Abstract

A new and versatile synthesis of substituted isoquinolines: lithiated o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimines are shown to condense with nitriles to form eneamido anion intermediates that can be trapped in situ with various electrophiles, affording a diverse array of highly substituted isoquinolines, many of which are difficult to access by known methods. Further substitutional diversification can be achieved by modification of the work-up conditions and by subsequent transformations. This method should be useful for the preparation of biological active isoquinolines, such as analogs of the isoquinoline-containing natural product cortistatin A.

Keywords: cyclization, isoquinolines, nitriles, synthetic methods, o-tolualdehyde, tert-butylimines

In the context of a broader program directed toward the synthesis of analogs of the isoquinoline-containing natural product cortistatin A,[1,2] we wished to prepare a diverse array of highly substituted isoquinoline coupling partners, but routes to the complex heterocyclic structures we envisioned were lengthy or impractical using classical[3] or more modern[4–6] methods. Here we report a method for the rapid construction of highly substituted isoquinolines of extraordinary structural versatility that proceeds by the convergent assembly of as few as two or as many as four components in a single operation. Further substitutional diversification can be achieved by modification of the work-up conditions and by subsequent transformations, as detailed below.

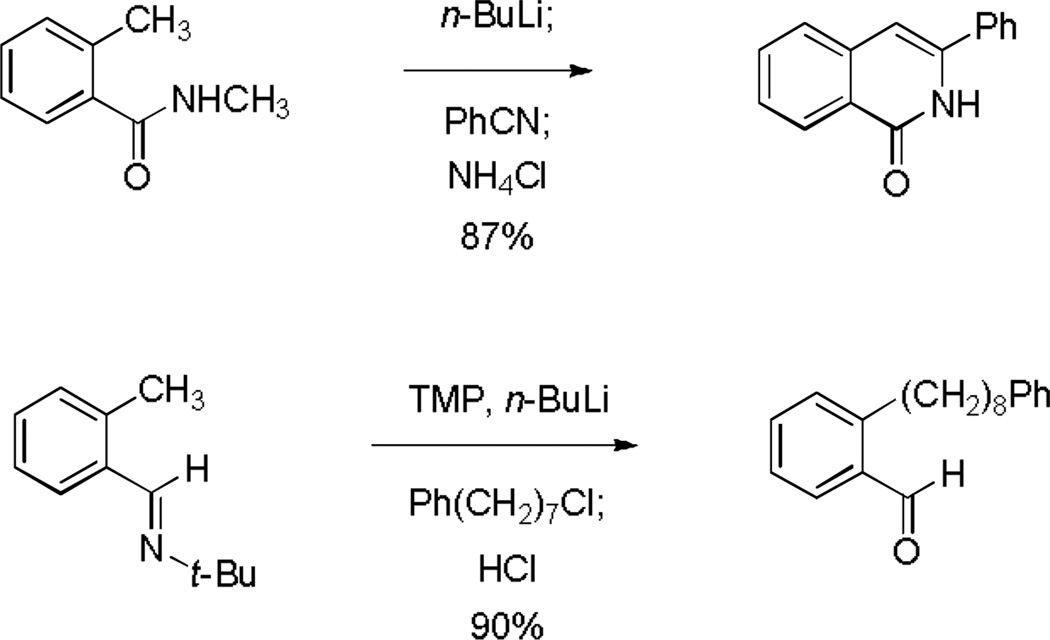

Two important precedents informed the present work. The first was the Poindexter synthesis of 3-substituted isoquinolones, which proceeds by the addition of nitriles to o-tolylbenzamide dianions followed by workup in the presence of ammonium chloride (Scheme 1).[7] The second was the method of Forth and coworkers for the preparation of o-substituted benzaldehyde derivatives by metalation of o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimines followed by alkylation of the resulting anions, then hydrolysis (Scheme 1).[8,9] We imagined and quickly brought to practice the idea that trapping of metalated o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimines with nitriles might provide a highly direct route to 3-substituted isoquinolines. As we will show, the chemistry proved to be much more versatile than we initially imagined, however, by virtue of transformations that ensue subsequent to addition of the nitrile.

Scheme 1.

The Poindexter synthesis of isoquinolines and the method of Forth et al. for metalation-alkylation of o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimine.

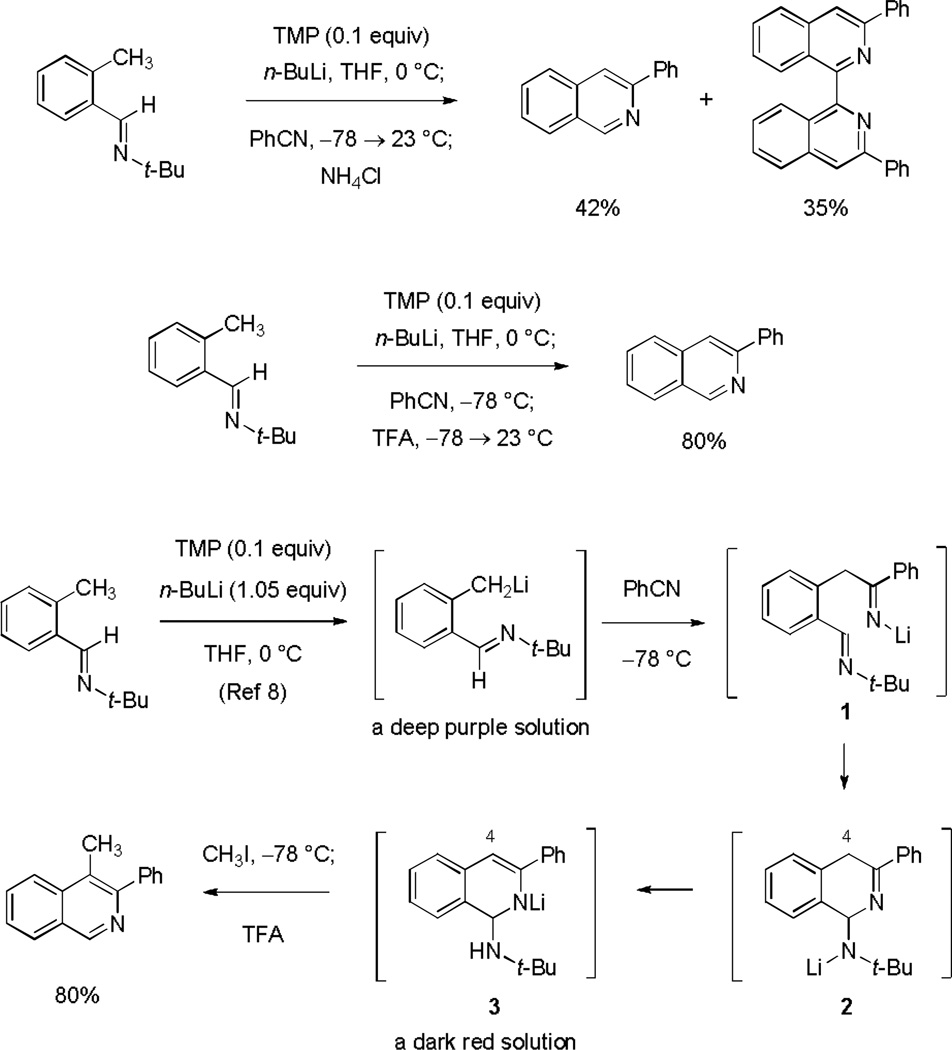

Initial experiments established the feasibility of the proposed construction in a simple system and provided insights for expansion of the methodology. o-Tolualdehyde tert-butylimine was metalated under the conditions specified by Forth and coworkers, using stoichiometric n-butyllithium and a catalytic amount of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine in tetrahydrofuran (THF) at 0 °C for 40 min, forming the corresponding benzyl anion as a deep purple solution, as previously reported.[8] Addition of this anion to a solution of benzonitrile (1.5 equiv) in THF at −78 °C produced a dark red solution within 3 min.[10] Upon warming to 23 °C the reaction mixture became dark brown. Addition of saturated aqueous ammonium chloride followed by extractive isolation and purification by flash-column chromatography provided 3-phenylisoquinoline in 42% yield and, separately, 3,3’-diphenyl-1,1’-biisoquinoline, in 35% yield (Scheme 2). The latter by-product was imagined to arise by base-induced dimerization of 3-phenylisoquinoline followed by oxidation, for which there is some precedent,[11] suggesting that formation of the isoquinoline ring had occurred prior to quenching with ammonium chloride. By adopting a different quenching protocol, addition of excess trifluoroacetic acid at −78 then warming to 23 °C, formation of 3,3’-diphenyl-1,1’-biisoquinoline was avoided and 3-phenylisoquinoline could be isolated in 80% yield. Mechanistically, we considered the imido and tert-butylamido anions 1 and 2, respectively (Scheme 2), to be likely intermediates along the pathway to 3-phenylisoquinoline (although other pathways are possible), but neither species seemed likely to account for the deep red color that we observed upon addition of o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimine anion to benzonitrile. We speculated that the tert-butylamido anion 2 might react further by intra- or intermolecular proton transfer to form an eneamido anion with extended conjugation (3) and this did appear to be a reasonable candidate to account for the red color we observed.[12–14] To test this hypothesis methyl iodide (2 equiv) was added to the deep red solution shortly after its formation at −78 °C, producing an orange solution within minutes. Addition of trifluoroacetic acid after 30 min, also at −78 °C, followed by warming then aqueous workup and purification by flash-column chromatography provided 4-methyl-3-phenylisoquinoline in 80% yield.

Scheme 2.

A method for the direct condensation of o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimines with nitriles to form substituted isoquinolines. The mechanistic pathway depicted accounts for the fact that addition of an alkyl halide subsequent to condensation leads to the formation of 4-alkyl substituted isoquinolines (exemplified by the formation of 4-methyl-3-phenylisoquinoline).

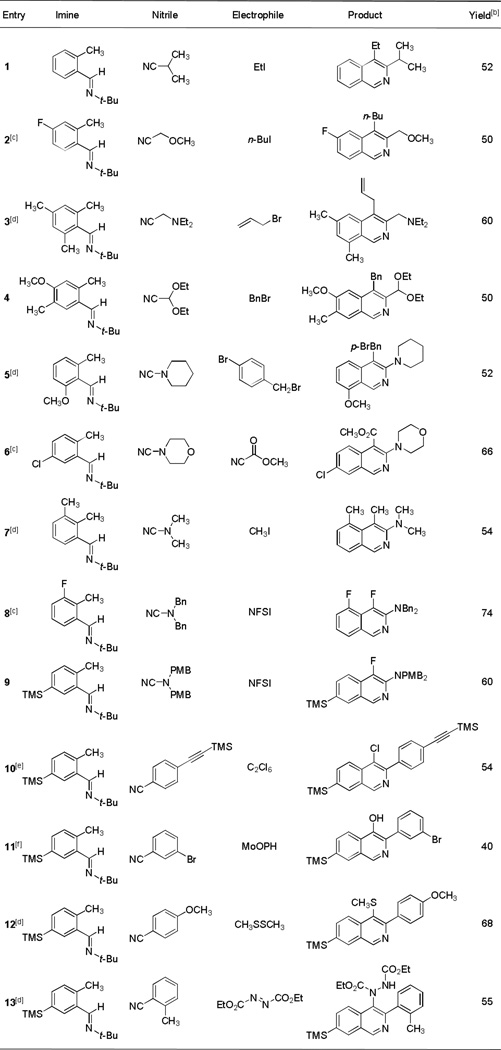

Table 1 depicts a number of examples of polysubstituted isoquinolines that were synthesized by the direct condensation of o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimine anions with different nitriles followed by electrophilic trapping at C4. For metalation of halogenated o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimines the Forth protocol led to decomposition; metalation instead with lithium diisopropylamide (LDA, 1.05 equiv) was effective for these substrates (entries 2, 6 and 8). Entries 1–4 illustrate the use of aliphatic nitriles as substrates and show that a variety of alkyl halides are suitable for C4 alkylation, including ethyl iodide (entry 1), n-butyl iodide (entry 2), allyl bromide (entry 3), and benzyl bromide (entry 4). Although a number of potentially enolizable aliphatic nitriles were successfully employed in this formal [4+2]-cycloaddition reaction, thus far acetonitrile has not proven to be a viable coupling partner, likely because enolization is more rapid than addition to the nitrile.[15] Entries 5–9 illustrate the use of N,N-dialkylcyanamides as substrates; isoquinolines formed from the novel reagent N,N-bis(p-methoxybenzyl)cyanamide in particular have proven to be highly versatile intermediates for further elaboration, as demonstrated below. Also, using N,N-dialkylcyanamides as substrates we have shown that C4 trapping can be successfully acheived with Mander’s reagent,[16] allowing introduction of a C4 carbomethoxy group (entry 6), and that fluorination of C4 is possible by trapping with N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide (limiting reagent, entries 8 and 9). Entries 10–13 exemplify couplings with arylnitriles as substrates as well as trapping reactions for the introduction of other heteroatoms at position C4, including chlorine (using excess hexachloroethane as electrophile, entry 10), oxygen [using oxodiperoxymolybdenum (pyridine)(hexamethylphosphoric triamide), MoOPH, as electrophile,[17,18] and potassium hexamethyldisilazide as a transmetalating reagent, entry 11], sulfur (using methyl disulfide as electrophile, entry 12), and nitrogen (using diethylazodicarboxylate as electrophile, entry 13). In the latter two instances we found that the efficiencies of C4 trapping were enhanced in the presence of the additive hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA, 2 equiv). This additive also proved to enhance the yield of C4-alkylation products in the cases of entries 3, 5, and 7, which we believe is due to acceleration of an otherwise slow proton-transfer reaction that forms the eneamido anion intermediate (in the absence of HMPA C4-unsubstituted isoquinolines were formed as by-products in each of these cases).[21]

Table 1.

Condensation of lithiated o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimines with nitriles followed by trapping at C4 with various electrophiles provides an expedient synthetic route to multiply substituted, structurally diverse isoquinolines.[a]

|

For transformations with enolizable nitriles as substrates (entries 1–4) the nitriles were used as the limiting reagent (1 equiv) and the tert-butylaldimines were used in excess (1.25 equiv); in most other cases the tert-butylaldimine was used as the limiting reagent (1 equiv) and the nitrile was used in excess (1.25–1.5 equiv). Metalation of the tert-butylaldimine was achieved by the method of Forth et al.[8]

Isolated yields based on the limiting reagent. In the fluorinations of entries 8 and 9 the fluorinating agent N-fluorobenzene-sulfonimide (NFSI) was used as the limiting reagent (the tert-butylaldimine was used in excess, 1.25 equiv).

With the halogenated tert-butylaldimine substrates of entries 2, 6, and 8, lithium diisopropylamide (LDA, 1.05 equiv) was used for metalation in lieu of TMP-n-BuLi.

Hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA, 2 equiv) was added prior to the addition of the electrophile.

Electrophilic trapping with hexachloroethane was conducted by addition of the reaction mixture by cannula to a large excess of the electrophile (4 equiv) at −78 °C.

Potassium hexamethyldisilazide (KHMDS, 1 equiv) was added just prior to addition of MoOPH (1.5 equiv).

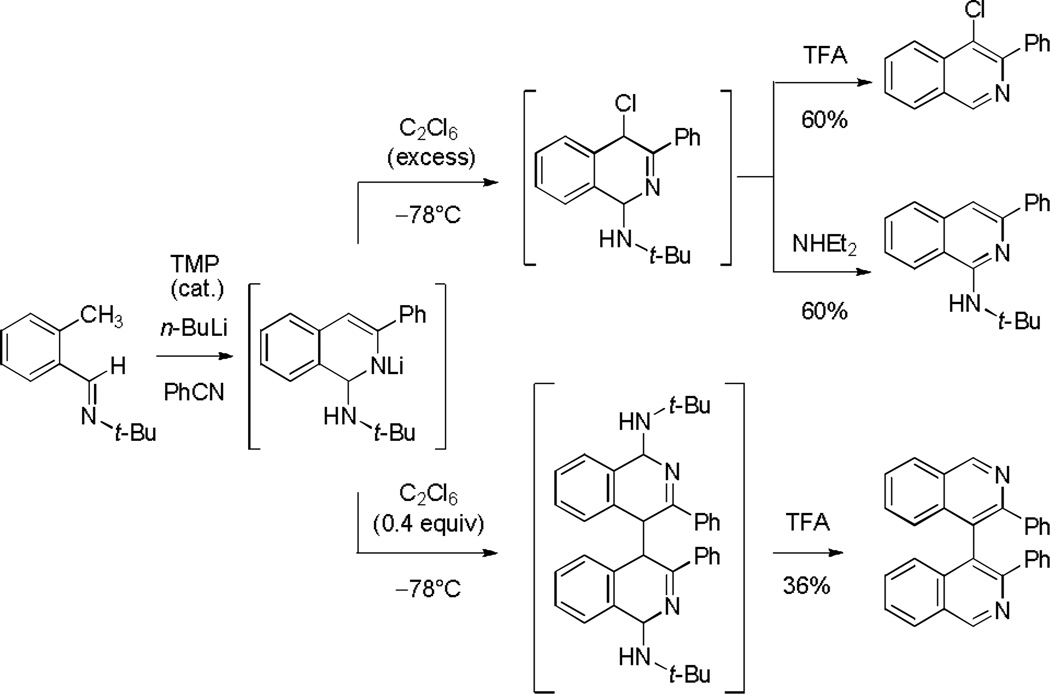

As illustrated in Scheme 3, it proved possible to obtain 4-chloroisoquinolines, 1-tert-butylamino isoquinolines, or 4,4’-biisoquinolines selectively by modification of the protocol for electrophilic trapping with hexachloroethane. Using a deficiency of the electrophile (0.4 equiv, added slowly) a 4,4’-biisoquinoline derivative was formed as the primary product, a transformation that parallels a prior observation reported by Mamane and co-workers.[12b] When instead the putative eneamido anion was quenched by addition to an excess of hexachloroethane (4 equiv) at −78 °C 4,4’-biisoquinoline formation was avoided. Work-up under standard conditions, with trifluoroacetic acid, led to the expected 4-chloroisoquinoline product. Importantly, using an alternative work-up procedure, addition of diethylamine rather than trifluoroacetic acid, elimination of hydrogen chloride occurred, forming a 1-tert-butylamino isoquinoline derivative, which proved valuable for subsequent diversification of C1 (vide infra).

Scheme 3.

Selective preparation of 4-chloroisoquinolines, 1-tert-butylamino isoquinolines, or 4,4’-biisoquinolines by variation of the conditions of C4-trapping with hexachloroethane and subsequent work-up.

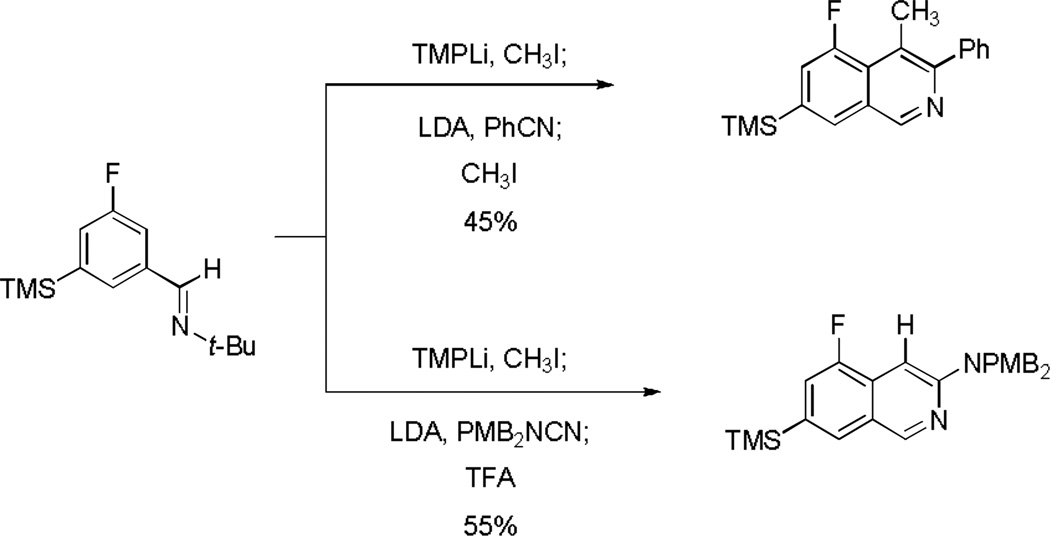

We have also found that with tert-butylaldimine substrates containing a second ortho directing group, such as a 3-fluoro substituent, it is possible to assemble substituted isoquinolines from as many as four components in sequence in a single operation. For example, metalation of 3-fluoro-5-(trimethylsilyl)benzaldehyde tert-butylimine with lithium 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidide (1.05 equiv) initially formed an o-lithio intermediate that was trapped with methyl iodide (0.90 equiv). Subsequent deprotonation of the methylated product in situ with lithium diisopropylamide (1.05 equiv) at −40 °C formed a dark red solution of the presumed o-tolyl anion; addition of benzonitrile, followed by C4-trapping with a second equivalent of methyl iodide afforded 5-fluoro-4-methyl-3-phenyl-7-(trimethylsilyl)isoquinoline in 45% yield. A second example featuring a simpler, three-component assembly is also illustrated in Scheme 4.

Scheme 4.

In substrates with an appropriate o-directing group it is possible to assemble substituted isoquinolines from as many as four components in a single operation.

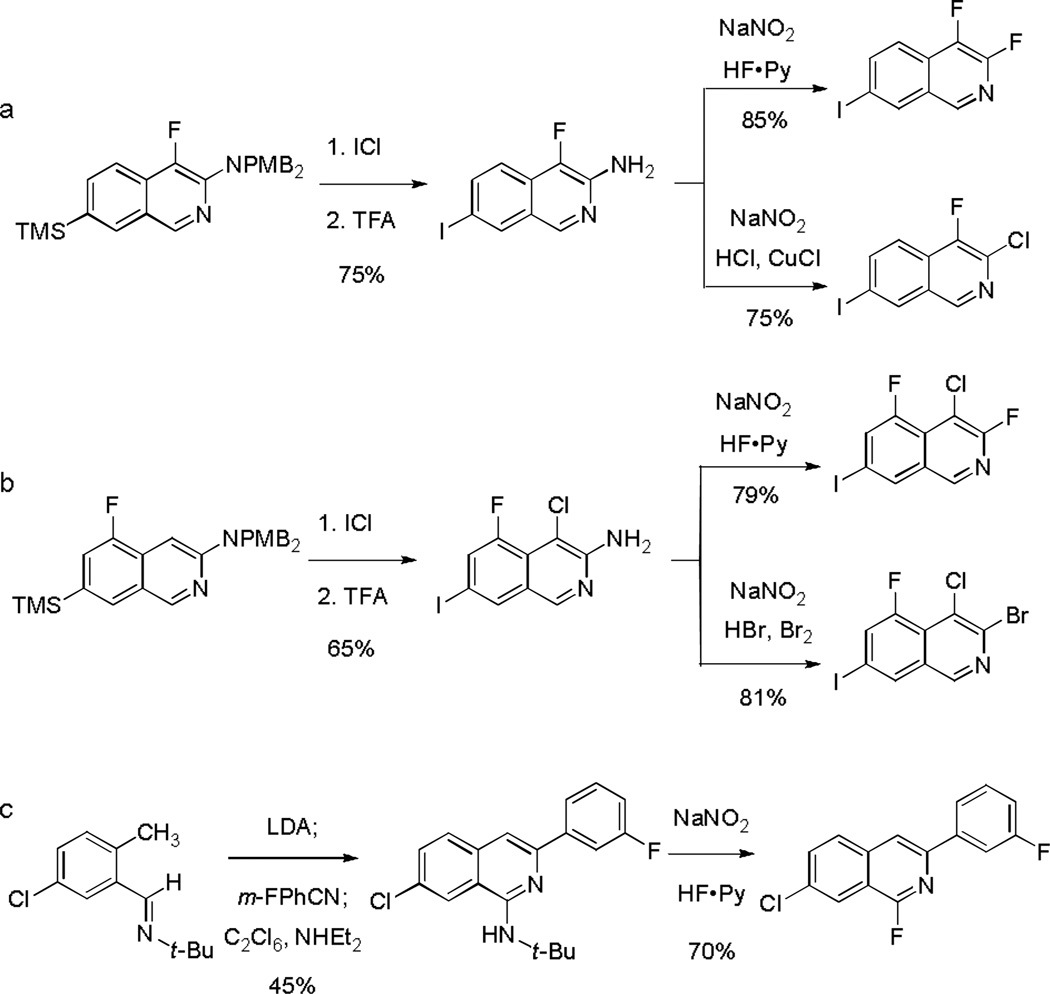

1-tert-Butylaminoisoquinoline (Scheme 3) and 3-N,N-bis(p-methoxybenzyl)aminoisoquinoline derivatives (Table 1, entry 9 and Scheme 4, bottom) were found to be especially valuable intermediates for further diversification, as were 7-trimethylsilylisoquinolines (Table 1, entries 9–13). For example, treatment of 4-fluoro-3-N,N-bis(p-methoxybenzyl)amino-7-(trimethylsilyl)isoquinoline with iodine monochloride in dichloromethane at 0 °C afforded the product of 7-iododesilylation;[22] subsequent addition of trifluoroacetic acid (neat) led to cleavage of the p-methoxybenzyl groups, providing 3-amino-4-fluoro-7-iodoisoquinoline in 75% yield (Scheme 5a). Diazotization of the latter product in the presence of fluoride and chloride sources gave rise to the corresponding 3-haloisoquinoline derivatives in good yield (Scheme 5a). Application of the same sequence to 5-fluoro-3-N,N-bis(p-methoxybenzyl)amino-7-(trimethylsilyl)isoquinoline proceeded with chlorination at C4 (followed by a slower 7-iododesilylation reaction) during initial treatment with iodine monochloride;[23] subsequent transformations proceeded as expected to provide polyhalogenated isoquinolines, including the novel product 3-bromo-4-chloro-5-fluoro-7-iodoisoquinoline (Scheme 5b). Lastly, we observed that 1-tert-butylaminoisoquinoline derivatives (prepared by condensation then chlorination with modified work-up, as discussed above and summarized in Scheme 3) are transformed directly into 1-haloisoquinolines by dealkylative diazotization in the presence of halide ions. Scheme 5c illustrates the synthesis of a 1-fluoroisoquinoline, [24] which we anticipate should allow for further diversification of position C1 by standard nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions.

Scheme 5.

Preparation of halogenated isoquinolines from 1- and 3-aminoisoquinolines obtained by formal [4+2] cycloaddition of o-tolualdehyde tert-butylimine with nitriles.

The direct assembly of substituted isoquinolines and biisoquinolines described herein provides a highly versatile and uniquely enabling methodology for the construction of these important heterocycles.[25]

Footnotes

This research was supported by NIH grant CA-047148, stimulus grant no. CA047148-22S1 and NSF grant CHE-0749566.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org.

References

- 1.a) Aoki S, Watanabe Y, Sanagawa M, Setiawan A, Kotoku N, Kobayashi M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3148–3149. doi: 10.1021/ja057404h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Aoki S, Watanabe Y, Tanabe D, Setiawan A, Arai M, Kobayashi M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:4485–4488. [Google Scholar]; c) Watanabe Y, Aoki S, Tanabe D, Setiawan A, Kobayashi M. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:4074–4079. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flyer AN, Si C, Myers AG. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:886–892. doi: 10.1038/nchem.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Traditional approaches to the synthesis of isoquinolines include the Pormeranz-Fitsch, the Bischler-Napieralski, and the Pictet-Spengler reactions. For reviews, see: Gensler WJ. In: Organic Reactions. Adams R, editor. Vol. 6. New York: Wiley; 1951. pp. 191–206. Whaley WM, Govindachari TR. In: Organic Reactions. Adams R, editor. Vol. 6. New York: Wiley; 1951. pp. 74–150. Whaley WM, Govindachari TR. In: Organic Reactions. Adams R, editor. Vol. 6. New York: Wiley; 1951. pp. 151–190.

- 4.For selected examples of the use of transition-metal-mediated annulation reactions to construct isoquinoline rings, see: Maassarani F, Pfeffer M, Le Borgne G. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1987:565–567. Wu G, Geib S, Rheingold AL, Heck RF. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:3238–3241. Girling IR, Widdowson DA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:4281–4284. Roesch KR, Zhang H, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:5306–5307. Roesch KR, Zhang H, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:8042–8051. doi: 10.1021/jo0105540. Dai G, Zhang H, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:7042–7047. doi: 10.1021/jo026016k. Dai G, Zhang H, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:920–928. doi: 10.1021/jo026294j. Huang Q, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:980–988. doi: 10.1021/jo0261303. Guimond N, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12050–12051. doi: 10.1021/ja904380q.

- 5.For selected examples of the use of electrophilic cyclization reactions to construct isoquinoline rings, see: Huang Q, Hunter JA, Larock, R. C. RC. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2973–2976. doi: 10.1021/ol010136h. Huang Q, Hunter JA, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3437–3444. doi: 10.1021/jo020020e. Fischer D, Tomeba H, Pahadi NK, Patil NT, Yomamoto Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4764–4766. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701392. Movassaghi M, Hill MD. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3485–3488. doi: 10.1021/ol801264u. Fischer D, Tomeba H, Pahadi NK, Patil NT, Huo Z, Yomamoto Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15720–15725. doi: 10.1021/ja805326f.

- 6.For selected examples of the use of aryne annulation, ring expansion, and other reactions to construct isoquinoline rings, see: Gilmore CD, Allan KM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1558–1559. doi: 10.1021/ja0780582. Wang B, Lu B, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Ma D. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2761–2763. doi: 10.1021/ol800900a. Yang Y-Y, Shou W-G, Chen Z-B, Hong D, Wang Y-G. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3928–3930. doi: 10.1021/jo8003259. Sha F, Huang X. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3458–3461. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900212. Chiba S, Xu Y, Wang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12886–12887. doi: 10.1021/ja9049564.

- 7.Poindexter GS. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:3787–3788. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forth MA, Mitchell MB, Smith SAC, Gombatz K, Snyder L. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:2616–2619. [Google Scholar]

- 9.N-Cyclohexyl aldimines have also been used to direct ortho-metalation: Ziegler FE, Fowler KW. J. Org. Chem. 1976;41:1564–1566. Flippin LA, Muchowski JM, Carter DS. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:2463–2467.

- 10.Interestingly, in his synthesis of isoquinolones Poindexter reports that addition of benzonitrile to dilithiated o-tolyl N-methylbenzamide affords a deep red solution. In this work it is proposed that cyclization does not occur prior to work-up with ammonium chloride, cf. Ref. [7]

- 11.Clarke JE, McNamara S, Meth-Cohn O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974;27:2373–2376. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Addition of alkyllithium reagents to C1 of isoquinolines is known to produce an adduct that can be trapped at C4 (in reference b it is shown that trapping with hexachloroethane affords a 4,4’-biisoquinoline): Alexakis A, Amiot F. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2002;13:2117–2122. Louërat F, Fort Y, Mamane V. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:5716–5718.

- 13.3,4-dihydro-l(2H)-isoquinolones have been synthesized by the condensation of N,N-diethyl-o-toluamide anions with aldimines. Lithiation (and subsequent trapping) of the benzylic position was reported in this study: Clark RD, Jahangir J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:5378–5382.

- 14.An alternative sequencing of steps is feasible; e.g., tautomerization of intermediate 1 may occur prior to ring closure to form 3. We thank a referee for suggesting this.

- 15.Poindexter had also noted that acetonitrile was not a suitable substrate in his method for isoquinolone formation, cf. Ref. [7]

- 16.Crabtree SR, Alex Chu WL, Mander LN. Synlett. 1990:169–170. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vedejs E, Engler DA, Telschow JE. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:188–196. [Google Scholar]

- 18.In preliminary experiments, dioxygen (cf. Ref. [19]) and N-sulfonyl oxaziridines (cf. Ref. [20]) were found not to be effective C4 trapping agents.

- 19.Parker KA, Koziski KA. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:674–676. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis FA, Mancinelig PA, Balasubramanian K, Nadir UK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:1044–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The putative eneamide anion intermediates of Table 1 ranged in color from dark red to dark orange. In the cases of entries 3, 5, and 7, where proton transfer to form the eneamide intermediate is believed to be slow, addition of HMPA caused a noticeable darkening of the red or orange solutions.

- 22.Stock LM, Spector AR. J. Org. Chem. 1963;28:3272–3274. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iodine monochloride is known to chlorinate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, see: Turner DE, O'Malley RF, Sardella DJ, Barinelli LS, Kaul P. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:7335–7340.

- 24.In contrast, the transformation of isoquinolones to 1-fluoroisoquinolines can be low yielding, see: Zhu G-D, Gong J, Claiborne A, Woods KW, Gandhi VB, Thomas S, Luo Y, Liu X, Shi Y, Guan R, Magnone SR, Klinghofer V, Johnson EF, Bouska J, Shoemaker A, Oleksijew A, Stoll VS, Jong RD, Oltersdorf T, Li Q, Rosenberg SH, Giranda VL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3150–3155. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.041.

- 25.Examples of medicinally important isoquinolines are papaverine (cf. Ref. [26]), which is used for multiple indications to improve blood flow, fasudil (cf. Ref. [27]), which is approved for the treatment of cerebral vasospasm in Japan, and BMS-650032 (cf. Ref. [28]) and MK-1220 (cf. Ref. [29]), candidates for the treatment of hepatitis C.

- 26.Poch G, Kukovetz WR. Life Science. 1971;10:133–144. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(71)90086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a) Asano T, Suzuki T, Tsuchiya M, Satoh S, Ikegaki I, Shibuya M, Suzuki Y, Hidaka H. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;98:1091–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ono-Saito N, Niki I, Hidaka H. Phamacol. Ther. 1999;82:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasquinelli C, Eley T, Villegas C, Sandy K, Mathias E, Wendelburg P, Liao S, McPhee F, Scola PM, Sun LQ, Marbury TC, Lawitz E, Goldwater R, Rodriguez-Torres M, DeMicco MP, Ababa M, Wright D, Charlton M, Kraft WK, Lopez-Talavera JC, Grasela DM. Hepatology. 2009;50:411A. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudd MT, McCauley JA, Butcher JW, Romano JJ, McIntyre CJ, Nguyen KT, Gilbert KF, Bush KJ, Holloway MK, Swestock J, Wan B, Carroll SS, Dimuzio JM, Graham DJ, Ludmerer SW, Stahlhut MW, Fandozzi CM, Trainor N, Olsen DB, Vacca JP, Liverton NJ. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:207–212. doi: 10.1021/ml1002426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]