Abstract

A mapping exercise as part of a pathway study of women in secure psychiatric services in the England and Wales was conducted. It aimed to (i) establish the extent and range of secure service provision for women nationally and (ii) establish the present and future care needs and pathways of care of women mentally disordered offenders (MDO) currently in low, medium and enhanced medium secure care. The study identified 589 medium secure beds, 46 enhanced medium secure beds (WEMSS) and 990 low secure beds for women nationally. Of the 589 medium secure beds, the majority (309, 52%) are in the NHS and under half (280, 48%) are in the independent sector (IS). The distribution of low secure beds is in the opposite direction, the majority (745, 75%) being in the IS and 254 (25%) in the NHS. Medium secure provision for women has grown over the past decade, but comparative data for low secure provision are not available. Most women are now in single sex facilities although a small number of mixed sex units remain. The findings have implications for the future commissioning of secure services for women.

Keywords: women, mentally disordered offender, secure services

Introduction

Known changes in the provision of secure services for women in England and Wales include some development of single sex secure facilities for women (Kettles, 1997; DH, 2000; Hassell & Bartlett, 2001), movement of women out of high secure care into more appropriate secure services (Home Office, 2000, 2001) and the creation of Women's Enhanced Medium Secure Services (WEMSS). The current system of care for women mentally disordered offenders (MDO) is more complex than for men and its present configuration is unclear. These services are currently subject to a strategy review at national level. The aim of this paper is to provide comprehensive data on the pattern of secure service provision for women nationally as this is essential to any more detailed consideration of care needs. Reported here is the distribution of secure bed numbers for women across security level within the NHS and the independent sector (IS).

Method

Complementary methods were used to ascertain and check the number and type of secure beds available to women nationally. There are 10 Specialised Commissioning Groups in England as well as the Welsh Health Specialised Services Committee (WHSSC) who are responsible for the commissioning of secure forensic services. The Specialised Commissioning Groups are known by their regions: the South West, South East, South Central, East of England, East Midlands, West Midlands, Yorkshire and Humberside, North East, North West and London. Commissioners were asked to identify all the NHS service providers in their region and the IS service providers they use. Commissioners were asked to inform their NHS service providers of the service evaluation after which the research team contacted both NHS and IS secure units. We also checked web sites for IS and NHS units and when relevant made clarificatory phone calls.

All low and medium secure women's units (excluding psychiatric intensive care units) in England and Wales were asked to provide details of their bed numbers at each level of security and whether they were mixed or single sex. A census date of 6 am on 7 September 2011 was given to establish the number of beds that could be and were on that date occupied by women. Telephone interviews were also conducted with the majority of service providers; they were used to confirm and clarify bed numbers and the gender status of the ward/unit.

Women resident in low and medium secure inpatient settings were included in the sample, regardless of diagnosis and Mental Health Act 1983 Section type. We explicitly requested that secure services for learning disability (LD) be included. The sample does not include rehabilitation or step down facilities. Emergency beds were included in the bed numbers.

Several labelling issues regarding the security level and gender specificity of provider units emerged as data were c ollected.

Security level

Across the country, there were three units with hybrid beds. Hybrid beds can change in their security status usage. We have used occupancy numbers on the census date and the highest level of security to which patients can be admitted.

One ‘Enhanced Low Secure’ unit was classified as medium secure for the purpose of the current study as it can accept women who require medium security.

Mixed wards

There is no accepted comprehensive definition of single and mixed sex provision. For the purpose of this study, wards in which men and women share the same corridors (but have en-suites/separate wash areas) are considered mixed wards. The classification here of mixed does not mean that units are not compliant with the requirements of regulatory inspections; units made attempts to create separate living areas for example to keep women at one end of the corridor or place them in different ‘wings'.

Mixed units were clear about the number of beds available for women, even if there was some flexibility, such as gender hybrid beds. For the purpose of this mapping exercise, we used the actual number of women in beds not the unit size.

Findings

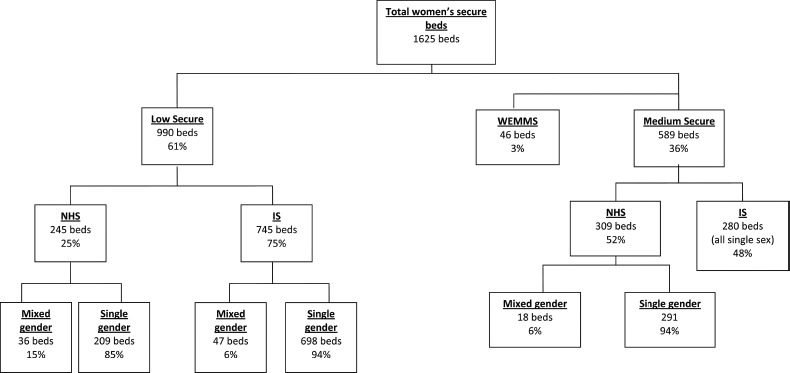

On the census date 7 September 2011, there were 1625 (100%) secure beds for women nationally of which 46 (3%) were enhanced medium secure (WEMSS), 589 (36%) were medium secure and 990 (61%) low secure (see Figure 1). Two hundred and eighty-three (17%) of the 1625 secure beds were for women with LDs.

Figure 1.

Bed numbers for women in NHS and independent sector (IS) secure services.

Just over half of all women's medium secure beds were provided by the NHS (309, 52%) and 280 (48%) by the IS. Almost all medium secure beds, 571 (97%), were single sex. However, the study revealed that a small number of NHS medium secure services continue to provide mixed sex facilities, in total 18 beds. There were no mixed sex medium secure beds in the IS.

Three quarters of low secure provision was provided by the IS (745 beds, 75%) and one quarter by the NHS (245 beds, 25%). Most low secure beds, 907 (92%), were single sex facilities. In both the NHS and the IS, there was a small proportion of mixed sex units. There were more beds of this kind in the IS but mixed sex beds were a higher proportion of total beds available in the NHS.

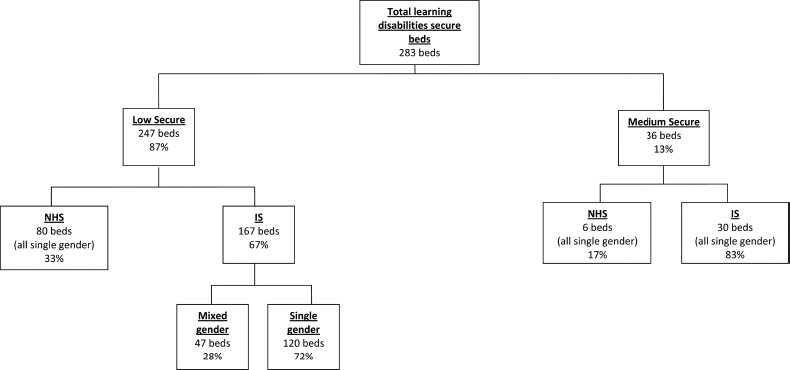

The pattern of provision of LD beds was distinctive. Learning disability beds constituted only 6% (36 beds) of all medium secure provision but 25% (247 beds) of low secure provision. Learning disability beds, both in low and medium security facilities, were more likely to be mixed than the rest of the beds (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Learning disability bed numbers for women in NHS and independent sector (IS) secure services.

The geographical distribution of beds nationally is illustrated below in Figures 3 and 4. They show that parts of England and Wales have no NHS provision for women whilst LD NHS provision is confined to the North. Independent Sector LD provision is strikingly located in coastal areas with no obvious connection to metropolitan areas of high population density. The IS provides services from a larger number of physically separate units than the NHS.

Figure 3.

Map of NHS medium and low and learning disability services. Map pins are spaced, where relevant, to convey the presence of multiple units in a single location.

Figure 4.

Map of independent sector medium and low and learning disability services. Map pins are spaced, where relevant, to convey the presence of multiple units in a single location.

Discussion

This is the first study to establish the national picture of medium and low secure beds available for female service users. This will assist local commissioners by providing not only a comprehensive snapshot of services but also a benchmark for their own local commissioning decisions. The anticipated reconfiguring of forensic commissioning structures through the National Commissioning Board may provide an opportunity for national data to be routinely collected.

The study's findings illuminate the difficulty providers and commissioners have in understanding the way in which current provision has developed. Medium secure provision is best understood. There has been significant growth over the past decade in the number of medium secure beds available for women. In 2000, there were 342 (100%); there are now 589, an increase of 247 (72%). Also, a new category, i.e. WEMSS unique to women has been developed. The rationale for women, but not men, having access to this additional category of security is unclear. Low secure beds have not previously been mapped in the same way and it is not possible to say whether these numbers are increasing, deceasing or staying the same over time. Nor, again in contrast to medium security, is it possible to be clear that these units are meaningfully all fulfilling the same function (DH, 2012). While developments over the last few years have gone a long way towards ensuring that medium secure standards are uniform (DH, 2004, 2007), low secure provision lags behind. High secure provision has been reduced since 2000 (Tilt, Perry, Martin, McGuire, & Preston, 2000), and the current allocation of 60 high secure beds for women is very different from 10 years ago (DH, 2002). It is not possible to conclude whether there has, in bed number terms, been an overall growth in secure hospital provision for women in the recent past, handicapping informed capacity planning.

Data reported here highlight the importance of the IS in this area of health care. New legislation may alter the existing mixed economy of provision as competition and choice determine commissioning priorities. The rate of increase in cost of forensic provision is known to have outstripped that of other components of mental health. The cost of adult mental health services rose by 58% between 2002/3 and 2009/10. Spending on secure and high dependency services (including psychiatric intensive care, low, medium and high dependency settings) for men and women rose by 141% during the same period. It accounts for 18.9% of the DH national spend on adult mental health (Mental Health Strategies, 2010). This study did not address the price or cost of services. However, the total costs of secure services to women are not known and neither is the relative cost of IS or NHS secure beds for women. The NHS provides all high secure and enhanced medium secure beds but the IS have not explicitly developed similar services. In contrast, the IS dominates low secure provision and continues to vie with the NHS in medium secure provision as it did 10 years ago (Hassell & Bartlett, 2001). No such comparisons are available for low secure provision as it has not been comprehensively mapped in the past. The geography of secure provision demonstrated in this paper suggests that the IS has provided some facilities linked to centres of population density but others sites are distant. Equally, it indicates that some parts of the NHS do not provide any local facilities themselves. Reed (DH & HO, 1992, 1992–1994) argued in favour of local provision for men and women to facilitate recovery. Into the mainstream (DH, 2002) argued that for women proximity and contact with children was an additional important issue. Substantial components of current provision, particularly LD provision, would seem to be at odds with this general principle.

The implementation of policy about safe provision in the secure hospital estate for women has largely been achieved (DH 1997, 2003). This is reassuring given the findings of Mezey, Hassell, and Bartlett (2005) that women in single sex units report less vulnerability to sexual abuse and serious physical assault than women in mixed sex units. Medium secure provision has demonstrably changed (Hassell & Bartlett, 2001) and though it cannot be evidenced in the same way, it seems likely that policy has driven changes in low security too. Where mixed sex provision remains, it may be a consequence of the need to balance local provision in the NHS with unit architecture and the demand for beds. Mixed sex provision will continue to be subject to scrutiny by external agencies such as the Care Quality Commission (CQC) operating in a contemporary climate of understanding of women's vulnerabilities and in line with recent guidelines for secure services (DH 2004, 2007, 2012).

There remain significant numbers of IS LD mixed sex facilities whose occupants might be seen as doubly vulnerable in this regard. The pattern of current provision inherently limits choice for this patient population. The data also show that care planning for many of these women is rendered more difficult by placing them at an obvious distance from their area of origin. The geography of the placements can create additional hurdles to family involvement in care and may reduce the ease with which patients make the transition to community placements in their home areas. The geography of their placements may also incur additional costs relating to regular case review. This system requires review and consideration in future service planning.

Conclusions

The study's findings suggest a greater demand for low secure facilities for women than for medium secure facilities. This may reflect the different offending profile of female compared to male forensic service users. It highlights the importance of the interface between female psychiatric intensive care and forensic services for women. It demonstrates considerable progress in the provision of gender-specific facilities, as well as raising questions about the appropriateness of current services for women with the additional vulnerability of LD. Future planning of services requires accurate basic data, e.g. occupancy, referral and refusal rates on national service provision to be available readily rather than to require research effort on a periodic basis. New technologies, such as that which generated maps for this paper, can be used to provide accurate, quickly updated basic information on a national basis at low cost.

A coordinated approach to commissioning is needed to ensure adequate provision at local and national level of the required tiers of security and pathways of care to the community for women forensic service users. New commissioning structures need to incorporate the best practice guidance on gender sensitive care for women, not only at medium secure level (DH, 2007) but also at low secure level.

Limitations of the Study

Locked rehabilitation facilities were not included in the study some of which are likely to accommodate female MDOs, particularly those with LD diagnoses. This category was not included because of the complexity in differences between providers namely NHS and IS. In the interests of clarity, only beds that the service providers referred to as medium or low (plus the two exceptions of high support and low enhanced) were considered. The exercise also raised the question of what is the definition of a ‘locked rehabilitation unit'.

This study is about bed designation and therefore does not address the characteristics of the actual occupants of these units. There may be more flexibility in terms of admitting women to these facilities than is indicated by the designation. Specifically, figures for LD beds in the IS do not mean that, unlike the NHS, they are solely LD units, rather that they will accept women with LDs.

Acknowledgements

The study on which this paper is based was commissioned by London Secure Commissioning Group but the views expressed are those of the authors. The authors are grateful to Matthew Fiander for comments on drafts of this paper.

References

- Department of Health. The patients’ charter: Privacy and dignity and the provision of single sex accommodation (NHS circular EL 97(3)) London: Department of Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Safety, privacy and dignity in mental health units. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Women's mental health: Into the mainstream. Strategic development of mental health care for women. London: Department of Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Mainstreaming gender and women's mental health. Implementation guidance. London: Department of Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Health offender partnerships. Standards for medium secure units. London: Department of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Best practice guidance: Specification for adult medium secure services. London: Department of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Consultation on low secure services and psychiatric intensive care. London: Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health & Home Office. Review of health and social services for mentally disordered offenders and others requiring similar services (final summary report, Reed Report Cm 2088) London: HMSO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health & Home Office. Review of services for mentally disordered offenders and others with similar needs. Vol. 1: Final summary report (Cm 2088) 1992–1994. 1992; Vol. 2: Service needs (Report of the community, hospital and prison advisory groups and a steering committee overview), 1993: Vol. 4: Finance, staffing and training (Reports of the finance, staffing and training advisory groups), 1993; Vol. 5: Special issues and differing needs (report of the official working group on services for mentally disordered offenders with special needs), 1993; Vol. 6: Race, gender and equal opportunities, 1994; Vol. 7: People with learning disabilities (mental handicap) or with autism, 1994. London: HMSO.

- Hassell Y. Bartlett A. The changing climate for women patients in medium secure psychiatric units. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2001;25:340–342. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office. The Government's strategy for women offenders. London: Home Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office. The Government's strategy for women offenders – Consultation report. London: Home Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kettles A. A survey of patients’ preferences for mixed or singles sex wards. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental health Nursing. 1997;4:55–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.1997.tb00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Strategies. 2009/10 National survey of investment in adult mental health services (report prepared for DH Mental Health Strategies) London: Department of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mezey G. Hassell Y. Bartlett A. Safety of women in mixed sex and single sex medium secure units: staff and patients perceptions. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:579–582. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilt R. Perry B. Martin C. McGuire N. Preston M. Report of the review of security at the high security hospitals. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]