Abstract

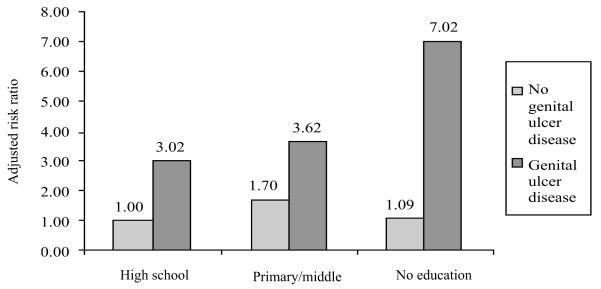

Systematic disparities in rates of HIV incidence by socioeconomic status were assessed among men attending three sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics in Pune, India, to identify key policy-intervention points to increase health equity. Measures of socioeconomic status included level of education, family income, and occupation. From 1993 to 2000, 2,260 HIV-uninfected men who consented to participate in the study were followed on a quarterly basis. Proportional hazards regression analysis of incident HIV infection identified a statistically significant interaction between level of education and genital ulcer disease. Compared to the lowest-risk men without genital ulcer disease who completed high school, the relative risk (RR) for acquisition of HIV was 7.02 (p<0.001) for illiterate men with genital ulcer disease, 3.62 (p<0.001) for men with some education and genital ulcer disease, and 3.02 (p<0.001) for men who completed high school and had genital ulcer disease. For men with no genital ulcer disease and those with no education RR was 1.09 (p=0.84), and for men with primary/middle school it was 1.70 (p=0.03). The study provides evidence that by enhancing access to treatment and interventions that include counselling, education, and provision of condoms for prevention of STDs, especially genital ulcer disease, among disadvantaged men, the disparity in rates of HIV incidence could be lessened considerably. Nevertheless, given the same level of knowledge on AIDS, the same level of risk behaviour, and the same level of biological co-factors, the most disadvantaged men still have higher rates of HIV incidence.

Keywords: Health equity, HIV, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, Sexually transmitted infections, Sexually transmitted diseases, Socioeconomic status, Prospective studies, India

INTRODUCTION

The Government of India estimates that 3.97 million Indians were infected with HIV in 2001, the majority through heterosexual transmission (1). The estimated prevalence rates varied by geographic region, with the highest rates in the more-developed southern states. There is a paucity of evidence on differential rates of HIV/AIDS by socioeconomic status within India, and the mechanisms through which disparities in rates of infection might be produced (2,3). While cross-national studies have shown that both absolute poverty and relative poverty are associated at the national level with higher rates of HIV infection (4,5), several African studies observed higher rates among more educated and higher-salaried individuals (6,7).

One of the states most affected by the epidemic of HIV has been the western Indian state of Maharashtra, where the epidemic has been characterized by heterosexual transmission with high prevalence rates among sex workers (8). Maharashtra is one of the few Indian states that has undergone rapid economic growth and industrial development during the 1990s (9). Pune is a dynamic city with a population of 2.54 million, which has increased by 63% over the past decade due largely to in-migration, making it the eighth largest urban agglomeration in India in 2001 (10). The city has a growing number of people residing in slum areas, with estimates ranging from 21% to 40% of the population (10,11). This urbanizing population, with a large and growing vulnerable segment of young migrants, creates the conditions under which epidemics of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) can flourish.

An inequality, or disparity, in health is simply a difference, with no normative significance, inequity, on the other hand, is a difference that is deemed to be unfair; a concept based on the ethical principle of distributive justice and is closely linked to principles of human rights (12). The International Society for Equity in Health has defined inequity as “systematic and potentially remediable differences in one or more aspect(s) of health across populations or population groups defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically” (13). Studies of health equity attempt to answer three related questions: first, where is there a health difference; second, is that difference avoidable; and third, is the difference unjust.

A prior study in this population of STD clinic clients in Pune, India, identified inequity in prevalence of HIV by gender (14). Monogamous married women had an HIV-prevalence rate of 14%, yet their only identifiable risk behaviour was sexual contact with their spouse. In the present study, we will explore systematic disparities in rates of HIV incidence among men by socioeconomic status, as measured by level of education, family income, and occupation (15). The focus on men is important because of the pivotal role they play in the epidemic of HIV/AIDS and in reproductive health more generally (16).

The present study was carried out to assess whether those at the lower end of the social stratification system were more likely to acquire HIV infection, and if so, to identify mediating factors in the behavioural, biological and social pathways between the incidence of HIV and low social status. We investigated which risk factors or risk behaviours disproportionately led to infection among the most poor and least-educated study participants. This approach will provide insight on which interventions are most likely to enhance equity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site and population

The study, a collaboration between the National AIDS Research Institute in Pune, India and the Johns Hopkins University, was carried out in three public outpatient STD clinics in Pune. One clinic is located within a municipal medical clinic in a busy market area, another is located in a large public referral hospital, and the third is a freestanding clinic in the ‘red light’ district specifically serving sex workers, their children, and their clients. During 13 May 1993-19 January 2000, patients attending these three STD clinics were offered serologic screening for HIV infection. Individuals who consented to testing for HIV and were HIV-seronegative were offered enrollment in a cohort study of risk factors for incident HIV infection and asked to return for quarterly follow-up visits.

Follow-up visits occurred during 14 August 1993-28 April 2000. Study procedures, the incidence rates, and risk factors for HIV seroconversion for this cohort have been previously reported (17). All HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals were provided intensive risk-reduction pre-test and post-test counselling at each visit which focused on reinforcing messages of monogamy, use of condoms with sexual partners, efficacious use of condoms through demonstration, and provision of government-provided condoms free of charge. Following informed consent, participants were administered a structured questionnaire on demographics, STD and medical history, sexual behaviour, risk practices, and knowledge of HIV/AIDS. Knowledge questions ranged from whether they had ever heard of AIDS to questions about specific transmission and prevention factors. At screening and follow-up visits, the participants were given a detailed physical examination, and specimens were collected for laboratory examination. Patients were treated with standard therapy for STDs based on clinical impression, using the guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (18).

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Indian Council of Medical Research and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Laboratory tests

Serum samples were screened with a commercially-available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (EIA) kit for identification of HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies (Recombigen HIV-1/HIV-1-2, Cambridge Biotech, Galway, Ireland). Specimens testing positive by EIA were confirmed with a rapid test for HIV-1 and HIV-2 (Recombigen HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid Test Device, Cambridge Biotech). Specimens with discrepant EIA results were confirmed with a third different EIA or Western blot assay (Cambridge Biotech). Western blot assays were interpreted according to the criteria of CDC (19). HIV seroconverters were those HIV-uninfected at screening who became HIV-infected during the course of follow-up. The date of HIV seroconversion was estimated as the midpoint between the last HIV antibody-negative date and the first HIV antibody-positive date.

Statistical analysis

The association between level of education and other demographics, knowledge on AIDS, behavioural and clinical factors was assessed using chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Rates of HIV incidence were calculated as the ratio of the number of seroconversions divided by the number of person-years of follow-up, with confidence intervals based on a Poisson-distributed variable (20). Unadjusted risk ratios and confidence intervals were calculated using STATA 7.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas). Kaplan-Meier curves of risk of HIV seroconversion were produced by various risk factors, stratified by level of education and tested by the log-rank test.

Factors independently associated with the risk of HIV seroconversion were identified through a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with both time-invariant and time-dependent covariates. Variables were entered into multivariate proportional hazards models in four groups, corresponding to (i) social position, (ii) knowledge on HIV/AIDS, (iii) exposure risks, and (iv) susceptibility factors. Within each group, variables independently associated with acquisition of HIV were identified, then those variables were added to the overall model to assess their effect upon the social factors. Thus, mediating factors between the incidence of HIV and socioeconomic status were identified by conditioning the analysis on these various sociodemographics, knowledge on AIDS, behavioural and clinical risk factors. Moderating effects between HIV and socioeconomic status were assessed by modelling the interactions between level of education and the statistically significant risk factors (21). Through this process, intervention points were identified which, if mitigated, would reduce inequity in risk of acquisition of HIV.

RESULTS

Attendees of clinics were screened for HIV infection at their initial visit, and 1,878 (19.8%) of 9,511 men were found to be HIV-seropositive. Of 7,633 HIV-seronegative men, 2,260 consented to participate in the cohort study and return for follow-up on a quarterly basis. Previous analyses have shown that those who consented to enroll in the prospective study tended to have a lower baseline risk-behaviour profile than those who refused to participate (22), also a greater proportion had heard of AIDS (70% vs 64%) and completed high school (51% vs 39%). The median follow-up time for the study participants was 12 months (interquartile range: 4.5-25.2 months), and they attended the clinic a median of 3 times (interquartile range: 2-5), accumulating 3,249.5 person-years of exposure by April 2000.

The majority (50.6%) of men enrolled in the prospective study had at least a high school education, 39.9% had a primary or middle school education, and 9.4% were illiterate with no formal education. The median age of the men was 25 years (range: 18-70 years). As shown in Table 1, the most commonly-reported occupations were unskilled labour (30%), skilled labour (15%), or local autorickshaw and taxi drivers (7%). Of those with data on monthly family income per family member, 31% fell below Rs 300, 37% were in the interval Rs 300-549, and 32% of the men’s families earned Rs 550 and above per family member. Fifty-six percent of the men were unmarried, 42% were married, 2.4% were widowed, divorced, or separated, and 78% were residing with their family. The participants were mostly of the Hindu religion (82%), while Buddhists and neo-Buddhists comprised 11%, and Muslims 5% of the cohort. Marathi was the predominant mother tongue (82%), although 9% reported Hindi and 10% a variety of other Indian languages. As expected, most of these sociodemographic characteristics were significantly associated with level of education, with the exception of residing with family, and religion. Illiterate men, tended to be older, were more frequently employed, were more often working as unskilled labourers or cook/waiters, having a lower monthly family income, were more likely to be married, and were less often native Marathi speakers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of male clients of STD clinics enrolled in the prospective study by level of education, Pune, India, May 1993-April 2000

| Level of education |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total (n=2,260)* |

None (n=213) |

Primary/middle school (n=901) |

High school or more (n=1142) |

p value | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age group (years) | |||||||||

| <20 | 281 | 12.4 | 19 | 8.9 | 115 | 12.8 | 147 | 12.9 | |

| 20-24 | 789 | 34.9 | 46 | 21.6 | 287 | 31.9 | 454 | 39. | |

| 25-29 | 510 | 22.6 | 45 | 21.1 | 178 | 19.8 | 287 | 25. | |

| 30+ | 678 | 30 | 103 | 48.4 | 321 | 35.6 | 254 | 22.2 | <0.001 |

| Employed | |||||||||

| Yes | 1929 | 85.6 | 208 | 97.6 | 827 | 92 | 893 | 78.3 | |

| No | 325 | 14.4 | 5 | 2.4 | 72 | 8 | 247 | 21.7 | <0.001 |

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Unskilled labour | 679 | 30 | 99 | 46.5 | 331 | 36.7 | 248 | 21.7 | |

| Skilled labour | 338 | 15 | 22 | 10.3 | 118 | 13.1 | 198 | 17.3 | |

| Local driver | 157 | 7 | 9 | 4.2 | 83 | 9.2 | 65 | 5.7 | |

| Cook/waiter | 139 | 6.2 | 24 | 11.3 | 72 | 8 | 43 | 3.8 | |

| Student | 134 | 5.9 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.4 | 128 | 11.2 | |

| Other | 813 | 35.9 | 58 | 27.2 | 293 | 32.5 | 460 | 40.3 | <0.001 |

| Family income (Rs) per member |

|||||||||

| <300 | 577 | 25.5 | 65 | 30.5 | 277 | 30.7 | 235 | 20.6 | |

| 300-549 | 698 | 30.9 | 78 | 36.6 | 238 | 26.4 | 381 | 33. | |

| ≥550 | 605 | 26.8 | 38 | 17.8 | 168 | 18.7 | 398 | 34.9 | |

| Data not collected** | 380 | 16.8 | 32 | 15 | 218 | 24.2 | 128 | 11.2 | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Never-married | 1262 | 55.8 | 68 | 31.9 | 434 | 48.2 | 757 | 66.3 | |

| Married | 945 | 41.8 | 138 | 64.8 | 432 | 47.9 | 374 | 32.8 | |

| Formerly married† | 53 | 2.4 | 7 | 3.3 | 35 | 3.9 | 11 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Living with family | |||||||||

| Yes | 1749 | 77.6 | 164 | 77.4 | 704 | 78.1 | 880 | 77.2 | |

| No | 506 | 22.4 | 48 | 22.6 | 197 | 21.9 | 260 | 22.8 | 0.88 |

| Religion | |||||||||

| Hindu | 1842 | 81.6 | 172 | 80.8 | 722 | 80.1 | 946 | 82.8 | |

| Muslim | 118 | 5.2 | 13 | 6.1 | 60 | 6.7 | 45 | 3.9 | |

| Buddhist | 242 | 10.7 | 25 | 11.7 | 100 | 11.1 | 117 | 10.3 | |

| Other | 56 | 2.5 | 3 | 1.4 | 19 | 2.1 | 34 | 3 | 0.08 |

| Mother tongue | |||||||||

| Marathi | 1843 | 81.6 | 152 | 71.4 | 719 | 79.8 | 970 | 84.9 | |

| Hindi | 200 | 8.9 | 28 | 13.2 | 85 | 9.4 | 87 | 7.6 | |

| Other | 217 | 9.6 | 33 | 15.5 | 97 | 10.8 | 85 | 7.4 | <0.001 |

Of 2,260 individuals in the analysis, 4 were missing data on level of education and 5 were missing ‘living with family’

Data not collected due to change in study instruments in March 1998 (question discontinued)

Formerly married status included individuals who were separated from their spouse, divorced, or widowed

Rates of HIV-1 incidence were calculated by various sociodemographic factors (Table 2). The rate of HIV-1 incidence among this cohort of men was 5.1 per 100 person-years of exposure. Assessment of the incidence rates by age revealed that the youngest men had the highest rates of HIV acquisition. Those aged less than 20 years had a high rate of 9.6/100 person-years compared to 4.4/100 person-years for those aged 20-24 years, 5.5/100 person-years for those aged 25-29 years, and 4.8/100 person-years for those aged 30 years and older. The incidence was inversely related to level of education: 3.5/100 person-years for those with at least secondary school education, 6.1/100 person-years for those with only primary or middle school, and 10.5/100 person-years for those with no formal education. Employed men had higher rates of infection (5.6/100 person-years) than unemployed men (2.6/100 person-years). The highest rates of HIV incidence by occupation were observed among hotel boys (18.3/100 person-years, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.0-46.8, n=19), long-distance drivers (12.0/100 person-years, 95% CI 2.5-34.9, n=23), cooks/waiters (9.2/100 person-years, 95% CI 5.4-14.7, n=139), and farmers (9.1/100 person-years, 95% CI 3.9-17.9, n=70) (data not shown). The lowest rates of incidence were among students (0.8/100 person-year, 95% CI 0.1-3.1, n=134), local drivers (2.8/100 person-years, 95% CI 1.0-6.1, n=157), clerical workers (1.3/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.03-7.2, n=55), business/salesmen (2.8/100 person-years, 95% CI 1.1-5.8, n=170).

Table 2.

Rates of incident HIV-1 infection among male attendees of STD clinics by sociodemographic characteristics, Pune, India, May 1993-April 2000

| Characteristics | HIV-1 seroconversion |

Person-year* | HIV-1 incidence rate (95% CI) |

Unadjusted risk ratio (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 165 | 3249.5 | 5.1 (4.4-5.9) | ||

| Age group (years) | |||||

| <20 | 15 | 155.6 | 9.6 (5.4-15.9) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| 20-24 | 45 | 1029.4 | 4.4 (3.2-5.9) | 0.45 (0.25-0.88) | 0.01 |

| 25-29 | 50 | 906.1 | 5.5 (4.1-7.3) | 0.57 (0.32-1.10) | 0.07 |

| 30+ | 57 | 1180.3 | 4.8 (3.7-6.3) | 0.50 (0.28-0.95) | 0.03 |

| Education | |||||

| High school+ | 60 | 1730.1 | 3.5 (2.7-4.5) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Primary/middle school | 77 | 1253.6 | 6.1 (4.9-7.7) | 1.77 (1.25-2.53) | <0.001 |

| None | 30 | 286 | 10.5 (7.1-15.0) | 3.02 (1.88-4.76) | <0.001 |

| Employed | |||||

| No | 13 | 507.2 | 2.6 (1.4-4.4) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 152 | 2734.7 | 5.6 (4.7-6.5) | 2.17 (1.23-4.17) | 0.003 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Unskilled labour | 57 | 899.4 | 6.3 (4.8-8.3) | 1.37 (0.92-2.02) | 0.10 |

| Skilled labour | 29 | 551 | 5.3 (3.5-7.6) | 1.13 (0.70-1.81) | 0.58 |

| Local driver | 6 | 215.2 | 2.8 (1.0-6.1) | 0.60 (0.21-1.40) | 0.23 |

| Cook/waiter | 17 | 184.6 | 9.2 (5.4-14.7) | 1.98 (1.08-3.48) | 0.02 |

| Student | 2 | 235.4 | 0.8 (0.1-3.1) | 0.18 (0.02-0.69) | 0.003 |

| Other | 54 | 1163.8 | 4.6 (3.5-6.1) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Family income (Rs) per member | |||||

| <300 | 49 | 1062.2 | 4.6 (3.4-6.1) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| 300-549 | 58 | 1069.7 | 5.4 (4.1-7.1) | 1.18 (0.79-1.86) | 0.41 |

| ≥550 | 49 | 830.9 | 5.9 (4.4-7.8) | 1.28 (0.84-1.94) | 0.23 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Never-married | 82 | 1705.7 | 4.8 (3.9-6.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Married | 78 | 1465.4 | 5.3 (4.2-6.7) | 1.11 (0.80-1.52) | 0.52 |

| Formerly married** | 7 | 100.3 | 7.0 (2.8-14.4) | 1.45 (0.57-3.13) | 0.35 |

| Living with family | |||||

| Yes | 119 | 2532.1 | 4.7 (3.9-5.6) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| No | 48 | 735.9 | 6.5 (4.8-8.7) | 1.39 (0.97-1.96) | 0.06 |

| Religion | |||||

| Hindu | 150 | 2652.7 | 5.7 (4.8-6.7) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Muslim | 0 | 157.7 | 0.0 (0.0-2.3) | 0.00 (0.00-0.42) | <0.001 |

| Buddhist | 12 | 352.4 | 3.4 (1.8-5.9) | 0.60 (0.30-1.08) | 0.08 |

| Other | 3 | 84.6 | 3.5 (0.7-10.4) | 0.63 (0.13-1.87) | 0.45 |

| Mother tongue | |||||

| Marathi | 130 | 2715.1 | 4.8 (4.0-5.7) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Hindi | 11 | 250.1 | 4.4 (2.2-7.9) | 0.92 (0.45-1.70) | 0.82 |

| Other | 24 | 284.2 | 8.4 (5.4-12.5) | 1.76 (1.09-2.74) | 0.02 |

Of 2,260 individuals in the analysis, 4 were missing data on level of education and 5 were missing ‘living with family’

Formerly married status included individuals who were separated from their spouse, divorced, or widowed

CI=Confidence interval

There were no differences in the incidence of HIV by level of family income, or by marital status. Those men residing away from their families had a rate of 6.5 vs 4.7 for those living with family (p=0.06). Compared to the vast majority of men in the cohort who were Hindus, men of other religions had lower rates of incidence: no seroconversions were detected among Muslim men (p<0.001) due perhaps to circumcision practices, and Buddhists and neo-Buddhists had a rate 40% lower than Hindus (p=0.08) as did the small number of men of other religions combined (p=0.45). The minority of men who had a mother tongue other than Marathi or Hindi had a higher rate of incident HIV infection (8.4/100 person-years).

Overall, 70% of men had heard of AIDS prior to enrollment (Table 3), varying by level of education. Forty-two percent of illiterate men, 61% of men with some education, and 83% of men with high school or more had prior awareness of AIDS (p<0.001). After pre- and post-test counselling sessions at their baseline visit, men returned for follow-up and were asked 14 questions about HIV/AIDS. Sixty percent of men scored 86% or better on AIDS knowledge at their first follow-up visit, answering at least 12 of the 14 questions correctly, which again varied by educational status. Only 33% of illiterate men had a correct understanding about AIDS compared to 50% of those with some education and 72% of those with high school or more (p<0.001).

Table 3.

AIDS knowledge, risk behaviours, and clinical characteristics of male clients of STD clinics, by level of education, Pune, India, May 1993-April 2000

| Level of education |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total (n=2,260)* |

None (n=213) |

Primary/middle school (n=901) |

High school or more (n=1,142) |

p value | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Prior awareness of AIDS | |||||||||

| Yes | 1,495 | 70.1 | 83 | 41.7 | 526 | 61.1 | 884 | 82.5 | |

| No | 638 | 29.9 | 116 | 58.3 | 335 | 38.9 | 187 | 17.5 | <0.001 |

| AIDS knowledge at 1st FU | |||||||||

| 86% or more correct | 1,060 | 60.1 | 53 | 32.7 | 319 | 49.7 | 685 | 71.6 | |

| <86% correct | 703 | 39.9 | 109 | 67.3 | 323 | 50.3 | 271 | 28.4 | <0.001 |

| Tattoo at 1st FU | |||||||||

| No | 2,202 | 98 | 203 | 96.2 | 877 | 98.1 | 1,118 | 98.2 | |

| Yes | 45 | 2 | 8 | 3.8 | 17 | 1.9 | 20 | 1.8 | 0.15 |

| Medical injection at 1st FU | |||||||||

| No | 1,615 | 71.8 | 148 | 69.8 | 640 | 71.7 | 824 | 72.3 | |

| Yes | 633 | 28.2 | 64 | 30.2 | 253 | 28.3 | 315 | 27.7 | 0.75 |

| Number of recent sexual partners at 1st FU |

|||||||||

| None | 1,514 | 67.1 | 129 | 60.9 | 550 | 61.3 | 832 | 72.9 | |

| One | 425 | 18.9 | 45 | 21.2 | 217 | 24.2 | 162 | 14.2 | |

| Two or more | 316 | 14 | 38 | 17.9 | 130 | 14.5 | 148 | 13 | <0.001 |

| CSW partner at 1st FU | |||||||||

| No | 1,733 | 77 | 146 | 69.2 | 676 | 75.4 | 907 | 79.6 | |

| Yes | 519 | 23 | 65 | 30.8 | 221 | 24.6 | 233 | 20.4 | 0.002 |

| Condoms used with CSW at 1st FU |

|||||||||

| Always | 175 | 33.9 | 11 | 16.9 | 64 | 29.2 | 100 | 42.9 | |

| Sometimes | 89 | 17.2 | 6 | 9.2 | 36 | 16.4 | 47 | 20.2 | |

| Never | 253 | 48.9 | 48 | 73.9 | 119 | 54.3 | 86 | 36.9 | <0.001 |

| Male partner ever | |||||||||

| No | 2,090 | 92.6 | 198 | 93 | 823 | 91.3 | 1067 | 93.4 | |

| Yes | 168 | 7.4 | 15 | 7 | 78 | 8.7 | 75 | 6.6 | 0.20 |

| Male partner at 1st FU | |||||||||

| No | 2,238 | 99 | 212 | 99.5 | 891 | 98.9 | 1131 | 99 | |

| Yes | 22 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 10 | 1.1 | 11 | 1 | 0.69 |

| Circumcision | |||||||||

| No | 2,072 | 91.7 | 195 | 91.6 | 816 | 90.6 | 1,058 | 92.6 | |

| Yes | 188 | 8.3 | 18 | 8.4 | 85 | 9.4 | 84 | 7.4 | 0.24 |

| Urethritis at 1st FU | |||||||||

| No | 2,124 | 94 | 190 | 89.2 | 837 | 92.9 | 1,093 | 95.7 | |

| Yes | 136 | 6 | 23 | 10.8 | 64 | 7.1 | 49 | 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Genital ulcer at 1st FU | |||||||||

| No | 1,583 | 86.7 | 129 | 74.6 | 557 | 84.1 | 895 | 90.6 | |

| Yes | 243 | 13.3 | 44 | 25.4 | 105 | 15.9 | 93 | 9.4 | <0.001 |

Of 2,260 individuals in the analysis, 13 had missing data on number of recent sexual partners at one of their follow-up visits, 26 were missing recent tattoo, 22 were missing recent medical injection, and 9 were missing genital ulcer on examination at one follow-up

FU=Follow-up visit

CSW=Commercial sex worker

Fourteen percent of men reported multiple recent sexual partners, and two-thirds reported no recent partners at their first follow-up visit. This result varied by educational level, with 72% of high school men reporting no partners compared to 61% of men with less than high school. Nearly one quarter of the men reported visiting sex workers in the past three months at their first follow-up visit with 31% of illiterate men, 25% of men with some education, and 20% of high school men having done so (p=0.002). Among those with recent sex worker partners, use of condoms was least likely among illiterate men: 74% never used condoms with sex workers in the three months prior to first follow-up visit compared to 54% of men with some education and 37% of men with high school or more education (p<0.001). Urethritis and genital ulceration were both detected more frequently at the first follow-up visit among those with less education: 11% of illiterates, 7% of those with some education, and 4.3% of those with high school education returned for their first follow-up visit with urethritis (p<0.001). Likewise, 25% of illiterates, 16% of those with some education, and 9% of those completing high school returned at the first follow-up visit with genital ulceration (p<0.001).

Table 4 displays rates of HIV incidence by level of AIDS knowledge, risk behaviours, and clinical findings. Men who had heard of AIDS before their first clinic visit had a lower rate of subsequent infection (4.1/100 person-years) than men who learned about AIDS at their first clinic visit (7.4/100 person-years). At follow-up, those demonstrating greater knowledge of AIDS transmission had a lower incidence rate (3.4/100 person-years) than those with less AIDS knowledge (11.1/100 person-years). Multiple sexual partners, having a sex worker partner, inconsistent or no use of condoms with sex workers were all associated with higher rates of incident HIV infection as were the detection of urethritis or genital ulceration upon clinical examination. Circumcised men had a significantly lower rate of HIV incidence (0.5/100 person-years) compared to the majority of men who were uncircumcised (5.4/100 person-years).

Table 4.

Rates of incident HIV-1 infection among male attendees of STD clinics by AIDS knowledge, risk behaviours, and clinical characteristics, Pune, India, May 1993-April 2000

| Characteristics | HIV-1 seroconversion |

Person-year* | HIV-1 incidence rate (95% CI) |

Unadjusted risk ratio (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior awareness of AIDS | |||||

| Yes | 88 | 2164.6 | 4.1 (3.3-5.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| No | 70 | 948.7 | 7.4 (5.8-9.4) | 1.81 (1.31-2.51) | <0.001 |

| Recent AIDS knowledge | |||||

| 86% or more correct | 74 | 2159.4 | 3.4 (2.7-4.3) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| <86% correct | 64 | 574.3 | 11.1 (8.7-14.4) | 3.25 (2.29-4.61) | <0.001 |

| Recent tattoo | |||||

| No | 157 | 3188.7 | 4.9 (4.2-5.8) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 4 | 76 | 5.3 (1.4-13.5) | 1.07 (0.29-2.79) | 0.84 |

| Recent medical injection | |||||

| No | 98 | 2114.9 | 4.6 (3.8-5.7) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 64 | 1150.6 | 5.6 (4.3-7.2) | 1.20 (0.86-1.66) | 0.26 |

| Number of recent sexual partners | |||||

| None | 90 | 1864.2 | 4.8 (3.9-6.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| One | 31 | 774.3 | 4.0 (2.7-5.7) | 0.83 (0.53-1.26) | 0.37 |

| Two or more | 46 | 633 | 7.3 (5.3-9.7) | 1.51 (1.03-2.17) | 0.03 |

| Recent CSW partner | |||||

| No | 98 | 2391.1 | 4.1 (3.4-5.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 68 | 866.2 | 7.9 (6.1-10.0) | 1.92 (1.38-2.64) | <0.001 |

| Recent condom use with CSW | |||||

| No CSW partners | 98 | 2391.1 | 4.1 (3.3-5.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Always | 12 | 336.9 | 3.6 (1.8-6.2) | 0.87 (0.43-1.59) | 0.67 |

| Sometimes | 12 | 169 | 7.1 (3.7-12.4) | 1.73 (0.87-3.17) | 0.09 |

| Never | 44 | 357.6 | 12.3 (8.9-16.5) | 3.00 (2.05-4.33) | <0.001 |

| Male partner ever | |||||

| No | 151 | 2997.9 | 5.0 (4.3-5.9) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 14 | 249.5 | 5.6 (3.1-9.4) | 1.11 (0.59-1.93) | 0.68 |

| Recent male partner | |||||

| No | 161 | 3210.6 | 5.0 (4.3-5.9) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 4 | 38.9 | 10.3 (2.8-26.4) | 2.05 (0.55-5.35) | 0.19 |

| Circumcision | |||||

| No | 164 | 3059.4 | 5.4 (4.6-6.3) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 1 | 186.7 | 0.5 (0.01-3.0) | 0.10 (0.01-0.56) | <0.001 |

| Recent urethritis | |||||

| No | 130 | 2862.3 | 4.5 (3.8-5.4) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 35 | 387.1 | 9.0 (6.3-12.6) | 1.99 (1.33-2.91) | <0.001 |

| Recent genital ulcer | |||||

| No | 75 | 2514.4 | 3.0 (2.4-3.8) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Yes | 88 | 686.5 | 12.8 (10.4-15.9) | 4.30 (3.12-5.93) | <0.001 |

Of 2260 individuals in the analysis, 13 were missing data on number of recent sexual partners at one of their followup visits, 26 were missing recent tattoo, 22 were missing recent medical injection, and 9 were missing genital ulcer on examination at one follow-up

CSW=Commercial sex worker

CI=Confidence interval

In the first multivariate proportional hazards model (Table 5), three variables relating to social position were independently associated with HIV seroconversion. Compared to those completing high school, illiterate men had a relative risk (RR) of 2.79 (p<0.001), and men with a primary or middle school education had 1.73 times the risk (p=0.002). Non-Hindu men were 57% less likely to seroconvert than Hindus (p=0.002), and men having a mother tongue other than Marathi or Hindi were 1.57 times more likely to seroconvert (p=0.04).

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of HIV-1 seroconversion, male attendees of STD clinics in Pune, India, May 1993-April 2000

| Characteristics | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social position | ||||

| Education | ||||

| High school or more | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Primary/middle school | 1.73 (1.23-2.43) *** | 1.51 (1.07-2.14)** | 1.42 (1.00-2.01)* | 1.44 (1.01-2.05)** |

| None/illiterate | 2.79 (1.79-4.35)**** | 2.27 (1.44-3.58)**** | 2.04 (1.29-3.24)*** | 1.86 (1.16-2.99)*** |

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Non-Hindu | 0.43 (0.25-0.73)*** | 0.43 (0.25-0.73)*** | 0.43 (0.26-0.74)*** | 0.56 (0.33-0.97)** |

| Mother tongue | ||||

| Marathi/Hindi | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Other | 1.57 (1.01-2.42)** | 1.59 (1.03-2.46)** | 1.68 (1.08-2.59)** | 1.65 (1.05-2.57)** |

| Knowledge | ||||

| Recent AIDS knowledge | ||||

| 86% or more correct | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | |

| <86% correct | 2.33 (1.54-3.52)**** | 2.00 (1.31-3.05)*** | 1.56 (1.01-2.39)** | |

| Exposure | ||||

| Recent condom use with | ||||

| CSW partners | ||||

| No CSW partners | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Always | 1.15 (0.66-2.02) | 0.99 (0.56-1.75) | ||

| Sometimes | 1.66 (0.91-3.05)* | 1.35 (0.72-2.55) | ||

| Never | 2.35 (1.61-3.41)**** 1.89 (1.29-2.78)*** | |||

| Susceptibility | ||||

| Circumcision | ||||

| No | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| Yes | 0.18 (0.04-0.74)** | |||

| Recent genital ulcer | ||||

| No | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| Yes | 2.84 (2.01-4.01)**** | |||

Regression coefficients were converted and tabled as hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) Level of statistical significance:

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

CSW=Commercial sex worker

After controlling for recent level of knowledge, prior awareness of AIDS was no longer significantly related to HIV seroconversion, indicating that a subset of men, never having heard of AIDS before entry into the study, were never able to attain an adequate level of AIDS knowledge after repeated counselling. Thus, in Model 2, recent AIDS knowledge was added to the overall model, resulting in an RR of 2.33 for those scoring less than 86% on the knowledge scale (p<0.001). Controlling for AIDS knowledge reduced RR for illiterates by 19% from 2.79 to 2.27, and for men with some education 13% from 1.73 to 1.51. Knowledge had little effect on the relationship between religion or mother tongue and incident HIV infection.

Among the exposure factors, only lack of consistent use of condoms with sex workers was independently associated with seroconversion and was added to Model 3. Relative to not having recent sex worker partners, never having used condoms with sex workers in the prior three months conferred an RR of 2.35 (p<0.001), inconsistent use of condoms with sex workers an RR of 1.66 (p=0.09), and consistent use of condoms with sex workers an RR of 1.15 (p=0.62). Entering this exposure factor into the model decreased RR for illiterates from 2.27 to 2.04, and for primary/middle school attendees from 1.51 to 1.42. The addition of the exposure factors had no effect on RR for religion, but it increased RR for mother tongue slightly from 1.59 to 1.68.

Finally, the co-factors that could affect susceptibility to HIV included circumcision, urethritis, and genital ulceration. Of these, circumcision and genital ulceration were independently associated with acquisition of HIV and were added to Model 4. Circumcised men had a decreased risk for seroconversion compared to uncircumcised men (p=0.018), and men with recent genital ulcer had 2.84 times greater risk (p<0.001). Inclusion of these susceptibility factors resulted in a reduction of RR for illiterates from 2.04 to 1.86 with little change in RR for primary/middle school attendees. The addition of circumcision decreased the effect of religion on HIV seroconversion. The protective effect of being non-Hindu (RR=0.43, p=0.002) increased to 0.56 (p=0.037) due to the association between being Muslim and circumcision practices.

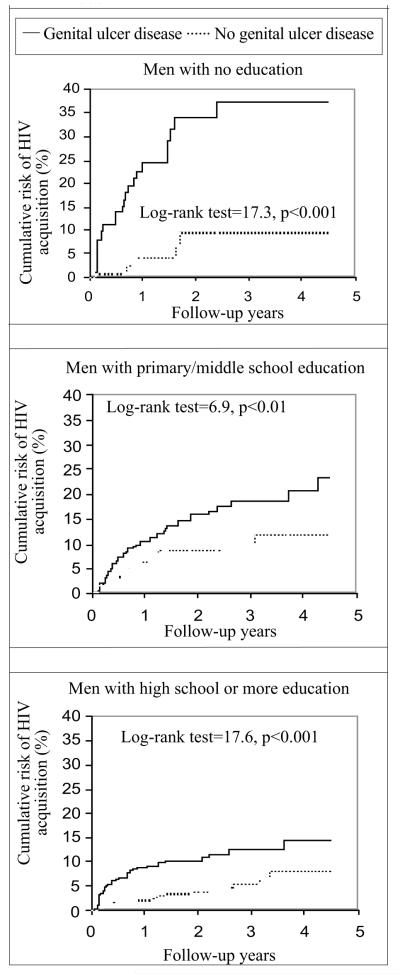

Interaction terms between level of education and all other variables in Model 4 were assessed to find any differential effects of risk factors by educational level. A significant interaction between no education and genital ulceration was detected (p=0.024) as shown in a bivariate fashion in Figure 1. These Kaplan-Meier curves by status of genital ulcer disease stratified by level of education demonstrate that genital ulceration has a greater effect on risk of seroconversion among those with less education. To display the effect modification in the multivariate model, the risk of genital ulcer disease for each level of education was modelled relative to men who completed high school and had no genital ulcer disease. As Figure 2 demonstrates, RR was 7.02 (95% CI 3.89-12.66, p<0.001) for illiterate men with genital ulcer disease, 3.62 (95% CI 2.14-6.11, p<0.001) for men with some education and genital ulcer disease, and 3.02 (95% CI 1.78-5.12, p<0.001) for men who completed high school with genital ulcer disease. And for men with no evidence of genital ulcer disease, those with no education had an RR of 1.09 (95% CI 0.45-2.64, p=0.84), and those with primary/middle school education had an RR of 1.70 (95% CI 1.06-2.74, p=0.028) relative to men without genital ulcer disease who completed high school.

Fig. 1.

Risk of HIV seroconversion by genital ulcer disease, stratified by level of formal education of attendees of STD clinics, Pune, India 1993-2000

Fig. 2.

Adjusted risk of HIV seroconversion interaction of genital ulcer disease and level of formal education, STD clinics, Pune, India, 1993-2000

DISCUSSION

The conceptual framework of Diderichsen and Hallqvist identifies four mechanisms by which social stratification might affect the health status: social context, differential exposure, differential vulnerability, and differential consequences of ill health (23). Each of these potential mechanisms provides a corresponding policy-intervention point. We have tailored this framework specifically to the health problem of HIV/AIDS transmission using Anderson’s model of the determinants of community-level transmission of STI (24). The first mechanism operates at the intentionally broad level of social context and includes community-level factors that impact upon transmission of STI: gender norms, migration patterns, work environments, and characteristics of sexual networks, such as partnership concurrency, and sexual mixing patterns of population subgroups. The second mechanism is differential exposure: the sexual partner turnover rate, the average number of sex acts per unit time, and the infection prevalence rate in the pool of potential partners. The third mechanism is differential vulnerability: the ability of the immune system to fight infection may be impaired by malnourishment, or by deficiencies of particular micronutrients (25-30). Susceptibility to HIV infection is enhanced by concurrent STIs which may increase transmission from a partner with STI (31-33) and increase acquisition through breakdown of mucosal barriers, or increasing the number of target immune cells in the genital region (34,35). Male circumcision may decrease susceptibility to acquisition of HIV (36). And finally, the fourth mechanism through which social stratification may affect health is differential consequences, which is beyond the scope of this analysis and may include more rapid progression to diagnosis of AIDS and death and greater social discrimination and stigmatization.

The pathways through which socioeconomic status affects the risk of acquiring HIV infection in this population were shown to be multiple and varied. The heightened risk among the most-disadvantaged men is mediated by various factors, including lack of understanding of HIV/AIDS transmission, increased exposure through high-risk behaviour, and increased susceptibility operating through biological co-factors. Also striking was the residual effect: even after controlling for the major risk behaviours and AIDS knowledge and modelling interaction terms, a moderate effect of lack of education on risk of HIV acquisition remained. This residual effect may be due to various unmeasured factors, including factors relating to social context, higher rates of HIV prevalence among partners in the most disadvantaged group enhancing their exposure, attenuated immunity from deficiencies of micro- and macronutrients leading to greater susceptibility, and residual confounding due to lack of complete control for risk behaviours.

Our study provides evidence that by enhancing diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of genital ulcer disease among the most disadvantaged men, the disparity in rates of HIV incidence could be lessened. There is also evidence that the difference may indeed be deemed unfair: higher rates of infection are not necessarily mediated by choice of individuals to practise higher risk behaviour, and the constraints under which choices are made certainly differ by socioeconomic status. Given the same level of AIDS knowledge, the same level of risk behaviour, and the same level of biological co-factors, the most disadvantaged men still have higher rates of HIV incidence. The task remains to further elucidate the complex biosocial mechanisms behind this disparity. Also identified was a higher infection rate among men with native language other than Marathi or Hindi. This finding reflects a need for interventions delivered in various languages to migrants from other states (37) and within the clinic setting for counselling in the native tongue of the client.

The present study did not have the requisite data measured at multiple levels to sort out the compositional effects from the contextual effects of social status on rates of HIV incidence. Compositional effects would result from the lower social strata being composed of individuals who practise higher risk behaviour, or who have a lower level of immune protection. Contextual effects refer to physical or social/environmental influences that confer higher rates upon members of the group (38), for example, a higher prevalence pool, or higher sexual partner concurrency rates. The rate of HIV prevalence in the pool of potential partners can be more important than the number of sexual partners in conferring risk to an individual (39). Since sexual mixing patterns in non-commercial sex settings tend to be confined to one’s own social stratum, this becomes a vicious cycle. For those in the lower strata of society, as we have found in this study, the infection rates are higher due to a constellation of factors, thus their partners are more likely to be infected.

Over the past decade, human rights have become an integral component of the international development agenda. Improvements in human capital—health and education of the population—will be necessary for sustaining the development trajectory of India. Elemental to that goal is combating the epidemic of HIV/AIDS, which will require addressing basic issues of human rights and decreasing the vulnerability of those in the lower social strata (40). There is a need for increasing personal illness control through access to quality health services and effective treatment of STI, availability of condoms, and information, education, and communication campaigns that are culturally and linguistically appropriate and accessible to migrants and those who are illiterate and have no access to radio or television (41). Structural interventions for income generation, supplementation of micro- and macronutrients, and community-based voluntary counselling and testing programmes with a strong human rights and health education focus are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (AI 41369), through a contract from the NIAID, NIH through Family Health International (FHI) (AI 35173). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the ICMR, NIH, or FHI. We would like to thank Dr. Phadke, Dr. Naik, Dr. Sule, Dr. Tolat, and Dr. Dharmadhikari from the B.J. Medical College and Dr. Ravetkar and Dr. Jadhav from the Health Department of the Pune Municipal Corporation, for their guidance, cooperation, and help in setting up our study clinics. We would like to gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions of the entire HIVNET and Pathogenesis of Acute HIV Infection Project teams in patient counselling and care, collection of data and specimens, laboratory procedures, and data management.

REFERENCES

- 1.India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National AIDS Control Organization . Estimation of AIDS in India 2001. HIV/AIDS Indian scenario; [accessed on 10 September 2002]. http://naco.nic.in/vsnaco/indianscene/esthiv.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braveman P, Tarimo E. Social inequalities in health within countries: not only an issue for affluent nations. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1621–35. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B, Shi L. Policy relevant determinants of health: an international perspective. Health Policy. 2002;60:201–18. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Over M. The effects of societal variables on urban rates of HIV infection in developing countris: an exploratory analysis, chapter 2. In: Ainsworth M, Fransen, Over M, editors. Confronting AIDS: evidence from the developing world. European Commission; Brussels: [accessed on 15 September 2002]. 1998. http://europa.eu.int/comm/development/body/theme/aids/limelette/html/lim02.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmer P. Infections and inequalities: the modern plagues. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2001. p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, Senkoro K, Newell J, Klokke A, et al. A community trial of the impact of improved sexually transmitted disease treatment on the HIV epidemic in rural Tanzania: 2. Baseline survey results. AIDS. 1995;9:927–34. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith J, Nalagoda F, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Sewankambo N, Konde-Lule J, et al. Education attainment as a predictor of HIV risk in rural Uganda: results from a population-based study. Int J STD AIDS. 1999;10:452–9. doi: 10.1258/0956462991914456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.India epidemiological fact sheet on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Geneva: [accessed on 25 September 2002]. 2002. http://www.unaids.org/hivaidsinfo/statistics/fact_sheets/pdfs/India_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahluwalia MS. The economic performance of the States: a disaggregated view; twelfth NCAER Golden Jubilee Lecture. National Council for Applied Economic Research; Delhi: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Registrar General of India [accessed on 15 September 2002];Census of India 2001 (provisional) http://www.censusindia.net.

- 11.Pune Municipal Corporation . Integrated population and development project. Vol. 1. Pune Municipal Corporation; Pune: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:254–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [accessed on 15 September 2002];International Society for Equity in Health. http://www.iseqh.org/en/workdef.htm.

- 14.Gangakhedkar RR, Bentley ME, Divekar AD, Gadkari DA, Mehendale SM, Shepherd ME, et al. Spread of HIV infection in married monogamous women in India. JAMA. 1997;278:2090–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. Measuring socioeconomic inequalities in health. Vol. 5. World Health Organization Regional Office; Copenhagen: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene ME, Biddlecom AE. Absent and problematic men: demographic accounts of male reproductive roles. Popul Dev Rev. 2000;26:81–115. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehendale SM, Rodrigues JJ, Brookmeyer RS, Gangakhedkar RR, Divekar AD, Gokhale MR, et al. Incidence and predictors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion in patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in India. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1486–91. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR. 1993;1993;42:1–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control Interpretation and use of the Western blot assay for serodiagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections. MMWR. 1989;38:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. V. II. The design and analysis of cohort studies. Vol. 70. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenig MA, Bishai D, Khan MA. Health interventions and health equity: the example of measles vaccination in Bangladesh. Popul Dev Rev. 2001;27:283–302. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brookmeyer R, Quinn T, Shepherd M, Mehendale S, Rodrigues J, Bollinger R. The AIDS epidemic in India: a new method for estimating current human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) incidence rates. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:709–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diderichsen F, Evans T, Whitehead M. The social basis of disparities in health. In: Evans T, Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Bhuiya A, Wirth M, editors. Challenging inequities in health: from ethics to action. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2001. pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson RM. Transmission dynamics of sexually transmitted infections. In: Holmes K, Sparling PF, Mardh P-A, Lemon SM, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 3rd ed McGraw Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semba RD. Vitamin A and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc Nutr Soc. 1997;56:459–69. doi: 10.1079/pns19970046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehendale SM, Shepherd ME, Brookmeyer RS, Semba RD, Divekar AD, Gangakhedkar RR, et al. Low carotenoid concentration and the risk of HIV seroconversion in Pune, India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:352–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200104010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baeten JM, Mostad SB, Hughes MP, Overbaugh J, Bankson DD, Mandaliya K, et al. Selenium deficiency is associated with shedding of HIV-1-infected cells in the female genital tract. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:360–4. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200104010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang AM, Graham NMH, Semba RD, Saah AJ. Association between serum vitamin A and E levels and HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS. 1997;11:613–20. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendich A. Antioxidant vitamins and human immune responses. Vitam Horm. 1996;52:35–62. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60406-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maciaszek JW, Coniglio SJ, Talmage DA, Viglianti GA. Retinoid-induced repression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core promoter activity inhibits virus replication. J Virol. 1998;72:5862–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5862-5869.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seck K, Samb N, Tempesta S, Mulanga-Kabeya C, Henzel D, Sow PS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cervicovaginal HIV shedding among HIV-1 and HIV-2 infected women in Dakar, Senegal. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:190–3. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW, Ndinya-Achola JO, Kreiss JK, Gakinya MN, et al. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:233–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plummer FA, Wainberg MA, Plourde P, Jessamine P, D’Costa LJ, Wamola IA, et al. Detection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in genital ulcer exudate of HIV-1-infected men by culture and gene amplification. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:810–1. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stamm WE, Handsfield HH, Rompalo AM, Ashley RL, Roberts PL, Corey L. The association between genital ulcer disease and acquisition of HIV infection in homosexual men. JAMA. 1988;260:1429–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mar Pujades RM, Obasi A, Mosha F, Todd J, Brown D, Changalucha J, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 infection increases HIV incidence: a prospective study in rural Tanzania. AIDS. 2002;16:451–62. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200202150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey RC, Plummer FA, Moses S. Male circumcision and HIV prevention: current knowledge and future research directions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:223–31. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta I, Mitra A. Knowledge of HIV/AIDS among migrants in Delhi slums. J Health Popul Dev Countr. 1999;2:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sweat MD, Denison JA. Reducing HIV incidence in developing countries with structural and environmental interventions. AIDS. 1995;9(Suppl A):S251–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Contextual factors and the black-white disparity in heterosexual HIV transmission. Epidemiology. 2002;13:707–12. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawkes S, Santhya KG. Diverse realities: sexually transmitted infections and HIV in India. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(Suppl 1):i31–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National family health survey-2 [accessed on 15 September 2002]; http://www.nfhsindia.org/data/mh/mhchap6.pdf.