Abstract

Objective:

An accumulating body of work indicates that siblings uniquely influence each other’s alcohol and substance use behaviors during adolescence. The mechanisms underlying these associations, however, are unknown because most studies have not measured sibling influence processes. The present study addressed this gap by exploring the links between multiple influence processes and sibling similarities in alcohol and substance use.

Method:

The sample included one parent and two adolescent siblings (earlier born age: M = 17.17 years, SD = 0.94; later born age: M = 14.52 years, SD = 1.27) from 326 families. Data were collected via telephone interviews with parents and the two siblings.

Results:

A series of logistic regressions revealed that, after parents’ and peers’ use as well as other variables including parenting was statistically controlled for, older siblings’ alcohol and other substance use was positively associated with younger siblings’ patterns of use. Furthermore, sibling modeling and shared friends were significant moderators of these associations. For adolescents’ alcohol use, the links between sibling modeling and shared peer networks were interactive, such that the associations between modeling and similarity in alcohol use were stronger when siblings shared friends.

Conclusions:

Future research should continue to investigate the ways in which siblings influence each other because such processes are emerging targets for intervention and prevention efforts.

Studies designed to understand the etiology of adolescent substance use behaviors have consistently focused on four putative factors: (a) genetic risk, (b) environmental influences, (c) parental socialization, and (d) peer socialization. Yet, results from recent research also suggest that siblings (particularly older siblings) have a marked influence on adolescents’ alcohol and other substance use (e.g., Conger and Reuter, 1996; Duncan et al., 1996; Fagan and Najman, 2005; Rowe and Gulley, 1992; Windle, 2000). In fact, the results of several studies examining the relative contributions of family and peer influences on adolescents’ alcohol and other substance use have indicated that the magnitude of sibling influences is greater than parental influences (e.g., Ary et al., 1993; Fagan and Najman, 2005; Rowe and Gulley, 1992; Windle, 2000) and is on par with peer influences (Brook et al., 1990; Needle et al., 1986). Furthermore, behavioral genetic investigations of adolescents’ alcohol and substance use patterns have indicated that sibling linkages are greater than the contributions of genetic similarity (McGue et al., 1996; Rende et al., 2005; Slomkowski et al., 2005). In short, the accumulating evidence suggests that older siblings make a unique contribution to their younger brothers’ and sisters’ developing alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use behaviors. The mechanisms underlying the associations between siblings’ substance use, however, are not well understood because most studies fail to measure influence processes and therefore infer explanations post hoc. The present study addressed this limitation by directly exploring the links between several competing processes—including social learning, shared friends, and sibling relationship qualities—and sibling similarities in alcohol and other substance use.

Of the different mechanisms of sibling influence offered as explanations for observed similarities between siblings’ substance use patterns, social learning processes (Bandura, 1977) are by far the most common. Modeling hypotheses, which hold that older siblings act as role models for their younger brothers and sisters, have been postulated and to some extent indirectly tested. For example, studies have documented that sibling similarities in smoking behaviors and sexual activities were most evident in dyads that were characterized by high levels of warmth and closeness (Rowe and Gulley, 1992; Slomkowski et al., 2005). Other researchers have found that sibling similarities in alcohol use were greatest for same-gender sibling pairs who were close in age (e.g., Boyle et al., 2001; Trim et al., 2006). Such results are consistent with notions that individuals are most likely to imitate models who are warm and nurturing and who are similar to the observer (Bandura, 1977). By illuminating some of the dynamics underlying sibling similarities, findings like these provide a stronger foundation for inferences about the role of social learning processes in explaining sibling similarities.

More recently, however, researchers have incorporated measures of social learning, including modeling, into their studies to help identify the processes that drive sibling similarities. Several studies by Whiteman and colleagues (2007a, 2007b, 2010), for example, highlight that social learning processes were indeed predictive of sibling similarities in a range of domains, including youths’ interests and extracurricular activities, peer and romantic competencies, as well as risky behaviors and substance use attitudes. The present study builds on this work and examines the role of sibling modeling in adolescents’ alcohol and other substance use.

In addition to social learning processes, siblings can influence each other via their relationship dynamics as well as by providing companions and opportunities for engagement in substance use. The literature on youths’ antisocial and delinquent behaviors suggests that siblings may reinforce each other’s delinquent behavior patterns in their coercive interactions (Patterson, 1984), and reports from several longitudinal studies indicate that sibling conflict predicts deviancy as well as substance use (Bank et al., 2004; Brody et al., 2003; East and Khoo, 2005; Yeh and Lempers, 2004). Siblings may also foster opportunities for substance use by directly providing the illicit substances or the settings and companions that encourage substance use (Boyle et al., 2001; Forster et al., 2003; McGue et al., 1996; Needle et al., 1986; Rowe and Gulley, 1992; Windle, 2000). In fact, research reveals that siblings’ patterns of use are more strongly correlated when they share friends (e.g., Rende et al., 2005; Rowe and Gulley, 1992). Yet, as mentioned earlier, our knowledge about the extent to which these different influence processes operate is largely unknown because processes are rarely measured directly. Additionally, because most studies of sibling influence hypothesize multiple pathways of sibling influence (e.g., modeling, sibling conflict, shared peer networks), it is important to examine the relative contributions of these different influence processes simultaneously.

In the proposed study, we address limitations of prior work by measuring multiple processes hypothesized to underlie sibling similarities—modeling, shared friends, and relationship qualities—and examine their relative contributions to similarities and differences in adolescent siblings’ substance use behaviors. Based on previous research, we predicted that sibling negativity would be positively related to adolescents’ substance use. We also expected that younger siblings’ reports of modeling and shared friends would interact with older siblings’ substance use patterns, such that siblings would show the greatest similarity in substance use when they modeled or shared friends. Importantly, our models controlled for sibling intimacy, a variable that has been used as a proxy for modeling in previous work (e.g., Rowe and Gulley, 1992; Samek and Rueter, 2011; Slomkowski et al., 2005). Given that previous research has suggested that sibling and peer influence factors do not operate in isolation (e.g., Conger and Rueter, 1996), we further explored whether the shared peer networks moderated the effects of sibling modeling. Finally, to fully understand the contributions of these processes to sibling similarities in adolescents’ substance use, it is necessary to examine their influence in the context of parental and peer influence processes. Therefore, the present study controlled for both parents’ and peers’ substance use as well as parents’ knowledge of their adolescents’ daily behaviors (i.e., monitoring).

Method

Participants

Participants included two adolescent-aged siblings and one parent from 326 families (978 participants). On average, older siblings were 17.17 years old (SD = .94), younger siblings were 14.52 years old (SD = 1.27), and parents (87% mothers, 13% fathers; 98% were biological parents of the offspring) were 44.95 years old (SD = 5.54). The sample included 95 older sister–younger sister pairs, 72 older sister– younger brother pairs, 87 older brother–younger sister pairs, and 72 older brother–younger brother pairs. Seventyone percent of families identified themselves as White (not Hispanic), 23% as African American, 4% as Latino, 1% as multi-ethnicity, and 1% as Asian. Seventy-seven percent of parents were currently married. Seventy-five percent of participating parents were employed, and family socioeconomic circumstances varied from working to upper class, as indexed by parental education (97% of parents were high school graduates; 58% of parents held bachelor’s degrees) and household income (Mdn = $70,000; M = $77,964, SD = $72,806; range: $0–$980,000).

To generate the sample, we targeted families with adolescent children from seven different counties within one midwestern U.S. state. Counties varied in terms of their size and rurality. To increase the ethnic diversity of the sample, African American families were oversampled (23% of the current sample was African American as compared with a state average of 9%; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Names, addresses, and phone numbers of families that included at least two adolescent children from the seven target counties were identified from purchased marketing lists. Families were sent prenotification letters that described the study and included a telephone number, email address, and a postagepaid postcard to return if the family fit the study criteria and was interested in participating. Study criteria required that families have at least two adolescent-aged children, with the older adolescent being in the 11th or 12th grade and a younger sibling being in the 7th grade or above. A total of 6,854 addresses and phone numbers were provided by the marketing company; however, 3,002 of these contained incorrect contact information. Of the remaining 3,852 families, 2,556 did not follow up with the study project and were not contacted via phone by project staff; 511 indicated that they did not meet our study criteria and were therefore ineligible. Thus, a final pool of 785 eligible families was identified, 326 of which participated (a 42% response rate). This rate is comparable to the rate of 37% obtained in the National Survey of Families and Households in which three family members were recruited (Sweet and Bumpass, 1996; see also Booth et al., 2005).

Procedures

Consent forms were mailed to families after they were identified as eligible and interested in participating. Upon the return of informed consent and assent forms, telephone interviews were scheduled. Youths and parents were interviewed separately and privately. After the interview was scheduled, a scales sheet (one page consisting of the Likert scales to be used during the interview) for each participant was mailed to the family. Research assistants trained in standardized interviewing procedures conducted the interviews. To ensure confidentiality, participants were asked whether they had enough privacy to answer the questions comfortably. If lack of privacy was a concern for either the respondent or the interviewer, interviews were rescheduled for a later date. Parental interviews lasted about 30 minutes, and youth interviews lasted approximately 40 minutes. Following completion of the interviews, each participant received an honorarium of $35 for their participation (a total of $105 per family).

Measures

Demographic information.

Family background information including household composition, parents’ marital status, age, gender, and educational level for each family member was collected from parents. The gender constellation of the sibling dyad (51% same gender; 49% mixed gender) as well as the age spacing between siblings (M = 2.65 years, SD = 1.07) were derived from these parental data.

Alcohol use.

Earlier born and later born adolescents’ as well as parents’ alcohol use was indexed via one question from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s Task Force on Recommended Alcohol Questions (2003) that assessed the frequency of alcohol use in the past 12 months. Specifically, on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (several times a day), participants responded to the following question: “During the last 12 months, how often did you usually have any kind of drink containing alcohol? By drink we mean a 12-ounce can or glass of beer or cooler, a 5-ounce glass of wine, or a drink containing one shot of liquor.” Given that the distributions for older and younger siblings’ alcohol use were not normal, their responses were dichotomized to create an index of those who drank versus those who did not in the past year; 46% (n = 149) of older siblings and 19% (n = 62) of younger siblings reported drinking alcohol in the past year. The distribution for parents’ responses was normal; therefore, a continuous measure was used (M = 1.33, SD = 1.02).

Using the same 6-point scale, older and younger siblings also provided their perceptions of the frequency of their friends’ alcohol use by answering the following question: “How often do your friends drink alcohol?” Given distributional properties, responses were dichotomized: 67% (n = 219) of older siblings and 33% (n = 105) of younger siblings reported that their friends drank alcohol in the past year.

Cigarette use.

Adolescents’ cigarette use was assessed via one question adapted from the Monitoring the Future study (Johnston et al., 2006). On a 6-point scale, ranging from 0 (0 occasions) to 5 (20 or more occasions), respondents reported the number of occasions they smoked cigarettes in their lives. Similar to the measure of alcohol use, youths’ reports of cigarette use were dichotomized to create an index that compared those who smoked cigarettes versus those who did not: 32% (n = 104) of older siblings and 15% (n = 48) of younger siblings reported smoking cigarettes in their lifetimes.

Using the same 6-point scale, parents provided an indication of their current cigarette use by responding to the following question: “On how many occasions have you smoked cigarettes during the past 30 days?” Responses were dichotomized, with 15% (n = 49) of parents reporting smoking cigarettes in the past month.

On scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (several times a day), older and younger siblings also provided their perceptions of their friends’ cigarette use by answering the following question: “How often do your friends smoke cigarettes?” Responses were dichotomized, with 45% (n = 144) of older siblings and 24% (n = 75) of younger siblings reporting that their friends smoked cigarettes.

Marijuana use.

Adolescents’ marijuana use was measured in the same way as cigarette use. Specifically, on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (0 occasions) to 5 (20 or more occasions), youths were asked to report how often they smoked marijuana in their lives. Youths’ reports of marijuana use were dichotomized to create an index that compared those who had smoked marijuana versus those who had not: 31% (n = 100) of older siblings and 12% (n = 40) of younger siblings reported smoking marijuana in their lifetimes. Neither parents’ nor youths’ perceptions of peers’ marijuana use were assessed.

Sibling influence processes.

Younger siblings’ modeling of their older siblings’ behaviors was indexed via an eight-item measure developed by Whiteman and colleagues (2007b, 2010). Specifically, on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), youths answered questions about how often they tried to be like their sibling, the degree to which their older sibling set a positive example, and the extent to which their sibling encouraged them to participate in particular activities. Example items included the following: “My brother/sister provides a model for how I should act” and “From watching my brother/sister, I have learned how to do things.” Scores were averaged across the eight items, with higher scores indicating greater modeling. Total scores could range from 1 to 5 (M = 3.30, SD = 0.71; Cronbach’s α = .81).

Sibling relationship qualities.

Intimacy in the sibling relationship was rated by younger siblings using an adaptation of an eight-item measure developed by Blyth and colleagues (1982). Specifically, youths rated their experiences with their sibling on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). An example item is “How much do you go to your brother/sister for advice or support?” Intimacy scores were averaged across the eight items, with higher scores representing greater intimacy. Total scores could range from 1 to 5 (M = 3.27, SD = 0.68; Cronbach’s α = .81). Negativity in the sibling relationship was indexed using five items from Furman and Buhrmester’s (1985) Network Relationship Inventory. An example item is “How much do you and your brother/sister disagree or quarrel?” Items were rated on the same 5-point scale as intimacy, and scores were created by averaging items for the scale, with higher scores denoting greater negativity. Total scores could range from 1 to 5 (M = 3.13, SD = 0.89; Cronbach’s α = .91).

Siblings’ shared peer networks.

Siblings’ shared peer networks were indexed using a measure developed by Trim and colleagues (2006). Specifically, each sibling rated “To what extent do you and your brother/sister currently have the same friends?” on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), with higher scores reflecting more common peers. Given that older (M = 2.18, SD = 1.03) and younger (M = 2.45, SD = 1.08) siblings’ reports were correlated (r = .48, p < .001), their responses were averaged into a single index of shared friends (M = 2.31, SD = .91).

Parents’ knowledge of their children’s activities.

Parents’ knowledge of their children’s behaviors was assessed using Kerr and Stattin’s (2000; Stattin and Kerr, 2000) nine-item measure of parents’ knowledge about their sons’ and daughters’ everyday activities. On a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), parents indicated the extent to which they were aware of their children’s activities. Parents completed the measure separately for each child. An example item is “I know with whom he/she hangs out during his/her free time.” Knowledge scores were averaged across the nine items, with higher scores representing greater knowledge. Total scores could range from 1 to 5 (M = 4.46, SD = 0.47; Cronbach’s α = .85 for younger siblings).

Analytic strategy

Data were analyzed using a series of logistic regression models. To determine whether older siblings influenced their younger brothers’ and sisters’ substance use behaviors above and beyond other known correlates, each model controlled for parental education, family structure (dummy coded such that two biological parents = 0; single-parent and other family structures = 1), gender (females = 0; males = 1), parental knowledge, gender composition of the sibling dyad (same-gender dyads = 0; mixed-gender dyads = 1), age spacing between siblings, sibling intimacy, sibling negativity, parents’ substance use, and friends’ substance use. The type of substance use controlled for matched the dependent variable for each model, except for the model testing the association with youths’ marijuana use, in which parents’ and friends’ use was not measured. Independent variables of substantive interest were sibling modeling (centered at its mean), shared friends (centered at its Nonsignificant controls omitted from table: parental education, sex composition, age spacing, and gender. OR = odds ratio. mean), and older siblings’ substance use. Older siblings’ alcohol use was dummy coded (0 = did not drink alcohol in the past year; 1 = drank in the past year), as were siblings’ cigarette use and marijuana use (0 = never used; 1 = used in lifetime). For each outcome, variables were entered in three steps. In Step 1, all control and independent variables of interest were added simultaneously. In Step 2, three twoway interactions among the three independent variables were added. In Step 3, the three-way interaction between older sibling use, shared friends, and sibling modeling was entered.

Results

Alcohol use

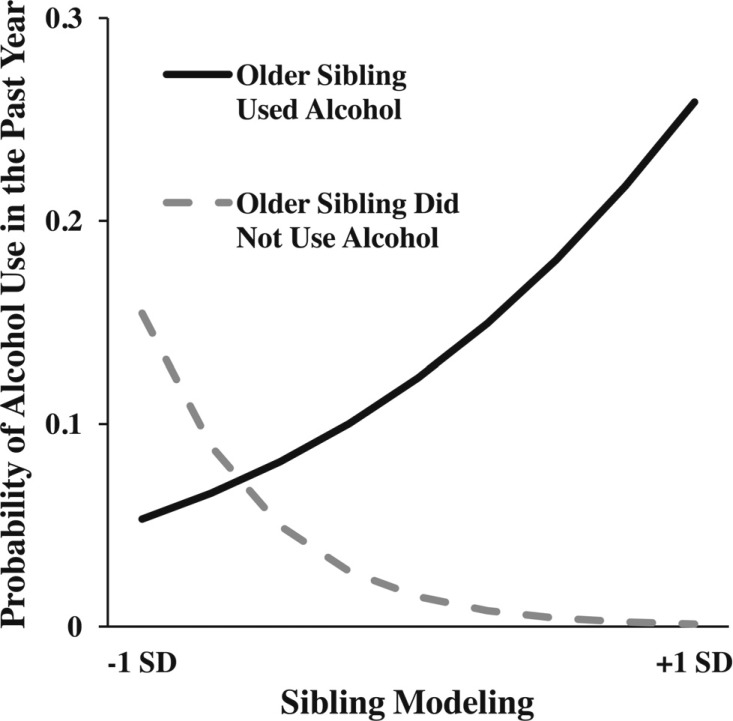

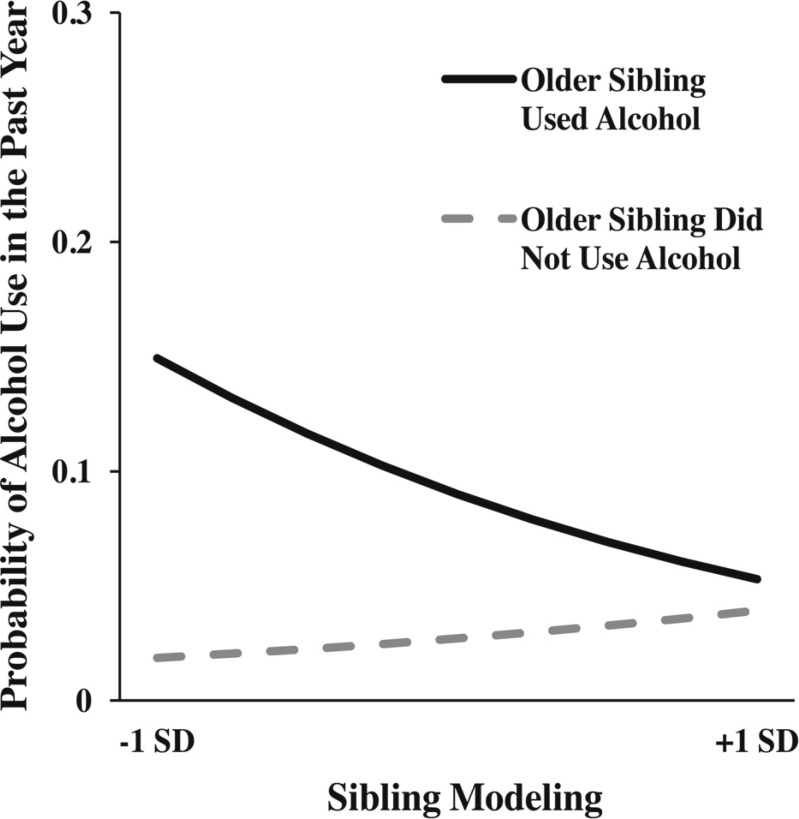

As seen in Table 1, in Model 1, friends’ and older siblings’ alcohol use was positively related to younger siblings’ alcohol use, whereas parental knowledge was negatively linked to youths’ drinking. Importantly, older siblings’ alcohol use was a stronger predictor of younger siblings’ drinking (odds ratio [OR] = 6.33) than either friends’ (OR = 3.46) or parents’ use (OR = 1.37). The association between older siblings’ alcohol use and younger siblings’ use was qualified, however, by interactions with sibling influence processes. In Model 2, a significant interaction was found between older siblings’ alcohol use and sibling modeling. Specifically, the positive association between older and younger siblings’ alcohol use was stronger in conditions of high sibling modeling. This two-way interaction, however, was further qualified by a three-way interaction between older siblings’ alcohol use, sibling modeling, and shared friends in Model 3. As seen in Figure 1, when siblings shared friends, the effects of modeling were exacerbated. That is, younger siblings who endorsed modeling their older brothers and sisters and shared friends with those siblings showed the greatest similarity in alcohol use. In contrast, youths who reported lower levels of modeling actually showed some dissimilarity in alcohol use. Sibling modeling was less predictive of sibling similarities, however, when youths shared fewer friends (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Summary of logistic regression analysis for variables predicting younger siblings’ alcohol use (n = 321)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||||

| Variable | B | OR | [95% CI] | B | OR | [95% CI] | B | OR | [95% CI] |

| Intercept | −3.66*** | −4.01*** | −3.89*** | ||||||

| Family structure | 0.29 | 1.35 | [0.63, 2.87] | 1.3 | 1.39 | [0.65, 2.99] | 0.55 | 1.73 | [0.76, 3.94] |

| Parental knowledge | −1.03** | 0.36 | [0.17,0.76] | −1.08** | 0.34 | [0.16,0.74] | −1.04* | 0.36 | [0.16,0.80] |

| Sibling intimacy | 0.02 | 1.03 | [0.47, 2.25] | 0.19 | 1.21 | [0.54, 2.72] | 0.26 | 1.30 | [0.55, 3.03] |

| Sibling conflict | 0.14 | 1.15 | [0.65, 2.02] | 0.14 | 1.50 | [0.65, 2.03] | 0.23 | 1.26 | [0.68, 2.35] |

| Parent’s alcohol use | 0.31 | 1.37 | [0.95, 1.98] | 0.27 | 1.31 | [0.89, 1.93] | 0.16 | 1.18 | [0.77, 1.79] |

| Friends’ alcohol use | 1.24*** | 3.46 | [2.38, 5.03] | 1.32*** | 3.76 | [2.52, 5.60] | 1.56*** | 4.76 | [2.99, 7.57] |

| Sibling’s alcohol use (sib. alc.) | 1.85*** | 6.33 | [2.83, 14.12] | 2.17*** | 8.72 | [3.46,21.96] | 1.75*** | 5.63 | [2.35, 13.98] |

| Shared friends (shr. fr.) | 0.14 | 1.15 | [0.41,0.52] | 0.141 | 1.15 | [0.73,3.12] | −0.34 | 0.71 | [0.31, 1.65] |

| Sibling modeling (mod.) | −0.13 | 0.88 | [0.18,0.67] | −1.45* | 0.23 | [0.07, 0.75] | −1.49 | 0.23 | [0.06, 0.84] |

| Sib. Alc. × Mod. | 1.64** | 5.15 | [1.49, 17.79] | 1.73* | 5.63 | [1.40,22.67] | |||

| Sib. Alc. × Shr. Fr. | −0.29 | 0.75 | [0.31, 1.82] | 0.53 | 1.70 | [0.63, 4.57] | |||

| Mod. × Shr. Fr. | 0.35 | 1.42 | [0.84, 2.42] | −2.23** | 0.11 | [0.02, 0.58] | |||

| Mod. × Sib. Alc. × Shr. Fr. | 3.38*** | 29.40 | [4.41, 196.19] | ||||||

| χ2 | 107.81 | 116.18* | 133.95*** | ||||||

| df | 13 | 16 | 17 | ||||||

Notes: Nonsignificant controls omitted from table: parental education, sex composition, age spacing, and gender. OR = odds ratio.

p < .05;

p <.01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

The probability of younger siblings’ alcohol use as a function of modeling and older siblings’ alcohol use in conditions of high (+1 SD) shared friends

Figure 2.

The probability of younger siblings’ alcohol use as a function of modeling and older siblings’ alcohol use in conditions of low (-1 SD) shared friends

Cigarette use

With respect to adolescents’ cigarette use, several main effects emerged in Model 1 (Table 2). A main effect of family structure revealed that youths from homes without two biological parents were more likely to have ever used cigarettes. Similar to alcohol use, parental knowledge was negatively associated with youths’ lifetime cigarette use. Friends’ cigarette use was associated with an increased likelihood of youths having ever used cigarettes (OR = 2.22). Model 2 revealed effects for older siblings’ cigarette use. Specifically, adolescents who had older siblings who smoked cigarettes were 2.31 times more likely to have smoked cigarettes themselves compared to those whose older siblings did not smoke. An interaction between sibling modeling and shared friends also was observed. Post hoc probing revealed increasing probabilities of smoking cigarettes when younger siblings reported high modeling and more shared friends. In contrast, there was a slight negative association between sibling modeling and the probability of smoking when siblings did not share many friends. Given that this interaction did not involve older siblings’ cigarette use, however, results should be interpreted with caution. Model 3 (not shown in Table 2) did not reveal any three-way interactions.

Table 2.

Summary of logistic regression analysis for variables predicting younger siblings’ cigarette use (n = 322)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||

| Variable | B | OR | [95% CI] | B | OR | [95% CI] |

| Intercept | −2 72*** | −2.90*** | ||||

| Family structure | 1.05** | 2.87 | [1.36,6.04] | 1.10** | 2.99 | [1.40,6.37] |

| Parental knowledge | −0.97** | 0.38 | [0.18,0.79] | −0.99** | 0.37 | [0.18,0.78] |

| Sibling intimacy | 0.29 | 1.34 | [0.58,3.10] | 0.29 | 1.34 | [0.57,3.18] |

| Sibling conflict | −0.02 | 0.98 | [0.54, 1.76] | 0.01 | 1.01 | [0.56, 1.82] |

| Parent’s cigarette use | 0.47 | 1.60 | [0.64, 4.03] | 0.36 | 1.43 | [0.55, 3.70] |

| Friends’ cigarette use | 0.80*** | 2.22 | [1.67,2.94] | 0.82*** | 2.26 | [1.69,3.03] |

| Sibling’s cigarette use (sib. cig.) | 0.73 | 2.08 | [0.98, 4.40] | 0.84* | 2.31 | [1.04,5.17] |

| Shared friends (shr. fr.) | −0.45 | 0.64 | [0.39, 1.05] | −0.63 | 0.54 | [0.27, 1.06] |

| Sibling modeling (mod.) | −0.16 | 0.85 | [0.46, 1.59] | 0.36 | 1.44 | [0.60, 3.43] |

| Sib. Cig. × Mod. | −0.68 | 0.51 | [0.17, 1.50] | |||

| Sib Cig × Shr. Fr. | 0.37 | 1.45 | [0.54, 3.88] | |||

| Mod. × Shr. Fr. | 0.64* | 1.89 | [1.04,3.42] | |||

| χ2 | 74.27 | 79.27 | ||||

| df | 13 | 16 | ||||

Notes: Nonsignificant controls omitted from table: parental education, sex composition, age spacing, and gender. OR = odds ratio.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Marijuana use

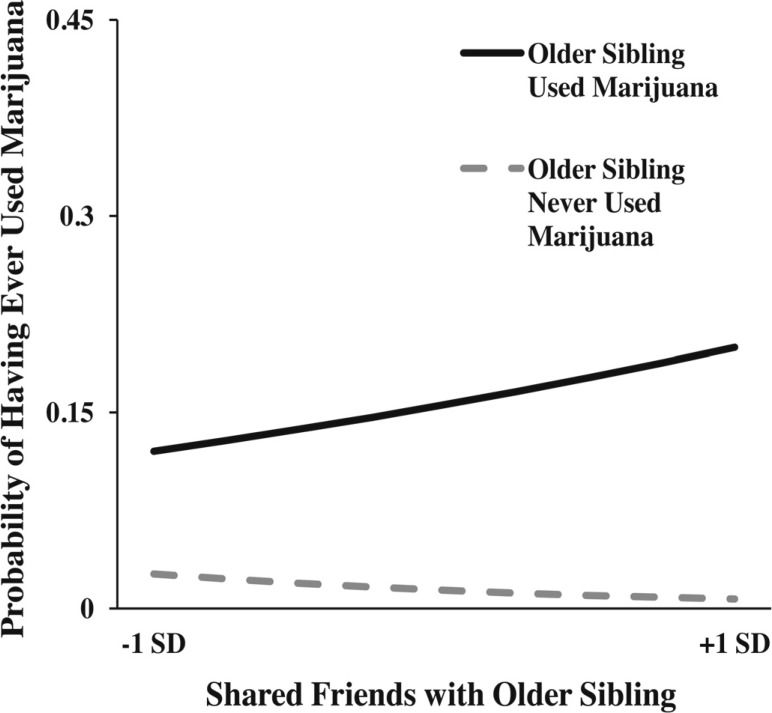

Marijuana use results are presented in Table 3. Model 1 revealed that youths with older brothers or sisters who had ever used marijuana were more than six times as likely (OR = 6.50) to have used marijuana. A main effect for parental knowledge indicated that youths with more knowledgeable parents were less likely to smoke marijuana. Model 2 revealed a significant interaction between older siblings’ marijuana use and shared friends. As seen in Figure 3, younger siblings’ probability of ever smoking marijuana was strongest when their older sibling smoked marijuana and they shared friends. Younger siblings whose older brothers and sisters did not smoke marijuana were not likely to smoke marijuana regardless of their degree of shared friends. Model 3 (not shown in Table 3) did not reveal any three-way interactions.

Table 3.

Summary of logistic regression analysis for variables predicting younger siblings’ marijuana use (n = 324)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||

| Variable | B | OR | [95% CI] | B | OR | [95% CI] |

| Intercept | −3.42*** | −3.66*** | ||||

| Family structure | 0.67 | 1.95 | [0.92,4.16] | 0.66 | 1.93 | [0.88, 4.20] |

| Parental knowledge | −0.80* | 0.49 | [0.22, 0.93] | −0.87* | 0.42 | [0.20, .89] |

| Sibling intimacy | 0.09 | 1.10 | [0.49, 2.45] | 0.05 | 1.05 | [0.46, 2.40] |

| Sibling conflict | 0.52 | 1.68 | [0.93, 3.06] | 0.55 | 1.74 | [0.95,3.18] |

| Sibling’s marijuana use (sib. marij.) | 1.87*** | 6.50 | [2.97, 14.22] | 2.15*** | 8.61 | [3.60, 20.59] |

| Shared friends (shr. fr.) | −0.15 | 0.86 | [0.54, 1.37] | −0.60 | 0.55 | [0.25, 1.21] |

| Sib modeling (mod.) | 0.03 | 1.03 | [0.55, 1.95] | −0.12 | 0.89 | [0.31,2.51] |

| Sib. Marij. × Mod. | 0.41 | 1.51 | [0.46, 4.94] | |||

| Sib. Marij. × Shr. Fr. | 0.97* | 2.63 | [1.00, 6.93] | |||

| Mod. × Shr. Fr. | 0.53 | 1.70 | [0.95, 3.05] | |||

| χ2 | 50.39 | 61.01** | ||||

| df | 11 | 14 | ||||

Notes: Nonsignificant controls omitted from table: parental education, sex composition, age spacing, and gender. OR = odds ratio.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p < .001.

Figure 3.

The probability of younger siblings’ marijuana use as a function of older siblings’ marijuana use and siblings’ shared friends

Discussion

Accumulating evidence highlights that siblings, especially older siblings, influence each other’s alcohol and substance use behaviors during adolescence and early adulthood (e.g., Conger and Rueter, 1996; Fagan and Najman, 2005; Trim et al., 2006; Windle, 2000). The processes by which brothers and sisters influence each other, however, are not well understood because they have rarely been tested directly and few studies have considered multiple pathways of influence concurrently. The present study adds to the literature on sibling influence in its effort to measure multiple avenues of influence, as opposed to inferring them post hoc, and to connect those processes to similarities and differences in adolescent siblings’ patterns of alcohol and substance use. Importantly, processes of sibling influence were considered above and beyond the associations with parental and peer substance use, as well as important indicators of parenting, indicating that the associations between older and younger siblings’ substance use behaviors were indeed unique.

Consistent with extant work on family influences on adolescents’ alcohol use, older siblings’ alcohol use was strongly related to younger siblings’ probability of drinking in the past year. In fact, when considering only main effects, the influence of older siblings’ drinking on younger siblings’ alcohol use was greater than the effects for both peers’ and parents’ alcohol use. Although previous studies have inferred social learning processes as explanations for such patterns of association (e.g., Ary et al., 1993; Rowe and Gulley, 1992), the present study found empirical support for the hypothesis that younger siblings’ modeling behaviors were predictive of similarities in adolescent siblings’ alcohol use. Importantly, these modeling effects were evident beyond the contributions of sibling intimacy, age spacing, and gender composition of the sibling dyad, variables that have been used as proxies for social learning processes in the past. Additionally, these effects were present even after we controlled for sibling conflict, a significant predictor of substance use and delinquency in previous work (Bank et al., 2004; Brody et al., 2003; East and Khoo, 2005; Yeh and Lempers, 2004), which was generally unrelated to adolescents’ substance use in these data.

The influence of modeling, however, was further moderated by the degree to which older and younger siblings shared friends. Specifically, the links between sibling modeling and sibling similarities in alcohol use were stronger when siblings shared friends. Although scholars have suggested that siblings may indirectly influence each other’s substance use attitudes and behaviors via peer selection (e.g., Conger and Rueter, 1996; Rowe and Gulley, 1992), research to date has failed to consider how multiple influence processes operate simultaneously and possibly interactively. The results of the present study suggest that the impact of older siblings’ alcohol use may be especially powerful when combined with the admiration and modeling of younger brothers and sisters as well as with overlapping peer networks.

The results from alcohol models also highlight the potential operation of another less discussed sibling influence process—sibling differentiation. Sibling differentiation (also termed deidentification; Schachter et al., 1976; Sulloway, 1996) refers to the tendency for siblings to consciously or unconsciously choose different niches and develop different personal qualities to protect themselves from social comparison, rivalry, and resentment. In the present study, when younger siblings shared friends with their older brothers and sisters but did not model those siblings, dissimilarity in alcohol use was elevated. Specifically, younger siblings who reported low levels of modeling and had older siblings who drank alcohol were less likely to drink themselves as compared with similar youth with older brothers and sisters who did not drink. A small body of literature highlights the operation of sibling differentiation dynamics across a range of outcomes including personality (Schachter et al., 1976), adjustment (Feinberg and Hetherington, 2000), and extracurricular activities and attitudes (Whiteman et al., 2007a, 2010) but has largely failed to consider how these influence processes affect adolescents’ substance use. As the literature on family influences on adolescents’ alcohol use documents, aggregate reports of older and younger siblings’ substance use indicate (only) modest similarity. To the extent that social learning processes operate in some sibling relationships and differentiation dynamics are predominant in others, conclusions about the strength of sibling influence based on extant data may be misleading. Given the complexity of sibling relationship dynamics, it is essential that future research consider processes that may promote similarities as well as differences to truly understand the impact of siblings on adolescents’ substance use.

Consistent with previous research on cigarette use (e.g., Bard and Rodgers, 2003; Rajan et al., 2003; Slomkowski et al., 2005), our study also revealed that older siblings’ cigarette use was positively related to their younger brothers’ and sisters’ use. None of the measured processes of influence, however, moderated this association. The work of Slomkowski and colleagues (2005) as well as Rende et al. (2005) suggests that other processes, including siblings’ social connectedness, may explain such associations. As such, future work may benefit from the investigation of a greater number of influence processes. Given the relatively small percentage of adolescents reporting cigarette use (as well as marijuana use), it is also possible that the present study lacked the power to detect such effects.

Similar to the results for cigarette use, older siblings’ marijuana use was positively related to younger siblings’ marijuana use. An interaction with siblings’ peer networks revealed that this effect was stronger when brothers and sisters shared more friends. Because access to illicit drugs such as marijuana may be more limited than alcohol or cigarettes, shared peer networks may be especially important for mechanisms of transmission. These results should be interpreted with caution, however, as sibling effects may have been amplified because neither peer nor parental marijuana use was controlled.

The present study was limited by other methodological shortcomings that may also restrict our conclusions. First, because of our cross-sectional design, we were unable to disentangle whether sibling influence processes led to similarities in siblings’ alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use or vice versa. Longitudinal data are essential to understand not only the implications of these influence processes but also how they may develop over time. Additionally, the magnitude of our effects may be inflated because research has suggested that sibling effects tend to be greatest when measured concurrently as opposed to prospectively (Ary et al., 1993; Duncan et al., 1996; Poelen et al., 2007).

Second, although telephone surveys have been shown to be a valid and reliable method for gathering data on adolescent alcohol and drug use (e.g., Aquilino, 1992; Champion et al., 2004; Shannon et al., 2007) and procedures were put in place to secure confidentiality, fewer adolescents in this sample reported alcohol and substance use as compared with national samples (e.g., Johnston et al., 2012). It is possible that adolescents underreported their use, and as such, the present study may underestimate or misestimate potential associations.

Third, our measures of substance use were limited to single items. Greater variability in adolescents’ substance use may be detected if a broader range of questions are assessed. Additionally, our measures of sibling influence and substance use relied on adolescents’ self-reports. Although correlated self-reports can be related to method variance problems (e.g., Lorenz et al., 1991), the present study was among the few that used independent reports of family members’ substance use.

Fourth, although the sample was ethnically diverse, families were more affluent and educated as compared with state averages (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). When considered together with the response rate, it is possible that families from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were less likely to be contacted or choose to participate. Given the complex associations between family income, parents’ education, and adolescents’ substance use (e.g., Melotti et al., 2011), it is important that future research consider these dynamics in families across a larger range of socioeconomic statuses.

Fifth, consistent with most work on sibling influence, the present study tested a vertical or top-down model of socialization (i.e., older sibling influencing younger siblings). The ways in which younger siblings influence their older brothers and sisters are largely unknown (for some exceptions, see Pomery et al., 2005; Whiteman and Christiansen, 2008). It is essential that future research consider how younger siblings affect their older counterparts to advance our understanding of how and when sibling influence occurs.

Finally, because our design was not genetically informed, we were unable to determine the extent to which sibling similarity was influenced by shared environments or shared genetics. Indeed, shared environments—including parenting, schools, neighborhoods, and media exposure—could promote sibling similarity. It is also possible that genetic similarity in propensity for substance use leads to similarity in environments and behavior through evocative processes such as niche picking (Scarr, 1992). Sibling influence processes such as modeling, however, may be one set of mediators of links between genotypic and phenotypic similarities between siblings. Given that previous research with genetically informed designs has found that siblings uniquely contribute to each other’s substance use behaviors above and beyond genetic and shared environmental factors (McGue et al., 1996; Rende et al., 2005; Slomkowski et al., 2005), it is essential that future studies continue to consider the processes that drive such effects.

Despite these limitations, the present study adds to a growing body of literature on sibling influences on adolescents’ alcohol and other substance use. Findings revealed that social learning processes, such as modeling and siblings’ shared peer networks, were important predictors of sibling similarities, even after other known family and peer correlates were controlled for. Given that older siblings often recognize their status as role models for their younger brothers and sisters (Whiteman and Christiansen, 2008), they may serve as effective targets for intervention and prevention programs targeting adolescent substance use. In fact, interventions targeting sibling relationships may be especially useful as compared with those targeting parenting, as scholars (Feinberg et al., 2012) have argued that siblings offer a less stigmatizing entrée into families.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R21-AA017490 (to Shawn D. Whiteman). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aquilino WS. Telephone versus face-to-face interviewing for household drug use surveys. International Journal of the Addictions. 1992;27:71–91. doi: 10.3109/10826089109063463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ary DV, Tildesley E, Hops H, Andrews J. The influence of parent, sibling, and peer modeling and attitudes on adolescent use of alcohol. International Journal of the Addictions. 1993;28:853–880. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Burraston B, Snyder J. Sibling conflict and ineffective parenting as predictors of adolescent boys’ antisocial behavior and peer difficulties: Additive and interactional effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bard DE, Rodgers JL. Sibling influence on smoking behavior: A within-family look at explanations for a birth-order effect. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:1773–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth DA, Hill JP, Thiel KS. Early adolescents’ significant others: Grade and gender differences in perceived relationships with familial and nonfamilial adults and young people. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1982;11:425–450. doi: 10.1007/BF01538805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Johnson DR, Granger DA. Testosterone, marital quality, and role overload. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:483–498. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Sanford M, Szatmari P, Merikangas K, Offord DR. Familial influences on substance use by adolescents and young adults. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2001;92:206–209. doi: 10.1007/BF03404307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Kim SY, Murry VM, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Conger RD. Neighborhood disadvantage moderates associations of parenting and older sibling problem attitudes and behavior with conduct disorders in African American children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:211–222. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Gordon AS, Brook DW. The role of older brothers in younger brothers’ drug use viewed in the context of parent and peer influences. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development. 1990;151:59–75. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1990.9914644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion HLO, Foley KL, DuRant RH, Hensberry R, Altman D, Wolfson M. Adolescent sexual victimization, use of alcohol and other substances, and other health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Rueter MA. Siblings, parents, and peers: A longitudinal study of social influences in adolescent risk for alcohol use and abuse. In: Brody GH, editor. Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences. Westport, CT: Ablex; 1996. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. The role of parents and older siblings in predicting adolescent substance use: Modeling development via structural equation latent growth methodology. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:158–172. [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Khoo ST. Longitudinal pathways linking family factors and sibling relationship qualities to adolescent substance use and sexual risk behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:571–580. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Najman JM. The relative contributions of parental and sibling substance use to adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:869–883. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Hetherington EM. Sibling differentiation in adolescence: Implications for behavioral genetic theory. Child Development. 2000;71:1512–1524. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Solmeyer AR, McHale SM. The third rail of family systems: Sibling relations, mental and behavioral health, and preventive intervention in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;15:43–57. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0104-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster J, Chen V, Blaine T, Perry C, Toomey T. Social exchange of cigarettes by youth. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:148–154. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2005. Volume 1: Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 06-5883) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2011. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Simon RL, Whitbeck LB, Elder GH., Jr. Economic pressure and marital quality: An illustration of the method variance problem in the causal modeling of family processes. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53:375–388. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Sharma A, Benson P. Parent and sibling influences on adolescent alcohol use and misuse: Evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:8–18. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotti R, Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Araya R, Lewis G the ALSPAC Birth Cohort. Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use and early socioeconomic position: The ALSPAC birth cohort. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e948–e955. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Task Force on Recommended Alcohol Questions. Recommended sets of alcohol consumption questions. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/guidelines-and-resources/recommended-alcohol-questions. [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, McCubbin H, Wilson M, Reineck R, Lazar A, Mederer H. Interpersonal influences in adolescent drug use—the role of older siblings, parents, and peers. International Journal of the Addictions. 1986;21:739–766. doi: 10.3109/10826088609027390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Siblings: Fellow travelers in coercive family processes. In: Blanchard RJ, editor. Advances in the study of aggression. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 174–214. [Google Scholar]

- Poelen EAP, Scholte RH, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI, Engels RCME. Drinking by parents, siblings, and friends as predictors of regular alcohol use in adolescents and young adults: A longitudinal twin-family study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2007;42:362–369. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomery EA, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Brody GH, Wills TA. Families and risk: Prospective analyses of familial and social influences on adolescent substance use. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:560–570. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan KB, Leroux BG, Peterson AV, Jr, Bricker JB, Andersen MR, Kealey KA, Sarason IG. Nine-year prospective association between older siblings’ smoking and children’s daily smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rende R, Slomkowski C, Lloyd-Richardson E, Niaura R. Sibling effects on substance use in adolescence: Social contagion and genetic relatedness. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:611–618. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Gulley BL. Sibling effects on substance abuse and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Samek DR, Rueter MA. Considerations of elder sibling closeness in predicting younger sibling substance use: Social learning versus social bonding explanations. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:931–941. doi: 10.1037/a0025857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S. Developmental theories for the 1990s: Development and individual differences. Child Development. 1992;63:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter FF, Shore E, Feldman-Rotman S, Marquis RE, Campbell S. Sibling deidentification. Developmental Psychology. 1976;12:418–427. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon EE, Mathias CW, Marsh DM, Dougherty DM, Liguori A. Teenagers do not always lie: Characteristics and correspondence of telephone and in-person reports of adolescent drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:288–291. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomkowski C, Rende R, Novak S, Lloyd-Richardson E, Niaura R. Sibling effects on smoking in adolescence: Evidence for social influence from a genetically informative design. Addiction. 2005;100:430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulloway FJ. Born to rebel: Birth order, family dynamics, and creative lives. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet JA, Bumpass LL. The National Survey of Families and Households – Waves 1 and 2: Data description and documentation. University of Wisconsin-Madison: Center for Demography and Ecology; 1996. Retrieved from http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/nsfh/home.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Trim RS, Leuthe E, Chassin L. Sibling influence on alcohol use in a young adult, high-risk sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:391–398. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. State & county quick facts. 2010 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/18000.html. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, Bernard JM, McHale SM. The nature and correlates of sibling influence in two-parent African American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:267–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, Christiansen AE. Processes of sibling influence in adolescence: Individual and family correlates. Family Relations. 2008;57:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Competing processes of sibling influence: Observational learning and sibling deidentification. Social Development. 2007a;16:642–661. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Explaining sibling similarities: Perceptions of sibling influences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007b;36:963–972. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh H-C, Lempers JD. Perceived sibling relationships and adolescent development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:133–147. [Google Scholar]