Abstract

Constructs containing the cDNAs encoding the primary leaf catalase in Nicotiana or subunit 1 of cottonseed (Gossypium hirsutum) catalase were introduced in the sense and antisense orientation into the Nicotiana tabacum genome. The N. tabacum leaf cDNA specifically overexpressed CAT-1, the high catalytic form, activity. Antisense constructs reduced leaf catalase specific activities from 0.20 to 0.75 times those of wild type (WT), and overexpression constructs increased catalase specific activities from 1.25 to more than 2.0 times those of WT. The NADH-hydroxypyruvate reductase specific activity in transgenic plants was similar to that in WT. The effect of antisense constructs on photorespiration was studied in transgenic plants by measuring the CO2 compensation point (Γ) at a leaf temperature of 38°C. A significant linear increase was observed in Γ with decreasing catalase (at 50% lower catalase activity Γ increased 39%). There was a significant temperature-dependent linear decrease in Γ in transgenic leaves with elevated catalase compared with WT leaves (at 50% higher catalase Γ decreased 17%). At 29°C, Γ also decreased with increasing catalase in transgenic leaves compared with WT leaves, but the trend was not statistically significant. Rates of dark respiration were the same in WT and transgenic leaves. Thus, photorespiratory losses of CO2 were significantly reduced with increasing catalase activities at 38°C, indicating that the stoichiometry of photorespiratory CO2 formation per glycolate oxidized normally increases at higher temperatures because of enhanced peroxidation.

About 90% of the dry weight of plants is derived from CO2 assimilated by the Rubisco reaction during photosynthesis. This enzyme also catalyzes a reaction with oxygen that leads to the formation of phosphoglycolate and glycolate. The latter is metabolized by the photorespiratory pathway with the production of CO2 in C3 plants (Tolbert, 1980). Photorespiration can be considered wasteful because it consumes ATP, and the CO2 released must be fixed again within the leaf. Therefore, a number of laboratories have attempted to reduce photorespiration by genetically regulating critical biochemical reactions in leaves by altering the CO2/O2 specificity (Ogren, 1984; Chen et al., 1990), or by screening for photorespiratory mutants (Somerville and Ogren, 1979; Zelitch, 1989; Lea and Blackwell, 1990).

Based on enzymatic studies, it has been estimated that 25% of the glycolate metabolized during photorespiration is released as CO2 at 25°C (Jordan and Ogren, 1983). There is evidence that the stoichiometry of the CO2 produced per mole of glycolate oxidized increases, however, under conditions favoring rapid photorespiration, such as increased O2 and temperature (Grodzinski and Butt, 1977; Hanson and Peterson, 1985, 1986). The stoichiometry could also change in leaves with insufficient catalase activity, because excess H2O2 may rapidly decarboxylate ketoacids such as hydroxypyruvate and glyoxylate to generate additional CO2 (Zelitch, 1992a). This additional loss of assimilated CO2 might be avoided with higher catalase (EC 1.11.1.6) activity, thereby reestablishing the stoichiometry closer to 25% and increasing net photosynthesis.

The relation of catalase activity to net photosynthesis was supported by studies with a tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) mutant selected by screening for superior growth at elevated, near-lethal O2 levels (Zelitch, 1992a), in which a correlation was obtained between elevated catalase and decreased photorespiration. The mutant had catalase activity 1.4 times that of WT, a higher level of catalase protein, and increased net photosynthesis when photorespiration was rapid, such as at elevated temperature or O2 levels (Zelitch, 1989; Zelitch et al., 1991).

In addition to the catalatic reaction (2H2O2 → O2 + 2H2O), catalase can use H2O2 to oxidize organic substrates such as ethanol to acetaldehyde (H2O2 + CH3CH2OH → CH3CHO + 2H2O). The latter represents the peroxidatic activity of catalase. Catalases of tobacco are encoded by a small gene family (Willekens et al., 1994). Catalases with high catalatic activity (CAT-1) are the major isoforms in leaves, and there is relatively less CAT-1 in stem and sepal tissue (Havir et al., 1996).

From leaf libraries we have cloned and characterized a partial cDNA encoding CAT-1 in Nicotiana sylvestris and a full-length clone in N. tabacum (Schultes et al., 1994). To modify catalase expression in tobacco leaves and investigate the physiological role of catalase on photosynthesis, these tobacco cDNA clones and those encoding cottonseed (Gossypium hirsutum) CAT-1 (Ni et al., 1990) were fused to the constitutive CaMV 35S promoter (Rodermel et al., 1988) in the sense and antisense orientation. A cDNA clone was also inserted in the sense orientation with a chimeric promoter that combined elements from the CaMV 35S and the mannopine synthase promoters (Comai et al., 1990). Transgenic plants were analyzed for catalase activities, seedling growth with kanamycin, and NPTII cDNA (kanamycin resistance) inserts. In the present study we used a population of transgenic plants with catalase specific activities ranging from 0.20 to more than 2.0 times those of WT plants to study further the function of catalase in photorespiration. We describe the generation of transgenic plants and the stability of catalase activity over generations, and we demonstrate that in transgenic plants with reduced catalase activity, there was a significant increase in Γ. Conversely, in plants with increased catalase, Γ was significantly reduced in a temperature-dependent manner. Our findings add further support for a physiological role of catalase in photorespiration and net photosynthesis at higher temperatures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Seeds of WT tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv Havana) Seed used for transformations were surface sterilized by a 2-min treatment in 70% ethanol and 10 to 25 min in 1.3% sodium hypochlorite solution containing 0.025% Tween 20. The seeds were rinsed twice (5 min each time) in sterile distilled water and air dried. They were germinated on sterile Petri plates containing Murashige and Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) without Suc or vitamins in 0.25% Phytagel (Sigma) in a growth room in continuous light (100 μmol photons m−2 s−1) at 28°C. Transgenic plants were first grown in the growth room and then transferred to a commercial potting mix and grown in a greenhouse, ultimately in 10.6-L plastic pots. Greenhouse plants were fertilized with a complete nutrient solution and grown at a minimum air temperature of 18°C, whereas day temperatures often ranged between 25 and 41°C.

To determine kanamycin-resistant growth in seedling progeny of selfed transgenic plants, seeds were surface sterilized as described above, and about 25 seeds were allowed to germinate on sterile Petri plates containing Murashige and Skoog medium in 0.25% Phytagel (Sigma) with 1% Suc, vitamins, and 75 or 100 μg of kanamycin/mL. Plants were scored in comparison with untreated plants after 3 to 4 weeks in the growth room under the conditions described above.

Plasmid Constructs

Plasmids listed in Table I represent catalase sequences placed in plasmids under the control of either the CaMV 35S or the “Big Mac” promoter in the sense or antisense orientation (Comai et al., 1990). The Big Mac promoter contains hybrid CaMV 35S and mannopine synthase promoter sequences and was used to obtain overexpression. All plasmids containing the Nicotiana sylvestris catalase cDNA clone (pBZ1) were derived from pZZ1.4 (Zelitch et al., 1991). Plasmids containing cottonseed (Gossypium hirsutum) catalase cDNA encoding for subunit 1 (pBZ4 and pBZ5) were obtained from pC9 (Ni et al., 1990). The plasmids containing N. tabacum CAT-1 sequences (pBZ2, pBZ3, pBZ8, pBZ6, and pBZ7) were all derived from pZ2A and pZ2S (Schultes et al., 1994). Constructs pBZ1, pBZ2, pBZ4, pBZ5, pBZ6, and pBZ7 used the binary vector pAC1352L (Rodermel et al., 1988). These vectors include a CaMV 35S promoter/terminator cassette as well as the NPTII gene, which is driven by the nopaline synthase promoter and confers kanamycin resistance, and was used in Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Constructs pBZ3 and pBZ8 were derived from pCGN7366, which contains the Big Mac promoter and is similar to pCGN7329 (Comai et al., 1990).

Table I.

Plasmids used for the production of transgenic plants and leaf catalase (CAT) specific activity in different constructs with underexpressed and overexpressed CAT activities

| Plasmid | Promoter | CAT cDNA Insert | cDNA Orientation | Mean CAT Specific Activity for Construct | Plant Nos. | Mean CAT Specific Activity for Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kb | Ratio transgenic:WT | Ratio transgenic:WT | |||||

| pBZ1 | CaMV 35S | N. sylvestris | 0.7 | AS | 0.63 ± 0.05 (n = 15) | 2.1E | 0.71 ± 0.09 |

| 2.2A | 0.62 ± 0.01 | ||||||

| 2.3B | 0.66 ± 0.06 | ||||||

| 4.7D | 0.62 ± 0.01 | ||||||

| pBZ2 | CaMV 35S | N. tabacum | 1.9 | S | 1.50 ± 0.13 (n = 5) | 10.55 | 1.54 ± 0.34 |

| Sa | 0.47 ± 0.09 (n = 2)a | 10.33 | 0.41 ± 0.22 | ||||

| pBZ8 | Big Mac | N. tabacum | 1.9 | S | 1.53 ± 0.09 (n = 4)b | 9.5 | 1.41 ± 0.13 |

| S | 2.05 ± 0.11 (n = 4)b | 9.8 | 2.04 ± 0.19 | ||||

| pBZ4 | CaMV 35S | Cottonseed | 1.8 | (AS)c | 0.43 ± 0.17 (n = 3) | 5.13.13 | 0.24 ± 0.05 |

| pBZ5 | CaMV 35S | Cottonseed | 1.8 | (S)c | 1.36 ± 0.11 (n = 3) | 5.13.3 | 1.25 ± 0.06 |

| pBZ6 | CaMV 35S | N. tabacum | 1.9 | (AS)c | 0.46 ± 0.14 (n = 9) | 7.2.3 | 0.41 ± 0.08 |

| pBZ7 | CaMV 35S | N. tabacum | 1.9 | (S)c | 1.38 ± 0.08 (n = 3) | 7.5.1 | 1.47 ± 0.21 |

| pAC1352L | CaMV 35S | None | 6.19.1 | 1.08d | |||

Further details about the constructs are given in Methods. The cDNAs from N. sylvestris, N. tabacum, and cottonseed were used in antisense (AS) and sense (S) constructs. Catalase specific activities, almost all on greenhouse-grown plants, were expressed as units per milligram soluble protein compared with comparable WT leaves sampled at the same time. The number of transformed plants with altered catalase specific activity found for each construct is shown with the mean specific activity of the individual plant means and the sd. The mean catalase specific activities (± sd) are shown in column 7 for examples of individual transformed plants relative to WT, representing two or three determinations made on different leaves on each plant at intervals of at least 1 week.

Two transgenic plants constructed in the sense orientation showed decreased catalase activity, presumably because of the phenomenon of co-suppression.

Four plants containing the Big Mac promoter had increased leaf catalase activity averaging about 1.5 times that of WT, and four others had increased catalase activity of approximately 2.05 times that of WT. Some plants showed mean leaf overexpression relative to WT (± sd) at early stages of growth (plant 9.7, 1.94 ± 0.17; n = 2), some at later stages (plant 9.1, 1.59 ± 0.28; n = 2), and most at all stages of growth (plant 9.4, 2.20 ± 0.43; n = 3; plant 9.5, 1.41 ± 0.13; n = 3; plant 9.8, 2.04 ± 0.19; n = 3; plant 9.11, 2.02 ± 0.51; n = 3; and plant 9.41, 1.61 ± 0.23; n = 2).

These transgenic plants were constructed with catalase cDNA inserts that would produce either a sense or an antisense orientation, and individuals were identified by their display of elevated or reduced levels of catalase specific activity. Thus, AS and S reflect depressed or elevated catalase activity, respectively.

A transgenic plant containing the pAC1352L vector without any catalase DNA insert had catalase activity within 1 sd of the mean of WT plants assayed at the same time.

Plasmid pBZ1 was constructed by cloning a 0.7-kb fragment of N. sylvestris catalase cDNA, cut with HindIII/EcoRI from pZZ1.4, into pAC1352L to obtain the catalase sequences in the antisense orientation relative to the CaMV 35S promoter. Plasmid pBZ2 was constructed by cloning a 1.9-kb N. tabacum cDNA fragment cut with SalI/SmaI from pZ2S and into pAC1352L to obtain catalase sequences in the sense orientation relative to the CaMV 35S promoter. Plasmid pBZ3 was obtained by replacing the SacI/SmaI GUS-encoding sequences in pCGN7366 with a SacI/HincII 1.9-kb N. tabacum catalase sequence from pZ2S to obtain catalase sequences in the sense orientation relative to the Big Mac promoter. The XhoI fragment from pBZ3 (containing the Big Mac and catalase sequences) was cloned into the SalI site of the binary vector pBIN19 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) to create pBZ8.

For plasmids pBZ4 and pBZ5, the 1.8-kb EcoRI cotton catalase sequence pC9 was cloned into the EcoRI site of pAC1352L. For plasmids pBZ6 and pBZ7, the 1.9-kb tobacco catalase fragment pZ2A was similarly cloned into the EcoRI site of pAC1352L. Five cotton catalase-containing plasmids and five tobacco catalase-containing plasmids in pAC1352L were introduced into A. tumefaciens. Each construct was independently transformed into plants. These ligations resulted in either sense or antisense constructs, and were identified by measuring leaf catalase specific activity in transgenic plants and comparing it with the specific activity in WT plants.

Plant Transformations

Plasmids with and without catalase DNA insertions were transformed into A. tumefaciens (strain GV2260 supplied by Alice Cheung, Yale University, New Haven, CT) by triparental mating. Tobacco (cv Havana Seed) leaf discs were transformed according to the work of Horsch et al. (1985), and transgenic plants were regenerated on Murashige and Skoog medium with added naphthalene acetic acid (0.5 μg/mL), 6-benzylaminopurine (1.0 μg/mL), kanamycin (50–75 μg/mL), and cefotaxime (125 μg/mL). Transformed explants were transferred to a rooting medium (Murashige and Skoog medium with kanamycin and without hormones), and those kanamycin-resistant plantlets that developed a good root system within 1 week were planted in commercial potting mix. About 50 to 100 transgenic plants per construct were analyzed for their catalase activity, as described below, and plants showing overexpression and underexpression were assayed several times at intervals of 1 week or more. They were further tested for the presence of NPTII by Southern-blot analysis on leaf genomic DNA using pYU179 (obtained from Stephen L. Dellaporta, Yale University) as a probe.

Catalase and NADH-Hydroxypyruvate Reductase Specific Activity

Expanding leaves that were selected were generally not less than 15 cm long (area, 100 cm2; fresh weight, 2 g), and two 0.8-cm discs were cut from the tip-half region to obtain the greatest catalase activity (Zelitch, 1992b). The leaf discs were placed in microfuge tubes and immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −70°C. They were stored for as long as 2 weeks without loss of activity, and four samples at a time were thawed on ice and extracted in 0.4 mL of buffer (potassium phosphate, 50 mm at pH 7.4, containing 10 mm DTT) for assay. The catalase enzyme activity in extracts was assayed spectrophotometrically, based on the initial rate of H2O2 breakdown (Havir and McHale, 1987; Zelitch, 1989). One enzyme unit is defined as the activity catalyzing the decomposition of 1 μmol of H2O2 per min under standard conditions at 30°C. The peroxidatic activity of catalase was assayed based on the rate of oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde in the presence of H2O2 (Havir et al., 1996). Protein concentrations were determined with Coomassie blue reagent (Bio-Rad) using BSA as a standard.

To identify transgenic plants with altered levels of catalase specific activity, assays were conducted on different leaves of each plant at intervals of at least 1 week, and specific activities (units per milligram of protein) were compared with assays made on at least four WT plants of similar size sampled at the same time. The mean catalase specific activities for WT leaves ranged from 200 to 350 units/mg protein in different experiments, and the values were lower in winter than in summer, as has previously been observed for greenhouse-grown plants (Zelitch, 1990b). However, on a given day the sd for WT plants was generally not greater than 15% from the mean. Thus, transgenic plants with altered catalase phenotypes were selected if they were consistently at least ± 30% from the WT mean (more than 2 sd, or 94% of all observations) on at least two sampling days 1 week apart.

NADH-hydroxypyruvate reductase assays were carried on leaf extracts used for catalase determinations after each set of four catalase assays was completed (Zelitch, 1990a). The reaction mixture consisted of 167 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.4), 0.05 mm NADH, and enzyme extract. The rate of NADH oxidation was measured at 340 nm at 30°C for 1 min upon addition of 1 mm lithium hydroxypyruvate. One unit was defined as the activity catalyzing the reduction of 1 μmol of hydroxypyruvate per min.

DNA and RNA Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from leaf samples frozen in liquid N2 (Tai and Tanksley, 1990). Samples of DNA were digested with EcoRI for a minimum of 5 h, fractionated by electrophoresis in 0.8 or 1% agarose gels, and transferred to a Nytran (Schleicher & Schuell) or Zeta-Probe (Bio-Rad) nylon membrane treated as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). Membranes were prehybridized for 1 to 2 h in Church buffer (Church and Gilbert, 1984) or Denhardt's reagent (Sambrook et al., 1989), and labeled cDNA coding for the constitutive neomycin phosphotransferase gene pYU179 (provided by Stephen L. Dellaporta, Yale University) or the leaf catalase gene (Schultes et al., 1994) was then added directly to the buffer. Membranes were hybridized for 12 to 24 h at 65°C, washed in several changes of 1× and 0.1× SSC with 1% SDS, and exposed to x-ray film.

Leaf samples were taken for RNA analysis at the same time or within 24 h after discs were taken for catalase activity. The RNA samples were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −70°C until analyzed. Total RNA was isolated from frozen material using the guanidinium thiocyanate method (Mehdy and Lamb, 1987), and RNAs were separated by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel containing 6.5% formaldehyde and transferred to a Nytran membrane. Filters were then UV cross-linked, heated at 80°C for 2 h, prehybridized in Church buffer (Church and Gilbert, 1984), hybridized overnight with randomly labeled cDNA coding for the N. tabacum catalase gene (Schultes et al., 1994), and washed as described above for DNA analysis. To assess RNA quality and quantity, a N. sylvestris SSu probe was used (a gift of Alice Cheung, Yale University). The quantitative intensity was determined by applying densitometry to video images of the blots.

Catalase Isozymes in Stem and Sepal Tissue

Mature plants were used that had already produced brown seed pods on some inflorescences. At least 18 g of outer green stem tissue was collected from WT and transgenic plants growing in a greenhouse by using a vegetable peeler, and at least 4 g of green sepal tissue was taken. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and ground in a mortar. Extraction and preparation of samples for chromatofocusing were carried out (Havir and McHale, 1990) using a pH gradient from 8.0 to 5.0 on a 1.2 × 22-cm column of PBE 94 polybuffer exchanger (Pharmacia). Fractions of 3.5 mL were collected and assayed for catalase activity as described above.

CO2 Compensation Point and Dark Respiration

Because the Γ may vary considerably, depending on the age of the leaf and the position of the leaf on the stalk, and because values for C3 leaves between 40 and 100 μL CO2 L−1 at 25°C have been reported (Tichá and Catský, 1981), all determinations were made on transgenic and WT plants grown in the same environment and sampled from similar leaf positions at the same time. Leaf discs, 1.6 cm in diameter, floated on water have constant rates of net photosynthesis for many hours (Zelitch, 1989) and exhibit the O2 inhibition of net CO2 assimilation found in whole leaves (Zelitch, 1990b).

Two 1.6-cm leaf discs, excised in late morning on sunny days from the tip-half region of WT or transgenic plants in the T2 generation, were placed upside down on 1.0 mL of water in a 50-mL syringe the tip of which was sealed with a rubber serum stopper. Syringes were placed in constant-temperature chambers in the light (100 μmol photons m−2 s−1) with the leaf temperatures inside the syringe maintained at 38 ± 0.5°C or 29 ± 0.5°C as determined with a thermistor thermometer placed on a leaf disc in a separate syringe. Gas samples (5 mL) were withdrawn from the syringe through the serum stopper. They were injected into a IR CO2 gas analyzer (model 865, Beckman) after 90 min and at 30-min intervals thereafter to ensure that a steady-state CO2 concentration was obtained (± 5%). This method of determining Γ showed clear differences between C3 and C4 leaf segments (Schultes et al., 1996). At the same time that discs were taken for Γ determination, or within 24 h, two 0.8-cm leaf discs were taken from nearby positions on the same leaves and their catalase specific activities were determined as described above.

Dark-respiration rates were measured in some experiments after determination of Γ at 38°C in transgenic and WT leaf tissue after turning off the light in the chambers. The leaf temperature in the dark was maintained at 36 ± 0.5°C, and rates of CO2 evolution in transgenic and WT plant tissue were determined by measuring the CO2 concentrations in the 50-mL syringes after 15 min of darkness (0 time), and for two 10-min intervals thereafter.

RESULTS

Catalase Activity in Transgenic Plants

A population of transgenic tobacco plants was generated exhibiting a wide range of leaf catalase activity using cDNAs corresponding to the catalase gene of N. sylvestris, N. tabacum, and G. hirsutum. The partial or entire coding region of the catalase gene was fused to the CaMV 35S or the Big Mac promoter (Table I). These transgenes as well as a negative control consisting of the plasmid without any catalase insert were introduced into N. tabacum cv Havana Seed leaf discs through a transformation with A. tumefaciens.

Transgenic plants were first selected by their ability to grow on selective medium (Murashige and Skoog with kanamycin). Transgenic families with antisense constructs and low catalase activity grew poorly in the presence of kanamycin (100 μg/mL) in normal air, even though NPTII was present, but growth usually improved and plants recovered in 1% CO2 when photorespiration was eliminated. Thus, a greatly reduced level of catalase activity appeared to increase the sensitivity of the plants to higher levels of kanamycin in normal air.

Leaf genomic DNAs of plants with kanamycin resistance and altered specific activity of leaf catalase were also screened for the presence of NPTII. Southern-blot analysis of EcoRI-digested DNA showed that plants with altered catalase activity contained one or more copies of NPTII, and the location of the bands hybridizing with a NPTII probe varied in different transformants. Transformed plants contained additional bands hybridizing with our leaf catalase probe that were not present in untransformed control plants (data not shown). Some plants containing NPTII had catalase activities similar to untransformed plants (see Table II).

Table II.

Characteristics of some T2 progeny obtained by selfing transformants with elevated and reduced levels of leaf catalase specific activities

| Plant No. Selfed | Plasmid | Kan-Resistant Seedling Growth | Progeny with CAT Specific Activity Different from WT | Mean Change in CAT Specific Activity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n tested | % resistant | n assayed | % altered CAT | Ratio transgenic:WT | ||

| 2.1E | pBZ1 | 19 | 63 | 12 | 17 | 0.60 ± 0.07 |

| 2.2Aa | pBZ1 | 21 | 57 | 23 | 17 | 0.44 ± 0.06 |

| 2.3B | pBZ1 | 35 | 49 | 10 | 20 | 0.43 ± 0.06 |

| 4.7Da | pBZ1 | 61 | 89 | 54 | 11 | 0.62 ± 0.09 |

| 7.2.3 | pBZ6 | 98 | 57 | 15 | 20 | 0.61 ± 0.09 |

| 10.33b | pBZ2b | 20 | 100 | 13 | 8 | 0.52 ± 0.07 |

| 9.8 | pBZ8 | 79 | 41 | 28 | 32 | 1.74 ± 0.13 |

| 9.11 | pBZ8 | 68 | 59 | 12 | 25 | 1.76 ± 0.11 |

| 6.19.1 | pAC1352L | 60 | 93 | |||

| WT | 219 | 4 | ||||

The plasmids (Table I) are defined in Methods. Kanamycin (Kan)-resistant growth of seedlings was determined as described in the text. The number of seedlings examined for Kan-resistant growth (75 or 100 μg/mL) in each family, the number of randomly selected plants (without testing for Kan resistance) assayed for leaf catalase specific activity in each family, and the percentage that clearly differed from WT (± sd) of the means are shown.

The presence of NPTII was confirmed by Southern-blot analysis on all selfed progeny of plant 2.2A and plant 4.7D, which showed alteration from WT in leaf catalase specific activity, although siblings with WT catalase activity also frequently gave positive signals.

The parent plant 10.33 had decreased catalase activity presumably because of co-suppression (Table I).

The range of catalase activities in different transformed families relative to WT plants is shown in Table I. WT plants generally showed a sd within 15% of the mean (see Methods). Specific activities from 0.20 to 0.75 times those of WT plants were obtained with the antisense constructs, and activities less than 0.5 times those of WT plants were observed only when the full-length clone and not the partial segment of the catalase gene was inserted in the antisense orientation. There was no correlation between the number of genes introduced and the level of inhibition or enhancement of activity. For example, transformant 4.7D (catalase activity, 0.62 times that of WT; Table I) contained at least two NPTII inserts in its genome, but a higher inhibition was obtained in transformed plant 5.13.13 (catalase activity, 0.24 times that of WT), which had only one introduced copy of NPTII (data not shown).

Greatly decreased catalase levels (about 0.30–0.40 times that of the specific activities found in WT) often slowed growth and caused the plants to become yellow in the greenhouse, as was previously observed with a barley mutant with catalase activity 0.05 times that of WT (Kendall et al., 1983) and in transgenic tobacco with an antisense catalase construct (Chamnongpol et al., 1996). Transformant plants 5.13.13 and 7.2.3 (Table I) were examples of plants that yellowed and grew poorly in the greenhouse. However, when they were transferred to a growth room with lower light and temperature and elevated CO2 to slow photorespiration (continuous 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1; 450 μL CO2 L−1; 27°C), they promptly regained their green color and later developed normal flowers and seed.

Overexpression of the cottonseed catalase gene produced only modest increases in catalase specific activity (about 1.36 times that of WT; Table I), whereas introduction of the tobacco leaf catalase gene with the CaMV 35S promoter yielded increases of about 1.5 times that of WT. The greatest increase in catalase activity (2.0 times that of WT and frequently greater) was obtained in transformants containing the Big Mac promoter, although some transformed plants with this promoter also showed increases about 1.5 times that of WT (Table I).

Transmission of Altered Catalase Phenotype

In most T2 families a high proportion (about 75% or more) of seedlings showed kanamycin-resistant growth (Table II), indicating that single or multiple independent insertions of the transgene occurred. In the T2 generation of antisense transformants containing pBZ1, the specific catalase activity in leaves was usually similar to that of the T1 plants in progeny of plants 4.7D and 2.1E (about 0.61 times that of WT; Table I). In catalase-overexpression progeny obtained by selfing plants 9.8 and 9.11 containing the Big Mac promoter, elevated levels of leaf catalase were obtained close to the range of the parental activity (about 1.75 times that of WT). The proportion of individual plants with altered catalase levels in the T2 generation varied from 8 to 20% of the population in antisense plants to 25 to 32% in transformants with the Big Mac promoter.

Catalase mRNA Levels

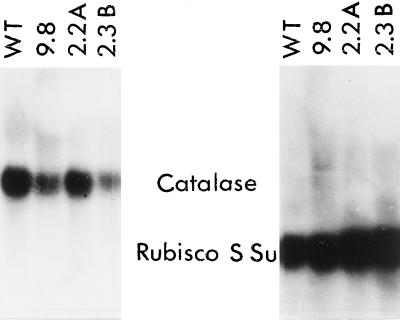

Steady-state levels of catalase and SSu mRNAs were examined by northern-blot analysis on total RNAs isolated from the leaves of mature WT and transgenic plants. Northern-blot analyses were also carried out on young plants (five leaves), mature plants, flowering plants, and plants containing seed pods. The mRNAs were isolated during sunny periods when the catalase activity would be high. Our results revealed that catalase specific activity was not correlated with the steady-state level of transcripts in transgenic plants overexpressing catalase. As an example, Figure 1 shows a comparison of northern-blot hybridizations conducted with WT plant 9.8 (catalase activity 2.04 times that of WT), plant 2.2A (catalase activity 0.62 times that of WT), and plant 2.3B (catalase activity 0.66 times that of WT). When the results are normalized to make the signals for catalase and Ssu in WT the same, the intensity of the catalase mRNA signals relative to the SSu mRNA signals for the transgenic plants were as follows: plant 9.8, 0.18; plant 2.2A, 0.24; and plant 2.3B, 0.069. Thus, steady-state levels of catalase mRNA were not correlated with high catalase activity in transgenic plants overexpressing catalase, as in plant 9.8, and determining catalase specific activities gave a more reliable estimate for physiological experiments.

Figure 1.

Northern-blot analysis of RNA from WT and transgenic plants (9.8, 2.2A, 2.3B; Table I) with altered catalase specific activities. The blots were obtained on Nytran membranes using total RNA (15 μg) from the tip region of leaves that was hybridized to radiolabeled N. tabacum catalase DNA and SSu DNA. Plant 9.8, mean catalase activity, 2.04 times that of WT, plant 2.2A; mean catalase activity, 0.62 times that of WT; and plant 2.3B, mean catalase activity, 0.66 times that of WT. The catalase signals relative to WT were: plant 9.8, 0.3×; plant 2.2A, 0.5×; plant 2.3B, 0.2×. The SSu signals relative to WT were: plant 9.8, 1.7×; plant 2.2A, 2.1×; plant 2.3B, 2.9×.

Catalase Isoform Profiles

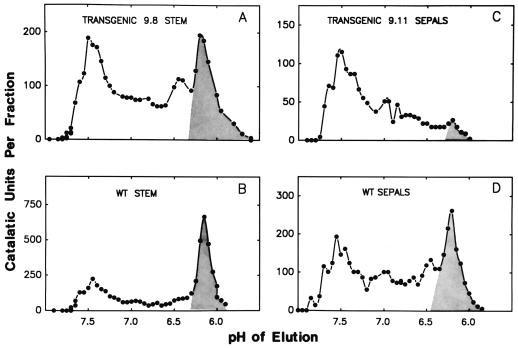

Catalase isoforms that vary in pI can by separated by chromatofocusing and distinguished biochemically by differences in their catalatic and peroxidatic activities and several other properties (Havir and McHale, 1990). On chromatofocusing extracts of tobacco leaves a profile of catalatic activity was obtained, showing a major peak representing about 90% of the total activity (CAT-1), which eluted at about pH 7.5, and the remainder cleanly separated from an isoform with enhanced peroxidatic activity (CAT-3), which eluted at about pH 6.0 (Havir and McHale, 1987). In contrast to leaves, WT stem and sepal tissues contain one major catalase isoform that is similar in properties to CAT-3 in leaves, constituting 0.48 and 0.31 of the catalatic activity in these tissues (Fig. 2, B and D) (Havir et al., 1996). By IEF CAT-1 could be separated into five isoforms (Zelitch et al., 1991) and, recently, a similar resolution was also attained by chromatofocusing (Havir et al., 1996). Transformant leaves that overexpress and underexpress catalase activity (Table I) generally showed catalase isoform profiles similar to those of WT, because the distribution among the isoforms was not altered.

Figure 2.

Elution profile showing separation by chromatofocusing of catalase isozymes in stems and sepals of WT and transgenic tobacco in which catalase activity was overexpressed in leaves. The fractions encompassing the catalase isoform with enhanced peroxidatic activity are shown in the shaded areas. Recoveries of catalase activities of 79 to 90% were obtained from the chromatofocusing columns. A, An extract of stem tissue (18 g) of transformant plant 9.8 (Table I) with a leaf catalase specific activity 2.51 times that of WT yielded 3830 units of catalase activity and 30.5 mg of protein for chromatofocusing. B, An extract of WT stem tissue (31 g) yielded 6560 units of catalase activity and 44.8 mg of protein for chromatofocusing. C, An extract of sepal tissue (4.1 g) of transformant plant 9.11 (Table I) with a leaf catalase specific activity 2.50 times that of WT yielded 1800 units of catalase activity and 10.2 mg of protein for chromatofocusing. D, An extract of WT sepal tissue (5.0 g) yielded 4060 units of catalase activity and 16.5 mg of protein for chromatofocusing.

There were some striking differences, however, in the distribution of catalase isoforms in extracts of stem and sepal tissue between transformants with about 2.5-fold greater leaf catalase specific activity compared with WT plants (Fig. 2). In WT stem tissue CAT-3 was a major isoform (Fig. 2B), but in transgenic overexpressor plant 9.8 the forms with high-catalatic activity (CAT-1) were increased at least 3-fold (Fig. 2A) relative to CAT-3. CAT-3 was also a major isoform in WT sepals (Fig. 2D), but in transgenic overexpressor plant 9.11 the predominantly high-catalatic forms were greatly enhanced compared with CAT-3 (Fig. 2C). Thus, our cloned N. tabacum leaf cDNA (Schultes et al., 1994) was clearly shown to encode CAT-1-type activity.

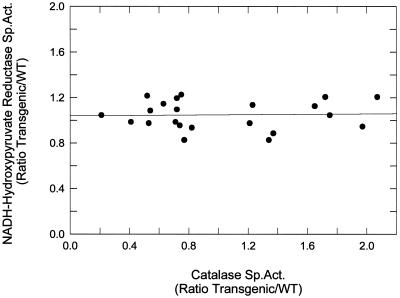

NADH-Hydroxypyruvate Reductase Activities in Transgenic Plants with Altered Catalase Activities

Because NADH-hydroxypyruvate reductase is a peroxisomal enzyme, as is catalase, its activities were compared with those of catalase in transgenic plants over a range of catalase activities from 0.2 to 2.0 times that of WT (Fig. 3). Over this 10-fold change in catalase activity the slope of the line showing the relative change in NADH-hydroxy- pyruvate reductase activity was not significant, attesting to the specificity of the catalase transformations.

Figure 3.

Comparison of NADH-hydroxypyruvate reductase and catalase specific activities in transgenic plants in the T2 generation with decreased and increased catalase specific activities relative to WT. The ratio of transgenic-to-WT activities of NADH-hydroxypyruvate reductase and catalase were determined on the same leaf extracts. The solid line is a least-squares fit with a slope of 0.009 and r2 = 0.001 (P = 0.97) over a range of catalase activities that varied from 0.2 to 2.0 times that of WT.

The CO2 Compensation Point

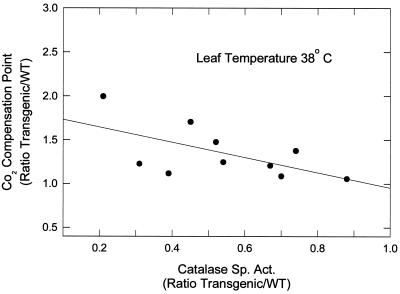

The well-known increase in Γ with increasing temperatures is caused mainly by an elevated photorespiration relative to net CO2 assimilation (Zelitch, 1992a). To examine the role of catalase in the production of photorespiratory CO2, Γ values were determined at a leaf temperature of 38°C in transgenic plants with decreased catalase (Fig. 4). WT leaves had a mean Γ of 133 μL CO2 L−1. The ratio of Γ in transgenic relative to WT plants increased linearly in a significant manner with decreasing catalase activity (r2 = 0.36). Although the data led to a satisfactory linear fit, the possibility remains that the relationship may be curvilinear. When leaf catalase activity was 50% of WT, the mean Γ was 39% higher than that of WT.

Figure 4.

The effect of antisense catalase constructs in the T2 generation on Γ at a leaf temperature of 38°C. The results are expressed as a ratio of transgenic-to-WT activities. Transgenic leaves were from the progeny of three different self-pollinated transformants containing the pBZ1 construct (Tables I and II). The mean Γ for WT (± se) was 133 ± 6.3 μL CO2 L−1 (n = 6). Each point represents experiments done on different leaves on different days. The solid line is a least-squares fit with a slope of −0.87 ± 0.41 and r2 = 0.36 (P < 0.05).

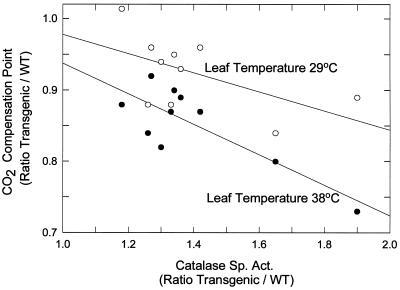

Photorespiration increases greatly relative to net photosynthesis with increasing temperature (Hanson and Peterson, 1985, 1986; Zelitch, 1992a). WT leaves had a mean Γ of 132 μL CO2 L−1 at leaf temperatures of 38°C, and 74 μL CO2 L−1 at 29°C (Fig. 5). Elevated catalase levels decreased the ratio of Γ in transgenic relative to WT plants at 38°C and the data gave a linear fit that was highly significant (r2 = 0.67). The effect at 29°C was smaller, and the slope of the line was not significant. When leaf catalase was 50% greater than that of WT, the mean Γ was 17% lower than that of WT at 38°C, and about 9% lower than that of WT at 29°C.

Figure 5.

The effect of enhanced catalase activity in transgenic plants of the T2 generation on Γ at leaf temperatures of 38°C (•) and 29°C (○). The results are expressed as a ratio of transgenic-to-WT activities. Transgenic leaves were used from progeny of two different self-pollinated transformants containing the pBZ8 construct (Tables I and II). The mean Γ for WT (± se) at 38°C was 132 ± 4.7 μL CO2 L−1 (n = 10), and at 29°C was 74 ± 1.6 μL CO2 L−1 (n = 10). For each experiment the points at leaf temperatures of 38 and 29°C represent results with transgenic leaf samples taken at the same time from the same leaf and compared with WT samples also taken at the same time. The solid lines are least-square fits with slopes of −0.21 ± 0.053 and −0.13 ± 0.071 for 38 and 29°C, respectively. The r2 = 0.67 (P < 0.01) at 38°C, and r2 = 0.32 (P > 0.10) at 29°C.

Changes in Γ can be caused by changes in photorespiration as well as “dark respiration.” The rates of dark respiration in transgenic and WT leaves were therefore measured at leaf temperatures of 36°C after completing Γ determinations at 38°C (Fig. 5). The rates of dark respiration were the same in transgenic and WT leaves, with a mean ratio of transgenic-to-WT plants (± se) of 1.04 ± 0.057 (n = 8). The mean increase in CO2 concentration (μL L−1) in the syringes with WT discs (± se) was 378 ± 4.9 after 10 min, and 759 ± 17 after 20 min. The increase in CO2 concentration was linear and extrapolated to 0 at 0 time, consistent with a lack of effect of CO2 concentration on the rate of dark respiration. Dark respiration undoubtedly occurs in the light, although it is uncertain that its magnitude is exactly the same as in darkness, but the results indicate that the changes in the values for Γ shown in Figures 4 and 5 in transgenic relative to WT leaves did not result from differences in rates of dark respiration between transgenic and WT leaves.

DISCUSSION

Elevated and Reduced Catalase Activities in Transformants with Different Constructs

The present investigation has yielded a number of different transformants that encompass a range of leaf catalase specific activities from about 0.20 to more than 2.0 times that of WT (Table I). Several tobacco mutants with altered catalase activity have previously been described. Transgenic tobacco with 0.05 to 0.15 times the catalase activity of WT has recently been reported (Chamnongpol et al., 1996), and it was shown that under high photorespiratory conditions necrotic lesions were produced in leaves. Overexpression of catalase was obtained in a mutant (Zelitch, 1989) by screening haploid N. tabacum plantlets for superior growth under high photorespiratory conditions (42% O2 and 160 μL−1 CO2). Fertile, diploid progeny of this mutant had catalase activities about 1.4 times that of WT, produced more catalase protein, and had 3-fold greater mRNA transcripts in field-grown plants (Zelitch et al., 1991). Mutant leaves showed about 15% higher rates of net photosynthesis at 30°C, 21% O2, and 300 μL CO2 L−1 (Zelitch, 1990b, 1992b).

Increases in catalase observed with the above mutant could have been a consequence of increased photosynthesis rather than its cause, and uncertainty remained regarding whether altered catalase was fully responsible for altered photosynthesis. Therefore, we decided on a more specific transgenic approach to changing catalase levels that would specifically alter catalase levels (see Fig. 3) and especially CAT-1 (Fig. 2).

When the CaMV 35S promoter was used in constructs with cottonseed catalase DNA in the sense orientation, transformant tobacco plants showed increases in leaf catalase activity to about 1.36 times that of WT (Table I). Insertions with the full-length N. tabacum cDNA enhanced leaf catalase activity of transformants to about 1.5 times that of WT, an enhancement similar to that obtained previously with a tobacco mutant selected for O2-resistant growth (Zelitch, 1989, 1992a). Among the transformed plants with the pBZ2 construct that was designed to obtain overexpression, there were two plants that showed consistent underexpression of catalase activity by 0.50 times or more (Table I). These plants may represent examples in which the insertion of a transgene produces co-suppression, a phenomenon sometimes encountered in transformants (Flavell, 1994).

Comai et al. (1990) demonstrated that the plasmid vector containing the Big Mac promoter could often drive the expression of the GUS gene in tomato and tobacco about 10 times higher than the CaMV 35S promoter alone. Use of the Big Mac promoter in a construct containing the N. tabacum catalase cDNA insert produced some transformants with increases of about 1.5 times that of WT, and others with an enhancement of leaf catalase specific activity that was 2.0 or more times that of WT (Table I). The variation in overexpression of catalase activity with Big Mac is consistent with the finding of Comai et al. (1990) that T1 plants transformed with this promoter produced plants with a broad range of expression levels.

All antisense constructs used the CaMV 35S promoter (Table I). The partial N. sylvestris cDNA insert produced transformants with a mean catalase underexpression of 0.63 times that of WT, and transformed plants containing the full-length N. tabacum DNA averaged 0.46 times that of WT catalase activity. Antisense cotton transformants averaged 0.43 times that of normal catalase activity, although plant 5.13.13 had 0.24 times the activity of WT. Two transgenic plants from a sense construct also showed strongly underexpressed catalase activities, presumably because of co-suppression (Table I), and in the T2 generation of plant 10.33 selfed, a small proportion of the progeny had decreased catalase activity (Table II).

Characteristics of Some T2 Plants Obtained by Selfing Transgenic Plants with Altered Catalase Activity

In general, the altered catalase activities in the T2 generation were similar to those of the parental transformed plants from which they were derived (Tables I and II). Although a high proportion (approximately 75%) of seedling progeny in most families showed kanamycin-resistant growth, indicating that the transgene was usually present as a single copy (Table II), a much lower fraction, 8 to 20%, of unselected populations containing antisense constructs had reduced leaf catalase activity. In the progeny of overexpression transformant plants 9.8 and 9.11, 32 and 25% of randomly selected progeny, respectively, had elevated catalase activity. A similar range of non-Mendelian segregation, 8 to 50%, has previously been observed in the T2 generation in families of tobacco and Arabidopsis carrying transgenes (Kilby et al., 1992), and these workers demonstrated that transgene inactivation could be associated with methylation of an SStII site in the nos promoter of the kanamycin-resistance gene, and other mechanisms may also be involved (Matzke and Matzke, 1995).

Because not every kanamycin-resistant plant can be depended on to over- or underexpresses catalase activity, at the present time the most rapid and reliable method of detecting plants with altered catalase expression is to conduct leaf-catalase assays. Our screening assays were carried out on different leaves of each plant at intervals of at least 1 week.

Relation of mRNA Transcripts to Catalase Activity in Transformants

In our previous work with a tobacco mutant with catalase activity 1.4 times that of WT, 3-fold-higher levels of mRNA were observed in the mutant than in WT in field-grown plants (Zelitch et al., 1991). During maize seedling development the distribution of catalase activity and isozyme protein were usually correlated with the steady-state level of mRNAs (Redinbaugh et al., 1990), but exceptions were noted. For example, Redinbaugh et al. (1990) discuss experiments conducted during maize seedling development in which a catalase mRNA was present in one instance, although the catalase protein was not detected, and they cite another example in which the transcript level remained high when the isozyme protein was decreasing. Also, in a careful developmental study of cotton seedlings, the steady-state level of mRNAs for two different catalase subunits did not reflect the catalase activity or catalase protein levels (Ni and Trelease, 1991), and it was concluded that accumulation of the subunits was primarily controlled at the posttranscriptional level.

A large number of northern-blot hybridizations were conducted with the catalase probe on transgenic plants that underexpress and overexpress catalase specific activity compared with WT, and no correlation was usually observed between the strength of RNA transcripts and catalase specific activities in transformants that overexpress catalase (Fig. 1). It is clear that the steady-state level of mRNA is not always related to mRNA turnover, and other posttranscriptional factors including light intensity (Zelitch, 1992b) and temperature may also contribute to a lack of correlation between catalase activity and transcript level.

Nature of the Catalase Isoform Overexpressed in Transgenic Plants

The full-length N. tabacum catalase cDNA (Schultes et al., 1994) was obtained from a leaf cDNA library, making it likely that the primary leaf catalase was selected. Sequencing of this DNA revealed a protein molecular weight closer to that of CAT-1 than to that of CAT-3 compared with values obtained by SDS-PAGE (Havir and McHale, 1990). The calculated pI of our clone was also closer to that of CAT-1 than to that of CAT-3; hence, our clone must encode CAT-1 or a catalase with similar characteristics. The predicted amino acid sequence of our clone is about 84% homologous with that of Cat1 of Willekens et al. (1994) obtained from N. plumbaginifolia and about 98% homologous with that of their Cat2, which on the basis of RNA hybridizations were located in leaf palisade cells and leaf vascular tissues, respectively.

Results in Figure 2, A and C, show that transformed plants greatly overexpressing catalase in N. tabacum leaves also have large activity increases in stem and sepal tissue associated with CAT-1 (eluting from the chromatofocusing column at about pH 7.5) and CAT-1-like forms (eluting between pH 7.2 and 6.4) compared with CAT-3. Thus, all of these forms with a similar biochemical activity were enhanced by constructs that overexpress our leaf catalase cDNA. Understanding of the relation of these CAT-1 and CAT-1-like forms to the clones obtained from N. plumbaginifolia (Willekens et al., 1994) must await further comparative biochemical and protein-binding studies.

Because NADH-hydroxypyruvate reductase, like catalase, is present in leaf peroxisomes, both activities were assayed in the same extracts to determine whether transgenic alteration of catalase also affected another peroxisomal enzyme (Fig. 3). A 10-fold change in catalase activity produced no significant change in NADH-hydroxypyruvate reductase activity, providing further evidence for the specificity of the cloned CAT-1.

Effect of Altered Catalase Activity on Photorespiratory CO2 Formation and the Role of Leaf Temperature

Leaf temperatures measured outdoors in sunlight are often 3 to 10°C higher than air temperatures at normal windspeed, leaf surface dimensions, and stomatal numbers and apertures (Gates, 1980); hence, leaf temperatures of 38°C are often encountered by plants in greenhouses and outdoors. The hypothesis that catalase plays a role in regulating the release of photorespiratory CO2 under conditions of high photorespiration relative to net photosynthesis has been discussed previously, and this view was supported by experiments with a tobacco mutant with elevated catalase levels (Zelitch, 1992a, 1992b).

For WT tobacco leaves at a leaf temperature of 38°C the mean Γ (± se) was 133 ± 5.3 μL CO2 L−1 (Fig. 4) and 132 ± 4.7 μL CO2 L−1 (Fig. 5). At 29°C, Γ was 74 ± 1.6 μL CO2 L−1 (Fig. 5). These values for Γ are well within the range of published values (Tichá and Catský, 1981). Figure 4 summarizes experiments conducted to examine the role of catalase on photorespiration by measuring Γ at a leaf temperature of 38°C using transformed plants with reduced levels of leaf catalase. The finding of a significant linear relation between reduced catalase and increased Γ relative to WT (with 50% lower catalase Γ increased by 39%) demonstrates that unless H2O2 is rapidly broken down, photorespiratory CO2 will be enhanced at higher temperatures.

In transgenic plants exhibiting catalase overexpression (Fig. 5) at a leaf temperature of 38°C, there was a highly significant linear decrease in Γ relative to WT with increasing catalase (at 50% higher catalase Γ decreased 17%), showing that WT catalase levels are insufficient to remove all of the H2O2 produced under high photorespiratory conditions. At leaf temperatures of 29°C (Fig. 5), the effect of enhanced catalase on decreasing Γ was too small to attain statistical significance, presumably because the changes were smaller and the sum of the plant-to-plant variability and measurement errors became relatively larger. However, reduced catalase levels increased photorespiration and elevated catalase levels decreased photorespiration at higher temperatures, with the relative effect being greater with reduced catalase levels.

Relation of Altered Photorespiratory CO2 Formation by Catalase Levels and the Stoichiometry of CO2 Produced per Glycolate Oxidized

At higher temperatures the ratio of photorespiration to net photosynthesis increases greatly and, accordingly, the rate of glycolate synthesis and H2O2 formation would be elevated. It seems likely that H2O2 not decomposed by catalase activity would rapidly react with α-ketoacids and other compounds (Zelitch, 1992a). In transformants with decreased or increased catalase it is highly unlikely that the CO2/O2 specificity of Rubisco would be altered from WT by our transformations. Therefore, we tested the postulated role of catalase levels on regulating the chemical peroxidation of ketoacids. This may affect the production of photorespiratory CO2 in excess of the minimum stoichiometry (25% per mol of glycolate oxidized released as CO2) of the photorespiratory cycle (Zelitch, 1992a). The significant increase in Γ by 39% shown here when catalase was reduced by 50% relative to WT at a leaf temperature of 38°C (Fig. 4) provides strong evidence that the stoichiometry of photorespiration was increased as catalase activity decreased. The magnitude of the observed 39% increase in Γ would be equivalent to a 38% decrease in the CO2/O2 specificity factor for Rubisco (Jordan and Ogren, 1983) under conditions in which the stoichiometry remained fixed.

Similarly, the highly significant effect of increasing elevated catalase levels on decreasing Γ at a leaf temperature of 38°C (Fig. 5) was demonstrated. It would be expected that Γ would increase at 38°C because of the temperature dependence of the CO2/O2 specificity of Rubisco. But when transformant leaves had a 50% increase in catalase activity, Γ was decreased by 17%, suggesting that a portion of the increase in Γ in WT at higher temperature was caused by peroxidation. Again, if the stoichiometry did not change in these experiments it would require a 20% increase in the CO2/O2 specificity factor for Rubisco (Jordan and Ogren, 1983). Changes of such a magnitude in the specificity factor are highly unlikely.

Dark respiration was not changed in transformants, although it is uncertain whether the magnitude of dark respiration is exactly the same in light as in darkness. In any event, respiratory CO2 must be a small fraction of the total CO2 production in Γ compared with the contribution of photorespiratory CO2, or one would not observe the well-known large effect of O2 concentration on Γ. We are left with the inescapable conclusion that catalase levels can strongly affect photorespiratory CO2 formation by regulating the stoichiometry of the photorespiratory pathway at higher temperatures.

Thus, models that assume a fixed specificity factor and a fixed stoichiometry at a given temperature (Jordan and Ogren, 1983) may be correct for plants grown and tested at 25°C. However, models (Hanson and Peterson, 1985, 1986) that support a fixed specificity factor and a changing stoichiometry under conditions of high photorespiration are consistent with the experimental results presented here. Our experiments suggest a novel method of regulating photorespiration by maintaining the stoichiometry of CO2 formation closer to the expected 25% per mol of glycolate oxidized, and thereby increasing the efficiency of photosynthetic net CO2 assimilation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the generous counsel, vectors, and plasmids (including pACL1352L and pACL1352S) given to us by Alice Cheung (Yale University). Plasmid pC9 was a gift from Richard N. Trelease (Arizona State University); pYU179 was a gift from Stephen L. Dellaporta (Yale University); and pCGN7366 containing the Big Mac promoter was a gift from J.C. Williams (Calgene, Davis, CA). We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Carol Clark, Regan Huntley, and Emelyn Solivan, and helpful discussions with colleagues Francine M. Carland, Neil P. Schultes, and Richard B. Peterson (who also conducted video image densitometry on northern blots).

Abbreviations:

- CaMV

cauliflower mosaic virus

- CAT-1

the high catalytic form of catalase

- Γ

CO2 compensation point

- NPTII

gene encoding neomycin phosphotransferase

- SSu

gene encoding Rubisco small subunit

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Office, grant no. 9201544 to I.Z.

LITERATURE CITED

- Chamnongpol S, Willekens H, Langebartels C, Van Montagu M, Inze D, Van Camp W. Transgenic tobacco with a reduced catalase activity develops necrotic lesions and induces pathogenesis-related expression under high light. Plant J. 1996;10:491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Green D, Westhoff C, Spreitzer RJ. Nuclear mutation restores the reduced CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in a temperature-conditional chloroplast mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;283:60–67. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L, Moran P, Maslyar D. Novel and useful properties of a chimeric plant promoter combining CaMV 35S and MAS elements. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15:373–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00019155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell RB. Inactivation of gene expression in plants as a consequence of specific sequence duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3490–3496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates DM (1980) Biophysical Ecology. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 38–46

- Grodzinski B, Butt VS. The effect of temperature on glycollate decarboxylation in leaf peroxisomes. Planta. 1977;133:261–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00380687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KR, Peterson RB. The stoichiometry of photorespiration during C3-photosynthesis is not fixed: evidence from combined physical and stereochemical methods. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;237:300–313. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KR, Peterson RB. Regulation of photorespiration in leaves: evidence that the fraction of ribulose bisphosphate oxygenated is conserved and stoichiometry fluctuates. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;246:332–346. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havir EA, Brisson LF, Zelitch I. Distribution of catalase isoforms in Nicotiana tabacum. Phytochemistry. 1996;41:699–702. [Google Scholar]

- Havir EA, McHale NA. Biochemical and developmental characterization of multiple forms of catalase in tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:450–455. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.2.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havir EA, McHale NA. Purification and characterization of an isozyme of catalase with enhanced-peroxidatic activity from leaves of Nicotiana sylvestris. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;283:491–495. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90672-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch RB, Fry JT, Hoffmann NI, Eicholtz D, Rogers SG, Fraley RT. A simple and general method for transforming genes into plants. Science. 1985;227:1229–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan DB, Ogren WL. Species variation in kinetic properties of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;227:425–433. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall AC, Keys AJ, Turner JC, Lea PJ, Mifflin BJ. The isolation and characterization of a catalase-deficient mutant of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Planta. 1983;159:505–511. doi: 10.1007/BF00409139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilby NJ, Leyser HMO, Furner IJ. Promoter methylation and progressive transgene inactivation in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:103–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00029153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea PJ, Blackwell RD. Genetic regulation of the photorespiratory pathway. In: Zelitch I, editor. Perspectives in Biochemical and Genetic Regulation of Photosynthesis. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1990. pp. 301–318. [Google Scholar]

- Matzke MA, Matzke AJM. How and why do plants inactivate homologous (trans)genes? Plant Physiol. 1995;107:679–685. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.3.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdy MC, Lamb CJ. Chalcone isomerase cDNA cloning and mRNA induction by fungal elicitor, wounding, and infection. EMBO J. 1987;6:1527–1533. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Trelease RN. Post-transcriptional regulation of catalase isozyme expression in cotton seeds. Plant Cell. 1991;3:737–744. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.7.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Turley RB, Trelease RN. Characterization of a cDNA encoding cottonseed catalase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1049:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogren WL. Photorespiration: pathways, regulation, and modification. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1984;35:415–442. [Google Scholar]

- Redinbaugh M, Sabre M, Scandalios JG. The distribution of catalase activity, isozyme protein, and transcript in the tissues of the developing maize seedling. Plant Physiol. 1990;92:375–380. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodermel SR, Abbott MS, Bogorad L. Nuclear-organelle interactions: nuclear antisense gene inhibits ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase enzyme levels in transformed tobacco plants. Cell. 1988;55:673–681. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schultes NP, Brutnell TP, Allen A, Dellaporta SL, Nelson T, Chen J. Leaf permease1 gene of maize is required for chloroplast development. Plant Cell. 1996;8:463–475. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.3.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultes NP, Zelitch I, McGonigle B, Nelson T. The primary leaf catalase gene from Nicotiana tabacum and Nicotiana sylvestris. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:399–400. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.1.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville CR, Ogren WL. A phosphoglycolate phosphatase deficient mutant of Arabidopsis. Nature. 1979;280:833–836. [Google Scholar]

- Tai TH, Tanksley SD. A rapid inexpensive method for isolation of total DNA from dehydrated plant tissue. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1990;8:297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Tichá I, Catský J. Photosynthetic characteristics during ontogenesis of leaves. 5. Carbon dioxide compensation concentration. Photosynthetica. 1981;15:401–428. [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert NE (1980) Photorespiration. In DD Davies, ed, The Biochemistry of Plants, Vol 2. Academic Press, New York, pp 487–523

- Willekens H, Langebartels C, Tiré C, Van Montagu M, Inzé D, Van Camp W. Differential expression of catalase genes in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia (L.) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10450–10454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I. Selection and characterization of tobacco plants with novel O2-resistant photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:1457–1464. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.4.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I. Further studies on O2-resistant photosynthesis and photorespiration in a tobacco mutant with enhanced catalase activity. Plant Physiol. 1990a;92:352–357. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.2.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I. Physiological investigations of a tobacco mutant with O2-resistant photosynthesis and enhanced catalase activity. Plant Physiol. 1990b;93:1521–1524. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.4.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I. Control of plant productivity by regulation of photorespiration. BioScience. 1992a;42:510–516. [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I. Factors affecting expression of enhanced catalase activity in a tobacco mutant with O2-resistant photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1992b;98:1330–1335. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.4.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I, Havir EA, McGonigle B, McHale NA, Nelson T. Leaf catalase mRNA and catalase-protein levels in a high-catalase tobacco mutant with O2-resistant photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1592–1595. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.4.1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]