Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) exert important nonimmune functions in lung homeostasis. TLR4 deficiency promotes pulmonary emphysema. We examined the role of TLR4 in regulating cigarette smoke (CS)-induced autophagy, apoptosis, and emphysema. Lung tissue was obtained from chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) patients. C3H/HeJ (Tlr4-mutated) mice and C57BL/10ScNJ (Tlr4-deficient) mice and their respective control strains were exposed to chronic CS or air. Human or mouse epithelial cells (wild-type, Tlr4-knockdown, and Tlr4-deficient) were exposed to CS-extract (CSE). Samples were analyzed for TLR4 expression, and for autophagic or apoptotic proteins by Western blot analysis or confocal imaging. Chronic obstructive lung disease lung tissues and human pulmonary epithelial cells exposed to CSE displayed increased TLR4 expression, and increased autophagic [microtubule-associated protein-1 light-chain-3B (LC3B)] and apoptotic (cleaved caspase-3) markers. Beas-2B cells transfected with TLR4 siRNA displayed increased expression of LC3B relative to control cells, basally and after exposure to CSE. The basal and CSE-inducible expression of LC3B and cleaved caspase-3 were elevated in pulmonary alveolar type II cells from Tlr4-deficient mice. Wild-type mice subjected to chronic CS-exposure displayed airspace enlargement;, however, the Tlr4-mutated or Tlr4-deficient mice exhibited a marked increase in airspace relative to wild-type mice after CS-exposure. The Tlr4-mutated or Tlr4-deficient mice showed higher levels of LC3B under basal conditions and after CS exposure. The expression of cleaved caspase-3 was markedly increased in Tlr4-deficient mice exposed to CS. We describe a protective regulatory function of TLR4 against emphysematous changes of the lung in response to CS.

Keywords: inflammation, Toll-like receptor

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), one of the major leading causes of death worldwide (8, 20), is characterized by expiratory airflow limitation and parenchymal emphysema (26). Exposure to cigarette smoke (CS) represents the most important risk factor for the development of COPD; however, only ∼15% of smokers develop the disease (1). The pathogenesis of COPD has not been fully elucidated and involves multiple injurious processes including inflammation, alteration of alveolar maintenance, imbalances in cellular protease and antiprotease activities, oxidative stress, cellular apoptosis, and abnormal cellular repair (33). Pulmonary emphysema is a major subset of COPD and is defined anatomically as the destruction of the distal lung parenchyma and enlargement of the airspaces. While cigarette smoking has been known as an important factor in the development of emphysema of COPD, several genes have been identified as potentially involved in emphysema susceptibility (21).

Previously, we have demonstrated that the occurrence of macroautophagy (hereafter, autophagy) was increased in human lung tissues from patients with COPD and as a general response to CS exposure in rodent lungs or epithelial cells (4, 15, 26). Autophagy exerts essential functions in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis and adaptation to adverse environments (12, 18, 31). More than 30 autophagy-related genes and gene products critical in the regulation of autophagy have been identified in yeast and higher mammals (12). Among these, the microtubule-associated protein-1 light-chain 3 (LC3; yeast, Atg8) is cleaved from a proform by Atg4 and then conjugated with phosphatidylethanolamine by the sequential action of Atg7 and Atg3 (12). In mammals, the conversion of LC3 from LC3-I (free form) to LC3-II (phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form) represents a key step in autophagosome formation (21). Recently, we have demonstrated that LC3B plays a pivotal role in CS-induced apoptosis, autophagy, and emphysema in mice (5).

The Toll-like receptor (TLR) family exerts important functions in innate immune responses and the subsequent induction of adaptive immune responses (13). TLRs recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) found in a broad range of microbial pathogens. TLR4 specifically recognizes the LPS of gram-negative bacteria (13). Recently, several TLRs, including TLR4, have been identified as also exerting a role in the regulation of autophagy (2, 6, 9, 17, 19, 28, 32). TLR4 has a role of maintaining constitutive lung integrity by modulating oxidant generation. TLR4 deficiency led to age-dependent emphysema after the lungs were fully developed in the mouse model (34).

However, the role of TLR4 in the regulation of autophagy in vivo, whether inducible or inhibitory, remains unclear. Furthermore, there are no studies on the influence or role of TLR4 in pulmonary emphysema after CS exposure. In the present study, we have investigated the expression of TLR4 in patients with COPD and demonstrate the protective role of TLR4 against CS-induced autophagy and apoptosis in vitro and in the development of pulmonary emphysema in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

All human lung tissues were obtained from Lung Tissue Research Consortium. Disease severity in COPD was classified following the guidelines of the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (10). The majority of COPD GOLD 2 and GOLD 4 groups were ex-smokers. The control group consisted of never-smokers. Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. The severity of emphysema was visually assessed according to a modified scoring system as previously described (11, 25). Emphysema was graded on a five-point scale based on the percentage of lung involved: 0, no emphysema; 1, up to 25% of lung parenchyma involved; 2, between 26% and 50% of lung parenchyma involved; 3, between 51% and 75%; and 4, between 76% and 100%. Grades for the axial images of each lung were added and divided by the number of images evaluated to yield emphysema scores that ranged from 0 to 4.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects with never-smokers or COPD

| Never-Smokers, n = 5 | COPD GOLD 2, n = 15 | COPD GOLD 4, n = 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 79 ± 3 | 72 ± 2 | 55 ± 2*# |

| Sex, n (male:female) | 0:5 | 10:5* | 8:7* |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 25 ± 1*# |

| Current smoker at entry, N, % | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Smoking index at entry, pack-yr | 0 ± 0 | 59 ± 7* | 51 ± 9* |

| Lung function | |||

| FEV1, % predicted | 102.4 ± 5.7 | 66.3 ± 1.8* | 19.7 ± 0.6*# |

| FVC, % predicted | 99.8 ± 5.2 | 88.1 ± 2.6 | 51.3 ± 5.2*# |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.02* | 0.35 ± 0.04*# |

| DLCO, % predicted | 78 ± 4 | 60 ± 7 | 36 ± 5*# |

| BODE index | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 7 ± 0*# |

| SGRQ total score | 20 ± 6 | 28 ± 6 | 63 ± 4*# |

| Emphysema score | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.3* | 2.7 ± 0.3*# |

Data are means ± SE. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD, the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; FVC, forced vital capacity; DLCO, diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide; SGRQ, the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire.

P < 0.05, compared with the never-smoker group;

P < 0.05, compared with the COPD GOLD 2 group.

Animals.

C3H/HeJ (Tlr4-mutated) mice and C57BL/10ScNJ (Tlr4-deficient) mice, and their respective controls, C3H/HeOuJ and C57BL/10SnJ, were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All animal experiment protocols were approved by the Harvard Standing Committee for Animal Welfare.

In vivo CS exposure.

Mice were exposed to CS (100 cigarettes/day for 5 days/wk) for a total of 2 mo (for Tlr4-mutated mice and their respective controls) or 6 mo (for Tlr4-deficient mice and their respective controls), using a total body CS exposure chamber as described (4, 5). Total body CS exposure was performed in a stainless-steel chamber (71 cm × 61 cm × 61 cm) using a smoking machine (model TE-10; Teague Enterprises). The smoking machine puffs each 3R4F cigarette for 2 s, for a total of nine puffs before ejection, at a flow rate of 1.05 l/min, providing a standard puff of 35 cm3. The smoke machine was adjusted to deliver 10 cigarettes at one time. The chamber atmosphere was periodically measured for total particulate matter and concentrations ranged from 100 to 120 mg/m3.

Lung morphometry.

Lung samples of mice were processed for morphometric analysis, and mean linear intercept (MLI) measurements were obtained using modified ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) as previously described (5, 7).

Immediately following necropsy, the right lung was inflated by gravity with 4% paraformaldehyde and held at a pressure of 30 cmH2O for 15 min. The left lung was removed and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen for subsequent protein studies. The right lung was gently dissected from the thorax and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for up to 8 h. The samples were cut parasagittally and embedded in paraffin. Modified Gills staining was performed and 12 random 1,300-pixel × 1,030-pixel images were acquired digitally for each lung sample using a light microscope (Axiophot; Carl Zeiss Micro-Imaging) equipped with a digital camera (Axiocam HRc; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) at ×200 magnification. Large airways, blood vessels, and other nonalveolar structures were manually removed from the images. Airspace enlargement was quantified using the MLI method (7, 29, 30). Both these indexes are known to increase with the onset of emphysema. MLI was measured using modified ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The ImageJ software program automatically thresholded the images, and a median filter, set to a two-pixel radius, was run to smooth the image edges. The software laid a line grid comprised of 1,353 lines with each line measuring 21 pixels over the individual images. The program then counted the number of lines that ended on or intercepted alveolar tissue. These data were used to calculate the volume of air, the volume of tissue, the surface area, the surface area-to-tissue volume ratio. The MLI, which assesses the degree of alveolar airspace enlargement, was calculated according to methods adapted from Dunhill as: 4 ÷ surface area-to-volume tissue ratio (7).

Cell culture.

The primary human bronchial epithelial cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and were cultured according to the ATCC prescription. Human lung bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells and alveolar epithelial A549 cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics.

Isolation of primary alveolar type II cells.

The primary alveolar type II (ATII) cells of mouse lung were obtained as previously described and used for experiments before passage (14). In brief, mice were anaesthetized, and the lungs were perfused with 20 ml of Ca2+/Mg2+-free phosphate buffered saline (PBS). 20-G intravenous catheter was inserted into the trachea. Dispase solution (2 ml; Gibco, Invitrogen) was infused through the tracheal catheter, and 1 ml of 1% low-melting agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) was slowly infused through the catheter. Immediately the lungs were covered with crushed ice and allowed to let stand for 2 min. The lungs were removed and transferred to 2 ml of dispase and incubated for an additional 45 min at room temperature. The lungs were transferred to 7 ml of DMEM with 0.01% DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) in a 60-mm culture plate. The digested lung tissue was teased and successively filtered through 100-, 40- and 20-μm cell strainers, and the pellet was saved after centrifugation (130 g for 8 min). The pellet was resuspended in complete medium (DMEM supplemented with 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin). The cell suspension was incubated with anti-CD16/32 (BD Biosciences) and anti-CD45 (BD Biosciences) for 1 h at 37°C. The unbound cells were collected and inoculated into noncoated culture plates for 4 h at 37°C. The cell suspension was harvested and centrifuged (130 g for 8 min). The pellet was resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics and inoculated to fibronectin-coated plates (BD Biosciences). ATII cells were subjected to experiments after confirmation of the purity > 95% by immunofluorescence staining for SP-C.

Air-liquid interface culture of primary alveolar type II cells.

For treatment of cells with mainstream CS, ATII cells were isolated from Tlr4-deficient mice and seeded onto transwells coated with a thin solution of 70% Matrigel and 30% collagen I in acetic acid. Cells were allowed to attach and proliferate for 72 h under submerged conditions, and then the apical media was removed to create an air-liquid interface (ALI) (16). Approximately 24 h following the establishment of ALI, the cells were exposed to 50 mg/m3 of total particulate matter from one cigarette for 10 min. Cell lysates were then harvested 24 h after CS exposure.

Lactate dehydrogenase release assay.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was measured using a commercially available assay (Cytotoxicity Detection Kit; Roche Molecular Biochemicals) (15). After gentle agitation, 200 μl of medium was removed at various times to be used for the assay. The samples were incubated for 30 min with buffer containing NAD+, lactate, and tetrazolium. LDH converts lactate to pyruvate generating NADH. The NADH then reduces tetrazolium (yellow) to formazan (red), which was detected by absorbance at 490 nm. Additionally, the percentage of cell death was determined by exclusion of Trypan Blue.

Preparation of CSE.

Aqueous CSE was prepared as previously described (4). Kentucky 3R4F research-reference filtered cigarettes (The Tobacco Research Institute, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY) were smoked by using a peristaltic pump (VWR International) as previously described (4). Before the preparation, the filters were cut from the cigarettes. Each cigarette was smoked in 6 min with a 17-mm butt remaining. Four cigarettes were bubbled through 40 ml of cell growth medium, and this solution, regarded as 100% strength CSE, was adjusted to a pH of 7.45 and used within 15 min after preparation.

siRNA transfection.

Human TLR4-siRNA was from Thermo Scientific. The siRNA was transfected into cells using the Xtreme transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science).

Immunoblotting and immunohistochemical staining.

Immunoblotting was performed essentially as previously described (4, 24). Antibodies against LC3B and β-actin were from Sigma. The anti-TLR4 and caspase-3 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Lung tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by immunohistochemical staining for anti-LC3B (Sigma). Briefly, fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated gradually with graded alcohol solutions, and then washed with deionized water. Sections were retrieved by Target Retrieval Solution (Dako). After incubation with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min, sections were blocked with blocking serum of Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) for 1 h, and incubated with anti-LC3B antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C overnight. Sections were incubated with biotinylated universal antibodies for 30 min and with Vectastain Elite ABC Reagent for 30 min at room temperature. DAB substrate solution of Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories) was applied to sections and counterstained with Hematoxylin QS (Vector Laboratories). After being washed with deionized water, sections were dehydrated gradually with graded alcohol solutions and immersed in xylene. Slide sections were mounted with Permount Mounting Medium (Fisher Scientific) and covered with cover glass.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue sections were subject to immunofluorescence staining with anti-TLR4 (Abcam), anti-LC3B (Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-SP-C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), as described previously (4, 24). Samples were viewed with an Olympus FluoView FV10i confocal laser scanning microscope.

Lipid peroxidation assays.

The left lung lobe was subject to measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) for quantification of lipid peroxidation (35). MDA assay was performed using a lipid peroxidation (MDA) assay kit (Abcam) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, lung tissue was homogenized on ice in 300 μl of the MDA lysis buffer with 3 μl butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) (×100) and then centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min. The 200 μl of supernatant was added to 600 μl of thiobarbituric acid and incubated at 95°C for 60 min. The samples were cooled to room temperature in an ice bath for 10 min, and absorbance (532 nm) was measured spectrophotometrically. Another product of lipid peroxidation, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), was detected by immunofluorescence staining with anti-4-HNE (Abcam).

Statistical analysis.

Results were expressed as means ± SE from at least three independent experiments. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the three groups of patients or four groups of mice, and Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare between groups. Categorical variables were analyzed by χ2 tests. Statistically significant difference was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

TLR4 is induced in patients with advanced stage of COPD in parallel with increased markers of autophagy and apoptosis. To examine the relationship between TLRs and the regulation of cell death in COPD, we obtained lung tissue sections of COPD patients from the Lung Tissue Research Consortium. COPD patients were classified at various stages of disease severity according to the guidelines of GOLD. The visual emphysema score was significantly increased according to the severity of emphysema (Table 1).

COPD patients at GOLD stage 2 or 4 (each n = 15), were analyzed for expression of TLR4, relative to control patients (never-smokers) (n = 5). The expression of TLR4 was significantly increased in COPD GOLD 4 lung tissue relative to lung tissue from GOLD 2 and never-smokers (Fig. 1A). To investigate lung cell death, the expression of cleaved caspase-3, one of the apoptotic indices, was measured. The expression of cleaved caspase-3 was significantly increased in the lungs of COPD GOLD 4 (n = 15) relative to that of never-smokers (n = 5) or COPD GOLD 2 patients (n = 15) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Toll-like receptors 4 (TLR4) is induced in patients with an advanced stage of chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) in parallel with increases in autophagic protein light-chain-3B (LC3B) and apoptosis. Human lung tissues of never-smokers and patients with COPD Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 2 (G2) and 4 (G4) were analyzed by Western blot analysis (n = 5 for never-smokers; n = 15 for patients with COPD GOLD stage 2; n = 15 for patients with COPD GOLD stage 4). Western blot analysis for TLR4 and cleaved caspase-3 were quantified for relative TLR4 (A), and cleaved caspase-3 (B) expression. β-Actin served as the standard. Data are means ± SE; *P < 0.05 compared with never-smoker; #P < 0.05 compared with previous group. Western blot analysis of LC3B was quantified for LC3B-II (C). β-Actin served as the standard. Data are means ± SE; *P < 0.05 compared with never-smoker; #P < 0.05 compared with previous group. D: representative images of human lung tissues with immunohistochemical staining for LC3B. E: immunofluorescence staining for TLR4 (red) and LC3B (green). Scale bar indicates 10 μm. F: immunofluorescence staining for TLR4 (red) and SP-C (green) as the marker of type II alveolar epithelial cells. DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Scale bar = 10 μm.

COPD patients at GOLD stage 2 or 4 (each n = 15), were also analyzed for expression of the autophagic protein LC3B, relative to control patients (never-smokers) (n = 5) (Fig. 1C).

In agreement with previous findings (4), the overall expression of LC3B was significantly increased in patients with COPD GOLD 2 and GOLD 4 compared with never-smokers. Densitometric analysis of Western blots revealed that the expression level of the active, lipidated form, LC3B-II, was significantly increased in GOLD 2 and GOLD 4 COPD patients relative to never-smokers (Fig. 1C).

Immunohistochemical staining indicated that LC3B expression was increased in the lungs from GOLD 2 and GOLD 4 COPD patients (Fig. 1D). Consistent with the immunoblotting results, confocal imaging revealed increased expression of LC3B in COPD GOLD 4 tissue relative to never-smokers (Fig. 1E). At GOLD stage 4, more cells displayed increased expression of both TLR4 and LC3B relative to never-smokers, as shown in the merged confocal images (Fig. 1E). SP-C positive ATII cells were identified among the cells which displayed increased expression of TLR4 (Fig. 1F).

In conclusion, the lungs of COPD GOLD 4 had a high level of expression of TLR4, LC3B-II and its conversion ratio, and cleaved caspase-3 than those of never-smoker or GOLD 2.

TLR4 regulates autophagic protein LC3B and apoptosis in CSE-treated epithelial cells.

We studied the effect of CS on TLRs expression in cultured epithelial cells. The expression levels of TLR4 and TLR2 were time-dependently increased in Beas-2B cells (Fig. 2A) and A549 cells (Fig. 2B) exposed to 20% CSE.

Fig. 2.

Increased TLR4 expression regulates autophagic protein LC3B and apoptosis in cigarette smoke-extract (CSE)-treated epithelial cells. A: Beas-2B cells were treated with CSE (20%) for the indicated times, and their cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis for TLR4 and TLR2. β-Actin served as the standard. B: A549 cells were treated with CSE (20%) for the indicated times, and their cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis for TLR4 and TLR2. β-Actin served as the standard. C: human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells were treated with CSE (10%) for the indicated times and their cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis for TLR4, LC3B, and cleaved caspase-3. β-Actin served as the standard. D: Beas-2B cells were treated with CSE (20%) for the indicated times and their cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis for TLR4 and LC3B. β-Actin served as the standard. E: Beas-2B cells were pretreated with control siRNA (CTL) or TLR4-siRNA (TLR4) for 48 h, followed by CSE (20%) treatment for 6 h. The lysates were then subjected to Western blot analysis as indicated. β-Actin served as the standard. F: primary alveolar type II (ATII) cells were isolated from C57BL/10ScNJ (Tlr4-deficient) and C57BL/10SnJ [wild-type (WT)] mice. ATII cells were exposed to CSE (20%) for 6 h and the lysates were immunoblotted for TLR4, LC3B, and cleaved caspase-3. β-Actin served as the standard. G: primary ATII cells were isolated from C57BL/10SnJ (WT) mice and cultured in air-liquid interface (ALI) state. ATII cells were exposed to 50 mg/m3 of total particulate matter from one cigarette for 10 min and the lysates were immunoblotted for TLR4 and LC3B. β-Actin served as the standard. H: ATII cells were treated with CSE (20%) for the indicated times, and the culture media was subjected to lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. Data represent means ± SE; *P < 0.05 compared with preceding day in same mouse group; #P < 0.05 compared with wild-type mice at same day.

Next, we studied the effect of CS on TLR4 expression and its relationship to markers of autophagy and apoptosis in cultured epithelial cells. The expression of TLR4 was induced in human bronchial epithelial cells after exposure of CSE (10%). Exposure to 10% CSE also increased the expression of LC3B and cleaved caspase-3 in these cells, in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). Similarly, the expression of TLR4 and LC3B were also increased in Beas-2B cells exposed to CSE (20%) in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2D).

To investigate the role of TLR4 in cellular responses to CSE, Beas-2B cells were pretreated with TLR4-siRNA or control siRNA and then treated with CSE (20%) for 6 h. The basal expression of LC3B was much higher in Beas-2B cells transfected with TLR4-siRNA than in cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 2E). Following exposure to CSE, the expression of LC3B was much higher in TLR4-siRNA transfected Beas-2B cells than in control siRNA (Fig. 2E).

To investigate the role of TLR4 in alveolar epithelial cells, primary ATII cells were isolated from C57BL/10ScNJ (Tlr4-deficient) mice and their corresponding C57BL/10SnJ (wild-type) mice, and then exposed to CSE (20%) for 6 h. The expression of TLR4 and LC3B were increased after CSE exposure in ATII cells of wild-type mice (Fig. 2F). The basal level of LC3B was much higher in ATII cells isolated from Tlr4-deficient mice compared with those from wild-type mice (Fig. 2F). LC3B expression was much higher in ATII cells of Tlr4-deficient mice compared with those of wild-type mice after CSE exposure (Fig. 2F). We also observed the expression of TLR4 and LC3B in ATII cells cultured at ALI and exposed to CS. The expression of TLR4 and LC3B were increased after CS exposure (Fig. 2G).

Similarly, the expression of cleaved caspase-3 increased after CSE exposure in wild-type cells and reached higher levels in ATII cells of Tlr4-deficient mice (Fig. 2F). To investigate the role of TLR4 in cell death, ATII cells were treated with CSE (20%) and then LDH release assays were performed. LDH activity was significantly increased with longer exposure to CSE in ATII cells of both wild-type and Tlr4-deficient mice. Significantly higher levels of LDH activity were observed in ATII cells of Tlr4-deficient mice compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 2H). These findings suggest that TLR exerts an inhibitory effect on the expression of the autophagic protein LC3B, and also on the apoptotic response to CSE.

TLR4-deficiency augments pulmonary emphysema in CS-exposed mice.

We next examined the role of TLR4 in susceptibility to cigarette-smoke induced emphysema in vivo, using mouse strains (i.e., C3H/HeJ, C56BL/10ScNJ) that are compromised for TLR4 function or expression, respectively.

C3H/HeOuJ (wild-type) mice showed significant increases in lung airspace after 2-mo CS exposure relative to air-treated controls as determined by measurements of MLI (Fig. 3A) and comparative histologic examination (Fig. 3B). C3H/HeJ (Tlr4-mutated) mice exposed to CS for 2 mo displayed marked increases in lung airspace after CS exposure relative to air-treated controls (Fig. 3, A and B). The Tlr4-mutated mice exhibited significant increases in airspace relative to wild-type mice after 2 mo of either CS- or air-exposure (Fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 3.

Pulmonary emphysema was augmented by exposure to CS in Tlr4-mutated or Tlr4-deficient mice. A: quantification of mean linear intercepts (MLIs) of C3H/HeOuJ (WT) and C3H/HeJ (Tlr4-mutated) mice exposed to CS for 2 mo. Data represent means ± SE; *P < 0.05 compared with air-exposed mice in the same strain; #P < 0.05 compared with WT mice with same exposure. B: representative images of lungs are shown with modified Gill's staining. C: quantification of MLIs of C56BL/10SnJ (WT) and C56BL/10ScNJ (Tlr4-deficient) mice exposed to CS for 6 mo. Data represent means ± SD; *P < 0.05 compared with air-exposed mice in the same strain; #P < 0.05 compared with WT mice with same exposure. D: representative images of lungs are shown with modified Gill's staining.

Wild-type C56BL/10SnJ mice displayed marked increases in lung airspace after 6-mo CS exposure relative to air-treated control as determined by measurements of MLI (Fig. 3C) and comparative histologic examination (Fig. 3D). Similarly, C56BL/10ScNJ (Tlr4-deficient) mice exposed to CS for 6 mo showed marked increases in lung airspace after CS exposure relative to air-treated controls (Fig. 3, C and D). The Tlr4-deficient mice exhibited significant increases in airspace relative to wild-type mice after either 6 mo CS exposure or air exposure (Fig. 3, C and D).

TLR4 regulates autophagic protein LC3B and apoptosis in vivo. we then investigated the effects of TLR4 on autophagy and apoptosis markers in CS-exposed mice.

In the C56BL/10ScNJ (Tlr4-deficient) mice, the basal expression of LC3B in the lungs was increased compared with that of C56BL/10SnJ (wild-type) mice after 6 mo air exposure (Fig. 4A). LC3B expression was increased in both wild-type and Tlr4-deficient mice strains after 6 mo CS exposure compared with air exposure with greater expression in the Tlr4-deficient mice (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, Tlr4-deficient mice exposed to CS displayed significant increases in the expression of cleaved caspase-3 relative to mice in other groups (Fig. 4B). Immunohistochemical staining showed increased expression of LC3B in CS-exposed mice lung relative to air-exposed lung, and in the lung of Tlr4-deficient mice relative to wild-type mice lung after air exposure (Fig. 4C). Confocal imaging of lungs revealed that basal expression of LC3B was increased in the lungs of air-exposed Tlr4-deficient mice compared with that of air-exposed wild-type mice (Fig. 4D). The expressions of TLR4 and LC3B in the lungs were increased after CS exposure compared with air exposure in wild-type mice lungs. Among the cells that expressed TLR4 in the lungs included SP-C positive ATII cells (Fig. 4E). LC3B expression was further increased in the lungs of CS-exposed Tlr4-deficient mice compared with air-exposed wild-type mice (Fig. 4D).

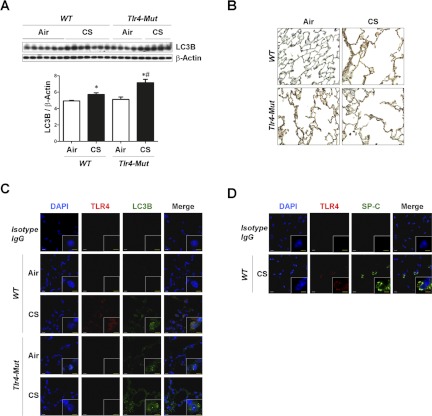

Fig. 4.

TLR4 regulates CS-induced autophagic protein LC3B and apoptosis in vivo. C57BL/10SnJ (WT) or C57BL/10ScNJ (Tlr4-deficient) mice were exposed to CS or air for 6 mo (C57BL/10SnJ, n = 6 for air, n = 5 for CS; C57BL/10ScNJ, n = 5 for air, n = 4 for CS). Western blot analysis and corresponding quantification for LC3B (A) and cleaved caspase-3 (B). Data are means ± SE; *P < 0.05 compared with air-exposure group in the same strain; #P < 0.05 compared with WT mice with same exposure. C: representative images of immunohistochemical staining for LC3B in mouse lung tissues. D: immunofluorescence staining for TLR4 (red) and LC3B (green) in mouse lung tissues. E: immunofluorescence staining for TLR4 (red) and SP-C (green) as a marker of ATII cells in mouse lung tissues. White scale bar = 10 μm; yellow scale bar = 5 μm. F: lipid peroxidation [malondialdehyde (MDA)] assay of homogenates of lung tissues. Data are means ± SE; *P < 0.05 compared with air-exposure group in the same strain; #P < 0.05 compared with WT mice with same exposure. G: immunofluorescence staining for 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) (red) as a marker of lipid peroxidation in mouse lung tissues. Blue indicates DAPI stain for nuclear staining.

We next determined lung oxidative stress as a function of TLR4 phenotype and CS exposure, by monitoring lipid peroxidation end products in the lung. Malondialdehyde (MDA) was significantly increased with exposure to CS in both wild-type and Tlr4-deficient mice. Interestingly, significantly higher levels of MDA were observed in lung of Tlr4-deficient mice compared with wild-type cells, in the absence or presence of CS exposure (Fig. 4F). Immunofluorescence analysis of 4-HNE, another byproduct of lipid peroxidation, showed similar results in lung tissue (Fig. 4G).

Similar but less pronounced effects were observed in C3H/HeJ (Tlr4-mutated) mice and their corresponding wild-type strain C3H/HeOuJ (wild-type) mice exposed to 2 mo CS exposure (Fig. 5). The expression of LC3B was increased after 2-mo CS exposure in both strains of mice. Tlr4-mutated mice showed enhanced expression of LC3B relative to wild-type mice following CS exposure by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5A). Immunohistochemical staining showed increased expression of LC3B in the lungs of CS-exposed mice compared with air-exposed lungs of both strains. Increased expression of LC3B was also evident in the lung of Tlr4-mutated mice compared with the lung of wild-type mice after exposure to air alone (Fig. 5B). Confocal imaging revealed that the basal expression of LC3B was elevated in the lungs of air-exposed Tlr4-mutated mice compared with that of air-exposed wild-type mice (Fig. 5C). Both strains exhibited a marked increase in the expression of LC3B in lungs in response to CS, though there was no apparent difference between the strains in this experiment (Fig. 5C). The expression of TLR4 was increased after CS exposure compared with air exposure in wild-type mice lungs (Fig. 5C). Increased TLR4 expression in the lungs was evident in cells that were SP-C positive (ATII cells) (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

C3H/HeOuJ (WT) or C3H/HeJ (Tlr4-mutated) mice were exposed to CS or air for 2 mo (C3H/HeOuJ, n = 6 for air, n = 6 for CS; C3H/HeJ, n = 5 for air, n = 5 for CS). Western blot analysis and its corresponding quantification (A) and immunohistochemical staining (B) for LC3B were performed in mouse lungs. Data represent means ± SE; *P < 0.05 compared with air-exposure group in the same strain; #P < 0.05 compared with WT mice with same exposure. C: immunofluorescence staining for TLR4 (red) and LC3B (green) in mouse lung tissues. D: immunofluorescence staining for TLR4 (red) and SP-C (green) as a marker of ATII cells in mouse lung tissues. White scale bar = 10 μm; yellow scale bar = 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate here, using a combination of in vitro and in vivo studies, that TLR4 exerts an important protective role with respect to CS-induced emphysema development, involving the dampening of the autophagic pathway.

Signaling pathways that regulate inflammatory processes are now known to participate in the molecular regulation of autophagy. In addition to classical signals such as nutrient starvation and energy depletion, several PAMPs have been found to activate autophagy (19). Recent studies suggest that TLRs, the primary cellular sensors for PAMPs, can regulate autophagy through the stimulation of downstream signaling pathways in macrophages and other cells types (19). For example TLR9 ligands (i.e., bacterial CpG motifs), can induce autophagy in rodent and human tumor cell lines (2). Furthermore, the TLR7 ligands, single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and imiquimod were found to be potent inducers of autophagy (6). Bacterial LPS, a TLR4 ligand, has been implicated in several studies as a stimulator of autophagic signaling in cultured macrophage cell lines (6, 32). The ability of LPS to induce autophagy in primary macrophages however, has been disputed (28). Our results in vitro using epithelial cells are consistent with a negative regulatory role for TLR4 on autophagy. We show here for the first time that TLR4 regulates autophagic protein-dependent emphysema during CS exposure. In epithelial cells subjected to TLR4 knockdown, as well as in primary epithelial cells isolated from Tlr4-deficient mice, we have observed elevated expression of the autophagic protein LC3B and increased markers of cell death in response to CS exposure, relative to control cells with wild-type TLR4 expression. We have recently shown that autophagic protein LC3B is involved not only in autophagy but also in extrinsic apoptosis during CS-induced lung cell death (22). The present results are consistent with a protective role for TLR4 and a pro-pathogenic role for LC3B in smoke-induced epithelial cell injury.

In the mouse, TLR4 has a role for maintaining normal lung architecture by inhibiting oxidant stress. Furthermore, TLR4 deficiency has been shown to cause age-related pulmonary emphysema by increased oxidant stress and cell death in aged mice, in the absence of smoking (34). In the present study, we have examined emphysema and markers of tissue injury in mice compromised for either TLR4 function (C3H/HeJ) or expression (C57BL/10ScNJ). The C3H/HeJ has a mutation in the TLR4 coding region that results in an amino acid substitution in TLR4 that compromises its function. In contrast, the C57BL/10ScNJ has mutations in the TLR4 gene that result in reduced mRNA and protein expression of TLR4. C57BL/10ScNJ and its control C57BL/10SnJ mice were exposed to long-term CS exposure (6 mo) or air. In our study, exposure to C57BL/10ScNJ for 6 mo resulted in an enhanced airspace enlargement, increased LC3B expression, and increased markers of apoptosis, relative to corresponding wild-type mice.

The C3H/HeJ strain is known to have slightly higher basal levels of airspace enlargement than the C57BL/6 stain (3), and their susceptibility to CS is also greater than the C57BL/6 strain (23). Due to increased sensitivity of this strain to CS exposure, we exposed this strain experimentally to 2 mo CS exposure. In C3H/HeJ mice, more emphysematous changes and increased expression of LC3B were seen after 2 mo exposure of CS, relative to their corresponding wild-type mice.

We speculate that the emphysema susceptibility of Tlr4-deficient or mutant strains may be due in part to an enhanced expression of LC3B and activation of the autophagic pathway in these strains. We have previously shown that LC3B−/− mice were resistant to CS-induced changes in airspace enlargement, despite an increase in basal airspace (4). We concluded that LC3B plays a role in CS-induced emphysema susceptibility, though we cannot exclude a critical role for this protein in basal lung development (4).

Our experiments in vitro show that TLR4, TLR2, and LC3B are upregulated by CSE in epithelial cells. One limitation of the CSE model is that it may not recapitulate all the elements of mainstream CS, in that short-lived radical species may be excluded. However, we have shown that mainstream CS exposure in ATII cells provided similar results as observed in epithelial cell cultures exposed to CSE.

Oxidative stress is one of the mechanisms underlying emphysematous changes in the lung in the animal models (34, 35). Both TLR4 deficiency alone (34) and cigarette smoking (35) have been associated with increased oxidative stress. Our study showed that the combined effect of TLR4 deficiency and CS-induced oxidative stress could aggravate emphysematous changes of the lung in animal models.

The mechanisms by which TLR4 regulate LC3B in this model remain unclear. Loss of TLR4 function may result in deregulation of signaling pathways involved in LC3B transcription and activation. Although we performed coimmunoprecipitation analysis, no evidence could be found for direct intermolecular interaction of TLR4 and LC3B in vitro or in vivo (data not shown). As autophagy in general, and LC3B expression in particular, are known to be regulated by oxidative stress, this may account for in part the increased basal LC3B expression and activation observed in the lungs of Tlr4-deficient mice.

Although TLR4 was studied in depth in this study, it cannot be excluded that other TLRs (e.g., TLR2) could also modulate LC3B activation. In the present study, we have demonstrated increased expression of TLR2 after CSE exposure in cultured epithelial cells with the same trend as TLR4. Further studies examining the role of other TLRs (e.g., TLR2) in CS-induced responses may be warranted.

Recently, several groups have proposed that one of roles of TLR4 in the stimulation of autophagy involves the upregulated expression of p62SQSTM1 (9, 17). Further analysis of p62SQSTM1 expression in Tlr4-deficient or mutant strains may be warranted.

We have observed that the expression of TLR4 was increased in the lungs of patients with COPD GOLD stage 4 (Fig. 1A). Markers of autophagy and apoptosis, i.e., LC3B and cleaved caspase-3 levels were elevated in COPD GOLD stage 4, relative to GOLD stage 2, and never-smoker controls. These studies suggest TLR4 expression as a possible histological marker of emphysematous tissue in humans. Our present studies show that expression of the autophagic marker LC3B, its lipidated form (LC3B-II), and the apoptotic marker cleaved caspase-3 are preferentially elevated at GOLD 4 stage. These observations are consistent with our previous findings in that these markers were elevated in COPD tissues relative to controls. These results, with respect to LC3B expression, differ from previous observations that indicated that LC3B was generally elevated in patients with COPD GOLD 0, 2, and GOLD 3/4 relative to current nonsmokers. The present sample set indicates a bias toward GOLD 4 for LC3B activation, and this set differs from that used in our previous studies (4), in that the control group was from a population of never-smokers, and furthermore that the COPD GOLD 4 class was clearly delineated from GOLD 3 (4).

In conclusion, our findings illustrate the importance of TLR4 in CS-induced pulmonary emphysema and may lead to new therapeutic strategies for COPD based on modulation of inflammatory signaling pathways.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01-HL-60234, R01-HL-55330, R01-HL-079904, R03-HL-097005, and a FAMRI Clinical Innovator Award (to A. M. K. Choi).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.H.A., X.M.W., and H.C.L. conception and design of research; C.H.A., X.M.W., H.C.L., and E.I. performed experiments; C.H.A., G.R.W., S.W.R., and A.M.K.C. analyzed data; C.H.A., S.W.R., and A.M.K.C. interpreted results of experiments; C.H.A., X.M.W., and S.W.R. prepared figures; C.H.A. and S.W.R. drafted manuscript; S.W.R. and A.M.K.C. edited and revised manuscript; A.M.K.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of X. M. Wang: Dept. of Pediatrics, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611.

REFERENCES

- 1. Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 343: 269–280, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertin A, Samson M, Pons C, Guigonis JM, Gavelli A, Baqué P, Brossette N, Pagnotta S, Ricci JE, Pierrefite-Carle V. Comparative proteomics study reveals that bacterial CpG motifs induce tumor cell autophagy in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Proteomics 7: 2311–2322, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bishai JM, Mitzner W. Effect of severe calorie restriction on the lung in two strains of mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L356–L362, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen ZH, Kim HP, Sciurba FC, Lee SJ, Feghali-Bostwick C, Stolz DB, Dhir R, Landreneau RJ, Schuchert MJ, Yousem SA, Nakahira K, Pilewski JM, Lee JS, Zhang Y, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Egr-1 regulates autophagy in cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 3: e3316, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen ZH, Lam HC, Jin Y, Kim HP, Cao J, Lee SJ, Ifedigbo E, Parameswaran H, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagy protein microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain-3B (LC3B) activates extrinsic apoptosis during cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18880–18885, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Delgado MA, Elmaoued RA, Davis AS, Kyei G, Deretic V. Toll-like receptors control autophagy. EMBO J 27: 1110–1121, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunhill MS. Quantitative methods in the study of pulmonary pathology. Thorax 17: 320–328, 1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ford ES, Mannino DM, Zhao G, Li C, Croft JB. Changes in mortality among United States adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in two national cohorts recruited during 1971 through 1975 and 1988 through 1994. Chest 141: 101–110, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fujita KI, Srinivasula SM. TLR4-mediated autophagy in macrophages is a p62-dependent type of selective autophagy of aggresome-like induced structures (ALIS). Autophagy 7: 552–554, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: NHLBI/WHO Workshop Report. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, (NIH publication no. 2701), 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goddard PR, Nicholson EM, Laszlo G, Watt I. Computed tomography in pulmonary emphysema. Clin Radiol 33: 379–387, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet 43: 67–93, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ 13: 816–825, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim HP, Chen ZH, Choi AM, Ryter SW. Analyzing autophagy in clinical tissues of lung and vascular diseases. Meth Enzymol 453: 197–216, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim HP, Wang X, Chen ZH, Lee SJ, Huang MH, Wang Y, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagic proteins regulate cigarette smoke-induced apoptosis: protective role of heme oxygenase-1. Autophagy 4: 887–895, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lam HC, Choi AM, Ryter SW. Isolation of mouse respiratory epithelial cells and exposure to experimental cigarette smoke at air liquid interface (Abstract). J Vis Exp 48: 2513, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee HM, Shin DM, Yuk JM, Shi G, Choi DK, Lee SH, Huang SM, Kim JM, Kim CD, Lee JH, Jo EK. Autophagy negatively regulates keratinocyte inflammatory responses via scaffolding protein p62/SQSTM1. J Immunol 186: 1248–1258, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell 6: 463–477, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy immunity and inflammation. Nature 469: 323–335, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990–2020. Nat Med 4: 1241–1243, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacNee W. Pulmonary and systemic oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2: 50–60, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 19: 5720–5728, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nadziejko C, Fang K, Bravo A, Gordon T. Susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in inbred strains of mice exposed to cigarette smoke. J Appl Physiol 102: 1780–1785, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Park JW, Kim HP, Lee SJ, Wang X, Wang Y, Ifedigbo E, Watkins SC, Ohba M, Ryter SW, Vyas YM, Choi AM. Protein kinase-Cα and -ζ differentially regulate death-inducing signaling complex formation in cigarette smoke extract-induced apoptosis. J Immunol 180: 4668–4678, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park KJ, Bergin CJ, Clausen JL. Quantitation of emphysema with three-dimensional CT densitometry: comparison with two-dimensional analysis, visual emphysema scores, and pulmonary function test results. Radiology 211: 541–547, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, Zielinski J, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 523–555, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ryter SW, Chen ZH, Kim HP, Choi AM. Autophagy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: homeostatic or pathogenic mechanism? Autophagy 5: 235–237, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saitoh T, Fujita N, Jang MH, Uematsu S, Yang BG, Satoh T, Omori H, Noda T, Yamamoto N, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Kawai T, Tsujimura T, Takeuchi O, Yoshimori T, Akira S. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1β production. Nature 456: 264–268, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tomkeieff SI. Linear intercepts, areas and volumes. Nature 155: 24, 1945 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weibel ER. Stereological Methods. London: Academic, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat Cell Biol 9: 1102–1109, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xu Y, Jagannath C, Liu XD, Sharafkhaneh A, Kolodziejska KE, Eissa NT. Toll-like receptor 4 is a sensor for autophagy associated with innate immunity. Immunity 27: 135–144, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yoshida T, Tuder RM. Pathobiology of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiol Rev 87: 1047–1082, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang X, Shan P, Jiang G, Cohn L, Lee PJ. Toll-like receptor 4 deficiency causes pulmonary emphysema. J Clin Invest 116: 3050–3059, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yao H, Edirisinghe I, Rajendrasozhan S, Yang SR, Caito S, Adenuga D, Rahman I. Cigarette smoke-mediated inflammatory and oxidative responses are strain-dependent in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L1174–L1186, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]