Abstract

PPARγ is involved in expression of genes that control glucose and lipid metabolism. PPARγ is the molecular target of the thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of antidiabetic drugs. However, despite their clinical use these drugs are related to numerous adverse effects, which are related to their full activation of PPARγ transcriptional responses. PPARγ partial agonists are the focus of development efforts towards second-generation PPARγ modulators with favourable pharmacology, potent insulin sensitization without the severe full agonists’ adverse effects. In order to identify novel PPARγ partial agonist lead compounds, we developed a virtual screening protocol based on 3D-ligand shape similarity and docking. 235 compounds were prioritized for experimental screening from a 340,000 MLSMR chemical library. Seven novel potent partial agonists were confirmed in cell-based transactivation and competitive binding assays. Our results illustrate a well-designed virtual screening campaign successfully identifying novel lead compounds as potential entry points for the development of antidiabetic drugs.

Keywords: diabetes, drug design, partial agonists, PPARγ, virtual screening

Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is a nuclear receptor that functions as a ligand-dependent transcriptional regulator of multiple genes involved in adipogenesis, insulin sensitization and lipid metabolism.[1] There are two alternative splice variants of PPARγ, and PPARγ2 has been shown to be the essential master regulator of adipogenesis.[2] The thiazolidinedione (TZD) antidiabetic agents (e.g. rosiglitazone and pioglitazone[3]) are PPARγ synthetic agonists that improve insulin sensitivity largely by pleiotropic effects in adipose tissue.[4] However, despite their clinical benefit for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, use of these insulin-sensitizing agents has been associated with adverse effects including weight gain, increased adipogenesis, renal fluid retention, plasma volume expansion and edema that can cause congestive heart failure.[5] Recently, new classes of PPARγ ligands, the so called selective PPARγ modulators (SPPARγMs), have been developed. These compounds respond as partial agonists in a GAL-4 luciferase assay and are assumed to display a different binding mode in the PPARγ subunit compared to the full agonist glitazones.[6]

Furthermore, it was recently shown that phosphorylation of PPARγ at Ser273 leads to dysregulation of a large number of genes whose expression is altered in obesity.[7] This phosphorylation is mediated by kinase Cdk5, which is activated in adipose tissues by obesity induced in mice by high-fat feeding. This study has shown that phosphorylation of PPARγ by Cdk5 is blocked by anti-diabetic PPARγ ligands, such as rosiglitazone[3] and MRL24.[8]

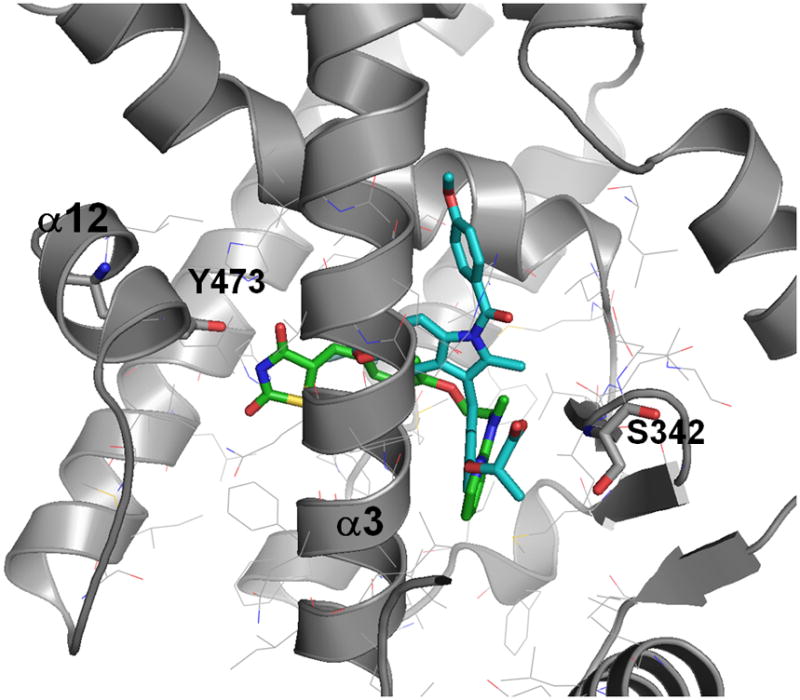

PPARγ activates transcription when ligand binding induces alterations in receptor conformational stability, which leads to displacement of corepressor proteins and the recruitment of coactivator proteins.[9] PPARγ ligands bind in a relatively large cavity within the C-terminal ligand binding domain (LBD), which contains a ligand-regulated activation function (AF2) structural element that consists of helix 3–4 loop and helix 12. The transcription mechanism involves both a global stabilization of the LBD as well as stabilization of the C-terminal helix 12 of AF2.[10] However, a number of partial agonists were shown to differentially stabilize various regions of the LBD.[11] They have a distinct physical interaction with the receptor, for the majority resulting in diminished conformational stability of the AF2 surface of the receptor compared to full agonists. X-ray structures of the PPARγ LBD complexed with full agonist rosiglitazone indicate hydrogen-bonding between rosiglitazone and the side chain of Tyr473 in helix 12.[12] The binding mode of rosiglitazone complexed with human LBD of PPARγ (pdb code 2prg) is shown in Figure 1. In contrast, the majority of SPPARγMs do not bind within hydrogen-bonding distance of Tyr473[13] suggesting that Tyr473 is a critical site of interaction between the PPARγ LBD and full agonists, but not for partial agonists. To illustrate this difference, Figure 1 also shows the binding mode of the partial agonist MRL24.

Figure 1.

Binding pose of the full agonist rosiglitazone (in green/in black) and the partial agonists MRL24 (in blue/in white) in the PPARγ LBD.

Selective recruitment of transcriptional coactivators by partial agonist has also been demonstrated. A different PPARγ binding mode leading to a distinct coactivator recruitment profile may explain the change in gene expression patterns compared to those of full agonists (glitazones).[14] Interestingly, partial agonists are reported to show fewer side effects in preclinical models of diabetes while retaining similar pharmacodynamic efficacy to the glitazones.[14a, 15]

Due to their improved pharmacodynamics, there is a substantial interest and need to develop insulin-sensitizing PPARγ modulators with minimal classical activation of PPARγ and reduced side effects, while maintaining robust anti-diabetic efficacy. Here we employ a virtual screening approach and we identify novel and diverse PPARγ partial agonists with nanomolar activity.

Results and Discussion

Virtual Screening Workflow

To identify novel PPARγ partial agonists we developed a virtual screening workflow. Our approach is based on the hypothesis that majority of the partial agonists - in contrast to full agonists - primarily bind in one region of the large PPARγ binding pocket away from helix 12, and that they have a characteristic binding pattern that is different from full agonists. Although partial agonists that bind in the region of helix 12 and activating PPARγ by an alternative mechanism have been reported,[16] our goal here is to identify partial agonists that would primarily interact with Ser342 (Figure 1) based on the recent findings of PPARγ phosphorylation near this region of the pocket.[7] This binding mode hypothesis and our aim to identify structurally novel lead compounds led us to focus our virtual screening approach towards volume and shape requirements of partial agonists, rather than structural (2D) similarity to known PPARγ partial agonists.

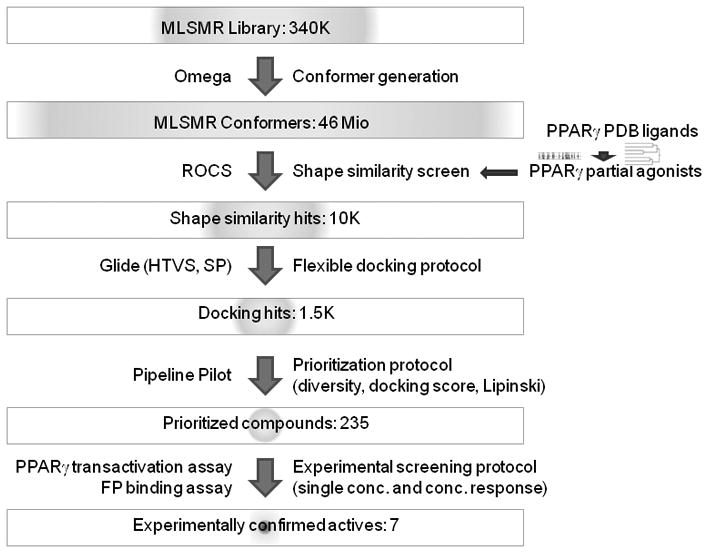

A good virtual screening protocol needs to be fast and accurate making it practical to scan through large compound libraries (hundreds of thousands to millions) in order to prioritize a small number of compounds that can be experimentally tested (typically tens to hundreds) and which include at least a few actives. Our virtual screening protocol is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Virtual screening workflow.

We combined fast 3D ligand shape-based screening[17] with two stages of structure-based flexible docking[18] of increasing accuracy followed by a prioritization protocol that incorporated the docking scores, chemical diversity and drug-like properties of the compounds. Shape-based virtual screening is a fast and effective method and in the case of PPARγ, which has a large binding pocket, can be expected to effectively prioritize possible partial agonists (for example in contrast to docking that would identify compounds that fit anywhere in the pocket). We assume novel PPARγ partial agonists would bind in the same region as known ones, such as MRL24[8] (1, PDB ligand code 241 - PDB code 2q5p - in Figure 4). They should therefore have a similar 3D conformation (shape) and size.

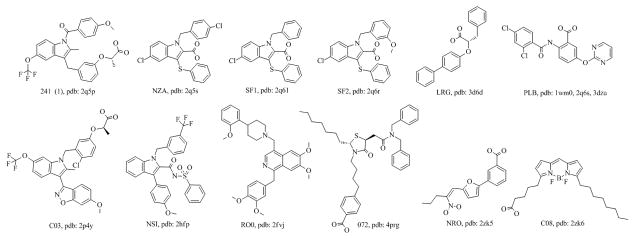

Figure 4.

2D structures of the reference PPARγ partial agonist co-crystal ligands.

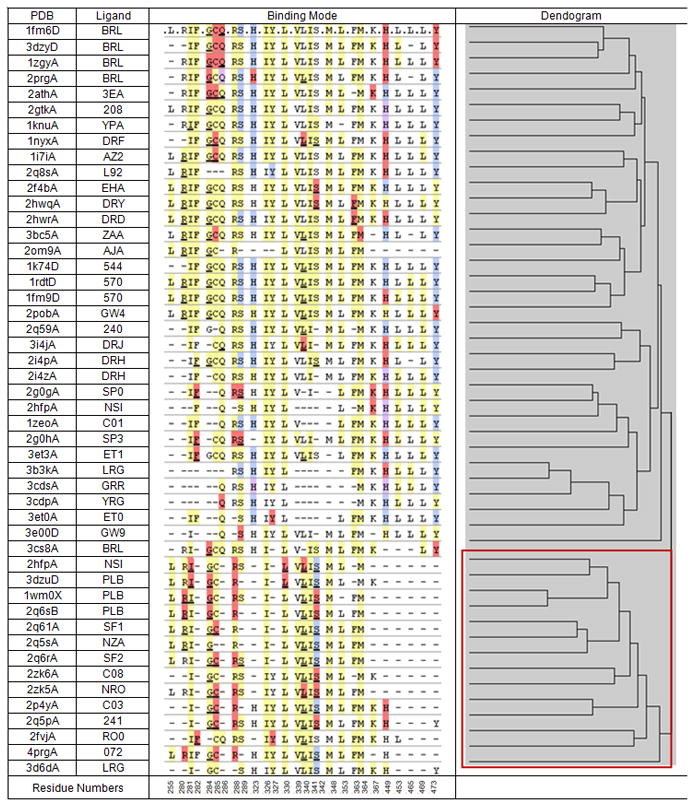

Identification of partial agonist reference compounds and 3D shape-based screening of the MLSMR library

We explored the Protein Data Bank (PDB)[19] for known PPARγ partial agonists[11] based on the premise that their pharmacology is related to their distinct binding mode. Although over 60 small molecule PPARγ co-crystal structures were available in the PDB, their activity in most cases had not been clearly defined as partial or full agonists - the majority can be expected to be full agonists based on the interaction with Tyr473. To identify suitable reference partial agonist co-crystal ligands we prepared all PPARγ co-crystal complexes and clustered the ligands by their binding modes (see methods). Results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Binding modes of co-crystallized PPARγ modulators, binding mode similarity dendrogram and the identified partial agonist-like ligand cluster (shown in the lower right corner box). Residues coloured in yellow have non-polar interactions, red are polar interactions, blue are hydrogen-bond interactions and purple are polar/hydrogen-bond interactions.

Figure 3 indicates two major groups of PPARγ co-crystal binding interactions. The cluster shown on top consists of ligands that interact with Tyr473 (terminal Y in their binding mode fingerprints) with almost no exception. The majority of these Tyr473 interactions are either hydrogen bonds or polar. The lower cluster (box in the Figure 3 dendrogram) includes five reported partial agonists and seven additional ligands.

None of these ligands have an explicit interaction with Tyr473. We therefore anticipate that they all behaved like partial agonists and we used them as reference compounds for the shape similarity search. Their structures, PDB ligand annotations,[20] and the corresponding PDB codes are shown in Figure 4.

Previously, three PPARγ HTS campaigns were conducted, screening 196,180 compounds from the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) to identify compounds that selectively recruited the p160 family of nuclear receptor coactivators SRC1, SRC2, or SRC3 to PPARγ. These assays were TR-FRET based assays using purified PPARγ LBD and the receptor interaction domains of the three p160 coactivators. Unfortunately, these campaigns had only identified compounds with EC50 > 10 μM, which were not considered tractable leads (PubChem AIDs 631,[21] 1032,[22] 731[23]). We therefore focused our virtual screening efforts on the full MLSMR library. We hypothesized that PPARγ partial agonists have specific shape and volume requirements and that shape-based similarity searching against a number of known PPARγ partial agonists would therefore be effective as the initial step in the virtual screening protocol.

The MLSMR library of 341,139 substances was pre-processed and a conformer library of about 46 million conformers was generated with OpenEye Omega2 (see methods). Using OpenEye ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures), the 12 reference partial agonists in their co-crystal conformation were overlaid with the MLSMR conformer library and their shape similarity was scored (see methods).

Flexible docking of the most shape-similar compounds

For each of 12 reference compounds, the MLSMR compounds were ranked by their calculated shape similarity. The top 1,000 MLSMR compounds for each reference ligand, a total of 9,467 unique compounds, were selected to further prioritize the best binding PPARγ partial agonists by docking. Docking is an effective method to prioritize ligands with favourable interactions to a receptor. Compounds were prepared to generate tautomers and ionization states and a 2-stage flexible docking protocol consisting of initial high throughput docking followed by a more accurate scoring method was performed. To further increase the likelihood of identifying partial agonists, we introduced a specific hydrogen bond constraint to the backbone NH of PPARγ Ser342. Ser342 is located away from helix 12, which is on the opposite end of the large PPARγ binding site where full agonists typically bind (Figure 1). Because the compounds to be docked have been pre-selected based on shape similarity to known partial agonists and are therefore similar in size, they are less likely to reach into the full agonist binding region if they are constraint by a hydrogen bond to Ser342, which therefore can potentially reduce the identification of (undesired) full agonists. Moreover, interaction with Ser342 is preserved through most of the partial agonist crystal structures (central S hydrogen bond/polar interaction in the binding mode fingerprints in Figure 3) and may be interpreted as a characteristic PPARγ partial agonist interaction.

After (constraint) high throughput docking 4,635 poses corresponding to 2,197 unique MLSMR compounds were selected based on docking scores. These were re-docked using a more accurate method from which the best scoring 1,500 unique compounds were kept (see methods).

Structural Diversity of Virtual Screening Hits

Compounds to be purchased for experimental testing were selected using the docking scores in combination with their chemical structure diversity[24] and Lipinski properties[25] (see methods). The compounds after docking were clustered using different descriptors[26] and for each method the top scoring compounds were selected from each cluster such that the desired number of compounds was obtained. After Lipinski filtering compounds that were unanimously identified by all clustering methods were kept and additional compounds with the best docking scores were added to give a total of 250 compounds to be acquired. 235 were received and tested in the cell-based transactivation PPARγ assay.

Biological Screening Results

Cell-based luciferase reporter assays were performed to determine the ability of the 235 virtual screening hits to potentiate PPARγ dependent transactivation of a luciferase reporter gene driven by three copies of a PPARγ response element (3xPPRE) as its promoter. Initial screens were conducted in two replicate experiments at single-concentrations of test compounds using 1 as a partial agonist control, (2S)-2-[2-({1-[(4-methoxyphenyl)carbonyl]-2-methyl-5-(trifluoromethoxy)-1H-indol-3-yl}methyl)phenoxy]propanoic acid[8] (2, known as MRL20, PDB ligand code 240[11]) as the full agonist control, and DMSO being the negative control. Compounds were categorized as active or inactive based on the ability to activate the PPARγ dependent transactivation of the luciferase reporter compared to the controls as measured by luminescence. Screening results were analyzed and grouped in order to prioritize compounds for concentration-response testing. Any of the 235 compounds that displayed activity in the PPARγ dependent transactivation of the PPRE in either replicate experiment with a signal greater than or equal to 85% of activation of 1 were considered candidates for further dose-response experiments using the cell-based reporter assays (assay results shown in Table S1 in the supporting material). Using this criteria, 62 compounds in total were retested in dose-response and both percent activation and EC50 values were calculated.

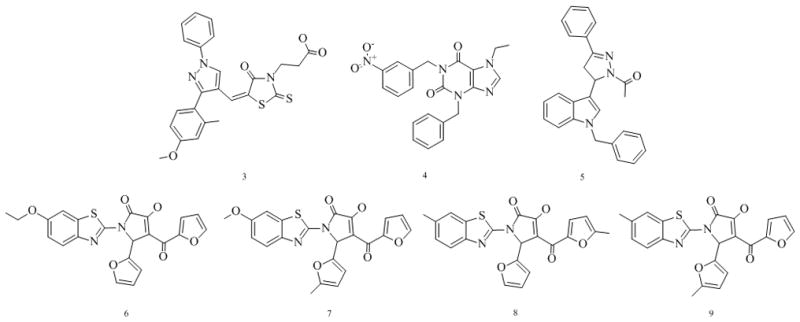

Among the 62 compounds numerous compounds were partial activators in the cell based transactivation assay. Interestingly, no compound exhibited full agonist behaviour. The confirmed (partial agonist) actives were then tested in a dose-response fluorescence polarization (FP) competition assay to determine their ability to displace a fluorescent PPARγ probe (see methods). Through this assay seven partial agonists were identified that competitively displaced the PPARγ ligand with IC50 values comparable to those achieved in the cell-based reporter assays indicating that the partial agonist phenotype observed by these compounds was the result of direct binding to the PPARγ LBD and not an alternative mechanism. The structures are shown in Figure 5 and their activities in both assays as well as the virtual screening scores are summarized in Table 1. Table 1 also includes the commercial source of the 7 MLSMR compounds.

Figure 5.

Confirmed PPARγ partial agonists.

Table 1.

Activity of confirmed PPARγ partial agonists in the cell-based transactivation and the fluorescence polarization binding assays, maximal efficacy compared to the reference full agonists, top docking score, best shape similarity score, and vendor information.

| Partial Agonist | Cell-based EC50 | FP Assay IC50 | Maximal efficacy | Glide SP Score | ROCS Score | Compound Vendor | Vendor Catalog ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 283 nM | 152 nM | 44.41% | −8.76 | 0.62 | ChemBridge | 7002925 |

| 4 | 181 nM | 173 nM | 64.11% | −9.34 | 0.72 | Enamine | T5349695 |

| 5 | 1.2 μM | 2 μM | 44.71% | −8.70 | 0.61 | InterBioScreen | STOCK2S-90936 |

| 6 | 1.2 μM | 3 μM | 37.04% | −9.12 | 0.60 | Asinex Ltd. | BAS 05885975 |

| 7 | 5 μM | 5 μM | 41.14% | −9.10 | 0.73 | Asinex Ltd. | BAS 05885563 |

| 8 | 18 μM | 22 μM | 45.76% | −9.10 | 0.67 | Asinex Ltd. | BAS 05887308 |

| 9 | 15 μM | 30 μM | 56.83% | −8.92 | 0.75 | Asinex Ltd. | BAS 05887283 |

Novelty of PPARγ partial agonists identified by virtual screening

Remarkably, among the identified partial agonists two show submicromolar activity in both assays. We identified several novel scaffolds that combine some elements of known PPARγ agonist substructures. Compound 3 contains pyrazole and thiazolidine moieties, compound 5 pyrazole and indole moieties, while compounds 6, 7, 8, and 9 present novel benzothiazole-based partial agonists bearing pyrrole and furan moieties. Compound 4 is a novel purine based partial agonist. Compounds 4 and 5 are not acidic in contrast to most known PPARγ modulators. We are currently in the process of medicinal chemistry-driven optimization of these lead compounds. We are also applying the virtual screening protocol to larger compound libraries in order to identify additional lead series.

To quantify the novelty of these compounds we compared them to the reference partial agonists. The highest Tanimoto similarity based on ECFP 4 fingerprints was 0.224 for compound 5 (similarity values for all partial agonists are given in Table S2 in the supporting material). We also compared them to previously published PPARγ modulators, which we retrieved from ChEMBL[27] (accessed on May 13, 2010). For each of the confirmed partial agonist the Tanimoto similarity to all ChEMBL PPARγ modulators was calculated. The highest Tanimoto similarity coefficient based on ECFP 4 fingerprints was 0.301 for partial agonist 6. For the other partial agonists the highest Tanimoto similarities were slightly lower ranging from 0.281 to 0.294.

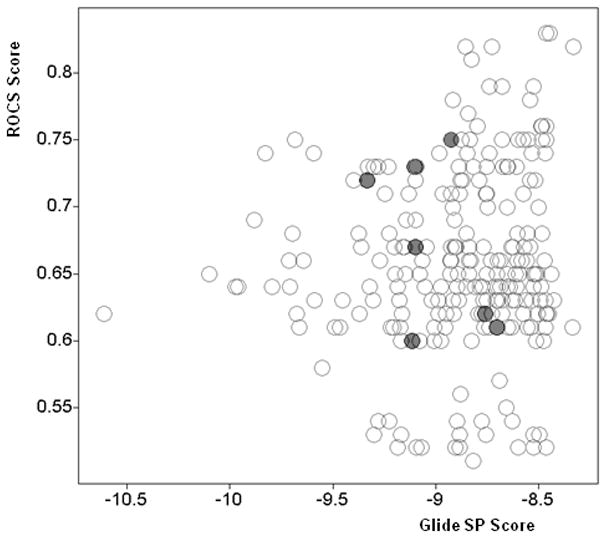

It is also worth noting that the confirmed partial agonists were not the top ranked compounds by either individual virtual screening score, but rather represent a balance of good scores by both methods (ligand shape similarity and docking). This is illustrated in the Figure 6, scatter plot of docking scores vs. ROCS score for the 235 compounds prioritized for experimental screening. For comparison, the corresponding docking scores of the 12 reference partial agonists range from −10.82 for NSI to −6.55 for NRO.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot of Glide SP docking scores and maximal shape similarity ROCS scores for 235 compounds selected for experimental screening (confirmed partial agonists marked with red/filled circles).

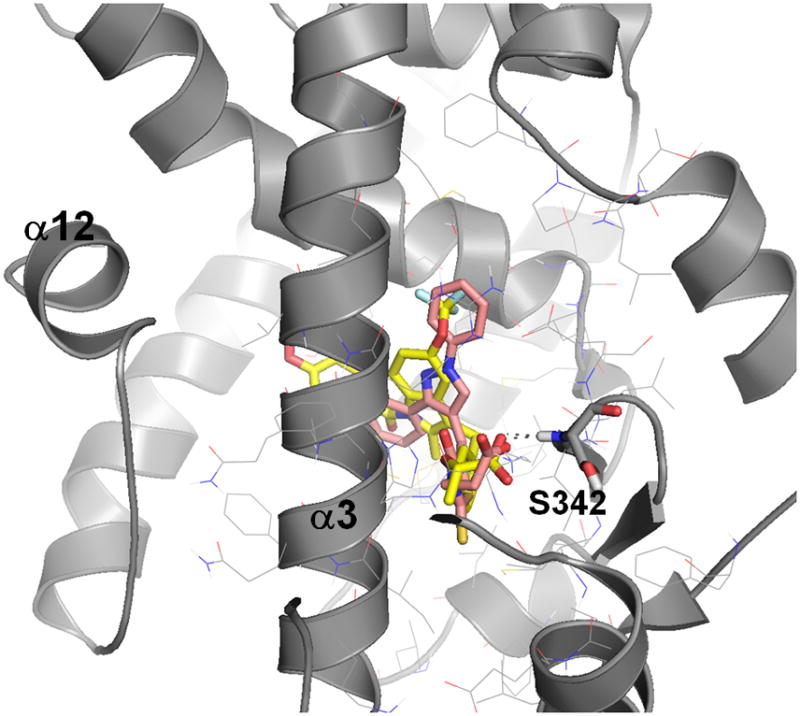

Figure 7 shows the docking pose of the most active identified novel partial agonist 3 overlaid to the co-crystal conformation of 1 illustrating both similar shape and size and similar binding mode. This supports the hypothesis that partial agonist pharmacology is mediated by their distinct binding mode, which was the assumption underlying our virtual screening strategy.

Figure 7.

Docked binding mode of novel identified partial agonist 3 (in copper/in dark gray) compared to the co-crystal conformation of 1 (in yellow/in white).

Estimated virtual screening enrichment and model applicability

235 compounds prioritized by our virtual screening protocol were experimentally tested and seven compounds were confirmed as potent partial agonists. This corresponds to 3% of confirmed actives. Hit rates of previous high-throughput screening campaigns (available in PubChem) were 0.04% (196,256 tested; 85 confirmed hits), 0.05% (196,255 tested; 93 confirmed hits) and 0.009% (196,256 tested; 17 confirmed hits), for the PPARγ SRC1, SRC2, and SRC3 co-activator recruitment assays respectively. However, no potent partial agonists were identified in these HTS campaigns. Therefore, we can estimate the enrichment of the virtual screening protocol of at least 60 to 300 fold over the corresponding HTS campaigns. This is in a real (prospective) discovery program, not a retrospective study. Notably, our method identified two nanomolar partial agonists.

Conclusion

To identify novel PPARγ partial agonists, we developed a virtual screening protocol combining ligand 3D shape-based screening and structure-based docking. Our approach was based on the hypothesis that the desirable pharmacology of partial agonists is related to their distinctive binding mode, which is determined by ligand shape and volume and the ability to bind to Ser342. We used ROCS shape based overlay as a fast method to identify ligands of desirable size and conformation to fit into the region where partial agonists typically bind. This was in particular important because the PPARγ LBD binding pocket is large and we wanted to avoid large ligands that bind beyond helix 3 and in particular ones that interact with helix 12 (Figures 1 and 7). After shape-based screening the docking protocol identified those compounds that best fit into the partial agonist region of the LBD pocket (while avoiding any interaction with Tyr473) and - importantly - those compounds that can interact with the backbone NH of Ser342. The best scoring compounds were then structurally analyzed and filtered by Lipinski criteria to select a set of diverse high scoring compounds to be purchased and biologically tested. Seven novel potent partial agonists were confirmed by concentration-response in both the cell-based transactivation and the FP binding assays.

The confirmed partial agonist ligands balanced good ROCS (shape similarity) and Glide SP (docking) scores, but were not the best scoring compounds by either individual method (Table 1 and Figure 6). This suggests the combination of the two (complementary) methods can achieve better results than either individual method alone. The screening hit rate was quite high (about 3%) compared to previous PPARγ HTS campaigns indicating very high enrichment of the virtual screening protocol. All confirmed compounds are partial agonists (no full agonists were confirmed). This is consistent with our premise that partial agonists have a distinct binding mode compared to full agonists and that it is determined by ligand shape and size and the ability to interact with Ser342. Our virtual screening protocol therefore can selectively identify partial and not full agonists and it should be applicable to other compound libraries for the identification of additional partial agonists. The identified partial agonists are structurally dissimilar from known PPARγ modulators (the maximum Tanimoto similarity coefficient based on ECFP 4 fingerprints is 0.30).

In summary our virtual screening protocol identified novel potent PPARγ partial agonists as potential new lead structures for the development of antidiabetic drugs.

Experimental Section

Screening Compounds

Chemical structures of the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) Library were downloaded from PubChem as an MDL SD-file on March 2, 2009 (341,139 substances). They were filtered using Accelrys Pipeline Pilot components in order to remove compounds with less common elements (only H, C, N, O, P, S, F, Cl, Br, or I atoms allowed) and only the largest fragment of each substance was kept leaving 341,054 molecules for further analysis. PubChem chemical structures undergo a structure verification and standardization procedure that also includes tautomer canonicalization implemented using OEChem (OpenEye). We therefore did not perform any additional structure canonicalization steps.

Reference Partial Agonists

Using Eidogen-Sertanty’s Target Informatics Platform (TIP™)[28] and Eidogen Visualization Environment (EVE)[29] -an integrated environment for the comparative analysis of biological and chemical structures - we identified and collected a total of 63 PPARγ ligand co-crystal structures as of March 9, 2009. In cases of multiple pdb chains with the same co-crystal ligand we kept the ligand conformation corresponding to the lowest-labeled PPARγ chain. Trivial ligands (such as fatty acids, glycerol, small ions, etc) were also identified and removed. Five of the PPARγ co-crystal ligands had been reported as partial agonists.[11] Their PDB ligand codes are 241 (pdb entry 2q5p, 1), NZA (pdb entry 2q5s), SF1 (pdb entry 2q61), SF2 (pdb entry 2q6r), and PLB (pdb entry 2q6s). To identify additional likely PPARγ co-crystallized partial agonists we characterized and clustered the binding modes of the above collected non-redundant small molecule PPARγ co-crystal ligands using EVE. The binding modes and clustering results are shown in Figure 3.

The cluster corresponding to the five known partial agonists (box in the dendrogram in Figure 3) included additional 7 ligands providing a total of 12 unique co-crystallized ligands with partial agonist-like binding modes. The co-crystal conformations of these 12 ligands were used as reference for shape comparison with the MLSMR library. The reference structures and their PDB codes are shown in Figure 4.

Conformer Generation

A conformer database of the MLSMR library compounds was generated using OpenEye Omega2[30] with the default settings resulting in approximately 46 million conformers. The reference compounds’ conformations were extracted from their PDB co-crystal structures.

Shape Similarity

Shape-based virtual screening of the MLSMR conformer library was performed using OpenEye ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures).[31] ROCS provides a measure of molecular shape similarity by maximizing the shape overlap between two structures. The overlays can be performed very rapidly based on a description of the molecules as atom-centered Gaussian functions.[17] ROCS quantifies shape similarity as a score between 0 (no overlap) and 1.0 (identical shape). We applied the default settings of ROCS comparing the entire MLSMR conformer library to the co-crystal conformation of each of the 12 partial agonists. MLSMR compounds were ranked by shape similarity for each reference ligand and 1,000 most shape-similar MLSMR compounds were kept per reference ligand resulting in 9,467 unique hit molecules.

Protein Preparation

The PPARγ x-ray structure 2hfp was used for docking.[32] This structure was selected, because it is complete (no missing loops or side chains) and well resolved (2 Å). The structure was prepared using the protein preparation facility in Maestro (Schrödinger LLC)[33] including hydrogen-bond optimization and constraint (Impref) minimization.

Ligand Preparation

9,467 MLSMR compounds identified above by ROCS shape similarity to the reference partial agonist co-crystal ligands were prepared for docking using LigPrep (Schrödinger LLC).[34] Tautomers and ionization states at pH 7 ± 0.2 were generated and their 3D structures minimized using the OPLS-AA force field[35] giving 15,426 structure representations.

Ligand Docking Protocol

All docking runs were carried out using Glide (Schrödinger LLC).[36] Glide performs flexible docking using a stochastic search algorithm identifying favourable protein-ligand poses based on a model energy function that combines empirical and force-field-based terms.[18] Here we performed docking to PPARγ with a specific hydrogen bond constraint to the backbone hydrogen of Ser342.

The following docking protocol was performed: All compounds identified by shape similarity were docked (after ligand preparation) using the high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) method. Poses with a docking score of less than −6.5 (4,635 poses corresponding to 2,197 unique MLSMR library structures) were kept and re-docked using the standard precision (SP) method. 1,500 unique structures with the best SP scores were exported as MDL SD-file for further analysis (including diversity) and prioritization for purchase and experimental testing.

Compound Prioritization for Purchase and Testing

The following procedure was applied to select a diverse set of compounds with the best docking scores: The 1,500 MLSMR compounds selected from the SP docking run above were independently clustered four times using a maximum dissimilarity method (Tanimoto distance[24]) implemented in Accelrys Pipeline Pilot[37] in combination with four different fingerprints: ECFP 6, ECFP 4, FCFP 6, and FCFP 4, respectively.[26] For each fingerprint method the compounds in each cluster were sorted by the docking score and the same fraction of best scoring compounds was selected from each cluster in such a way that 250 compounds are selected overall. In this way four sets of 250 compounds were generated. As expected the different clustering runs produced overlapping cluster memberships. 376 unique compounds emerged from the selection among the different clustering methods and 142 compounds appeared in all four sets. All compounds were further filtered by Lipinski’s rule of five[25] leaving 128 compounds that appeared in all four clustering methods. Additional compounds were prioritized by their docking scores and added to give a total of 250. These compounds were ordered for biological screening. 235 were received and tested in the cell-based transactivation PPARγ assay. All compounds that profiled as partial or full agonists in the primary screen were tested in the dose-response transactivation assay. The cutoff for the activation was 85% or greater of the control partial agonist. Active compounds with PPARγ activation below 65% of the reference full agonist were considered partial agonists. Actives that confirmed in dose-response screening were then also tested in the fluorescence polarization PPARγ assay.

Compounds

All compounds in Table 1 are commercially available and they were ordered through the MLSMR. Purities were determined by ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) or multiplexed electrospray (MUX) liquid chromatography coupled to ultraviolet (214 nm) spectrometry (LC/UV214) or evaporative light scattering (LC/ELS) detection. The samples were also tested through high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS). Compound 3 was obtained from ChemBridge, vendor catalog ID: 7002925 (SID: 47196723, MLSMR ID: MLS001163538, CAS registration number: 957333-01-6); purity: 100% (LC/UV214 MUX2); HRMS m/z calculated for C24H21N3O4S2 [M + H]+: 480.1046; found: 480.1049. Compound 4 was obtained from Enamine, vendor catalog ID: T5349695 (SID: 49675823, MLSMR ID: MLS001174298, CAS registration number: 852663-89-9); purity: 100% (LC/ELS MUX2); HRMS m/z calculated for C21H19N5O4 [M + H]+: 406.1510; found: 406.1512. Compound 5 was obtained from InterBioScreen, vendor catalog ID: STOCK2S-90936 (SID: 17512233, MLSMR ID: MLS000588878, CAS registration number: 488119-34-2); purity: 100% (LC/ELS MUX2); HRMS m/z calculated for C26H23N3O [M + H]+: 394.1914; found: 394.1917. Compound 6 was obtained from Asinex Ltd., vendor catalog ID: BAS 05885975 (SID: 56422549, MLSMR ID: MLS001291209, CAS registration number: 607342-76-7); purity: 100% (LC/ELS UPLC2); HRMS m/z calculated for C22H16N2O6S [M + H]+: 437.0802; found: 437.0794. Compound 7 was obtained from Asinex Ltd., vendor catalog ID: BAS 05885563 (SID: 56422548, MLSMR ID: MLS001291208, CAS registration number: 607339-74-2); purity: 100% (LC/ELS UPLC2); HRMS m/z calculated for C22H16N2O6S [M + H]+: 437.0802; found: 437.0804. Compound 8 was obtained from Asinex Ltd., vendor catalog ID: BAS 05887308 (SID: 56423783, MLSMR ID: MLS001291212, CAS registration number: 608115-17-9); purity: 100% (LC/ELS UPLC2); HRMS m/z calculated for C22H16N2O5S [M + H]+: 421.0853; found: 421.0855. Compound 9 was obtained from Asinex Ltd., vendor catalog ID: BAS 05887283 (SID: 49727557, MLSMR ID: MLS001221390, CAS registration number: 1135293-32-1); purity: 100% (LC/ELS UPLC2); HRMS m/z calculated for C22H16N2O5S [M + H]+: 421.0853; found: 421.0855.

Visualization

We used PyMOL[38] to visualize protein structure-ligand complexes.

Transactivation PPARγ Assay

Cos-1 cells were trypsinized and reverse transfected in bulk with 3 μg of total DNA consisting of 1.5 μg of 3xPPRE luciferase reporter (generously provided by Bruce Spiegelman[39]) and 1.5 μg of full-length PPARγ in a pSport6 vector. The transfection was performed using FuGene6 (Roche) at a lipid to DNA ratio of 3:1. Following 24 hour transfection in growth media (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Media (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS), cells were trypsinized and replated into 384 well plates (Perkin Elmer) at a density of 10,000 cells/well and incubated for 4 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity. For single dose compound screening, 10 nL of compound was added to duplicate sample plates containing transfected cells using a Beckman-Coulter Biomek FX Robot with 10 nL pintool. For dose-response experiments, compounds were added in triplicate to wells of transfected cells following a ten-point serial dilution in the range 5 μM – 200 pM. 1 and 2 were used as positive controls for partial and full PPARγ agonists respectively and DMSO only treatment was used as the negative control. Following compound addition, transfected cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity. Luciferase levels were assayed by one-step addition of 30 μL BriteLite Plus (Perkin Elmer) and read using an Envision multi-label plate reader (Perkin Elmer). Data was analyzed and reporter activity was determined for every test compound as a fold change over activity following DMSO only treatment. EC50 values were determined using Prism Software (GraphPad).

Fluorescense Polarization Assay

For PPARγ binding assays, the PolarScreen PPAR Competitor binding assay was employed. The assay was performed per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, assays were performed in 384 well black plates (Corning) with 40 μL total assay volume. For each sample, 20 ng of recombinant PPARγ LBD was combined with 5 nM Fluoromone Green ligand and mixed with equal volume of assay screening buffer containing either DMSO or test compound and incubated at 25°C for 2 hours. Rosiglitazone[3] was used as a positive control for competitive binding in the assay. Following compound incubation, fluorescence polarization was determined using a Spectramax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices) with the fluorescence polarization analysis software utilizing standard fluorescence polarization wavelengths of 485 nm excitation and 535 nm emission. Compounds were initially screened in triplicate at single concentrations of 10 μM and those that demonstrated competitive binding towards PPARγ were then re-assayed in ten point dose-response experiments using concentrations in the range of 10 μM to 300 pM. Data was analyzed and IC50 values determined for each compound using Prism software (GraphPad).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grant U54-MH084512. We thank OpenEye for providing us licenses for their software. The authors acknowledge resources by the Center for Computational Science at the University of Miami. We also thank Pierre Baillargeon and Michael Chalmers from the Scripps Florida Department of Molecular Therapeutics for ordering compounds and HRMS, respectively.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemmedchem.org or from the author.

References

- 1.a) Berger J, Wagner JA. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4:163–174. doi: 10.1089/15209150260007381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chawla A, Repa JJ, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Science. 2001;294:1866–1870. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspe E, Schoonjans K, Lefebvre AM, Saladin R, Najib J, Laville M, Fruchart JC, Deeb S, Vidal-Puig A, Flier J, Briggs MR, Staels B, Vidal H, Auwerx J. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18779–18789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greene DA. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 1999;8:1709–1719. doi: 10.1517/13543784.8.10.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Pearson SL, Cawthorne MA, Clapham JC, Dunmore SJ, Holmes SD, Moore GB, Smith SA, Tadayyon M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:752–757. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Day C. Diabet Med. 1999;16:179–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Berger JP, Akiyama TE, Meinke PT. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nissen SE, Wolski K. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger J, Leibowitz MD, Doebber TW, Elbrecht A, Zhang B, Zhou G, Biswas C, Cullinan CA, Hayes NS, Li Y, Tanen M, Ventre J, Wu MS, Berger GD, Mosley R, Marquis R, Santini C, Sahoo SP, Tolman RL, Smith RG, Moller DE. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6718–6725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JH, Banks AS, Estall JL, Kajimura S, Bostrom P, Laznik D, Ruas JL, Chalmers MJ, Kamenecka TM, Bluher M, Griffin PR, Spiegelman BM. Nature. 2010;466:451–456. doi: 10.1038/nature09291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acton JJ, 3rd, Black RM, Jones AB, Moller DE, Colwell L, Doebber TW, Macnaul KL, Berger J, Wood HB. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagy L, Schwabe JW. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Johnson BA, Wilson EM, Li Y, Moller DE, Smith RG, Zhou G. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:187–194. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kallenberger BC, Love JD, Chatterjee VK, Schwabe JW. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:136–140. doi: 10.1038/nsb892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruning JB, Chalmers MJ, Prasad S, Busby SA, Kamenecka TM, He Y, Nettles KW, Griffin PR. Structure. 2007;15:1258–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolte RT, Wisely GB, Westin S, Cobb JE, Lambert MH, Kurokawa R, Rosenfeld MG, Willson TM, Glass CK, Milburn MV. Nature. 1998;395:137–143. doi: 10.1038/25931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Oberfield JL, Collins JL, Holmes CP, Goreham DM, Cooper JP, Cobb JE, Lenhard JM, Hull-Ryde EA, Mohr CP, Blanchard SG, Parks DJ, Moore LB, Lehmann JM, Plunket K, Miller AB, Milburn MV, Kliewer SA, Willson TM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6102–6106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Burgermeister E, Schnoebelen A, Flament A, Benz J, Stihle M, Gsell B, Rufer A, Ruf A, Kuhn B, Marki HP, Mizrahi J, Sebokova E, Niesor E, Meyer M. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:809–830. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Berger JP, Petro AE, Macnaul KL, Kelly LJ, Zhang BB, Richards K, Elbrecht A, Johnson BA, Zhou G, Doebber TW, Biswas C, Parikh M, Sharma N, Tanen MR, Thompson GM, Ventre J, Adams AD, Mosley R, Surwit RS, Moller DE. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:662–676. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Camp HS, Li O, Wise SC, Hong YH, Frankowski CL, Shen X, Vanbogelen R, Leff T. Diabetes. 2000;49:539–547. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Minoura H, Takeshita S, Ita M, Hirosumi J, Mabuchi M, Kawamura I, Nakajima S, Nakayama O, Kayakiri H, Oku T, Ohkubo-Suzuki A, Fukagawa M, Kojo H, Hanioka K, Yamasaki N, Imoto T, Kobayashi Y, Mutoh S. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;494:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schupp M, Clemenz M, Gineste R, Witt H, Janke J, Helleboid S, Hennuyer N, Ruiz P, Unger T, Staels B, Kintscher U. Diabetes. 2005;54:3442–3452. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.12.3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi GQ, Dropinski JF, McKeever BM, Xu S, Becker JW, Berger JP, MacNaul KL, Elbrecht A, Zhou G, Doebber TW, Wang P, Chao YS, Forrest M, Heck JV, Moller DE, Jones AB. J Med Chem. 2005;48:4457–4468. doi: 10.1021/jm0502135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant JA, Gallardo MA, Pickup BT. J Comput Chem. 1996;17:1653–1666. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Halgren TA, Murphy RB, Friesner RA, Beard HS, Frye LL, Pollard WT, Banks JL. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1750–1759. doi: 10.1021/jm030644s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berman H, Henrick K, Nakamura H. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:980. doi: 10.1038/nsb1203-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Available from: http://ligand-expo.rcsb.org

- 21.Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pcassay&term=631

- 22.Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pcassay&term=1032

- 23.Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pcassay&term=731

- 24.Willett P, Barnard JM, Downs GM. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1998;38:983–996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a) Rogers D, Brown RD, Hahn M. J Biomol Screen. 2005;10:682–686. doi: 10.1177/1087057105281365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hassan M, Brown RD, Varma-O’brien S, Rogers D. Mol Divers. 2006;10:283–299. doi: 10.1007/s11030-006-9041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Available from: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl

- 28.TIP. Eidogen-Sertanty Inc; San Diego, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.EVE. Eidogen-Sertanty Inc; San Diego, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omega2. OpenEye Scientific Software Inc; Santa Fe, NM: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.ROCS. OpenEye Scientific Software Inc; Santa Fe, NM: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hopkins CR, O’Neil VS, Laufersweiler MC, Wang Y, Pokross M, Mekel M, Evdokimov A, Walter R, Kontoyianni M, Petrey ME, Sabatakos G, Roesgen JT, Richardson E, Demuth TP., Jr Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:5659–5663. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maestro. Schrödinger LLC; Portland, OR: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.LigPrep. Schrödinger LLC; Portland, OR: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaminski GA, Friesner RA, Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:6474–6487. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glide. Schrödinger LLC; Portland, OR: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pipeline Pilot. Accelrys Software Inc; San Diego, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeLano WL. PyMOL. Schrödinger LLC; Portland, OR: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JB, Wright HM, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4333–4337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.