1. Introduction

There is a substantial body of literature connecting individual, family, and neighborhood level factors to victimization and offending among youth (Gutterman, Cameron, & Staller, 2000; Halliday-Boykins & Graham, 2001; Haynie, Silver, & Teasdale, 2006; Margolin & Gordis, 2000; McNulty & Bellair, 2003; Overstreet, 2000; Smith-Khur, Iachan, Scheidt, Overpeck, Gabhainn, Pickett, et al., 2004; Valois, MacDonald, Bretous, Fischer, & Drane, 2002). Yet, few studies have examined all of these simultaneously, delineating their individual contributions to victimization and offending (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2010). In addition, the majority of studies that examine victimization do so in terms of direct and/or indirect victimization. Direct victimization is generally operationalized as violence or criminal acts against the person and indirect victimization as exposure to (or witnessing) acts of violence (Anglin, Schwartz & Proctor, 2000; Cauffman, 1998; Cooley-Quille, Boyd, Frantz, & Walsh, 2001; Kuther & Wallace, 2003; Crouch, Hanson, Saunders, Kilpatrick, & Resnick, 2000; Haynie, & Payne, 2006; Margolin, & Gordis,; Rosenthal, 2000; Muller, Goebel-Fabbri, Diamond, & Dinklage, 2000; Overstreet, 2000; Singer, Flannery, Singer & Wester, 1995; Shakoor and Chalmers, 1991; Song & Lunghofer, 1995; Wilson & Rosenthal, 2003;Valois et al. 2002). This study expands the definition of victimization to include five distinct categories. Direct victimization captures both (1) personal and (2) property victimization. Likewise, indirect victimization is more broadly defined to capture exposure to violence separately within (1) the neighborhood, (2) family, and (3) among close friends/peers), and further includes simply having knowledge of an event (i.e., knowing someone next door was brutally murdered).

Herein, this paper is one in a series of three that reports findings from a larger study that simultaneously examined individual, family and neighborhood level predictors of victimization and offending among young men using path analysis. Variables for each level within the full model were selected based on previous relationships found in the literature. Findings related to family level predictors (specifically, parental monitoring, parental support, socioeconomic status and family structure) victimization (direct and vicarious) and offending over time are reported in this study. Studies have previously examined family-level predictors in relation to youth victimization and offending including family structure, SES, (Baumer, Horney, Felson and Lauritsen (2003); Beyers, Loeber, Wikstrom & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2001; Bottoms, 2006; Crouch et al., 2000; Demuth, & Brown, 2004; Flowers, Lanclos & Kelly, 2002; Haynie, Silver, & Teasdale, 2006; Kalff, Kroes, Vles, Hendriksen, Feron, & Steyaert, et al., 2001; Lauritsen, 2003; McNulty, & Bellair, 2003; Wikstrom & Loeber, 2000) parental monitoring and supervision (Barnes et al., 1992; Dishion and Loeber, 1985; Osgood & Anderson, 2004; Valois et al. 2002), and maternal support (Mack, Leiber, Featherstone, & Monserud, 2007). Their individual and combined effects on different types of victimization and offending remain unclear. In an effort to fill this gap, family structure, SES, parental monitoring and parental support were included in the model as family level risk factors with the aim of identifying which of these have better predictive power with regard to different types of victimization and total offending, if any.

1.1 Family Risk Factors

The relationship between parental monitoring, parental support, SES, family structure, victimization, and offending are dependent on the specific features of each, how they occur, and interact. Therefore, A better understanding of these aspects contribute to a more accurate picture of what youth actually experience; these findings inform the development of appropriately targeted prevention and intervention strategies that can consider the cumulative nature of these variables. Although other family level risk factors may relate to victimization and offending among youth, the scope of this study is limited to variables assessed within the initial study from which this current analysis is derived. Therefore, the literature examining family level risk factors are also limited in the same manner and include parental monitoring, parental support, family structure, and SES.

1.1.1. Parental monitoring and support

Within related literature parental monitoring is defined in a manner congruent with that operationalized in the BLSYM and thus employed herein; this term refers to having general knowledge of youth’s whereabouts and peer associations by parental figures (Barnes, Welte, Hoffman & Dintcheff, 2005). Similarly, parental support refers to youth’s assessment of their level of attachment or closeness to their primary parental figures. Although this study assesses levels of parental monitoring and support separately, the vast majority of literature of this nature uses these constructs together and with a good deal of consistency. Parental monitoring (Barnes, Welte, Hoffman & Dintcheff, 2005; Johnson, Giordano, Manning & Longmore, 2011; Dishion and Loeber, 1985; Osgood & Anderson, 2004; Valois et al., 2002) and parental support (Ordonez, 2011; Mack, Leiber, Featherstone, & Monserud, 2007) are consistently associated with lower offending in young adulthood. Yet, it is less definitive in demonstrating how this influences youth victimization (Overstreet & Dempsey, 1999). It has been argued that a family’s capacity to provide monitoring and support is disrupted or incapacitated as safety and survival in violent environments take precedence over basic parenting (Lorion & Saltzman, 1993). Additionally, research suggests that parental support may actually moderate the effects of exposure to community violence (Overstreet, Dempsey, Graham & Morley, 1999).

1.1.2. Family structure

Family structure refers to the configuration of the family unit and may include the presence of one or both biological or other parental figures in the home. From this definition, literature that explores family structure as it relates to victimization and offending does so based on the premise that a two parent home affords youth with two adults to provide monitoring, support, and two incomes thus increasing the likelihood of higher SES (Demuth, & Brown, 2004; Lauritsen, 2003; McNulty, & Bellair, 2003; Valois et al. 2002). Similar to the inextricability of race and SES, studies that focus on family structure are linked to income; however, this factor also recognizes the emotional demands of parenthood. Single-parent families are more likely to have a difficult time meeting youth’s monitoring and support needs while attending to financial demands that often include long work hours away from home (McNulty, & Bellair, 2003). From this perspective, it is easy to see the association between risk factors for various types of victimization and subsequent offending. Youth living in single parent families have an overall risk for violent victimization that is about three times higher than their two parented counterparts (Lauritsen, 2003), are significantly more delinquent (Demuth, & Brown, 2004), and are almost twice as likely (40.8 versus 19.9 per 1000) to become a victim of neighborhood violence (Lauritsen, 2003).

1.1.3. Family SES

Similar to other family risk factors discussed previously, a clear understanding of the role of SES in victimization and offending is muddied by other interrelated individual and family level factors (Markowitz, 2003). For example, it has been found that the likelihood for both direct and vicarious victimization decreased as household income increases for Caucasian youth however, this does not appear to hold true for African American or Hispanic youth (Crouch et al. 2000). Therefore, the role of SES may not be able to be separated from race as non-whites may experience higher rates of victimization regardless of income. Nonetheless, from a neighborhood level, low SES is associated with direct and vicarious victimization, affiliation with violent peers, behavioral problems, and youth offending (Haynie, Silver, & Teasdale, 2006; Kalff, Kroes, Vles, Hendriksen, Feron, & Steyaert, et al., 2001; Wikstrom & Loeber, 2000). Therefore, it is included in the study as an important family level risk factor.

1.2 Study hypotheses

This study aims to test the following hypotheses; (1) low parental monitoring will significantly predict direct and vicarious victimization, (2) low parental monitoring will significantly predict offending at Wave 1 but not Wave 2 (based on increased independence with the increased age of participant), (3) Low parental support will significantly predict personal victimization, (4) low parental support will significantly predict offending at Wave 1 and Wave 2, (5) family structure will significantly predict both victimization and offending, (6) low SES will significantly predict personal victimization and vicarious victimization by exposure to violence through the neighborhood, family and peers.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

The current study is a secondary analysis utilizing data from two waves of the Buffalo Longitudinal Study of Young Men (BLSYM), from the city of Buffalo, New York. The BLSYM is a five-year panel study designed to examine multiple causes of adolescent substance abuse and delinquency (See Zhang, Welte & Wieczorek, 2001 for detailed description). Wave 1 and Wave 2 data were utilized to develop a sophisticated model that examined offending over time. Wave1 data was obtained from 1992 to 1993, and Wave 2 data was collected from 1994 to 1995 (Zhang et al., 2001). The BLSYM was supported by a five-year grant funded through the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (# RO1 AA08157).

2.2. Study Participants

The BLSYM study included a general population-based sample of young males (N=625) between the ages of 16 and 19 at Wave 1. Eligible participants were required to have a parent or caregiver (i.e., the main caregiver) participate in Wave 1 of the study. All measures were based on adolescent and parent/caregiver self-reports (Zhang et al., 2001). Recruitment was a detailed, multi-step process as reported in Welte and Wieczorek (1998). Face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained research assistants at the Research Institute on Addictions at The University of Buffalo (Welte, Barnes, Hoffman, Wieczorek & Zhang, 2005).

Repeated interviews were conducted with the primary respondents using the same interview instrument for each subsequent wave. The study utilized an 18-month interval schedule to allow for the examination of major developmental influences of all the factors. The retention rate of participants from Wave 1 to Wave 2 was 96% (Zhang et al., 2001).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Independent Variables

2.3.1.1. Parental monitoring

Parental monitoring was measured using items from the existing Parental Monitoring Scale developed by Barnes and Farrell (1990) and supported by previous theory and research on adolescent socialization processes (Barnes, et al., 2005). To anchor responses to a particular time period, primary respondents were asked to think about the time they were approximately 16 years. They were asked a series of questions related to whether their parent(s)/guardian(s) were aware of their activities during that time. Sample items include: (1) “How often did you tell your parents where you were going to be after school?” (2) “How often did you tell your parents where you were going when you went out evenings and weekends?” (3) “How often did you tell your parents who you were going out with?” Responses included; 1=always, 2= most of the time, 3=sometimes, 4=hardly ever, and 5=never. An overall parental monitoring variable was created by computing the mean of the responses to the monitoring items with a higher mean score indicating low parental monitoring.

2.3.1.2. Parental support

Parental support was derived from an eight-item measure also originally developed by Barnes and Farrell (1992). Separate support variables reflected the primary respondent’s perception of their mother and fathers (or caregivers) level of support. The scale measured the frequency of nurturing acts by parents or caregivers such as giving praise or advice. Primary respondents recalled the period of time when they were 16. Sample items include: (1) “When you did something well, how often did your (mother/father/guardian) gave you praise for what you did?” (2) “How much did you rely on them for advice and guidance?” (3) “How often did they give you a hug, kiss or pat on the shoulders?” Responses categories ranged from 1 (always) to 5 (never). The mean of responses was calculated to obtain a measure representing the level of support for each parent/guardian. Mean scores ranged between a minimum of 1, indicating a high level of parental support, and a maximum of 5, indicating a low level of parental support. Alphas for mother and father support measures are .80 and .84 respectively (Barnes & Farrell, 1992).

2.3.1.3. Family structure

Family structure measured which parent(s)/guardian(s) resided in the primary residence of the adolescent respondent. The index was created from a series of questions related to the people residing with the primary respondent. Four variables were derived to reflect family structure: (1) both biological parents living at home, (2) biological mother only, (3) biological mother and a significant other or biological father and a significant other, and (4) other male or female guardian (See Zhang, Welte & Wieczorek, 1999).

2.3.1.4. Family socioeconomic status (SES)

Family SES reflects a computation of mean income and educational level of parent(s)/guardian(s). The SES variable was created by summing across family income and education variables for the parent(s)/guardian(s) and then dividing by the overall mean (See Zhang et al., 2001).

2.3.2. Dependent Variables

This study makes a distinction between two types of victimization: (1) direct and (2) vicarious. The direct measures were adopted from the National Youth Survey (Elliot, Huizinga & Ageton, 1985). They included (a) personal and (b) property victimization. Vicarious measures examined primary respondents exposure to violence in three areas (1) the neighborhood (2) family and (3) among close friends/peers.

2.3.2.1. Direct victimization

2.3.2.1.1. Personal victimization

Personal victimization consists of primary respondent’s real number report of instances in the past twelve months in which they experienced the following: (1) been confronted and had something taken directly from you or an attempt made to do so by force or threatening to hurt you, (2) been sexually attacked or raped or an attempt made to do so, (3) been beaten-up or attacked or threatened with being beat up or attacked by someone (excluding sexual attack or rape).

2.3.2.1.2. Property victimization

Property victimization consists of primary respondent’s real number report of instances in the past twelve months in which they experienced the follow sample items: (1) had something stolen from their house or an attempt to do so, (2) while they weren’t around, had their bicycles stolen or an attempt made to do so, (3) while they weren’t around, had their cars or motorcycles stolen or attempts made to do so (for complete measure see Hartinger-Saunders, Rittner, Wieczorek, Nochajski, & Rine, 2011).

2.3.2.2. Vicarious victimization

As demonstrated by knowledge of indirect crime, vicarious victimization consists of primary respondent’s real number report of events that occurred: in their neighborhood, to their family members, and to their friends or peers; actually witnessing an event was not a prerequisite. Respondent’s event knowledge for all three vicarious measures covered the preceding twelve-month period using a scale with response categories: 1=never, 2=once, and 3=twice or more (Hartinger-Saunders et al., 2011). The resulting real number frequencies of event knowledge taken in sum represent vicarious victimization for (1) neighborhood, (2) family, and (3) friends or peer groups. Larger numbers indicate higher levels of exposure to violence within each discrete category (Hartinger-Saunders et al., 2011).

2.3.2.2.1. Vicarious victimization by exposure to violence in the neighborhood

Vicarious victimization as demonstrated by exposure to neighborhood violence consists of primary respondent’s scaled frequency responses regarding knowledge of someone in their neighborhood being: (1) robbed, (2) seriously assaulted, (3) beat-up, shot or stabbed, (4) sexually assaulted, or (4) threatened with physical harm by someone outside their family.

2.3.2.2.2. Vicarious victimization by exposure to violence in the family

Vicarious victimization as demonstrated by exposure to family violence consists of primary respondent’s scaled frequency responses regarding having knowledge of individuals who lived with them (excluding themselves) being: (1) confronted or had something directly taken from them or an attempt was made to do so, (2) sexually attacked or raped or an attempt made to do so, (3) beaten-up or attacked or threatened with being beaten up or attacked by someone.

2.3.2.2.3. Vicarious victimization by exposure to violence with close friends or in peer group

Vicarious victimization as demonstrated by exposure to friend or peer group violence consists of primary respondent’s scaled frequency responses regarding friends or peers being (1) confronted or had something directly taken from them or an attempt was made to do so, (2) sexually attacked or raped or an attempt made to do so, (3) beaten-up or attacked or threatened with being beaten up or attacked by someone.

2.3.2.3. Total Offending (Wave 1 and 2)

Total offending measures are aggregate frequencies of offending for primary respondents regardless of the seriousness of their offense. This measure, adopted from the National Youth Survey (Elliot, Huizinga & Ageton, 1985), represents the real number report of delinquent acts committed in the preceding twelve-month period. The delinquent acts were quantified from a list of 34 such offences (see Appendix A) (Zhang et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2001; Barnes et al., 1999). Log transformations were used to normalize distributions of total offending as computed in wave two of the BLSYM (Zhang et al., 1999). Analyzed together, the 34 delinquent act items have a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 and internal consistency reliability for the constructed measures ranging from .76 for general delinquency to .49 for minor delinquency (Welte, Zhang & Wieczorek, 2001).

3. Statistical Analysis

Initial data screening and descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS (PASW Statistic 18) software. Table 1 shows the zero order correlations between study variables. Table 2 and Table 3 respectively highlight the primary respondent and family-level sample characteristics. MPlus software, version 5.2 was used for the main path analyses to examine the causal interrelationships between individual, family, and neighborhood study variables in relation to type of victimization and offending in Wave 1 and Wave 2. Tables 4, 5 and 6 contain the all path coefficients for the main analyses.

Table 1. Correlations.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Offending wave 1 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Offending wave 2 | 0.622*** | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Personal victa | 0.410*** | 0.280*** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | Property vict | 0.180*** | 0.085 | 0.181*** | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 5 | Vicarious: familyb | 0.029 | 0.003 | 0.045 | 0.091** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Vicarious: peers | 0.373*** | 0.302*** | 0.271*** | 0.145*** | −0.019 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 7 | Vicarious: neigh | 0.388*** | 0.240*** | 0.174*** | 0.115** | 0.095 | 0.092** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 8 | Neighborhood crime |

0.401*** | 0.223*** | 0.197*** | 0.160*** | 0.080 | 0.155*** | 0.819*** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 9 | Perception of asafety | 0.211*** | 0.118** | 0.133** | 0.090** | 0.069 | 0.055 | 0.466*** | 0.686*** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 10 | Parent monitoring | −0.319*** | −0.251*** | −0.144*** | −0.074 | −0.021 | −0.028 | −0.220*** | −0.258*** | −0.237*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 11 | Single parentc | −0.135** | −0.097 | −0.058 | −0.035 | −0.045 | −0.022 | 0.033 | 0.074 | 0.068 | 0.013 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 12 | Parent/sig. other | 0.058 | 0.075 | −0.004 | 0.018 | 0.085** | 0.032 | 0.071 | 0.067 | 0.082** | −0.021 | −0.363*** | 1.000 | |||||

| 13 | Other living arrange | 0.130** | 0.070 | 0.053 | 0.066 | 0.007 | −0.027 | 0.027 | 0.046 | 0.080** | −0.127** | −0.368*** | −0.282*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 14 | SES | −0.052 | −.004 | 0.019 | −0.020 | 0.002 | 0.107** | −0.159*** | −0.208*** | −0.213*** | 0.137*** | −0.167*** | −0.014 | −0.078 | 1.000 | |||

| 15 | Race | 0.024 | 0.014 | −0.004 | −0.004 | 0.023 | −0.073 | 0.098** | 0.204*** | 0.240*** | −0.096** | 0.112** | 0.016 | 0.127** | −0.185*** | 1.000 | ||

| 16 | Mom support | −0.132** | −0.122** | −0.066 | −0.059 | −0.006 | 0.024 | −0.099** | −0.121** | −0.128** | 0.458*** | 0.080** | −0.032 | −0.093 | 0.070 | 0.092** | 1.000 | |

| 17 | Dad support | −0.095** | −0.091** | −0.039 | −0.041 | −0.081** | 0.022 | −0.101** | −0.166*** | −0.108** | 0.295*** | −0.047 | −0.084** | 0.020 | 0.111** | 0.065 | 0.319** | 1.000 |

Notes:

Personal vict= personal victimization.

Vicarious: family =Vicarious exposure to violence through the family; same with peers and neighborhood. Variables 12 through 14 describe family structure.

p< .001 level

p<.05 level

Table 2. Individual-level Sample Characteristics (n=625).

| Characteristic | n | Mean (SD) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (at time of wave 1) | 17.3 (1.14) | ||

| 20 | 4 | .6 | |

| 19 | 127 | 20.3 | |

| 18 | 155 | 24.8 | |

| 17 | 159 | 25.4 | |

| 16 | 175 | 28.0 | |

| 15 | 5 | .8 | |

| Race | |||

| White* | 290 | 47.3 | |

| Black* | 289 | 47.1 | |

| Asian | 1 | .2 | |

| American Indian | 13 | 2.1 | |

| Black and White | 9 | 1.5 | |

| Mixed Other | 11 | 1.8 | |

| Education | |||

| Currently in school | 452 | 72.3 | |

| Not currently in school | 173 | 27.7 |

Note:

Non-Hispanic

Table 3. Family- Level Sample Characteristics (n=625).

| Characteristic | n | Mean (SD) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Biological Parents | |||

| Mother | 617 | 41.9 (5.93) | 98.0 |

| Father | 590 | 44.4 (7.38) | 94.4 |

| Race of Family | |||

| White | 282 | 45.1 | |

| Black | 278 | 44.5 | |

| Hispanic | 44 | 7.0 | |

| Other/Unknown | 21 | 3.4 | |

| Family Structure | |||

| Both Parents | 149 | 23.8 | |

| Mom only | 201 | 32.2 | |

| Mom/man or dad/woman | 136 | 21.8 | |

| Other | 139 | 22.2 |

Table 4. Initial Model: All Exogenous Variables on Direct Victimization Variables.

| Estimate | .E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed P-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Vic On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.121 | 0.083 | 1.467 | 0.142 |

| Perception Safe | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.335 | 0.737 |

| Parent Monitor | −0.100 | 0.044 | −2.254 | 0.024** |

| Single Parent | −0.050 | 0.038 | −1.309 | 0.191 |

| SES | 0.026 | 0.040 | 0.664 | 0.506 |

| Race | −0.015 | 0.040 | −0.382 | 0.702 |

| Mom Support | 0.000 | 0.044 | −0.007 | 0.995 |

| Dad Support | 0.004 | 0.041 | 0.087 | 0.931 |

| Property Vic | 0.117 | 0.038 | 3.058 | 0.002** |

| Vicarious: Family | 0.025 | 0.038 | 0.646 | 0.518 |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.228 | 0.038 | 5.972 | <.001*** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | −0.007 | 0.068 | −0.109 | 0.913 |

| Property Vic On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.248 | 0.085 | 2.918 | 0.004** |

| Perception Safe | −0.049 | 0.056 | −0.888 | 0.375 |

| Parent Monitor | −0.024 | 0.046 | −0.513 | 0.608 |

| Single Parent | −0.037 | 0.040 | −0.933 | 0.351 |

| SES | −0.015 | 0.041 | −0.357 | 0.721 |

| Race | −0.023 | 0.042 | −0.544 | 0.586 |

| Mom Support | −0.030 | 0.046 | −0.652 | 0.515 |

| Dad Support | −0.007 | 0.042 | −0.155 | 0.876 |

| Vicarious: Family | 0.085 | 0.039 | 2.179 | 0.029** |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.131 | 0.040 | 3.267 | 0.001** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | −0.106 | 0.070 | −1.505 | 0.132 |

p<.001

p<.05

p<.10

Table 5. Initial Model: All Exogenous Variables on Vicarious Victimization Variables.

| Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed P-Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vicarious: Peer On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.082 | 0.085 | 0.966 | 0.334 |

| Perception Safe | −0.029 | 0.055 | −0.525 | 0.600 |

| Parent Monitor | −0.035 | 0.046 | −0.761 | 0.447 |

| Single Parent | −0.006 | 0.040 | −0.147 | 0.883 |

| SES | 0.126 | 0.040 | 3.121 | 0.002** |

| Race | −0.085 | 0.041 | −2.065 | 0.039** |

| Mom Support | 0.054 | 0.045 | 1.201 | 0.230 |

| Dad Support | 0.027 | 0.042 | 0.650 | 0.515 |

| Vicarious: Family | −0.036 | 0.039 | −0.927 | 0.354 |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.171 | 0.069 | 2.466 | 0.014** |

| Vicarious: Family On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | −0.034 | 0.087 | −0.393 | 0.695 |

| Perception Safe | 0.045 | 0.057 | 0.800 | 0.424 |

| Parent Monitor | 0.018 | 0.047 | 0.384 | 0.701 |

| Single Parent | −0.054 | 0.041 | −1.339 | 0.181 |

| SES | 0.022 | 0.042 | 0.528 | 0.598 |

| Race | 0.025 | 0.042 | 0.580 | 0.562 |

| Mom Support | 0.027 | 0.046 | 0.584 | 0.559 |

| Dad Support | −0.090 | 0.043 | −2.119 | 0.034** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.102 | 0.071 | 1.433 | 0.152 |

| Vicarious: Neigh On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.944 | 0.023 | 40.336 | <.001*** |

| Perception Safe | −0.174 | 0.031 | −5.589 | <.001*** |

| Parent Monitor | −0.027 | 0.026 | −1.009 | 0.313 |

| Single Parent | −0.021 | 0.023 | −0.934 | 0.350 |

| SES | −0.011 | 0.023 | −0.457 | 0.648 |

| Race | −0.056 | 0.024 | −2.372 | 0.018** |

| Mom Support | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.536 | 0.592 |

| Dad Support | −0.004 | 0.024 | −0.168 | 0.867 |

p<.001

p<.05

p<.10

Table 6. Initial model: All Exogenous variables on Offending (Wave 2 & Wave 1).

| Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-tailed P-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offending Wave 2 On | ||||

| Offending Wave 1 | 0.571 | 0.036 | 15.884 | <.001*** |

| Neigh Crime | −0.089 | 0.069 | −1.287 | 0.198 |

| Perception Safe | 0.010 | 0.044 | 0.217 | 0.829 |

| Parent Monitor | −0.060 | 0.038 | −1.599 | 0.110* |

| Single Parent | −0.012 | 0.032 | −0.369 | 0.712 |

| SES | 0.018 | 0.033 | 0.551 | 0.582 |

| Race | 0.019 | 0.033 | 0.580 | 0.562 |

| Mom Support | −0.015 | 0.036 | −0.426 | 0.670 |

| Dad Support | −0.021 | 0.034 | −0.614 | 0.539 |

| Personal Vic | 0.018 | 0.035 | 0.528 | 0.597 |

| Property Vic | −0.038 | 0.032 | −1.179 | 0.238 |

| Vicarious: Family | −0.014 | 0.031 | −0.437 | 0.662 |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.084 | 0.034 | 2.450 | 0.014** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.054 | 0.056 | 0.962 | 0.336 |

| Offending Wave 1 On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.268 | 0.068 | 3.919 | <.001*** |

| Perception Safe | −0.103 | 0.044 | −2.313 | 0.021** |

| Parent Monitor | −0.215 | 0.036 | −5.890 | <.001*** |

| Single Parent | −0.133 | 0.032 | −4.195 | <.001*** |

| SES | −0.033 | 0.033 | −1.016 | 0.309 |

| Race | −0.008 | 0.033 | −0.244 | 0.807 |

| Mom Support | 0.026 | 0.036 | 0.722 | 0.471 |

| Dad Support | −0.006 | 0.034 | −0.190 | 0.849 |

| Personal Vic | 0.244 | 0.033 | 7.467 | <.001*** |

| Property Vic | 0.034 | 0.032 | 1.070 | 0.284 |

| Vicarious: Family | −0.014 | 0.031 | −0.435 | 0.663 |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.240 | 0.033 | 7.319 | <.001*** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.077 | 0.056 | 1.367 | 0.172 |

p<.001

p<.05

p<.10

3.1. Descriptive statistics

At the time of Wave 1, primary respondents ranged in age from 16 to 19 years old (M=17.3, SD=1.14). The sample was primarily White, non-Hispanic (47.3%) and Black, non-Hispanic (47.1%) (See Table 2). Twenty-three percent (n=149) of primary respondents lived with both biological parents with the highest percentage (n=201, 32.2%) living in single parent (mother only) homes. Twenty-two percent (n=136) were living with either mother or father and a significant other and the remaining 22.2% (n=139) resided with some other person (See Table 3). Both biological parents were similar in age with the mean age of biological mothers (n=617) and fathers (n=590) 42 and 44 respectively. Sixty-one percent of fathers (n=366) and 52.9% of mothers (n=324) attained either a high school diploma or some high school education. Fifty-four percent of the family respondents reported a yearly income less than $20,000 and 45% (n=164) reported making between 20-$40,000 a year.

Parental monitoring for this sample was moderate (M=2.55, SD .83). Forty-eight percent of primary respondents indicated their parents either sometimes, hardly ever or never knew where they were after school. Over half of the respondents (51.2%) indicated they told their parents where they were going at night, yet only 45.3% told their parent whom they were with. In addition, the majority of respondents indicated they sometimes (35.2%), hardly ever (19.7%) or never (15%) talked with their parents about their plans with friends. Although parents may not always know who primary respondents were with or what the plans were, 78.5% of respondents reported their parents did ask where they were going and 77% reported their parents expected a call if plans were to change most of the time or always.

The overall mean level of parental support by mothers (M=3.67, SD.79) was slightly less than the level of support provided by fathers (M=3.16, SD.87). Fathers were slightly less likely than mothers to give praise to the primary respondent when they did something well. Primary respondents were more likely to go to their mothers for advice than to their fathers. There is a marked difference between the degree to which mothers and fathers utilized physical gestures (i.e. hug, kiss, pat on the shoulder) as a means of support. When asked how often they would discuss personal problems with each parent, 40.4% (n=252) reported they hardly ever or never discuss personal problems with their mother compared to 59.1% (n=293) hardly ever or never discussing personal problems with their father.

Almost half (46.8%) of the young male sample reported being personally victimized at least one or more times and 56% reported being a victim of property crime one or more times. Regarding vicarious victimization, 82.9% reported no knowledge of violence against family members compared to 40% having knowledge of peers being beat up or attacked. When broken down between violent and non-violent offending among respondent’s, 55.8% reported committing more than one violent offense in the past twelve months (31% committed over 5) (see Appendix A). In contrast, 76.5% of the sample reported committing two or more non-violent offenses in the last twelve months (of which 62% committed over 5).

3.2 Path analyses

The second set of analyses considered relationships between all study variables from a causal standpoint. Wave 1 measures were used to predict Wave 1 and 2 offending. Based on existing literature, the model presumed that Wave 1 offending was a function of factors that preceded offending to some degree. For example, it was expected that the individual, family, and neighborhood factors were predictors of offending.

A path analytic approach was applied to the data. The Chi-Square, Comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) were used as the fit indices (See Hartinger-Saunders, et al., 2011). The procedure used for estimation of the path model was maximum likelihood. Initial path models included those from the exogenous to the endogenous, and outcome variables (See Tables 4-6).

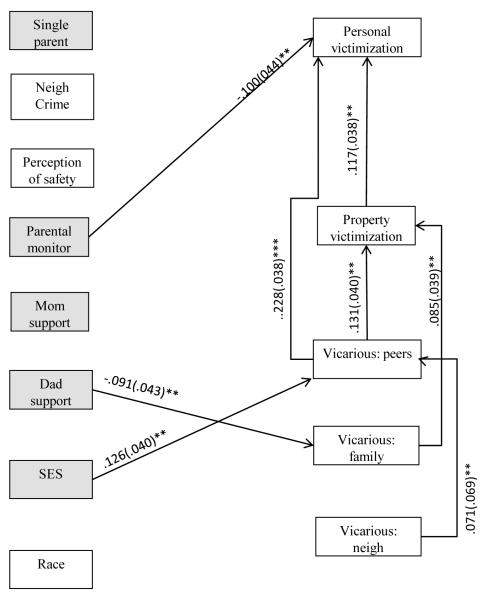

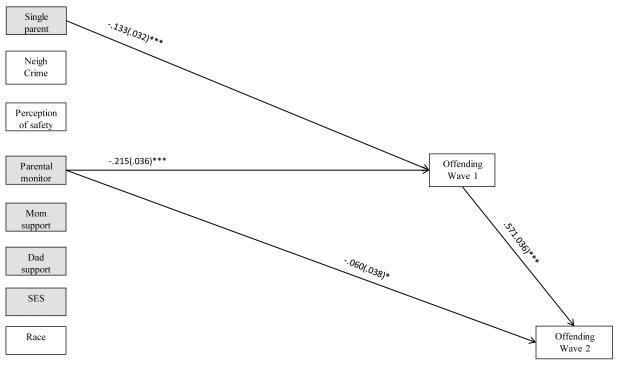

Results from the initial regressions were used to identify all non-significant pathways until a final best fitting model was obtained (Hartinger-Saunders et al., 2011). The final model was determined by a non-significant Chi-Square, CFI and TLI both over .95, RMSEA below .05, and WRMR below .8. The fit for the final revised model was Chi-Square = 52.18, df = 92, n = 625, p = .892; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.01; RMSEA = .000; WRMR = .024 (Hartinger-Saunders et al., 2011). Results for this analysis as they relate to family level predictors are shown in Figure 1 and 2. It should be noted that parental monitoring and family structure (single parent) are correlated (See Table 1).

Figure 1.

Path Diagram for Family Level Variables and Victimization, ***p<.001, **p<.05, *p<.10

Figure 2.

Path Diagram for Family Level Variables and Offending, ***p<.001, **p<.05, *p<.10

3.2.1. Direct victimization

Parental monitoring (p<.05) was a significant predictor of personal victimization (see Table 4) (See Figure 1). 3.2.2. Vicarious Victimization. Father’s support was a significant predictor (p<.05) of vicarious victimization by exposure to violence through the family. SES was a significant predictor (p<.05) of vicarious victimization by exposure to violence through peers. (See Table 5) (See Figure 1).

3.2.3. Offending

Parental monitoring (p<.001), single parenthood (mother only) (p<.001), were significantly associated with Wave 1 offending (see Table 6) (See Figure 2). Parental monitoring was a significantly predictor of offending at Wave 2 (p<.10).

4. Discussion

The model suggests multiple pathways wherein young men become victims and offenders. Overall, the study affirms possible causal relationships between certain family level variables (i.e., parental monitoring, parental support, SES), and victimization. Additionally, it highlights pathways between family level variables (i.e., parental monitoring and family structure) and offending. Each has unique predictive power with regard to type of victimization, and offending across waves. Since this is an all-male sample, caution must be taken when interpreting results as a female sample may yield different findings.

Authors hypothesized that low parental monitoring would predict victimization as this leaves young males with more unsupervised time, exposure to more opportunities, and an increased risk for victimization. Data supported this hypothesis. Findings support previous research that suggest increased parental monitoring and support decreases youth offending Barnes & Farrell, 1992; Barnes, Welte, Hoffman & Dintcheff, 2005; Johnson, Giordano, Manning & Longmore, 2011; Dishion and Loeber, 1985; Osgood & Anderson, 2004; Valois et al., 2002), however, this current analysis highlights the vital role parental monitoring alone may play in protecting youth from personal victimization specifically. Furthermore, authors hypothesized that low parental monitoring would predict offending at Wave 1 (but not Wave 2) based on the premise that once a person has offended, parents may be more likely to increase monitoring, at least in the short term (as more of a reactive response). Additionally, as young men get older and more independent, parents may be less likely to monitor their behavior or have less control over this element. Data supported this hypothesis affirming a significant relationship between parental monitoring and offending at Wave 1 (p<.001), yet not Wave 2. This finding supports existing literature that suggests the strong influence parental monitoring has on curbing youth crime (Barnes & Farrell, 1992; Barnes, Welte, Hoffman & Dintcheff, 2005; Johnson, Giordano, Manning & Longmore, 2011; Dishion and Loeber, 1985; Osgood & Anderson, 2004; Valois et al., 2002). Therefore, engaging families in interventions that incorporate structured and consistent monitoring plans warrant attention. This also provides support for parental involvement in punitive approaches such as placing young men on probation or placing them outside of their home. Without the expectation that parents will continue their role in monitoring youth despite outside supervision by probation and placement agencies, interventions may prove ineffective long-term.

Authors hypothesized low levels of parental support to be associated with higher levels of personal victimization based on the premise that young men who lack parental support may seek affiliation or group memberships outside of the family unit in an effort to belong or feel supported. In doing so, these youth may identify and connect with poor role models (Akers, Krohn, Lanza-Kaduce, & Radosevich, 1979; Simons et al., 2004) or find themselves with peer groups or gangs that expose them to more opportunities for victimization and crime. Findings did not support this hypothesis. Additionally, authors hypothesized a negative relationship between parental support and offending based on the aforementioned premise, which suggests that males raised in supportive and nurturing environments will be less likely to look outside the family for approval and group affiliation with delinquent peers (Simons et al., 2004). Data did not support this.

It was hypothesized that family structure would predict both victimization and offending since single parent homes, by definition, have less opportunity for parental monitoring (i.e. time spent working, caring for younger siblings, etc.). Additionally, young males in single parent, female head of households may lack the support and guidance of a male role model. Therefore, youth may seek role models outside of the family and in their neighborhood such as in peers and gang affiliates.

Although data did not indicate a significant relationship between family structure and victimization among the all-male sample, findings did indicate a highly significant relationship between family structure and offending at Wave 1. Interestingly, some family structure variables (both parents, a parent and a significant other, and other family structure) were not significant in the saturated model. Therefore, they were not included in the final model. This reinforces the benefit that healthy, intact families bring to parenting in terms of raising youth in safe environments free from victimization and offending. Having the capacity (more than one parent) to supervise and monitor youth can decrease the likelihood of youth engaging in illegal or anti-social behavior.

It was hypothesized that lower SES would predict higher personal victimization as well as vicarious victimization by exposure to violence within the neighborhood, within the family, and among friends or peers. This hypothesis was based on the premise that families with a lower SES have less opportunity regarding employment, neighborhood and school selection, home ownership, and other related aspects of their lives resulting in families residing in poorer neighborhoods, thus increasing the risk for exposure to violence (See Kuther and Wallace, 2003). Data did not fully support this; SES was only a significant predictor of vicarious victimization by exposure to violence among peers suggesting that young men tend to associate with peers who are of similar SES and who may not necessarily reside in the same neighborhood.

When considering the predictive importance of parental monitoring and family structure, it should be noted that parental SES might be a factor indirectly influencing both. For example, over a half of the respondent’s parent/guardians yearly income was under $20,000 with 30% of them making less than $10,000 a year. This means that the majority of the respondent’s parents/guardians are working low wage jobs to make ends meet with little time to nurture let alone monitor youth.

4.1. Study limitations

Findings are not generalizable to all youth as this was an all-male sample. Even though measures were retrospective self-reports, consent procedures, the research setting for the interview, anchored time frames and specified methods for protecting confidentiality of the participants, were all procedures designed to optimize the validity of these measures (Hartinger-Saunders, et al., 2011). Additionally, parental monitoring and parental support measures were obtained from the primary respondent. Utilizing responses from the both, the parent/caregiver and the primary respondents may have yielded different results.

4.2. Implications for Practice

The identification of multiple pathways to victimization and offending allows researchers and practitioners to target change at multiple levels by engaging families and entire communities in a collective response to youth victimization and offending. The rationale for doing so allows for the development of more effective, strength based, prevention and intervention strategies for this population.

The significance of parental monitoring highlights the vital role parents have in not only establishing values and moral parameters for youth, but also in monitoring their behavior. It is critical for parents to engage in regular dialogue to ensure youth are clear on parental expectations as well as the consequences for failing to adhere to rules and expectations. In addition, parents have to commit to following through on monitoring youth’s adherence to rules and expectations and providing appropriate consequences. Establishing and communicating expectations are critical. Likewise, spending time getting to know youth is critical in the early identification of behaviors that may signal trouble. If parents have little insight into youth’s baseline behavior, their ability to detect problems is diminished. Too often, we hear of tragic stories where a youth has fatally shot classmates in an act of rage. It is common for parents, neighbors, and peers to report dismay citing they had no indication the youth was troubled. Identifying specific and normative behaviors of youth allows parents to be more proactive in sensing when something is not typical. Parental monitoring is the tool to assist in performing these critical parenting tasks.

Unfortunately, as divorce rates climb above 50%, the structure of families change, and more parents enter the workforce, the role of parental monitoring is compromised. Parental monitoring should be considered a protective factor or mediator in averting victimization and disrupting offending behavior. It is critical to build prevention and intervention models that aim to empower parents in this role. Prevention and intervention models for youth services that emphasize educating parents on the importance of parental monitoring as well as provide tangible skills on how to monitor youth effectively may prove to be the most cost effective and sustainable. For those already involved with agencies due to offending (i.e. probation, family court, etc.) monitoring should be a shared responsibility, yet primary responsibility should always fall with parents. For example, parents cannot rely on probation officers to monitor youth behavior. It will require an honest partnership between parents and agencies in order to reduce the likelihood of recidivism.

The literature consistently links family structure to an increased risk for violent victimization (Lauritsen, 2003; Sampson & Groves, 1989). This study also revealed a positive, significant (yet moderate) relationship between family structure and offending. Therefore, the absence of one or both biological parents in the home places young men at a greater risk. This should signal to service providers that engaging both parents in youth services, regardless of whether or not parents reside together in the same home, is critical. Professionals responsible for the treatment and/or care of this population have to rethink the role of parents. To do this, service providers will need to increase their skills around managing conflict and/or working with resistant clients. The success of prevention and intervention efforts for youth may hinge on how well we facilitate the relationships between parents and caregivers and how effectively we educate and empower them in their role as parents.

4.3 Future directions for practice

In order to be effective in today’s familial landscape as described above, the concept of parental monitoring needs to evolve, shifting sole responsibility of the parents to a collective partnership with parents, neighbors, communities, teachers, service providers, etc. Additionally, Family Courts that move away from adjudicating and punishing youth with little or no accountability on the part of parents will make a greater impact. Policies and laws need to change to include participation by both parents when possible. In situations where parents are divorced, skill building around parental monitoring and support from outside of one’s primary residence is warranted. In addition, rethinking the utilization of placements outside of the home as a form of discipline should be reconsidered (i.e., foster care, group homes, residential settings, etc.). The nature of this intervention undermines the importance of parental monitoring and essentially strips parents of their ability to fulfill this critical role. Mezzo and macro level interventions should be developed to incorporate community building and mentoring for youth in an effort to create a sense shared responsibility for parental monitoring in order to raise healthy young people and grow healthy communities.

Cleary, there is no silver bullet to curb youth offending, but if we back track and identify elements along potentially causal pathways that significantly contribute to victimization and offending, we can develop better interventions targeting change at multiple levels, not simply the individual victim or offender. When we enlist multiple players in the treatment models for youth, change will be more likely and sustainable.

Highlights.

Utilized path analysis.

Parental monitoring was a significant predictor of personal victimization

Single parenthood significantly predicted offending

Father support and SES predicted vicarious victimization

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author would like to acknowledge and thank Dennis Frazier for his ongoing support along her career path. His shared passion for the field and desire to make changes in how we provide services to families and youth directly inspired her line of on-going research.

Research support

The Buffalo Longitudinal Study of Young Men was supported by a five-year grant funded through the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (# RO1 AA08157).

APPENDIX

Delinquency: Total Delinquent Acts

Thirty-four items asking how many times the respondent committed the following delinquent acts in the last 12 months:

Stolen or tried to steal a motor vehicle such as a car or motorcycle

Stolen or tried to steal something worth more than US$100

Purposely set fire to a building, a car, or other property, or tried to do so

Attacked someone with the idea of seriously hurting or killing that person

Involved in gang fights

Had or tried to have sexual relations with someone against their will

Used force or strong-arm tactics to get money or things from people

Broken or tried to break into a building or vehicle to steal something or just look around

Driven a motor vehicle while feeling the effects of alcohol

Had a motor vehicle accident and left the scene without letting the other person know about the accident

Purposely damaged or destroyed property belonging to someone you live with

Purposely damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you or someone you live with

Knowingly bought, sold, or held stolen goods, or tried to do any of these things

Carried a hidden weapon

Stolen or tried to steal things worth US$100 or less

Been paid for having sexual relations with someone

Used checks illegally to pay for something, or used intentionally overdrafts

Sold marijuana or hashish

Hit or threaten to hit anyone other than the people you live with

Sold hard drugs other than marijuana or hashish

Tried to cheat someone by selling them something that was worthless or not what you said it was

Avoided paying for such things as food, movies, or bus or subway rides

Used or tried to use the credit cards of someone you didn’t live with, without the owner’s permission

Made obscene telephone calls

Snatched someone’s purse or wallet or picked someone’s pocket

Embezzled money

Paid someone to have sexual relations with you

Stolen money or other things from someone you live with

Stolen money, goods, or property from the place you work

Hit or threatened to hit someone you live with

Been very loud, rowdy, or unruly in a public place

Taken a vehicle for a ride without the owner’s permission

Begged for money or things from strangers

Used or tried to use the credit cards of someone you live with, without permission

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The Buffalo Longitudinal Study of Young Men was supported by a five-year grant funded through the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (# RO1 AA08157).

Financial disclosure/conflict of interest

None.

References

- Akers RL, Krohn MD, Lanza-Kaduce L, Radosevich M. Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. American Sociological Review. 1979;44(4):636–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G, Farrell M. Parental support and control as predictors of adolescent drinking, delinquency and related problem behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:763–776. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G, Welte J, Hoffman J, Dintcheff B. Gambling and alcohol use among youth influences of demographic, socialization and individual factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(6):749–767. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G, Welte J, Hoffman J, Dintcheff B. Shared predictors of youthful gambling, substance use and delinquency. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(2):165–174. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch JL, Hanson RF, Saunders BF, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. Income, race/ethnicity, and exposure to violence in youth: Results from the national survey of adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(6):625–641. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth S, Brown SL. Family Structure, Family Processes, and Adolescent Delinquency: The Significance of Parental Absence versus Parental Gender. Journal of Research in Crime & Delinquency. 2004;41(1):58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Loeber R. Adolescent marijuana and alcohol use: the role of parents and peers revisited. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1985;11(1-2):11–25. doi: 10.3109/00952998509016846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug abuse. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hartinger-Saunders RM, Rittner B, Wieczorek W, Nochajski T, Rine CM, Welte J. Victimization, psychological distress and subsequent offending among youth. Children & Youth Services Review. 2011;33(11):2375–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie D, Silver E, Teasdale B. Neighborhood characteristics, peer networks, and adolescent violence. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2006;22(2):147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WL, Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA. Parent-child relations and offending during young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(7):786–799. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9591-9. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9591-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalf AC, Kroes M, Vles JS, Hendricksen JGM, Feron FJM, Steyaert J, vanZeben TM, Jolles J, van Os J. Neighbourhood level and individual level SES effects on child problem behavior: a multilevel analysis. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2001;55:246–250. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.4.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuther T, Wallace S. Community violence and sociomoral development: An African American cultural perspective. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2003;72(2):177–189. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.73.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL. How families and communities influence youth victimization. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington D.C.: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lorion R, Saltzman W. Children’s exposure to community violence: Follow a path from concern to research to action. Psychiatry. 1993;56:55–65. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack KY, Leiber MJ, Featherstone RA, Monserud MA. Reassessing the family-delinquency association: Do family type, family processes, and economic factors make a difference? Journal of Criminal Justice. 2007;35(1):51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE. Socioeconomic disadvantage and violence: Recent research on culture and neighborhood control as explanatory mechanisms. Aggression & Violent Behavior. 2003;8(2):145. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty TL, Bellair PE. explaining racial and ethnic differences in adolescent violence: structural disadvantage, family well-being, and social capital. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Anderson AL. Unstructured socializing and rates of delinquency. Criminology. 2004;42(3):519–549. [Google Scholar]

- Ordonez J. The influence of parental support on antisocial behavior among sixth through eleventh graders. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A. 2011;71 [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet S, Dempsey M. Availability of family support as a moderator of exposure to community violence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(2):151. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet S, Dempsey M, Graham D, Moely B. Availability of family support as a moderator of exposure to community violence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:151–159. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. The American Journal of Sociology. 1989;94(4):774–802. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Wallace LE. Families, delinquency, and crime: Linking society’s most basic institution to antisocial behavior. Roxbury Publishing Company; Los Angeles, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Valois RF, MacDonald JM, Bretous L, Fischer MA, Drane JW. Risk Factors and Behaviors Associated With Adolescent Violence and Aggression. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;26(6):454. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte J, Barnes G, Hoffman J, Wieczorek W, Zhang L. Substance involvement and the trajectory of criminal offending in young males. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31:267–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte J, Zhang L, Wieczorek W. The effects of substance use on specific types of criminal offending in young men. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38(4):416–438. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström P-O, Loeber R. Do disadvantaged neighborhoods cause well-adjusted children to become adolescent delinquents? A study of male juvenile serious offending, risk and protective factors, and neighborhood context. Criminology. 2000;38:1109–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Welte J, Wieczorek W. The Influence of Parental Drinking and Closeness on Adolescent Drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(2) doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Welte J, Wieczorek W. Deviant lifestyle and crime victimization. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2001;29(2):133–143. [Google Scholar]