Abstract

Clinically observed differences in airway reactivity and asthma exacerbations in women at different life stages suggest a role for sex steroids in modulating airway function although their targets and mechanisms of action are still being explored. We have previously shown that clinically relevant concentrations of exogenous estrogen acutely decrease intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) in human airway smooth muscle (ASM), thereby facilitating bronchodilation. In this study, we hypothesized that estrogens modulate cyclic nucleotide regulation, resulting in decreased [Ca2+]i in human ASM. In Fura-2-loaded human ASM cells, 1 nM 17β-estradiol (E2) potentiated the inhibitory effect of the β-adrenoceptor (β-AR) agonist isoproterenol (ISO; 100 nM) on histamine-mediated Ca2+ entry. Inhibition of protein kinase A (PKA) activity (KT5720; 100 nM) attenuated E2 effects on [Ca2+]i. Acute treatment with E2 increased cAMP levels in ASM cells comparable to that of ISO (100 pM). In acetylcholine-contracted airways from female guinea pigs or female humans, E2 potentiated ISO-induced relaxation. These novel data suggest that, in human ASM, physiologically relevant concentrations of estrogens act via estrogen receptors (ERs) and the cAMP pathway to nongenomically reduce [Ca2+]i, thus promoting bronchodilation. Activation of ERs may be a novel adjunct therapeutic avenue in reactive airway diseases in combination with established cAMP-activating therapies such as β2-agonists.

Keywords: sex steroid, bronchial smooth muscle, bronchodilation, bronchoconstriction, calcium, asthma, β-adrenoceptor

asthma, a respiratory disease characterized by airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness, is more common in adult women compared with men (9, 24, 27, 32). Furthermore, adult women experience changes in symptom severity and the number of exacerbations with changes in hormonal status (different phases of the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause) (1, 6, 7, 16, 18). Thus clinical evidence suggests a role for sex steroids (especially female sex steroids) in modulating airway reactivity. What is less clear is whether estrogens or progesterone are detrimental or beneficial to the airway. Whereas clinical evidence would suggest the former, whole animal studies have found reduced airway hyperresponsiveness in the absence of estrogens or estrogen receptor (ER) signaling (3, 4, 10, 23). We previously demonstrated that, in human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells, clinically relevant concentrations of 17β-estradiol (E2) reduce intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) (32). Thus it is possible that estrogens promote bronchodilation by acting on ASM.

β-2 Adrenoceptor (β2-AR) agonists are the most effective bronchodilators available to date and are a mainstay of treatment for acute asthma exacerbations (13, 22). Although β2-agonists are generally effective, tachyphylaxis with repeated use as well as reduced efficacy are well-recognized limitations. Accordingly, there is considerable interest in development of adjunct and novel approaches to enhancing bronchodilation.

Drugs that activate β2-AR are known to increase adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity and adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP), activate protein kinase A (PKA), and produce downstream effects including inhibition of Ca2+ influx, acceleration of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reuptake, and reduction of myosin light chain kinase activity. Studies in nonairway tissues have demonstrated that E2 can increase cAMP. For example, E2-induced protein kinase G-dependent relaxation in the cardiovascular system is mediated by cAMP (19, 20). Vasodilation of porcine coronary arteries by E2 also occurs via cAMP in an endothelium-independent manner (31) (although others have reported that E2 does not affect cAMP levels; 8). Although the mechanisms of E2 effects in the airway are still under investigation, these data raise the question of whether estrogens can increase cAMP in ASM and contribute to bronchodilation. Here, an additional point of interest would be whether estrogens, by working through a beneficial mechanism common to β2-AR, could be used as an adjunct.

In this study, we investigated the mechanisms of rapid, nongenomic actions of estrogen in human ASM, with the hypothesis that E2 increases cAMP and PKA activity. We previously showed that E2 greatly attenuates Ca2+ influx, in part by acting on L-type Ca2+ channels (32), which are also a target of β2-AR agonists (5). Accordingly, we tested the hypothesis that signaling overlap exists between acute estrogen signaling and β2-AR signaling in human ASM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of human ASM cells.

Studies were conducted using ASM cells enzymatically dissociated from lower-order bronchi (3rd to 6th generation) from lung samples incidental to patient (female only) surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester (deidentified samples; typically from lobectomies and pneumonectomies; approved and considered exempt by Mayo Institutional Review Board). Visibly normal airway, as confirmed by a pathologist's review, was excised and rapidly transferred to the laboratory in ice-cold Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS). ASM cells were enzymatically dissociated as previously described (32) using a papain dissociation kit (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ). Cells were maintained at 37°C (5% CO2-95% air) using phenol red-free DMEM/F12 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum until ∼80% confluent. Phenol red-free media was used to avoid ER activation. All experiments were performed in cells from passages 1–3 of subculture that had been serum starved for 48 h before experimentation. Periodic assessment of ASM phenotype was performed by verifying stable expression of smooth muscle actin and myosin, and agonist receptors, with lack of fibroblast marker expression.

cAMP assay.

ASM cells grown to 80% confluence were nonenzymatically harvested and centrifuged at 200 g for 2 min, washed with PBS, and recentrifuged. The cell pellet was resuspended in HBSS containing 5 mM HEPES and 0.5 mM IBMX, pH 7.4. This cell suspension was then treated according to manufacturer's instructions (LANCE Ultra cAMP Kit, Perkin-Elmer, Beverly, MA). The cell suspension (5 μl containing ∼1,000 cells) was added to 5 μl of agonist solutions and allowed to incubate for 30 min at room temperature in an OptiPlate 384-well plate. The detection mix containing Eu-cAMP tracer and ULight-anti-cAMP was added and allowed to incubate for 1 h. The assay was read on a Molecular Devices Flexstation 3 system (LANCE settings; 340 nm Ex/665 nm Em; Sunnyvale, CA). Cyclic AMP standards included with the kit and cell suspensions stimulated with HBSS (containing IBMX) only served as standard curve and internal controls, respectively.

Western blot analysis.

Standard immunoblotting techniques were used for detection of ERα (SC-542; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), ERβ (Santa Cruz SC-53494), and β2-AR (Santa Cruz SC-9042) and detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies in ASM cell lysates subjected to coimmunoprecipitation. Primary antibody (2 μg, rabbit anti-β2-AR, Santa Cruz SC-9042) was used per 200 μl of whole cell lysate and incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation. Protein A agarose beads (50 μl) were added to the sample and incubated for 4 h at 4°C. Proteins were recovered as described previously (32). These samples were then processed as described for Western analysis (β2-AR; no. 2100065; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Blots were imaged on a Kodak ImageStation 4000mm (Carestream Health, New Haven, CT) and quantified using densitometry.

[Ca2+]i imaging.

Techniques for real-time Ca2+ imaging have been previously described (29, 32). Briefly, ASM cells were loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 AM (5 μM, 50 min, room temperature) and imaged using a Metafluor-based real-time microscopy system (Nikon Instruments TE2000 inverted microscope; ×40/1.3 NA oil-immersion lens; 1 Hz; acquisition of 510 nm emissions following alternative excitation at 340 vs. 380 nm). In all experiments involving [Ca2+]i measurements, 10 μM histamine was used as an agonist to induce [Ca2+]i increases.

Force measurements.

All animal experiments were approved by Columbia University's Animal Care and Use Committee, and animal care was in accordance with the guidelines published by the American Physiological Society. Female Hartley guinea pigs (∼400 g) were obtained from Charles River and were euthanized with intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital. The trachea was quickly removed and placed on ice in Krebs-Hensleit buffer of the following composition in mM: 118 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 0.24 MgSO4, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4. The epithelium was removed by gentle abrasion with cotton. Detailed methods have been previously described (14). Briefly, tracheal rings were suspended in 4-ml-water jacketed organ baths (37°C: Radnoti Glass Technology, Monrovia, CA) and connected to a Grass FT03 force transducer (Grass Telefactor, West Warwick, RI) using silk sutures and adjusted to a resting tension of 1 g and allowed to equilibrate for 1 h with buffer exchanges every 15 min. Two complete acetylcholine (ACh) dose-response curves were constructed (100 nM-100 μM) and then thoroughly washed. Rings were then contracted with ∼EC50 ACh. Following stable force generation with ACh, samples were treated with vehicle or 50 nM E2 for 20 min, followed by an isoproterenol (ISO) dose response curve (100 pM-10 μM; half-log increments). Measurements are expressed as a percentage of remaining contraction of ACh-plateau force.

Parallel studies were conducted in isolated, epithelium-denuded bronchial rings from female patients, obtained as described above for cells. To avoid confounding effects of variable chronic inflammation and/or cigarette smoke exposure, medical histories were reviewed, and samples were taken only from female patients without these problems.

Materials.

2′,5′-Dideoxyadenosine was obtained from Tocris Biosciences (Ellisville, MO). E2, ISO, KT5720, forskolin, and other chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical unless mentioned otherwise. Tissue culture reagents, including Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium F-12 (DMEM F/12) and FBS, were obtained from Invitrogen.

Statistical analysis.

Seven bronchial samples from different female patients were used to obtain ASM cells. [Ca2+]i experiments were performed in at least 25 cells, each from four different bronchial (patient) samples although not all protocols were performed in each sample obtained. In all cases using ASM cells, n represents numbers of patients. The guinea pig trachea studies involved five animals with eight rings/animal. In experiments where responses were compared in the presence or absence of specific drugs, paired t-test was used, whereas population studies were compared using unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA with repeated measures as appropriate. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05. All values are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Estrogen potentiates ISO effects on [Ca2+]i regulation.

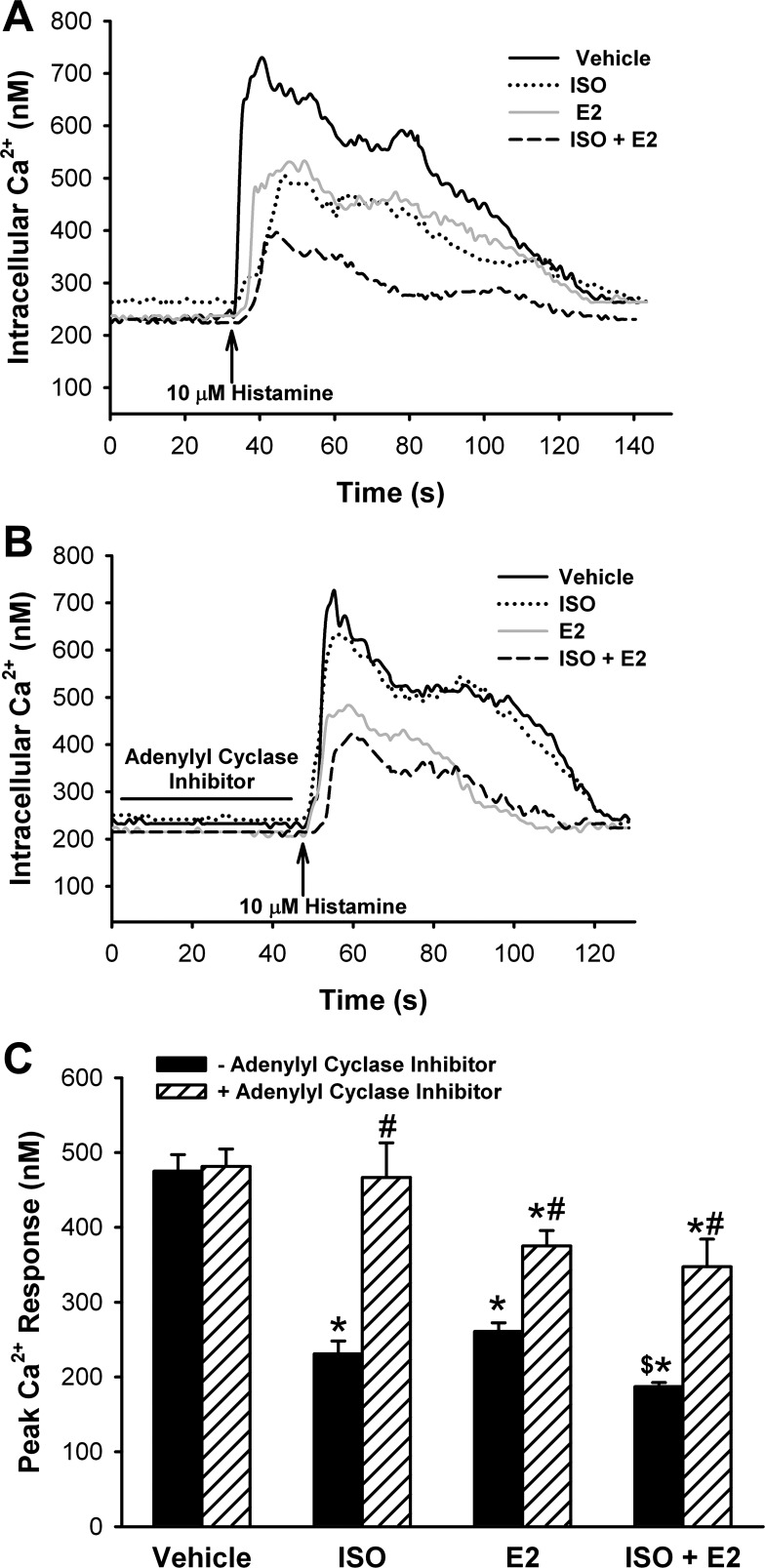

Ca2+ imaging of Fura-2-loaded ASM cells showed that exposure to E2 (1 nM) for 15 min significantly reduced by ∼40% increases in peak [Ca2+]i induced by histamine, consistent with our previous finding (32) (Fig. 1A; P < 0.05). Exposure for 15 min to 100 nM ISO also significantly reduced [Ca2+]i responses to histamine to comparable levels (Fig. 1A; P < 0.05). The additional presence of E2 (1 nM) during ISO exposure resulted in a larger, ∼65% reduction in peak [Ca2+]i, which was significantly different from either E2 or ISO alone (Fig. 1, A and C; n = 5, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle as well as to E2).

Fig. 1.

A: estradiol (E2) potentiates β-agonist effects on airway smooth muscle (ASM) intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i). In Fura-2-loaded human ASM cells, histamine-induced increases in [Ca2+]i were blunted by isoproterenol (ISO; 100 nM) and E2 (1 nM). The combination of E2 and ISO further decreased [Ca2+]i response to agonist (a representative tracing of 5 experiments). B: inhibition of adenylyl cyclase blunts E2 effects. In Fura-2-loaded cells, the effect of ISO was reversed with the adenylyl cyclase (AC) inhibitor 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine (20 μM 15 min alone, 15 min + ISO). Treatment with this inhibitor partially reverses the observed E2 effects (a representative tracing of 5 experiments). The combination of ISO and E2 was reversed to the same levels as E2 alone yet remained significant compared with vehicle (n = 5). C: summary of estradiol effects on calcium regulation in ASM. E2 reduced [Ca2+]i response to histamine by ∼45%. ISO decreased [Ca2+]i by ∼50%. The combination of ISO and E2 had a greater effect than either treatment alone, reducing [Ca2+]i by ∼60%. ISO, the combination of ISO and E2 and E2 alone were reversed by AC inhibition. *P < 0.05 significant compared with vehicle. $P < 0.05 significant compared with ISO or E2 alone. #P < 0.05 significant inhibitor effect compared with ISO, E2, and ISO + E2, respectively (n = 5).

Estrogen effects on ASM involve adenylyl cyclase.

In a separate set of experiments, ASM cells were pretreated with the AC inhibitor, 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine (20 μM) for 15 min before and during exposure to E2, ISO, or a combination of E2 and ISO (concentrations as above). Cells were then stimulated with 10 μM histamine. The AC inhibitor completely prevented the previously observed reduction of [Ca2+]i responses induced by ISO (Fig. 1, B and C: n = 5; P < 0.05 for inhibitor effect). However, a residual 20–25% reduction in [Ca2+]i responses persisted in groups treated with E2 (Fig. 1, B and C; P < 0.05).

ER activation increases cAMP.

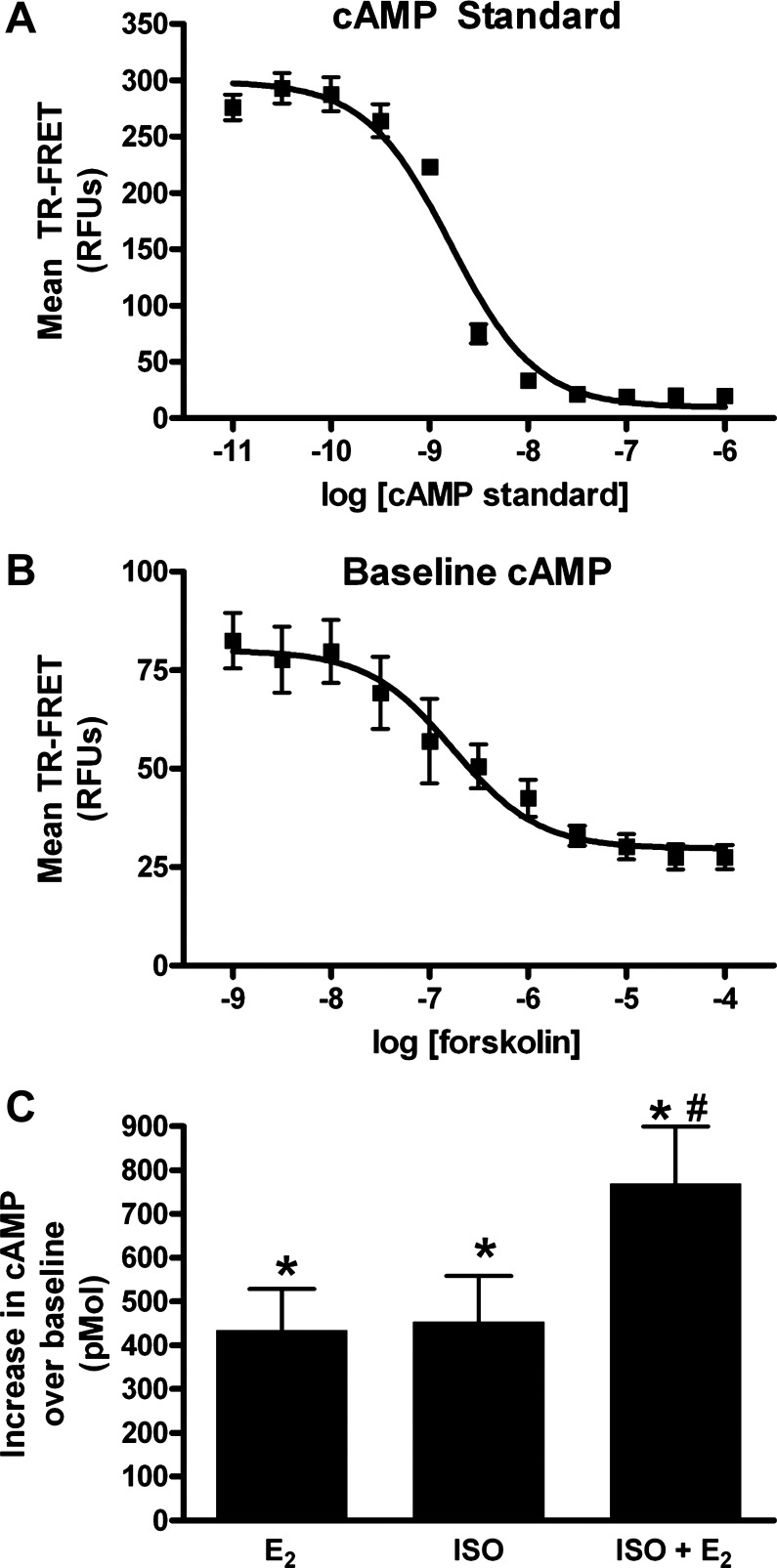

In a first set of experiments, baseline cAMP accumulation by human ASM cells was evaluated using increasing concentrations of forskolin (1 nM to 100 μM, half-log increments) and time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET). Cyclic AMP standards were used to construct a TR-FRET-concentration curve and calculate the amount of cAMP (Fig. 2A). Baseline cAMP by the forskolin method showed a dynamic range of 30 nM to 10 μM (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, the effects of E2 (10 nM), ISO (100 pM), or the combination of E2 and ISO were evaluated. All three treatments showed a substantial increase in cAMP compared with vehicle (HBSS only) controls (Fig. 2C; n = 5–8, *P < 0.05). The E2 and ISO combination showed an additive effect in total cAMP produced (Fig. 2C; n = 5–8, #P < 0.05 compared with E2 or ISO alone). It should be noted that lower concentration of ISO was used in this analysis based on pilot studies showing saturation of the cAMP assay when 100 nM concentrations were used.

Fig. 2.

cAMP regulation in ASM cells. A: cyclic-AMP standards (10 pM-1 μM; half-log increments) were used to create a concentration calibration based on decreasing time-resolved fluorescent resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET). B: in ASM cells, forskolin (1 nM-100 μM; half-log increments) caused a concentration-dependent decrease in TR-FRET and thus increase in cAMP. Dose response curve of mean values (line = 4 parameter sigmoid fit R2 = 0.98.) C: in ASM cells, 100 pM ISO substantially increased cAMP over basal cAMP in untreated controls. Treatment with 10 nM E2 increased cAMP to levels comparable to ISO. Treatment combining E2 and ISO further increased cAMP above basal levels *P < 0.05 significant compared with vehicle. #P < 0.05 compared with E2 or ISO alone (n = 5–8).

Estrogen effects on ASM are PKA dependent.

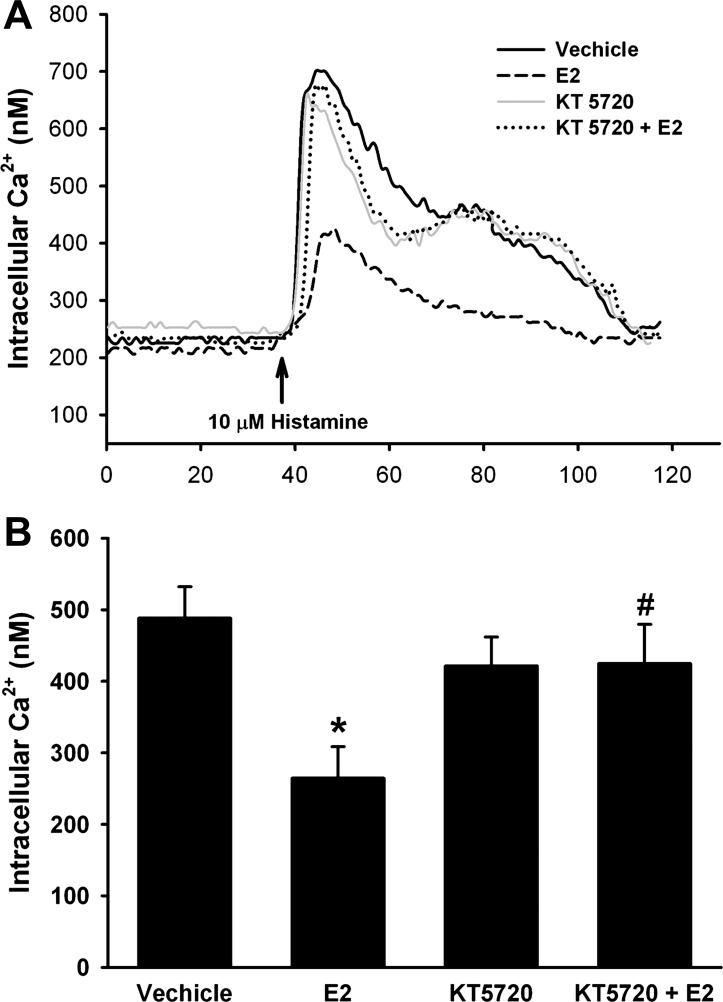

In Fura-2-loaded ASM cells, pretreatment with the PKA antagonist KT5720 (100 nM) for 15 min before and during E2 treatment completely prevented E2 effects on the [Ca2+]i responses to histamine. KT5720 treatment alone (i.e., no E2) did not substantially alter the [Ca2+]i response to histamine (Fig. 3: n = 4, P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

A and B: E2 effects on ASM involve PKA activation. Acute exposure to E2 decreases [Ca2+]i response to 10 μM histamine by ∼40%. This response is abrogated by pretreatment with the PKA antagonist KT5720 (100 nM, 15 min alone, 15 min + E2). KT5720 alone had no effect on [Ca2+]i responses to histamine compared with vehicle. *P < 0.05 significant compared with vehicle, #P < 0.05 significant KT5720 compared with E2 alone (n = 4).

Estrogen potentiates relaxation effects of isoproterenol on contracted airways.

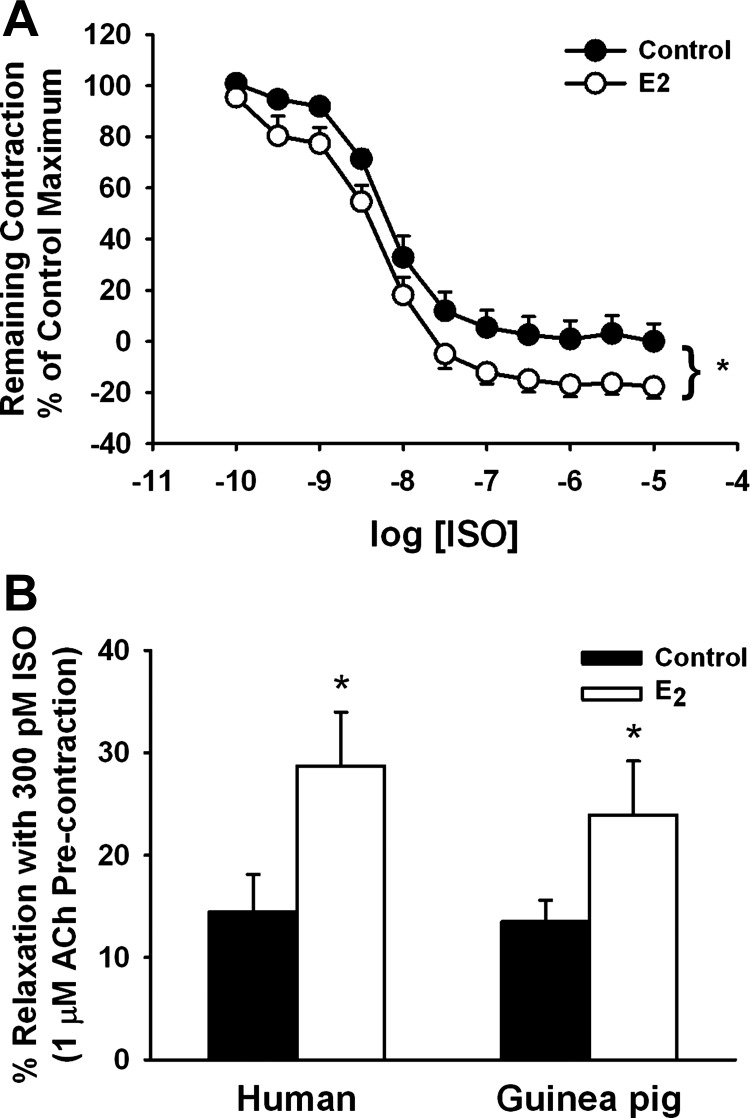

In epithelium-denuded tracheal rings from female guinea pigs contracted with 1 μM ACh (∼EC50 based on a control dose-response curve), the presence of 50 nM E2 increased the extent of relaxation induced by ISO (100 pM-100 nM, half-log increments) compared with vehicle-treated tissues (Fig. 4A; P < 0.05 for E2 effect). Indeed, in the presence of E2, relaxation to and below baseline was achieved at lower ISO concentrations (Fig. 4A). This was also reflected by greater maximum relaxation of 133.0 ± 9.2% in the presence of E2 vs. 116.7 ± 10.8% with vehicle, when additional ISO concentrations were added (Fig. 4A, n = 40 rings from 5 animals, *P < 0.001, paired t-test).

Fig. 4.

E2 potentiates ISO-induced relaxation of ASM. A: in epithelium-denuded bronchial rings from female guinea pigs contracted with acetylcholine (ACh, 1 μM ∼EC50), pretreatment with 50 nM E2 significantly increased relaxation to ISO (100 pM-10 μM; half-log increments), with maximal relaxation below baseline also being greater in the presence of E2 (n = 40 rings from 5 animals). B: as with guinea pig, relaxation of ACh precontracted epithelium-denuded human bronchial rings induced by 300 pM ISO was enhanced by E2. *P < 0.05 significant E2 effect (n = 5).

We compared the efficacy of E2 to enhance ISO-induced relaxation in epithelium-denuded human bronchial rings. Complete relaxation was observed at ∼10 nM in the absence of E2, which was comparable to that observed in the guinea pig (not shown). Furthermore, in the presence of E2, the extent of relaxation and sensitivity to ISO were increased, such that, at 300 pM ISO, the human bronchial rings showed greater relaxation in the presence of E2 (Fig. 4B; P < 0.05).

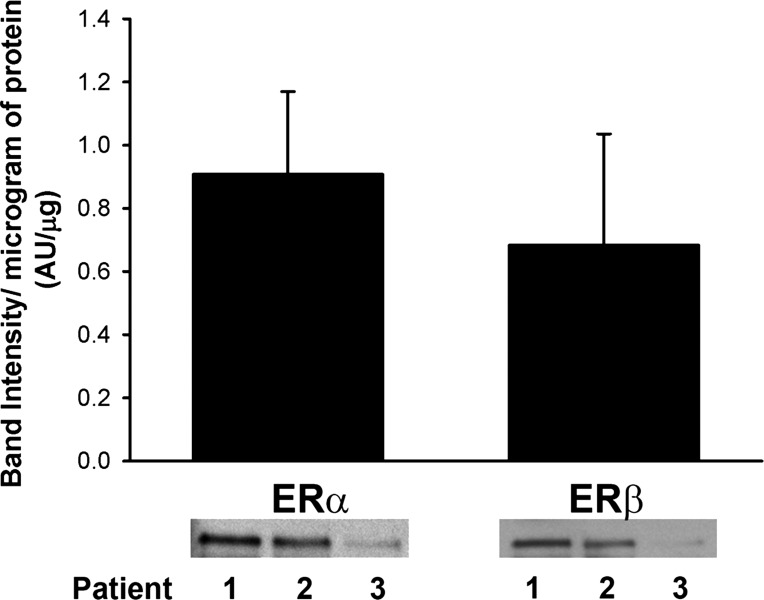

ERs colocalize with β2-AR in human ASM.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) of the β2-AR with subsequent Western analysis for ER-α or ER-β revealed that both ER isoforms colocalize with β2-AR in separate IPs (Fig. 5). A strong band at 66 kDa corresponding to the full-length ER-α was visible, whereas a band of slightly lower molecular weight (56 kDa) corresponding to ER-β was also expressed. Band intensity varied between patients and was proportional to protein concentration (0.91 ± 0.26, ER-α; 0.68 ± 0.35, ER-β; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Estrogen receptor (ER)-α and ER-β colocalize with β2-adrenergic receptor (AR) in human ASM. Coimmunoprecipitation of β2-ARs and subsequent Western analyses revealed that ER-α, and, in separate experiment, ER-β colocalizes with β2-AR (n = 3 patients). Although band intensity varied between patients, expression of both ER-α and ER-β was proportional to protein concentration.

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that clinically relevant concentrations of estrogens reduce [Ca2+]i in human ASM (32).The present study now demonstrates the role of cAMP and PKA in mediating these effects. The role of the cAMP/PKA pathway in β2-AR agonist action in bronchodilation is well recognized, as are tolerance and β2-AR desensitization with chronic use (2). Importantly, our results show that estrogens can potentiate the effects of isoproterenol in reducing [Ca2+]i in human ASM via activation of cAMP and PKA. This potentiating effect appears to translate to enhanced bronchodilation, evidenced by increased ISO-induced relaxation of bronchial rings from both guinea pigs and humans when E2 is present. Here, the colocalization of β2-AR and ER may play a role in the interaction between these receptors in potentiating relaxation. Our data hint at a potentially novel avenue for enhancing β2-AR-induced bronchodilation by modulation of estrogen signaling. Given the common, cAMP-dependent mechanism for both receptors, the relevance of such an avenue lies in the possibility of reducing β2-AR utilization and thus desensitization.

Estrogen signaling in the airway.

Sex differences in airway function of women at different life stages have raised the question of hormonal influences, especially on ASM, the major regulator of airway tone. In this regard, the limited data on sex steroid effects on airway function are conflicting. Clinical data would suggest a worsening of airway function with increased estrogen levels. However, from an in vivo perspective, ER-α-deficient mice exhibit increased airway hyperresponsiveness (4), an effect reversed by hormone replacement in ovariectomized animals (10), consistent with a bronchodilatory role for estrogens. In vitro, we previously showed that both full-length ER-α and ER-β (32) are present in ASM of female patients and that clinically relevant concentrations of estrogens can activate these receptors to reduce agonist-induced elevations in [Ca2+]i via inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels and store-operated Ca2+ entry (32). The in vitro cellular data suggesting a bronchodilatory effect of estrogens are generally consistent with data in mouse tracheal and bronchial rings sensitized by serum from asthmatic humans, where carbachol-induced contractions are reduced by 100 nM E2 (11). These effects are also similar to those observed in the vasculature (26) and occur on a rapid time scale (as also demonstrated in the present study), distinct from the well-known transcriptional (genomic) response to estrogens (17). The reasons underlying the discrepancies between the clinical and preclinical data in estrogen effects are not clear but may involve the balance between genomic vs. nongenomic effects as well as estrogen effects on the airway vs. the immune system (30). Regardless, what is important to note is that, as with the vasculature, estrogens do have nongenomic effects on time scales similar to the activation patterns for the cyclic nucleotide cascades, which lend credence to the idea that estrogen effects on [Ca2+]i (and thus tone) may be mediated via cAMP.

The present study demonstrates that estrogen activates the cAMP/PKA pathway with downstream effects on [Ca2+]i and relaxation. Estrogen effects on cAMP and PKA signaling in other tissues are controversial. Studies in porcine coronary arteries show that E2 either increases (19, 31) or has no effect on cAMP levels (8). In rat heart, Wong and colleagues (33) found that estrogen inhibits L-type Ca2+ channel influx, blocks isoprenaline-induced increase in cAMP, and suppresses PKA activity. However, in that study, these effects appear to involve estrogen-induced downregulation of β1-AR. In the context of these previous studies in nonairway tissues, the results of the present study are novel in highlighting an estrogen-mediated elevation in cAMP and activation of PKA in human ASM. Under physiological conditions, it is likely that E2 activates ER-α and ER-β, both of which were shown to independently colocalize with β2-ARs in human ASM.

The downstream effects of estrogen-induced activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway is reduced [Ca2+]i in ASM cells and potentiation of ISO-induced relaxation of precontracted ASM tissue. The cAMP-PKA pathway can certainly modulate a number of Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms. In neurons (25, 34), nongenomic, membrane actions of estrogen involve voltage-gated calcium channels, which are also a target in ASM (32) and thus a potential mechanism for cAMP-induced reduction in [Ca2+]i. In a previous study also in human ASM, we have shown that store-operated Ca2+ entry, a mechanism inhibited by estrogens (32), is also inhibited by cAMP (28). PKA is also known to phosphorylate the Ca2+-sensitive large conductance potassium (BKCa) channel (21), and previous studies in murine models of asthma have shown beneficial effects of estrogen being mediated in part via BKCa channels (11); as such, it is likely that estrogen-induced increases in cAMP/PKA activity affect plasma membrane Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms in ASM.

Estrogen and β2-AR effects in ASM.

The role of the cAMP/PKA pathway in β2-AR action in ASM is well known (13, 15). It is also recognized that frequent or sustained β2-AR activation results in receptor internalization and desensitization (2), raising the need for alternative or adjunct avenues to sustain bronchodilatory activity. The results of the present study show that clinically relevant concentrations of estrogen can potentiate β2-AR induced reduction in [Ca2+]i of ASM, as well as relaxation of ASM. From a clinical perspective, there are limited data supporting a beneficial role for estrogens. For example, Gibbs and colleagues (12) showed that, in the few days before the onset of menses, women asthmatics had significantly decreased peak expiratory flow rates and increased dependence on albuterol (12), whereas exogenous estrogen has been reported to improve asthma symptoms in women (6). Importantly, our data show that acute estrogen administration potentiates the effects of isoproterenol, resulting in greater relaxation at submaximal isoproterenol concentrations as well as greater maximal relaxation compared with isoproterenol-treated tissues alone. Furthermore, we show that both estrogens and β2-AR activate a common mechanism, cAMP/PKA, thus raising the possibility of using estrogens to enhance β2-AR agonist effects to induce bronchodilation. Whether the combination of estrogens and β2-AR agonists is of benefit clinically remains to be shown.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Young Clinical Scientist Award from the Flight Attendants Medical Research Institute (FAMRI) to V. Sathish, and NIH R01 grants HL088029 to Y. Prakash, HL090595 to C. Pabelick, and T32GM008464-19 to E. Townsend.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors Dr. Charles Emala and Dr. Yi Zhang for help and input with these studies.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bellia V, Augugliaro G. Asthma and menopause. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 67: 125–127, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Broadley KJ. Review of mechanisms involved in the apparent differential desensitization of β1- and β2-adrenoceptor-mediated functional responses. J Auton Pharmacol 19: 335–345, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Card JW, Carey MA, Bradbury JA, DeGraff LM, Morgan DL, Moorman MP, Flake GP, Zeldin DC. Gender differences in murine airway responsiveness and lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation. J Immunol 177: 621–630, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carey MA, Card JW, Bradbury JA, Moorman MP, Haykal-Coates N, Gavett SH, Graves JP, Walker VR, Flake GP, Voltz JW, Zhu D, Jacobs ER, Dakhama A, Larsen GL, Loader JE, Gelfand EW, Germolec DR, Korach KS, Zeldin DC. Spontaneous airway hyperresponsiveness in estrogen receptor-alpha-deficient mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 126–135, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16: 521–555, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chandler MH, Schuldheisz S, Phillips BA, Muse KN. Premenstrual asthma: the effect of estrogen on symptoms, pulmonary function, and β2-receptors. Pharmacotherapy 17: 224–234, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chhabra SK. Premenstrual asthma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 47: 109–116, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Christ M, Gunther A, Heck M, Schmidt BM, Falkenstein E, Wehling M. Aldosterone, not estradiol, is the physiological agonist for rapid increases in cAMP in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation 99: 1485–1491, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Marco R, Locatelli F, Sunyer J, Burney P. Differences in incidence of reported asthma related to age in men and women. A retrospective analysis of the data of the European Respiratory Health Survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 68–74, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dimitropoulou C, Drakopanagiotakis F, Chatterjee A, Snead C, Catravas JD. Estrogen replacement therapy prevents airway dysfunction in a murine model of allergen-induced asthma. Lung 187: 116–127, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dimitropoulou C, White RE, Ownby DR, Catravas JD. Estrogen reduces carbachol-induced constriction of asthmatic airways by stimulating large-conductance voltage and calcium-dependent potassium channels. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 239–247, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gibbs CJ, Coutts II, Lock R, Finnegan OC, White RJ. Premenstrual exacerbation of asthma. Thorax 39: 833–836, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Giembycz MA, Newton R. Beyond the dogma: novel β2-adrenoceptor signalling in the airways. Eur Respir J 27: 1286–1306, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gleason NR, Gallos G, Zhang Y, Emala CW. The GABAA agonist muscimol attenuates induced airway constriction in guinea pigs in vivo. J Appl Physiol 106: 1257–1263, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hakonarson H, Grunstein MM. Regulation of second messengers associated with airway smooth muscle contraction and relaxation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158: S115–S122, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanley SP. Asthma variation with menstruation. Br J Dis Chest 75: 306–308, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews J, Cheng G, Hartman J, Tujague M, Strom A, Treuter E, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev 87: 905–931, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Juniper EF, Daniel EE, Roberts RS, Kline PA, Hargreave FE, Newhouse MT. Effect of pregnancy on airway responsiveness and asthma severity. Relationship to serum progesterone. Am Rev Respir Dis 143: S78, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keung W, Chan ML, Ho EY, Vanhoutte PM, Man RY. Non-genomic activation of adenylyl cyclase and protein kinase G by 17β-estradiol in vascular smooth muscle of the rat superior mesenteric artery. Pharmacol Res 64: 509–516, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keung W, Vanhoutte PM, Man RY. Acute impairment of contractile responses by 17β-estradiol is cAMP and protein kinase G dependent in vascular smooth muscle cells of the porcine coronary arteries. Br J Pharmacol 144: 71–79, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kotlikoff MI, Kamm KE. Molecular mechanisms of β-adrenergic relaxation of airway smooth muscle. Annu Rev Physiol 58: 115–141, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krymskaya VP, Panettieri RA., Jr Phosphodiesterases regulate airway smooth muscle function in health and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol 79: 61–74, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsubara S, Swasey CH, Loader JE, Dakhama A, Joetham A, Ohnishi H, Balhorn A, Miyahara N, Takeda K, Gelfand EW. Estrogen determines sex differences in airway responsiveness after allergen exposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38: 501–508, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Melgert BN, Ray A, Hylkema MN, Timens W, Postma DS. Are there reasons why adult asthma is more common in females? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 7: 143–150, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mermelstein PG, Becker JB, Surmeier DJ. Estradiol reduces calcium currents in rat neostriatal neurons via a membrane receptor. J Neurosci 16: 595–604, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miller VM, Duckles SP. Vascular actions of estrogens: functional implications. Pharmacol Rev 60: 210–241, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paoletti P. Application of biomarkers in population studies for respiratory non-malignant diseases. Toxicology 101: 99–105, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prakash YS, Iyanoye A, Ay B, Sieck GC, Pabelick CM. Store-operated Ca2+ influx in airway smooth muscle: Interactions between volatile anesthetic and cyclic nucleotide effects. Anesthesiology 105: 976–983, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prakash YS, Thompson MA, Vaa B, Matabdin I, Peterson TE, He T, Pabelick CM. Caveolins and intracellular calcium regulation in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1118–L1126, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Straub RH. The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev 28: 521–574, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Teoh H, Man RY. Enhanced relaxation of porcine coronary arteries after acute exposure to a physiological level of 17β-estradiol involves non-genomic mechanisms and the cyclic AMP cascade. Br J Pharmacol 129: 1739–1747, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Townsend EA, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Rapid effects of estrogen on intracellular Ca2+ regulation in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L521–L530, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wong KA, Ma Y, Cheng WT, Wong TM. Cardioprotection by the female sex hormone—interaction with the β1-adrenoceptor and its signaling pathways. Sheng Li Xue Bao 59: 571–577, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang C, Bosch MA, Rick EA, Kelly MJ, Ronnekleiv OK. 17β-Estradiol regulation of T-type calcium channels in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci 29: 10552–10562, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]