Abstract

Transient potential receptor melastatin-2 (TRPM2) is a non-selective Ca2+-permeable cation channel of the TRPM channel subfamily and is mainly activated by intracellular adenosine diphosphate ribose (ADPR). Here we synthesized a 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl caged ADPR (NPE-ADPR) and found that uncaging of NPE-ADPR efficiently stimulated Ca2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+ influx in a concentration-dependent manner in intact human Jurkat T-lymphocytes. The cation influx was inhibited by inhibitors or knockdown of TRPM2. Likewise, uncaging of NPE-ADPR markedly induced cation entry in HEK 293 cells that overexpress TRPM2. As expected, high temperature increased the ability of the photolyzed NPE-ADPR to induce cation entry, whereas acidic pH inhibited. Moreover, the absence of extracellular Ca2+ significantly inhibited Mg2+ and Zn2+ influx after uncaging NPE-ADPR. On the other hand, the absence of extracellular Na+ or Mg2+ had no effect on photolyzed NPE-ADPR induced Ca2+ entry. Taken together, our results indicated that NPE-ADPR is a cell permeable ADPR analogue that is useful for studying TRPM2-mediated cation entry in intact cells.

Introduction

TRPM2 is a non-selective cation channel that is Ca2+ permeable. It has six transmembrane domains, and is best known as a ‘chanzyme’ due to its function as both ion channel and pyrophosphatase. The pyrophosphatase (Nudix-like) domain of TRPM2 is located at its C-terminus, and a calmodulin binding IQ-like motif is located at its N-terminus. The pore forming region of TRPM2 sits between the 5th and 6th transmembrane domains with the N- and C-termini lying in the cytoplasm. TRPM2 in some tissues is expressed in multiple isoforms, yet the significance of these isoforms remains to be determined [1]–[3]. Although TRPM2 is primarily located at the plasma membrane, it has also been detected on lysosomes, possibly acting as a Ca2+ releasing channel in the acid Ca2+ store [4].

TRPM2 mediated Ca2+ influx has been indicated in several physiological and pathophysiological processes, including insulin secretion, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, permeability of endothelium, and dendritic cell maturation and chemotaxis [4]–[11]. Since TRPM2 can be activated by oxidative stress, it has recently emerged as a potential therapeutic target in fighting oxidative stress-related diseases, including diabetes, inflammation, myocardial infarction, and neurodegenerative diseases [12]–[16]. In addition, genetic variants of the TRPM2 gene have been associated with Western Pacific amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, parkinsonism-dementia, and bipolar disorders [17]–[20].

The most potent and primary intracellular activator for TRPM2 is adenosine diphosphate ribose (ADPR) via its Nudix-like domain [21]. Intracellular ADPR can be generated from the hydrolysis of NAD+ by glycohydrolases, e.g., the mitochondrial NADase and CD38, in response to a wide variety of physiological stimuli, including oxidative and nitrosative stress, beta amyloid, and tumor necrosis factor [11],[22]–[24]. ADPR can also be generated in the nucleus by the sequential action of poly-ADPR polymerases and poly-ADPR glycohydrolases that are triggered by DNA damage [25],[26]. On the other hand, adenosine monophosphate (AMP), generated from hydrolysis of ADPR by TRPM2's pyrophosphatase activities, is a potent inhibitor of TRPM2, constituting a negative feedback loop to shut down the activation of TRPM2 by ADPR [27]. In addition, cell stress can activate Sir2 deacetylases to produce 2′-O-acetyl-ADPR, which can directly gate TRPM2 for Ca2+ influx [28],[29]. NAADP or cADPR, the other two products of CD38, can also either directly or in synergy with ADPR activate TRPM2 [30]. The gating of TRPM2 is influenced by [Ca2+]i, temperature, and pH as well [8],[31]–[35].

Given the importance of TRPM2 in diverse cellular processes and ADPR as its main activator, it is surprising that few ADPR analogues have been synthesized. Thus far, the studies on TRPM2 were mainly done by patch clamp recording with dialyzed ADPR. Here we synthesized a 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl caged ADPR (NPE-ADPR) and found that uncaging of NPE-ADPR induced multiple cation entry in intact human Jurkat and HEK293 cells via TRPM2.

Results

Synthesis And Purification Of Npe-Adpr

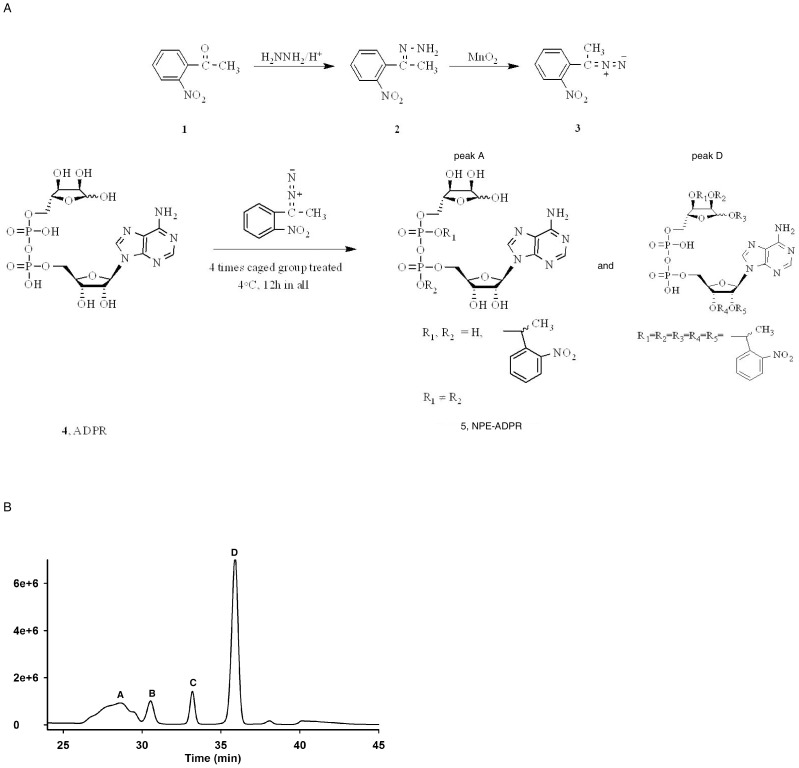

As the main intracellular activator of TRPM2, ADPR is hydrophilic and cannot cross the plasma membrane. Thus far, the studies on TRPM2 were mainly performed by patch clamp recording in single cells. Therefore, cell-permeant ADPR analogues should be valuable research tools in dissecting the mechanism of TRPM2-induced cation entry. We reasoned that adding a caged group to one of the phosphates on ADPR could increase its membrane permeability and enable it to accumulate inside cells. Photolysis by UV can then release the bioactive ADPR to activate TRPM2 for cation entry, thereby providing more precise control in studying the TRPM2/ADPR signaling in multiple cells simultaneously. We screened a series of caged groups, and found that only the 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl (NPE) caged group can be successfully linked to one of the phosphates of ADPR (Figure 1A). Analyses by HPLC showed that the reaction mixture contained four peaks (Figure 1B). By mass spectrometry and NMR analyses, we found that peak A contained the predicated NPE caged ADPR isomers with one NPE coupled to one of the phosphates, whereas peak D contained an unexpected NPE-ADPR product with five NPE groups reacted with all the hydroxyl groups in the riboses. Peaks B and C did not contain any ADPR related products.

Figure 1. Synthesis and purification of 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl (NPE)-ADPR.

(A) Synthesis route of NPE-ADPR. (B) HPLC purification of NPE-ADPR.

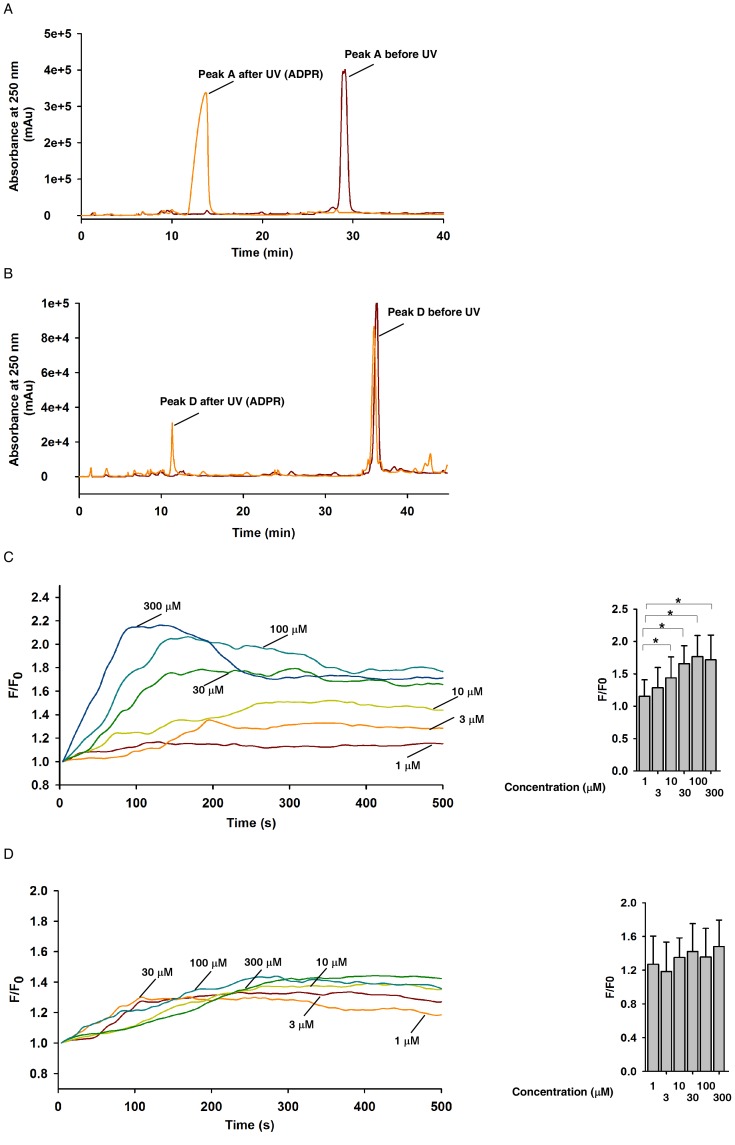

Purified peak A and peak D were then subjected to photolysis by UV illumination, and subsequently analyzed by HPLC. After UV activation, only peak A was efficiently uncaged to generate free ADPR (Figure 2A), whereas very little of peak D was photolyzed to free ADPR (Figure 2B), indicating that the bond between NPE and the hydroxyl groups of the riboses is stable.

Figure 2. Characterization of NPE-ADPR.

(A) and (B) HPLC analysis of Peak A (A) and peak D (B) before and after UV photolysis. (C) and (D) The concentration response curve of Ca2+ increase in human Jurkat cells induced by peak A (C) and peak D (D) after UV photolysis. Fluo-4 loaded cells were incubated in regular HBSS containing extracellular Ca2+ during the experiment. Data quantifications of [Ca2+]i peak induced by drug treatment in (C) and (D) were expressed as mean ± S.D., n = 30–40 cells. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells treated with 1 µM NPR-ADPR. In (C) and (D), cells were all continuously incubated with NPE-ADPR, and UV photolysis started at the beginning of the measurement and was repeated every 7 second throughout the experiments.

Uncaged Npe-Adpr Induction Of Ca2+ Influx

Next, we examined whether peak A or peak D could induce intracellular Ca2+ increases in human Jurkat T cells after UV illumination. Fluo-4 loaded cells were incubated with NPE-ADPR for 5 min and then subjected to Ca2+ measurement without removing the compound in the medium. As shown in Figure 2C, peak A induced cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i)increases in Jurkat cells in a concentration dependent manner after UV photolysis. On the other hand, peak D only marginally induced [Ca2+]i changes independent of the concentration after UV activation (Figure 2D), again confirming that the bond between NPE and the hydroxyl groups of the riboses is resistant to UV photolysis. In addition, peak A did not evoke any Ca2+ changes in Jurkat cells without UV uncaging, and UV illumination in the absence of NPE-ADPR also failed to induce Ca2+ (Figure S1). Therefore, we only characterized the properties of peak A, named as NPE-ADPR, in the later experiments.

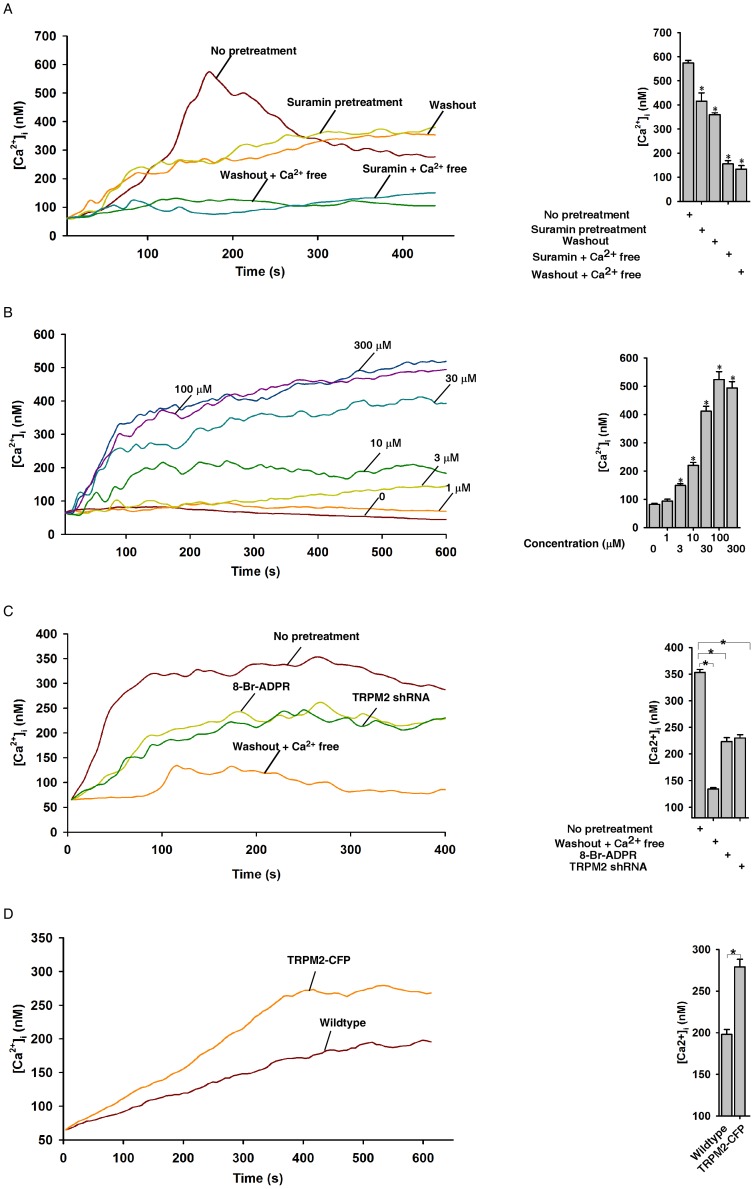

We traced the sources of the [Ca2+]i increases induced by uncaging NPE-ADPR. Since external ADPR induced [Ca2+]i increases in Jurkat cells (Figure S2) and other cell types [36], we pretreated Jurkat cells with suramin [337], a potent P2Y receptor blocker, to eliminate the effects of extracellular ADPR on [Ca2+]i. Indeed, suramin pretreatment markedly inhibited the photolyzed NPE-ADPR from inducing [Ca2+]i increases, in which the pattern of Ca2+ changes resembled that observed in the absence of extracellular NPE-ADPR (Figure 3A). Furthermore, removal of both extracellular Ca2+ and NPE-ADPR abolished the photolyzed NPE-ADPR from inducing [Ca2+]i increases. Similarly, the combination of suramin pretreatment and removal of extracellular Ca2+ prevented the photolyzed NPE-ADPR from inducing [Ca2+]i increases as well (Figure 3A). These data indicated that NPE-ADPR can enter intact Jurkat cells and trigger Ca2+ influx after UV photolysis. In the later experiments, we mainly studied the effects of intracellular NPE-ADPR by removing the extracellular compound through cell washing after loading.

Figure 3. Characterization of the NPE-ADPR-induced Ca2+ increase.

(A) The photolyzed NPE-ADPR (30 µM)-induced Ca2+ increases in Fluo-4 loaded human Jurkat cells were inhibited by suramin or removal of extracellular Ca2+ (washout), and was completely abolished by combination of removal of extracellular Ca2+ and extracellular NPE-ADPR or by combination of removal of extracellular Ca2+ and suramin pretreatment. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells without pretreatment. (B) Uncaging of intracellular NPE-ADPR triggered Ca2+ increases in a concentration dependent manner in Fluo-4 loaded human Jurkat cells in regular HBSS containing extracellular Ca2+. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells loaded with buffer only. (C) Pretreatment of Jurkat cells with 8-Br-ADPR (100 µM) or knockdown of TRPM2 significantly inhibited the photolyzed NPE-ADPR (30 µM) induced Ca2+ influx in Fluo-4 loaded Jurkat cells. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells without pretreatment. (D) Uncaging of NPE-ADPR (30 µM) induced Ca2+ influx in Fluo-4 loaded HEK293 cells that transiently express TRPM2-CFP. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05. Data quantifications of [Ca2+]i peak induced by drug treatment in (A), (B), (C), and (D) were expressed as mean ± S.E., n = 30–40 cells. In (B), (C), and (D), after Fluo-4 loaded cells were incubated with NPE-ADPR, extracellular NPE-ADPR was then removed before UV photolysis to start Ca2+ measurement.

After removal of extracellular NPE-ADPR, uncaged NPE-ADPR still induced [Ca2+]i increases in a concentration dependent manner in Jurkat cells, albeit at lesser extent than without washing (Figure 3B). Moreover, pretreatment of cells with the TRPM2 antagonist, 8-Br-ADPR [38], or knockdown of TRPM2 [39] in Jurkat cells significantly inhibited the photolyzed NPE-ADPR-induced [Ca2+]i increases (Figure 3C). Similarly, in the presence of suramin, pretreatment with 8-Br-ADPR or after TRPM2 knockdown, the photolyzed NPE-ADPR induced [Ca2+]i increases in Jurkat cells was abolished (Figure S3). Likewise, uncaging of NPE-ADPR markedly induced Ca2+ entry in HEK 293 cells that overexpress TRPM2 (Figure S4) as compared to that in wildtype cells (Figure 3D). Taken together, these data indicate that uncaging of intracellular NPE-ADPR induces Ca2+ influx via TRPM2.

Uncaged Npe-Adpr Induction Of Mg2+ Influx

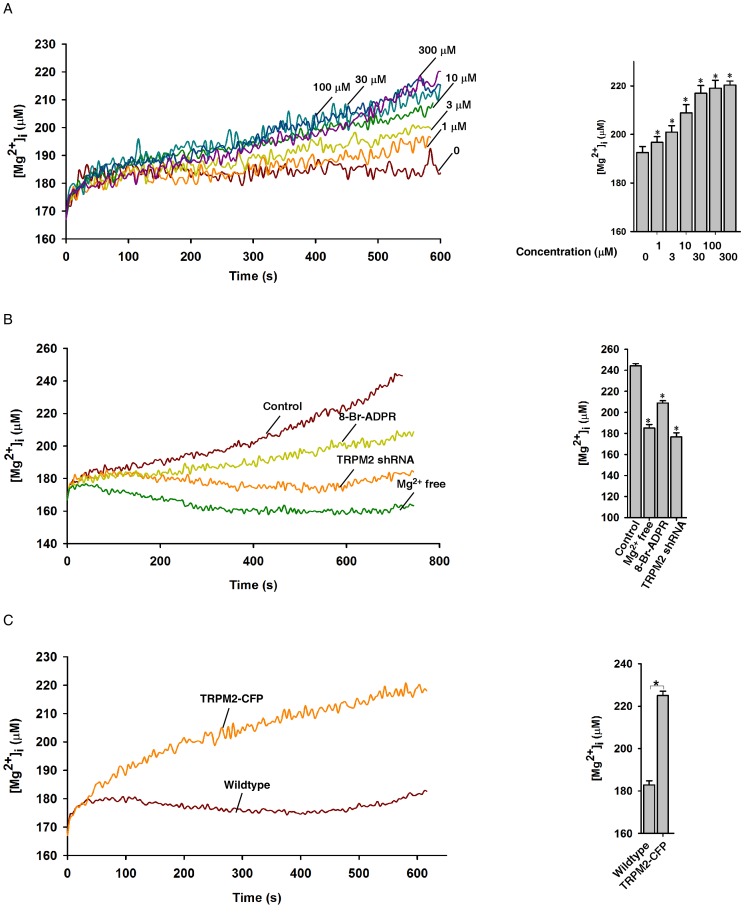

TRPM2 is a non-selective cation channel, and it has been shown previously that ADPR can stimulate Mg2+ influx via TRPM2 [40]. We therefore examined the ability of photolyzed NPE-ADPR to induce Mg2+ entry in Jurkat cells. Mag-Fura-2 AM was used to measure intracellular Mg2+ concentrations. As shown in Figure 4A, uncaging of NPE-ADPR induced intracellular Mg2+ increases in a concentration dependent manner in Jurkat cells. In addition, NPE-ADPR did not evoke any Mg2+ changes in Jurkat cells without UV uncaging, and UV illumination in the absence of NPE-ADPR also failed to induce Mg2+ (Figure S5). Moreover, removal of extracellular Mg2+, or treatment with 8-Br-ADPR, or knockdown of TRPM2 abolished the photolyzed NPE-ADPR-induced Mg2+ increases (Figure 4B). Likewise, uncaging of NPE-ADPR induced Mg2+ entry only in HEK 293 cells that overexpress TRPM2 but not in wildtype cells (Figure 4C). Notably, Mag-Fura-2 is insensitive to Ca2+ change, evidenced by the fact that anti-CD3 antibody, OKT3, markedly induced Ca2+ increases in Fura-2 loaded Jurkat cells, whereas it failed to induce any fluorescence changes on Maga-Fura-2 loaded cells (Figure S6). Thus, these data demonstrated that uncaging of NPE-ADPR induces Mg2+ entry via TRPM2.

Figure 4. Characterization of the NPE-ADPR induced Mg2+ influx.

(A) Uncaging of intracellular NPE-ADPR (30 µM) induced intracellular Mg2+ increases in a dose dependent manner in Mag-Fura-2 loaded human Jurkat cells in regular HBSS. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells loaded with buffer only. (B) Pretreatment of Jurkat cells with 8-Br-ADPR (100 µM), or knockdown of TRPM2, or removal of extracellular Mg2+ markedly inhibited uncaged NPE-ADPR (300 µM)-induced Mg2+ influx in Mag-Fura-2 loaded human Jurkat cells. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells without pretreatment. (C) Uncaging of NPE-ADPR (300 µM) induced Mg2+ influx in Mag-Fura-2 loaded HEK293 cells that transiently express TRPM2-CFP. Data quantifications of [Mg2+]i peak induced by drug treatment in (A), (B), and (C) were expressed as mean ± S.E., n = 30–40 cells. In (A), (B), and (C), after Mag-Fura-2 loaded cells were incubated with NPE-ADPR, extracellular NPE-ADPR was then removed before UV photolysis to start the Mg2+ measurement.

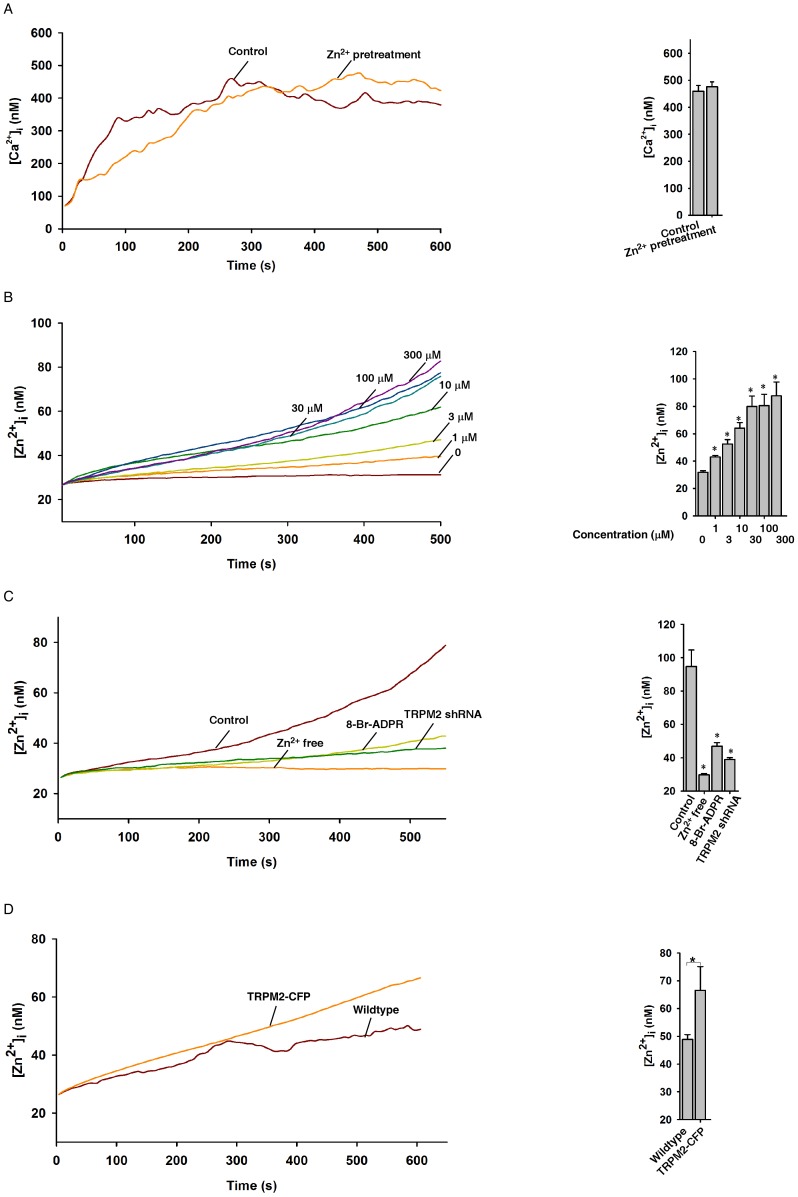

Uncaged Npe-Adpr Induction Of Zn2+ Influx

It has been previously shown that extracellular Zn2+ can inhibit ADPR-induced cation entry via TRPM2 [41]. However, we found that high concentrations of Zn2+ were toxic to both Jurkat and HEK 293 cells (data not shown). We therefore examined the effects of non-toxic concentrations of extracellular Zn2+ on TRPM2 in Jurkat cells. Surprisingly, extracellular Zn2+ at low concentrations had little effect on the ability of photolyzed NPE-ADPR to induce intracellular Ca2+ increases in Jurkat cells (Figures 5A).

Figure 5. Characterization of the NPE-ADPR induced Zn2+ influx.

(A) Pretreatment of Jurkat cells with Zn2+ did not affect the ability of the photolyzed NPE-ADPR (30 µM) to induce Ca2+ influx in Fluo-4 loaded human Jurkat cells. (B) Uncaging of intracellular NPE-ADPR induced intracellular Zn2+ increases in a concentration dependent manner in FluoZin-3 loaded human Jurkat cells. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells loaded with buffer only. (C) Pretreatment of FluoZin-3 loaded Jurkat cells with 8-Br-ADPR (100 µM), or knockdown of TRPM2, or removal of extracellular Zn2+ markedly inhibited uncaged NPE-ADPR (100 µM)-induced Zn2+ influx in FluoZin-3 loaded human Jurkat cells. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells without pretreatment. (D) Uncaging of NPE-ADPR induced Zn2+ influx in FluoZin-3 loaded HEK293 cells that transiently express TRPM2-CFP. Data quantifications of [Zn2+]i peak induced by drug treatment in (B), (C), and (D) were expressed as mean ± S.E., n = 30–40 cells. In (A), (B), (C), and (D), after Fluo-4 or FluoZin-3 loaded cells were incubated with NPE-ADPR, extracellular NPE-ADPR was then removed before UV photolysis to start Ca2+ or Zn2+ measurement.

We then examined whether photolyzed NPE-ADPR can directly induce Zn2+ influx via TRPM2 in Jurkat cells. The fluorescent intensity of FluoZin-3 loaded cells was used to indicate intracellular Zn2+ concentration. Interestingly, photolyzed NPE-ADPR induced intracellular Zn2+ increases in a dose dependent manner (Figure 5B), which was abolished by removal of extracellular Zn2+, pretreatment with 8-Br-ADPR, or knockdown of TRPM2 (Figure 5C). Not surprising, NPE-ADPR did not evoke any Zn2+ changes in Jurkat cells without UV uncaging, and UV illumination in the absence of NPE-ADPR also failed to induce Zn2+ (Figure S7). Consistently, uncaging of NPE-ADPR induced Zn2+ entry only in HEK 293 cells that overexpress TRPM2 but not in wildtype cells (Figure 5D). In summary, our data supported that uncaging of NPE-ADPR induces Zn2+ entry via TRPM2 as well.

The Effects Of Temperature And Ph On Npe-Adpr Induced Cation Entry

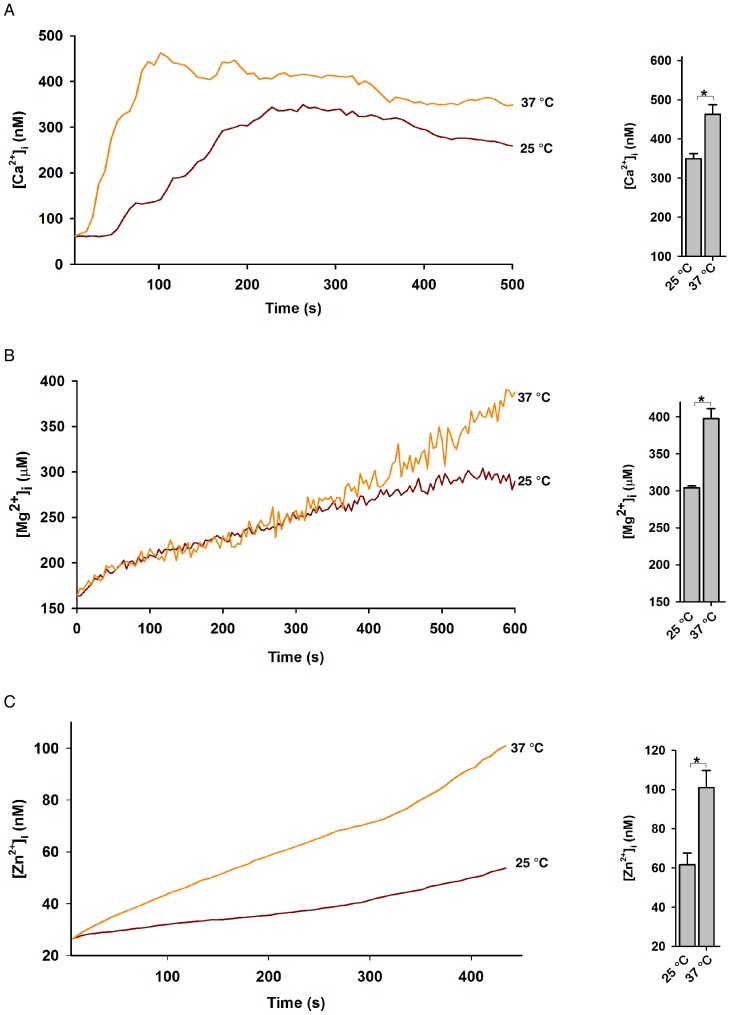

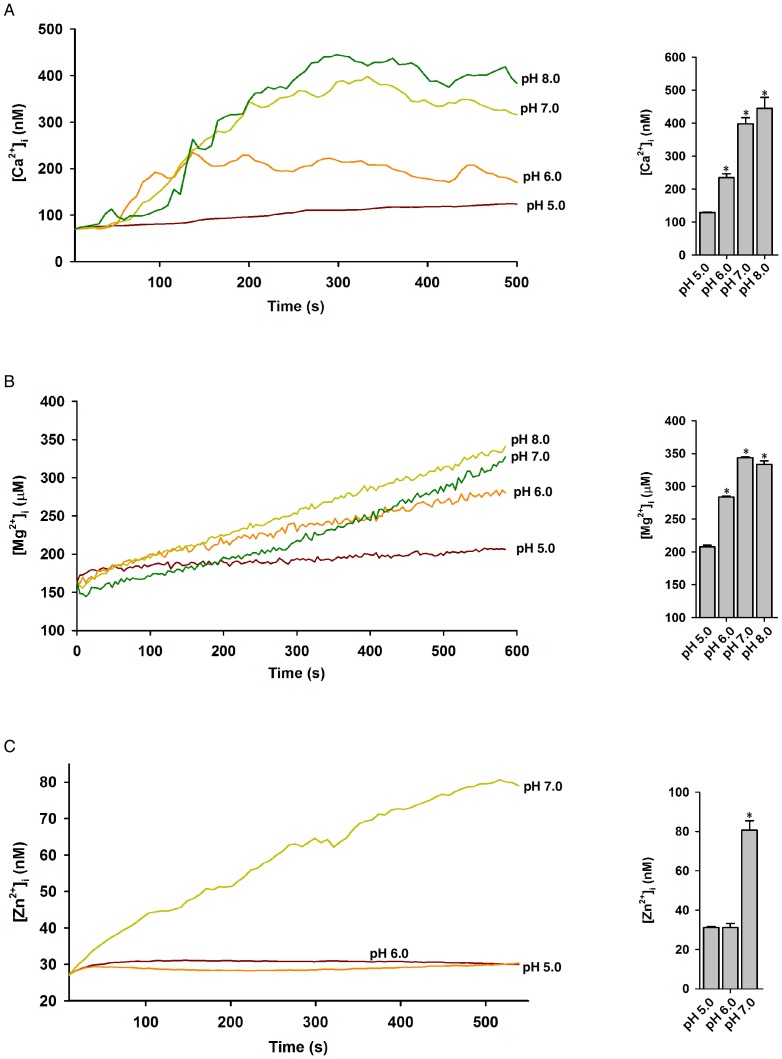

It has been previously reported that TRPM2 gating is modulated by pH and temperature [8],[31]–[35]. Indeed, we found that the abilities of photolyzed NPE-ADPR to induce the increases of intracellular Ca2+ (Figure 6A), Mg2+ (Figure 6B), or Zn2+ (Figure 6C) were much higher at 37°C than those at 25°C. Likewise, acidic pH (<7) markedly inhibited the photolyzed NPE-APDR from inducing the increases of intracellular Ca2+ (Figure 7A), Mg2+ (Figure 7B), and Zn2+ (Figure 7C) as compared to neutral (∼7) or alkaline (>8) pH in Jurkat cells. It is noteworthy that the photolyzed NPE-ADPR induced Ca2+ increase was higher in alkaline pH compared to that in neutral pH, which is most likely due to the fact that alkaline pH additionally inhibits SERCA to induce an intracellular Ca2+ rise [42]. Nevertheless, these data clearly indicated that temperature and pH modulate the gating of TRPM2 by ADPR.

Figure 6. The effect of temperature on cation entry in Jurkat cells after uncaging of NPE-ADPR.

(A), (B), and (C) The photolyzed NPE-ADPR (30 µM)-induced increases of intracellular Ca2+ (A), Mg2+ (B), and Zn2+ (C) were enhanced in high temperature in human Jurkat cells in regular HBSS. In (A), (B), and (C), after dye loaded cells were incubated with NPE-ADPR, extracellular NPE-ADPR was then removed before UV photolysis to start measurement. Data quantifications of peak induced by drug treatment in (A), (B), and (C) were expressed as mean ± S.E., n = 30–40 cells. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05.

Figure 7. The effect of pH on cation entry in Jurkat cells after uncaging of NPE-ADPR.

(A), (B), and (C) The photolyzed NPE-ADPR (30 µM)-induced increases of intracellular Ca2+ (A), Mg2+ (B), and Zn2+ (C) were inhibited by acidic pH in human Jurkat cells in regular HBSS. In (A), (B), and (C), after dye loaded cells were incubated with NPE-ADPR, extracellular NPE-ADPR was then removed before UV photolysis to start measurement. Data quantifications of peak induced by drug treatment in (A), (B), and (C) were expressed as mean ± S.E., n = 30–40 cells. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05, compared with cells incubated in pH 5.0.

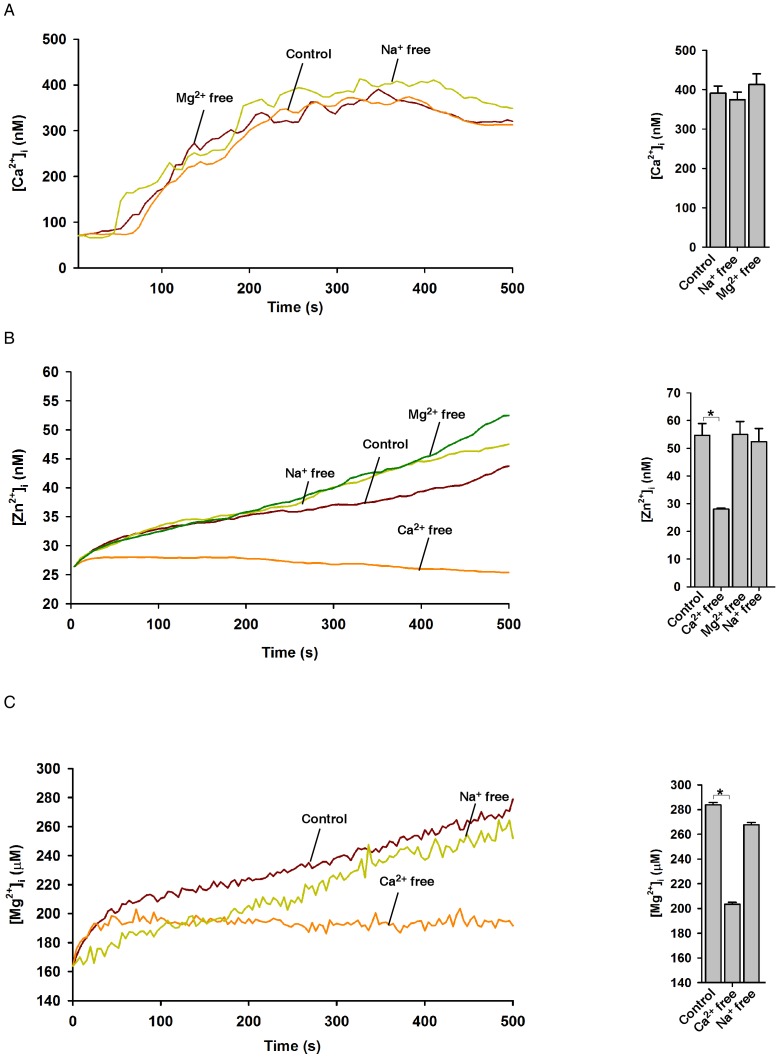

The Effects Of Extracellular Cations On Npe-Adpr Induced Cation Entry

Although ADPR is the primary activator for TRPM2 gating, intracellular Ca2+ was also implicated as an important modulator for TRPM2. We, therefore, examined the effects of varied extracellular cation compositions on photolyzed NPE-ADPR induced cation entry (Table 1). As shown in Figure 8A, the absence of extracellular Na+, Mg2+, or Zn2+ had no effect on photolyzed NPE-ADPR induced Ca2+ entry. On the other hand, the absence of extracellular Ca2+ not only abolished the induced Ca2+ influx (Figure 3A), but also markedly inhibited the induced Zn2+ (Figure 8B) or Mg2+ (Figure 8C) influx. The absence of extracellular Na+ or Mg2+ had no effect on the induced Zn2+ influx (Figure 8B), and the absence of extracellular Na+ also had no effects on induced Mg2+ influx (Figure 8C). In summary, these data indicated that extracellular Ca2+ is important for ADPR to activate TRPM2 for cation entry, possible by changing intracellular Ca2+ concentration via influx.

Table 1.

Composition of different test solutions (in mM).

| Solutions (A–L) | CaCl2 | MgCl2 | MgSO4 | KCl | KH2PO4 | NaHCO3 | NaCl | Na2HPO4 | ZnSO4 | NMDG-Cl1 | D-Glucose |

| A.Standard HBSS2 | 1.26 | 0.493 | 0.407 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0 | 0 | 5.56 |

| B. Ca2+ free HBSS3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0 | 0 | 5.56 |

| C. Mg2+ buffer4 | 1.26 | 0.493 | 0.407 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0 | 0 | 5.56 |

| D. Mg2+ free buffer5 | 2.16 | 0 | 0 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0 | 0 | 5.56 |

| E. Zn2+ buffer6 | 1.26 | 0.493 | 0.407 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0.03 | 0 | 5.56 |

| F. Zn2+ free buffer7 | 1.26 | 0.493 | 0.407 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0 | 0 | 5.56 |

| G. Ca2+ free buffer8 | 0 | 0.493 | 0.407 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0 | 0 | 5.56 |

| H. Ca2+ free buffer9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0.03 | 0 | 5.56 |

| I. Mg2+ free buffer10 | 2.16 | 0 | 0 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0 | 0 | 5.56 |

| J. Mg2+ free buffer11 | 2.16 | 0 | 0 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 4.17 | 137.93 | 0.338 | 0.03 | 0 | 5.56 |

| K. Na+ free buffer12 | 1.26 | 0.493 | 0.407 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 142.7 | 5.56 |

| L. Na+ free buffer13 | 1.26 | 0.493 | 0.407 | 5.33 | 0.441 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 142.7 | 5.56 |

: N-methyl-D-glucamine chloride;

: Invitrogen, 14025;

: Invitrogen, 14175;

: Mg2+ (+/−) buffer for magnesium measurement;

: Zn2+ (+/−) buffer for zinc measurement;

: Ca2+ (−) buffer for magnesium measurement;

: Ca2+ (−) buffer for zinc measurement;

: Mg2+ (−) buffer for calcium measurement;

: Mg2+ (−) buffer for zinc measurement;

: Na+ (−) buffer for calcium and magnesium measurement;

: Na+ (−) buffer for zinc measurement.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051028.t001

Figure 8. The effects of extracellular cations on NPE-ADPR induced cation entry in Jurkat cells.

(A) The effects of varied cation compositions on uncaged NPE-ADPR induced Ca2+ influx in Fluo-4 loaded human Jurkat cells. (B) The effects of varied cation compositions on uncaged NPE-ADPR induced Zn2+ influx in FluoZin-3 loaded human Jurkat cells. (C) The effects of varied cation compositions on uncaged NPE-ADPR induced Mg2+ influx in Mag-Fura-2 loaded human Jurkat cells. In (A), (B), and (C), extracellular NPE-ADPR was removed before UV photolysis to start Ca2+, Zn2+, or Mg2+ measurement. Data quantifications of peak induced by drug treatment in (A), (B), and (C) were expressed as mean ± S.E., n = 30–40 cells. The * symbols indicate the results of t Test analysis, p<0.05.

Discussion

Here we reported the synthesis and characterization of a NPE-caged ADPR. We found that the compound is permeable to Jurkat cells and HEK293 cells. Uncaging of intracellular NPE-ADPR induced the entry of multiple cations, including Ca2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+, via TRPM2. Thus NPE-ADPR is a useful cell permeant ADPR analogue and can be used to study the mechanisms of TRPM2-mediated cation entry.

NPE-ADPR is biologically inert before photolysis, suggesting that the phosphate groups are important for TRPM2 gating. Interestingly, the ester linkage between NPE and the phosphate is prone to UV photolysis, whereas the ether linkage between NPE and the hydroxyl group of ribose is relatively stable and resistant to UV photolysis (Figures 2A and 2B). These data indicated that ester bond has higher hydrolytic ability than ether bond under physiological condition. We speculate that the NPE group nearing the acidic phosphate could be easily protonated, thereby tending to be photolyzed more efficiently [43].

We showed in this study that attaching a cage group to the phosphate of ADPR can greatly increase its cell permeability (Figure S8), presumably because of the reduction of the charge of the phosphate as well as the increased lipophilicity contributed by NPE group. To minimize the leakage of the loaded NP-ADPR after washing, the photolysis was performed promptly after loading. Nevertheless, we observed a small Ca2+ increases in wildtype HEK293 cells lacking TRPM2 after photolysis (Figure 3E), which might be due to leakage of the probe and its activation of the P2Y1 receptor after photolysis. Indeed, treating cells with a P2Y1 inhibitor, suramin, can almost completely block the effects of extracellular uncaged NPE-ADPR on P2Y1 (Figures 3A and S3).

Interestingly, except Ca2+, neither Mg2+ nor Na+ had no significant effects on TRPM2 gating by ADPR. It has been shown previously that endogenous Ca2+ activates TRPM2 via its N-terminal calmodulin binding IQ-like motif possibly through calmodulin interaction [44],[45]. Thus, the effect of absence of extracellular Ca2+ on TRPM2 gating is likely due to the decrease intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Yet, it remains to be determined whether extracellular Ca2+ regulates some residues in the outer pore of TRPM2 for its activation.

Our results, in agreement with a patch clamp study [40], clearly demonstrated that ADPR can activate TRPM2 for Mg2+ influx. Mg2+ is one of the most abundant intracellular divalent cations and has been proposed to be able to serve as an intracellular second messenger, in addition to its well-known role of being a cofactor to ATP and a variety of enzymes [46]. Since a variety of stimuli can induce the generation of endogenous ADPR to incite intracellular Ca2+ increases via TRPM2 [11],[22]–[24],[47], these stimuli may well activate TRPM2 to cause not only Ca2+ influx but Mg2+ influx as well. In addition, TRPM2 mutants have been associated with several neurological diseases. These mutants led to decreases in Ca2+ influx [17]–[20]. In this regard, the role of Mg2+ in the neurological diseases associated with mutations in TRPM2 may well be worth re-examining [17]–[20]. The ease to monitor Mg2+ influx using NPE-ADPR as described in this study should facilitate this kind of investigations.

Likewise, the tool developed in this study should benefit investigations of the role of Zn2+ as an important regulator implicated in diverse cellular processes. Indeed, we show that uncaged NPE-ADPR can induce Zn2+ influx via TRPM2 in the presence of low concentration of extracellular Zn2+. Intracellularly, Zn2+ not only serves as an allosteric ion for transcription factors and metabolic enzymes, but also can modulate a variety of ion channels in a concentration dependent manner [48]–[50]. For example, TRPM3 and TRPM7 are both Zn2+ permeable [51],[52], while Zn2+ reversibly inhibits TRPM1 [53]. Similarly, high concentration of extracellular Zn2+ inhibited the ability of ADPR to activate TPRM2 for cation entry [41]. Here we showed that the absence or a low concentration of extracellular Zn2+ had no inhibitory or enhancive effects on TPRM2 gating. Future work is required to assess whether extracellular stimuli could change intracellular Zn2+ concentration via ADPR/TRPM2, and to determine the residues responsible for Zn2+ passage in TRPM2.

Materials And Methods

Chemistry

All of the chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma. The caged group 1-(2-nitrophenyl) diazoethane (compound 3) was first synthesized as described previously [54]. Next ADPR (compound 4, 50 mg, 0.089 mmol) dissolved in 3 mL ice-cold water was mixed with 3 mL 1-(2-nitrophenyl) diazoethane (compound 3) dissolved in diethyl ether. The resulting biphasic mixture was vigorously stirred at 4°C in darkness for 3 h, and subsequently the ether layer was drawn off. 3 mL diazoethane reagent treatment procedure was then repeated three more times. Finally, purification of the water layer was performed by HPLC on a C18 reversed phase column, eluting with a linear gradient of 0–30% CH3CN in water within 30 min. Four peaks were collected, and peak A gave rise to the light yellow solid compound 5 (15.2 mg, 24%). According to the 1H NMR spectrum, this caged structure represented a mixture of more than one mono-caged isomers (Figure 1A). They were all efficiently photolyzed into ADPR under UV flash as detected by HPLC analysis (Figure 2A). 1 H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ8.42, 8.17 (s, each 1 H), 8.0-7.0 (m, 4 H), 5.92 (d, 1 H, J = 4 Hz), 4.93 (m, 1 H), 4.56 (m, 1 H), 4.23-4.18 (m, 2 H), 4.07-3.97 (m, 4 H), 1.24 (d, 3 H, J = 8 Hz). 31P NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ-1.22, -2.04 ppm (Figures S1A and 1B). High resolution mass spectrometry (electrospray ionization, negative) for C23H30N6O16P2, calculated 707.1194 [M-1]−, found 707.1120.

In addition, peak D was collected and characterized as a caged structure containing five NPE groups (Figure 1A). 1 H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ8.40, 8.16 (s, each 1 H), 7.88-7.48 (m, 20 H), 5.92 (d, 1 H, J = 4 Hz), 5.11 (q, 5 H, J = 8 Hz), 4.93 (m, 1 H), 4.56 (m, 1 H), 4.27-4.23 (m, 2 H), 4.06-3.98 (m, 4 H), 1.37 (d, 15 H, J = 8 Hz). 31P NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ-11.03, -11.25 ppm.

8-Br-ADPR was synthesized and purified as described previously [38].

Cell Culture

The human Jurkat T-lymphocytes and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were both obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Jurkat cells were normally cultured in RPMI medium 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM Hepes buffer (pH 7.4) at 5% CO2 and 37°C. HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin at 5% CO2 and 37°C.

Transient Transfection

HEK293 cells were plated at a density of 3×105 cells/well in 6-well plates. On the next day, 2 hours before transfection, the medium was changed to an antibiotic-free medium. The pCI-CFP-hTRPM2 or empty vector pCI-CFP was then transfected into cells by Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen). 24 hours after transfection, the medium was changed to regular medium, and TRPM2-CFP or CFP positive cells were finally used for Ca2+, Zn2+, or Mg2+ measurement after another 24 hours.

Imaging Measurements

Imaging measurements were performed as described previously [42],[55],[56]. Jurkat cells (2×105 cells/well) or HEK293 cells (6×104 cells/well) were plated in 24-well plates coated with 100 or 10 µg/ml poly-L-lysine (Sigma, P6282) respectively and both were incubated in serum free medium at 37°C overnight for adherence. The adherent cells were incubated with 2 µM Fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen, F14201), or FluoZin-3 AM (Invitrogen, F24195), or Mag-Fura-2 (Invitrogen, M1292) in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) in darkness at 37°C. The cells were then washed with HBSS twice and incubated in 200 µL of different test solutions (A–L, Table 1). Thereafter, the cells were put on the stage of an Olympus inverted epifluorescence microscope and incubated with or without caged ADPR in the presence or absence suramin (# 574625, CalBiochem) for 60 min followed by UV (370 nm) flash for 1 s to photolyze the caged structure, which was repeated every 7 s during the measurement of fluorescence intensity at 480 nm for Fluo-4 and FluoZin-3 using a 20× objective. Images were collected by a CCD camera every 7 s and analyzed by the cell R imaging software. For Mag-Fura-2 measurements, fluorescence was measured using the same imaging system, operating in ratio mode with emission set at 510 nm and alternating excitation at 340 and 380 nm every 4 s. For the measurements under different temperatures, an incubation system (Olympus, MIU-IBC) was applied.

Data Analysis

In each measurement, intracellular concentration of calcium, zinc, or magnesium was calculated using the general formula, [Ca2+]i = Kd(F-F min)/(F max-F) (Kd = 345 nM), [Zn2+]i = Kd(F-F min)/(F max-F) (Kd = 15 nM), or [Mg2+]i = Kd(R-R min)/(R max-R) (Kd = 1.45 mM), respectively. K d is the dissociation constant for Ca2+ or Mg2+ or Zn2+ binding to the indicator, F is the fluorescence intensity with Fluo-4 or FluoZin-3, and R is the ratio between emission at 340 and 380 nm with Fura-2. For Fluo-4, F max was determined by exposing cells to 10 mM Ca2+ and 5 µM ionomycin, and F min was determined by the addition of 4 mM EGTA and 5 µM ionomycin to cells. For FluoZin-3, F max was determined by exposing cells to 1 mM Zn2+ and 20 µM pyrithion, and F min was determined by the addition of 50 µM TPEN (N, N, N′, N′-tetra- (2-picolyl) ethylenediamine) and 20 µM pyrithion to cells. For Mag-Fura-2, R max was determined by exposing cells to 30 mM Mg2+ and 5 µM ionomycin, and R min was determined by the addition of 10 mM EGTA and 5 µM ionomycin to cells. Significant differences of peak ion level between groups were determined by the Student's t test, in which * p<0.05 was validated to be significant.

Supporting Information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Rich Graeff and other members of Yue lab for advice about the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Research Grant Council (RGC) grants (HKU 784710M, HKU 782709M, HKU 785911M) and a National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC)/RGC grant from Hong Kong (N_HKU 737/09) and NSFC (20910094), and a Special Fellow Award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America (J.Y). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Sumoza-Toledo A, Penner R (2011) TRPM2: a multifunctional ion channel for calcium signalling. The Journal of physiology 589: 1515–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jiang LH, Yang W, Zou J, Beech DJ (2010) TRPM2 channel properties, functions and therapeutic potentials. Expert Opin Ther Targets 14: 973–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perraud AL, Schmitz C, Scharenberg AM (2003) TRPM2 Ca2+ permeable cation channels: from gene to biological function. Cell Calcium 33: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lange I, Yamamoto S, Partida-Sanchez S, Mori Y, Fleig A, et al. (2009) TRPM2 functions as a lysosomal Ca2+-release channel in beta cells. Sci Signal 2: ra23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sumoza-Toledo A, Penner R (2010) TRPM2: a multifunctional ion channel for calcium signalling. J Physiol 589: 1515–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Islam MS (2011) TRP channels of islets. Adv Exp Med Biol 704: 811–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scharenberg AM (2009) TRPM2 and pancreatic beta-cell responses to oxidative stress. Islets 1: 165–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Togashi K, Hara Y, Tominaga T, Higashi T, Konishi Y, et al. (2006) TRPM2 activation by cyclic ADP-ribose at body temperature is involved in insulin secretion. EMBO J 25: 1804–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Uchida K, Dezaki K, Damdindorj B, Inada H, Shiuchi T, et al. (2011) Lack of TRPM2 impaired insulin secretion and glucose metabolisms in mice. Diabetes 60: 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamamoto S, Shimizu S, Kiyonaka S, Takahashi N, Wajima T, et al. (2008) TRPM2-mediated Ca2+influx induces chemokine production in monocytes that aggravates inflammatory neutrophil infiltration. Nat Med 14: 738–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sumoza-Toledo A, Lange I, Cortado H, Bhagat H, Mori Y, et al. (2011) Dendritic cell maturation and chemotaxis is regulated by TRPM2-mediated lysosomal Ca2+ release. FASEB J 25: 3529–3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takahashi N, Kozai D, Kobayashi R, Ebert M, Mori Y Roles of TRPM2 in oxidative stress. Cell Calcium 50: 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perraud AL, Takanishi CL, Shen B, Kang S, Smith MK, et al. (2005) Accumulation of free ADP-ribose from mitochondria mediates oxidative stress-induced gating of TRPM2 cation channels. The Journal of biological chemistry 280: 6138–6148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takahashi N, Kozai D, Kobayashi R, Ebert M, Mori Y (2011) Roles of TRPM2 in oxidative stress. Cell Calcium 50: 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang KT, Chang WL, Yang PC, Chien CL, Lai MS, et al. (2006) Activation of the transient receptor potential M2 channel and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is involved in oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte death. Cell Death Differ 13: 1815–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kashio M, Sokabe T, Shintaku K, Uematsu T, Fukuta N, et al. (2012) Redox signal-mediated sensitization of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) to temperature affects macrophage functions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: 6745–6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xie YF, Macdonald JF, Jackson MF (2010) TRPM2, calcium and neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2: 95–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu C, Li PP, Cooke RG, Parikh SV, Wang K, et al. (2009) TRPM2 variants and bipolar disorder risk: confirmation in a family-based association study. Bipolar Disord 11: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu C, Macciardi F, Li PP, Yoon IS, Cooke RG, et al. (2006) Association of the putative susceptibility gene, transient receptor potential protein melastatin type 2, with bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 141B: 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hermosura MC, Cui AM, Go RC, Davenport B, Shetler CM, et al. (2008) Altered functional properties of a TRPM2 variant in Guamanian ALS and PD. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 18029–18034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perraud AL, Fleig A, Dunn CA, Bagley LA, Launay P, et al. (2001) ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature 411: 595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gasser A, Bruhn S, Guse AH (2006) Second messenger function of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate revealed by an improved enzymatic cycling assay. The Journal of biological chemistry 281: 16906–16913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Partida-Sanchez S, Gasser A, Fliegert R, Siebrands CC, Dammermann W, et al. (2007) Chemotaxis of mouse bone marrow neutrophils and dendritic cells is controlled by adp-ribose, the major product generated by the CD38 enzyme reaction. J Immunol 179: 7827–7839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heiner I, Eisfeld J, Warnstedt M, Radukina N, Jungling E, et al. (2006) Endogenous ADP-ribose enables calcium-regulated cation currents through TRPM2 channels in neutrophil granulocytes. The Biochemical journal 398: 225–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buelow B, Song Y, Scharenberg AM (2008) The Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase PARP-1 is required for oxidative stress-induced TRPM2 activation in lymphocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry 283: 24571–24583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abd Elmageed ZY, Naura AS, Errami Y, Zerfaoui M (2012) The poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs): new roles in intracellular transport. Cell Signal 24: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lange I, Penner R, Fleig A, Beck A (2008) Synergistic regulation of endogenous TRPM2 channels by adenine dinucleotides in primary human neutrophils. Cell calcium 44: 604–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sauve AA, Schramm VL (2004) SIR2: the biochemical mechanism of NAD(+)-dependent protein deacetylation and ADP-ribosyl enzyme intermediates. Curr Med Chem 11: 807–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grubisha O, Rafty LA, Takanishi CL, Xu X, Tong L, et al. (2006) Metabolite of SIR2 reaction modulates TRPM2 ion channel. The Journal of biological chemistry 281: 14057–14065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kolisek M, Beck A, Fleig A, Penner R (2005) Cyclic ADP-ribose and hydrogen peroxide synergize with ADP-ribose in the activation of TRPM2 channels. Mol Cell 18: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Starkus J, Beck A, Fleig A, Penner R (2007) Regulation of TRPM2 by extra- and intracellular calcium. J Gen Physiol 130: 427–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. M Naziroglu TRPM2 channel membrane currents in primary rat megakaryocytes were activated by the agonist ADP-ribose but not oxidative stress. J Membr Biol 241: 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Du J, Xie J, Yue L (2009) Modulation of TRPM2 by acidic pH and the underlying mechanisms for pH sensitivity. J Gen Physiol 134: 471–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang W, Zou J, Xia R, Vaal ML, Seymour VA, et al. (2010) State-dependent inhibition of TRPM2 channel by acidic pH. The Journal of biological chemistry 285: 30411–30418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Magnone M, Bauer I, Poggi A, Mannino E, Sturla L, et al. (2012) NAD+ Levels Control Ca2+ Store Replenishment and Mitogen-induced Increase of Cytosolic Ca2+ by Cyclic ADP-ribose-dependent TRPM2 Channel Gating in Human T Lymphocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry 287: 21067–21081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gustafsson AJ, Muraro L, Dahlberg C, Migaud M, Chevallier O, et al. (2011) ADP ribose is an endogenous ligand for the purinergic P2Y1 receptor. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 333: 8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. von Kugelgen I, Wetter A (2000) Molecular pharmacology of P2Y-receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 362: 310–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Partida-Sanchez S, Gasser A, Fliegert R, Siebrands CC, Dammermann W, et al. (2007) Chemotaxis of mouse bone marrow neutrophils and dendritic cells is controlled by adp-ribose, the major product generated by the CD38 enzyme reaction. Journal of immunology 179: 7827–7839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yu PL, Zhang ZH, Hao BX, Zhao YJ, Zhang LH, et al. (2012) A Novel Fluorescent Cell Membrane-permeable Caged Cyclic ADP-ribose Analogue. The Journal of biological chemistry 287: 24774–24783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xia R, Mei ZZ, Mao HJ, Yang W, Dong L, et al. (2008) Identification of pore residues engaged in determining divalent cationic permeation in transient receptor potential melastatin subtype channel 2. The Journal of biological chemistry 283: 27426–27432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang W, Manna PT, Zou J, Luo J, Beech DJ, et al. (2011) Zinc inactivates melastatin transient receptor potential 2 channels via the outer pore. The Journal of biological chemistry 286: 23789–23798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li S, Hao B, Lu Y, Yu P, Lee HC, et al. (2012) Intracellular Alkalinization Induces Cytosolic Ca Increases by Inhibiting Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca-ATPase (SERCA). PloS one 7: e31905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Walker JW, Reid GP, McCray JA, Trentham DR (1988) Photolabile 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl phosphate esters of adenine nucleotide analogs. Synthesis and mechanism of photolysis. Journal of the American Chemical Society 110: 7170–7177. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Du J, Xie J, Yue L (2009) Intracellular calcium activates TRPM2 and its alternative spliced isoforms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 7239–7244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tong Q, Zhang W, Conrad K, Mostoller K, Cheung JY, et al. (2006) Regulation of the transient receptor potential channel TRPM2 by the Ca2+ sensor calmodulin. The Journal of biological chemistry 281: 9076–9085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li FY, Chaigne-Delalande B, Kanellopoulou C, Davis JC, Matthews HF, et al. (2011) Second messenger role for Mg2+ revealed by human T-cell immunodeficiency. Nature 475: 471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gasser A, Glassmeier G, Fliegert R, Langhorst MF, Meinke S, et al. (2006) Activation of T cell calcium influx by the second messenger ADP-ribose. The Journal of biological chemistry 281: 2489–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Prasad AS (2009) Zinc: role in immunity, oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care 12: 646–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sensi SL, Paoletti P, Koh JY, Aizenman E, Bush AI, et al. (2011) The neurophysiology and pathology of brain zinc. J Neurosci 31: 16076–16085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Takeda A, Tamano H (2009) Insight into zinc signaling from dietary zinc deficiency. Brain research reviews 62: 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wagner TF, Drews A, Loch S, Mohr F, Philipp SE, et al. (2010) TRPM3 channels provide a regulated influx pathway for zinc in pancreatic beta cells. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology 460: 755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Monteilh-Zoller MK, Hermosura MC, Nadler MJ, Scharenberg AM, Penner R, et al. (2003) TRPM7 provides an ion channel mechanism for cellular entry of trace metal ions. The Journal of general physiology 121: 49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lambert S, Drews A, Rizun O, Wagner TF, Lis A, et al. (2011) Transient receptor potential melastatin 1 (TRPM1) is an ion-conducting plasma membrane channel inhibited by zinc ions. The Journal of biological chemistry 286: 12221–12233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Walker JW, Reid GP, Trentham DR (1989) Synthesis and properties of caged nucleotides. Methods Enzymol 172: 288–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wei WJ, Sun HY, Ting KY, Zhang LH, Lee HC, et al. (2012) Inhibition of Cardiomyocytes Differentiation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells by CD38/cADPR/Ca2+ Signaling Pathway. J Biol Chem 287: 35599–35611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yue J, Wei W, Lam CM, Zhao YJ, Dong M, et al. (2009) CD38/cADPR/Ca2+ pathway promotes cell proliferation and delays nerve growth factor-induced differentiation in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 284: 29335–29342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)