Summary

This study investigates the relationship between classical cadherin binding affinities and mechanotransduction through cadherin-mediated adhesions. The mechanical properties of cadherin-dependent intercellular junctions are generally attributed to differences in the binding affinities of classical cadherin subtypes that contribute to cohesive energies between cells. However, cell mechanics and mechanotransduction may also regulate intercellular contacts. We used micropipette measurements to quantify the two-dimensional affinities of cadherins at the cell surface, and two complementary mechanical measurements to assess ligand-dependent mechanotransduction through cadherin adhesions. At the cell surface, the classical cadherins investigated in this study form both homophilic and heterophilic bonds with two-dimensional affinities that differ by less than threefold. In contrast, mechanotransduction through cadherin adhesions is strongly ligand dependent such that homophilic, but not heterophilic ligation mediates mechanotransduction, independent of the cadherin binding affinity. These findings suggest that ligand-selective mechanotransduction may supersede differences in cadherin binding affinities in regulating intercellular contacts.

Key words: Cadherin; Mechanotransduction; Binding selectivity; Magnetic twisting cytometry; Micropipette manipulation, MTC

Introduction

Cadherins are essential adhesion proteins at intercellular junctions in all cohesive tissues. In mature tissues, they maintain the mechanical integrity of cell–cell junctions, and regulate the barrier properties of tissues such as the vascular endothelium and intestinal epithelia. In development, cadherins are essential for morphogenesis (Gumbiner, 2005). Following the first demonstrations that dissociated embryonic cells re-aggregated with cells from the same germ layer in vitro (Steinberg and Gilbert, 2004; Townes and Holtfreter, 1955), in vitro assays demonstrated that different cadherins induce cells to segregate away from each other (Friedlander et al., 1989; Nose et al., 1988). In vitro assays, which visualized cell aggregate compositions either in hanging droplets or in agitated cell suspensions, suggested that cell-sorting might be driven by differential adhesion (Friedlander et al., 1989; Steinberg, 1962; Steinberg, 1963; Townes and Holtfreter, 1955) and the minimization of surface free energies, attributed to differences in cadherin binding affinity or surface expression (Foty et al., 1996; Foty,and Steinberg, 2005; Steinberg, 1962; Steinberg, 1963; Steinberg, 2007).

Observations support the hypothesis that surface free energy minimization determines cell organization in vitro and in vivo. Cells in the ommatidium of the Drosophila retina adopt patterns that are similar to surface-tension-dependent shapes of soap bubbles (Hayashi and Carthew, 2004; Hilgenfeldt et al., 2008; Käfer et al., 2007). In Drosophila, oocyte positioning in the egg chamber requires DE-cadherin expression and appears to correlate with the local DE-cadherin expression levels (Godt and Tepass, 1998). Genetic switches control the programmed down regulation and expression of different cadherins during neural crest cell emergence and migration out of the neurepithelium (Niessen et al., 2011; Takeichi et al., 1990).

Cadherins were initially thought to mainly form homophilic bonds, based on the tendency of cells expressing the same cadherin to co-aggregate in vitro (Nose et al., 1988). However, semi-quantitative estimates of interfacial tension and cell adhesion (Duguay et al., 2003; Niessen and Gumbiner, 2002), as well as quantitative measurements of cadherin adhesion energies and solution binding affinities (Chien et al., 2008; Harrison et al., 2010; Katsamba et al., 2009; Prakasam et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2008; Vendome et al., 2011), contributed to a more nuanced view that cadherin subtypes cross-react, but that their relative adhesion energies determine cell segregation patterns. Comparisons of cadherin-dependent, in vitro cell sorting with solution binding affinities suggest that affinities differing by more than fivefold support cell segregation (Katsamba et al., 2009; Tabdili et al., 2012). However, in other cases, smaller adhesive differences did not predict cell-sorting outcomes (Niessen and Gumbiner, 2002; Prakasam et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2008).

Despite the appeal of the surface-free-energy-minimization arguments, cell surface adhesion energies do not account for the effect of cortical tension on intercellular interactions. Increasing evidence suggests that myosin II-dependent contractile forces are central to determining cell shape, intercellular extension, and the maintenance of tissue boundaries (Bertet et al., 2004; Lecuit, 2005; Lecuit and Le Goff, 2007; Lecuit and Lenne, 2007; Lecuit et al., 2011). Studies increasingly also show that mechanical forces exerted during development alter signaling and actomyosin dynamics (Kasza and Zallen, 2011). Cell elongation and intercalation are driven by anisotropic tension in cells that originates from asymmetric intracellular myosin II and actin distributions (Bertet et al., 2004; Cavey et al., 2008; Rauzi et al., 2010; Tepass et al., 2002). During cell division, the strict maintenance of some cell compartments appears to be regulated largely by cortical actomyosin bundles adjacent to the membrane (Monier et al., 2010). The elastic-like properties of tissues also appear to influence cell organization in Xenopus embryos (Luu et al., 2011). In a comparison of the relative influence of adhesion versus cortical tension, single cell force spectroscopy measurements demonstrated that cohesive forces between zebrafish germline progenitor cells did not specify cell localization in the embryo (Krieg et al., 2008). Instead, cortical tension appeared to determine cell positioning. Theoretical analysis predicts that cortical tension and adhesion energies coordinately influence sorting (Manning et al., 2010).

The seemingly overriding role of cell mechanics in directing some cell movements in vivo was puzzling in light of the cadherin requirement for morphogenesis and cell segregation in vitro. The connection between cadherin-dependent sorting and cortical tension was not obvious. However, the recent discovery that cadherin complexes are intercellular force sensors suggests a cadherin-dependent mechanism that could bridge both the cadherin requirement for cell sorting and cadherin-mediated changes in cortical tension (Ladoux et al., 2010; le Duc et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010; Yonemura et al., 2010). Cadherins are both adhesion proteins and cytoskeletal regulatory proteins (Niessen et al., 2011). Although cadherin ligation alone activates changes in cytoskeletal organization through Src and GTPases, cadherin complexes actively respond to applied force to alter cell mechanics (Ladoux et al., 2010; le Duc et al., 2010; Yonemura et al., 2010). An unanswered question has been whether cadherin-binding specificity could also modulate cell mechanics.

This study demonstrates that mechanotransduction at cadherin complexes is ligand dependent, but that ligand-selective force sensation is not determined by the affinities of the cadherin bonds. Magnetic twisting cytometry and traction force microscopy assessed mechanotransduction in response to acute, bond shear and to endogenous contractile forces on cadherin bonds, respectively. Micropipette measurements of cadherin-mediated intercellular binding kinetics determined the two-dimensional (2D) binding affinities and dissociation rates of the identical cadherin pairs as probed in mechanical measurements. Comparisons of cadherin binding affinities with mechanotransduction responses show that homophilic, but not heterophilic cadherin ligands trigger junction reinforcement, independent of the cadherin affinities. Qualitatively similar results were obtained with five different cell lines and three different classical cadherins. They suggest that, although classical cadherin binding affinities differ, the ligand-dependent modulation of cell mechanics may play a greater role in regulating intercellular boundaries.

Results

EC1-dependent cadherin binding affinities

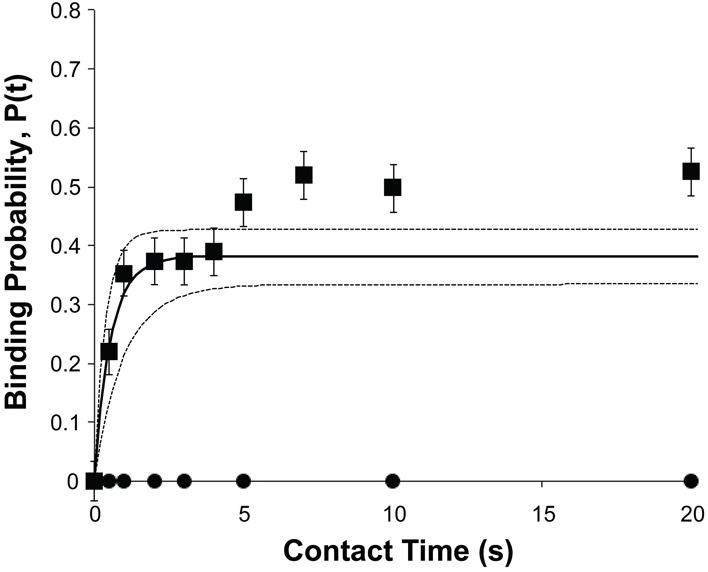

Micropipette manipulation measurements (Fig. 1A) (Chesla et al., 1998; Chien et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2010; Long et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2005) were used to determine the two-dimensional EC1-dependent binding affinities between cell surface cadherins (Fig. 1B) and recombinant human immunoglobulin Fc-tagged cadherin extracellular domains immobilized on an apposing red blood cell (Fig. 1C) (Chien et al., 2008). This experiment quantifies the intercellular binding probability, which is the number of intercellular binding events nb divided by the number of cell–cell contacts NT, as a function of the intercellular contact time. The binding probability is related to the number of inter-surface bonds (Chen et al., 2008). Fig. 2 shows the time dependence of the binding probability measured between an MDCK cell (E-cad) and a red blood cell (RBC) modified with oriented, Fc-tagged extracellular domains of canine E-cadherin (k9E-cad.Fc). As observed previously (Chien et al., 2008), the time course exhibits two kinetic stages. There is a fast, initial rise to a plateau at a probability P1 ∼0.4 – that is, four out of ten cell–cell contacts results in binding. After a 2–5-second delay, the binding probability again rises to a final, limiting plateau at P2 ∼0.53.

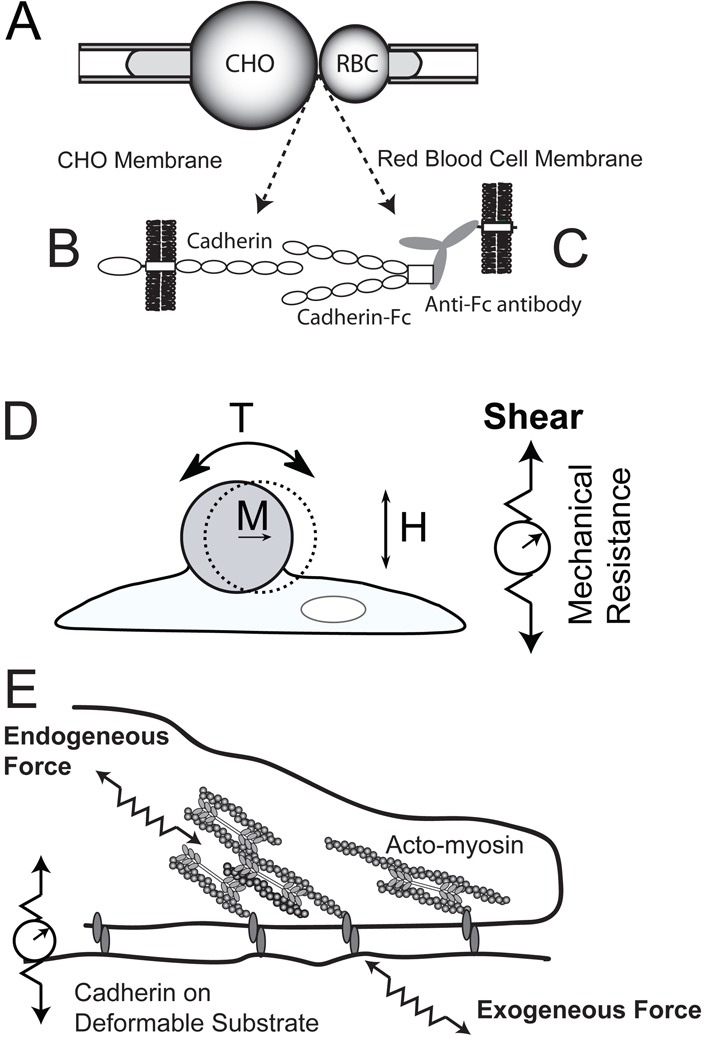

Fig. 1.

Schematic of micropipette manipulation, magnetic twisting cytometry and traction force experiments. (A) In micropipette manipulation measurements, CHO cells expressing the full cadherin (B) are brought into contact with red blood cells modified with oriented cadherin extracellular domains (C). The cadherin on the CHO cells (left) contacts Fc-tagged cadherin extracellular domains bound to the red-cell membrane by immobilized, anti-Fc antibodies. (D) In magnetic twisting cytometry, cadherin-modified beads with magnetization M attached to cell membranes are subject to an oscillating field H, which generates torque T on cell surface proteins. Changes in the bead displacement amplitudes reflect changes in the junction stiffness (right) due to junction remodeling and/or global cell contractility. (E) Traction force measurements quantify the contractile forces exerted at cadherin adhesions between cell surface proteins and cadherin ectodomains immobilized on compliant polyacrylamide gels.

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of cadherin-mediated binding between an MDCK cell and a red cell modified with oriented k9-E–cad.Fc extracellular domains. The E-cadherin densities on the MDCK cell and the red blood cells were 17 cadherin/µm2 and 7 cadherin/µm2, respectively. The contact area Ac was 7 µm2. The solid line is the best, nonlinear least squares, fit of Eqn 1 to the data for the first, EC1-dependent binding step, and the dashed lines are the 95% confidence intervals. Best fit parameters are summarized in Table 1.

A prior study with Xenopus C-cadherin mediated cell–cell binding first reported the two-stage binding kinetics (Chien et al., 2008). The use of domain deletion mutants localized the different features in kinetic time course to structural regions of the extracellular domain. The latter approach demonstrated that the fast, first step requires the EC1 domain, whereas the second rise to the second plateau P2 requires the full ectodomain, e.g. EC1-5 (Chien et al., 2008). Because EC1 embeds the specificity-determining region (Nose et al., 1990), the analyses of the kinetic data described in this study focused on the first EC1-dependent binding step.

The trans dimerization of EC1 domains occurs by the mutual exchange of tryptophan at position 2 (W2), in which the side chain of W2 docks in the binding pocket of the EC1 domain of an apposing cadherin (Boggon et al., 2002). This mechanism is described by the reaction scheme:

|

The following equation (Eqn 1) gives the analytical expression for the time-dependent binding probability P(t) for this reaction (Chesla et al., 1998):

| (1) |

where mL and mR are the receptor and ligand surface densities (no./µm2) on the two cells, Ac is the contact area (µm2), Ka is the two-dimensional binding affinity (µm2), and kr is the dissociation rate (s−1). Therefore, Ka and kr can be determined from nonlinear, least-squares fits of the first EC1-dependent binding step to Eqn 1. Details of the data analyses are described in Materials and Methods.

The solid line in Fig. 2 is the weighted, nonlinear least squares fit of the first binding step to Eqn. 1, and the best-fit two-dimensional affinity for homophilic canine E-cadherin binding is 3.3±0.2×104 µm2 (Fig. 2). Homophilic binding between N-cadherin on MDA-MB-435 cells and chicken (ck) N-cad.Fc on the apposing RBC, as well as heterophilic binding between ck N-cad.Fc (RBC) and canine E-cadherin (MDCK) similarly exhibit two-stage kinetics (not shown). The best-fit, 2D affinity for homophilic N-cadherin binding was 1.9±0.3×104 µm2, and the heterophilic binding affinity is intermediate between the homophilic affinities at 2.8±0.3×104 µm2. The best-fit parameters are summarized in Table 1. The results of measurements with MCF7 cells probed with canine E-cad.Fc or with ck N-cad.Fc are also in Table 1. In these measurements, the homophilic E-cadherin affinity exceeds that of N-cadherin, although the absolute differences are not large.

Table 1.

Best fit parameters from nonlinear least squares fits of EC1-dependent cell–cell binding kinetics to Eqn 1

| Test cell | Cadherin | Density (#/µm2) | Red cell | Density (#/µm2) | 2D affinity (×10−4 µm2) | Off rate (s−1) |

| MDCK | k9 E-cadherin | 17 | k9 E-cad.Fc | 7 | 3.6±0.2 | 1.7±0.3 |

| MDCK | k9 E-cadherin | 17 | ck N-cad.Fc | 20 | 2.5±0.2 | 1.5±0.3 |

| MDA-MB-435 | hN-cadherin | 93 | ck N-cad.Fc | 32 | 0.70±0.06 | 1.9±0.3 |

| MDA-MB-435 | hN-cadherin | 93 | k9 E-cad.Fc | 7 | 1.2±0.2 | 1.5±0.3 |

| MCF7 | hE-cadherin | 7 | k9 E-cad.Fc | 18 | 4.2±0.2 | 2.4±0.4 |

| MCF7 | hE-cadherin | 7 | ck N-cad.Fc | 37 | 2.7±0.1 | 2.2±0.4 |

Cadherin-dependent mechanotransduction is ligand dependent

To determine how cadherin affinity differences affect force transduction through cadherin adhesions, magnetic twisting cytometry measurements (MTC; Fig. 1D) were carried out with different cells and different cadherin ligands. These measurements quantify changes in cadherin junction mechanics in response to shear forces applied to cadherins on the cell surface by ligand-modified beads. These studies used ferromagnetic beads that were modified with recombinant, extracellular domains of either the same cadherin subtype as expressed on the cell (homophilic ligand) or a different subtype (heterophilic ligand). In these measurements, the bead is magnetized parallel to plane of the cell, and an orthogonal oscillatory magnetic field induces a torque on the bead, causing it to twist (Fig. 1D). The resultant bead displacement reflects the viscoelasticity of the bead–receptor–cytoskeletal junction, such that changes in the bead displacement reflect junction remodeling and cell contractility.

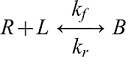

Fig. 3 compares bond shear measurements conducted with four different cell lines: MDCK, C2C12, MCF7 and MDA-MB-435 cells. The probe beads were modified with Fc-tagged ectodomains of chicken N-cadherin, canine E-cadherin, or Xenopus C-cadherin, as in the micropipette measurements. Fig. 3A shows the percent change in the stiffness of the bead-cell junction, relative to unperturbed bonds. Here, the adhesive junction was between N-cad.Fc coated beads and N-cadherin on C2C12 cells. As reported previously with F9 cells (le Duc et al., 2010), the cadherin junction stiffens in response to acute, applied bond shear. This stiffening response is ablated by treatment with EGTA (Fig. 3A), which chelates Ca2+ ions required for cadherin function. It is also abolished following F-actin depolymerization by treatment with latrunculin B (Fig. 3B). The mechanotransduction is therefore cadherin and F-actin dependent, in agreement with previous findings (le Duc et al., 2010). By contrast, when the beads were modified with a different cadherin subtype, e.g. C-cad.Fc or E-cad.Fc, there was no change in junction stiffness relative to controls. Bead pulls with an anti-N-cadherin antibody, which recognizes the N-terminal EC1 domain, also failed to induce junction remodeling (Fig. 3B). The results of measurements with CHO cells stably transfected with N-cadherin (N-CHO) are in supplementary material Fig. S1.

Fig. 3.

Cadherin-dependent mechano-transduction is ligand selective. (A) MTC measurements of the force-induced stiffening response of C2C12 cells probed with beads coated with N-cad.Fc (black squares), E-cad.Fc (black circles) or C-cad.Fc (gray circles). Controls were with N-cad.Fc beads and 4 mM EGTA (white diamonds). (B) Control measurements with C2C12 cells probed with beads coated with anti-N-cadherin antibody (white diamonds), or with N-cad.Fc in the absence (black squares) and presence (black circles) of latrunculin B. (C) MTC measurements of the force-induced stiffening response of MDA-MB-435 cells probed with beads coated with N-cad.Fc (black squares), E-cad.Fc (black circles) or C-cad.Fc (gray circles). Controls were with N-cad.Fc in the presence of 4 mM EGTA (white diamonds). (D) MTC measurements of MCF7 cells probed with beads coated with E-cad.Fc (black squares), N-cad.Fc (black circles) or C-cad.Fc (gray circles). Controls were with E-cad.Fc, in the presence of EGTA (white diamonds). (E) MCF7 controls with E-cad.Fc-coated beads in the presence of Lat B (black circles) or with beads coated with anti-E-cadherin antibody. (F) The stiffening response of MDCK cells probed with E-cad.Fc (black squares) or N-cad.Fc (black circles). Control measurements were with EGTA (white diamonds). In A–F, each point represents measurements of >200 beads.

In all cases investigated (Fig. 3A–F), only homophilic ligand-induced junction stiffening during the first 120 s of shear modulation, and heterophilic ligands consistently failed to induce any response (Fig. 3). C2C12 and MDA-MB-435 cells both express endogenous N-cadherin (Fig. 3A–C), and shear applied only to beads coated with N-cad.Fc, but not E-cad.Fc or antibody, triggered force-activated junction remodeling. Similarly, MCF7 and MDCK cells (Fig. 3D–F), which express endogenous E-cadherin, required E-cad.Fc-coated beads to induce junction stiffening.

The finding that only homophilic cadherin ligation induces the mechanoresponse was unexpected, in light of the binding affinities quantified with the identical cells and cadherin ligands (Table 1). Both protein adhesion measurements and solution binding affinities show that cadherin subtypes cross-react, often with heterophilic affinities that are intermediate between those of the homophilic bonds (Katsamba et al., 2009; Prakasam et al., 2006; Steinberg, 2007). Here, although the heterophilic ligands bind cell-surface cadherins, as demonstrated by micropipette manipulation measurements, they do not trigger force transduction.

The ligand requirement for mechanotransduction is further demonstrated by measurements with beads modified with anti-N-cadherin or with anti-E-cadherin antibodies. Both antibodies recognize the N-terminal domains of the respective target cadherins. Although the antibody-modified beads firmly bound to cadherins on C2C12 and MCF7 cells, neither triggered an active response to applied bond shear (Fig. 3B,E). This agrees with a similar result obtained with beads modified with DECMA-1 (E-cadherin blocking antibody) and F9 cells (le Duc et al., 2010).

Cadherin complexes are rigidity sensors

To address the possibility that bead pulls may not reflect physiologically relevant stress, complementary traction force measurements tested the ability of cadherin complexes to sense substrate rigidity, and to proportionally alter endogenous contractile stress. Prior studies of force sensation at focal adhesions demonstrated that mechanoresponses to exogenous force parallel substrate rigidity sensing (Geiger et al., 2009). In these studies, endogenous contractile forces exert physiological forces at cadherin adhesions to elastomeric substrata coated with cadherin ectodomains (Fig. 1E). The cadherin pairs mediating these cell-substratum adhesions are identical to those probed by micropipette manipulation and by MTC.

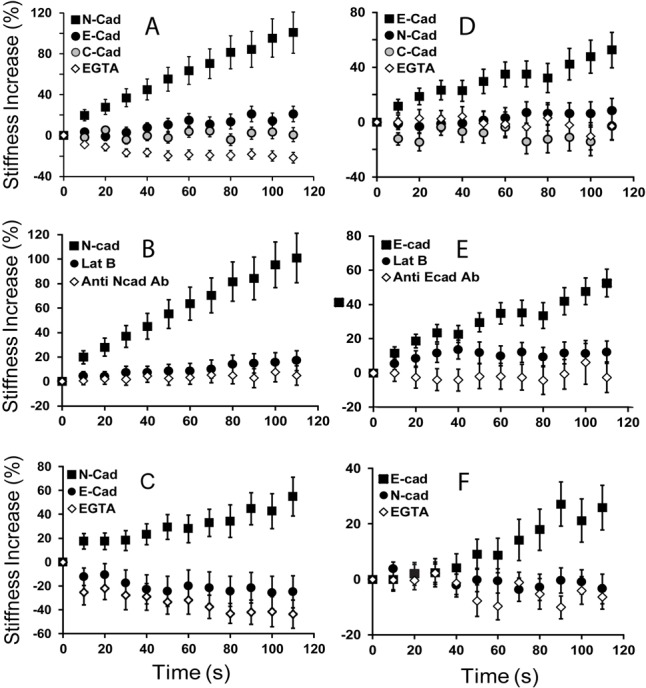

Fig. 4A compares traction forces generated by MDCK cells on polyacrylamide gels with elastic moduli of 34 kPa and 0.6 kPa, when coated with E-cad.Fc or with N-cad.Fc ligand. At ∼160 ng/µm2, the immobilized protein densities were similar for both cadherin ectodomains on both hydrogels. MDCK cells generated greater traction on rigid gels coated with E-cad.Fc than on soft gels (Fig. 4A), confirming that E-cadherin complexes also sense substrate rigidity. MDA-MB-435 cells similarly exhibited rigidity-dependent traction forces on N-cad.Fc-coated hydrogels (Fig. 4C). This rigidity sensing via homophilic cadherin ligation agrees with a prior report of myoblast traction forces on elastomeric pillars coated with N-cadherin (Ladoux et al., 2010). Blebbistatin (50 µM) and cytochalasin D (4 µM) substantially reduced the traction forces generated on rigid substrata (Fig. 4B,D), in agreement with prior findings (Ladoux et al., 2010).

Fig. 4.

Cadherin-based traction forces are rigidity and ligand dependent. (A) Root-mean-square (RMS) traction forces (Pa) exerted by MDCK cells on soft (0.6 kPa) and rigid (34 kPa) gels coated with E-cadh.Fc (homophilic) or N-cad.Fc (heterophilic) ligand. (B) Traction force exerted by MDCK cells seeded on E-cad.Fc-coated, rigid (34 kPa) gels, after treatment with blebbistatin or cytochalasin. (C) RMS traction forces exerted by MDA-MB-435 cells on soft (0.6 kPa) and rigid (34 kPa) gels coated with N-cad.Fc (homophilic) or E-cad.Fc (heterophilic) ligand. (D) Control RMS traction force exerted by MDA-MB-435 cells on N-cad.Fc-coated, rigid (34 kPa) gel, after treatment with blebbistatin or cytochalasin D (Cyto D).

By contrast, on the stiffer gels (34 kPa) coated with heterophilic cadherin ligands, both MDCK cells and MDA-MB-435 cells generated lower traction forces (Fig. 4A,C). The lower traction forces exerted by MDCK cells on N-cad.Fc coated gels might be explained by the lower heterophilic bond affinity relative to the homophilic E-cad.Fc affinity (Table 1). However, this would not explain the behavior of MDA-MB-435 cells because the measured homophilic N-cadherin affinity is lower than the heterophilic affinity (Table 1). Yet the cells exert greater traction forces on N-cad.Fc coated gels. On soft hydrogels (0.6 kPa), both cell types were more rounded, and traction forces were low and ligand independent, within experimental error.

To further test the role of cell contractility in traction force generation MDA-MB-435 cells treated with nocodazole (20 µM) on gels with elastic moduli of 0.6 kPa and 34 kPa. Microtubule depolymerization increases cell contractility via a Rho-GTPase-dependent pathway (Danowski, 1989). As expected, nocodazole treatment increased the traction forces. As shown in supplementary material Fig. S3 the magnitudes of the increase in traction forces were almost the same in cells adhering to homophilic versus heterophilic cadherin ligand, on the gels with the same elastic modulus.

Different from the MTC measurements, heterophilic ligation reduced the traction forces by only ∼50% relative to controls with blebbistatin or cytochalasin D treated cells. This could be due to compensatory mechanisms regulating cell contractility on these substrata. For example, cells also generated rigidity-dependent traction forces on poly-L-lysine-coated gels ∼3 hr after seeding in serum-free medium (not shown), suggesting that parallel mechanisms may regulate global cell contractility. This behavior is not due to integrin interference because immunofluorescence did not detect focal adhesions at the basal surface.

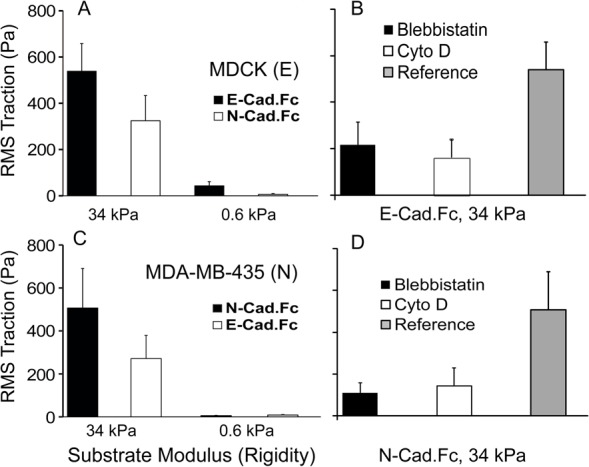

Consistent with a functional role of tension in stabilizing cadherin adhesions, more cells attached and spread on the more rigid substrata coated with homophilic cadherin ligands (Fig. 5A,B). Again, the greater MDCK cell densities on E-cad.Fc than on N-cad.Fc-coated substrata might initially be attributed to the relative affinities of the homophilic versus heterophilic E-cadherin bonds. However, greater numbers of MDA-MB-435 cells adhered to rigid substrata coated with N-cad.Fc relative to E-cad.Fc, despite the lower affinity of the homophilic N-cadherin bond (Table 1). On the softer gels, there was no statistically significant difference in cell attachment densities to either homophilic or heterophilic ligands.

Fig. 5.

Cell attachment densities on rigid substrata are ligand dependent. (A) Density of MDA-MB-435 cells attached to substrates with Young’s moduli of 34 and 0.6 kPa modified with N-cad.Fc (homophilic) and E-cad.Fc (heterophilic) ligands 4 hr after cell seeding in serum-free medium. (B) Density of MDCK cells on substrates with Young’s moduli of 34 and 0.6 kPa coated with E-cad.Fc (homophilic) and N-cad.Fc (heterophilic) ligands, 4 hr after cell seeding in 0.5 v/v% FBS.

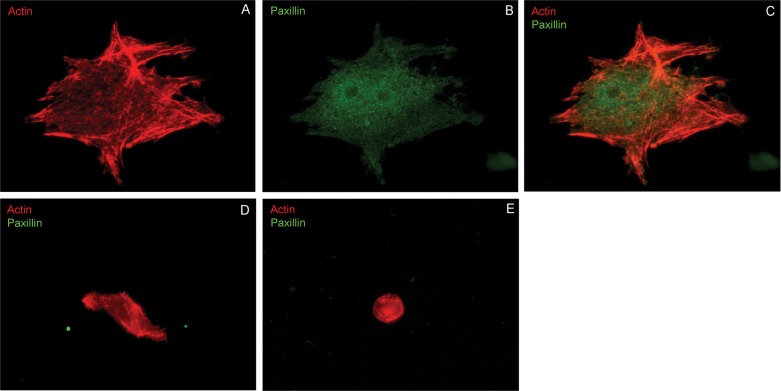

In Fig. 6A–C, well defined actin stress fibers and punctate paxillin staining are apparent in MDA-MB-435 cells spread on collagen-coated semi-rigid polyacrylamide (34 kPa), in the presence of serum (10 v/v% FBS). The absence of paxillin staining at the basal cell surface, on both soft and rigid gels (Fig. 6D,E), ruled out integrin interference in either the traction force or cell attachment measurements.

Fig. 6.

Actin and paxillin at the basal surface of cells on cadherin-coated hydrogels. (A) Actin and (B) paxillin immunostaining in MDA-MB-435 cells seeded on rigid (34 kPa), collagen-coated hydrogels, 6 hr after seeding in RPMI medium. (C) Merged fluorescence images of MDA-MB-435 cells seeded on rigid collagen-coated hydrogels. (D) Paxillin and actin staining in MDA-MB-435 cells seeded on N-cad.Fc-coated hydrogel (34 kPa), 6 hr after seeding in serum-free medium. (E) Paxillin and actin immunostaining of MDA-MB-435 cells seeded on N-cad.Fc-coated soft (0.6 kPa) hydrogel, 6 hr after seeding in serum-free medium.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that mechanotransduction at cadherin adhesions requires homophilic ligation, and that force-activated junction remodeling appears to be insensitive to differences in the intrinsic two-dimensional cadherin binding affinities. The binding affinity and cell surface adhesion energy do not determine the magnitude of force-dependent, cadherin-mediated changes in cell mechanics. This is somewhat analogous to findings that focal adhesion-mediated rigidity sensing and adhesion are independent (Engler et al., 2004). However, the mechanisms of cadherin adhesion, binding selectivity and mechanotransduction are distinct from integrins.

The results suggest that differences in mechanical changes at stressed cadherin junctions could supersede more subtle differences in cadherin affinities. This could explain, in part, the finding that cortical tension better predicted cell positioning in zebrafish embryos than the cohesiveness of the germline progenitor cells (Krieg et al., 2008). It was unclear how to reconcile the latter result with the extensive literature suggesting that cadherin-dependent differences in adhesion energies could direct cell sorting (Duguay et al., 2003; Foty and Steinberg, 2004; Foty, and Steinberg, 2005; Katsamba et al., 2009; Niessen et al., 2011; Nose et al., 1990; Steinberg, 1963; Steinberg and Takeichi 1994; Steinberg, 2007). Our findings suggest a cadherin-dependent mechanism that could both determine cohesive energies and regulate junctional or possibly global (Chopra et al., 2011) cell mechanics.

The two-dimensional affinities determined from micropipette studies are equilibrium, time-independent properties of EC1-EC1 bonds, but the MTC and traction force measurements are mechanical approaches that may reflect different properties of cadherin bonds. For example, single bond rupture forces depend on dissociation rates rather than affinities (Dudko et al., 2007; Evans and Ritchie, 1997). However, none of the bond parameters determined thus far generally favor homophilic over heterophilic bonds. The dissociation rates determined from micropipette measurements (Table 1), single bond rupture studies (Shi et al., 2008), or SPR studies (Katsamba et al., 2009) do not correlate with the mechanoselectivity. Neither do the single bond rupture forces (Shi et al., 2008). Some studies suggest that the heterophilic binding frequency, which is related to the association rate, might be lower than for homophilic bonds (Berx and van Roy, 2009; Panorchan et al., 2006), but this is not the case for the protein pairs considered here. Thus, the cadherin binding properties alone do not appear to confer mechanical selectivity.

The second step in the kinetic profile was not considered in this analysis for two main reasons. First, studies of cadherin-dependent cell segregation have focused on EC1 (Katsamba et al., 2009; Nose et al., 1990), and one aim of these studies was to determine how EC1-dependent binding properties influence mechano-transduction. Second, the second binding stage in the binding time course does not involve the EC1 domain. Prior studies with C-cadherin showed that the second step requires EC3 (Chien et al., 2008). Because of the conserved binding behavior of different classical cadherins (Perret et al., 2004; Prakasam et al., 2006; Shapiro and Weis, 2009; Shi et al., 2008), we assume the C-cadherin findings apply to classical cadherins. Consistent with this view, N-glycans on EC2-EC3 of N-cadherin modulate the second kinetic step, but not the EC1 affinity (Langer et al., 2012). This indicates that the two kinetic steps involve different structural regions. EC1 mutants also altered both the affinity for the first step and cell sorting behavior, which is attributed to EC1-dependent cell cohesion (Tabdili et al., 2012).

The ligand-dependent mechanical differences are manifest at stressed cadherin junctions, and are expected to exert greater influence at stressed intercellular adhesions. On soft hydrogels, for example, where cells exert low contractile stress, there was no distinguishable ligand-dependence of the traction forces (Fig. 4A,C). Thus, interfacial energies might dominate cell–cell interactions in some cases, such as in soft tissue environments or in vitro cell sorting assays, where intercellular forces may be insufficient to effect significant differences in cortical tension. In this context, it is noteworthy that CHO cells, which are commonly used for in vitro sorting assays do not exert large contractile forces (Leader et al., 1983) (see supplementary material Fig. S1). Conversely, large intercellular forces generated during convergence extension or cell intercalation movements may be sufficient to activate cadherin-dependent changes in intercellular mechanics (Kasza and Zallen, 2011).

These results are also intriguing, in light of the postulated mechanism of cadherin-dependent mechanotransduction. Cadherin bond stress is thought to induce a conformational change in α-catenin bound to the cadherin/β-catenin complex that exposes a cryptic site in α-catenin (Yonemura et al., 2010). The latter recruits actin-binding proteins such as vinculin to junctions. The finding that mechanical stimulation with anti-cadherin antibodies (le Duc et al., 2010) or heterotypic ligands fails to activate mechanotransduction indicates that tension on cadherin ectodomains alone is insufficient to trigger the requisite change in α-catenin.

The molecular basis for cadherin mechano-selectivity remains to be determined. The independence cadherin bond properties and mechanotransduction selectivity suggests that additional molecular factors may contribute to force transduction at intercellular junctions. There is precedence for this. Anti-VE-cadherin antibody-coated beads failed to activate mechanotransduction via VE-cadherin (Tzima et al., 2005). However, the VE-cadherin complex comprises the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and PECAM, which appears to be the flow-sensitive mechano-transducer between endothelial cells subject to fluid shear stress (Hahn and Schwartz, 2009). Whether other membrane proteins contribute to selective force transduction by classical cadherins remains to be determined. Possible candidates are protocadherins (Chen and Gumbiner, 2006; Deplazes et al., 2009; Taveau et al., 2008), receptor tyrosine kinases (Brady-Kalnay et al., 1995; Hellberg et al., 2002; McLachlan and Yap, 2011) or growth factor receptors (Perrais et al., 2007; Shibamoto et al., 1994; Tzima et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2001). Recent findings demonstrated a role for protocadherin-19 in the regulation of N-cadherin-dependent cell–cell adhesion and migration (Papusheva and Heisenberg, 2010; Taveau et al., 2008), and PAPC regulates the adhesive activity of C-cadherin during Xenopus morphogenesis (Chen and Gumbiner, 2006). Nevertheless, the mechanoselectivity demonstrated here with five cell lines and three classical cadherin subtypes demonstrates that cadherin selectivity can modulate both intersurface adhesion energies and cell mechanics, both of which instruct morphogenesis and maintain compartment barriers in mature tissues.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Blebbistatin, cytochalasin D (Cyto D), latrunculin B (Lat B), monoclonal anti-N-cadherin antibody (clone GC-4), 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), poly-L-lysine, 3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane (APS), and glutaraldehyde were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Nocodazole was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-E-cadherin and anti-paxillin antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Acrylamide, N,N′-methylene-bis-acrylamide (Bis), TEMED and ammonium persulfate (AP) were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHS) and N-succinimidyl-6-(4′-azido-2′-nitrophenyl-amino) hexanoate (Sulfo-SANPAH) were from Pierce Biotech (Rockford, IL).

Plasmids and cell lines

The cDNA encoding the full-length chicken N-cadherin in the pEGFP-N1 plasmid was provided by Andre Sobel (Institut du Fer a Moulin; Gif-sur-Yvette, France). Canine E-cadherin cDNA in pEGFP-N1 plasmid was a gift from James Nelson (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA). These plasmids were transfected into Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Clones expressing wild-type N-cadherin (N-CHO) were selected in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 v/v% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The cadherin expression levels of all cells were determined by quantitative flow cytometry.

C2C12 mouse myoblasts were maintained in low glucose DMEM supplemented with 20 v/v% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine. MCF7 human breast epithelial cells were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10 v/v% FBS and 1% non-essential amino acids (NEAA, Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA). Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10 v/v% FBS. MDA-MB-435 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 v/v% FBS.

Protein production and purification

Recombinant, E- and N-cadherin ectodomains with C-terminal Fc tags were stably expressed in human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293). Cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10 v/v% FBS. Fc-tagged canine E-cadherin and chicken N-cadherin ectodomains (E-cad.Fc and N-cad.Fc) were purified from the conditioned medium with a protein-A Affigel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) affinity column followed by gel-filtration chromatography. The protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Quantification of expressed cadherin surface density

The densities of cell surface cadherins were quantified by flow cytometry (Chesla et al., 1998; Chien et al., 2008). Canine E-cadherin expressing cells (E-CHO and MDCK) were labeled with primary rat anti-E-cadherin antibody (DECMA-1, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and the secondary antibody was goat, anti-rat IgG-FITC. N-cadherin expressing cells (N-CHO and MDA-MB-435) were labeled with primary mouse anti-N-cadherin antibody (clone GC-4, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and the secondary antibody was goat, anti-mouse IgG-FITC (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Approximately 100,000 cells were used for each sample, and 3 µg/ml antibody was used for each labeling step. The labeling was in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 5 mM EDTA and 1 w/v% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The fluorescence intensity of labeled cells and of bead standards (Bangs Labs, Fishers, IN) were quantified with an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Calibration curves relating the fluorescence intensity to total surface bound fluorophores were generated with fluorescent bead standards (Zhang et al., 2005).

Erythrocyte purification and labeling

Human whole blood obtained from healthy donors was kept in VacutainersTM for the containment of biohazardous material. The erythrocytes were separated from whole blood with Histopaque 1119 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), as per the manufacturer’s protocol. A 12 ml aliquot of Histopaque 1119 was kept in a 50 ml centrifuge tube. Then 7 ml of whole blood and 7 ml of 0.9 w/v% NaCl were mixed, and slowly poured into the Histopaque-containing tube. The tube was centrifuged at 800 g for 20 min at room temperature in an Eppendorf 5810 benchtop centrifuge. After discarding the supernatant, the remaining cells were resuspended in 7 ml of 0.9 w/v% NaCl, followed by the addition of 1.5 ml of 6 w/v% dextran. The cells were then kept at room temperature for 45 min. The supernatant was removed and the remaining red blood cells (RBC) were washed twice with 0.9 w/v% NaCl, and suspended in 12 ml EAS45 (2.0 mM adenine, 110 mM dextrose, 55.0 mM mannitol, 50.0 mM NaCl, 10.0 mM glutamine and 20.0 mM Na2HPO4, at pH 8.0) (Dumaswala et al., 1996). The thus isolated RBCs can be used for up to 3 weeks, after which they are disposed of as biohazardous waste.

Polyclonal, anti-Fc-domain; goat polyclonal anti-human immunoglobin G (IgG); or polyclonal anti-Fc-domain, goat anti-mouse IgG (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) were covalently immobilized on RBC surfaces to capture cadherin-Fc constructs. These antibodies were covalently bound to glycoproteins on red blood cells, following CrCl3 activation (Gold and Fudenberg, 1967; Kofler and Wick, 1977). Approximately 106 RBCs were rinsed five times with 0.85 w/v% NaCl, and then resuspended in 250 µl 0.85 w/v% NaCl with 4 µg/ml of the desired antibody. The CrCl3 solution used to chemically activate carbohydrates on the RBC surface was diluted to concentrations below 0.01 w/v% with 0.02 mM sodium acetate in 0.85 w/v% NaCl (pH 5.5). To control the protein immobilization densities, serial dilutions of the CrCl3 solution were used. To bind antibodies to the cell surface, 250 µl of the diluted CrCl3 solution was added to 250 µl of RBC/antibody mixture, and mixed for 5 min. The reaction was halted by adding 500 µl of ‘Stop Solution’ (PBS with 5 mM EDTA and 1 w/v% BSA). The cells were washed twice with Stop Solution. The immobilized antibody density was determined by quantitative flow cytometry. The antibody-modified RBCs were suspended in 100 µl EAS45 and stored at 4°C until use.

Micropipette measurements of cell binding dynamics

The intercellular binding probability versus contact time was quantified with the micropipette manipulation technique, described previously (Chesla et al., 1998; Chien et al., 2008; Evans et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2005). The binding probability P is the number of detected binding events nB divided by the total number of cell–cell contacts, or nB/N. In these measurements, a cadherin-expressing cell and a cadherin-Fc modified RBC were partially drawn into micropipettes and held in a chamber containing L15 medium supplemented with 1 w/v% BSA (Fig. 1). The cells were visualized with a 100× oil immersion objective on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope, and the image output was recorded with a DAGE-MTI (Michigan City, MI) CCD100 camera interfaced to an LCD monitor. The cells were positioned with piezo-electric controllers, and cyclically brought in and out of contact. Adhesion events are identified from deformation of the RBC and recoil after bond rupture, as visualized with the microscope. The contact time was controlled with the piezo-electric actuator, which manipulated the position of one of the pipettes. The contact area was ∼7 µm2 (∼1.5 µm diameter), and was quantified with Zeiss Axiovision software. Binding probabilities were measured for 50 cell–cell contacts, for each cell pair tested. Each contact time represents measurements with at least three different pairs of cells, such that N>150. The probabilities P are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from the mean.

Model fits to the EC1-mediated binding step

When determining binding parameters from data fits to Eqn 1, we first determined the spread in the data at each time point. In this case, the best, unbiased estimated parameter is determined by weighted least squares analysis, with the weighting factor for each time point being the inverse of the variance at that time point. The kinetic parameters that best fit the data were then determined using weighted, non-linear least squares regression (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

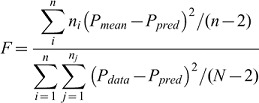

A non-linear lack-of-fit test (Neill, 1988) identified the time points associated with the first, EC1 strand swapping step. The test compares the model's residuals to the inherent variability in the data, normalized to an F-distribution (Eqn 2).

|

(2) |

where ni is the number of trials at each time point, n is the number of separate time points measured, Pmean is the mean probability at each time point, Ppred is the probability predicted by the model (i.e. Eqn 1), Pdata is each probability observed in the full data set, and N is the total number of observations. When the test statistic is larger than the critical value on an F distribution with (N−n, n−2) degrees of freedom, the model is rejected. The best-fit parameters summarized in Table 1 were obtained from fits of Eqn 1 to the maximum number of data points that did not fail the lack-of-fit test.

Magnetic twisting cytometry

In magnetic twisting cytometry (MTC) experiments (Fig. 1D), polystyrene-coated, 4.9 µm diameter, ferromagnetic beads with carboxyl surface groups (Spherotech, Lake Forest, IL) were covalently coated with specific Fc-Tagged protein, poly-L-lysine (PLL), or blocking antibody, and then allowed to bind to the cell surface. The beads were first activated with EDC/NHS, by incubation with EDC (10 mg/ml) and NHS (10 mg/ml), in MES buffer (50 mM, 100 mM NaCl, pH 5.0) for 15 min at room temperature, on a shaker. The beads were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min, and then incubated with 75 µg of the ligand of interest (Fc-tagged cadherin ectodomains, PLL, or blocking antibody) per mg beads for 2 hr at room temperature, in coupling buffer (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0). In order to prevent bead aggregation, beads were sonicated for 3 seconds before they were added to the cells. The protein-coated beads were then allowed to settle on a confluent cell monolayer for 20 min, before applying torque. To disrupt F-actin, cells were treated with 4 µM latrunculin B or 4 µM cytochalasin D for 10 min before twisting measurements.

All MTC studies were carried out with cells cultured in glass-bottomed dishes on a heated microscope stage at 37°C. Cells and beads were visualized with an inverted microscope (Leica) with a 20×, 0.6 numerical aperture objective and a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Orca2; Hamamatsu Photonics). First, beads were magnetized horizontally by applying a short, 1 Tesla field for ∼1 ms. Next, an oscillating magnetic field of 60 Gauss at a frequency of 0.3 Hz was applied orthogonal to the magnetic moment of the beads, for up to 120 seconds. This generates a modulated shear stress on the bead–cell junctions. The bead displacements were recorded with a CCD camera, and displacements were converted to the complex modulus of the junction, using custom software. The specific modulus is the ratio of the applied torque T to the bead displacement D, G = T/D, which gives the complex modulus of the bead–cell junction. The thus determined specific moduli follow a log-normal distribution, from which the geometric mean and standard deviation are obtained.

Traction force microscopy

Fourier transform traction force microscopy was carried out with compliant polyacrylamide gels surface-modified with cadherin ectodomains. Polyacrylamide gels were prepared as described previously (Beningo et al., 2002). Red fluorescent microspheres (0.2 µm, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) were embedded in gels. The Young’s moduli of the gels used in this study were 0.6 kPa and 34 kPa. The gels were covalently modified with 0.2 mg/ml of human or chicken anti-Fc antibody using Sulpho-SANPAH (Pierce Biotech, Rockford, IL). The samples were illuminated after each of two successive 200 µl additions of fresh Sulpho-SANPAH stock solution (0.5 mg/ml, 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.5). Samples were illuminated at 320 nm for 8 min, at 8–10 cm from two 15 W lamps. After each irradiation period, the samples were washed with 100 mM HEPES. After the second wash, anti-Fc antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) at 0.2 mg/ml was added and incubated with the gel overnight at 4°C. The substrates were rinsed to remove unbound antibody, and then incubated with N-cad.Fc or with E-cad.Fc (0.2 mg/ml in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0) for 4 hr at 4°C. The substrates were rinsed and blocked with 1 w/v% BSA in PBS for 30 min at room temperature.

Prior to seeding cells on the cadherin-Fc-coated gels, cells were detached from tissue culture flasks using 3.5 mM EDTA and 1 w/v% BSA in PBS, and then 2000–4000 cells/cm2 were seeded onto the hydrogels. MDA-MB-435 cells were cultured in serum-free medium, and MDCK cells were cultured in medium with 0.5 v/v% FBS. Measurements were conducted 6 hr after cell seeding. The bead displacement field was measured before and after cell detachment with 3.5 mM EDTA and 1 w/v% SDS in PBS. The constrained traction maps were calculated from the displacement field as described (supplementary material Fig. S2).

In traction force measurements following nocodazole treatment, MDA-MB-435 cells were seeded on soft (0.6 kPa) and semi-rigid (8.8 kPa, data not shown) and rigid (34 kPa) polyacrylamide gels coated with N-cad.Fc or E-cad.Fc for 6 hr. After obtaining phase contrast images of the single cells, a second fluorescence image of the beads near the surface was acquired. Bead displacements were again imaged after cells were treated with nocodazole (20 µM) for 30 min. The fluorescence images obtained after removing the cells gave the reference bead positions in the absence of traction force generation. In order to quantify the effect of nocodazole on the traction forces, we compared the reference bead positions to the bead displacements generated by cells before and after nocodazole treatment (supplementary material Fig. S3).

Characterization of elastic moduli of polyacrylamide gels

The gel elastic moduli (34 kPa and 1.78 kPa) were quantified with a compression tester. The compressive elastic moduli (E) of the gels were measured, by compressing the hydrogels with a mechanical testing system (MTS) at a rate of 0.1 mm/min and measuring the resulting stress. E was determined from the slope of the linear curve between stress and strain at the first 10% of strain.

Immunofluorescence

MDA-MB-435 cells were initially harvested with 3.5 mM EDTA with 1 w/v% BSA, and then seeded onto the hydrogels coated with either cadherin ectodomains or collagen. After 6 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2, the cells were fixed with 4 w/v% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 15 min and then washed with PBS. Cells were treated with 0.1 w/v% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at room temperature. After cell permeabilization, the fixed cells on the hydrogels were blocked with 1 w/v% BSA for 30 min at room temperature, and then washed with TBS. Cells were then incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with mouse monoclonal anti-paxillin antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in TBS with 1 w/v% BSA. Before incubation with secondary antibody, the cells were again washed with TBS. Secondary antibody, anti-mouse IgG FITC (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), was prepared in TBS containing 1 w/v% BSA. Rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to label F-actin. Substrates were incubated in secondary antibody for 1 hr and washed three times with TBS containing 0.1 v/v% Tween. Cells were mounted with AntifadeTM (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and visualized with an Axiovert 200 inverted fluorescence microscope using a 100× oil immersion objective.

Protein surface densities on polyacrylamide gels

To quantify the cadherin.Fc bound to the different hydrogels, anti-human immunoglobulin Fc was radiolabeled using Iodobeads (Pierce Biotech, Rockford, IL) and carrier-free Na[125I] (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The 125I-labeled protein was desalted with a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare Bioscience) to remove unbound 125I. The determined specific activity of 125I-labeled anti-Fc antibody was 7 cpm/ng.

Polyacrylamide hydrogels (0.6 kPa and 34 kPa) were prepared as described previously (10 mm diameter, 1 mm thickness). 125I-labeled immunoglobulin Fc was covalently bound to the gels that were chemically activated with Sulfo-SANPAH. Gels of defined size were then rinsed with buffer to remove unbound protein, and placed in scintillation vials containing 5 ml of scintillation cocktail. The radioactivity in each sample was recorded with an LS 6500 scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments) with specified settings for 125I detection. Control measurements used hydrogels incubated with the labeled protein, but without the Sulpho-SANPAH cross-linker.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by National Science Foundation division of Civil, Mechanical and Manufacturing Innovation [grant number 10-29871 to D.E.L.]; the National Institutes of Health [grant number GM072744 to N.W.]; the National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship [grant number 0965918 to H.T.]; and the National Science Foundation Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental, and Transport Systems [grant number 0853705 to M.D.L.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.105775/-/DC1

References

- Beningo K. A., Lo C. M., Wang Y. L. (2002). Flexible polyacrylamide substrata for the analysis of mechanical interactions at cell-substratum adhesions. Methods Cell Biol. 69, 325–339 10.1016/S0091-679X(02)69021-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertet C., Sulak L., Lecuit T. (2004). Myosin-dependent junction remodelling controls planar cell intercalation and axis elongation. Nature 429, 667–671 10.1038/nature02590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berx G., van Roy F. (2009). Involvement of members of the cadherin superfamily in cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a003129 10.1101/cshperspect.a003129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggon T. J., Murray J., Chappuis–Flament S., Wong E., Gumbiner B. M., Shapiro L. (2002). C-cadherin ectodomain structure and implications for cell adhesion mechanisms. Science 296, 1308–1313 10.1126/science.1071559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady–Kalnay S. M., Rimm D. L., Tonks N. K. (1995). Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPmu associates with cadherins and catenins in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 130, 977–986 10.1083/jcb.130.4.977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavey M., Rauzi M., Lenne P. F., Lecuit T. (2008). A two-tiered mechanism for stabilization and immobilization of E-cadherin. Nature 453, 751–756 10.1038/nature06953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Zarnitsyna V. I., Sarangapani K. K., Huang J., Zhu C. (2008). Measuring receptor-ligand binding kinetics on cell surfaces: from adhesion frequency to thermal fluctuation methods. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 1, 276–288 10.1007/s12195-008-0024-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Gumbiner B. M. (2006). Paraxial protocadherin mediates cell sorting and tissue morphogenesis by regulating C-cadherin adhesion activity. J. Cell Biol. 174, 301–313 10.1083/jcb.200602062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesla S. E., Selvaraj P., Zhu C. (1998). Measuring two-dimensional receptor-ligand binding kinetics by micropipette. Biophys. J. 75, 1553–1572 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74074-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien Y. H., Jiang N., Li F., Zhang F., Zhu C., Leckband D. (2008). Two stage cadherin kinetics require multiple extracellular domains but not the cytoplasmic region. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1848–1856 10.1074/jbc.M708044200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra A., Tabdanov E., Patel H., Janmey P. A., Kresh J. Y. (2011). Cardiac myocyte remodeling mediated by N-cadherin-dependent mechanosensing. Am. J. Physiol. 300, H1252–H1266 10.1152/ajpheart.00515.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danowski B. A. (1989). Fibroblast contractility and actin organization are stimulated by microtubule inhibitors. J. Cell Sci. 93, 255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplazes J., Fuchs M., Rauser S., Genth H., Lengyel E., Busch R., Luber B. (2009). Rac1 and Rho contribute to the migratory and invasive phenotype associated with somatic E-cadherin mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 3632–3644 10.1093/hmg/ddp312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudko O. K., Mathé J., Szabo A., Meller A., Hummer G. (2007). Extracting kinetics from single-molecule force spectroscopy: nanopore unzipping of DNA hairpins. Biophys. J. 92, 4188–4195 10.1529/biophysj.106.102855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguay D., Foty R. A., Steinberg M. S. (2003). Cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and tissue segregation: qualitative and quantitative determinants. Dev. Biol. 253, 309–323 10.1016/S0012-1606(02)00016-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumaswala U. J., Wilson M. J., José T., Daleke D. L. (1996). Glutamine- and phosphate-containing hypotonic storage media better maintain erythrocyte membrane physical properties. Blood 88, 697–704 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler A., Bacakova L., Newman C., Hategan A., Griffin M., Discher D. (2004). Substrate compliance versus ligand density in cell on gel responses. Biophys. J. 86, 617–628 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74140-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E., Ritchie K. (1997). Dynamic strength of molecular adhesion bonds. Biophys. J. 72, 1541–1555 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78802-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E., Leung A., Heinrich V., Zhu C. (2004). Mechanical switching and coupling between two dissociation pathways in a P-selectin adhesion bond. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11281–11286 10.1073/pnas.0401870101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foty R. A., Steinberg M. S. (2004). Cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion and tissue segregation in relation to malignancy. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48, 397–409 10.1387/ijdb.041810rf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foty R. A., Steinberg M. S.2005a). The differential adhesion hypothesis: a direct evaluation. Dev. Biol. 278, 255–263 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foty R. A., Pfleger C M., Forgacs G., Steinberg M. S.1996). Surface tensions of embryonic tissues predict their mutual envelopment behavior. Development 122, 1611–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander D. R., Mège R. M., Cunningham B. A., Edelman G. M. (1989). Cell sorting-out is modulated by both the specificity and amount of different cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) expressed on cell surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 7043–7047 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B., Spatz J. P., Bershadsky A. D. (2009). Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 21–33 10.1038/nrm2593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt D., Tepass U. (1998). Drosophila oocyte localization is mediated by differential cadherin-based adhesion. Nature 395, 387–391 10.1038/26493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold E. R., Fudenberg H. H. (1967). Chromic chloride: a coupling reagent for passive hemagglutination reactions. J. Immunol. 99, 859–866 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner B. M. (2005). Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 622–634 10.1038/nrm1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C., Schwartz M. A. (2009). Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 53–62 10.1038/nrm2596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison O. J., Bahna F., Katsamba P. S., Jin X., Brasch J., Vendome J., Ahlsen G., Carroll K. J., Price S. R., Honig B., et al. (2010). Two-step adhesive binding by classical cadherins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 348–357 10.1038/nsmb.1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Carthew R. W. (2004). Surface mechanics mediate pattern formation in the developing retina. Nature 431, 647–652 10.1038/nature02952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellberg C. B., Burden–Gulley S. M., Pietz G. E., Brady–Kalnay S. M. (2002). Expression of the receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase, PTPmu, restores E-cadherin-dependent adhesion in human prostate carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11165–11173 10.1074/jbc.M112157200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenfeldt S., Erisken S., Carthew R. W. (2008). Physical modeling of cell geometric order in an epithelial tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 907–911 10.1073/pnas.0711077105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Edwards L. J., Evavold B. D., Zhu C. (2007). Kinetics of MHC-CD8 interaction at the T cell membrane. J. Immunol. 179, 7653–7662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Zarnitsyna V. I., Liu B., Edwards L. J., Jiang N., Evavold B. D., Zhu C. (2010). The kinetics of two-dimensional TCR and pMHC interactions determine T-cell responsiveness. Nature 464, 932–936 10.1038/nature08944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käfer J., Hayashi T., Marée A. F., Carthew R. W., Graner F. (2007). Cell adhesion and cortex contractility determine cell patterning in the Drosophila retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 18549–18554 10.1073/pnas.0704235104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasza K. E., Zallen J. A. (2011). Dynamics and regulation of contractile actin-myosin networks in morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 30–38 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsamba P., Carroll K., Ahlsen G., Bahna F., Vendome J., Posy S., Rajebhosale M., Price S., Jessell T. M., Ben–Shaul A., et al. (2009). Linking molecular affinity and cellular specificity in cadherin-mediated adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11594–11599 10.1073/pnas.0905349106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofler R., Wick G. (1977). Some methodologic aspects of the chromium chloride method for coupling antigen to erythrocytes. J. Immunol. Methods 16, 201–209 10.1016/0022-1759(77)90198-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg M., Arboleda–Estudillo Y., Puech P. H., Käfer J., Graner F., Müller D. J., Heisenberg C. P. (2008). Tensile forces govern germ-layer organization in zebrafish. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 429–436 10.1038/ncb1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladoux B., Anon E., Lambert M., Rabodzey A., Hersen P., Buguin A., Silberzan P., Mège R. M. (2010). Strength dependence of cadherin-mediated adhesions. Biophys. J. 98, 534–542 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer M. D., Guo H. B., Shashikanth N., Pierce M., Leckband D. (2012). N-glycosylation alters the dynamics of N-cadherin junction assembly. J. Cell Sci. 1252478–2485 10.1242/jcs.101147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Duc Q., Shi Q., Blonk I., Sonnenberg A., Wang N., Leckband D., de Rooij J. (2010). Vinculin potentiates E-cadherin mechanosensing and is recruited to actin-anchored sites within adherens junctions in a myosin II-dependent manner. J. Cell Biol. 189, 1107–1115 10.1083/jcb.201001149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leader W. M., Stopak D., Harris A. K. (1983). Increased contractile strength and tightened adhesions to the substratum result from reverse transformation of CHO cells by dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate. J. Cell Sci. 64, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit T. (2005). Adhesion remodeling underlying tissue morphogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 34–42 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit T., Le Goff L. (2007). Orchestrating size and shape during morphogenesis. Nature 450, 189–192 10.1038/nature06304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit T., Lenne P. F. (2007). Cell surface mechanics and the control of cell shape, tissue patterns and morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 633–644 10.1038/nrm2222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit T., Lenne P. F., Munro E. (2011). Force generation, transmission, and integration during cell and tissue morphogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 157–184 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Tan J. L., Cohen D. M., Yang M. T., Sniadecki N. J., Ruiz S. A., Nelson C. M., Chen C. S. (2010). Mechanical tugging force regulates the size of cell-cell junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9944–9949 10.1073/pnas.0914547107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M., Zhao H., Huang K. S., Zhu C. (2001). Kinetic measurements of cell surface E-selectin/carbohydrate ligand interactions. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 29, 935–946 10.1114/1.1415529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu O., David R., Ninomiya H., Winklbauer R. (2011). Large-scale mechanical properties of Xenopus embryonic epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4000–4005 10.1073/pnas.1010331108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M. L., Foty R. A., Steinberg M. S., Schoetz E. M. (2010). Coaction of intercellular adhesion and cortical tension specifies tissue surface tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12517–12522 10.1073/pnas.1003743107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan R. W., Yap A. S. (2011). Protein tyrosine phosphatase activity is necessary for E-cadherin-activated Src signaling. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 68, 32–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monier B., Pelissier–Monier A., Brand A. H., Sanson B. (2010). An actomyosin-based barrier inhibits cell mixing at compartmental boundaries in Drosophila embryos. Nat. Cell. Biol. 12, 60–65; sup pp. 1–9 10.1038/ncb2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill J. W. (1988). Testing for lack of fit in nonlinear regression. Ann. Stat. 16, 733–740 10.1214/aos/1176350831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen C. M., Gumbiner B. M. (2002). Cadherin-mediated cell sorting not determined by binding or adhesion specificity. J. Cell Biol. 156, 389–399 10.1083/jcb.200108040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen C. M., Leckband D., Yap A. S. (2011). Tissue organization by cadherin adhesion molecules: dynamic molecular and cellular mechanisms of morphogenetic regulation. Physiol. Rev. 91, 691–731 10.1152/physrev.00004.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose A., Nagafuchi A., Takeichi M. (1988). Expressed recombinant cadherins mediate cell sorting in model systems. Cell 54, 993–1001 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90114-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose A., Tsuji K., Takeichi M. (1990). Localization of specificity determining sites in cadherin cell adhesion molecules. Cell 61, 147–155 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90222-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panorchan P., Thompson M. S., Davis K. J., Tseng Y., Konstantopoulos K., Wirtz D. (2006). Single-molecule analysis of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. J. Cell Sci. 119, 66–74 10.1242/jcs.02719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papusheva E., Heisenberg C. P. (2010). Spatial organization of adhesion: force-dependent regulation and function in tissue morphogenesis. EMBO J. 29, 2753–2768 10.1038/emboj.2010.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrais M., Chen X., Perez–Moreno M., Gumbiner B. M. (2007). E-cadherin homophilic ligation inhibits cell growth and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling independently of other cell interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 2013–2025 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret E., Leung A., Feracci H., Evans E. (2004). Trans-bonded pairs of E-cadherin exhibit a remarkable hierarchy of mechanical strengths. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16472–16477 10.1073/pnas.0402085101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakasam A. K., Maruthamuthu V., Leckband D. E. (2006). Similarities between heterophilic and homophilic cadherin adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15434–15439 10.1073/pnas.0606701103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauzi M., Lenne P. F., Lecuit T. (2010). Planar polarized actomyosin contractile flows control epithelial junction remodelling. Nature 468, 1110–1114 10.1038/nature09566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L., Weis W. I. (2009). Structure and biochemistry of cadherins and catenins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a003053 10.1101/cshperspect.a003053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q., Chien Y. H., Leckband D. (2008). Biophysical properties of cadherin bonds do not predict cell sorting. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28454–28463 10.1074/jbc.M802563200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibamoto S., Hayakawa M., Takeuchi K., Hori T., Oku N., Miyazawa K., Kitamura N., Takeichi M., Ito F. (1994). Tyrosine phosphorylation of beta-catenin and plakoglobin enhanced by hepatocyte growth factor and epidermal growth factor in human carcinoma cells. Cell Adhes. Commun. 1, 295–305 10.3109/15419069409097261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M. S. (1962). On the mechanism of tissue reconstruction by dissociated cells. I. Population kinetics, differential adhesiveness. and the absence of directed migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 48, 1577–1582 10.1073/pnas.48.9.1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M. S. (1963). Reconstruction of tissues by dissociated cells. Some morphogenetic tissue movements and the sorting out of embryonic cells may have a common explanation. Science 141, 401–408 10.1126/science.141.3579.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M. S., Takeichi M. (1994). Experimental specification of cell sorting, tissue spreading, and specific spatial patterning by quantitative differences in cadherin expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 206–209 10.1073/pnas.91.1.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M. S. (2007). Differential adhesion in morphogenesis: a modern view. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17, 281–286 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M. S., Gilbert S. F. (2004). Townes and Holtfreter (1955): directed movements and selective adhesion of embryonic amphibian cells. J. Exp. Zool. A Comp. Exp. Biol. 301, 701–706 10.1002/jez.a.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabdili H., Barry A. K., Langer M. D., Chien Y-H., Shi Q., Lee K. J., Leckband D. E. (2012). Cadherin point mutations alter cell sorting and modulate GTPase signaling. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3299–3309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi M., Inuzuka H., Shimamura K., Fujimori T., Nagafuchi A. (1990). Cadherin subclasses: differential expression and their roles in neural morphogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 55, 319–325 10.1101/SQB.1990.055.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveau J. C., Dubois M., Le Bihan O., Trépout S., Almagro S., Hewat E., Durmort C., Heyraud S., Gulino–Debrac D., Lambert O. (2008). Structure of artificial and natural VE-cadherin-based adherens junctions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 189–193 10.1042/BST0360189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U., Godt D., Winklbauer R. (2002). Cell sorting in animal development: signalling and adhesive mechanisms in the formation of tissue boundaries. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 572–582 10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00342-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townes P. L., Holtfreter J. (1955). Directed movements and selective adhesion of embryonic amphibian cells. J. Exp. Zool. 128, 53–120 10.1002/jez.1401280105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzima E., Irani–Tehrani M., Kiosses W. B., Dejana E., Schultz D. A., Engelhardt B., Cao G., DeLisser H., Schwartz M. A. (2005). A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature 437, 426–431 10.1038/nature03952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendome J., Posy S., Jin X., Bahna F., Ahlsen G., Shapiro L., Honig B. (2011). Molecular design principles underlying β-strand swapping in the adhesive dimerization of cadherins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 693–700 10.1038/nsmb.2051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. J., Williams G., Howell F. V., Skaper S. D., Walsh F. S., Doherty P. (2001). Identification of an N-cadherin motif that can interact with the fibroblast growth factor receptor and is required for axonal growth. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43879–43886 10.1074/jbc.M105876200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonemura S., Wada Y., Watanabe T., Nagafuchi A., Shibata M. (2010). alpha-Catenin as a tension transducer that induces adherens junction development. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 533–542 10.1038/ncb2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Marcus W. D., Goyal N. H., Selvaraj P., Springer T. A., Zhu C. (2005). Two-dimensional kinetics regulation of alphaLbeta2-ICAM-1 interaction by conformational changes of the alphaL-inserted domain. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42207–42218 10.1074/jbc.M510407200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.