Abstract

Three heterocyclic systems were selected as potential surrogates of the amide linker for a series of 1,6-disubstituted-4-quinolone-3-carboxamides, potent and selective CB2 ligands exhibiting scarce water solubility, with the aim of improving their physicochemical profile and also of clarifying properties of importance for amide bond mimicry. Among the newly synthesized compounds, the 1,2,3-triazole derivative 11 emerged as the most promising in terms of both physicochemical and pharmacodynamic properties. When assayed in vitro, 11 exhibited inverse agonist activity, whereas, in vivo, in the formalin test in mice, it produced analgesic effects antagonized by a well established inverse agonist. Metabolic studies allowed the identification of the side chain hydroxylated derivative 32 as its only metabolite which, in its racemic form, showed still appreciable CB2 selectivity, but was 150-fold less potent than the parent compound.

Keywords: Bioisosteres, cannabinoid, quinolones, receptors, structure-activity relationships

Introduction

The pharmacological effects of cannabinoids are mediated by two distinct receptors, the CB1 and CB2 receptors.[1,2] They are seven transmembrane receptors that belong to the rhodopsin-like family Class A of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and are involved in a wide variety of multiple intracellular signal transduction pathways.[3]

CB1 receptors are expressed predominantly in the CNS with particularly high levels in cerebellum, hippocampus and basal ganglia but are also expressed, albeit at much lower levels, in the peripheral nervous system as well as on the cells of the immune system, in the heart, vascular tissues, and the testis. On the other hand, the expression of the CB2 receptor is more restricted, limited primarily to immune and hematopoietic cells.[4,5]

The human CB2 receptor shows only 44% overall homology with the CB1 receptor. Despite this low homology, most plant-derived, endogenous, and classical synthetic cannabinoids have similar affinities for either receptors. This limits the therapeutic utility of non-selective, brain penetrable cannabinoid agonists due to their known psychotropic effects via the CB1 receptor. Given the predominant peripheral distribution of the CB2 receptors and considering the differences in signal transduction mechanisms between the two receptors, it has been hypothesized that selective activation of CB2 receptor should be devoid of the undesired psychoactive effects typically induced by activation of the CB1 receptor. A selective CB2 agonist is, therefore, therapeutically desirable.[6]

It has been demonstrated that CB2-selective agonists display antinociceptive activity in well-validated models of acute pain, persistent inflammatory pain, post-operative pain, cancer pain and neuropathic pain.[7–9] Other potential therapeutic targets for CB2-selective agonists include multiple sclerosis,[10] amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,[11] Huntington’s disease,[12] stroke,[13] atherosclerosis,[14] gastrointestinal inflammation states,[15] chronic liver diseases,[15] bone disorders[16] and cancer.[17–20]

On the other hand, a number of reports suggest that selective CB2 inverse agonists/antagonists may serve as novel immunomodulatory agents in the treatment of a variety of acute and chronic inflammatory disorders.[21]

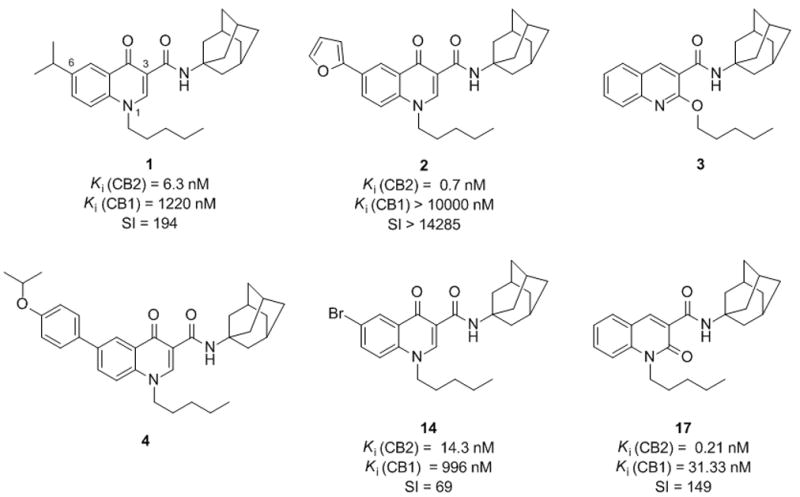

Our research group has recently described a series of 6-substituted 4-quinolone-3-carboxamides as highly selective CB2 receptor ligands eliciting Ki values in the low nanomolar or sub-nanomolar range and selectivity index values as high as > 14,000.[22–23] Some of the compounds, such as 1,[22] characterized by an agonist profile, proved to have an antinociceptive effect in vivo while 2[23] showed inverse agonist-like activity (Figure 1). Despite their highly interesting pharmacodynamic profile, the compounds of this series suffered from low solubility which, in some cases, hampered the biological testing of the synthesized molecules. Balancing lipophilicity (necessary to reach the target receptor) and water solubility (necessary for biological testing and to ensure acceptable bioavailability) is therefore a challenging endeavour for structural optimization of CB2 ligands which are inherently lipophilic molecules.[24] It has also become clear that low solubility can affect biological assays by reducing the concentration of the compound at the target site, thus resulting in erroneous SAR analysis.[25]

Figure 1.

Structure of prototypical 4-quinolone-3-carboxamides 1–4, 14, and 17.

Keeping these concepts in mind and starting from compounds 3 and 4 (Figure 1) that had shown solubility issues in the biological assays, we planned to improve their solubility through a bioisosteric approach[26] with the aim of obtaining high affinity CB ligands endowed with good selectivity for the receptor subtype 2 and characterized by an acceptable physicochemical profile.

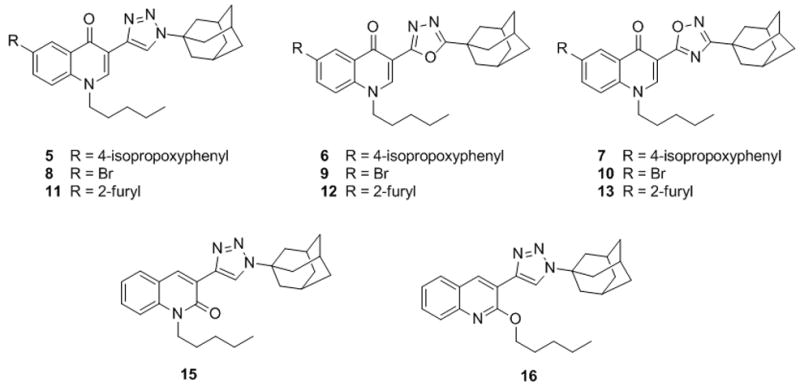

To this end, we took into consideration three different heterocyclic systems to be used as amide surrogates in compound 4, speculating that replacing the amide moiety with suitable five-membered heterocyclic rings could improve solubility. In particular, based on previous findings from the literature, 1,2,3-triazole[27] (compound 5) and 1,3,4-oxadiazole[28] (compound 6) (Figure 2) were selected as amide replacements according to their favourable logP values. Despite its higher logP value, compound 7, characterized by a 1,2,4-oxadiazole moiety, was synthesized as well due to the good pharmacokinetic properties shown by 1,2,4-oxadiazole-based CB2 agonists.[29] Moreover, in order to study the effect of the bioisosteric replacement on the affinity and selectivity of our compounds, 4-quinolones 8–10 and 11–13 (Figure 2) were prepared as analogues of 14[22] and 2,[23] respectively, that had exhibited high CB2 affinity and selectivity values in binding assays. The results obtained for the newly synthesized bioisosteres in terms of solubility and affinity/selectivity were finally used to guide the design of the 2-quinolone 15 and the 2-alkoxyquinoline 16 (Figure 2), 1,2,3-triazole analogues of compounds 17 and 3, respectively.[30]

Figure 2.

Structure of 4-quinolone-3-carboxamide bioisosteres 5–13 and 15–16.

Metabolic studies were carried out on compound 11 with the aim of investigating its metabolic stability and, possibly, identifying its principal metabolites. In general, drug metabolism reactions convert lipophilic compounds to more hydrophilic products so that the body can remove these xenobiotic substances more easily. Therefore, an active metabolite can serve as a modified lead compound around which new structure-activity relationships can be investigated with the aim of designing second generation molecules endowed with an improved solubility profile. Also, in cases in which inactive metabolites are formed, appropriate structural modification could decrease the drug metabolism, resulting in improved drug exposure.[31–33] For unequivocal identification, the major metabolites predicted in silico for compound 11 were also synthesized. This allowed us to use these compounds as analytical standards in the HPLC and MS/MS studies and to have authentic samples for biological testing.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

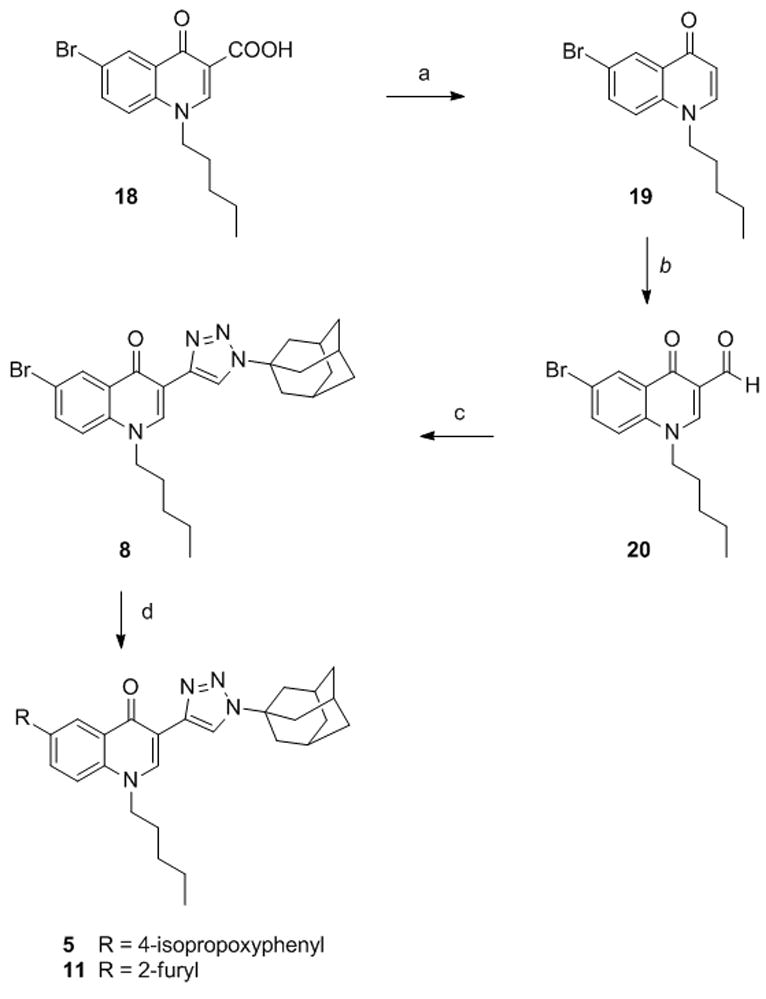

1,2,3-Triazolyl derivatives 5, 8 and 11 were prepared starting from 6-bromo-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (18)[23] which was first decarboxylated by microwave irradiation to give the 3-unsubstituted quinolone 19 (Scheme 1). The reaction was carried out at 240 °C using 1-butyl-3-methyl-imidazolium chloride (BMIC) as solvent and a stoichiometric amount of water.[34] Isolation of 19 was easily accomplished by simple extraction followed by rapid filtration on silica gel. Treatment of 19 with hexamethylenetetramine (HMT) in TFA followed by hydrolysis of the intermediate imine gave the C-3 formylated derivative 20 in almost quantitative yield.[35] The 1,2,3-triazole moiety (compound 8) was obtained by elaboration of the formyl group through a two step one pot procedure consisting of a Bestmann-Ohira homologation followed by microwave-aided Cu-catalyzed azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition.36 Finally, the 6-isopropoxyphenyl derivative 5 and the 6-furanyl derivative 11 were prepared starting from the 6-bromoquinolone 8 through a Suzuki coupling.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 5, 8, 11. Reagents and conditions. a) BMICl, H2O, MW, 240 °C, sealed tube. b) i. HMT, TFA, MW, 120 °C, sealed tube; ii. H2O. c) i.dimethyl-1-diazo-2-oxopropylphosphonate, K2CO3, MeOH/THF 1/1; ii. AdN3, CuI, MW, 100 °C, sealed tube. d) R-B(OH)2, Pd(OAc)2, PPh3, 1N Na2CO3, DME, EtOH, MW, 150 °C.

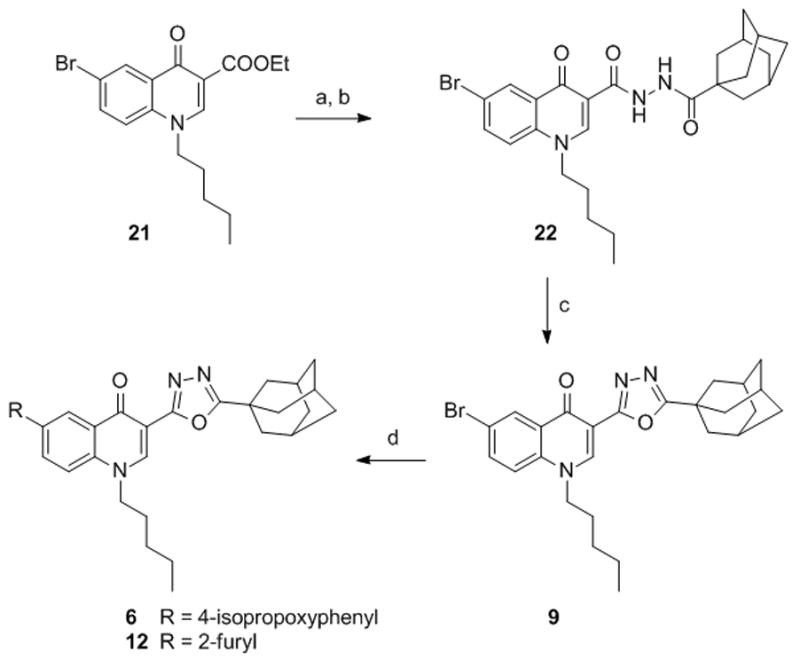

1,3,4-Oxadiazolyl derivatives 6, 9 and 12 were prepared starting from the intermediate 21,[23] whose ester functional group was converted into the acylhydrazide 22 by treatment with hydrazine followed by acylation with 1-adamantanecarbonyl chloride (Scheme 2). Cyclization of the acylhydrazide 22 to the 1,3,4-oxadiazolyl derivative 9 was successfully accomplished using POCl3 at 110 °C.[37] Suzuki coupling between the 6-bromoderivative 9 and the appropriate boronic acid, afforded the 6-isopropoxyphenyl derivative 6 and the 6-furanyl derivative 12.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 6, 9, 12. Reagents and conditions. a) NH2NH2.H2O, EtOH, reflux. b) 1-adamantanecarbonyl chloride, DMAP, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C→rt. c) POCl3, 110 °C. d) R-B(OH)2, Pd(OAc)2, PPh3, 1N Na2CO3, DME, EtOH, MW, 150 °C.

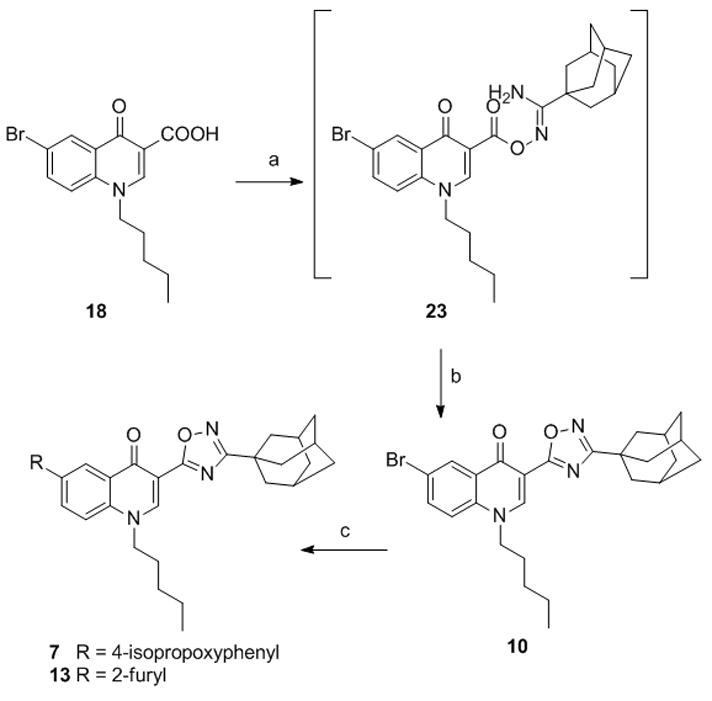

Preparation of 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives 7, 10 and 13 (Scheme 3) started from compound 18 which was reacted overnight with 1-adamantanecarboxamidoxime[38] to give the O-acylamidoxime intermediate 23.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds 7, 10, 13. Reagents and conditions. a) 1-adamantanecarboxamidoxime, HBTU, DIPEA, DMF. b) MW, 150 °C, 10 min. c) R-B(OH)2, Pd(OAc)2, PPh3, 1N Na2CO3, DME, EtOH, MW, 150 °C.

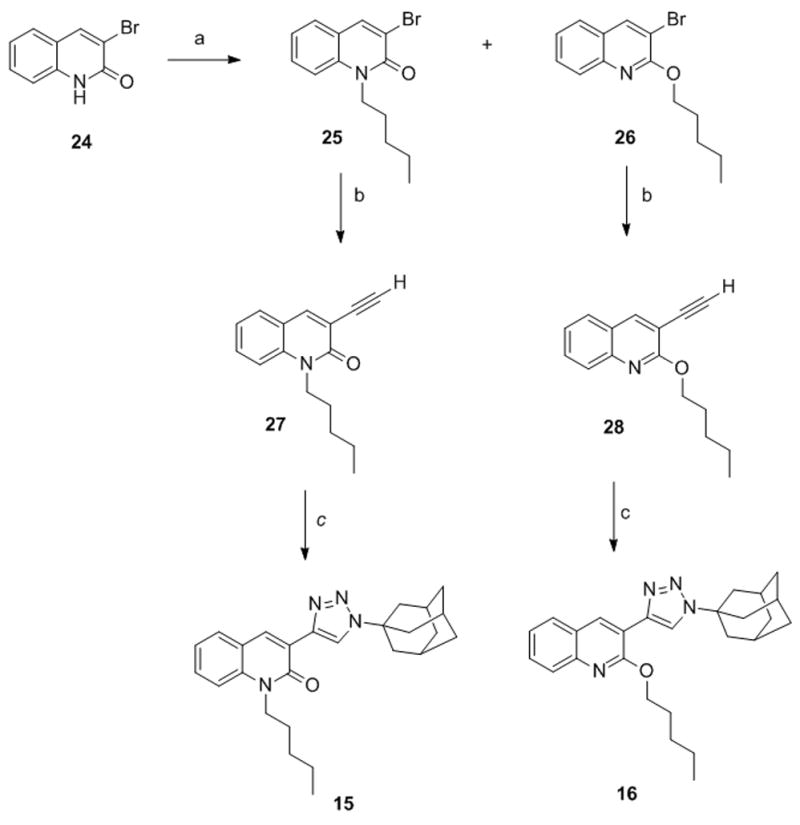

Irradiation of the reaction mixture with MW at 150 °C for 10 minutes gave the 6-bromoderivative 10 which was in turn converted to the 6-isopropoxyphenyl derivative 7 and the 6-furanyl derivative 13 by Suzuki reaction.[39] For the synthesis of the 1,2,3-triazole derivatives 15 and 16 (Scheme 4) easily accessible 3-bromo-quinolin-2(1H)-one (24)[40] was reacted with pentyl iodide to give a mixture of the N-alkylated quinolinone 25 and the 2-alkoxyquinoline 26 in a 2.5/1 ratio.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of compounds 15 and 16. Reagents and conditions. a) pentyl iodide, K2CO3, 18-crown-6, CH3CN, 90 °C. b) i. TMSA, CuI, Pd(Ph3)2Cl2, DIPEA, dioxane, MW, 120 °C, sealed tube; ii. K2CO3, MeOH, THF. c) AdN3, CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, MW, 150 °C, sealed tube, DMF.

After separation via flash chromatography, 25 and 26 were transformed into the corresponding alkynyl derivatives 27 and 28 through Sonogashira reaction with trimethylsilylacetilene (TMSA), followed by deprotection. Elaboration of the triple bond into a 1,2,3-triazole moiety afforded the final compounds 15 and 16 in 70% and 37% yield, respectively.

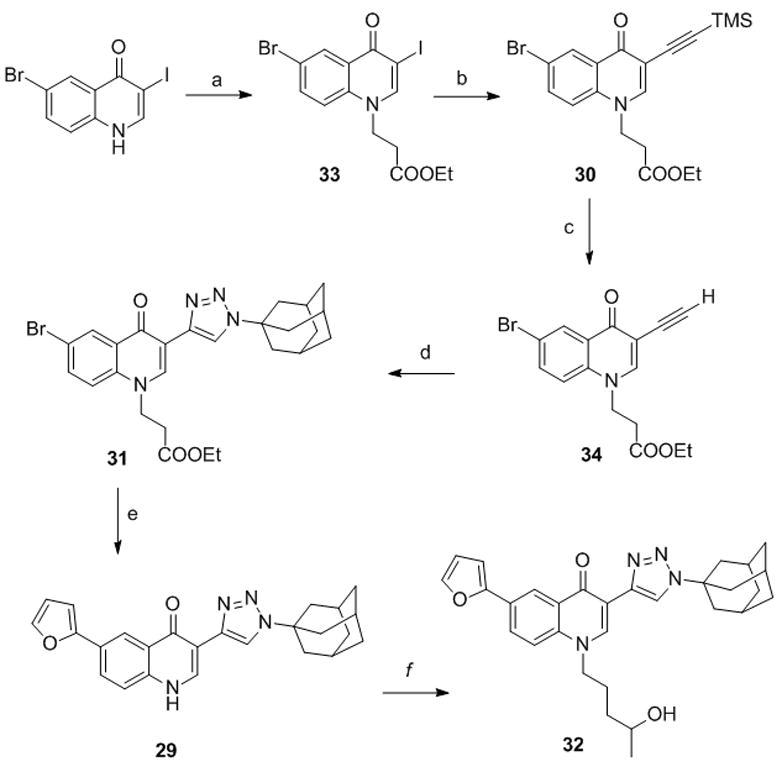

Chemical synthesis of drug metabolites may be rather challenging, sometimes requiring the complete revision of the synthetic pathway set up for the preparation of the parent compounds. Indeed, in order to synthesize compound 29 (Scheme 5) predicted as possible metabolite of 11 (vide infra) we had to change the synthetic approach.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of compounds 29 and 32. Reagents and conditions. a) ethyl acrylate, TRITON B, DMF, 90 °C. b) TMSA, CuI, Pd(Ph3)2Cl2, DIPEA, THF. c) KF, EtOH. d) AdN3, CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, tBuOH/H2O, 1/1. e) 2-furyl boronic acid, Pd(OA c)2, PPh3, 1N Na2CO3, DME, EtOH, MW, 150 °C. f) i. (5-iodopentan-2-yloxy)(tert-butyl)dimethylsilane, K2CO3, DMF, 90 °C;. ii. TBAF, THF.

6-Bromo 3-iodo-quinolone[41] was first protected at the NH group using ethyl acrylate, then a regioselective Sonogashira coupling on 33 gave the protected alkyne 30. Removal of the TMS group to give 34, followed by Huisgen reaction afforded derivative 31 bearing the appropriate substitution at position 1 of the 1,2,3-triazole ring. Finally, through a Suzuki reaction we obtained the target compound 29 by simultaneous insertion of a furyl moiety at position 6 and deprotection at N1. The N-substituted derivative 32 was obtained by alkylation with (5-iodopentan-2-yloxy)(tert-butyl)dimethylsilane[42] followed by OH deprotection.

Liphophilicity and Solubility Studies

LogP values for amides 2, 4 and 14 and for the newly synthesized bioisosteres 5–7, 8–10 and 11–13 were both calculated in silico, using the software ChemDraw Ultra 8.0 of CambridgeSoft Corporation (Cambridge, MA), and experimentally determined by HPLC. Indeed, HPLC provides an easy and reliable way to determine the partition properties of a compound based on its chromatographic retention times, which directly relate to the compound’s distribution between the aqueous/organic mobile phase and the standard reversed-phase stationary phase.[43] In order to cover a wide range of lipophilicity, several measurements at different concentrations of the organic solvent in the mobile phase are needed for each compound. Then, to compare retention times using different organic phase concentrations, they are extrapolated to zero organic solvent concentration. The results are reported in Table 1. The data analysis revealed that, despite minor differences between the calculated and the experimental logP values, compounds with a 1,2,3-triazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole nucleus were characterized by the lowest logP values and that these values were, in all cases, lower than that of the corresponding amide (compare for example logP values for compounds 2, 11 and 12). Solubility studies were carried out on the new compounds of the 6-furyl series (11–13) together with the amide derivative 2 following a kinetic approach, a methodology becoming increasingly popular since DMSO stock solution has been established as a de facto standard for compound storage and distribution to different assays.[44] We started with a 10 mM stock solution of the compound in DMSO which was diluted with water to get a 5% DMSO environment. After an 18 h incubation time, the precipitate was filtered off and the concentration of the compound was determined by HPLC.[44] Solubility values (see below into brackets) were in accordance with calculated logP values and revealed the following solubility trend for the four compounds:

Table 1.

Lipophilicity and Pharmacological Data[a] of Compounds 2, 4, 5, 7–16, 29, 32.

| logP | CB1[b,c] | CB2[c,d] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| compd | Calcd[e] | Exp[f] | Ki[g] (nM) | Ki (nM) | S.I.[h] |

| 2[23] | 6.41 | 6.40 | >10000 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | >14285 |

| 4 | 7.78 | 8.08 | NTi | NT | - |

| 5 | 6.92 | 7.78 | > 10000 | 1680.0 ± 24.5 | > 6 |

| 7 | 8.33 | 7.71 | > 10000 | > 10000 | - |

| 8 | 5.15 | 5.83 | > 10000 | 32.2 ± 1.2 | > 284 |

| 9 | 5.53 | 5.15 | > 10000 | 250.0 ± 8.6 | > 40 |

| 10 | 6.56 | 5.77 | 207.5 ± 5.5 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 76 |

| 11 | 5.55 | 5.18 | > 10000 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | > 8620 |

| 12 | 5.93 | 5.26 | > 10000 | 6.5 ± 2.2 | > 1543 |

| 13 | 6.96 | 6.38 | 33.0 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 82 |

| 14[22] | 6.01 | 6.44 | 996. 0± 12.1 | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 69 |

| 15 | 5.81 | - | 321.9 ±2.1 | 11.1 ± 3.6 | 29 |

| 16 | 6.65 | - | 3414.6 ± 9.8 | 12.6 ± 4.3 | 271 |

| 29 | 3.39 | - | > 10000 | > 10000 | - |

| 32 | 3.35 | - | > 10000 | 190.0 ± 10.0 | > 52 |

| SR144528[j,k] | - | - | >2820 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | >522 |

| Rimonabant[j,l] | - | - | 12.0 ± 8.3 | 790.0 ± 11.2 | 0.015 |

Data represent mean values +/− SD for at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate and are expressed as Ki (nM).

CB1: human cannabinoid type 1 receptor.

For both receptor binding assays, the new compounds were tested using membranes from HEK cells transfected with either the CB1 or CB2 receptor and [3H]-(−)-cis-3-[2-hydroxy-4-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)-phenyl]-trans-4-(3-hydroxy-propyl)-cyclohexanol ([3H]CP-55,940).

CB2: human cannabinoid type 2 receptor.

Calculated as clogP using the software ChemDraw Ultra 8.0 of CambridgeSoft Corporation (Cambridge, MA).

Determined by HPLC using a Lichrocart 125-4 Lichrospher 100 RP-18 (5 μm) column and MeOH/H2O mixtures as the eluent.

Ki: “Equilibrium dissociation constant”, that is the concentration of the competing ligand that will bind to half the binding sites at equilibrium, in the absence of radioligand or other competitors.

S.I.: selectivity index for CB2, calculated as Ki(CB1)/Ki(CB2) ratio.

NT, not tested because of solubility problems.

The binding affinities of reference compounds were evaluated in parallel with the test compounds under the same conditions.

CB2 reference compound.

CB1 reference compound.

Thus, the bioisosteric substitution of the amide moiety with 1,2,3-triazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole nucleus resulted in a significant improvement in terms of reduced lipophilicity and increased water solubility of the molecule. Although the logP and solubility values for 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives were not promising, all three synthesized compounds 7, 10 and 13 exhibited adequate solubility in the conditions used for the biological assay, thus ensuring the possibility to evaluate affinity and selectivity of these new CB2 receptor ligands.

Affinity Studies with Immobilized Cannabinoid Receptor OT Columns

We have recently developed an on-line screening method for CB1 and CB2 ligands, where cellular membrane fragments of a chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line, KU-812, were immobilized onto the surface of an open tubular (OT) capillary to create a CB1/CB2–OT column.[46] Five out of the first nine compounds we had prepared (namely compounds 7, 9–11, 13), representative of the structural variability around the quinolone scaffold, were submitted to a preliminary test using the OT column to rank them as strong/moderate/weak or no affinity ligands for the CB2 receptor. The concentration of the marker ligand used was 0.25 nM [3H]-Win-55,1212 for the CB2 receptor.[46] All of them, with the exception of compound 7 which showed very little displacement, were able to displace the marker with high efficacy suggesting a potentially high CB2 affinity for all these ligands, which is consistent with the Ki determined by competitive binding experiments (below).

In Vitro Pharmacology

In order to assess their affinity and selectivity towards the human recombinant CB1 and CB2 receptors and, also, to further validate our analytical methodology, all the synthesized compounds were screened in a competitive binding experiment in parallel with SR144528[47] and rimonabant[48] as reference CB2 and CB1 ligands, respectively, as previously described.[22] The results, in terms of binding affinities for the two receptors (Ki values), are reported in Table 1.

With the exception of the 6-isopropoxyphenyl derivatives 5 and 7 (KiCB2 = 1680 nM and > 10000 nM, respectively), all the newly synthesized bioisosteres showed high affinity for the CB2 receptor with Ki ranging from 250 nM (compound 9) to 0.4 nM (compound 13). Keeping fixed the substituent at the 6-position and analyzing the effect of the bioisosteric substitution, the best results in terms of CB2 affinity were obtained with the 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives, while 1,2,3-triazole analogues proved to be the most selective ones with selectivity index values (SI), calculated as Ki(CB1)/Ki(CB2) ratio, up to 8620 (compound 11). The strong affinity of the 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives for both receptors subtypes resulted in a significant loss of selectivity (in all cases, SI < 100). When considering both the affinity and selectivity, compound 11 emerged as the most promising with KiCB2 =1.2 nM and SI > 8620. In addition, the increase in solubility of 11 indicates that the insertion of a furyl ring at the 6- position of the quinolone scaffold combined with a 1,2,3-triazole bioisosteric substitution ensures the best results in terms of physicochemical and pharmacodynamic properties in the series.

The bioisosteric substitution of the amide bond with a 1,2,3-triazole was also promising in the case of the insoluble 2-alkoxyquinoline 3. Indeed, its bioisostere 16 showed excellent CB2 affinity and good selectivity (KiCB2 = 12.6 nM and SI = 272) thus representing a potential new lead for the development of a novel class of selective CB2 ligands.

Interestingly, all the preliminary data obtained in our on-line screening with OT columns were in line with those obtained in the in vitro pharmacological assays, confirming the validity of our analytical methodology for the pre-screening of libraries of potential cannabinoid ligands.

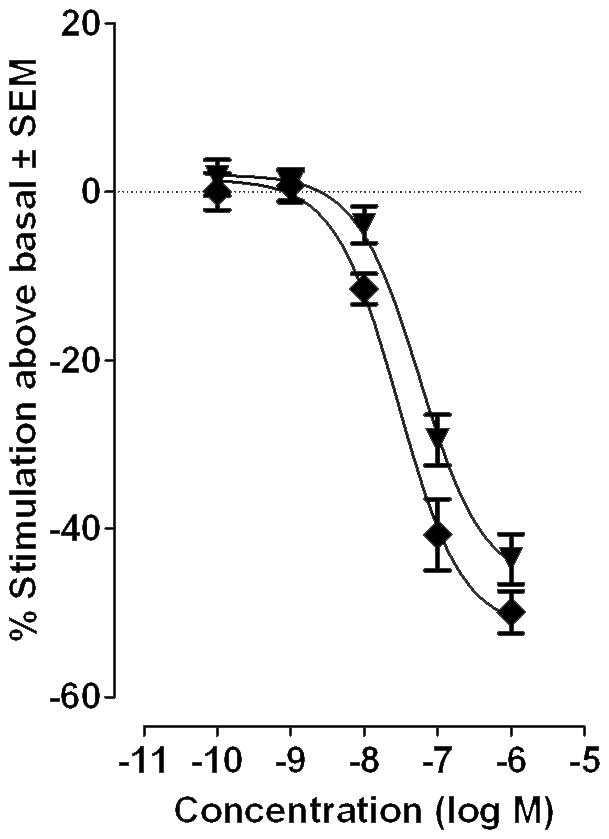

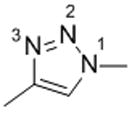

In order to gain some insight also in the functional activity of some of the novel compounds synthesized here, compounds 11 and 12 were tested for their effect on [35S]GTPγS binding to hCB2-CHO cell membranes.[49,50] Both compounds were found to elicit inverse agonist effects (Figure 3) with potencies reflecting their affinities for human CB2 (Table 1 and 2).

Figure 3.

The effect of compounds 11 (diamonds) and 12 (triangles) on [35S]GTPγS binding to hCB2-CHO cell membranes (n=8). Each symbol represents the mean percentage change in [35S]GTPγS binding ± SEM.

Table 2.

The EC50 and Emax values of CP55940, 11 and 12 for stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding on hCB2-CHO cell membranes.

| Compound | Emax | EC50 | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP55940 | 84.7% (78.3 and 91.1%) | 1.8 nM (0.9 and 3.3 nM) | 4 |

| 11 | −52% (−57.2 and −46.4%) | 29.3 nM (16.5 and 52.2 nM) | 8 |

| 12 | −46.6% (−52.5 and −40.6%) | 57.6 nM (33.2 and 102.8 nM) | 8 |

The 95% confidence limits (CLs) are shown in brackets. n represents the number of data values.

Computational Studies

The relative balance of the intermolecular interactions plays a significant role in the binding site stabilization, affecting receptor affinity and selectivity.[51] Analysis of strength and nature of such competitive non covalent interactions, thus represents an important aspect to rationalize the experimental data obtained from biological assays. In particular, we were interested in giving a possible explanation for the peculiar behavior of the 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivative 13 which, diversely from the other bioisosteric counterparts 11 and 12 endowed with high affinity and excellent CB2 selectivity, exhibited high affinity for both CB1 and CB2 receptors.

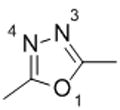

For this purpose, simplified five-membered ring molecule models were created replacing the adamantyl and quinolone segments of compounds 11–13 by methyl groups. The five membered ring models are depicted in Table 3 and differ in the number and in the disposition of the heteroatoms that are able to act as hydrogen bond acceptors.

Table 3.

Interaction Energies for Complexes between Models a–c and a Water Molecule

| System[a] | Interaction Energy (ΔE)[b] | |

|---|---|---|

|

Compound 12 | |

| W:O1 (a)[c] | −2.03 | |

| W:N3 (a) | −6.12 | |

| W:N4 (a) | −6.12 | |

|

Compound 13 | |

| W:O1 (b) | −3.68 | |

| W:N2 (b) | −4.77 | |

| W:N4 (b) | −5.08 | |

|

Compound 11 | |

| W:N2 (c) | −5.75 | |

| W:N3 (c) | −5.95 |

Schematic representation of the molecule models.

Interaction Energy between molecule and water is in kcal/mol.

Complexes are designated as W:X(m) where W stands for “water” molecule, “X” for the heteroatoms and “m” for molecule model.

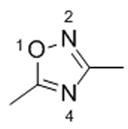

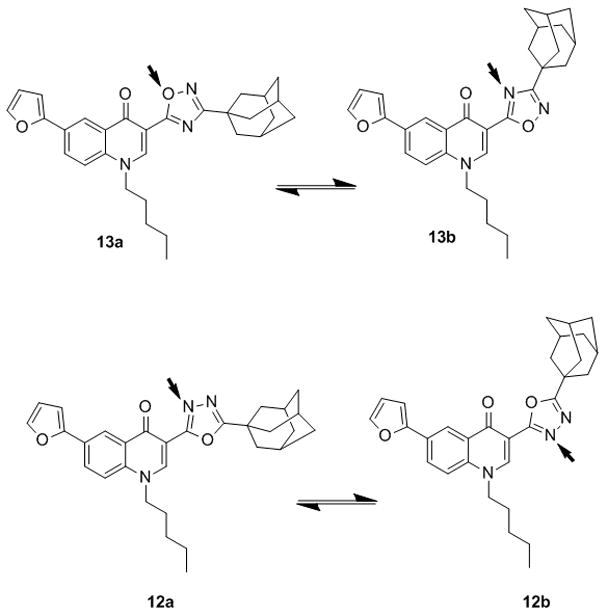

To quantify the relative strength of the hydrogen acceptor atoms a total of 8 complexes were then generated placing one water molecule in front of each heteroatom to form a hydrogen bond. Interaction energies of the complexes (Table 3) were analyzed according to Kitaura-Morokuma[52–54](KM) scheme and the energy decomposition analysis (EDA) are reported in Table 3. The KM analysis is in agreement with the general “rule” that a nitrogen atom in an unsaturated system is a much stronger hydrogen-bond acceptor than an oxygen atom.[55,56] Indeed, the W:O1(a) complex shows the lower interaction energy value (E = −2.03 kcal/mol), whereas W:N3(a) and W:N4(a) possess the highest interaction energy values (E = −6.12 kcal/mol) with the relative balance of the hydrogen bonding interactions amounting to more than 4 kcal/mol in favor of nitrogen atoms. Thus, it is improbable that oxygen atom acts as hydrogen bond acceptor in this system. The W:O1(b) complex shows an interaction energy value of −3.68 kcal/mol, whereas W:N4(a) and W:N4(b) show similar values of −4.38 kcal/mol and −4.69 kcal/mol, respectively. Due to the lower differences in the interaction energy, the oxygen atom of model (b) can effectively compete as hydrogen bond acceptor with nitrogen atoms. Thus, compound 13 may exist as two possible conformers, namely 13a and 13b (Figure 4) in which O1 and N4, respectively, could act as hydrogen bond acceptors. In these two conformations the adamantyl group would arrange in different spatial regions, thus possibly allowing profitable interactions with both cannabinoid receptors. The W:N2 (c) and W:N3 (c) show intermediate interaction energies and are able to form hydrogen bond interactions assuming the same spatial conformation of the compound 12.

Figure 4.

Alternative conformations for compound 12 and 13. Red arrows indicate H-bond acceptor sites.

The computational study performed on compounds 11–13 gave an insight into structural aspects differentiating compound 13 with respect to other bioisosteres 11 and 12. However, we do not assume these results may provide the definitive explanation for the affinity towards CB1 receptor shown by 13.

In Vivo Pharmacology

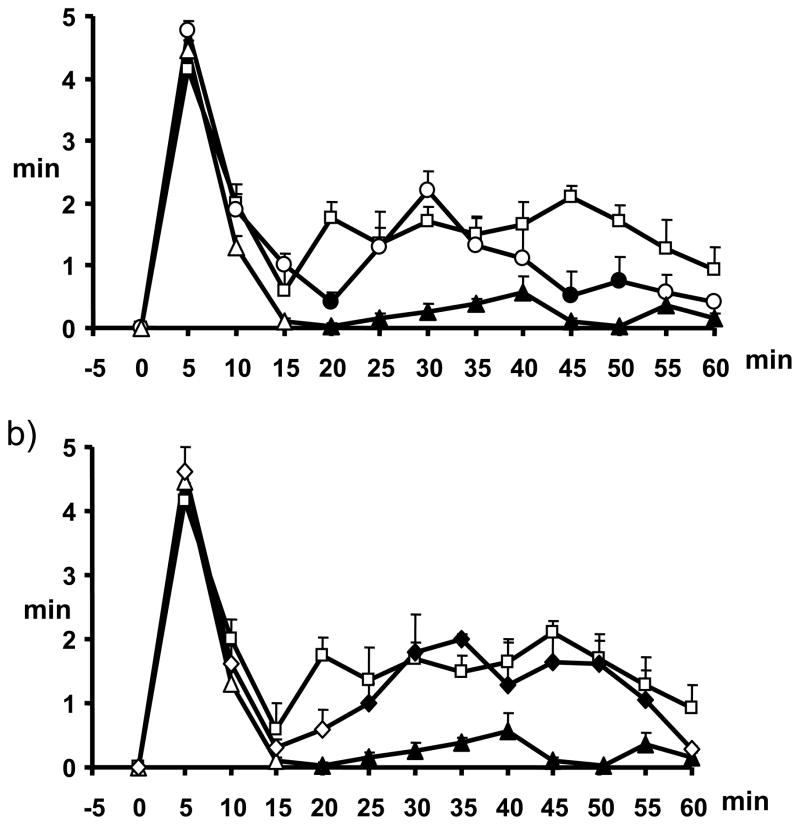

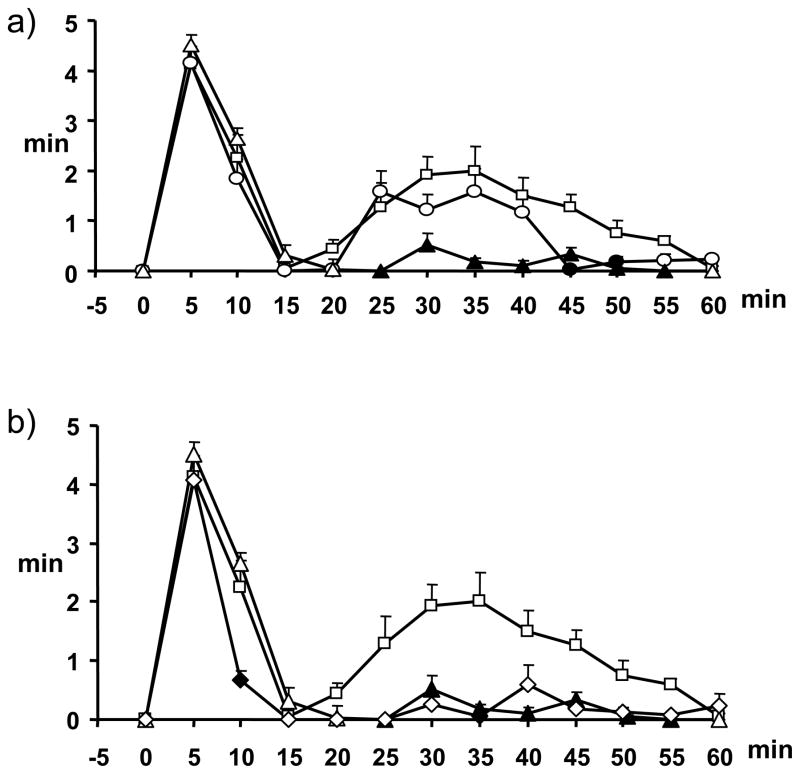

The in vivo activity of compounds 11 and 12 was evaluated in the formalin test of acute peripheral and inflammatory pain in mice. Formalin injection induces a biphasic stereotypical nocifensive behaviour. Nociceptive responses are divided into an early, short lasting first phase (0–7 min) caused by a primary afferent discharge produced by the stimulus, followed by a quiescent period and then a second, prolonged phase (15–60 min) of tonic pain. Fifteen min before injection of formalin, mice received intraperitoneal (ip) administration of vehicle or of either of the two compounds (1 or 3 mg/kg), alone or in combination with either the selective CB2 antagonist, 6-iodo-2-methyl-1-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indol-3-yl](4-methoxyphenyl)methanone (AM630) (1 mg/kg, ip), administered 5 min before the compound.[57] The results obtained for compounds 11 and 12 are presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effect of compound 11 (1–3 mg/kg, i.p.) alone (a) or in combination, at the dose of 3 mg/kg, with AM630 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) (b) in the formalin test in mice. The total time of the nociceptive response was measured every 5 min and expressed as the total time of the nociceptive responses in min. Results are mean ± SEM (n=8–10 for each group). In panel a, squares represent formalin 1.25%, circles compound 11 1mg/kg, triangles compound 11 3 mg/kg; filled circles and triangles denote statistically significant differences vs formalin. In panel b, squares represent formalin 1.25%, triangles compound 11 3 mg/kg, diamonds AM630 1 mg/kg + compound 11 3 mg/kg; filled triangles denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. formalin, while filled diamonds denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. 11. One-way analysis of variance followed by a Turkey-Kramer multiple comparisons test was used for data analysis.

Figure 6.

Effect of compound 12 (1–3 mg/kg, i.p.) alone (a) or in combination, at the dose of 3 mg/kg, with AM630 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) (b) in the formalin test in mice. The total time of the nociceptive response was measured every 5 min and expressed as the total time of the nociceptive responses in min. Results are mean ± SEM (n=8–10 for each group). In panel a, squares represent formalin 1.25%, circles compound 12 1mg/kg, triangles compound 12 3 mg/kg; filled circles and triangles denote statistically significant differences vs formalin. In panel b, squares represent formalin 1.25%, triangles compound 12 3 mg/kg, diamonds AM630 1 mg/kg + compound 12 3 mg/kg; filled triangles denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. formalin, while filled diamonds denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) vs. 12. One-way analysis of variance followed by a Turkey-Kramer multiple comparisons test was used for data analysis.

Both ligands exhibited antinociceptive activity in the formalin test. The dose of 3 mg/kg induced a significant reduction of the 2nd phase (and, to a much lesser extent, the 1st phase too, although only for 11) of the formalin-induced nocifensive behaviour (Figure 5 and Figure 6, Panel A). Pre-treatment with AM630 (1 mg/kg) completely abolished the antinociceptive effects exerted by compound 11 (Figure 5, Panel B), while it did not induce any change on the effect mediated by compound 12 (Figure 6, Panel B). Based on our previous studies on quinolones as CB ligands,[22,23,30,57] these data would have suggested for 11 an action as a direct CB2 agonist (in partial disagreement with the results of the [35S]GTPγS binding assay), and for 12 a possible action as CB2 inverse agonist (as suggested also by the [35S]GTPγS binding assay). Different outcomes from in vitro and in vivo functional data have been reported also previously, particularly for CB2 ligands, and have been explained with a potential behaviour as “protean agonists” for those compounds behaving as inverse agonists/antagonists in vitro and as agonists in vivo, possibly depending on constitutive activity of CB2 receptors.[58–60] We believe that the “protean agonist” behavior of CB2 ligands, acting as inverse agonists in vitro and as agonist in vivo, may be explained in part by the different endocannabinoid signalling that is likely to be present in vitro or in vivo. For example, the formation of heterodimers between CB2 receptors and other receptors in “real” cells and in vivo, or the occurrence of higher endocannabinoid levels, might dramatically alter the pharmacology of the ligands. Furthermore, although CB2 can inhibit the release of inflammatory mediators, thus producing in principle anti-inflammatory effects, this receptor has also been reported to promote migration of some inflammatory cells, which might produce either anti-inflammatory or pro-inflammatory actions, depending on where the receptor is activated in vivo.61 This could have influenced the response we have observed in vivo in the second phase of the formalin test, which does have an inflammatory component.

Metabolic Studies

Among all the tested compounds, quinolone 11, eliciting the most interesting pharmacodynamic, functional and solubility profile, was selected for further investigation with the aim of characterizing its CYP-dependent metabolism in human liver microsomal preparations.[62]

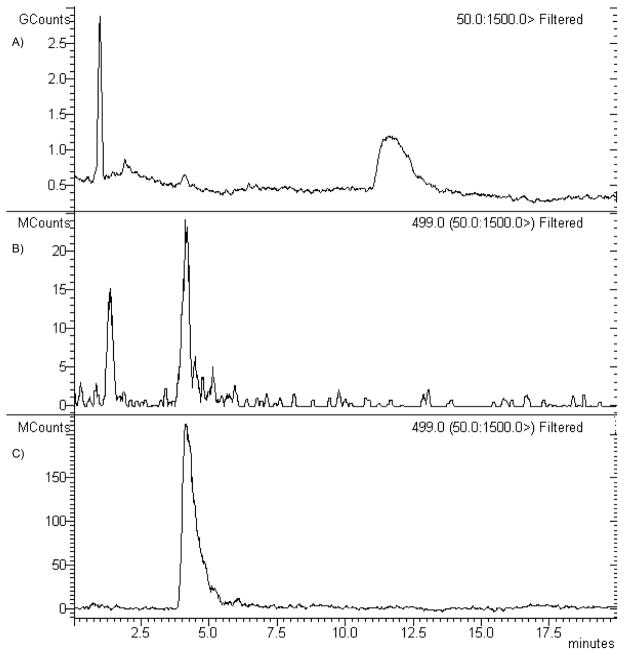

Prediction of possible metabolites of 11 by the use of the software MetaSite 3.1.2[63] resulted in the identification of two molecules, namely the N-dealkylated derivative 29 and the side chain hydroxylated derivative 32, which were also synthesized in our laboratories. In parallel, in vitro metabolic studies were carried out on compound 11 in the presence of human liver microsomes. Preliminary studies showed that the amount of products formed increased linearly with time up to 60 min and that the initial rates were proportional to the amount of microsomal protein added up to 1 mg/mL (data not shown). Kinetic analysis of compound 11 metabolism was performed at 60 min incubation time and in presence of 0.5 mg of microsomal proteins. At all the concentrations tested, only one peak was observed in the HPLC-MS analysis of the reaction mixture at about 4.3 min retention time, which was identified by comparison with an authentic sample of compound 32 (Figure 7).

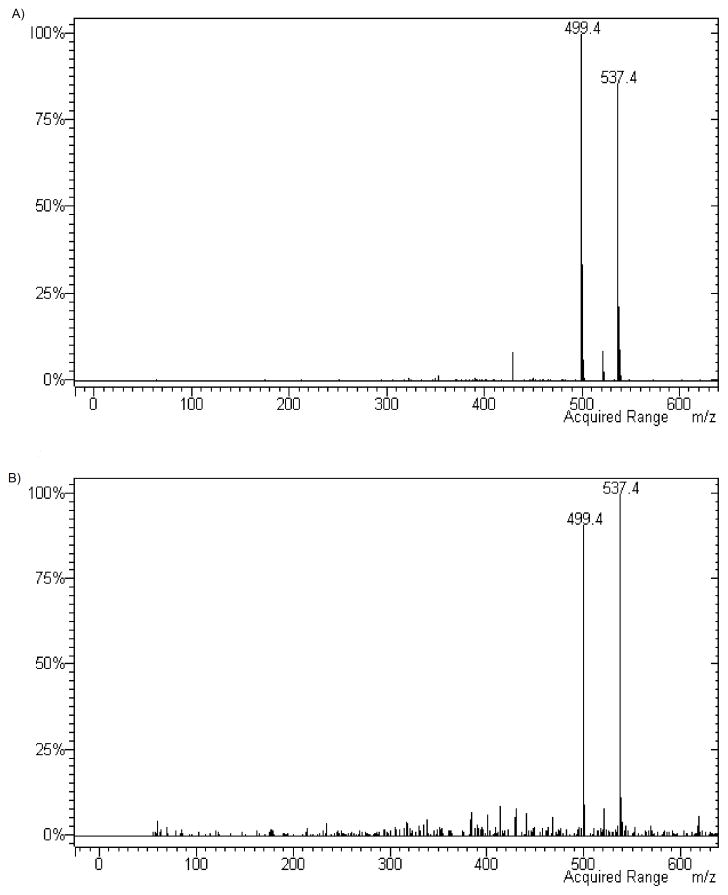

Figure 7.

HPLC-MS analysis of compound 32 and of the CYP-depend metabolite of compound 11. (A) HPLC (total ion current) profile of the reaction mixture obtained by incubating compound 11 with human microsomal preparations (B) Chromatogram of the peak at 499 m/z present in the human microsomal incubation mixture. (C) Chromatogram of the peak at 499 m/z of authentic compound 32.

The analysis of the mass spectra of the two compounds (Figure 8) resulted in identical molecular weight and the same fragmentation profile, both compounds showing peaks at 499 and 537 m/z corresponding to [M+H]+ and [M+K]+, respectively. These data, together with the evidence that compound 32 and the CYP-dependent metabolite of compound 11 presented an overlapping HPLC profile, in fact, indicate that the CYP-dependent metabolism of 11 promoted the formation of the C4-alkyl side chain hydroxylated derivative.

Figure 8.

MS spectra of authentic compound 32 (panel A) and of the CYP-dependent metabolite of compound 11 (panel B).

The interaction of 11 with CYPs followed a hyperbolic, Michealis-Menten, dependence. The apparent Km values of CYP for hydroxylated derivative formation was 5.21±0.60 (μM) suggesting high affinity of CYP towards the compound. However, this high affinity was accompanied by a low formation rate (Vmax 0.16±0.01 nmol x min−1 × mg1 protein) which resulted in a low intrinsic clearance value, as indicated by Vmax/Km value (0.030 min−1). With the aim of identifying the CYPs involved in the metabolic process of compound 11, an inhibition study was also performed indicating that CYP3A4 is the major isoform involved, while CYP1A and CYP2A are only partially implicated in this process (for further details see Supporting Information).

Compounds 29 and 32 were finally evaluated in the [3H]CP-55,940 binding assay (Table 1). As expected, 29, lacking the alkyl chain, showed no affinity for both receptor subtypes while 32, the actual metabolite of compound 11, maintained an appreciable CB2 selectivity (SI > 52) but lost receptor affinity (Ki = 190 nM vs Ki = 1.2 nM for compound 11), thus strongly reducing the interest in using this molecule as a lead compound for future developments. Studies directed at preparing the two enantiomers of compound 32 are ongoing in our laboratories.

Conclusions

The bioisosteric substitution of the amide moiety with three different heterocyclic rings on a set of 4-quinolone-3-carboxyamides allowed us to improve the solubility of the starting compounds, obtaining new molecules still endowed with very high affinity for the CB2 receptor. Among all the active compounds, only 13 exhibited high affinity for both receptor subtypes, resulting in a loss of CB2 selectivity. An attempt to rationalize this peculiar behaviour was carried on by the use of theoretical studies which highlighted the crucial role played by the hydrogen bonding properties of the particular heteroaromatic ring used as amide mimic. Both 11 and 12 behaved as inverse agonists in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay and, when evaluated in the formalin test of acute peripheral and inflammatory pain in mice, exhibited antinociceptive activity by inducing a significant reduction of the 2nd phase of the formalin-induced nocifensive behaviour, an effect that, with other quinolones, including the parent compound 2,[23] was previously ascribed to either agonism or inverse agonism at CB2 receptors. However, whilst pre-treatment with AM630 did not produce any change in the effect induced by 12, confirming for this 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivative a possible action as a CB2 inverse agonist, the analgesic activity of the 1,2,3-triazole derivative 11 was reversed by the selective CB2 antagonist AM630, thus making of 11 a full CB2 agonist in vivo, and a potential new member of CB2 “protean agonists”.[58–60] In conclusion, our results highlight the possibility of modulating the physicochemical properties of cannabinoid ligands through a simple bioisosteric approach without significant loss of receptor affinity. Some caution should, however, be used, on the basis of differences in aromatic, electrostatic and hydrogen bonding properties of different heteroaromatic ring systems used as amide surrogate, when considering the issue of selectivity and functional activity of the new designed compounds.

Experimental section

Chemistry

Reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Anhydrous reactions were run under a positive pressure of dry N2. Merck silica gel 60 was used for flash chromatography (23–400 mesh). IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin–Elmer BX FT-IR system using CHCl3 as the solvent. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were recorded at 200 MHz and 50 MHz respectively on a Brucker AC200F spectrometer and at 400 MHz and 100 MHz on a Brucker Advance DPX400. Chemical shifts are reported relative to tetramethylsilane at 0.00 ppm. Mass spectral (MS) data were obtained using Agilent 1100 LC/MSD VL system (G1946C) with a 0.4 mL/min flow rate using a binary solvent system of 95:5 methanol/water. UV detection was monitored at 254 nm. Mass spectra were acquired either in positive or in negative mode scanning over the mass range of 105–1500. Melting points were determined on a Gallenkamp apparatus and are uncorrected. Microwave irradiations were conducted using a CEM Discover Synthesis Unit (CEM Corp., Matthews, NC); all the reactions were performed in sealed tube maintaining constant temperature and variable wattage. Elemental analyses were performed on a Perkin-Elmer PE 2004 Elemental Analyzer and the data for C, H and N are within 0.4% of the theoretical values. HPLC analysis was performed using the following conditions: an Agilent 1100 series LC/MSD with a Lichrocart 125-4 Lichrospher 100 RP-18 (4.6 mm × 100 mm, 5μm) reversed phase column; method: 86% (v/v) of MeOH in H2O, isocratic, flow rate of 1 mL/min, UV detector, 254 nm.

6-Bromo-1-pentylquinolin-4(1H)-one (19)

A mixture of 6-bromo-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (18) (150 mg, 0.44 mmol), 1-butyl-3-methyl-imidazolium chloride (477 mg, 2.73 mmol) and water (53 μL, 2,96 mmol) was irradiated with microwave at 140 °C for 10 minutes (2 cycles). The reaction mixture was then treated with AcOEt and washed with brine. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The crude mixture was purified by flash chromatography (eluent: EtOAc) to give 19 (107 mg, 82%) as a pure compound: mp: 189 °C; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3): δ= 0.9 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 1.40 (m, 4H), 1.90 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (dd, J1 = 2.3 Hz, J2 = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (s, 1H), 8.72 ppm (s, 1H); IR (CHCl3): 1725, 1615 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 339 [M+H]+, 361 [M+Na]+. Anal. Calcd for C14H16BrNO: C 57.16, H 5.48, N 4.76, found: C 57.32, H 5.47, N 4.75.

1-(Adamantan-1-yl)-4-(6-bromo-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (8)

A solution of 19 (430 mg, 1.27 mmol) and hexamethylenetetramine (178 mg, 1.27 mmol) in TFA (1.8 mL) was irradiated with microwaves at 120 °C for 15 minutes. Another equivalent of hexamethylenetetramine was added and the reaction mixture was irradiated for 5 minutes, then treated with water (5 mL) for 10 minutes at room temperature, neutralized with a saturated solution of Na2CO3 and extracted with CH2Cl2.The organic phase was washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. A suspension of 200 mg of the crude compound, dimethyl-1-diazo-2-oxopropylphosphonate (357 mg, 1.86 mmol) and K2CO3 (387 mg, 2.80 mmol) in a MeOH/THF 1/1 mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. After addition of CuI (23 mg, 0.12 mmol) and 1-adamantly azide (110 mg, 0.62 mmol) the reaction mixture was irradiated with MW at 100 °C for 13 minutes. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue was dissolved with AcOEt and washed with a saturated solution of NH4Cl, H2O and brine. The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated to dryness. The crude mixture was purified by flash chromatography (eluent: AcOEt/PE, 1/1) to give 8 (86 mg, 28%) as a pure compound: 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3): δ= 0.87 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.13–1.48 (m, 4H), 1.77–2.27 (m, 15H), 4.2 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.64–8.66 (m, 2H), 8.79 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ= 13.9. 22.3, 28.8, 29.5, 36.0, 43.0, 53.9, 59.5, 113.1, 117.5, 117.6, 119.5, 128.4, 129.9, 134.7, 137.4, 140.3, 140.6, 173.0; MS (ESI): m/z 496 [M+H]+, 518 [M+Na]+. Anal. Calc for C26H31BrN4O: C 63.03, H 6.31, N 11.31, found: C 62.89, H 6.31, N 11.33.

2-(Adamantan-1-yl)-5-(6-bromo-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiadole (9)

A solution of 21 (800 mg, 2.18 mmol) in EtOH (4 mL) was added dropwise to a refluxing solution of hydrazine hydrated (1 mL, 21.8 mmol) in EtOH (3 mL). After 1 hour, the reaction mixture was concentrated and filtered. The residue was washed with Et2O, dried and dissolved in CH2Cl2 (33 mL). To this solution, cooled down to 0 °C, Et3N (356 μL, 2.56 mmol), DMAP (312 mg, 2.56 mmol) and 1-adamantanecarbonyl chloride (507 mg, 2.56 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 hours at room temperature, then the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. 100 mg of the solid thus obtained were dissolved in POCl3 (6 mL) and the corresponding solution was heated at 110 °C for 5 hours. After removal of POCl3 by distillation, the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2. The organic phase was washed with water and brine, then it was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated to dryness to give 9 (70 mg, 72%) as a pure compound: mp 241–243 °C; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3): δ= 0.87 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H), 1.34–1.35 (m, 4H), 1.77–2.11 (m, 15H), 4.17 (t, J = 7.4, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (dd, J1 = 1.8 Hz, J2 = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.62 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 13.8, 22.2, 28.1, 28.6, 34.3, 36.6, 40.4, 54.3, 107.4, 117.7, 119.3, 129.8, 130.7, 135.8, 137.6, 146.3, 171.8, 172.8, 176.7; IR (CHCl3): 1632, 1594 cm−1; MS (ESI) m/z 531 [M+Cl]−; Anal. Calcd for C26H30BrN3O2: C 62.90, H 6.09, N 8.46, found: C 62.79, H 6.10, N 8.43.

3-(Adamantan-1-yl)-5-(6-bromo-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl)-1,2,4-oxadiadole (10)

A solution of 6-bromo-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (18) (68 mg, 0.2 mmol), HBTU (79 mg, 0.2 mmol), DIPEA (82 μl, 0.47 mmol) and 1-adamantanecarboxamidoxime (46 mg, 0.24 mmol) in DMF (2.4 mL) was kept overnight at room temperature, and then irradiated with MW at 150 °C for 10 minutes. The reaction mixture was poured into water and extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic phase was washed with 1N HCl, water and brine, then it was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and filtered. The residue obtained by solvent evaporation was purified by flash chromatography (eluent: AcOEt, PE, 1/1) to give 9 (80 mg, 80%) as a pure compound: mp 187–188 °C, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ =0.95 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.42–1.43 (m, 4H), 1.82–2.10 (m, 15H), 4.23 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (dd, J1 = 2.0 Hz, J2 = 9.1 Hz), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.67 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ=13.8, 22.2, 27.8, 28.7, 34.4, 36.3, 40.0, 54.2, 106.9, 117.8, 118.9, 129.4, 130.3, 135.63, 137.7, 144.9, 162.0, 171.9, 173.0; IR (CHCl3): 1636 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 497 [M+H]+, 519 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C26H30BrN3O2: C 62.90, H 6.09, N 8.46, found: C 62.78, H 6.10, N 8.48.

General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 5–7, 11–13

A mixture of the 6-bromoderivative (1 eq), DME, Pd(OAc)2 (0.1 eq), Ph3P (0.3 eq), EtOH, 1N Na2CO3 and the appropriate boronic acid (5 eq) was irradiated with MW at 150 °C for 5 minutes, then filtered and diluted with AcOEt. The organic mixture was washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated to dryness. The crude mixture was purified by flash chromatography to afford the target compounds in pure form.

1-(Adamantan-1-yl)-4-[6-(4-(2-propyloxy)phenyl]-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl]-1H-1,2,3-triazole (5)

Yield 86%; mp 83–84 °C; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.89 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.18–1.37 (m, 10H), 1.78–2.30 (m, 15H), 4.26 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.52–4.65 (m, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.73–8.75 (m, 2H), 8,84 (s,1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ=13.9, 22.1, 22.3, 28.8, 29.0, 29.5, 29.7, 36.0, 43.0, 53.9, 59.5, 70.0, 112.5, 116.1, 116.3, 119.4, 124.2, 127.4, 128.1, 130.3, 131.9, 136.4, 137.5, 140.3, 140.8, 157.8, 174.4; IR (CHCl3): 2927, 1632 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 551 [M+H]+, 573 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C35H42N4O2: C 76.33, H 7.69, N 10.17, found: C 76.59, H 7.66, N 10.14.

2-(Adamantan-1-yl)-5-[6-(4-(2-propyloxy)phenyl]-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl]-1,3,4-oxadiadole (6)

Yield 41%, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 1.24 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.34–1.38 (m, 4H), 1.81–2.19 (m, 15H), 4.23 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.58–4.64 (m, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 7.46–7.69-(m, 3H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.77 (s,1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 13.9, 22.1, 22.3, 27.8, 28.8, 29.7, 34.4, 36.4, 40.0, 54.1, 70.0, 116.3, 124.7, 128.1, 128.4, 128.6, 131.0, 131.3, 131.9, 132.0, 132.1, 137.6, 144.4, 158.1, 162.6, 172.3, 173.4; MS (ESI): m/z 484 [M+H]+, 506 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C35H41N3O3: C 76.19, H 7.49, N 7.62, found: C 76.10, H 7.51, N 7.59.

3-(Adamantan-1-yl)-5-[6-(4-(2-propyloxy)phenyl]-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl]-1,2,4-oxadiadole (7)

Yield 58%; mp 215–216 °C; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.87–0.94 (m, 3H). 1.19–1.48 (m, 10H), 1.78–2.07 (m, 15H), 4.2 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 4.52–4.61 (m, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H) 7.58 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.86 (dd, J1 = 2.1 Hz, J2 = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.71 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 13.9, 22.1, 22.3, 28.1, 28.7, 36.6, 40.4, 47.9, 54.2, 70.0, 116.3, 116.4, 125.0, 128.2, 128.7, 131.1, 131.3, 137.4, 137.8, 145.8, 153.2, 158.1, 173.2; IR (CHCl3): 1640, 1614 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 552 [M+H]+, 574 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C35H41N3O3: C 76.19, H 7.49, N 7.62, found: C 76.32, H 7.47, N 7.61.

1-(Adamantan-1-yl)-4-[6-(furan-2-yl)-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl]-1H-1,2,3-triazole (11)

Yield 94%; mp 80–81 °C; 1H-NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0,88 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.18–1.37 (m, 4H), 1.78–2.29 (m, 15H), 4.22 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 6.48 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.72–8.78 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CDCl3) δ=13.9, 22.3, 28.8, 28.9, 29.5, 36.0, 43.0, 53.9, 59.5, 105.8, 111.9, 112.6, 116.1, 119.5, 121.9, 126.8, 127.2, 127.5, 137.6, 140.3, 140.6, 142.5, 153.0, 174.2; IR (CHCl3): 1577, 1461 cm−1; MS (ESI) m/z 483 [M+H]+, 506 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C30H34N4O2: C 74.66, H 7.10, N 11.61, found: C 74.70, H 7.08, N 11.59.

2-(Adamantan-1-yl)-5-[6-(furan-2-yl)-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl]-1H-1,3,4-oxadiadole (12)

Yield 42%; mp 118–120 °C; 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.89 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.34–1.38 (m, 4H), 1.78–2.15 (m, 15H), 4.18 (t, J = 7.3, 2H), 6.50 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.49 (m, 2H), 7.99 (dd, J1 = 1.8 Hz, J2 = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.46 (s, 1H), 8.77 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 13.9, 22.2, 28.1, 28.7, 29.7, 36.4, 36.6, 39.3, 40.4, 54.3, 106.6, 106.9, 112.0, 116.4, 122.5, 126.0, 128.2, 128.7, 137.6, 142.8, 145.8, 152.4, 173.0, 173.1, 176.6; IR (CHCl3): 1637, 1615 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 484 [M+H]+, 506 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C30H33N3O3: C 74.51, H 6.88, N 8.69, found: C 74.38, H 6.90, N 8.70.

3-(Adamantan-1-yl)-5-[6-(furan-2-yl)-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-pentylquinolin-3-yl]-1H-1,2,4-oxadiadole (13)

Yield 65%; mp 234–236 °C, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.88–0.93 (m, 3H), 1.16–1.25 (m, 4H), 1.71–2.10 (m, 15H), 4.21 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.50 (s, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.46 (s, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (s, 1H), 8.73 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 13.9, 22.2, 27.8, 29.7, 36.4, 40.0, 54.1, 106.4, 112.1, 116.4, 122.2, 127.9, 128.1, 128.4, 137.8, 142.8, 144.4, 152.5, 162.5, 173.0, 173.2; IR (CHCl3): 1640, 1614 cm−1. MS (ESI): m/z 484 [M+H]+, 506 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C30H33N3O3: C 74.51, H 6.88, N 8.69, found: C 74.64, H 6.86, N 8.71.

3-Bromo-1-pentylquinolin-2(1H)-one (25) and 3-Bromo-2-(pentyloxy)quinoline (26)

A suspension of 3-bromo-quinolin-2(1H)-one (24) (1.00 g, 4.46 mmol), K2CO3 (1.72 g, 12.48 mmol), 18-crown-6 (1.2 mg, 0.0045 mmol) and pentyl iodide (1.65 mL, 12.48 mmol) in CH3CN (35 mL) was heated overnight at 90 °C then CH3CN was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 and the organic layer was washed with water and brine and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After filtration the solvent was removed and the crude mixture thus obtained was purified by flash chromatography (eluent: PE/AcOEt, 98/2) to give 25 (839 mg, 65%) and 26 (336 mg, 26%) as pure compounds. 25: Red oil; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.84–0.91 (m, 3H), 1.27–1.47 (m, 4H), 1.64–1.76 (m, 2H), 4.23–4.31 (m, 2H), 7.15–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.45–7.59 (m, 2H), 8.06 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 14.0, 22.4, 27.1, 29.1, 44.1, 114.4, 117.6, 120.8, 122.5, 128.3, 130.8, 138.5, 140.5, 158.1; IR (CHCl3): 1647 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 296 [M+H]+, 317 [M+Na]+, 611 [2M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C14H16BrNO: C 57.16; H 5.48; N 4.76, found: C 57.24; H 5.46; N 4.75. 26: Orange oil; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.95 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.25–1.58 (m, 4H), 1.80–1.95 (m, 2H), 4.50 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.24–7.39 (m, 1H), 7.57–7.63 (m, 2H), 7.78–7.82 (m, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 14.1, 22.5, 28.3, 28.5, 67.4, 108.44, 124.6, 126.0, 126.5, 127.1, 130.7, 140.6, 145.3, 157.5; IR (CHCl3): 3020 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 294 [M+H]+; Anal. Calcd for C14H16BrNO C 57.16, H 5.48, N 4.76, found: C 57.13, H 5.50, N 4.75.

1-(Adamantan-1-yl)-4-(1-pentylquinolin-2(1H)-one)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (15)

A suspension of 25 (247 mg, 0.841 mmol), TMSA (291 μL, 1.85 mmol), CuI (32 mg, 0.17 mmol), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (59 mg, 0.084 mmol) and DIPEA (16 mL) in dioxane (16 mL) was irradiated with MW at 120 °C for 10 minutes. The reaction mixture was filtered on Celite, concentrated and treated with 1N HCl. The organic phase was washed with water, brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After filtration, the solvent was removed and the residue was dissolved in a MeOH (15 mL)/THF (15 mL) mixture. K2CO3 was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature. After removal of the solvents, the residue was dissolved in AcOEt and the organic phase was washed with water and brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After filtration and removal of the solvent, 85 mg of the residue, AdN3 (69 mg, 0.39 mmol), CuSO4 (5.6 mg, 0.035 mmol) and sodium ascorbate (6.9 mg, 0.035 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (2 mL) and the corresponding solution was irradiated with MW for 10 minutes at 150 °C. The reaction mixture was poured into water and extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic phase was washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and filtered. After evaporation of the solvent, the residue was purified by flash chromatography (eluent: PE/AcOEt, 4/1) to give 15 (103 mg, 70%) as a pure compound: mp 169 °C; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.89–0.95 (m, 3H), 1.39–1.52 (m, 4H), 1.62–1.87 (m, 9H), 2.17–2.34 (m, 8H), 4.30–4.39 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.34–7.39 (m, 1H), 7.52–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.70–7.74 (m, 1H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.79 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 14.0, 22.5, 27.3, 29.3, 29.5, 36.0, 43.0, 59.6, 114.0, 121.0, 122.3, 129.5, 130.2, 133.9, 138.2, 141.3, 160.1; IR (CHCl3): 1618 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 417 [M+H]+, 439 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C26H32N4O: C 74.97, H 7.74, N 13.45, found: C 75.21, H 7.71, N 13.42.

1-(Adamantan-1-yl)-4-[2-(pentyloxy)quinoline]-1H-1,2,3-triazole (16)

It was prepared starting from 26 according to the procedure used for the preparation of 15: Yield 37%; mp 170 °C, 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.83–0.92 (m, 3H), 1.43–1.62 (m, 4H), 1.75–2.08 (m, 9H), 2.23–2.42 (m, 8H), 4.60 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 7.33–7.41 (m, 1H), 7.55–7.63 (m, 1H), 7.79–7.84 (m, 2H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 9.00 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 14.4, 22.9, 29.1, 29.7, 36.3, 43.3, 59.7, 66.7, 116.0, 120.3, 124.5, 125.5, 127.0, 128.2, 129.5, 135.0, 141.3, 145.8, 158.5; IR (CHCl3): 3018 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 417 [M+H]+, 439 [M+Na]+; Anal. Calcd for C26H32N4O: C 74.97, H 7.74, N 13.45, found: C 74.82, H 7.76, N 13.40.

Ethyl 3-(6-bromo-3-iodo-4-oxoquinolin-1(4H)-yl)propanoate (33)

To a solution of 6-bromo-3-iodoquinolone (1.30 g, 3.7 mmol) in DMF (32 mL) TRITON B (0.8 mL) and ethyl acrilate (4 mL, 37.1 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 90 °C for five hours, then it was cooled down and poured into water. The precipitate was filtered, washed with water and Et2O to give 33 (1.25 g, 75%) as a white solid which was used in the next step without further purification: mp 182–184 °C; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 1.22 (t, J = 6.9, 3H),2.83 (t, J = 6.22, 2H), 4.14 (q, J = 6.9, 2H), 4.41 (t, J = 6.22, 2H), 7.26 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (dd, J1 = 2.3 Hz, J2 = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 8.54 (d, J = 2.3Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 14.1, 33.5, 48.5, 61.6, 116.8, 118.2, 124.9, 130.7, 135.4, 137.5, 148.4, 170.0, 172.9; IR (CHCl3): 1731, 1618 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 452 [M+2H]2+; Anal. Calcd for C14H13BrINO3: C 37.36, H 2.91, N 3.11, found: C 37.44, H 2.91, N 3.10.

Ethyl 3-(6-bromo-4-oxo-3-((trimethylsylil)ethynyl)quinolin-1(4H)-yl)propanoate (30)

To a solution of 33 (100 mg, 0.22 mmol) in dry THF (8 mL) DIPEA (384 μL, 2.2 mmol), CuI (4.2 mg, 0.022 mmol), and PdCl2(PPh3)2 (15.4 mg, 0.022 mmol) were added. The solution was then degassed at room temperature for 10 minutes. During this time, a solution of TMSA (48 μl, 0.34 mmol) in anhydrous THF (3 mL) was also degassed and added dropwise to the first prepared. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h then was filtered through a Celite pad and the filter cake rinsed with EtOAc (10 mL). The filtrate was washed with sat. NH4Cl and brine, then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Filtration and evaporation afforded the crude product which was purified via flash column chromatography (eluent: EtOAc/PE, 1/1) to obtain the target product 30 as a beige solid (90 mg, 97%): mp 144–145 °C; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.23 (s,9H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 2.82 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.40 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J1 = 2.1 Hz, J2 = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (s, 1H), 8.55 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 0.1, 14.1, 33.4, 48.9, 61.5, 98.4, 98.5, 106.8, 117.2, 118.2, 127.6, 129.9, 135.4, 137.1, 147.5, 170.02, 174.9; IR (CHCl3): 2359, 1734, 1622 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 420 [M]+., 422 [M+2H]2+; Anal. Calcd for C19H22BrNO3Si: C 54.29 H 5.28, N 3.33, found: C 54.40, H 5.26, N 3.34.

Ethyl 3-(6-bromo-3-ethynyl-4-oxoquinolin-1(4H)-yl)propanoate (34)

KF (28 mg, 0.48 mmol) was added to a solution of 30 (100 mg, 0.24 mmol) in dry EtOH (7 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h, then was poured onto ice and stirred for 15 min. It was extracted with CH2Cl2, washed with brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Purification of the crude compound by column chromatography (eluent: AcOEt/petroleum ether, 1/1 then 2/1) gave 34 (35 mg, 42%) as a white solid: mp 157–160 °C; 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 1.22 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.23 (s, 1H), 4.12 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.42 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J1 = 2.1 Hz, J2 = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 14.1, 33.3, 48.9, 61.6, 81.3, 106.8, 117.0, 118.3, 127.1, 130.1, 135.6, 137.2, 147.6, 170.1, 179.1; IR (CHCl3): 3310, 2361, 1731, 1621 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 348 [M]+., 350 [M+2H]2+; Anal. Calcd for C16H14BrNO3: C 55.19, H 4.05, N 4.02, found: C 55.04, H 4.06, N 4.03.

Ethyl 3-(6-bromo-3-(1-adamantyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-4-oxoquinolin-1(4H)-yl)propanoate (31)

To a suspension of 34 (50 mg, 0.14 mmol) and AdN3 (27 mg, 0.15 mmol) in t-BuOH (1.5 mL) a solution of CuSO4 (2.2 mg, 0.014 mmol) and sodium ascorbate (2.7 mg, 0.014 mmol) in H2O was added. The reaction mixture was stirred under N2 for 3 days, then it was poured into water, extracted with CH2Cl2 and washed with NH4OH and brine. The organic solution was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the solvent removed in vacuo. The crude compound, purified by column chromatography (eluent: CH2Cl2/MeOH, 98/2) afforded 31 (40 mg, 58%) as a white solid: mp 208–209 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 1.19–1.24 (m, 3H), 1.76 (s, 6H), 2.28 (s, 9H), 2.88 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.13 (dq, J1 = 7.0 Hz, J2 = 1.0 Hz, 2H), 4.55 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.73 (d, J = 9.0 Hz), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 8.89 (s, 1H);13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 14.1, 29.5, 33.7, 36.0, 43.0, 48.9, 59.5, 61.5, 113.6, 117.1, 117.8, 119.5, 128.3, 130.1, 135.0, 137.1, 140.1, 140.7, 169.3, 173.1; IR (CHCl3): 1732, 1630 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z 525 [M]+, 527 [M+2H]2+; Anal. Calcd for C26H29BrN4O3: C 59.43, H 5.56, N 10.66, found: C 59.22, H 5.57, N 10.69.

3-(1-Adamantyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-6-(furan-2-yl)quinolin-4(1H)-one (29)

A mixture of 31 (20 mg, 0.038 mmol), DME (776 μL), Pd(OAc)2 (0.8 mg, 0.0038 mmol), Ph3P (3 mg, 0.011 mmol), EtOH (164 μL), 1N Na2CO3 (100 μL) and 2-furanboronic acid (6.7 mg, 0.057 mmol) was irradiated with MW at 150 °C for 5 minutes, then filtered and diluted with AcOEt. The organic mixture was washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated to dryness. The crude mixture was purified by TLC (eluent: CH2Cl2/MeOH)5/5) to give 29 (10 mg, 63%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3+CD3OD) δ= 1.73 (s, 6H), 2.22 (s, 9H), 6.41–6.43 (m, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.45 (m, 2H), 7.87 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H), 8.64 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3+ CD3OD) δ= 18.6, 29.5, 35.9, 42.9, 59.8, 105.6, 111.9, 118.7, 120.5, 127.1, 127.6, 135.9, 142.4, 153.2, 163.8, 175.4; MS (ESI): m/z 413 [M+H]+; Anal. Calcd for C25H24N4O2: C 72.80, H 5.86, N 13.58, found: C 73.01, H 5.87, N 13.53.

3-(1-Adamantyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-6-(furan-2-yl)-1-(4-hydroxypentyl)quinolin-4(1H)-one (32)

5-(Iodopentan-2-yloxy)(tert-butyl)dimethylsilane (88 mg, 0.268 mmol) was added to a suspension of 29 (40 mg, 0.096 mmol) and K2CO3 (37 mg, 0.096 mmol) in DMF (120 μL). The reaction mixture was stirred at 90 °C for 6 h than was cooled down to room temperature, treated with water and extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic solution was washed with brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Filtration and removal of the solvent under reduced pressure afforded the crude product which was purified by TLC (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 98/2) to give 26 mg of a yellow oil. The alkylated intermediate was dissolved in THF (2 mL) and 1M TBAF in THF (54 μL) was added to the solution. Further 30μL of the reagent were then added after 30 and 60 min. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature, then it was concentrated, diluted with CH2Cl2 and washed with water. The organic phase was then washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated to dryness. The crude compound was purified by analytical TLC to give 32 (3.2 mg, 16%) as a pure compound: 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ=1.19–1.61 (m, 5H), 1.79 (s, 6H), 1.99–2.10 (m, 2H), 2.29 (s, 9H), 3.82–3.91 (m, 2H), 4.28–4.35 (m, 1H), 6.50–6.51 (m, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (m, 1H), 7.56 (s, 1H), 7.95–8.00 (m, 1H), 8.74 (s, 1H), 8.78 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.84 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ= 23.6, 25.1, 25.8, 29.0, 29.5, 35.9, 36.1, 42.9, 59.8, 105.6, 111.9, 118.7, 120.5, 127.1, 127.6, 135.9, 142.4, 154.2, 175.4; MS (ESI): m/z 499 [M]+, 500 [M+H]+; Anal. Calcd for C30H34N4O3: C 72.26, H 6.87, N 11.24, found: C 72.15, H 6.88, N 11.20.

Determination of LogP

Experiments were performed according to the procedure described by Dreassi et al.[64] using the following conditions: Lichrocart 125–4-Lichrospher 100 RP-18 (5 mM) column; mobile phase: MeOH/H2O mixture; flow: 1 mL/min; detector: UV, λ = 254 nm. An Agilent 1100 series liquid chromatograph system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) constituted by a vacuum solvent degassing unit, a binary high-pressure gradient pump, a 1100 series UV detector and a 1100 MSD model VL benchtop mass spectrometer were used. The Agilent 1100 series mass spectra detection (MSD) single-quadrupole instrument was equipped with the orthogonal spray API-ES (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Nitrogen was used as nebulizing and drying gas. The pressure of the nebulizing gas, the flow of the drying gas, the capillary voltage, the fragmentor voltage and the vaporization temperature were set at 40 psi, 9 L/min, 3000 V, 70 V and 350 °C, respectively.

Determination of Solubility

Experiments were performed according to the procedure described by Dreassi et al.[65] using the same HPLC conditions described above.

Preparation of the CB1/CB2-OT Column

The CB1/CB2-OT column was synthesized using a previously described protocol.[46] Briefly, 107 KU812 cells were homogenized in 10 ml of Tris buffer [50 mM, pH 7.5] containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 100 μM benzamidine, 4 μM pepstatin A, 100 μg aprotinin, 100 μg leupeptin, and 1mg PMSF. The homogenate was centrifuged at 700 × g for 5 min and the supernatant was subsequently collected and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was suspended in 2 ml of Tris buffer [50 mM, pH 7.5] containing 2% (w/v) CHAPS, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 100 μM benzamidine, 100 μg aprotinin, 100 μg leupeptin, 1mg PMSF, 4 μM pepstatin A, 10% glycerol and the resulting mixture was rotated at 150 rpm for 18 h at 4°C. The mixture was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 25 min and the supernatant was used for the immobilization onto the open tubular capillary. The open tubular capillary (25 cm × 100 μm i.d.) was primed with 1 M NaOH for 20 min, rinsed with water, and dried at 95 °C for 1 h. A 10% aqueous solution of APTS was passed through the capillary for 5 min followed by a 30 min incubation at 95°C in an oven and the process was repeated. After 18 h, a 1% aqueous solution of gluteraldehyde was passed through the capillary for 1h followed by water and a solution of avidin (25 mM, 5 mg in 2 ml water) was recycled through the capillary for 5 min. Both tips of the capillary were submerged in the avidin solution for 7 days at 4°C. Then a solution of biotin-X (3.5 mM, 5 mg in DMSO:water (3:1 v/v) was run through the capillary for 1 h. The solution containing the solubilized KU812 membranes was recycled through the column for 30 min. The open tubular capillary was then dialysed against Tris buffer [50 mM, pH 7.4] containing 100 NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM EDTA and rotated overnight at 4 °C. The following day, solubilized KU812 membranes were again passed through the capillary for 30 min and the dialysis was repeated.

Chromatographic System and Screening on CB1/CB2-OT Column

The CB1/CB2-OT column was connected to a LC-10AD isocratic HPLC pump (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD, USA). The mobile phase consisted of ammonium acetate [10 mM, pH 7.4]: methanol (90:10, v/v), delivered at a rate of 50 μl/min at room temperature. Detection was accomplished using an on-line scintillation detector (IN/US system, β-ram Model 3, Tampa, FL, USA) with a dwell time of 1 s using Laura Lite 3 software and a 50 μl flow cell with the scintillation flow rate set at 150 μl/min. A series of compounds 7, 9, 10, 11 and 12 were screened on the KU-812 open tubular columns. A 2 mL frontal sample containing 0.25 nM [3H]-Win-55,1212 with a mixture of 10 nM of 4 compounds was carried out as previously described.

Binding Assays

CB1 and CB2 receptor binding assays were performed exactly as described previously,[22,23] using membranes of cells over-expressing the human recombinant CB1 or CB2 receptors.

[35S]GTPγS binding assay

Materials

For the binding experiments, [35S]GTPγS (1250 Ci·mmol−1) was obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences Inc. (Boston, MA, USA), GTPγS from Roche Diagnostic (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and GDP from Sigma-Aldrich. (−)-cis-3-[2-hydroxy-4-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)phenyl]-trans-4-(3-hydroxypropyl)cyclohexanol (CP55940) was purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK).

hCB2-CHO cells

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with human cannabinoid CB2 receptors were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles’s medium nutrient mixture F-12 HAM, supplemented with 1 mM L-glutamine, 10% foetal bovine serum, 0.6% penicillin streptomycin and G418 (400 μg mL−1). Cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in their media and passaged twice a week using non-enzymatic cell dissociation solution.

Membrane preparation

Binding assays with [35S]GTPγS were performed with membranes obtained from hCB2-CHO cells.[50] The hCB2 transfected cells were removed from flasks by scraping, centrifuged at 2500 rpm and then frozen as a pellet at −20 °C until required. Before use in the [35S]GTPγS binding assay, cells were defrosted and diluted in GTPγS binding buffer. Protein assays were performed using a Bio-Rad Dc kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

[35S]GTPγS binding assay

This assay was performed as described previously[49] In detail, the [35S]GTPγS binding assay was carried out with GTPγS binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM Tris-Base, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% BSA) in the presence of [35S]GTPγS (0.1 nM) and GDP (30 μM) in a final volume of 500 μL. Binding was initiated by the addition of hCB2-CHO cell membranes (20 μg protein per well). Nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of 30 μM GTPγS. Compounds under investigation were incubated in the assay for 60 min at 30 oC. The reaction was terminated by a rapid vacuum filtration method using Tris-binding buffer, and the radioactivity was quantified by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

Formalin Test

The experimental procedures applied in the formalin test were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Second University of Naples. Animal care was in compliance with the IASP and European Community guidelines on the use and protection of animals in experimental research (E.C. L358/1 18/12/86). All efforts were made to minimise animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. Formalin injection induces a biphasic stereotypical nocifensive behaviour.[66] Nociceptive responses are divided into an early, short lasting first phase (0–7 min) caused by a primary afferent discharge produced by the stimulus, followed by a quiescent period and then a second, prolonged phase (15–60 min) of tonic pain. Mice received formalin (1.25% in saline, 30 μl) in the dorsal surface of one side of the hind-paw. Each mouse was randomly assigned to one of the experimental groups (n = 8–10) and placed in a Plexiglas cage and allowed to move freely for 15–20 min. A mirror was placed at a 45° angle under the cage to allow full view of the hind-paws. Lifting, favouring, licking, shaking and flinching of the injected paw were recorded as nociceptive responses. The duration of those mentioned noxious behaviours were monitored by an observer blind to the experimental treatment for periods of 0–10 min (early phase) and 20–60 min (late phase) after formalin administration. Results are expressed as means ± s.e.m. Significant differences between groups were evaluated by using analysis of variance followed by the Dunnett’s test. The version of the formalin test we applied is based on the fact that a correlational analysis showed that no single behavioural measure can be a strong predictor of formalin or drug concentrations on spontaneous behaviours.[60] Consistently, we considered that a simple sum of time spent licking plus elevating the paw, or the weighted pain score, is in fact superior to any single (lifting, favouring, licking, shaking and flinching) measure (r ranging from 0.75 to 0.86).[67] Treatments: groups of 8–10 animals per treatment were used with each animal being used for one treatment only. Mice received intraperitoneal vehicle (20% DMSO in 0.9% NaCl) or different doses of before mentioned compounds.

Computational Studies

The simplified molecule models were obtained replacing adamantyl and “quinolone” segments of compounds 11–13 by methyl groups. A total of 8 complexes were then generated placing one water molecule in front of each heteroatom to form a hydrogen bond. Geometries of the complexes between the five-membered ring and water were optimized at the HF/6-311G**++ level of theory, using ab-initio quantum chemistry program GAMESS.[68] Total interaction energies were decomposed via the Kitaura-Morokuma scheme[52] as implemented in the GAMESS program.[68]

Metabolic Studies

In vitro metabolism of compound 11

The basic incubation mixture consisted of 0.5 mg/mL of human liver microsomal protein, a variable concentration of compound 11 (0–300 μM) and phosphate buffer 100 mM, pH 7.4, in a final volume of 0.5 mL. The reaction was started by adding a solution (NADPH-generating system) containing 1 mM NADP+, 4 mM glucose-6-phosphate and 1 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase in 48 mM MgCl2. After 60 min incubation in a shaking water bath at 37 °C, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 ml of acetonitrile and cooling in ice-bath. Blanks containing boiled microsomes were incubated under the same conditions as the drug incubations. After centrifugation at 12000g for 10 min the supernatant was dried under a nitrogen stream, resuspended in 100 μL of acetonitrile and analyzed by HPLC.

HPLC analysis

HPLC analysis was performed on a Shimadzu LC-10AD liquid chromatograph equipped with a Merck LiChroCART 125-4 at a flow rate of 1 ml x min−1. The mobile phase consisted of water:methanol (20/80). Ultraviolet detector (Shimadzu LC-10AV6) was set at 280 nm. The sample was injected by means of a reodyne valve with a 20 μL loop. Calibration curves were obtained by adding different amounts of the analytes to heat-inactivated microsomes. Under the conditions described above retention times for compound 11, 1 (internal standard) and the metabolite, were 13.6, 18.7 and 4.6 min, respectively. The calculated recovery of analytes from the buffer was 91% for 11, 89% for 1 and 80% for the metabolite. The sensitivity limit of the method, taken as the ratio between peak height of compounds and the background noise height ≥ 10 was 2 nmol injected. The relationship between analytes concentration and peak areas ratio versus area of the internal standard was linear up to 300 μM. The metabolite was identified by HPLC-MS analysis (Varian Inc) The analysis were performed in positive mode and ESI parameters were: detector 1650 Volts, drying gas pressure 25.0 psi, desolvation temperature 200.0 °C, nebulizing gas 45.0 psi, needle 5000 V, shield 600 V and capillary 65 V. Nitrogen was used as nebulizer gas and drying gas. Mass spectra were acquired over the scan range m/z 50–1500. Chromatographic analysis was carried out using isocratic elution with eluent A being acetonitrile and eluent B consisting of an aqueous solution of formic acid (0.05%) (80:20 v/v). The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. After elution an aliquot of the eluent (200 μL) was directed to MSD for spectra analysis. The MS spectrum of metabolite was compared with the spectrum obtained from the authentic compound.

Acknowledgments

The authors from CNR, Pozzuoli, are very grateful to Marco Allarà for technical assistance. R. M. and A. R. thank the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging, for financial support. D. B., M. G. C. and R. G. P. thank the NIH for a grant (DA-03672).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Equations used in logP determination and inhibition studies of metabolism of compound 11.

Contributor Information

Dr. Claudia Mugnaini, Email: claudia.mugnaini@unisi.it, Dipartimento Farmaco Chimico Tecnologico, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy. Fax 0039-(0)577-234333.

Stefania Nocerino, Dipartimento Farmaco Chimico Tecnologico, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy. Fax 0039-(0)577-234333.

Valentina Pedani, Dipartimento Farmaco Chimico Tecnologico, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy. Fax 0039-(0)577-234333.

Dr. Serena Pasquini, Dipartimento Farmaco Chimico Tecnologico, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy. Fax 0039-(0)577-234333

Prof. Andrea Tafi, Dipartimento Farmaco Chimico Tecnologico, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy. Fax 0039-(0)577-234333

Maria De Chiaro, Dipartimento di Medicina Sperimentale – Sezione di Farmacologia ‘L. Donatelli’, Seconda Università di Napoli, Via S. Maria di Costantinopoli 16, 80138 Napoli, Italy.

Dr. Luca Bellucci, Dipartimento Farmaco Chimico Tecnologico, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy. Fax 0039-(0)577-234333

Prof. Massimo Valoti, Dipartimento di Neuroscienze, Sezione di Farmacologia, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy

Francesca Guida, Dipartimento di Medicina Sperimentale – Sezione di Farmacologia ‘L. Donatelli’, Seconda Università di Napoli, Via S. Maria di Costantinopoli 16, 80138 Napoli, Italy.

Livio Luongo, Dipartimento di Medicina Sperimentale – Sezione di Farmacologia ‘L. Donatelli’, Seconda Università di Napoli, Via S. Maria di Costantinopoli 16, 80138 Napoli, Italy.

Dr. Stefania Dragoni, Dipartimento di Neuroscienze, Sezione di Farmacologia, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy

Dr. Alessia Ligresti, Endocannabinoid Research Group, Istituto di Chimica Biomolecolare, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Via Campi Flegrei 34, Fabbr. 70, 80078 Pozzuoli (Napoli) Italy

Dr. Avraham Rosenberg, Biomedical Research Center, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA

Dr. Daniele Bolognini, Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZD, UK

Dr. Maria Grazia Cascio, Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZD, UK

Prof. Roger G. Pertwee, Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZD, UK

Dr. Ruin Moaddel, Biomedical Research Center, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA

Prof. Sabatino Maione, Dipartimento di Medicina Sperimentale – Sezione di Farmacologia ‘L. Donatelli’, Seconda Università di Napoli, Via S. Maria di Costantinopoli 16, 80138 Napoli, Italy

Dr. Vincenzo Di Marzo, Endocannabinoid Research Group, Istituto di Chimica Biomolecolare, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Via Campi Flegrei 34, Fabbr. 70, 80078 Pozzuoli (Napoli) Italy

Prof. Federico Corelli, Email: federico.corelli@unisi.it, Dipartimento Farmaco Chimico Tecnologico, Università degli Studi di Siena Via De Gasperi, 2 53100 Siena, Italy. Fax 0039-(0)577-234333.

References

- 1.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pertwee RG. In: Cannabinoids. Pertwee R, editor. Vol. 168. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Alexander SPH, Di Marzo V, Elphick MR, Greasley PJ, Hansen HS, Kunos G, Mackie K, Mechoulam R, Ross RA. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:588–631. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pertwee RG, Ross RA. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:101–121. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pertwee RG. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:397–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiteside GT, Lee GP, Valenzano KJ. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:917–936. doi: 10.2174/092986707780363023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guindon J, Hohmann AG. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:319–334. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand P, Whiteside G, Fowler CJ, Hohmann AG. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pertwee RG. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;36:45–59. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoemaker JL, Seely KA, Reed RL, Crow JP, Prather PL. J Neurochem. 2007;101:87–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sagredo O, García-Arencibia M, de Lago E, Finetti S, Decio A, Fernández-Ruiz J. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;36:82–91. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-0004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pacher P, Hasko G. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:252–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mach F, Montecucco F, Steffens S. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:290–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izzo AA, Camilleri M. Gut. 2008;57:1140–1155. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.148791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idris AI. Drug News Perspect. 2008;21:857–868. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2008.21.10.1314055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guzmán M. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrc1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander A, Smith PF, Rosengren RJ. Cancer Lett. 2009;285:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pisanti S, Bifulco M. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarfaraz S, Adhami VM, Syed DN, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Cancer Res. 2008;68:339–342. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Iwamura H, Suzuki H, Ueda Y, Kaya T, Inaba T. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:420–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lunn CA, Fine JS, Rojas-Triana A, Jackson JV, Fan X, Kung TT, Gonsiorek W, Schwarz MA, Lavey B, Kozlowski JA, Narula SK, Hipkin DJ, Lundell RW, Bober LA. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:780–788. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasquini S, Botta L, Semeraro T, Mugnaini C, Ligresti A, Palazzo E, Maione S, Di Marzo V, Corelli F. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5075–5084. doi: 10.1021/jm800552f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasquini S, Ligresti A, Mugnaini C, Semeraro T, Cicione L, De Rosa M, Guida F, Luongo L, De Chiaro M, Cascio MG, Bolognini D, Marini P, Pertwee R, Maione S, Di Marzo V, Corelli F. J Med Chem. 2010;53:5915–5928. doi: 10.1021/jm100123x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]