingness on the part of some governments to join in simultaneous programs.67

Aedes aegypti Reinfestation (1971–1999)

The deterioration of the control programs during the 1960s lead to the reintroduction and expanding geographic distribution of the mosquito, and subsequent outbreaks caused by different dengue serotypes in several countries of the Region.

Until 1977 DENV-2 and DENV-3 continued to circulate. Outbreaks associated with DENV-2 were reported in Colombia in 1971–197278,79 and in the southern part of Puerto Rico and DENV-2 in 1972–73 where cases continued to occur until 1975.9 A DENV-3 epidemic was also reported in upper Magdalena Valley, Colombia in 1975–1977.80 In 1977 DENV-1, genotype III, was reported for the first time in the Region and caused an epidemic beginning in Jamaica, expanding to Cuba, Puerto Rico, and most islands in the Caribbean,81 and subsequently to the rest of the northern countries of South America, Central America, and Mexico by 1978,13,82 and Texas in 1980.82 Countries in the Americas reported ∼702,000 cases during 1977–1980, and DENV-1 was the predominant serotype.

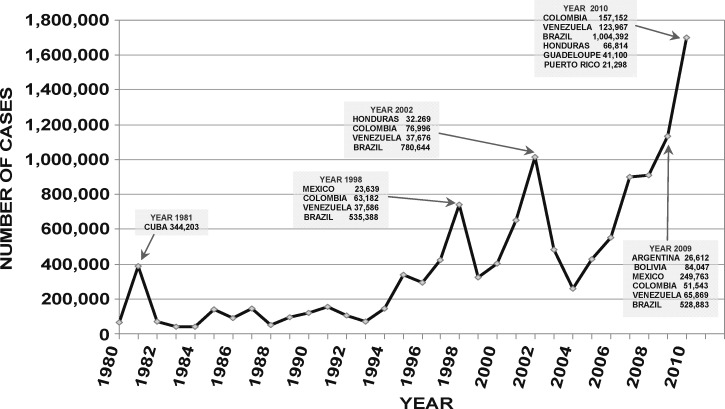

At the beginning of the 1980s, the number of reported cases started to increase considerably, and this trend was maintained during the following decades (Figure 1). In 1981, Cuba reported an epidemic with 344,203 cases, including 10,312 cases of DHF and 158 deaths (101 child deaths).83,84 This epidemic was caused by DENV-2, genotype III,14 and it was the first main DHF epidemic reported in the region. This outbreak is considered one of the worst in this period because of the number of cases, deaths, and control costs.85 Furthermore, in 1981, DENV-4, genotype I, was introduced into the eastern Caribbean islands, and subsequently expanded to the rest of the Caribbean, Mexico, Central, and South America causing in many cases epidemics in countries that had experienced DENV-1 outbreaks.86,87 Some of these outbreaks were associated with the sporadic cases of DHF: Suriname (1982), Mexico (1984), Puerto Rico (1986), and El Salvador (1987).87,88 DENV-4 was the virus predominantly isolated in these epidemics, although other serotypes were also present.82

Figure 1.

Evolution of dengue in the Americas, 1980–2010.

During the 80s there was a marked geographical spread of dengue activity in the Region.89 In Brazil, an epidemic was reported in 1981–1982 in the state of Roraima, where DENV-1 and DENV-4 were identified.90 In 1986 DENV-1 was introduced in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil,91–93 spreading to other regions of the country.94,95 The DENV-1 expanded and caused outbreaks in other countries that had been free of dengue for decades or had not experienced the disease before such as Bolivia (1987), Paraguay (1988), Ecuador (1988), and Peru (1990).89

Despite an increasing number of cases in the region during the 80s, the incidence of DHF remained low until 1989, when a second major DHF epidemic was reported in Venezuela during 1989–1990 with over 6,000 cases and 73 deaths. This epidemic was related to DENV-1, -2, and -4 and DENV-2 was predominant and specifically associated with fatal cases.96 This virus was the same genotype (genotype III) as the virus that caused the epidemic in Cuba in 198197,98 and also responsible for subsequent smaller DHF epidemics in Colombia, Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Brazil.82 The DENV-2, genotype III, was introduced in Rio de Janeiro in 1990 during a period of DENV-1 serotype circulation.99,100 The DENV-2 spread to other parts of Brazil with more severe clinical presentations, and the first fatal cases caused by secondary dengue infections.101–104 Of interest, an epidemic caused by DENV-2, with the same genotype as the strain that was present before 1981, occurred in the Amazonian region of Peru in 1995 however no DHF cases were reported.105

The DENV-3, genotype III, virus was reintroduced in the Americas in 1994 initially reported in Nicaragua and Panama.106,107 In Nicaragua, 29,469 cases including 1,247 DHF case were reported in 1994,106,107 and 19,260 cases were reported in 1995.6 The DENV-3 subsequently expanded to Central American countries and Mexico in 1995, Puerto Rico in 1998, and other Caribbean islands, causing major epidemics in several Central American countries, Mexico,108,109 and later to South America.110–112

In 1996, PAHO approved a Continental Plan to intensify Ae. aegypti control; however, it was not fully implemented.113 A small, isolated outbreak of DHF/DSS caused by DENV-2 was documented in Santiago de Cuba, Cuba in 1997.114 In 1998, a significant increase in the number of cases was reported in the Region (Figure 1) with widespread circulation of the disease in most countries. Brazil reported > 500,000 cases with widespread outbreaks in 16 states,95 and epidemics were reported in many countries including Argentina where the disease had not been recorded for 82 years.115,116

Increased Dispersion of Ae. aegypti and Dengue Virus Circulation (2000–2010)

During 2000–2010 an unprecedented increase in the number of cases was reported in the Americas, circulating all four serotypes and reaching the highest record of cases ever reported during a decade. During this period, two Pan American outbreaks occurred in 2002 and 2010. Below we describe both Pan American outbreaks and the largest outbreaks that occurred in other years in individual countries corresponding to the highest peak during the decade for the respective country:

Ecuador – outbreak 2000.

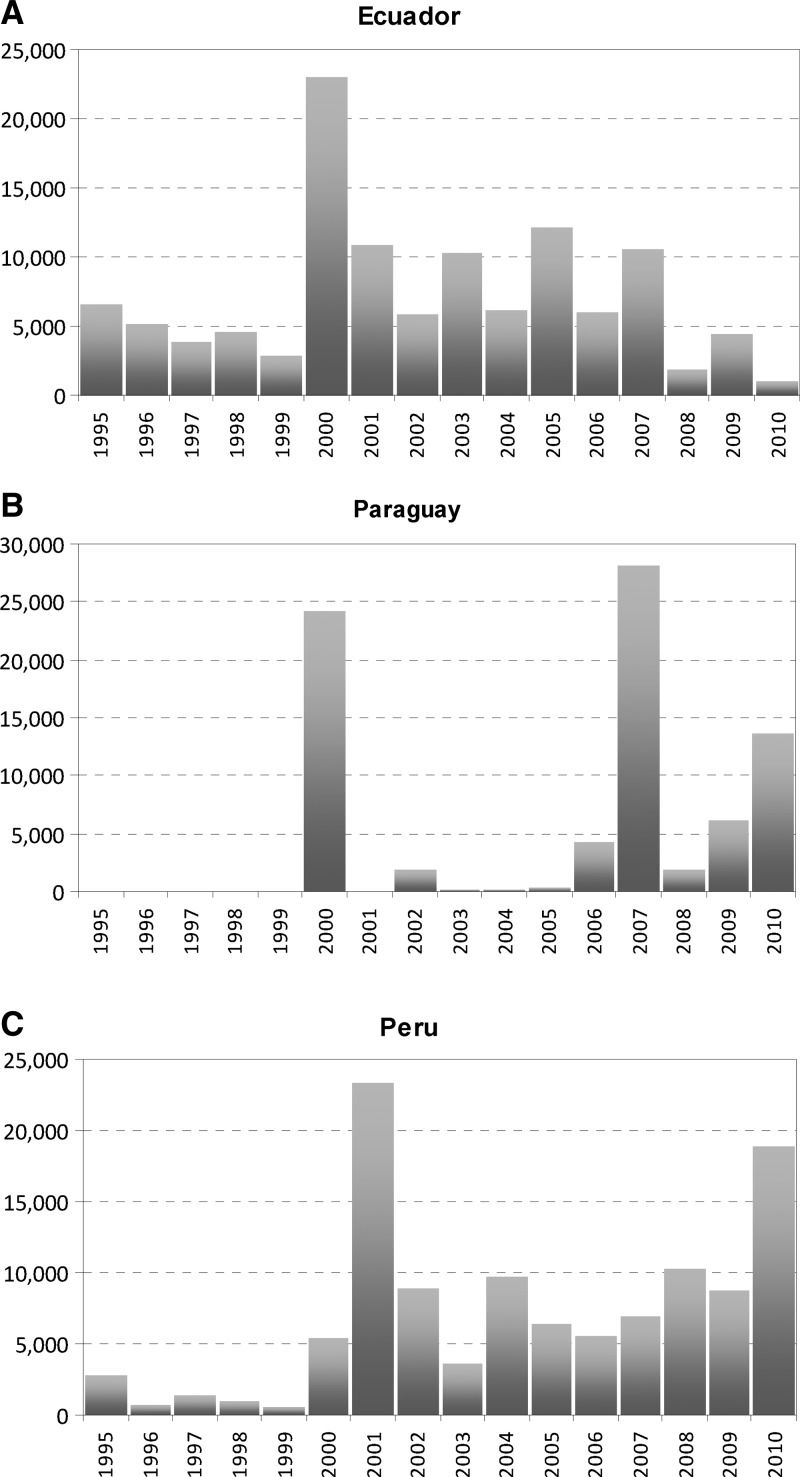

In 2000, an outbreak in Ecuador included 22,937 cases reported to PAHO. Four serotypes were circulating at that time and the circulation of DENV-2 and DENV-3 were later confirmed by the National Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine of Ecuador. Few DHF cases were reported6,117 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Number of dengue cases Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru, 1995–2010.

Paraguay – outbreak 2000.

In Paraguay, after 10 years without dengue activity, an epidemic caused by DENV-1 was reported in 2000 with ∼25,000 reported cases. No DHF cases were reported. The DENV-1 was the only serotype detected during this outbreak6,118 (Figure 2B).

Peru – outbreak 2001.

In 2001 Peru had its worst dengue outbreak to date, with 23,329 cases reported to PAHO. Four serotypes were isolated and DHF cases were reported for the first time6,119,120 (Figure 2C).

Pan American – outbreak 2002.

During 2002 a record number of 1,015,420 cases were reported, including 14,374 DHF cases and 255 deaths. Brazil accounted for > 75% of the total number of cases in the Region. During the summer of 2002, Rio de Janeiro had a large epidemic of DF; 288,245 cases with 1,831 cases of DHF were reported during the first half of the year,121 with most cases occurring in adults.95 Although DENV-1 and DENV-2 were circulating, DENV-3 was observed in the majority of cases.121 This serotype was introduced in Rio de Janeiro Brazil in 2000,110 which subsequently spread to other areas of the country.122,123 The countries with the highest incidence rates were Honduras (490 of 100,000), Trinidad and Tobago (480 of 100,000), Brazil (452 of 100,000), Costa Rica (314 of 100,000), and El Salvador (286 of 100,000). In Central America 83,179 cases were reported. Honduras (32,269 cases), El Salvador (18,307 cases), and Costa Rica (12,251 cases) reported the highest number of cases. In the Andean Sub Region, Colombia (76,996 cases), and Venezuela (37,676 cases) had the highest number of cases. In the Caribbean Sub Region, Trinidad and Tobago (6,246 cases), Dominican Republic (3,194 cases), and Cuba (3,011cases) had the highest number of cases. Countries with the highest mortality rates were Dominican Republic (18.4%), Nicaragua (7.6%), Brazil (5.5%), El Salvador (2.7%), and Honduras (1.9%). Although all serotypes were circulating, the most frequent was DENV-3, followed by the DENV-2 when a serotype could be identified.6

Costa Rica – outbreak 2005.

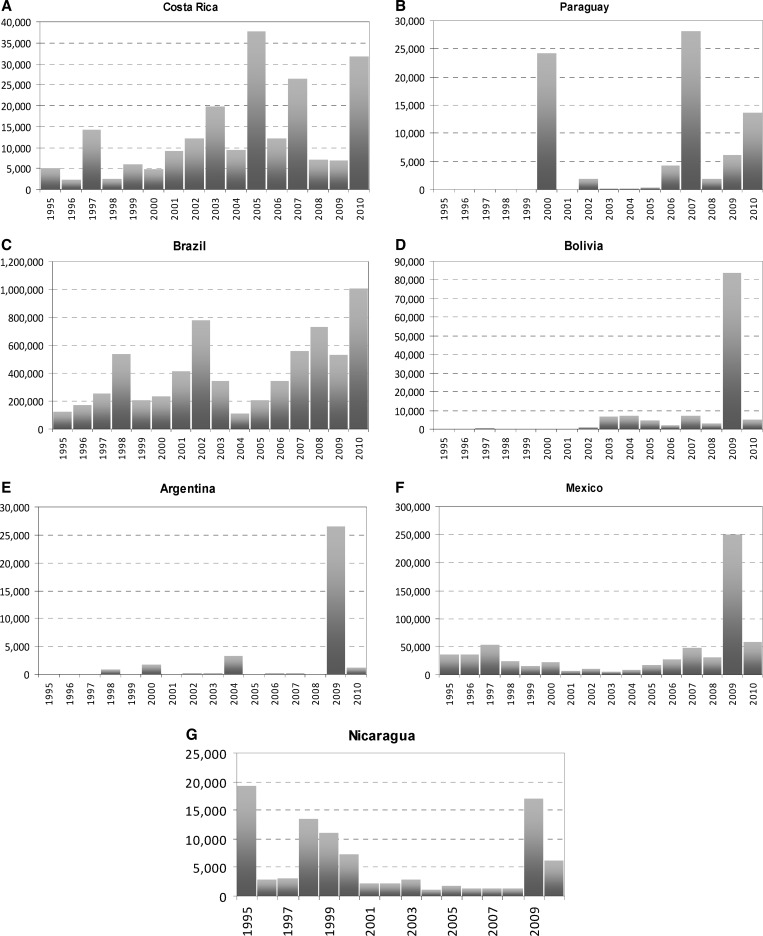

In 2005, an unprecedented dengue epidemic occurred in Costa Rica, with almost 38,000 cases and 45 of them classified as DHF. Confirmed cases increased almost three times the number reported the previous year. Although DENV-1 was circulating in 2005, DENV-2 was reintroduced in the country at that time6,124 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Number of dengue cases Costa Rica, Paraguay, Brazil, Bolivia, Argentina, Mexico, and Nicaragua, 1995–2010.

Paraguay – outbreak 2006–2007.

In 2006 a dengue epidemic began, and most of the cases were reported in the city of Asunción. By the end of 2006, ∼4,200 dengue cases were reported, and DENV-3 circulation was confirmed (Figure 3B).

From January until April 9, 2007, 25,021 cases were reported at the national level, including 52 DHF cases and 13 deaths. Mortality rates were 11.5%, and the most affected age group was 15–29 years of age followed by 1–14 years of age. The most affected departments were Asuncion, Central, Amambay, Alto Parana, Cordillera, and Guaira. By the end of the year ∼28,000 cases were reported (Figure 3B).

Brazil – outbreak 2007–2008.

In 2007 559,954 suspected dengue cases were reported (Figure 3) with 1,514 DHF cases and 158 deaths.125 Most cases in 2008 occurred in the first half of the year. In that year, 734,384 suspected dengue cases were reported (Figure 3C) (incidence 425 of 100,000), with 9,957 complicated cases and 225 deaths.126 Most cases (43.7%) were reported in the state of Rio de Janeiro followed by the state of Ceará (10.6%). A change in the age pattern with a trend toward younger ages was observed in this outbreak. In 2008, the incidence was highest (599.4 of 100,000) among children < 10 years of age in the state of Ceará.127 Although DENV-1, -2, and -3 were circulating, cases with the most medical complications were associated with DENV-2.

Bolivia – outbreak 2009.

In March 2007, more dengue cases were reported, mostly in the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. In 2007 many areas in Bolivia were flooded caused by the El Niño phenomenon and by the end of that year, 7,332 dengue cases were reported with 109 DHF cases and one death. In 2008, 3,004 cases were reported; however, the incidence began to increase by the end of that year. By June 2009 the outbreak was under control with > 84,000 cases6 (Figure 3D), 198 DHF cases, 25 deaths, and a mortality rate of 12.6%. Most of the cases (71%) were concentrated in the Department of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. During this epidemic, DENV-1, -2, and -3 were detected.

Argentina – outbreak 2009.

During the first half of 2009, Argentina experienced a dengue outbreak caused by DENV-1 with > 26,000 confirmed cases6 (Figure 3E), five deaths caused by DHF and DSS. For the first time in Argentina, there were deaths caused by dengue and in primary infections.128 This outbreak was settled mainly in Chaco, Catamarca, and Salta provinces.

Mexico – outbreak 2009.

In 2009 almost 250,000 cases were reported to PAHO in an outbreak where the predominant serotype isolated was DENV-1, followed by DENV-2; however, serotypes 3 and 4 were also detected6,129,130 (Figure 3F).

Nicaragua – outbreak 2009.

In 2009, Nicaragua experienced the largest epidemic in over a decade with 17,140 reported cases. The DENV-3 was isolated in the majority of cases, although DENV-1 and DENV-2 were also detected. An unusual clinical presentation characterized by poor peripheral perfusion (“compensated shock”) was also observed131 (Figure 3G).

Pan American – outbreak 2010.

More than 1.7 million cases, 50,235 clinically severe, and 1,185 deaths were reported in 2010, with an incidence > 200 cases/100,000 in several countries (Figure 1). The case fatality rate of dengue in the Americas that year was 2.6%. Several countries in the region suffered dengue outbreaks with a total number of cases exceeding the recorded historical data including the introduction of dengue in Key West, Florida.132 The most affected countries and territories are described below:

Colombia 2010.6

Colombia suffered the worst dengue epidemic in its history in 2010. This outbreak began in the first week of the year and peaked by epidemiological week (EW) 11, with cases holding constant for more than 10 consecutive weeks. By the end 2010, there were 157,152 reported cases (9,482 were DHF) with 217 deaths, with a case fatality rate (CFR) of 2.3%. All dengue serotypes were identified during the 2010 outbreak, with particular prevalence of DENV-2. The most effected departments were Antioquia, Bolivar (Cartagena), and Sucre.

Venezuela 2010.6

There were 123,967 reported dengue cases, 10,203 of them were severe dengue. Venezuela was the third country of the Region reporting dengue cases and the second reporting severe cases. No deaths were reported.

Brazil 2010.6

The number of affected people exceeded 1 million cases for the first time in Brazilian history (Figure 3C), nearly double the number of cases observed in the previous year. Of these, 17,489 people were diagnosed with DHF, and 656 deaths were reported.

The outbreak in Brazil has particular relevance because of the active circulation of DENV-4. This serotype was reported in 2008 for the first time since 1982 from three patients that had not traveled outside Manaus.133 All four dengue serotypes of dengue were identified during the outbreak, with the southeast and midwest areas as the most affected areas.

Honduras 2010.6

Honduras had the worst epidemic of dengue and severe dengue in 2010, with 66,814 cases (3,266 severe cases), and 83 deaths. The peak of major reported cases occurred between EW24 and EW34, affecting mainly young people, with ages between 5 and 19 years old. All four serotypes circulated; however, the most prevalent was DENV-2 (92.5%).134

Caribbean 2010.6

The Caribbean was the Sub Region most affected by outbreaks in 2010:

Guadeloupe and Martinique 2010.

The incidence of these two epidemics was the highest one among all 2010 outbreaks. The number of reported cases climbed to 41,100 in Guadeloupe and exceeded 37,000 in Martinique. Despite the increased number of cases in Guadeloupe, Martinique had a higher case fatality rate (CFR) (2.3%, almost twice as much as Guadeloupe).

Dominican Republic 2010.

A high mortality rate of dengue cases (over 5%) to the EW 33 was a notable feature of this outbreak. By year's end and after a clear downward trend in the later months of 2010, the CFR decreased to 3.79%. The number of cases was 12,170 (1110 were diagnosed as DHF and there were 49 deaths).

Puerto Rico 2010.

Puerto Rico also faced a dramatic epidemic, following the same epidemiological pattern observed in the Dominican Republic. The number of reported cases was 21,298 reported, all 36 cases diagnosed with DHF died.

Regional Efforts

In 2001, PAHO established a reference frame for the generation of prevention and control programs against dengue, which proposed social communication, increased community participation, education, and environmental strategies (e.g., water and waste disposal) as key strategies.135

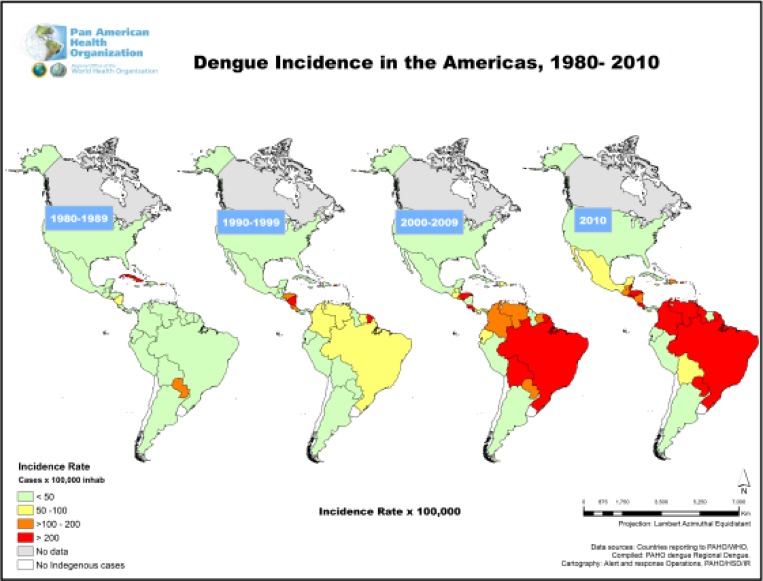

After the increasing number of cases and incidence in the region (Figures 1 and 4), PAHO approved the adoption of the Integrated Management Strategy for Dengue Prevention and Control (IMS-dengue) in February 2003.136,137 This strategy is based on a model consisting of six components; epidemiology, entomology, healthcare, laboratory, social communication, and environment.

Figure 4.

Dengue incidence in the Americas, 1980–2010.

As of 2010, 19 countries and territories have implemented the IMS - dengue (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Uruguay, and Venezuela). In addition, four sub-regional IMS-dengue plans have been developed in Central America, the Andean Sub Region, MERCOSUR, and Caribbean country members. Moreover, in these last years the laboratory network, RELDA (Red de Laboratorios de Dengue de Las Américas) was strengthened through a comprehensive training, monitoring and assessment plan.

Conclusions

A trend toward higher DF and DHF incidence rates has been observed during the last decades, with indigenous transmission in almost all countries of the Region. Over the last three decades, a 4.6-fold increase in reported cases was observed in the Americas (∼1 million cases during the 80s to 4.7 million during 2000–7).7

This review shows the changing epidemiology of dengue in the Americas, particularly after the failure of the Ae. aegypti eradication initiative. The occurrence of recurring outbreaks every 3–5 years with an increasing number of cases over time shows the transition from an endemic-epidemic state to a highly endemic state in recent years.

The only control measure currently available is vector control, but this method has proven difficult to maintain over time. The implementation of the IMS-dengue has contributed to an integrated response to outbreaks; however, all its components should be strengthened. Additional control measures such as the development of effective tetravalent vaccines, more modern vector control programs, and full implementation of the IMS-dengue are needed to reduce the disease burden in the coming years.138

Footnotes

Disclosure: Betzana Zambrano and Gustavo H. Dayan are employees of Sanofi Pasteur, Inc. This statement is made in the interest of full disclosure and not because the authors consider this to be a conflict of interest. The manuscript was a collaboration between the authors. No funding was involved in the development of the manuscript. Information of this manuscript was presented at the 60th ASTMH Annual Meeting Philadelphia on December 5, 2011.

Authors' addresses: Olivia Brathwaite Dick, Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Washington, DC, E-mail: brathwao@paho.org. José L. San Martín, Romeo H. Montoya, and Jorge del Diego, Dengue Regional Program, Pan American Health Organization, San José, Costa Rica, E-mails: sanmarjl@cor.ops-oms.org, montoyah@paho.org, and jorgedel diego@gmail.com. Betzana Zambrano, Clinical Department, Sanofi Pasteur, Montevideo, Uruguay, E-mail: betzana.zambrano@sanofipasteur.com. Gustavo H. Dayan, Clinical Department, Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA, E-mail: gustavo.dayan@sanofipasteur.com.

References

- 1.Gould EA, Solomon T. Pathogenic flaviviruses. Lancet. 2008;371:500–509. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60238-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George R, Lum LC. Clinical spectrum of dengue infection. In: Gubler DJ, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. London: CAB International; 1997. pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. 2009. pp. 1–160.http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241547871_eng.pdf Available at. Accessed October 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. 1997. pp. 1–58.http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/dengue/Denguepublication/en/ Available at. Accessed August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . Comprehensive Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Dengue and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever. Second edition. World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2011. pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (Number of reported cases of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), Region of the Americas (by country and subregion) from 1995 through 2010).http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=264&Itemid=363&lang=en Available at. Accessed October 2011.

- 7.San Martín JL, Brathwaite O, Zambrano B, Solórzano JO, Bouckenooghe A, Dayan GH, Guzmán MG. The epidemiology of dengue in the Americas over the last three decades: a worrisome reality. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:128–135. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic: its history and resurgence as a global public health problem. In: Gubler DJ, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. London: CAB International; 1997. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider J, Droll D. A Time Line for Dengue in the Americas to December 31, 2000 and Noted First Occurrences. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2001. www.paho.org/English/HCP/HCT/VBD/dengue_finaltime.doc Available at. Accessed May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mc Sherry JA. Some medical aspects of the Darien scheme: was it dengue? Scott Med J. 1982;27:183–184. doi: 10.1177/003693308202700215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halstead SB. Dengue: overview and history. In: Pasvol G, editor. Tropical Medicine: Science and Practice. London: Imperial College Press; 2008. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rush AB. Medical Inquiries and Observations. Philadelphia, PA: Prichard and Hall; 1789. An account of the bilious remitting fever, as it appeared in Philadelphia in the summer and autumn of the year 1780; pp. 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzmán MG, Kourí G. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in the Americas: lessons and challenges. J Clin Virol. 2003;27:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(03)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halstead SB. Dengue in the Americas and Southeast Asia: do they differ? Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;20:407–415. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892006001100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrenkranz NJ, Ventura AK, Cuadrado RR, Pond WL, Porter JE. Pandemic dengue in Caribbean countries and the southern United States–past, present and potential problems. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1460–1469. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forry S. Remarks on epidemic cholera, inebriety, Hemeralopia, colica saturnine and dengue. Am Med Sci. 1842;3:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hays I. On dengue. Am J Med Sci. 1828;3:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carey DE. Chikungunya and dengue: a case of mistaken identity? J Hist Med. 1971;26:243–262. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/xxvi.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muñoz Bernal JA. Memoria sobre la epidemia que ha sufrido esta ciudad, nombrada vulgarmente el dengue. Oficina del Gobierno y Capitanía General. Habana. 1828;1:26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guiteras J, Cartaya JT. El dengue en Cuba: su importancia y su diagnóstico con la fiebre amarilla. Rev Med Trop Habana. 1906;7:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fenner ED. Special report on the fevers of New Orleans in the year 1850. South Med Rep. 1851;2:79–99. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickson SH, Wragg WT, Campbell HF. A descriptive account of the epidemic fever called dengue, as it prevailed at Charleston, SC, and Augusta GA, during the summer of 1850. Trans Am M Assoc. 1851;4:211–225. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold RD. Dengue, or break-bone fever, as it appeared in Savannah in the summer and fall of 1850. Savannah J Med. 1858;1:233–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bemiss SM. Dengue. New Orleans Med Surg J. 1880;8:501–512. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falligant LA. The dengue fever of 1880 in Savannah, Georgia. North Am J Homoeopath. 1881;11:529–558. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prioleau JF. The epidemic of dengue – as it prevailed the city of Charleston, SC, 1881. Rep Board Health S Carolina Charleston. 1881;2:197–212. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reis TJ. A febre dengue in Curityba. Gazeta Medica da Bahia. 1896;97:163–266. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benavente D. Chronicle. Rev Med Chil. 1899;18:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astaburuaga L. Epidemia de fiebre dengue en Iquique. Bol Med Marzo-Abril. 1890:53–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Editorial The epidemic of dengue in Texas. Daniel's Med J. 1885;1:190–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menger R. Dengue fever in San Antonio: yellow fever compared. Tex Med News. 1897;7:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamond IB. The epidemic of dengue at Houston, Texas: clinical report of cases. Med Newsl (Lond) 1898;72:329–331. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rerick RH. Memoirs of Florida. Volume 2. Atlanta, GA: Southern Historical Association; 1902. pp. 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delfin M, Coronado TV. Dengue en la Habana en 1897. Cron Med Quir de la Habana. 1897;23:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Last year's epidemic of dengue in Bermuda. NY Med J. 1883;38:322–323. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carpenter DN, Sutton RL. Dengue in the Isthmian Canal Zone: including a report on the laboratory findings. J Am Med Assoc. 1905;44:214–216. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beverley EP, Lynn WJ. The reappearance of dengue on the Isthmus of Panama. Proc Med Ass Isthmian Canal Zone. 1912;5:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lane FF. A clinical study of 100 cases of dengue at St. Thomas, V.I. US Naval Med Bull. 1918;12:615–623. [Google Scholar]

- 39.King WW. The epidemic of dengue in the Porto Rico epidemic of 1915. New Orleans Med Surg J. 1917;69:564–571. [Google Scholar]

- 40.King WW. The clinical types of dengue in the Porto Rico epidemic of 1915. New Orleans Med Surg J. 1917;69:572–589. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mariano F. A dengue. Considerações a respeito de sua incursão no Rio Grande do Sul, em 1916. Arch Bras Med. 1916;8:271–277. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaudino NM. Dengue. Rev Sanid Milit Argent. 1916;15:617–627. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levy MD. Dengue: observations on a recent epidemic. Med Rec. 1920;97:1040–1042. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rice L. Dengue fever: preliminary report of an epidemic at Galveston. Texas J Med. 1922;18:217–218. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rice L. A clinical report of the Galveston epidemic in 1922. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1923;3:73–90. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scott LC. Dengue fever in Louisiana. JAMA. 1923;80:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myers WH. The epidemic of dengue fever in Savannah in 1922. J Med Assoc Ga. 1923;12:318–321. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pedro A. The dengue Nichteroy. Brazil Medico. 1923;37:173–177. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mac Donell GN. The dengue epidemic in Miami. J Fla Med Assoc. 1935;21:392–395. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffitts THD. Dengue in Florida, 1934, and its significance. J Fla Med Assoc. 1935;21:395–397. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prevalence of disease: United States: reports from states for week ended November 29, 1941. Public Health Rep. 1941;56:2350–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fairchild LM. Dengue-like fever on the Isthmus of Panama. Amer J Trop Med. 1945;25:397–401. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1945.s1-25.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosen L. Observations on the epidemiology of dengue in Panama. Am J Hyg. 1958;68:45–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pittaluga G. Sobre un brote de dengue en la Habana. Rev Med Trop y Parasitol Bact Clin y Lab. 1945;11:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dias-Rivera RS. A bizarre type of seven day fever clinically indistinguishable from dengue. Bol Asoc Med P R. 1946;38:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dominici SA. Acerca de la epidemia actual de dengue en Caracas. Gac Med Caracas. 1946;7:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabin AB, Schlesinger RW. Production of immunity to dengue with virus modified by propagation in mice. Science. 1945;101:640–642. doi: 10.1126/science.101.2634.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hammon WM, Rudnick A, Sather GE. Viruses associated with epidemic hemorrhagic fevers of the Philippines and Thailand. Science. 1960;131:1102–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.131.3407.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hotta S, Kimura R. Experimental studies on dengue I. Isolation, identification and modification of the virus. J Infect Dis. 1952;90:1–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/90.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuno G. Emergence of the Severe Syndrome and mortality associated with dengue and dengue-like illness: historical records (1890–1950) and their compatibility with current hypotheses on the shift of the disease manifestations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:186–201. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00052-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gorgas W. Sanitary conditions as encountered in Cuba and Panama and what is being done to render canal zone healthy. Med Rec. 1905:10. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Finlay C. El mosquito hipotéticamente considerado como agente de transmisión de la fiebre amarilla. An Acad Cien Med (Havana) 1881;18:147–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reed W, Carrol J, Agramonte A, Lazear JW. The etiology of yellow fever – preliminary note. Phila M J. 1900;6:790–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Severo OP. Eradication of the Aedes aegypti Mosquito from the Americas. 1955. http://jdc.jefferson.edu/yellow_fever_symposium/6 Yellow fever, a symposium in commemoration of Carlos Juan Finlay, 1955. Available at. Accessed June 2012.

- 65.Pan American Health Organization Pan American Sanitary Conference; 1942. Resolution CSP 11.R1 Sept. 1942 Pub. 198, 3–4. Available at. Accessed August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pan American Health Organization I Direct Council of the Pan American Health Organization. 1947. http://www.paho.org/English/GOV/CD/ftcd_1.htm#R1 Resolution CD1.R1. Continental Aedes aegypti eradication. Sept–Oct 1947 Pub. 247, 3. Available at. Accessed August 2011.

- 67.Pan American Health Organization The feasibility of eradicating Aedes aegypti in the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1997;1:381–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Anderson C, Downs W. Isolation of dengue virus from a human being in Trinidad. Science. 1956;124:224–225. doi: 10.1126/science.124.3214.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Griffiths BB, Grant LS, Minott OD, Belle EA. An epidemic of dengue-like illness in Jamaica—1963. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1968;17:584–589. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1968.17.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neff J, Morris L, González-Alcover R, Coleman PH, Lyss SB, Negron H. Dengue fever in a Puerto Rican community. Am J Epidemiol. 1967;86:162–184. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pan American Health Organization Epidemiological notes. Pan Am Health Organ Wkly Epidemiol Rep. 1965;37:116–121. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Briceno-Rossi AL. Recientes brotes de dengue en Venezuela. Gac Med Caracas. 1964;72:431–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ventura AK, Hewitt CM. Recovery of dengue-2 and dengue-3 viruses from man in Jamaica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19:712–715. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Centers for Disease Control Dengue – Puerto Rico, 1970. MMWR. 1971;20:74–75. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Likosky WH, Calisher CH, Michelson AL, Correa-Coronas R, Henderson BE, Feldman RA. An epidemiologic study of dengue type 2 in Puerto Rico, 1969. Am J Epidemiol. 1973;97:264–275. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jonkers AH, James F, Ali S. Dengue fever in the Caribbean 1968–69. West Indian Med J. 1969;18:126. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Llopis A, Travieso R, Addimandi V. Pan American Health Organization. Dengue in the Caribbean, 1977. Washington, DC: PAHO; 1979. Dengue in Venezuela; pp. 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Groot H. Dengue fever: present and potential problems in Colombia. Ind Trop Health. 1975;8:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morales A, Groot H, Russel PK, McCown JM. Recovery dengue-2 virus from Aedes aegypti in Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1973;22:785–787. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1973.22.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Groot H, Morales A, Romero M, Vidales H, Lesmes-Donaldson C, Márquez G, Escobar de Calvache D, Sáenz MO. Pan American Health Organization. Dengue in the Caribbean, 1977. Washington, DC: PAHO; 1979. Recent outbreaks of dengue in Colombia; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pan American Health Organization Dengue in the Caribbean, 1977. Sci Publ- Pan Am Health Organ. 1979;375:1–182. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gubler DJ, Meltzer M. Impact on the dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever on the developing world. Adv Virus Res. 1999;53:35–70. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kourí GP, Guzmán MG, Bravo JR, Triana C. Dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome: lessons from the Cuban epidemic, 1981. Bull World Health Organ. 1989;67:375–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guzmán MG, Kourí G, Morier L, Fernández A. A study of fatal hemorrhagic dengue cases in Cuba 1981. Bull PAHO. 1984;18:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guzmán MG. Treinta años después de la epidemia Cubana de dengue hemmorrágico en 1981. Rev Cubana Med Trop. 2012;64:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pinheiro FP, Corber SJ. Global situation of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever, and its emergence in the Americas. World Health Stat Q. 1997;50:161–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in the Americas. P R Health Sci J. 1987;6:107–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Loroño Pino MA, Farfán Ale JA, Rosado Paredes EP, Kuno G, Gubler DJ. Epidemic dengue-4 in the Yucatán, Mexico, 1984. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1993;35:449–455. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651993000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pan American Health Organization Dengue in the Americas: an update. Epidemiol Bull. 1993;14:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Osanai CH, Travassos da Rosa AP, Tang AT, do Amaral AS, Passos AD, Tauil PL. Outbreak of dengue in Boa Vista, Roraima: preliminary report. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1983;25:53–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schatzmayr HG, Nogueira RM, Travassos da Rosa AP. An outbreak of dengue virus at Rio de Janeiro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1986;81:245–246. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761986000200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nogueira RM, Schatzmayr HG, Miagostovich MP, Farias MF, Farias Filho JD. Virological study of a dengue type 1 epidemic at Rio de Janeiro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1989;83:219–225. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761988000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miagostovich MP, Nogueira RM, Cavalcanti SMB, Marzochi KBF, Schatzmayr HG. Dengue epidemic in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: virological and epidemiological aspects. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1993;35:149–154. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651993000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moraes LTF. Dengue in Brazil: past, present and future perspective. Dengue Bull. 2003;27:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Siqueira JB, Turchi Martelli CM, Coelho EG, da Rocha Simplicio AC, Hatch DL. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever, Brazil, 1981–2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:48–53. doi: 10.3201/eid1101.031091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pan American Health Organization Dengue hemorrhagic fever in Venezuela. Epidemiol Bull. 1990;11:7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lewis JA, Chang GJ, Lanciotti RS, Kinney RM, Mayer LW, Trent DW. Phylogenetic relationships of dengue-2. Virology. 1993;197:216–224. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rico-Hesse R, Harrison L, Salas R, Tovar D, Nisalak A, Ramos C, Boshell J, de Mesa M, Nogueira R, Travassos de Rosa A. Origins of dengue type 2 viruses associated with increased pathogenicity in the Americas. Virology. 1997;230:244–251. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nogueira RMR, Miagostovich MP, Lampe E, Souza RW, Zagne SMO, Schatzmayr HG. Dengue epidemic in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1990–1: co-circulation of dengue 1 and dengue 2 serotypes. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;11:163–170. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800056788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nogueira RM, Miagostovich MP, Lampe E, Schatzmayr HG. Isolation of dengue virus type 2 in Rio de Janeiro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1990;85:253. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761990000200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vasconcelos PF, de Menezes DB, Melo LP, Pessoa P, Rodrigues SG, Travassos da Rosa E, Timbó MJ, Coelho CB, Montenegro F, Travassos da Rosa J, Andrade F, Travassos da Rosa A. A large epidemic of dengue fever with dengue hemorrhagic cases in Ceará State, Brazil, 1994. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1995;37:253–255. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651995000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vasconcelos PF, Travassos da Rosa ES, Travassos da Rosa JF, Freiras RB, Rodrigues SG, Travassos da Rosa AP. Epidemia de febre clássica de dengue causada pelo sorotipe 2 em Araguaina, Tocantins, Brasil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1993;35:141–148. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651993000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nogueira RM, Zagne SM, Martins IS. Dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS) caused by serotype 2 in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1991;86:69–274. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761991000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nogueira RM, Miagostovich MP, Shcatzmayr HG, Moraes GC, Cardoso MA, Ferreira J, Cerqueira V, Pereira M. Dengue type 2 outbreak in the south of the state of Bahia, Brazil: laboratorial and epidemiological studies. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1995;37:507–510. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651995000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Watts DM, Porter KR, Putvatana P, Vasquez B, Calampa C, Hayes CG, Halstead SB. Failure of secondary infection with American genotype dengue 2 to cause dengue hemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 1999;354:1431–1434. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guzmán MG, Vázquez S, Martínez E, Alvarez M, Rodríguez R, Kourí G, de los Reyes J, Acevedo F. Dengue in Nicaragua, 1994: reintroduction of serotype 3 in the Americas. Pan Am J Publ Health. 1997;1:194–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Dengue type 3 infection – Nicaragua and Panama, October–November 1994. MMWR. 1995;44:21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Figueroa R, Ramos C. Dengue virus serotype 3 circulation in endemic countries and its reappearance in America. Arch Med Res. 2000;31:429–430. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(00)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pan American Health Organization Re-emergence of dengue in the Americas. Epidemiol Bull. 1997;18:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nogueira RM, Miagostovich MP, Filippis AM, Pereira MA, Schatzmayr HG. Dengue virus type 3 in Rio de Janeiro Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:925–926. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000700007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Uzcategui NY, Comach G, Camacho D, Salcedo M, Cabello de Quintana M, Jiménez M, Sierra G, Uzcategui RC, James WS, Turner S, Holmes EC, Gould EA. Molecular epidemiology of dengue virus type 3 in Venezuela. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1569–1575. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ocazionez RE, Cortes FM, Villar LA, Gómez SY. Temporal distribution of dengue virus serotypes in Colombian endemic area and dengue incidence. Re-introduction of dengue-3 associated to mild febrile illness and primary infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:725–731. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.XXXIX Directing Council of the Pan American Health Organization Resolution CD39.R11. 1996. http://www.paho.org/english/gov/cd/ftcd_39.htm Available at. Accessed August 2011.

- 114.Guzmán MG, Kourí G, Valdes L, Bravo J, Alvarez M, Vázques S, Delgado I, Halstead SB. Epidemiologic studies on dengue in Santiago de Cuba, 1997. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:793–799. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.9.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Avilés G, Rangeon G, Baroni P, Paz V, Monteros M, Sartini JL, Enría D. Epidemia por virus dengue-2 en Salta, Argentina, 1988. Medicina (B Aires) 2000;60:875–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Masuh H. Re-emergence of dengue in Argentina: historical development and future challenges. Dengue Bull. 2008;32:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Regato M, Recaray R, Moratorio G, de Mora D, Garcia-Aguirre L, González M, Mosquera C, Alava A, Fajardo A, Alvarez M, D'Andrea L, Dubra A, Martínez M, Kan B, Cristina J. Phylogenetic analysis of the NS5 gene of dengue virus isolated in Ecuador. Virus Res. 2008;132:197–200. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social . History of Dengue in Paraguay. 2012. http://dengue.mspbs.gov.py/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=86&Itemid=135 Available at. Accessed June 14, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Vargas MC, Osores FP, Suarez LO, Soto LA, Pardo KR. Dengue Clásico y hemorrágico: una enfermedad reemergente y emergente en el Perú. Rev Med Hered. 2005;16:120–140. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ministro de Salud del Perú, Oficina General de Epidemiología (Boletín Epidemiológico Semana del 12 al 18 de Diciembre).2004;13:1. http://www.dge.gob.pe/boletines/2004/50.pdf Available at. Accessed June 11, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nogueira RM, Shcatzmayr HG, de Filippis AM, dos Santos FB, da Cunha RV, Coelho JO, de Souza LJ, Guimaraes FR, de Araújo ES, De Simone TS, Baran M, Teixeira G, Jr, Miagostovich MP. Dengue type 3, Brazil 2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1376–1381. doi: 10.3201/eid1109.041043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Melo PR, Reis EA, Ciuffo IA, Góes M, Blanton MR, Reis MG. The dynamics of dengue virus serotype 3 introduction and dispersion in the state of Bahia, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:905–912. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007000800003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cordeiro MT, Schatzmayr HG, Nogueira RM, Oliveira VF, Melo WT, Carvalho EF. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in the State of Pernambuco, 1995–2006. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40:605–611. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822007000600001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.González I, Sáenz E. La confirmación de dengue por laboratorio en Costa Rica 1993–2006. Resultados y consideraciones generales. Boletín INCIENSA (Instituto Costarricense de Investigación y Enseñanza en Nutrición y Salud) 2007;19:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde Dengue Epidemic Report January to December 2007. 2007. http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/boletim_dengue_010208.pdf Available at. Accessed August 2011.

- 126.Ministério de Saúde, Secretaría de Vigilância em Saúde Dengue Epidemic Report January to November, 2008. 2008. http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/boletim_dengue_janeiro_novembro.pdf Available at. Accessed August 2011.

- 127.Cavalcanti LP, Vilar D, Souza-Santos R, Teixeira MG. Change in age pattern of persons with dengue, northeastern Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:132–134. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.100321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Seijo A. Dengue 2009: chronology of an epidemic (comments) Arch Argent Pediatr. 2011;107:387–389. doi: 10.1590/S0325-00752009000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vázquez-Pichardo M, Rosales-Jiménez C, Núñez-León A, Rivera-Osorio P, De la Cruz-Hernández S, Ruiz-López A, González-Mateos A, López-Martínez I, Rodríguez-Martínez JC, López-Gatell H, Alpuche-Almeida C. Serotipos de dengue en México durante 2009 y 2010. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2011;68:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Secretaría de Salud de México, Centro Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica y Control de Enfermedades (CENAVECE) Dengue: Panorama 2009. 2012. http://www.dgepi.salud.gob.mx/2010/plantilla/intd_dengue.html Available at. Accessed June 2012.

- 131.Gutiérrez G, Standish K, Narváez F, Pérez MA, Saborio S, Elizondo D, Ortega O, Núñez A, Kuan G, Balmaseda A, Harris E. Unusual dengue virus 3 epidemic in Nicaragua, 2009. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Locally acquired dengue – Key West, Florida, 2009–2010. MMWR. 2010;59:577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Figueiredo RM, Naveca FG, Bastos MS, Melo MM, Viana SS, Mourão MP, Alves Costa CA, Farias IP. Dengue virus type 4, Manaus, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:667–669. doi: 10.3201/eid1404.071185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Secretaría de Salud de Honduras, Dirección General de Vigilancia de la Salud 2010. (Boletin de Información Semanal sobre Dengue, Boletín 25 Semana Epidemiológica 52).http://www.salud.gob.hn/documentos/dgvs/Boletines%20Dengue/BOLETIN%20DENGUE%20No%2025.pdf Available at. Accessed May 2012.

- 135.Pan American Health Organization Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever; 43rd Directing Council, 53rd Session of the Regional Committee; Washington, DC. September 24–28, 2001; 2001. Resolution CD43.R4. Available at. Accessed August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 136.San Martín JL, Brathwaite-Dick O. Integrated strategy for dengue prevention and control in the region of the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;21:55–63. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892007000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.PAHO Dengue; Board of Directors. Regional Committee Meeting; Washington, DC. September 2003; 2003. Resolution CD44.R9. Available at. Accessed August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Pan American Health Organization Prevention and Control of Dengue in the Américas; Pan American Sanitary Conference; October 1–5, 2007.2007. Resolution CSP27.R15. [Google Scholar]