Abstract

Objective

Executive deficits may play an important role in late-life suicide. Yet, current evidence in this area is inconclusive and does not indicate whether these deficits are broadly associated with suicidal ideation or specific to suicidal behavior. This study examined global cognition and specifically executive function impairments as correlates of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior in depressed older adults, with the goal of extending an earlier preliminary study.

Design

Case-control study.

Setting

University-affiliated psychiatric hospital.

Participants

All were aged 60+: 83 depressed suicide attempters, 43 depressed individuals having suicidal ideation with a specific plan, 54 non-suicidal depressed participants, and 48 older adults with no history of psychiatric disorders.

Measurements

Global cognitive function - Dementia Rating Scale (DRS), Executive function - Executive Interview (EXIT).

Results

Both suicide attempters and suicide ideators performed worse than the two comparison groups on the EXIT, with no difference between suicide attempters and suicide ideators. On the DRS total score, as well as on Memory and Attention subscales, suicide attempters and ideators and non-suicidal depressed subjects performed similarly and were impaired relative to with non-psychiatric control subjects. Controlling for education, substance use disorders, and medication exposure did not affect group differences in performance on either the EXIT or DRS.

Conclusions

Executive deficits, captured with a brief instrument, are associated broadly with suicidal ideation in older depressed adults but do not appear to directly facilitate suicidal behavior. Our data are consistent with the idea that different vulnerabilities may operate at different stages in the suicidal process.

Keywords: suicide, cognitive, executive function, depression, aged

INTRODUCTION

Suicide rates in older adults are higher than in younger adults in most countries in the world (1), and suicidal behavior appears to be particularly lethal in old age (2).

Current evidence on risk factors for late life suicide implicates depression often complicated by psychosis and substance use, burden of physical illness, loss, interpersonal discord, and financial stressors. Yet, these factors appear to trigger suicidal behavior only in a small fraction of exposed individuals, and the nature of the suicidal diathesis in late-life remains poorly understood. For example, cognitive impairment, highly prevalent in late-life depression (3–6), has not been adequately investigated as a component of the suicidal diathesis in late-life (7, 8).

Neuropsychological impairment is associated with suicidal behavior, specifically as demonstrated by performance on cognitive tasks measuring sustained attention, response inhibition, perseveration, set-shifting, and verbal fluency (9–15). In the first comprehensive study of cognitive performance in attempted suicide, Keilp and colleagues (10) found evidence of executive deficits in high-lethality suicide attempters, specifically on tasks requiring organization and focused effort: the Stroop interference task, the A not B task, verbal fluency task, and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST), where suicide attempters failed to maintain cognitive set (10). Subsequent studies have found impairment in specific aspects of executive function, including attentional control (11, 15), response inhibition (14), and verbal fluency (9). However, the findings of these studies are inconclusive; their implications for the cognitive diathesis of suicide are complicated by small sample sizes, the inclusion of individuals with a distant history of suicidal behavior and depression, and especially the lack of suicide ideator control groups.

Few studies specifically examined the relationship of current suicidal ideation, in addition to history of suicidal behavior, with cognitive performance. Marzuk et al. (16) examined the association between current suicidal ideation and neuropsychological functioning by comparing a group of adults who were seriously contemplating suicide (60% with past suicide attempts) with a group of non-suicidal depressed participants (40% with past suicide attempts). The group with current suicidal ideation performed worse on several measures of executive function, specifically on tasks assessing set-shifting (e.g., the WCST, Trails Making Test Part B, and the Mazes subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III), but showed no impairment on other cognitive measures. The authors concluded that current suicidal ideation, regardless of history of suicide attempt, may be associated with impaired executive function. Westheide et al. (14) found that only suicide attempters with current suicidal ideation, compared to attempters with no current suicidal ideation displayed executive deficits, most notably on impulsive decision-making. The conclusions of these studies were limited by either the lack of a suicide ideator group without past attempts, or the inclusion of mixed ideator and attempter participants.

While executive function declines in old age, very few studies have examined the role of executive functioning in late-life suicidal behavior. King et al. (17) assessed the role of impaired executive functioning in late-life suicide in a small group of older adults using the Trail Making Test Part B and found an interaction between age and suicide attempt, which the authors interpreted as evidence of an accelerated decline in executive function with age in suicide attempters compared to non-attempters. In our preliminary study of executive deficits in a small group (N=64) of suicidal and non-suicidal depressed older adults using the Executive Interview (EXIT) and the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS), suicidal depressed older adults exhibited greater executive deficits than did non-suicidal individuals with depression (18). We have also found evidence of impaired probabilistic reversal learning in older suicide attempters, but not in suicide ideators (19) as well as a deficit in deterministic learning on the WCST in high-lethality suicide attempters (20).

The present case-control study aimed to examine whether executive function impairments are associated with contemplation of suicide (16), suicidal behavior (10, 11, 17), or both, in late life, above and beyond the effect of depression. Thus, we report performance on the EXIT in both suicide attempters and suicide ideators separately, compared with groups of non-suicidal depressed older adults, and older adults with no lifetime psychiatric history. Our objective was to test the prediction that suicide attempters will be impaired in their executive function, compared to suicide ideators, non-suicidal depressed participants, and the non-psychiatric comparison group.

METHODS

Study Groups

To examine cognitive impairment in suicidal depressed older adults, we studied three groups of participants aged 60 and older with current episodes of non-psychotic unipolar major depression, as determined by administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Axis I Disorders (SCID/DSMIV): 83 depressed suicide attempters, 43 depressed individuals with suicidal ideation but no history of suicide attempts, 54 non-suicidal depressed participants, and 48 older adults with no history of psychiatric disorders. Participants were required to have no history of neurological disorders, delirium, or sensory disorders that preclude neuropsychological assessment, but prior history of head trauma was not an exclusion criterion unless it led to significant brain damage as determined by perusal of medical and neurologic history. None of the participants had an existing clinical diagnosis of, or were receiving treatment for, dementing disorders. Depressed individuals receiving electroconvulsive therapy in the previous 6 months were excluded from the study. Participants were required to earn a minimum score of 18 on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) during initial recruitment; however, the minimum MMSE score required for participation was later increased to 24 (range 24–30). All participants provided written informed consent. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Suicide Attempters (n = 83)

Suicide attempters had a self-injurious act with the intent to die and current suicidal ideation. Suicide attempt history was verified by a psychiatrist (AYD or KSz), using all available information: participant report, medical records, information from the treatment team, and collateral information from family or friends.

Significant discrepancies between these sources led to exclusion from the study. Medical seriousness of attempts was assessed using the Beck Lethality Scale (BLS) scored on a scale from 0–8 (21); for participants with multiple attempts, data for the highest-lethality attempt are presented. Suicide attempters had a mean BLS score of (3.4 [2.2]). Forty-five of 83 suicide attempters engaged in a high-lethality attempt (BLS score ≥ 4) and 38 attempters had a low-lethality attempt (BLS score < 4). None of the suicide attempters had experienced head injuries directly related to attempt, however we assessed potential anoxic-ischemic or toxic brain injury, based on the BLS, medical records and the clinical interview. We excluded suicide attempters who had suffered severe anoxic brain injuries resulting in clinical cognitive decline. For 8/83 suicide attempters, the possibility of anoxic brain injury could not be excluded, and for 10/83 cases there was a possibility of anoxic damage, but no cognitive decline by clinical history. Suicidal intent associated with suicide attempts was assessed using the Beck Suicide Intent Scale (SIS), which is scored from 0–30 (22). Suicide intent on the SIS was high: (mean[SD]) (17.6[4.8]). Current and worst suicidal ideation was assessed using the Beck Scale of Suicidal Ideation (SSI), which is scored from 0–38 (23). Suicide attempters’ mean current suicidal ideation score on the SSI was also high (21.0 [8.4]) and mean worst suicidal ideation in lifetime score on the SSI was 25.0 (5.6).

Suicide Ideators (n = 43)

Suicide ideators were required to endorse suicidal ideation with a specific plan but had no lifetime history of suicide attempt. These participants seriously contemplated suicide and communicated this intention to their family or medical professionals, typically triggering an inpatient admission or an increase in the level of outpatient care. These participants constitute a very high-risk group, as they had not only contemplated suicide, but had a concrete plan to kill themselves. Participants with passive death wish or transient or ambiguous suicidal ideas were excluded from this group. The mean suicidal ideation score on the SSI for past month and worst lifetime for suicide ideators was high: (13.9 [5.0]) and (15.5 [7.5]), respectively.

Data on 20 suicide attempters and 12 suicide ideators were included in our preliminary report (18). Thus, to replicate our preliminary findings, we performed an additional analysis excluding those participants, as described below under Sensitivity and exploratory analyses.

Non-Suicidal Depressed Participants (n = 54)

A comparison group of non-suicidal depressed older adults was used to determine whether there is an association between suicidality (either ideation, attempt, or both) and impaired cognitive function above and beyond, or different from, the effect of depression on cognitive function in older adults. These participants had a SCID/DSM-IV diagnosis of current major depressive episode and a score of 14 or higher on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17) (mean score of 18.7 [3.9]) (24). Non-suicidal depressed participants had no lifetime history of self-injurious behavior, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempts, and were judged to be non-suicidal based on the clinical interview, review of medical records, SCID/DSMIV, and a score of 0 on the HRSD-17 suicide item.

Non-Psychiatric Comparison Participants (n = 48)

A group of older adults with no lifetime history of psychiatric disorder and suicidal ideation or attempt, as determined by the SCID/DSM-IV and the SSI, was included as a reference group. Participants for this comparison group were recruited primarily by referrals from other research studies and using flyer advertisements at local primary care clinics.

Assessments

Clinical Assessments

We assessed depression severity with the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (24); comorbid physical illness with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale adapted for Geriatrics (25); and level of hopelessness with the Beck Hopelessness Scale (26). We obtained medication lists from pharmacy records to assess physical illness burden and psychotropic medication exposure. We measured the intensity of pharmacotherapy for the current episode of depression with the Antidepressant Treatment History Form (27). The ATHF score is based on antidepressant trial duration in addition to the dose and also reflects the use of augmenting agents (e.g. antipsychotics, lithium).

Cognitive Assessments

We assessed a spectrum of executive functions with the Executive Interview (EXIT) (28) (range 0–50). The 25 items comprising this screening test are administered in rapid succession with minimal instructions and elicit automatic behaviors and disinhibition and also include modifications of well-known “frontal lobe” tests (number/letter sequencing, Stroop, fluency tests, go/no-go tests, and Luria’s hand sequences). We also administered the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) (29), a screening test of global cognitive function (0–144). The DRS comprises subscales assessing Initiation/Perseveration, Attention, Construction, Conceptualization, and Memory. Higher EXIT scores and lower DRS scores indicate greater impairment. Finally, we administered the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) as a proxy measure of premorbid intelligence on a sub-sample of participants (N=109) (30).

Procedures

Our study of late-life suicide was conducted on a psychogeriatric inpatient unit and an outpatient research clinic of a university-affiliated hospital. Participants were assessed within two weeks of inpatient admission or at the beginning of treatment as outpatients. Patients continued to receive psychotropic medications as clinically indicated. Neuropsychological assessment took place in one to two sessions lasting a total of 2–2.5 hours over 1–3 days. Assessors were blind to clinical history and ratings.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). We first examined the distributions of EXIT and DRS scores to determine whether parametric tests are appropriate.

Primary analyses

We compared groups on demographic and clinical characteristics using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests. For our primary analyses, we used ANOVAs to test group differences in EXIT and DRS scores. We applied the Bonferroni correction to the family of tests for DRS total score and subscales, to minimize type 1 error inflation. For all ANOVAs, we examined post-hoc contrasts using the Tukey HSD test.

Sensitivity and exploratory analyses

We adjusted for sources of unwanted variance by conducting ANCOVAs. First, we included highest level of education attained and the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) as covariates. Second, we excluded participants with a history of substance use disorders or possible brain damage secondary to a suicide attempt. We also examined correlations between psychotropic exposure and EXIT performance.

Next, we used ANOVAs to assess the effect of time since suicide attempt on executive functioning. We also conducted ANOVAs excluding participants in the preliminary study to determine the replicability of our earlier findings of impaired executive function in suicidal depressed older adults (18) in a larger sample. Our exploratory analyses examined possible state effects of severity of current suicidal ideation and recency of suicide attempts on EXIT scores.

RESULTS

Group characteristics

All four groups were comparable in terms of age, gender, race, and the depressed groups were comparable with regard to severity of depression (Table 1). Non-suicidal depressed participants had more medical comorbidity (CIRS-G scores) than the non-psychiatric control group. Intensity of antidepressant pharmacotherapy during current depressive episode was greater for the suicide ideators compared to non-suicidal depressed participants, but not compared to the suicide attempters (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of suicidal and non-suicidal depressed elderly participants.

| Attempters | Ideators | Nonsuicidal Depressed | Non-Psychiatric Controls | F or χ2 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 83 | 43 | 54 | 48 | -- | -- |

| Age* | 69.4 (8.8) | 69.9 (8.5) | 70.7 (8.4) | 69.1 (7.1) | 0.38 | 0.77 |

| Education, yrs* | 13.0 (2.9) | 13.7 (3.4) | 14.2 (2.6) | 14.6 (2.6) | 3.77 | 0.01 |

| %Men** | 51% | 53% | 33% | 52% | 5.69 | 0.13 |

| %White** | 86% | 84% | 81% | 88% | 3.71 | 0.72 |

| %Substance Use Disorders** | 35% | 19% | 17% | -- | 10.21 | 0.04 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale adapted for geriatrics * (CIRS-G) | 8.9 (4.4) | 8.2 (3.1) | 9.7 (3.4) | 7.3 (3.2) | 3.61 | 0.01 |

| Antidepressant exposure*,*** (ATHF) | 2.15(2.2) | 2.67 (2.47) | 1.38 (1.71) | -- | 2.94 | 0.06 |

| 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale* | 22.7 (5.8) | 22.5 (4.9) | 18.7 (3.9) | 2.5 (1.9) | 222.73 | <0.01 |

| Beck Hopelessness Scale* | 10.0 (6.4) | 11.0 (6.4) | 5.7 (5.4) | 1.3 (1.3) | 33.5 | <0.01 |

| Beck Scale of Suicidal Ideation* | 25.0 (5.6) | 15.5 (7.5) | -- | -- | 5.7 | 0.02 |

| Beck Suicidal Intent Scale | 17.6 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | -- | -- |

ANOVA (Age: df= (3,224). Education: df=(3,224), Cumulative Illness Rating Scale adapted for geriatrics: df=(3,216), Antidepressant Treatment History Form: df=(3,132), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: df=(3,222), Beck Hopelessness Scale: df=(3,212), Beck Scale of Suicidal Ideation: df=(3,211))

Chi-Square test (Gender: df=3, Race: df=6, Substance use disorders: df=6)

Measured by the Antidepressant Treatment History Form

Prevalence of substance use disorders was greater in suicide attempters compared to suicide ideators and non-suicidal depressed participants (Table 1). Suicide attempters also had a lower level of education and lower MMSE scores compared to the non-psychiatric control participants (Table 1,2). Fifty-nine percent of the suicide attempters made their first attempt after age 60. Fifty-nine percent of suicide attempters made one lifetime attempt, 23% made two attempts, and 18% made 3 or more attempts.

Table 2.

Executive functioning and global cognition in suicide attempters, suicide ideators, and nonsuicidal depressed and non-psychiatric control elderly participants

| Attempters | Ideators | Nonsuicidal Depressed | Non-Psychiatric Controls | p | η2 | Post Hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) | 26.3 (3.0) | 27.3 (2.87) | 28.1 (1.7) | 28.5 (1.6) | <0.01 | 0.13 | A < D,N |

| Executive Interview (EXIT) | 10.6 (5.3) | 10.6 (6.4) | 7.6 (4.2) | 6.5 (3.3) | <0.01 | 0.12 | A,I > D, N |

| Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) Total Score | 130.6 (8.2) | 129.6 (10.6) | 134.0 (5.5) | 137.7 (2.8) | <0.01 | 0.13 | A,I < N |

| DRS Initiation/Perseveration | 34.6 (3.4) | 34.1 (4.4) | 35.5 (2.3) | 36.5 (1.3) | <0.01 | 0.07 | A,I < N |

| DRS Attention | 35.1 (1.7) | 34.7 (1.9) | 35.5 (1.2) | 36.0 (0.9) | <0.01 | 0.09 | I < N |

| DRS Construction | 4.9 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.0 (0.6) | 5.1 (0.8) | 0.66 | 0.01 | -- |

| DRS Conceptualization | 35.1 (3.6) | 35.1 (3.7) | 36.0 (2.7) | 37.0 (1.9) | 0.03 | 0.07 | A < N |

| DRS Memory | 21.7 (3.0) | 20.9 (3.5) | 22.1 (2.8) | 23.1 (1.1) | <0.01 | 0.08 | A,I < N |

ANOVAs performed for MMSE, EXIT total score, DRS total score, and DRS subscales (MMSE: df=(3,209), EXIT: df=(3,184), DRS total score and DRS subscales: df=(3,182))

Cognitive Function: Primary Analysis

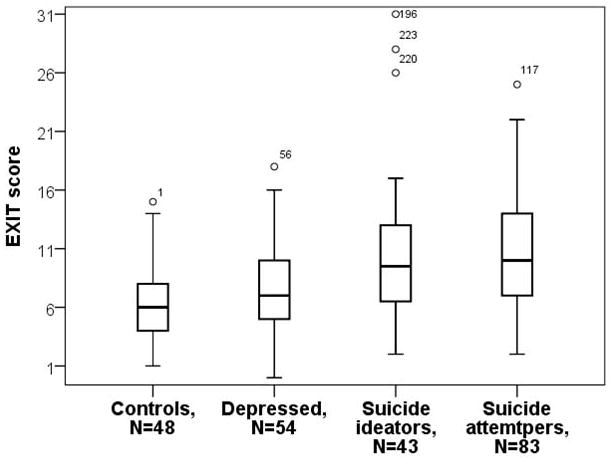

Suicide attempters and suicide ideators both performed more poorly on the EXIT than the nonsuicidal depressed and non-psychiatric comparison groups (See Figure 1 and Table 2). There was no difference in performance on the EXIT between attempters and ideators (attempters: mean=10.6, SD= 5.3; and ideators: mean=10.6, SD= 6.4).

Figure 1.

Executive functioning in elderly suicide attempters, ideators, nonsuicidal depressed participants, and non-psychiatric comparison group.

After adjusting for multiple comparisons, we found that suicide attempters and suicide ideators both performed significantly worse on the DRS total scale and DRS subscales assessing Initiation/Perseveration and Memory, compared to the non-psychiatric control group (See Table 2). The suicide ideators also performed worse than the non-suicidal depressed group on the DRS total score and DRS Attention subscale (See Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

The group differences in performance on the EXIT remained significant after accounting for differences in level of education (EXIT: ANCOVA, Group effect: F= 6.40, df=(3,187), p< 0.01; Education effect: F= 22.61, df=(1,187), p< 0.01) and premorbid intelligence (ANCOVA, Group effect: F= 3.07, df=(3,91), p=0.03, η2= 0.10; Age effect: F= 26.64, df=(1,91), p<0.01, η2= 0.24; WTAR effect: F=4.36, df=(1,91), p= 0.04). Group differences in performance on the EXIT also remained significant after excluding participants with lifetime history of substance use disorders (ANOVA, F=7.84, df= (3,146), p<0.01) or with possible brain injury secondary to suicide attempt (ANOVA, F=8.29, df=(3,170), p<0.01). In depressed participants psychotropic medication exposure measured by the ATHF did not affect performance on the EXIT or the DRS (EXIT: Pearson’s r=.17, df=106, p=.14; DRS: r=.09, df=106, p=.41).

Exploratory analyses: possible state effects

We examined possible state effects of suicidal ideation on cognitive performance and found no correlation between severity of current suicidal ideation and performance on the EXIT (Pearson Correlation, r=0.13, df=175, p=0.20). As some of the suicide attempters had remote attempts while about half of them attempted suicide within two weeks of the assessments, we also tested differences between current and past attempters on EXIT performance, and we did not find any differences (ANCOVA, Current vs. Past Attempt effect: F= 0.73, df=(2,187), p=0.40; Age effect: F= 15.44, df=(1,187), p<0.01).

Replication analyses

The findings from our preliminary study were replicated in a non-overlapping sample of 196 participants, using the same analytic approach as in our preliminary study (18). Suicidal participants (suicide ideators and attempters combined) performed worse than the non-suicidal depressed participants on the DRS and the EXIT after covarying for age (DRS: ANCOVA, Group effect: F= 12.59, df= (2,185), p<0.01; Age effect: F=45.55, df=(1,185), p<0.01; EXIT: ANCOVA, Group effect: F= 5.69, df=(2,187), p=0.001; Age effect: F=35.0, df=(1,187), p< 0.01).

DISCUSSION

In this case-control cross-sectional study, we found that depressed older suicide attempters and depressed elderly with current suicidal ideation but no history of suicide attempt were similarly impaired in executive functioning on the EXIT. This finding remained after accounting for the effects of education, premorbid intelligence, substance use disorders, and brain injury on executive functioning. Thus, our hypothesis of selective executive impairment in suicide attempters was not supported. Suicide attempters and suicide ideators also displayed impaired initiation/perseveration and memory on the DRS compared to older adults without psychiatric history, but not compared to non-suicidal depressed older adults.

Suicidal behavior never occurs without contemplation. On the other hand, most individuals who contemplate suicide never act on those thoughts. The present study links executive dysfunction with the emergence of suicidal ideas rather than their implementation. Marzuk and colleagues (16) similarly found that current suicidal was related to executive deficits regardless of history of suicidal behavior. Later, Westheide et al. (14) also found that only suicide attempters with current suicidal ideation, compared to attempters with no current suicidal ideation displayed cognitive impairments in decision-making and motor inhibition (31).

While the EXIT was originally developed as a measure of executive functions (28), we also considered the EXIT items from the perspective of Miller & Cohen’s later conceptualization of cognitive control, namely, the ‘active maintenance of patterns of activity in the prefrontal cortex that represent goals and the means to achieve them by way of bias signals that promote task-appropriate responding’ (32). Eight of the 25 EXIT items assess the ability to inhibit an automatic behavior, and three items capture error detection or conflict monitoring. These items fall precisely into the above definition of cognitive control (see also (33,34). Future studies could usefully focus on cognitive control as a specific facet of executive function that may be relevant to the emergence of suicidal thoughts.

It is difficult to say to what extent our results affect the interpretation of earlier findings of association of suicide attempt history with executive impairment in younger individuals (10, 15, 35), not only because of the difference in age, but also because different tests were used. A conservative conclusion would be that the stage of the suicidal process where executive deficits may play a role is yet to be established. There is evidence that social stressors, known to trigger suicidal thoughts, lead to a deterioration of executive control and self-regulation (31). Other studies have found that current suicidal ideation may be a stronger predictor of executive functioning deficits compared to history of suicidal behavior (14, 16). Because all suicidal participants in our study had current suicidal ideation at the time of cognitive assessment, this study cannot adequately assess the extent to which executive functioning deficits precede or follow the onset of suicidal ideation. Our findings, taken together with those of Marzuk et al. (16) and Westheide et al. (14), are consistent with the notion that executive function deficits may contribute to the emergence of suicidal thoughts, but not specifically the final act of ending one’s life. However, because group differences in performance on the EXIT were notable but small in our sample, our findings are more suggestive rather than definitive, and require replication in larger samples.

Limitations

A key limitation of our study is the cross-sectional case-control design, which precludes causal inferences. Also, because most participants in both suicidal groups were assessed as inpatients, compared to less than half of the non-suicidal depressed group and none of the non-psychiatric control group, being in an unfamiliar environment and other factors associated with hospitalization may have affected cognitive performance in the suicidal groups.

Second, our suicide ideator group was limited to those having suicidal ideation with a specific plan and may not be representative of older adults with less serious suicidal ideation. However, the lack of a correlation between severity of suicidal ideation and performance on the EXIT in our study argues against the possibility that severity of suicidal ideation is associated with the level of executive impairment in suicidal older adults. Still, future studies need to examine whether executive function deficits in older adults are specifically related to the emergence of a suicidal plan.

Another limitation of the study is that a subgroup of suicide attempters and ideators in our sample displayed some evidence of prodromal or early stage dementia. While dementia in general is not a strong risk factor for late-life suicide (36), these observations raise the possibility that for a subgroup, the interval of increased risk for suicidal behavior may be at its prodromal or early stage (37). This study is not designed to specifically investigate suicide risk in elderly with cognitive impairment, because we excluded subjects diagnosed with dementia. Yet, the relatively low MMSE and DRS scores show that some of our participants had undiagnosed mild cognitive impairment and others functioned in the dementia range. Future research should formally assess relationship between suicidal behavior and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in older depressed patients, given the high prevalence of MCI in late-life depression and its implications for short- and long-term illness course and treatment response (38).

In conclusion, we found that depressed elderly who either contemplated or attempted suicide are impaired in executive function and global cognitive function. Our findings do not support a direct contribution of executive function deficits to suicidal behavior, but rather a more indirect role in the emergence of suicidal ideation. Our results also suggest that, in order to make specific inferences about suicidal behavior, case-control studies should preferably include a control group with suicidal ideation but no suicide attempt.

Acknowledgments

Supported by: grants R01 MH05436, K23 MH086620, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Junior Investigator grant to Katalin Szanto, R01 MH072947, P30 MH90333, and the UPMC Endowment in Geriatric Psychiatry

Footnotes

No Disclosures to Report.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Suicide prevention. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TCKA, Bunney WE, editors. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, D.C: THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abas MA, Sahakian BJ, Levy R. Neuropsychological deficits and CT scan changes in elderly depressives. Psychol Med. 1990;20:507–520. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheline YI, Barch DM, Garcia K, et al. Cognitive function in late life depression: relationships to depression severity, cerebrovascular risk factors and processing speed. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexopoulos G, Kiosses DN, Klimstra S, Kalayam, Bruce BML. Clinical presentation of the “depression-executive dysfunction syndrome” of late-life. American Journal of GeriatricPsychiatry. 2002;10:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butters MA, Whyte EM, Nebes RD, et al. The nature and determinants of neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:587–595. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jollant F, Lawrence NL, Olie E, et al. The suicidal mind and brain: A review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2011;34:451–468. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartfai A, Winborg IM, Nordstrom P, et al. Suicidal behavior and cognitive flexibility: design and verbal fluency after attempted suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1990;20:254–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keilp JG, Sackeim HA, Brodsky BS, et al. Neuropsychological dysfunction in depressed suicide attempters. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:735–741. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Oquendo MA, et al. Attention deficit in depressed suicide attempters. Psychiatry Research. 2008;159:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jollant F, Bellivier F, Leboyer M, et al. Impaired decision making in suicide attempters. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:304–310. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jollant F, Guillaume S, Jaussent I, et al. Characterization of Decision-Making Impairment in Suicide Attempters and the Influence of Attention to Wins on Suicidal Intent and Repetition. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:292S. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westheide J, Quednow BB, Kuhn KU, et al. Executive performance of depressed suicide attempters: the role of suicidal ideation. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cha CB, Najmi S, Park JM, et al. Attentional bias toward suicide-related stimuli predicts suicidal behavior. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2010;119:616–622. doi: 10.1037/a0019710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marzuk PM, Hartwell N, Leon AC, et al. Executive functioning in depressed patients with suicidal ideation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112:294–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King DA, Conwell Y, Cox C, et al. A neuropsychological comparison of depressed suicide attempters and nonattempters. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences. 2000;12:64–70. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Cognitive Performance in Suicidal Depressed Elderly: Preliminary Report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:109–115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180f6338d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dombrovski AY, Clark L, Siegle GJ, et al. Reward/Punishment reversal learning in older suicide attempters. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:699–707. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGirr A, Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, et al. Deterministic learning and attempted suicide among older depressed individuals: Cognitive assessment using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task. J Psychiatr Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M. Classification of suicidal behaviors: I. Quantifying intent and medical lethality Am J Psychiatry. 1975;132:285–287. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT, Shuyler D, Herman I. Development of suicidal intent scales. In: Beck AT, Resnik HLP, Lettieri DJ, Bowie MD, editors. The prediction of suicide. Charles Press; 1974. pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, et al. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1992;41:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, et al. The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sackeim HA. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 (Suppl 16):10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray KF. Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: the executive interview. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1221–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb03646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale (DRS): Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler D. The Wechsler Test of Adult Reading: WTAR. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, et al. Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:589–604. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridderinkhof KR, van den Wildenberg WP, Segalowitz SJ, et al. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: the role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward-based learning. Brain Cogn. 2004;56:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, et al. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol Rev. 2001;108:624–652. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raust A, Slama F, Mathieu F, et al. Prefrontal cortex dysfunction in patients with suicidal behavior. Psychol Med. 2007;37:411–419. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haw C, Harwood D, Hawton K. Dementia and suicidal behavior: a review of the literature. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:440–453. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209009065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seyfried LS, Kales HC, Ignacio RV, et al. Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Butters MA, Lopez O, et al. Maintenance treatment of depression in old age: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the efficacy and safety of donepezil combined with antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:51–60. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]