Abstract

Coordinated responses between the nucleus and mitochondria are essential for maintenance of homeostasis. For over 15 years, pools of nuclear transcription factors (TFs), such as p53 and nuclear hormone receptors, have been observed in the mitochondria. The contribution of the mitochondrial pool of these TFs to their well-defined biological actions is in some cases clear and in others not well understood. Recently, a small mitochondrial pool of the TF signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 3 (STAT3) was shown to modulate the activity of the electron transport chain. The mitochondrial function of STAT3 encompasses both its biological actions in the heart as well as its oncogenic effects. This review highlights advances in our understanding of how mitochondrial pools of nuclear TFs may influence the function of this organelle.

Keywords: nuclear transcription factors, mitochondrial function, apoptosis, STAT3

Nuclear Transcription Factors in the Mitochondria

Several reports have shown that pools of nuclear transcription factors with well-characterized functions in the nucleus are also present in the mitochondria (mitoTFs) [1–11]. MitoTFs comprise those of the nuclear hormone receptor family as well as transcription factors (e.g. p53, NF-κB and the STATs) that are activated downstream of growth hormones and cytokines binding to cell surface receptors. The mitochondrial function of nuclear hormone receptors has been recently reviewed [4, 6] and will not be discussed here. Rather, we will summarize our understanding of the actions of mitoTFs whose activities are mediated by hormones and cytokines that bind cell surface receptors.

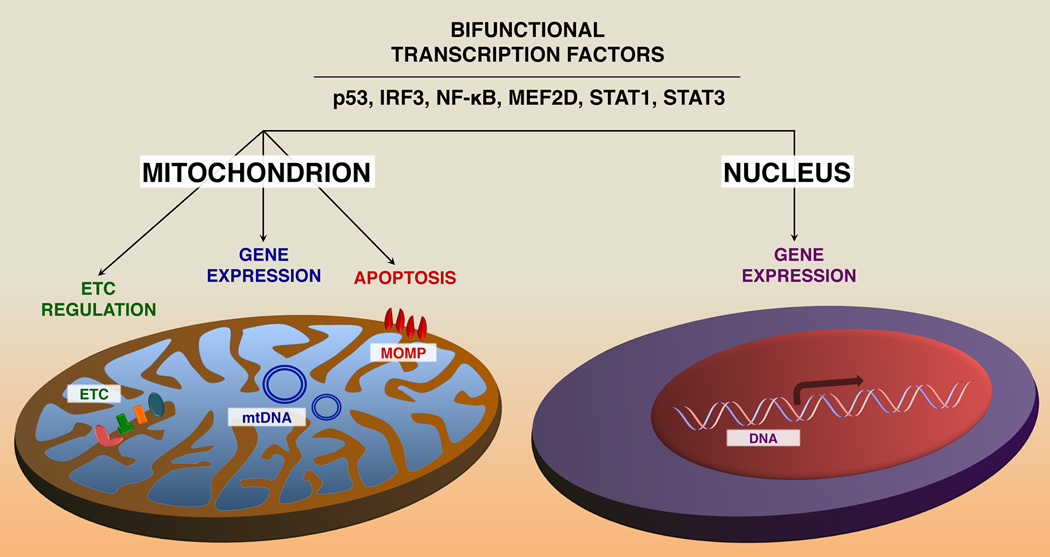

In general, the fraction of TFs in the mitochondria is very small compared to the levels in the cytosol or nucleus (5–10%). The potential functional effects of mitoTFs are varied and include apoptosis, respiration and mitochondrial gene expression (Figure 1). Interestingly, most of the transcription factors that reside in the mitochondria (including NF-κB, p53, CREB and MEF2D) are reported to regulate mitochondrial respiration or biogenesis [7, 12–15]. Often, defects in the function or expression of these mitoTFs result in altered susceptibility to the opening of the mitochondrial membrane transition pore (MMTP) and/or increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), presumably through electron leakage from complexes I and III of the ETC.

Figure 1. Nuclear TFs that play distinct roles in the mitochondria.

In the nucleus, TFs regulate gene expression, whereas in the mitochondria, they directly affect activity of the ETC (e.g. STAT3 [9]), interact with the apoptotic machinery (e.g. p53 [70], IRF3 [22]), and modulate expression of mtRNAs (e.g. CREB [7], NF-κB [5], MEF2D [8] and STAT1). ETC, electron transport chain; mtRNA, mitochondrial RNA; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; MOMP, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization.

The biological effects of mitoTFs are likely to be both immediate and long- term, whereas their actions in the nucleus are predominantly long-term (hours to days). Interestingly, in p53−/− murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) activation of NF-κB is enhanced and glycolysis is increased [16], suggesting that these TFs can regulate mitochondrial function. However, there was no attempt to examine whether the actions of p53 were mediated by its localization in the mitochondria or by nuclear gene expression.

Due to the small amount of these mitoTFs, however, their role in mitochondrial function is controversial. One of the major hurdles in the dissection of mitoTF function is the design of experimental models that allow separation of their mitochondrial actions from their nuclear function. For example, disrupted expression of STAT3 in the heart results in cardiomyopathy and decreased electron transport chain (ETC) activity [17–19]. However, it remains unclear what unique contributions the mitochondrial versus nuclear STAT3 make to maintain cardiac homeostasis. In contrast, it is clear that the ability of Ras to transform STAT3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) depends on STAT3 expression in the mitochondria without any requirement for its nuclear presence [3]. These results, as well as extensive studies of the role of mitochondria-localized p53 discussed further below, are examples where the actions of a TF in the mitochondria contribute to its physiological functions.

There is also limited information concerning the mechanisms by which TFs are transported into the mitochondria; for the most part they do not contain defined mitochondrial targeting sequences. Mitochondrial heat shock proteins 70 (mtHSP70) or 90 (mtHSP90) appear to be involved in the transport of several mitoTFs [5, 8, 20, 21] and additional mechanisms of mitochondrial translocation exist for some of the mitoTFs (Table 1). Once transported, the mitoTFs can be divided into those that are localized within the mitochondria (e.g. STAT3, NF-κB, CREB and MEF2D) and those that are associated with the outer mitochondrial membrane (e.g. p53 and IRF3).

Table 1.

Mechanisms of mitochondrial translocation and functions of the nuclear TFs.

| Transcription factor (TF) |

Function in the mitochondria |

Import into the mitochondria |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| p53 | - Binds to Bcl-2 family members and induces apoptosis - Inactivates MnSOD |

mono-ubiquitination, mtHSP60 and mtHSP70 | [23, 32, 70] |

| IRF3 | - Interacts with Bax | TOM70/HSP90 | [20, 22] |

| CREB | - Increases expression of mtRNAs and complex I activity | mtHSP70 | [7, 11] |

| NF-κB | - Inhibits mtRNA expression and mitochondrial respiration | mtHSP70 | [2, 5] |

| MEF2D | - Regulates expression of ND6 and complex I activity | N-terminal domain of MEF2D and mtHSP70 | [8] |

| STAT3 | - Facilitates the activities of complex I, II and V of the ETC - Attenuates ROS release from the ETC - Regulates MPTP |

GRIM-19, TOM/TIM/HSP90? | [3, 9, 19, 54, 71, 72] |

In this review, we provide an overview of how the mitochondrial fraction of these TFs contributes to their overall biological function, and discuss what is known about their mechanism of translocation and action within the mitochondria. We first discuss those mitoTFs that associate with the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), and then summarize what is known about the intramitochondrial TFs.

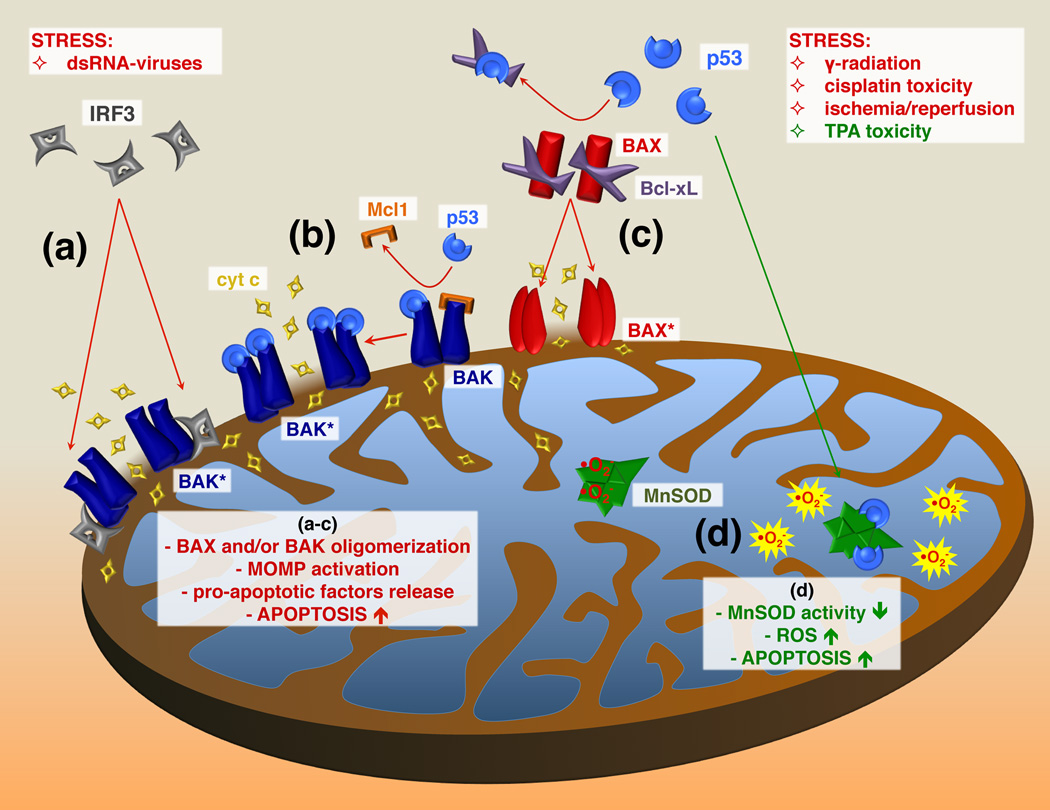

Transcription Factors Associated with the Outer Mitochondrial Membrane

p53 and IRF3 exert their pro-apoptotic effects within the mitochondria by regulating the actions of Bcl-2 family members [21, 22]. The association of p53 with the OMM is induced by a variety of stress signals. Stress-induced translocation of p53 to the mitochondria, i.e. gamma radiation, hypoxia and numerous other pro-apoptotic signals, involves mono-ubiquitination of a distinct cytoplasmic pool of p53 by the E3 ligase Mdm2. At the outer mitochondrial membrane, p53 is de-ubiquitinated, permitting it to interact with Bcl2 proteins and induce apoptosis [23]. RNA viruses or synthetic double-stranded RNA, poly(I:C), induce IRF3 translocation to the mitochondria [22]. Both p53- and IRF3-mediated apoptosis correlate with their translocation to the mitochondria. The pro-apoptotic actions of IRF3 do not require its binding to DNA and are independent of nuclear gene expression. Both IRF3 and p53 bind the Bcl-2 family proteins, resulting in activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway through facilitation of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) (Figure 2) [22, 23]. IRF3 binds BAK, which is a transmembrane protein localized at the OMM, leading to BAK oligomerization, MOMP formation, and release of pro-apoptotic factors from the intermembrane space into the cytosol (Figure 2a) [22]. Under stress conditions, formation of the pro-apoptotic p53-BAK complex is correlated with the disruption of the anti-apoptotic Mcl1-BAK complex (Figure 2b) [24]. p53 also interacts with another pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, BAX, which results in disruption of the anti-apoptotic sequestration of BAX by Bcl-xL (Figure 2c) [25]. Activated BAX is then inserted into the OMM, where it oligomerizes and facilitates MOMP formation.

Figure 2. p53 and IRF3 exhibit pro-apoptotic actions on the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Cellular stress triggers interaction of p53 and IRF3 with pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins. (a) Stress-induced translocation of IRF3 to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) leads to BAK oligomerization, MOMP formation and release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors into the cytosol, where they trigger apoptosis [22]. (b) Stress-induced formation of pro-apoptotic p53-BAK complex is correlated with the disruption of anti-apoptotic Mcl1-BAK interaction, which leads to activation of BAK and formation of MOMP [24]. (c) p53 interacts with pro-apoptotic BAX, and induces the conformational changes within BAX that lead to the disruption of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL-BAX complex [25]. Activated BAX can now be inserted into OMM, oligomerize and facilitate the MOMP formation. (d) The tumor promoter TPA, induces p53 translocation into the mitochondrial matrix, where it sequesters MnSOD [32]. This results in decreased superoxide scavenging activity of MnSOD, leading to ROS accumulation, increased mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of apoptosis. cyt c, cytochrome c; BAX, Bcl-2 associated X protein; BAK, Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer protein; Bcl-xL, B-cell lymphoma-extra large protein; Mcl1, induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein; BAK* and BAX*, activated BAK and BAX, respectively; TPA, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate.

Although it is unknown whether p53 and IRF3 influence each other’s actions in the mitochondria, IRF3 potentiates the growth inhibitory actions of p53 [26]. The fact that similar types of stress induce both IRF3 and p53 translocation to the mitochondria suggests the possibility of cross talk between these mitoTFs.

p53 has diverse actions within the cell and the mitochondrial fraction contributes to several of these. Radiation of mice stimulates accumulation of p53 in the mitochondria in radiation-sensitive tissues, such as testis and spleen, but not in radiation-resistant organs, such as liver and kidney [21]. Pifithrin-µ (PFTµ), which selectively prevents p53 accumulation in the mitochondria but has no effect on nuclear p53, inhibits gamma radiation-induced apoptosis of thymocytes and rescues irradiated mice from bone marrow failure [27]. PFTµ also reduces cisplatin-induced hepatocyte apoptosis [28]. These results suggest that mitochondrial p53 contributes significantly to the pathophysiology in response to these insults.

In addition to its influence on Bcl-2 proteins on the OMM, p53 is also located in other compartments of the mitochondria [21]. p53 binds to mtHSP70 and mtHSP60 in the mitochondrial matrix [29–31]. p53 translocates into the mitochondria after treatment of epidermal cells with the tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) [32]. Inside the mitochondrial matrix, p53 sequesters manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), a major mitochondrial antioxidative enzyme, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and initiation of apoptosis [32] (Figure 2d). It is not clear whether the appearance of p53 within the mitochondria matrix is dependent or independent of its presence in the OMM because localization of p53 within the mitochondrial matrix is seen after 1 hr of treatment of cells with TPA while translocation to the OMM occurs within minutes.

In addition to its well-described function as a component required for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) transcription, mitochondrial transcription factor A (mtTFA) selectively interacts with damaged mtDNA [33]. Moreover, intra-mitochondrial p53 forms a complex with the mtTFA, suggesting that it may also be involved in mtDNA repair [33]. However, many of these experiments used cell extracts and should be further strengthened by the use of in vivo models.

Intramitochondrial TFs That Regulate Mitochondrial Gene Expression and Respiration

Cyclic-AMP response element-binding protein (CREB), NF-κB, MEF2D and STATs are reported to reside within the intermembrane space, the inner membrane or the matrix [2, 3, 5, 7–9, 17–19]. In contrast to p53 and IRF3, these TFs exert their mitochondrial actions by regulating mitochondrial gene expression or the activity of the ETC. A number of experimental approaches, including cell fractionation, confocal and electron microscopy, and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIPs), have demonstrated that these TFs are indeed localized to the mitochondria [2, 3, 5, 7–9, 17–19]. Consequences of disrupting the expression of these mitoTFs suggest that they modulate mitochondrial performance. However, it has been much more difficult to directly link the presence of a mitoTF to altered mitochondrial function, such as ETC activity, largely due to the challenge of separating the distinct contributions of the mitochondrial pool of a given TF from its effects in the nucleus.

In the following, we summarize our present understanding of the actions of CREB, NF-κB, MEF2D and STATs in the mitochondria.

Cyclic-AMP Response Element-Binding Protein (CREB)

CREB is a critical mediator of cell survival and differentiation in response to a variety of stimuli. It is activated by kinases such as cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), extracellular-regulated kinases (ERKs) and calcium-activated calmodulin kinases (CaMKs) [34]. As seen with most mitoTFs, CREB does not contain a mitochondrial-localization sequence. Import of CREB into the mitochondria depends on mtHSP70, a chaperone that facilitates unfolding and transport of proteins across the mitochondrial inner membrane through interactions with proteins of the translocase of inner membrane (TIM) complex [7]. In vitro translocation studies indicate that CREB import requires also the translocase of outer membrane (TOM) complex and the mitochondrial membrane potential [35].

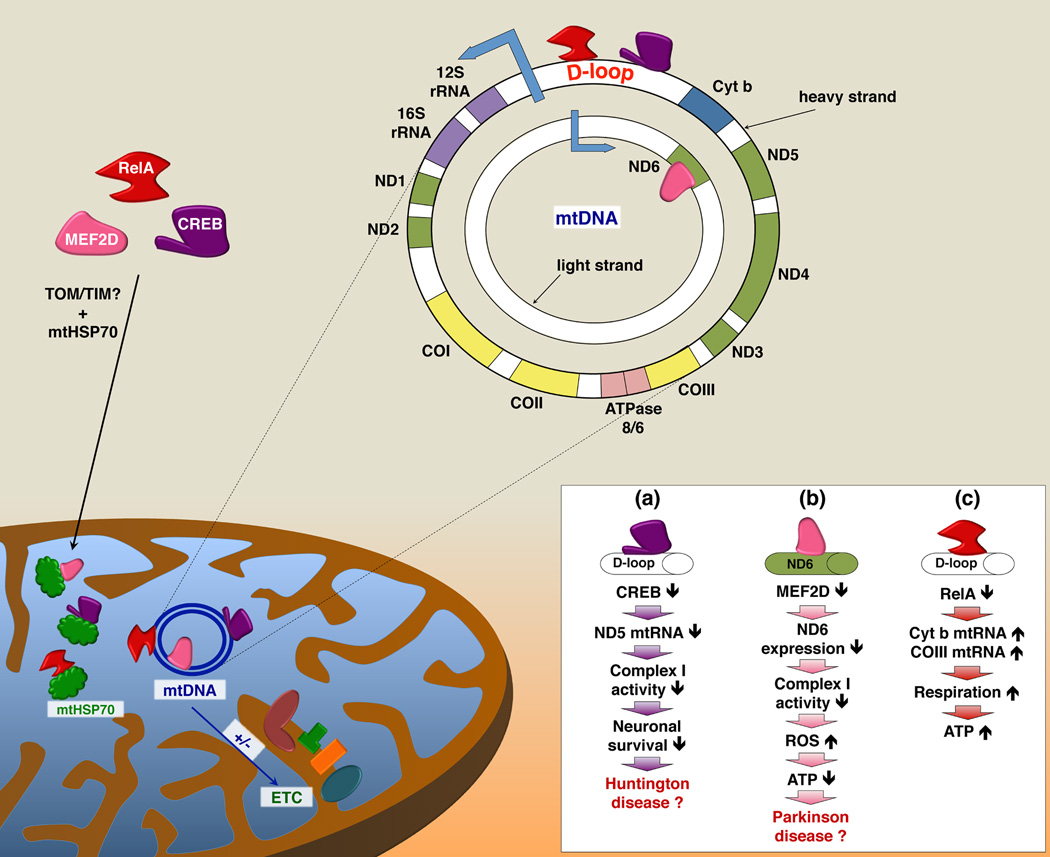

In neurons, CREB regulates mitochondrial gene expression [7]. ChIP assays demonstrate that CREB binds to the D-loop of mtDNA [7, 11, 36]. Elimination of CREB from mitochondria decreases expression of several mitochondria-encoded RNAs (mtRNAs) of complex I with a concomitant decrease in complex I activity [7] (see Figure 3a). Neurons expressing a dominant negative form of CREB targeted to the mitochondria are more susceptible to apoptosis when treated with 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP). Furthermore, the exposure to 3-NP induces symptoms of Huntington disease (HD) in both mice and humans [7, 37]. It has been suggested that the interaction of mutated huntingtin, the protein responsible for development of HD, with CREB leads to sequestration and inactivation of mitoCREB [7]. Therefore, mitoCREB may be an integral and direct participant in regulation of mitochondrial function, and contribute to the pathophysiology of HD.

Figure 3. CREB, MEF2D, and RelA are bi-organellar transcription factors.

In addition to their role in regulation of nuclear gene expression, CREB, MEF2D and RelA (member of the NF-κB family) are also present in the mitochondria where they bind to specific sequences in mtDNA. Disrupted binding of CREB (a) and MEF2D (b) to mtDNA results in downregulation of mtRNAs encoding subunits of complex I of the ETC, leading to decreased complex I activity, which affects cell survival and may play a role in pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases [7, 8]. RelA (c) represses mtRNA expression. Decreased binding of RelA to mtDNA results in augmented mtRNA levels of cyt b and COIII transcripts, increased mitochondrial respiration and ATP production [5]. cyt b, cytochrome b; CO, cytochrome c oxidase; ND, NADH dehydrogenase.

Myocyte Enhancer Factor-2D (MEF2D)

The myocyte-specific enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) family of TFs plays important roles in immune responses, muscle differentiation, carbohydrate metabolism, neuronal development and survival. For the past decade MEF2-related factors have been known to also regulate mitochondrial biogenesis [15]. A recent elegant study documented that MEF2D is indeed localized to the mitochondria [8]. Similar to CREB, MEF2D is transported into the mitochondria by a mtHSP70-dependent mechanism. MEF2D binds to a consensus site in the coding region of the mitochondrial ND6 gene, which is located on the light strand of mtDNA and encodes a component of complex I (Figure 3b). Using in vitro transcription assays, purified MEF2D increased transcription from the light strand promoter. MEF2D is required for expression of ND6, as disruption of MEF2D expression decreases complex I activity, increases production of ROS and decreases cellular ATP. Treatment of neuronal cells with rotenone, an inhibitor of complex I, selectively decreases the binding of MEF2D to the ND6 gene and decreases ND6 protein levels. Moreover, the treatment of cells with the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MMP+) decreases neuronal viability in a MEF2D-dependent manner, consistent with a loss of mitochondrial MEF2D and a decline in ND6 expression in brains from MMP+-treated mice. Intriguingly, ND6 and mitochondrial MEF2D are decreased in post-mortem brains of patients with Parkinson disease (PD). Taken together, these results strongly support an important role for mitochondrial MEF2D in the regulation of ATP production through modulation of ND6 transcription. As such, mitochondrial MEF2D may contribute to the pathogenesis of PD.

Nuclear Factor Kappa-B (NF-κB) Family of TFs

TFs of the NF-κB family are activated by multiple stimuli, resulting in the expression of genes that control inflammation, cancer, cell metabolism and development. Several members of the NF-κB family (p50/NF-κB1, p65 [RelA]) as well as the Inhibitor of NF-κB (IκBα) are localized in the mitochondrial matrix and intermembrane space.

NF-κB was reported to interact with the mitochondrial ATP/ADP translocator-1 (ANT1) [1]. ANT1 recruits the IκBα/NF-κB complex into the mitochondria, which correlates with decreased NF-κB binding activity in the nucleus and decreased expression of NF-κB-stimulated anti-apoptotic genes, such as Bcl-xL and c-IAP2 [38]. These studies, however, rely on overexpression of ANT1, thus their physiological significance remains to be verified. It is also unclear whether the apoptotic effects are directly attributable to NF-κB in the mitochondria as opposed to its nuclear fraction.

Other studies indicate that NF-κB (RelA) in the mitochondria inhibits expression of mtRNAs encoding cytochrome c oxidase III (COXIII) and cytochrome b (cyt b) (Figure 3c), possibly by binding to the D-loop of mtDNA [2, 5]. RelA binding to the mtDNA is increased in a late passage number U-2 OS osteosarcoma cells. Late passage U-2 OS cells also have a small increase in the amount of RelA in the mitochondria.

NF-κB translocation into the mitochondria likely involves its interaction with mtHSP70, because disruption of mtHSP70 expression decreases the levels of RelA in mitochondria [5, 39–41]. T505A-mutated RelA, which does not accumulate in the mitochondria, displays compromised binding to mtHSP70. Interestingly, the level of RelA in the mitochondria is decreased after overexpression of p53 [5]. Moreover, expression of p53 reverses the inhibitory effects of RelA on mtRNA expression, suggesting crosstalk between these TFs in the mitochondria. It has been proposed that the actions of RelA and p53 in regulation of respiration influence the switch from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis observed in cancer cells [5]. The data supporting this hypothesis are intriguing, but limited. Questions remain as to why the effects on metabolism are cell passage-dependent. The observed effects of RelA on respiration and mitochondrial gene expression would be strengthened by correlations with cell transformation.

Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (STATs)

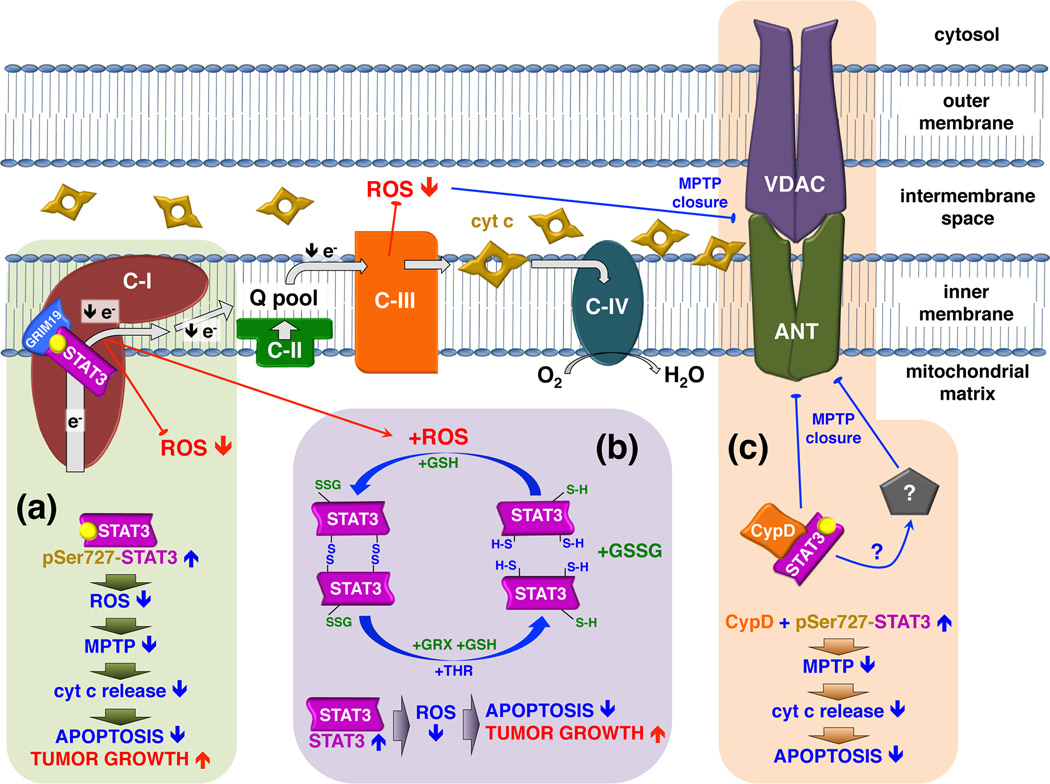

STATs and the JAK tyrosine kinases that activate them have emerged as critical regulators of numerous fundamental biological processes governing inflammation, obesity, cardiovascular disease and cancer. In addition to its well-described actions in the nucleus, a pool of STAT3 has been identified in the mitochondria (mitoSTAT3) [9]. The rationale for examining whether STAT3 might be in mitochondria came from observations that the tumor suppressor GRIM-19, which is a component of complex I of the ETC, binds to STAT3 [42–45]. Recently, it was reported that translocation of STAT3 into the mitochondria is regulated by GRIM-19 [46]. MitoSTAT3 modulates activity of the ETC [9] as evidenced by decreased activities of complexes I and II in Stat3−/− murine hearts [9]. In addition to controlling respiration in cardiomyocytes, mitoSTAT3 also contributes an important role in Ras-induced transformation of Stat3−/− MEFs [3]. Ras transformation of Stat3−/− MEFs is restored when STAT3 is reintroduced into the mitochondria of these cells. In contrast to its actions in the nucleus, STAT3 in the mitochondria requires serine 727 (Ser727) but not tyrosine 705 (Tyr705) phosphorylation to regulate respiration and Ras transformation. Furthermore, point mutations that abrogate SH2 or DNA-binding domain functions of STAT3, both of which are required for it to function as a nuclear TF, still allow this protein to restore Ras transformation.

By contrast, another lab has not detected STAT3 in heart mitochondria [47]. The reasons for this discrepancy are not clear, but might be due to the fact that there is not a 1:1 stoichiometry between STAT3 and other components of complex I in the mitochondria. The lack of a 1:1 ratio with various components of the ETC has been observed for other proteins known to influence respiration, such as SDH5, which is required for activity of complex II and is present in sub-stoichiometric amounts with complex II [48] (Jared Rutter, personal communication).

There have been several follow-up studies examining the role of mitoSTAT3 in cardiac function. It is well known that STAT3 protects from ischemic heart injury [17, 49, 50]. Transgenic mice that express a mitochondrial-targeted form of STAT3 with a mutation in its DNA binding domain (MLS-STAT3E) in the heart exhibit a partial blockade of the ETC [19, 51]. Expression of the transgene increases tolerance of cardiac mitochondria to ischemia by preserving complex I activity and decreasing ROS production [19] (Figure 4a). Another study that uses a porcine model of ischemia-reperfusion, which is more relevant to human disease, shows that mitoSTAT3 contributes to cardioprotection against ischemia [52]. Consistent with these observations, Ser727 phosphorylation of STAT3 in the mitochondria is associated with elevated expression of heat shock protein 22, which is important for protection of myocardium [53]. Furthermore, ADP-stimulated respiration is decreased in hearts of Stat3−/− mice as well as in rat cardiomyocytes treated with the STAT3 inhibitor Stattic [54]. Moreover, Stat3−/− mitochondria incubated with Stattic are more sensitive to calcium-induced opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP). Interestingly, cyclophilin D (CypD), a known functional component of the MPTP, associates with STAT3. It is thus possible that mitoSTAT3 exerts its actions by preventing opening of the MPTP and, therefore, participates in inhibition of apoptosis through blockade of MPTP-mediated cytochrome c release (Figure 4c).

Figure 4. Mitochondrial STAT3 regulates the activity of the ETC resulting in ROS attenuation and increased cell survival.

The actions of mitochondrial STAT3 on complex I participate in protection against ischemia and reperfusion injury. In other circumstances, the anti-apoptotic functions of mitochondrial STAT3 are detrimental and facilitate tumor growth. (a) Increased amounts of Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 in the mitochondria during stress attenuates electron transfer through complex I, possibly through interactions with GRIM-19. This in turn leads to decreased ROS release that is dependent on complex I-to-III electron flow [19]. Attenuated ROS concentration maintains the MPTP in a closed conformation, preventing mitochondrial swelling and mitochondrial membrane permeation. (b) In the presence of increased ROS, STAT3 can be oxidized to form multimers [56]. Alternatively oxidative modification of cysteine residues of STAT3 by S-glutathionylation may occur [57]. Oxidation of cysteines can serve as an electron sink that leads to diminished ROS accumulation, protection of mitochondrial integrity and decreased apoptosis. Reduction of oxidized STAT3 in the mitochondria may occur by the reactions catalyzed by glutaredoxins and thioredoxins. (c) Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 can interact with cyclophilin D, a protein that augments calcium sensitivity to MPTP opening [54]. Increased amounts of mitochondrial STAT3 during stress may sequester cyclophilin D, preventing it from binding to MPTP component(s) and triggering the MPTP opening. Alternatively, the STAT3-CypD complex may interact with an unknown target, which in turn inhibits MPTP opening. MPTP opening leads to mitochondrial swelling, disruption of both mitochondrial membranes, release of pro-apoptotic factors into the cytosol and the subsequent activation of apoptosis. C-I, C-II, C-III, C-IV, complex I, II, III and IV, respectively; Q, ubiquinone; VDAC, voltage-dependent anion channel; ANT, adenine nucleotide translocase; GRX, glutaredoxin; TRX, thioredoxin; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, glutathione disulfide; CypD, cyclophilin D.

STAT3 can be oxidized by peroxide to form multimers [55, 56]. Additionally, STAT3 S-glutathionylation inhibits its function as a transcription factor [57]. This has led to the notion that under conditions of stress, when ROS is elevated in the mitochondria secondarily to electron leak of complex I, oxidation of cysteines in STAT3 may serve as electron scavengers, resulting in diminished ROS levels and protection of complex I (Figure 4b). Consistent with this model, hearts subjected to ischemia display increased accumulation of STAT3 in the mitochondria, possibly leading to reduced ROS accumulation and protection of cells from apoptosis [19]. As there are limited amounts of mitoSTAT3, reduction of oxidized STAT3 would have to occur rapidly either in the mitochondria or in the cytosol, mediated for instance by thioredoxins (TRXs) (protein disulfides) and glutaredoxins (GRXs) (S-glutathionylation). Interestingly, some isoforms of thioredoxins (TRX2) and glutaredoxins (GRX1, GRX2 and GRX5) are present in the mitochondria where they participate in oxidative stress defense mechanisms and redox processes [58–61]. ROS accumulation in 4T1 breast cancer cells appears decreased when Ser727 of mitoSTAT3 is mutated to the phospho-mimic aspartic acid, but is increased when Ser727 is mutated to an alanine (unpublished results, Qifang Zhang, Vasily A. Yakovlev, Adly Yacoub, Karol Szczepanek, Kristoffer Valerie, and Andrew C. Larner). Although this model of STAT3 function in the mitochondria has no precedence among other TFs, the signaling adaptor p66Shc and the GTPase Rac 1 localize in the mitochondria where they directly modulate the generation of ROS [62, 63]. It is therefore conceivable that other proteins that are modified by ROS, such as STAT3, can function by similar mechanisms to modulate levels of mitochondrial ROS.

Apart from cardiomyocytes, the role of mitoSTAT3 in respiration has also been studied in astrocytes and in nerve growth factor (NGF)-induced neurite outgrowth [64]. Consistent with previous observations [3], selective inhibition of complexes I or III of the ETC affects cell survival in a mitoSTAT3-dependent manner. Astrocytes are also more sensitive to these inhibitors with respect to ROS production, maintenance of mitochondrial membrane potential and cell viability [65]. In contrast to cardiomyocytes and MEFs, Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 is not constitutively present in the mitochondria of primary neurons [64]. However, NGF increases Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 in the mitochondria, but not in the nucleus [64]. NGF does not alter the amount of total mitoSTAT3, suggesting that the kinase responsible for phosphorylating Ser727 is also present in the mitochondria. Interestingly, Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 co-localizes and interacts with GRIM-19 [45]. Expression of a mitochondria-targeted STAT3 (MLS-STAT3) enhances NGF-induced neurite growth, while MLS-STAT3 with Ser727 mutated to alanine inhibits NGF-induced neurite outgrowth [64]. These results highlight the broad involvement of Ser727 phosphorylation of STAT3 in a variety of its actions originally assumed to be mediated by its effects as a nuclear TF.

In addition to STAT3, two other STAT family members, STAT1 and STAT5, have also been observed in the mitochondria [54, 66]. STAT5 is important for the growth and development of hematopoietic cells. Treatment of cells with IL-2 induces the translocation of STAT5 into the mitochondria, where it interacts with the E2 component of the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex [66]. Furthermore, STAT5 can bind to the D-loop regulatory region of mitochondrial DNA in vitro.

STAT1 contributes a central role in mediating the antiviral, antigrowth, and immune surveillance effects of interferons. It was reported 20 years ago that type I interferons inhibit the expression of mitochondria-encoded RNAs [67–69]. Recently, STAT1 was found in heart mitochondria, but no function has been ascribed to its mitochondrial presence [54]. STAT1 may also be in the mitochondria of several cell lines as well as murine heart, liver and spleen (unpublished results, Jennifer Sisler, Magdalena Szelag, Karol Szczepanek, Marta Derecka, and Andrew C. Larner). In addition to its well-known effects to stimulate nuclear gene transcription, STAT1 inhibits the baseline expression of RNAs transcribed in the mitochondria (Figure 3d) as well as the nuclear-encoded RNAs that encode components of the ETC. Treatment of mice with IFNβ further decreases the expression of mtRNAs and nuclear-encoded mRNAs of the ETC [67–69]. Importantly, Stat1−/− tissues show increased mitochondria biogenesis compared to Stat1+/+ cells, suggesting that this transcriptional suppression plays a vital role in regulation of energy balance.

Concluding remarks

Evidence continues to accumulate that endorses the bifunctional role of many TFs in the control of both nuclear gene expression and mitochondrial function. It may be that many other nuclear TFs also coordinate nuclear and mitochondrial responses to maintain homeostasis. Intuitively, the existence of proteins that regulate both nuclear and mitochondrial responses to stress makes sense, because both of these organelles are critical for regulation of cell survival and growth. Various mechanisms have been described by which nuclear TFs affect mitochondrial functions, including activation or inhibition of mtRNA expression (e.g. CREB, NF-κB, MEF2D and STAT1), interaction with the apoptotic machinery (e.g. p53, IRF3) or direct alteration of the ETC activity (e.g. STAT3). Moreover, a primary or secondary target of the actions of these TFs in the mitochondria is the regulation of ROS accumulation.

The future challenges in this emerging field are to understand how the dual actions of these TFs in the nucleus and mitochondria are coordinately regulated, and to identify the contributions of the pool of mitochondria-localized TFs to the well-characterized roles for these proteins in cell physiology and pathology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by R01 AI059710-01, R21 AI088487 to ACL; the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veteran Affairs and the Pauley Heart Center of VCU to EJL.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Bottero V, et al. Ikappa b-alpha, the NF-kappa B inhibitory subunit, interacts with ANT, the mitochondrial ATP/ADP translocator. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:21317–21324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cogswell PC, et al. NF-kappa B and I kappa B alpha are found in the mitochondria. Evidence for regulation of mitochondrial gene expression by NF-kappa B. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:2963–2968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gough DJ, et al. Mitochondrial Stat3 Supports Ras-Dependent Cellular Transformation. Science. 2009;324:1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1171721. PMCID 148639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harper ME, Seifert EL. Thyroid effects on mitochondrial energetics. Thyroid. 2008;18:145–156. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson RF, et al. p53-dependent regulation of mitochondrial energy production by the RelA subunit of NF-kappaB. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5588–5597. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klinge CM. Estrogenic Control of Mitochondrial Function and Biogenesis. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008;105:1342–1351. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J, et al. Mitochondrial cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) mediates mitochondrial gene expression and neuronal survival. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:40398–40401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500140200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.She H, et al. Direct regulation of complex I by mitochondrial MEF2D is disrupted in a mouse model of Parkinson disease and in human patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:930–940. doi: 10.1172/JCI43871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wegrzyn J, et al. Function of mitochondrial Stat3 in cellular respiration. Science. 2009;323:793–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1164551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaseva AV, et al. The transcription-independent mitochondrial p53 program is a major contributor to nutlin-induced apoptosis in tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1711–1719. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryu H, et al. Antioxidants modulate mitochondrial PKA and increase CREB binding to D-loop DNA of the mitochondrial genome in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13915–13920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502878102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawachi S, et al. E-Selectin expression in a murine model of chronic colitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:547–552. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matoba S, et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mauro C, et al. NF-kappaB controls energy homeostasis and metabolic adaptation by upregulating mitochondrial respiration. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1272–1279. doi: 10.1038/ncb2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naya FJ, et al. Mitochondrial deficiency and cardiac sudden death in mice lacking the MEF2A transcription factor. Nat Med. 2002;8:1303–1309. doi: 10.1038/nm789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawauchi K, et al. p53 regulates glucose metabolism through an IKK-NF-kappaB pathway and inhibits cell transformation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:611–618. doi: 10.1038/ncb1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilfiker-Kleiner D, et al. A cathepsin D-cleaved 16 kDa form of prolactin mediates postpartum cardiomyopathy. Cell. 2007;128:589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacoby JJ, et al. Cardiomyocyte-restricted knockout of STAT3 results in higher sensitivity to inflammation, cardiac fibrosis, and heart failure with advanced age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12929–12934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134694100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szczepanek K, Chen Q, Derecka M, Salloum FN, Zhang Q, Szelag M, Cichy J, Kukreja RC, Dulak J, Lesnefsky EJ, Andrew CLarner. Mitochondrial-Targeted Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) Protects Against Ischemia-Induced Changes in the Electron Transport Chain and the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:29610–29620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.226209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu XY, et al. Tom70 mediates activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 on mitochondria. Cell Res. 2010;20:994–1011. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaseva AV, Moll UM. The mitochondrial p53 pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chattopadhyay S, et al. Viral apoptosis is induced by IRF-3-mediated activation of Bax. The EMBO journal. 2010;29:1762–1773. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchenko ND, et al. Monoubiquitylation promotes mitochondrial p53 translocation. The EMBO journal. 2007;26:923–934. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leu JI, et al. Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:443–450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chipuk JE, et al. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim TK, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 3 activates p53-dependent cell growth inhibition. Cancer Lett. 2006;242:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strom E, et al. Small-molecule inhibitor of p53 binding to mitochondria protects mice from gamma radiation. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:474–479. doi: 10.1038/nchembio809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leu JI, George DL. Hepatic IGFBP1 is a prosurvival factor that binds to BAK, protects the liver from apoptosis, and antagonizes the proapoptotic actions of p53 at mitochondria. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3095–3109. doi: 10.1101/gad.1567107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dumont P, et al. The codon 72 polymorphic variants of p53 have markedly different apoptotic potential. Nat Genet. 2003;33:357–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchenko ND, et al. Death signal-induced localization of p53 protein to mitochondria. A potential role in apoptotic signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:16202–16212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadhwa R, et al. Hsp70 family member, mot-2/mthsp70/GRP75, binds to the cytoplasmic sequestration domain of the p53 protein. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:246–253. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y, et al. p53 Translocation to Mitochondria Precedes Its Nuclear Translocation and Targets Mitochondrial Oxidative Defense Protein-Manganese Superoxide Dismutase. Cancer Research. 2005;65:3745–3750. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshida Y, et al. P53 physically interacts with mitochondrial transcription factor A and differentially regulates binding to damaged DNA. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3729–3734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altarejos JY, Montminy M. CREB and the CRTC co-activators: sensors for hormonal and metabolic signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:141–151. doi: 10.1038/nrm3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Rasmo D, et al. cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) is imported into mitochondria and promotes protein synthesis. FEBS J. 2009;276:4325–4333. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cammarota M, et al. Cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein in brain mitochondria. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2272–2277. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bogdanov MB, et al. Increased vulnerability to 3-nitropropionic acid in an animal model of Huntington's disease. J Neurochem. 1998;71:2642–2644. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71062642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zamora M, et al. Recruitment of NF-kappaB into mitochondria is involved in adenine nucleotide translocase 1 (ANT1)-induced apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:38415–38423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moro F, et al. Mitochondrial protein import: molecular basis of the ATP-dependent interaction of MtHsp70 with Tim44. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:6874–6880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voos W, Rottgers K. Molecular chaperones as essential mediators of mitochondrial biogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1592:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yaguchi T, et al. Involvement of mortalin in cellular senescence from the perspective of its mitochondrial import, chaperone, and oxidative stress management functions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:306–311. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fearnley IM, et al. GRIM-19, a cell death regulatory gene product, is a subunit of bovine mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:38345–38348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang G, et al. GRIM-19, a cell death regulatory protein, is essential for assembly and function of mitochondrial complex I. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8447–8456. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8447-8456.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lufei C, et al. GRIM-19, a death-regulatory gene product, suppresses Stat3 activity via functional interaction. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:1325–1335. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, et al. The cell death regulator GRIM-19 is an inhibitor of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9342–9347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633516100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shulga N, Pastorino JG. GRIM-19Mediated Translocation of STAT3 to Mitochondrial is Necessary for TNF Induced Necroptosis. Journal of Cell Science. 2012 doi: 10.1242/jcs.103093. (in press)., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 47.Phillips D, et al. Intrinsic protein kinase activity in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2515–2529. doi: 10.1021/bi101434x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hao HX, et al. SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science. 2009;325:1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.1175689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haghikia A, et al. STAT3 and cardiac remodeling. Heart Fail Rev. 2010;16:35–47. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hilfiker-Kleiner D, et al. Many good reasons to have STAT3 in the heart. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;107:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szczepanek K, et al. Cytoprotection by the modulation of mitochondrial electron transport chain: the emerging role of mitochondrial STAT3. Mitochondrion. 2012;12:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heusch G, et al. Mitochondrial STAT3 Activation and Cardioprotection by Ischemic Postconditioning in Pigs With Regional Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion. Circ Res. 2011;109:1302–1308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qiu H, et al. H11 kinase/heat shock protein 22 deletion impairs both nuclear and mitochondrial functions of STAT3 and accelerates the transition into heart failure on cardiac overload. Circulation. 2011;124:406–415. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.013847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boengler K, et al. Inhibition of permeability transition pore opening by mitochondrial STAT3 and its role in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:771–785. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li L, et al. Modulation of gene expression and tumor cell growth by redox modification of STAT3. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8222–8232. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaw PE. Could STAT3 provide a link between respiration and cell cycle progression? Cell Cycle. 2011;9:4294–4296. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie Y, et al. S-glutathionylation impairs signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation and signaling. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1122–1131. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanaka T, et al. Thioredoxin-2 (TRX-2) is an essential gene regulating mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. The EMBO journal. 2002;21:1695–1703. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beer SM, et al. Glutaredoxin 2 catalyzes the reversible oxidation and glutathionylation of mitochondrial membrane thiol proteins: implications for mitochondrial redox regulation and antioxidant DEFENSE. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:47939–47951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallogly MM, et al. Glutaredoxin regulates apoptosis in cardiomyocytes via NFkappaB targets Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL: implications for cardiac aging. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2010;12:1339–1353. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodriguez-Manzaneque MT, et al. Grx5 is a mitochondrial glutaredoxin required for the activity of iron/sulfur enzymes. Molecular biology of the cell. 2002;13:1109–1121. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giorgio M, et al. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell. 2005;122:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Osborn-Heaford HL, et al. Mitochondrial Rac1 GTPase Import and Electron Transfer from Cytochrome c Are Required for Pulmonary Fibrosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:3301–3312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou L, Too H-P. Mitochondrial Localized STAT3 Is Involved in NGF Induced Neurite Outgrowth. Plos. 2011;1:e21680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sarafian TA, et al. Disruption of astrocyte STAT3 signaling decreases mitochondrial function and increases oxidative stress in vitro. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chueh FY, et al. Mitochondrial translocation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) in leukemic T cells and cytokine-stimulated cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402:778–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lewis JA, et al. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Function by Interferon. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:13184–13190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lou J, et al. Supression of Mitochondrial mRNA Levels and Mitochondrial Function in Cells Responding to the Anticellular Action of Interferon. J. Interferon Res. 1994;14:33–40. doi: 10.1089/jir.1994.14.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shan B, et al. Interferon selectively inhibits the expression of mitochondrial genes: a novel pathway for interferon-mediated responses. EMBO Journal. 1990;9:4307–4314. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mihara M, et al. p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2003;11:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shah M, et al. Interactions of STAT3 with caveolin-1 and heat shock protein 90 in plasma membrane raft and cytosolic complexes. Preservation of cytokine signaling during fever. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:45662–45669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shulga N, Pastorino JG. GRIM-19 Mediated Translocation of STAT3 to Mitochondria is Necessary for TNF Induced Necroptosis. Journal of Cell Science. 2012 doi: 10.1242/jcs.103093. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]