Abstract

Thyroid hormone (TH) is an essential regulator of both fetal development and energy homeostasis. Although the association between subclinical hypothyroidism and obesity has been well studied, a causal relationship has yet to be established. Using our well-characterized nonhuman primate model of excess nutrition, we sought to investigate whether maternal high-fat diet (HFD)-induced changes in TH homeostasis may underlie later in life development of metabolic disorders and obesity. Here, we show that in utero exposure to a maternal HFD is associated with alterations of the fetal thyroid axis. At the beginning of the third trimester, fetal free T4 levels are significantly decreased with HFD exposure compared with those of control diet-exposed offspring. Furthermore, transcription of the deiodinase, iodothyronine (DIO) genes, which help maintain thyroid homeostasis, are significantly (P < 0.05) disrupted in the fetal liver, thyroid, and hypothalamus. Genes involved in TH production are decreased (TRH, TSHR, TG, TPO, and SLC5A5) in hypothalamus and thyroid gland. In experiments designed to investigate the molecular underpinnings of these observations, we observe that the TH nuclear receptors and their downstream regulators are disrupted with maternal HFD exposure. In fetal liver, the expression of TH receptor β (THRB) is increased 1.9-fold (P = 0.012). Thorough analysis of the THRB promoter reveals a maternal diet-induced alteration in the fetal THRB histone code, alongside differential promoter occupancy of corepressors and coactivators. We speculate that maternal HFD exposure in utero may set the stage for later in life obesity through epigenomic modifications to the histone code, which modulates the fetal thyroid axis.

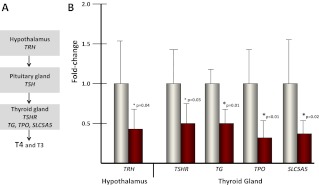

The role of thyroid hormone (TH) homeostasis in resting energy expenditure and the development of obesity has been studied for decades (reviewed in Ref. 1). Suitable TH levels help to regulate thermogenesis and are important for appetite and energy balance (2). Maintenance of TH levels depends on regulation by the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (see figure 3 below). The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus controls the release of tropic THs via the secretion of TRH, which acts on the anterior pituitary to regulate the synthesis and secretion of TSH. TSH is the primary peptide tropic hormone that regulates function of the thyroid gland, through activation of the TSH receptor (TSHR) (3). Activation of TSHR stimulates expression of TG, TPO (thyroid peroxidase), and SLC5A5, which are necessary the production of T4 and T3 in the thyroid gland (4, 5). Obesity is associated with alterations in TSH and free T4 (FT4) levels, as well as hyperleptinemia (1). Leptin, a 16-kDa peptide hormone secreted by adipose tissue, can directly stimulate neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus to release TRH, providing a feedback loop of stored energy status (6).

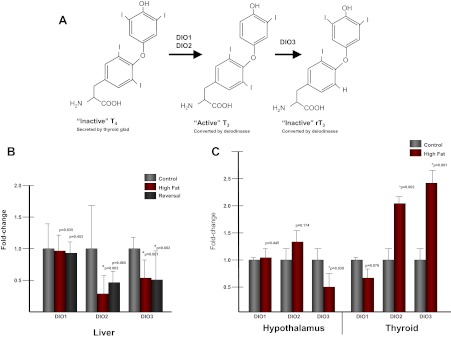

Although the thyroid gland secretes both T3 and T4, peripheral conversion of the prohormone T4 to the bioactive form T3 accounts for 80% of circulating T3 levels (7). Changes in local, tissue-specific thyroid levels are maintained through the actions of three deiodinase enzymes: deiodinase, iodothyronine (DIO)1, DIO2, and DIO3. DIO1 and DIO2 are deiodinases that can convert inactive T4 to active T3 within the cell (see figure 2 below) (7, 8). T3 can be inactivated through conversion to rT3 by DIO3 (8). Therefore, proper balance of deiodinase gene expression is necessary for TH homeostasis.

TH exerts its pleiotropic effects through binding and activation of two TH receptors (TRs) [TRα (THRΑ) and TRβ (THRΒ)] (9). Each receptor has splice variants resulting in distinct isoforms, and expression of each isoform is regulated in a tissue and developmental lineage-specific fashion (10). THRΒ is the major TR in the liver and is expressed in the later stages of development (11). Of the three isoforms of THRΑ, only THRA1 binds T3 (12). THRΑ1 is highly expressed in brain and at lower levels in the liver (11).

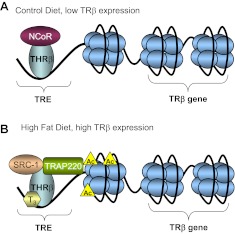

The TRs are DNA-binding proteins, which belong to the superfamily of ligand-activated nuclear receptors (NRs) and therefore can activate or repress thyroid-responsive genes depending on the presence or absence of TH (13, 14). Although the receptors are constitutively bound to thyroid response elements (TREs) within the promoter of thyroid-responsive genes (15), whether the gene is expressed or repressed depends on the presence or absence of T3 as well as TR association with either transcriptional activators or repressors (see figure 5 below). In the nonligand bound state, TRs repress thyroid-responsive gene expression through association with various corepressors, such as nuclear corepressor (NCOR) (16), Sin3-histone deacetylase complex (SIN3/HDAC), (17) NCOR2 (NCOR2 is also referred to an silencing mediator for retinoid or thyroid-hormone receptors, SMRT), (18), or HDAC3 (18). Upon binding to T3, TRs associate with transcriptional coactivators, such as CREB binding protein (CREBBP)/E1-binding protein 300 (EP300) (p300) (16), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, coactivator 1 α (PPARGC1A) (19), GATA2 (20), NCOA1 (nuclear receptor coactivator 1, SRC1) (21), and MED1 (mediator complex subunit 1, or TRAP220), (22). TR activation is associated with changes in histone acetylation surrounding the TRE (16) as well as alterations in localized chromatin structure (23). Interestingly, THRΒ is itself a thyroid-responsive gene, which contains a TRE (24, 25).

Although the thyroid gland is the first endocrine organ to develop in the primate fetus (∼5 wk in humans), TH production does not reach appreciable significance until around 20 wk (26). During the first trimester, fetal TH requirements must be met through maternal TH transfer through the placenta. In this critical developmental period, fetal FT4 is one third the level of maternal FT4 (27, 28). Importantly, even a modest reduction in maternal TH during the first trimester can lead to neurodevelopmental disorders in the offspring (29, 30). Therefore, it is of utmost importance for proper fetal development to maintain physiological TH levels. To prevent complete transfer of maternal THs to the fetus, the placenta has high expression levels of DIO3, which converts T3 to inactive rT3 (31).

There have been limited investigations as to the role of fetal TH levels in regulating metabolic programming in the developing fetus. We show here that we have used our primate model of maternal high-fat diet (HFD) exposure (32–34) to determine the relationship between maternal HFD intake, maternal obesity, and fetal TH homeostasis and gene regulation. We have observed decreased fetal FT4, as well as a decrease in genes required for T4 production, associated with exposure to a maternal HFD. We have observed that expression of the deiodinase genes is disrupted in fetal hypothalamus, liver, and thyroid gland tissue with HFD exposure. Moreover, up-regulation of THRB is associated with alterations in histone acetylation and occupancy of transcriptional repressors and activators within the THRB promoter. Taken together, these observations lead us to conclude that in utero exposure to a maternal HFD disrupts the fetal thyroid axis via altered epigenomic modifications, lending a potential causative link between fetal hypothryoidism and later in life risk of obesity in primates.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

All animal procedures were done in accordance with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of both Baylor College of Medicine and the Oregon National Primate Research Center, ONPRC as previously described (34). Young adult female Japanese macaques were bred and socially housed in indoor/outdoor enclosures in groups of five to nine with one to three males per group. The animals were either fed a control diet (standard monkey chow, 14% calories from fat, Monkey Diet no. 5052; LabDiet, Henderson, CO) or a HFD (32% calories from fat, Custom Diet 5A1F; TestDiet, Richmond, IN). The HFD was supplemented with calorically dense treats. Before our studies, the animals were fed a control diet in outdoor enclosures and were naive to any experimental exposures. During the fifth year of this study, diet reversal animals consumed control diet monkey chow during breeding and throughout gestation. Animals were allowed to breed naturally. All pregnancies were singleton gestations. Dams used in this study were between 6.5 and 13.5 yr old. For the dams used in this study, the control animals had one to nine previous pregnancies, the HFD animals one to seven, and the reversal between one and four previous pregnancies. The average age of the dams on the control diet is 8.95 yr, for the HF diet is 10.97 yr, and for the reversal is 9.61 yr. The weight range of the dams is as follows: control diet, 6.4–9.7 kg; HFD, 8.6–10.6 kg; and reversal, 6.4–9.8 kg. Pregnancies were terminated by cesarean section at gestational day 130 (G130) by ONPRC veterinarians. Fetal liver, anterior hypothalamus, and thyroid gland were harvested, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 C until use.

Thyroid-associated lab values

Maternal and fetal serum was obtained and sent to ARUP Laboratories (Salt Lake City, UT) for analysis. For each sample, free T3 (FT3), FT4, T3 uptake, and T4-binding globulin (TBG) levels were measured. A Student's two tailed t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Gene expression analysis of liver was performed using fetal control diet-exposed animals (n = 5), fetal HFD (n = 5), and diet reversal animals (n = 5). Gene expression analysis in the hypothalamus included control diet exposed (n = 4) and fetal HFD (n = 4). For expression analysis of the thyroid gland, n = 5 was used for each group. Genes for figures 2 and 4 below were first cloned from Japanese macaque, and mRNA was sequenced. The sequence was used to design primers and probes for expression analysis (Supplemental Table 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). Commercially available TaqMan primers and probes were used to analyze TG, TPO, SLC5A5, TRH, and TSHR. RNA was extracted from liver, hypothalamus, or thyroid gland using the NucleoSpin kit (Macherey Nagel, Bethlehem, PA). RNA was converted to cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR was performed for each sample in quadruplicate and repeated three times. Data are presented as a fold change in expression compared with control diet-exposed animals. The fold difference (delta delta CT) method was used for analysis (35).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and analysis

ChIP was performed as previously described (34) with the following modifications. For histone modifications, native ChIP was performed. Approximately 100 mg of frozen liver tissue from each animal (control, n = 5; high fat, n = 5) were used. Cells were lysed using a dounce homogenizer. Chromatin was digested using micronuclease (MNase) and quantified by nanodrop. Approximately 100 μg of chromatin were used for each immunoprecipitation. Ten percent of the reaction was saved before the addition of antibody as the input. A 1-h preclear using rabbit IgG was performed to reduce background. Five microliters of antibody were used per IP and incubated overnight with rotation at 4 C. Antibodies used were as follows: H3K18ac (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and H3K9,14ac (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). DNA was purified using QIAquick columns (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). For coactivators and corepressor ChIPs, a double cross-linking protocol was used. Fetal liver was cross-linked using 2 mm disuccinimidyl glutarate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) in PBS at room temperature for 45 min, followed by 15 min of cross-linking in 1% formaldehyde in PBS. Cross-linking was quenched with 0.125 m glycine. Cross-linking was reversed for 5 h at 65 C. Antibodies used were as follows: SRC-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), TRAP220 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), NCoR (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and THRΒ (Abcam).

Enrichment of promoter occupancy was determined using qPCR with the following primers: THRB TRE (5′-CAAGTCGGACAGCCGTGA-3′ and 5′-GGGCGCTGTCTTACTCC-3′) and intron (5′-CTGGTCCTCCTGTGTTCTGACT-3′ and 5′-CTTGGGGTTGGAGTATGAGAAG-3′). PCR was performed using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). To determine percent IP, samples were first normalized to the input for each sample. Percent IP was calculated as 100*2̂(Input-IP).

Results

HFD exposure in utero is associated with altered circulating fetal thyroid levels

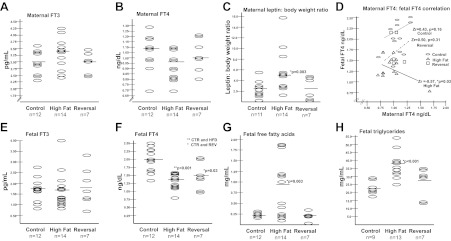

We tested thyroid function in both the mothers and offspring in our previously well-described nonhuman primate model of maternal HFD exposure (32–34). Briefly, Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata) dams are fed either a control (13% fat) or a high fat (35% fat) breeding diet for successive gestations, with a subset of the dams being switched to the control diet for breeding (diet reversal). Maternal and fetal FT3, FT4, T3 uptake, and TBG levels were measured in control, HFD, and diet reversal animals. Both maternal and fetal FT3 did not change by virtue of diet exposure (Fig. 1, A and E). Although maternal FT4 levels did not vary in any diet group (Fig. 1B), fetal FT4 is significantly decreased in the HFD-exposed offspring relative to control (Fig. 1F), which persists even after dietary reversal (obese dams fed a control diet). Because it has long been observed that TSH levels decline with weight loss in adults, and leptin levels appear to correlate with these declines, we corrected for increased maternal leptin to body weight ratio (Fig. 1C) and thereafter observed a significant correlation between maternal FT4 and fetal FT4 only in the HFD-exposed cohort (Fig. 1D). Uncorrected maternal serum leptin levels do not change significantly with HFD consumption (control, 27.3 ng/ml and HFD, 57.6 ng/ml; P = 0.11). Of note, the slope of the line after Fisher's z transformation is inversely related on maternal HFD, with a Zr = −0.57 (P = 0.03) (Fig. 1D). No changes were observed in fetal or maternal T3 uptake or TBG (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Fetal FT4, FFAs, and fetal triglycerides are disrupted with maternal HFD exposure in utero. Although maternal FT3 (A), FT4 (B), and fetal FT3 (E) are not changed, fetal FT4 is significantly reduced with HFD exposure (F). Correlation of maternal and fetal FT4 reveals that there is a significant inverse correlation only with HFD exposure (D) and not in the control or diet reversal groups. HFD exposure is also associated with an increased maternal leptin to body weight ratio (C), increased fetal FFAs (G), and increased fetal triglycerides (H).

Table 1.

Maternal and fetal TBG and T3 uptake are not altered with HFD exposure

| Control (n = 12) | High fat (n = 14) | Reversal (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal T3 uptake (%) | 37.45 ± 1.36 | 34.91 ± 4.28, P = 0.099 | 36.4 ± 1.34, P = 0.17 |

| Fetal TBG (μg/ml) | 8.564 ± 1.07 | 11.28 ± 8.58, P = 0.34 | 7.5 ± 1.11, P = 0.079 |

| Maternal T3 uptake (%) | 26.36 ± 1.63 | 27.18 ± 4.3, P = 0.566 | 26.86 ± 2.3, P = 0.604 |

| Maternal TBG (μg/ml) | 35.52 ± 6.39 | 30.00 ± 8.66, P = 0.105 | 36.01 ± 7.32, P = 0.881 |

Both fetal and maternal TBG levels and T3 uptake were measured for the three diet groups. We found that neither TBG nor T3 uptake is altered in any diet group when compared with control.

Because hypothyroidism is associated with hyperlipidemia, (36), and FT4 levels are inversely correlated with triglyceride levels (37), we similarly measured fetal free fatty acids (FFAs) and triglyceride levels. Not surprisingly, in utero exposure to a HFD is associated with a significant increase in both FFA (Fig. 1G) and triglyceride levels (Fig. 1H). This association is not observed in the diet reversal group, which has FFA and triglyceride levels similar to that of control diet-exposed animals.

Fetal hepatic, anterior hypothalamic, and thyroid gland deiodinase gene expression is dysregulated after maternal HFD exposure

Alterations in tissue-specific levels of TH are achieved via the action of three deiodinases: DIO1 and DIO2 convert T4 to T3 and DIO3 inactivates active T3 (Fig. 2A). We examined expression of each deiodinase gene in fetal liver from each of our cohorts. Although we did not observe any change in hepatic DIO1 levels, both DIO2 and DIO3 were decreased in HFD-exposed animals relative to control (Fig. 2B). Among the dietary reversal cohort offspring, hepatic DIO2 was no longer significantly different from control, whereas DIO3 transcription was persistently diminished (Fig. 2B). Because the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis is essential in maintaining proper TH levels, we sought to determine whether the deiodinase genes were altered with HFD exposure in either the anterior hypothalamus or the thyroid gland. We determined that, in the hypothalamus, only DIO3 levels were significantly decreased (0.54-fold, P = 0.039) in HFD-exposed offspring. Furthermore, in the thyroid gland, both DIO2 (2.1-fold, P = 0.002) and DIO3 (2.4-fold, P = 0.001) are up-regulated with HFD exposure compared with control (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

DIO2 and DIO3 levels are altered with exposure to a maternal HFD. A, TH homeostasis is maintained through the action of the deiodinase genes. The thyroid gland secretes the inactive prohormone T4, which must be converted to the bioactive T3 through the activity of the deiodinase enzymes DIO1 and DIO2. Through the activity of DIO3, T3 can be inactivated by conversion to rT3. B, Levels of DIO1, DIO2, and DIO3 were measured in fetal liver in control, HFD, and diet reversal-exposed animals. Although DIO1 levels remained unchanged in the three groups tested, both DIO2 and DIO3 are significantly decreased in both HFD and diet reversal groups compared with control (n = 5/group). C, Levels of DIO1, DIO2, and DIO3 were measured in both anterior hypothalamus and the thyroid gland in both control- and HFD-exposed animals. Although DIO3 was significantly down-regulated in the hypothalamus with HFD exposure, both DIO2 and DIO3 were up-regulated in the thyroid gland (n = 5/group).

Genes necessary for TH production are down-regulated in the fetal hypothalamus and thyroid gland with maternal HFD exposure

Proper circulating levels of THs are maintained by the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (Fig. 3A). TRH produced and secreted by the hypothalamus stimulates the pituitary gland's production of TSH. Analysis of TRH levels within the hypothalamus reveals that HFD exposure is associated with a reduction in expression compared with control diet-exposed animals (0.41-fold, P = 0.04) (Fig. 3B). Analysis of genes involved in TH production in the thyroid gland revealed a similar decrease in expression with HFD exposure. Expression of the receptor that binds TSH and initiates downstream transcription, TSHR, is reduced with HFD exposure (0.50-fold, P = 0.03) (Fig. 3B). Genes that act downstream of TSHR and are involved in T4 production are also reduced with HFD exposure compared with control diet (TG: 0.56-fold, P = 0.01; TPO: 0.24-fold, P < 0.01; and SLC5A5: 0.28-fold, P = 0.02) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Genes necessary for T4 production are reduced with maternal HFD exposure. A, The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis coordinates TH production. TRH released from the hypothalamus stimulates TSH production from the pituitary gland. TSH is bound by the TSHR in the thyroid gland, which activates the downstream genes necessary for TH production and release (TG, TPO, and SLC5A5). B, Levels of genes in the HPT axis are decreased with HFD exposure in the hypothalamus and the thyroid gland (n = 4/group).

Maternal HFD exposure alters expression of NRs, downstream mediators of TH, and TH-responsive genes

The biological activities of TH are mediated by NRs generated from the TΗRΑ and THRΒ loci, and TH functions as a transactivator via direct binding to the NR THRΑ isoform 1 and THRΒ. We used qPCR to measure transcript levels of both TRs in liver, hypothalamus, and thyroid gland (Fig. 4, A–C). Although THRΒ is the predominant hepatic TR, we observed both THRΑ1 (1.76-fold, P < 0.001) and THRΒ (1.9-fold, P = 0.012) to be significantly increase in fetal liver after HFD exposure. In the hypothalamus, THRΑ1 is the predominant TR, and hypothalamic THRΑ1 was significantly increased (1.21-fold, P = 0.006), whereas there was no significant change in THRΒ. Expression of ΤΗRΑ1 or ΤΗRΒ was not altered significantly in the fetal thyroid gland.

Fig. 4.

Expression of TRs and their associated genes is altered with HFD exposure. A, Expression of the thyroid-associated genes was assayed in fetal liver. Both TRs (THRΑ1 and THRΒ) were up-regulated with HFD exposure. Their associated genes, MED1, GATA2, PPARGC1A, SPOT14, and ACTA1, were also up-regulated with HFD exposure (n = 5/group). B, In the anterior hypothalamus, THRΑ1 expression is significantly up-regulated with HFD exposure (n = 5/group). C, In the thyroid gland, PPARGC1A is significantly down-regulated with HFD exposure (n = 5/group).

We also sought to determine whether coactivators or other downstream mediators of TH were altered by virtue of maternal diet exposure. We examined the transcript levels of MED1, GATA2, and PPARGC1A in all three tissues (Fig. 4, A–C). In fetal liver, a significant increase in all three genes occurred with HFD exposure (Fig. 4A), whereas no significant differences in transcription was observed in the hypothalamus (Fig. 4B). Analysis of gene expression in the fetal thyroid gland revealed that PPARGC1A levels are significantly reduced (0.21-fold, P = 0.002) with HFD exposure (Fig. 4C).

We also sought to determine whether genes that are regulated by TH are altered in fetal liver. SPOT14 is a well-characterized thyroid-responsive gene (38). SPOT14 is required to increase the expression of lipogenic genes in response to TH and is itself a TH-response gene (38, 39). We found that SPOT14 is highly up-regulated (4.3-fold, P = 0.01) in fetal liver with HFD exposure (Fig. 4A). ACTA1, another gene reported to be regulated by TH in the liver (39), was also up-regulated (1.74-fold, P = 0.026) with HFD exposure (Fig. 4A).

HFD exposure is associated with altered promoter occupancy of fetal hepatic THRΒ

The THRΒ promoter contains a TRE, and its expression is increased in the presence of TH (Fig. 5A). Because ligands for NRs facilitate the exchange of corepressors for coactivators, leading to chromatin modifications that favor the activation of gene transcription, we sought to interrogate the occupancy of the TRE within the THRΒ promoter using ChIP. We report that the TRE of THRΒ is associated with an increase in diacetylation of histone H3 at lysines 9 and 14 (H3K9,14ac) (Fig. 5B), whereas acetylation of H3K18 does not show a significant difference by virtue of maternal HFD exposure.

Fig. 5.

HFD exposure is associated with altered promoter occupancy of the hepatic THRΒ promoter. A, The TRE of thyroid-response genes is constitutively bound by TR. In the absence of T3, the gene is repressed through association with nuclear corepressors, such as NCOR1, NCOR2, and HDACs. Upon activation in the presence of T3, the receptors associate with coactivators, such as EP300, MED1, and NCOA1. Gene activation is also associated with hyperacetylation of the promoter. B, The TRE of THRΒ is associated with an increase in the diacetylation of lysines 9 and 14 of histone H3. ChIP with antibodies specific for H3K9,14ac and H3K18ac were used to determine occupancy of the TRE of THRΒ. Enrichment within an intron of the THRΒ gene was analyzed to serve as a control; n = 5/group. C, The TRE of THRΒ is associated with a decrease in the corepressor NCOR1 and an increase in the coactivators NCOA1 and MED1 with HFD exposure in the fetal liver; n = 5/group.

We sought to further interrogate the occupancy of corepressors and coactivators of the TRE within the THRB promoter. We observed increased occupancy of both MED1 and NCOA1 in the HFD-exposed offspring, whereas occupancy of THRΒ remained the same (Fig. 5C). We also interrogated the occupancy of the nuclear corepressor, NCOR1, within the TRE of THRΒ. Levels of NCOR1 were higher in the TRE of control diet-exposed animals than in HFD exposed, which corresponds with the lower levels of transcription of the THRΒ gene.

Discussion

Given the growing body of evidence that many chronic, noncommunicable diseases have their origins in fetal life, understanding the in utero factors that impact fetal metabolism and development are among the most important public health issues of our time. Data from our laboratory and others collectively suggest that fetal reprogramming of metabolic and developmental gene expression pathways occur via stable modification of the epigenome (33, 34). However, it remains a fundamental question in the field whether and how the fetal epigenome varies in response to maternal phenotype and diet modifications and if it is predictive of later in life disease states such as obesity and potentially associated secondary morbidities. The long-term consequences to the fetus by virtue of exposure to a maternal HFD are only beginning to be understood (40).

Here, we report a significant change in fetal FT4 associated with exposure to a maternal HFD in our nonhuman primate model. Thorough analysis of thyroid related clinical values in both the mother and fetus revealed that, although FT4 is not altered between mothers on a control diet vs. a HFD, the fetus shows a significant decrease with HFD exposure. Although TSH measurements would be ideal for a complete picture of TH homeostasis, no available assay tested was able to cross-react and detect TSH from Japanese macaque. However, analysis of TRH expression in the hypothalamus and genes in the thyroid gland necessary for TH production corroborate our finding of reduced fetal FT4 and further support our conclusion that the fetal thyroid axis is disrupted with HFD exposure.

The finding that there was no change in fetal FT3 was unexpected given the discovery that genes necessary for T3 and T4 production are decreased in the hypothalamus and thyroid gland. We hypothesized that if FT4 is altered with HFD exposure and FT3 is not, that the deiodinase genes must also be altered to compensate to keep serum FT3 levels steady. We measured DIO1, DIO2, and DIO3 transcript levels in fetal liver, anterior hypothalamus, and the thyroid gland and found that, although DIO1 levels remain unchanged in all three tissues, DIO2 and DIO3 are altered with HFD exposure. Although DIO1 is the predominant deiodinase in liver, our data are in line with the results from human subjects. DIO2 and DIO3 transcription were previously reported to be significantly decreased in liver biopsies from obese human subjects (41). We conclude that HFD exposure is associated with a disruption of FT4 levels as well as transcription of the enzymes, which help to maintain TH homeostasis in at least three different tissues in the fetus.

Because TH is a potent regulator of gene expression through interactions with TR, we sought to determine whether genes associated with TH were disrupted with HFD exposure. Because changes in transcription factors could lead to profound changes in downstream gene expression, we first focused on the transcription levels of the TRs themselves. Both THRΒ and THRΑ1 bind TH to initiate transcription of thyroid-responsive genes. We found that expression of TH-associated genes in the liver revealed the most significant changes compared with those in the hypothalamus and thyroid gland.

We have previously found that the liver is sensitive to the effects of a maternal HFD. At the beginning of the third trimester, HFD-exposed animals showed the pathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, as seen by increased Oil Red O staining, as well as signs of oxidative stress, inflammation, and increased triglyceride accumulation (32). These changes persist postnatally (32). We have reported changes in hepatic histone modifications (33) and the expression of circadian-regulated genes in the liver (34). Considering the diverse changes that we have observed in fetal liver, as well as the changes in TH-associated genes expression, we sought to determine the molecular mechanisms behind these changes.

Of particular interest was the increase in THRΒ gene expression in the fetal liver. THRΒ is the major TR in the liver and is responsible for the expression of TH-response genes. Based on current understandings of NR biology, we hypothesized that changes in expression of this transcriptional regulator would be associated with epigenomic modifications (23, 42). We have previously reported that exposure to a maternal HFD significantly and specifically modifies acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 14, (33) and that this modification is enriched within the NPAS2 promoter region in HFD-exposed fetal liver (34). Therefore, we sought to determine whether the THRB promoter was similarly associated with changes in histone acetylation. Using ChIP, we investigated the occupancy of acetylated histone H3 within the TRE of the THRΒ gene. Because the histone acetyltransferase, EP300, is recruited to the promoter of thyroid-response genes and is responsible for H3K18 acetylation, we investigated whether H3K18ac is differentially enriched at the TRE in HFD-exposed animals compared with control diet-exposed animals. We did not find a significant change between the two groups. However, using an antibody specific for H3K9,14 diacetylation, we demonstrated that there was an increase in this modification within the TRE in the HFD-exposed fetal liver compared with control diet. Because histone acetylation is generally associated with increased gene expression, this correlates with the higher levels of THRΒ expression seen in the HFD-exposed animals.

In an effort to further characterize the THRΒ promoter in control and HFD-exposed animals, we investigated the differential recruitment of corepressors and coactivators between the two groups. THRΒ remains bound to the TRE of thyroid-response genes in both the presence and absence of TH (Fig. 5A). In the active state, THRΒ is associated with the coactivators MED1 and NCOA1. We hypothesized that because THRΒ expression and H3K9,14ac occupancy is increased in HFD-exposed offspring, there would be differential occupancy of the coactivators, whereas THRΒ occupancy would remain relatively stable. We found that NCOR1 occupancy was increased in control diet-exposed animals compared with that of control, whereas THRB occupancy remained the same between the two groups as expected. We further hypothesized that, in the HFD-exposed group, there would be an increase in the association of coactivators. We found that both NCOA1 and MED1 show an increase in promoter occupancy of the TRE in HFD-exposed animals compared with control diet exposure.

Although fetal FT4 levels are decreased, we see an increase in TH-response genes in the fetal liver. We speculate that this could be due to the down-regulation of DIO3 in the fetal liver, which is regulating bioavailable FT3 to this tissue. Decreased DIO3 may lead to less FT3 and FT4 being “inactivated” (i.e. metabolized to rT3) in this tissue, allowing for these TH-response genes to increase with HFD exposure. Furthermore, an increase in THRB could contribute to increased expression of downstream, TRE-containing genes. Although we have only interrogated the THRB promoter, we speculate that other promoters may be epigenetically altered in the HFD-exposed animals, perhaps leading to an increased sensitivity to TH in the presence of reduced FT4.

In summary, our results reveal an alteration of the fetal thyroid axis associated with in utero exposure to a maternal HFD. At the beginning of the third trimester, the transcriptional levels of genes necessary for TH production (TRH, TSHR, TG, TPO, and SLC5A5) are decreased in the hypothalamus and thyroid gland. Concomitant with a decrease in these genes, we find decreased fetal FT4 as well. Furthermore, we find a disruption in the genes that help maintain thyroid homeostasis at the tissue-specific level (DIO genes) in three fetal tissues tested (liver, thyroid, and hypothalamus). Importantly, we provide a mechanistic insight into the increased level of THRΒ seen in the fetal liver. Thorough analysis of the THRΒ promoter reveals an altered histone code with HFD exposure, as well as differential promoter occupancy of corepressors and activators between the two groups (Fig. 6). We conclude that the deleterious effects of exposure to a maternal HFD in utero include transcriptional and epigenetic alterations of the fetal thyroid axis.

Fig. 6.

The TRE of THRΒ is enriched for histone acetylation and coactivators with HFD exposure in utero. A, In control diet-exposed animals, the THRΒ promoter is enriched for the nuclear corepressor NCOR1 and has significantly less histone H3K9,14 acetylation than HFD-exposed animals. B, In fetal liver exposed to the maternal HFD, the TRE of THRΒ is enriched with the coactivators MED1 and NCOA1 as well as histone H3K9,14 acetylation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the helpful comments of members of the Aagaard and Hawkin's labs at Baylor College of Medicine and Diana Takahashi for coordination of sample acquisition.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director New Innovator Award DP2120OD001500-01 (to K.M.A.), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01DK080558-01 (to R.H.L. and K.M.A.), DK79194 (to K.L.G.), and R000163 (to K.L.G.), and the NIH REACH IRACDA K12 GM084897 (to M.A.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ChIP

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DIO

- deiodinase, iodothyronine

- EP300

- E1-binding protein 300

- FFA

- free fatty acid

- FT3

- free T3

- FT4

- free T4

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- NCOR

- nuclear corepressor

- NR

- nuclear receptor

- PPARGC1A

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, coactivator 1α

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- SIN3/HDAC

- Sin3-histone deacetylase complex

- TBG

- T4-binding globulin

- TG

- thyroglobulin

- TH

- thyroid hormone

- THRΑ

- TRα

- THRΒ

- TRβ

- TR

- TH receptor

- TPO

- thyroid peroxidase

- TRE

- thyroid response element

- TSHR

- TSH receptor.

References

- 1. Reinehr T. 2010. Obesity and thyroid function. Mol Cell Endocrinol 316:165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Herwig A, Ross AW, Nilaweera KN, Morgan PJ, Barrett P. 2008. Hypothalamic thyroid hormone in energy balance regulation. Obes Facts 1:71–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davies TF, Yin X, Latif R. 2010. The genetics of the thyroid stimulating hormone receptor: history and relevance. Thyroid 20:727–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nillni EA. 2010. Regulation of the hypothalamic thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) neuron by neuronal and peripheral inputs. Front Neuroendocrinol 31:134–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suzuki K, Mori A, Lavaroni S, Ulianich L, Miyagi E, Saito J, Nakazato M, Pietrarelli M, Shafran N, Grassadonia A, Kim WB, Consiglio E, Formisano S, Kohn LD. 1999. Thyroglobulin regulates follicular function and heterogeneity by suppressing thyroid-specific gene expression. Biochimie 81:329–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guo F, Bakal K, Minokoshi Y, Hollenberg AN. 2004. Leptin signaling targets the thyrotropin-releasing hormone gene promoter in vivo. Endocrinology 145:2221–2227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maia AL, Goemann IM, Meyer EL, Wajner SM. 2011. Deiodinases: the balance of thyroid hormone: type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase in human physiology and disease. J Endocrinol 209:283–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bianco AC. 2011. Minireview: cracking the metabolic code for thyroid hormone signaling. Endocrinology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu Y, Koenig RJ. 2000. Gene regulation by thyroid hormone. Trends Endocrinol Metab 11:207–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. 2010. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev 31:139–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams GR. 2000. Cloning and characterization of two novel thyroid hormone receptor β isoforms. Mol Cell Biol 20:8329–8342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitsuhashi T, Tennyson GE, Nikodem VM. 1988. Alternative splicing generates messages encoding rat c-erbA proteins that do not bind thyroid hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:5804–5808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brent GA, Dunn MK, Harney JW, Gulick T, Larsen PR, Moore DD. 1989. Thyroid hormone aporeceptor represses T3-inducible promoters and blocks activity of the retinoic acid receptor. New Biol 1:329–336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glass CK, Lipkin SM, Devary OV, Rosenfeld MG. 1989. Positive and negative regulation of gene transcription by a retinoic acid-thyroid hormone receptor heterodimer. Cell 59:697–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Casanova J, Horowitz ZD, Copp RP, McIntyre WR, Pascual A, Samuels HH. 1984. Photoaffinity labeling of thyroid hormone nuclear receptors. Influence of n-butyrate and analysis of the half-lives of the 57,000 and 47,000 molecular weight receptor forms. J Biol Chem 259:12084–12091 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Havis E, Sachs LM, Demeneix BA. 2003. Metamorphic T3-response genes have specific co-regulator requirements. EMBO Rep 4:883–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jones PL, Sachs LM, Rouse N, Wade PA, Shi YB. 2001. Multiple N-CoR complexes contain distinct histone deacetylases. J Biol Chem 276:8807–8811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jeyakumar M, Liu XF, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Bagchi MK. 2007. Phosphorylation of thyroid hormone receptor-associated nuclear receptor corepressor holocomplex by the DNA-dependent protein kinase enhances its histone deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem 282:9312–9322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. 1998. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92:829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsushita A, Sasaki S, Kashiwabara Y, Nagayama K, Ohba K, Iwaki H, Misawa H, Ishizuka K, Nakamura H. 2007. Essential role of GATA2 in the negative regulation of thyrotropin β gene by thyroid hormone and its receptors. Mol Endocrinol 21:865–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lazar MA. 1993. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev 14:184–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ito M, Yuan CX, Malik S, Gu W, Fondell JD, Yamamura S, Fu ZY, Zhang X, Qin J, Roeder RG. 1999. Identity between TRAP and SMCC complexes indicates novel pathways for the function of nuclear receptors and diverse mammalian activators. Mol Cell 3:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong J, Shi YB, Wolffe AP. 1995. A role for nucleosome assembly in both silencing and activation of the Xenopus TR β A gene by the thyroid hormone receptor. Genes Dev 9:2696–2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ranjan M, Wong J, Shi YB. 1994. Transcriptional repression of Xenopus TR β gene is mediated by a thyroid hormone response element located near the start site. J Biol Chem 269:24699–24705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suzuki S, Miyamoto T, Opsahl A, Sakurai A, DeGroot LJ. 1994. Two thyroid hormone response elements are present in the promoter of human thyroid hormone receptor β 1. Mol Endocrinol 8:305–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Obregon MJ, Calvo RM, Del Rey FE, de Escobar GM. 2007. Ontogenesis of thyroid function and interactions with maternal function. Endocr Dev 10:86–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Calvo RM, Jauniaux E, Gulbis B, Asunción M, Gervy C, Contempré B, Morreale de Escobar G. 2002. Fetal tissues are exposed to biologically relevant free thyroxine concentrations during early phases of development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1768–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hume R, Simpson J, Delahunty C, van Toor H, Wu SY, Williams FL, Visser TJ. 2004. Human fetal and cord serum thyroid hormones: developmental trends and interrelationships. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:4097–4103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li Y, Shan Z, Teng W, Yu X, Fan C, Teng X, Guo R, Wang H, Li J, Chen Y, Wang W, Chawinga M, Zhang L, Yang L, Zhao Y, Hua T. 2010. Abnormalities of maternal thyroid function during pregnancy affect neuropsychological development of their children at 25–30 months. Clin Endocrinol 72:825–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, Williams JR, Knight GJ, Gagnon J, O'Heir CE, Mitchell ML, Hermos RJ, Waisbren SE, Faix JD, Klein RZ. 1999. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med 341:549–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roti E, Gnudi A, Braverman LE. 1983. The placental transport, synthesis and metabolism of hormones and drugs which affect thyroid function. Endocr Rev 4:131–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McCurdy CE, Bishop JM, Williams SM, Grayson BE, Smith MS, Friedman JE, Grove KL. 2009. Maternal high-fat diet triggers lipotoxicity in the fetal livers of nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest 119:323–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aagaard-Tillery KM, Grove K, Bishop J, Ke X, Fu Q, McKnight R, Lane RH. 2008. Developmental origins of disease and determinants of chromatin structure: maternal diet modifies the primate fetal epigenome. J Mol Endocrinol 41:91–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suter M, Bocock P, Showalter L, Hu M, Shope C, McKnight R, Grove K, Lane R, Aagaard-Tillery K. 2011. Epigenomics: maternal high-fat diet exposure in utero disrupts peripheral circadian gene expression in nonhuman primates. FASEB J 25:714–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2([minusΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Brien T, Dinneen SF, O'Brien PC, Palumbo PJ. 1993. Hyperlipidemia in patients with primary and secondary hypothyroidism. Mayo Clin Proc 68:860–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nader NS, Bahn RS, Johnson MD, Weaver AL, Singh R, Kumar S. 2010. Relationships between thyroid function and lipid status or insulin resistance in a pediatric population. Thyroid 20:1333–1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Campbell MC, Anderson GW, Mariash CN. 2003. Human spot 14 glucose and thyroid hormone response: characterization and thyroid hormone response element identification. Endocrinology 144:5242–5248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Feng X, Jiang Y, Meltzer P, Yen PM. 2000. Thyroid hormone regulation of hepatic genes in vivo detected by complementary DNA microarray. Mol Endocrinol 14:947–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Suter MA, Aagaard-Tillery KM. 2009. Environmental influences on epigenetic profiles. Semin Reprod Med 27:380–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pihlajamäki J, Boes T, Kim EY, Dearie F, Kim BW, Schroeder J, Mun E, Nasser I, Park PJ, Bianco AC, Goldfine AB, Patti ME. 2009. Thyroid hormone-related regulation of gene expression in human fatty liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3521–3529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wiench M, Miranda TB, Hager GL. 2011. Control of nuclear receptor function by local chromatin structure. FEBS J 278:2211–2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.