Abstract

As part of our National Cancer Institute–sponsored partnership between New Mexico State University and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, we implemented the Cancer Research Internship for Undergraduate Students to expand the pipeline of underrepresented students who can conduct cancer-related research. A total of 21 students participated in the program from 2008 to 2011. Students were generally of senior standing (47%), female (90%), and Hispanic (85%). We present a logic model to describe the short-term, medium-term, and long-term outputs of the program. Comparisons of pre- and post-internship surveys showed significant improvements in short-term outputs including interest (p<0.001) and motivation (p<0.001) to attend graduate school, as well as preparedness to conduct research (p=0.01) and write a personal statement (p=0.04). Thirteen students were successfully tracked, and of the 9 who had earned a bachelor’s degree, 6 were admitted into a graduate program (67%), and 4 of these programs were in the biomedical sciences.

Keywords: undergraduate training program, internship, minority students

Introduction

A significant challenge to effective research into cancer health disparities is the underrepresentation of diverse individuals in both academic and professional biomedical career fields. 1,2 National data for degrees awarded in 2006 show that of the 72,938 bachelor degrees conferred in biological science, 46,472 (63.7%) were earned by White Non-Hispanics, while only 5,074 (7%) were earned by Hispanics and 479 (0.7%) by American Indians/Alaska Natives.1 First-generation students and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds are also underrepresented in biological and biomedical programs at colleges and universities. 1 A similar pattern is observed in rates of masters’ and doctoral degrees awarded in biological science, with Hispanics and American Indian/Alaska Natives earning 4.3% and 0.5% of masters’ degrees, respectively, and 3.4% and 0.1% of doctoral degrees, respectively.

Society benefits in a number of ways when well-trained diverse individuals choose to enter the biomedical fields. While the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects total employment in occupations classified as science and engineering to increase at nearly double the overall rate for all occupations over the next five years, 3 the completion rates for undergraduate degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) are projected to fall further behind completion rates by students in other developed nations. 3,3,4 Diverse U.S. students thus represent untapped potential for this labor gap. 2 Moreover, it is widely believed that underrepresented professionals offer unique skills and motivations to serve diverse and underserved communities and to address health disparities through research or clinical practice. 5–7 Such professionals can help expand the pipeline of researchers and clinical practitioners by serving as important role models and mentors for underrepresented students in biomedical disciplines. 1,2 Underrepresented students are thought to need academic assistance because the secondary schools they attend often lack the resources to ensure high-level teaching and learning, the students are often the first in their families to attend college, and the STEM disciplines are particularly demanding. 8

Undergraduate internship programs may be an important step toward greater representation by diverse individuals in biomedical sciences. Such programs are thought to increase interest in careers in science, increase retention of undergraduate science majors, and motivate students to attend graduate and professional school. 8–14 Increasingly, participation in an internship program is considered a necessary step toward graduate school admission.

As part of our National Cancer Institute (NCI)–sponsored U54 partnership between New Mexico State University (NMSU) and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC), we report on a comprehensive summer training program that aimed to expand the cancer research pipeline by increasing the number of well-trained diverse students who enroll in graduate and professional programs in biomedical sciences. We report pre/post survey data and longitudinal follow-up data from four cohorts of students who participated in the program’s internship component. We hypothesize that post-internship levels of preparedness and motivations to attend graduate (and/or professional) school will be higher than pre-internship levels. We present a logic model, describing program inputs and outputs that may aid program planners in implementing similar programs at their institutions.

Methods

The Cancer Research Internship for Undergraduate Students is a full project of the U54 Minority-Serving Institution–Comprehensive Cancer Center partnership between NMSU and FHCRC. Our previous report provided data from qualitative interviews with program participants. 15 Several participants had subsequently enrolled in graduate or professional school and cited this program as a key factor in their acceptance.

Participants and Recruitment

For the purposes of this program, “diverse” students are defined as those who are racially or ethnically underrepresented in the biomedical sciences, those who are first-generation college students, and those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged. These groups are prominent at NMSU: data from the fall of 2010 show that of the 13,886 degree-seeking undergraduate students at the main Las Cruces campus, 48% are Hispanic and 3% are American Indian/Alaskan Native. Fifty-nine percent of full-time undergraduate freshmen were determined to have financial need. 16 We used multiple approaches to advertise the program and recruit students at NMSU. The NMSU co-principal investigator, the program administrator, and former interns visited science and public health classes (including Introduction to Cancer 17) to present the program and distribute recruitment materials and program applications. We also placed electronic announcements in the campus’s daily news service, and we hung program posters in science departments and the Student Union.

Program Application and Selection of Students and Mentors

The program application asks students to complete a personal data sheet, provide a personal statement, identify possible FHCRC mentors, and request at least one letter of recommendation. A selection committee comprising the co-principal investigators, post-doctoral fellows, and a program coordinator reviews and ranks the applications and makes preliminary selections. The committee then identifies prospective mentors based on the applicants’ research interests and invites the faculty member to host the intern in their respective group. Mindful of previous research highlighting the importance of diverse role models, 18 we ask diverse faculty and post-doctoral fellows to serve as mentors whenever possible.

Program Description

The nine-week Cancer Research Internship for Undergraduate Students was designed to provide research experience and mentorship for diverse undergraduates at NMSU who are of at least sophomore standing. In addition to providing an opportunity to conduct an independent research project under the guidance of a faculty mentor, the program provides weekly seminars and coffee breaks, professional development workshops, social activities, and a final, competitive poster presentation. The program also sponsors students’ attendance at the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science [SACNAS] national conference or another conference within their chosen research discipline.

Mentored Research Project

The selection committee pairs selected students with a faculty mentor to conduct mentored research in any of FHCRC’s divisions: Basic Sciences, Public Health Sciences, Clinical Research, Human Biology, and Vaccine and Infectious Disease. We ask mentors to provide mentees with a research project that can produce findings that students can present at a national conference.

Weekly Seminars and Coffee Breaks

Weekly seminars expose students to the broad array of ongoing research conducted at FHCRC. The “coffee break” sessions, held intermittently throughout the summer, enable students and faculty to discuss issues related to research, such as ethical considerations and preparations for graduate or medical school.

Professional Development Workshops

Based on data from qualitative interviews,15 program staff members organize a series of professional development workshops to enhance students’ preparation and competitiveness for graduate or professional school. Workshop topics include how to prepare a personal statement and resume, and how to write a scientific abstract and prepare a scientific poster. Program staff recruits graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, and other FHCRC staff to serve as peer-reviewers of students’ personal statements and resumes. This peer-review activity enables students to develop their critical thinking and evaluation skills while honing their ability to give and receive constructive feedback of written materials. Students are also provided feedback on presenting a scientific poster. In addition, program staff members organize a panel of diverse graduate students and postdoctoral fellows who discuss their career choices and the obstacles they encountered applying to or attending graduate school.

Competitive Poster Session

As a capstone experience, all students present a summary of their research findings at a final poster session, which is attended by faculty mentors, graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, and other interested FHCRC faculty and staff. Graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, and other FHCRC staff are recruited to serve as judges to evaluate students’ presentations. Program staff members strongly encourage interns to submit an abstract for presentation at annual meetings such as the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) or the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students (ABRCMS). Our program provides conference registration, membership, and travel support for students whose abstracts are accepted.

Evaluation of Summer Internship Program

We developed a self-administered (the survey is administered via SurveyMonkey™) pre- and post-internship survey to assess changes in motivations and preparedness to attend graduate school. Interest and motivation to attend graduate school were addressed separately. With the questions about preparedness, we aimed to measure academic preparedness to attend graduate/professional school, conduct research, choose a graduate/professional school, take the graduate record examination (GRE)/MCAT, write a personal statement, and ask for letters of recommendation. A post-internship survey included all the same questions, as well as additional questions asking students to rate their opinions of specific aspects of the program, such as mentored research, seminars, workshops, and final poster presentation. The surveys were self-administered and took about 10 minutes to complete. All study procedures and interview documents were reviewed and approved by the FHCRC Institutional Review Board, with reciprocal review and approval by the NMSU Institutional Review Board.

Students who participate in the program are entered into a tracking system that records their employment or academic status, their institution/organization, and their department and year in the program. As part of a longitudinal tracking program, we contact participants annually and ask them to report on their reasons for choosing a particular graduate or professional program, any awards they have received (both merit and funding), presentations they have delivered, and publications they have authored.

Statistical Analysis

Of the 21 students who participated in the program from 2008 to 2011, 2 declined participation in the pre- and post-internship surveys. We report socio-demographic characteristics of the remaining 19 participants. We used McNemar chi-square tests to assess changes in motivations and preparedness for graduate school at pre- and post-internship time points. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant. We report the frequency of students who attended or were attending graduate or professional school and the frequency who held employment positions in the biomedical sciences. This report focuses on summer undergraduate students who participated in 2008–2011. All analyses were performed using STATA 10.0 for Windows (College Station, TX).

Results

Socio-demographic Characteristics

Of the 19 student participants, the majority (85%) were Hispanic and over half (58%) were first-generation college students or were receiving financial aid to attend college (Table 1). Nearly one-half were of senior standing (47%) and most were female (90%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Program Participants, 2008 – 2011

| N = 19 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | N | % |

| Hispanic | 16 | 84.2 |

| Non-Hispanic | 3 | 15.8 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 17 | 89.5 |

| First Generation College Student | ||

| Yes | 11 | 57.9 |

| Financial Aid Recipient | ||

| Yes | 10 | 52.6 |

| Academic class | ||

| Sophomore | 3 | 15.8 |

| Junior | 7 | 36.8 |

| Senior | 9 | 47.4 |

| Aspired Degree | ||

| MA/MS | 3 | 15.8 |

| PhD | 6 | 31.6 |

| MD | 5 | 26.3 |

| MD-PhD | 5 | 26.3 |

| Pre-internship Career Goals a | ||

| Biological research | 5 | 26.3 |

| Public health/behavioral research | 1 | 5.3 |

| Clinical research | 3 | 15.8 |

| Health professional / Licensed clinical work | 2 | 10.5 |

| Practice medicine | 8 | 42.1 |

| Teach | 2 | 10.5 |

| Other | 2 | 10.5 |

participants could choose multiple career goals; sum>100%

Logic Model

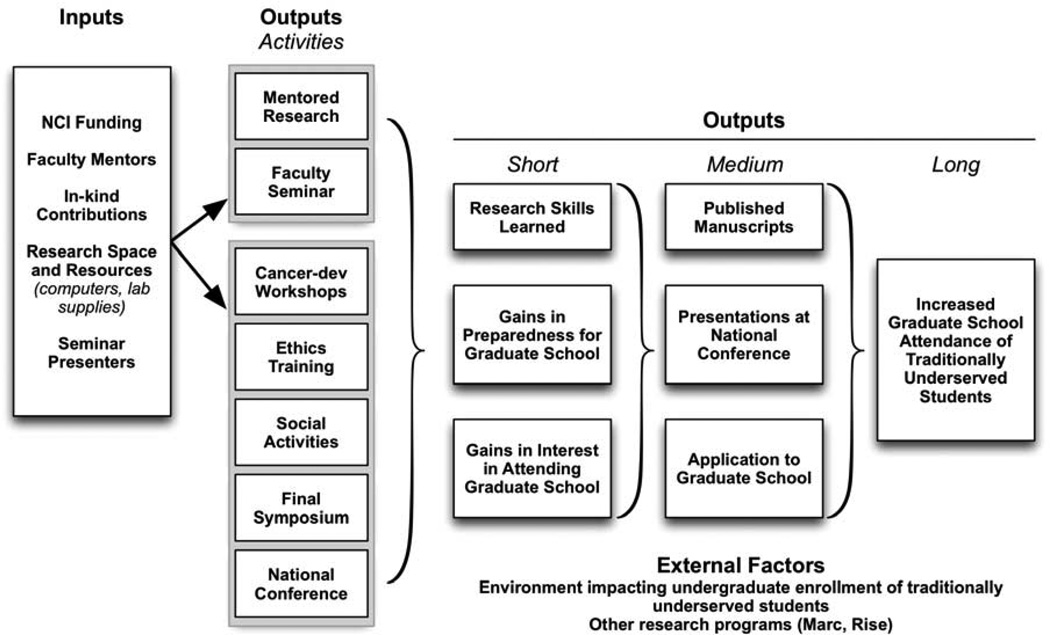

We developed a logic model to characterize the inputs, activities, and outputs relevant to our program (Figure 1). Inputs included funding, faculty mentors, in-kind contributions for social activities, research space and resources (lab supplies and computers), and research seminar presenters. Program activities led to a set of short- and medium-term outputs that included increases in skills learned, motivations and preparedness to attend graduate or professional school (short-term), and authorship of research publications and presentations at national conferences (medium-term).

Figure 1.

Logic Model

Short-term Outputs

When we compared baseline and post-program survey responses (Table 2), we found a moderate but non-significant increase in aspirations to attend a doctoral-level graduate or medical degree program (84% vs. 95%). We observed significant increases in a variety of measures of motivation and academic preparedness for graduate school. Specifically, our comparison of baseline and post-program responses showed that students reported being more interested (95% vs. 100%), more motivated (90% vs. 100%), more prepared to conduct research (47% vs. 90%), and more prepared to write a personal statement for graduate or professional school admissions (56% vs. 83%). Non-significant changes were observed in students’ perceptions of their academic preparedness to attend graduate or professional school in general, take the GRE/MCAT, ask for letters of recommendation, and choose a graduate or professional school.

Table 2.

Pre- and post-internship changes in aspiration, interest, motivation, and preparedness to attend graduate school

| Pre-test N = 19 |

Post-test N = 19 |

p-value a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspiration, interest, motivation | N | % | N | % | |

| Highest degree hoped to earn (% PhD, MD, or MD/PhD) | 16 | 84.2 | 18 | 94.7 | 0.16 |

| Interested in attending graduate/professional school b | 18 | 94.7 | 19 | 100 | <0.001 |

| Motivated to attend c | 17 | 89.5 | 19 | 100 | <0.001 |

| Preparedness d | |||||

| Academically prepared to attend graduate/professional school | 14 | 73.7 | 16 | 84.2 | 0.16 |

| Prepared to conduct research | 9 | 47.4 | 17 | 89.5 | 0.01 |

| Prepared to choose a graduate/professional school e | 5 | 27.8 | 8 | 44.4 | 0.32 |

| Prepared to take the Graduate Record Exam/MCAT e | 5 | 27.8 | 8 | 44.4 | 0.18 |

| Prepared to write a personal statement e | 10 | 55.6 | 15 | 83.3 | 0.04 |

| Prepared to ask for letters of recommendation e | 12 | 66.7 | 16 | 88.9 | 0.60 |

based on McNemar chi-square test for matched pairs

percent reporting very interested or interested

percent reporting very motivated or motivated

percent reporting very prepared or prepared

n = 18 students

Students’ concerns about choosing the right graduate school were unchanged in our comparison of baseline and post-program responses (Table 3). Following the program, a significantly lower proportion of students had concerns about being academically prepared for graduate or professional school (89% vs. 61%), having enough research experience for graduate or professional school (94% vs. 61%), and getting into their graduate or professional school of choice (94% vs. 88%). Our data showed some easing of students’ concerns about enjoying graduate or professional school, but to a non-significant degree.

Table 3.

Pre- and post-internship concerns of students

| Pre-test N = 19 |

Post-test N = 19 |

p-value a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concerns b | N | % | N | % | |

| Choosing right graduate/professional school c | 16 | 88.9 | 16 | 88.9 | 0.32 |

| Academically prepared for graduate/professional school c | 16 | 88.9 | 11 | 61.1 | 0.008 |

| Enough research experience for graduate/professional school c | 17 | 94.4 | 11 | 61.1 | 0.008 |

| Getting into graduate/professional school of choice d | 16 | 94.1 | 15 | 88.2 | 0.05 |

| Enjoying graduate/professional school d | 14 | 82.4 | 13 | 76.5 | 0.18 |

based on McNemar chi-square test for matched pairs

percent reporting very concerned or concerned

n = 18

n = 17

Medium-term Outputs

Nineteen students submitted abstracts to the national conference of the SACNAS or a similar conference, all of which were accepted and presented. Notably, one student was awarded ‘best poster presentation’ in the Cancer Biology category at the SACNAS conference. Several students also presented their posters at additional research symposia or disciplinary conferences. Though it was not a requirement of the program, five students co-authored scientific manuscripts as a result of their participation in the program.

Long-term outputs

Thirteen students from the 2008–2010 program years were successfully tracked, and of the 9 who had earned a bachelor’s degree, six (67%) were admitted into a graduate program (two PhD programs in biomedical sciences, two masters’ programs in biomedical sciences, and two other masters’ programs) Of the three students who are not in graduate or professional school, two are in post-baccalaureate programs in the biomedical sciences and one is working as a technician in a biomedical research lab.

Discussion

Participation in a summer research program is increasingly considered a necessary step toward successful admission to graduate school. Our Cancer Research Internship for Undergraduate Students endeavored to expand the pipeline of underrepresented students who are trained to conduct cancer-related research. We sought to introduce diverse undergraduate students to careers in cancer research and to provide them with opportunities to build important relationships and research skills.

As short-term outputs, we report increases in student motivations and preparedness to attend graduate or professional school. Specifically, students reported significantly higher interest and motivation to attend graduate or professional school, as well as better preparedness to conduct research and write a personal statement. Moreover, while 84% of students aspired to obtain a PhD, MD, or MD/PhD prior to the internship, 95% aspired to do so at the end. Similarly, Russell et al. showed that among 4,500 students who received funding from the National Science Foundation to participate in an internship program, 70% of interviewed students reported an increased interest in STEM fields and 29% of those who initially had not considered pursuing a doctoral degree expected to do so after participating in the program. 19

All of the students in our program successfully submitted abstracts to present a poster at a national research conference. In addition, five students co-authored published manuscripts using data collected during the internship program. One student was recognized with the “best poster presentation” award at the annual SACNAS meeting. Several previous reports have noted the importance of building skills in the presentation of research findings,8 though relatively few have required students to present at local, regional or national conferences.

Our longitudinal follow-up data from students who would be eligible to apply to graduate or professional school suggests that 67% had enrolled in graduate school and 22% had enrolled in a post-baccalaureate program. While our numbers are too small to draw firm conclusions, we consider these early findings to be a program success and highly promising for future efforts.

Strengths

Our program was supported by a variety of institutional resources, a factor noted in previous reports as key to running an effective internship program. We received significant support from both FHCRC and NMSU, as well as the NCI. Each year, the Public Health Sciences Division at the FHCRC helped fund student participation in the program, and NMSU faculty and staff promoted the program. Program staff continually enhanced the academic rigor of the program so that students were well-prepared for the graduate/medical school application process, as well as the expectations of a graduate or medical school program.

We used qualitative data from participants in the pilot program (NCI U56 grant) to inform improvements to this program. This resulted in the inclusion of a professional workshop focused on writing a personal statement for admission to graduate or professional school, as well as a panel presentation from underrepresented graduate and post-doctoral fellows to address the challenges they’ve encountered in graduate or professional school. This assessment allowed us to further tailor our program to meet students’ needs.

Limitations

There are some important limitations to the evaluation of our program. As we did not select a random sample of students to participate in the program, our evaluation lacked a control group. Moreover, selection bias was introduced in two ways: only a small group of motivated students applied, and our selection committee chose students who were thought to be most likely to benefit from and succeed in the program. As a result of these biases, we are unable to assess the true impact of the program on graduate or professional school admission. While our 67% percent of student participants who attended graduate school is higher than some previous reports, selection bias makes it impossible to assess our program’s specific influence on that figure. Nevertheless, our evaluation of the program’s short-term outputs suggests that even among this select group, we achieved significant improvement in motivation and preparedness to attend graduate or professional school.

Another reason we cannot directly attribute participation in our program to graduate school admission is that students may participate in a variety of on- and off-campus research opportunities. Other components of our program included a new undergraduate-level course in cancer research at NMSU and a year-long post-baccalaureate program at FHCRC, both of which may have further motivated and prepared students to attend graduate or professional school. Tracking data from our program show that two student interns participated in the program during two consecutive summers and that four summer interns later participated in the post-baccalaureate program. Our small sample prohibits comparisons of graduate or professional school attendance across these subgroups.

Our evaluation did not assess pre- and post-internship changes in academic performance in undergraduate school (mid-term outcome), though previous reports have assessed changes in overall GPA and science-course GPA.20 While we do not believe this limits the interpretation of our findings, future programs may benefit from tracking this measure.

Previous reports raise the possibility that programs such as ours provide experiences to students who are already sufficiently motivated to attend graduate school. Rather than expanding the pipeline, our program may instead strengthen the candidacy of students who already plan to attend graduate or professional school. In previous evaluations of summer internship programs, the proportion of students who became motivated to pursue graduate or professional school as a result of the program ranged from 3% to 50%. 10,11 Notably, our training program focused specifically on cancer-related research, potentially influencing students’ educational goals and their future research interests.

Acknowledgments

The program is supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute: 5 U54 CA132381 (FHCRC) and 5 U54 CA132383 (NMSU). The Minority Access to Research Careers (MARC) Program at NMSU also provided financial support for students.

References

- 1.National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Detailed Statistical Tables NSF 11–316. Arlington, VA: 2011. [2-6-2012]. Science and Engineering Degrees: 1996–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson DJ, Brammer CN. A National Analysis of Minorities in Science and Engineering Faculties at Research Universities. [1-4-2010]; [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Science, National Science Board. Science and Engineering Indicators 2008 NSB 08-01. Chapter 3. Arlington, VA: 2008. Figure 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashby C. Washington DC: United States Government Accountability Office; 2006. Higher education science, technology, engineering, and mathematics trends and the role of federal programs. GAO-06-702T. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED491614. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman LA, Pollock RE, Johnson-Thompson MC. Increasing the pool of academically oriented African-American medical and surgical oncologists. Cancer. 2003;97:329–334. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson J, Jayadevappa R, Taylor L, et al. Extending the Pipeline for Minority Physicians: A Comprehensive Program for Minority Faculty Development. Acad Med. 1998;73:237–244. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199803000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smedley BD, Stith Butler A, Bristow LR. In the Nation's Compelling Interest: Ensuring Divesity in the Health Care Workforce. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gafney L. State University of New York Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation: Research on Best Practices. [10-6-2010]; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler PJ, Dong C, Snyder AJ, et al. Bioengineering and Bioinformatics Summer Institutes: meeting modern challenges in undergraduate summer research. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2008;7:45–53. doi: 10.1187/cbe.07-08-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villarejo M, Barlow A. Evolution and Evaluation of a Biology Enrichment Program for Minorities. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering. 2007;13:119–144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopatto D. Undergraduate research experiences support science career decisions and active learning. CBE life sciences education. 2007;6:297–306. doi: 10.1187/cbe.07-06-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopatto D. Survey of Undergraduate Research Experiences (SURE): first findings. Cell Biol Educ. 2004;3:270–277. doi: 10.1187/cbe.04-07-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirsch IS, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. Adult literacy in America: a first look at the findings of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington (D.C.): Tertiary Adult Literacy in America: a first look at the findings of the National Adult Literacy Survey; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frantz KJ, DeHaan RL, Demetrikopoulos MK, et al. Routes to research for novice undergraduate neuroscientists. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2006;5:175–187. doi: 10.1187/cbe.05-09-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coronado GD, O'Connell MA, Anderson J, et al. Undergraduate cancer training program for underrepresented students: findings from a minority institution/cancer center partnership. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25:32–35. doi: 10.1007/s13187-009-0006-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NMSU Institutional Research, Planning and Outcomes Assessment. [11-24-2011];2012 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuster M, Peterson K. Development, implementation, and assessment of a lecture course on cancer for undergraduates. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2009;8:193–202. doi: 10.1187/cbe.09-03-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philips J, Wile M. Academic Outreach: Health Careers Enhancement Program for Minorities. Journal of the National Medical Assocation. 1990;82:841–846. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell SH, Hancock MP, McCullough J. Science. Vol. 316. New York, N Y: 2007. Benefits of Undergraduate Research Experiences; pp. 548–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junge B, Quinones C, Kakietek J, et al. Promoting undergraduate interest, preparedness, and professional pursuit in the sciences: An outcomes evaluation of the SURE program at Emory University. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2010;9:119–132. doi: 10.1187/cbe.09-08-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]