Abstract

Background

Over the past decade, practice standards have recommended that people suffering from both mental and substance use disorders receive integrated treatment. Yet, few institutions offer integrated services, and patients are too often turned away from psychiatric and addiction rehabilitation services.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify key factors in integrating services for patients with co-occurring disorders.

Methodology

We conducted a process evaluation with the aim of identifying factors that enhance or impede service integration. First, we elaborated a sound conceptual framework of service integration. We then conducted in-depth case studies analysis using socioanthropological methods (interviews with managers and professionals, focus groups with patients, nonparticipant observation, and document analysis). We analyzed two contrasted forms of services integration, a joint venture and a strategic alliance, separately and then compared them.

Findings

The integrations achieved in the two cases were of different intensities. However, from our study, we were able to identify various levers and characteristics that affect the development of an integrated approach. Reflecting on the dynamics of these two cases, we formulated six propositions to identify what matters when integrating services for persons with mental and substance use disorders.

Practice Implications

The integration of services transcends debates on care models and must be focused on the patients’ experience of care. The process should stimulate a learning experience that helps to align practices (normative integration) and to integrate teams and care. In this study, we identified a number of key conditions and levers for success.

Keywords: evaluation, implementation analysis, mental health, services integration, substance use

Patients with mental and substance use disorders mobilize numerous specialized resources (specialized health services, social services, judicial system, etc.) and make intensive use of health care services (Donald et al., 2005; Kedote, 2008; Rush et al., 2008). Few institutions offer specific services for patients with co-occurring disorders, and patients are still too often turned away from psychiatric and addiction rehabilitation services. Traditionally, the fields of substance abuse treatment and psychiatry have been profoundly isolated from each other, with separate histories and treatment philosophies (Brisson, 1988; Rush et al., 2008; SAMHSA, 2003). Recent professional guidelines have stated that co-occurring disorders were better addressed using an integrated approach that is more than a concurrent offer of services (Department-of-Health, 2002; Drake et al., 2001; HealthCanada, 2002; Mueser et al., 2003; SAMHSA, 2003). Integrated approaches refer to those where both mental and substance use disorders are treated simultaneously, taking into account the specificities of both problems (Donald et al., 2005). This blended approach should improve access to services and quality of care (Mueser et al., 2003; Drake et al., 2008). Nevertheless, it remains difficult to integrate services for this clientele—not so much because of disagreements about clinical practices but rather because of difficulties inherent to their organization (Ziedonis et al., 2005). Clearly, research is needed to better understand system integration, which has been little studied (Drake et al., 2001; Rush et al., 2008).

In fact, authors have recommended two ways to develop an integrated approach to treatment: creating one team by importing substance abuse treatment expertise into existing mental health services (co-optation) or forming new blended services (joint venture or merger; Mueser et al., 2003). However, previous experiences have shown that these may not necessarily be suitable for all types of clientele nor for several forms of health systems organization, in particular because of the required restructuring of human and financial resources (SAMHSA, 2003). Furthermore, a systematic literature review shows that the superiority of these propositions has not been not demonstrated because of the heterogeneity of studies (lack of standardization, absence of fidelity assessment, diversity of patients, varying lengths of intervention, diversity of outcomes, and inconsistency of measures in current research; Drake et al., 2008). Recent studies on models of care show that patients’ health seems to improve if they are treated in programs that provide specific services for co-occurring disorders (Grella & Stein, 2006), but they also underline the importance of adapting approaches to different types of conditions, as there is great heterogeneity in mental health diagnosis and substance consumptions (Tiet & Mausbach, 2007), which requires flexibility in the organization of care. Recent developments in better understanding models of services organization and their impact on patients’ health show that effectiveness seems not to be directly related to a particular model of care but rather to approaches that bridge the gap between the two types of services. Various models of services integration are therefore possible (Brousselle et al., 2007; Rush et al., 2008). However, less well known are the factors that facilitate services integration for patients with co-occurring disorders (Rush et al., 2008).

We analyzed the implementation process of two contrasted forms of integration, a joint venture and a strategic alliance. Using socioanthropological methods, we analyzed the integration process to identify factors that enhanced or impeded integration. In this article, we present our conceptual framework, the methodology used and the results for each form of integration. We then discuss key elements for integrating health services for people living with mental and substance use disorders.

Conceptual Framework

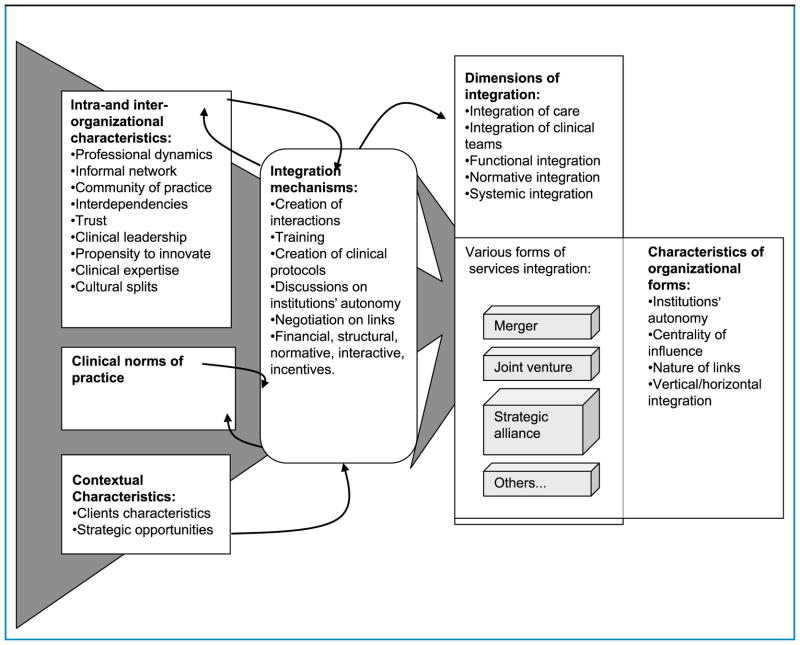

On the basis of the professional literature on co-occurring disorders and the organizational literature on services integration, we elaborated a conceptual framework for health services integration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for service integration

Conceptualizing Integration

The literature review showed that the form of integration is only one element characterizing the integration model. It may be described by the institutions’ autonomy, the centrality of influence (Lamarche et al., 2001), the nature of the organizations’ linkages (Markham & Lomas, 1995), and the verticality or horizontality of integration (Fleury, 2002; Page, 2003). However, integration is best interpreted through its dimensions. Referring to Shortell et al. (1996), many experts have suggested four dimensions of integration ultimately leading to systemic integration: integration of care, integration of clinical teams, functional integration, and normative integration (Champagne et al., 2001; Contandriopoulos, 2001; Shortell, 1996; Sicotte et al., 2001; Touati et al., 2001). Integration of care consists of sustained coordination of clinical practices to deal with each patient’s health problems in a comprehensive way. Integration of clinical teams refers to effective and continuous multidisciplinary professional work within and between organizations involved. Functional integration involves coordination between support activities (finance, management, and information systems) and clinical activities. Normative integration aims at ensuring coherence within the collective system of values and representations. Finally, systemic integration refers to the coherence among the different dimensions of integration, such that the integrated system may function in a sustainable way (Contandriopoulos, 2001).

Factors Influencing the Integration Process

Various factors influence the integration process. We classified these into four categories: clinical norms of practice, intraorganizational and interorganizational characteristics, contextual characteristics, and integration mechanisms (Brousselle et al., 2007). Our logic analysis led us to consider clinical norms not just as an output of clinical integration but also as a starting point for establishing that integration. They can be an important instrument to promote interpenetration of professions (Burns, 1999; Ridgely et al., 1990), standardization of practices, and development of a common organizational culture. Some organizational characteristics have a direct influence on the integration process. Thus, the dynamics among professionals (Freidson, 1970, 1984, 1985), the existence of informal networks and interdependencies among organizations (Markham & Lomas, 1995), the existence of a community of practice, the propensity of the organization to innovate, the trustful relationships (Arrow, 1984; Coleman, 1990; Ring & Van de Ven, 1994), the clinical leadership (Fortin et al., 2002; Lamarche et al., 2002; Mueser et al., 2003), and the cultural aspects are all important. Two major contextual dimensions might also influence the integration process: clients’ characteristics and strategic opportunities. Finally, various integration mechanisms have been identified as fostering service integration: training, leadership, creation of clinical protocols, activities that promote interaction, discussions about the institutions’ autonomy, negotiations on linkages between professionals and organizations (Glouberman & Mintzberg, 2001; Lamothe, 1999), and finally a panoply of financial, structural, normative, and interactive incentives (Lamarche et al., 2002; Lamarche et al., 2001; Mueser et al., 2003).

Methods

Research Strategy

We conducted a process evaluation (Brousselle et al., 2006; Champagne et al., 2009; Patton, 2002), which allowed us to do a detailed analysis of the dynamics of integration:

Process evaluations search for explanations of the successes, failures, and changes in the program. [...] Process evaluations not only look at formal activities and anticipated outcomes, but also investigate informal patterns and unanticipated consequences in the full context of program implementation and development. Finally, process evaluations usually include perceptions of people close to the program about how things are going (Patton, 1997, p. 206).

Our research is a case study analysis, which is particularly adapted to the analysis of dynamic processes (Langley, 1999; Patton, 1990; Yin, 1989). We analyzed two cases: a new clinic resulting from the joint venture between a psychiatric hospital and an addiction rehabilitation center and a strategic alliance (contractual agreement) between an addiction rehabilitation center and a psychiatric hospital. We deliberately studied two contrasted forms of integration to observe integration processes in very different contexts of care. The two cases also differ in terms of clientele. In the clinic, they treat referred patients from psychiatric or addiction rehabilitation centers. Patients are mostly diagnosed with psychosis (about 40% in 2003) and personality disorders (about 60% in 2003).

In the second case, a psychiatric institution and an addiction rehabilitation center are combining their efforts to better address co-occurring disorders. Their clientele is much more diverse in terms of mental diagnosis and potentially at a less severe stage. However, we were unable to better appraise the characteristics of their clientele as this information was not systematically compiled.

Field Work and Analysis

We used qualitative data because they were most appropriate for apprehending relationships among subtle and complex variables (DeSardan, 2008; Patton, 2002). Data collection extended from 2003 to 2006, but for the clinic, the data gathered allowed us to cover the change process from the year 2000, before its official creation. In total, we conducted 25 semistructured interviews with clinicians and administrators. Interviews covered mainly the integration process that people experienced. We first interviewed key persons, and then we used a snowball strategy to cover the particular aspects of the study. For the clinic, our interviews were equally divided between persons from the addiction rehabilitation and psychiatric sectors. Several respondents had experience in both sectors. As we adopted a longitudinal perspective, some respondents were interviewed twice. We interviewed most of the professionals (seven out of nine in eight interviews) and administrators (two persons, four interviews) of the new clinic. We conducted four interviews (one of which included two interviewees) in partner organizations to deepen our understanding of the role of the clinic with external resources. We also organized two group interviews with patients, one for psychotic patients and one for patients with personality disorders. Despite our efforts to make the activity attractive, only three patients agreed to participate. These interviews were nevertheless useful to understand their view of the clinic in their experience of care. We also carried out nonparticipant observations of clinicians’ and administrators’ meetings during one full year. For the second case, we met 11 persons in 10 interviews (six persons from the psychiatric hospital, five from the rehabilitation center). All have clinical practice and some of them also hold administrative or research positions. We also conducted nonparticipant observation of related activities, especially of the cross-training activity. Finally, for both cases, we analyzed various documents (administrative data, contracts, etc.).

For each case, we first established the history of events to outline their sequential occurrence (narrative strategy) and to support the construction of logics underlying their sequence (Rossi et al., 2004; Van de Ven, 1992). Then we identified the patterns in the sequence of events that led to results (Langley, 1999). Data generated from the various sources and types of actors were then compared, using graphic representations, to ensure the validity and comprehensiveness of the analysis (Langley, 1999). We then documented all the dimensions of our conceptual framework.

We did a transversal analysis of cases to identify recurring explicative patterns. Referring to our conceptual framework, we identified and explored factors that had an important impact on integration processes. Factors that appeared to be significant in both cases were identified. To validate our interpretation, we presented our preliminary analysis and final results to some of the participants in the study. We believe our study has strong external validity because it is largely based on both a precise comprehension of integration processes and a comparison with existing literature, resulting in a sound understanding and validation of the theoretical aspects of the observed phenomena (Campbell, 1986; Cronbach, 1983).

Findings

On the basis of our conceptual framework, we present the elements that appeared to be significant in the implementation process in each case. We then discuss the facilitating and impeding factors identified through the transversal analysis.

Case Analysis: Combining Psychiatric and Addiction Rehabilitation Services

The new clinic created in 2001 resulted from a joint venture between a psychiatric hospital and an addiction rehabilitation center; it remained linked to the parent organizations. It had four missions: specialized intervention, consultation for other specialized psychiatric and addiction rehabilitation services, training of professionals, and research. Patients with severe conditions (therapeutic failure, need for more specialized services) were referred by a specialized psychiatric or addiction center. The clinical team was composed of three psychiatrists, one social worker, one psychologist, one occupational therapist, one nurse, one psychoeducator, and one neuropsychologist. Professionals were transferred from the parent organizations. Clinicians decided to create specific teams for two cohorts of patients, those with psychosis and those with personality disorders, as the treatment modalities had to be very different according to the specificity of these patients’ behaviors. All patients had severe addiction problems. We first present how integration was achieved at the end of the study, in terms of its dimensions, and then describe the process that lead to such integration.

The Dimensions of Integration

Normative integration. The clinic’s major challenge was to develop common ways of addressing co-occurring disorders. Traditionally, the psychiatric and addiction rehabilitation sectors have had different philosophies of practice that clearly dictated how professionals responded to patients’ needs. Half of the clinic’s employees came from the addiction rehabilitation center and the other half from the psychiatric hospital. Five years after the opening of the clinic, we reported various elements that indicated that professionals had progressed in combining their knowledge of mental and substance abuse and shared practice standards, as expressed by the following quotes: “It’s two cultures, it’s two ways of seeing things, two ways of understanding situations, and I believe that as we work together, we develop a common language” (professional). “In the program, we manage to link, to make sure that the two dimensions of addiction and psychiatry … be worked together on a daily basis” (professional).

Integration of teams. Professionals reported that they worked interdependently and that this work was supported by the administration. “There’s an equilibrium of forces.… I believe that the team, the professionals, after four years, have achieved an interesting level of interdependency. They have learned how to build on each other” (administrator). Professionals decided to focus on psychosis and personality disorders in conjunction with the consumption of substances. Therefore, two subteams emerged, and this led to the development of somewhat independent care processes. Although each subteam worked in a tightly coordinated manner, this mode of specialization led to a loss of versatility and of the ability to address a greater variety of co-occurring disorders. “I have professionals who work for one or the other cohort, without interactions.… Having a “major”: no problem. But there should be versatility” (administrator). No effective interorganizational professional teams were created.

Integration of care. Care included several components, such as the evaluation of patients’ health status and consumption, the therapeutic alliance, the regular and comprehensive follow-up, and the therapeutic continuity within the clinic and with other providers. Clinical practices developed accordingly. However, this called for attention to the changing delineation of professional boundaries. A nurse managed the waiting list and evaluated patients’ eligibility. Yet, because these patients often had serious difficulties in different aspects of their lives, a variety of resources had to be mobilized. This presupposed the existence of a significant network of professionals who were informed and trained as well as the capacity to mobilize resources around the patients. “I would say that we are currently very busy with the liaison activities. For my part, every day” (professional). The variety of other providers presented challenges for a comprehensive integration of care and a need for effective leadership from the clinic. “We have partners who do not share our perception. For example, they might forbid a patient to go out on a weekend because he is intoxicated; this includes his treatment.… We find ourselves with a patient with whom we work on his substance use and he is being punished and cut from services.… I understand it’s a different philosophy. It is through our contacts in the network, our liaison, that we can inform on our way of doing” (professional).

Functional integration. This dimension appeared to be the weakest. The links with the parent organizations encouraged duplication of activities and impeded functional integration. “For example, the nurse who comes from the psychiatric hospital will follow hospital nursing procedures. They refer to common procedures but also to their parent organization’s procedures” (administrator).

Systemic integration. Achievement of systemic integration results from the coherent integration of all dimensions. No such integration had been achieved at the end of the study.

Referring to our model, we describe the process that led to such integration.

Organizational, Clinical, and Contextual Factors and Their Influence on the Integration Process

Organizational characteristics, clinical norms of practice, and patients’ characteristics had an important influence on the integration process.

-

Organizational characteristics. The clinic was created in recognition of the serious lack of services for persons with severe mental and addiction problems. Its existence was due to the leadership of one physician connected with both parent institutions. He was personally involved and militated for its creation. This leadership clearly had an impact in the clinic’s early years and affected the clinic’s development long after the medical leader left the clinic. For example, his clinical expertise affected the selection of preferred diagnoses addressed by professionals. He also influenced the “spirit” that animated professional work.

However, the links with the parent organizations created administrative rigidities that made integration more difficult (e.g., different union constraints, multiple procedures). “Each parent organization demands that their employee uses their procedures” (administrator). Support and clinical activities were not aligned. The clinic also had to undergo two accreditation processes, one for the psychiatric sector and the other in addiction rehabilitation. These elements also had a negative influence on functional integration, resulting in duplication of activities. Furthermore, professionals were hired on a contractual basis, creating a climate of uncertainty among employees. This influenced the pace of team integration because it led to human resources retention problems. This element also influenced normative integration: As personnel changed, discussions on the clinical approach had to start over again. Integration of professional practices presented challenges.

Clinical practice standards. Clearly, the publication of practice standards that recommended blending resources from the psychiatric and addition sectors was an important determinant for the clinic’s creation. Yet, developing effective integrated practices was a challenge because professionals from both sectors had different professional cultures and different ways of dealing with patients. Normative integration was one of the main challenges faced by the clinical team. To fill this gap, for each cohort of patients, a common treatment approach was developed jointly by professionals. This was a foundation for building teams and shared practices. “We developed a common philosophy of treatment. We have a precise framework that we call the treatment protocol. It is our manual” (professional).

Patients’ characteristics. Patients’ characteristics had a major impact on the clinic. They led to the selection of specific diagnoses, which encouraged the emergence of two subteams working somewhat independently. Also, because the patients referred to the clinic had severe conditions, for each patient, professionals were mobilized from a variety of institutions for different aspects of their needs (housing, judicial system, psychiatric and rehabilitation resources, etc.). This had the effect of multiplying the number of actors and clinical approaches. “For each patient, there’s a different team. It requires a lot, a lot of liaison activities. For each team, there may be different approaches, different expectations. It requires a lot of work and flexibility” (professional). Patients confirmed that the existence of numerous and varied professionals had an important influence and provided levers of action. Patients had to deal with divergent philosophies and approaches. This fact increased the difficulty of integrating care among the various providers, particularly for psychotic patients, for whom commitment to treatment is of major importance. Having different poles of intervention complicated this commitment. Conversely, having several professionals constituted a structuring element that is consistent with the clinical approach for patients with personality disorders. This situation presented challenges for normative integration between various providers.

Integration Mechanisms

Integration mechanisms are levers that influence the process. They can be grouped into four categories: clinical levers, sharing of expertise, institutional levers, and network actions.

Clinical levers. Focusing on the development of unified standards of practices geared to patients’ needs helped channel professional work toward increased normative, care, and team integration. However, within the clinic, this needed to be supported by effective clinical leadership and constant and repeated use of levers to enhance the sharing of expertise. This, however, presented challenges in the interorganizational context.

Sharing of expertise. Various means were used to increase sharing of expertise between professionals of the clinic. The first was to encourage team decision making. “The psychiatrist does not always have the last word. Everything is done and discussed by the team. Decision-making is always done by the team” (professional). This was supported by various other means: training (e.g., motivational interviewing), cross-training activities, mirror evaluations, cofacilitation of patient groups, interdisciplinary team meetings, and interventions conducted by at least two professionals. These approaches appeared to be crucial to the process of normative, care, and team integration. However, this was hard to do with professionals working in other institutions and required active networking activities.

Institutional levers. Various institutional means were used to support integration. Codirection of the clinic (psychiatrist and health professional with administrative training) was put in place. All new hires were expected to be professionally versatile. A liaison position was created to select patients on the basis of admissibility criteria and to facilitate relationships with other providers of services. Clinical measurement tools that could potentially be used for research were implemented. These measures had a positive influence on the integration of care process. However, the creation of subteams prevented the administrator from achieving the desired flexibility of professionals and thus limited the overall integration of the clinic. Also, although efforts were made to develop “home” administrative tools, constraints from the parent organizations impeded achievement of functional integration.

Network actions. Achieving normative, care, and team integration was very challenging in the interorganizational context. Attempts were made, focusing on the sharing of expertise: invitations to participate in mirror evaluations, sending health status reports, telephone contacts, negotiation of rules for the sharing of responsibilities on a case-by-case basis, and liaison activities. Actions were also undertaken to confirm the referral position of the clinic within the network (e.g., counseling, coaching of professionals, promotion of joint planning with community organizations).

Case Analysis: A Strategic Alliance

In 2003, a psychiatric hospital and an addiction rehabilitation center signed an agreement to combine their efforts to provide better care for patients with co-occurring disorders. Specifically, the addiction rehabilitation center agreed to offer rehabilitation services to patients coming from the psychiatric hospital and to offer specialized training to the hospital’s employees for early detection of drug abuse. The hospital agreed to offer time-limited telephone and external consultations and access to the emergency room for cases requiring stabilization or diagnosis clarification in order for the patient to be able to continue treatment at the addiction rehabilitation center. It soon became apparent that the agreement was hardly used. The addiction rehabilitation center used it as a means to obtain rapid access to psychiatric consultation, but there seemed to be no impact on the psychiatric hospital. However, other initiatives were put in place to address issues of detection and case evaluation. These were geared toward increasing professional competencies and developing knowledge of external resources. Ultimately, the agreement could be interpreted as one component regulating and legitimizing exchanges between institutions, but the movement to develop an integrated approach was broader than initially foreseen. Using our conceptual framework, we analyzed the dimensions and the process of integration, documenting the various influential elements.

The Dimensions of Integration

Normative integration. People claimed to have acquired increased competencies in co-occurring disorders and more knowledge of other resources’ expertise, and they systematically evaluated their patients’ mental or addiction disorders. “People are beginning to realize that this is a problem that is not going to go away, that they are not well… that there may be people out there who have different ideas that can be useful to them” (professional).

Integration of teams. Professionals claimed to have a better knowledge of network resources, and we observed the development of trustful relationships among various resources. However, we did not observe any tightly coupled teamwork. “There’s been an amazing exchange of information concerning the availability of resources, face to face contact. That is, if they have a case in the future, they know who they can actually talk to and so they’ve been building up a sort of informal … links that I think are really essential to break the ice in a lot of cases” (professional and manager).

Integration of care. Clinical units incorporated new procedures, essentially screening and motivational interviewing, to increase their capacity to deal with co-occurring disorders in their psychiatric or rehabilitation practice. “We are working on compliance to medication and on comorbidity, with alcohol and substance abuse,…. It is new to me, I’ve just finished a training on motivational therapy and the objective is to implement it here” (professional for the psychiatric hospital). “I think we are more aware of the issues (of co-occurring disorders). We are doing much more screening to detect these problems” (professional from the rehabilitation center). “And some units have even gone so far as to the incorporate systematic screening of their patients and they’ve also… are offering something that resembles a brief intervention for substance abuse within a mental health context” (professional).

Functional integration. Functional integration was almost nonexistent and relied on individual initiatives.

Systemic integration. No systematic integration was achieved.

Organizational, Clinical, and Contextual Factors and Their Influence on the Integration Process

Organizational characteristics. The agreement probably would not have existed if there had not already been informal links between both organizations. Several persons who played a key role in the strategic alliance had work experience in both organizations. Furthermore, the presence of a research group affiliated with the psychiatric hospital fostered and legitimized the need for introducing practice changes. The addiction rehabilitation center relied on a number of dynamic clinical leaders who pushed the organization to adopt innovative models of care. Finally, the professionals we met were eager to be trained and to participate in exchange activities. The same group of people organized the various activities at both the addiction rehabilitation center and the psychiatric hospital, thereby blurring the organizational boundaries. The university research group also exercised leadership, influencing the content of the various activities. These leadership and organizational characteristics had a positive influence on normative and care integration.

Clinical practice standards. Professionals were engaged in various activities with the aim of integrating new knowledge into their practice and better understanding others’ expertise and ways of functioning. They were greatly motivated by the prospect of being able to deal with co-occurring disorders by sharing practice standards.

Patients’ characteristics. Both establishments had to deal with a high prevalence of patients with co-occurring disorders. Data were not provided on patients, but as there were no selection criteria, there would certainly have been considerable variability of profiles. This appeared to have a negative influence on the integration of care.

Integration Mechanisms

In terms of our four categories, levers of integration were used as follows:

Clinical levers. No effort was directly invested in developing unified standards of practice. However, emphasis was placed on sharing expertise, in the hope that this would lead to developing integrated practices.

Sharing of expertise. Training was emphasized to address practice issues for co-occurring disorders. A committee on substance use was created with the objective of developing a safe environment and promoting integrated treatment of patients with co-occurring disorders. Activities focused on training of professionals, knowledge of the network resources, and detection of co-occurring disorders (formal training, forum with community resources, open-house days, etc.). Sessions on motivational interviewing were organized. To maximize the impact of these sessions, participants were selected for their leadership, motivation to use the technique, and interest in persuading their colleagues. Participants came from both organizations, in equal numbers. This training activity was perceived as an important opportunity to introduce new ways of dealing with patients with mental and substance use disorders.

Institutional levers. Newly hired professionals were selected according to their interest in addressing the issue of co-occurring disorders. No other institutional lever was used.

Network actions. Network actions were also focused on training. The psychiatric hospital set up a cross-training and capacity building program that began in 2003 with staff rotation among various resources dealing with substance use and mental health: community resources, primary physicians,, and the psychiatric hospital. The experience was repeated in 2004, 2005, and 2007 (Perreault et al., 2005; Perreault et al., 2009). The resource network was also expanded by applying flexible criteria for inclusion in exchange and training activities. Communication was another important element in developing informal and formal networks that were essential for referral as well as for identifying and evaluating problems. For the addiction rehabilitation center, communication was also a determining factor in their ability to get their patients hospitalized when needed.

Practice Implications: What Matters When Integrating Health Care for Persons With Mental and Substance Use Disorders?

The integrations achieved in the two cases were of different intensities. Nevertheless, in both cases, important efforts and achievements were observed in developing integrated approaches to co-occurring disorders. Our study identified various levers and characteristics that had a determining effect on the development of an integrated approach for co-occurring disorders. This is an important contribution to the field of co-occurring disorders, as it is a crucial aspect that is not usually covered (Rush et al., 2008). Reflecting on the dynamics of these two cases, we have formulated six propositions on what matters when integrating services for persons with mental and substance use disorders.

Proposition 1: Changing Practices Takes Time

Developing integrated approaches for co-occurring disorders means changing professional practices fundamentally. Practices are profoundly anchored in one’s experience and expertise. Reconstructing practices involves not only accepting that current practices are not adequate but also accepting and acquiring new ways of practicing. This cannot be done rapidly and linearly. This fact is certainly one explanation for why more extensive changes were not observed in the case of the strategic alliance. Targeted training and exchange activities are useful levers but not enough to change practices.

Proposition 2: Integration Is a Complex, Dynamic Process

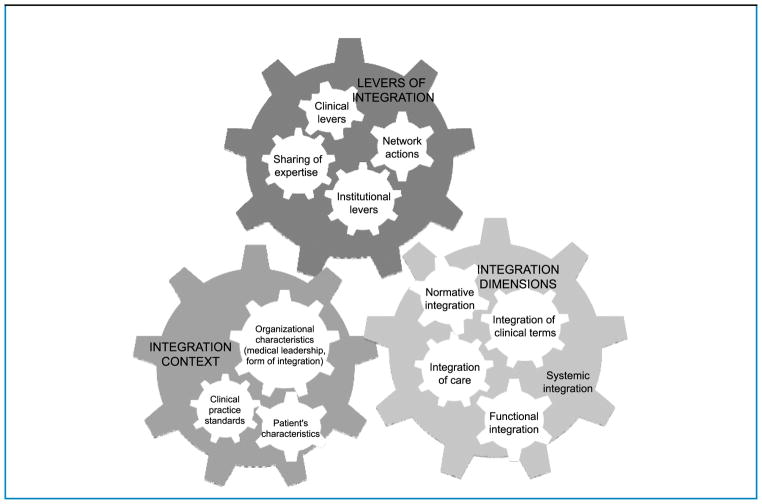

Analyzing our data, we had major discussions on how to represent the causal processes. In fact, it appeared that the levers and other factors we identified as meaningful for developing an integrated approach were not only all important in themselves but were also largely intertwined (see Figure 2). Context is better understood by linking intraorganizational and interorganizational characteristics, clinical standards, and client profiles. Furthermore, even the dimensions of integration influence each other. Integration can be understood as a dynamic, complex, and nonlinear process. The counterpart of this observation is that although there are various ways of fostering integration, the primary focus must be on the relationships among the people involved.

Figure 2.

Toward integration. What matters

Proposition 3: Context Matters When Initiating Integration Processes

Both of the experiences we studied occurred because important factors spurred the development integrated approaches: the recognition that current professional practices did not comply with practice guidelines; the observation that organizations did not offer a satisfying response to patients’ needs; the presence of medical leadership, essential for launching integration processes; and the prevailing organizational form. Although the current form may not have a determinant effect, it influences the process of integration. Indeed, our process evaluation shows that the form of integration, presented in our conceptual framework as an output of the integration process, should rather be considered a component of organizational characteristics. Our evaluation also shows that the structure does not in itself guarantee the achievement of integrated services. Yet, the structural aspects of the organizational form frame the relationships among the individuals involved and therefore influence how the dimensions of integration evolve.

Proposition 4: Patients’ Characteristics Extend the Boundaries of Integration Projects

Patients with co-occurring disorders mobilize various resources, each having their own rules and approaches. Patients need to deal with the contradictions and navigate this complex system. Our study shows that even in more tightly integrated services such as in the joint venture case, professionals are confronted with diverse professional practices outside of their organization that interfere with their protocols and philosophies of treatment. In a context where multiple professionals of various expertise and fields of practice are solicited by the same patient, it is important that these professionals work on sharing their treatment values and on understanding the various practices that will affect the patient’s care. Fostering normative integration with measures that encourage a network perspective helps to enhance consistency among approaches and their effectiveness.

Proposition 5: Communication, Training, and Sharing of Expertise Are Essential Levers for Developing Integrated Approaches

The integration of care, the clinical teams, and the normative integration were achieved because of learning that occurred over time among the professionals involved. This process needs to be continuously stimulated with measures that encourage professionals to develop closer links. Learning and training activities are clearly supportive for professionals dealing with a clientele with co-occurring disorders. They allow discussions on the appropriateness of practice guidelines, the particularities of the various practices, and the possibilities for developing new hybrid practices. Clinical standards help to keep focus on the integration process. Furthermore, communication and information sharing appear to be critical in the specific case of patients with co-occurring disorders because they require the mobilization of multiple resources. These levers need to be used continuously during the integration process. These observations are consistent with those of other studies on the emergence of new health care operational units, in which the development of new trust relationships was seen as a fundamental ingredient of cooperation and coordination between professionals and organizations (Lamothe, 2005, 2006). These new trust relationships are especially needed when working in a network context. Networks increase the level and complexity of interdependencies, and professionals have to deal with a higher level of uncertainty. New trust relationships allow for the development of a normative framework that exercises a form of control over practices.

Proposition 6: Institutional Support Is Also Important

Institutional support was important for sustaining the integration process. Training and communication activities are time consuming, and professionals would not have been able to share their expertise and experience without the support of their institutions nor could leadership have expressed itself. Finally, specific structural measures, such as the creation of a liaison position or the selection of new employees in accordance with objectives, can have a significant impact on integration processes.

Conclusion

Recent writings support the creation of innovative models of services integration for persons living with mental and substance use disorders that are adapted to patients’ characteristics and to organizational contexts. As with others, our study suggests that there is no preferred model for the organization of care for co-occurring disorders; well-coordinated care with close communication between clinicians and treatment that takes full account of comorbidity can also have a significant impact on patients’ health (Donald et al., 2005; Drake et al., 2008). An important and recent publication presents a thorough analysis of the various ways of integrating services, in terms of process and forms of integration, for a clientele with co-occurring disorders (Rush et al., 2008). The authors suggest that integration be adapted to the particularities of context.

Consistent with these findings, we observed that patients’ characteristics will always drive the necessity for reorganizing care. In the particular case of dual diagnosis patients and more broadly of patients with multiple diagnoses (e.g., aging populations, etc.), each patient presents a specific profile of problems that requires a particular configuration of professionals to address. For example, in the case of mental and substance abuse disorders, the challenge is to reconcile contrasting positions on the acceptability of substance consumption and on the imposition of repressive measures when patients are not compliant with professionals’ recommendations. Thus, the challenge is not only to be able to offer coordinated and comprehensive care but also to develop a response that is consistent with those of other professionals. Debates on care models do not provide the answer. Service integration needs to be based on the patients’ experience of care. It is at the core of the learning experience of professionals, enabling the reconciliation of practices (normative integration) and the integration of teams and of care. The various conditions and levers we identified in this research are certainly key elements in developing such an approach. These observations underscore the need for a shift in perspective when studying or implementing integrated services for patients with co-occurring disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canadian Institutes for Health Research for the realization of this research and the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ) that supports Astrid Brousselle’s young investigator award and Chantal Sylvain’s doctoral fellowship.

Contributor Information

Astrid Brousselle, Associate Professor, Community Health Sciences department, University of Sherbrooke, Longueuil, Canada.

Lise Lamothe, Professor, Health Administration Department, University of Montreal, Canada.

Chantal Sylvain, PhD Student, Health Administration department, University of Montreal, Canada.

Anne Foro, PhD Student, Health Administration Department, University of Montreal, Canada.

Michel Perreault, Associate Professor, Douglas Hospital Research Center, McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

References

- Arrow K. The economics of information. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brisson P. Développement du champ québécois des toxicomanies au XXe siècle. In: Brisson P, editor. L’usage des drogues et la toxicomanie. III. Montreal: Gaëtan Morin; 1988. pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Brousselle A, Champagne F, Contandriopoulos AP. Vers une réconciliation des théories et de la pratique de l’évaluation, perspectives d’avenir. Mesure et Évaluation en Éducation. 2006;29(3):57–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brousselle A, Lamothe L, Mercier C, Perreault M. Beyond the limitations of best practices: How program theory analysis helped reinterpret dual diagnosis guidelines. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2007;30(1):94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns L. Polarity management: The key challenge for integrated health systems. Journal of Healthcare Management. 1999;44(1):14–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT. Relabeling internal and external validity for applied social scientist. In: Trochim WMK, editor. Advances in quasi-experimental design and analysis. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1986. pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, Brousselle A, Hartz Z, Contandriopoulos A-P, Denis J-L. L’analyse d’implantation. In: Brousselle A, Champagne F, Contandriopoulos A-P, Hartz Z, editors. L’Évaluation: Concepts et méthodes. Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal; 2009. pp. 225–250. [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, Leduc N, Bilodeau H, Blais R, Clapperton I, Lehoux P, et al. Évaluation de la programmation régionale de soins ambulatoires. Montreal: Groupe de Recherche Interdisciplinaire en Santé, Université de Montréal; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J. Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Contandriopoulos AP, Denis JL, Touati N, Rodriguez R. Intégration des soins: Dimensions et mise en œuvre. Ruptures. 2001;8(2):38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Designing evaluations of educational and social programs. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Dual diagnosis good practice guide. London, UK: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- DeSardan O. La Rigueur du Qualitatif. Les contraintes empiriques de l’interprétation socio-anthropologique. Louvain-La-Neuve: Academia-Bruylant; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Donald M, Dower J, Kavanagh D. Integrated versus non-integrated management and care for clients with co-occuring mental health and substance use disorders: A qualitative systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60:1371–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, Carey KB, Minkoff K, Kola L, et al. Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(4):469–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, O’Neal EL, Wallach MA. A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleury MJ. Émergence des réseaux intégrés de services comme modèle d’organisation et de transformation du système sociosanitaire. Santé Mentale au Québec. 2002;27(2):7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin J, Lamothe L, Lapointe L. La mise en place d’un réseau informatisé en oncologie: La technologie au service d’un réseau de services integrés. Ruptures. 2002;9(1):103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Freidson E. Professional dominance. New York: Atherton; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freidson E. The changing nature of professional control. Annual Review of Sociology. 1984;10:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Freidson E. The reorganization of the medical profession. Medical Care Review. 1985;42(1):11–35. doi: 10.1177/107755878504200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glouberman S, Mintzberg H. Managing the care of health and the cure of disease: Part II. Integration. Health Care Management Review. 2001;26(1):70–84. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Stein JA. Impact of program services on treatment outcomes of patients with comorbid mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(7):1007–1015. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.7.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthCanada. Best practices: Concurrent mental health and substance use disorders. Ottawa, Canada: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kedote MBA, Champagne F. Use of health care services by patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Mental Health and Substance Use: Dual Diagnosis. 2008;1(3):216–227. doi: 10.1080/17523280802274886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche P, Lamothe L, Bégin C, Léger M, Vallières-Joly M. L’intégration des services: Enjeux structurels et organisationnels ou humains et cliniques? Ruptures. 2002;8(2):70–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche P, Lamothe L, St-Pierre M, Simard J-Y, Blanchette L, Trottier J-G. Projet d’action concertée sur les territoires (PACTE): une gestion locale des services du réseau de la santé et des services sociaux en réponse aux besoins des personnes agées. Ottawa: Fonds pour l’adaptation des services de santé, Santé Canada; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lamothe L. La reconfiguration des hôpitaux: Un défi d’ordre professionnel. Ruptures. 1999;6(2):132–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lamothe L. La dynamique interprofessionnelle: La clé de voûte de la transformation de l’organisation des services de santé. In: Contandriopoulos D, Contandriopoulos A-P, Denis J-L, Valette A, editors. L’hôpital en restructuration—Regards croisés sur la France et le Québec. Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lamothe L. Le rôle des professionnels dans la structuration des réseaux: Une source d’innovation. In: Fleury MJ, Tremblay M, Nguyen H, BL, editors. Le système sociosanitaire au Québec: Gouvernance, régulation et participation. Montreal: Gaëtan Morin; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Langley A. Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review. 1999;24(4):691–710. [Google Scholar]

- Markham B, Lomas J. Review of the multi-hospital arrangements literature: Benefits, disadvantages and lessons for implementation. Health Management Forum. 1995;8(3):24–35. doi: 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60916-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, Fox L. Integrated treatment for dual disorders: A guide to effective practice. New York: The Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Page S. “Virtual” health care organizations and the challenges of improving quality. Health Care Management Review. 2003;28(1):79–92. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Utilization-focused evaluation. The new century text. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault M, Bonin JP, Veilleux R, Alary G, Ferland I. Expérience de formation croisée dans un contexte d’intégration des services en réseau dans le Sud-Ouest de Montréal. Revue Canadienne de Santé Mentale Communautaire. 2005;24(1):35–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault M, Wiethauper D, Perreault N, Bonin JP, Brown TG. Meilleures pratiques et formation dans le contexte du continuum des services en santé mentale et en toxicomanie: Le programme de formation croisée du sud-ouest de Montréal. Santé Mentale au Québec. 2009;34:143–160. doi: 10.7202/029763ar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgely S, Goldman HH, Willenbring M. Barriers to the care of persons with dual diagnoses: Organizational and financing issues. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990;16(1):123–132. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring P, Van de Ven A. Developmental processes of cooperative interorganizational relationships. Academy Management Review. 1994;19(1):90–118. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi PH, Freeman HE, Lipsey MW. Evaluation a systematic approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rush B, Fogg B, Nadeau L, Furlong A. On the integration of mental health and substance use services and systems: Main report. Canadian Executive Council on Addictions; Ottawa: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA, Erickson KM, Mitchell JB. Remaking health care in America. Building organized delivery systems. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicotte C, Lehoux P, Champagne F, Gamache M. Analyse de l’implantation d’un réseau interhospitalier de soins pédiatriques: Le réseau mère-enfant. Montreal: Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire en santé, Université de Montréal; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Strategies for developing treatment programs for people with co-occurring substance abuse and mental disorders. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tiet QQ, Mausbach B. Treatments for patients with dual diagnosis: A review. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(4):513–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touati N, Contandriopoulos AP, Denis JL, Rodríguez R, Sicotte C, Nguyen H. Une expérience d’intégration des soins dans une zone rurale: Les enjeux de la mise en oeuvre. Ruptures. 2001;8(2):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven A. Suggestions for studying strategy process [Special issue] Strategic Management Journal. 1992;13:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods. Newbury Park: Sage; 1989. (Rev. ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Ziedonis DM, Smelson D, Rosenthal RN, Batki S, Green AI, Henry RJ, et al. Improving the care of individuals with schizophrenia and substance use disorders: Consensus recommendations. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2005;11(5):315–339. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200509000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]