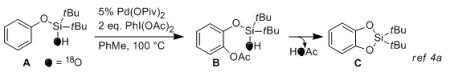

Transition metal-catalyzed C–H functionalizations have emerged as a powerful tool for the synthetic community.1 One common strategy involves the use of directing groups to achieve high reactivity and selectivity.1d-g As a broad spectrum of C–H functionalizations becomes a toolkit of choice, the expansion of substrate scope is therefore in a high demand. Recently, the employment of removable and/or modifiable directing groups has allowed an orthogonal diversification of C–H functionalized products.2 This strategy illuminates an avenue for a quick functionalization of products obtained via C–H functionalization. Along the line of our development on silicon-tethered removable/modifiable directing groups,3 we have shown that silanol4 acts as a traceless directing group for the synthesis of catechols from phenols.4a Herein, we wish to report the Pd-catalyzed, modifiable benzylsilanol-directed aromatic C–H oxygenation towards oxasilacycles, versatile intermediates for organic synthesis (vide infra).

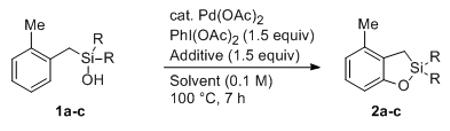

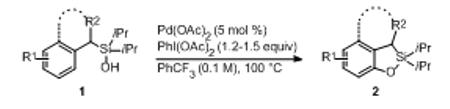

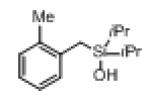

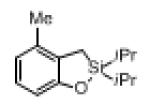

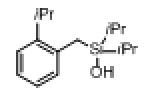

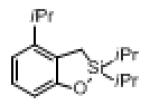

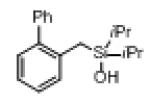

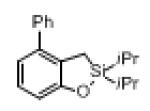

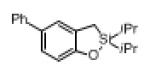

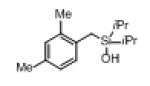

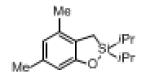

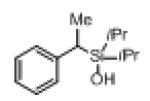

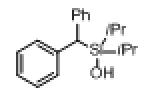

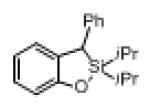

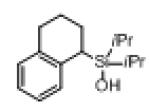

Carbon-based silicon tethers have been shown to exhibit a high degree of diversification.3,5 Thus, we started by searching a suitable carbon-based organosilanol for our method design. Given the similarity between silanol and alcohol and the generality of hydroxyl-directed C–H oxygenation6 reaction developed by Yu,7 three benzyl-bound silanols8 were tested under Yu’s oxidative C–O cyclization conditions (Table 1). Dimethylsilanol 1a, a well-established nucleophilic component in Hiyama-Denmark cross-coupling reaction,9 was tested first. However, the reaction with PhI(OAc)2 and Li2CO3 in the presence of 10 mol % Pd(OAc)2 in DCE at 100 °C led to decomposition of starting material, providing only trace amounts of cyclized product 2a (entry 1). Likewise, diphenylsilanol 1b10 also decomposed under these conditions (entry 2). However, bulkier diisopropyl benzylsilanol 1c, which was previously reported in an oxidative Heck reaction,4c was stable yet reactive enough under the C–O cyclization conditions to produce five-membered oxasilacycle 2c in 35% GC yield (entry 3). The reactions under base-free conditions usually afforded higher yields of 2c (entries 3-6). Performing the reaction in PhCF3 resulted in an increased yield (entry 7). The catalyst loading was reduced to 5 mol % without loss of efficiency (entry 9). Employment of Pd(OPiv)2, which was previously found superior for phenoxysilanol-directed catechol synthesis,4a resulted in a reduced yield (entry 10).11

Table 1.

Optimization of Reaction Conditions.

| # | Substrate | Pd [mol %] | Additive | Solvent | Yield [%][a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a (R=Me) | 10 | Li2CO3 | DCE | trace |

| 2 | 1b (R=Ph) | 10 | Li2CO3 | DCE | 0 |

| 3 | 1c (R=iPr) | 10 | Li2CO3 | DCE | 35 |

| 4 | 1c | 10 | none | DCE | 46 |

| 5 | 1c | 10 | Li2CO3 | PhMe | 42 |

| 6 | 1c | 10 | none | PhMe | 54 |

| 7 | 1c | 10 | none | PhCF3 | 73 |

| 8[b] | 1c | 10 | none | PhMe | 49 |

| 9 | 1c | 5 | none | PhCF3 | 73 |

| 10[c] | 1c | 5 | none | PhCF3 | 60 |

GC yields.

The reaction concentration was 0.05 M.

5 mol % Pd(OPiv)2 was used as the catalyst.

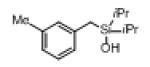

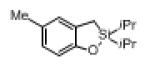

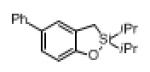

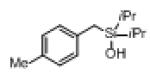

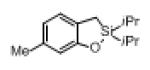

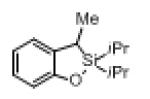

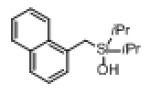

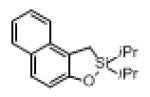

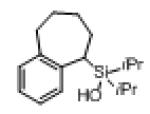

Next, the generality of this transformation was examined (Table 2). It was found that both alkyl and aryl groups can be tolerated at ortho-, meta- and para-positions of aromatic rings (entries 1-7). For meta-substituted substrates 1i-j, the oxygenation selectively goes to the less hindered C–H site. Besides, silanols 1m and 1n substituted at the benzylic position were also competent reactants in this transformation (entries 8-9). Moreover, naphthalene-based silanol 1o smoothly underwent oxidative cyclization to produce tricyclic product in 70% yield. Remarkably, tetralin (1p), chroman (1q), and benzosuberan (1r) derived silanols were efficiently transformed into their corresponding tricyclic products in good to high yields (entries 11-13). It deserves mentioning that the reaction can be easily scaled up to gram scale with comparable yields (entry 7).

Table 2.

Reaction Scope of Silanol-Directed C–H Oxygenation.

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield [%][a] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

1c |

|

2c | 72 |

| 2 |

|

1g |

|

2g | 87 |

| 3 |

|

1h |

|

2h | 74 |

| 4 |

|

1i |

|

2i | 50[b],[c] (72) |

| 5 |

|

1j |

|

2j | (71)[c] |

| 6 |

|

1k |

|

2k | (66) |

| 7 |

|

1l |

|

2l | 68 (85) 83[b],[d] |

| 8 |

|

1m |

|

2m | 69[b] (80) |

| 9 |

|

1n |

|

2n | 58 (76) |

| 10 |

|

1o |

|

2o | 70 |

| 11 |

|

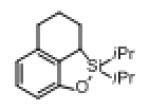

1p |

|

2p | 77 |

| 12 |

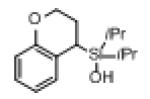

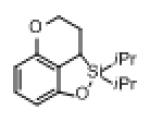

|

1q |

|

2q | 58 |

| 13 |

|

1r |

|

2r | 90 |

Isolated by column chromatography on Florisil®. 1H NMR yields are provided in the parentheses.

Isolated by Kugelrohr distillation.

Regioselectivity is >20:1.

Gram scale (5 mmol), isolated with 92% purity.

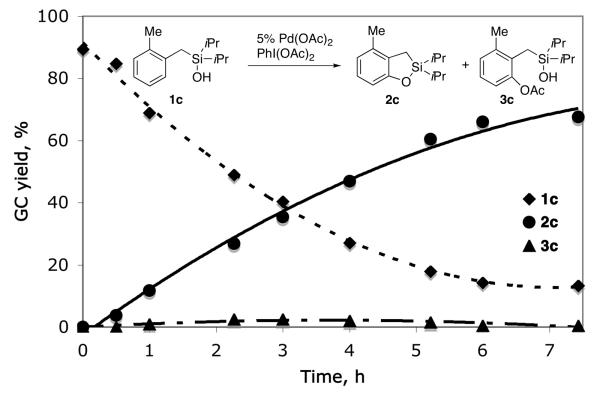

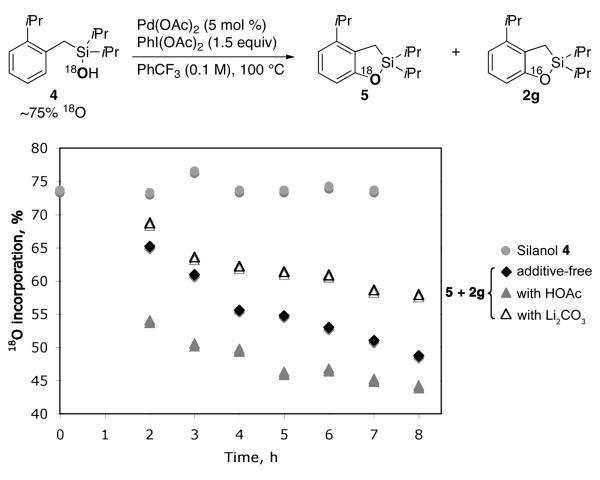

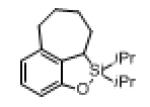

In order to verify whether this transformation, similarly to the previously developed silanol-directed oxygenation reaction (eq 1),4a proceeds via an acetoxylated intermediate of type B, we performed a GC monitoring of the oxygenation reaction of 1c. Surprisingly, the reaction profile showed no formation of substantial amounts of acetoxylated intermediate 3c (< 3%) during the reaction course (Figure 1). Next, 18O-labeled silanol 4 was subjected to the reaction under the standard conditions. It was found that, accompanied by the formation of 2g, cyclized product 5 with 18O label was indeed formed. Moreover, the amount of 18O label in the cyclized products was lower than that of 4 and gradually decreased as the reaction proceeded. The test experiments indicated no 16O/18O scrambling in the starting silanol 4 throughout the reaction course occurred (Figure 2). Likewise, prolong (overnight) heating of the completed reaction did not change 18O-label incorporation in the cyclized products. We envisioned that the in situ generation and accumulation of HOAc13 during the reaction could be responsible for the observed downhill trend of 18O-label incorporation in the products. To verify the role of HOAc, we performed additional experiments with exogenous HOAc and in the presence of base (Li2CO3). As expected, the abundance of 18O label in the products was substantially lower under acidic conditions, but higher under the basic media compared to that under the additive-free reaction conditions (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Reaction profile.12 The reaction was monitored by GC/MS with tetradecane as the internal standard.

Figure 2.

The abundance of 18O incorporation in the starting silanol 4 shown with solid circles, the abundance of 18O incorporation in the cyclized products (additive-free conditions with solid squares; acidic conditions with solid triangles; basic conditions with hollow triangles).

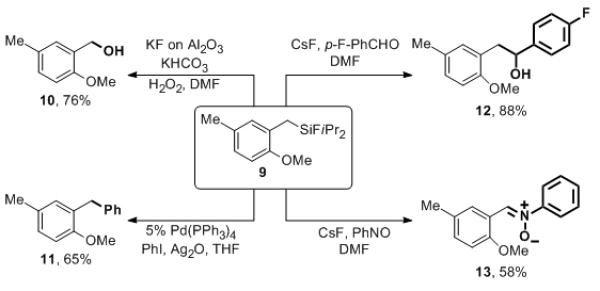

Although the mechanistic details of this transformation are still unclear, the above observations indicate on two possible general pathways (Scheme 1). According to the first path, the partial loss of 18O label in the products suggests the possibility of the previously proposed reaction route, featuring an acetoxylation/cyclization sequence (path A).4a Alternatively, the formation of 18O-enriched product 5 implies the possibility of a direct reductive C–O cyclization7a (path B).14

Scheme 1.

Possible reaction pathways.

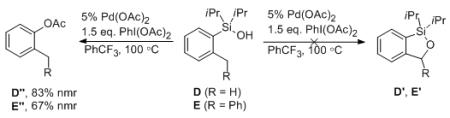

To test the feasibility of this oxygenation reaction on sp3 C–H systems, silanols D and E were subjected to the standard oxygenation reaction conditions. However, instead of benzylic C–H activation reaction toward silacycles D’ and E’, an ipso-acetoxydesilylation occurred, producing acyloxy benzenes D” and E” in 83% and 67% yields, respectively (eq 2). These results suggest that this method is effective for aromatic C–H oxygenation reaction only.15

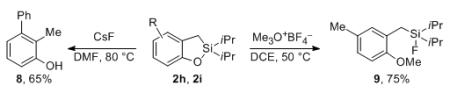

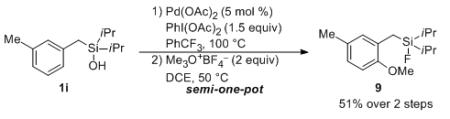

We envisioned that the synthesized cyclic molecules, containing an easily cleavable Si–O bond and a potentially modifiable C–Si bond, could serve as a precursor for a variety of valuable products. Indeed, Tamao has showed in a single example that this type of oxasilacycles is useful to achieve functional group-compatible Kumada cross-coupling reactions.16 However, their synthetic usefulness has not yet been extensively exploited. Encouraged by our previous success on the modification of silicon-tethered directing groups,3 we were interested to investigate the synthetic potential of oxasilacycles as useful building blocks in organic synthesis. As expected, desilylation of cyclic product 2h with CsF in DMF resulted in phenol 8 in good yield (eq 3). In addition, thermodynamically stable cyclic structure 2 can be efficiently opened up with Meerwein salt in a single step (eq 3). In this hitherto unknown transformation, which we proposed to proceed via a cationic concerted asynchronous mechanism (supported by DFT calculations),12 trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate plays a double duty: it delivers the methyl cation to the oxygen atom and the fluoride anion to the silicon atom. The oxygenation and ring opening steps could also be performed in a semi-one-pot manner, affording compound 9 from silanol 1i in 51% overall yield (eq 4).

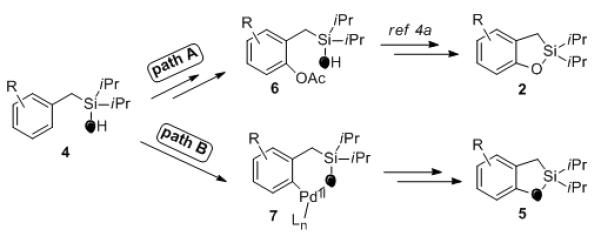

The resulted fluorosilane 9 opened up broader opportunities for the subsequent modifications. As illustrated in Scheme 2, Tamao oxidation17 of 9 provided benzyl alcohol 10 in 76% yield. Fluoride-free Hiyama-Denmark cross-coupling of 9 with phenyl iodide, under conditions reported by Itami and Yoshida,18 afforded diarylmethane derivative 11 in 65% yield. Moreover, fluorosilane 9 in the presence of CsF can be employed as an equivalent of Grignard reagent in the reaction with aldehydes.19 Finally, an unprecedented transformation en route to nitrone derivative 13 was discovered upon treatment of benzylsilane 9 with nitrosobenzene in the presence of CsF.12

Scheme 2.

Further transformations.

In summary, we have developed Pd-catalyzed, benzylsilanol-directed ortho C–H oxygenation of aromatic rings. This method allows efficient synthesis of oxasilacycles, which are valuable synthetic intermediates. The synthetic usefulness was highlighted by an efficient removal of the silanol directing group and by its conversion into a variety of valuable functionalities. These transformations include known Tamao oxidation, Hiyama-Denmark cross-coupling, and nucleophilic addition, as well as unprecedented Meerwein salt-mediated ring-opening of oxasilacycles and nitrone formation from a benzylsilane and a nitroso compound.

Experimental Section

General procedure

An oven dried Wheaton V-vial (10 mL), containing a stirring bar, was charged with benzylsilanols 1 (0.5 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (5.6 mg, 0.025 mmol), and PhI(OAc)2 (0.6 – 0.75 mmol) under N2 atmosphere. Dry α,α,α-trifluorotoluene (5 mL) was added via syringes and the reaction vessel was capped with pressure screw cap. The reaction mixture was heated at 100 °C for 7 h. The resulting mixture was cooled down to room temperature and filtered through a short layer of celite plug with the aid of EtOAc. The filtrate was concentrated under a reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography on Florisil® (eluent: hexanes/EtOAc) affording the corresponding cyclized products 2.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The support of the National Institutes of Health (GM-64444) is gratefully acknowledged. C. Huang thanks the financial support from the Moriarty Graduate Fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/ or from the author.

References

- [1]a).Godula K, Sames D. Science. 2006;312:67. doi: 10.1126/science.1114731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kakiuchi F, Chatani N. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003;345:1077. [Google Scholar]; c) Daugulis O, Do H-Q, Shabashov D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1074. doi: 10.1021/ar9000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yu J-Q, Giri R, Chen X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:4041. doi: 10.1039/b611094k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Ackermann L. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2007;24:35. [Google Scholar]; f) Chen X, Engle KM, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:5196. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5094. [Google Scholar]; g) Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1147. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Campeau L-C, Stuart DR, Fagnou K. Aldrichimica Acta. 2007;40:35. [Google Scholar]; i) Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:174. doi: 10.1021/cr0509760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Colby DA, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:624. doi: 10.1021/cr900005n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) McGlacken GP, Bateman LM. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2447. doi: 10.1039/b805701j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Mkhalid IAI, Barnard JH, Marder TB, Murphy JM, Hartwig JF. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:890. doi: 10.1021/cr900206p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Ashenhurst JA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:540. doi: 10.1039/b907809f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n) Beccalli EM, Broggini G, Martinelli M, Sottocornola S. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5318. doi: 10.1021/cr068006f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o) Sun C-L, Li B-J, Shi Z-J. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:677. doi: 10.1039/b908581e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p) Satoh T, Miura M. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:11212. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; q) Sun C-L, Li B-J, Shi Z-J. Chem. Rev. 2010;111:1293. doi: 10.1021/cr100198w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; r) Wencel-Delord J, Droge T, Liu F, Glorius F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4740. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15083a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].For a review, see: Rousseau G, Breit B. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:2498. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006139. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:2450. For recent examples, see: Ihara H, Suginome M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7502. doi: 10.1021/ja902314v. Neufeldt SR, Sanford MS. Org. Lett. 2009;12:532. doi: 10.1021/ol902720d. Richter H, Beckendorf S, Mancheño OG. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:295. Bedford RB, Coles SJ, Hursthouse MB, Limmert ME. Angew. Chem. 2003;115:116. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390037. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:112. García-Rubia A, Fernández-Ibáñez MÁ, Gómez Arrayás R, Carretero JC. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:3567. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003633. Ackermann L, Diers E, Manvar A. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1154. doi: 10.1021/ol3000876. Simmons EM, Hartwig JF. Nature. 2012;483:70. doi: 10.1038/nature10785.

- [3]a).Chernyak N, Dudnik AS, Huang C, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8270. doi: 10.1021/ja1033167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dudnik AS, Chernyak N, Huang C, Gevorgyan V. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:8911. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:8729. [Google Scholar]; c) Huang C, Chernyak N, Dudnik AS, Gevorgyan V. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:1285. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gulevich AV, Melkonyan FS, Sarkar D, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5528. doi: 10.1021/ja3010545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].For silanol directed oxygenation, see: Huang C, Ghavtadze N, Chattopadhyay B, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17630. doi: 10.1021/ja208572v. For silanol directed olefination, see: Huang C, Chattopadhyay B, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12406. doi: 10.1021/ja204924j. Wang C, Ge H. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:14371. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103171. For a related highlight, see: Mewald M, Schiffner JA, Oestreich M. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:1797. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107859. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:1763.

- [5].Bracegirdle S, Anderson EA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:4114. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00007h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].For reviews on transition metal-catalyzed C–H oxygenation of arenes, see: Sehnal P, Taylor RJK, Fairlamb IJS. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:824. doi: 10.1021/cr9003242. Alonso DA, Nájera C, Pastor IM, Yus M. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:5274. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000470. Enthaler S, Company A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4912. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15085e.

- [7]a).Wang X, Lu Y, Dai H-X, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12203. doi: 10.1021/ja105366u. For related phenol-directed C–O cyclization reactions, see: Xiao B, Gong T-J, Liu Z-J, Liu J-H, Luo D-F, Xu J, Liu L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9250. doi: 10.1021/ja203335u. Wei Y, Yoshikai N. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5504. doi: 10.1021/ol202229w. Zhao J, Wang Y, He Y, Liu L, Zhu Q. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1078. doi: 10.1021/ol203442a.

- [8].When the project was underway, a paper describing the employment of benzylsilanol directing group in ortho-vinylation reaction has been published. See: ref 4c.

- [9].Denmark SE, Regens CS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1486. doi: 10.1021/ar800037p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].It was reported that diphenylsilane was a stable silicon tether in an Ir-catalyzed cyclization reaction. See: Kuznetsov A, Gevorgyan V. Org. Lett. 2012;14:914. doi: 10.1021/ol203428c.

- [11].Attempts on oxygenative cyclization of homologous silanols 1d-f failed. 1d = PhSiiPr2OH, 1e = Ph(CH2)2SiiPr2OH, 1f = Ph(CH2)3SiiPr2OH.

- [12].See Supporting Information for details.

- [13].It has been shown that HOAc could influence the reductive elimination pathways from PdIV centers. For a recent example, see: He G, Zhao Y, Zhang S, Lu C, Chen G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:3. doi: 10.1021/ja210660g.

- [14].Most likely, both oxidation pathways operate via high oxidation state Pd intermediates. For involvement of bimetallic PdIII species in C–H activation, see: Powers DC, Geibel MAL, Klein JEMN, Ritter T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17050. doi: 10.1021/ja906935c. Powers DC, Ritter T. Acc. Chem. Res. doi: 10.1021/ar2001974. DOI: 10.1021/ar2001974. For involvement of PdIV intermediates, see: Muñiz K. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:9576. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9412. Yoneyama T, Crabtree RH. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1996;108:35. Xu L-M, Li B-J, Yang Z, Shi Z-J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:712. doi: 10.1039/b809912j. f) See also refs 1d, 1g.

- [15].For other attempts on different modes of sp3 C–H activation, see Supporting Information.

- [16]a).Son E-C, Tsuji H, Saeki T, Tamao K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2006;79:492. For a related concept in Hiyama coupling reaction, see also: Nakao Y, Imanaka H, Sahoo AK, Yada A, Hiyama T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6952. doi: 10.1021/ja051281j.

- [17]a).Tamao K, Kumada M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:321. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Itami K, Mineno M, Kamei T, Yoshida J-i. Org. Lett. 2002;4:3635. doi: 10.1021/ol026573t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ricci A, Fiorenza M, Grifagni MA, Bartolini G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:5079. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.