Summary

Obscurin (also known as Unc-89 in Drosophila) is a large modular protein in the M-line of Drosophila muscles. Drosophila obscurin is similar to the nematode protein UNC-89. Four isoforms are found in the muscles of adult flies: two in the indirect flight muscle (IFM) and two in other muscles. A fifth isoform is found in the larva. The larger IFM isoform has all the domains that were predicted from the gene sequence. Obscurin is in the M-line throughout development of the embryo, larva and pupa. Using P-element mutant flies and RNAi knockdown flies, we have investigated the effect of decreased obscurin expression on the structure of the sarcomere. Embryos, larvae and pupae developed normally. In the pupa, however, the IFM was affected. Although the Z-disc was normal, the H-zone was misaligned. Adults were unable to fly and the structure of the IFM was irregular: M-lines were missing and H-zones misplaced or absent. Isolated thick filaments were asymmetrical, with bare zones that were shifted away from the middle of the filaments. In the sarcomere, the length and polarity of thin filaments depends on the symmetry of adjacent thick filaments; shifted bare zones resulted in abnormally long or short thin filaments. We conclude that obscurin in the IFM is necessary for the development of a symmetrical sarcomere in Drosophila IFM.

Key words: M-line, Obscurin, Unc-89, Thick filament, Drosophila, Muscle

Introduction

The sarcomeres of striated muscle are composed of parallel thick and thin filaments. Thin filaments from neighbouring sarcomeres are crosslinked in the Z-disc, and thick filaments within a sarcomere are crosslinked in the M-line. These links hold the filaments in register as the fibres contract, and prevent them coming out of alignment when fibres are stretched. In vertebrate muscle fibres, the M-line region is more prone to distortion under stress than the Z-disc (Agarkova and Perriard, 2005; Gautel, 2011; Linke, 2008). A well-ordered sarcomere is essential for the oscillatory contraction of the indirect flight muscle (IFM) of insects. The muscle is activated by periodic stretches and oscillations are maintained by the alternating contraction of opposing muscles (Pringle, 1978). The response of IFM to a rapid stretch depends on the match between myosin crossbridges on thick filaments and actin target sites on thin filaments (AL-Khayat et al., 2003; Perz-Edwards et al., 2011; Tregear et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2010). The fibres must be stiff to sense small length changes at high frequency. The proteins responsible for the stiffness of Drosophila IFM have a modular structure made up of immunoglobulin- (Ig) and fibronectin-like (Fn3) domains. The Drosophila gene sallimus encodes for isoforms of Sls (also known as Titin). There are two isoforms in IFM: kettin (540 kDa) and Sls700 (700 kDa), both of which link actin near the Z-disc to the end of the thick filament (Bullard et al., 2005; Burkart et al., 2007). Another Sls isoform, zormin, is found both in the Z-disc and in the M-line.

The M-line protein UNC-89 was originally identified in Caenorhabditis elegans (Benian et al., 1996). UNC-89 has SH3 and DH-PH (RhoGEF) signalling domains near the N-terminus, and two kinase domains near the C-terminus (Qadota et al., 2008; Small et al., 2004). The protein is needed for the integration of myosin into regular A-bands in the body-wall muscle: unc-89 mutants have disorganised myofibrils and M-lines are often absent, but motility of the worms is hardly affected. A protein with a sequence similar to that of the C-terminal region of UNC-89 was predicted from the Drosophila genome (Small et al., 2004) and identified in the M-line of the IFM (Burkart et al., 2007).

The vertebrate homologue of UNC-89, obscurin, has a similar domain structure, except that the SH3 and DH-PH domains are near the C-terminus (Bang et al., 2001; Fukuzawa et al., 2008; Russell et al., 2002; Young et al., 2001). Obscurin-A and obscurin-B are isoforms that have either an ankyrin-binding region or two kinase domains near the C-terminus. In mature skeletal fibres, obscurin is at the periphery of myofibrils, predominately in the M-line region (Fukuzawa et al., 2008; Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al., 2003). Obscurin-A binds to ankyrins in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), and this may create a link between the SR and the myofibril (Bagnato et al., 2003; Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al., 2006; Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al., 2003; Lange et al., 2009; Porter et al., 2005). There is a second protein, similar to obscurin, in vertebrate fibres: Obsl1 has Ig and Fn3 domains in a pattern that is similar to that seen in the N-terminal region of obscurin, but lacks the SH3, DH-PH and kinase domains, as well as the ankyrin-binding region near the C-terminus (Fukuzawa et al., 2008; Geisler et al., 2007). Obsl1 is in the M-line of skeletal muscle and, in contrast to obscurin, Obsl1 is in the interior of myofibrils, rather than at the periphery (Fukuzawa et al., 2008).

The vertebrate M-line is composed of a network of proteins, including titin, myomesin, obscurin and Obsl1, crosslinked through interacting Ig domains (Fukuzawa et al., 2008; Gautel, 2011; Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al., 2009). The function of the obscurin homologue (Unc-89) in Drosophila is rather different. The M-line does not contain titin or myomesin. In Drosophila, titin is replaced by the smaller proteins Sls and projectin (Bullard et al., 2005); of these, only the Sls isoform zormin has been found in the M-line. The Drosophila genome does not encode myomesin (Irina Agarkova, Functional diversity of contractile isoproteins: Expression of actin and myomesin isoforms in striated muscle, PhD thesis, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich, 2000).

The aim of the study we describe here was to find out how obscurin stabilises the M-line in IFM of Drosophila. The position of obscurin in the sarcomere was followed during development of the embryo, larva and pupa. In flies with reduced expression of obscurin, the regular structure of IFM sarcomeres was lost and flies were unable to fly. We show here that the symmetry of the thick filament and the length and polarity of the thin filament are dependent on obscurin. Obscurin is essential for the development and maintenance of the precise structure of the IFM that is needed for oscillatory contraction, whereas other muscles can function with a reduced amount of obscurin.

Results

The Drosophila obscurin gene and its expression products

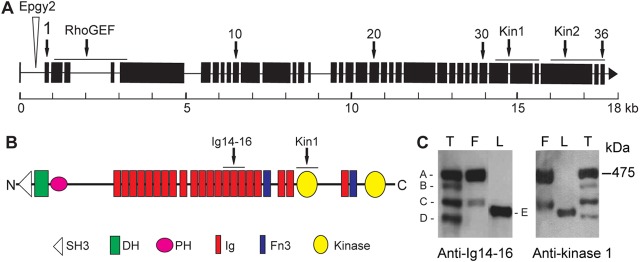

The obscurin gene (Unc-89) is located at chromosome arm 2R and annotated as CG33519 or CG30171 in Flybase. The Drosophila genome sequence predicts a gene of about 18 kb with 36 exons (Fig. 1A). The largest possible isoform obtained by exon splicing would have a predicted molecular mass of 475 kDa. The predicted domain structure of the entire gene has an SH3 domain near the N-terminus, followed by DH-PH domains. Further downstream, 21 Ig domains, two Fn3 domains, and two kinase domains are predicted (Fig. 1B). The largest Drosophila obscurin isoform is smaller than the nematode and vertebrate homologues: it has fewer Ig domains and lacks the IQ domain of the vertebrate protein.

Fig. 1.

The obscurin gene, domains in the protein and isoforms in the muscles. (A) Exons in the gene are numbered 1–36. Epgy2 marks the position of the P-element insertion. Lines above the gene show exons encoding the RhoGEF (DH-PH) and the two kinase domains (Kin1 and Kin2). (B) Domains predicted in the protein. Lines above domains show regions that were used to raise antibodies. (C) Western bots of isoforms in larva (L), adult thorax (T) and IFM (F). Blots were incubated with anti-Ig14-16 or anti-kinase1 antibodies. There are at least four isoforms in the thorax. Isoforms A and C are in IFM; the larva has isoform E only. Both antibodies reacted with all five obscurin isoforms.

The sequence of the cDNA that corresponds to the largest transcript in IFM contains all exons predicted in Flybase, except the 75 bp exon 15. Therefore, the largest transcript in IFM is derived from 35 exons. Prediction of the domains encoded by individual exons shows that single Ig domains are often encoded by two, or sometimes three, exons. The core sequence of kinase 1 is encoded by two exons, and kinase 2 by one exon; the regulatory domains of the kinases are encoded by exons downstream of the catalytic sequences. Exons coding for domains in the largest isoform of obscurin in IFM are shown in supplementary material Table S1.

The isoforms of obscurin that are present in the larva, and those in the muscles of the fly thorax and isolated IFM, were identified in western blots by using antibodies against Ig14, Ig15, Ig16 (hereafter referred to as Ig14-16) and kinase 1 (Fig. 1C). We detected four isoforms in the thorax, two of which (isoforms A and C) were in the IFM. The larva contained a single isoform (isoform E), which differed in size from the isoforms found in the adult fly. We cannot exclude the possibility that there is more than one isoform in individual bands on the blot. The western blot shows that Ig14-16 and kinase 1 domains are in all five isoforms. In experiments that are described in the following, we used anti-Ig14-16 antibody, except when indicated otherwise. Isoforms in the thorax of the late pupae, newly eclosed flies and mature wild-type adult flies were compared (supplementary material Fig. S1A). Pharate pupae contain the larger IFM isoform A and small amounts of the two non-IFM isoforms B and D. Young flies contain the pupal isoforms and traces of the IFM isoform C. Mature (6-day-old) flies contain more of IFM isoform C. Mass spectroscopy of peptides derived from the isoform that appeared after eclosion of pupae showed that the protein is likely to be a product of gene splicing, rather than protein cleavage. The most N-terminal peptides identified were about 53 kDa downstream of the N-terminus. The most C-terminal peptides were 12 residues from the C-terminus. If 53 kDa were cleaved from the N-terminus, the remaining protein would be 422 kDa. Obscurin isoform C is about 370 kDa, or 105 kDa smaller than isoform A. Therefore, more than 53 kDa is missing from isoform C, which is consistent with gene splicing.

Position of obscurin in embryonic, larval, and pupal muscles

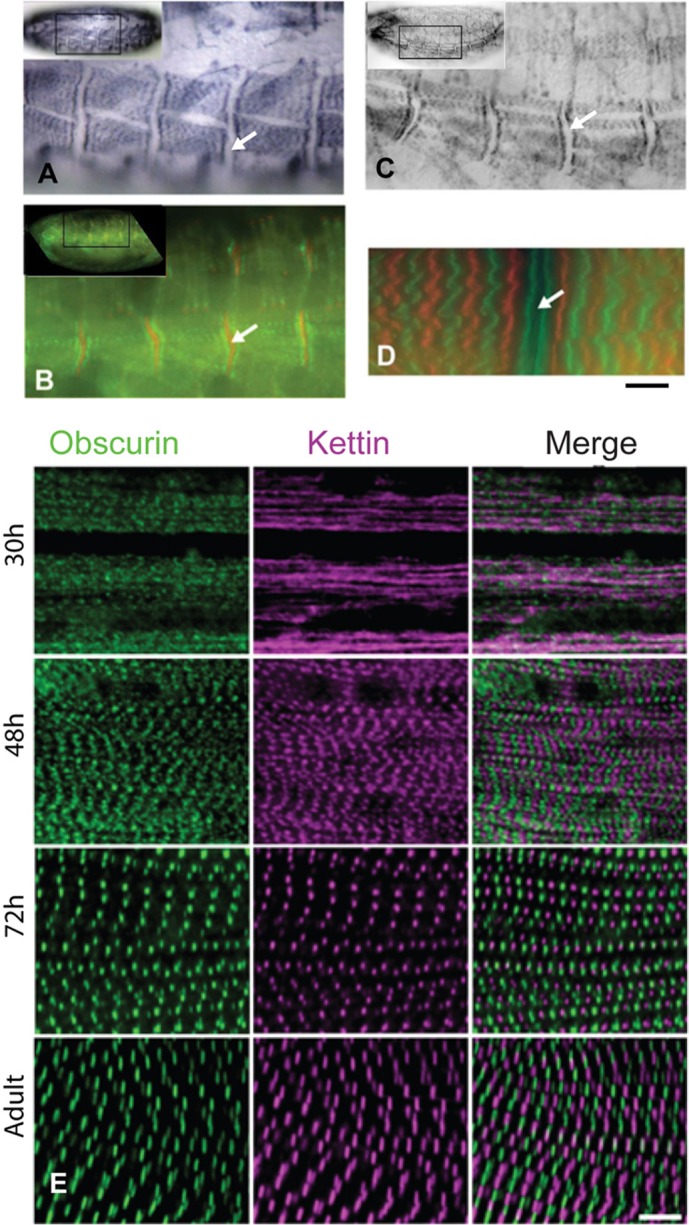

In our experiments, obscurin was first detected in the embryo at early stage 16 and in the M-line of somatic muscles during late stage 17. Obscurin was seen across the muscle in a striped pattern and was positioned laterally to the sites at which muscles are attached to the epidermis (Fig. 2A). The Z-disc protein kettin is close to the epidermal attachment sites in embryonic and larval muscle (Kreisköther et al., 2006) and obscurin is further from the attachment sites than kettin (Fig. 2B). The position of obscurin in unc89[EY15484] mutant embryos in which a P-element was inserted near the start of the obscurin gene (see below) is similar to that of wild-type embryos (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Obscurin in the embryo, larva and pupa of wild-type flies. Muscles were labelled with anti-obscurin. (A) Wild-type embryo (late stage 17) showing striations across the muscles, with a gap at the epidermal attachment site (arrows). (B) Embryo labelled with anti-obscurin (green) and anti-kettin (an isoform of Sls) (red). Obscurin is either side of the epidermal attachment site. (C) Embryo of P-element mutant. Labelling is similar to that of the wild-type embryo. (D) Larval body wall muscle, from a fly line with a GFP-sls gene. Anti-obscurin (red); GFP-kettin (green) marks the Z-discs and is in a doublet closer to the epidermal attachment site than obscurin in the M-line. (E) IFM in pupa at 30 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours APF and after eclosion (at 25°C); anti-obscurin (green) and anti-kettin (magenta). At 30 hours, obscurin has a punctate distribution and kettin is in amorphous strands. At 48 hours, myofibrils are closely packed and obscurin labelling appears as a broad band in the M-line and kettin at the Z-disc; at 72 hours, myofibrils are further apart and labelling of the narrow myofibrils appears as dots at the M-line and Z-disc. Myofibrils become wider in the adult, and obscurin and kettin are labelled in striations. Scale bars: 5 µm.

We found that obscurin of larval body wall muscles is in the M-line, by labelling larvae from a fly line expressing GFP-Sls with anti-obscurin antibody (Fig. 2D). GFP-Sls marks the Z-disc (Burkart et al., 2007) and was resolved as a doublet at the epidermal attachment site (Fig. 2D). Obscurin was midway between Z-discs and further from the attachment site than kettin, as was seen in the embryo.

During development of the pupa, obscurin transcripts could be amplified from IFM at 32 hours after puparium formation (APF) and, more strongly, at 48 hours (data not shown). The position of obscurin in the pupal IFM was followed from 30 hours APF to the newly emerged adult (Fig. 2E). At 30 hours, obscurin showed signs of periodicity, while the Z-disc protein kettin was in undifferentiated strands. At 48 hours, obscurin and kettin appeared as broad striations at the M-line and Z-disc; the striations were formed by labelled dots in narrow myofibrils lined up closely side-by-side. Striations of both obscurin and kettin became better defined at 72 hours, as sarcomere length increased and myofibrils were more separated. The narrow myofibrils at 72 hours gave the M-line and Z-disc a dot-like appearance. After eclosion of pupae, myofibrils were wider than at 72 hours and obscurin and kettin appeared in a striped pattern. The early pattern of labelling shows that obscurin begins to assemble into discrete structures before kettin (Fig. 2E).

Reduction of obscurin expression

We studied the function of obscurin in the assembly of the IFM sarcomere in flies in which the protein was reduced or absent. Obscurin expression was reduced by P-element insertion and by expression of siRNA targeting obscurin. The insertion of a P-element transposon into a gene can result in reduced expression of the gene. The mutant, unc89[EY15484], in which a P-element is inserted close to the start of the first intron of the obscurin gene was used here (Fig. 1A) and is refererred to as a P-element mutant. siRNA combined with the GAL4-UAS system with an appropriate driver can be used to target particular muscles in the fly. Driver lines were UH3-GAL4, which promotes expression in IFM, and Mef2-GAL4, which promotes expression in all muscles (Cripps, 2006; Dietzl et al., 2007; Ranganayakulu et al., 1996). Driver lines were crossed with two different UAS-unc89-IR lines, one targeted to exon 34 of the obscurin gene that encodes kinase 2 and the preceding Ig and Fn3 domains, the other to exon 12 that encodes Ig domains 5, 6 and 7 (supplementary material Table S1). The effect on the muscles was the same for the two lines, showing that off-target effects of the siRNA were unlikely. Results for the exon 34 target are described in this article. The fly lines UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR and MEF2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR are referred to as RNAi lines.

Developmental effects of reduced obscurin expression

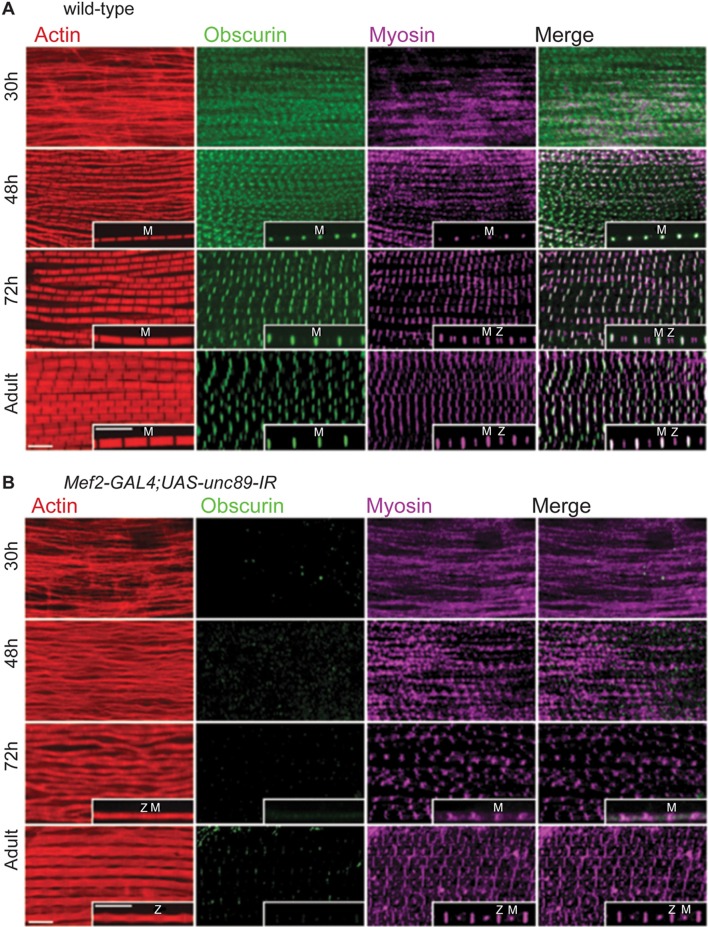

The effectiveness with which obscurin was knocked down in the larvae and pupae by siRNA using UH3-GAL4 and Mef2-GAL4 drivers was assessed in western blots. Like the wild-type, larvae of UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies had the larval obscurin isoform; the pupae had the two non-IFM isoforms, traces of the IFM isoform A and some remaining larval isoform (supplementary material Fig. S1B). Therefore, the IFM-specific UH3-GAL4 driver does not appreciably reduce obscurin levels in non-flight muscles. No obscurin could be detected in the larvae and pupae of Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies. The assembly of the IFM in the pupae of flies lacking obscurin was compared with that of wild-type pupae. The position of obscurin, myosin and actin was followed in pupal stages from 30 hours APF to the newly emerged adult. In wild-type pupae at 30 hours APF, obscurin was in broad striations, and myosin and actin in undifferentiated strands – like kettin at the same stage (Fig. 3A). At 48 hours, obscurin and myosin were in the M-line. Narrow myofibrils were packed closely together, and dots of antibody label at the M-line were seen best in single myofibrils. At 72 hours, myofibrils were wider and the M-line was better defined; myosin was labelled at the M-line and in a doublet close to the Z-disc. In the adult fly, myosin was labelled at the M-line and in a single band close to the Z-disc. The monoclonal anti-myosin antibody used here labels adult IFM in the H-zone and at the end of the A-band, probably because the epitopes are hidden in the rest of the A-band. The change in myosin labelling from a double to a single band close to the Z-disc is likely to be due to lengthening of the A-band between 72 hours and the adult stage.

Fig. 3.

Obscurin and myosin in the IFM of the pupa. IFM was labelled with anti-obscurin (green), anti-myosin (magenta) and phalloidin (red). Pupae were grown at 29°C. (A) Wild-type pupa. At 30 hours APF, obscurin is labelled in broad striations and myosin is in amorphous strands; at 48 hours, there are H-zones and obscurin and myosin are labelled in dots at the M-line; at 72 hours, obscurin and myosin striations are sharper and there is a doublet in the myosin label near the Z-disc; in the adult, myosin is labelled at the Z-disc in a single band. From 48 hours APF to the adult, myofibrils become wider, the H-zone better defined and sarcomeres longer. (B) Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR pupa. There is no obscurin in the IFM at any stage. At 30 hours APF, myosin is in amorphous strands; at 48 hours, there are no H-zones and myosin appears in broad striations (the fibres were too fragile to isolate single myofibrils); at 72 hours, myosin striations are in the M-line region; in the adult, myosin labelling is in a dot at the M-line and in a single band at the Z-disc. Myofibrils are narrower than in the wild-type. Inserts are single myofibrils at 1.5× the magnification of the main panels. Scale bars: 5 µm.

Lack of obscurin affected the assembly of myosin during pupal development. Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR pupae had no detectable obscurin (Fig. 3B). Myosin labelling at 30 hours and 48 hours APF was similar to that of myofibrils from wild type, although no H-zones were visible in phalloidin-stained myofibrils at 48 hours. At 72 hours, fuzzy dots of myosin within the M-line were more separated than at 48 hours, but there were no regular sarcomeres like those seen in wild-type flies at this stage. In the adult fly, myosin was detected as a dot at the M-line and also in a band close to the Z disc. The dot-like labelling at the M-line may be due to a better-defined H-zone in the core of the myofibrils, allowing better penetration of antibody. The late appearance of antibody labelling near the Z-disc suggests that elongation of the A-band was delayed. Developmental changes in the distribution of kettin (Fig. 2E) were unaffected in Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies (not shown), and the position of kettin was the same as for the wild type in adult IFM (supplementary material Fig. S3B).

Reduced obscurin expression in adult flies

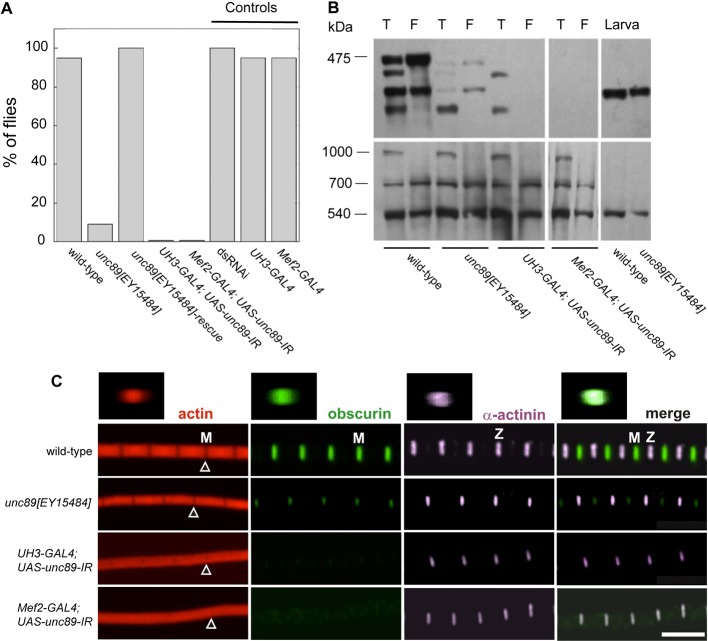

The flight capability of flies was tested to check the effect of reduced obscurin levels on the function of the IFM. Flies that were homozygous for the P-element insertion were flightless (Fig. 4A). To confirm that the phenotype of the P-element mutant was solely due to an effect on the obscurin gene, the mutant was rescued by precise excision of the P-element. The rescued flies could fly as well as the wild-type, showing that the wild-type obscurin gene was restored. UAS-unc89-IR flies driven by either UH3-GAL4 or Mef2-GAL4 were flightless, showing that the IFM was affected.

Fig. 4.

Effect of reduced obscurin expression. (A) Flight tests of wild-type, P-element, and RNAi knockdown flies; the proportion of flies able to fly is shown, n = 20 for each genotype. The unc89[EY15484] mutant and RNAi lines were flightless; flight was restored by excising the P-element. Control flies with UAS-RNAi (dsRNAi) or GAL4 drivers flew. (B) Obscurin isoforms in P-element and obscurin RNAi knockdown flies. Western blots of thorax (T), IFM (F) and larva were incubated with anti-obscurin (top) or anti-Sls as a loading control (bottom). The P-element mutant had the smallest thoracic isoform, reduced IFM isoforms and a wild-type larval isoform. UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies had the two non-IFM isoforms; there was no obscurin in the Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies. Thoraces had three isoforms of Sls (kettin is the 540 kDa isoform): the lack of the largest Sls isoform in IFM confirms the purity of the sample. (C) Obscurin in the IFM. Myofibrils were labelled with anti-obscurin (green), anti-α-actinin (magenta) antibodies, and phalloidin (red). Obscurin in the wild-type M-line is reduced in the unc89[EY15484] mutant and missing in the RNAi lines. H-zones (arrowheads) are missing in the RNAi lines. Z-stacks (top) show obscurin across the diameter of the myofibril. Scale bar: 5 µm.

Obscurin present in the total thoracic muscles and in isolated IFM of obscurin knockdown flies was compared with that of wild-type flies (Fig. 4B). The thoracic muscles of the P-element mutant, unc89[EY15484], lacked all but the smallest obscurin isoform D, whereas the IFM retained traces of the two IFM isoforms. The larval isoform was unaffected by the P-element insertion. As expected, the thoracic muscles of the UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR line had the two non-IFM isoforms B and D, and there was no detectable obscurin in the IFM. The Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR line had no detectable obscurin in the thoracic muscles or in the IFM. Since siRNA was targeted to the kinase 2 domain, abolition of the expression of all five obscurin isoforms by the Mef2-GAL4 driver, shows that all these isoforms have the kinase 2 domain, as well as the kinase 1 domain.

Structure of myofibrils in obscurin knockdown flies

The effect of the P-element mutation on the structure of the IFM in adult flies was compared with that of the two RNAi lines (Fig. 4C). Obscurin in the M-line was distributed throughout the cross section of the myofibril in wild-type flies; this was the case for myofibrils labelled with antibodies against Ig14-16 or kinase 1. Myofibrils in all three knockdown IFMs were narrower than in the wild-type. Faint labelling of obscurin was detected in the M-line of the P-element mutant, but there was none in the UAS-unc89-IR lines driven by UH3-GAL4 or Mef2-GAL4. The H-zone in the wild-type sarcomere was resolved in the P-element mutant but not in the RNAi lines. A similar effect on the H-zone as a result of downregulating obscurin has been described (Schnorrer et al., 2010). The narrower H-zone and the slightly longer sarcomere in the P-element mutant, suggests that thin filaments were somewhat longer than in the wild type. The lack of an H-zone in the sarcomeres of the RNAi lines showed that the ends of the thin filaments in a half sarcomere were not in register. By contrast, regular α-actinin labelling in all the IFMs showed that thin filaments were well-aligned where they enter the Z-disc. Therefore, the misalignment of filament ends in the H-zone of the IFM in obscurin knockdown flies is probably due to variability in thin filament length.

We did not expect obscurin in the larval muscle or the jump muscle (tergal depressor of the trochanter, TDT) of the MEF2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies. Obscurin was missing from the muscles, whereas Z-discs appeared normal (supplementary material Fig. S2A,B). This confirmed that non-flight muscles were affected in these flies. The crawling ability of Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR larvae lacking obscurin was slightly reduced compared with control larvae, whereas UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR larvae crawled as well as the controls (supplementary material Fig. S2C). Flies in both RNAi lines were able to jump as well as control flies. The power for jumping comes from the action of the TDT on the middle leg (Elliott et al., 2007). Therefore, obscurin is needed neither for larval crawling nor for fly jumping.

Effect of reduced obscurin expression on other proteins in IFM

Reducing the amount of obscurin was likely to affect other M-line proteins. In wild-type myofibrils, zormin was in both Z-disc and (supplementary material Fig. S3A). In the P-element mutant, zormin was in the Z-disc – as in the wild-type – whereas zormin in the M-line was predominately in the core of the myofibril. In UAS-unc89-IR flies driven by UH3-GAL4 and Mef2-GAL4, zormin was more diffuse in both the Z-disc and the M-line. Z-discs were regularly spaced, but in knockdown flies with the Mef2-GAL4 driver, the edges of Z-discs occasionally appeared abnormal.

Tropomodulin caps the pointed end of thin filaments at the borders of the H-zone in Drosophila IFM (Mardahl-Dumesnil and Fowler, 2001) and misaligned thin filament ends were expected to affect the position of tropomodulin. In the wild-type IFM, tropomodulin was in the H-zone (supplementary material Fig. S3B). In the P-element mutant and UAS-unc89-IR with both drivers, tropomodulin was confined to the core of the myofibril in the H-zone, whereas kettin in the Z-disc was unaffected. Although there was no clear H-zone in myofibrils of the RNAi lines, tropomodulin was apparently bound to the pointed ends of thin filaments in the core. It is possible that some thin filaments were not capped by tropomodulin, resulting in variable filament lengths as actin polymerized and depolymerized. In IFMs of obscurin knockdown flies, the weaker staining of tropomodulin in the M-line and the appearance of non-specific staining at the Z-disc, may mean that less tropomodulin is specifically associated with the pointed ends of the thin filaments. Thin filaments at the periphery of the knockdown myofibrils bypassed tropomodulin in the core. This suggests that the ends of thin filaments in the core are better aligned than at the periphery, and deviation in the length of filaments is more extreme at the periphery.

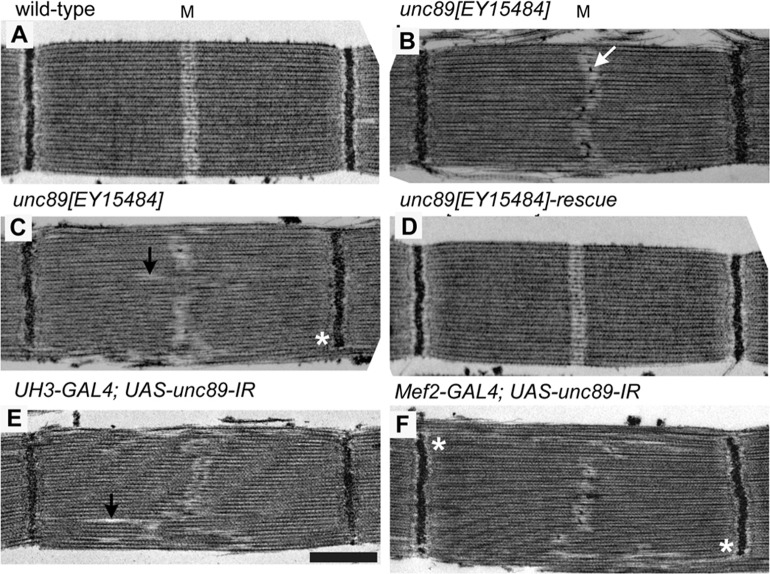

The fine structure of IFM in obscurin knockdown flies

The structure of the IFM in the P-element mutant and RNAi lines was compared with that of wild-type flies. Electron micrographs (EMs) showed abnormalities in the H-zone and M-line, which were more severe in RNAi lines than in the P-element mutant. The H-zone in the wild-type IFM is a clear region across the middle of the sarcomere, with the denser M-line marking the mid-point (Fig. 5). The phenotype of the P-element mutant varied in severity; in mild cases, the H-zone wandered from the middle of the sarcomere, and the M-line was broken up into electron-dense aggregates. In a more severe phenotype, H-zones were shifted further from the middle of the sarcomere. The abnormalities in sarcomere structure were reversed by excision of the P-element, confirming that when the wild-type obscurin gene was restored, the ability to fly was accompanied by normal muscle structure. IFMs in the RNAi lines showed more extreme shifts in the H-zone. The core of the myofibril was less affected than the periphery, where some filaments bypassed the Z-disc. An overview of myofibrils in wild-type and knockdown IFMs shows the extent of disruption in the sarcomeres (supplementary material Fig. S4).

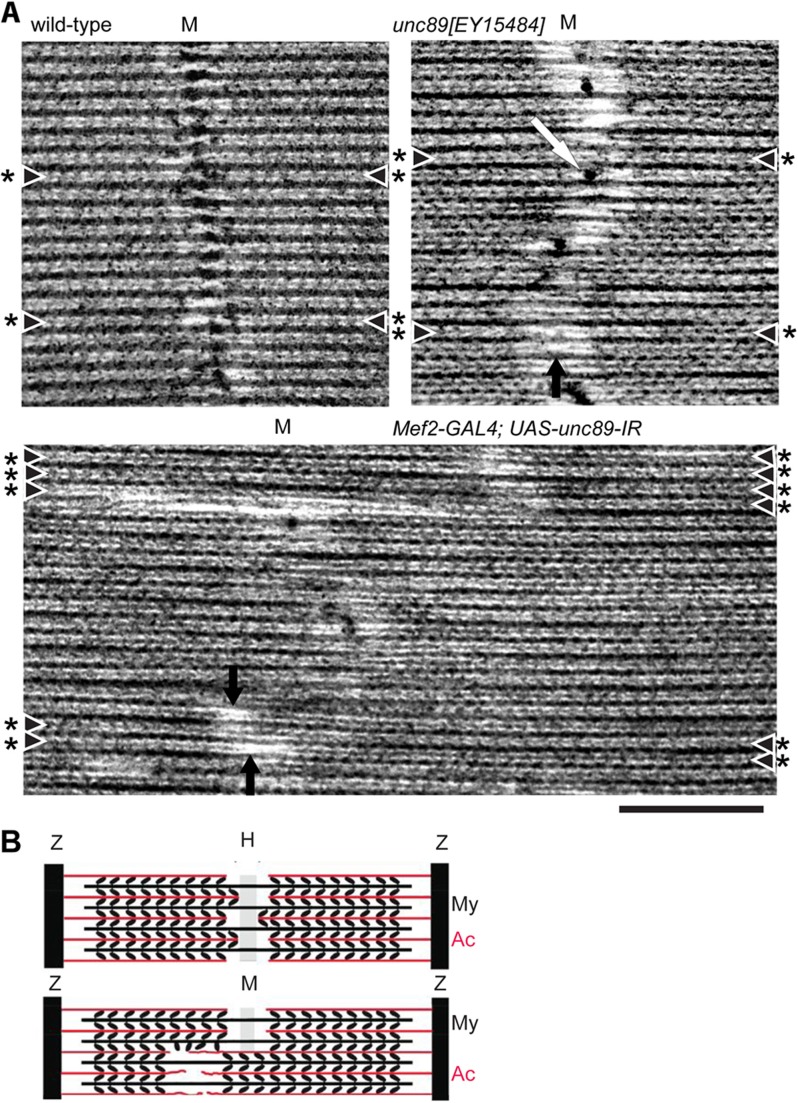

Fig. 5.

Structure of the IFM in flies with reduced obscurin. (A–F) EM images of (A) wild-type, (B,C) unc89[EY15484], (D) unc89[EY15484] rescued, (E) UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR and (F) Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies. The H-zone of the P-element mutant is wavy compared with the wild-type and there are aggregates in the H-zone (white arrow). In a more severe case, bare zones of thick filaments (black arrows) are shifted from the middle of the sarcomere. Excision of the P-element rescues the phenotype. IFMs in the RNAi lines have more irregular H-zones and shifted bare zones. Some filaments bypass the Z-disc at the myofibril periphery (asterisks). Scale bar: 0.6 µm.

The shift in the position of the H-zone in the sarcomere was due to asymmetry of thick filaments. The H-zone is formed by alignment of thick filaments in the middle of the sarcomere, where the rod regions of myosin molecules are assembled in anti-parallel fashion to form the bare zone. In the normal IFM sarcomere, thin filaments extend to the edge of the bare zone, and in rigor conditions, crossbridges between thick and thin filaments appear as arrowheads with the barbed end towards the Z-disc (Reedy, M. K. and Reedy, M. C., 1985). Thin filaments in half sarcomeres either side of the bare zone have the opposite polarity, which can be recognised by the direction of rigor crossbridges (Fig. 6A). In the P-element mutant, the bare zones of thick filaments were in the displaced H-zone. The polarity of crossbridges was reversed either side of the bare zone, and thin filaments were longer in one half sarcomere than the other. The effect was more pronounced in the RNAi lines (shown for Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR in Fig. 6A). The thick filaments were asymmetrical, with some bare zones far from the middle of the sarcomere. The polarity of thin filaments followed that of adjacent thick filaments, resulting in abnormally long or short thin filaments. Had thin filaments retained the normal length, the polarity of crossbridges would have been the same either side of a displaced thick filament bare zone; this was not observed. In both the P-element mutant and RNAi lines, thin filaments sometimes extended into the H-zone. A model for the effect of lack of obscurin on the symmetry of thick filaments and the length and polarity of thin filaments is shown in Fig. 6B.

Fig. 6.

Symmetry of thick and thin filaments in the IFM. (A) In the wild-type, the M-line appears as a broadening of the thick filament. In unc89[EY15484] flies, the M-line is replaced by dense aggregates between thick filaments (white arrow). Bare zones (black arrows) are more shifted in Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies. Myofibrils are in rigor and chevrons (crossbridges) on thin filaments show that the polarity of filaments changes either side of a shifted thick filament bare zone. M, M-line or mid-point of the sarcomere. Rows of chevrons (indicated by asterisks and arrowheads) are best viewed obliquely. Scale bar, 200 nm. (B) Model for the structure of the IFM sarcomere. Top, wild-type: the bare zone on thick filaments is central and the polarity of crossbridges on thin filaments is symmetrical. Variation in the length of thin filaments in the bare zone by a tropomyosin unit is shown (Haselgrove and Reedy, 1984). Bottom, flies lacking obscurin: thin (actin) filaments are longer on one side of a shifted bare zone than the other. The polarity of crossbridges is determined by the thin filament, and stays the same up to the edge of a shifted bare zone. My, myosin; Ac, actin.

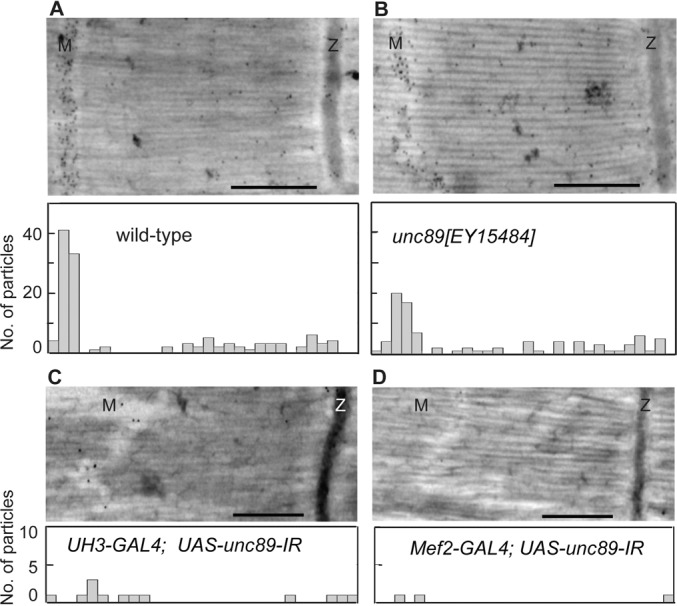

The extent to which obscurin had been displaced from the M-line line or was lacking from the sarcomere, was seen in EMs of cryosections of IFMs labelled with anti-obscurin antibody and Protein-A–gold (Fig. 7). Gold particles were uniformly distributed across the M-line region in wild-type IFM, confirming that obscurin is distributed throughout the cross-section of the M-line. Some obscurin remained in the H-zone of the P-element mutant. Obscurin was sparsely distributed in UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies, and there was a negligible amount in the Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies.

Fig. 7.

Obscurin in the IFM. Cryosections were labelled with anti-obscurin and Protein-A–gold. Histograms below the EM images show the distribution of gold particles. (A) In wild-type IFM, obscurin is in the M-line. (B) In the unc89[EY15484] mutant, remaining obscurin is in the M-line region. (C) There are obscurin remnants in the distorted H-zone of the UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR sarcomere. (D) The Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR sarcomere has negligible obscurin. Knockdown of obscurin in IFM is partial in the P-element mutant and effectively complete in the RNAi lines. Scale bars: 500 nm.

The structure of IFM thick filaments in obscurin knockdown flies

The asymmetry of thick filaments in the IFM of flies with reduced obscurin was seen in EM images of isolated filaments. Thick filaments from the wild-type IFM had a clear bare zone in the middle of the filament, whereas in the IFM of knockdown flies, the bare zone was frequently shifted towards one end of the filament (Fig. 8A). The majority of filaments from the P-element mutant unc89[EY15484] had a central bare zone, and there were also filaments with a variable shift in the bare zone (Fig. 8B). Some filaments from the RNAi lines had a central bare zone but, in the majority, the bare zone was shifted. UH3-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies had a greater proportion of filaments with central bare zones than the line driven by Mef2-GAL4. The majority of thick filaments in knockdown flies had a length that was similar to that of the wild-type filaments, although there was more variability in the length of filaments in the RNAi lines, and a few filaments were more than twice the normal length. It is likely that long thick filaments originated from the periphery of the myofibril, where the filaments bypassed the Z-disc.

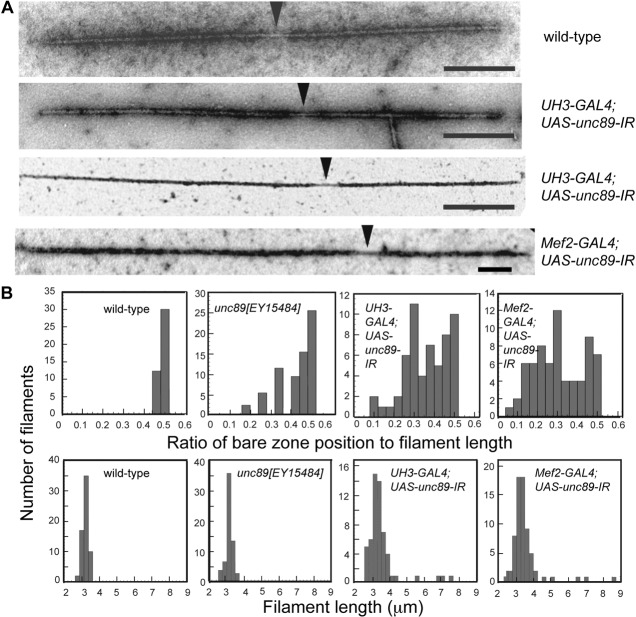

Fig. 8.

Structure of thick filaments in the IFM. (A) Isolated thick filaments negatively or positively-stained: the bare zone of the wild-type filament is central and those of RNAi lines driven by UH3-GAL4 or Mef2-GAL4 are offset. The filament in the bottom panel is 7.8 µm long, over twice the wild-type length. Scale bars, 500 nm. (B, top) The shortest distance from the end of the filament to the centre of the bare zone, relative to the length of the filament was measured. All samples had some filaments with central bare zones (shown as 0.5 in the figure). The position of the bare zone varied most in the RNAi lines. (B, bottom) The length of the majority of filaments in IFM of knockdown flies was close to that of wild-type flies (3.2 µm).

Association of obscurin with thick filaments

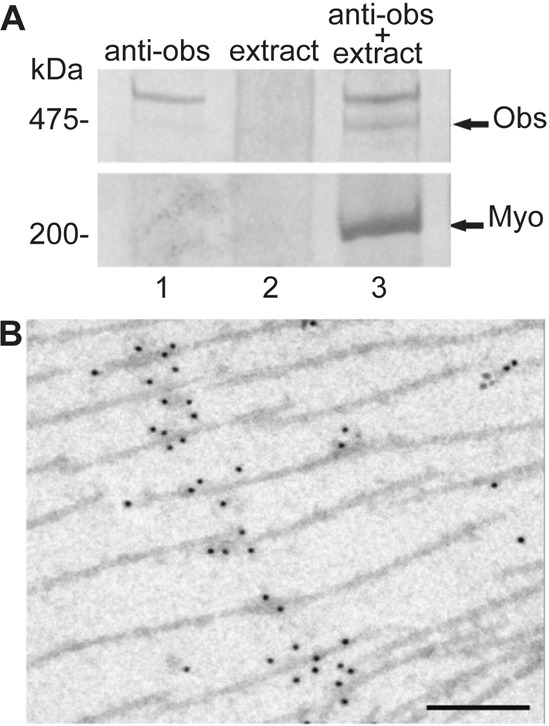

The abnormalities in the assembly of thick filaments in sarcomeres lacking obscurin suggest that the protein is associated with thick filaments. It had previously been shown that obscurin and myosin exist in a complex in vertebrate skeletal muscle (Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al., 2004), and the same was found for the IFM (Fig. 9A). Further confirmation that obscurin is associated with thick filaments came from EM images of labelled cryosections. In parts of the sections, thick filaments were separated from thin filaments and obscurin was in a discrete region of the filaments, probably corresponding to the mid-region of the filament at the M-line (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Association of obscurin with myosin. (A) SDS-PAGE of proteins bound to anti-obscurin. Protein-A beads with (lanes 1 and 3) and without (lane 2) anti-obscurin, were incubated with an extract of proteins from the fly thorax. Proteins pelleted with anti-obscurin were obscurin (Obs) and myosin (Myo). (B) EM image of a cryosection of thick filaments in IFM labelled with anti-obscurin antibody and Protein–A-gold. Obscurin is confined to a small area of the thick filaments. Scale bar: 200 nm.

Discussion

The function of obscurin in development and integrity of the flight muscle sarcomere was studied by reducing the expression of the protein. The advantage of using Drosophila is that obscurin is encoded by a single gene, which can be downregulated either by P-element transformation or by using RNAi. The two genes in higher vertebrates that encode obscurin and the smaller homologue Obsl1, have not – so far – been knocked out simultaneously, leaving the possibility that they compensate for each other (Lange et al., 2009). In zebrafish, there are two obscurin and two obsl1 genes, which compounds the problem (Geisler et al., 2007; Raeker et al., 2006; Raeker et al., 2010). The single gene in C. elegans that encodes UNC-89 has been targeted by siRNA directed to the body wall muscle. These RNAi experiments have shown that UNC-89 is needed for the overall organisation of the muscle (Small et al., 2004). Here, we have taken advantage of the regularity in the structure of Drosophila IFM to show how the lack of obscurin affects the lattice of thick and thin filaments.

The largest isoform of Drosophila obscurin is a little over half the size of the largest isoform of C. elegans UNC-89 or vertebrate obscurin; this is largely due to the number of Ig domains: 21 in Drosophila, 53 in the nematode and up to 67 in vertebrate obscurin-B. The domain architecture of the Drosophila protein is similar to that of the nematode UNC-89, with SH3 and DH–PH domains near the N-terminus, and two kinase domains at the C-terminus. The invertebrate proteins resemble vertebrate obscurin-B in having kinase domains at the C-terminus, rather than the ankyrin-binding domain of obscurin-A. The five isoforms we have identified in Drosophila muscles have Igs from the tandem Ig region and both the kinase domains. The main isoform in the IFM has all the domains illustrated in Fig. 1B. The appearance of a smaller IFM isoform after eclosion of the pupa was unexpected. However, changes in the amounts of obscurin and Sls isoforms have been observed throughout the lifespan of Drosophila, and isoform shifts in these proteins may affect fibre stiffness (Miller et al., 2008).

The distribution of obscurin throughout the M-line region of the sarcomere is in contrast to the arrangement of the larger obscurin isoforms in vertebrates, where obscurin-A and -B are confined to the periphery of the myofibril, and Obsl1 is inside (Fukuzawa et al., 2008; Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al., 2003). As the ankyrin-binding region at the C-terminus of the vertebrate obscurin-A is not present, it is unlikely that Drosophila obscurin is directly linked to the SR. The much reduced SR of Drosophila IFM is in the form of small vesicles positioned midway between the Z-disc and the M-line and there is no network of SR extending longitudinally along myofibrils, like that found in vertebrate skeletal muscle (Shafiq, 1964; Razzaq et al., 2001). Obscurin with 21 Ig domains might extend 80–100 nm along the sarcomere from the M-line; as the SR vesicles would be about 800 nm from the M-line, it is unlikely there would be any interaction between obscurin and the SR.

Obscurin in developing muscles of embryo and larva

Obscurin is in the M-line in somatic muscles throughout development. Unlike vertebrate obscurin, it was never observed in the Z-disc (Carlsson et al., 2008; Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al., 2009; Young et al., 2001). The protein is concentrated in the M-line relatively late in embryogenesis, during stage 17, when sarcomeres are being assembled. Myofilin and paramyosin, in the core of thick filaments, accumulate at the same time and expression peaks late in embryogenesis (Qiu et al., 2005; Vinós et al., 1992). Thus, the association of myosin with subsidiary thick filament proteins occurs as the filaments are assembled in the sarcomere.

Embryonic and larval development was unaffected in both the P-element and the RNAi knockdown flies, and pupae eclosed normally. The position of obscurin in the embryo of the P-element mutant, and the amount expressed in the larva were similar to that of the wild type. There are internal promoter sites in the C. elegans unc89 gene (Small et al., 2004) and in the vertebrate obscurin gene (Fukuzawa et al., 2005; Russell et al., 2002), which can lead to expression of smaller isoforms. The larval isoform is one of the smallest; if the Drosophila gene has multiple promoter sites, the larval isoform might be regulated by an internal promoter that was not affected by the P-element insertion in the first intron. Interestingly, the smallest isoform in the thoracic muscles of adult flies having the P-element insertion is expressed normally, whereas expression of the larger isoforms is considerably reduced (Fig. 3B). The small isoform might also be the result of transcription from an internal promoter.

Although larval muscles of progeny from the Mef2-GAL4; UAS-unc89-IR flies had no detectable obscurin, the ability of the larvae to crawl was only slightly less than that of wild-type larvae, and they were able to develop into adult flies. There are no well-defined H-zones or M-lines in the body-wall muscle of the wild-type larva (Ball et al., 1985), and obscurin might not be essential for maintaining the rather irregular striations in this muscle type. Similarly, although the TDT in adult flies from the same RNAi line had no detectable obscurin in the M-line, the sarcomeres showed regular striations and flies were able to jump as well as wild-type flies. Other muscles in the thorax of these flies also lacked obscurin; in the case of the leg muscles, this did not prevent the flies from walking. Therefore, the less well ordered muscles like the TDT, and other non-flight muscles in the thorax, can tolerate some misalignment of the thick filaments during development of the muscles in the larva, pupa and adult.

Obscurin in IFM of pupa and adult fly

In contrast to the non-flight muscles in the thorax, the IFM cannot function without obscurin. None of the obscurin knockdown flies was able to fly. This is expected because the regularity of the filament lattice is essential for oscillatory contraction of flight muscle (Dickinson et al., 1997). During development in the pupa, the IFM sarcomere is assembled by addition of thick and thin filaments to an initial array of interdigitating filaments between Z-bodies: new filaments are formed as they associate with the existing sarcomere (Reedy and Beall, 1993). Evidently, obscurin is needed to ensure that the middle of a growing thick filament is in the middle of the sarcomere. Reedy and Beall show the first thick filaments forming a sarcomere at 40 hours APF (at 22°C), and broad density appearing at the M-line at 42 hours, becoming narrower at 60 hours, by which time recognisable sarcomeres with well-defined Z-discs are formed. Here, we found that obscurin has a rudimentary periodicity in the IFM at 30 hours APF, before kettin, actin or myosin. Interestingly, kettin is distributed in strands along the developing myofibril, before migrating to the Z-disc at 48 hours. The development of the Z-disc is independent of obscurin and largely unaffected in obscurin knockdown. Myosin assembles into periodic structures in the absence of obscurin, although the distribution of myosin is abnormal in the mid-region of the sarcomere, where there is no regular H-zone. Therefore, although obscurin becomes periodic before kettin or myosin, it is not necessary for their subsequent arrangement into repeating structures. Obscurin is needed for the assembly of myosin into symmetrical A-bands.

The length of the IFM sarcomere is dependent on the length of thick filaments. On the outside of the thick filament, flightin limits the growth of the filaments and prevents the formation of excessively long sarcomeres (Contompasis et al., 2010; Reedy et al., 2000). The effect of a null mutation in the flightin gene (fln0) on the structure of the IFM is more extreme than the effect of lack of obscurin: sarcomeres are up to 30% longer than in the wild type wild-type and become increasingly disordered in the adult fly. Obscurin has little effect on sarcomere length, although it limits the range of thick filament lengths and influences the length of thin filaments.

Obscurin and sarcomere assembly

The less severe effect of the P-element mutation on the structure of the IFM, compared with that of the RNAi lines, might be due to a low level of obscurin in the muscles. A limited amount of obscurin produced early in sarcomere assembly would result in a core of thick filaments with near-central bare zones and peripheral filaments that were asymmetrical. Zormin was confined to the myofibril core in the obscurin P-element mutant and dislodged from the M-line in the RNAi lines; this suggests that obscurin and zormin are associated in the M-line. Zormin in the Z-disc was also affected, although there is no obscurin in the Z-disc of wild-type myofibrils; it is possible that zormin, once freed from the M-line, bound irregularly to a binding partner in the Z-disc.

The length and polarity of thin filaments are determined by the symmetry of thick filaments. The finding that thin filaments stop growing once they reach the H-zone, even if the H-zone is shifted to one side of the sarcomere, is consistent with a dynamic model for filament assembly in IFM (Mardahl-Dumesnil and Fowler, 2001). These authors showed that thin filaments grow from the pointed end (near the H-zone) and propose that uncapping of tropomodulin from the ends of the filaments is favoured by actomyosin interactions. A premature end to the actomyosin interactions, due to a shifted H-zone, would promote capping of thin filaments and prevent further elongation, resulting in variable thin filament lengths. Partial extension of some thin filaments into the H-zone is likely to be due to rigor contraction. Asymmetrical thick filaments have been observed in the leg muscles of a crab (Franzini-Armstrong, 1970). In these muscles, the length of the thin filaments is proportional to the length of the thick filaments in a half sarcomere. Whole A-bands have uniformly asymmetric thick filaments, which is unlike the pattern in the IFM of obscurin knockdown flies, where the bare zone is variably shifted in individual thick filaments. The crab muscles have no M-line and obscurin – if present – does not produce uniformly symmetrical sarcomeres.

So far, obscurin and zormin are the only proteins containing Ig domains that have been identified in the M-line of Drosophila IFM. Obscurin is associated with myosin in the thick filaments, but it is not clear why binding is restricted to the M-line. In the vertebrate sarcomere, binding sites in the C-terminal region of titin can dock obscurin and myomesin in the M-line. It is possible that obscurin and zormin bind specifically to an anti-parallel array of the rod regions of myosin molecules. Obscurin is predicted to be at least 80 nm long. Zormin, with nine Ig domains as well as other stretches of sequence, would be 40 to 50 nm long. The centre-to-centre distance between thick filaments is 56 nm in Drosophila IFM (Irving and Maughan, 2000), the interfilament spacing is 36 nm, so both molecules would easily span the distance between neighbouring filaments. The two proteins might form a complex that crosslinks thick filaments in the M-line, although this is likely to be simpler than the arrangement in the M-line of vertebrate muscles in which titin, myomesin and obscurin are all linked (Fukuzawa et al., 2008; Gautel, 2011).

The part played by the signalling domains in Drosophila obscurin may have something in common with the better-understood function of those domains in the nematode and in vertebrates. The effect of reducing obscurin expression with siRNA is similar in Drosophila IFM, C. elegans body wall muscle and vertebrate skeletal muscle: M-lines are missing and A-bands disordered, whereas Z-discs are little affected (Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al., 2006; Raeker et al., 2006; Small et al., 2004). In the case of the IFM (and possibly also C. elegans body-wall muscle), abnormalities in the A-band occur during development; they can be understood from the evidence that obscurin controls myosin assembly into symmetrical filaments throughout the sarcomere. In vertebrate skeletal muscle, the large obscurin isoforms at the periphery of the myofibril would be in the wrong place to nucleate the assembly of thick filaments within the sarcomere; in these muscles, the signalling domains of obscurin might indirectly influence recruitment of myosin into the A-band. However, the muscles of a mouse in which the obscurin gene was knocked out had normal sarcomere structure, although showing some changes in SR architecture (Lange et al., 2009). The obscurin signalling domains were evidently not necessary for A-band assembly. A study of the function of the signalling domains in Drosophila obscurin, for which there is a single gene, may help resolve these inconsistencies.

In summary, obscurin in Drosophila IFM controls the incorporation of myosin molecules into the thick filament, a process that determines the symmetry of the filament. This, in turn, affects the length and polarity of thin filaments. Obscurin is needed in the IFM to maintain the particular lattice structure that is all-important for this unusual muscle.

Materials and Methods

Genetic crosses, pupal aging, larval crawling, fly jumping and flight tests

Fly strain y'w67c23; P{w+y+EPgy2} [EY15484] contains a P-element in the first intron of the obscurin gene (CG30171) and was obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. To mobilize the P-element, virgin flies homozygous for the P-element were crossed en masse with males of the active transposase-coding line y w/Y; CyO/Sp; TM6b/2-3 Dr. Male y w/Y; P{EPgy2}Unc-89EY15484/CyO; Δ2-3 Dr progeny were crossed with virgin y w; CyO/Sco and jumpouts were identified by screening the progeny for y w; CyO, non-Dr males with white eyes. A homozygous line was established for each jumpout recovered, and analyzed by isolating genomic DNA by using PURGENE DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems) and by performing PCR reactions across the former P-element insertion site. Primers are in listed in supplementary material Table S2.

For RNAi experiments, obscurin UAS-responder lines (transformant IDs 29413 and 24378) were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (stockcenter.vdrc.at) and crossed with the transgenic driver lines Mef2-GAL4 and UH3-GAL4 (from Upendra Nongthomba, IISc, Bangalore, India). Crosses were performed at 29°C. Pupae were staged as described (Reedy and Beall, 1993): white pre-pupae with everted spiracles (defined as 0 hour APF) were collected and kept at 25°C or 29°C for a specified time.

Larval crawling and fly jumping were tested as described (Elliott et al., 2007; Vincent et al., 2012). Three-day-old flies were flight tested (Cripps et al., 1994). Flies were released inside a perspex box illuminated from above, and scored for the ability to fly up, horizontally or down.

Sequence analysis and protein expression

mRNA was extracted from IFMs of late pupae (96 hours APF) with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and cDNA synthesised with First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene). Predicted intron–exon junctions (www.flybase.org) were analysed using combinations of 16 sense and 16 reverse primers (supplementary material Table S2), and PCR products were sequenced. Confirmed exons and encoded domains were analysed with SMART, (http://smart.embl.de), (Letunic et al., 2004).

Kinase 1 cDNA encoding amino acid residues 3159–3538 was cloned into a modified pENTR gateway vector with an N-terminal 6His-tag (Mathias Gautel, King's College, London, UK). The coding sequence was recombined into BaculoDirect Linear DNA (Invitrogen) and expressed in sf9 cells; kinase 1 protein was purified on Ni-NTA agarose (GE Healthcare).

Antibodies

Antibodies used here were rabbit anti-obscurin Ig14-16 and anti-zormin (B1) (Burkart et al., 2007); rat anti-tropomodulin serum (from Velia Fowler, Scripps Research Institute, CA); rat monoclonal anti-kettin (anti-Sls), MAC 155 and anti-α-actinin, MAC 276 (Lakey et al., 1990); rat monoclonal anti-myosin, MAC 147 (Qiu et al., 2005). Rabbit antibody was raised against kinase1, and IgG was isolated from the rabbit serum (Biogenes, Berlin).

Immunolabelling and microscopy

Staged embryos were dechorionated and hot fixed, or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and devitellinised before labelling, dehydrating and embedding (Kreisköther et al., 2006). Third instar larvae of wild-type flies or flies expressing GFP-tagged Sls (Morin et al., 2001) were fixed as described above, washed in PBS supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBT), then labelled with primary and secondary antibodies. IFMs were dissected from glycerinated half thoraces and washed in relaxing solution (0.1 M NaCl, 20 mM Na-phosphate pH 7.2, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 5 mM EGTA) with protease inhibitors, and separated into myofibrils (Burkart et al., 2007). These were labelled with primary antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin (Sigma), washed in relaxing solution, then labelled with secondary antibody. Pupal IFMs and TDT were dissected in relaxing solution, fixed immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in relaxing solution, and labelled with primary and secondary antibodies. Antibodies were diluted in relaxing solution (IFM and TDT) or PBT (embryo and larval muscle). Antibodies against obscurin (Ig14-16), kettin, myosin, zormin and α-actinin were affinity-purified IgG, diluted 1∶100 (or, in the case of zormin, 1∶50), to about 10 µg/ml. Anti-tropomodulin serum was diluted 1∶200. Biotinylated secondary antibodies were used for embryos (Vector Laboratories, USA) and fluorescently labelled antibodies for double-labelled embryos, larvae and IFM (Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA). Samples were examined with a Zeiss LSM510 or Axioskop 50 confocal microscope with 63× oil-immersion objective and processed with LSM software.

Electron microscopy

Half thoraces were glycerinated in relaxing solution and processed as described (Farman et al., 2009; Reedy and Beall, 1993; Reedy et al., 1989). Thoraces were washed six times in rigor solution (40 mM KCl, 5 mM MOPS, pH 6.8, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM NaN3), fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde, 0.2% tannic acid, and washed in rigor solution, then in 100 mM Na-phosphate pH 6.0, 10 mM MgCl2. Secondary fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide, block staining in 2% uranyl acetate and dehydration in ethanol and embedding in Araldite were as before. Sections (25–50 nm) were stained with 7% uranyl acetate for 30 minutes to 1 hour, followed by Sato lead stain for 1 min.

For cryosectioning and immuno-EM, IFMs in relaxing solution with protease inhibitors were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and infiltrated with 2.1 M sucrose (Burkart et al., 2007; Lakey et al., 1990). Samples were frozen in liquid N2, sectioned, then blocked with 5% foetal calf serum and labelled with anti-obscurin IgG (0.1 mg/ml), and Protein-A–gold (10 nm). Sections were stained with methyl cellulose and uranyl acetate. Thick filament preparations were negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Samples were examined with a FEI Tecnai BioTWIN electron microscope at 120 kV.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Samples were analysed using 3% SDS-PAGE with 1.5% agarose (Tatsumi and Hattori, 1995). Third instar larvae in cold PBS were decapitated and internal tissues removed. The cuticle with body-wall muscles was transferred to sample buffer. Pupae were removed from puparia at specific times APF. A mid-line dorsal incision was made and the abdomen removed. Cold PBS was aspirated through the incision to remove sarcolytes, then the head was removed and the thorax transferred to sample buffer. Adult thoraces were frozen in liquid N2 immediately after dissection. IFMs were dissected from glycerinated thoraces. Tissues were homogenized in sample buffer with 6 M urea and protease inhibitors, and gels were immuno-blotted and developed using a chemiluminescent substrate (Millipore) (Burkart et al., 2007). Anti-kettin (Sls) hybridoma supernatent was diluted 1∶1000. Anti-obscurin (Ig14-16) IgG was 1 µg/ml, anti-obscurin (kinase1) IgG was 20 µg/ml and anti-myosin IgG was 0.4 µg/ml.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Proteins bound to obscurin were detected by precipitation with Protein-A beads coated with antibody (Bullard et al., 2004). Glycerinated half thoraces were washed in rigor solution, then homogenised in extraction buffer (1 M NaCl, 50 mM Na-phosphate pH 7.2, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT) and incubated on ice for 2 hours. The homogenate was diluted in binding buffer (0.2 M NaCl, 20 mM Na-phosphate pH 7.2, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT) and centrifuged. Protein-A beads with bound anti-obscurin IgG, in binding buffer, were incubated with the muscle extract at 4°C. Beads were washed with binding buffer and proteins were eluted with SDS-sample buffer. Bands on SDS-gels were analysed by MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy on an Applied Biosystems 4700 Proteomics analyser. Proteins were identified from a Drosophila database by using MASCOT.

Thick filaments

Thick filaments were released from myofibrils by mild digestion with calpain to separate them from the Z-disc (Contompasis et al., 2010; Reedy et al., 1981). Myofibrils, prepared from glycerinated IFMs of 10–20 wild-type or obscurin knockdown flies, were suspended in relaxing solution (10 mM NaCl, 20 mM MOPS pH 6.8, 5 mM Mg-acetate, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM ATP, 2 mM DTT, 5 mM NaN3), then centrifuged and resuspended in 30 µl of 20 mM imidazole pH 6.8, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM mercaptoethanol, 30% glycerol with 15 µM µcalpain (Calbiochem); CaCl2 was added to 2 mM and myofibrils incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Relaxing solution (100 µl) and 100 µM calpain inhibitor were added, and the suspension was passed through a 20G needle five times to separate the filaments. The suspension was centrifuged at 1500 g for 3 minutes to remove undissociated myofibrils.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Upendra Nongthomba for UH3-GAL4 driver flies and to Velia Fowler for anti-tropomodulin serum. Meg Stark assisted with EM and Adam Dowle with mass-spectroscopy (York Technology Facility). We thank Sean Sweeney, Peter Harrison and Mathias Gautel for helpful advice, and Renate Renkawitz-Pohl for support. Mary Reedy made many suggestions on EM preparations and this paper is dedicated to her memory.

Footnotes

Funding

The work was supported by a European Union FP6 Network of Excellence grant, MYORES, project number 511978 to B.B.; a Medical Research Council postdoctoral fellowship to A.A. in M. Gautel's group, King's College, London; and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant, number MOP-93727 to F.S. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.097345/-/DC1

References

- Agarkova I., Perriard J. C. (2005). The M-band: an elastic web that crosslinks thick filaments in the center of the sarcomere. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 477–485 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AL–Khayat H. A., Hudson L., Reedy M. K., Irving T. C., Squire J. M. (2003). Myosin head configuration in relaxed insect flight muscle: x-ray modeled resting cross-bridges in a pre-powerstroke state are poised for actin binding. Biophys. J. 85, 1063–1079 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74545-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnato P., Barone V., Giacomello E., Rossi D., Sorrentino V. (2003). Binding of an ankyrin-1 isoform to obscurin suggests a molecular link between the sarcoplasmic reticulum and myofibrils in striated muscles. J. Cell Biol. 160, 245–253 10.1083/jcb.200208109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball E., Ball S., Sparrow J. (1985). A mutation affecting larval muscle development in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Genet. 6, 77–92 10.1002/dvg.1020060202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bang M. L., Centner T., Fornoff F., Geach A. J., Gotthardt M., McNabb M., Witt C. C., Labeit D., Gregorio C. C., Granzier H., et al. (2001). The complete gene sequence of titin, expression of an unusual approximately 700-kDa titin isoform, and its interaction with obscurin identify a novel Z-line to I-band linking system. Circ. Res. 89, 1065–1072 10.1161/hh2301.100981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benian G. M., Tinley T. L., Tang X., Borodovsky M. (1996). The Caenorhabditis elegans gene unc-89, required fpr muscle M-line assembly, encodes a giant modular protein composed of Ig and signal transduction domains. J. Cell Biol. 132, 835–848 10.1083/jcb.132.5.835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard B., Ferguson C., Minajeva A., Leake M. C., Gautel M., Labeit D., Ding L., Labeit S., Horwitz J., Leonard K. R., et al. (2004). Association of the chaperone alphaB-crystallin with titin in heart muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7917–7924 10.1074/jbc.M307473200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard B., Burkart C., Labeit S., Leonard K. (2005). The function of elastic proteins in the oscillatory contraction of insect flight muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 26, 479–485 10.1007/s10974-005-9032-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart C., Qiu F., Brendel S., Benes V., Hååg P., Labeit S., Leonard K., Bullard B. (2007). Modular proteins from the Drosophila sallimus (sls) gene and their expression in muscles with different extensibility. J. Mol. Biol. 367, 953–969 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson L., Yu J. G., Thornell L. E. (2008). New aspects of obscurin in human striated muscles. Histochem. Cell Biol. 130, 91–103 10.1007/s00418-008-0413-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contompasis J. L., Nyland L. R., Maughan D. W., Vigoreaux J. O. (2010). Flightin is necessary for length determination, structural integrity, and large bending stiffness of insect flight muscle thick filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 395, 340–348 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps R. M. (2006). The contribution of genetics to the study of insect flight muscle formation. Nature's Versatile Engine- Insect Flight Muscle Inside And Out (ed. Vigoreaux J.). Georgetown: Landes Bioscience [Google Scholar]

- Cripps R. M., Ball E., Stark M., Lawn A., Sparrow J. C. (1994). Recovery of dominant, autosomal flightless mutants of Drosophila melanogaster and identification of a new gene required for normal muscle structure and function. Genetics 137, 151–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson M. H., Hyatt C. J., Lehmann F. O., Moore J. R., Reedy M. C., Simcox A., Tohtong R., Vigoreaux J. O., Yamashita H., Maughan D. W. (1997). Phosphorylation-dependent power output of transgenic flies: an integrated study. Biophys. J. 73, 3122–3134 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78338-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G., Chen D., Schnorrer F., Su K. C., Barinova Y., Fellner M., Gasser B., Kinsey K., Oppel S., Scheiblauer S., et al. (2007). A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 448, 151–156 10.1038/nature05954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott C. J., Brunger H. L., Stark M., Sparrow J. C. (2007). Direct measurement of the performance of the Drosophila jump muscle in whole flies. Fly (Austin) 1, 68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farman G. P., Miller M. S., Reedy M. C., Soto–Adames F. N., Vigoreaux J. O., Maughan D. W., Irving T. C. (2009). Phosphorylation and the N-terminal extension of the regulatory light chain help orient and align the myosin heads in Drosophila flight muscle. J. Struct. Biol. 168, 240–249 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini–Armstrong C. (1970). Natural variability in the length of thin and thick filaments in single fibres from a crab, Portunus depurator. J. Cell Sci. 6, 559–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa A., Idowu S., Gautel M. (2005). Complete human gene structure of obscurin: implications for isoform generation by differential splicing. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 26, 427–434 10.1007/s10974-005-9025-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa A., Lange S., Holt M., Vihola A., Carmignac V., Ferreiro A., Udd B., Gautel M. (2008). Interactions with titin and myomesin target obscurin and obscurin-like 1 to the M-band: implications for hereditary myopathies. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1841–1851 10.1242/jcs.028019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautel M. (2011). The sarcomeric cytoskeleton: who picks up the strain? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 39–46 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S. B., Robinson D., Hauringa M., Raeker M. O., Borisov A. B., Westfall M. V., Russell M. W. (2007). Obscurin-like 1, OBSL1, is a novel cytoskeletal protein related to obscurin. Genomics 89, 521–531 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselgrove J. C., Reedy M. K. (1984). Geometrical constraints affecting crossbridge formation in insect flight muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 5, 3–24 10.1007/BF00713149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving T. C., Maughan D. W. (2000). In vivo x-ray diffraction of indirect flight muscle from Drosophila melanogaster. Biophys. J. 78, 2511–2515 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76796-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontrogianni–Konstantopoulos A., Jones E. M., Van Rossum D. B., Bloch R. J. (2003). Obscurin is a ligand for small ankyrin 1 in skeletal muscle. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1138–1148 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontrogianni–Konstantopoulos A., Catino D. H., Strong J. C., Randall W. R., Bloch R. J. (2004). Obscurin regulates the organization of myosin into A bands. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C209–C217 10.1152/ajpcell.00497.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontrogianni–Konstantopoulos A., Catino D. H., Strong J. C., Sutter S., Borisov A. B., Pumplin D. W., Russell M. W., Bloch R. J. (2006). Obscurin modulates the assembly and organization of sarcomeres and the sarcoplasmic reticulum. FASEB J. 20, 2102–2111 10.1096/fj.06-5761com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontrogianni–Konstantopoulos A., Ackermann M. A., Bowman A. L., Yap S. V., Bloch R. J. (2009). Muscle giants: molecular scaffolds in sarcomerogenesis. Physiol. Rev. 89, 1217–1267 10.1152/physrev.00017.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisköther N., Reichert N., Buttgereit D., Hertenstein A., Fischbach K. F., Renkawitz–Pohl R. (2006). Drosophila rolling pebbles colocalises and putatively interacts with alpha-Actinin and the Sls isoform Zormin in the Z-discs of the sarcomere and with Dumbfounded/Kirre, alpha-Actinin and Zormin in the terminal Z-discs. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 27, 93–106 10.1007/s10974-006-9060-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey A., Ferguson C., Labeit S., Reedy M., Larkins A., Butcher G., Leonard K., Bullard B. (1990). Identification and localization of high molecular weight proteins in insect flight and leg muscle. EMBO J. 9, 3459–3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange S., Ouyang K., Meyer G., Cui L., Cheng H., Lieber R. L., Chen J. (2009). Obscurin determines the architecture of the longitudinal sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2640–2650 10.1242/jcs.046193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Copley R. R., Schmidt S., Ciccarelli F. D., Doerks T., Schultz J., Ponting C. P., Bork P. (2004). SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D142–D144 10.1093/nar/gkh088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke W. A. (2008). Sense and stretchability: the role of titin and titin-associated proteins in myocardial stress-sensing and mechanical dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Res. 77, 637–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardahl–Dumesnil M., Fowler V. M. (2001). Thin filaments elongate from their pointed ends during myofibril assembly in Drosophila indirect flight muscle. J. Cell Biol. 155, 1043–1054 10.1083/jcb.200108026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. S., Lekkas P., Braddock J. M., Farman G. P., Ballif B. A., Irving T. C., Maughan D. W., Vigoreaux J. O. (2008). Aging enhances indirect flight muscle fiber performance yet decreases flight ability in Drosophila. Biophys. J. 95, 2391–2401 10.1529/biophysj.108.130005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin X., Daneman R., Zavortink M., Chia W. (2001). A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenous loci in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 15050–15055 10.1073/pnas.261408198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perz–Edwards R. J., Irving T. C., Baumann B. A., Gore D., Hutchinson D. C., Kržič U., Porter R. L., Ward A. B., Reedy M. K. (2011). X-ray diffraction evidence for myosin-troponin connections and tropomyosin movement during stretch activation of insect flight muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 120–125 10.1073/pnas.1014599107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter N. C., Resneck W. G., O'Neill A., Van Rossum D. B., Stone M. R., Bloch R. J. (2005). Association of small ankyrin 1 with the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Membr. Biol. 22, 421–432 10.1080/09687860500244262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle J. W. (1978). The Croonian Lecture, 1977. Stretch activation of muscle: function and mechanism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 201, 107–130 10.1098/rspb.1978.0035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qadota H., McGaha L. A., Mercer K. B., Stark T. J., Ferrara T. M., Benian G. M. (2008). A novel protein phosphatase is a binding partner for the protein kinase domains of UNC-89 (Obscurin) in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2424–2432 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu F., Brendel S., Cunha P. M., Astola N., Song B., Furlong E. E., Leonard K. R., Bullard B. (2005). Myofilin, a protein in the thick filaments of insect muscle. J. Cell Sci. 118, 1527–1536 10.1242/jcs.02281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeker M. O., Su F., Geisler S. B., Borisov A. B., Kontrogianni–Konstantopoulos A., Lyons S. E., Russell M. W. (2006). Obscurin is required for the lateral alignment of striated myofibrils in zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 235, 2018–2029 10.1002/dvdy.20812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeker M. O., Bieniek A. N., Ryan A. S., Tsai H. J., Zahn K. M., Russell M. W. (2010). Targeted deletion of the zebrafish obscurin A RhoGEF domain affects heart, skeletal muscle and brain development. Dev. Biol. 337, 432–443 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganayakulu G., Schulz R. A., Olson E. N. (1996). Wingless signaling induces nautilus expression in the ventral mesoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Dev. Biol. 176, 143–148 10.1006/dbio.1996.9987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq A., Robinson I. M., McMahon H. T., Skepper J. N., Su Y., Zelhof A. C., Jackson A. P., Gay N. J., O'Kane C. J. (2001). Amphiphysin is necessary for organization of the excitation-contraction coupling machinery of muscles, but not for synaptic vesicle endocytosis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 15, 2967–2979 10.1101/gad.207801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy M. C., Beall C. (1993). Ultrastructure of developing flight muscle in Drosophila. II. Formation of the myotendon junction. Dev. Biol. 160, 466–479 10.1006/dbio.1993.1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy M. C., Beall C., Fyrberg E. (1989). Formation of reverse rigor chevrons by myosin heads. Nature 339, 481–483 10.1038/339481a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy M. C., Bullard B., Vigoreaux J. O. (2000). Flightin is essential for thick filament assembly and sarcomere stability in Drosophila flight muscles. J. Cell Biol. 151, 1483–1500 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy M. K., Reedy M. C. (1985). Rigor crossbridge structure in tilted single filament layers and flared-X formations from insect flight muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 185, 145–176 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90188-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy M. K., Leonard K. R., Freeman R., Arad T. (1981). Thick myofilament mass determination by electron scattering measurements with the scanning transmission electron microscope. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2, 45–64 10.1007/BF00712061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. W., Raeker M. O., Korytkowski K. A., Sonneman K. J. (2002). Identification, tissue expression and chromosomal localization of human Obscurin-MLCK, a member of the titin and Dbl families of myosin light chain kinases. Gene 282, 237–246 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00795-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorrer F., Schönbauer C., Langer C. C., Dietzl G., Novatchkova M., Schernhuber K., Fellner M., Azaryan A., Radolf M., Stark A., et al. (2010). Systematic genetic analysis of muscle morphogenesis and function in Drosophila. Nature 464, 287–291 10.1038/nature08799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq S. (1964). An electron microscopical study of the innervation and sarcoplasmic reticulum of the fibrillar flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Sci. 105, 1–6 [Google Scholar]

- Small T. M., Gernert K. M., Flaherty D. B., Mercer K. B., Borodovsky M., Benian G. M. (2004). Three new isoforms of Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-89 containing MLCK-like protein kinase domains. J. Mol. Biol. 342, 91–108 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi R., Hattori A. (1995). Detection of giant myofibrillar proteins connectin and nebulin by electrophoresis in 2% polyacrylamide slab gels strengthened with agarose. Anal. Biochem. 224, 28–31 10.1006/abio.1995.1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregear R. T., Edwards R. J., Irving T. C., Poole K. J., Reedy M. C., Schmitz H., Towns–Andrews E., Reedy M. K. (1998). X-ray diffraction indicates that active cross-bridges bind to actin target zones in insect flight muscle. Biophys. J. 74, 1439–1451 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77856-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A., Briggs L., Chatwin G. F., Emery E., Tomlins R., Oswald M., Middleton C. A., Evans G. J., Sweeney S. T., Elliott C. J. (2012). Parkin-induced defects in neurophysiology and locomotion are generated by metabolic dysfunction and not oxidative stress. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 1760–1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinós J., Maroto M., Garesse R., Marco R., Cervera M. (1992). Drosophila melanogaster paramyosin: developmental pattern, mapping and properties deduced from its complete coding sequence. Mol. Gen. Genet. 231, 385–394 10.1007/BF00292707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Liu J., Reedy M. C., Tregear R. T., Winkler H., Franzini–Armstrong C., Sasaki H., Lucaveche C., Goldman Y. E., Reedy M. K., et al. (2010). Electron tomography of cryofixed, isometrically contracting insect flight muscle reveals novel actin-myosin interactions. PLoS ONE 5, e12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P., Ehler E., Gautel M. (2001). Obscurin, a giant sarcomeric Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor protein involved in sarcomere assembly. J. Cell Biol. 154, 123–136 10.1083/jcb.200102110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.