Abstract

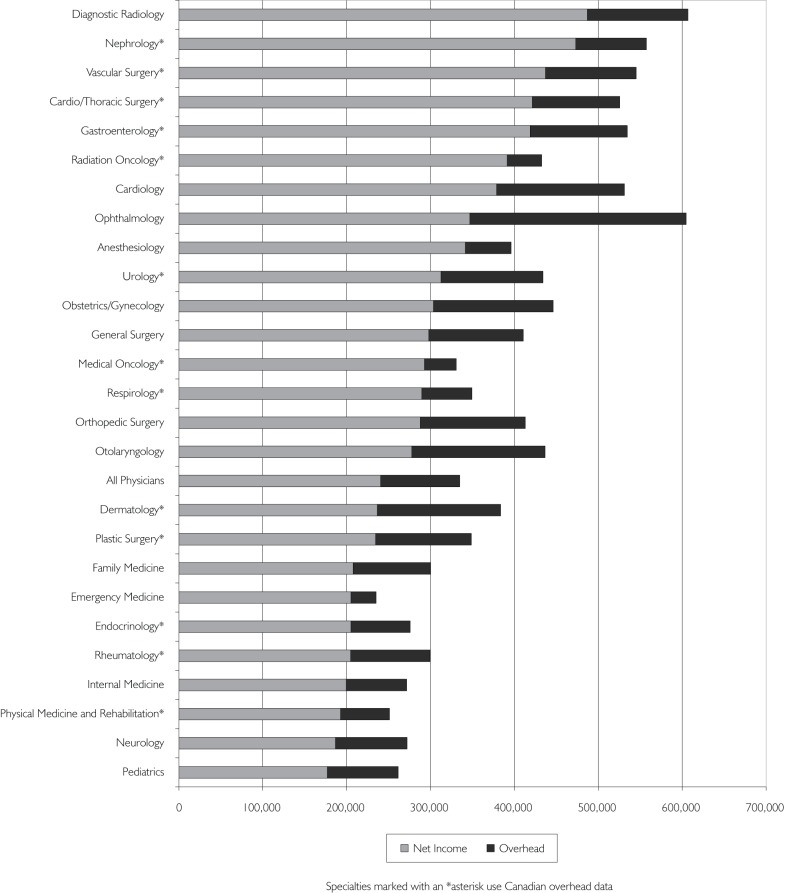

We used data collected in the 2010 National Physician Survey and public payment data published in the Institute for Clinical and Evaluative Sciences report Payments to Ontario Physicians from Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Sources 1992/93 to 2009/10 to estimate 2009/2010 net physician income from public payments for Ontario physicians by specialty. Incorporating overhead substantially affects estimates of physician income and changes relative position. For example, ophthalmologists were ranked second when only public payments were considered but eighth when overhead was included. Conversely, hospital-based specialties such as anaesthesia, radiation oncology and emergency medicine rank significantly higher after overhead is included.

Abstract

Au moyen des données recueillies au cours du Sondage national des médecins 2010 et des données sur les paiements provenant des deniers publics, publiées dans le rapport de l'Institut de recherche en services de santé, Payments to Ontario Physicians from Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Sources 1992/93 to 2009/10, nous avons évalué le revenu net des médecins en 2009 et 2010 provenant des deniers publics selon la spécialité médicale. L'intégration des coûts indirects affecte substantiellement l'estimé du revenu des médecins et modifie leur rang relatif. À titre d'exemple, les ophtalmologistes se classent au deuxième rang si on tient compte uniquement des paiements provenant des deniers publics, mais ils occupent le huitième rang quand on y ajoute les coûts indirects. À l'inverse, des spécialités hospitalières telles que l'anesthésie, l'onco-radiologie et la médecine d'urgence occupent un rang relativement plus élevé quand on tient compte des coûts indirects.

Payments to physicians account for approximately 20% of publicly funded healthcare spending in Canada (CIHI 2011). Physician payments are frequently cited in the media as income (Boyle 2012). However, these estimates may be misleading, because they do not include overhead, the expenses incurred by physicians in running their practices. Following changes in income tax policy on the collection of employment information in 1992, reliable data on physician income and practice overhead have been difficult to access (Duffin 2011). Recently, most estimates of net physician income have been performed at the national level and have not been calculated by specialty (Buske 2001, 2002, 2004; CIHI 2004; Statistics Canada 2006; CIHI 2011). In this study we combine data from multiple sources to estimate average net physician income from public payments by specialty in Ontario after adjusting for estimated practice overhead.

Methods

We used data collected in the 2010 National Physician Survey (NPS) and public payment data compiled for the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences report Payments to Ontario Physicians from Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Sources 1992/93 to 2009/10 (“ICES report”) to estimate 2009/2010 net physician income from public payments for Ontario physicians by specialty (CFPC et al. 2010; Henry et al. 2012).

The NPS was sent to all physicians licensed to practise in Canada. Sampling weights were applied to adjust for over- and underrepresentation. We obtained a custom data set from the NPS administrators consisting of self-reported overhead estimates for respondents from Ontario. For specialties in Ontario whose response was fewer than 30 physicians, Canadian NPS data were used.

The ICES report compiled multiple streams of data to produce a reasonably comprehensive estimate of public payments at the level of individual physicians. ICES was unable to include direct payments to physicians from hospital budgets, payments by the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, hospital on-call funds administered by the Ontario Medical Association and private payments for uninsured services. Technical fees paid to offset the costs associated with providing services were excluded, primarily because the nature of the available data precluded us from being certain about which technical fees are physician income and which are not.

To calculate average net income for each specialty, we subtracted the percentage of overhead reported in the NPS from mean gross public payments per full-time equivalent (FTE) reported in the ICES report. This approach has been used previously (Buske 2004; Laugesen and Glied 2011).

Results

Mean self-reported overhead ranged from 12.5% in emergency medicine to 42.5% in ophthalmology. Mean physician income by specialty is shown in Figure 1. After subtracting estimated overhead, the specialties in Ontario with the highest mean net income in 2009/2010 were, in descending order: diagnostic radiology, nephrology, vascular surgery, cardio/thoracic surgery and gastroenterology. The specialties with the lowest mean net income were, in ascending order: paediatrics, neurology, physical/rehabilitation medicine, internal medicine and rheumatology. Family physicians/general practitioners had a mean net income of $207,600. The mean net income from public payments for all physicians in Ontario after adjusting for overhead was $240,400.

FIGURE 1.

Mean physician income before and after subtracting overhead

In addition to there being substantial variation in overhead between specialties, we observed substantial variation within some specialties. Variation between and within selected specialties is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sample of variation in overhead between and within specialties

| Anaesthesia | Diagnostic Radiology | Cardiology | Family Medicine | Ophthalmology | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What percentage of your income goes towards running your practice? | <10% | 56% | 41% | 13% | 5% | 2% |

| 11%–29% | 33% | 27% | 40% | 21% | 10% | |

| >30% | 10% | 31% | 48% | 68% | 88% |

Discussion

Incorporating overhead substantially affects estimates of physician income and changes the relative position of specialties. For example, ophthalmologists were ranked second when only public payments were considered but fell to eighth when overhead was included. Conversely, hospital-based physicians such as anaesthesiologists, radiation oncologists and emergency medicine physicians ranked significantly higher after adjusting for overhead.

The Canadian Medical Association published estimates of net physician income of $148,700 in 2004, substantially lower, even when adjusted for inflation, than our estimate of $240,400 for 2010 (Buske 2004). This discrepancy is partially explained by our focus on Ontario physicians, reported in the CMA study as having the highest billings nationally, rather than focusing on all physicians in Canada. In addition, the CIHI income data used by the CMA were limited to fee-for-service billings, whereas the ICES data included non–fee-for-service payments (CIHI 2004). Most importantly, data from the ICES report establish that between 2004/2005 and 2009/2010, public payments per physician rose by approximately $100,000, a rate of increase well beyond the rate of inflation (Henry et al. 2012). These factors may also partially explain the gap between our estimates and annual income estimates reported in the 2006 census, which were $148,109 for family doctors and $201,847 for specialists working full-time in unadjusted 2005 dollars (Statistics Canada 2006). Additionally, it has been observed in the literature that census income estimates have historically fallen below estimates based on taxation statistics, presumably because census data are based entirely on self-reports (Duffin 2011). The large increase in gross billings between 2005 and 2010 likely also accounts in large part for the lower self-reported overhead in the NPS than that collected by the CMA's 2002 Physician Resource Questionnaire, as well as other overhead estimates identified elsewhere (Léger and Fitzpatrick 2011).

Comparisons at the international level are difficult to interpret. A comparative study that attempted to capture net income differences between Canadian and American physicians adopted a similar approach to our study, but used data from 1985, limiting its current usefulness (Fuchs and Hahn 1990). A more comparable international study estimated net income in Canada in 2008 to be $125,104 for primary care physicians and $208,634 for orthopaedic surgeons (Laugesen and Glied 2011). However, this study calculated net income for orthopaedic surgeons by subtracting overhead data from the 1998 CMA Physician Resource Questionnaire against 2005/2006 national fee-for-service payments reported by CIHI. An OECD estimate of physician income across 14 countries used the same approach, subtracting overhead from the 2002 CMA questionnaire from the same 2005/2006 CIHI data (Fujisawa and Lafortune 2008). In contrast, we used more recent and more comprehensive data for payments as well as contemporaneously reported data for overhead.

Our study highlights the difficulties in gathering reliable data on physician income and overhead. Given the public interest in ensuring that physicians earn an appropriate income, the large amount of public funds paid to physicians and the fact that many physicians operate as independent contractors, more complete data should be collected about physician earnings, both before and after the inclusion of overhead.

Limitations

Several limitations of our study merit emphasis. The response rate for the NPS was only 18.5%, overhead data were based on self-report and no validation studies of self-reported physician overhead were found in the literature. Overhead may be slightly underestimated for specialties where national data were used, because overhead in Ontario is slightly above the Canadian mean (26% vs. 28%). We were unable to include some specialties in our study because public payment data were incomplete (e.g., psychiatry) or because there were fewer than 30 respondents in the country (e.g., nuclear medicine). If individuals who had little or no overhead expenses selected “not applicable” on the NPS overhead question, the estimates of overhead will be inflated. Also, overhead data could not be linked at the individual level, so we cannot present the distribution of net income within each specialty. The exclusion of technical fees will likely serve to underestimate physician net income for specialties where physicians calculated overhead percentage after including these payments. Private payments were also excluded from our study. These limitations will have different effects in different specialties, and are illustrative of some of the challenges inherent in estimating physician compensation without using individual and corporate tax returns as a data source.

Conclusion

Self-reported overhead varies substantially both within and between specialties, and has a substantial effect on physician income. Mean net income from public payments varies more than twofold between specialties. Given the lack of complete data, it is difficult to construct a complete account of physician income in Ontario.

Contributor Information

Jeremy Petch, Keenan Research Centre, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, ON.

Irfan A. Dhalla, Keenan Research Centre, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

David A. Henry, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Susan E. Schultz, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, ON.

Richard H. Glazier, Keenan Research Centre, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Sacha Bhatia, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, ON.

Andreas Laupacis, Keenan Research Centre, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

REFERENCES

- Boyle T. 2012. “Province Targeting Doctors Making Over $600,000 a Year, Forum Told.” The Toronto Star. Retrieved September 21, 2012 <http://www.thestar.com/news/canada/politics/article/1175328–province-targeting-doctors-making-over-600-000-a-year-forum-told>.

- Buske L. 2001. “Canada's Physicians: The Rising Cost of Doing Business.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 164(6): 858 [Google Scholar]

- Buske L. 2002. “Net Earnings for FPs, Specialists.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 167(5): 535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buske L. 2004. “Physician Billing Highest in Ontario, Lowest in Quebec.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 170(5): 776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). 2004. “Analytical Bulletin Physician Expenditures.” Ottawa: Author: Retrieved September 21, 2012 <http://www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/pdf/internet/bul_npdb-28may2004_en>. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). “Health Care Cost Drivers: The Facts.”. Ottawa: Author: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Medical Association (CMA). 2002. Physician Resource Questionnaire. Ottawa: Author [Google Scholar]

- College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), Canadian Medical Association and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. 2010. 2010 National Physician Survey. Retrieved September 21, 2012 <http://www.nationalphysiciansurvey.ca/nps/2010_Survey/methods/weights-e.asp>.

- Duffin J. 2011. “The Impact of Single-Payer Health Care on Physician Income in Canada, 1850–2005.” American Journal of Public Health 101(7): 1198–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs V.R., Hahn J.S. 1990. “How Does Canada Do It? A Comparison of Expenditures for Physicians' Services in the United States and Canada.” New England Journal of Medicine 323: 884–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa R., Lafortune G. 2008. The Remuneration of General Practitioners and Specialists in 14 OECD Countries: What Are the Factors Influencing Variations across Countries? Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [Google Scholar]

- Henry D.A., Schultz S.E., Richard G.H., Sacha Bhatia S.R., Dhalla I.A., Laupacis A. 2012. Payments to Ontario Physicians from Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Sources 1992/93 to 2009/10. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; Retrieved September 21, 2012 <http://www.ices.on.ca/file/ICES_PhysiciansReport_2012.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Laugesen M.J., Glied S.A. 2011. “Higher Fees Paid to US Physicians Drive Higher Spending for Physician Services Compared to Other Countries.” Health Affairs 30(9): 1647– 56, appendix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léger P.T., Fitzpatrick S. 2011. “Exploring Options for Physician Payment in Canada.” Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; Retrieved September 21, 2012, <http://www.chsrf.ca/Libraries/Researcher_on_Call/2011-06-02-ROC-CHSRF.sflb.ashx>. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. “Employment Income Statistics in Constant (2005) Dollars, Work Activity in the Reference Year, Occupation – National Occupational Classification for Statistics 2006 and Sex for the Population 15 Years and Over with Employment Income of Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2000 and 2005.”. Ottawa: Author: 2006. Catalogue no. 97-563-XCB2006062. [Google Scholar]