Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem in clinical settings as well as in food industry. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) commercially used as starter cultures and probiotic supplements are considered as reservoirs of several antibiotic resistance genes. Macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin (MLS) antibiotics have a proven record of excellence in clinical settings. However, the intensive use of tylosin, lincomysin and virginamycin antibiotics of this group as growth promoters in animal husbandry and poultry has resulted in development of resistance in LAB of animal origin. Among the three different mechanisms of MLS resistance, the most commonly observed in LAB are the methylase and efflux mediated resistance. This review summarizes the updated information on MLS resistance genes detected and how resistance to these antibiotics poses a threat when present in food grade LAB.

Keywords: Lactic acid bacteria, Erythromycin resistance genes, Fermented foods, Conjugative plasmid, Transposon

Introduction

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are a taxonomically diverse group of microorganisms that can convert fermentative carbohydrates into lactic acid [1]. The most typical LAB members are organisms with low G+C content, belonging to the genera Lactobacillus (L), Lactococcus (Lc), Leuconostoc (Le) and Pediococcus (P) [2]. LAB are ubiquitous in nature and important microorganisms in the gastro intestinal tract (GIT) of humans and animals [3]. In fermented foods, they are present as contaminants or deliberately added as starter cultures for preparation and preservation purposes. [4]. Owing to their long history of consumption, LAB are considered to be non pathogenic and given the status “Generally Regarded As Safe” (GRAS) [4]. For a better understanding of their safety for human consumption, European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) [5] has outlined a scheme based on qualified presumption of safety (QPS) set on establishment of identity, body of knowledge, possible pathogenicity and end use of a taxonomic group [6]. The Gram-positive bacteria considered for QPS assessment require only qualification in the assessment of susceptibility to antibiotics except for Enterococcus species as they are associated with human infections, virulence factors, transferable antibiotic resistance (AR) and lack of information on safety [6].

Antibiotic Resistance in Food LAB and its Significance

The extension of clinical use of antibiotics to non-human applications (companion animals, aquaculture and horticulture) has exerted a very strong selective pressure resulting in the appearance of resistant strains [7]. As LAB may acquire AR and play a role in their transfer to pathogenic bacteria, the food chain has been considered as the main route for the introduction of AR bacteria into the GIT [4]. A number of initiatives have been recently launched across the globe to address the biosafety concerns of starter cultures and probiotic microorganisms. In order to check for signs of transferable AR in starter cultures, EFSA [5] has proposed “microbiological breakpoints” for several genera of LAB, that have also been updated [8]. The phenotypic analysis is now accompanied by molecular tests that detect specific AR genes using single or multiplex PCR, real time PCR and/or DNA microarrays [4]. In this review, the distribution, phenotypic and genotypic resistance to MLS antibiotics, association of MLS resistance with other AR genes, transposons and their mechanism of transfer in LAB has been reviewed.

MLS Resistance in LAB

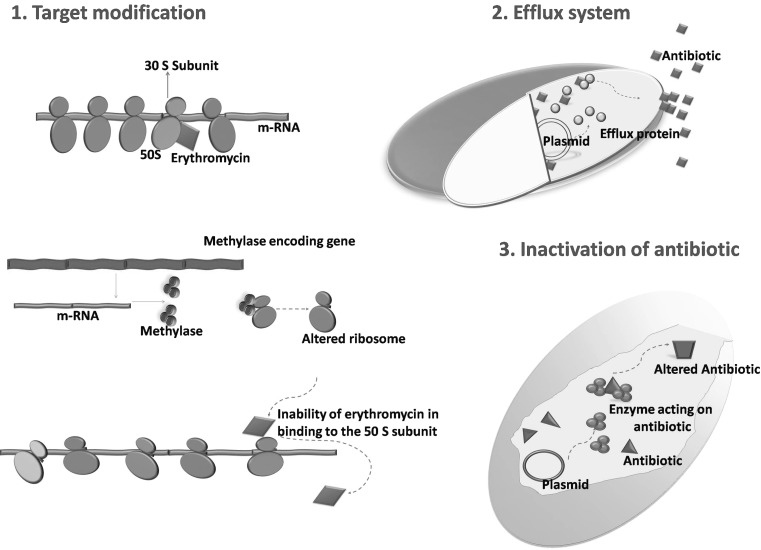

Erythromycin, produced by Saccharopolyspora eryhthraea was the first macrolide introduced in 1952 as an antibiotic against a wide range of clinical pathogens. Unfortunately, within a year, erythromycin resistant (ERr) staphylococci from US, Europe and Japan were discovered [9]. This has led to the development and increased use of newer macrolides, and thus enhanced the exposure of clinical bacteria to macrolide group of antibiotics (9, 10). Macrolides, Lincosamides, Streptogramins, Ketolides (semi-synthetic derivatives of erythromycin A) and Oxazolidinones (MLSKO) though chemically distinct, are usually grouped together that inhibit protein synthesis [11]. Currently, there are 66 MLSKO resistance genes identified in multiple genera that fall into three major headings; (1) Modification of the target site (2) Efflux pumps and (3) Inactivation of the antibiotic(s) [10, 11] (Fig. 1). Among the resistance genes, rRNA methylase(s) (erm) are the best studied that confer resistance to macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin B (MLSB) group antibiotics. As the MLSK antibiotics share overlapping binding sites on the 50S ribosomal subunit, modification of the ribosomal structure by methylases reduces the binding of this group of antibiotics to their targets [9].

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin antibiotics

The occurrence of MLS resistance in bacteria of animal origin is unlikely as these antibiotics are used mainly for clinical infections. However, administration of certain MLS antibiotics (tylosin, tilmicosin, lincomycin and virginamycin) as growth promoters and/or therapeutic agents in animal husbandry and poultry has imposed selective pressures on the development of MLS resistance in commensal bacteria [12]. There is now a growing concern regarding the food grade bacteria with frequent detection of MLS resistance genes in LAB isolated from animals, their products, fermented dairy products, starter cultures and also naturally fermented traditional foods.

MLS Resistant LAB from Farm Animals

The evidence of animals carrying MLS resistant LAB comes with the detection of erm(B) gene from diverse LAB isolated from different organs of swine [4]. A high degree of macrolide resistance was observed among Lactobacillus strains isolated from gastro intestinal tract (GIT) of chicken, pig and human and were found harboring erm genes [4, 13] (Table 1).

Table 1.

MLS resistance genes identified in lactic acid bacterial species from diverse sources

| Isolate | Source | Resistance gene | Localization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. reuteri | ||||

| 1044, N16,L1 | Pig and chicken intestine | erm(B) | [4] | |

| 100-63 | Poultry | erm(T) | [4] | |

| 8557-1, 1068, LMG-18391, 1048 | Human and pig intestine | erm(B) | Plasmid | [13] |

| PA-16 | Pig | erm(C) | Plasmid | [13] |

| 100-67 | Chicken intestine | erm(T) | Plasmid | [13] |

| 1 strain | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [19] | |

| 11 and 14 | Beef | erm(B), msr(A/B) | [22] | |

| SD 2112 | Probiotic strain | lnu(A) | [43] | |

| ATCC 55730 | Commercial probiotic strain | lnu(A) | Plasmid | [44] |

| CH2-2 | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [20] | |

| 1 strain | Poultry and pork meat | erm(B) | [23] | |

| L. sakei | ||||

| 5 strains | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [19] | |

| L. plantarum | ||||

| 3 strains | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [19] | |

| 2 strains | Fermented dry sausage | erm(C) | [19] | |

| DG507 | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | Plasmid | [21] |

| 80 isolates | Human origin and dairy products | erm(B) | [4] | |

| 6 strains | Poultry and pork meat | erm(B) | [23] | |

| NWL22 | Yogurt | erm(B) | [38] | |

| L. curvatus | ||||

| 10 strains | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [19] | |

| 26 | Beef | erm(B), msr(A/B) | [19] | |

| L. paracasei | ||||

| 1 strain | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [19] | |

| 20 | Pork | erm(B), msr(A/B) | [19] | |

| LMG 23371 and 23372 | erm(B) | [40] | ||

| L. brevis | ||||

| 2 strains | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [19] | |

| 1 strain | Poultry and pork meat | erm(C) | [23] | |

| L. rhamnosus | ||||

| 1 strain | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [19] | |

| 43 isolates | Human origin | erm(B) | [4] | |

| L. animalis | ||||

| NA | Pig tonsils and nasal cavities | erm(B) | [4] | |

| NWL39 | Fermented vegetable | erm(B) | [38] | |

| L. Johnsonii | ||||

| NA | Pig tonsils and nasal cavities | erm(B) | [4] | |

| 49 isolates | Human origin | erm(B) | [4] | |

| 4 strains | Poultry and pork meat | erm(B), erm(C) | [23] | |

| L. salivarius | ||||

| NA | Pig tonsils and nasal cavities | erm(B) | [4] | |

| 3 strains | Poultry and pork meat | erm(B) | [23] | |

| CHS1-E, CH7-1E | Fermented dry sausage | erm(B) | [20] | |

| NWL33 | Pickle | erm(B) | [38] | |

| L. crispatus | ||||

| CHCC3692 | Human origin | erm(B) | [4] | |

| L-295, L-296 | Probiotic isolate | erm(B) | [42] | |

| 2 strains | Poultry and pork meat | erm(B), erm(C) | [23] | |

| L. fermentum | ||||

| LEM89 | Pig faeces | erm(B) | [4] | |

| NWL24, NWL26 | Yogurt | erm(B) | [38] | |

| ROTI | Raw milk dairy product | erm(LF), vat(E) | [53] | |

| L. gasseri | ||||

| 49 isolates | Human origin and dairy products | erm(B) | [4] | |

| E. faecium | ||||

| 21, 25, 27, 30 | Pork | erm(B), msr(A/B) | [22] | |

| ~10 isolates | Beef processing plant | erm(B) | [17] | |

| 17 strains | Chicken, pork, meat and faecal samples | erm(B) | [30] | |

| 8 strains | Cheese and pharmaceutical product | erm(B), msr(A/B) | [51] | |

| 9 strains | Traditional fermented foods | erm(B), msr(C) | [20] | |

| E. faecalis | ||||

| 78 isolates | Different organs of Swine | erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), msr(C) and mef(A/E) | [15] | |

| ~20 isolates | Beef processing plant | erm(B), vat(E) | [17] | |

| 6 strains | Chicken, pork, meat and faecal samples | erm(B) | [30] | |

| 6 strains | Milk and cheese | erm(B) | [51] | |

| E. mundtii | ||||

| 1 strain | Chicken, pork, meat and faecal samples | erm(B) | [30] | |

| E. gallinarum | ||||

| 1 strain | Chicken, pork, meat and faecal samples | erm(B) | [30] | |

| E. durans | ||||

| 11 strains | Chicken, pork, meat and faecal samples | erm(B) | [30] | |

| 21 strains | Traditional fermented foods | erm(B), msr(C) | [20] | |

| P. acidilactici | ||||

| 6990 | Traditional cheese | erm(B) | Plasmid | [41] |

| J83 | Wine | erm(B | [42] | |

| HM3020 | Stools (Clinical samples) | erm(B | [4] | |

| AR-63 | Pig or pet faeces | erm(B | [4] | |

| P. pentosaceus | ||||

| 15 strains | Traditional fermented foods and curd | erm(B), msr(C) | [20] | |

| S. agalactiae | ||||

| 10 | Pork | erm(B), msr(A/B) | [22] | |

| S. sanguinis | ||||

| 18 | Pork | erm(B), msr(A/B) | [22] | |

| Lc. Lactis | ||||

| 17 strains | Dairy product | erm(B) | Plasmid | [46] |

| CWM2143, CWM286 | Bovine milk | erm(B) | [47] | |

| 3 Isolates | Poultry and pork meat | erm(B), erm(C) | [23] | |

| L. garvieae | ||||

| 20 Isolates | Poultry and pork meat | erm(B), erm(C) | [23] | |

| L. acidophilus NWL23 | Yogurt | erm(B) | [38] | |

| L. vaginalis NWL35 | Dairy | erm(B) | [38] | |

MLS macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin, NA Not available

In the recent time, a lot of attention has focused on enterococci as reservoirs and vehicles of AR as they readily develop resistance in response to antibiotic selective pressure [14]. Tylosin, lincomycin and neomycin are the prime antibiotics that are commonly used in animal husbandry [15]. Resistance to such antibiotics is observed in a large number of Enterococcus spp. carrying erm(B) and streptogramin A modifying enzyme, virginamycin acetyltransferase [vat(E)] genes isolated from US dairy cattle operations and commercial beef processing plant [16, 17]. Similarly, a recent work carried out by Zou et al. [15] on clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecalis (n = 78), erm(B) gene was the most common followed by erm(A), erm(C), macrolide efflux [mef(A/E)] and macrolide–streptogramin B resistant [msr(C)] efflux genes, displaying higher level of ERr.

MLS Resistant LAB from Animal Products

As LAB are natural inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tracts of many food animals, and present in high numbers, it is often unavoidable that these organisms enter the food chain [18]. This has been substantiated with the detection of resistance genes among Lactobacillus and Lactococcus spp. isolated from meat products such as fermented dry sausage [19–21], pork, poultry and beef samples [22, 23]. Further, macrolide resistance genes detected in specimens of chicken and pork meat was comparable to that of the faecal samples raising major concerns of raw meat and fermented foods as potential vehicles for antibiotic resistance dissemination [24].

Enterococci are commonly found in the intestine of farm animals and humans. In food microbiology, they have been—like E. coli—regarded as indicators of fecal contamination [3]. The high prevalence of multiple drug resistant (MDR) enterococci in farm animals and their meat is confirmed with the detection of Enterococcus isolates resistant to tetracycline, erythromycin and vancomycin from chicken samples [25]. Similar results were also obtained by others in Enterococcus species isolated from dairy cattle, poultry and animal meat [26–30] where most of the isolates resistant to erythromycin carried erm(B) gene (Table 1).

MLS Resistant LAB from Fermented Foods

Large numbers of LAB are consumed through fermented foods to maintain microbial balance in the intestines and for their beneficial attributes [5, 31]. Although Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc and Streptococcus spp. are sensitive to erythromycin, clindamycin and quinipristin/dalfopristin [32–34], resistance to these antibiotics was observed among LAB strains from cheese production environment [35] and commercial products [36–38]. Among the 473 isolates of LAB (Lactobacillus, Pediococcus and Lactococcus) analyzed by Klare et al. [39], majority of the isolates were susceptible to quinipristin/dalfopristin. However, 17 Lactobacillus isolates were resistant to one or more of the antibiotics and eight of them, including six probiotic cultures possessed erm(B) gene. This erm(B) gene was also detected among food isolates of L. paracasei, [40] and P. acidilactici isolated from traditional cheese and wine [41, 42]. In the study of Kastner et al. [43], L. reuteri SD 2112 was found to harbor lincosamide resistance gene, lincomycin nucleotidyltransferase [lnu(A)] and the same gene was found on two plasmids from a commercial strain of L. reuteri ATCC 55730 [44]. Of the several probiotic LAB of Africa and European origin, L. reuteri strain LY:12002 [45] and Lc. lactis strains from an Italian dairy product, bovine milk and meat products, high level of macrolide resistance was observed and erm(B) gene was found to be the resistance determinant [23, 46, 47].

Regarding the prevalence of AR in enterococcal strains from different environments, the frequency of MLS resistance was much lower in food isolates in comparison to clinical strains [37, 48] where Vankerkhoven et al. [49], could detect erm(B) only in one strain among the 128 E. faecium isolates. However, the studies carried out on the Moroccan food isolates [50] and probiotic strains [51] showed a high frequency of macrolide resistance in E. faecium and E. faecalis that harbored erm(B) and msr(C) genes. Such reports were also made in Enterococcus species (n = 150) isolated from raw milk cheese [52] and in our recent studies on naturally fermented foods (idli and dosa batter) and commercial dairy products [20] documenting the presence of erm(B), erm(C), msr(A/B), msr(C) and macrolide phosphotransferase (mph) encoding genes.

These observations raise the question of AR among desired food-borne bacteria with the food chain being the main route of transmission of AR bacteria between the animal and human populations [4, 41]. More specifically, fermented dairy products and fermented meats that are not heat-treated prior to consumption provide a vehicle for AR bacteria with a direct link between the animal’s indigenous flora and the human gastrointestinal tract [53].

Transfer of Conjugative Plasmids and Transposons Associated MLS Resistance

The abuse of antibiotics, a major cause of accumulation and dissemination of AR is now complicated by LAB that may act as reservoirs and transfer such resistance to pathogens [54]. The prerequisites for AR transfer from LAB to other bacteria are conjugative plasmids and transposons [53]. Lc. lactis was the first LAB in which conjugative plasmids were discovered [4]. R-plasmids encoding resistance to MLS antibiotics have been reported in Lactobacillus and Enterococcus species isolated from raw meat, silage and faeces [53, 55]. Resistance to MLS antibiotics has also been reported to be encoded by certain well characterized plasmids such as pAMb1 and RE25 where the latter encodes resistance to five macrolides and two lincosamides [4]. Using molecular techniques, erm(B), erm(C) and erm(T) genes, localized on plasmids, were detected in P. acidilactici, L. reuteri,L. plantarum and L. acidophilus [13, 43].

Conjugative transposons are the main type of vehicle for antibiotic resistance transfer and have been discovered in LAB such as E. faecalis (Tn916, Tn920, Tn925, Tn2702), E. faecium (Tn5233), Streptococcus pyogenes (Tn3701), Streptococcus agalactiae (Tn93951) and Lc. lactis (Tn5276 and Tn5301) that determine resistance to erythromycin along with chloramphenicol, tetracycline and kanamycin [53]. Due to association of macrolide resistance with conjugative plasmid and transposons, they are often found linked with other antibiotic resistance genes such as tetracycline and are also detected in LAB (11, 39, 40, 46, 51). Additionally, a recent study carried out by Vignaroli et al. [30] described the linkage of erm(B) with tetracycline [tet(M) and tet(O)], vancomycin (vanA), aminoglycoside (aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia) and ampicillin (blaZ) resistance genes in enterococcal isolates that could be co-transferred to the recipient through conjugation.

Among the three mechanisms (transformation, transduction and conjugation) of antibiotic resistance transfer, the impact of conjugation is significant on the global spread of antibiotic resistance mediated through conjugative plasmids and transposons [56]. Although there are few reports on conjugative transfer of MLS resistance from LAB, successful transfer of macrolide resistance from food LAB to pathogens and intra-and inter-generic LAB has been demonstrated. As depicted in Table 2, several workers have reported the role of LAB in the transfer of macrolide resistance to other bacteria under in-vitro conditions [18, 21, 38]. These studies are now extended to animal and plant models also to understand their prospective role in dissemination of resistance genes under natural conditions [54, 57–59]. Considering the evidences such as the prevalence of resistance genes and their potential to act as donor and recipient, it can be suggested that LAB act as reservoirs of MLS resistance genes that can be disseminated to pathogens. This present situation of food-grade LAB pose a threat to a variety of antibiotics especially the MLS, that have a proven record of excellence to cure illness and that are still currently used in human and veterinary medicine [20].

Table 2.

Conjugal transfer of MLS resistance from LAB

| Donor | Recipient | Conjugal mating method | Transfer frequency | Mode of transmission | MLS resistance gene transferred | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. reuteri L4:12002 | E. faecalis JH2-2 | In vitro | erm(B) | [45] | ||

| L. plantarum pLFE1 | E. faecalis | In vitro | 5.7 × 10−8 | erm(B) | [57] | |

| 3 × 10−9 | erm(B) | |||||

| L. plantarum DG 507 | E. faecalis | In vitro | 3.3 × 10−7 | Plasmid | erm(B) | [21] |

| L. plantarum DG 522 | E. faecalis | In vitro | 1 × 10−3 | Plasmid | erm(B) | [54] |

| E. faecalis | E. faecalis | Sausage | 10−6 | pAMβ-1 Plasmid | erm(B) | [58] |

| P. acidilactici UC 8840 | Sausage | 10−4 | pAMβ-1 Plasmid | erm(B) | ||

| S. vitulinus UC 8837 | Sausage | 10−3 | pAMβ-1 Plasmid | erm(B) | ||

| L. fermentum NWL24 | E. faecalis 181 | 2.6 × 10−5 | erm(B) | [38] | ||

| L. lactis SH4174 | L. lactis BU2-60 | In vitro | 2.6 × 10−2 | pAMβ-1 Plasmid | erm(B) | [56] |

| Animal rumen model | 3.3 × 10−8 | pAMβ-1 Plasmid | erm(B) | |||

| Plant model | 3.9 × 10−1 | pAMβ-1 Plasmid | erm(B) | |||

| S. thermophilus | E. faecalis JH2-2 | In vitro | 4.1 × 10−4 | Plasmid | erm(B) | [56] |

| Animal rumen model | 4 × 10−8 | Plasmid | erm(B) | |||

| L. salivarius NWL33 | E. faecalis 181 | In vitro | 2.9 × 10−6 | erm(B) | [38] | |

| E. faecalis CM5 V | E. faecalis OG1RF | In vitro | 3 × 10−8 | Plasmid | erm(B) | [30] |

| E. faecalis CM6 V | E. faecalis OG1RF | In vitro | 1 × 10−8 | Plasmid | erm(B) | [30] |

| E. durans PF1 V | E. faecalis 64/3 | In vitro | 1 × 10−7 | Plasmid | erm(B) | [30] |

| E. durans PF3 V | E. faecalis OG1RF | In vitro | 7 × 10−8 | Plasmid | erm(B) | [30] |

| E. faecalis 64/3 | In vitro | 3 × 10−6 | Plasmid | erm(B) | ||

| E. faecalis LMG20790 | E. faecalis JH2-2 | In vitro | Tn916-Tn1545 | erm(B) | [18] | |

| E. faecalis LMG20927 | E. faecalis JH2-2 | In vitro | Plasmid/Tn916-Tn1545 | erm(B) | [18] | |

| Lc. lactis SH4174 | Listeria monocytogenes (H7) | In vitro | 5.1 × 10−4 | pAMβ-1 Plasmid | erm(B) | [59] |

| S. thermophilus | Listeria monocytogenes (H7) | In vitro | 3.1 × 10−6 | Plasmid | erm(B) | [59] |

Conclusions

Besides the beneficial properties of LAB as starters or probiotics, there is a great concern that these bacteria may serve as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. This concern is strengthened due to the increasing number of strains displaying atypical resistance to antibiotics especially erythromycin and tetracycline. Macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin and its successors were introduced to contend with the problem of methicillin resistance. Although MLS antibiotics are not used for animal therapeutic purposes, the exploitation of the macrolide tylosin in animals has resulted in cross resistance to these antibiotics. All these facts persuade undoubtedly that resistance is selected in man and animals by the use of antibiotics in organisms that are part of the normal flora. Because of their broad environmental distribution, LAB may function as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes that can be disseminated via the food chain or within the GIT to other bacteria including pathogens. For the food microbiologists, it is essential to avoid the distribution of bacteria with mobilizable antibiotic resistance. Therefore, strains intended to be used in feed and food systems should be systematically monitored for resistance in order to avoid their inclusion as starters and probiotics. Above all, the biosafety of the probiotic LAB for human consumption must be assessed by proposing criteria, standards, guidelines and regulations.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to the Director-CFTRI and Head, FM for encouraging and supporting the research work on antibiotic resistance in lactic acid bacteria. SCR is thankful and acknowledges ICMR, New Delhi for senior research fellowship grant.

References

- 1.Leroy F, Vuyst L. Lactic acid bacteria as functional starter cultures for the food fermentation industry. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2004;15:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2003.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr FJ, Chill D, Maida N. The lactic acid bacteria: a literature survey. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2002;28:281–370. doi: 10.1080/1040-840291046759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teuber M, Meile L, Schwarz F. Acquired antibiotic resistance in lactic acid bacteria from food. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:115–137. doi: 10.1023/A:1002035622988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ammor MS, Florez AB, Mayo B. Antibiotic resistance in non-enterococcal lactic acid bacteria and Bifidobacteria. Food Microbiol. 2007;24:559–570. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.EFSA Opinion of the scientific panel on additives and products or substances used in animal feed on the updating of the criteria used in the assessment of bacteria for resistance to antibiotics of human and veterinary importance. EFSA J. 2005;223:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.EFSA Opinion of the Scientific Committee on a request from EFSA on the introduction of a qualified presumption of safety (QPS) approach for assessment of selected microorganisms referred to EFSA. EFSA J. 2007;187:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wassenaar T. Use of antimicrobial agents in veterinary medicine and implications for human health. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2005;31:155–169. doi: 10.1080/10408410591005110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EFSA Technical guidance—update of the criteria used in the assessment of bacterial resistance to antibiotics of human or veterinary importance—prepared by the panel on additives and products or substances used in animal feed. EFSA J. 2008;732:1–15. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2008.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts M, Sutcliffe J, Courvalin P, Jensen LB, Rood J, Seppala H. Nomenclature for macrolide and macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin B resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2823–2830. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisblum B. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:577–585. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts MC. Update on macrolide–licosamide–streptogramin, ketolide, and oxazolidinone resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;282:147–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurd HS, Doores S, Hayes D, Matthew A, Maurer J, Silley P, Singer RS, Jones RN. Public health consequences of macrolide use in food animals: a deterministic risk assessment. J Food Prot. 2004;67:980–992. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-67.5.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egervarn M, Roos S, Lindmark H. Identification and characterization of antibiotic resistance genes in Lactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus plantarum. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:1658–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilcks A, Andersen SR, Licht TR. Characterization of transferable tetracycline resistance genes in Enterococcus faecalis isolated from raw food. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;243:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou L, Wang H, Zeng B, Li J, Li X, Zhang A, Zhou Y, Yang X, Xu C, Xia Q. Erythromycin resistance and virulence genes in Enterococcus faecalis from swine in China. New Microbiol. 2011;34:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson CR, Lombard JE, Dargatz DA, Fedorka-cray PJ. Prevalence, species distribution and antimicrobial resistance of enterococci isolated from US dairy cattle. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;52:41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aslam M, Diarra MS, Service C, Rempel H. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Enterococcus spp. recovered from a commercial beef processing plant. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010;7:235–241. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huys G, D’Haene K, Collard J, Swings J. Prevalence and molecular characterization of tetracycline resistance in Enterococcus isolates from food. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1555–1562. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1555-1562.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zonenschain D, Rebecchi A, Morelli L. Erythromycin- and tetracycline-resistant lactobacilli in Italian fermented dry sausages. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:1559–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thumu SCR, Halami PM (2012) Presence of erythromycin and tetracycline resistance genes in lactic acid bacteria from fermented foods of Indian origin. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. doi:10.1007/s10482-012-9749-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Gevers D, Masco L, Baert L, Huys G, Debevere J, Swings J. Prevalence and diversity of tetracycline resistant lactic acid bacteria and their tet genes along the process line of fermented dry sausages. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2003;26:277–283. doi: 10.1078/072320203322346137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toomey N, Bolton D, Fanning S. Characterization and transferability of antibiotic resistance genes from lactic acid bacteria isolated from Irish pork and beef abattoirs. Res Microbiol. 2010;161:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aquilanti L, Garofalo C, Osimani A, Silvestri G, Vignaroli C, Clementi F. Isolation and molecular characterization of antibiotic-resistant lactic acid bacteria isolated from poultry and swine meat products. J Food Prot. 2007;70:557–565. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garofalo C, Vignaroli C, Zandri G, Aquilanti L, Bordoni D, Osimani A, Clementi F, Biavasco F. Direct detection of antibiotic resistance genes in specimens of chicken and pork meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;113:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giraffa G. Enterococci from foods. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26:163–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbosa J, Ferreiram V, Teixeira P. Antibiotic susceptibility of enterococci isolated from traditional fermented meat products. Food Microbiol. 2009;26:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mannu L, Paba A, Daga E, Comunian R, Zanetti S, Dupre I, Sechi LA. Comparison of the incidence of virulence determinants and antibiotic resistance between Enterococcus faecium strains of dairy, animal and clinical origin. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003;88:291–304. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters J, Mac K, Wichmann-Schauer H, Klein G, Ellerbroek L. Species distribution and antibiotic resistance patterns of enterococci isolated from food of animal origin in Germany. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003;88:311–314. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bekele B, Ashenafi M. Distribution of drug resistance among enterococci and Salmonella from poultry and cattle in Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2010;42:857–864. doi: 10.1007/s11250-009-9499-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vignaroli C, Zandri G, Aquilanti L, Pasquaroli S, Biavasco F. Multidrug-resistant enterococci in animal meat and faeces and co-transfer of resistance from an Enterococcus durans to a human Enterococcus faecium. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:1438–1447. doi: 10.1007/s00284-011-9880-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saylers AA, Gupta A, Wang Y. Human intestinal bacteria as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Aimmo MR, Modesto M, Biavati B. Antibiotic resistance of lactic acid bacteria and Bifidobacterium spp. isolated from dairy and pharmaceutical products. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;115:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katla AK, Kruse H, Johnsen G, Heikstad H. Antimicrobial susceptibility of starter culture bacteria used in Norwegian dairy products. Int J Food Microbiol. 2001;67:147–152. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00522-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pulido RP, Omar NB, Lucas R, Abriouel H, Canamero MM, Galvez A. Resistance to antimicrobial agents in lactobacilli isolated from caper fermentations. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2005;88:277–281. doi: 10.1007/s10482-005-6964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florez AB, Delgado S, Mayo B. Antimicrobial susceptibility of lactic acid bacteria isolated from a cheese environment. Can J Microbiol. 2005;51:51–58. doi: 10.1139/w04-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egervarn M, Danielsen M, Roos S, Lindmark H, Lindgren S. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Lactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus fermentum. J Food Prot. 2007;70:412–418. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.2.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blandino G, Milazzo I, Fazio D. Antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial isolates from probiotic products available in Italy. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2008;20:199–203. doi: 10.1080/08910600802408111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nawaz M, Wang J, Zhou A, Ma C, Wu X, Moore JE, Miller BC, Xu J. Characterization and transfer of antibiotic resistance in lactic acid bacteria from fermented food products. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:1081–1089. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klare I, Konstable C, Werner G, Huys G, Vankerckhoven V, Kahlmeter G, Hilderbrandt B, Muller-Bertling S, Witte W, Goossens H. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus and Lactococcus human isolates and cultures intended to probiotic or nutritional use. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:900–912. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huys G, D’Haene K, Danielsen M, Matoo J, Egervarn M, Vandamme P. Phenotypic and molecular assessment of antimicrobial resistance in Lactobacillusparacasei strains of food origin. J Food Prot. 2008;71:339–344. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danielsen M, Simpson PJ, O’Connor EB, Ross RP, Stanton C. Susceptibility of Pediococcus spp. to antimicrobial agents. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;102:384–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rojo-Bezares B, Saenz Y, Poeta P, Zarazaga M, Ruiz-Lerrea F, Torres C. Assessment of antibiotic susceptibility within lactic acid bacteria from wine. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006;111:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kastner S, Perreten V, Bleuler H, Hugenschmidt G, Lacroix C, Meile L. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns and resistance genes of starter cultures and probiotic bacteria used in food. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2006;29:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosander A, Connolly E, Roos S. Removal of antibiotic resistance gene-carrying plasmids from Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 and characterization of the resulting daughter strain, L. reuteri DSM 17938. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6032–6040. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00991-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ouba LII, Lei V, Jensen LB. Resistance of potential lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria of African and European origin to antimicrobials: determination and transferability of the resistance genes to other bacteria. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;121:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devirgiliis C, Barile S, Caravelli A, Coppala D, Perozzi G. Identification of tetracycline-and erythromycin-resistant Gram-positive cocci within the fermenting microflora of an Italian dairy product. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walther C, Rossano A, Thomann A, Perreten V. Antibiotic resistance in Lactococcus species from bovine milk: presence of a mutated multidrug transporter mdt(A) gene in susceptible Lactococcus garvieae strains. Vet Microbiol. 2008;131:348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abriouel H, Omar NB, Molinos AC, Lopez RL, Grande MJ, Martinez-Viedma P, Ortega E, Canamero MM, Galvez A. Comparative analysis of genetic diversity and incidence of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance among enterococcal populations from raw fruit and vegetable foods, water and soil, and clinical samples. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;123:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vankerckhoven V, Huys G, Vancanneyt M, Snauwaert C, Swings J, Klare I, Witte W, Autgaerden T, Chapelle S, Lammens C, Gossens H. Genotypic diversity, antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors of human isolates and probiotic cultures constituting two intraspecific groups of Enterococcus faecium isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4247–4255. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02474-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valenzuela AS, Omar NB, Abriouel H, Lopez RL, Ortega E, Canamero MM, Galvez A. Risk factors in enterococci isolated from foods in Morocco: determination of antimicrobial resistance and incidence of virulence traits. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:2648–2652. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hummel AS, Hertel C, Holpzapfel WH, Franz CM. Antibiotic resistances of starter and probiotic strains of lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:730–739. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02105-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Templer SP, Baumgartner A. Enterococci from appenzeller and Schabziger raw milk cheese: antibiotic resistance, virulence factors and persistence of particular strains in the products. J Food Prot. 2007;70:450–455. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.2.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathur S, Singh R. Antibiotic resistance in food lactic acid bacteria—a review. Int J Food Microbiol. 2005;105:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacobsen L, Wilcks A, Hammer K, Huys G, Gevers D, Andersen SR. Horizontal gene transfer of tet(M) and erm(B) resistant plasmids from food strains of Lactobacillus plantarum to Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2 in the gastrointestinal tract of gnotobiotic rats. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;59:158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwarz FV, Perreten V, Teuber M. Sequence of the 50-kb conjugative multiresistance plasmid pRE25 from Enterococcus faecalis RE25. Plasmid. 2001;46:170–187. doi: 10.1006/plas.2001.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toomey N, Monaghan A, Fanning S, Bolton D. Transfer of antibiotic resistance marker genes between lactic acid bacteria in model rumen and plant environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:3146–3152. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02471-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feld L, Schjorring S, Hammer K, Licht TR, Danielsen M, Krogfelt K, Wilcks A. Selective pressure affects transfer and establishment of a Lactobacillus plantarum resistance plasmid in the gastrointestinal environment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:845–852. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gazzola S, Fontana C, Bassi D, Cocconcelli PS. Assessment of tetracycline and erythromycin resistance transfer during sausage fermentation by culture-dependant and independent methods. Food Microbiol. 2012;30:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toomey N, Monaghan A, Fanning S, Bolton J. Assessment of antimicrobial resistance transfer between lactic acid bacteria and potential foodborne pathogens using in vitro methods and mating in a food matrix. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2009;6:925–933. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]