Abstract

This study sought to characterize the role of free radicals in regulating central and peripheral hemodynamics at rest and during exercise in patients with heart failure (HF). We examined cardiovascular responses to dynamic handgrip exercise (4, 8, and 12 kg at 1 Hz) following consumption of either a placebo or acute oral antioxidant cocktail (AOC) consisting of vitamin C, E, and α-lipoic acid in a balanced, crossover design. Central and peripheral hemodynamics, mean arterial pressure, cardiac index, systemic vascular resistance (SVR), brachial artery blood flow, and peripheral (arm) vascular resistance (PVR) were determined in 10 HF patients and 10 age-matched controls. Blood assays evaluated markers of oxidative stress and efficacy of the AOC. When compared with controls, patients with HF exhibited greater oxidative stress, measured by malondialdehyde (+36%), and evidence of endogenous antioxidant compensation, measured by greater superoxide dismutase activity (+83%). The AOC increased plasma ascorbate (+50%) in both the HF patients and controls, but significant systemic hemodynamic effects were only evident in the patients with HF, both at rest and throughout exercise. Specifically, the AOC reduced mean arterial pressure (−5%) and SVR (−12%) and increased cardiac index (+7%) at each workload. In contrast, peripherally, brachial artery blood flow and PVR (arm) were unchanged by the AOC. In conclusion, these data imply that SVR in patients with HF is, at least in part, mediated by oxidative stress. However, this finding does not appear to be the direct result of muscle-specific changes in PVR.

Keywords: systemic vascular resistance, peripheral vascular resistance, blood flow, antioxidants

in patients with heart failure (HF), activities of daily living and exercise capacity are often limited, resulting in decreased physical capacity and greater morbidity and mortality (31). In these patients it is often assumed that exercise capacity depends on the severity of cardiac dysfunction (43, 48), but ejection fraction and measures of left ventricular performance do not always correlate with exercise tolerance (16). These observations support the concept that the limited exercise capacity in HF patients may also result from a complicated pathophysiology in the periphery that includes alterations in skeletal muscle function (12), increased endothelin-1 (ET-1) production (34), decreased endothelial function (11), and augmented sympathoexcitation (6).

During exercise, blood flow to the working skeletal muscle increases primarily from an increase in cardiac output (CO) and the redistribution of blood flow, largely regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. The increased group III and IV muscle afferent nerve activity elicits a peripheral neural reflex, known as the “exercise-pressor reflex” (27), which contributes to an increase in blood pressure, heart rate (HR), and peripheral vasoconstriction during exercise (40). Together, these variables play an integral role in the regulation of blood flow to metabolically active and inactive vascular beds. Previous research has established that in animal models of HF (41) as well as in patients with HF (30), sympathetic nerve activity is not only higher at rest but even more exaggerated during exercise. Although the increased sympathetic nerve activity in HF is compensatory in nature; in the long term, it is likely detrimental to exercise capacity (29), with the true central and peripheral hemodynamic impact remaining unclear (15, 51).

Oxidative stress represents an imbalance between free radical production and endogenous antioxidant defenses and is known to be elevated in HF (19). Indeed, an increased concentration of free radicals, particularly superoxide, have been linked to peripheral hypoperfusion, peripheral endothelial dysfunction, and exaggerated sympathetic nerve activity in patients with HF (22), which are all likely contributors to exercise intolerance. A prior study, in an animal model of HF, revealed that decreasing free radicals by an arterial antioxidant infusion attenuated sympathetic nerve activity and mean arterial pressure (MAP) during muscle contraction (22). Interestingly, indexes of oxidative stress have been closely correlated with peak exercise oxygen consumption and the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification of HF patients (19, 28). However, the actual contribution of free radicals to hemodynamic control in patients with HF at rest and during exercise remains to be elucidated.

Consequently, with the use of rhythmic isometric handgrip exercise and an acute oral antioxidant cocktail (AOC), this study sought to better characterize the role of free radicals in the regulation of central and peripheral hemodynamics at rest and during exercise in patients with HF. We hypothesized that in contrast to controls, patients with HF will 1) exhibit evidence of elevated oxidative stress, 2) have exaggerated HR and MAP responses during handgrip exercise, 3) demonstrate an AOC-induced reduction in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) that will attenuate the exaggerated MAP and HR during handgrip exercise, and 4) experience a reduction in peripheral vascular resistance (PVR) in response to the AOC.

METHODS

Subjects.

A total of 20 male subjects (10 healthy controls and 10 NYHA class II and III HF patients) were recruited either by word of mouth or in the HF clinics at the University of Utah and the Salt Lake City VA Medical Center. The protocol was approved by these institutions, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All studies were performed in a thermoneutral environment at least 3 days apart, to allow for washout of the oral AOC, in a balanced crossover design. The healthy controls were normotensive (<140/90), not taking any prescription medication, and free of overt cardiovascular disease, as determined by health history questionnaire. Exclusion criteria for the healthy controls included subjects with diagnosed cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and hyptertension. Inclusion criteria for the patients with HF included NYHA classification of II and III and an ejection fraction of <35%. All of the subjects were nonsmokers and did not participate in any form of regular exercise. All subjects reported to the laboratory in a fasted state and without caffeine or alcohol use for 12 and 24 h, respectively. Additionally, subjects had not performed any exercise within the past 24 h, and if antioxidants and/or a multivitamin were part of a subject's daily routine, they were asked to refrain from these for at least 3 days before testing.

Handgrip exercise protocol.

Subjects were instrumented with a Finometer (Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) on the nonexercising arm to assess central hemodynamics and then rested supine for ∼20 min before baseline resting measurements of MAP, HR, stroke volume (SV), and CO. Ultrasound Doppler was used to assess resting brachial artery diameter and blood velocity. Handgrip maximal voluntary contraction was then determined (average of 3 maximal efforts) in the dominant arm. Rhythmic handgrip exercise (1 Hz) was performed at three workloads (4, 8, and 12 kg) using a commercially available handgrip dynamometer (TSD121C, Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA). The subjects squeezed the dynamometer to the sound of a digital metronome at 60 beats/min. A computer monitor was positioned so that the subjects could observe their force output and make corrections whenever necessary. Each exercise stage lasted 3 min to ensure the attainment of steady-state hemodynamics. Central hemodynamics, brachial artery diameter, and blood velocity were assessed continuously, but only the steady-state data (last 60 s) of each exercise stage were analyzed.

Central hemodynamic assessments.

Throughout the entire protocol HR, SV, CO, and MAP signals from the Finometer (Finapres Medical Systems) underwent analog-to-digital conversion and were simultaneously acquired (200 Hz) using commercially available data acquisition software (AcqKnowledge, Biopac Systems). SV was calculated using the Modelflow method, which includes age, sex, height, and weight in its algorithm (Beatscope version 1.1; Finapres Medical Systems) (3) and has been documented to accurately track CO during a variety of experimental protocols including exercise (8, 9, 42, 43a, 45) and in patients with both hypertension and vascular disease (4). CO was then calculated as the product of HR and SV. Cardiac index (CI) was calculated as CO/body surface area (in m2). SVR was calculated as MAP/CO.

Brachial artery assessments.

Brachial artery diameter and blood velocities were measured with ultrasound Doppler using a General Electric Logiq 7 ultrasound system (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). Angle-corrected and intensity-weighted mean velocities (Vmean) were determined using commercially available software (Logic 7). Using Vmean and arterial diameter, brachial artery blood flow was calculated as follows: blood flow = Vmeanπ(arterial diameter/2)2 × 60, where blood flow is expressed as milliliters per minute. Peripheral (arm) vascular resistance (PVR) was calculated as MAP/brachial artery blood flow.

Antioxidant supplementation.

On two separate visits to the laboratory, separated by a minimum of 3 days, subjects received either the AOC or placebo in a balanced, single blind design, though all analyses were performed by an individual blinded to both patient group and intervention. The supplements were administered 90 and 60 min before the handgrip protocol. A split dosing was used to improve absorbance and distribution of the antioxidants. The first antioxidant dose included vitamin E (200 IU), vitamin C (500 mg), and α-lipoic acid (300 mg), and the subsequent dose included water soluble vitamin E (400 IU), vitamin C (500 mg), and α-lipoic acid (300 mg). The placebo microcrystalline cellulose capsules, which were of similar taste, color, and appearance, were also consumed in two equivalently timed doses. The efficacy of this AOC to reduce plasma free radical concentration has been previously established using ex vivo spin trapping and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (36, 50).

Assays.

In both the placebo and antioxidant trials, blood samples were obtained from the antecubital vein before testing. Lipid peroxidation, a marker of oxidative stress, was assessed by quantifying plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) levels (Oxis Research/Percipio Bioscience, Foster City, CA). Antioxidant capacity was assessed by determining the ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP). Endogenous antioxidant activity, assessed by superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase activity, were assayed in the plasma (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) and the efficacy of the AOC to acutely raise plasma ascorbate levels in the blood was determined (CosmoBio, Carlsbad, CA). Plasma ET-1 concentration was also determined (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). A lipid panel and complete blood count were performed by standard clinical techniques.

Statistical analyses.

A two-by-two (intervention and group) repeated-measures ANOVA was used to determine whether the oxidative stress/antioxidant assays and baseline hemodynamic measures differed between groups and intervention. A two-by-three (intervention and exercise intensity) repeated-measure ANOVA was performed to identify changes in dependent variables within groups, drug condition, and across exercise intensities (SPSS 17.0, Chicago, IL). Tukey's honestly significant difference test was used for post hoc analysis when a significant main effect was identified. Statistical significance was established with α ≤ 0.05. All data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics.

Baseline characteristics of the healthy control subjects and HF patients are displayed in Table 1. Disease-specific characteristics and medications of the patients with HF are displayed in Table 2. The handgrip maximal voluntary contractions were similar between both the controls (35.4 ± 4.9 kg) and the HF patients (35.5 ± 4.2 kg). Therefore, the absolute workloads chosen (4, 8, and 12 kg) were also of similar relative intensities (∼11, ∼23, and ∼34%, respectively) for both groups.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Controls | HF | |

|---|---|---|

| Subjects, n | 10 | 10 |

| Age, yr | 60 ± 3 | 62 ± 2 |

| Weight, kg | 82 ± 3 | 96 ± 5* |

| Height, cm | 176 ± 2 | 178 ± 2 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26 ± 1 | 30 ± 1* |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 126 ± 4 | 114 ± 2* |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 80 ± 2 | 71 ± 3* |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 80 ± 5 | 134 ± 25 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 187 ± 9 | 151 ± 17 |

| High-density lipoprotein, mg/dl | 48 ± 2 | 40 ± 3* |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mg/dl | 129 ± 9 | 95 ± 13* |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 116 ± 16 | 109 ± 22 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 16 ± 1 | 15 ± 3 |

| Hematocrit, % | 47 ± 1 | 43 ± 2 |

| Red blood cells, M/μl | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2* |

| White blood cells, K/μl | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 7.7 ± 0.7* |

Values are means ± SE. HF, heart failure.

Significantly different from control.

Table 2.

Disease-specific characteristics and medications of the HF group

| HF | |

|---|---|

| Disease-specific characteristics | |

| Diagnosis (ischemic cardiomyopathy) | 7/10 |

| Diagnosis (nonischemic cardiomyopathy) | 3/10 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % (mean ± SE) | 26 ± 3 |

| NYHA class II | 7 |

| NYHA class III | 3 |

| Diabetic, number of all cases | 3/10 |

| Medications, number of all cases | |

| β-Blocker | 9/10 |

| ACE inhibitor | 6/10 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 2/10 |

| Statin | 9/10 |

| Diuretic | 7/10 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 0/10 |

| α-Blocker | 0/10 |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Assays.

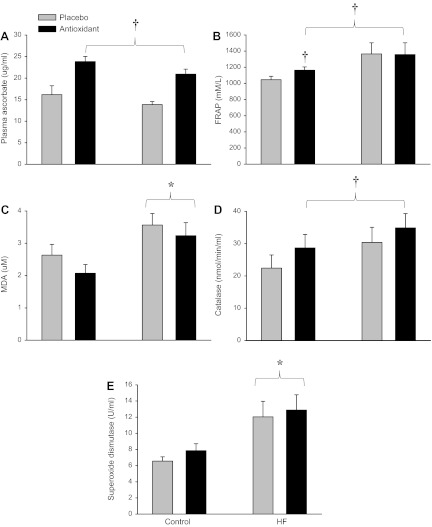

The AOC significantly elevated plasma ascorbate concentration by ∼50% in both the HF patients and in the controls 2 h after the ingestion of the first AOC dose (Fig. 1A). The AOC also significantly increased antioxidant capacity, as measured by FRAP, in the control group, whereas the HF patients tended to already have greater antioxidant capacity than the control group (P = 0.09) (Fig. 1B). MDA, a marker of lipid peroxidation and therefore oxidative stress, was significantly elevated in the patients with HF compared with the controls (Fig. 1C). Although not achieving statistical significance, the AOC lowered MDA by ∼21% in the controls and ∼9% in the patients with HF. Catalase activity was not different between the patients with HF and the controls but was increased in both groups following the AOC ingestion (Fig. 1D). SOD activity was ∼83% higher in the patients with HF compared with controls and was unaltered in either group by the AOC ingestion (Fig. 1E). Baseline ET-1 concentration (placebo) was significantly higher in the patients with HF (1.86 ± 0.2 pg/ml) compared with the controls (1.29 ± 0.2 pg/ml) with no effect of the AOC in either group.

Fig. 1.

Quantitative assessment of oxidative stress and antioxidant markers in healthy controls and patients with heart failure (HF). A: plasma ascorbate. B: ferric-reducing ability of plasma (FRAP). C: malondialdehyde (MDA). D: catalase. E: superoxide dismutase. Values are means ± SE. *Significantly different from controls; †significantly different from placebo.

Central hemodynamics.

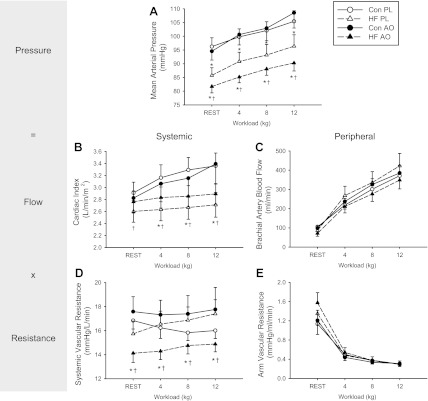

At rest in the placebo condition, MAP was significantly lower in the HF patients (86 ± 3 mmHg) compared with the controls (96 ± 3 mmHg) (P < 0.05), but there were no differences in HR, SV, or CO. Given the significant differences in body mass between the two groups, CO is represented as CI. During handgrip exercise the MAP following the placebo and AOC were both significantly lower in the HF patients at all workloads compared with controls (Fig. 2A). In the HF patients, ingestion of the AOC resulted in significantly lower MAP at rest (placebo, 86 ± 3 mmHg; and AOC, 82 ± 2 mmHg) and throughout all stages of handgrip exercise (∼6 mmHg at each workload) (Fig. 2A). This reduction in MAP was accompanied by nonsignificant increases in HR and SV, which resulted in a statistically significant increase in CI at all time points following ingestion of the AOC (Fig. 2B). In the placebo trial there were no significant differences in SVR between groups at rest or during handgrip exercise. However, in the HF patient group the AOC significantly reduced SVR at rest and throughout each stage of exercise by ∼12% (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Central and peripheral hemodynamic responses to handgrip exercise in HF (triangle) and control subjects (Con, circle) with placebo (PL, open symbols) and the antioxidant cocktail (AOC, closed symbols). Ohm's law is included to visually link these variables with this paradigm. Values are means ± SE for mean arterial pressure (A), cardiac output (B), brachial artery blood flow (C), systemic vascular resistance (D), and arm vascular resistance (E). *Significant difference between the controls and HF; †significant difference between PL and AOC.

Peripheral hemodynamics.

Resting brachial artery blood flows were not different between subject groups or treatments. During handgrip exercise, brachial artery blood flow increased with increasing workload, but there were no differences in blood flow between groups under any of the conditions (Fig. 2C). Similarly, there were no significant differences in arm PVR between groups or treatments (Fig. 2E). Brachial artery diameters were not different at rest either between groups or as a consequence of ingesting the AOC and again this observation held true during exercise.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to characterize the role of free radically mediated oxidative stress in regulating central and peripheral hemodynamics at rest and during exercise in patients with HF. In the current subjects, oxidative stress was confirmed to be significantly elevated in the HF patients, but increased activity of the endogenous antioxidant SOD suggested some degree of compensation. Although the ingestion of the AOC significantly increased plasma ascorbate concentration and endogenous antioxidant activity (catalase) in both the patients and controls, only in the patients with HF did this intervention result in a significant hemodynamic response. Specifically, at rest the AOC resulted in a significant reduction in SVR (−12%) that provoked a significant decrease in MAP (−5%) and an increase in CI (+7%) responses which were maintained throughout the three stages of handgrip exercise. The peripheral response to the AOC contrasted starkly with these changes, with no change in either arm blood flow or PVR. These data provide evidence that in HF patients, SVR is, at least in part, mediated by oxidative stress. However, this does not appear to be the result of limb or skeletal muscle-specific changes in PVR.

Oxidative stress and antioxidants in HF.

Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between free radical production and antioxidant defenses. Both human studies (19) and animal models (22) of HF suggest that oxidative stress is elevated in this disease population, and this excess free radical load has been implicated as contributing to many of the structural and functional changes, such as myocardial and ventricular remodeling and both contractile and endothelial dysfunction, that are characteristic of HF. Elevated levels of oxidative stress in the current patients with HF were confirmed by an elevation in MDA, a marker of lipid peroxidation, compared with controls (Fig. 1C). This is in agreement with prior work by Ellis et al. (13) who documented elevated thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, also an indicator of lipid peroxidation, in patients with HF. In terms of the endogenous antioxidant defense system in patients with HF, previous research has been quite inconsistent with studies reporting that activity was increased (10), decreased (23), or unchanged (28). In the present study the patients with HF exhibited ∼83% greater SOD activity and a tendency for greater catalase activity (Fig. 1, D and E). SOD is typically considered as the first line of defense against accumulating free radicals, and superoxide is the radical that is often linked to vascular dysfunction and exaggerated sympathetic nerve activity in HF patients (22). Although previous findings in terms of SOD activity in patients with HF have been inconsistent, the current data, revealing increased SOD activity, can be interpreted as evidence of a compensatory upregulation because of the concomitantly greater oxidative stress in these patients.

The efficacy of the AOC used in the current study has previously been documented by the clear reduction in blood-borne free radicals directly measured by ex vivo spin trapping and EPR spectroscopy (36, 50). Interestingly, although in the current study the AOC clearly raised antioxidant levels in both the patients with HF and controls (Fig. 1, A and B), MDA only tended to be lower in both the controls and patients with HF with this intervention. This is in agreement with the findings of Ellis et al. (13) who reported that whereas long-term vitamin C supplementation in HF patients had a significant effect on lipid peroxidation, as measured by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, short-term vitamin C infusion had no measurable effect on this footprint of oxidative stress. Additionally, although there was a main effect of the AOC on the assessment of antioxidant capacity, as measured by FRAP, post hoc analyses support the qualitative assessment (Fig. 1B) that this was driven by a change in the control group and not in the patients with HF. This is likely partially explained by the tendency (P = 0.09) for the patients with HF to already have a greater antioxidant capacity than the controls before ingesting the AOC, making the AOC-induced increase, an even smaller relative component of all the antioxidants assessed by the FRAP assay. Regardless, it is apparent from the systemic hemodynamic data that the AOC had a clear physiological impact in the patients with HF and not the controls, and this was likely due to greater initial levels of free radicals and oxidative stress in the patients.

Effect of HF on hemodynamic responses to exercise.

It is well accepted that in HF patients, sympathetic nerve activity is augmented at rest (24, 44) and often well related to morbidity and mortality (2, 6). During exercise, increased group III and IV muscle afferent nerve activity results in sympathoexcitation causing global vasoconstriction. This serves to increase CO and in conjunction with local vasodilation helps to shunt blood toward the working skeletal muscle. Sympathoexcitation during exercise is greater in patients with HF than healthy individuals (30). This exaggerated response appears to negatively impact exercise tolerance, which is likely a result of excessive PVR (30). Consequently, we hypothesized that in response to rhythmic isometric handgrip exercise, HF patients would exhibit exaggerated MAP and HR responses governed by the sympathetic nervous system. However, the HF patients in the current study had a significantly lower MAP at rest (86 ± 3 mmHg) compared with the controls (96 ± 3 mmHg), and despite having a relatively normal increase in MAP with each exercise workload (4, 8, and 12 kg), this baseline shift remained evident throughout exercise (Fig. 2A). This lower initial MAP can likely be attributed to the patient's pharmacological therapy, and it is possible that the exercise-induced response was minimal due to the relatively low workloads used in this study. However, we chose to maintain the patient's pharmacological therapy throughout the study to both minimize patient risk and better understand the challenges these patients face in the “real world” when their disease is optimally pharmacologically controlled.

In the current study, MAP in both the controls and HF patients rose above baseline with each exercise workload with a similar magnitude, but there was only a clear rise in CI in the controls, whereas the response appears to be blunted in the HF patients (Fig. 2B). This supports previous animal (18, 32) and human studies (7) that suggest in HF, the rise in MAP in response to the metaboreflex is achieved by a systemic increase in vascular resistance (SVR) compared with normal subjects who increase CO. It is well known that in health SV increases during exercise, but, in contrast, HF patients are unable to increase myocardial contractility, though not measured in the current study, which often leads to a slight decrease or attenuation in the SV response (5). The associated difficulty in increasing CO in HF and an impaired baroreflex buffering of the metaboreflex results in a rise in SVR (20). The current study documents that in response to handgrip exercise, there was a significant increase in SVR in the HF patients and a decrease in SVR in the controls (Fig. 2D), further suggesting that CO is no longer the primary mechanism mediating the pressor response in this patient population, and it is instead an increase in SVR. Interestingly, despite these differences in MAP and SVR responses, there were no such dissimilarities in brachial artery blood flow or PVR (arm) at rest or during handgrip exercise in the controls and the patients with HF (Fig. 2, C and E).

Oxidative stress and central hemodynamic responses to exercise.

Several large clinical trials have revealed that decreasing sympathetic activity in HF patients can actually improve mortality (33, 35), thus providing an important therapeutic target, particularly during exercise when this response has the potential to be more exaggerated. Given the growing evidence supporting the link between oxidative stress and HF, several studies using animal models of HF and an intra-arterial infusion of a SOD mimetic have revealed a reduction in sympathetic nerve activity (17) and therefore the exercise pressor response during muscle contraction (22, 46). As illustrated in Fig. 2, A, B, and D, ingestion of the oral AOC by the patients with HF in the current study resulted in significant central hemodynamic changes, which were evident both at rest and across all levels of handgrip exercise. These findings are consistent with the reduced blood pressure and sympathetic nerve activity documented in the previously discussed HF animal models (17, 22, 46). In a HF-induced rabbit model, supplementation with β-carotene, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), and α-tocopherol (vitamin E), a combination of antioxidants similar to those used in the current study, reduced tissue oxidative stress and attenuated the associated cardiac dysfunction, caused β-receptor downregulation, and reduced sympathetic nerve terminal abnormalities (37). Previous work by our group, (50) reported that this AOC significantly decreased free radical concentration, as assessed by EPR spectroscopy, and resulted in a fall in blood pressure in healthy older individuals that almost achieved statistical significance (P = 0.07). Also of interest is that despite the HF patients in the current study having higher baseline ET-1 concentrations, which is a contributor to increased SVR in HF patients (21), the AOC had no effect on ET-1 levels, suggesting that changes in ET-1 played a minimal role in the observed AOC-induced drop in SVR and MAP. Therefore, we were able to reveal that SVR in pharmacologically treated HF patients is partially mediated by oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress and peripheral hemodynamic responses to exercise.

Previous research in HF patients has reported that peripheral blood flow is reduced at rest (51) and during exercise (43, 48), contributing to the exercise intolerance that is a hallmark characteristic of the disease. Although there have been considerable variations in terms of the extent and potential mechanisms responsible for the attenuated peripheral blood flow in patients with HF because of methodological differences, exaggerated or inappropriate sympathoexcitation is likely a primary contributor (25, 26, 39, 51). We hypothesized that, as with the central hemodynamics, there would be an AOC-induced reduction in PVR (arm) during exercise, such that the potentially exaggerated MAP response in patients with HF patients would not occur. However, in the placebo condition, this group of patients with HF, using the submaximal handgrip exercise model, did not respond differently, in terms of peripheral hemodynamics, from the controls. In fact, there were no significant differences in PVR (arm) or brachial artery blood flow (Fig. 2, C and E) at rest or during exercise between the patients and controls, with or without the AOC. Our findings, under the placebo condition, are similar to previous studies by Shoemaker et al. (38) and Wiener et al. (47) who reported similarly attenuated MAP in patients with HF and also failed to see differences between the HF patients and controls in terms of forearm blood flow during a bout of handgrip exercise.

Given the AOC-induced fall in MAP and recognizing Ohm's law and how it relates to the human vascular system, either arm vascular resistance, brachial artery blood flow, or both would be expected to fall in this scenario. Although not statistically significant, there was such a trend in blood flow following ingestion of the AOC (Fig. 2C), but there was no such trend in arm vascular resistance (Fig. 2E). These results are similar to a recent study by Alves et al. (1) who also reported no change in arm vascular resistance and forearm blood flow following an acute intra-arterial infusion of vitamin C in patients with HF. Thus the impact of the AOC on peripheral hemodynamics at both rest and exercise are in stark contrast to the change in central hemodynamics, revealing that the central changes do not appear to be the result of alterations in arm or skeletal muscle-specific peripheral resistance.

Experimental considerations.

We recognize several limitations in our study. First, although the Finometer and the Modelflow method have been previously used successfully during a variety of experimental protocols, particularly when determining relative changes (9, 42, 45) and in patients with both hypertension and vascular disease (4), it does assume a functioning aorta and aortic valve. In the present study we did not measure aortic regurgitation or aortic transmural pressure. We also acknowledge that we did not directly measure free radicals in the present investigation but instead relied on assessments of oxidative stress. Thus, although the AOC used in this study has been previously reported to reduce free radicals, as measured by EPR spectroscopy (36, 50), the current findings are limited to the interaction between markers of oxidative stress and the central and peripheral hemodynamics. Additionally, as we chose not to remove our patient population from their current medications, we cannot rule out the possibility of a significant drug/AOC interaction.

Conclusion.

This study documents that in patients with HF, both at rest and during exercise, alterations in central but not peripheral hemodynamics are, at least partially, mediated by oxidative stress. These findings have the potential to guide future investigations targeting oxidative stress, exercise intolerance, and therefore disease progression in this population.

GRANTS

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P01-HL-091830 (to R. S. Richardson); the Veterans Affairs Merit Grants EG910R (to R. S. Richardson) and RR&D CDA2 E7560W (to J. McDaniel); and American Heart Association Grant 0835209N (to D. W. Wray).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.A.H.W., J.N.N., J.S., and R.S.R. conception and design of research; M.A.H.W., J.M., A.S.F., S.J.I., and J.Z. performed experiments; M.A.H.W., J.M., A.S.F., S.J.I., and J.Z. analyzed data; M.A.H.W., J.M., J.Z., J.S., D.W.W., and R.S.R. interpreted results of experiments; M.A.H.W. prepared figures; M.A.H.W. drafted manuscript; M.A.H.W., J.M., S.J.I., J.N.N., J.S., D.W.W., and R.S.R. edited and revised manuscript; M.A.H.W., J.M., A.S.F., S.J.I., J.N.N., J.S., D.W.W., and R.S.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the subjects for the time and effort in participating in this research study. We also thank Mary Beth Hagan (FNP) and Robin Waxman (APRN) from the Salt Lake City VA Medical Center Heart Failure and Heart Transplant clinic and Le Ann Stamos (RN, MS), Shirley Belleville (RN, BSN), and Kirk Volkman (NP) from the University of Utah Heart Failure and Heart Transplant clinic for invaluable help with subject recruitment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alves M, Dos Santos MR, Nobre TS, Martinez D, Pereira Barretto AC, Brum PC, Rondon MU, Middlekauff HR, Negrao CE. Mechanisms of blunted muscle vasodilation during peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation in heart failure patients. Hypertension 60: 669–676, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barretto AC, Santos AC, Munhoz R, Rondon MU, Franco FG, Trombetta IC, Roveda F, de Matos LN, Braga AM, Middlekauff HR, Negrao CE. Increased muscle sympathetic nerve activity predicts mortality in heart failure patients. Int J Cardiol 135: 302–307, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogert LW, van Lieshout JJ. Non-invasive pulsatile arterial pressure and stroke volume changes from the human finger. Exp Physiol 90: 437–446, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos WJ, Imholz BP, van Goudoever J, Wesseling KH, van Montfrans GA. The reliability of noninvasive continuous finger blood pressure measurement in patients with both hypertension and vascular disease. Am J Hypertens 5: 529–535, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Solal A, Logeart D, Guiti C, Dahan M, Gourgon R. Cardiac and peripheral responses to exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 20: 931–945, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohn JN, Levine TB, Olivari MT, Garberg V, Lura D, Francis GS, Simon AB, Rector T. Plasma norepinephrine as a guide to prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 311: 819–823, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crisafulli A, Salis E, Tocco F, Melis F, Milia R, Pittau G, Caria MA, Solinas R, Meloni L, Pagliaro P, Concu A. Impaired central hemodynamic response and exaggerated vasoconstriction during muscle metaboreflex activation in heart failure patients. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2988–H2996, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vaal J, De Wilde R, Van den Berg P, Schreuder J, Jansen J. Less invasive determination of cardiac output from the arterial pressure by aortic diameter-calibrated pulse contour. Br J Anaesth 95: 326–331, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Wilde R, Geerts B, Cui J, van den Berg P, Jansen J. Performance of three minimally invasive cardiac output monitoring systems. Anaesthesia 64: 762–769, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieterich S, Bieligk U, Beulich K, Hasenfuss G, Prestle J. Gene expression of antioxidative enzymes in the human heart: increased expression of catalase in the end-stage failing heart. Circulation 101: 33–39, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drexler H, Hayoz D, Munzel T, Hornig B, Just H, Brunner HR, Zelis R. Endothelial function in chronic congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 69: 1596–1601, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drexler H, Riede U, Munzel T, Konig H, Funke E, Just H. Alterations of skeletal muscle in chronic heart failure. Circulation 85: 1751–1759, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis GR, Anderson RA, Lang D, Blackman DJ, Morris RH, Morris-Thurgood J, McDowell IF, Jackson SK, Lewis MJ, Frenneaux MP. Neutrophil superoxide anion-generating capacity, endothelial function and oxidative stress in chronic heart failure: effects of short- and long-term vitamin C therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 36: 1474–1482, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esposito F, Mathieu-Costello O, Shabetai R, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Limited maximal exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: partitioning the contributors. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 1945–1954, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franciosa JA, Park M, Levine TB. Lack of correlation between exercise capacity and indexes of resting left ventricular performance in heart failure. Am J Cardiol 47: 33–39, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao L, Wang W, Li YL, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Superoxide mediates sympathoexcitation in heart failure: roles of angiotensin II and NAD(P)H oxidase. Circ Res 95: 937–944, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammond RL, Augustyniak RA, Rossi NF, Churchill PC, Lapanowski K, O′Leary DS. Heart failure alters the strength and mechanisms of the muscle metaboreflex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H818–H828, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keith M, Geranmayegan A, Sole MJ, Kurian R, Robinson A, Omran AS, Jeejeebhoy KN. Increased oxidative stress in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 31: 1352–1356, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JK, Sala-Mercado JA, Hammond RL, Rodriguez J, Scislo TJ, O'Leary DS. Attenuated arterial baroreflex buffering of muscle metaboreflex in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H2416–H2423, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiowski W, Sutsch G, Hunziker P, Muller P, Kim J, Oechslin E, Schmitt R, Jones R, Bertel O. Evidence for endothelin-1-mediated vasoconstriction in severe chronic heart failure. Lancet 346: 732–736, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koba S, Gao Z, Sinoway LI. Oxidative stress and the muscle reflex in heart failure. J Physiol 587: 5227–5237, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landmesser U, Spiekermann S, Dikalov S, Tatge H, Wilke R, Kohler C, Harrison DG, Hornig B, Drexler H. Vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure: role of xanthine-oxidase and extracellular superoxide dismutase. Circulation 106: 3073–3078, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leimbach WN, Jr, Wallin BG, Victor RG, Aylward PE, Sundlof G, Mark AL. Direct evidence from intraneural recordings for increased central sympathetic outflow in patients with heart failure. Circulation 73: 913–919, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeJemtel TH, Maskin CS, Lucido D, Chadwick BJ. Failure to augment maximal limb blood flow in response to one-leg vs. two-leg exercise in patients with severe heart failure. Circulation 74: 245–251, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Middlekauff HR, Nitzsche EU, Hoh CK, Hamilton MA, Fonarow GC, Hage A, Moriguchi JD. Exaggerated muscle mechanoreflex control of reflex renal vasoconstriction in heart failure. J Appl Physiol 90: 1714–1719, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell JH, Wildenthal K. Static (isometric) exercise and the heart: physiological and clinical considerations. Annu Rev Med 25: 369–381, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishiyama Y, Ikeda H, Haramaki N, Yoshida N, Imaizumi T. Oxidative stress is related to exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J 135: 115–120, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Notarius CF, Ando S, Rongen GA, Floras JS. Resting muscle sympathetic nerve activity and peak oxygen uptake in heart failure and normal subjects. Eur Heart J 20: 880–887, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Notarius CF, Atchison DJ, Floras JS. Impact of heart failure and exercise capacity on sympathetic response to handgrip exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H969–H976, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Wojdyla D, Leifer E, Clare RM, Ellis SJ, Fine LJ, Fleg JL, Zannad F, Keteyian SJ, Kitzman DW, Kraus WE, Rendall D, Pina IL, Cooper LS, Fiuzat M, Lee KL. Factors related to morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure with systolic dysfunction: the HF-ACTION predictive risk score model. Circ Heart Fail 5: 63–71, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Leary DS, Sala-Mercado JA, Augustyniak RA, Hammond RL, Rossi NF, Ansorge EJ. Impaired muscle metaboreflex-induced increases in ventricular function in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2612–H2618, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, Colucci WS, Fowler MB, Gilbert EM, Shusterman NH. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. N Engl J Med 334: 1349–1355, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker JD, Thiessen JJ. Increased endothelin-1 production in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1141–H1145, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Yusuf S, Pocock S. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet 362: 759–766, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson RS, Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Wray DW, Lawrenson L, Nishiyama S, Bailey DM. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: role of free radicals. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1516–H1522, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shite J, Qin F, Mao W, Kawai H, Stevens SY, Liang C. Antioxidant vitamins attenuate oxidative stress and cardiac dysfunction in tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 1734–1740, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoemaker JK, Naylor HL, Hogeman CS, Sinoway LI. Blood flow dynamics in heart failure. Circulation 99: 3002–3008, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silber DH, Sutliff G, Yang QX, Smith MB, Sinoway LI, Leuenberger UA. Altered mechanisms of sympathetic activation during rhythmic forearm exercise in heart failure. J Appl Physiol 84: 1551–1559, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinoway L, Prophet S, Gorman I, Mosher T, Shenberger J, Dolecki M, Briggs R, Zelis R. Muscle acidosis during static exercise is associated with calf vasoconstriction. J Appl Physiol 66: 429–436, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith SA, Mitchell JH, Naseem RH, Garry MG. Mechanoreflex mediates the exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in heart failure. Circulation 112: 2293–2300, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugawara J, Tanabe T, Miyachi M, Yamamoto K, Takahashi K, Iemitsu M, Otsuki T, Homma S, Maeda S, Ajisaka R. Non-invasive assessment of cardiac output during exercise in healthy young humans: comparison between Modelflow method and Doppler echocardiography method. Acta Physiol Scand 179: 361–366, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan MJ, Knight JD, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR. Relation between central and peripheral hemodynamics during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Muscle blood flow is reduced with maintenance of arterial perfusion pressure. Circulation 80: 769–781, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43a.Tam E, Azabji Kenfack M, Cautero M, Lador F, Antonutto G, di Prampero PE, Ferretti G, Capelli C. Correction of cardiac output obtained by Modelflow from finger pulse pressure profiles with a respiratory method in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 106: 371–376, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas JA, Marks BH. Plasma norepinephrine in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 41: 233–243, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Lieshout J, Toska K, van Lieshout E, Eriksen M, Walløe L, Wesseling K. Beat-to-beat noninvasive stroke volume from arterial pressure and Doppler ultrasound. Eur J Appl Physiol 90: 131–137, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang HJ, Pan YX, Wang WZ, Zucker IH, Wang W. NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle modulates the exercise pressor reflex. J Appl Physiol 107: 450–459, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiener DH, Fink LI, Maris J, Jones RA, Chance B, Wilson JR. Abnormal skeletal muscle bioenergetics during exercise in patients with heart failure: role of reduced muscle blood flow. Circulation 73: 1127–1136, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson JR, Martin JL, Schwartz D, Ferraro N. Exercise intolerance in patients with chronic heart failure: role of impaired nutritive flow to skeletal muscle. Circulation 69: 1079–1087, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wray DW, Uberoi A, Lawrenson L, Bailey DM, Richardson RS. Oral antioxidants and cardiovascular health in the exercise-trained and untrained elderly: a radically different outcome. Clin Sci (Lond) 116: 433–441, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zelis R, Longhurst J, Capone RJ, Mason DT. A comparison of regional blood flow and oxygen utilization during dynamic forearm exercise in normal subjects and patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 50: 137–143, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]