Abstract

The goal of the present study was to investigate whether the psychophysical evaluation of taste stimuli using magnitude estimation influences the pattern of cortical activation observed with neuroimaging. That is, whether different brain areas are involved in the magnitude estimation of pleasantness relative to the magnitude estimation of intensity. fMRI was utilized to examine the patterns of cortical activation involved in magnitude estimation of pleasantness and intensity during hunger in response to taste stimuli. During scanning, subjects were administered taste stimuli orally and were asked to evaluate the perceived pleasantness or intensity using the general Labeled Magnitude Scale (Green 1996, Bartoshuk et al. 2004). Image analysis was conducted using AFNI. Magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness shared common activations in the insula, rolandic operculum, and the medio dorsal nucleus of the thalamus. Globally, magnitude estimation of pleasantness produced significantly more activation than magnitude estimation of intensity. Areas differentially activated during magnitude estimation of pleasantness versus intensity included, e.g., the insula, the anterior cingulate gyrus, and putamen; suggesting that different brain areas were recruited when subjects made magnitude estimates of intensity and pleasantness. These findings demonstrate significant differences in brain activation during magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness to taste stimuli. An appreciation for the complexity of brain response to taste stimuli may facilitate a clearer understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying eating behavior and over consumption.

Introduction

Magnitude estimation has been used extensively to investigate perception of taste and flavor stimuli. However, little is known about how magnitude estimation, in particular magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness, affects brain response to chemosensory stimuli. We focused here on pure taste stimuli.

The General Labeled Magnitude Scale (gLMS) is a labeled scale with ratio properties (Green et al. 1993), with the extreme anchor modified to “strongest imaginable sensation of any kind” in order to allow independence from the modality measured. Therefore, it allows for valid across-group comparisons (Bartoshuk et al. 2004).

The goal of the present study was to use the gLMS to investigate the effect of magnitude estimation on brain activation when participants evaluated the intensity and pleasantness of taste stimuli. Our hypothesis was that the brain areas activated during magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness would be distinct, reflecting two different cognitive processes. Furthermore, we hypothesized that brain activation patterns would vary depending on the quality and hedonic valence of the taste stimulus.

Materials and Methods

Participants and stimuli

Eighteen healthy young adults, nine females and nine males, ranging in age from 19 to 22 years (M = 20.7, SD = 0.99) participated in the study after giving informed consent. Participants received monetary compensation for participating in the study. The Institutional Review Boards at both San Diego State University and the University of California, San Diego gave approval of the study. Participants were screened for absence of ageusia and anosmia with taste threshold and odor threshold tests (Cain et al., 1983, modified as in Murphy, et al., 1990). Exclusionary criteria consisted of upper respiratory infection or allergies within the prior two weeks (Harris et al., 2006; Murphy et al., 2002). Dominant hemisphere was not assessed; however, all were right handed. Data from these subjects have previously been published (Haase et al., 2009a).

Stimulus and Stimulus Presentation

Stimuli were prepared in aqueous solution of distilled water and included: caffeine, 0.04M; citric acid, 0.01M; guanosine 5’-monophosphate (GMP), 0.025M; saccharin, 0.028M; sucrose, 0.64M; sodium chloride (NaCl), 0.16M (Haase et al., 2009b).

Inside the scanner, the participant was fitted with a bite bar that was adjusted to deliver stimuli to the tip of the tongue and that also served to reduce head movement. Stimuli and water were delivered at room temperature through seven 25 ft long plastic tubes, each connected to a 30 ml plastic syringe. The syringes were connected to seven pumps programmed to present 0.3ml of solution in one second (See Haase et al., 2007, for greater detail about this paradigm).

Stimuli and water were pseudo-randomly presented and separated by a 10s interstimulus interval (ISI). Each stimulus presentation was followed by two presentations of water; the first presentation of water was used as a rinse and the second presentation of water was used as a baseline comparison for the stimulus. Instructions were displayed on a screen through a computer interface. The 10s ISI consisted of stimulus delivery (1 s), cue to swallow: “please swallow” (2 s), instructions: “please rate pleasantness” or “please rate intensity” (1 s), and psychophysical scale used for rating intensity or pleasantness (6 s).

Experimental Design

Participants were required to complete two scanning sessions, one during which they received a nutritional preload, and one during which they were scanned after a 12-hour fast. For the purpose of the present manuscript, only the data corresponding to the fasting condition were analyzed.

Each scanning session consisted of two separate runs; each run was 24 min (1440 sec) in duration. Each stimulus was presented pseudo-randomly eight times in each run i.e., 16 repetitions for the two runs (see Haase et al., 2007 for more details). Pleasantness and intensity ratings were collected during separate runs. Psychophysical ratings were collected on each trial using gLMS scales (Bartoshuk et al., 2004; Green et al., 1996), using a MRI-compatible joystick. The intensity scale was numbered from 0 to 100 with 0 corresponding to no sensation and 100 to the strongest sensation imaginable. The pleasantness scale was numbered from 0 to 100 with 50 being neutral. Numbers between 0 and 50 corresponded to unpleasant sensations with 0 corresponding to the strongest unpleasant sensation imaginable. Numbers between 50 and 100 corresponded to pleasant sensations with 100 corresponding to the strongest pleasant sensation imaginable. Prior to the start of each run the participant was prompted with the instructions for the specific task. The participant was instructed to place the arrow controlled by the joystick at the location on the gLMS that represented his/her perception of the stimulus. A program written in MATLAB then recorded the location on the scale.

Data Acquisition

Imaging was conducted on a 3T General Electric (GE) Excite “shortbore” scanner. Structural images for anatomical localization of the functional images were collected first using a high-resolution T1-weighted whole-brain FSPGR sequence [Field of view (FOV) = 25 cm, slice thickness = 1 mm, resolution 1×1×1 mm3, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, Locs per slab = 136, flip angle = 15°]. A standard gradient echo EPI pulse sequence was used to acquire T2*-weighted functional images [(24 horizontal slices, FOV = 19 cm, matrix size = 64×64, spatial resolution = 2.97×2.97×3 mm3, flip angle = 90°, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, repetition time (TR) = 2 s)].

Data processing

Functional data were processed and analyzed using Analysis of Functional NeuroImage (AFNI) software (Cox, 1996). Preprocessing consisted of motion correction, temporal and spatial smoothing, and automasking. Further details regarding image analysis with this paradigm appear in Haase et al. (2007). Events were contrasted depending on stimuli (taste vs. water) and cognitive task (taste vs. water during magnitude estimation of pleasantness to be compared to taste vs. water during magnitude estimation of intensity).

An ANOVA was conducted with AFNI (Cox, 1996) on the percent change calculated at each voxel with two within participant factors, i.e. cognitive task (two levels: intensity and pleasantness) and stimuli (six levels: caffeine, citric acid, GMP, NaCl, saccharin and sucrose) and yielded the contrasts presented in the current article. The contrasts of interest for the present study include Contrast I, i.e. activations in response to all taste stimuli when participants gave magnitude estimates of intensity; and Contrast P, i.e. activations in response to all taste stimuli when participants gave magnitude estimates of pleasantness, Contrast I sucrose and Contrast I caffeine, i.e. activations in response to respectively sucrose and caffeine when participants evaluate intensity of sucrose and caffeine. Contrast P sucrose and Contrast P caffeine, i.e. activations in response to respectively sucrose and caffeine when participants gave magnitude estimates of pleasantness of sucrose and caffeine. Activation maps were corrected for multiple comparisons with the AlphaSim program written by Doug Ward and implemented in AFNI (Cox, 1996).

A conjunction contrast (Contrast I & Contrast P) was calculated with the 3dcalc function available in AFNI (Cox, 1996), on individual contrasts previously corrected for multiple comparisons, in order to identify common areas of brain activation during magnitude estimation of pleasantness and intensity.

A difference Contrast (Contrast P minus Contrast I) was calculated with the 3dttest function from AFNI and corrected for multiple comparisons with the program AlphaSim (Cox, 1996).

Results

Psychophysical measurements

Mean magnitude estimates of intensity collected in the fMRI scanner were respectively 49.5 ± 5.1 for caffeine, 44.0 ± 4.2 for citric acid, 25.8 ± 2.7 for GMP, 44.0 ± 5.2 for NaCl, 40.7 ± 4.9 for saccharin, 40.7 ± 4.9 for sucrose (M ± SEM), on a scale from 0-100, with 0 corresponding to no sensation and 100 to the strongest sensation imaginable (Bartoshuk et al., 2004; Green et al., 1996). Mean gave magnitude estimates of pleasantness were respectively 27.9 ± 2.4 for caffeine, 38.1 ± 3.1 for citric acid, 38.7 ± 1.6 for GMP, 36.5± 3.6 for NaCl, 36.3 ± 3.6 for saccharin, 55.1 ± 3.5 for sucrose (M ± SEM), on a scale from 0 to 100 with 0 corresponding to the strongest unpleasant sensation imaginable and 100 corresponding to the strongest pleasant sensation imaginable, and 50 being neutral.

Imaging Results

Conjunction Analysis: Magnitude estimation of pleasantness and intensity

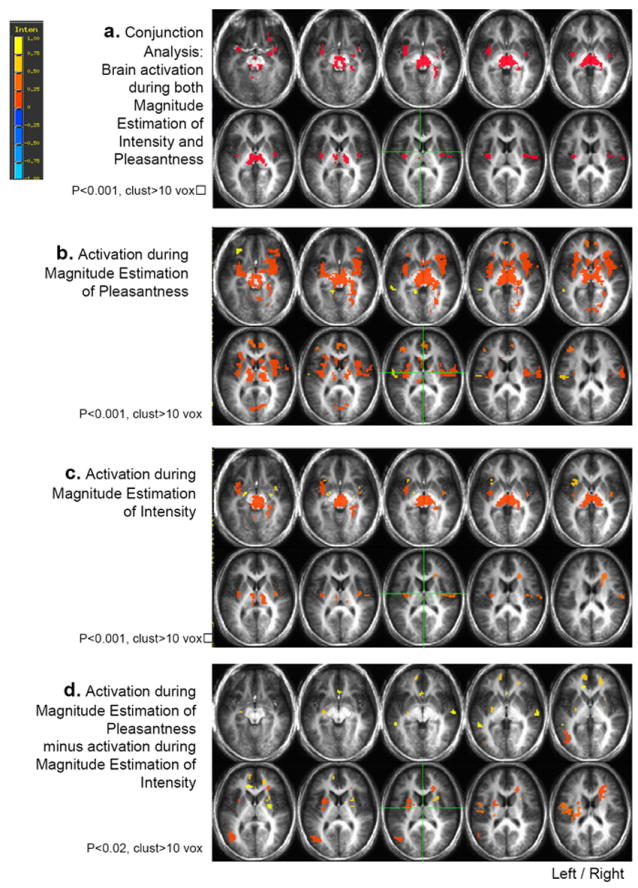

A conjunction analysis between contrast P and contrast I revealed that areas commonly activated during magnitude estimation of pleasantness and intensity included left and right insula, thalamus, right amygdala, right orbitofrontal cortex Brodmann area (BA) 47, and cerebellum (Figure 1a, Table 1).

Figure 1.

a. Brain areas found activated during both magnitude estimation of pleasantness and magnitude estimation of intensity, in the conjunction analysis between Contrast P and Contrast I. Voxels with a p<0.001 and belonging to clusters of at least 10 voxels were considered activated.

b. Brain areas activated in response to taste during magnitude estimation of pleasantness.

Thresholds see figure 1a.

c. Brain areas activated in response to taste during magnitude estimation of intensity. Thresholds see figure 1a.

d. Brain areas activated in the difference between magnitude estimation of pleasantness and magnitude estimation of intensity in Contrast P minus Contrast I. Thresholds see figure 1a.

Table 1.

Areas Significantly Activated during Magnitude Estimation of Intensity and during Magnitude Estimation Pleasantness of Taste Stimuli.

| number voxels | identification area | Tal X | Tal Y | Tal Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 377 | thalamus | 3.3 | -21.2 | -1.3 |

| 130 | right culmen | 4.8 | -50.5 | -16.8 |

| 85 | left claustrum/insula | -33.4 | -2.5 | 1.6 |

| 62 | right insula | 45.1 | -9.5 | 11.5 |

| 16 | right BA 13 | 38.1 | 4.7 | -8.9 |

| 14 | right amygdala | 28.3 | -6.2 | -8.2 |

| 10 | right BA 47 | 26.7 | 27 | -9.5 |

Activation during magnitude estimates of intensity

The analysis of the contrast I, corresponding to magnitude estimates of intensity of taste stimuli, revealed activation in the left and right insula, the thalamus, the right parahippocampal gyrus, the right putamen, the right orbitofrontal cortex BA 47 and the cerebellum (Figure 1b, Table 2).

Table 2.

Areas Significantly Activated during Magnitude Estimation of Intensity of Taste Stimuli.

| number voxels | identification area | Tal X | Tal Y | Tal Z | Mean signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 809 | right culmen | 3.7 | -31 | -7.3 | 5.15 |

| thalamus | 3 | -20 | 2 | ||

| right parahippocampal gyrus | 26 | -44 | 4 | ||

| 109 | left insula | -34 | -0.7 | 0 | 4.73 |

| 69 | right insula | 45.6 | -9.6 | 11.8 | 4.63 |

| 54 | right anterior cingulate gyrus | 22.6 | 20.3 | 20.3 | -4.81 |

| 22 | left insula | -31.5 | 18 | 2.8 | 4.44 |

| 18 | right BA 13/38 | 38.4 | 4.7 | -9.1 | 4.65 |

| 14 | right lentiform/putamen | 28.3 | -6.2 | -8.3 | 5.01 |

| 13 | right BA 47 | 26 | 26.7 | -9.7 | 4.29 |

| 10 | right lentiform/globus pallidus | -22.2 | -6.3 | -5.3 | 4.30 |

Activation during magnitude estimates of pleasantness

Magnitude estimates of the pleasantness of taste stimuli, produced activation in the left and right insula, the thalamus, the left and right orbitofrontal cortex BA 47, the right parahippocampal gyrus, the right and left caudate nuclei, the anterior cingulate, the left middle frontal gyrus, the left postcentral gyrus, the left middle temporal gyrus and the left lingual gyrus (Figure 1c, Table 3).

Table 3.

Areas Significantly Activated during Magnitude Estimation of Pleasantness of Taste Stimuli.

| number voxels | identification area | Tal X | Tal Y | Tal Z | Mean signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 2277 | Thalamus | 11.1 | -11.8 | -0.4 | 4.97 |

| Left insula | -36 | 3 | -1 | ||

| Right insula | 39 | 6 | 2 | ||

| Right OFC 47 | 40 | 34 | -7 | ||

| Right parahippocampal gyrus | 28 | -37 | -4 | ||

| Right caudate nucleus | 10 | 13 | 5 | ||

| Left caudate nucleus | -5 | 14 | 5 | ||

| 81 | anterior cingulate | 1.5 | 47.8 | 9.2 | 4.58 |

| 35 | left middle frontal gyrus | -39.8 | 38.5 | 16.6 | 4.61 |

| 29 | left postcentral gyrus | -53.7 | -12.9 | 17.3 | 4.78 |

| 20 | left middle temporal gyrus | -38.1 | 1.9 | -28.6 | 4.67 |

| 14 | left OFC 47 | -32.6 | 36.4 | -7.6 | 4.54 |

| 11 | left middle temporal gyrus | -54.8 | -37 | 1.8 | 4.40 |

| 10 | left lingual gyrus | -14.7 | -41 | -1.4 | 4.47 |

Activation during magnitude estimates of pleasantness minus intensity

The contrast calculating the difference between activation during magnitude estimation of pleasantness minus activation during magnitude estimation of intensity exhibited activation in the left insula, the left postcentral gyrus, the left superior temporal gyrus, the left middle temporal gyrus, the left and right putamen and the right superior temporal gyrus (Figure 1d, Table 4).

Table 4.

Areas Differentially Activated during Magnitude Estimation of Intensity and Pleasantness: Subtraction of Activation during Magnitude Estimation of Intensity from Activation during Pleasantness.

Contrast P- Contrast I

| number voxels | identification area | Tal X | Tal Y | Tal Z | Mean signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 76 | left middle temporal gyrus | -43.9 | -63.8 | 9.7 | 3.16 |

| 60 | right anterior cingulate | 22.9 | 26.8 | 17.8 | 2.95 |

| 51 | left putamen | -26 | 1.6 | 14.1 | 2.84 |

| 50 | left potscentral gyrus | -46.9 | -9.1 | 20.1 | 3.10 |

| 36 | left superior temporal gyrus | -32.9 | 3.4 | -26.3 | 2.94 |

| 34 | right superior temporal gyrus | 36.8 | 6.7 | -26.4 | 3.02 |

| 33 | left insula | -29 | -22.6 | 21.3 | 3.09 |

| 25 | left medial frontal gyrus | -10.8 | 53 | 4.8 | 2.89 |

| 18 | right anterior cingulate | 20.5 | 44.6 | 6 | 2.76 |

| 17 | right putamen/claustrum | 27.1 | 9.8 | 12 | 2.73 |

| 16 | left lentiform gyrus/putamen | -28.1 | -11.7 | -0.5 | 2.89 |

| 15 | right superior temporal gyrus | 58.9 | -15.2 | 1.4 | 3.19 |

| 12 | anterior cingulate gyrus | -0.5 | 23.7 | -1.2 | 2.83 |

| 12 | left anterior cingulate gyrus | -11.8 | 35.5 | 7.3 | 2.75 |

| 11 | left middle temporal gyrus | -50.9 | -37.6 | 1.7 | 3.19 |

| 11 | right lentiform gyrus/putamen | 28.5 | -4.2 | 8.8 | 2.94 |

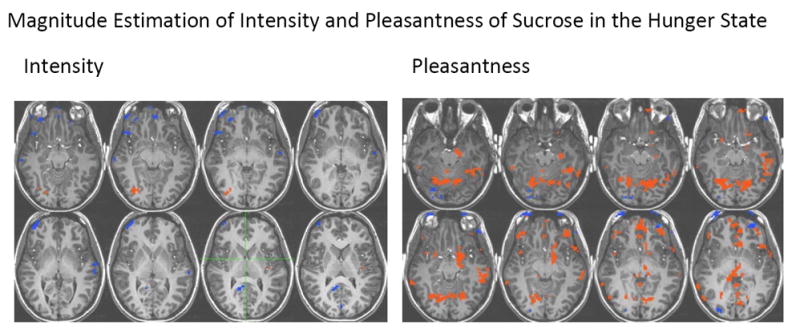

Activation in response to sucrose

Magnitude estimation of intensity of sucrose (in the sucrose minus water contrast) produced activation in the insula and the thalamus (Figure 2), whereas magnitude estimation of pleasantness of sucrose produced activation in the left and right insula, the thalamus, the orbitofrontal cortex BA 47, the anterior cingulate cortex, the middle frontal gyrus, the left and right postcentral gyrus, the left and right caudate nuclei, the left and right putamen, the lingual gyrus and the left middle temporal gyrus (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Brain areas activated in response to sucrose during magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness. Voxels with a p<0.005 and belonging to clusters of at least 10 voxels were considered activated.

Activation in response to caffeine

In contrast to the pleasant stimulus sucrose, magnitude estimation of intensity of caffeine (in the caffeine minus water contrast) produced activation in the right amygdala, the left BA 13 and the thalamus, whereas the magnitude estimation of pleasantness for caffeine revealed no significant activation that exceeded statistical thresholds.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to investigate the effect of using general labeled magnitude estimation scales to evaluate intensity and pleasantness of taste stimuli during an fMRI experiment on brain activation.

Psychophysical measurements / Behavioral performance

The psychophysical ratings collected through the general labeled magnitude estimation technique showed that the stimuli were perceived, as attested by the intensity judgments, and that all participants found sucrose pleasant and caffeine unpleasant and the other stimuli neutral to slightly unpleasant. For the purpose of the current article, sucrose and caffeine were used as examples of pleasant and unpleasant stimuli due to the magnitude estimations of pleasantness that they produced in the participants.

Activations common to magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness

The conjunction analysis allowed for the extraction of areas commonly activated during magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness. Those areas included insula, thalamus, orbitofrontal cortex BA 47 and amygdala. These areas correspond to gustatory central projections in primates (Rolls, 1995; Scott & Giza, 2000; Scott et al., 1986; Yaxley, Rolls, & Sienkiewicz, 1990), are congruent with clinical studies in humans describing taste deficits (Bornstein, 1940; Motta, 1959; Penfield & Faulk, 1955; Pritchard, Macaluso, & Eslinger, 1999) and are consistent with previous neuroimaging studies on gustatory function (Cerf-Ducastel et al., 2001; Faurion et al., 1999; Jacobson et al., 2010; Kobayakawa et al., 1996; Kobayakawa et al., 1999; O’Doherty et al., 2001; Small, Gregory et al., 2003). This result was expected considering that both tasks involve gustatory processing.

Brain activation pattern during magnitude estimates of intensity

During magnitude estimation of intensity, activation was consistently observed in the insula and the thalamus (see Figure 1a), areas that receive primary gustatory projections (Benjamin & Burton, 1968; Pritchard et al., 1986). It has been suggested that taste intensity coding occurs in primary gustatory areas (Scott et al., 1991; Smith-Swintosky et al., 1991). Our observations are congruent with the hypothesis of a sustained activation in primary taste areas during magnitude estimation of intensity. This result is also consistent with a study from Grabenhorst and Rolls (2008), who found activation in the insula when subjects were attending to intensity, although the cognitive task used in that study was different from the task in the present study and necessarily required different cognitive resources, as those subjects were asked to attend and remember intensity rather than to do a magnitude estimation task. Veldheuizen and Small, (2011), also observed activation in insula when subjects attended to taste in a detection task. Interestingly, there is evidence to suggest that activation to sweetness in primary taste cortex is modulated by expectation (Woods et al., 2011).

As reported above, activation was also observed in orbitofrontal cortex BA 47, putamen, parahippocampal gyrus and cerebellum, areas involved in reward processing and memory, two aspects of the processing of taste stimuli that contribute to the perceptual experience of taste. We did not focus on stimulus concentration in this study. Two studies that did (Small, et al., 2003; Spetter et al., 2010) also found activation that was modulated by concentration in the middle insula and amygdala, thalamus and putamen.

Brain activation pattern during magnitude estimates of pleasantness

In comparison to magnitude estimation of intensity, activation during magnitude estimation of pleasantness was greater, in particular in the cingulate cortex and in the orbitofrontal cortex. The caudolateral orbitofrontal cortex (BA 47) has been identified as a secondary area for taste (Rolls, 2000), and has been found activated in response to pleasant and unpleasant taste stimuli (Francis et al., 1999; O’Doherty et al., 2001; Small, Gregory et al., 2003; Zald et al., 2002; Zald et al., 1998). It also has been involved in processing preference and reward in primates and humans (Elliott et al., 2000; Wallis, 2007). In the study mentioned above, Grabenhorst and Rolls (2008) found activation in the orbitofrontal cortex and the cingulate cortex during attention to pleasantness. The present results are consistent with this finding, although, in the present study, using magnitude estimation, activation in those areas was also found to a lesser extent during magnitude estimation of intensity.

Difference in activation during magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness

The difference contrast Contrast P minus Contrast I exhibited only positive activation, which indicates that evaluating pleasantness of taste stimuli produced more activation than evaluating their intensity. According to an evolutionary perspective, the gustatory system developed hedonic mechanisms to assist in the decision to ingest or reject potentially harmful substances (Scott, 1981), which might translate into a stronger saliency of taste pleasantness compared to taste intensity. A stronger saliency of taste pleasantness might in turn lead to greater activations in response to taste when making magnitude estimates of pleasantness than when making magnitude estimates of intensity.

This hypothesis is similar to the notion of cognitive diversion due to shifting between a task requiring a higher emotional involvement, i.e. making magnitude estimates of pleasantness, and a task requiring less emotional involvement, i.e. making magnitude estimates of intensity. Cognitive diversion was observed in tasks such as labeling emotional expression (Hariri, Bookheimer, & Mazziotta, 2000) or identifying gender when processing emotional faces (Critchley et al., 2000), rating and recognizing emotionally salient pictures (Liberzon et al., 2000), and rating the intensity of aversive visual stimuli (Taylor et al., 2003). Zatorre, Jones-Gotman, & Rouby, (2000) similarly found additional activation during pleasantness evaluation in a PET study investigating the neural mechanisms involved in odor pleasantness and intensity judgments. Their hypothesis was that pleasantness evaluation requires the activation of additional structures involved in affective processing or access to the internal state.

Subtracting activation while subjects made magnitude estimates of intensity from activation while subjects made magnitude estimates of pleasantness revealed that areas differentially activated between the two contrasts included the insula, the anterior cingulate gyrus, the putamen, the superior and middle temporal gyrus, the medial frontal and the postcentral gyrus (Figure 1d; Table 4).

We found that making magnitude estimates of pleasantness activated the insula to a greater extent than making magnitude estimates of intensity, a result that might be seen in contrast to the results of Grabenhorst and Rolls (2008). However, as mentioned above, the cognitive tasks used in the two studies differed, with the older study measuring attention and memory and the present magnitude estimation. A sub region of the insula has been shown to be activated by the task of magnitude estimation itself and has been postulated as a multisensory magnitude estimation area (Baliki et al. 2009). A stronger activation of the insula during pleasantness estimation might be related to a higher saliency of hedonic value for taste stimuli during the magnitude estimation task.

In addition to the insula, activations were notably found in the anterior cingulate gyrus and the putamen. The anterior cingulate cortex has been involved in decision making (Gehring and Willoughby, 2002), and in particular, it has been suggested that the function of the cingulate cortex might include the use of reward-related information to guide action selection (Hadland, et al., 2003). A study by Taylor et al. (2003) demonstrated that performing a cognitive task can modulate brain activation in response to stimuli with an emotional content in limbic and paralimbic areas. Specific activations were found in the cingulate gyrus and in the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex when comparing the effect of rating and passively viewing pictures (Taylor et al., 2003). In the present study, greater activation in the cingulate cortex during magnitude estimation of pleasantness compared to magnitude estimation of intensity may be related to a greater involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex in the reward component related to pleasantness in the decision making task of magnitude estimation.

The putamen has been shown to be involved in reward, and in particular it has been suggested that the putamen encodes the stimulus-action-reward association, guiding ongoing actions toward their expected outcomes and directions (Haruno & Kawato, 2006; Hori et al., 2009). Small, Jones-Gotman, & Dagher (2003) reported dopamine release in the caudate and the putamen of participants fed to satiety, with associated reduction of pleasantness. O’Doherty et al., (2006) measured responses in the putamen in relation to participants’ food preferences. Recent work neuroimaging of taste while hungry older adults judged pleasantness of sucrose has demonstrated that decreased activation in the caudate is significantly related to increased BMI and waist circumference, suggesting the importance of this reward area to processing of gustatory information (Green, et al., 2011). We speculated that activation may be related to decreased dopamine levels in older adults as well as in those who are obese. In the present study, significant activation in the putamen during magnitude estimation of pleasantness minus magnitude estimation of intensity and significant activation of the caudate during magnitude estimation of pleasantness considered alone may be related to a greater involvement of both these areas in the reward component related to pleasantness in the stimulus-action-reward association, i.e. taste-pleasantness-magnitude estimation, of the task.

Activation in response to sucrose and caffeine

Magnitude estimation of intensity of sucrose and caffeine produced patterns of activation similar to the one observed in the conjunction analysis, with most activation in the insula and the thalamus.

On the other hand, magnitude estimation of pleasantness of sucrose and caffeine produced sharply different activation based on the stimulus. Magnitude estimation in response to sucrose, which had been rated pleasant by all the participants, produced strong activations in the insula, the orbitofrontal cortex, the thalamus, the anterior cingulate gyrus, the middle frontal gyrus, the postcentral gyrus, the putamen, the lingual gyrus and the middle temporal gyrus. Those areas are consistent with previous neuroimaging studies on gustatory function (Cerf-Ducastel et al., 2001; de Araujo et al., 2003; Faurion et al., 1999; Jacobson et al., 2010; Kobayakawa et al., 1996; Kobayakawa et al., 1999; O’Doherty et al., 2001; Small, et al., 2003) and on taste pleasantness (Francis et al., 1999; Haase et al., 2011; Green et al., 2011; Jacobson et al., 2010; O’Doherty et al., 2001; Small, et al., 2003; Zald et al., 2002; Zald et al., 1998). However, magnitude estimation of pleasantness of caffeine, which had been rated as unpleasant by all the participants, yielded no detectable positive activation at the threshold considered.

The striking difference in activation during magnitude estimation of pleasantness of the two stimuli suggests that the hedonic nature of the stimulus affects brain activations when participants evaluate pleasantness but not when they evaluate intensity. It also suggests that magnitude estimation of pleasantness evaluation of a pleasant stimulus i.e. sucrose, tends to maximize activations in response to that stimulus, while magnitude estimation of pleasantness of an unpleasantness stimulus, i.e. caffeine, tends to minimize or inhibit activations in response to that stimulus. We note that since there is no baseline of passive tasting it is not possible to know how these responses differ from taste responses that occur in the absence of evaluation.

In the present study, participants were tested after a 12-hour fast, in a hungry state. It has been shown that food is judged more pleasant in a state of hunger (Rolls et al. 1983). In addition, selective increase or decrease of activation in response to a stimulus have been described in the case of sensory specific satiety, in particular in the orbitofrontal cortex. Responses in the caudolateral orbitofrontal cortex have been shown to decrease to zero when an animal is fed to satiety (Rolls et al., 1989), which is paralleled by a decreased pleasantness in humans (Rolls et al., 1981). Modulation of activation in brain regions as a function of hunger and taste pleasantness suggests that in the present study where participants were in the state of hunger, activations during the magnitude estimation of pleasantness of sucrose, a nutritive and pleasant stimulus, were maximized, likely reflecting a desirable stimulus, a potential source of calories and reward. On the other hand, brain activations in response to caffeine, a nonnutritive and unpleasant stimulus, were minimized, possibly reflecting a non desirable or even potentially toxic stimulus (Scott et al., 1995).

Conclusion

This study investigated the effect of magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness ratings during an fMRI experiment on brain activation. Results demonstrated that magnitude estimation of pleasantness produced stronger activation to taste stimuli than magnitude estimation of intensity, in particular in the insula, the anterior cingulate gyrus and the putamen, which maybe be related to increased saliency when evaluating hedonic and reward value of taste stimuli relative to the evaluation of intensity. In addition, responses to individual stimuli, e.g., sucrose and caffeine, revealed that the effect of the in magnitude estimation task greatly depends on the valence of the stimulus, in particular when participants evaluated pleasantness. Magnitude estimation of pleasantness of sucrose, in a hungry state, exhibited very strong activations in areas involved in taste pleasantness, a response that was not observed with caffeine.

These findings demonstrate significant differences in brain activation during magnitude estimation of intensity and pleasantness of taste stimuli and hence, the impact of using magnitude estimation and measuring either intensity or pleasantness. The results suggest that different brain areas were recruited when analyzing intensity and hedonic value of taste stimuli, emphasizing the complexity of the brain response to taste stimuli and the potential implications for eating behavior and over consumption.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH grants R01AG04085 and R03DC051234. We thank Dr. Richard Buxton for fMRI expertise.

References

- Anderson AK, Christoff K, Stappen I, Panitz D, Ghahremani DG, Glover G, Gabrieli JD, Sobel N. Dissociated neural representations of intensity and valence in human olfaction. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(2):196–202. doi: 10.1038/nn1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki MN, Geha PY, Apkarian AV. Parsing pain perception between noiceptive representation and magnitude estimation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2009;101(2):875–887. doi: 10.1152/jn.91100.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MA, Gatenby JC, Zeiger JD, Gore JC. Cortical activity evoked by focal electric-taste stimuli. Paper presented at the International Symposium for Olfaction and Taste; Brighton. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Green BG, Hoffman HJ, Ko CW, Lucchina LA, Marks LE, Snyder DJ, Weiffenbach JM. Valid across-group comparisons with labeled scales: the gLMS versus magnitude matching. Physiol Behav. 2004;82(1):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin RM, Burton H. Projection of taste nerve afferents to anterior opercular-insular cortex in squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) Brain Res. 1968;7(2):221–231. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(68)90100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Frost JA, Hammeke TA, Bellgowan PS, Rao SM, Cox RW. Conceptual processing during the conscious resting state. A functional MRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 1999;11(1):80–95. doi: 10.1162/089892999563265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein WS. Cortical representation of taste in man and monkey. II. The localization of the cortical taste area in man and a method of measuring impairment of taste in man. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 1940;13:133–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanac M. physiological role of pleasure. Science. 1971;173:1103–1107. doi: 10.1126/science.173.4002.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain WS, Gent J, Catalanotto FA, Goodspeed RB. Clinical evaluation of olfaction. Am J Otolaryngol. 1983;4:252–256. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(83)80068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerf-Ducastel B, Haase L, Murphy C. Correlation between brain activity and online psychophysical measurement: how the evaluative task affects brain activation. Chem Senses. 2006;(31):493. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Cerf-Ducastel B, Van De Moortele PF, MacLeod P, Le Bihan D, Faurion A. Interaction of gustatory and lingual somatosensory perceptions at the cortical level in the human: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Chem Senses. 2001;26(4):371–383. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley H, Daly E, Phillips M, Brammer M, Bullmore E, Williams S, Van Amelsvoort T, Robertson D, David A, Murphy D. Explicit and implicit neural mechanisms for processing of social information from facial expressions: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;9(2):93–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200002)9:2<93::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo IE, Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET, Hobden P. Representation of umami taste in the human brain. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90(1):313–319. doi: 10.1152/jn.00669.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo IE, Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET, McGlone F. Human cortical responses to water in the mouth, and the effects of thirst. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90(3):1865–1876. doi: 10.1152/jn.00297.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo IE, Rolls ET, Kringelbach ML, McGlone F, Phillips N. Taste-olfactory convergence, and the representation of the pleasantness of flavour, in the human brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18(7):2059–2068. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Dissociable functions in the medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex: evidence from human neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10(3):308–317. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faurion A, Cerf B, Van De Moortele PF, Lobel E, Mac Leod P, Le Bihan D. Human taste cortical areas studied with functional magnetic resonance imaging: evidence of functional lateralization related to handedness. Neurosci Lett. 1999;277(3):189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00881-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis S, Rolls ET, Bowtell R, McGlone F, O’Doherty J, Browning A, Clare S, Smith E. The representation of pleasant touch in the brain and its relationship with taste and olfactory areas. Neuroreport. 1999;10(3):453–459. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199902250-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudge JL, Breitbart MA, Danish M, Pannoni V. Insular and gustatory inputs to the caudal ventral striatum in primates. J Comp Neurol. 2005;490(2):101–118. doi: 10.1002/cne.20660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring JR, Willoughby AR. The medial frontal cortex and the rapid processing of monetary gains and losses. Science. 2002;295(5563):2279–2282. doi: 10.1126/science.1066893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Fencsik DE. Functions of the medial frontal cortex in the processing of conflict and errors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(23):9430–9437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09430.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Lima F, Helmstetter FJ, Agudo J. Functional mapping of the rat brain during drinking behavior: a fluorodeoxyglucose study. Physiol Behav. 1993;54(3):605–612. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90256-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA, O’Doherty J, Dolan RJ. Appetitive and aversive olfactory learning in humans studied using event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2002;22(24):10829–10837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10829.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabenhorst F, Rolls ET. Selective attention to affective value alters how the brain processes taste stimuli. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27(3):723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BG, Dalton P, Cowart B, Shaffer G, Rankin K, Higgins J. Evaluating the ‘Labeled Magnitude Scale’ for measuring sensations of taste and smell. Chem Senses. 1996;21(3):323–334. doi: 10.1093/chemse/21.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BG, Shaffer GS, Gilmore MM. A semantically-labeled magnitude scale of oral sensation with apparent ratio properties. Chemical Senses. 1993;18(1993):683–702. [Google Scholar]

- Green E, Jacobson A, Haase L, Murphy C. Reduced nucleus accumbens and caudate nucleus activation to a pleasant taste is associated with obesity in older adults. Brain Research. 2011;1386:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(13):4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest S, Grabenhorst F, Essick G, Chen Y, Young M, McGlone F, de Araujo I, Rolls ET. Human cortical representation of oral temperature. Physiol Behav. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase L, Green E, Jacobson A, Murphy C. Males and females show differential brain activation to taste when hungry and sated in gustatory and reward areas. Appetite. 2011;57(2):421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase L, Cerf-Ducastel B, Murphy C. Cortical activation in response to pure taste stimuli during the physiological states of hunger and satiety. NeuroImage. 2009a;44:1008–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase L, Cerf-Ducastel B, Murphy C. The effect of stimulus delivery technique on perceived intensity functions for taste stimuli: implications for fMRI studies. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2009b;71:1167–1173. doi: 10.3758/APP.71.5.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase L, Cerf-Ducastel B, Buracas G, Murphy C. On-line psychophysical data acquisition and event-related fMRI protocol optimized for the investigation of brain activation in response to gustatory stimuli. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;159(1):98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland KA, Rushworth MF, Gaffan D, Passingham RE. The anterior cingulate and reward-guided selection of actions. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;89(2):1161–1164. doi: 10.1152/jn.00634.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Bookheimer SY, Mazziotta JC. Modulating emotional responses: effects of a neocortical network on the limbic system. Neuroreport. 2000;11(1):43–48. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R, Davidson TM, Murphy C, Gilbert PE, Chen M. Clinical evaluation and symptoms of chemosensory impairment: one thousand consecutive cases from the Nasal Dysfunction Clinic in San Diego. American Journal of Rhinology. 2006;20:101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruno M, Kawato M. Different neural correlates of reward expectation and reward expectation error in the putamen and caudate nucleus during stimulus-action-reward association learning. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95(2):948–959. doi: 10.1152/jn.00382.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollerman JR, Tremblay L, Schultz W. Involvement of basal ganglia and orbitofrontal cortex in goal-directed behavior. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:193–215. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y, Minamimoto T, Kimura M. Neuronal encoding of reward value and direction of actions in the primate putamen. J Neurophysiol. 102(6):3530–3543. doi: 10.1152/jn.00104.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson A, Green E, Murphy C. Age-related functional changes in gustatory and reward processing regions: An fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2010;53(2):602–620. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinomura S, Kawashima R, Yamada K, Ono S, Itoh M, Yoshioka S, Yamaguchi T, Matsui H, Miyazawa H, Itoh H, et al. Functional anatomy of taste perception in the human brain studied with positron emission tomography. Brain Res. 1994;659(1-2):263–266. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90890-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada R, Hashimoto T, Kochiyama T, Kito T, Okada T, Matsumura M, Lederman SJ, Sadato N. Tactile estimation of the roughness of gratings yields a graded response in the human brain: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2005;25(1):90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayakawa T, Endo H, Ayabe-Kanamura S, Kumagai T, Yamaguchi Y, Kikuchi Y, Takeda T, Saito S, Ogawa H. The primary gustatory area in human cerebral cortex studied by magnetoencephalography. Neurosci Lett. 1996;212(3):155–158. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12798-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayakawa T, Ogawa H, Kaneda H, Ayabe-Kanamura S, Endo H, Saito S. Spatio-temporal analysis of cortical activity evoked by gustatory stimulation in humans. Chem Senses. 1999;24(2):201–209. doi: 10.1093/chemse/24.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML, O’Doherty J, Rolls ET, Andrews C. Activation of the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex to a Liquid Food Stimulus is Correlated with its Subjective Pleasantness. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13(10):1064–1071. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.10.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon I, Taylor SF, Fig LM, Decker LR, Koeppe RA, Minoshima S. Limbic activation and psychophysiologic responses to aversive visual stimuli. Interaction with cognitive task. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23(5):508–516. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai JK, Assheuer J, Paxinos G. Atlas of the Human Brain. New York: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mazoyer B, Zago L, Mellet E, Bricogne S, Etard O, Houde O, Crivello F, Joliot M, Petit L, Tzourio-Mazoyer N. Cortical networks for working memory and executive functions sustain the conscious resting state in man. Brain Res Bull. 2001;54(3):287–298. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe C, Rolls ET. Umami: a delicious flavor formed by convergence of taste and olfactory pathways in the human brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(6):1855–1864. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta G. I centri corticali del gusto. Bulletino delle Scienze Mediche. 1959;131:480–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama N, Nakasato N, Hatanaka K, Fujita S, Igasaki T, Kanno A, Yoshimoto T. Gustatory evoked magnetic fields in humans. Neurosci Lett. 1996;210(2):121–123. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12680-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Schubert M, Cruickshanks K, Klein B, Klein R, Nondahl D. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:2307–2312. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty J, Rolls ET, Francis S, Bowtell R, McGlone F. Representation of pleasant and aversive taste in the human brain. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85(3):1315–1321. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty J, Rolls ET, Francis S, Bowtell R, McGlone F, Kobal G, Renner B, Ahne G. Sensory-specific satiety-related olfactory activation of the human orbitofrontal cortex. Neuroreport. 2000;11(2):399–403. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002070-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JP, Buchanan TW, Seymour B, Dolan RJ. Predictive neural coding of reward preference involves dissociable responses in human ventral midbrain and ventral striatum. Neuron. 2006;49(1):157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JP, Deichmann R, Critchley HD, Dolan RJ. Neural Responses during Anticipation of a Primary Taste Reward. Neuron. 2002;33(5):815–826. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H. Gustatory cortex of primates: anatomy and physiology. Neurosci Res. 1994;20(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal GK, Pal P, Raj SS, Mohan M. Modulation of feeding and drinking behaviour by catecholamines injected into nucleus caudatus in rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;45(2):172–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannacciulli N, Del Parigi A, Chen K, Le DS, Reiman EM, Tataranni PA. Brain abnormalities in human obesity: A voxel-based morphometric study. Neuroimage. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso S, Johnson DL, Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Watkins GL, Ponto LL, Hichwa RD. Cerebral blood flow changes associated with attribution of emotional valence to pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral visual stimuli in a PET study of normal subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1618–1629. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Faulk ME. The insula. Further observations on its function. Brain. 1955;78(4):445–470. doi: 10.1093/brain/78.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard TC, Hamilton RB, Morse JR, Norgren R. Projections of thalamic gustatory and lingual areas in the monkey, Macaca fascicularis. J Comp Neurol. 1986;244(2):213–228. doi: 10.1002/cne.902440208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard TC, Macaluso DA, Eslinger PJ. Taste perception in patients with insular cortex lesions. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113(4):663–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(2):676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Rolls ET, Rowe EA, Sweeney K. Sensory specific satiety in man. Physiol Behav. 1981;27(1):137–142. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. Central Taste Anatomy and Neurophysiology. In: Doty RL, editor. Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation. New York: Dekker; 1995. pp. 549–573. [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. The Orbitofrontal Cortex and Reward. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10(3):284–294. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. Convergence of sensory systems in the orbitofrontal cortex in primates and brain design for emotion. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004a;281(1):1212–1225. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. Smell, taste, texture, and temperature multimodal representations in the brain, and their relevance to the control of appetite. Nutr Rev. 2004b;62(11 Pt 2):S193–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00099.x. discussion S224-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Baylis LL. Gustatory, olfactory, and visual convergence within the primate orbitofrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1994;14(9):5437–5452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05437.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Grabenhorst F, Margot C, da Silva MA, Velazco MI. Selective Attention to Affective Value Alters How the Brain Processes Olfactory Stimuli. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008 doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Kringelbach ML, de Araujo IE. Different representations of pleasant and unpleasant odours in the human brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18(3):695–703. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Rolls BJ, Rowe EA. Sensory-specific and motivation-specific satiety for the sight and taste of food and water in man. Physiol Behav. 1983;30(2):185–192. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Sienkiewicz ZJ, Yaxley S. Hunger Modulates the Responses to Gustatory Stimuli of Single Neurons in the Caudolateral Orbitofrontal Cortex of the Macaque Monkey. Eur J Neurosci. 1989;1(1):53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP, Zald D, Versace R, Costes N, Lavenne F, Koenig O, Gervais R. Emotional Responses to Pleasant and Unpleasant Olfactory, Visual, and Auditory Stimuli: a Positron Emission Tomography Study. J Neurosci. 2000;20(20):7752–7759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07752.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TR. Brain Mechanisms of Sensation. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1981. Brainstem and forebrain involvement in the gustatory neural code; pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Scott TR, Giza BK. Issues of gustatory neural coding: where they stand today. Physiol Behav. 2000;69(1-2):65–76. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TR, Plata-Salaman CR. Taste in the monkey cortex. Physiol Behav. 1999;67(4):489–511. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TR, Plata-Salaman CR, Smith VL, Giza BK. Gustatory neural coding in the monkey cortex: stimulus intensity. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65(1):76–86. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TR, Verhagen JV. Taste as a factor in the management of nutrition. Nutrition. 2000;16(10):874–885. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TR, Yan J, Rolls ET. Brain mechanisms of satiety and taste in macaques. Neurobiology. 1995;3:281–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TR, Yaxley S, Sienkiewicz ZJ, Rolls ET. Gustatory responses in the frontal opercular cortex of the alert cynomolgus monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56(3):876–890. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.3.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Gregory MD, Mak YE, Gitelman D, Mesulam MM, Parrish T. Dissociation of neural representation of intensity and affective valuation in human gustation. Neuron. 2003;39(4):701–711. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00467-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Jones-Gotman M, Dagher A. Feeding-induced dopamine release in dorsal striatum correlates with meal pleasantness ratings in healthy human volunteers. Neuroimage. 2003;19(4):1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Zald DH, Jones-Gotman M, Zatorre RJ, Pardo JV, Frey S, Petrides M. Human cortical gustatory areas: a review of functional neuroimaging data. Neuroreport. 1999;10(1):7–14. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199901180-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Zatorre RJ, Dagher A, Evans AC, Jones-Gotman M. Changes in brain activity related to eating chocolate: From pleasure to aversion. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 9):1720–1733. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.9.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Zatorre RJ, Jones-Gotman M. Increased intensity perception of aversive taste following right anteromedial temporal lobe removal in humans. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 8):1566–1575. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.8.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Gregory MD, Mak YE, Gitelman D, Mesulam MM, Parrish T. Dissociation of neural representation of intensity and affective valuation in human gustation. Neuron. 2003;39:701–711. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00467-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetter MS, Smeets PAM, de Graaf C, Viergever MA. Representation of sweet and salty taste intensity in the brain. Chemical Senses. 2011 doi: 10.1039/chemse/bjq093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Swintosky VL, Plata-Salaman CR, Scott TR. Gustatory neural coding in the monkey cortex: stimulus quality. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66(4):1156–1165. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.4.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Referentially Oriented Cerebral MRI Anatomy, Atlas of Stereotaxic Anatomical Correlations for Gray and White Matter. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Phan KL, Decker LR, Liberzon I. Subjective rating of emotionally salient stimuli modulates neural activity. Neuroimage. 2003;18(3):650–659. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis JD. Orbitofrontal cortex and its contribution to decision-making. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:31–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JS, Gottfried JA, Kilner JM, Dolan RJ. Integrated neural representations of odor intensity and affective valence in human amygdala. J Neurosci. 2005;25(39):8903–8907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods AT, Lloyd DM, Kuenzel J, Poliakoff E, Dijksterhuis GB, Thomas A. Expected taste intensity affects response to sweet drinks in primary taste cortex. Neuroreport. 2011 Jun 11;22(8):365–9. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283469581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaxley S, Rolls ET, Sienkiewicz ZJ. The responsiveness of neurons in the insular gustatory cortex of the macaque monkey is independent of hunger. Physiol Behav. 1988;42(3):223–229. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaxley S, Rolls ET, Sienkiewicz ZJ. Gustatory responses of single neurons in the insula of the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63(4):689–700. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zald DH, Hagen MC, Pardo JV. Neural correlates of tasting concentrated quinine and sugar solutions. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(2):1068–1075. doi: 10.1152/jn.00358.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zald DH, Lee JT, Fluegel KW, Pardo JV. Aversive gustatory stimulation activates limbic circuits in humans. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 6):1143–1154. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.6.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zald DH, Pardo JV. Emotion, olfaction, and the human amygdala: amygdala activation during aversive olfactory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(8):4119–4124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ, Jones-Gotman M, Rouby C. Neural mechanisms involved in odor pleasantness and intensity judgments. Neuroreport. 2000;11(12):2711–2716. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008210-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]