Abstract

Myocardial fibrillar collagen is considered an important determinant of increased ventricular stiffness in pressure-overload (PO)-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Chronic PO was created in feline right ventricles (RV) by pulmonary artery banding (PAB) to define the time course of changes in fibrillar collagen content after PO using a nonrodent model and to determine whether this time course was dependent on changes in fibroblast function. Total, soluble, and insoluble collagen (hydroxyproline), collagen volume fraction (CVF), and RV end-diastolic pressure were assessed 2 days and 1, 2, 4, and 10 wk following PAB. Fibroblast function was assessed by quantitating the product of postsynthetic processing, insoluble collagen, and levels of SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine), a protein that affects procollagen processing. RV hypertrophic growth was complete 2 wk after PAB. Changes in RV collagen content did not follow the same time course. Two weeks after PAB, there were elevations in total collagen (control RV: 8.84 ± 1.03 mg/g vs. 2-wk PAB: 11.50 ± 0.78 mg/g); however, increased insoluble fibrillar collagen, as measured by CVF, was not detected until 4 wk after PAB (control RV CVF: 1.39 ± 0.25% vs. 4-wk PAB: 4.18 ± 0.87%). RV end-diastolic pressure was unchanged at 2 wk, but increased until 4 wk after PAB. RV fibroblasts isolated after 2-wk PAB had no changes in either insoluble collagen or SPARC expression; however, increases in insoluble collagen and in levels of SPARC were detected in RV fibroblasts from 4-wk PAB. Therefore, the time course of PO-induced RV hypertrophy differs significantly from myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction. These temporal differences appear dependent on changes in fibroblast function.

Keywords: procollagen, SPARC, osteonectin, cardiac fibroblasts, fibrosis

chronic pressure-overload (PO) results in progressive myocardial remodeling (33). PO-induced changes in cardiomyocytes result in ventricular hypertrophy (13). PO-induced changes in cardiac fibroblasts result in myocardial fibrosis (13). However, despite the fact that increased load can alter both cardiomyocyte and fibroblast properties, the time course of PO-induced hypertrophic changes may differ significantly from that of fibrotic changes. For example, in rodent models in which an acute increase in load is applied, the hypertrophic response begins almost immediately and is completed rapidly (17, 27). By contrast, myocardial fibrosis is delayed and does not occur until after the hypertrophic process is essentially complete (12, 18).

Defining these temporal differences in the hypertrophic and fibrotic response to PO in a nonrodent relevant model is important in understanding the progression from compensated hypertrophy to decompensated heart failure. In addition, it is important to define the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the differences in these temporal responses, particularly those responsible for the time course of myocardial fibrosis. Collagen homeostasis can be altered by a number of mechanisms that include changes in procollagen synthesis, postsynthetic procollagen processing, posttranslational modification of collagen, and collagen degradation (25). Based on our laboratory's previous studies defining the importance of fibroblast-dependent postsynthetic procollagen processing, we chose to focus the present study specifically on the role that fibroblast-dependent postsynthetic procollagen processing plays in the temporal course of PO-induced myocardial fibrosis (3).

Accordingly, the purposes of the present study were to define the time course of changes in myocardial fibrillar collagen content after the imposition of PO using a large nonrodent model, and to determine whether this time course was dependent on changes in cardiac fibroblast function. Fibroblast function was assessed by quantitating the product of postsynthetic processing, insoluble fibrillar collagen, and by examining the abundance of SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine), a protein shown to affect postsynthetic procollagen processing (23). SPARC is a collagen-binding matricellular protein implicated in collagen deposition in PO myocardium (3). Mice lacking SPARC expression exhibit significantly less collagen accumulation in response to PO compared with wild-type mice. In these experiments, we used the pulmonary artery band (PAB) model in cats (10). This model has been shown to result in significant right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction (16, 20). However, the time course of changes in remodeling and fibrosis, the mechanisms that underlie these changes, and changes in fibroblast function have not been previously examined (17). This model provides a PO-induced hypertrophied RV and a same-animal normally loaded nonhypertrophied left ventricular (LV) control. Primary fibroblast cultures can be separately generated from the RVs and LVs, allowing analysis of PO RV fibroblasts along side same-animal control LV fibroblasts.

METHODS

Feline model of chronic PO.

Chronic PO of the RV was created by banding of the pulmonary artery (PAB), as previously described (21). This animal model has been used by our laboratories for more than 20 yr with consistent results in terms of hemodynamic response and appropriate hypertrophic growth of the RV (29). The LV of PAB cats were used as same-animal non-PO controls. To confirm that structural changes did not occur in the LV of PAB animals, serial echocardiograms were analyzed from four cats before PAB (baseline) and 2 and 4 wk after PAB. Echocardiography measurements showed that there were no significant changes in the LV end-diastolic dimension (EDD), LV mass, and LV fractional shortening (FS) after 2 or 4 wk of PAB compared with the baseline pre-PAB values. For example, 4 wk after PAB, LV EDD was 13 ± 1 vs. 14 ± 1 mm at baseline, LV FS was 39 ± 3 vs. 40 ± 7% at baseline, and LV mass was 8.2 ± 3.4 vs. 7.8 ± 1.7 g at baseline (means ± SE, all comparisons between 4 wk after PAB and pre-PAB baseline were not statistically significant).

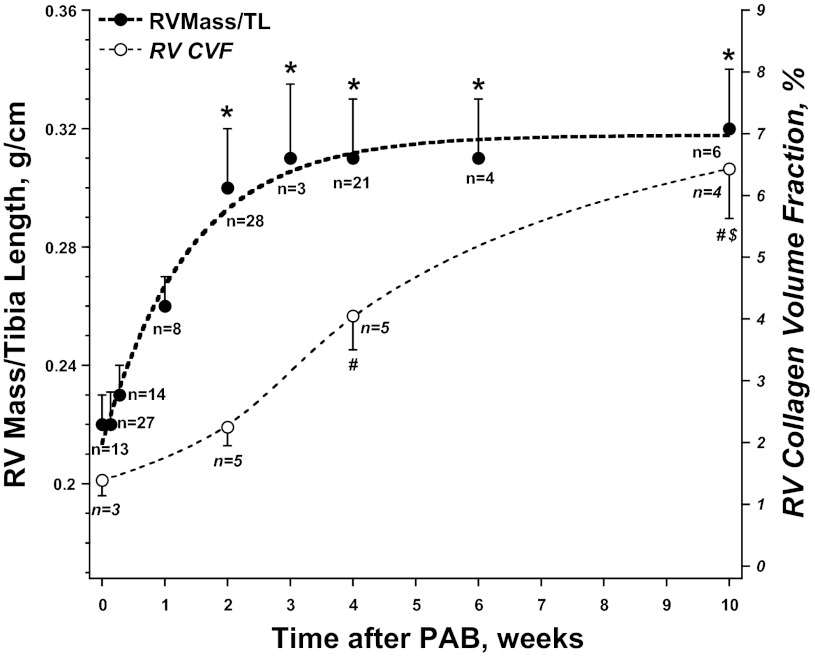

Male cats that had not undergone PAB were compared with male cats that had undergone PAB for 2 days and 1, 2, 4, and 10 wk. For Fig. 1, RV mass-to-tibia length ratios for 24 h and additional animals at later time points were generated as a result of additional studies performed by the authors of this study and were included for completeness and robustness of the time course (7, 8, 19). All procedures are in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines and approved by the IACUC at the Ralph H. Johnson Veteran's Administration Medical Center, Charleston, SC.

Fig. 1.

Time course of increase in right ventricle (RV) mass normalized to tibia length (TL) and collagen volume fraction (CVF) following placement of pulmonary artery band (PAB). The increase in RV mass was rapid and reached a plateau over 2 wk and then remained constant. By contrast, there was an increase in CVF that was delayed until 4 wk after PAB and then was progressive through 10 wk. Values are means ± SE; n, no. of animals contributing to each time point. *P < 0.05 vs. RV Mass/TL wk 1. #P < 0.05 vs. CVF 2 wk. $P < 0.05 vs. CVF 4 wk.

Hydroxyproline analysis.

Total, soluble, and insoluble myocardial collagen was quantified in the RV and LV free walls using hydroxyproline analysis, as previously described (3). Briefly, frozen LV and RV tissue was lyophilized, weighed (dry weight), pulverized, resuspended in 1 M NaCl with protease inhibitors, tumbled overnight at 4°C, and centrifuged. The supernatant then contained the “NaCl soluble” collagen (i.e., largely non-cross-linked collagen); the pellet contained the “NaCl insoluble” collagen (fully mature cross-linked fibrillar collagen). Each collagen fraction was processed separately. Collagen fractions underwent complete acid hydrolysis with 6 N HCl for 18 h at 120°C, and then each was neutralized to pH 7 with 4 N NaOH. One milliliter of chloramine T was added to 2-ml volumes of collagen sample and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. One milliliter of Ehrlich's reagent (60% perchloric acid, 15 ml 1-propanol, 3.75 g p-dimethyl-amino-benzaldehyde in 25 ml) was added, and samples were incubated at 60°C for 20 min. Absorbance at 558-nm wavelength was read on a spectrophotometer. Collagen was quantified as milligrams hydroxyproline per gram dry weight myocardium.

Histology.

Sections of the free wall of RVs and LVs were fixed in 10% formalin and stained with picrosirius red (PSR), as previously described (3). PSR is a fibrillar collagen-specific stain when viewed under polarized light. Images generated from polarized light microscopy were captured using a Leica microscope equipped with an ispot camera. Each section was evaluated for total area of stained collagen fibers [collagen volume fraction (CVF)] from at least five fields from three separate animals per time point using Sigmascan software, as described in Bradshaw et al. (3). Sections containing epicardium and/or large vessels were excluded from the analysis.

Fibroblast isolation and function.

RV and LV fibroblasts were cultured from normal, 2-wk PAB, and 4-wk PAB cats using previously published methods (24). RV and LV tissue from each animal was excised and incubated with Blendzyme 3 (Roche) for 2–3 h to liberate cells from myocardium (24). Digested tissue was triturated, washed three times in growth media [Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media (Gibco), 10% fetal calf serum (Cascade Biologics), and antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco)], and plated onto tissue culture dishes. Following 1 h at 37°C, nonadherent cells were removed, and adherent cells were cultured in growth media. These cultures are routinely found to be >95% fibroblastic in composition, as assessed by immunofluorescence of cell type-specific markers [vimentin (+), desmin (−), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor (−)]. Fibroblast cultures were used for the studies described below at passages 2–4.

Cardiac fibroblasts were plated at 5 × 105 per 100 mm2 in growth media with ascorbic acid to promote collagen production. Conditioned media and cell layers were collected at appropriate time points. Cell layers were rinsed in PBS and then recovered in 1% deoxycholate in 10 mM Tris pH 7.4 with protease inhibitors (Roche) and tumbled overnight at 4°C. Soluble cell layers were separated from insoluble cell layers by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 15 min. Total protein in detergent soluble cell layers was assessed by bicinchoninic acid assays to confirm equal loading of protein in insoluble fractions. Levels of collagen in soluble and insoluble cell layers were assessed by Western blot analysis, as previously described (24). Amounts of insoluble collagen from RV fibroblasts were normalized to that of LV fibroblasts from the same animals. Three separate primary fibroblast isolations were carried out for each time point.

SPARC abundance.

Immunoblot analysis of myocardial proteins extracted from myocardial samples with 2.5% SDS was performed by transfer of separated proteins to nitrocellulose and detection with anti-SPARC antibodies [OSN4–2; Takara (Clonetech), Mountain View, CA]. Chemiluminescence was used to detect secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. SPARC (osteonectin/BM40) protein was similarly detected using anti-SPARC monoclonal antibodies in fibroblast primary cultures.

Statistical analysis.

Temporal changes in myocardial structure and function, hydroxyproline, CVF, and fibroblast function were compared between the non-PO control and PO groups using a one-way ANOVA; pairwise comparisons were made using the Bonferroni test to adjust for multiple comparisons. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Results are presented as means ± SE in the figures. Results in Table 1 are presented as means ± SD. The authors had full access to the data and take full responsibility for its integrity.

Table 1.

Structural and hemodynamic assessment

| PAB |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 2 days | 1 wk | 2 wk | 4 wk | 10 wk | |

| n | 6 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 7 |

| Body weight, kg | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.1 |

| LV weight, g | 7.6 ± 1.2 | 9.8 ± 1.3 | 8.4 ± 1.6 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 8.5 ± 0.9 | 9.3 ± 0.6 |

| RV weight, g | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.3* | 3.7 ± 0.4* | 3.7 ± 0.2* |

| LV/BW, g/kg | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| RV/BW, g/kg | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.09 | 0.88 ± 0.10 | 0.97 ± 0.11* | 0.98 ± 0.08* | 0.89 ± 0.05* |

| RV/TL, g/cm | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.02* | 0.31 ± 0.02* | 0.35 ± 0.02* |

| Aortic SP, mmHg | 124 ± 27 | 127 ± 30 | 124 ± 32 | 123 ± 25 | 129 ± 26 | 128 ± 26 |

| RV SP, mmHg | 30 ± 2 | 44 ± 4* | 56 ± 9* | 56 ± 3* | 78 ± 7* | 80 ± 6* |

| RV EDP, mmHg | 5 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 7 ± 3 | 14 ± 3*# | 18 ± 3*# |

Values are averages ± SD; n, no. of animals. LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; BW, body weight; TL, tibia length; SP, systolic pressure; EDP, end-diastolic pressure; PAB, pulmonary artery band.

P < 0.05 vs. normal. #P < 0.05 vs. 2 wk after PAB.

RESULTS

PO-induced RV hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction.

The placement of the PAB resulted in an immediate RV PO, as evidenced by the increase in RV systolic pressure shown in Table 1. This RV PO resulted in a time-dependent increase in RV mass. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1, RV mass-to-tibia length ratio increased rapidly over the initial 2 wk and reached a plateau at 2 wk that remained relatively constant through 10 wk. RV end-diastolic pressure was unchanged through 2 wk after PAB; however, RV end-diastolic pressure was increased at 4 and 10 wk after PAB.

PAB caused no change in the hemodynamic load on the LV, no change in arterial pressure, and no change in LV mass (Table 1). In addition, echocardiography measurements showed that there were no significant changes in the LV EDD and no changes in LV FS after 2 or 4 wk of PAB compared with the baseline pre-PAB values (see methods).

PO-induced collagen content.

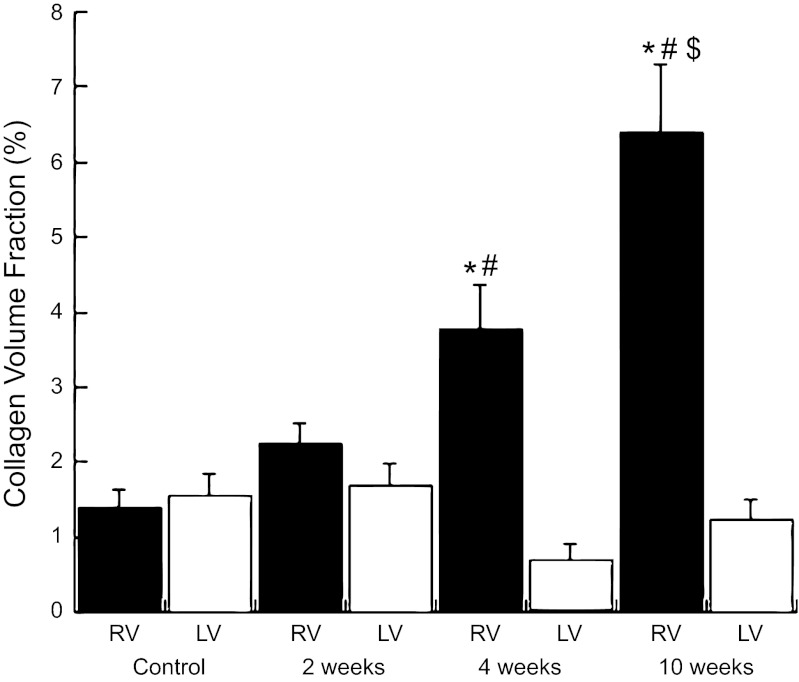

To determine the time course of changes in myocardial interstitial collagen content in the RV myocardium in response to PAB, myocardial collagen were quantified using two separate methods. Quantification of hydroxyproline was used to measure total collagen and soluble collagen (unprocessed procollagen or incompletely processed but non-cross-linked collagen) (Fig. 2). In addition, CVF was calculated from PSR-stained tissue sections (Figs. 3 and 4). The increase in CVF represented increases in the interstitial insoluble fibrillar collagen content.

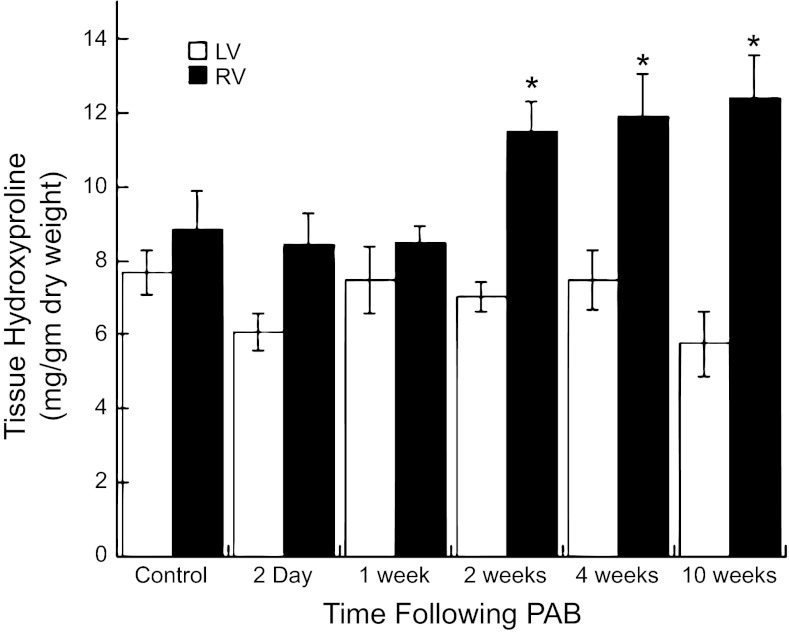

Fig. 2.

Quantification of levels of total hydroxyproline in RV and left ventricular (LV) tissue from control (n = 9) and PAB cats at 2 days (n = 6), 1 wk (n = 5), 2 wk (n = 11), 4 wk (n = 9), and 10 wk (n = 6) after banding is shown. A significant increase in amounts of total hydroxyproline was detected in 2, 4, and 10 wk in the RV samples from the PAB cats compared with both RV from the control cats and the LV from control and PAB cats. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. RV control.

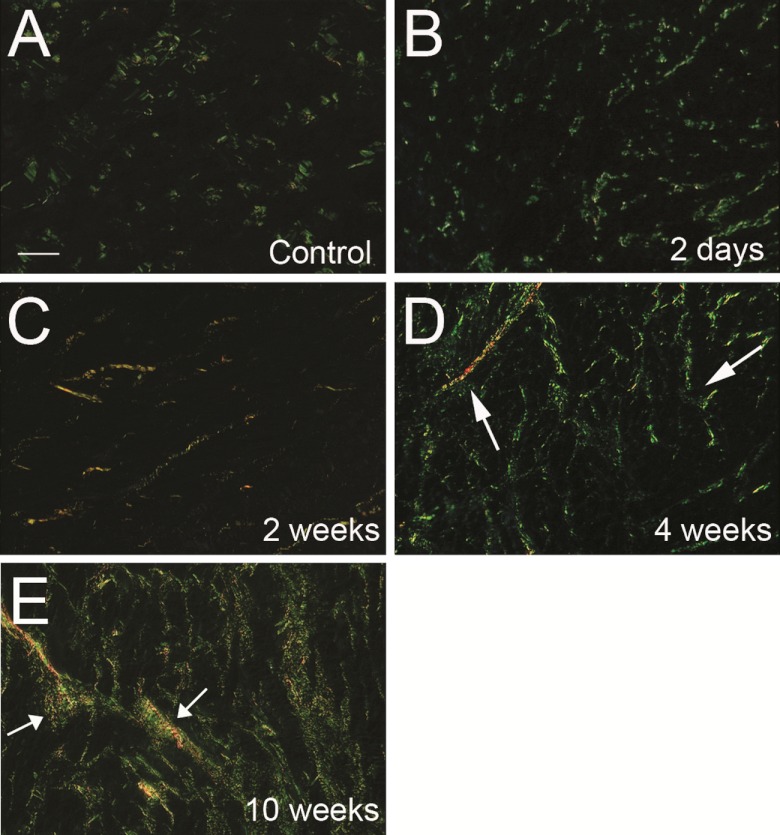

Fig. 3.

Insoluble fibrillar collagen fibers visualized with polarized light from picrosirius red (PSR)-stained tissue sections taken from the RV of control (A) and RV of cats with PAB for 2 days (B), 2 wk (C), 4 wk (D), and 10 wk (E). Interstitial insoluble fibrillar collagen fibers appeared green/yellow under polarized light, were composed of insoluble fully processed collagen, and were quantified as CVF. The quantity and distribution at 2 days (B) or 2 wk (C) after banding were not significantly changed compared with control RV (A). At 4 and 10 wk, an increase in volume fraction of collagen fibers was evident (white arrows, D and E). Thicker collagen fibers in D and E are indicated with white arrows. Bar = 50 μm.

Fig. 4.

Morphometric quantification of CVF from PSR-stained tissue sections. An increase in the CVF was noted at 4 and 10 wk after PAB. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. LV control. #P < 0.05 vs. RV 2 wk after PAB. $P < 0.05 vs. RV 4 wk after PAB.

Total RV hydroxyproline was not significantly changed in the RV of PAB cats after 2 days or 1 wk of PAB. By contrast, 2 and 4 wk after PAB, there were significant increases in total RV hydroxyproline compared with control cats or same-animal control LV of PAB cats (Fig. 2); total RV hydroxyproline was not significantly different between 2 and 4 wk.

The percentage of the total RV hydroxyproline that was soluble was 7.00 ± 1.86% in control and remained unchanged at 5.35 ± 1.16% after 2-wk PAB [P = nonsignificant (NS) vs. control RV]. However, 4 wk after PAB, the percentage of the total hydroxyproline that was soluble fell significantly to 3.27 ± 0.81% (P < 0.05 vs. control RV). Therefore, these data suggest that, while total collagen increased after 2 wk of PAB, the amount of insoluble collagen did not significantly change, whereas the amount of soluble collagen increased; by contrast, the increase in total collagen after 4 wk of PAB appeared to result from increases in insoluble collagen, with decreases in soluble collagen compared with both control and 2-wk PAB. Histological data presented below were concordant with these findings.

Representative PSR-stained histological examples of RV tissue from control cats, after 2 days, 2 wk, 4 wk, and 10 wk of PAB, are shown in Fig. 3. CVF was quantified in Fig. 4. CVF was not significantly altered in the RV 2 days or 2 wk after PAB compared with control cats (P = NS). However, after 4 and 10 wk of PAB, CVF increased significantly (P < 0.05), and collagen fibers appeared more robust in terms of numbers and thickness. Hence, CVF was unchanged at 2 wk, but increased at 4 and 10 wk after PAB.

Fibroblast function.

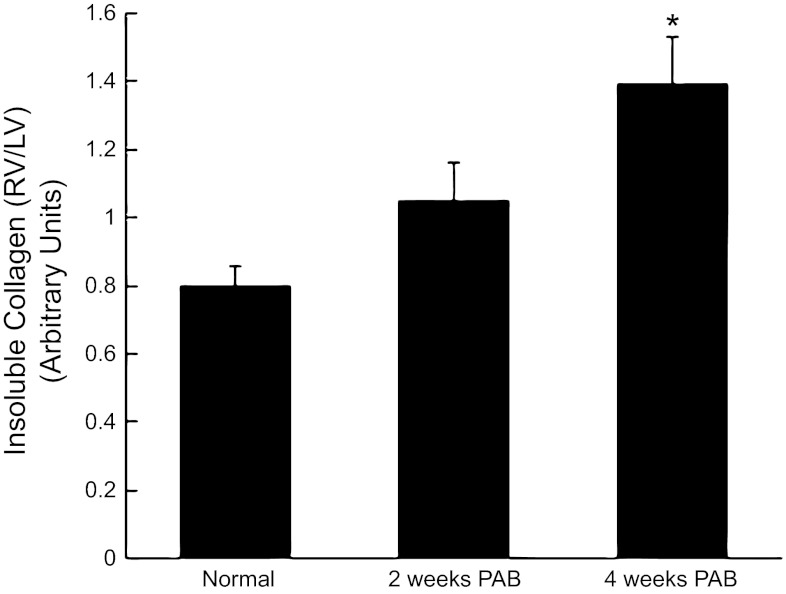

Deposition of insoluble collagen by primary fibroblast cultures was monitored to detect changes in postsynthetic procollagen processing by PAB vs. control fibroblasts. Changes in fibroblast function were measured by quantifying insoluble collagen deposition by RV fibroblasts normalized to same animal control LV fibroblasts (RV/LV, Fig. 5). Insoluble collagen content was not significantly altered in RV fibroblasts from 2-wk PAB [RV/LV collagen incorporation 1.00 ± 0.11 arbitrary units (AU)] compared with fibroblasts from normal cats (RV/LV = 0.80 ± 0.06 AU, P = NS). By contrast, insoluble collagen was significantly increased in cardiac fibroblasts isolated from 4-wk PAB vs. 2 wk and control cells (RV/LV = 1.40 ± 0.14 AU, P < 0.05 vs. control).

Fig. 5.

Insoluble collagen deposition by RV PAB fibroblasts from control and 2-wk and 4-wk PAB. Fibroblasts isolated from 4-wk PAB, but not 2-wk PAB, demonstrated significantly greater insoluble collagen deposition vs. control. Values from RV PAB fibroblasts were normalized to that of LV same-animal control for each experiment. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. control.

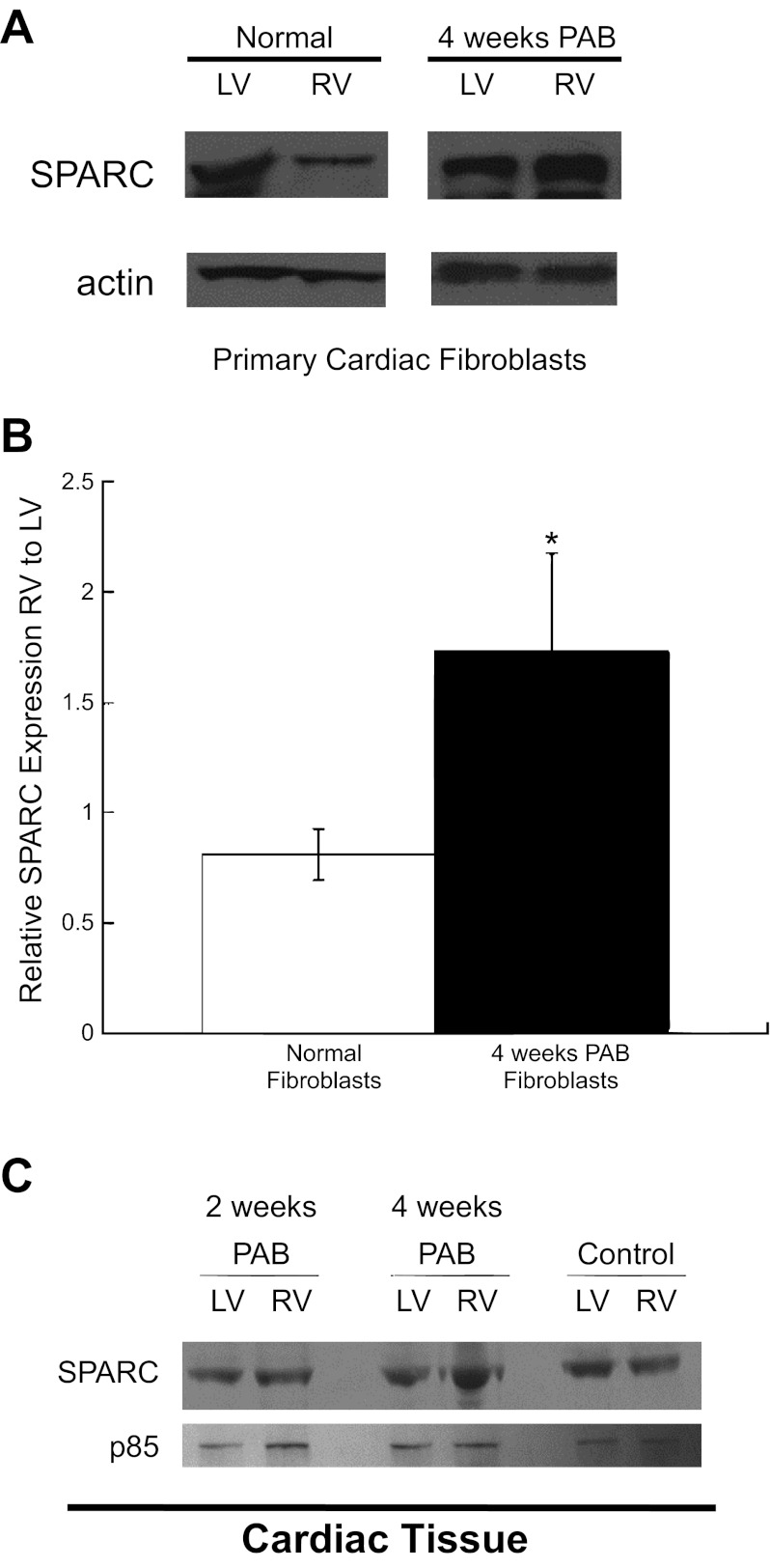

Levels of SPARC increased in 4-wk PAB RV fibroblast cultures compared with both LV fibroblasts from PAB cats and RV fibroblasts from control cats (Fig. 6, A and B). Similarly, in myocardial tissue samples, SPARC was increased in the RV from cats 4 wk after PAB compared with the LV from PAB cats and the RV and LV from control cats. Hence, increased levels of SPARC in RV fibroblasts and RV tissue from cats 4 wk after PAB were associated with increases in insoluble collagen deposition in vitro and in vivo. However, SPARC was not increased in the RV tissue from cats 2 wk after PAB at a time when soluble levels of collagen were not decreased and insoluble collagen was not increased (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that SPARC-dependent procollagen processing was not increased in RV fibroblasts of cats until 4 wk after PAB, a time at which there was a demonstrable change in fibroblast function.

Fig. 6.

A: representative Western blots of SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine) from fibroblast cultures. Actin is shown as loading control. Noncontiguous lanes from the same gel are shown. B: quantification of SPARC expression in RV fibroblasts normalized to levels in LV fibroblasts isolated from normal (open bars) and 4-wk PAB (solid bars) animals. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05. C: representative Western blots of SPARC expression in RV and LV myocardial tissue from 2-wk PAB, 4-wk PAB, and control animals. p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is shown as loading control. Fibroblast function, measured by quantifying SPARC abundance in primary fibroblast culture and RV myocardial tissue, was not significantly changed at 2 wk after PAB compared with control cats, but was significantly increased after 4 wk of PAB vs. control. Levels of SPARC were increased in 4-wk PAB RV fibroblasts (A and B) and in PAB RV myocardial tissue (C) vs. control fibroblasts and tissue.

DISCUSSION

Data from the present study support two important conclusions. First, there is a significant temporal difference in the development of the hypertrophic vs. fibrotic response to chronic PO. The hypertrophic response is rapid and complete within ∼2 wk of creation of the PO. By contrast, the fibrotic response is delayed, does not begin until the hypertrophic response is nearly complete, and is progressive after ∼4 wk of PO. Second, the mechanisms underlying this temporal difference include a change in fibroblast function, specifically, a change in fibroblast-dependent postsynthetic procollagen processing. Early in the course of PO (after 2 wk), total collagen was increased, soluble collagen was increased, but insoluble collagen, as measured by CVF, was not changed. These data suggested that procollagen synthesis was increased, but procollagen processing to mature insoluble fibrillar collagen was not. In addition, one matricellular protein critical to procollagen processing, SPARC, was also not changed after 2 wk of PO. Finally, in vitro fibroblast studies showed that insoluble collagen was unchanged in primary fibroblast cultures taken from RV after 2 wk of PO. By contrast, after 4 wk of PO, insoluble collagen and SPARC abundance were increased, but soluble collagen was decreased. Moreover, insoluble collagen in primary fibroblast cultures taken from the RV after 4 wk of PO was increased. These data support the hypothesis that the delayed fibrotic response to PO was caused, at least in part, by a temporal change in fibroblast-dependent postsynthetic procollagen processing.

PO induced by PAB results in a RV hypertrophy. The majority of animal and clinical studies carried out to date have focused on LV PO hypertrophy. PO whether RV or LV, results in chamber hypertrophy, hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes, increased CVFs, and abnormal systolic and diastolic function (9, 10). However, there are notable differences between RV and LV, including myocyte cellular origin during development, disparate geometries, and differences in pressures under normal conditions (15). Thus differences in cellular response to PO might differ between ventricles. Urashima, et al. (30) recently compared responses in gene expression between RV and LV PO ventricles in a murine model. Although, in general, many common pathways of gene expression were activated in response to PO in each ventricle, some changes in gene expression unique to RV PO were found. Notably, similar changes in gene expression associated with extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, the focus of the present study, were found in both RV and LV PO hypertrophy (30).

Temporal patterns of collagen expression and deposition following hypertrophy have also been characterized in rodent models of PO. Generally, and in agreement with the present findings, hypertrophic growth was found to increase and, in most cases, level off, before accumulation of elevated levels of tissue collagen. For example, PO in rabbits generated a significant hypertrophic response at 2 days following PO, whereas increases in tissue collagen were not found until 2 wk of PO (18). Kuwahara et al. also reported hypertrophic growth in response to suprarenal aortic banding in rats that reached significant differences at 1 wk and continued to increase at 2 and 4 wk. However, the percentage of myocardial fibrosis was not significantly elevated until 2 wk and further elevated at 4 wk (17).

Increases in expression of mRNA encoding fibrillar collagens have been found shortly after induction of PO. In rats subjected to abdominal aortic banding, a sixfold increase in mRNA encoding collagen α1(I) was detected at 3 days PO that declined to control at 1 wk and remained constant through 8 wk of PO. However, no increases in levels of tissue collagen were evident at 1 wk and were first apparent at 4 wk of PO (6). Similarly, Villarreal and Dillmann (31) found, in thoracic banded rats, a heart weight-to-body weight ratio that was significantly increased at 3 days following PO that coincided with peak expression of mRNA encoding collagen I and III. Tissue levels of collagen were not measured in the latter study (31). Thus hypertrophic growth and increased levels of mRNA encoding fibrillar collagens appear to precede the accumulation of fibrillar collagen in hypertrophic hearts and suggested that mechanisms other than increases in transcription might contribute to increased CVF in PO hearts.

In support of this, Eleftheriades, et al. (12) reported that PO in juvenile rats induced a gradual hypertrophic response, but no increases in mRNAs encoding collagen α1(I) at 1 and 4 wk following PO. However, significant differences in tissue incorporation of collagen were detected in 4-wk hypertrophic ventricles (12). Previous studies showed that a majority of newly synthesized collagen protein was degraded before incorporation into the insoluble ECM in the heart (22). Hence, fibrillar collagen accumulation in the studies by Eleftheriades et al. (12) was attributed to significant decreases in rates of procollagen degradation that were shown in PO ventricles. Likewise, collagen content was not increased at 2 days following PO, but was increased at 2 wk in rabbits. Whereas mRNA encoding collagen I peaked at 2 days and decreased by 2 wk PO, newly synthesized procollagen that was degraded before ECM incorporation decreased from 50.7 to 26.8% in PO tissues (1). The conclusions from these studies were that mechanisms controlling mRNA synthesis, as well as postsynthetic processing of procollagen I, influence collagen deposition in response to PO hypertrophy. In support of this hypothesis, the results reported here demonstrated an increased capacity of 4-wk PAB fibroblasts to efficiently deposit collagen.

Recently, Stewart, et al. (28) analyzed differences in fibroblast function in cells from PO ventricles. In these studies, significant hypertrophic growth in response to abdominal aortic constriction in rats was detected at 1 wk and reached a plateau at 2 wk. CVF was elevated following 1 wk of PO relative to sham control and was further increased at 2 wk of PO. Differences in fibroblast proliferation and gel contraction were found in cells isolated from ventricles subjected to 1 wk and greater lengths of PO. Collagen production and deposition were not assessed in these studies (28).

SPARC, a collagen-binding protein that is increased in PO hypertrophy, is one protein postulated to increase the efficiency of collagen deposition to insoluble ECM (3, 4, 26). SPARC expression is frequently associated with fibrotic deposition of collagen (5). The hearts of SPARC-null mice were shown to have decreased amounts of insoluble collagen and exhibited decreased insoluble interstitial collagen accumulation in response to PO hypertrophy (3). Results from the present study, in which increased levels of SPARC were found to be expressed by 4-wk PAB fibroblasts and in 4-wk PAB ventricles, were consistent with a key function of SPARC in fibrillar collagen deposition in hypertrophic hearts. Increases in total collagen, as measured by hydroxyproline analysis in 2-wk PAB RV, were not reflected in increased CVF at 2 wk. Thus we hypothesize that the lack of significant increases in SPARC expression at 2 wk following banding resulted in no change in insoluble collagen incorporation, despite elevated levels of total collagen.

Whereas factors that regulate synthesis of collagen I mRNA in response to PO have been the subject of a number of studies, the mechanisms that control postsynthetic processing of procollagen to collagen in PO hypertrophic hearts are not well characterized (2, 6, 11, 12, 14, 31, 32). The results presented here demonstrate that collagen deposition by fibroblasts isolated from 4-wk PAB RV was increased compared with those from nonhypertrophic LV. Our interpretation of these results is that increased efficiency of collagen deposition into insoluble ECM is enhanced in hypertrophic vs. nonhypertrophic fibroblasts and parallels the increased collagen accumulation in vivo. Frequently, amounts of collagen in the conditioned media have been used to quantify collagen production by fibroblasts in vitro. Because the primary determinant of tissue properties mediated by collagen in vivo is governed by collagen incorporated into the insoluble ECM, our results would argue that an equally important, and often over looked measurement, is the amount of collagen deposited by fibroblasts into insoluble cell layers.

One limitation of this study is that the focus was placed on fibroblast function in terms of postsynthetic procollagen processing, which represents one mechanism by which fibrillar collagen and diastolic dysfunction might be regulated. The present study did not examine changes in collagen synthesis, posttranslational modification, or degradation. Nonetheless, these data support postsynthetic processing as being at least one contributing mechanism to increased collagen content in PO hearts.

These studies support the hypothesis that an important regulatory component of collagen accumulation in the cardiac interstitium occurs at the level of processing of procollagen I. Thus ECM proteins that regulate procollagen processing might prove to be valid targets for the development of pharmaceutical agents to diminish cardiac collagen accumulation.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs (M. R. Zile: 5101CX000415-02 and 5101BX000487-04 and A. D. Bradshaw: 1I01BX001385-01A1) and grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (PO1-HL-48788 to G. Cooper and M. R. Zile; RO1-HL-094517 to A. D. Bradshaw).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.F.B., G.C., M.R.Z., and A.D.B. conception and design of research; C.F.B., J.L., Y.Z., H.K., and A.D.B. performed experiments; C.F.B., J.L., Y.Z., H.K., M.R.Z., and A.D.B. analyzed data; C.F.B., G.C., M.R.Z., and A.D.B. interpreted results of experiments; C.F.B., M.R.Z., and A.D.B. prepared figures; C.F.B., M.R.Z., and A.D.B. drafted manuscript; C.F.B., G.C., M.R.Z., and A.D.B. edited and revised manuscript; C.F.B., J.L., Y.Z., H.K., M.R.Z., and A.D.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bishop JE, Rhodes S, Laurent GJ, Low RB, Stirewalt WS. Increased collagen synthesis and decreased collagen degradation in right ventricular hypertrophy induced by pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res 28: 1581–1585, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boluyt MO, O'Neill L, Meredith AL, Bing OH, Brooks WW, Conrad CH, Crow MT, Lakatta EG. Alterations in cardiac gene expression during the transition from stable hypertrophy to heart failure. Marked upregulation of genes encoding extracellular matrix components. Circ Res 75: 23–32, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bradshaw AD, Baicu CF, Rentz TJ, Van Laer AO, Boggs J, Lacy JM, Zile MR. Pressure overload-induced alterations in fibrillar collagen content and myocardial diastolic function: role of secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) in post-synthetic procollagen processing. Circulation 119: 269–280, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bradshaw AD, Sage EH. SPARC, a matricellular protein that functions in cellular differentiation and tissue response to injury. J Clin Invest 107: 1049–1054, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brekken RA, Sage EH. SPARC, a matricellular protein: at the crossroads of cell-matrix communication. Matrix Biol 19: 816–827, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chapman D, Weber KT, Eghbali M. Regulation of fibrillar collagen types I and III and basement membrane type IV collagen gene expression in pressure overloaded rat myocardium. Circ Res 67: 787–794, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng G, Kasiganesan H, Baicu CF, Wallenborn JG, Kuppuswamy D, Cooper GT. Cytoskeletal role in protection of the failing heart by beta-adrenergic blockade. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H675–H687, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chinnakkannu P, Samanna V, Cheng G, Ablonczy Z, Baicu CF, Bethard JR, Menick DR, Kuppuswamy D, Cooper GT. Site-specific microtubule-associated protein 4 dephosphorylation causes microtubule network densification in pressure overload cardiac hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 285: 21837–21848, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cooper GT. Basic determinants of myocardial hypertrophy: a review of molecular mechanisms. Annu Rev Med 48: 13–23, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cooper GT, Satava RM. A method for producing reversible long-term pressure overload of the cat right ventricle. J Appl Physiol 37: 762–764, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eghbali M, Weber KT. Collagen and the myocardium: fibrillar structure, biosynthesis and degradation in relation to hypertrophy and its regression. Mol Cell Biochem 96: 1–14, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eleftheriades EG, Durand JB, Ferguson AG, Engelmann GL, Jones SB, Samarel AM. Regulation of procollagen metabolism in the pressure-overloaded rat heart. J Clin Invest 91: 1113–1122, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gaasch WH, Delorey DE, St. John Sutton MG, Zile MR. Patterns of structural and functional remodeling of the left ventricle in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 102: 459–462, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grimm D, Kromer EP, Bocker W, Bruckschlegel G, Holmer SR, Riegger GA, Schunkert H. Regulation of extracellular matrix proteins in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy: effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition. J Hypertens 16: 1345–1355, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haddad F, Hunt SA, Rosenthal DN, Murphy DJ. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease. I. Anatomy, physiology, aging, and functional assessment of the right ventricle. Circulation 117: 1436–1448, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kent RL, Uboh CE, Thompson EW, Gordon SS, Marino TA, Hoober JK, Cooper GT. Biochemical and structural correlates in unloaded and reloaded cat myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 17: 153–165, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuwahara F, Kai H, Tokuda K, Kai M, Takeshita A, Egashira K, Imaizumi T. Transforming growth factor-beta function blocking prevents myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in pressure-overloaded rats. Circulation 106: 130–135, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Low RB, Stirewalt WS, Hultgren P, Low ES, Starcher B. Changes in collagen and elastin in rabbit right-ventricular pressure overload. Biochem J 263: 709–713, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mani SK, Shiraishi H, Balasubramanian S, Yamane K, Chellaiah M, Cooper G, Banik N, Zile MR, Kuppuswamy D. In vivo administration of calpeptin attenuates calpain activation and cardiomyocyte loss in pressure-overloaded feline myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H314–H326, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marino TA, Houser SR, Cooper GT. Early morphological alterations of pressure-overloaded cat right ventricular myocardium. Anat Rec 207: 417–426, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marino TA, Kent RL, Uboh CE, Fernandez E, Thompson EW, Cooper GT. Structural analysis of pressure versus volume overload hypertrophy of cat right ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 249: H371–H379, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mays PK, McAnulty RJ, Campa JS, Laurent GJ. Age-related changes in collagen synthesis and degradation in rat tissues. Importance of degradation of newly synthesized collagen in regulating collagen production. Biochem J 276: 307–313, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCurdy S, Baicu CF, Heymans S, Bradshaw AD. Cardiac extracellular matrix remodeling: fibrillar collagens and secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC). J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 544–549, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poobalarahi F, Baicu CF, Bradshaw AD. Cardiac myofibroblasts differentiated in 3D culture exhibit distinct changes in collagen I production, processing, and matrix deposition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2924–H2932, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prockop DJ, Kivirikko KI. Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem 64: 403–434, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rentz TJ, Poobalarahi F, Bornstein P, Sage EH, Bradshaw AD. SPARC regulates processing of procollagen I and collagen fibrillogenesis in dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 282: 22062–22071, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roussel E, Gaudreau M, Plante E, Drolet MC, Breault C, Couet J, Arsenault M. Early responses of the left ventricle to pressure overload in Wistar rats. Life Sci 82: 265–272, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stewart JA, Jr, Massey EP, Fix C, Zhu J, Goldsmith EC, Carver W. Temporal alterations in cardiac fibroblast function following induction of pressure overload. Cell Tissue Res 340: 117–126, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tagawa H, Rozich JD, Tsutsui H, Narishige T, Kuppuswamy D, Sato H, McDermott PJ, Koide M, Cooper GT. Basis for increased microtubules in pressure-hypertrophied cardiocytes. Circulation 93: 1230–1243, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Urashima T, Zhao M, Wagner R, Fajardo G, Farahani S, Quertermous T, Bernstein D. Molecular and physiological characterization of RV remodeling in a murine model of pulmonary stenosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H1351–H1368, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Villarreal FJ, Dillmann WH. Cardiac hypertrophy-induced changes in mRNA levels for TGF-beta 1, fibronectin, and collagen. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H1861–H1866, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang CM, Kandaswamy V, Young D, Sen S. Changes in collagen phenotypes during progression and regression of cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 36: 236–245, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure–abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med 350: 1953–1959, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]