Abstract

Achondroplasia (ACH), the most common form of dwarfism, is an inherited autosomal-dominant chondrodysplasia caused by a gain-of-function mutation in fibroblast-growth-factor-receptor 3 (FGFR3). C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) antagonizes FGFR3 downstream signaling by inhibiting the pathway of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Here, we report the pharmacological activity of a 39 amino acid CNP analog (BMN 111) with an extended plasma half-life due to its resistance to neutral-endopeptidase (NEP) digestion. In ACH human growth-plate chondrocytes, we demonstrated a decrease in the phosphorylation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2, confirming that this CNP analog inhibits fibroblast-growth-factor-mediated MAPK activation. Concomitantly, we analyzed the phenotype of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice and showed the presence of ACH-related clinical features in this mouse model. We found that in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, treatment with this CNP analog led to a significant recovery of bone growth. We observed an increase in the axial and appendicular skeleton lengths, and improvements in dwarfism-related clinical features included flattening of the skull, reduced crossbite, straightening of the tibias and femurs, and correction of the growth-plate defect. Thus, our results provide the proof of concept that BMN 111, a NEP-resistant CNP analog, might benefit individuals with ACH and hypochondroplasia.

Main Text

Gain-of-function mutations in FGFR3 (MIM 134934) lead to achondroplasia (ACH [MIM 100800]), hypochondroplasia (HCH [MIM 146000]), and thanatophoric dysplasia (TD [MIM 187600]).1,2 These conditions, all due to increased signaling of fibroblast-growth-factor-receptor 3 (FGFR3), are characterized by a disproportionate rhizomelic dwarfism and differ in severity, which ranges from mild (HCH) to severe (ACH) and lethal (TD).3 FGFR3 is a key regulator of endochondral bone growth4 and signals through several intracellular pathways, including those of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). FGFR3 constitutive activation impairs proliferation and terminal differentiation of the growth-plate chondrocytes5 and synthesis of the extracellular matrix. FGFR3 activation is associated with increased phosphorylation of the STAT and MAPK pathways. Activation of the STAT pathway was reported in both Fgfr3K644E/+mice6 and human growth-plate chondrocytes harboring various FGFR3 gain-of-function mutations.7,8 The role of the MAPK pathway in mediating FGFR3 activity is illustrated by the dwarfism of mice with constitutive activation of MAPK/extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1 (MEK1)9 and conversely by the overgrowth of long bones and enlarged foramen magnum (FM) of mice with inactivation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2).10 The MAPK signaling pathway is regulated by C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP).11 Binding of CNP to its receptor, natriuretic-peptide receptor B (NPR-B), inhibits FGFR3 downstream signaling at the level of Raf-112 (Figure S1, available online) and thus triggers endochondral growth13 and skeletal overgrowth, as observed in both mice14 and humans15,16 overexpressing CNP. Conversely, loss-of-function mutations in NPR2 (MIM 108962), a gene coding for NPR-B, are responsible for disproportionate dwarfism in mice17 and acromesomelic dysplasia, Maroteaux type (MIM 602875) in humans.18 Overproduction of CNP in the cartilage11 or continuous delivery of CNP through intravenous (IV) infusion19 normalizes the dwarfism of Fgfr3ach/+ mice, suggesting that administration of CNP at supraphysiological levels is a strategy for treating ACH. However, given its short half-life (2 min after IV administration20), CNP as a therapeutic agent is challenging in a pediatric population because it would require continuous IV infusion. Because the subcutaneous (SC) route of administration is preferred over continuous infusion in pediatric individuals, we designed and manufactured BMN 111, a 39 amino acid CNP pharmacological analog (Figures S1 and S2). BMN 111 mimics CNP pharmacological activity and has an extended half-life as a result of neutral-endopeptidase (NEP) resistance that allows once-daily SC administration. BMN 111 behaves similarly to native CNP with regard to signaling through NPR-B, its affinity to natriuretic-peptide receptor C, and its inability to activate natriuretic-peptide receptor A at physiological concentrations (data not shown). In this study, we performed a detailed characterization of the dwarfism-related clinical features of the Fgfr3Y367C/+ mouse model.21 We evaluated the pharmacological activity of this CNP analog by using in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo systems, including human growth-plate chondrocytes harboring the FGFR3 c.1138G>A (p.Gly380Arg) gain-of-function mutation and the Fgfr3Y367C/+ mouse model21 expressing the c.1100A>G (p.Tyr367Cys) mutation corresponding to the c.1118A>G (p.Tyr373Cys) mutation in TD. Experimental animal procedures and protocols were approved by the French Animal Care and Use Committee. Human tissues were obtained with parental consent, and samples were collected and processed in agreement with the guidelines of the French ethical committee.

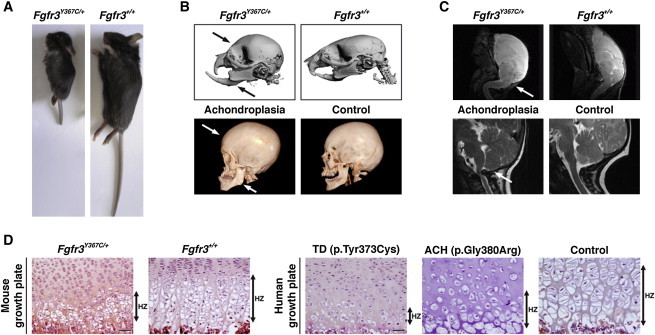

In Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, the mutant allele is expressed at sites and at levels where Fgfr3 is normally expressed. The Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice displayed a relevant dwarfism phenotype (Figure 1A). When compared to their wild-type (WT) littermates, the Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice showed a significant disproportionate dwarfism: ∼50% of the length of the appendicular skeleton (54% for the femur and 42% for the tibia) and ∼70% of the length of the axial skeleton (71% for the lumbar vertebra length L4–L6 and 65% for the nasoanal length) (Table S1). The anterior-posterior diameter of the skull and the sagittal and lateral diameters of the FM were ∼70% of those of the WT mice (Figure 1B and Table S1). The Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice presented a growth deficit affecting both endochondral and membranous ossification and displayed disproportionate short stature, as observed in ACH.22 Computed-tomography scans of the Fgfr3Y367C/+ mouse skull showed the presence of an abnormally domed skull and a small snout with an anterior crossbite; these were comparable to the prominent forehead (frontal bossing) and midface hypoplasia observed in ACH (Figure 1B). Medullary and upper-spinal-cord compression due to a reduced size of the FM was observed by MRI in this mouse model, thereby confirming anomalies in cervical vertebrae (Figure 1C). These signs of cervicomedullary compression due to FM stenosis were similar to those reported in ACH children (Figure 1C). All these features are part of the hallmarks of ACH.3,22 Comparative histological analysis of the distal femoral epiphysis revealed similar defects in size and growth-plate architecture in both Fgfr3Y367C/+ and ACH-affected mice; reduced prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones, a lack of columnar arrangement, and abnormal shape and smaller hypertrophic cells were observed (Figure 1D). The c.1118A>G (p.Tyr373Cys) mutation (RefSeq accession number NM_000142.4) that causes TD in humans triggered in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice a phenotype that appeared closer to ACH than to TD (Figure 1D). All these data allowed us to conclude that this Fgfr3Y367C/+ mouse model appears to properly recapitulate the human ACH phenotype.

Figure 1.

ACH-Related Clinical Features in Fgfr3Y367C/+ Mice

(A) Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice exhibit a severe dwarfism phenotype. Mice presented are littermates and are 17 days old.

(B) Computed-tomography (CT) scans of Fgfr3Y367C/+ (n = 5) and Fgfr3+/+ mice (n = 5) (top) and ACH and control human skulls (15 years of age) (bottom) show a domed skull (arrow) with an anterior crossbite (arrow) in Fgfr3 mutants. CT scans were performed with a VivaCT40 microscanner (SCANCO Medical, Laboratoire de Biologie Intégrative du Tissu Osseux, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale Unité U1059) according to the following protocols: 0.020 mm voxel resolution, 55 kV, sigma 1.5, support 2, threshold 148, and 150 uA.

(C) MRI analysis of Fgfr3Y367C/+ (n = 4) and Fgfr3+/+ mice (n = 4) (3 weeks of age) (top) and ACH and control humans (16 years of age) (bottom) shows medullary and upper-spinal-cord compression (arrow) in a pathological case. After three averages, a repetition time of 1,200 ms (echo time 80 ms), and two dummy scans, the resolution in mice was 0.0078 cm/px × 0.0078 cm/px × 625 micron/px for a matrix size of 256 × 256 × 32. The total scan time was 30 min. In humans, MRI was performed with a 1.5 tesla (Signa General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA) scanner with the following sequences: FSE T2 (TR/TE: 5,000/108, 3 mm slices, 0.3 mm gap). MRI was performed without intravenous contrast enhancement. Osirix software was used for postprocessing.

(D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the growth plate of 2-week-old Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (n = 20) shows a decrease in the height of the hypertrophic (HZ) zone. The area of the Fgfr3Y367C/+ hypertrophic cells is smaller than that of Fgfr3+/+ cells (arrows). H&E analysis of the growth plate from a TD (c.1118A>G [p.Tyr373Cys] mutation) fetus (16 weeks of age), from an ACH (c.1138G>A [p.Gly380Arg] mutation) fetus, and from a control fetus (25 weeks of age) shows a gradient of extremely severe (TD) to moderate (ACH) (arrows) defects in the growth-plate architecture. The size of the hypertrophic cells from the ACH growth plate is smaller than that of the control cells. Comparative analyses of human and mouse growth plates shows that the cartilage of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (n = 30) resembles that of ACH mice (n = 15) more than that of TD mice (n = 25). The scale bars represent 50 μm.

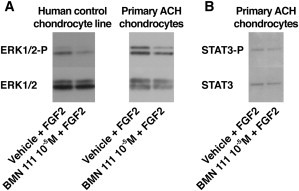

We observed NPR-B localization in the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of human control, ACH, and TD growth plates (data not shown). The pattern of NPR-B localization in human controls was similar to that of WT mice.23 We then evaluated in vitro the effect of the CNP analog, BMN 111, on the ERK1/2 and STAT phosphorylation levels by using various cell lysates prepared from human immortalized control chondrocytes (Figure 2A), primary control chondrocytes (data not shown), and primary ACH chondrocytes harboring the c.1138G>A (p.Gly380Arg) mutation (Figure 2A).24,25 The CNP analog partially inhibited fibroblast-growth-factor (FGF)-mediated ERK1/2 activation in all human cellular systems tested. These data were consistent with the inhibition of the ERK pathway by CNP in rat chondrosarcoma cells.12 Contrariwise, FGF-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation did not appear decreased in ACH chondrocytes (Figure 2B), suggesting that NPR-B might not regulate the STAT pathway in human ACH chondrocytes. Similar observations were noted in ATDC5 cells in which CNP did not affect the phosphorylation of STAT1.26 All these data indicate that FGFR3 and NPR-B signaling pathways crosstalk in human ACH chondrocytes through the regulation of the MAPK signaling pathway. In growth-plate histology sections of Fgfr3Y367C/+ and Fgfr3+/+ mice, we observed FGFR3 and NPR-B localization in the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the cartilage (Figure 3A). A similar distribution pattern was previously observed in WT mice for FGFR327 and NPR-B.23

Figure 2.

BMN 111 Reduced ERK1/2 Activation in ACH Growth-Plate Chondrocytes

(A) Control and pathologic human chondrocytes (ACH) were isolated as described previously24 and treated with BMN 111 (10−5 M) prior to coincubation with fibroblast growth factor (FGF) (100 ng/ml FGF18). BMN 111 pretreatment partially prevented FGF-mediated increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (n = 6). The cell lysates were subjected to SDS polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis and were hybridized overnight at 4°C with phosphorylated-ERK1/2 antibody (1/1,000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) or ERK1/2 antibody (1/1,000) (Cell Signaling Technology). A secondary antibody coupled to peroxidase was used at a dilution of 1:10,000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Bound proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

(B) Immunoblot showing STAT3-P and STAT3 (dilution 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology) in human ACH growth-plate chondrocytes (n = 3). The phosphorylation of STAT3 did not appear decreased upon BMN 111 coincubation.

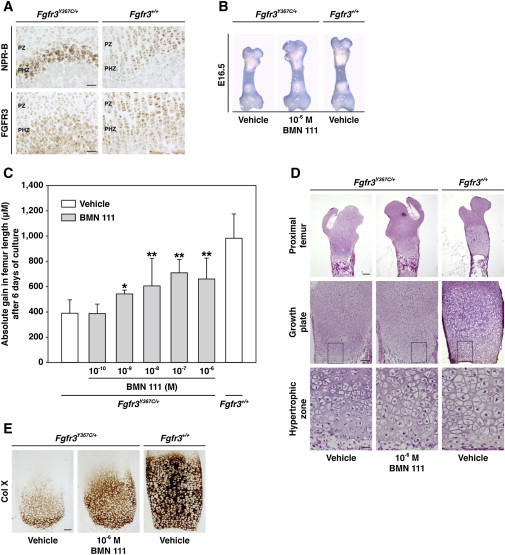

Figure 3.

CNP Analog Improved the Size and Growth-Plate Defect in an Ex Vivo Fgfr3Y367C/+ Mouse Model

(A) FGFR3 and NPR-B localization in the proliferative (PZ) and prehypertrophic (PHZ) zones of the cartilage. Serial histology sections of the growth plate from Fgfr3+/+ and Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (n = 6) were stained by immunochemistry with an FGFR3 antibody (1:250 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and an NPR-B antibody (1:100 dilution; Abcam [ab14357-ICC/IF/WB], Cambridge, UK) and were visualized with the Dako Envision kit with an anti-rabbit antibody (secondary antibody) (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Images were captured with an Olympus PD70-IX2-UCB microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

(B) A partial normalization of the growth defect, as well as enlargement of the epiphysis, was observed in the BMN-111-coincubated femurs (n = 25) isolated from Fgfr3Y367C/+ mouse embryos (E16.5) after 6 days of culture in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with antibiotics and 0.2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with BMN 111 (BMN 111 patent US2010-0297021, BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Novato, CA, USA).

(C) Quantitative gain in femur length after coincubation with BMN 111 (10−6 M to 10−10 M) or vehicle. A partial concentration-dependent restoration of the growth-plate defect was observed in Fgfr3Y367C/+ femurs coincubated with BMN 111 (BMN 111 10−6 M, n = 13; 10−7 M, n = 10; 10−8 M, n = 8; 10−9 M, n = 6; and 10−10 M, n = 6). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.001, Student's t test. Error bars indicate the SD.

(D) H&E staining of longitudinal sections of Fgfr3Y367C/+ (n = 11) and Fgfr3+/+ (n = 16) femurs coincubated with BMN 111 (10−6 M) or vehicle. An increase in the height of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the growth plate, along with the normalization of the shape of the chondrocytes, was observed in BMN-111-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ femurs. The enlarged regions are boxed. The scale bar in the “Proximal femur” row represents 200 μm, the scale bar in the “Growth plate” row represents 100 μm, and the scale bar in the “Hypertrophic zone” row represents 20 μm.

(E) Type-X-collagen (1:30 dilution, Quartett, Berlin, Germany) immunohistochemical staining of the hypertrophic zone of Fgfr3Y367C/+ femurs coincubated with BMN 111 (10−6 M) or vehicle. A partial restoration of the size of the hypertrophic zone was observed in BMN-111-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ femurs (n = 11) compared to vehicle-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ femurs coincubated with vehicle (n = 11). The scale bar represents 100 μm.

The pharmacological activity of BMN 111 was evaluated ex vivo with the use of femur explants isolated from Fgfr3Y367C/+mice. At baseline (embryonic day 16.5 [E16.5]), Fgfr3Y367C/+ femur lengths were slightly shorter than those of the WT littermates (Figure 3B). Coincubation of the left femurs with the CNP analog (10−6 M to 10−10 M) for 6 days led to a significant concentration-dependent increase in femur size, as illustrated by the gain in femur length (Figure 3C and Table S2). Increases in bone length were associated with a concentration-dependent expansion of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones (Figure S3A). The correction of the growth-plate size and architecture was almost complete after coincubation with the 10−6 M CNP analog (Figure 3D). We noted the presence of larger and spherical hypertrophic chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone (Figure 3D). Type X collagen staining, a marker of chondrocyte differentiation, showed a concentration-dependent increase in the size of the hypertrophic zone of the femur explants of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice and confirmed the increased number of differentiated chondrocytes (Figure 3E and Figure S3B). These histological changes support the proof of concept that BMN 111 promotes chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation in growth plates from a mouse model with a FGFR3 gain-of-function mutation. As improvement in the bone-growth defect occurred in the absence of any systemic regulation (ex vivo bone explants), a direct effect on bone growth was observed. These observations are consistent with CNP pharmacological activity in control bone explant cultures from various rodents.28,29

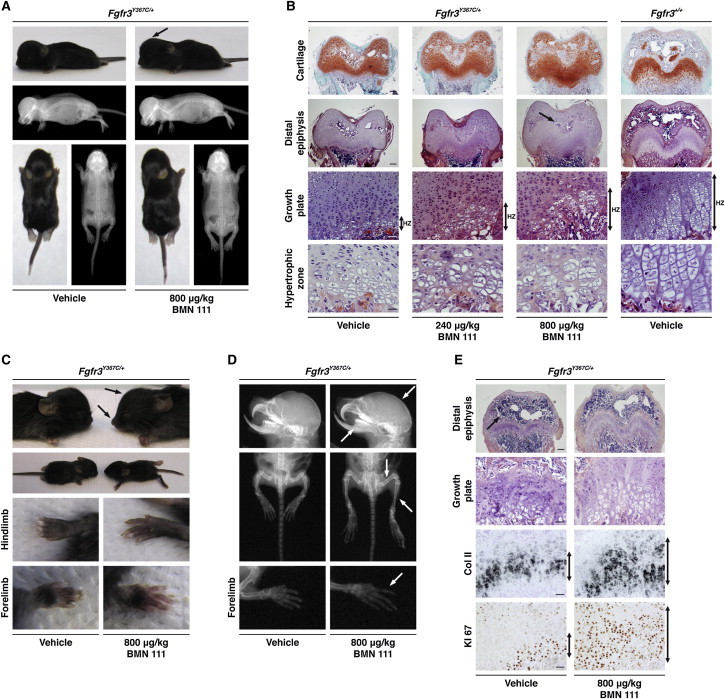

The effectiveness of attenuating the dwarfism phenotype of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice was assessed in vivo. The Fgfr3Y367C/+ and Fgfr3+/+ mice were 7 days old when treatment began and received once-daily SC administrations of BMN 111 for 10 or 20 days. Significant improvement in dwarfism was noted after 10 days of treatment in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice given 240 (not shown) or 800 μg/kg BMN 111 (Figure 4A) and included an increase in body size, a longer tail, and a flattening of the skull. After 10 days of treatment, measurement of various segments (Table 1) in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice given 240 or 800 μg/kg revealed a significant dose-dependent growth of the femur (3.4% or 5.2%, respectively) and nasoanal length (4.5% or 5.3%, respectively) (p < 0.05). Significant growth of the tibia (6.6%), anterior-posterior diameter of the skull (4.8%), and tail (9.8%) (p < 0.05) was observed at the 800 μg/kg dose level. Mean diameters (sagittal and lateral) for the FM and atlas vertebra generally appeared longer for BMN-111-treated mice but did not reach significance, possibly as a result of the high variability associated with these parameters (Table 1). Histological analysis of the distal femur revealed dose-dependent modifications of the size of epiphyses, including a growth-plate expansion due to increased size of the prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones (Figure 4B). An initiation of columnar arrangement was observed, and the hypertrophic cells appeared larger with a more spherical shape. The magnitude of these phenotypic and histological changes, observed after only 10 days of treatment, was consistent with a previous study (Yasoda et al.19) evaluating the effect of 3 weeks of continuous CNP IV infusion in Fgfr3ach/+ mice that, compared to Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice, presented with an attenuated dwarfism phenotype. In the Fgfr3ach/+ mice, SC administrations of CNP failed to improve bone growth.19

Figure 4.

CNP Analog Partially Corrected the Dwarfism of Fgfr3Y367C/+ Mice

(A) Phenotypic changes were observed in 800 μg/kg BMN-111-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (n = 9) compared to vehicle-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (n = 9) and included flattening of the skull and an increased length of the long bones and tail. Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice received once-daily SC administrations of BMN 111 or vehicle (0.03 mol/l acetic acid buffer solution, pH 4.0, containing 1% [w/v] benzyl alcohol and 10% [w/v] sucrose) for 10 days. All mice were dosed approximately 2 hr prior to the dark cycle.

(B) Histological safranin-O (top) or H&E staining of growth plates from Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice treated or not with 240 μg/kg or 800 μg/kg BMN 111 during 10 days. Dose-dependent modifications of the epiphysis were observed in distal-femur sections of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. The formation of the secondary ossification center was delayed in vehicle-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice compared to vehicle-treated Fgfr3+/+mice (arrow). CNP analog treatment (800 μg/kg) did not appear to accelerate the ossification process. The scale bars in the “Cartilage” and “Distal epiphysis” rows represent 200 μm, the scale bars in the “Growth plate” row represent 50 μm, and the scale bars in the “Hypertrophic zone” row represent 20 μm.

(C) Pictures of Fgfr3+/+ (n = 5) and Fgfr3Y367C/+ (n = 5) mice treated during 20 days with 800 μg/kg BMN 111. Phenotypic changes comprise evident lengthening and straightening of the limbs, as well as longer forelimbs and hind limbs, including paws and digits, in BMN-111-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+mice (n = 5).

(D) X-rays of the skeleton show flattening of the skull (arrow) and improvement in the snout (arrow) in BMN-111-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. X-rays of the hind limbs show straightening of both the tibia and femur in BMN-111-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (arrows) and a marked increased in the size of the digits (arrows).

(E) Histological analysis of the distal femur of Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice with or without BMN 111 treatment after 20 days. Rescue of the height and architecture of the different zones of the growth plate, along with replicating and hypertrophic chondrocytes organized in columns, was observed in BMN-111-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+mice. The shape and size of the proliferative zone, visualized by type-II-collagen (Col II) in-situ-hybridization labeling (type-II-collagen riboprobe21) and KI67 immunolabeling (KI67 antibody, 1:3,000 dilution, Abcam), were modified after 800 μg/kg BMN 111 treatment in Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice (arrows). The scale bar in the “Distal epiphysis” row represents 200 μm, and the scale bars in the “Growth plate,” “Col II,” and “KI67” rows represent 50 μm.

Table 1.

Summary of the Percent Increase in the Length of Various Bones or Body Segments and Measure of the Absolute Length of the FM and Atlas Vertebra of Fgfr3Y367C/+ Mice Treated with Vehicle or BMN 111 for 10 Days

| Fgfr3Y367C/+ |

Percent Increase in Length |

Absolute Length (mm, Mean ± SD) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasoanal Length | Tail | AP Skull | Femur | Tibia | L4–L6 | C0 Sagittal | C0 Lateral | C1 Sagittal | C1 Lateral | |

| Vehicle | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.95 ± 0.22 (n = 4) | 3.16 ± 0.22 (n = 4) | 2.37 ± 0.10 (n = 4) | 2.28 ± 0.12 (n = 4) |

| 240 μg/kg BMN 111 | 4.5%∗ | no Δ | 2.9% | 3.4%∗ | 3.7% | 2.8% | 2.90 ± 0.12 (n = 4) | 3.13 ± 0.29 (n = 4) | 2.45 ± 0.11 (n = 3) | 2.32 ± 0.24 (n = 3) |

| 800 μg/kg BMN 111 | 5.3%∗ | 8.0%∗ | 4.8%∗ | 5.2%∗ | 6.6%∗ | 3.3% | 3.08 ± 0.20 (n = 6) | 3.19 ± 0.19 (n = 6) | 2.41 ± 0.20 (n = 6) | 2.49 ± 0.16 (n = 6) |

A dose-dependent (240 or 800 μg/kg) increase in the length of the appendicular and axial skeletons was observed and was significant for the nasoanal length, tail, anterior-posterior (AP) skull, femur, and tibia (p < 0.05, ANOVA). Absolute lengths of the C0 (foramen magnum [FM]) and C1 (atlas vertebra) (sagittal and lateral dimensions) were not statistically different between BMN-111-treated and vehicle-treated Fgfr3Y367C/+ mice. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 with a one-way ANOVA (Tukey's post hoc test) comparing BMN-111-treated mice to vehicle-treated mice.

We next extended the administration period. The Fgfr3Y367C/+mice received once-daily SC administrations (800 μg/kg BMN 111) for 20 days. Treatment was again initiated at 7 days of age. We observed phenotypic changes that included flattening of the skull, elongation of the snout, improvement of the anterior crossbite, larger paws and digits, and longer and straightened tibias and femurs (Figure 4C and Figure 4D). The tail was also longer and had some kinks, suggesting an overdose of BMN 111, as seen in mice overexpressing CNP (Figure 4D).15 Noteworthy, Fgfr3-knockout mice30,31 also exhibited overgrowth and tail kinks, consistent with involvement of the same pathway. The growth-plate-related histological changes were evident (Figure 4E). A rescue of the height and architecture of the different zones of the growth plate was observed. The height of the proliferative zone was increased, as shown by labeling with type II collagen and KI67 (marker of proliferation); the replicating chondrocytes were organized in columns parallel to the long axis of the bone. In the hypertrophic zone, the terminally differentiated chondrocytes recovered a columnar alignment. The shape and size of the proliferative and hypertrophic chondrocytes were corrected (Figure 4E). BMN 111 treatment led to the largest improvement in skeletal parameters observed to date in a mouse model with an Fgfr3 gain-of-function mutation.

Herein, we demonstrated that BMN 111, a CNP analog with an extended half-life due to NEP resistance, counteracts constitutive FGFR3 activation, which is the cause of abnormal cellular proliferation and differentiation in ACH cartilage. Inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation was translated in situ into increased bone growth, associated with a correction of the chondrocyte differentiation, and normalization of growth-plate architecture. Once-daily SC administrations of BMN 111 for 20 days improved the dwarfism of an Fgfr3 mouse model recapitulating ACH. Amelioration in key relevant ACH clinical features, including a bowed femur and tibia, anterior crossbite, and domed skull, was observed. These data support further development of this CNP analog as an investigational treatment for ACH and HCH.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mika Aoyagi-Scharber, Tim Taylor, Shinong Long, and Chris Price from BioMarin Pharmaceutical for providing BMN 111 (patent US2010-0297021). We thank Rachid Zoubairi for his work at the animal facility of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche Necker-Enfants Malades (Paris, France) and Eric Le Gall for the artwork. We are grateful to the Association des Personnes de Petites Tailles and the Fondation des gueules cassées for supporting the work of the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale team. This article is respectfully dedicated to the memory of David Rimoin in recognition of his pioneering contributions in skeletal dysplasias and his involvement in the early stage of the BMN 111 program. F.L., J.P., T.O., D.J.W., S.M.B., S. Bullens, S. Bunting, L.S.T., and C.A.O. are employees of BioMarin Pharmaceutical. This work was supported in part by a grant from BioMarin Pharmaceutical.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URL for data presented herein is as follows:

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org

References

- 1.Rousseau F., Bonaventure J., Legeai-Mallet L., Pelet A., Rozet J.M., Maroteaux P., Le Merrer M., Munnich A. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature. 1994;371:252–254. doi: 10.1038/371252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiang R., Thompson L.M., Zhu Y.Z., Church D.M., Fielder T.J., Bocian M., Winokur S.T., Wasmuth J.J. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarfism, achondroplasia. Cell. 1994;78:335–342. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton W.A., Hall J.G., Hecht J.T. Achondroplasia. Lancet. 2007;370:162–172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laederich M.B., Horton W.A. Achondroplasia: Pathogenesis and implications for future treatment. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2010;22:516–523. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833b7a69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonquoy A., Mugniery E., Benoist-Lasselin C., Kaci N., Le Corre L., Barbault F., Girard A.L., Le Merrer Y., Busca P., Schibler L. A novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor restores chondrocyte differentiation and promotes bone growth in a gain-of-function Fgfr3 mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:841–851. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C., Chen L., Iwata T., Kitagawa M., Fu X.Y., Deng C.X. A Lys644Glu substitution in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) causes dwarfism in mice by activation of STATs and ink4 cell cycle inhibitors. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:35–44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su W.C., Kitagawa M., Xue N., Xie B., Garofalo S., Cho J., Deng C., Horton W.A., Fu X.Y. Activation of Stat1 by mutant fibroblast growth-factor receptor in thanatophoric dysplasia type II dwarfism. Nature. 1997;386:288–292. doi: 10.1038/386288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legeai-Mallet L., Benoist-Lasselin C., Munnich A., Bonaventure J. Overexpression of FGFR3, Stat1, Stat5 and p21Cip1 correlates with phenotypic severity and defective chondrocyte differentiation in FGFR3-related chondrodysplasias. Bone. 2004;34:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murakami S., Balmes G., McKinney S., Zhang Z., Givol D., de Crombrugghe B. Constitutive activation of MEK1 in chondrocytes causes Stat1-independent achondroplasia-like dwarfism and rescues the Fgfr3-deficient mouse phenotype. Genes Dev. 2004;18:290–305. doi: 10.1101/gad.1179104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sebastian A., Matsushita T., Kawanami A., Mackem S., Landreth G.E., Murakami S. Genetic inactivation of ERK1 and ERK2 in chondrocytes promotes bone growth and enlarges the spinal canal. J. Orthop. Res. 2011;29:375–379. doi: 10.1002/jor.21262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasoda A., Komatsu Y., Chusho H., Miyazawa T., Ozasa A., Miura M., Kurihara T., Rogi T., Tanaka S., Suda M. Overexpression of CNP in chondrocytes rescues achondroplasia through a MAPK-dependent pathway. Nat. Med. 2004;10:80–86. doi: 10.1038/nm971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krejci P., Masri B., Fontaine V., Mekikian P.B., Weis M., Prats H., Wilcox W.R. Interaction of fibroblast growth factor and C-natriuretic peptide signaling in regulation of chondrocyte proliferation and extracellular matrix homeostasis. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:5089–5100. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasoda A., Ogawa Y., Suda M., Tamura N., Mori K., Sakuma Y., Chusho H., Shiota K., Tanaka K., Nakao K. Natriuretic peptide regulation of endochondral ossification. Evidence for possible roles of the C-type natriuretic peptide/guanylyl cyclase-B pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:11695–11700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chusho H., Tamura N., Ogawa Y., Yasoda A., Suda M., Miyazawa T., Nakamura K., Nakao K., Kurihara T., Komatsu Y. Dwarfism and early death in mice lacking C-type natriuretic peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4016–4021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071389098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bocciardi R., Giorda R., Buttgereit J., Gimelli S., Divizia M.T., Beri S., Garofalo S., Tavella S., Lerone M., Zuffardi O. Overexpression of the C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) is associated with overgrowth and bone anomalies in an individual with balanced t(2;7) translocation. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:724–731. doi: 10.1002/humu.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moncla A., Missirian C., Cacciagli P., Balzamo E., Legeai-Mallet L., Jouve J.L., Chabrol B., Le Merrer M., Plessis G., Villard L., Philip N. A cluster of translocation breakpoints in 2q37 is associated with overexpression of NPPC in patients with a similar overgrowth phenotype. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:1183–1188. doi: 10.1002/humu.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuji T., Kunieda T. A loss-of-function mutation in natriuretic peptide receptor 2 (Npr2) gene is responsible for disproportionate dwarfism in cn/cn mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:14288–14292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartels C.F., Bükülmez H., Padayatti P., Rhee D.K., van Ravenswaaij-Arts C., Pauli R.M., Mundlos S., Chitayat D., Shih L.Y., Al-Gazali L.I. Mutations in the transmembrane natriuretic peptide receptor NPR-B impair skeletal growth and cause acromesomelic dysplasia, type Maroteaux. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:27–34. doi: 10.1086/422013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasoda A., Kitamura H., Fujii T., Kondo E., Murao N., Miura M., Kanamoto N., Komatsu Y., Arai H., Nakao K. Systemic administration of C-type natriuretic peptide as a novel therapeutic strategy for skeletal dysplasias. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3138–3144. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt P.J., Richards A.M., Espiner E.A., Nicholls M.G., Yandle T.G. Bioactivity and metabolism of C-type natriuretic peptide in normal man. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1994;78:1428–1435. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.6.8200946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pannier S., Couloigner V., Messaddeq N., Elmaleh-Bergès M., Munnich A., Romand R., Legeai-Mallet L. Activating Fgfr3 Y367C mutation causes hearing loss and inner ear defect in a mouse model of chondrodysplasia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1792:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright M.J., Irving M.D. Clinical management of achondroplasia. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012;97:129–134. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.189092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashita Y., Takeshige K., Inoue A., Hirose S., Takamori A., Hagiwara H. Concentration of mRNA for the natriuretic peptide receptor-C in hypertrophic chondrocytes of the fetal mouse tibia. J. Biochem. 2000;127:177–179. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legeai-Mallet L., Benoist-Lasselin C., Delezoide A.L., Munnich A., Bonaventure J. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations promote apoptosis but do not alter chondrocyte proliferation in thanatophoric dysplasia. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13007–13014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benoist-Lasselin C., Gibbs L., Heuertz S., Odent T., Munnich A., Legeai-Mallet L. Human immortalized chondrocytes carrying heterozygous FGFR3 mutations: An in vitro model to study chondrodysplasias. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2593–2598. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozasa A., Komatsu Y., Yasoda A., Miura M., Sakuma Y., Nakatsuru Y., Arai H., Itoh N., Nakao K. Complementary antagonistic actions between C-type natriuretic peptide and the MAPK pathway through FGFR-3 in ATDC5 cells. Bone. 2005;36:1056–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazarus J.E., Hegde A., Andrade A.C., Nilsson O., Baron J. Fibroblast growth factor expression in the postnatal growth plate. Bone. 2007;40:577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mericq V., Uyeda J.A., Barnes K.M., De Luca F., Baron J. Regulation of fetal rat bone growth by C-type natriuretic peptide and cGMP. Pediatr. Res. 2000;47:189–193. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agoston H., Khan S., James C.G., Gillespie J.R., Serra R., Stanton L.A., Beier F. C-type natriuretic peptide regulates endochondral bone growth through p38 MAP kinase-dependent and -independent pathways. BMC Dev. Biol. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colvin J.S., Bohne B.A., Harding G.W., McEwen D.G., Ornitz D.M. Skeletal overgrowth and deafness in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat. Genet. 1996;12:390–397. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng C., Wynshaw-Boris A., Zhou F., Kuo A., Leder P. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is a negative regulator of bone growth. Cell. 1996;84:911–921. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.