Abstract

This paper reports the synthesis of novel ring-expanded bryostatin analogues. By carefully modifying the substrate, a selective and high-yielding Ru-catalyzed tandem enyne coupling/Michael addition was employed to construct the northern fragment. A ring-closing metathesis was utilized to form the 31-membered macrocycle of the analogue. These ring-expanded bryostatin analogues possess anticancer activity against several cancer cell lines. Given the difficulty of forming the C16-17 olefin in the late stage, we also describe our development of a new-generation strategy to access the C7-C27 fragment containing both the B- and C-ring subunits.

Keywords: bryostatin, Ru catalysis, ring-closing metathesis, tandem reaction, Pd catalysis

Introduction

In the previous papers, we described our development of chemoselective and atom-economical methods for stereoselective assembly of bryostatin A-, B- and C-ring subunits (Figure 1). Consequently, efforts have been undertaken toward total synthesis of the bryostatins by taking advantage of these methods.[1] In this article, we report a full account of our synthesis and biological evaluation of two novel ring-expanded bryostatin analogues using the ring-closing metathesis (RCM) as the macrocyclization method. Given the difficulty of forming the C16-17 olefin in the late stage, we also describe the development of a new-generation strategy to access the C7-C27 fragment containing the B- and C-ring subunits.

Figure 1.

Stereoselective assembly of bryostatin A-, B- and C-ring subunits.

Results and Discussion

I. Synthesis of Two Ring-Expanded Bryostatin Analogues

Retrosynthetic Analysis

The 26-membered macrolactone embedded in the bryostatins presents a significant synthetic challenge.[2] All three previously reported total syntheses relied upon a Julia olefination to unite a southern and a northern hemisphere followed by a macrolactonization to close the macrocycle.[3–6] However, due to the basic nature of the Julia olefination reaction, the two exo-cyclic α,β-unsaturated enoates had to be masked and revealed after macrocyclization, resulting in lengthy syntheses (> 40 longest linear steps and >70 total steps).

In the two proceeding articles, we described our efforts on the development of atom-economic transformations for the synthesis of A-, B- and C-ring subunits of the bryostatins. Importantly, a high degree of stereocontrol of the exocyclic methyl enoate geometry was achieved, which is mechanism-based. However, utilization of these methodologies for the total synthesis of bryostatins necessitates a more chemoselective strategy for the macrocycle synthesis due to the sensitive nature of exocyclic methyl enoate towards both acids and bases. The impressive progress of RCM in organic synthesis and the mildness of the reaction conditions prompted us to evaluate its use for our bryostatin total synthesis (Scheme 1).[7]

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis.

We envisioned that the 26-membered macrocycle of 1 could be formed by a RCM reaction from a diene precursor 10, which can be synthesized from two fragments, 11 and 12, via esterification. Southern fragment 12 containing the C-ring subunit could be accessed from dihydropyran 5.[8] Northern fragment 11 could be prepared from protected polyol 13, and synthesis of the B-ring in 13 would ultimately come from a Ru-catalyzed tandem alkyne-enone coupling/Michael addition reaction[9] between alkene 14 and alkyne 7. The feasibility of such a transformation has been previously established in a model system (eq 1), albeit with a low yield and diastereoselectivity likely caused by the liability of the cyclopentanone ketal and the presence of two terminal olefins in 6. We anticipated that the nature of protecting groups in the alkene partner 14 would have an impact on the outcome of the Ru-catalyzed tandem coupling reaction. Thus, alkene 14a with a more robust acetonide moiety was chosen as an initial coupling partner.

|

(1) |

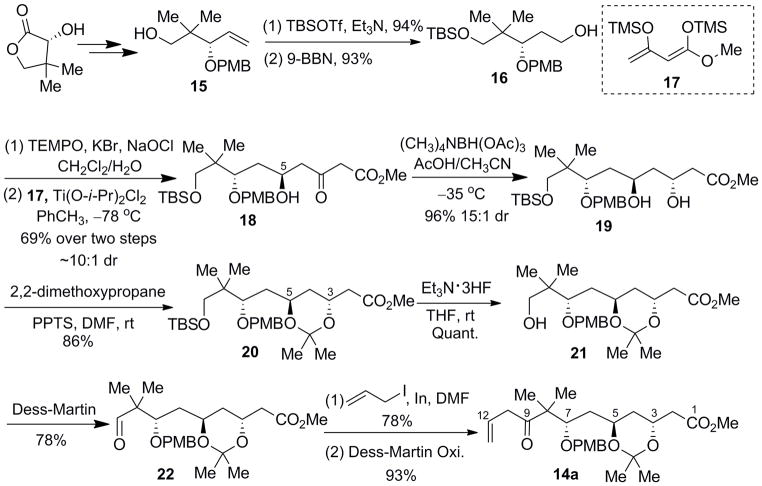

Synthesis of the Northern C1-C16 Fragment

Our synthesis (Scheme 2) commenced with (R)-pantolactone, which was converted to alcohol 15 in 5 steps (exhaustive reduction with LAH, selective protection of the C7, C9 diols as a 4-methoxylbenzaldehyde acetal, TEMPO-catalyzed oxidation[10] of the C5 alcohol, Wittig olefination, and DIBAL-H reduction) following a procedure from White and Mukaiyama.[11,12] TBS protection of 15 followed by hydroboration/oxidation furnished the desired alcohol in high yield (90% overall). Oxidation of alcohol 16 was best accomplished by using TEMPO-catalyzed oxidation with bleach. The crude aldehyde was used without purification in the Ti(Oi-Pr)2Cl2-mediated Mukaiyama aldol reaction with bis(trimethylsilyl) dienol ether 17 to give secondary alcohol 18 in 68% yield over two steps as a ~10:1 diastereomeric mixture at C5. The stereochemical assignment of the newly formed C5-hydroxyl group (bryostatin numbering) was based upon similar precedent reported by Evans.[13] Subsequent hydroxyl-directed anti-reduction[14] (Me4NBH(OAc)3, AcOH/CH3CN, −35 °C) set the C3 stereochemistry with excellent yield (96%) and diastereoselectivity (ca. 15:1).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 14a.

To move forward, the C3 and C5 hydroxyl groups were protected as an acetonide, and the TBS group was removed with triethylamine-HF. Upon oxidation of the resultant neopentyl alcohol, the stage was set for allylation of aldehyde 22. A variety of allylation reagents, such as allylmagnesium chloride, allylzinc bromide, and B-allyl-9-BBN, gave a complex mixture due to the sensitivity of the aldehyde, while tetraallyl tin[15] gave no reaction. On the other hand, indium-mediated allylation[16] with allyl iodide (DMF, room temperature) provided a satisfactory 78% yield of the corresponding secondary alcohols as a 1:1 diastereomeric mixture at C9. The diastereoselectivity of this process is inconsequential as this stereocenter is subsequently obliterated. Interestingly, replacing allyl iodide with allyl bromide gave no reaction, even with the aid of sonication. Subsequent oxidation (Dess-Martin periodinane, NaHCO3, CH2Cl2) resulted in β,γ-enone 14a.

With enone 14a in hand, the Ru-catalyzed tandem coupling reaction of 7 with 14a was then investigated (eq 2). Unfortunately, the reaction provided a complicated mixture and no desired coupling product was obtained. Nevertheless, we were able to identify an apparent signal at 6.69 ppm (CDCl3, dt, J = 10.5, 17.0 Hz) in the crude 1H NMR, which indicated the formation of trans-α,β-unsaturated ester during the reaction.

|

(2) |

This result was in striking contrast to our preliminary model studies. We hypothesize that coordination of the C3-oxygen in 14a with the cationic Ru species activated it towards β-alkoxy-elimination (Figure 2). The C5-oxygen could consequently get deprotected and then participate in other reactions, such as formation of a hemiketal. If this hypothesis was correct, removal of the ester group should alleviate the β-alkoxy-elimination pathway.

Figure 2.

To this end, the synthesis of a new β,γ-enone 14b was pursued (Scheme 3). Methyl ester 20 was converted to alcohol 24 via a straightforward three-step transformation (LAH reduction, deprotection of the TBS ether, and selective protection of the C1-hydroxyl group with TBDPSCl). The β,γ-enone was installed in three steps as previously described (Dess-Martin oxidation, indium-mediated allylation, and Dess-Martin oxidation) to furnish 14b.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 14b.

Treatment of 14b and alkyne 7 with [CpRu(CH3CN)3]PF6 under the optimized conditions (0.4 M in acetone, 40 h), to our delight, indeed gave the desired dihydropyran 25, although the yield was low (21%, eq 3).

|

(3) |

It is likely that the problem was caused by the acid sensitivity of the acetonide in 14a and 14b, which could be enhanced by the presence of the C9 ketone moiety. For example, the deprotected C5 alcohol could undergo cyclization to form a hemi-ketal. To overcome this issue, a new enone 14c was proposed (Figure 3). Both the lactone and the TBDPS ether moieties in 14c were expected to be stable under the reaction conditions. Furthermore, the lactone protected both the C5-hydroxyl group and C1-ester, thus minimizing protecting group manipulations.

Figure 3.

A new enone substrate.

The synthesis of enone 14c is outlined in Scheme 4. Starting from diol 19, the two hydroxyl groups at C3 and C5 were differentiated by lactonization, which was best achieved with Otera’s catalyst 26.[17] Use of PPTS gave inferior results in terms of both the yield and the conversion. Protection of the C3 alcohol (TBDPSCl, DMF, imidazole) required heating (50 °C) while no reaction was observed at room temperature. The primary TBS ether in lactone 28 was selectively deprotected with aqueous acetic acid (80%, 4:1 v/v) to give alcohol 29 in good yield (69% – 80%). The β,γ-enone functionality was installed as previous described without incident to give the desired enone 14c in good overall yield (85% over three steps).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of 14c.

With enone 14c in hand, the crucial Ru-catalyzed tandem coupling was investigated (Scheme 5). To our delight, the reaction went smoothly, delivering tetrahydropyran 30 in 56% yield as a 9:1 cis : trans diastereomeric mixture. The appearance of a singlet at 5.45 ppm (minor) and 5.38 ppm (major) and the incorporation of two PMB groups in 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) suggested a successful coupling. This was later confirmed by 13C NMR and elemental analysis. Assignment of the 5.38 ppm signal (belonging to the vinylsilane proton) as the cis-isomer was based on the previous model studies and later confirmed by 2D NMR experiments on late stage compounds. Furthermore, we were able to reduce the ratio of enone : alkyne to 2.2:1 and recover 1.2 equiv. of 14c, and up to 5.5 g of 30 was synthesized. Thwarted by acid-mediated protodesilylation of the vinylsilane moiety, compound 30 was brominated with NBS in DMF and then deprotected using BF3•Et2O and 1, 3-propanedithiol in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C to give diol 31. Shift of the vinyl proton resonance from 5.38 to 6.04 ppm, disappearance of both PMB groups in 1H NMR, and appearance of a broad peak at 3436 cm−1 in IR supported the structural assignment. Furthermore, the incorporation of a bromine atom into the molecule was confirmed by mass spectroscopy. Diol 31 was subsequently subjected to a tandem methanolysis/ketalization reaction with PPTS in refluxing CH3OH/CH(OCH3)3 to afford methyl ketal 32 with both A- and B-rings installed.[18] The assignment of C9-methyl ketal stereochemistry was based on a similar literature precedent.[4a]

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of the C1-C16 fragment.

At this point, the remaining task was to acetylate the C7-hydroxyl, hydrolyze the C1-methyl ester, and install a terminal olefin at C16. To this end, the C7-hydroxyl was selectively acetylated in two steps involving the temporary protection of the C16-hydroxyl with TES ether, one-pot acetylation of the C7-hydroxyl, and deprotection of the C16-hydroxyl to give compound 33. The resultant alcohol was then oxidized (Moffatt-Swern oxidation) and olefinated (Wittig olefination) to afford the terminal alkene 34 in 63% yield over two steps. Surprisingly, saponification of the methyl ester in 34 was troublesome; for example, use of LiOH in aqueous THF or n-PrSLi in HMPA[19] only gave a complex mixture. It was eventually found that the use of (CH3)3SnOH[20] gave acid 35 in 45–64% yield together with 10–15% of recovered methyl ester 34. A large excess of (CH3)3SnOH (15 equiv) and heating under microwave conditions were required for achieving high conversion. Pd-catalyzed carbonylation[21] of acid 35 with Pd(PPh3)4 in DMF/CH3OH furnished the requisite α,β-unsaturated methyl ester 36 in 55% yield. Note that both acids 35 and 36 could be used as a RCM precursor. But, use of vinyl bromide 35 as a RCM precursor could be advantageous because in principle it allows late-stage diversifications through cross-coupling reactions to provide novel bryostatin analogues.

Synthesis of the Southern C17-C27 Fragment

The synthesis commenced with tetrahydropyran 3 that was prepared in 5 or 6 steps from terminal alkyne 8 and ynoate 9 (see Part I). The removal of the C17-TBS ether in 3 was best effected by using Et3N•3HF in THF (60–77% yield, ca 10% of the recovered 3) (Scheme 6). Excess reagents (15 equiv of Et3N•3HF) and long reaction time (12 h) were necessary to achieve reasonable conversion of 3.[22] Other deprotection methods, such as TBAF, TBAF buffered with acetic acid, HF in pyridine, and aqueous HF in acetonitrile, gave inferior results. After oxidation of the C17-hydroxyl to the corresponding aldehyde, the stage was set for the introduction of a double bond at C17. This transformation turned out to be non-trivial, and almost all the classical olefination methods failed (see Table 1), likely caused by the neopentyl nature of the aldehyde and sensitivity of the dihydropyran core towards bases. Eventually, employment of Cp2Ti(CH3)2 (Petasis reagent)[23] as the olefination reagent solved the problem, and the terminal alkene 39 was obtained in 58% yield (70% based on recovered starting material, entry 7). Under the reaction conditions, a by-product derived from olefination of one of the ester groups was observed (5–10% yield). Cleavage of the acetonide with 75% aqueous acetic acid, followed by selective protection of the C26-hydroxyl with the TES group furnished the fully functionalized southern fragment 40 in 52% yield over two steps.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of the C17-C27 fragment 40.

Table 1.

Olefination of 38.

| Entry | Conditions | Observation | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ph3P=CH2, −30 °C–0 °C | an unkown byproduct | 0 |

| 2 | CH2I2, Zn, Me3Al, 25 °C | mainly 38 | trace |

| 3 | CH2I2, Zn, PbI2, TiCl4, 0 °C–25 °C | decomposition of 38 | 0 |

| 4 | TMSCH2CeCl2, THF, −78 °C | Only 38 | 0 |

| 5 | CH2I2, Zn, Me3Al, BF3•OEt2, 25 °C | 38 + decomposition | 0 |

| 6 |

|

38 + decomposition | 0 |

| 7 | Cp2Ti(CH3)2 | 39 + a byproduct from ester olefination | 58% |

|

(4) |

The stereochemistry of tetrahydropyran 40 was confirmed by ROESY experiment (Figure 4). The selectivity for the mono-TES protection was predicted according to the literature precedent [4a] and confirmed by 2D NMR experiments.

Figure 4.

Key ROESY correlations observed for 40.

Investigation of the Ring-Closing Metathesis Approach

With acid 36 and alcohol 40 in hand, the stage was set for their union. Initial efforts with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) as the coupling reagent were plagued by the formation of two inseparable products in a 1:1 ratio, one of which was later identified as the desired ester 42. No efforts were made to identify the other product. The most satisfactory results were obtained by employing the 2-methyl-6-nitrobenzoic anhydride (MNBA) method developed by Shiina.[24] Ester 42 was isolated in around 60% yield with the majority of the excess alcohol 40 recovered.[25] In addition, under the same esterification conditions, acid 35 was also coupled with alcohol 40 to give ester 41 in a similar yield.

Consequently, the RCM reaction of both esters 41 and 42 were investigated. Our initial attempts were carried out with the Grubbs-Hoveyda catalyst 45[26] or the pseudohalide catalyst 46 [27] in either refluxing CH2Cl2 or benzene. Unfortunately, these reactions were sluggish. Prolonged heating (> 12 h) was required for the conversion of either 41 or 42, even in refluxing benzene. Furthermore, the isolated major product was much more polar than the corresponding starting materials. That the polar product could be a dimer was supported by 1H NMR analysis: the double bond at C16 disappeared while the one at C17 remained intact. Based upon these observations, a possible explanation for the failure of the RCM reaction is outlined in Scheme 8. Both terminal double bonds at C16 and C17 are deactivated towards Ru-alkylidene formation due to the unfavorable steric and electronic factors. At elevated temperature, the Ru-alkylidene selectively initiated attack on the C16 double bond. Since the C17 double bond has very low reactivity, presumably due to steric congestion, intermediate 43 preferred to react with another molecule of 42 to form a dimer even at a very low substrate concentration (~0.0005 M). Concurrently, a similar observation was also reported by Thomas and co-workers during their investigation of a RCM approach towards the bryostatins.[28]

Scheme 8.

Unsuccessful RCM: a possible explanation.

It was anticipated that the conformation of the RCM precursor would have a dramatic impact on the RCM efficiency. The X-ray crystal structure of bryostatin 1 (Figure 5)[2a] clearly showed that the C3-OH group helps to organize the macrocycle by serving as a hydrogen bonding acceptor for the C19 lactol hydroxyl (O-H-O bond length of 2.71 Å) and donors for both C5 and C11 pyran oxygens (O-H-O bond length of 3.00 and 2.84 Å, respectively). If this holds true for the immediate RCM precursor, one would expect that a free hydroxyl group at C3 in either 41 or 42 would facilitate the RCM reaction by bringing two terminal olefins together. Therefore, deprotection of the TBDPS ether at C3 was undertaken (eq 5). Unfortunately, only a complex mixture was obtained under the three reaction conditions attempted (TBAF, HF in pyridine, and NH4F in CH3OH). To circumvent this problem, it was decided to deprotect the TBDPS group at an earlier stage of the synthesis.

Figure 5.

X-ray crystal structure of bryostatin 1 from ref 2a.

|

(5) |

Treatment of vinyl bromide 34 led to a smooth deprotection of the C3-TBDPS ether to give alcohol 47 in 82% yield (Scheme 9). In contrast to the hydrolysis of methyl ester 34 (Scheme 5, 45–50% yield with 15 equivalents of (CH3)3SnOH, 140 °C, microwave, 1.5 h), the saponification of 47 was much more facile. Under the identical reaction conditions, the reaction went to completion in 40 minutes to deliver the hydroxyacid 48 in 86% yield. Presumably, the hydrolysis of the C1-methyl ester was facilitated by precoordination (or complexation) of the C3-hydroxyl with (CH3)3SnOH.[29] Next, carbonylation of the vinyl bromide moiety followed by selective protection of the C3-hydroxyl (TESOTf, DCM, 0 °C) converted 49 to acid 50, which was subsequently acylated with alcohol 40 to give ester 51. Deprotection of both TES groups at C3 and C26 with PPTS in aqueous THF provided diol 52, the structure of which was fully determined by COSY, ROESY, HSQC, and HMBC experiments.

Scheme 9.

Unfortunately, when 52 was subjected to RCM reactions in the presence of the Grubbs-Hoveyda catalyst 45, no reaction was observed in refluxing CH2Cl2 while refluxing in benzene only led to decomposition. It was evident from these studies that the low reactivity of the double bond at C17 was the source of the problem. Thus, we decided to initiate the ruthenium alkylidene formation onto the C17 double bond via relay ring-closing metathesis (RRCM).[30] If this could be accomplished, it was anticipated that the resulting ruthenium alkylidene 55 would cyclize onto the C16 double bond to form macrocycle 53 (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10.

Relay ring-closing metathesis: a possible solution.

A RRCM Strategy

Although direct installation of a relay moiety onto the southern hemisphere via Takai olefination[31] (eq 6) or olefin cross-metathesis[32] (eq 7) was difficult (eq 6 and 7), this problem was solved with a two-step procedure: a Takai olefination of aldehyde 38 with iodoform[33] followed by a Negishi cross coupling[34] gave 60 (Scheme 11). The quality of CrCl2 was crucial for the Takai olefination reaction, and high chromium loading (~15 equiv) was necessary for full conversion of the starting material.[35] The yield (26%, 47% based on the recovered starting material) was moderate likely due to the steric congestion around the aldehyde. Subsequent deprotection (80% aqueous AcOH) followed by selective TES protection (TESCl, DMF, Et3N, 0 °C to rt) converted 62 to mono-TES ether 63, which was then acetylated with the northern hemisphere segment 50 to give RRCM precursor 64 in 51% yield. The structure of compound 64 was determined by 1H, 13C, 2D NMR experiments. In particular, the observed ROESY correlations confirmed our previous stereochemical assignment for the A-, B-, and C-rings (Figure 6).

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of precursor 64 for relay ring-closing metathesis.

Figure 6.

Key ROESY correlations observed for 64.

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

With polyolefin 64 in hand, the RRCM was next investigated (eq 8). To avoid the undesired dimerization, a solution of 64 was added in a dropwise fashion via a syringe pump to a solution of the Grubbs-Hoveyda catalyst 45 (18 mol%) in benzene at 50 °C and then the bath temperature was raised to 80 °C. The starting material disappeared within one hour (entry 1). No RRCM product was observed. Surprisingly, the direct RCM products were isolated as a mixture of 1:1 E/Z isomers (66 and 67) in a very high yield (80%). The assignment of direct RCM products was supported by high-resolution mass spectroscopy and 2D NMR experiments. Changing the order of addition (adding 45 to a solution of 64 in benzene) gave the same product ratio. Furthermore, employing the second generation Grubbs catalyst 65 and running the reaction in refluxing toluene improved the product ratio of 66/67 to 1:2.3 favoring the E-isomer (entry 2).[36]

|

(8) |

Consequently, treatment of macrocycles 66/67 with PPTS in anhydrous MeOH cleanly removed both TES groups (Scheme 12). At this stage, diol 68/69 was separated by preparative TLC, and their structures were determined by IR, HRMS, 1H, 13C and 2D NMR experiments. Note that in the presence of water the global deprotection only resulted in a complex mixture; however, treatment of this mixture with PPTS in dry MeOH provided the same mixture (68 and 69) as above. We rationalize that this interesting phenomena was likely caused by the rapid tautomerization of the undeprotected C9 hemiketal (Figure 7).

Scheme 12.

Final deprotection of 66 and 67.

Figure 7.

Biological evaluation of novel ring-expanded bryostatin analogues

Compounds 68 and 69 contain all the functionalities present in the bryostatins except that they have an unusual 31-membered macrolactone. As almost all the previous efforts on the synthesis of bryostatin analogues have been centered on the 26-membered macrocycle backbone, we envisioned that these “ring-expanded bryostatins” could serve as a family of new analogues to further probe the structure-activity-relationships (SAR) of the bryostatins. Toward this end, macrocycles 68 and 69 and acyclic compound 52 were tested against several cancer cell lines (Table 3). Interestingly, while acyclic compound 52 is completely inactive, 31-membered lactones 68 and 69 exhibit activities against a range of cancer cell lines, including SKBR3–a breast cancer cell line, SKOV3–an ovarian cancer cell line, and NCI-ADR–a breast cancer cell line with added multi-drug resistant pumps. Remarkably, analogue 69 was effective at nm levels against all three cell lines, most notably with respect to NCI-ADR where the IC50 value was as low as 123 nm.[37]

Table 3.

Biological activities of bryostatin analogues..

| Sample | SKBR3 | SKOV3 | NCI-ADR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 68 | 560 nM | 840 nM | 1100 nM |

| 69 | 52 nM | 66 nM | 123 nM |

The numbers are the half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 68 and 69 in cell growth inhibition assays. SKBR3: a breast cancer cell line. SKOV3: an ovarian cancer cell line. NCI-ADR: a breast cancer cell line with multi-drug resistant pumps.

II. Development of a New-Generation Strategy to Access the C7-C27 Fragment

We have disclosed the synthetic challenges to install the C16-C17 olefin at a late stage via either a macrocyclic RCM or a RRCM strategy. Indeed, previous syntheses noted the difficulties of forming this double bond[4], which led us to conceive of a new strategy to install this sterically hindered trans alkene at an earlier stage.

We envisioned that enyne fragment 70 could serve as a linchpin to allow us to “glue” all the subunits together (Figure 8). The function of fragment 70 is three-fold: 1) the homopropargyl alcohol moiety could permit the usage of a Ru-catalyzed tandem enyne coupling/Michael addition to construct the bryostatin B-ring; 2) it provides the C16-17 olefins directly; 3) the TBS protected primary alcohol could serve as a masked terminal alkyne, so that fragment 70 could also provide a linkage to build the bryostatin C-ring via Pd-catalyzed alkyne-alkyne coupling then 6-endo-dig cyclization.

Figure 8.

Linchpin: fragment 70.

As substrates with an allylic alcohol moiety have not been examined in the Ru-catalyzed enyne coupling/Michael addition reaction previously and it is known that allylic alcohols are able to participate in various Ru-catalyzed transformations, such as redox isomerization,[38] the issue of chemoselectivity needed to be investigated for use of enyne 70 as the substrate. On the other hand, the Pd-catalyzed alkyne-alkyne coupling and 6-endo-dig cyclization have not been previously tested on rather complex substrates. Therefore, it was necessary to build a model system to address these chemoselectivity issues. Consequently, compound 71, with the C7-C27 bryostatin skeleton as well as the B-ring and C-ring entities, was designed as the model target (Scheme 13).

Scheme 13.

Retrosynthetic analysis of compound 71.

Enantioselective synthesis of TMS-alkyne 70 is described in Scheme 14. Aldehyde 74[39] was treated with cis-2-ethoxyvinyl lithium 75 and Me2Zn followed by acidic aqueous workup, providing homologated α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 76 in 97% yield.[40] NaHSO4 was selected as a mild acid source; when 1N HCl was used, a much lower yield (51%) was observed. According to a protocol described by Loh et al,[41] treatment of aldehyde 76 with indium metal, TMS-propargyl bromide and a catalytic amount of InF3 in refluxing THF, afforded the racemic homopropargyl alcohol 70 in 68% yield. Dess-Martin oxidation[42] of the allylic alcohol followed by CBS-reduction[43] of the corresponding ketone 77 afforded 70 in 90% ee and 90% yield over two steps. The homopropargyl ketone 77 proved to be quite unstable and extremely sensitive to acids,[44] hence after aqueous workup, it was directly subjected to the subsequent reduction without any purification.

Scheme 14.

Asymmetric synthesis of fragment 70.

A Weinreb-amide route to ketone 77 has also been explored, since it could potentially shorten the synthesis by one step (Scheme 15). The Weinreb-amide 78 was synthesized in 56% yield via Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons (HWE) olefination[45] of aldehyde 74. Although subsequent allenyllithium addition was able to provide the desired ketone 77, the impurity in the crude (compound 77 cannot be purified by chromatography) did not permit the following CBS reduction, especially on large scale. Therefore, this route was abandoned.

Scheme 15.

A Weinreb-amide route.

The other fragment, β,γ-unsaturated ketone 73, was prepared according to our earlier procedure.[9] With both alkene 73 and alkyne 70 in hand, the conditions for the Ru-catalyzed tandem alkene-alkyne coupling-Michael addition were next examined (Scheme 16). [CpRu(CH3CN)3]PF6 complex (10 mol%) was employed as the catalyst, and three equiv of alkene 73 were used to ensure good conversion. As the initial cyclization product was difficult to separate from the starting materials, the TBS group was subsequently removed with HF in pyridine to give primary alcohol 79, which could be easily purified. We found that the solvent plays an important role on the product conversion. Under the original reaction conditions, in which acetone was used, the tetrahydropyran 79 was only isolated in 32% yield;[46] however, upon switching to DCM, a much higher conversion and a much cleaner reaction were observed with an isolated yield of 62% yield over two steps, almost doubling that of the reaction in acetone. We rationalize that as DCM is a much less coordinating solvent than acetone, thus enhancing the reactivity of [CpRu(CH3CN)3]PF6. The diastereoselectivity ratio (dr) for this cyclization was around 6.7:1 (determined by 1H NMR integration of peaks δmajor 2.91 ppm and δminor 2.80 ppm), favoring the cis-isomer.

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of 79.

Advancement of 79 to terminal alkyne 72 was achieved in two steps. Dess-Martin oxidation of the primary alcohol, followed by Ohira–Bestmann alkynylation[47] of the corresponding aldehyde, provided alkyne 72 in 79% yield over two steps (Scheme 17).

Scheme 17.

Synthesis of alkyne 72.

The stage was now set to test the Pd-catalyzed alkyne-alkyne coupling. The acceptor alkyne 9 was synthesized in 6 steps from commercially available D-galactonic acid-1,4-lactone (see Part I). The coupling between alkynes 72 and 9 proceeded well when using 10 mol% Pd(OAc)2/tris(2,6-dimethoxyphenyl)phosphine (TDMPP) as the catalyst (eq 9); enyne 82 was isolated in 73% yield. The primary alcohol, the vinylsilane and the trans olefin remained intact under the reaction conditions, which demonstrates excellent chemoselectivity of the Pd-catalyzed alkyne-alkyne coupling.

|

(9) |

A metal-catalyzed 6-endo-dig cyclization of enyne 82 was next required to construct the C-ring of bryostatin (eq 10). As shown in our previous paper (Part I), this cyclization could be very challenging because a number of possible by-products can be formed. For example, if the alkyne were substituted with a bulky group, such as a t-Bu group, formation of the 5-exo addition product would be competitive. In addition, acids can catalyze the isomerization of the external olefin of the 6-endo-dig product, giving the other geometric isomer (Scheme 18).[48] Moreover, the secondary alcohol could attack the ester, instead of the alkyne, to give the 6-membered lactone. Given these concerns, we decided to revisit this 6-endo-dig cyclization issue.

Scheme 18.

Bronsted acids-catalyzed olefin isomerization.

|

(10) |

With the goal of achieving good regio- and chemoselectivity, the conditions for this 6-endo-dig cyclization were optimized and a number of catalysts were surveyed (Table 4). When enyne 82 was subjected to the previously optimized conditions ([PdCl2(CH3CN)2 (17 mol%), TDMPP (10 mol %), THF, rt), the products from 6-endo (71+83) and 5-exo (84) pathways were isolated with a ratio around 1:1 (entry 1). A slightly better 6-endo/5-exo ratio (around 2:1) was observed when using Pd(OAc)2-TDMPP-Pd(TFA)2 as the catalyst and using benzene as the solvent; however, this reaction gave incomplete conversion and around 30 % lactone 85 was formed (entry 2). Eventually, the most satisfactory result was found when using cationic gold(I) complex [Au(PPh3)]+SbF6− as the catalyst in CH3CN (entry 3).[49] The product ratio among 71 : 83 : 84 was enhanced to 5.1 : 1 : 1.3, which is equal to ca 5 : 1 6-endo/5-exo regioselectivity. NaHCO3 was purposely employed as a buffer to minimize the acid-catalyzed olefin isomerization. The only drawback to these conditions was that the reaction proceeded relatively slow (53% yield over 4 days). When the Au-catalyzed reaction was conducted in DCM, a much higher rate was observed; however the reaction became messy and many unidentified byproducts were formed. The structure of the final model study product 71 was confirmed by 1HNMR, IR, HRMS and 2D NMR experiments.

Table 4.

6-Endo-dig cyclization of enyne 82.

| Entry | Conditions | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | PdCl2(CH3CN)2 (17 mol%), TDMPP (10 mol%), THF, rt | 6-endo(71+83):5-exo (84) ca 1:1 |

| 2 | Pd(OAc)2 (20 mol%), TDMPP (20 mol%), then Pd(TFA)2 (30 mol%), benzene, rt | 71:83:84 = 1.5:0.5:1 (ca 10% 82 + ca 30% 85) |

| 3 | [Au(PPh3)]+SbF6− (20 mol%) CH3CN, NaHCO3, rt | 53% yield (71:83:84 = 5.1:1:1.3) |

The exact reason why the cationic gold catalyst gave much higher regio- and chemoselectivity is unclear. We rationalize that the higher chemoselectivity could be attributed to gold’s unique affinity for alkynes;[50] and the higher regioselectivity may relate to the ionic nature and linear structure of the AuI catalyst. As shown in Scheme 19, when Au binds to the alkyne, the steric interaction between the substituted t-Bu-like group and [Au(PPh3)] cation plus the adjacent SbF6 anion would largely disfavor the 5-exo addition, because this interaction would become much worse in intermediate 90 than in 91. Hence, the 6-endo pathway is preferred.

Scheme 19.

5-exo vs 6-endo addition.

Conclusion

By taking advantages of the two tandem methods, Ru-catalyzed enyne coupling/Michael addition and Pd-catalyzed diyne coupling/6-endo cyclization, we were able to furnish fully functionalized both northern and southern fragments of bryostatin. An esterification/olefin metathesis strategy has been investigated to unit the two fragments and to advance them to the natural product. Although formation of the C16-17 olefin via olefin metathesis was unfruitful, we were able to synthesize two new bryostatin analogues with a ring-expanded backbone. Theses analogues retain almost all the functionalities in the bryostatins, and their biological activities against several cancer cell lines, including NCI-ADR (the one with multi-drug resistant pumps).

To overcome this “olefination problem”, a new strategy was developed to install the C16-17 olefin at an earlier stage. Enyne 70 was designed and synthesized to serve as a “linchpin” to connect both northern and southern parts together. By elaborating this strategy, model substrate 71, containing the C7-27 carbon skeleton and the B,C-rings of bryostatin, was synthesized in only 6 steps. During these studies, several chemoselectivity issues were addressed, including the functional group tolerance in the Ru-catalyzed tandem alkene-alkyne coupling/Michael addition, and the Pd-catalyzed alkyne-alkyne coupling. Moreover, a cationic gold complex was found to be a superior new catalyst for the challenging 6-endo-dig cyclization. Therefore, our ring-expanded analogue synthesis along with this new linchpin strategy described in this article should provide key supports for our subsequent accomplishment of the total synthesis of bryostatins.

Experimental Section

All reactions were run under an atmosphere of nitrogen unless otherwise indicated. Anhydrous solvents were transferred via oven-dried syringe or cannula. Flasks were flame-dried under vacuum and cooled under a stream of nitrogen or argon. Tetrahydrofuran (THF), dimethoxyethane (DME), Benzene, pyridine, diisopropylamine, triethylamine, diisopropylethylamine, dimethylsulfoxide, acetonitrile, hexane, toluene, diethyl ether, and dichloromethane were purified with a Solv-Tek solvent purification system by passing through a column of activated alumina. Acetone was distilled from calcium sulfate. Methanol was distilled from magnesium methoxide.

Where indicted, solvents are degassed via freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing under high vacuum. The above cycle is repeated three times, unless otherwise indicated. Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out using 0.2 mm commercial silica gel plates (DC-Fertigplatten Krieselgel 60 F254). Melting points were determined on a Thomas-Hoover melting point apparatus in open capillaries and are uncorrected. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer 1420 spectrophotometer. Absorbance frequencies are reported in reciprocal centimetres (cm−1).

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were recorded using a Varian UI-600 (600 MHz), UI-500 (500 MHz) or Varian MERC-400 (400 MHz). Chemical shifts are reported in delta (δ) units, part per million (ppm) downfield from tetramethylsilane (TMS) or in ppm relative to the singlet at 7.26 ppm for deuterochloroform. Coupling constants are reported in Hertz (Hz). The following abbreviations are used: s, singlet, d, doublet, t, triplet, q, quartet, m, multiplet.

Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) spectra were recorded using a Varian UI-600 (150 MHz), Varian UI-500 (125 MHz) or Varian MERC-400 (100 MHz). Chemical shifts are reported in delta (δ) units, part per million (ppm) relative to the center line of the triplet at 77.1 ppm for deuterochloroform. 13C NMR spectra were routinely run with broadband decoupling. Optical rotation data was obtained with a Jasco DIP-360 digital polarimeter at the sodium D line (589 nm) in the solvent and concentration indicated.

Compound 30: To a mixture of alkene 14c (2.09 g, 3.33 mmol) and alkyne 7 (0.442 g, 1.51 mmol) in a V-shaped vial with a septum was added acetone (freshly distilled over calcium sulfate, 3 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 min to ensure formation of a homogeneous solution, and the septum was quickly removed to allow the addition of [CpRu(CNCH3)3]PF6 (65 mg, 0.15 mmol) all at once. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 40 h and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with EtOAc/petroleum ether (10%, 12.5%, 15%, 17.5%, and 20%) to give 0.81 g of 30 as a pale yellow foam (56% yield, 9:1 dr determined by integrating peaks at 5.38 and 5.36 ppm). Significant amount of both alkene 14c and alkyne 7 were recovered as an inseparable mixture (1.02 g, 14c/7 7:1). [α]D23 −35.5 (c 0.6, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.66-7.61 (m, 4H), 7.23-7.17 (m, 10H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.74 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.38 (s, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H), 4.38-4.35 (m, 3H), 4.22-4.16 (m, 1H), 4.03 (dd, J = 1.7, 10.3 Hz, 1H), 3.81-3.75 (m, 1H), 3.69-3.63 (m, 2H), 3.53 (dd, J = 5.2, 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.41 (dd, J = 5.3, 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.29 (s, 3H), 3.27 (s, 3H), 3.07 (dd, J = 7.0, 17.3 Hz, 1H), 2.66 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (dd, J = 5.2, 17.3 Hz, 1H), 2.34 (dd, J = 5.2, 16.5 Hz, 1H), 2.29 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 2.21 (dd, J = 5.6, 16.4 Hz, 1H), 2.09 (q, J = 12.3 Hz, 2H), 1.56-1.30 (m, 4H), 1.13 (s, 3H), 1.08 (s, 9H), 1.04 (s, 3H), 0.17 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 210.9, 168.9, 159.7, 153.7, 136.0, 135.9, 133.9, 133.7, 131.4, 131.0, 130.3, 130.2, 129.6, 129.3, 128.3, 128.1, 127.9, 123,6, 114.0, 80.1, 77.7, 75.3, 73.3, 73.0, 72.7, 65.7, 54.8, 54.7, 52.8, 45.6, 45.3, 39.6, 38.9, 38.3, 37.4, 26.9, 21.5, 20.4, 19.2, 0.4; IR (neat film) 3075, 3042, 1742, 1705, 1609, 1585, 1510, 1484, 1427, 1386, 1361, 1303, 1245, 1170, 1108, 1091, 1033, 839, 818, 739, 702 cm−1, TLC Rf 0.37 (20% EtOAc/petroleum ether); EA Calcd for C54H72O9Si2: C, 70.40; H, 7.88. Found: C, 70.21; H, 7.80.

Compound 32: A solution of diol 31 (0.62 g, 0.9 mmol) and pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (99 mg, 0.39 mmol) in CH3OH (15 mL) and trimethyl orthoformate (0.75 mL) was heated under reflux for 2 h. The content was cooled to room temperature, poured into saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with EtOAc/petroleum ether (30%, 40%, and 50%) to give 0.47g of 32 as an oil (71% yield). [α]D23 −30.5 (c 1.4, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.82-7.77 (m, 4H), 7.24-7.20 (m, 6H), 5.83 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.54-4.49 (m, 1H), 3.73-3.69 (m, 1H), 3.43-3.31 (m, 3H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 3.14-3.10 (m, 1H), 2.83 (s, 3H), 2.71-2.62 (m, 3H), 2.01-1.94 (m, 3H), 1.83-1.75 (m, 1H), 1.67-1.49 (m, 4H), 1.18-1.15 (m, 2H), 1.16 (s, 9H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 0.9 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 171.6, 140.3, 136.3, 134.4, 134.2, 130.1, 128.3, 104.0, 100.8, 77.3, 74.4, 70.4, 69.4, 66.2, 65.8, 51.2, 48.0, 44.4, 43.4, 43.2, 42.0, 38.8, 36.5, 32.7, 27.1, 20.9, 19.5, 15.8; IR (neat film) 3446, 3073, 3047, 1734, 1632, 1588, 1472, 1428, 1388, 1357, 1260, 1105, 953, 821, 736, 701 cm−1; TLC Rf 0.50 (50% EtOAc/petroleum ether); HRMS calcd for C37H53BrNaO8Si [M+Na]+: 755.2591. Found: 755.2592.

Compound 39: To a solution of aldehyde 38 (0.33 g, 0.75 mmol) in THF (1.3 mL) in a pressure tube at room temperature was added dimethyltitanocene (Petasis reagent)75 in THF (0.52 M, 5.3 mL, 2.76 mmol). The tube was sealed and the reaction was heated at 90 °C for 2.5 h. The content was cooled to room temperature and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel with Et2O/petroleum ether (20%, 30%, and 40%) to give 0.193 g of olefin 39 (58% yield). [α]D24 +3.3 (c 0.5, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.43 (dd, J = 10.8, 17.7 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (t, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (s, 1H), 4.87 (dd, J = 1.5, 17.7 Hz, 1H), 4.82 (dd, J = 1.5, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (ddt, J = 2.8, 5.5, 12.7 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (ddd, J = 1.2, 8.4, 10.5 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (dd, J = 1.8, 15.8 Hz, 1H), 3.48 (dq, J = 6.0, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.32 (s, 3H), 3.31 (s, 3H), 2.47 (ddd, J = 2.2, 11.8, 14.8 Hz, 1H), 1.61 (s, 3H), 1.48 (ddd, J = 2.1, 10.0, 12.2 Hz, 1H), 1.36 (s, 3H), 1.35 (s, 3H), 1.37-1.31 (m, 1H), 1.23 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.08 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 168.5, 166.4, 153.2, 146.6, 117.5, 108.8, 107.9, 103.0, 78.5, 77.2, 72.2, 68.8, 51.2, 50.7, 47.0, 38.6, 33.3, 27.5, 27.4, 24.3, 23.0, 20.8, 17.0; IR (neat film) 3076, 2996, 2931, 1746, 1719, 1664, 1460, 1433, 1370, 1230, 1157, 1094, 1048, 1021, 994 cm−1; TLC Rf 0.59 (20% EtOAc/petroleum ether); HRMS calcd for C22H32O7 [M−CH4O]+: 408.2148. Found: 408.2129.

Compound 40: A mixture of 39 (40 mg, 0.09 mmol) in 75% (v/v) aqueous acetic acid (7 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 6 h. The content was poured into ice-cooled saturated aqueous Na/K tartrate, neutralized with saturated aqueous Na2CO3, and extracted with EtOAc three times. The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with Et2O/petroleum ether (50%) followed by CH3OH/CH2Cl2 (6%) to give 34 mg of a triol contaminated by small amount (<10%) of impurity. [α]D24 −11.1 (c 0.55, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.43 (dd, J = 10.5, 14.0 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 5.54 (s, 1H), 4.94-4.89 (m, 2H), 4.33 (t, J = 10.6 Hz,1H), 4.07 (dd, J = 2.1, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 3.77-3.73 (m, 1H), 3.44 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 3.32 (s, 3H), 2.33 (t, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 1.80-1.74 (m, 1H), 1.67-1.61 (m, 1H), 1.61 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.23 (s, 3H), 1.05 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 168.8, 166.8, 152.2, 145.4, 120.3, 110.8, 100.1, 73.8, 72.8, 71.3, 67.1, 50.9, 45.7, 39.6, 23.0, 21.8, 21.0, 20.2, 19.5; IR (neat film) 3438 (br), 3076, 1743, 1721, 1683, 1635, 1437, 1410, 1369, 1234, 1152, 1080, 1031, 1017, 745, 728 cm−1; TLC Rf 0.18 (6% CH3OH/CH2Cl2); HRMS calcd for C14H21O8 [M−C5H9]+: 317.1236. Found: 317.1240.

To a solution of the above triol (34 mg, 0.088 mmol) in DMF (2.5 mL) at −30 °C was added Et3N (0.12 mL, 0.86 mmol), followed by TESCl (16.3 μL, 0.097 mmol). The reaction was stirred at −30 °C for 30 min and the content was poured into saturated aqueous NaHCO3. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with EtOAc/petroleum ether (20% and 30%) to give 23 mg of 40 (52% yield over two steps). [α]D22 −7.5 (c 0.75, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.41-6.36 (m, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 5.55 (s, 1H), 4.88 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 1H), 4.87 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (t, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (dd, J = 2.3, 13.9 Hz, 1H), 3.82-3.79 (br m, 1H), 3.57 (s, 1H), 3.51 (pent, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (s, 3H), 2.65 (br d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (ddd, J = 2.0, 11.6, 13.6 Hz, 1H), 1.72-1.67 (m, 1H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 1.60-1.54 (m, 1H), 1.27(s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.05 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 9H), 0.53 (q, J = 7.9 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 168.6, 166.5, 152.0, 145.2, 120.4, 111.4, 99.6, 74.0, 72.0, 67.3, 50.7, 45.7, 39.8, 32.0, 22.4, 22.1, 21.0, 20.0, 7.1, 5.2; IR (neat film) 3408 (br), 3082, 1741, 1718, 1662, 1434, 1369, 1230, 1174, 1155, 1086, 1030 cm−1; TLC Rf 0.52 (40% EtOAc/petroleum ether); HRMS calcd for C25H42O7 [M−H2O]+: 482.2700. Found: 482.2698.

Compound 48: A mixture of 47 (40 mg, 0.075 mmol) and trimethyltin hydroxide (135 mg, 0.75 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3.2 mL) in a sealed vial was heated with a microwave at 140 °C for 40 min. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and directly purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with EtOAc/petroleum ether (40%) followed by CH3OH/CH2Cl2 (6% and 12%) to give 32 mg of 48 (82% yield). [α]D23 +75.0 (c 0.3, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.02 (s, 1H), 5.82 (ddd, J = 5.0, 11.0, 17.5 Hz, 1H), 5.51 (dd, J = 4.5, 11.3 Hz, 1H), 5.26 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 3.86-3.82 (m, 1H), 3.74-.3.69 (m, 1H), 3.58-3.53 (m, 1H), 3.05 (s, 1H), 3.04 (s, 3H), 2.94 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H), 2.35-2.13 (m, 4H), 1.77-1.64 (m, 4H), 1.70 (s, 3H), 1.43 (q, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 1.36-1.30 (m, 1H), 1.30-1.23 (m, 1H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.04 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 170.1, 140.6, 138.7, 114.8, 104.1, 100.6, 77.4, 74.5, 73.9, 65.3, 64.9, 48.3, 42.4, 42.3, 42.1, 41.8, 38.9, 36.9, 32.8, 20.8, 20.7, 17.0; IR (thin film) 3499 (br), 3077, 1735, 1434, 1365, 1245, 1159, 1129, 1060, 1021 cm−1; TLC Rf 0.42 (8% CH3OH/CH2Cl2).

Compound 60: To a suspension of anhydrous CrCl2 (99.99% from Aldrich, 2.0 g, 16.26 mmol) in freshly distilled THF (10 mL) at 0 °C was added a solution of 38 (470 mg, 1.06 mmol) and CHI3 (2.53 g, 6.38 mmol) in THF (6 mL + 2 × 2 mL rinse) via cannula. The ice bath was removed and the brown suspension was stirred at room temperature in dark for 20 h before being poured into 1:1 brine/H2O. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic extracts were concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with EtOAc/petroleum ether (5%, 10%, and 20%) to give 158 mg of the vinyl iodide 60 (26% yield) and 208 mg of recovered aldehyde 38 (47% yield based on recovered starting material). [α]D23 −9.7 (c 0.9, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.08 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 1H), 6.10 (s, 1H), 5.82 (s, 1H), 5.72 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 1H), 4.07 (dddd, J = 2.5, 2.5, 5.0, 12.5 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (ddd, J = 2.0, 8.5, 10.5 Hz, 1H), 3.49-3.43 (m, 2H), 3.36 (s, 3H), 3.26 (s, 3H), 2.49 (dd, J = 12.0, 15.5 Hz, 1H), 1.75 (s, 3H), 1.354 (s, 3H), 1.352 (s, 3H), 1.34-1.28 (m, 3H), 1.24-1.18 (m, 2H), 1.07 (d, J = 6 Hz, 3H), 1.04 (s, 3H), 0.99 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 168.8, 166.3, 153.8, 153.2, 116.4, 107.9, 102.2, 78.3, 77.2, 73.0, 71.0, 68.7, 50.7, 50.6, 50.4, 38.3, 34.3, 27.5, 23.1, 22.6, 20.9, 17.0; IR (neat film) 3072, 1745, 1719, 1662, 1596, 1433, 1380, 1367, 1227, 1165, 1095, 1042 cm−1; TLC Rf 0.35 (16% EtOAc/petroleum ether); HRMS Calcd for C23H35IO8 [M−CH3]+: 551.1142. Found: 551.1165.

Compound 62: To a cooled Et2O (6 mL) at −78 °C was added tBuLi (1.7 in pentane, 3.44 mL, 5.84 mmol), followed by dropwise-addition of 5-boromo-1-pentene (0.3 mL, 2.95 mmol). The resultant yellow-green solution was stirred at −78 °C for 40 min and a solution of zinc chloride (0.41 g, 3.0 mmol, freshly flamed under a slow stream of nitrogen) in THF (6 mL) was added via cannula. The yellow-green colour disappeared upon the addition of zinc chloride. The cold bath was removed and the content was warmed to room temperature during which it turned cloudy white. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 45 min and then the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in THF (10 mL) to give 4-pentenyl zinc chloride 61 (0.3 M in THF).

To a mixture of vinyl iodide 60 (157 mg, 0.277 mmol) and Pd(PPh3)4 (32 mg, 0.03 mmol) at room temperature was added the above zinc reagent 61 (5 mL + 2 mL THF rinse). The content was stirred at room temperature for 7 h, poured into pH 7 phosphate buffer, and extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic extracts were concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with EtOAc/petroleum ether (8% and 10%) to give 62 mg of triene 62 and 27 mg of 62 and 39 as a 5:1 mixture (68% combined yield).

[α]D22 −12.7 (c 0.65, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.20 (s, 1H), 5.97 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 5.81 (s, 1H), 5.76 (dddd, J = 7.0, 7.0, 10.5, 17.0 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (ddd, J = 6.5 6.5, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (dq, J = 2.0, 17.5 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (dddd, J = 2.5, 2.5, 5.5, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (ddd, J = 2.0, 8.5, 10.5 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 3.52-3.46 (m, 1H), 3.35 (s, 3H), 3.34 (s, 3H), 2.55-2.49 (m, 1H), 2.01-1.95 (m, 4H), 1.64 (s, 3H), 1.51-1.30 (m, 4H), 1.372 (s, 3H), 1.369 (s, 3H), 1.31 (s, 3H), 1.29 (s, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 6 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 168.6, 166.4, 153.7, 138.9, 138.0, 125.8, 116.8, 114.8, 107.9, 103.0, 78.5, 77.2, 72.2, 68.6, 51.0, 50.7, 46.4, 38.6, 34.0, 33.8, 32.8, 29.0, 27.52, 27.46, 24.8, 24.2, 20.6, 17.1; IR (neat film) 3077, 1745, 1719, 1663, 1638, 1496, 1377, 1364, 1228, 1155, 1091, 1049, 1023 cm−1; TLC Rf 0.47 (15% EtOAc/petroleum ether); HRMS Calcd for C27H41O7 [M−CH3O]+: 477.2852. Found: 477.2818.

Compound 64: To a mixture of DMAP (1.2 mg, 0.01 mmol) and MNBA (2-methyl-6-nitrobenzoic anhydride, 34.4 mg, 0.1 mmol) at room temperature was added CH2Cl2 (3.4 mL) and Et3N (0.042 mL, 0.3 mmol). The content was stirred at room temperature for 5 min, after which a homogeneous light yellow solution was formed. The above prepared solution (1.5 mL) was added to acid 50 (23.7 mg, 0.039 mmol) in a V-shaped vial (rinsed with 0.3 mL of CH2Cl2). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min, and a solution of alcohol 63 (26.7 mg, 0.047 mmol) was added to the vial via cannula. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 16 h and the content was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with EtOAc/petroleum ether (5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 30%) to give 23 mg of 64 (51% yield). [α]D23 +12.7 (c 0.3, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (600 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.33 (s, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 6.01 (s, 1H), 5.90-5.80 (m, 2H), 5.55 (td, J = 4.8, 11.4 Hz, 2H), 5.51 (s, 1H), 5.44 (dt, J = 6.6, 16.2 Hz, 1H), 5.38 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 5.08 (dd, J = 1.2, 15.6 Hz, 1H), 5.02 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 2H), 4.40 (quin, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 1H), 4.07 (t, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (pent, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (dd, J = 2.4, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 3.80-3.74 (m, 2H), 3.46 (s, 3H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 3.15 (s, 3H), 2.99 (s, 1H), 2.81 (dd, J = 4.2, 16.2 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (dd, J = 7.2, 16.2 Hz, 1H), 2.40-2.36 (m, 2H), 2.23 (dd, J = 6.0, 15.6 Hz, 1H), 2.15-2.12 (m, 2H), 2.09-2.04 (m, 2H), 1.99 (t, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 1.91-1.76 (m, 4H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.63-1.59 (m, 1H), 1.60 (s, 3H), 1.57-1.48 (m, 2H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.37 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H), 1.21 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 1.20 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.07-1.01 (m, 18H), 0.69-0.63 (m, 12H); 13CNMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 172.0, 169.9, 168.6, 166.6, 166.5, 157.7, 152.2, 138.9, 138.8, 136.9, 120.5, 115.1, 114.8, 114.6, 104.5, 99.5, 77.9, 74.9, 74.3, 73.7, 73.6, 68.7, 67.9, 66.3, 66.2, 50.8, 50.6, 48.3, 45.2, 44.2, 44.0, 43.3, 42.4, 39.4, 35.9, 35.0, 33.8, 32.8, 31.7, 30.4, 30.2, 29.3, 23.7, 22.3, 20.93, 20.90, 20.7, 18.6, 16.9, 7.21, 7.19, 5.5, 5.2; IR (thin film) 3508, 3077, 1744, 1718, 1655, 1462, 1435, 1368, 1233, 1152, 1112, 1080, 1027, 910, 874, 744, 726 cm−1; TLC Rf 0.63 (20% EtOAc/petroleum ether); HRMS calcd for C61H106O17Si2N [M+NH4]+: 1180.6999. Found: 1180.6974.

Compound 66 and 67: To a solution of 64 (20 mg, 0.018 mmol) in benzene (8 mL) at 50 °C with N2 sparging was added Hoveyda catalyst 65 (4.5 mg, 18 mol%) in benzene (2 mL) via a syringe over 5 min. The content was stirred at 50 °C for 30 mins before raising the bath temperature to 80 °C. Stirring was continued for 15 min at 80 °C. The content was cooled to room temperature. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by preparative TLC with EtOAc/petroleum ether (16%) to give 16 mg of 66 and 67 (80% combined yield) as 1:1 mixture by integrating peaks at 3.36 and 3.32 ppm in 1H NMR. HPLC retention time: 5.72 min and 7.07 min (Alltech-Econosphere silica 3 micro column; 99:1 heptane:isopropanol; 254 nm; 1 mL/min); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.34-6.33 (m), 6.09 (s), 6.02-5.97 (m), 5.90-5.84 (m), 5.79-5.75 (m), 5.67-5.62 (m), 5.59-5.53 (m), 5.52 (s), 5.46 (s), 5.45-5.34 (m), 4.67-4.61 (m), 4.52 (t, J = 9.0 Hz), 4.41-4.29 (m), 4.20-4.14 (m), 4.08 (d, J = 12.0 Hz), 4.04-3.87 (m), 3.82-3.76 (m), 3.45 (s), 3.43 (s), 3.36 (s), 3.32 (s), 3.19 (s), 3.13 (s), 3.12 (s), 3.02 (s), 2.85 (d, J = 4.5 Hz), 2.82 (d, J = 4.0 Hz), 2.57-2.46 (m), 2.39-2.32 (m), 2.25-1.67 (m), 1.50 (d, J = 6.5 Hz), 1.46 (d, J = 10.0 Hz), 1.37 (s), 1.18 (d, J = 7.5 Hz), 1.14 (d, J = 6.5 Hz), 1.08-0.95 (m), 0.69-0.52 (m); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 172.0, 170.8, 170.2, 169.9, 168.7, 168.2, 166.7, 166.49, 166.47, 166.40, 158.2, 157.5, 152.0, 151.9, 136.6, 135.8, 132.32, 132.25, 131.8, 131.0, 125.8, 121.1, 120.3, 115.4, 114.6, 104.5, 103.9, 100.3, 99.0, 78.4, 74.8, 74.7, 74.42, 74.39, 74.25, 73.5, 73.4, 69.2, 68.4, 67.8, 66.5, 66.4, 66.2, 66.0, 64.5, 50.79, 50.74, 50.6, 50.4, 48.9, 47.8, 45.5, 45.3, 44.2, 44.0, 43.6, 43.2, 43.0, 42.95, 42.2, 40.4, 39.7, 36.5, 36.2, 35.8, 35.0, 34.3, 33.9, 33.3, 32.0, 31.6, 31.2, 30.9, 30.4, 30.3, 30.2, 28.1, 27.2, 26.1, 25.4, 25.0, 21.6, 21.3, 20.8, 19.4, 18.5, 17.7, 15.6, 7.25, 7.19, 7.10, 6.0, 5.8, 5.2; IR (thin film) 3510, 1721, 1650, 1431, 1370, 1232, 1156, 1113, 1080, 1023, 728, 724 cm−1; HRMS calcd for C59H98O17Si2Na [M+Na]+: 1157.6240. Found: 1157.6104.

Compound 68 and 69: A solution of 66 and 67 (7 mg, 0.006 mmol) and PPTS (8 mg, 0.032 mmol) in CH3OH was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. The content was poured into saturated NaHCO3 and extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by preparative TLC (60% EtOAc/PE) to give 2.6 mg of 68 and 2 mg of 69 (82% combined yield). Characterization for 68: [α]D24 +72.2 (c 0.53, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (600 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.34 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 5.92 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (s, 1H), 5.75 (dd, J = 7.2, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (s, 1H), 5.46-5.42 (m, 2H),5.39-5.34 (m, 1H), 5.32 (ddd, J = 3.0, 6.0, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 4.49 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.37-4.33 (m, 2H), 4.20 (tt, J = 2.4, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (dd, J = 1.8, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (br, 1H), 3.66-3.62 (m, 1H), 3.60-3.56 (m, 1H), 3.51 (pent, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (s, 3H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 3.17 (br, 1H), 2.82 (s, 3H), 2.30-2.14 (m, 7H), 2.12-2.07 (m, 1H), 2.03 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 1.99 (dd, J = 3.0, 13.2 Hz, 1H), 1.86 (t, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 1.76 (s, 3H), 1.72-1.56 (m, 5H), 1.62 (s, 3H), 1.53-1.51 (m, 1H), 1.44-1.40 (m, 1H), 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.37 (s, 3H), 1.15-1.11 (m, 1H), 1.11 (s, 3H), 1.07-1.03 (m, 1H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.92 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 170.8, 169.9, 168.5, 166.7, 156.9, 152.2, 136.7, 132.0, 131.3, 129.4, 120.3, 115.4, 104.7, 99.4, 75.3, 74.97, 74.93, 69.93, 66.6, 66.4, 65.8, 50.64, 50.62, 47.9, 45.3, 44.6, 44.2, 42.5, 40.6, 39.0, 36.8, 36.3, 31.7, 31.2, 30.9, 28.5, 26.7, 25.2, 21.5, 10.9, 20.8, 20.6, 19.5, 16.3; TLC Rf 0.44 (75% EtOAc in petroleum ether); IR (film) 3482, 1718, 1652, 1434, 1365, 1234, 1155, 1025, 983, 872 cm−1; HRMS calcd for C47H70O17Na [M+Na]+: 929.4513. Found: 929.4535. Characterization for 69: [α]D23 +36.6 (c 0.24, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (600 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.49 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 5.97 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 5.84-5.80 (m, 2H), 5.73 (s, 1H), 5.55 (s, 1H), 5.56-5.48 (m, 2H), 5.23 (ddd, J = 1.8, 6.6, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 4.30-4.24 (m, 3H), 4.13 (dd, J = 2.4, 13.8 hz, 1H), 3.94 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.83-3.71 (m, 3H), 3.52 (pent, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (br s, 1H), 3.39 (s, 3H), 3.26 (s, 3H), 3.09 (s, 3H), 2.35-2.30 (m, 1H), 2.20 (dd, J = 7.8, 16.8 Hz, 1H), 2.14-2.10 (m, 2H), 2.09-1.98 (m, 4H), 1.92 (dd, J = 3.0, 13.2 Hz, 1H), 1.86 (d, J = 13.8 Hz, 1H), 1.74 (s, 3H), 1.71-1.67 (m, 1H), 1.62 (s, 3H), 1.61-1.53 (m, 5H), 1.48-1.43 (m, 1H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.27 (s, 3H), 1.23-1.19 (m, 1H), 1.14 (s, 3H), 1.08-1.04 (m, 1H), 1.05 (s, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H); TLC Rf 0.63 (75% EtOAc in petroleum ether); IR (film) 3454, 1718, 1648, 1434, 1369, 1234, 1155, 1030, 974 cm−1, HRMS calcd for C47H70O17Na [M+Na]+: 929.4513. Found: 929.4597.

Compound (R)-70: Dess–Martin periodinane (6.95 g, 16.4 mmol) was added to a mixture of rac-70 (5.49 g, 15.6 mmol) and NaHCO3 (4.2 g, 49.9 mmol) in DCM (66 ml) at 0 °C. The reaction was stirred at rt for 30 min, before being quenched with saturated Na2S2O3 and saturated NaHCO3. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (150 ml × 3), and the combined organic fraction was dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed, and the crude ketone was dissolved with DCM (112 ml). The above solution was cooled to −78 °C, and (S)-2-methyl-CBS-oxazaborolidine (0.78 ml, 1M in toluene) was added. The reaction was stirred at −78 °C for 20 min before catechol borane (2.8 g, 23.4 mmol) was added. The resulting solution was stirred at −78 °C for 4 h, and then it was warmed to 0 °C. The reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 1h, before being quenched with 1M NaH2PO4. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate and the combined organic fractions were dried over Na2SO4. Compound (R)-70 was purified via silica gel flash column chromatography (5% Et2O/petroleum ether, then 10% Et2O/petroleum ether) to give a colorless oil (4.9 g, 90% over two steps, 90% ee, determined by chiral HPLC, OD 205 nm, 0.8 ml/min, 99.5:0.5 heptane/iPrOH, tmajor = 7.9 min, tminor = 7.2 min). [α]D20: +4.86 (c 0.64, DCM). Rf: 0.35 (10% Et2O:/petroleum ether, 1:9 v/v); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 5.72 (dd, J = 1.0, 20 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (dd, J = 8.0, 20 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (m, 1H), 3.28 (s, 2H), 2.45 (dd, J = 2.5, 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.02 (br, 1H), 0.97 (s, 3H), 0.88 (s, 12H), 0.15 (s, 9H), 0.00 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 140.1, 128.0, 103.0, 87.5, 71.7, 71.1, 38.2, 29.4, 26.0, 24.0, 18.4, 0.2, −5.4; IR (film): 3336 (br), 2958, 2858, 2178, 1464, 1250, 1099, 843 cm−1; HRMS (C15H29O2Si2+tBu): Calcd. 297.1706 [M−tBu]+, Found 297.1684.

Compound 79: [CpRu(CH3CN)3]+PF6− (1.4 mg, 0.0032 mmol) was added to a solution of compound (R)-70 (11.2 mg, 0.032 mmol) and compound 73 (17.4 mg, 0.094 mmol) in DCM (0.5 ml) at 0 °C. The resulting yellow solution was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. The tetrahydropyran was isolated via silica gel flash column chromatography as a mixture contaminated with (R)-70. To the above mixture was added THF (0.4 ml), and the resulting solution was cooled to 0 °C before HF•py (5 drops) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred vigorously for 5h at rt, before being quenched with saturated aqueous NaHCO3. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (20 ml × 3), and the combined organic fractions were dried over Na2SO4. Compound 79 was purified via silica gel flash column chromatography (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 4/1, and then 3/2) as a colorless oil (8.3 mg, 62%, dr 6.7:1, δmajor: 2.91 ppm, δminor: 2.80 ppm): Rf: 0.35 (40% ethyl acetate in petroleum ether); [α]D: −1.5 (c 0.40, DCM); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 5.60 (dd, J = 1.0, 16 Hz, 1H), 5.48 (dd, J = 5.5, 16 Hz, 1H), 5.29 (s, 1H), 4.10 (dd, J = 11, 24 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (m, 1H), 3.76 (m, 1H), 3.33 (s, 2H), 2.91 (dd, J = 6.0, 17 Hz, 1H), 2.53 (dd, J = 7.0, 17 Hz, 1H), 2.41 (dt, J = 2.0, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.24 (d, J = 13 Hz, 1H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 2.02-1.93 (2H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 1.02 (s, 3H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.10 (s, 9H); 13C NMR(CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 210.9, 171.1, 152.4, 138.2, 129.9, 124.3, 79.0, 75.0, 71.7, 7 0.0, 47.8, 45.2, 44.1, 40.7, 38.5, 24.1, 23.8, 21.7, 21.67, 21.1, 0.5; IR (film) 3473, 2956, 1747, 1702, 1624, 1472, 1375, 1247, 1140, 1046, 974, 840 cm−1; HRMS (C23H40O5Si): Calcd. 447.2543 for [M+Na]+, Found 447.2545.

Compound 71: To a mixture of Au(PPh3)3Cl (10.2 mg, 0.020 mmol) and AgSbF6 (7.0 mg, 0.020 mmol) was added dry DCM (0.4 ml) at room temperature under N2. The resulting mixture was stirred in the dark for 15 min, and a purple precipitate was formed. The supernatant solution (0.030 ml, ca 0.0015 mmol, 20 mol%) was added to a mixture of compound 82 (4.5 mg, 0.0071 mmol) and NaHCO3 (2.0 mg, 0.021 mmol) in CH3CN (0.10 ml) at 0 °C under N2. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred vigorously in the dark at room temperature for 4 days. The suspension was poured into pH 7.0 buffer, and the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate four times and the combined organic fractions were dried over Na2SO4. The dihydropyran products were isolated via silica gel flash column chromatography (20%, 30%, 40% then 50% ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) as a light-yellow oil (2.4 mg, 53%, ratio of 71 : 83 : 84 = 5.1 : 1 : 1.3, based on the integration of 1H NMR peaks δ 5.34, 6.80, 6.05 ppm respectively): Rf: 0.60 (40% ethyl acetate in petroleum ether); [α]D: 16.1 (c 0.24, DCM); For NMR data, see the supporting information. IR (film) 34854 (br), 2953, 2931, 1708, 1610, 1379, 1226, 1153, 1094, 840 cm−1; HRMS (C35H56O8Si): Calcd. 655.3642 for [M+Na]+, Found 655.3636.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of 41 and 42.

Table 2.

Relay ring-closing metathesis studies of compound 64.

| Entry | Conditions | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 mol% Hoveyda catalyst 45, benzene, 50 −80 °C, N2 sparging | 80% yield (66:67 = 1:1) |

| 2 | ca 20 mol% the second generation Grubbs Catalyst 65, toluene, reflux, N2 sparging | Small scale reaction, clean by TLC and NMR (66: 67 = 1:2.3) |

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM13598) and NSF for their generous support of our programs. HY thanks Amgen and Bristol-Myers Squibb for fellowships. GD thanks Stanford Graduate Fellow. Mass spectra were provided by the Mass Spectrometry Regional Center of the University of California-San Francisco, supported by the NIH Division of Research Resources. Palladium and ruthenium salts were generously supplied by Johnson-Matthey.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/ or from the authors.

References

- 1.For a preliminary report of a portion of our work, see: Trost BM, Yang H, Thiel OR, Frontier AJ, Brindle CS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2206–2207. doi: 10.1021/ja067305j.

- 2.Bryostatin isolation and structure determination: Bryostatin 1: Pettit GR, Herald CL, Doubek DL, Herald DL, Arnold E, Clardy J. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6846–6848.Bryostatin 2: Pettit GR, Herald CL, Kamano Y, Gust D, Aoyagi R. J Nat Prod. 1983;46:528–531.Bryostatins 1–3: Pettit GR, Herald CL, Kamano Y. J Org Chem. 1983;48:5354–5356.Bryostatin 3: Schaufelberger DE, Chmurny GN, Beutler JA, Koleck MP, Alvarado AB, Schaufelberger BW, Muschik GM. J Org Chem. 1991;56:2895–2900.Chmurny GN, Koleck MP, Hilton BD. J Org Chem. 1992;57:5260–5264.Bryostatin 4: Pettit GR, Kamano Y, Herald CL, Tozawa M. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:6768–6771.Bryostatins 5–7: Pettit GR, Kamano Y, Herald CL, Tozawa M. Can J Chem. 1985;63:1204–1208.Bryostatin 8: Pettit GR, Kamano Y, Aoyagi R, Herald CL, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Rudloe JJ. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:985–994.Bryostatin 9: Pettit GR, Kamano Y, Herald CL. J Nat Prod. 1986;49:661–664. doi: 10.1021/np50046a017.Bryostatins 10 and 11; Pettit GR, Kamano Y, Herald CL. J Org Chem. 1987;52:2848–2854.Bryostatins 12 and 13: Pettit GR, Leet JE, Herald CL, Kamano Y, Boettner FE, Baczynskyj L, Nieman RA. J Org Chem. 1987;52:2854–2860.Bryostatins 14 and 15: Pettit GR, Gao F, Sengupta D, Coll JC, Herald CL, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Van Camp JR, Rudloe JJ, Nieman RA. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:3601–3614.Bryostatins 16–18: Pettit GR, Gao F, Blumberg PM, Herald CL, Coll JC, Kamano Y, Lewin NE, Schmidt JM, Chapuis J-C. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:286–289. doi: 10.1021/np960100b.Bryostatin 19: Lin H, Yao X, Yi Y, Li X, Wu H. Zhongguo Haiyang Yaowu. 1998;17:1–6.Bryostatin 20: Lopanik N, Gustafson KR, Lindquist N. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1412–1414. doi: 10.1021/np040007k.

- 3.For recent reviews, see: Hale KJ, Manaviazar S. Chemistry: An Asian J. 2010;5:704–754. doi: 10.1002/asia.200900634.and earlier references cited therein.

- 4.Total synthesis of bryostatins: bryostatin 7: Kageyama M, Tamura T, Nantz MH, Roberts JC, Somfai P, Whritenour DC, Masamune S. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7407–7408.and references cited therein; bryostatin 2: Evans DA, Carter PH, Carreira EM, Charette AB, Prunet JA, Lautens M. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7540–7552.and references cited therein; bryostatin 3: Ohmori K, Ogawa Y, Obitsu T, Ishikawa Y, Nishiyama S, Yamamura S. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2000;39:2290–2294.and references cited therein; bryostatin 16: Trost BM, Dong G. Nature. 2008;456:485–488. doi: 10.1038/nature07543.formal synthesis of bryostatin 7: Manaviazar S, Frigerio M, Bhatia GS, Hummersone MG, Aliev AE, Hale KJ. Org Lett. 2006;8:4477–4480. doi: 10.1021/ol061626i.and references cited therein.

- 5.For bryostatin analogue synthesis, see: Wender PA, DeChristopher BA, Schrier AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6658–6659. doi: 10.1021/ja8015632.and references cited therein; Keck GE, Pondel YB, Rudra A, Stephens JC, Kedei N, Lewin NE, Peach ML, Blumberg PM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010:4580–4584. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001200.and references cited therein.

- 6.For recent works on bryostatin, see: Lu Y, Krische MJ. Org Lett. 2009;11:3108–3111. doi: 10.1021/ol901096d.Voight EA, Seradj H, Roethles PA, Burke SD. Org Lett. 2004;6:4045–4048. doi: 10.1021/ol0483044.Vakalopoulos A, Lampe TFJ, Hoffmann HMR. Org Lett. 2001;3:929–932. doi: 10.1021/ol015551o.Kiyooka S, Maeda H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1997;8:3371.

- 7.(a) Nicolaou KC, Bulger PG, Sarlah D. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:4490–4527. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brenneman JB, Martin SF. Curr Org Chem. 2005;9:1535–1549. [Google Scholar]; (c) Martin SF. Pure Appl Chem. 2005;77:1207–1212. [Google Scholar]; (d) Grubbs RH, Trnka TM. In: Ruthenium in Organic Synthesis. Murahashi S-H, editor. WILEY-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hoveyda AH, Schrock RR. In: Organic Synthesis Highlights V. Schmalz H-G, Wirth T, editors. WILEY-VCH; Weinheim: 2003. pp. 210–229. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Synthesis of compound 5 was described in our previous paper, part 1.

- 9.Trost BM, Yang H, Wuitschik G. Org Lett. 2005;7:4761–4764. doi: 10.1021/ol0520065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Souza MVN. Mini-Reviews in Organic Chemistry. 2006;3:155–165. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blakemore PR, Browder CC, Hong J, Lincoln CM, Nagornyy PA, Robarge LA, Wardrop DJ, White JD. J Org Chem. 2005;70:5449–5460. doi: 10.1021/jo0503862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiina I, Shibata J, Ibuka R, Imai Y, Mukaiyama T. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2001;74:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.For use of a similar Mukaiyama reaction/anti-reduction to construct bryostatin C1-C7 fragment, see reference 4b.

- 14.Evans DA, Chapman KT, Carreira EM. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:3560–3578. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCluskey A, Muntari IWM, Young DJ. J Org Chem. 2001;66:7811–7817. doi: 10.1021/jo015904x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair V, Ros S, Jayan CN, Pillai BS. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:1959–1982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Otera J, Ioka S, Nozaki H. J Org Chem. 1989;54:4013–4014. [Google Scholar]; (b) Otera J, Yano T, Kawabata A, Nozaki H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:2383–2386. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The appearance of two methyl peaks at 3.33 ppm (assigned to the methyl ester methyl) and 2.83 ppm (assigned to the methyl ketal methyl) in 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6), the disappearance of a ketone resonance at 212.7 ppm in 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) for 31, and changes in IR (two peaks at 1736 and 1705 cm−1 for 31, one peak at 1734 cm−1 for 32) indicated the methyl ketal formation.

- 19.Bartlett PA, Johnson WS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970;23:4459–4462. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolaou KC, Estrada AA, Zak M, Lee SH, Safina BS. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:1378–1382. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qing FL, Yue XJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:8067–8070. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The product 37 was not stable under the reaction conditions due to the migration of the C20 acetate to the C17 hydroxyl group.

- 23.Petasis NA, Bzowej EI. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6392–6394. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Shiina I, Kubota M, Oshiumi H, Hashizume M. J Org Chem. 2004;69:1822–1830. doi: 10.1021/jo030367x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shiina I, Kubota M, Ibuka R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:7535–7539. [Google Scholar]; (c) Shiina I, Ibuka R, Kubota M. Chem Lett. 2002:286–287. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The reaction was clean by TLC analysis; the fate of the rest of the acid 36 was not clear.

- 26.Garber SB, Kingsbury JS, Gray BL, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:8168–8179. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conrad JC, Parnas HH, Snelgrove JL, Fogg DE. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11882–11883. doi: 10.1021/ja042736s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ball M, Bradshaw BJ, Dumeunier R, Gregson TJ, MacCormick S, Omori H, Thomas EJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:2223–2227. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The same trend is also observed in the examples presented by Nicolaou and co-workers, in which α-heteroatoms speed up the hydrolysis of methyl esters with (CH3)3SnOH. See ref 20.

- 30.Relay ring-closing metathesis (RRCM) was first reported by Hoye to overcome the difficulty related to low reactivity of alkenes, see: Hoye TR, Jeffrey CS, Tennakoon MA, Wang J, Zhao H. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10210–10211. doi: 10.1021/ja046385t.This strategy was later used by Wang and Porco et al in their total synthesis of oximidine III, see: Wang X, Bowman EJ, Bowman BJ, Porco JA., Jr Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:3601–3605. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460042.

- 31.Okazoe T, Takai K, Utimoto K. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:951–953. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatterjee AK, Choi TL, Sanders DP, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11360–11370. doi: 10.1021/ja0214882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takai K, Nitta K, Utimoto K. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:7408–7410. doi: 10.1021/ja00279a068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Negishi E-i, Zeng X, Tan Z, Qian M, Hu Q, Huang Z. In: Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. 2. de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. WILEY-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. pp. 815–889. [Google Scholar]; (b) Negishi E. Acc Chem Res. 1982;15:340–348. [Google Scholar]

- 35.A green lot from Alfa in the Trost group dry box led to the consumption of 38 in about 5 h. However, the product was obtained as a nearly 1:1 mixture of vinyl iodide 60 and terminal olefin 40 in about 50% yield. Anhydrous 99.99% CrCl2 from Aldrich (an off-white powder) gave a slower reaction without formation of the terminal olefin 40.

- 36.Compounds 66 and 67 could still lead to bryostatin if they undergo further reaction with Ru-alkylidene catalysts. However, treatment of macrocycle 66 and 67 under forced metathesis conditions did not provide any desired 26-membered product.

- 37.Epothilone D and discodermolide display IC50 values of 10 and 240 nM, respectively, in the same assay; see: Hearn BR, Zhang D, Li Y, Myles DC. Org Lett. 2006;8:3057. doi: 10.1021/ol061087h.Shaw SJ, Sundermann KF, Burlingame MA, Myles DC, Freeze BS, Xian M, Brouard I, Smith AB., III J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6532. doi: 10.1021/ja051185i.

- 38.For a recent review, see: Trost BM, Frederiksen MU, Rudd MT. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:6630–6666. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500136.

- 39.Large quantities of 74 are readily available in two steps from commercially available inexpensive 2,2-dimethyl-propane-1,3-diol, see reference 4. Small quantities of 74 are available from SALOR.

- 40.This was adapted from a procedure reported earlier by Wender et al, see: Wender PA, Baryza JL, Bennett CE, Bi FC, Brenner SE, Clarke MO, Horan JC, Kan C, Lacôte E, Nell PG, Turner TM. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13648–13649. doi: 10.1021/ja027509+.

- 41.Lin MJ, Loh TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13042–13043. doi: 10.1021/ja037410i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.High quality of Dess-Martin periodinane was required for this oxidation. For Dess-Martin oxidation, see: Dess DB, Martin JC. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:7277–7287.

- 43.For a review, see: Corey EJ, Helal JC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1998;37:1986–2012. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<1986::AID-ANIE1986>3.0.CO;2-Z.

- 44.Ketone 77 decomposed when treated with silica gel.

- 45.For reviews, see: Wadsworth WS., Jr Org React. 1977;25:73–253.Boutagy J, Thomas R. Chem Rev. 1974;74:87–99.Kelly SE. Comp Org Syn. 1991;1:729–817.Maryanoff BE, Reitz AB. Chem Rev. 1989;89:863–927.

- 46.Formation of some uncyclized product was observed.

- 47.Roth GJ, Liepold B, Müller SG, Bestmann HJ. Synthesis. 2004:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trost BM, Frontier AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:11727–11728. [Google Scholar]

- 49.For a gold-catalyzed 5-exo cyclization with alcohols as nucleophiles, see: Liu Y, Song F, Song Z, Liu M, Yan B. Org Lett. 2005;7:5409–5412. doi: 10.1021/ol052160r.for a cationic gold-catalyzed ketal formation, see: Liu B, De Brabander JK. Org Lett. 2006;8:4907–4910. doi: 10.1021/ol0619819.

- 50.For a recent review on gold catalysis, see: Muzart J. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:5815–5849.