Abstract

Protein misfolding and aggregation play important roles in many physiological processes. These include pathological protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases and biopharmaceutical protein aggregation during production in mammalian cells. In order to develop a simple non-invasive assay for protein misfolding and aggregation in mammalian cells, the folding reporter green fluorescent protein (GFP) system, originally developed for bacterial cells, was evaluated. As a folding reporter, GFP was fused to the C-terminus of a panel of human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) mutants with varying misfolding/aggregation propensities. Flow cytometric analysis of transfected HEK293T and NSC-34 cells revealed that the mean fluorescence intensities of the cells expressing GFP fusion of SOD1 variants exhibit an inverse correlation with the misfolding/aggregation propensities of the four SOD1 variants. Our results support the hypothesis that the extent of misfolding/aggregation of a target protein in mammalian cells can be quantitatively estimated by measuring the mean fluorescence intensity of the cells expressing GFP fusion. The assay method developed here will facilitate understanding of aggregation process of SOD1 variants and identifying aggregation inhibitors. The method also has great promise for misfolding/ aggregation study of other proteins in mammalian cells.

Keywords: green fluorescence protein, protein aggregation, protein misfolding, SOD1

1. Introduction

Protein misfolding and aggregation are often causative to the onset of numerous neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [1–7]. Therefore, modulating protein misfolding and aggregation are generally considered a promising strategy to treat neurodegenerative diseases [8–14]. Furthermore, intracellular aggregate formation and misfolding of biopharmaceuticals, such as α-galactosidase, α-glucosidase, antithrombine III, and angiopoietin-1 in mammalian cells are often obstacles in achieving high yield production of biopharmaceuticals [15–19]. Therefore, quantitative analysis of protein misfolding and aggregation in mammalian cells will facilitate enhanced understanding of the molecular mechanisms for various human diseases and improve recombinant protein quality produced in mammalian cells. In his pioneering work, Johnson et al. reported a novel split GFP complementation system to monitor aggregation of mutant tau proteins, which is associated with Alzheimer’s disease, in mammalian cells [20]. The split GFP complementation is based on the assumption that a small GFP fragment fused to a target protein in aggregates has very limited accessibility to a large GFP fragment. Therefore, this method may not be effective when a target protein forms loosely packed aggregates enabling the small GFP fragment access to the large fragment. However, efficient complementation of the split GFP fragments requires a delicate control of relative (and absolute) expression levels of two split GFP fragments [20]. Therefore, the need remains to develop a simple but effective quantitative assay for protein misfolding and aggregation in mammalian cells. In order to address this need, intact GFP fusion to a target protein, originally developed to monitor protein aggregation/misfolding in bacterial cells, was reevaluated in mammalian cells.

For bacterial and yeast cells, this simple assay method for protein misfolding and aggregation has proven effective [21–25]. GFP folding for fluorescence is directly affected by folding of a target protein fused to the N-terminus of GFP. Any deviations from a correctly folded target protein structure such as misfolding and aggregation lead to a loss in the fluorescence of cells expressing the GFP fusion of the target protein in bacteria. With the aid of analytic tools that measure cellular fluorescence, including fluorescence microplate reader and flow cytometer, the extent of the deviation from correctly folded target protein structure can be quantitatively determined. However, GFP fusion for quantitative analysis of protein misfolding and aggregation has thus far been restricted to bacterial systems. Considering the general utility of GFP in both bacteria and mammalian cells as a reporter of cellular processes including protein expression, degradation, localization, and proteolysis [26–28], we hypothesize that GFP fusion to the C-terminus of a target protein is also effective in quantitatively monitoring protein misfolding and aggregation in mammalian cells.

In order to validate the GFP fusion method’s capacity to monitor protein misfolding/aggregation in mammalian cells, human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) mutants were chosen due to several features of SOD1. First, SOD1 mutants form intracellular aggregates in mammalian cells in a relatively short period time, usually within two to three days post-transfection [29]. Second, SOD1 mutants are known to form loosely packed aggregates inside mammalian cells [30] and so the split GFP complementation may not be effective in monitoring protein aggregation. Third, SOD1 mutants are associated with neurodegenerative disorder familial form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (fALS) [10, 31, 32]. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), often referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that attacks and inevitably leads to the death of motor neurons in the brain, brain stem and spinal cord [31]. There are over one hundred natural SOD1 mutants with varying misfolding/aggregation propensities, though wild-type SOD1 forms a stable dimer [32–36]. It has been proposed that aggregation of the mutant SOD1 is linked to the gain of toxic function, eventually leading to the development of ALS. The most common mutation among mutant SOD1-associated fALS patients in the United States is alanine to valine at 4th residue (A4V). Researchers have biophysically characterized this mutation and have found that this mutation causes substantial destabilization at the dimer interface and the rapid development of aggregates in vitro and in vivo [33, 37, 38]. The progression of fALS has been linked to the level of aggregate formation in the spinal cord, implying SOD1 aggregation a potential drug target for preventing or curing ALS [39]. In order to screen molecules that inhibit mutant SOD1 aggregation, a simple, but effective way to monitor mutant SOD1 aggregation needs to be developed. Stevens et al. demonstrated that GFP tagging does not substantially alter properties of SOD1 variants inside cells using fluorescence microscopy [40]. Although this result supports the idea that GFP is safe to fuse to SOD1 variants, the fluorescence microscopy technique is not suitable to quantitatively monitor aggregation of mutant SOD1. Therefore, we investigated whether flow cytometric analysis can be employed to quantitatively monitor aggregation of mutant SOD1s.

We chose wild-type SOD1 (SOD1WT) and three aggregation-prone SOD1 mutants (SOD1A4V, SOD1A4V/C57S, and SOD1A4V/C111S) as model proteins. As described earlier, SOD1A4V is known to form aggregates in vitro and in vivo [33, 37, 38]. Among four cysteines (Cys6, Cys57, Cys111, and Cys146), two free cysteines Cys6 and Cys111 are known to form inter-molecular disulfide bond network with other SOD1 monomers containing free C6 or C111 during the aggregation process [29, 41–43]. Therefore, Cys to Ser mutation at residue 111 of SOD1 reduces SOD1 aggregation [29, 42]. SOD1A4V/C111S mutant is more stable and soluble than SOD1A4V mutant in cultured cells and in vitro [41, 43, 44], indicating that SOD1A4V/C111S has a lower misfolding/aggregation propensity than SOD1A4V. The other two cysteines, C57 and C147, are involved in an intra-subunit disulfide bond formation; an important post-translational modification of SOD1. It was reported that removing a Cys residue involved in the intra-subunit disulfide bond formation greatly destabilizes the protein and so enhances misfolding of the protein in cultured cells and in vitro [41, 44–46], indicating that the misfolding propensity of SOD1A4V/C57S is higher than that of SOD1A4V. In summary, for the four SOD1 mutants used in this study, the order of extent of deviations from correctly folded structure (misfolding/aggregation) is SOD1A4V/C57S > SOD1A4V > SOD1A4V/C111S > and SOD1WT.

Herein we investigate whether there is a direct correlation between misfolding/aggregation propensity of the four SOD1 variants and mean cellular fluorescence of transfected HEK293T cells expressing the corresponding SOD1 variant fused to GFP. Then, in order to generalize our hypothesis that GFP fusion is effective in quantitatively monitoring mammalian cell protein misfolding/aggregation, we also extend our studies to another cell line (neuroblastoma NSC-34 cells) and promoter (ubiquitin-C).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Anti-SOD1 polyclonal antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-α tubulin antibody was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Anti-rabbit antibody was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). HEK293T and NSC-34 cells were obtained from Invitrogen and CELLutions Biosystems (Burlington, Ontario, Canada), respectively. Restriction enzymes and DNA ligases were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted.

2.2 Construction of Expression Vectors

The EGFP gene is located to 3′ of either SOD1WT or SOD1A4V gene in pEGFP-N3-SOD1WT or pEGFP-N3-SOD1A4V plasmid, respectively [32]. In both plasmids, SOD1-EGFP fusion protein expression is under the control of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) constitutive promoter. Other detailed procedures to construct expression vectors are described in the Supplemental Information section.

2.3 Transfection of HEK293T and NSC-34 cells

HEK293T cells were cultured on 6-well plates at 37° C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/High Glucose (DMEM/High Glucose, Thermo Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 μg/mL of streptomycin sulfate and 100 units/ml of penicillin. NSC-34 cells were maintained in DMEM/12:1:1 modified containing 10% FBS. When the cells grew to 80–90% confluency, they were transfected with appropriate plasmids via calcium phosphate precipitation [47, 48]. All samples were tested in triplicate, unless otherwise described.

2.4 Fluorescence Microscopy

At two days after transfection, the transfected HEK293T cells cultured on the 6-well plates were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using a VistaVision Inverted Fluorescence Microscope (VWR, Radnor, PA). Fluorescence microscopic images of the cells were taken with a DV-2C digital camera equipped on the microscope at the same magnification and camera settings. The fluorescence excitation wavelength is between 420 and 485 and the emission wavelength is 515 nm. The number of cells in the fluorescence microscopy images was manually counted. The percentage of transfected cells exhibiting SOD1-EGFP aggregates was determined by dividing the number of aggregates-containing cells by the number of total cells analyzed.

2.5 Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cellular Fluorescence

After incubating the desired amount of time, the fluorescence intensities of the HEK293T and NSC-34 cells expressing SOD1 variant-EGFP fusion protein were measured using the C6 flow cytometer (Accuri, Ann Arbor, MI). To prepare the cells for flow cytometric analysis, the HEK 293T cells and NSC-34 cells were trypsinized, washed twice with phosphate buffered saline buffer (PBS; pH 7.4) and diluted ten-fold in PBS to prevent cell aggregation. The excitation wavelength was 488 nm and the fluorescence emission was detected at 585 nm. Only GFP positive cells were used to calculate the mean cellular fluorescence. Transfection efficiency was determined by dividing the number of fluorescence positive cells by the number of total cells analyzed. The mean cellular fluorescence intensities were obtained by analyzing 20,000 to 50,000 cells. Each sample was prepared in triplicate and cellular fluorescence indicates mean cellular fluorescence, unless otherwise noted. Student’s paired t-test was used for statistical analysis of fluorescence data. Gating strategy is described in Supplemental Information (Figure S1).

2.6 Dot-blotting

5×105 transfected HEK293T cells were trypsinized and centrifuged to obtain a cell pellet. The pellet was then washed with 1X PBS once and centrifuged to remove the buffer. The cell pellet was lysed in 100 μL of lysis buffer containing 100mM NaH2PO4, 10mM Tris-Cl, 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), and 8 M Urea at room temperature for 1 hour. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 14,000g for 30 minutes to remove the cell debris and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration of the cell lysate was determined using BCA kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Dot-blot assay of the cell lysate was performed as described earlier [13, 14] except antibodies used (anti-α tubulin and HRP-conjugated anti-GFP antibodies in this study). The blot images were captured using a BioSpectrum imaging system (UVP).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Fluorescence Microscopic Observation of Transfected HEK293T Cells Expressing SOD1 Variants

HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding each of the four SOD1-EGFP variants genes (SOD1WT-EGFP, SOD1A4V/C111S-EGFP, SOD1A4V-EGFP, and SOD1A4V/C57S-EGFP). At two days post-transfection, fluorescence images of the transfected cells were taken (Figure 1A). Transfected HEK293T cells expressing SOD1WT-EGFP were brightest among the four different transfected cells. The order of brightness of the transfected cells expressing four SOD1 variants fused to EGFP is SOD1WT > SOD1A4V/C111S > SOD1A4V > and SOD1A4V/C57S, which is consistent with the inverse order of misfolding/aggregation propensity of the four SOD1 variants in vitro and in cultured cells previously reported [41, 43, 44].

Figure 1. Fluorescence microscopy images of the transfected HEK293T cells expressing SOD1 variants fused to EGFP.

(A) Images of transfected HEK293T cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1WT, SOD1A4VC111S, SOD1A4V, and SOD1A4V/C57S taken at two days post-transfection. Transfection efficiency for each SOD1 variant was determined by calculating the percentage of GFP positive cells out of total cells analyzed using flow cytometry. Values represent means ± standard deviation (n = 3). Scale bars are 250 μm. (B) Magnified fluorescence microscopic images of the transfected HEK293T cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1WT and SOD1A4V. Arrows indicate the aggregates within the cell. Scale bars are 50 μm.

3.2 Flow Cytometric Analysis of Transfected HEK293T Cells Expressing SOD1 Variants

Fluorescence microscopic observation of cells expressing GFP fusion protein is a non-invasive method to qualitatively compare the fluorescence intensities of different cell samples but is not suitable for quantitative analysis. Therefore, we employed flow cytometric analysis of the transfected HEK293T cells to evaluate cellular fluorescence. At one and two days post-transfection of HEK293T cells with plasmids encoding four SOD1-EGFP fusion genes respectively, the mean fluorescence intensities of the four transfected cells were measured by flow cytometry (Figure 2A). The representative overlaid histograms of fluorescence of cells are shown in Figure S2 in Supplemental Information. In this article, the fluorescence intensities measured by flow cytometry indicate the mean cellular fluorescence intensities. As expected, the order of fluorescence intensity of the four transfected cells is SOD1WT > SOD1A4V/C111S > SOD1A4V > SOD1A4V/C57S, matching the inverse order of the misfolding/aggregation propensities of the four SOD1 variants. The cellular fluorescence intensity of SOD1A4V/C111S was significantly higher than that of SOD1A4V (P < 0.05), whereas the cellular fluorescence intensity of SOD1A4V/C57S was significantly lower than that of SOD1A4V (P < 0.001) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Comparison of the cellular fluorescence intensities and expression levels of EGFP fusion of SOD1 variants.

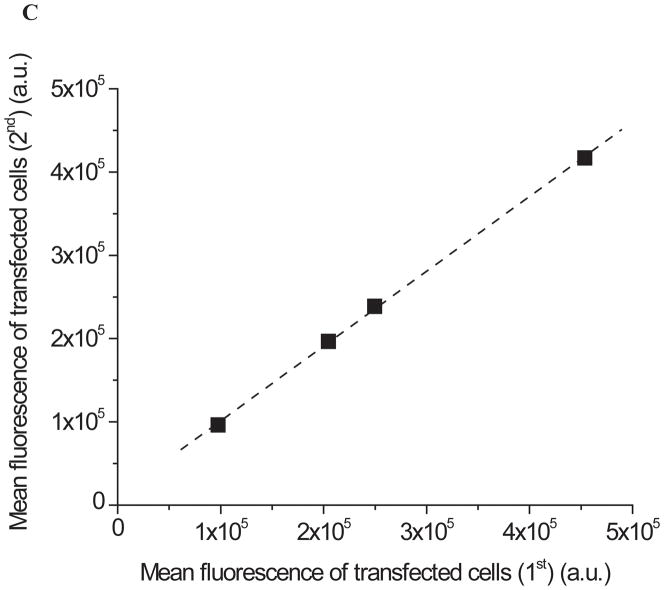

(A) Time course of fluorescence intensities of the transfected HEK293T cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1 variants. Fluorescence intensities of untransfected cells (day 0) and transfected cells expressing EGFP fusion of four SOD1 variants (SOD1WT, SOD1A4VC111S, SOD1A4V, and SOD1A4V/C57S) at day 1 and 2 were determined by flow cytometry. Values and error bars represent mean cellular fluorescence and standard deviations, respectively (n = 3). Two-sided Student’s t-tests were applied to the data (*: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.001). (B) Dot-blot images of the transited cell lysates of EGFP fusion of SOD1WT (WT), SOD1A4V/C111S (A4V/C111S), SOD1A4V. (A4V), and SOD1A4V/C57S (A4V/C57S) using anti-SOD1 polyclonal antibody. (α-tubulin; loading control) (C) Comparison of the mean cellular fluorescence of HEK293T cells expressing SOD1 variants that were transfected at two separate days. At two days post-transfection, cellular fluorescence of transfected HEK293T cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1 variants (SOD1WT, SOD1A4VC111S, SOD1A4V, and SOD1A4V/C57S) was determined by flow cytometry. The data were fitted to a straight line (R2 = 0.99). (a.u. = arbitrary unit) Numerical values of the mean cellular fluorescence intensities are shown in Table S1 in Supplemental Information.

Although flow cytometric analysis of cellular fluorescence is a very convenient way to obtain information on cellular processes, caution should be taken to directly correlate the cellular fluorescence intensities to protein misfolding/aggregation. Other factors such as transfection efficiency and expression level of a target protein can also affect the fluorescence intensity of transfected cells. First, effects of transfection efficiencies on cellular fluorescence were investigated. The transfection efficiencies of the four SOD1 variants were determined by flow cytometry. The transfection efficiency was calculated by dividing the number of GFP positive cells by the number of total cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Although the transfection efficiencies vary from 42% to 55%, the differences are not large enough to explain the differences in cellular fluorescence of the four different transfected cells, supporting the idea that intensity is related to SOD1 properties. The transfection efficiencies of SOD1A4V and SOD1A4V/C57S were 5 to 13% lower than those of SOD1WT and SOD1A4V/C111S, which is most likely due to the exclusion of some weak fluorescent cells in the samples. If the fluorescence intensity of the transfected cells are overlapped with that of untransfected cells (negative control), such weak fluorescent cells are not counted in determining the mean cellular fluorescence intensity after the background subtraction in flow cytometric analysis. According to the transfection efficiencies measured by flow cytometry (Figure 1), the maximum difference among the transfection efficiencies was 13%. However, this difference is too small to explain the more than 4-fold difference in the fluorescence intensities of cells expressing SOD1WT and SOD1A4V/C57S (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the lower transfection efficiency of SOD1A4V/C57S cell sample is most likely made by the exclusion of weakly fluorescent cells from the transfection efficiency calculation due to the background subtraction in data analysis. If the weak fluorescent cells were included to correct the transfection efficiency, the cellular fluorescence intensities would decrease, making the difference in the cellular fluorescence intensities between SOD1WT and SOD1A4V/C57S larger. Therefore, our results suggest that the low transfection efficiencies of SOD1A4V and SOD1A4V/C57S are not the major cause of their low cellular fluorescence.

Second, we investigated whether the differences in the cellular fluorescence intensities resulted from differences in the expression levels of SOD1 variants; because the mean fluorescence intensities of cells can change according to SOD1-GFP fusion protein expression level. Therefore, expression levels of four different SOD1-EGFP fusion proteins were compared using dot-blot assay using anti-SOD1 polyclonal antibody. Since HEK293T cells also express endogenous SOD1WT, we first compared the endogenous SOD1WT level in untransfected HEK293T cells and the total SOD1WT level in transfected HEK293T cells over-expressing SOD1WT-EGFP. As expected, anti-SOD1 immuno-reactivity of the untransfected cells was negligible compared to that of the transfected cells over-expressing SOD1WT-EGFP (Figure S3 in Supplemental Information). Therefore, we ignored endogenous SOD1WT expression level when over-expression levels of the four SOD1-EGFP fusion proteins are compared. Next, transfected cells expressing each of four SOD1-EGFP fusion proteins (SOD1WT-EGFP, SOD1A4V/C111S-EGFP, SOD1A4V-EGFP, and SOD1A4V/C57S-EGFP) were lysed and the total cell lysates were used for dot-blot assay. Anti-α tubulin antibody was used to ensure loading a comparable amount of the protein extracts to a nitrocellulose membrane (Figure 2B bottom). The immuno-reactivity of all four SOD1-EGFP fusion proteins was comparable (Figure 2A top), strongly indicating that the substantial differences in the cellular fluorescence do not result from differences in their expression levels.

Third, besides transfection efficiency and expression level, there might be other factors that affect cellular fluorescence intensities. If there are other critical factors affecting the cellular fluorescence intensities, the results may not be reproducible. In order to confirm the reproducibility of the results, transfection and cellular fluorescence measurement were performed on two separate days with a month gap. Then, the mean fluorescence intensities of the transfected cells obtained from two independent experiments were compared (Figure 2C). For the four SOD1-EGFP variants (SOD1WT-EGFP, SOD1A4V/C111S-EGFP, SOD1A4V-EGFP, and SOD1A4V/C57S-EGFP), there is a linear correlation between the cellular fluorescence intensities of the cells transfected on two separate days (R2 = 0.99), though there was a slight difference in the absolute fluorescence intensities (around 5%). Our results strongly indicate that the correlation between the cellular fluorescence intensities and the misfolding/aggregation propensities of the SOD1 variants is quite reproducible. However, since absolute fluorescence intensities of the transfected cells expressing EGFP fusion protein may vary each time, an accurate estimation of misfolding/aggregation status of a target protein requires a calibration using both highly stable and misfolding/aggregation-prone protein controls.

In order to compare the efficacy of EGFP fusion to that of split GFP complementation, split GFP complementation was performed on SOD1WT and SOD1A4V (experimental details are described in the Supplemental Information). The mean cellular fluorescence intensities of SOD1WT and SOD1A4V were not significantly different (Figure S4 in the supplemental Information), which is likely due to loosely packed structure of SOD1A4V aggregates [30] allowing access of a small fragment of GFP fused to SOD1A4V to a large GFP fragment. This finding suggests the idea that EGFP fusion is more effective in monitoring protein aggregation, which is loosely packed, than split GFP complementation.

3.3 Aggregate Formation of SOD1A4V Variants in Transfected HEK293T Cells

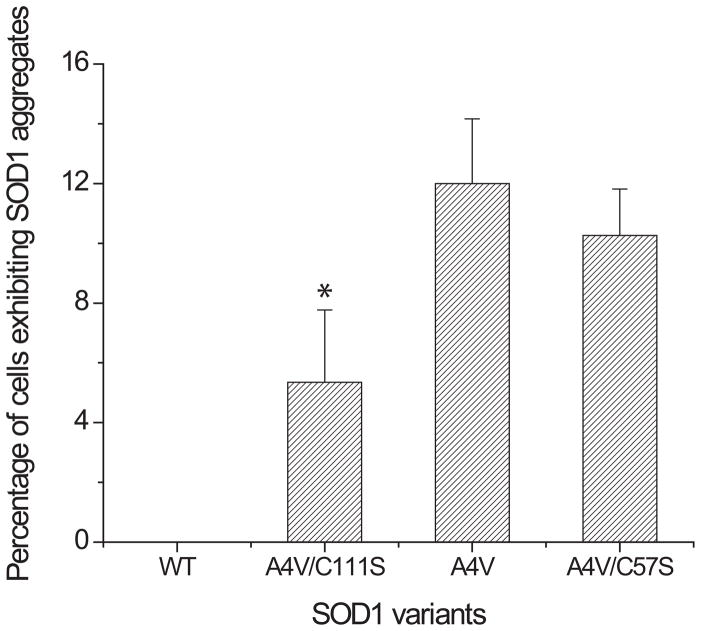

Our results indicate that transfected cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1 variants exhibited significant disparity in the mean cellular fluorescence intensity; but the disparity was not caused by differences in the transfection efficiency or expression level of the SOD1 variants. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that there are substantial differences in the structures of the SOD1 variants. We hypothesized that the disparity in fluorescence intensities of cells expressing the SOD1 variants result from differences in the extent of misfolding, aggregation, or both for the SOD1 variants. Transfected cells expressing four SOD1-EGFP variants were re-examined using fluorescence microscopy at a higher magnification (400X). Transfected cells expressing SOD1A4V exhibited visible aggregates inside cells whereas cellular fluorescence of the transfected cells expressing SOD1WT is evenly distributed in the cytosol (Figure 1B), consistent with results previously reported [49]. Similar intracellular aggregates were found in both transfected cells expressing SOD1A4V/C111S and SOD1A4V/C57S, respectively (Figure S5 in the Supplemental Information). The percentage of cells containing intracellular aggregates was determined by examining the fluorescence microscopic images of the transfected cells. Over five hundred cells for each SOD1 variant were analyzed and the results were plotted (Figure 3). Around 12% of the transfected cells expressing SOD1A4V exhibited intracellular aggregates, whereas none of the transfected cells expressing SOD1WT showed any intracellular aggregates. However, approximately 5% of the cells expressing SOD1A4V/C111S showed aggregates, consistent with the reduced aggregation of SOD1A4V/C111S compared to SOD1A4V in mammalian cells [41]. Therefore, the significant increase (P < 0.05) in the cellular fluorescence intensity of cells expressing SOD1A4V/C111S over that of SOD1A4V (Figure 2A) is attributed to the reduced aggregation of SOD1A4V/C111S compared to SOD1A4V (Figure 1B). In the case of SOD1A4V/C57S, 10% of the transfected cells exhibited intracellular aggregates but the difference from SOD1A4V is not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Therefore, the percentage of cells exhibiting SOD1-EGFP aggregates determined by fluorescence microcopy does not correlate well to the cellular fluorescence intensity. However, the enhanced misfolding propensity of SOD1A4V/C57S over SOD1A4V [41], which severely inhibits correct folding of GFP, is better attributed to a loss of fluorescence. In Figure 2A, the change in the cellular fluorescence caused by C57S mutation was greater than the change caused by C111S, which can be explained by the greater extent of structural perturbations made by aggregation and misfolding. Considering that the loss of an intra-subunit disulfide bond caused by C57S mutation generates very unstable monomeric SOD1s, structural perturbation of SOD1 caused by C57S mutation is likely greater than that of SOD1 caused by intermolecular disulfide network-mediated aggregation. In summary, mean cellular fluorescence intensity of cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1 variant is a good indicator of deviations (combined effects of misfolding and aggregation) from correctly folded structure. However, caution should be taken when correlating the cellular fluorescence intensity to only either aggregation or misfolding of SOD1 variants, because both aggregation and misfolding of SOD1 variant may not occur simultaneously.

Figure 3. The percentage of transfected HEK293T cells exhibiting SOD1 aggregates.

The number of cells exhibiting intracellular SOD1 aggregates was determined by analyzing fluorescence microscopy images of the transfected cells expressing EGFP fusion of four SOD1 variants (SOD1WT, SOD1A4VC111S, SOD1A4V, and SOD1A4V/C57S) at day two post-transfection. Values and error bars represent mean and standard deviations, respectively (n = 3). Two-sided Student’s t-tests were applied to the data (*: P < 0.05). Numerical values of the mean cellular fluorescence intensities are shown in Table S2 in Supplemental Information.

3.4 Comparison of the Cellular Fluorescence of Transfected NSC-34 and HEK293T Cells Expressing SOD1 Variants

In the transfected HEK293T cells expressing four SOD1-EGFP variants, there was good quantitative correlation between the cellular fluorescence intensity and the combined misfolding and aggregation propensities. In order to confirm that the correlation is valid in cells other than HEK293T cells, mouse neuroblastoma NSC-34 cells [50] were also examined at two days post-transfection using flow cytometric analysis similar to the transfected HEK293T cells. NSC-34 cell is a widely used cell line to study SOD1 expression in cultured cells [51–55]. Even in the transfected NSC-34 cells, the order of cellular fluorescence intensities matched well with the inverse order of misfolding/aggregation propensities of the SOD1 variants (Figure 4A). In order to determine whether there is a direct correlation between the mean fluorescence intensities of HEK293T and NSC-34 cells expressing the four SOD1-EGFP variants, the mean cellular fluorescence intensities of both cells were plotted (Figure 4B). The fluorescence ratios of SOD1 variant over SOD1WT in NSC-34 cells were similar to those in HEK293T cells. Furthermore, a linear correlation between the fluorescence intensities of both transfected cells was observed (R2 = 0.98), indicating that an inverse relationship between the cellular fluorescence intensity and the misfolding/aggregation propensity of SOD1 variants is valid in both cell lines. However, the fluorescence intensities of the transfected NSC-34 cells are about one half of that of the corresponding transfected HEK293T cells, which can be explained by weaker biosynthesis activities in slow growing NSC-34 cells. Therefore, in order to estimate extent of the deviation of a target protein from its correctly folded structure in a specific cell line, cellular fluorescence intensities should be calibrated using appropriate positive and negative control samples.

Figure 4. Comparison of the orders of fluorescence intensities of transfected HEK293T and NSC-34 cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1 variants.

(A) Fluorescence intensities of the transfected NSC-34 cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1 variants (SOD1WT, SOD1A4VC111S, SOD1A4V, and SOD1A4V/C57S) at two days post-transfection were determined by flow cytometry. Values and error bars represent mean cellular fluorescence and standard deviations, respectively (n = 3). (a.u. = arbitrary unit) Two-sided Student’s t-tests were applied to the data (*: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01). Numerical values of the mean cellular fluorescence intensities are shown in Table S1 in Supplemental Information. (B) Comparison of the cellular fluorescence of the transfected HEK293T at day two and NSC-34 cells at day three post-transfection. The cellular fluorescence of transfected HEK293T and NSC-34 cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1 variants (SOD1WT, SOD1A4VC111S, SOD1A4V, and SOD1A4V/C57S) was determined by flow cytometry. The data were fitted to a straight line (R2 = 0.98). FL(SOD1X)/FL(SOD1WT) indicates the ratio of fluorescence intensity of cells expressing a SOD1 variant (SOD1X) over the fluorescence intensity of cells expressing SOD1WT.

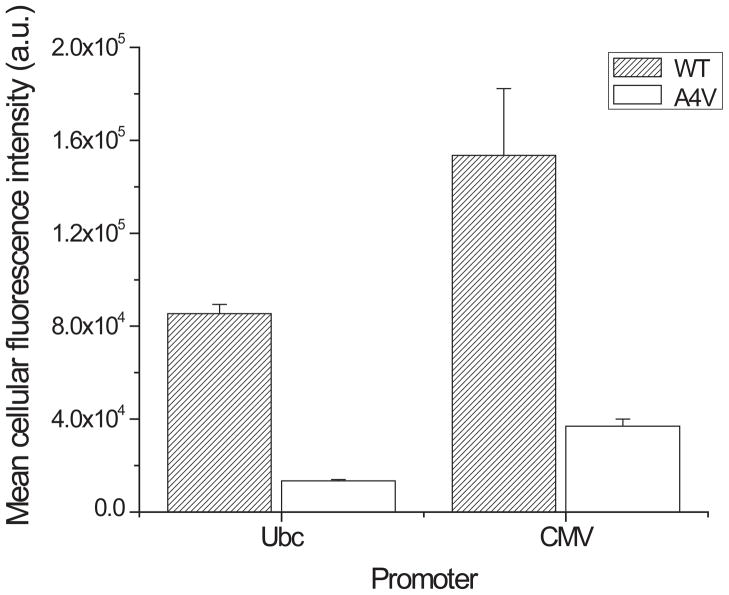

3.5 Comparison of the CMV and Ubiquitin-C Promoters

Thus far SOD1-EGFP fusion proteins were expressed under control of CMV constitutive promoter. We chose CMV promoter because it is widely used to express recombinant proteins in mammalian cells due to its relatively strong promoter activity in diverse cell lines [56]. However, we can imagine situations where a different promoter should be used. Therefore, we examined whether the choice of promoter affects the correlation between the cellular fluorescence intensity and SOD1 variant misfolding/aggregation. In order to compare promoters, we chose Ubc promoter which is also widely used in mammalian cells [56]. SOD1WT-EGFP and SOD1A4V-EGFP genes were sub-cloned into pFUG-IP lentiviral vector plasmid [48] where a target gene is under the control of ubiquitin-C (Ubc) promoter and an internal ribosome entry site/puromycin resistance gene cassette is located at 3′ of a target gene. HEK293T cells were transfected with the plasmids encoding either SOD1WT-EGFP or SOD1A4V-EGFP gene under the control of Ubc promoter. At two days post-transfection, fluorescence intensities of the transfected cells were determined by flow cytometry. The cellular fluorescence intensity of cells expressing SOD1A4V-EGFP was about six-fold lower than that of cells expressing SOD1WT-EGFP (Figure 5), indicating that Ubc promoter also allows distinction of cellular fluorescence intensities depending on their misfolding/aggregation propensity of SOD1 variants. The six-fold difference between the cellular fluorescence intensities of SOD1WT-EGFP and SOD1A4V-EGFP with Ubc promoter is greater than the two-fold difference with CMV promoter. Such a greater difference might be caused by the change of promoter from CMV to Ubc and/or the change of plasmid backbone from pEGFP-N3 to pFUG-IP. In order to investigate this, we replaced the Ubc promoter in the pFUG-IP plasmid backbone with CMV promoter. The cellular fluorescence intensity of cells transfected with the modified pFUG-IP plasmid carrying CMV-SOD1WT-EGFP cassette was around four-fold greater than that of CMV-SOD1A4V-EGFP cassette in the same plasmid backbone, which suggests that the pFUG-IP plasmid backbone plays an important role in increasing the difference between the cellular fluorescence intensities of SOD1WT-EGFP and SOD1A4V-EGFP. It is noteworthy that the pFUG-IP plasmid encodes a puromycin resistant gene as well as a target protein gene. Therefore, both puromycin resistant gene and SOD1-EGFP genes are over-expressed when pFUG-IP plasmid is used, whereas only SOD-EGFP is over-expressed when pEGFP-N3-SOD1 plasmid is used. Therefore, it is possible that chaperone proteins facilitating folding of unstable SOD1 are less available to SOD1 when pFUG-UP plasmid is used, because the chaperone proteins are also involved in the folding of co-expressed puromycin resistant protein. Furthermore, it was reported that several SOD1 mutants inhibit chaperone activities [57]. Therefore, we hypothesize that over-expression of another gene, as well as SOD1-EGFP, limits chaperone activity required for SOD1-EGFP folding. Such a shortage of chaperone activity is more detrimental to mutant SOD1 folding and leads to the greater reduction in the cellular fluorescence intensity. In order to investigate this hypothesis, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with both pEGFP-N3-SOD1A4V and pAAV-Luc (a plasmid encoding luciferase gene under the control of CMV promoter) plasmids and also observed sixfold difference between the fluorescence intensities of SOD1WT-EGFP and SOD1A4V-EGFP with co-expression of luciferase protein (Figure S6 in the Supplemental Information). Therefore, when another protein is over-expressed, as well as the EGFP fusion of a target protein, caution should be taken to use the EGFP fusion to monitor aggregation/misfolding.

Figure 5. Comparison of CMV and Ubc promoter activities for the fluorescence intensities of transfected HEK293T cells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1 variants.

Cellular fluorescence of HEK293Tcells expressing EGFP fusion of SOD1WT and SOD1A4V under the control of either CMV or Ubc promoter was determined by flow cytometry. Values and error bars represent mean cellular fluorescence and standard deviations, respectively (n = 3). (a.u. = arbitrary unit) Numerical values of the mean cellular fluorescence intensities are shown in Table S1 in Supplemental Information.

The fluorescence intensity of cells expressing SOD1WT-EGFP under the control of Ubc promoter was about 5-fold lower than that of CMV promoter (Figure 5), likely due to weaker activity of Ubc promoter than CMV promoter in HEK293T cells [56]. As expected, when the Ubc promoter in the pFUG-IP backbone was replaced with CMV promoter, the cellular fluorescence intensities of cells expressing both SOD1WT-EGFP and SOD1A4V-EGFP increased two fold (Figure 5). In summary, both CMV and Ubc promoters enable distinction of cellular fluorescence depending on misfolding/aggregation propensity of SOD1 variants.

4. Concluding remarks

Our investigation has conclusively established that EGFP fused to SOD1 variant C-terminus allows the extent of deviations to be determined from the correctly folded structure of SOD1 via cellular fluorescence measurement. The order of fluorescence intensities of transfected cells expressing four SOD1 variants correlates well to the inverse order of misfolding/aggregation propensities of the four SOD1 variants in both HEK293 and NSC-34 cells. Therefore, mean cellular fluorescence of cells expressing EGFP fusion of a target protein is a good indicator of misfolding/aggregation of the target protein. Flow cytometric monitoring of mutant SOD1 aggregation in cultured cells is a simple, but effective method that provides an array of structural information. This method could be used to screen for small molecule or protein-based drugs that inhibit mutant SOD1 aggregation. Screening of small molecule inhibitors in cultured cells is desirable to identify small molecule inhibitors of mutant SOD1 aggregation. If the small molecules identified were to inhibit mutant SOD1 aggregation, the fluorescence intensity of the cells will be near that of SOD1WT. Combined with an automatic sampler in a 96-well plate format, large small molecule inhibitor libraries can be screened with moderate to high throughput. Protein-based therapeutics that inhibit mutant SOD1 aggregation can be also identified by screening protein libraries in a high-throughput manner using fluorescence activated cell sorter. With the rapid advancements in ALS research, this assay would serve as a powerful tool in understanding the pathological mechanism and developing treatments for fALS.

Generality of GFP tagging method will easily allow extension of this method to monitor other cytosolic proteins that readily form aggregates. Aggregation of recombinant protein expressed in mammalian cells can reduce recombinant protein production yield. Therefore, the folding reporter can be used to determine residues causing protein aggregation and to identify less aggregation-prone protein variants by screening protein libraries. Furthermore, the folding reporter can be used to develop a fusion tag/protein to enhance solubility of target proteins in mammalian cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Haining Zhu for providing the pEGFP-N3-SOD1WT and pEGFP-N3-SOD1A4V plasmids. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant (R21NS069946) and a KSEA Young Investigator Grant (I.K.). This work was also supported by a NSF PAGES Scholarship and UVEF graduate Fellowship (S.G).

Abbreviations

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HEK

human embryonic kidney cell

- SOD1

human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase

- Ubc

ubiquitin-C

Footnotes

The authors declare no commercial or financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bartolini M, Andrisano V. Strategies for the Inhibition of Protein Aggregation in Human Diseases. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1018–1035. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colby DW, Cassady JP, Lin GC, Ingram VM, Wittrup KD. Stochastic kinetics of intracellular huntingtin aggregate formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nchembio792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy RM. Peptide aggregation in neurodegenerative disease. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:155–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.092801.094202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. In vitro aging of beta-amyloid protein causes peptide aggregation and neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1991;563:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91553-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S, Fernandez EJ, Good TA. Role of aggregation conditions in structure, stability, and toxicity of intermediates in the A beta fibril formation pathway. Protein Sci. 2007;16:723–732. doi: 10.1110/ps.062514807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keshet B, Yang IH, Good TA. Can Size Alone Explain Some of the Differences in Toxicity Between beta-Amyloid Oligomers and Fibrils? Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106:333–337. doi: 10.1002/bit.22691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentine JS, Hart PJ. Misfolded CuZnSOD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3617–3622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730423100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colby DW, Chu YJ, Cassady JP, Duennwald M, et al. Potent inhibition of huntingtin and cytotoxicity by a disulfide bond-free single-domain intracellular antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17616–17621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408134101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuda M, Suzuki N, Taniguchi S, Oikawa T, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of alpha-synuclein filament assembly. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2006;45:6085–6094. doi: 10.1021/bi0600749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray SS, Nowak RJ, Brown RH, Lansbury PT. Small-molecule-mediated stabilization of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked superoxide dismutase mutants against unfolding and aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3639–3644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408277102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghanta J, Shen CL, Kiessling LL, Murphy RM. A strategy for designing inhibitors of beta-amyloid toxicity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29525–29528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe TL, Strzelec A, Kiessling LL, Murphy RM. Structure-function relationships for inhibitors of beta-amyloid toxicity containing the recognition sequence KLVFF. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2001;40:7882–7889. doi: 10.1021/bi002734u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong HE, Qi W, Choi HM, Fernandez EJ, Kwon I. A Safe, Blood-Brain Barrier Permeable Triphenylmethane Dye Inhibits Amyloid-β Neurotoxicity by Generating Nontoxic Aggregates. Acs Chemical Neuroscience. 2011;2:645–657. doi: 10.1021/cn200056g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong HE, Kwon I. Xanthene Food Dye, as a Modulator of Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid-beta Peptide Aggregation and the Associated Impaired Neuronal Cell Function. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ioannou YA, Bishop DF, Desnick RJ. Overexpression of human alpha-galactosidase-A results in its intracellular aggregation, crystallization in lysosomes, and selective secretion. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1137–1150. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii S, Kase R, Okumiya T, Sakuraba H, Suzuki Y. Aggregation of the Inactive Form of Human α-Galactosidase in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:812–815. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schröder M, Schäfer R, Friedl P. Induction of protein aggregation in an early secretory compartment by elevation of expression level. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2002;78:131–140. doi: 10.1002/bit.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okumiya T, Kroos MA, Van Wet L, Takeuchi H, et al. Chemical chaperones improve transport and enhance stability of mutant alpha-glucosidases in glycogen storage disease type II. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;90:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang SJ, Yoon S, Koh G, Lee G. Effects of culture temperature and pH on flag-tagged COMP angiopoietin-1 (FCA1) production from recombinant CHO cells: FCA1 aggregation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;91:305–315. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chun WJ, Waldo GS, Johnson GVW. Split GFP complementation assay: a novel approach to quantitatively measure aggregation of tau in situ: effects of GSK3 beta activation and caspase 3 cleavage. J Neurochem. 2007;103:2529–2539. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldo GS, Standish BM, Berendzen J, Terwilliger TC. Rapid protein-folding assay using green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:691–695. doi: 10.1038/10904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim W, Hecht MH. Sequence determinants of enhanced amyloidogenicity of Alzheimer A beta 42 peptide relative to A beta 40. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35069–35076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505763200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim W, Hecht MH. Mutations enhance the aggregation propensity of the Alzheimer’s A beta peptide. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim W, Kim Y, Min J, Kim DJ, et al. A high-throughput screen for compounds that inhibit aggregation of the Alzheimer’s peptide. Acs Chemical Biology. 2006;1:461–469. doi: 10.1021/cb600135w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caine J, Sankovich S, Antony H, Waddington L, et al. Alzheimer’s Aβ fused to green fluorescent protein induces growth stress and a heat shock response. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7:1230–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li XQ, Zhao XN, Fang Y, Jiang X, et al. Generation of destabilized green fluorescent protein transcription reporter. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34970–34975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholls SB, Chu J, Abbruzzese G, Tremblay KD, Hardy JA. Mechanism of a Genetically Encoded Dark-to-Bright Reporter for Caspase Activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:24977–24986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niwa J, Yamada S, Ishigaki S, Sone J, et al. Disulfide bond mediates aggregation, toxicity, and ubiquitylation of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutant SOD1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28087–28095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto G, Kim S, Morimoto RI. Huntingtin and Mutant SOD1 Form Aggregate Structures with Distinct Molecular Properties in Human Cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4477–4485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosen DR. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide-dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral scrlerosis. Nature. 1993;364:362–362. doi: 10.1038/364362c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang FJ, Zhu HN. Intracellular conformational alterations of mutant SOD1 and the implications for fALS-associated SOD1 mutant induced motor neuron cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta-Gen Subj. 2006;1760:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banci L, Bertini I, Boca M, Girotto S, et al. SOD1 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: mutations and oligomerization. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galaleldeen A, Strange RW, Whitson LJ, Antonyuk SV, et al. Structural and biophysical properties of metal-free pathogenic SOD1 mutants A4V and G93A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;492:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valentine JS, Doucette PA, Zittin Potter S. Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:563–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rakhit R, Chakrabartty A. Structure, folding, and misfolding of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2006;1762:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auclair JR, Boggio KJ, Petsko GA, Ringe D, Agar JN. Strategies for stabilizing superoxide dismutase (SOD1), the protein destabilized in the most common form of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:21394–21399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015463107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidlin T, Kennedy BK, Daggett V. Structural Changes to Monomeric CuZn Superoxide Dismutase Caused by the Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-Associated Mutation A4V. Biophys J. 2009;97:1709–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prudencio M, Hart PJ, Borchelt DR, Andersen PM. Variation in aggregation propensities among ALS-associated variants of SOD1: correlation to human disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3217–3226. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevens JC, Chia R, Hendriks WT, Bros-Facer V, et al. Modification of Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD1) Properties by a GFP Tag – Implications for Research into Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cozzolino M, Amori I, Pesaresi MG, Ferri A, et al. Cysteine 111 affects aggregation and cytotoxicity of mutant Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:866–874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Beus MD, Chung J, Colón W. Modification of cysteine 111 in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase results in altered spectroscopic and biophysical properties. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1347–1355. doi: 10.1110/ps.03576904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujiwara N, Nakano M, Kato S, Yoshihara D, et al. Oxidative Modification to Cysteine Sulfonic Acid of Cys111 in Human Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35933–35944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watanabe S, Nagano S, Duce J, Kiaei M, et al. Increased affinity for copper mediated by cysteine 111 in forms of mutant superoxide dismutase 1 linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free Radical Biol Med. 2007;42:1534–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furukawa Y, Fu R, Deng HX, Siddique T, O’Halloran TV. Disulfide cross-linked protein represents a significant fraction of ALS-associated Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase aggregates in spinal cords of model mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7148–7153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602048103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niwa J, Yamada S, Ishigaki S, Sone J, et al. Disulfide bond mediates aggregation, toxicity, and ubiquitylation of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutant SOD1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28087–28095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graham FL, van der Eb AJ. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jang JH, Koerber JT, Kim JS, Asuri P, et al. An Evolved Adeno-associated Viral Variant Enhances Gene Delivery and Gene Targeting in Neural Stem Cells. Mol Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witan H, Kern A, Koziollek-Drechsler I, Wade R, et al. Heterodimer formation of wild-type and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-causing mutant Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase induces toxicity independent of protein aggregation. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1373–1385. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cashman NR, Durham HD, Blusztajan JK, Oda K, et al. Neuroblastoma x spinal cord (NSC) hybrid cell lines resemble developing motor neurons. Dev Dyn. 1992;194:209–221. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001940306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Babetto E, Mangolini A, Rizzardini M, Lupi M, et al. Tetracycline-regulated gene expression in the NSC-34-tTA cell line for investigation of motor neuron diseases. Mol Brain Res. 2005;140:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raimondi A, Mangolini A, Rizzardini M, Tartari S, et al. Cell culture models to investigate the selective vulnerability of motoneuronal mitochondria to familial ALS-linked G93ASOD1. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:387–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rizzardini M, Lupi M, Mangolini A, Babetto E, et al. Neurodegeneration induced by complex I inhibition in a cellular model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res Bull. 2006;69:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tartari S, D’Alessandro G, Babetto E, Rizzardini M, et al. Adaptation to G93Asuperoxide dismutase 1 in a motor neuron cell line model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. FEBS J. 2009;276:2861–2874. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kupershmidt L, Weinreb O, Amit T, Mandel S, et al. Neuroprotective and neuritogenic activities of novel multimodal iron-chelating drugs in motor-neuron-like NSC-34 cells and transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. FASEB J. 2009;23:3766–3779. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-130047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qin JY, Zhang L, Clift KL, Hulur I, et al. Systematic Comparison of Constitutive Promoters and the Doxycycline-Inducible Promoter. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tummala H, Jung C, Tiwari A, Higgins CMJ, et al. Inhibition of Chaperone Activity Is a Shared Property of Several Cu,Zn-Superoxide Dismutase Mutants That Cause Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17725–17731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.